1. Introduction

During the last 30 years, southern highbush blueberries (SHB) have replaced rabbiteye cultivars in Florida due to their earlier ripening and potentially high-yielding capacity, doubling Florida’s blueberry production capabilities (Borisova et al., 2018; Lang and Parrie, 1992). In 2021, Florida produced 12,815 tons of berries valued at $78 million USD (USDA-NASS, 2022) and mostly directed to the fresh market. Southern highbush blueberries are interspecific hybrids of Vaccinium corymbosum, V. virgatum, and V. darrowi (Ericaceae) that are well adapted to mild winter climates or “low chill” areas, such as Florida, and produce the first U.S.-produced blueberries to reach the market in early spring (Buck, 2022; Evans and Ballen, 2017; Lang and Parrie, 1992).

The blueberry bud mite,

Acalitus vaccinii Keifer (Acari: Eriophyidae), was considered the only mite pest of blueberries that would occasionally infest SHB in Florida (Cromroy and Kuitert, 2017; Weibelzahl and Liburd, 2017). However, in 2016 a major tetranychid outbreak was reported in Florida at a commercial planting where SHB was experimentally grown under protected structures [

9]. In the following years, Florida and Georgia SHB growers experienced severe losses estimated between

$500,000 to

$750,000 USD due to outbreaks of spider mites (Tetranychidae) (Lopez and Liburd, 2020). The southern red mite (SRM),

Oligonychus ilicis McGregor (Acari: Tetranychidae), was identified in 2019 as the tetranychid pest causing severe damage characterized by leaf bronzing and stunted plants in various blueberry cultivars across both states (Lopez and Liburd, 2020). This generalist plant pest is also known as the red mite or the coffee red mite. It feeds on more than 34 host plants, most of them ornamental bushes and tree species such as camellias, azaleas, hollies, and eucalyptus. It also feeds on fruit crops such as coffee, strawberry, and cranberry (Manners, 2019; Denmark et al., 2006).

Oligonychus ilicis develops several overlapping generations each year in Florida where optimal conditions (25±2 °C) can be found during the fall and spring each year. But it is during the cooler months in the fall with prolonged periods of high humidity and dry conditions when populations increase causing economic damage; furthermore, O. ilicis can survive the winter without undergoing diapause (Manners, 2019; Franco et al., 2008; Denmark et al., 2006). In SHB, O. ilicis reproduce on the leaf’s lower surface, leaving a waxy and white accumulation of sheds after large populations have been established. Most SRMs are found in the mid to lower branches and start moving up the foliage as the populations grow (Lopez and Liburd, 2020). Bronzed-colored leaves are the characteristic symptom associated with SRM injury in ornamental crops, as well as SHB, and the intensity of the bronzing is proportional to the degree of internal leaf damage (Fahl et al., 2007).

Broad-spectrum insecticides such as pyrethroids, organophosphates, and carbamates are the main option used by growers for controlling mite and insect pests due to their effectiveness and inexpensive cost. However, farmers end up spraying often weekly to maintain control and usually use a short list of chemicals in their rotation programs, turning blueberry plantings into high-chemical input systems that can decimate natural enemies and cause secondary pest outbreaks (Rodriguez-Saona et al., 2019; Williamson et al., 2019a).

Southern red mite outbreaks have been detected in SHB for various consecutive years. They could become an established key pest of blueberries if integrated pest management (IPM) programs are not modified to include effective suppressive tactics against this tetranychid pest, including reduced-risk miticidal tools that are compatible with natural enemies including predatory mites. This paper reports the evaluation of miticidal options for use in commercial SHB plantings against O. ilicis. Additionally, it estimates the level of awareness of Florida blueberry growers regarding SRM infestations and provides the first report of naturally occurring predatory mites associated with SRM in commercial blueberry plantings from North Central Florida.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Grower Survey

Data on the knowledge related to SRM among blueberry stakeholders in Florida were collected to identify the level of awareness regarding SRM and design adequate educational materials available to the grower community. Data were collected during two blueberry meetings: the 2020 Florida Blueberry Growers Association (FBGA) Spring Field Day held in Citra, FL on March 10, 2020, and the 2020 Blueberry Growers Virtual Meeting on July 28, 2020. Forty blueberry growers and extension agents attended the virtual meeting, and 30 growers the field day. Growers participated only once in a survey that consisted of completing nine questions (10-minute survey) provided by the authors of this study. The questions were set up as short open and multiple-choice questions and are listed in the appendix. The survey was responded to in person during the field day and provided as a Google Form during the virtual meeting. The questions focused on the type of blueberry plantings they grow, their confidence to identify SRM, and their observations of mite presence or any blueberry damage symptoms caused by mite feeding. All surveys were anonymous, approved by the University of Florida’s IRB (protocol number 202000571), and consent forms were provided to the attendants prior to responding to the survey. Responses from both meetings were pooled together for analysis.

2.2. Plant Culture

A field trial was conducted between October 10th and November 10th, 2020, at a commercial 303-ha blueberry farm located in Waldo, FL, USA (29°47’29.4648’’N, 82°7’9.8832’’W). Four 152-m long rows were randomly chosen from an SHB planting naturally infested with SRM. Bushes (cultivar #13123) were 1.5–2-m high and approximately three years old. Blueberry bushes were spaced 1-m apart, planted in single rows 2-m apart, drip irrigated, and occasionally used overhead irrigation.

2.3. Miticide Performance

A randomized complete block design with four replicates was used to evaluate nine treatments consisting of eight miticides and water (control) as shown in Table 1. Plots consisted of 12 bushes followed by five untreated bushes, used as a buffer zone between plots. One row of blueberries was left untreated as a buffer zone between treated rows (~5-m apart). Two miticides applications were conducted on October 13 and October 27, 2020 (15-day intervals) using a CO2 sprayer with Teejet hollow cone spray cores D3 disk DC 25 (Spraying systems Co., Keystone Heights, FL) and 500-L of water/ha for each application. No pesticides were applied within two weeks before starting the trial.

Table 1.

List of miticides and recommended rate tested for control of southern red mites, Oligonychus ilicis.

Table 1.

List of miticides and recommended rate tested for control of southern red mites, Oligonychus ilicis.

Treatment

(Active Ingredient, AI) |

Miticide

(Brand Name) |

Product Rate: AI/ha |

Manufactory |

| Spiromesifen |

ALPB2017 |

1.25-L |

Bayer, St. Louis, MO |

| Acequinocyl |

Kanemite® 15SC |

2.07-L |

Arysta LifeScience, LLC, Cary, NC |

| Sulfur + molasses |

Sulfur-CARB™ |

3% v/v |

Terra Feed, LLC, Plant City, FL |

| Sulfur |

Cosavet® DF |

13.6-kg |

Sulfur Mills LTD, Mumbai, India |

| Bifenazate |

Acramite® 4SC (low rate) |

0.88-L |

Arysta LifeScience, LLC, Cary, NC |

| Bifenazate |

Acramite® 4SC (high rate) |

1.18-L |

Arysta LifeScience, LLC, Cary, NC |

| Fenpyroximate |

Portal® EC |

2.38-L |

Nichino America, Inc.,

Wilmington, DE |

| Fenazaquin |

Magister® SC |

2.65-L |

Gowman Co., Yuma, AZ |

| Control (water) |

NA |

NA |

NA |

2.4. Plant Damage Assessment

Bronzing caused by SRM feeding was rated on four randomly selected bushes 3-DBA (on 10/10/2020) and 14-DAA after the second application (on 10/27/2020) using an arbitrary plant damage index based on the percentage of bronzed foliage per plant as follows: 0= no bronzing; 1= 1 ≥ 25% (low bronzing); 2= 26 ≥ 50% (moderate bronzing); 3= 51 ≥ 75% (high bronzing); and 4= 76 ≥ 100% (severe bronzing) bronzed foliage. Blueberry bushes were rated by the same person each time who examined the plant foliage thoroughly for bronzing symptoms.

2.5. Mite Collections

The mite population was assessed during seven sampling events starting three days before the first miticide application (3-DBA, pre-treatment), three, seven, and 14 days after the first and the second application (post-treatment). Four bushes per plot were randomly chosen and sampled during the pre-treatment collection. To avoid repeated sampling, sampled bushes were tagged with color ribbons during each sampling event for differentiation. Fifteen leaves per blueberry bush were collected in 50-mL tubes and washed with 10-mL of 70% ethanol in the laboratory. Leaves were discarded and the ethanol containing the mites was checked repeatedly for adult and immature SRM under a dissecting microscope. Additionally, the presence or absence of predatory mites in the samples was recorded. A representative sample of adult pest and predatory mite specimens (~30 mites each) were slide-mounted for identification.

2.6. Statistical Analysis

Spearman’s Rank Correlation Coefficients (rs) were calculated to identify any relationships among the survey data collected. The numbers of SRM (adults and immatures) were analyzed by fitting a generalized linear mixed model (GLMM) using GLIMMIX and following a negative binomial distribution. Plant injury data were analyzed by fitting a linear mixed model (LMM). Averaged indexes per plot were compared among treatments and sampling events (pre-treatment and 14-DAA) using the MIXED procedure. Presence and absence data for predatory mites were fitted using a GLMM with a QUAD method following a negative binomial distribution. Event “1” was equivalent to the presence of predatory mites per sample. Both GLMMs and LMMs considered the fixed effect factors of treatment, sampling event, and their interaction, together with a random effect of Block. No transformation was used on any variable. Mean comparisons among treatments for GLMMs and LMMs were obtained by requesting LSMEANS from each procedure and the SLICE function for the effect of treatment when the GLMM was implemented. p-values less than 0.05 were considered significant. All models and analyses were fitted using SAS 9.4 (SAS Institute, Cary, NC).

3. Results

3.1. Grower Awareness of SRM

In total, 37 commercial growers participated in the survey. Responses showed that all participants grow a minimum of two SHB varieties and up to 10 varieties on the same farm (Table 1). Of the 26 varieties included in the responses, more than half of the growers (57%) grew ‘Emerald’, followed by ‘Jewel’ and ‘Meadowlark’ grown by 46% and 41% of the growers, respectively. None of the growers reported growing rabbiteye varieties. Only 27% (n=10) of the growers reported growing other small fruits in addition to the blueberries, 5% (n=2) reported growing fruiting vegetables, other 5% grew leafy greens, and 5% responded “other crops”.

Table 1.

Number of growers (n= 37) using each of the 26 varieties reported in the survey.

Table 1.

Number of growers (n= 37) using each of the 26 varieties reported in the survey.

| Variety |

No. of growers |

| Abundance |

1 |

| Arcadia |

12 |

| Avanti |

5 |

| Chickadee |

6 |

| Emerald |

21 |

| Endura |

3 |

| Farthing |

7 |

| Flicker |

3 |

| Indigocrips |

1 |

| Jewel |

17 |

| Jolies |

1 |

| Kestrel |

8 |

| Kirra |

2 |

| Meadowlark |

15 |

| Myra |

1 |

| Optimus |

5 |

| Primadonna |

5 |

| Rebel |

1 |

| San Joaquin |

1 |

| Scintilla |

3 |

| Snowchaser |

2 |

| Springhigh |

7 |

| Star |

1 |

| Sweetcrisp |

2 |

| Ventura |

2 |

| Winter Bell |

5 |

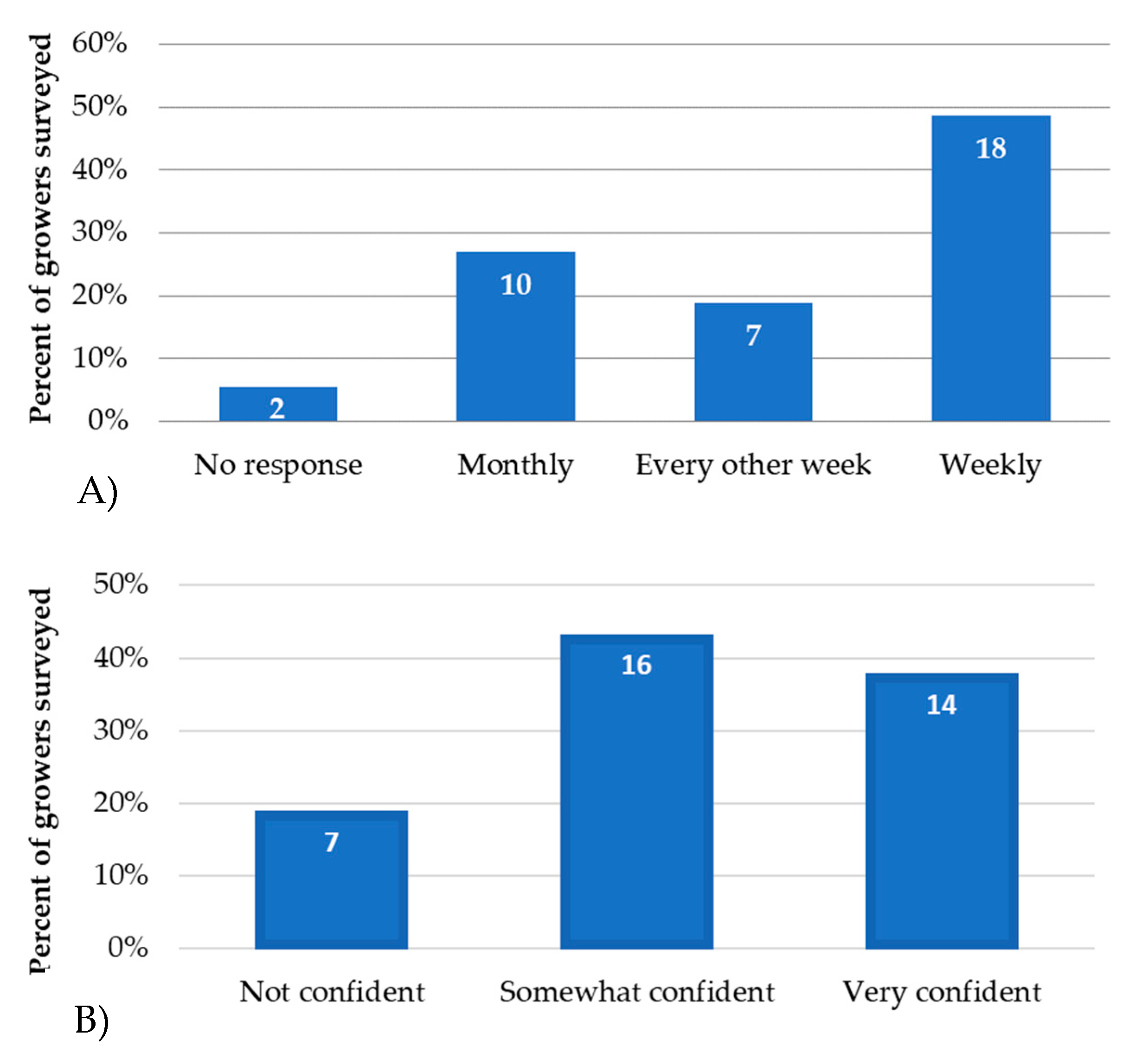

Most growers (49%) reported monitoring weekly for pests (

Figure 1, A), and 84% responded positively to considering mites in their monitoring practices. However, only 38% felt very confident about their ability to identify mite pests (

Figure 2, A). Similarly, only 48% of the growers responded to being very confident in identifying mite damage (

Figure 1, B). This question (question 6 in the appendix) was only responded to during the field day held in Citra; thus only 23 responses were collected. Due to technical difficulties, the 14 growers at the virtual meeting responded to eight questions instead of nine.

Mite damage was reported as seen in commercial blueberries by 68% of the surveyed growers of which eight responded to having seen it for the first time in 2020, two since 2019, five since 2018, and eight growers in the last 3-5 years. Only 5% did not recognize the damage shown in a picture incorporated in the survey (

Figure 2, B).

Regarding the use of pesticides, most growers (92%, n=34) reported using pesticides on their blueberries and responded with 20 different insecticides/miticides of which the miticide fenpyroximate (Portal) and the insecticide tolfenpyrad (Apta) were the most used (Table 2). However, most growers reported using 1-3 of these pesticides and only one reported using up to 5 of the 20 pesticides.

Table 2.

Number of growers (n= 37) using each of the 20 insecticides or miticides reported in the survey.

Table 2.

Number of growers (n= 37) using each of the 20 insecticides or miticides reported in the survey.

| Brand Name |

Active Ingredient (AI) |

Mode of Action (MoA) |

No. of Growers |

| Admire |

Imidacloprid |

4A |

2 |

| Assail |

Acetamiprid |

4A |

4 |

| Apta |

Tolfenpyrad |

21A |

5 |

| Avio |

Abamectin |

6 |

1 |

| Brigade |

Bifenthrin |

3A |

2 |

| Delegate |

Spinetoram |

5 |

4 |

| Entrust |

Spinosad |

5 |

1 |

| Exirel |

Cyantraniliprole |

28 |

1 |

| Gylon |

Chlorfenapyr |

13 |

1 |

| Malathion |

Malathion |

1B |

3 |

| Mustang |

Zeta-cypermethrin |

3A |

3 |

| Movento |

Spirotetramat |

23 |

2 |

| Neem |

Azadirachtin |

UN |

1 |

| Oil |

Oil |

UNE |

2 |

| Portal |

Fenpyroximate |

21A |

6 |

| Pyganic |

Pyrethrins |

3A |

1 |

| Sulfur |

Sulfur |

UN |

2 |

| Sulfur-CARB |

Sulfur + molasses |

UN |

1 |

| Sultan |

Cyflumetofen |

25A |

1 |

| Venerate |

Burkholderia spp. |

UNB |

1 |

Only 49% (n=18) reported being very confident in locating resources related to pest management and 51% (n=19) were somewhat confident in finding these types of resources. There was a significant correlation between the confidence in mite identification and the reports of mite damage by growers (rs= 0.45, p= 0.005, df= 36). There were no significant correlations between monitoring frequency and mite damage, number of blueberry cultivars and mite damage, confidence finding pest management resources and confidence in mite identification, monitoring frequency and pesticide use, mite damage and the use of fenpyroximate, and mite damage and the use of other miticides/insecticides (i.e., fenpyroximate, sulfur, sulfur + molasses, abamectin, bifenthrin, malathion, azadirachtin, and horticultural oils).

3.2. Southern Red Mite Counts

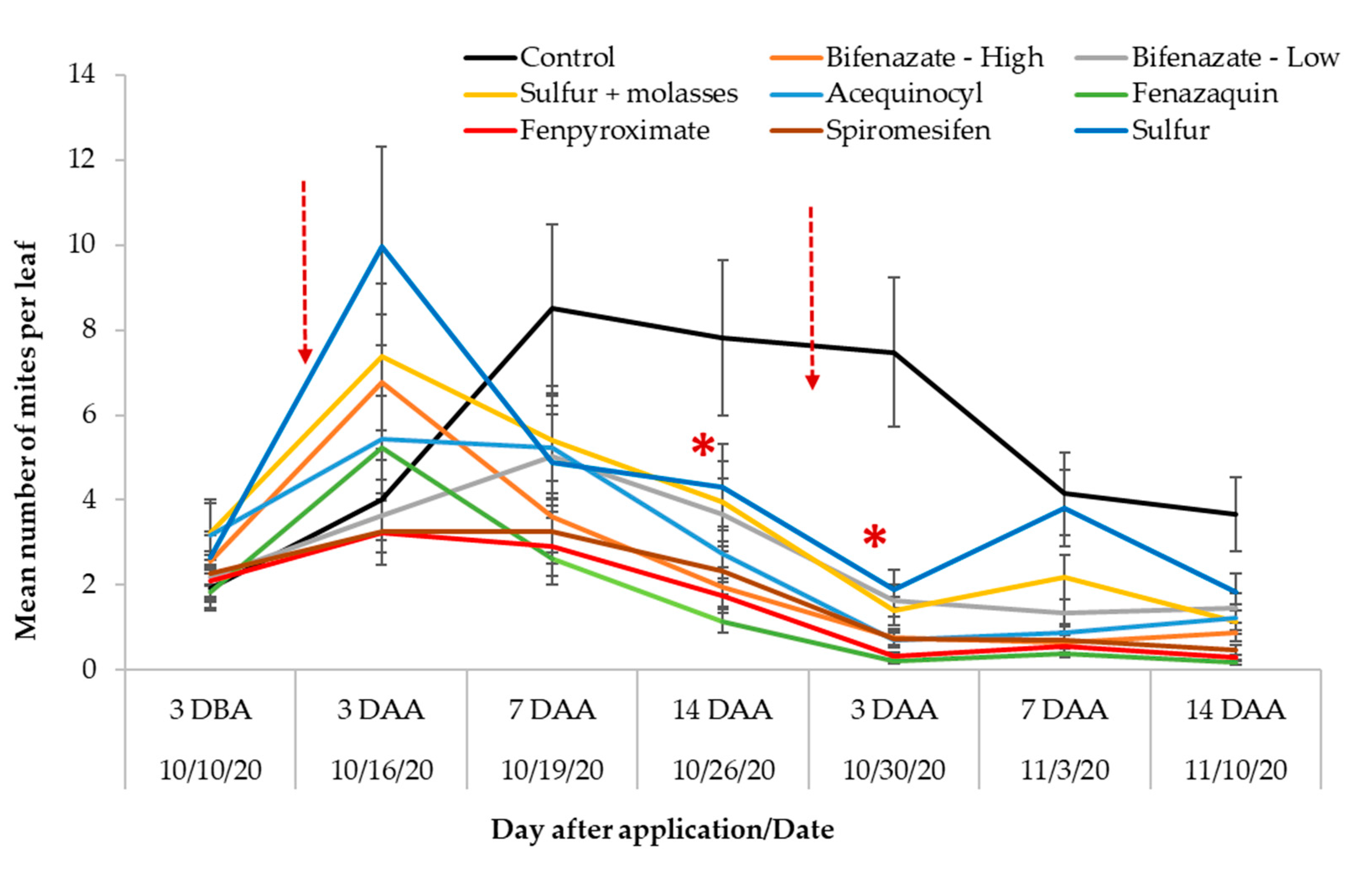

Infestation levels observed 3-DBA averaged 2.39 (±0.2) mites per leaf with no significant differences among treatments. There was a significant treatment-by-sampling event interaction for the number of SRM per leaf (F

48,

942= 3.61;

p <0.0001). The number of mites peaked three days after the first miticide application (3-DAA) in most treatments except for fenpyroximate and spiromesifen, which showed the lowest numbers, approximately two mites per leaf (

Figure 3). Contrastingly, bushes treated with sulfur and sulfur + molasses showed the highest numbers of SRM compared with the rest of the treatments at 3-DAA. Most miticide treatments showed significantly fewer mites compared to the control 14-DAA and 3 days after the second miticide application. The number of mites started to decrease seven days after the first miticide application (7-DAA) across treatments. indicating a significant suppressive effect in plants treated with acequinocyl and bifenazate (high rate), as well as fenazaquin. Fenpyroximate and spiromesin-treated plants maintained the lowest numbers of mites (1-3 mites per leaf) until the end of the experiment followed by bushes treated with fenazaquin. Contrastingly, the number of mites recorded in plants treated with sulfur and sulfur + molasses showed the highest numbers among the miticide treatments over time (

Figure 3).

The number of mites increased continuously in the blueberries in the control during most of the experiment, as expected. Fenpyroximate, fenazaquin, spiromesifen, and bifenazate (high rate) treated bushes showed significantly fewer mites compared to the control 7-DAA after the first miticide application. The number of SRM in all miticide treatments differed significantly from the control during the following two weeks, 14 days after the first application, and three days after the second application (

Figure 3).

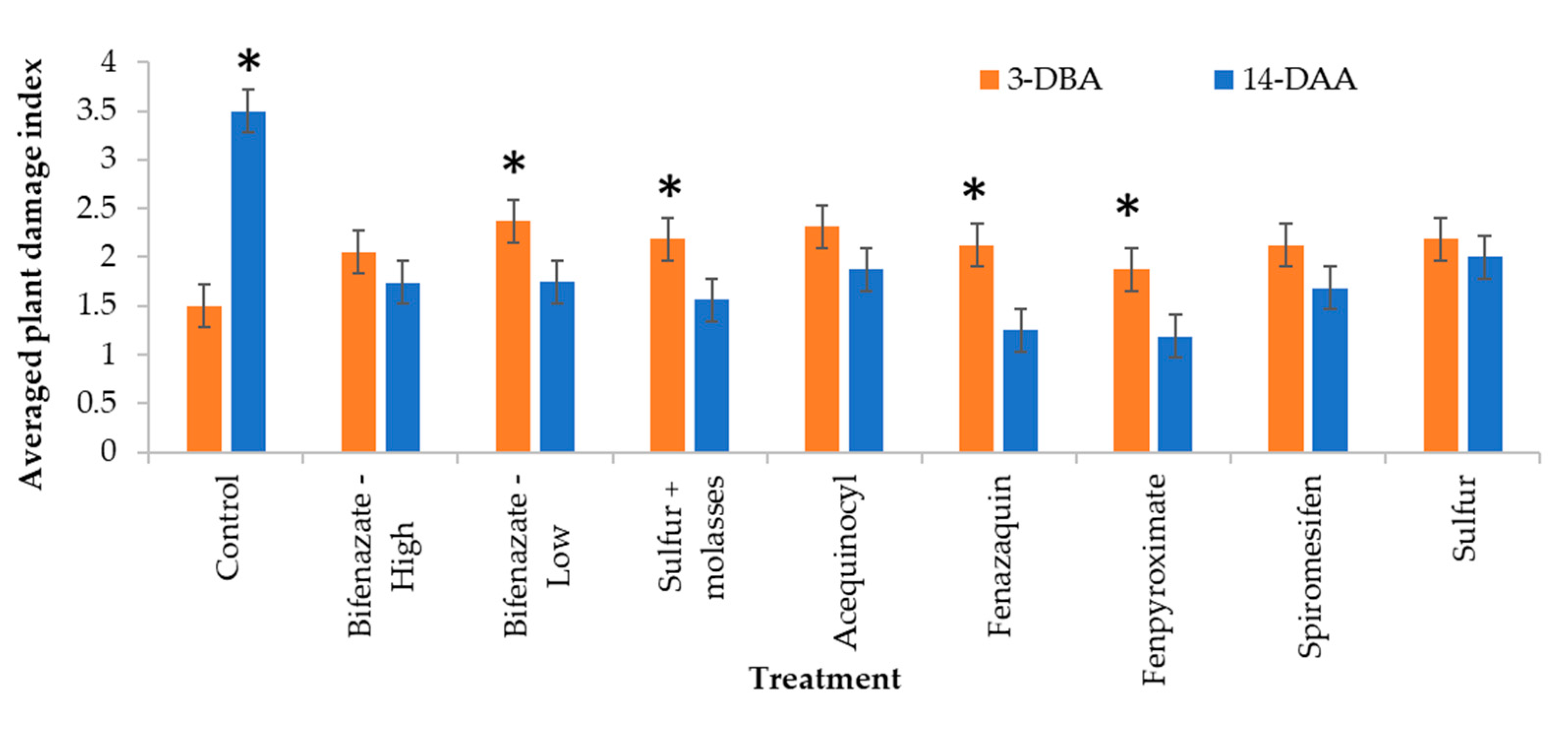

3.3. Plant Damage Caused by SRM

Plant damage ratings recorded pre-treatment (3-DBA) were not significantly different among treatments. Most blueberry plants showed moderate pre-treatment damage with an average index above two, except for plants in the control and fenpyroximate treatment with an average index below two (

Figure 4).

There was a significant treatment-by-sampling event interaction (pre-treatment and 14-DAA) for the averaged plant damage index (F

8,267= 8.47;

p <0.0001,

Figure 4). As expected, the percentage of bronzed foliage increased significantly in the control plants from ratings equivalent to 25% of bronzed foliage recorded at the pre-treatment up to indexes indicating high to severe (50-75%) bronzing symptoms at 14-DAA (

Figure 4).

Most miticide treatments showed a significant reduction of blueberry bronzing symptoms at 14-DAA. Blueberries treated with fenazaquin and fenpyroximate showed a 0.9- and a 0.7-fold reduction in the average index, respectively, indicating a recovery from moderate bronzing closer to low bronzing symptoms (

Figure 4). Plants treated with bifenazate (low rate) and sulfur+molasses also showed significant recovery symptoms on a smaller scale. There were no significant differences in bronzing symptoms recorded before and after miticide applications in the remaining treatments (

Figure 4).

3.4. Predatory Mite Counts

Two species of predatory mites were identified in the blueberry plantings,

Neoseiulus ilicis, a species native to Florida, and

Amblyseius sp. (Acari: Phytoseiidae). The number of plant samples containing predatory mites differed significantly over time (F

6,

990= 16.02;

p <0.0001,

Figure 5). The highest numbers were observed three days after the second miticide application with approximately 50% of the samples showing predators, indicating that predatory mites were able to survive or recolonize the plants after the miticide applications. We continued to find them in 40% and 30% of the samples in the following two weeks, respectively (

Figure 5).

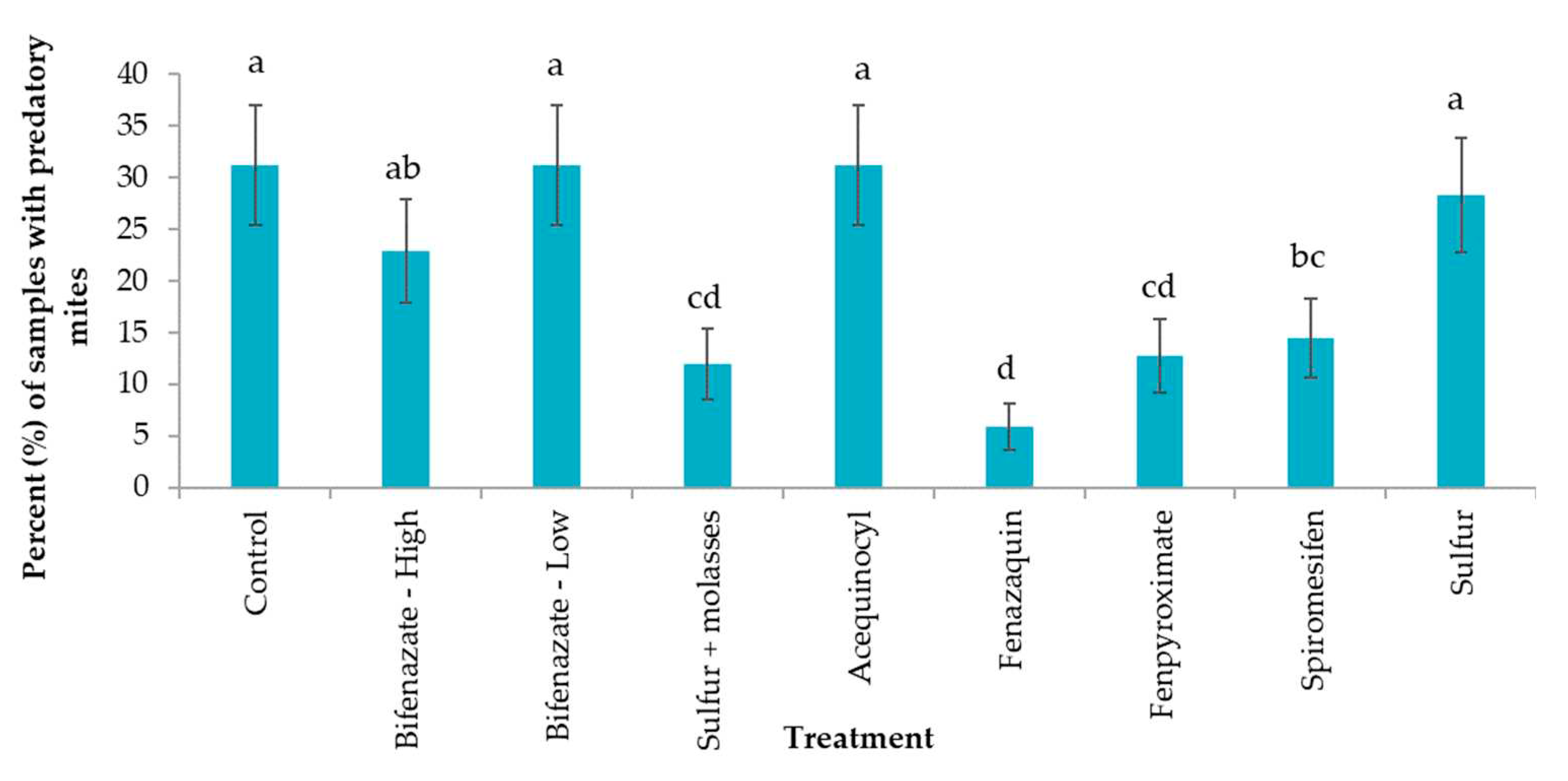

The percent of plant samples including predatory mites differed significantly among treatments (F

8,

990= 6.23;

p <0.0001). As expected, a good percentage of samples with predatory mites were collected from the control (up to 37% of samples), followed by samples collected from bifenazate- (low rate), acequinocyl-, and sulfur-treated plants. Contrastingly, plants treated with fenazaquin showed the lowest number of samples with predatory mites, followed by fenpyroximate and sulfur + molasses treatments (

Figure 6).

4. Discussion

Assessments to estimate blueberry growers’ level of awareness regarding SRM infestations and damage symptoms are vital to assist blueberry stakeholders and the grower community with pest management decisions, tools, and educational materials. Therefore, we designed a survey to better understand the pest management practices used by commercial blueberry growers in Florida. The survey demonstrated high levels of awareness regarding the presence of this emerging mite pest in Florida’s blueberry plantings, and most growers stated they considered mites in their monitoring practices. Similarly, the survey highlighted growers feel confident in identifying mites although less confident in recognizing the bronzing symptoms caused by mite feeding. Despite this, we were able to confirm that growers with higher confidence in identifying mite pests were also the growers that had a significantly higher ability to identify and report mite damage in their blueberry plantings, as expected (rs = 0.454, p = 0.004). Additionally, some growers detected bronzing symptoms caused by SRMs as far back as 2015; however, started noticing severe symptoms in 2019 and 2020. These responses are consistent with previous reports received at the Small Fruit and Vegetable IPM Lab regarding severe mite infestations in North-Central Florida and Georgia blueberry plantings with up to 100 acres severely bronzed and stunted (Lopez and Liburd, 2020).

One of the integrated pest management (IPM) tactics that are recommended to implement in any IPM program is to schedule pesticide applications based on economic thresholds (if any) or infestation data collected during monitoring events (Chen et al., 2019; Nyoike and Liburd, 2013; Liburd et al., 2007). Nonetheless, many fruit and vegetable growers prefer to schedule prophylactic or weekly insecticide/miticide sprays to protect their plantings. In the case of blueberries in Florida, insecticides are applied to 84% of the planted hectares in the state (Chen et al., 2019; Evans and Ballen, 2017). This is particularly common in blueberry plantings after the emergence of SWD. This seems to be common practice for most blueberry growers surveyed since the frequency of monitoring for pests (i.e., weekly, every other week, and monthly) was not significantly related to the growers’ responses to the use of pesticides. However, the use of miticides on a weekly schedule without knowledge of the levels of infestation can cause rapid miticide resistance development and over time contribute to the establishment of SRM as a key pest in SHB (Chen et al., 2019).

The most commonly grown SHB varieties identified in the survey were ‘Emerald’ and ‘Jewel’. These varieties are considered the backbone of the Florida blueberry industry (Williamson et al, 2019a, 2019b). These high-yielding cultivars should be frequently monitored for SRM presence and bronzing symptoms. Because the feeding damage caused by SRM can directly affect photosynthesis, it can also indirectly affect flowering and yield if infestations are left unchecked (Manners, 2019; Toledo et al., 2018). The bronzing symptoms may affect the early production of berries; however, cultivars that leaf well such as ‘Jewel’ may have the potential to recover from SRM damage. To our knowledge, there are no studies indicating any cultivar susceptibility to SRM infestations and the grower survey demonstrated that the diversity of blueberry varieties in the same farm was not significantly related to the mite damage encountered by the growers surveyed. But SRM has been detected in blueberry leaf samples of ‘Farthing’, ‘Avanti’, ‘Arcadia’, ‘Meadowlark’, and ‘KeyCrisp’ sent to our laboratory facilities in Gainesville, FL in 2019 and 2020, and varietal preference may be identified in future studies. Oligonychus ilicis can cause economic damage in blueberry production if infestations are not detected and suppressed early in the season (Toledo et al., 2018). Despite causing indirect damage by feeding on the foliage of its hosts, large populations can significantly reduce photosynthesis (>50% reduction in coffee plantings), resulting in stunted plants with roughened shoots and low potential to produce flower buds (Lopez and Liburd, 2020; Manners, 2019; Toledo et al., 2018; Denmark et al., 2006).

The infestation patterns of SRM in blueberry plantings in Florida and Georgia follow the pattern of secondary pests’ outbreaks and we believe broad spectrum insecticides used against key pests such as spotted-wing drosophila (D. suzukii, SWD), chilli thrips (S. dorsalis), and flea beetles (Colaspis pseudofavosa Riley, Coleoptera: Chrysomelidae) may be the primary driver for this phenomenon. For instance, SRM has been reported in various blueberry plantings since 2015 but was not reported in the literature until 2020, approximately seven years after SWD became a problem in Florida (Rodriguez-Saona et al., 2019). We hypothesize that SRM moved from one of their primary hosts grown in the southeast (ornamental plants such as boxwood, camellias, or hollies) to blueberries because their natural enemies in blueberry planting were destroyed due to the overuse of broad-spectrum insecticides. Pyrethroids are heavily used in SHB during harvest for control of SWD and post-harvest for the control of the blueberry leaf beetle (C. pseudofavosa) and chilli thrips (S. dorsalis) (USDA-NASS, 2022; Rodriguez-Saona et al., 2019; Roubos and Liburd, 2010; Arevalo et al, 2007). The non-target effects of these broad-spectrum insecticides reduce the populations of natural enemies that keep secondary pests such as SRM from increasing in numbers by killing them or limiting recolonization from natural enemies that escaped from sprays [5-16]. The removal of competitors creates an opportunity for secondary pests such as SRM to infest blueberry plantings, which can be exacerbated by the ability of O. ilicis to increase in abundance after exposure to low concentrations of pyrethroids in the field. This phenomenon is known as hormesis or the stimulatory effect associated with low doses of insecticides or miticides (Cordeiro et al., 2013). For instance, pyrethroids such as bifenthrin are commonly known for triggering this physiological phenomenon in many spider mite populations infesting fruit crops and it is particularly concerning that bifenthrin is reported as one of the top insecticides used by Florida blueberry growers (USDA-NASS, 2022). Currently, infestations with SRM are considered outbreaks (i.e., short-term consequences of pesticide use); however, SRM could soon become a new key established pest in SHB if blueberry pest management programs do not include alternative miticide options and alternative mite management tactics.

In this study, fenpyroximate showed the best performance for control of SRM in the field trials and it was also the only true miticide (kills only mites and not insects) reportedly used by most growers in the survey. This miticide was effective against this pest in our 2019 trials (Lopez and Liburd, 2020) and was registered for use in SHB in 2020. Fenpyroximate has become a popular and effective tool against mite infestations in many vegetable and fruit cropping systems and it was confirmed during the grower survey. Despite that, it is always recommended that growers have a variety of insecticidal and miticidal tools to rotate as part of their resistance management plans. However, the diversity of miticides or miticides/insecticides that growers have in their toolboxes was low based on the growers’ survey responses.

Acequinocyl and fenazaquin were also effective at reducing SRM populations in our trials in 2019 and 2020 after the second application. It is important to highlight that only one application of fenazaquin per year is permitted in blueberries. Thus, the recommended rate was split in half to conduct two applications during the trials. The reduction in SRM after fenazaquin and acequinocyl applications at 14-DAA may be explained by their residual effect that lasts for 3-4 four weeks after application. Bushes treated with fenpyroximate and fenazaquin showed signs of recovery at the end of the experiment with a reduction in bronzing symptoms, but this was not observed in bushes treated with acequinocyl.

Bifenazate (high rate) demonstrated potential to suppress SRM; however, it is not registered for use in SHB yet. Similarly, spiromesifen demonstrated good efficacy against SRM. Sulfur + molasses suppressed numbers of this pest only after the second application and bushes also showed signs of recovery by overgrowing bronzing symptoms. This was rather a surprising finding given that Sulfur-CARB (brand name) is formulated as a soil amendment used to increase soil oxidation, adjust pH, and stimulate microorganism populations, which can also be applied over the foliage (Sulfur-CARB label). We wanted to evaluate this product since it was brought to our attention by some growers using it in their plantings against the SRM. This was not confirmed in the survey since only one grower included this product in their list of pesticides. Despite this finding, we strongly recommend only using miticides registered as effective against spider mites (Tetranychidae) or SRM specifically. Despite the popularity of sulfur (Cosavet) to suppress some mite pests, it was not effective at suppressing SRM during our trials.

Good-performing miticides are now available for use against SRM in SHB, but these tools are not yet being used by most blueberry growers in Florida. Blueberry pest management programs need to be informed about these tools to improve SRM suppression, pesticide rotations, and avoid reliance on broad-spectrum insecticides/miticides. The diversity of plant protection products responded to by the growers demonstrated the potential to develop good rotation programs if more miticides options are included. Nevertheless, only two miticides (bifenthrin and fenpyroximate) were included as used in the blueberry plantings. It is highly recommended to diversify the miticide options to avoid the development of miticide resistance and to enhance the natural enemy populations that may be contributing to the suppression of SRM.

In response to the needs identified we have published various educational materials available to growers between 2020 and 2022 including extension publications and presentations. These address basic information to identify SRMs, their injury to blueberry foliage, and miticide products that should be included in the insecticide/miticide rotation plan of growers to mitigate mite infestations. Additionally, the 2020 miticide trials shown in this study were based on the miticide trials started in 2019 (Lopez and Liburd et al., 2020) with the addition of more pest management products suggested by growers during the blueberry meetings and to demonstrate their potential to suppress SRM populations.

This research is the first report of predatory mites naturally occurring in SHB in Florida. We believe that the lack of broad-spectrum insecticide applications before and during the trials allowed predatory mites to migrate to the SRM-infested bushes. We also observed predatory mites feeding on the SRM in field observations. The significant percentage of samples including predatory mites overlapped with the time when the lowest numbers of SRMs were recorded. Thus, it appeared that the naturally occurring predators may have contributed to the suppressive effects of some miticides. Our hypothesis is based on the life tables of SRM and the phytoseiid mite Amblyseius herbicolis indicating an increased population growth for the predatory mites when feeding on SRM in laboratory conditions (Cordeiro et al., 2013). It is not surprinsing to record predatory mites attracted to the SRM populations in the blueberry bushes during our study since several natural enemies have been found in association with O. ilicis in other crops such as coffee plantings in Brazil (Toledo et al. 2018). Some of these were reported as phytoseiids from the Amblyseius genera like the one species identified during our trials in Florida’s SHBs. Finally, further investigations are needed to further clarify the effects of naturally occurring predatory mites on SRM populations in SHB and their potential to be integrated with miticide and insecticide rotation programs.

5. Conclusions

The spread of invasive and secondary pests requires blueberry pest management programs to adapt. The current study identifies grower awareness of SRM as an emerging pest and provided a list of miticidal tools that effectively suppressed SRM and were recently registered for use in SHB.

This research documented for the first time two species of phytoseiid mites associated with SRM populations in SHB plantings in Florida. Populations of these naturally occurring predators could be enhanced by reducing the applications of broad-spectrum products against key insect pests. Additionally, selective miticides could be used to suppress SRM outbreaks and at the same time maintain natural enemy populations as shown in this study.

Finally, establishing action thresholds is vital to designing management programs for SRM, in addition to evaluating cultivar preferences or susceptibility to SRM infestations. Likewise, continuing educational programs highlighting these tools is vital to spread the word about these IPM tactics and further grower assessments are important to identify any changes in growers’ approaches in the future.

Acknowledgments

We thank Sam Bolton for assistance with the identification of the southern red mites, a commercial grower for their collaboration and providing access to their blueberry plantings, and the entire Fruit and Vegetable IPM Lab staff for assistance in spraying and collecting leaf samples. We thank the various agriculture and chemical industries for providing the samples for us to evaluate.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Arevalo, H.A.; Liburd, O.E. Horizontal and vertical distribution of flower thrips in southern highbush and rabbiteye blueberry fields, with notes on a new sampling method for thrips inside the flowers. J. Econ. Entomol. 2007, 100, 1622–1632. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Borisova, T.; Conlan, E.; Smith, E.; Olmstead, M.; Williamson, J. Blueberry frost protection practices in Florida and Georgia. Food Resour. Econ. Dep. UF/IFAS Ext. 2018, 1–7.

- Buck, B. Blueberry production in Florida. Specialty Crop Industry 2022. Available online: https://specialtycropindustry.com/blueberry-production-in-florida/.

- Chen, Q.; Liang, X.; Wu, C.; Gao, J.; Chena, Q.; Zhanga, Z. Density threshold-based acaricide application for the two-spotted spider mite Tetranychus urticae on cassava: from laboratory to the field. Pest Manag Sci 2019, 75, 2634–2641. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cordeiro, E.M.G.; de Moura, I.L.T.; Fadini, M.A.M.; Guedes, R.N.C. Beyond selectivity: Are behavioral avoidance and hormesis likely causes of pyrethroid-induced outbreaks of the southern red mite Oligonychus ilicis? Chemosphere 2013, 93, 1111–1116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cromroy, H.L., Kuitert L.C. Blueberry Bud Mite, Acalitus vaccinii (Keifer) (Arachnida: Acari: Eriophyidae). Entomol. Nematol. Dep., UF/IFAS Ext. 2017, EENY-186.

- Denmark, H.A.; Welbourn, W.C.; Fasulo, T.R. Southern red mite, Oligonychus ilicis (McGregor) (Arachnida: Acari: Tetranychidae); Florida Department of Agriculture and Consumer Services, Division of Plant Industry and Department of Entomology and Nematology, University of Florida: Gainesville, FL, USA, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Evans, E.A.; Ballen, F.H. An overview of US blueberry production, trade, and consumption, with special reference to Florida. Food Resour. Econ. Dep. UF/IFAS Ext. 2017, 1–8.

- Fahl, J.I.; Queiroz-Voltan, R.B.; Carelli, M.L.C.; Schiavinato, M.A.; Prado, A.K.S.; Souza, J.C. Alterations in leaf anatomy and physiology caused by the red mite (Oligonychus ilicis) in plants of Coffea arabica. Braz. J. Plant Physiol. 2007, 1, 61–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Franco, R.A.; Reis, P.R.; Zacarias, M.S.; Altoe, B.F.; Neto, M.P. Population dynamics of Oligonychus ilicis (McGregor, 1917) (Acari: Tetranychidae) in coffee plants and of their associated phytoseiids. Coffee Sci. 2008, 3, 38–46. [Google Scholar]

- Lang, G.A.; Parrie, E.J. Pollen Viability and Vigor in Hybrid Southern Highbush Blueberries (Vaccinium corymbosum L. ×spp.). HortScience 1992, 27, 425–427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liburd, O.E.; White, J.C.; Rhodes, E.M.; Browdy, A.A. The residual and direct effects of reduced-risk and conventional miticides on twospotted spider mites, Tetranychus urticae Koch (Acari: Tetranychidae) and predatory mites (Acari: Phytoseiidae). Fla. Entomol. 2007, 90, 249–257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lopez, L.; Liburd, O.E. Injury to southern highbush blueberries by southern red mites and management using various miticides. Insects 2020, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Manners, A. Contingency plan for southern red mite, Oligonychus ilicis. Queensland Department of Agriculture and Fisheries Nursery & Garden Industry Australia 2019. Available online: https://www.planthealthaustralia.com.au/wp-content/uploads/2019/12/Southern-red-mite-CP.pdf (accessed on 2 February 2020).

- Nyoike, T.W.; Liburd, O.E. Effect of Tetranychus urticae (Acari: Tetranychidae), on marketable yields of field-grown strawberries in north-central Florida. J. Econ. Entomol. 2013, 106, 1757–1766. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rodriguez-Saona, C.; Vincent, C.; Isaacs, R. Blueberry IPM: Past successes and future challenges. Annu. Rev. Entomol. 2019, 64, 95–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Roubos, C.R.; Liburd, O.E. Evaluation of emergence traps for monitoring blueberry gall midge (Diptera: Cecidomyiidae) adults and within field distribution of midge infestation. J. Econ. Entomol. 2010, 103, 1258–1267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- USDA-National Agricultural Statistics Service Florida Field Office. Vegetables, Melons, and Berries. 2022 Annual Statistical Bulletin 2022, E1-E7. Available online: https://www.nass.usda.gov/Statistics_by_State/Florida/Publications/Annual_Statistical_Bulletin/2022/E1thru8Veg-2022c.pdf.

- Weibelzahl, E., Liburd, O.E. Blueberry Bud Mite, Acalitus vaccini (Keifer) on Southern Highbush Blueberry in Florida. Entomol. Nematol. Dep., UF/IFAS Ext.2017, ENY-858.

- Williamson, J.G.; Harmon, P.F.; Liburd, O.E.; Dittmar, P. 2019 Florida blueberry integrated pest management guide. Hortic. Sci. Dep. UF/IFAS Ext. 2019a, 1–38.

- Williamson, J.G., Phillips, D.A., Lyrene, P.M., Munoz, P.R. Southern Highbush Blueberry Cultivars from the University of Florida. Hort. Sci. Department, UF/IFAS Ext. 2019b, HS1245.

- Toledo, M.A.; Rebelles, Reis, P.; Rodrigues, G.; Marcelo, L.; Cirillo, Â. Biological Control of Southern Red Mite, Oligonychus ilicis (Acari: Tetranychidae), in Coffee Plants. Adv. Entomol. 2018, 6, 74–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Figure 1.

The percentage of growers and the number of growers’ responses are shown on the y-axis and within each bar, respectively, for A) Frequency of monitoring for pests either using traps, in situ counts, or scout services in blueberry plantings. B) Level of grower confidence in identifying mite pests on their farms.

Figure 1.

The percentage of growers and the number of growers’ responses are shown on the y-axis and within each bar, respectively, for A) Frequency of monitoring for pests either using traps, in situ counts, or scout services in blueberry plantings. B) Level of grower confidence in identifying mite pests on their farms.

Figure 2.

The percentage of growers and the number of growers’ responses are shown on the y-axis and within each bar, respectively, for A) Level of confidence in identifying mite damage. B) Mite damage reported by blueberry growers.

Figure 2.

The percentage of growers and the number of growers’ responses are shown on the y-axis and within each bar, respectively, for A) Level of confidence in identifying mite damage. B) Mite damage reported by blueberry growers.

Figure 3.

Mean (± SE) number of southern red mites (SRM) per leaf recorded three days before miticide application (DBA), three, seven, and fourteen days after miticide applications (DAA). Two miticide applications were conducted 15 days apart (on 10/13/2020 and 10/27/2020) represented here by the dotted arrows. Asterisks represent significant differences for mite numbers per leaf recorded on treatments over time (Treatment*Sampling-event interaction, F48,942= 3.61; p <0.0001) compared with the control.

Figure 3.

Mean (± SE) number of southern red mites (SRM) per leaf recorded three days before miticide application (DBA), three, seven, and fourteen days after miticide applications (DAA). Two miticide applications were conducted 15 days apart (on 10/13/2020 and 10/27/2020) represented here by the dotted arrows. Asterisks represent significant differences for mite numbers per leaf recorded on treatments over time (Treatment*Sampling-event interaction, F48,942= 3.61; p <0.0001) compared with the control.

Figure 4.

Bronzing of blueberry foliage caused by southern red mite (SRM) feeding rated pre-treatment three days before the first miticide application (3-DBA, on 10/10/2020) and 14 days after the second and final miticide application (14-DAA, on 10/27/2020) based on an arbitrary plant damage index (0= no bronzing; 1= 1 ≥ 25% (low bronzing); 2= 26 ≥ 50% (moderate bronzing); 3= 51 ≥ 75% (high bronzing); and 4= 76 ≥ 100% (severe bronzing) bronzed foliage). Asterisks highlight a bar with a significantly higher average (Treatment*Sampling event interaction, F8,267= 8.47; p <0.0001).

Figure 4.

Bronzing of blueberry foliage caused by southern red mite (SRM) feeding rated pre-treatment three days before the first miticide application (3-DBA, on 10/10/2020) and 14 days after the second and final miticide application (14-DAA, on 10/27/2020) based on an arbitrary plant damage index (0= no bronzing; 1= 1 ≥ 25% (low bronzing); 2= 26 ≥ 50% (moderate bronzing); 3= 51 ≥ 75% (high bronzing); and 4= 76 ≥ 100% (severe bronzing) bronzed foliage). Asterisks highlight a bar with a significantly higher average (Treatment*Sampling event interaction, F8,267= 8.47; p <0.0001).

Figure 5.

Percent (± SE) of samples with the presence of predatory mites recorded three days before miticide application (DBA), three, seven, and fourteen days after miticide applications (DAA). Two miticide applications were conducted 15 days apart (on 10/13/2020 and 10/27/2020) represented here by the dotted arrows. Different letters across bars indicate significant differences (sampling event main effects, F6,990= 16.02; p <0.0001).

Figure 5.

Percent (± SE) of samples with the presence of predatory mites recorded three days before miticide application (DBA), three, seven, and fourteen days after miticide applications (DAA). Two miticide applications were conducted 15 days apart (on 10/13/2020 and 10/27/2020) represented here by the dotted arrows. Different letters across bars indicate significant differences (sampling event main effects, F6,990= 16.02; p <0.0001).

Figure 6.

Percent (± SE) of samples with the presence of predatory mites recorded three days before miticide application (DBA), three, seven, and fourteen days after miticide applications (DAA). Two miticide applications were conducted 15 days apart (on 10/13/2020 and 10/27/2020) represented here by the dotted arrows. Different letters across bars indicate significant differences (treatment main effects, F8,990= 6.23; p <0.0001).

Figure 6.

Percent (± SE) of samples with the presence of predatory mites recorded three days before miticide application (DBA), three, seven, and fourteen days after miticide applications (DAA). Two miticide applications were conducted 15 days apart (on 10/13/2020 and 10/27/2020) represented here by the dotted arrows. Different letters across bars indicate significant differences (treatment main effects, F8,990= 6.23; p <0.0001).

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).