1. Introduction

Medical entomology is a discipline that study arthropods of medical interest affecting animals and humans, and more globally impacting upon public health by causing pests and/or infections [

1]. Arthropods form an extremely diverse group, including more than 10 million species, and representing nearly 80% of the animal phylum [

2]. Some arthropods are qualified as “vectors” by ensuring the transmission of pathogenic microorganisms such as parasites, bacteria or viruses, from one vertebrate host to another during their blood meals [

3]. These diseases conveyed by arthropods, are known as vector-borne diseases (VBDs). To prevent the emergence of VBDs, the monitoring and control of arthropod vectors remains essential. The success of a relevant survey is directly linked to the accurate identification of arthropods at the species level, distinguishing vectors from non-vectors.

Currently, arthropod identification was essentially based on morphological and molecular biology tools [

4]. Morphological identification required the use of dichotomous identification keys, in paper or digital formats. However, reliable documentation is not always available, notably for all developmental stages of these [

5]. Moreover, the need for entomological expertise and undamaged specimens are bottlenecks to its widespread use. Conversely, arthropod identification using molecular techniques is accurate, regardless of the specimen’s developmental stage or integrity. Nevertheless, this approach remains time-consuming, expensive and the availability of target sequences is indispensable [

6].

Recently, an alternative tool based on the analysis of protein profiles resulting from matrix-assisted laser desorption/ionization time-of-flight mass spectrometry (MALDI-TOF MS) has been explored for the identification of arthropods [

4,

7,

8]. MALDI-TOF MS has been evaluated as a relatively inexpensive methodology, which is technically reproducible and simple, allowing large-scale and rapid processing for the identification of arthropods, including mosquitoes [

9], Culicoides [

10], ticks [

11], phlebotomine sand flies [

12], fleas [

13] and lice [

14]. Despite the success of this tool for arthropod classification and its broad application to medical entomology [

15], some limitations have been reported, as is frequently the case for innovative approaches. Notwithstanding the absence of commercial or sharable reference MS spectra DB, the intra-species reproducibility and inter-species specificity of MS spectra are essential for reliable classification [

16]. However, some factors could alter these parameters (i.e., the reproducibility and specificity of MS spectra), such as the specimen compartment selected for MS analysis (same genome, but distinct proteome for different body parts), or the conditions of sample preparation [

17]. Optimised procedures and standardised protocols have been established for the identification of mosquitoes, ticks and fleas by MALDI-TOF MS [

17,

18,

19]. One recent study reported that the cephalothorax with legs from lice appeared as the best compartment for specimen identification by MALDI-TOF MS [

14].

The storing conditions of the specimens from field collection until MS analysis and the duration of storage are other factors which could impede arthropod identification. Several studies have reported MS spectra variations between specimens of the same species according to the storing conditions (e.g. frozenly

vs in alcohol) [

20,

21]. Although freezing appeared to be the more efficient preservation method for MS analysis [

18,

19], it is not systematically possible to refrigerate samples in the field. Then, the storing of specimens in alcohol remains the most frequently used alternative [

13,

22]. However, this preservation method generally induces modifications of MS profiling from arthropods in comparison with frozen species [

20,

23]. These MS profile changes could be sufficient to impair matching with its counterpart species from the reference DB stored in another mode [

17].

Several studies, performed on distinct families of arthropods stored in alcohol, underlined the intra-species reproducibility of MS spectra [

19,

24,

25]. The future analysis of specimens stored in alcohol by MALDI-TOF MS become possible, on condition that new reference MS spectra from counterpart specimens, stored and prepared in the same conditions, were added to the database. Although several studies using the MS profiling tool have demonstrated it success for identifying ticks [

20,

26] and Culicoides [

25,

27] stored in alcohol, scarce data are available for lice [

16] and fleas [

19,

21].

Lice and fleas are ectoparasites presenting a huge veterinary public health problem with economic consequences, notably for livestock [

28,

29]. They have been described as vectors of several pathogens for animals and humans. Lice are known as vectors of human diseases including

Bartonella quintana, the agent of trench fever;

Borrelia recurrentis, the agent of louse-borne relapsing fever;

Rickettsia prowazekii, the agent of epidemic typhus [

30,

31]; and

Yersinia pestis, the causal agent of plague [

32]. Fleas are also vectors of diseases such as bubonic plague, caused by

Yersinia pestis, and murine typhus, caused by

Rickettsia typhi [

33,

34]. Fleas can also transmit

Bartonella henselae, the agent of cat-scratch disease [

35]. These two arthropod species of medical importance are often collected from livestock in the field and stored in alcohol [

16,

21]. Few studies have evaluated the performance of MALDI-TOF MS for the identification of fleas [

13,

19] or lice [

16] stored in alcohol, and when it was done, specimens were stored in alcohol few months without kinetic assessment.

As the duration of specimens storing in alcohol could also influence on the reproducibility of MS spectra [

36], the present study assessed the stability of MS profiles from lice and fleas stored in alcohol for periods of between one and four years, as well as the efficiency of MALDI-TOF MS for correct identification of these arthropods. For this purpose, one louse (

Pediculus humanus corporis) and one flea (

Ctenocephalides felis) species, preserved in alcohol for periods ranging from a few months to four years were kinetically prepared for MS submission. The reproducibility and stability of the MS profiles over time for each species were evaluated based on the level of significance of the identification accuracy.

3. Results

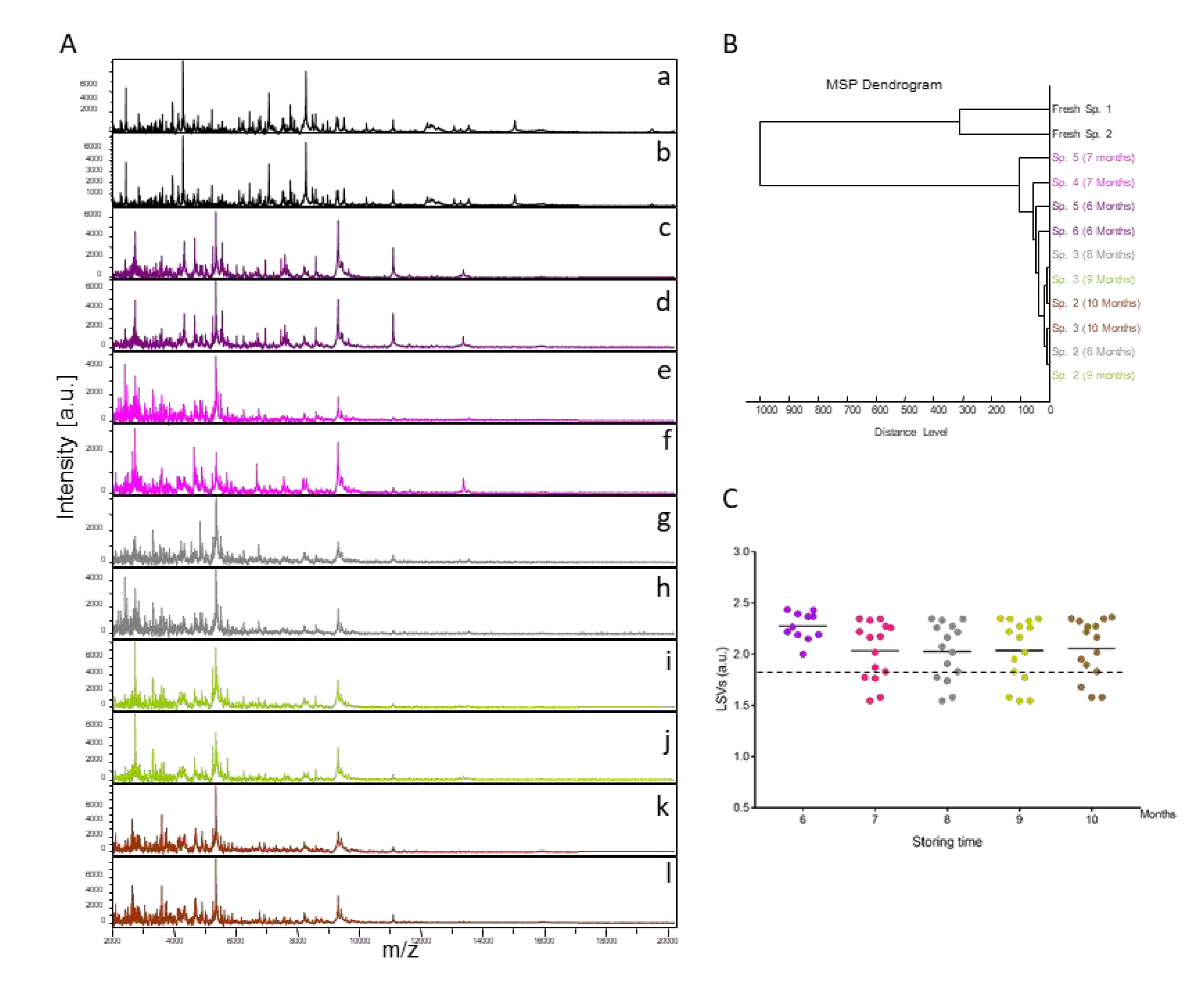

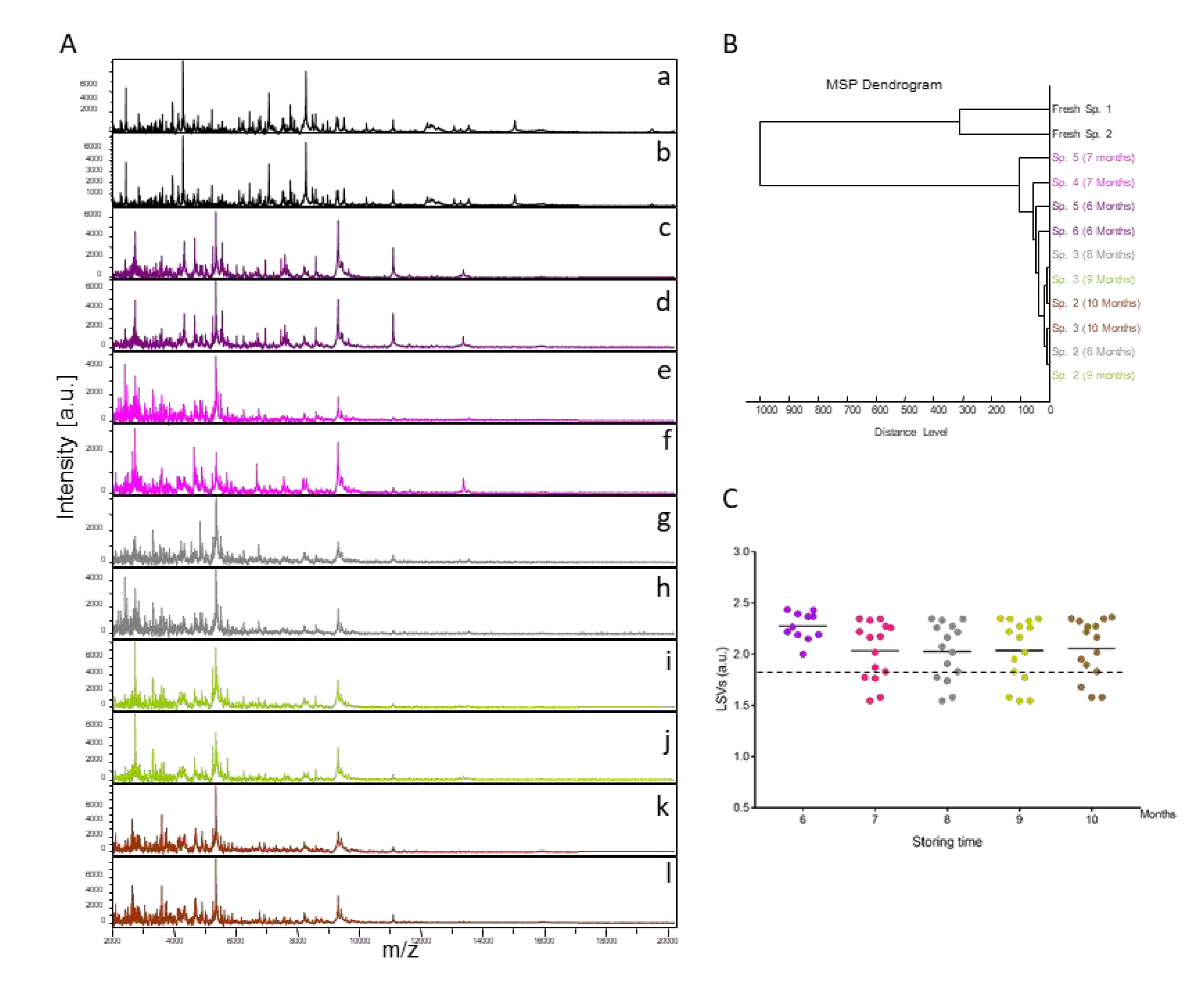

3.1. Assessment of flea’s alcohol preservation compatibilities with MALDI-TOF MS analyses

Fifteen specimens of

Ct. felis stored in alcohol were monthly (from months 6 to 10) submitted to MALDI-TOF MS analysis. The resulting MS spectra, compared with those from fresh specimens, showed that MS profiles were visually not reproducible between fresh specimens and those stored in alcohol for variable times (

Figure 1A). Conversely, the MS spectra from specimens stored in alcohol appear to be reproducible for each time point but also between times points (

Figure 1A). To estimate the reproducibility of these MS spectra, an MSP dendrogram was creating using the MS profiles of two specimens per time point. Interestingly, it was observed that MS spectra from fleas stored in alcohol clustered in the same branch distinct from those of fresh specimens of the same species (

Figure 1B). Moreover, the intertwining of the MS spectra from specimens stored in alcohol, independently of the duration of storage, underlined that MS spectra were similar regardless of the length of time they were stored in this buffer.

To assess whether MALDI-TOF MS biotyping could be applied to identify fleas stored in alcohol, MS spectra from 15 specimens stored in alcohol per time point were queried against the home-made MS spectra reference DB upgraded with MS profiles from four

Ct. felis stored in alcohol for six months. MS spectra from solely 11 flea cephalothoraxes, stored in alcohol during six months, were then queried against the DB. All (100%) of the 71 specimens analysed were correctly identified at the species level (

Figure 1C). Their LSVs ranged from 1.55 to 2.44. In preliminary studies, a LSVs ≥ 1.8 appeared to be a threshold for reliable identification [

19]. Here, 84.5% (n=60/71) of MS spectra succeeded in reaching this threshold (LSVs>1.8).

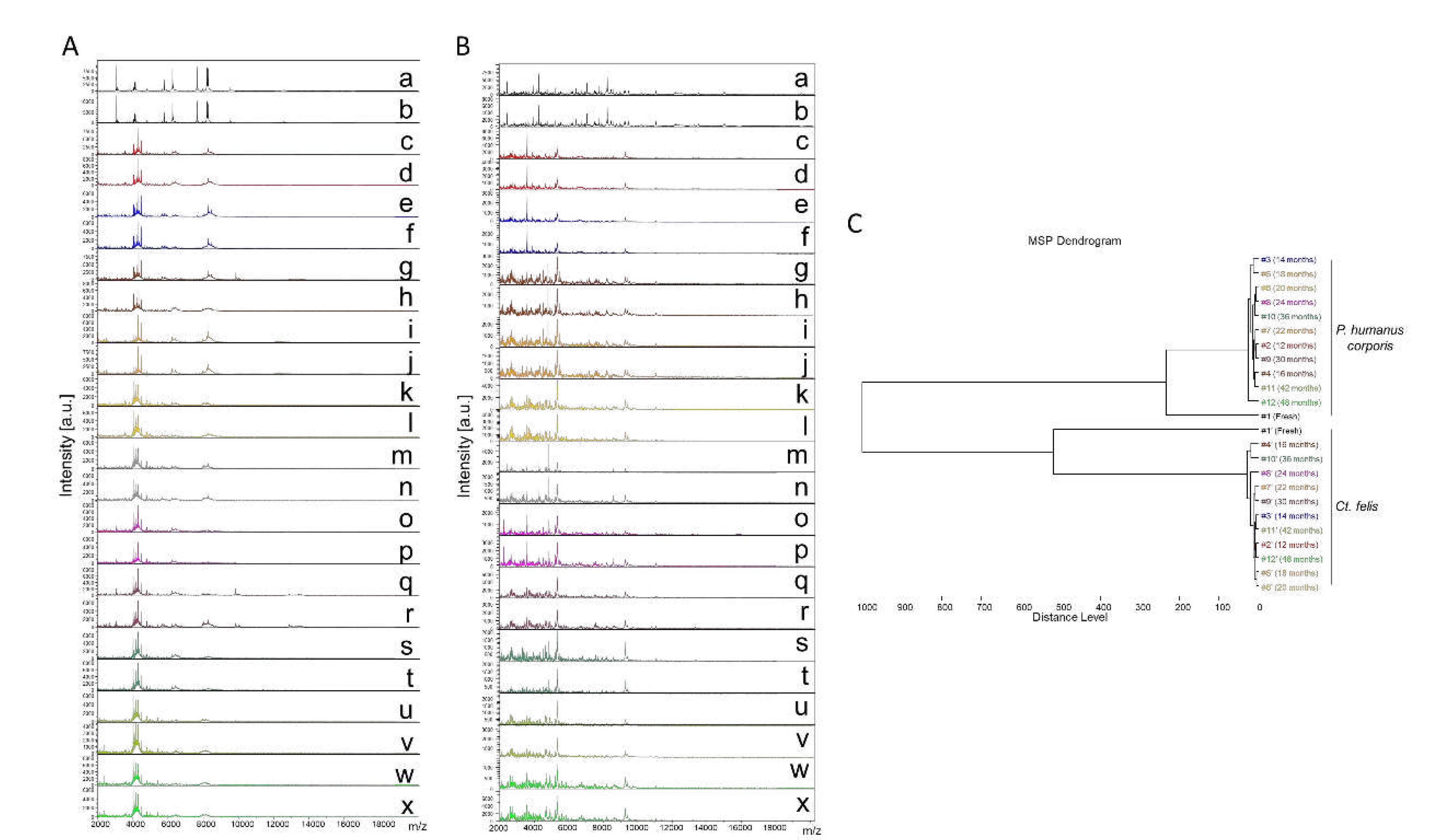

3.2. Consequences on MS spectra of lice and fleas storing in alcohol during several years

Despite a delay of 24 hours between the last blood meals of these two arthropod species and their collection for sedation at −20°C prior to being stored in 70% (v/v) alcohol at room temperature, blood remnant in abdomens was sometime observed. During the separation of the cephalothorax from abdomen, blood leaks could therefore occur, contaminating the cephalothorax of the specimen. As the aim of this study was to test the stability of cephalothorax MS profiles according to the length of time they were stored in alcohol, all cephalothoraxes contaminated with blood during the dissection step were excluded from the analysis to prevent mismatching of MS spectra due to their corruption by host blood. Consequently, cephalothoraxes from one flea dissected at month 16 and seven lice dissected at months 18 (n=2), 36 (n=1), 42 (n=2) and 48 (n=2), contaminated with blood remnants, were excluded from the MS submission.

Finally, a total of 289 cephalothorax MS spectra from lice (

P. humanus corporis, n=125) and fleas (

Ct. felis, n=164), were subjected to MS analysis. The visual comparison of MS spectra of two specimens per time point, from lice (

Figure 2A) and fleas (

Figure 2B), indicated a relative stability of profiles for both species, independently of the duration of storage in alcohol from between 12 and 48 months. To estimate the reproducibility of these MS spectra, a MSP dendrogram was performed with MS profiles from a single louse and flea sample per time point. The clustering of MS spectra from lice and fleas onto distinct branches underlined the specificity of these protein profiles (

Figure 2C). For both species, fresh specimens were separated from those stored in alcohol, confirming a modification of the profiles according to the storage method. The short distances between the branches of MS spectra from specimens stored in alcohol per species supports the high reproducibility of these MS spectra. The absence of ordination according to time in each cluster underlined that the duration of storage in alcohol seems not to affect the MS profiles. Collectively, these data suggest that MS spectra from

P. humanus corporis and

Ct. felis appeared relatively stable throughout the four years of storage in alcohol.

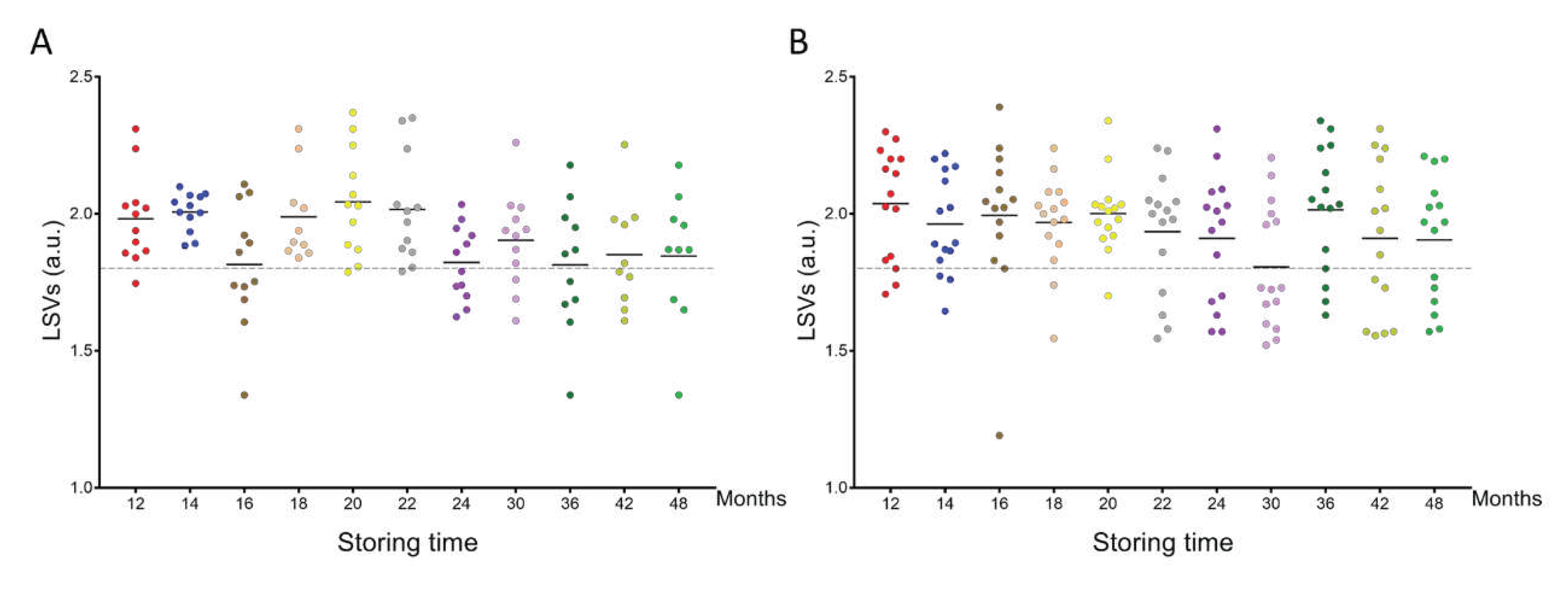

3.3. Assessment of specimen identification according to storing time in alcohol based on MS spectra query against the MS reference spectra database

MS spectra from the cephalothoraxes of 125

P. humanus corporis and 164

Ct. felis stored from one to four years in alcohol, were interrogated against the home-made MS reference spectra DB. The query against the database revealed that 97.6% (n=122/125) of lice and 99.4% (n=163/164) of fleas were correctly identified at the species level. Their LSVs ranged from 1.34 to 2.37 and 1.19 to 2.39 for

P. humanus corporis (

Figure 3A) and

Ct. felis, respectively (

Figure 3B). The four misidentified specimens presented an LSV lower than 1.35. As for relevant identification LSVs should reach 1.8, in that case, 75.2% (n=94/125) and 74.4% (n=122/164) of overalls lice and fleas, respectively, could be considered accurately classified. Although the proportions of relevant identification were similar for both species, the rate of pertinent classification appeared too low for applying this tool for identification of lice and fleas stored more than one year in alcohol.

Interestingly, the analysis of the rate of relevant identification per time point and species showed a clear reduction in these proportions after 22 and 24 months of storage in alcohol for lice and fleas, respectively (Supplementary File S1A). Effectively, for lice stored during 12 to 22 months, the rate of relevant identification was of 87.1% (n=61/70), whereas from months 24 to 48, this rate fallen to 60.0% (n=33/55), corresponding to a significant decrease (Mann-Whitney test, p<0.001, Supplementary File S1B). For the fleas, the mean rate of correct identification for months 12 to 20 were of 87.8% (n=65/74), whereas, from months 22 to 48, this rate diminished significantly to 63.3% (n=57/90; Mann-Whitney test, p=0.042, Supplementary File S1B). When the proportion of relevant identification for fleas from months 6 to 10 (84.5%) was taken into account, the global proportion of relevant identification from months 6 to 20, was 86.2%.

3.4. Effect of alcohol remnants on MS spectra for long time storing

At month 16 for lice, only half of the specimens were accurately identified, whereas high proportions of relevant LSVs were obtained before and after this time point (100%) (Additional file S1A). This low rate of relevant identification could likely not be attributed to the storing duration in alcohol. Other factors, such as the modalities of sample preparation, are potentially responsible for this lower reproducibility of MS spectra. To control the quality of the matrix, sample loading and MALDI-TOF apparatus performance, the matrix solution was loaded in duplicate onto each MALDI-TOF plate, with and without one fresh louse and flea, prepared under the same conditions, which served also as grinding controls, as previously described [

9,

41]. Here, at all time points, including month 16 for lice, high LSVs (> 2.0) with correct identification, were obtained for the fresh specimens used as controls of sample preparation. Then, the low LSVs of samples stored in alcohol could therefore not be attributed to any buffer or apparatus failures. The only difference between fresh and alcohol-stored lice, was the storing mode. In the present study, immediately after dissection, cephalothoraxes from lice and fleas stored in alcohol, were dried overnight at RT during at least 12 hours. After this half a day drying, no trace of alcohol were visible. As MS spectra were reproducible with intense MS peaks, this drying condition was considered to be sufficient to evaporate all alcohol traces. However, in a recent study, it was noticed that if arthropod samples stored in alcohol were insufficiently dried, so MS spectra of low quality were generated [

36].

Then, it was hypothesized that alcohol trace remaining could occurred in these samples impairing MS spectra matching with the DB. Similarly, it is also possible that for specimens stored more than two years in alcohol, the duration of drying should be increase to eliminate all alcohol traces. To test this hypothesis, 45 lice (15 per time point) and 60 fleas (20 per time point), stored for 48 months in alcohol, were dried during 18 and 24 hours, and compared to the standard condition (overnight, 12 hours). The results of MS spectra query against the DB indicated an improvement of accurate identification rate for both species, with the increased duration of drying. The proportion of relevant LSVs reached 80% and 95% for P. humanus corporis and C. felis, respectively, after 24 hours of drying (Supplementary File S2A). Although an increase in the mean LSV was noticed for both species with the increase of drying duration, this augmentation was significant only for fleas (p=0.037, Kruskal-Wallis test; Supplementary File S2B).

4. Discussion

The low cost, speed and simplicity of MALDI-TOF MS has promoted its widespread application for biotyping microorganisms as well as, more recently, larger organisms such as arthropods [

4,

15]. Although this innovative approach has shown its potential for the classification of fresh or frozen arthropods, its application to specimens stored in alcohol has required some adaptation of the protocol [

20,

36]. Alcohol remains one of the most frequently mode used for storing arthropods [

21]. It presents the advantage of being cost-effective, simple and storage at RT for several years is possible [

42]. In the present study, the performance of this proteomic tool for the identification of lice and fleas stored in alcohol for several years was tested. As these two ectoparasites engender public and veterinary health problems, with economic consequences, notably for livestock [

28,

29], their monitoring for the distinction of vectors from non-vectors using a rapid, simple and accurate identification method of the specimen is require.

A previous study analysed the kinetic MS spectra of cephalothoraxes from

Ct. felis stored in alcohol from between one and six months [

19]. In this previous study, MS spectra from fleas stored in alcohol were modified in comparison to their fresh counterparts. Nevertheless, a relative stability of the MS spectra was observed for these specimens stored in alcohol. These data suggested the possibility of identifying specimens if counterpart species, stored and prepared under the same conditions, were included in the reference MS spectra DB. Our results support this hypothesis with the correct identification of all the samples, among which nearly 80% were relevantly identified with a LSV > 1.8 [

19]. Similar results were obtained for

P. humanus corporis stored in alcohol from one and twelve months, and kinetically analysed by MS [

16]. In these both studies, the duration of storing of lice and fleas in alcohol prior MS submission, did not exceeded one years. As the stability and reproducibility of the species specific MS spectra from lice and fleas conserved in alcohol through the time during several years was not yet evaluated, it was decided to analyze MS spectra stability of cephalothoraxes from these two ectoparasite species during a period of one to four years.

Interestingly, blood contamination had already been reported during dissection of engorged hematophagous arthropods, which could alter MS spectra and then impair the correct identification of the specimen [

12,

17,

41]. To limit bias in the assessment of MS spectra reproducibility according to duration of specimens stored in alcohol, the cephalothoraxes from one flea and seven lice, contaminated by blood during dissection step, were excluded of the analysis.

For lice, in a previous work using MALDI-TOF MS, the proportion of relevant identification for specimens stored in alcohol during the first years reached 93.9% [

16], which is consistent with the results obtained in the present work. However, it was observed here that the rate of correct and relevant identification, decreased with the longer time of lice preservation in alcohol. Collectively, these results indicate that, for both species, preserving samples in alcohol for more than two years seems to be deleterious for the stability of the MS spectra. Indeed, for lice and fleas, relatively long-term storage in alcohol (more than 22 and 20 months, respectively), could reduce the success of MS identification. This phenomenon affected up to 40% of the sample at 48 months, which is not trivial. However, an acceptable rate of relevant identification could be obtained for specimens stored for nearly two years (20 or 22 months). It is interesting to note that the rate of accurate identification for lice and fleas is less efficient than for other families of arthropods such as ticks [

23,

42], Culicoides [

43] and sandflies [

44]. Effectively, the storage in alcohol of specimens from these last three arthropod families, over the same period (about four years) does not appear to dramatically alter their MS profiles. Whereas for longer time of storing in alcohol (from 10 to 50 years) [

36], standard protocols were shown inefficient for tick identification and new methods for sample preparation were required to improve MS spectra. In this previous work, the authors reported that the low quality of MS spectra from tick samples stored in alcohol were attributed to an insufficiently dried [

36].

Based on these data, an optimization of the present protocol was applied to succeed MS identification of lice and fleas stored in alcohol longer than two years. An increase of the drying period was then assessed. Our results support that a longer drying time upper than 12h (overnight) for lice and flea cephalothoraxes stored in 70% ethanol for more than 2 years, is necessary to evaporate almost all of the alcohol and erase its traces which alter the MS profile hampering the accuracy of identification. Nevertheless, others factors could induce MS spectra changes, low peak intensities and/or heterogeneity among replicates [

19], such as imperfect dissection, protein degradation during alcohol storing period, incomplete grinding or faulty loading on the MALDI target plate [

45].

Figure 1.

Consequences on cephalothorax MS spectra for their identification of storing fleas in alcohol. (A) Representative MS spectra of cephalothoraxes of fresh adult Ct. felis (a, b) and adult Ct. felis stored for 6 (c, d), 7 (e, f), 8 (g, h), 9 (i, j) or 10 (k, l) months in alcohol 70% v/v. (B) Reproducibility and specificity of MALDI-TOF MS spectra from Ct. felis fleas. Two specimens per storage method (fresh vs alcohol) and duration (from 6 to 10 months in alcohol) were used to construct the MSP dendrogram. The dendrogram was created using Biotyper v3.0 software and distance units correspond to the relative similarity of MS spectra. (C) Comparison of LSVs obtained for 15 specimens stored in alcohol tested monthly against the upgraded homemade MS reference database with MS spectra from Ct. felis stored in alcohol. At month 6, as four were included in the DB, only 11 MS spectra were queried against the DB. Dashed lines represent the threshold value for reliable identification (LSV >1.8). The same colour code was used between the different panels for specimens stored in the same conditions. a.u., arbitrary units; LSVs, log score values; m/z, mass-to-charge ratio.

Figure 1.

Consequences on cephalothorax MS spectra for their identification of storing fleas in alcohol. (A) Representative MS spectra of cephalothoraxes of fresh adult Ct. felis (a, b) and adult Ct. felis stored for 6 (c, d), 7 (e, f), 8 (g, h), 9 (i, j) or 10 (k, l) months in alcohol 70% v/v. (B) Reproducibility and specificity of MALDI-TOF MS spectra from Ct. felis fleas. Two specimens per storage method (fresh vs alcohol) and duration (from 6 to 10 months in alcohol) were used to construct the MSP dendrogram. The dendrogram was created using Biotyper v3.0 software and distance units correspond to the relative similarity of MS spectra. (C) Comparison of LSVs obtained for 15 specimens stored in alcohol tested monthly against the upgraded homemade MS reference database with MS spectra from Ct. felis stored in alcohol. At month 6, as four were included in the DB, only 11 MS spectra were queried against the DB. Dashed lines represent the threshold value for reliable identification (LSV >1.8). The same colour code was used between the different panels for specimens stored in the same conditions. a.u., arbitrary units; LSVs, log score values; m/z, mass-to-charge ratio.

Figure 2.

Consequences of alcohol storage time on stability of cephalothorax MS profiles from lice and fleas. Representative MS spectra of cephalothoraxes of adult P. humanus corporis (A) and Ct. felis (B) from fresh specimens (a, b) or specimens stored in alcohol for 12 (c, d), 14 (e, f), 16 (g, h), 18 (i, j), 20 (k, l), 22 (m, n), 24 (o, p), 30 (q, r), 36 (s, t), 42 (u, v) and 48 (w, x) months. (C) Reproducibility and specificity of MALDI-TOF MS spectra from P. humanus corporis lice and Ct. felis fleas. One specimen per storage method (fresh vs alcohol) and length of storing (from 12 to 48 months in alcohol) were used to construct the MSP dendrogram. The same colour code was used between the different panels for specimens stored in the same conditions. #1 to #12: specimen number; a.u., arbitrary units; m/z, mass-to-charge ratio.

Figure 2.

Consequences of alcohol storage time on stability of cephalothorax MS profiles from lice and fleas. Representative MS spectra of cephalothoraxes of adult P. humanus corporis (A) and Ct. felis (B) from fresh specimens (a, b) or specimens stored in alcohol for 12 (c, d), 14 (e, f), 16 (g, h), 18 (i, j), 20 (k, l), 22 (m, n), 24 (o, p), 30 (q, r), 36 (s, t), 42 (u, v) and 48 (w, x) months. (C) Reproducibility and specificity of MALDI-TOF MS spectra from P. humanus corporis lice and Ct. felis fleas. One specimen per storage method (fresh vs alcohol) and length of storing (from 12 to 48 months in alcohol) were used to construct the MSP dendrogram. The same colour code was used between the different panels for specimens stored in the same conditions. #1 to #12: specimen number; a.u., arbitrary units; m/z, mass-to-charge ratio.

Figure 3.

Comparison of LSVs obtained for lice and flea specimens stored in alcohol and kinetically subjected to MS analysis against the upgraded homemade MS reference database. LSVs obtained for cephalothorax MS spectra from P. humanus corporis (A) and Ct. felis fleas (B) stored in alcohol for between 12 months and 48 months were presented. The dashed line represents the threshold value for reliable identification (LSV > 1.8). The same colour code was used between the different panels for specimens stored in alcohol for the same length of time. a.u., arbitrary units; LSV, log score value.

Figure 3.

Comparison of LSVs obtained for lice and flea specimens stored in alcohol and kinetically subjected to MS analysis against the upgraded homemade MS reference database. LSVs obtained for cephalothorax MS spectra from P. humanus corporis (A) and Ct. felis fleas (B) stored in alcohol for between 12 months and 48 months were presented. The dashed line represents the threshold value for reliable identification (LSV > 1.8). The same colour code was used between the different panels for specimens stored in alcohol for the same length of time. a.u., arbitrary units; LSV, log score value.