1. Introduction

Nowadays, most of our Internet access relies on domain name resolution through the Domain Name System (DNS), which has become one of the indispensable Internet services. As is well-known, DNS queries for domain name resolution contain the source IP address and the domain name of the destination server, such as web and mail servers. The DNS communication mechanism standardized in the early days did not consider encryption [

1]. Moreover, DNS communications may cross multiple Internet Service Providers (ISPs) and national borders so that it is technically possible to intercept them along the way. Accordingly, the challenge is that end user privacy may not be adequately protected if DNS communication is monitored extensively [

2].

To address this issue, the Internet Engineering Task Force (IETF) has standardized DNS over TLS (DoT) [

3] and DNS over HTTPS (DoH) [

4]. Using these technical standards, the DNS client and DNS full-service resolver encrypt DNS communications to protect privacy from eavesdropping. DoT and DoH have now been implemented in some browsers and operating systems to provide enhanced privacy protection for end users. So far, the privacy protection in domain name resolution has mainly focused on end users, which means that the DNS clients and DNS full-service resolver encrypt communication with each other, while the communication between the DNS full-service resolver and authoritative DNS servers is still in plaintext. In other words, encryption protects end user privacy but not institutional privacy.

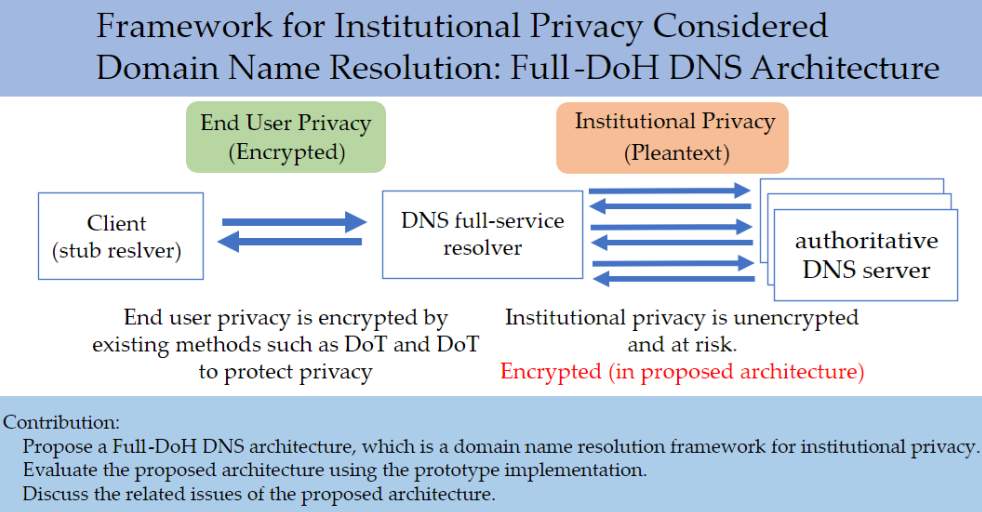

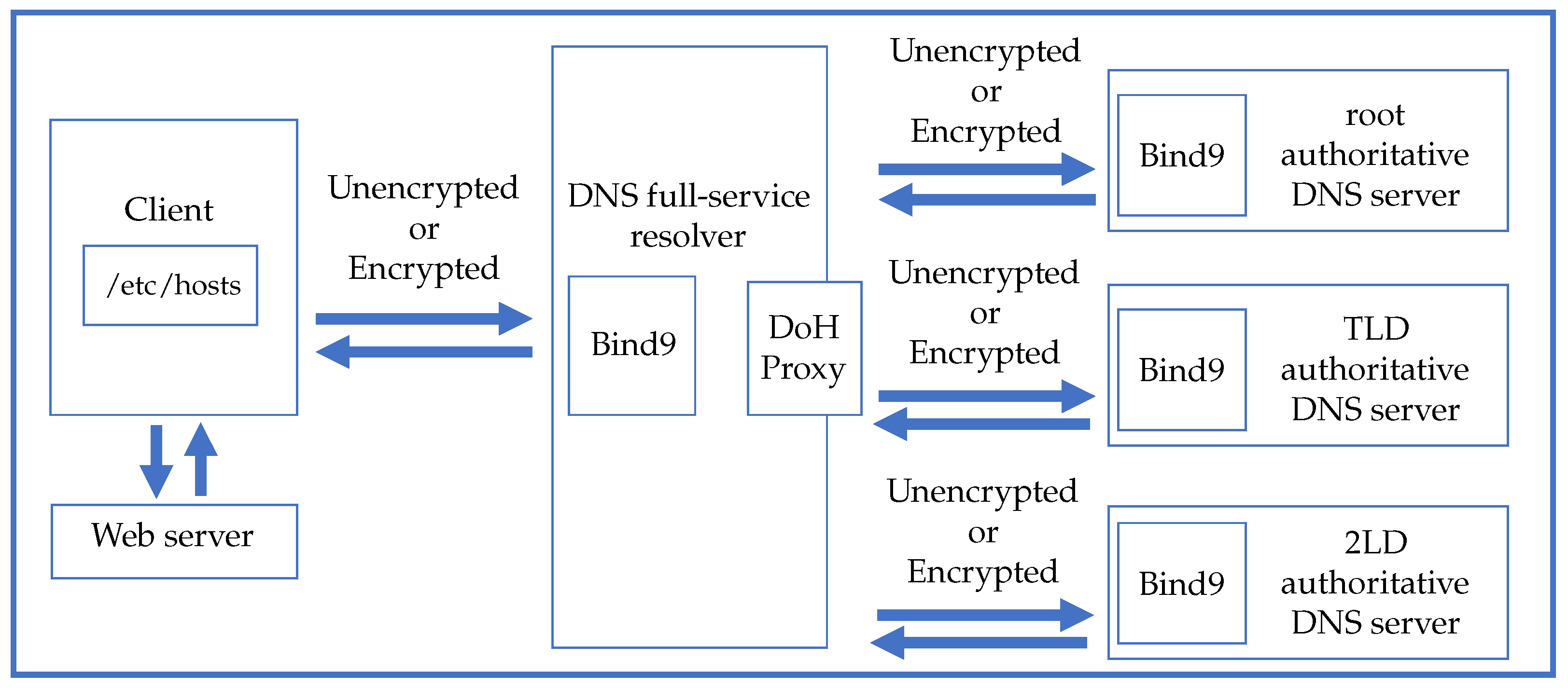

Figure 1 illustrates the difference between end user privacy and institutional privacy in DNS communication.

A DNS request from a DNS full-service resolver to an authoritative DNS server has not been considered a privacy risk because the source IP address of the DNS query belongs to the DNS full-service resolver. However, in recent years, there have been reports of specific techniques for identifying the privacy of previously unknown institutions by analyzing the logs of authoritative DNS servers [

5]. As a concrete threat example of institutional privacy, an institution’s affiliation in sensitive categories (LGBTQ+, religion, political activism, etc.) may be leaked due to analyzing DNS communications from DNS queries. If a third party leaks sensitive information about the institutions, the credibility and brand value of the institutions may be affected.

One of the countermeasures of institutional privacy is Query Name Minimization (Q-min), which has been standardized to mitigate the risk of privacy leakage between DNS full-service resolver and authoritative DNS servers [

6]. Q-min enhances privacy protection by restricting domain name information sent to authoritative DNS servers. However, Q-min has the risk of privacy invasion by attackers and is insufficient as a countermeasure. Therefore, to ensure complete DNS privacy protection, it is necessary to encrypt all DNS traffic during the whole domain name resolution.

In what follows, we propose a domain name resolution framework for institutional privacy, which completely employs encrypted communications. In the proposed framework, in addition to the communication between a client and a DNS full-service resolver, the communication between a DNS full-service resolver and an authoritative DNS server will also be encrypted using DoH. This complements the current standardized DNS protocols and provides further privacy preservation for end users. However, it is unclear whether the domain name resolution process can be completed within a sufficient response time for the end client when DoH is used for all DNS communications. The key contributions of this paper are the following.

Propose a Full-DoH DNS architecture, which is a domain name resolution framework for institutional privacy.

Evaluate the proposed architecture using the prototype implementation.

Discuss the related issues of the proposed architecture.

This article is an extended version of our previous conference publication [

7]. In the previous conference paper, we presented an architectural design and initial implementation for DoH encryption from client to DNS full-service resolver. The major advancement from the previous conference paper is the complete feature evaluation and performance evaluation of the prototype system and the discussion of potential issues and possible solutions.

The rest of this paper is organized as follows.

Section 2 discusses related work, and

Section 3 describes the proposed method. Then

Section 4 and

Section 5 describe the prototype implementation and evaluations, respectively. Next,

Section 6 describes the discussions about potential issues and possible solutions, and finally,

Section 7 concludes the paper.

2. Related Work

As described in the introduction, we focus on privacy issues in domain name resolution. In this section, we first describe IETF standards related to DNS privacy protection. Next, we describe the related works focused on end user privacy protection, which have been extensively investigated in the literature. Finally, we introduce institutional privacy, which is mostly related to the proposed framework in this paper and is a relatively new concept.

2.1. IETF Standards for DNS Communication Encryption

This section introduces IETF standardization activities and technologies related to DNS communication encryption for end user privacy protection.

-

DNS over TLS (DoT)

DoT, which is specified in RFC8310 [

3], allows DNS clients and servers to establish a TLS session before sending DNS queries, which is then used to send DNS queries over encrypted Transmission Control Protocol (TCP). Compared to non-encrypted communication, DoT causes extra overhead. DoT uses port 853 over TCP and User Datagram Protocol (UDP) for communication, which allows it to be easily distinguished from other HTTPS traffic. The latest Windows 11 (InsiderPreview) and macOS support DoT as the client OS. Therefore, users can enhance their privacy protection at the OS level by choosing a DNS full-service resolver that supports DoT.

-

DNS over HTTPS (DoH)

DoH, which is specified in RFC8484 [

4], DoH achieves DNS query encryption by encapsulating DNS queries using HTTPS messages and uses 443/TCP for its communication port. Port 443/TCP is a mixture of HTTPS communication and DoH communication, making DNS traffic analysis difficult. This mechanism benefits privacy protection. Since DoH requires a TLS connection for communication encryption, thus it also causes extra overhead for domain name resolution. DoH is supported by several majority web browsers, Windows 11, and macOS.

-

DNS over QUIC (DoQ)

DoQ, which is specified in RFC9250 [

8], forwards DNS queries over the Quick UDP Internet Connections (QUIC) protocol [

9]. QUIC can be expected to eliminate TCP Head-of-Line Blocking and reduce the latency by communicating on a UDP basis. DoQ has been tested with experimental implementations, but most operating systems and web browsers are not yet supported.

2.2. End User Privacy

DNS privacy protection is primarily achieved through communication encryption. Although encrypted communication can provide strong privacy protection for end users, from the viewpoint of practicality, the extra overhead caused by encrypting and decryption needs to be mitigated. Many approaches in the literature have been proposed for solving the high latency issue on the encrypted domain name resolution.

Böttger et al. quantitatively evaluated the processing time overhead and impact on web page load times of encrypting with DoH and showed why DoH is gaining attention [

10]. Chhabra et al. measured DoH communications around the world [

11]. They reported that the degradation of client user experience was more pronounced when DoH was used in environments with poor network connectivity. Hounsel et al. compared encrypted and unencrypted DNS communication and investigated the impact of DoT and DoH on web page load times [

12].

The issue is that these studies focus on end user privacy and do not consider the privacy of all DNS communications. Achieving privacy protection in all DNS communication also requires investigating the communication between DNS full-service resolver and DNS authoritative DNS servers. Currently, communication between the DNS full-service resolver and DNS authoritative DNS servers is not encrypted. Privacy information between DNS full-service resolver and authoritative DNS servers is detailed in the next section.

2.3. Institutional Privacy

End user privacy, as described in the previous sections, is achieved by encrypting communication between a client and a DNS full-service resolver. However, end user privacy is insufficient as a measure against privacy leaks, and a new framework to realize better protection is institutional privacy. Imana et al. defined “institutional privacy as the confidentiality of the digital footprints of an institution’s internal activities by its personnel” [

5].

End user privacy refers to the privacy of a single user, and so far, it has been the focus of the protection and measures for privacy protection. However, for institutional units such as corporations and universities, institutional privacy, which is illustrated in

Figure 1, measures are needed to fulfill their responsibilities to their members. For instance, the disclosure by a third party of the fact that a member of one institution sends e-mails to another institution whose activities are based on a particular political belief, race, religion, or sexual orientation will affect the institution’s credibility and brand value. In addition, the frequency of sending e-mails combined with the timing of constituent activity and other information can lead to the identification of the institution’s constituents, resulting in an invasion of end user privacy.

Although DNS communications between DNS full-service resolver and authoritative DNS servers do not directly include the end user’s IP address, the combination of information can reveal potentially unknowable privacy information. In [

5], the anonymized log data of the root DNS server is analyzed to investigate the leakage of Institutional privacy information. This means that advisories can perform the same analysis, so encrypting DNS communications between the DNS full-service resolver and authoritative DNS server will be important to achieve institutional privacy protection.

One existing technology to mitigate the risk of institutional privacy is Q-min [

6]. We introduce prior research on privacy preservation using Q-min. Bradshaw et al. showed the importance of strengthening privacy protection for DNS communications that communicate across borders [

13]. They surveyed the laws of various nations and found that none of them spell out how DNS data should be handled and that there is no guarantee of transparency or consistency in how data is handled. Ensuring transparency and consistency in handling DNS data to protect the privacy of DNS communications is important not only for end user privacy but also for institutional privacy. De Vries et al. showed that Q-min is starting to spread little by little and clarified the performance penalty caused by applying it from observations on the Internet [

14].

Various studies have been conducted on Q-min to protect privacy in DNS.However, Q-min communication is not encrypted, so privacy protection is not sufficient.

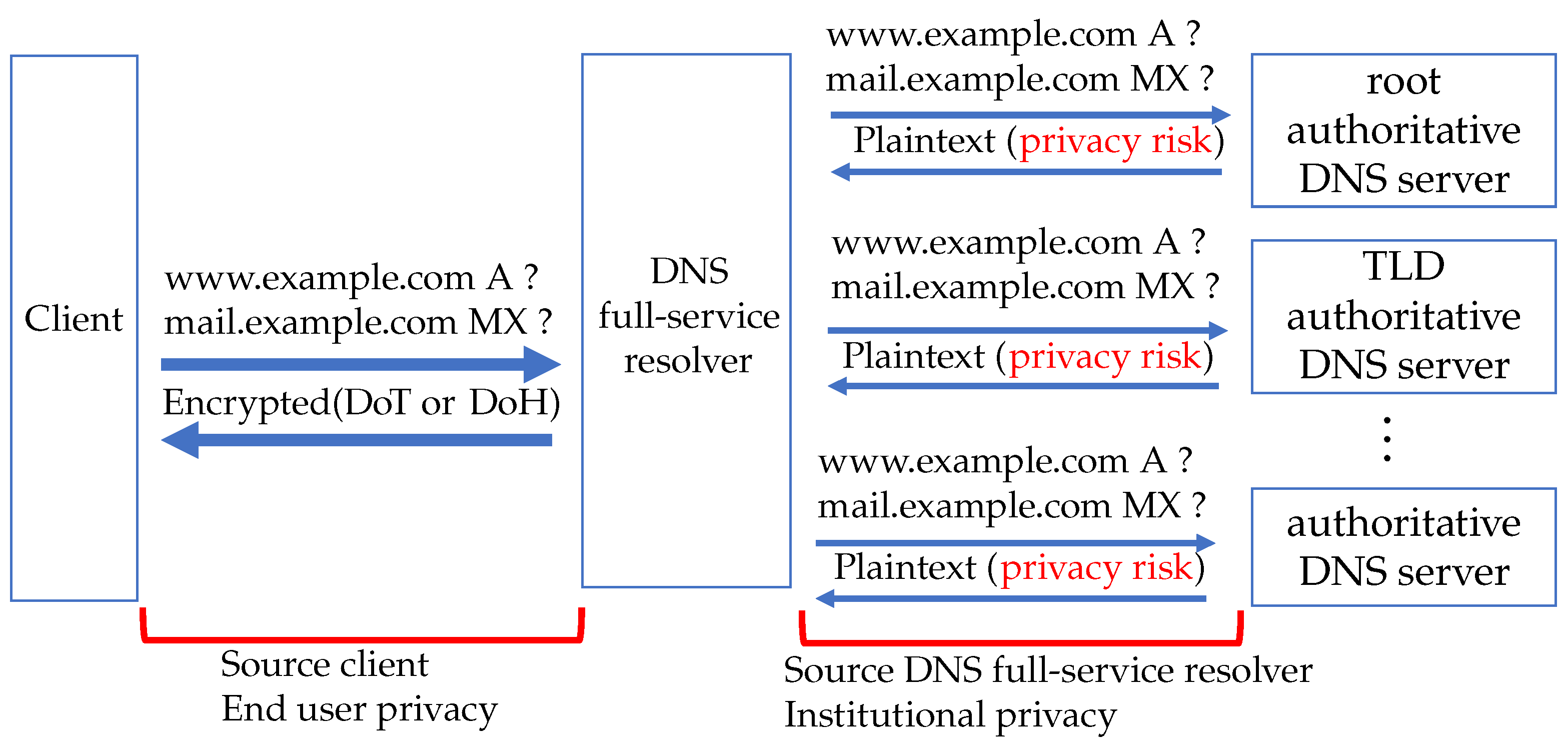

Figure 2 shows a specific example of privacy risk in Q-min. When a client queries “

www.example.com” to a DNS full-service resolver operated by an Institutional, the authoritative DNS server for the domain “example.com” will respond with the A record for “

www.example.com” in plaintext. If an attacker intercepts domain name resolution, they can determine the source DNS full-service resolver and the destination IP address. Therefore, we propose to encrypt all DNS communication to better protect privacy.

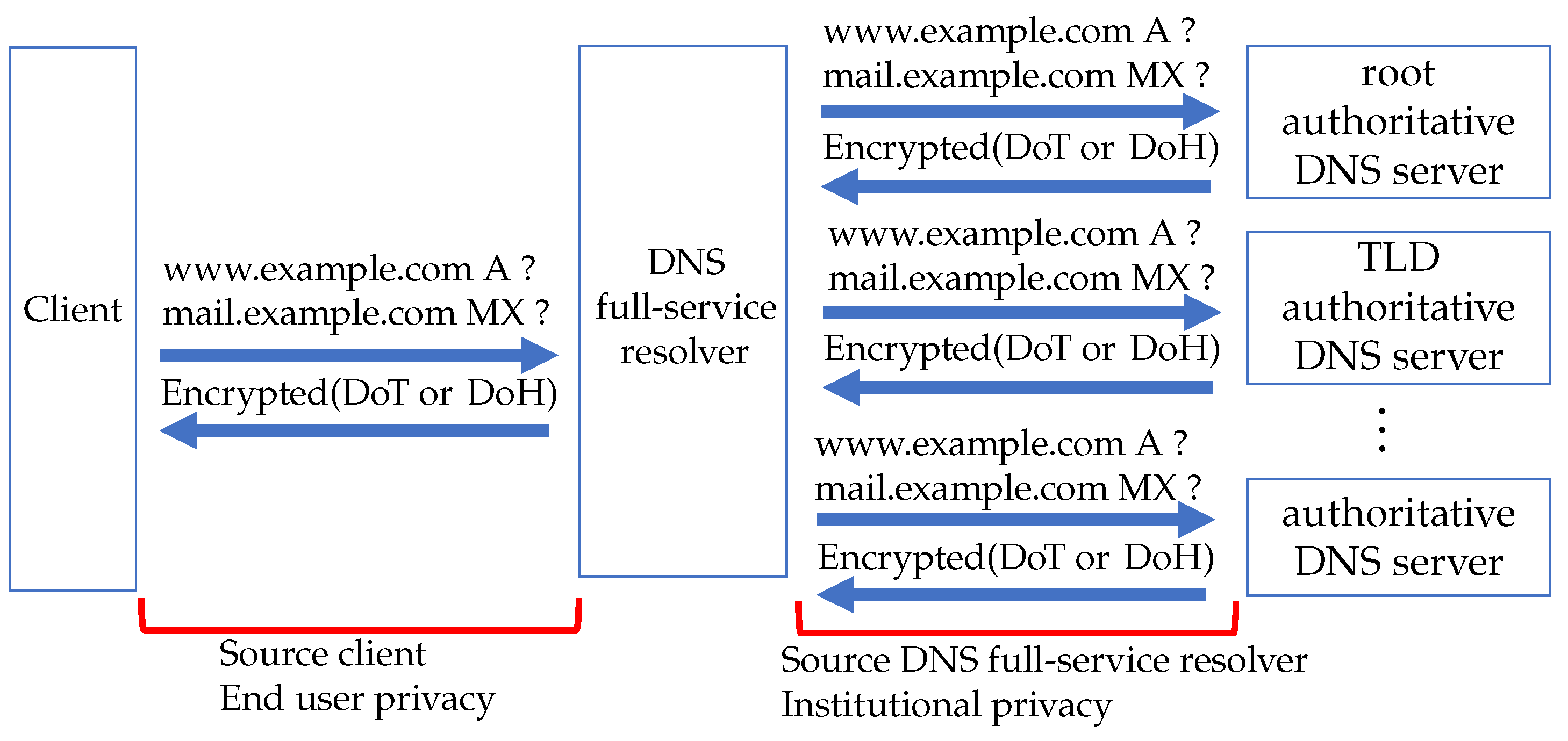

Figure 3 shows that an institution’s privacy has been enhanced by encrypting all DNS communications. The proposed method will be described in detail in the next chapter.

3. Proposed Method

As described in the previous section, “protecting end user privacy only” is insufficient to prevent privacy leaks, and a new concept called “institutional privacy” has been introduced. To achieve complete institutional privacy protection, we propose a novel framework for domain name resolution called the Full-DoH DNS architecture in this section. Generally, a new DNS encryption communication protocol, such as DoT, DoH, and DoQ, needs to be standardized by IETF. With comparing DoT and DoH, DoT uses a dedicated port of 853/TCP, while DoH uses port 443/TCP. DoH has the advantage of lower setup costs to be deployed, as typical institutional firewalls do not block port 443/TCP. DoQ is the best in performance [

15][

16].

However, high performance is not enough on the Internet. Ease of implementation and ease of control are also important indicators. Currently, QUIC adoption is limited[

17], and ISC bind9, a major DNS server software, does not support DoQ. QUIC is complex and difficult to analyze and debug, so adoption will take time [

18][

19]. Therefore, in the proposed framework, we intend to encrypt all DNS communication with DoH, and the replacement of DoH with DoQ in the future is an option.

-

Full-DoH DNS Architecture

-

We name the DNS architecture, which encrypts all the DNS communication using DoH in the entire domain name resolution process from the client to the authoritative DNS server, as Full-DoH DNS architecture.

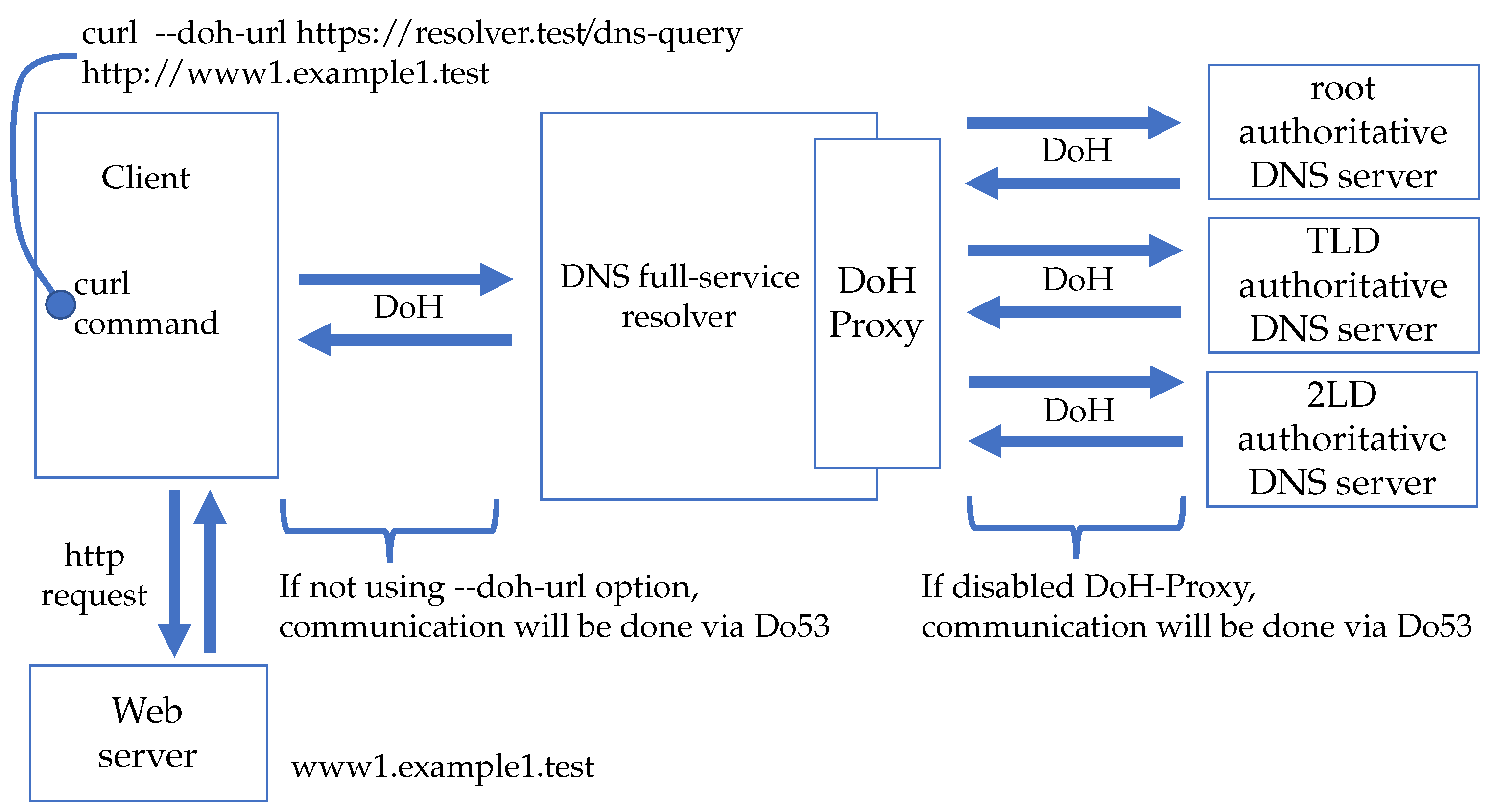

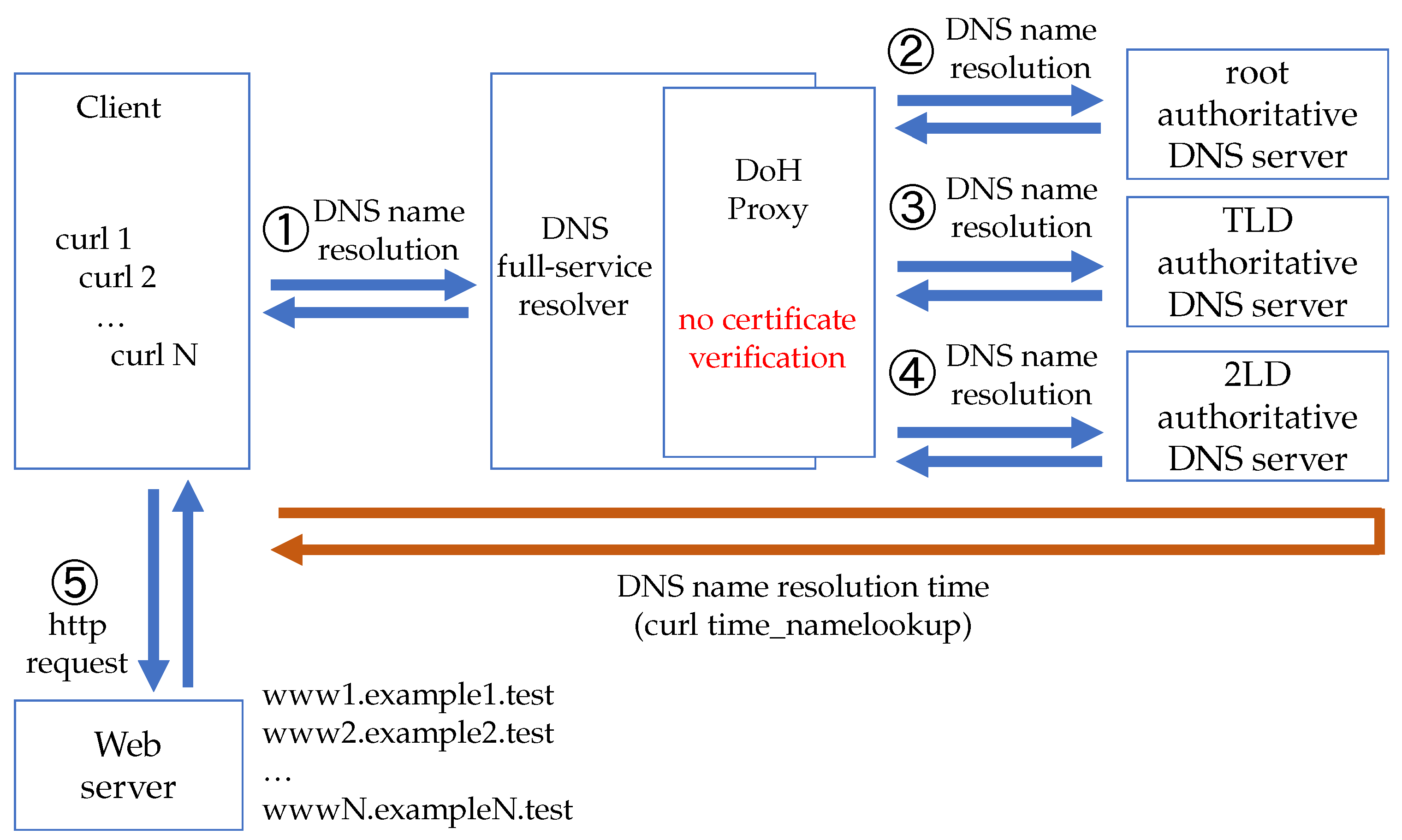

Figure 4 shows an overview of the proposed architecture, and the communication procedure is shown below.

The client (stub resolver) uses the DoH to send DNS queries to the DNS full-service resolver.

If the DNS full-service resolver has no DNS resource records cached for the domain name, the DNS full-service resolver iteratively queries the authoritative DNS servers using DoH for the domain name resolution.

The authoritative DNS server uses DoH to provide the corresponding referral information to the DNS full-service resolver until the final DNS response is obtained.

The DNS full-service resolver queries the corresponding authoritative DNS server based on the referral information.

The authoritative DNS server replies with the final answer to the DNS full-service resolver. In this example, we only use 2LD authoritative DNS servers.

The DNS full-service resolver replies to the final DNS response to the end client using DoH.

With the above procedure, stronger institutional privacy protection across the entire domain name resolution process can be expected using the proposed Full-DoH DNS architecture. In general, encrypted communications require more processing power than unencrypted communications, which results in slower response time. Therefore, from the point of view of practical use, it is necessary to check whether the Full-DoH architecture can provide domain name resolution service with an acceptable latency.

In addition to Full-DoH, in this paper, we name the method of domain name resolution defined in RFC2181, which performs all DNS communication in plaintext, as “Do53”. This method offers the highest performance, but it also poses a significant risk of privacy invasion since all communication is transmitted in plaintext. In addition, we name the method which combines DoH (communication between the end client to the DNS full-service resolver) and Do53 (communication between the DNS full-service resolver and the authoritative DNS server) as “DoH-Do53”. DoH-Do53 protects end user privacy by providing an encrypted connection between the end client and the DNS full-service resolver.

4. Prototype Implementation

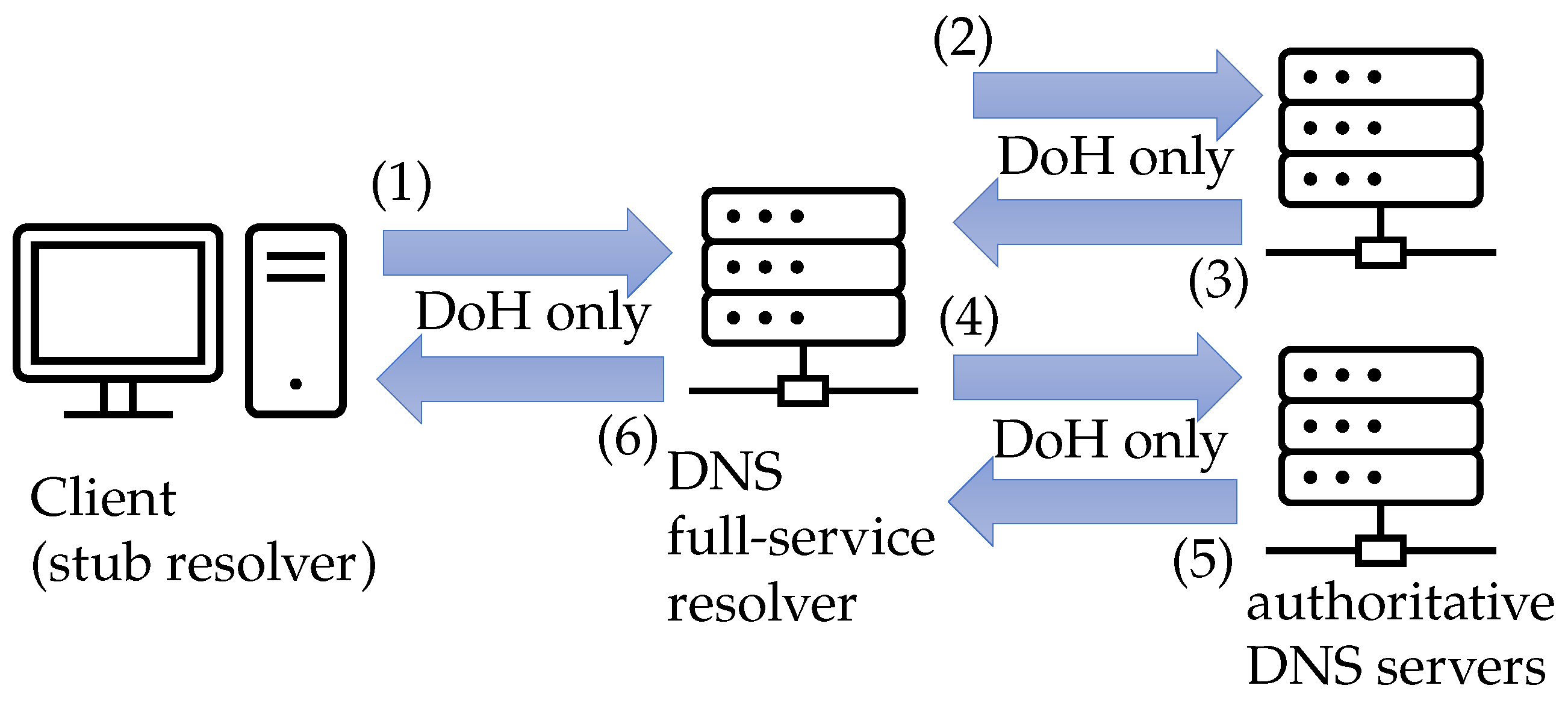

To demonstrate the feasibility of the proposed Full-DoH architecture, we implemented a prototype system.

Figure 5 shows the overview of the prototype system. The prototype system consists of several virtual machines constructed in one physical machine. Implementing Full-DoH DNS architecture requires a new functionality to send DoH requests from the DNS full-service resolver to authoritative DNS servers. We have developed DoH-Proxy that converts UDP communications sent from DNS server software into DoH requests. DoH-Proxy is implemented by combining Python’s dnslib library and Linux’s curl command. In the future, it is desirable to incorporate the capability to send DoH requests into DNS software such as bind9 or unbound.

In order to develop the Full-DoH DNS architecture, it is also necessary to have the root authoritative DNS server support DoH. However, since it is impossible to use the real root authoritative DNS servers in the implementation, we have constructed an experimental root authoritative DNS server. Accordingly, the Full-DoH DNS architecture can be realized in the local experimental environment by rewriting the DNS full-service resolver hint file to refer to our experimental root authoritative DNS servers.

We used bind9 for our DNS full-service resolver and all authoritative DNS servers. By listening to Do53 and DoH ports, bind9 can compare the domain name resolution latencies of non-encrypted and encrypted communication. Moreover, a TLS server certificate is required for DoH communication on each server. We created a root certificate authority on the prototype and installed the root certificate on the end client and DNS full-service resolver.

In order to perform domain name resolution in DoH DNS architecture, it is necessary to obtain the IP address of the DNS full-service resolver to which the domain name resolution is requested. We used the client’s hosts file in our prototype environment, assuming we had pre-specified an authoritative DNS full-service resolver.

We prepared 1 zone with 1000 A resource records for the TLD authoritative DNS server in the prototype environment and 200 zones with 1000 A resource records for each in the 2LD authoritative DNS server. The IP addresses of all A resource records are set to the IP addresses of the web servers prepared in the experimental environment.

By using the prototype system described above, we performed feature evaluation and performance evaluation for the proposed Full-DoH DNS architecture.

5. Evaluation

This section presents the evaluations for the proposed Full-DoH architecture on the prototype system. First, we show the experimental environment for evaluations. Next, we evaluate the feasibility of the proposed architecture as a feature evaluation. The first one explains the relationship between domain complexity and Full-DoH processing time. The second evaluation compares Full-DoH with the existing method DoH-Do53. Finally, we examine and analyze the impact of the certificate validation process on Full-DoH communication time.

5.1. Evaluation Environment

We constructed a local experimental environment using the prototype system presented in

Figure 5 in order to conduct the feature and performance evaluations. As described in the previous section, we built the experimental environment using server virtualization technology, Linux KVM, on a single machine. Specifically, the prototype system consists of 6 virtual machines, including an end client, a DNS full-service resolver, one for each of root, TLD, 2LD authoritative DNS servers, and a web server. The server machine and all guest machines used Ubuntu22.04 as OS, and the server software for DNS full-service resolver and authoritative DNS servers used bind9. The host machine has a 16-core, 32-thread CPU and 64GB of main memory. Each virtual machine has been allocated 4 virtual CPUs and 8GB of memory.

5.2. Feature Evaluation

The feature evaluation will confirm that Full-DoH and DoH-Do53 operate correctly in the prototype environment.

Figure 6 shows a scenario for feature evaluation. The specific procedures for the feature evaluation are as follows.

The end client sends an HTTP request to the web server using the curl command indicating the domain name.

All the network traffic was monitored using the tcpdump command on the end client, DNS full-service resolver, and each authoritative DNS server.

Confirm that the web content is displayed correctly on the end client.

As shown in

Figure 6, in order to use Full-DoH DNS architecture, after enabling the DoH-Proxy in the DNS full-service resolver, the end client accessed the web server by specifying the “–doh-url” option in the curl command. By checking the network traffic obtained by the tcpdump command, we confirmed that communication used port 443/TCP only, and DNS traffic was encrypted using HTTPS.

Similarly, in order to use DoH-Do53, after disabling the DoH-Proxy in the DNS full-service resolver, the end client accessed the web server by specifying the “–doh-url” option in the curl command. By checking the network traffic obtained by the tcpdump command, we confirmed that the DNS communication between the end client and the DNS full-service resolver uses port 443/TCP and that DNS traffic was encrypted using HTTPS. We also confirmed that port53/UDP was used to communicate between the DNS full-service resolver and each authoritative DNS server, and the DNS traffic was not encrypted.

Finally, in order to use Do53, after disabling the DoH-Proxy in the DNS full-service resolver, the end client accessed the web server without specifying the “–doh-url” option in the curl command. By checking the network traffic obtained by the tcpdump command, we confirmed that the port53/UDP was used for all communication on the DNS full-server resolver and authoritative DNS server, and the DNS traffic was not encrypted.

5.3. Performance Evaluation

In order to confirm the overhead of the domain name resolution in the proposed Full-DoH DNS architecture, we conducted a performance evaluation. We analyzed the domain name resolution time and the certificate verification time. The following subsection detail the evaluations and analyses.

5.3.1. Analysis of domain name resolution Time

Two things need to be clarified in the performance evaluation for the Full-DoH DNS architecture. One is how the structure of the domain name affects the domain name resolution time of the proposed Full-DoH DNS architecture. The more complex the domain name to be queried from the end client to the DNS full-service resolver, the more authoritative DNS servers the DNS full-service resolver has to query, which results in long domain name resolution time. The other is the difference in domain name resolution time between the existing DoH-DoH53 method and the proposed Full-DoH DNS architecture. The following sections detail the experimental configuration, evaluation procedures, results, and analysis, respectively.

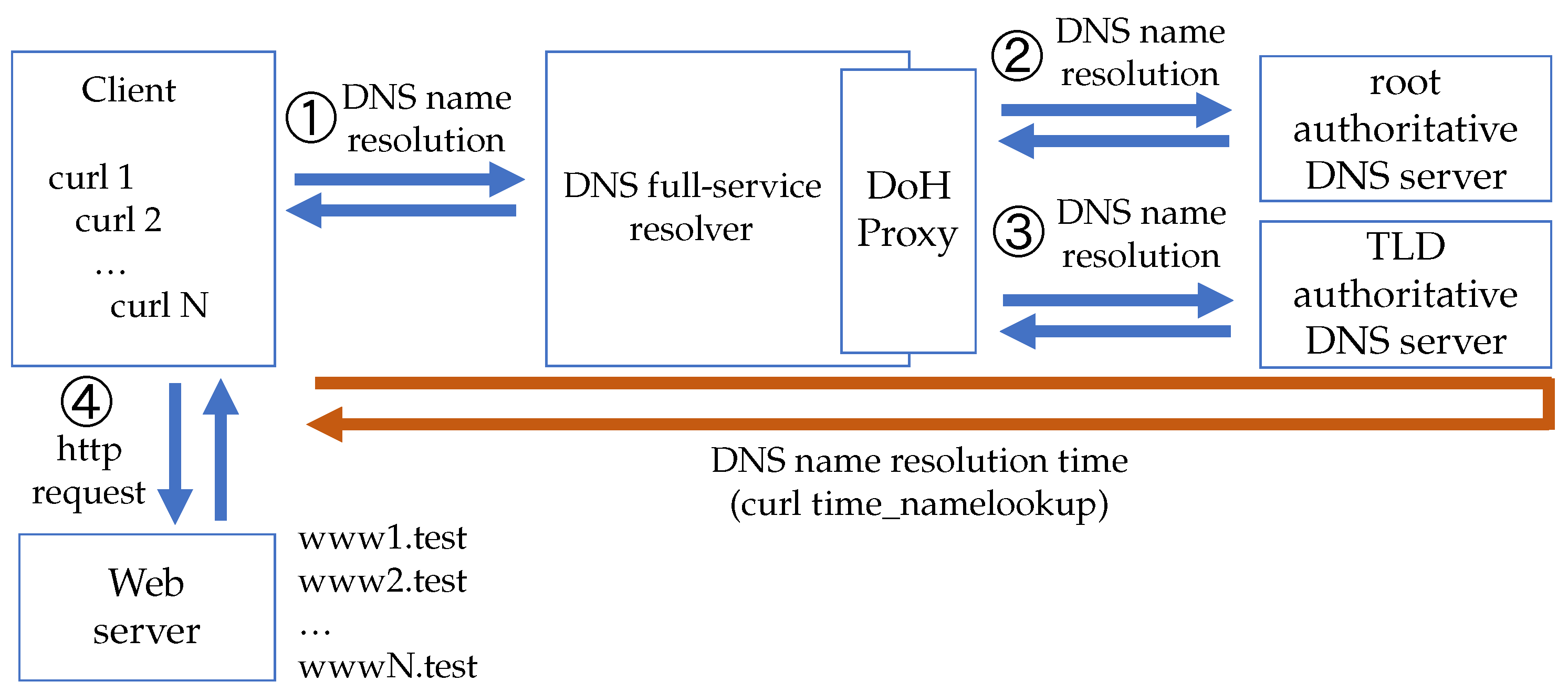

Experimental Configuration

Two experimental configurations were prepared to investigate the domain name resolution time of the existing method and proposed Full-DoH DNS architecture. The first type is for overhead measurement involving the DNS full-service resolver, root, and TLD authoritative DNS servers (the experiment in this configuration will henceforth be referred to as the “TLD Experiment”). The configuration overview is shown in

Figure 7, and the evaluation procedure is described in the following.

Execute the curl command from an end client trying to access the web server on the prototype system. The target acceptable domain name resolution time is 2 seconds, but the timeout value was set to 3 seconds to allow some margin.

The end client sends a DNS query to the DNS full-service resolver.

The DNS full-service resolver queries the authoritative DNS servers until it can obtain the final answer to the DNS query. At this time, the DNS full-service resolver caches only the root authoritative DNS server according to the authoritative DNS server’s zone configurations. On the other hand, we set the Time To Live (TTL) value to 0 in the TLD authoritative DNS server so that the DNS full-service resolver does not cache the corresponding DNS resource records.

The DNS full-service resolver replies to the result of the DNS query to the end client.

After the end client retrieves the web server content, it displays the domain name resolution time and finishes the process. In order to measure the domain name resolution time, we used the “–write-out time_namelookup” option with the curl command.

Restart the end client’s stub resolver service, the DNS full-service resolver, and bind9 with all authorized DNS servers to clear their caches. At this time, the root authoritative DNS server records cached in the DNS full-service resolver will also be cleared.

Add workload to the DNS full-service resolver by increasing the number of simultaneous connections of the curl command on the end client.

Repeat the above steps from 1 to 7 until a timeout occurs on the curl command.

In the experiment, we assume the concurrent curl connections as the workload created by multiple end clients. In order to perform a correct DNS performance evaluation, it is necessary to carefully check that the end client’s stub resolver or DNS full-service resolver does not use the cache. End clients access different FQDNs simultaneously to avoid using the stub resolver cache. We assume that results from the root authoritative DNS server will fit within the cache size of the DNS full-service resolver, while results from TLD authoritative DNS servers and beyond will overflow from the cache. This is achieved by setting the TTL value to 86400 for the zone configuration of the root authoritative DNS server and setting the TTL value to 0 for the zone configuration of the TLD authoritative DNS server. We also confirmed that DoH connections are not reused, and server certificates are not cached in our experimental procedure.

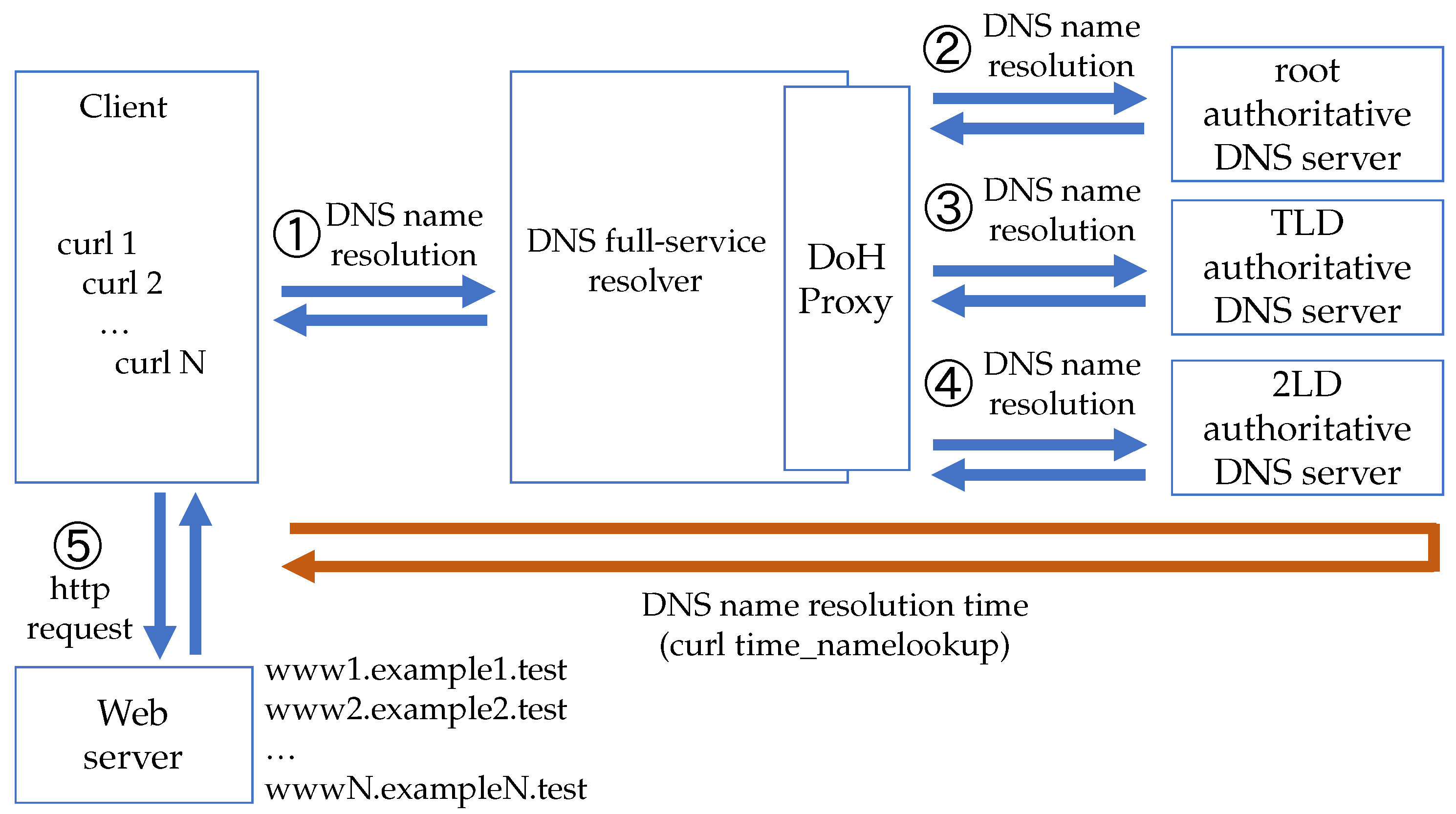

The second type is for overhead measurement involving the DNS full-service resolver, root, TLD, and 2LD authoritative DNS servers (the experiment in this configuration will henceforth be referred to as the “2LD Experiment”). The overview of the configuration is shown in

Figure 8. The difference from the first type is that 2LD authoritative DNS servers are added, which indicates one level of complexity was increased to the domain names that the end client accesses. The end client executes the curl command and accesses “

http://www1.example1.test”, “http://www2.example2.test”, ...,“

http://wwwN.exampleN.test” (N is the number of the concurrent curl command). Accordingly, when there is no overload on each server and no retransmission of communication occurs, the number of connections from the DNS full-service resolver to the TLD and 2LD authoritative DNS servers is the same as the number of simultaneous connections N of curl.

Evaluation Results

This paragraph presents the impact of domain-level complexity on domain name resolution time in the proposed Full-DoH architecture.

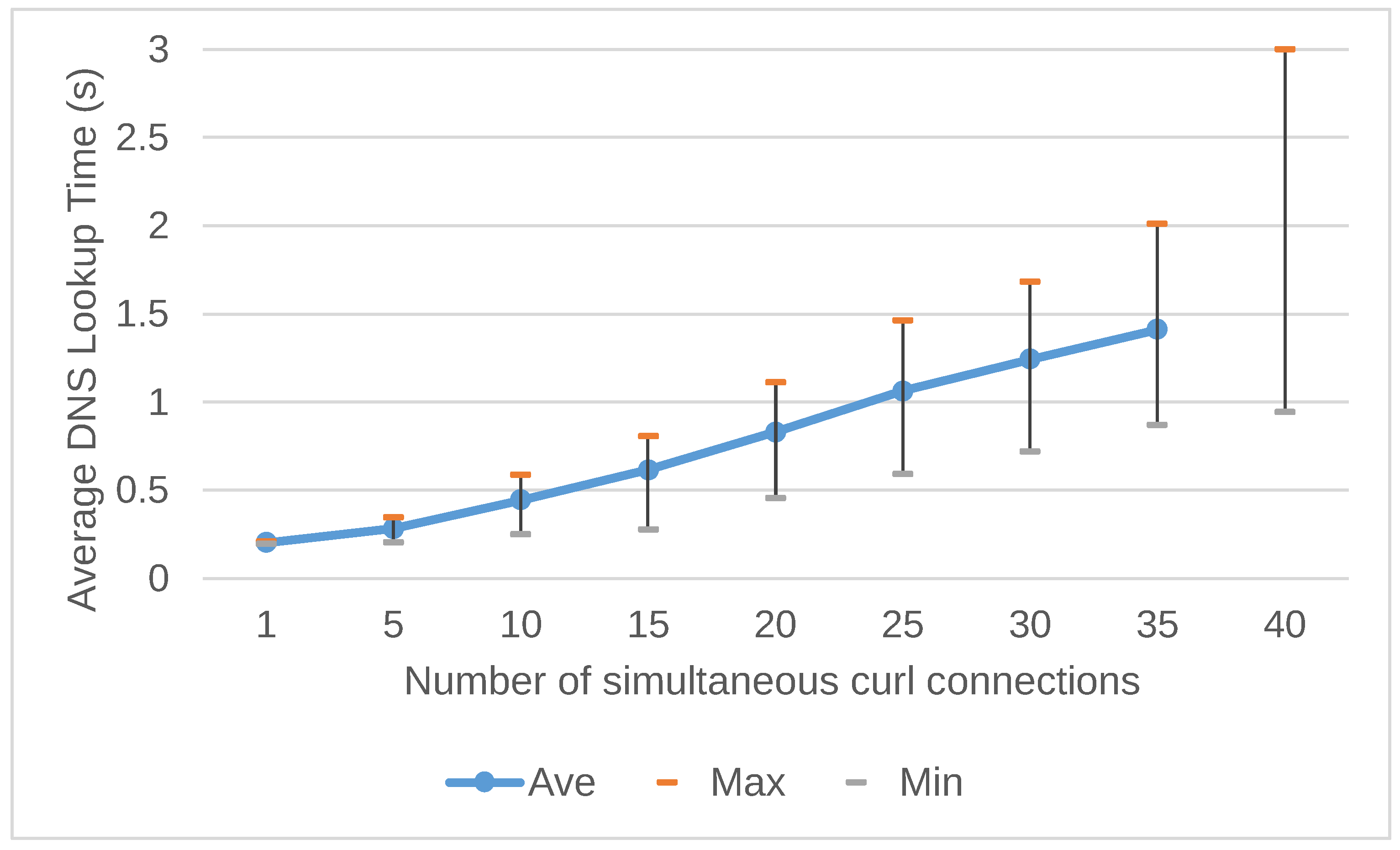

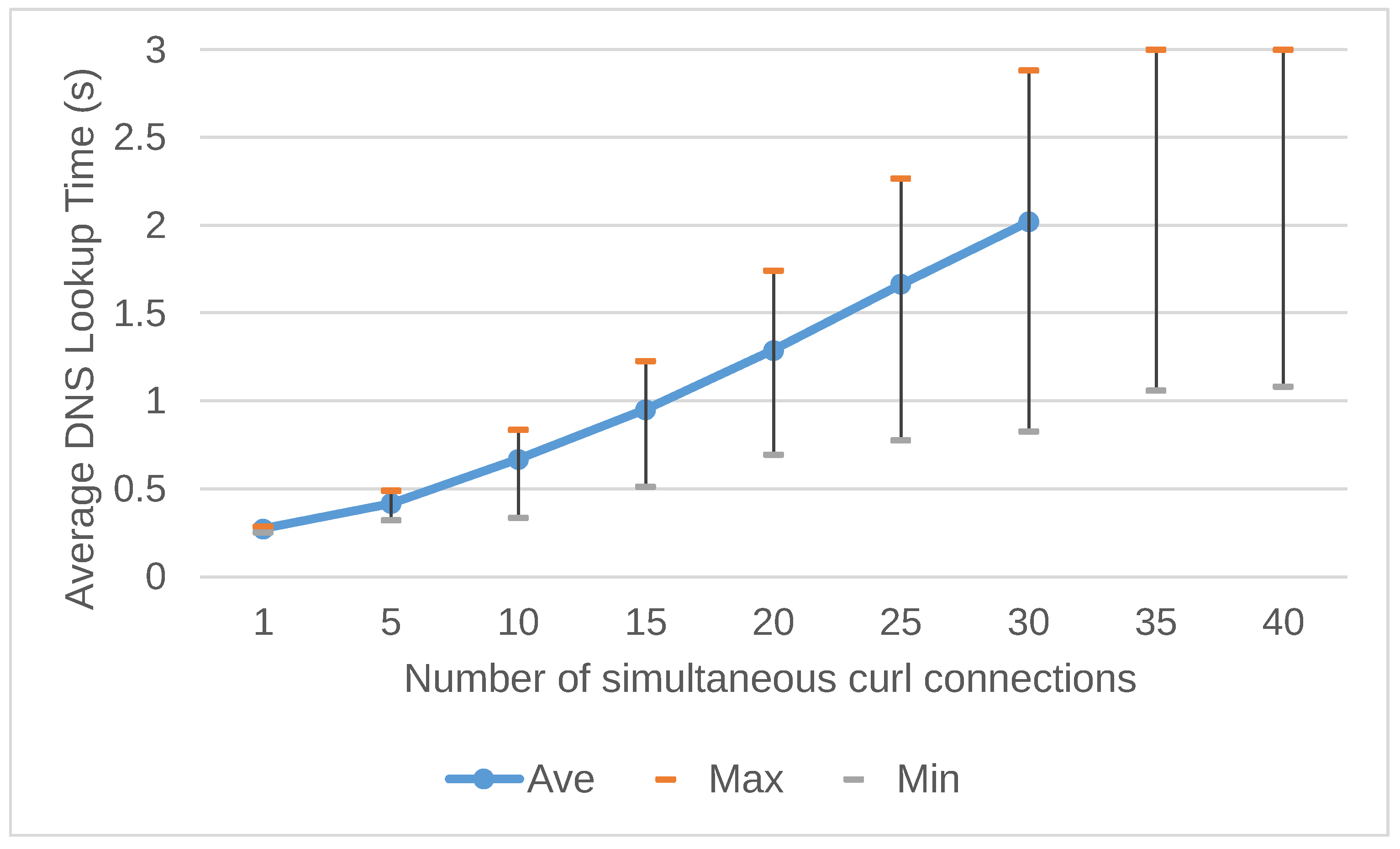

Figure 9 and

Figure 10 show the results of the “TLD Experiment” and “2LD Experiment” in the DoH-Do53 architecture. The results show the average, maximum, and minimum processing times for domain name resolution based on the concurrent workload of the curl connections. The result of the “TLD Experiment” in Full-DoH architecture shows the average processing time of up to 35 concurrent curl connections. After 40 simultaneous connections, there were one or more connections whose domain name resolution exceeded the timeout value of 3 seconds. Thus the correct average time could not be calculated. The fastest processing time for domain name resolution increases as the load number of concurrent connections increases. Similarly, as the number of concurrent connections increases, the processing time of the slowest domain name resolution also increases.

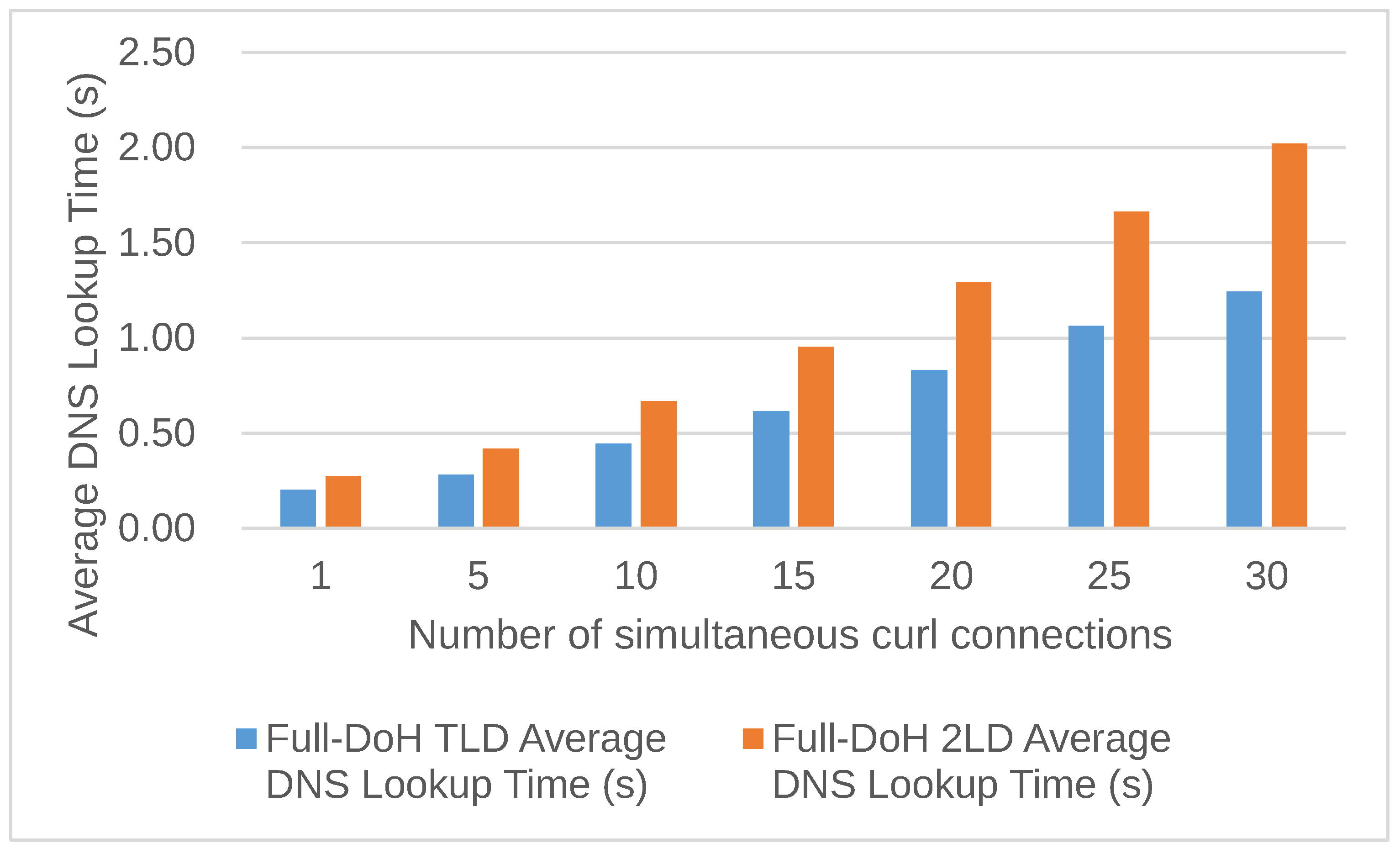

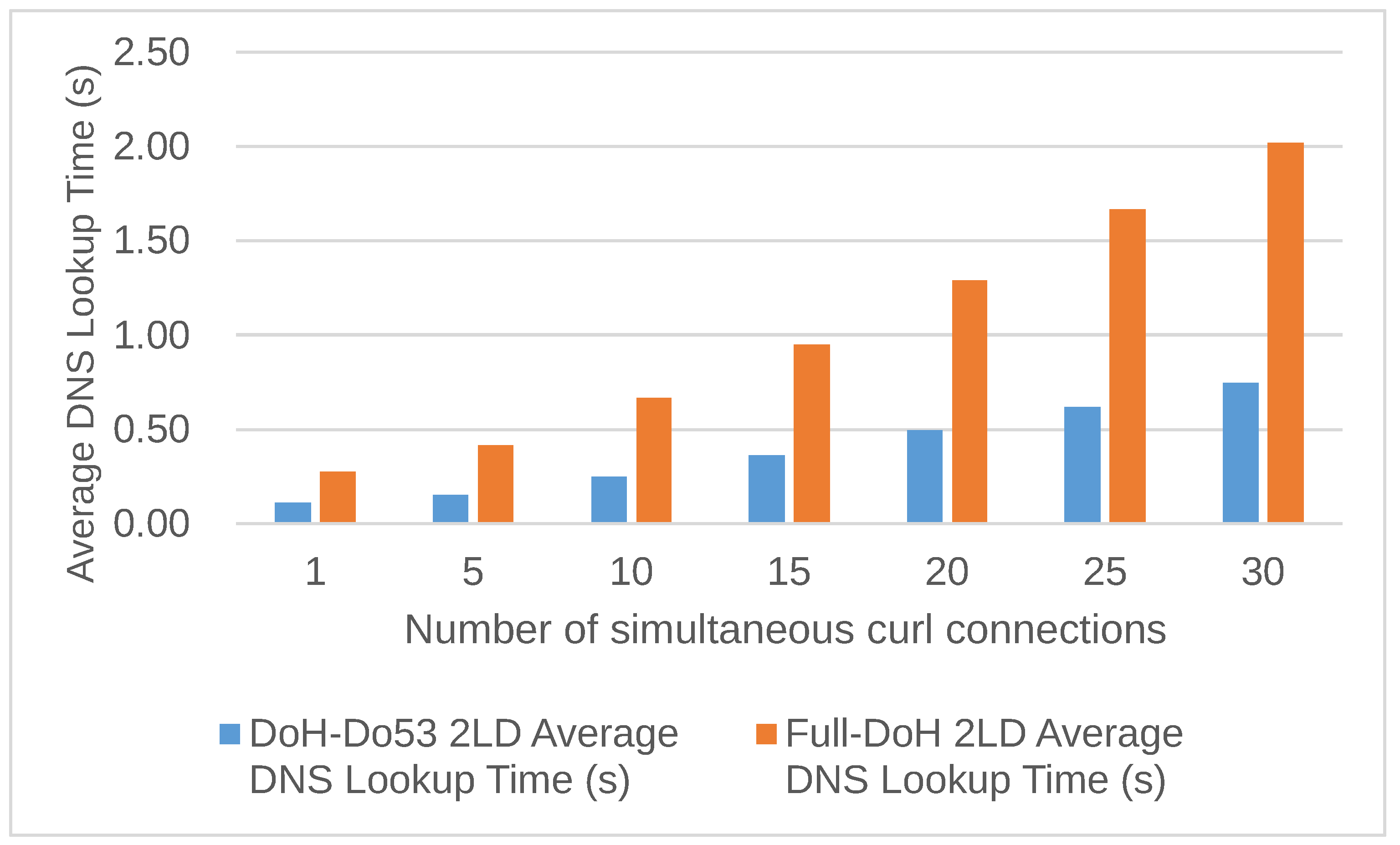

Figure 11 compares the average processing time for domain name resolution shown in

Figure 9 and

Figure 10.

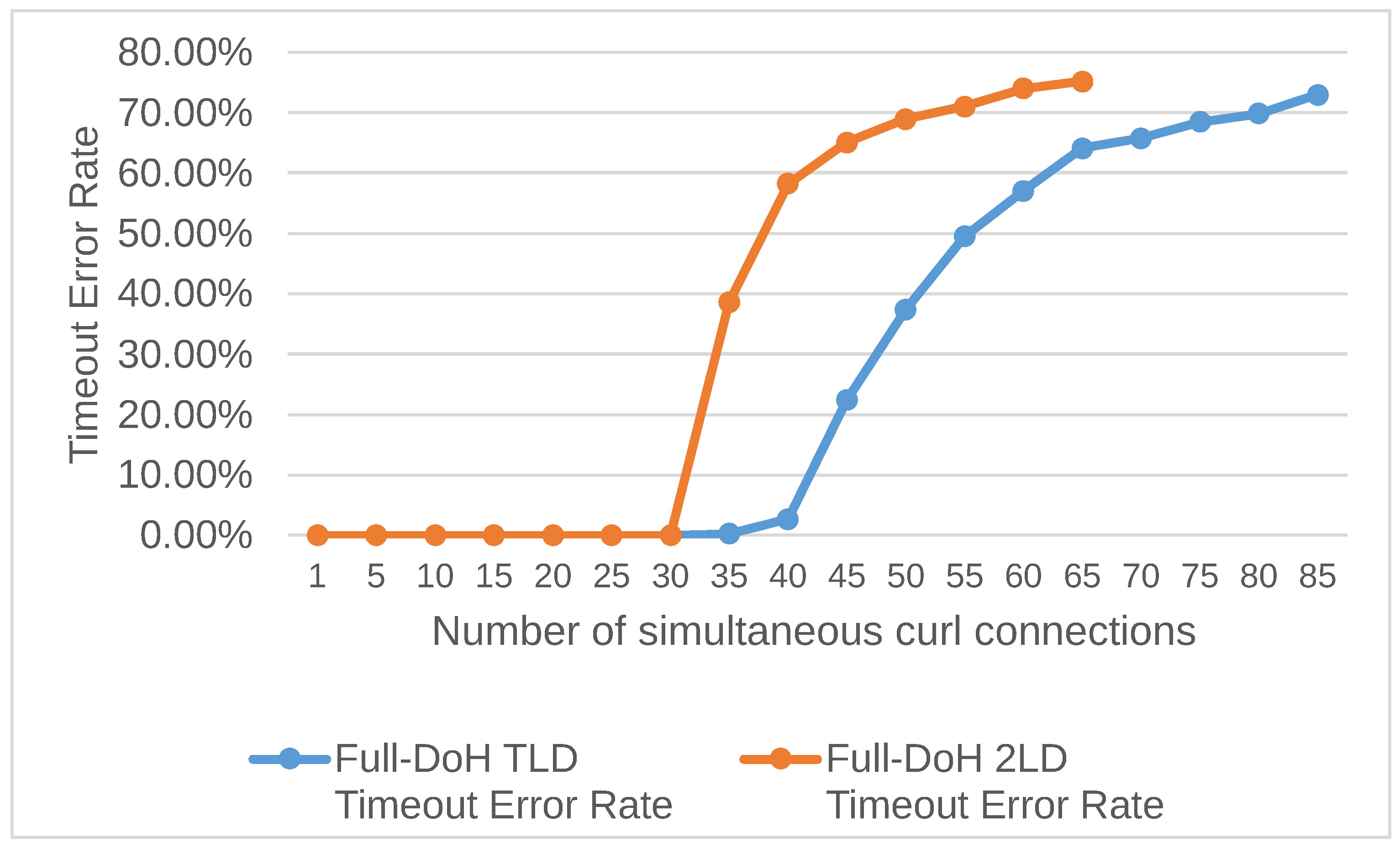

Figure 12 shows the percentage of DNS domain name resolution timeouts that occurred in the “TLD Experiment” and “2LD Experiment”, respectively. It shows that heavy DNS query loads tend to increase the rate at which curl commands time out.

Comparison with DoH-Do53

This paragraph introduces the difference in domain name resolution time between the existing method DoH-DoH53 and the proposed Full-DoH DNS architecture.

Figure 13 is a bar graph comparing the average processing time of the “2LD Experiment” for DoH-Do53 and the proposed Full-DoH DNS architecture. Without a heavy workload (only one connection), the domain name resolution for up to 2LD structure was about 0.11 seconds in DoH-Do53 and 0.27 seconds in the proposed Full-DoH architecture. From a usability perspective, 0.27 seconds is a sufficiently acceptable latency for domain name resolution. On the other hand, the proposed Full-DoH DNS architecture requires approximately 2.4 to 2.7 times longer than the DoH-Do53 method, depending on the workload conditions. Therefore, load distribution and performance improvement are necessary for real operation.

5.3.2. Analysis Of Certificate Verifications

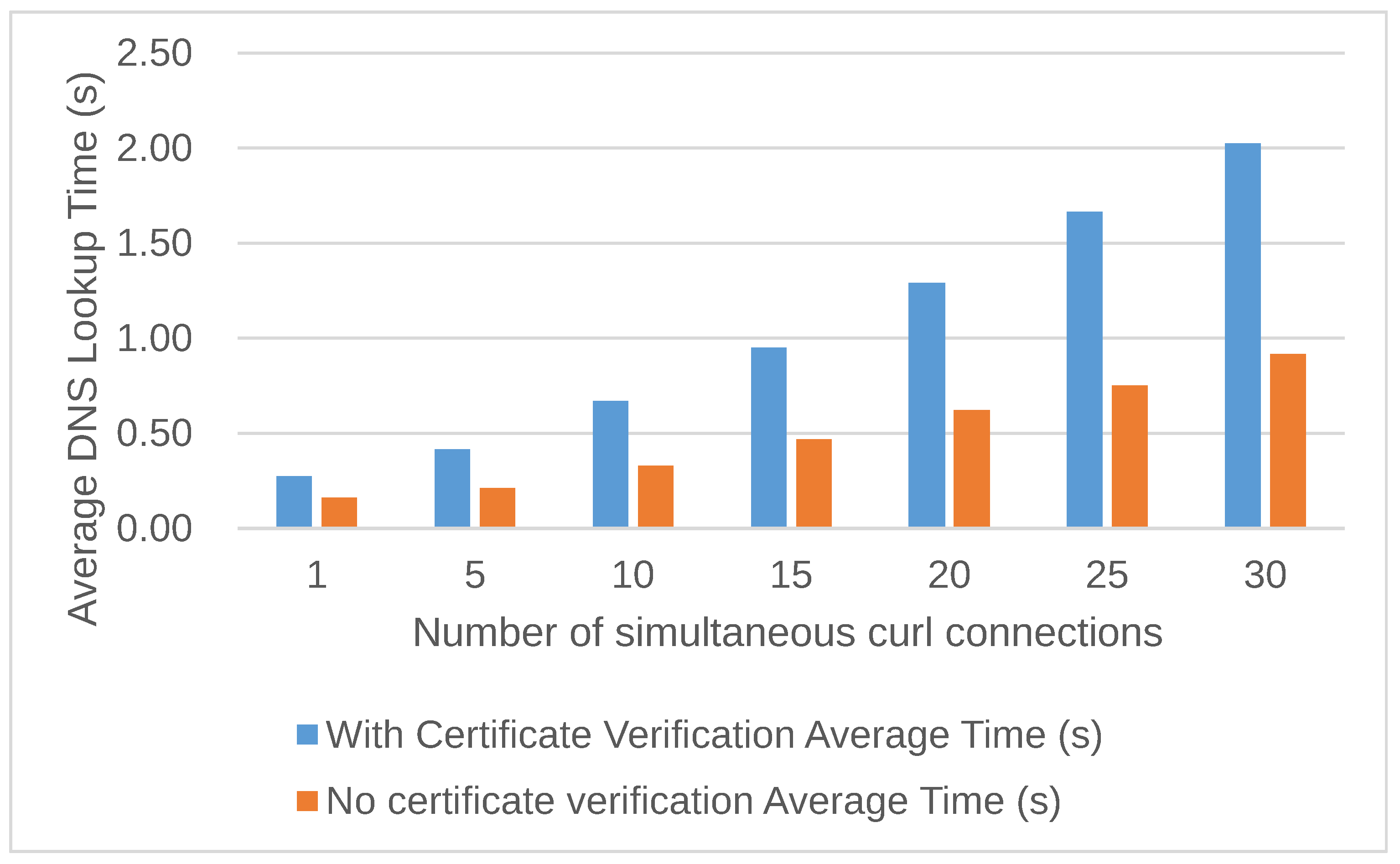

In the performance evaluation, we noticed that the higher the DNS query load, the more CPU the DNS full-service resolver tended to consume. Therefore, in the prototype system, we verified how much the server certificate verification in DoH connections affects the DNS domain name resolution processing time.

Figure 14 shows an overview of the experimental environment for the analysis of server certificate verification. In this experiment, the processing time of domain name resolution was measured by disabling the server certificate verification for only the DoH communication between the DNS full-service resolver and the authoritative DNS servers. That is because, during the workload evaluation, we noticed that the DNS full-service resolver tended to have higher CPU loads than authoritative DNS servers. Therefore, we measured how long the certificate verification in the DoH connection process affects the processing time when the certificate verification process is ignored in the DNS full-service resolver.

Figure 15 shows the comparison of processing time with and without certificate verification on the DNS full-service resolver in the Full-DoH architecture. In this environment, we measured the processing time for 2LD name resolution with certificate verification disabled. We confirmed that the processing time was shortened by approximately 41% to 54.9%, depending on the workload conditions.

6. Discussions

In this paper, we have implemented a prototype system and conducted feature and performance evaluations for the proposed Full-DoH DNS architecture involving the end client, DNS full-service resolver, root, TLD, and 2LD authoritative servers. The evaluation results confirmed that the proposed Full-DoH architecture obtained acceptable domain name resolution time for the domain names up to 2LD structure. In this section, we discuss the related issues to be deployed on the real Internet. Since the prototype implementation in this paper has a performance limitation, we describe some possible extensions in the following.

-

Implement a Proposed Architecture Within Popular DNS Server Software

We implemented the prototype system, including DoH-Proxy, in Python. However, it may be possible to speed up the process by implementing it in popular DNS server software such as bind9.

-

Maintaining and Reusing the Communication Connections

Maintaining a DoH connection for a specific time can reduce the communication overhead caused by the server certificate verification process that occurs at the time of connection establishment. However, this solution may require session management at the connection source and destination and a certain amount of memory resources.

-

Caching the Server Certificates at the Source of DNS Queries

The processing time of server certificate verification performed when connecting to DoHenabled authoritative DNS servers can be expected to be reduced by caching the server certificates at the connection source for a specific time.

-

Increase the Number of Servers

A typical load-balancing solution is to increase the number of authoritative DNS servers for each zone, such as root, TLD, and 2LD, etc., and perform load distribution for the DNS queries to the servers.

-

Use Dedicated Hardware for Server Certificate Verification

It is possible to speed up the server certificate verification process by using hardware specialized for processing TLS/SSL connections [

20].

In addition to the above possible solutions for performance improvement, we also plan to solve the following issues in future work. In this paper, we have confirmed that the proposed Full-DoH DNS architecture can achieve satisfactory speed in the prototype system. However, it is not yet clear whether the proposed Full-DoH architecture can provide sufficient performance on the Internet. Thus, further investigation is required to confirm if the domain name resolution time is satisfactory even when the structure of the domain name becomes more complex. Accordingly, first, we plan to deploy the proposed Full-DoH DNS architecture on our campus network connected to the Internet and gradually increase the scale to investigate its operability.

Next, in our experimental environment, the workload was concentrated on the DNS full-service resolver. However, depending on the network topology, the workload may be concentrated on the root, TLD, and 2LD authoritative DNS servers. Thus, it is necessary to investigate how effective it is to maintain the communication sessions between the DNS full-service resolver and authoritative DNS servers and the cache functionality for the server certificates.

Moreover, currently, there is no concrete method to notify the end client whether the DNS full-service resolver performs encrypted communication with the authoritative DNS servers. Therefore, we are considering adding a notification functionality about the feature to the end client.

Finally, while encrypting the DNS communications to enhance privacy protection, we must consider the impact on the existing security systems. For example, the proposed Full-DoH DNS architecture also encrypts the DNS traffic sent by malware. Accordingly, the existing security systems may be unable to detect the malware from the DNS traffic analysis. It has been reported that some approaches using machine learning were effective for this issue [

21][

22]. The trade-off between privacy protection and security monitoring also needs to be considered.

7. Conclusion

Conventional DNS communication is done in plaintext, which is insufficient for privacy protection. The IETF standards regarding DNS communication encryption between the end clients and DNS full-service resolver only enhance the end user privacy protection. In contrast, institutional privacy protection has not been achieved. This is because the DNS communication between a DNS full-service resolver and authoritative DNS servers is still in plaintext, which has the risk of institutional privacy leakage. Therefore, in this paper, we proposed a framework for institutional privacy considering domain name resolution and Full-DoH DNS architecture in order to mitigate the privacy leakage risk in institutional networks. The proposed Full-DoH DNS architecture encrypts all DNS communication during the domain name resolution process, which involves end clients, DNS full-service resolver, and authoritative DNS servers so that it not only can prevent eavesdropping in the communication links but also can protect the end user privacy as well as the institutional privacy.

We implemented a prototype system in a local experimental environment and conducted the feature and performance evaluations. Specifically, we developed a DoH-Proxy, which is supposed to be running between a DNS full-service resolver and authoritative DNS servers to transform the normal DNS traffic to DoH traffic. The feature evaluation results confirmed that the prototype system worked correctly with up to 2LD domain name structure in the authoritative DNS servers indicating the proposed Full-DoH DNS architecture can be achieved. In addition, the performance evaluation results confirmed that the proposed Full-DoH DNS architecture obtained acceptable domain name resolution time with up to 2LD domain name structure. Furthermore, we also analyzed the overhead of concurrent domain name resolution requests from the end client and the cost of server certificate verification. The analysis results confirmed that the main reason for extra overhead in the proposed Full-DoH DNS architecture is the server certificate verification process on the DNS full-service resolver. We also introduced some possible solutions for its improvement.

In future work, we plan to evaluate the proposed Full-DoH DNS architecture on a campus network connected to the Internet to confirm the effectiveness and investigate the proper solutions for the potential issues introduced in the discussion. We also plan to investigate the performance change while increasing the structure level of the domain names and the solutions for performance improvement.

Author Contributions

S.S. and Y.J. conceived of the presented idea. S.S. developed software and implemented and experimented with prototypes. Y.J. and K.I. supervised the findings of this work. All authors provided critical feedback and contributed to the analysis of the experimental results. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Data Availability Statement

Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| DNS |

Domain Name System |

| TLD |

Top-level domain |

| 2LD |

Second-level domain |

| ISP |

Internet Service Provider |

| IETF |

Internet Engineering Task Force |

| DoT |

DNS over TLS |

| TLS |

Transport Layer Security |

| DoH |

DNS over HTTPS |

| HTTP |

Hypertext Transfer Protocol |

| HTTPS |

Hypertext Transfer Protocol Secure |

| Q-min |

Query Name Minimization |

| LGBTQ |

Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, Transgender, and Queer |

| TCP |

Transmission Control Protocol |

| UDP |

User Datagram Protocol |

| DoQ |

DNS over QUIC |

| QUIC |

Quick UDP Internet Connections |

| FQDN |

Fully Qualified Domain Name |

| Linux KVM |

Linux for Kernel-based Virtual Machine |

| TTL |

Time To Live |

| Do53 |

DNS over UDP/TCP |

| SSL |

Secure Socket Layer |

References

- Elz, R.; Bush, R. Clarifications to the DNS Specification. RFC 2181, 1997. accessed on 21 April 2023. [CrossRef]

- Farrell, S.; Tschofenig, H. Pervasive Monitoring Is an Attack. RFC 7258, 2014. accessed on 21 April 2023. [CrossRef]

- Dickinson, S.; Gillmor, D.K.; Reddy.K, T. Usage Profiles for DNS over TLS and DNS over DTLS. RFC 8310, 2018. [CrossRef]

- Hoffman, P.E.; McManus, P. DNS Queries over HTTPS (DoH). RFC 8484, 2018. accessed on 21 April 2023. [CrossRef]

- Imana, B.; Korolova, A.; Heidemann, J. Institutional privacy risks in sharing dns data. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the Applied Networking Research Workshop, 2021, pp. 69–75. [CrossRef]

- Bortzmeyer, S.; Dolmans, R.; Hoffman, P.E. DNS Query Name Minimisation to Improve Privacy. RFC 9156, 2021. accessed on 21 April 2023. [CrossRef]

- Sunahara, S.; Jin, Y.; Iida, K. A proposal of DoH-based domain name resolution architecture including authoritative DNS servers. In Proceedings of the 2022 32nd International Telecommunication Networks and Applications Conference (ITNAC). IEEE, 2022, pp. 1–3. [CrossRef]

- Huitema, C.; Dickinson, S.; Mankin, A. DNS over Dedicated QUIC Connections. RFC 9250, 2022. accessed on 21 April 2023. [CrossRef]

- Iyengar, J.; Thomson, M. QUIC: A UDP-Based Multiplexed and Secure Transport. RFC 9000, 2021. accessed on 21 April 2023. [CrossRef]

- Böttger, T.; Cuadrado, F.; Antichi, G.; Fernandes, E.L.; Tyson, G.; Castro, I.; Uhlig, S. An Empirical Study of the Cost of DNS-over-HTTPS. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the Internet Measurement Conference, 2019, pp. 15–21. [CrossRef]

- Chhabra, R.; Murley, P.; Kumar, D.; Bailey, M.; Wang, G. Measuring DNS-over-HTTPS performance around the world. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the 21st ACM Internet Measurement Conference, 2021, pp. 351–365. [CrossRef]

- Hounsel, A.; Borgolte, K.; Schmitt, P.; Holland, J.; Feamster, N. Comparing the effects of DNS, DoT, and DoH on web performance. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of The Web Conference 2020, 2020, pp. 562–572. [CrossRef]

- Bradshaw, S.; DeNardis, L. Privacy by infrastructure: The unresolved case of the domain name system. Policy & Internet 2019, 11, 16–36. [CrossRef]

- de Vries, W.B.; Scheitle, Q.; Müller, M.; Toorop, W.; Dolmans, R.; van Rijswijk-Deij, R. A first look at QNAME minimization in the domain name system. In Proceedings of the Passive and Active Measurement: 20th International Conference, PAM 2019, Puerto Varas, Chile, March 27–29, 2019, Proceedings 20. Springer, 2019, pp. 147–160.

- Kosek, M.; Doan, T.V.; Granderath, M.; Bajpai, V. One to Rule Them All? A First Look at DNS over QUIC. In Proceedings of the Passive and Active Measurement: 23rd International Conference, PAM 2022, Virtual Event, March 28–30, 2022, Proceedings. Springer, 2022, pp. 537–551. [CrossRef]

- Kosek, M.; Schumann, L.; Marx, R.; Doan, T.V.; Bajpai, V. DNS privacy with speed? evaluating DNS over QUIC and its impact on web performance. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the 22nd ACM Internet Measurement Conference, 2022, pp. 44–50. [CrossRef]

- Zirngibl, J.; Buschmann, P.; Sattler, P.; Jaeger, B.; Aulbach, J.; Carle, G. It’s over 9000: analyzing early QUIC deployments with the standardization on the horizon. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the 21st ACM Internet Measurement Conference, 2021, pp. 261–275. [CrossRef]

- Marx, R.; Lamotte, W.; Reynders, J.; Pittevils, K.; Quax, P. Towards QUIC debuggability. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the Workshop on the Evolution, Performance, and Interoperability of QUIC, 2018, pp. 1–7. [CrossRef]

- Marx, R.; Piraux, M.; Quax, P.; Lamotte, W. Debugging QUIC and HTTP/3 with qlog and qvis. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the Applied Networking Research Workshop, 2020, pp. 58–66. [CrossRef]

- Isobe, T.; Tsutsumi, S.; Seto, K.; Aoshima, K.; Kariya, K. 10 Gbps implementation of TLS/SSL accelerator on FPGA. In Proceedings of the 2010 IEEE 18th International Workshop on Quality of Service (IWQoS). IEEE, 2010, pp. 1–6. [CrossRef]

- Mitsuhashi, R.; Jin, Y.; Iida, K.; Shinagawa, T.; Takai, Y. Malicious DNS Tunnel Tool Recognition using Persistent DoH Traffic Analysis. IEEE Transactions on Network and Service Management 2022. [CrossRef]

- Alenezi, R.; Ludwig, S.A. Classifying DNS Tunneling Tools For Malicious DoH Traffic. In Proceedings of the 2021 IEEE Symposium Series on Computational Intelligence (SSCI). IEEE, 2021, pp. 1–9. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).