1. Introduction

P2X

7 receptor (P2X

7R) is an ATP-gated ion channel belonging to the purinergic P2X family. It is highly expressed by cells of the innate immune system, especially macrophages [

1], dendritic cells [

2], mast cells [

3], and microglia [

4], where it promotes inflammasome formation and release of inflammatory cytokines [

5,

6,

7]. P2X

7R is also present in adaptive immune cells (T cells), where it regulates cell development and function [

8], and in many other cell types [

9] including nervous system cells [

10,

11], epithelial and endothelial cells [

12,

13], bone cells [

14], fibroblasts [

15] and smooth muscle cells [

16], as well as in tumor cells where its expression often correlates with worse diagnosis [

17,

18].

Among P2XR family, P2X

7R exhibits peculiar features including low affinity for ATP, lack of desensitization and unique structural domains, i.e. a “C-cysteine anchor” intra-cytoplasmic motif and a long C-terminal cytoplasmic domain that contains several protein–protein interaction motifs [

19,

20]. The receptor also exhibits a characteristic dual gating state depending on extracellular ATP (eATP) concentration. At micromolar eATP concentration, P2X

7R opens a cation-selective channel that mediates cellular influx of Na

+ and Ca

2+ ions and an efflux of K

+ [

21]; at higher eATP concentration (above 100 mM) and upon prolonged exposure, the receptor functions as a non-selective membrane pore permeable to hydrophilic molecules [

21], generally leading to cytotoxicity and apoptotic cell death [

22]. Channel opening increases cell proliferation and survival [

23,

24] whereas large pore opening induces activation of inflammasome [

25], a cytoplasmic multiprotein complex that in response to pathogens/cell damage triggers cytokine release and pyroptosis, a lytic form of programmed cell death [

26].

The inflammasome consists of a sensor protein (e.g. NLR family CARD domain containing 4 (NLRC4), NLR Family Pyrin Domain Containing 1 (NLRP1), NLR Family Pyrin Domain Containing 3 (NLRP3) that is activated by ATP, absent-in-melanoma 2 (AIM2) and pyrin), an inflammatory caspase, and in some cases an adaptor protein, like ASC (apoptosis-associated speck-like protein containing a CARD) [

27]. Once assembled and activated in response to ATP, the NLRP3 inflammasome triggers pro-caspase-1 cleavage, which generates active caspase-1 that, in turn, drives the enzymatic activation of the leaderless cytokines Interleukin (IL)-1β and IL-18, initiating an inflammatory response [

28,

29].

In addition to ATP, P2X

7R cation channel can be opened by non-ATP nucleotides, such as NAD

+ (nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide). This ATP-independent pathway consists of receptor ADP-ribosylation by ADP-ribosyltransferases ART2.1 and ART2.2, which catalyze the transfer of ribose from NAD

+ to arginine 125 in the ectodomain of the P2X

7R close to the ATP binding site [

30]. P2X

7R opening by ADP-ribosylation enables Ca

2+ and Na

+ influx and K

+ efflux, phosphatidylserine externalization, membrane pore formation, mitochondrial membrane breakdown, and ultimately cell death [

31].

Interestingly, both ATP and NAD

+ concentrations are low (in the submicromolar range) in the extracellular space, due to the activities of the ectoenzymes CD39 and CD38 that degrade them, respectively [

8]. Therefore, P2X

7R activation occurs at inflammatory or damaged sites, as well as in the tumor microenvironment, where ATP and NAD

+ are released in substantial amounts [

31,

32].

One of the main consequences of P2X

7R activation is the formation of blebs at the cell surface and the release of extracellular vesicle (EVs) into the microenvironment. EVs are a heterogeneous group of cell-derived membranous structures which directly bud from the plasma membrane (microvesicles) or originate in the endocytic compartment as intraluminal vesicles (ILVs) which are released through the fusion of multivesicular bodies (MVBs) to the plasma membrane (exosomes) [

33]. Due to technical limitation in isolating and distinguishing EVs based on their biogenesis, the currently recognized nomenclature identifies EVs according to their physical properties and dimension, distinguishing medium-large/large EVs (>200 nm) and small EVs (< 200 nm) [

34]. Accordingly, here we use the terms large and small EVs to refer to the two main populations of EVs. EVs act as a carrier of bioactive molecules (proteins, lipids, genetic materials, and metabolites) and convey their bioactive cargoes between cells, playing a fundamental role in cell-to-cell communication in both physiological conditions and during inflammatory and degenerative diseases [

35,

36].

In the present review, we will first discuss the impact of P2X7R activation on EV release from the cell surface and the endocytic compartment. Then we summarize current knowledge about the role of P2X7R activation in the sorting of proteins into EVs, the secretion of inflammatory cytokines and the dissemination of misfolded proteins.

2. P2X7R activation and EV release

Among stimuli that promote EV release (cytokines, LPS, capsaicin, serotonin, Wnt3a, α-synuclein) [

37], eATP is the classical trigger that, through P2X

7R activation , massively increases the shedding of EVs from the plasma membrane of immune cells including dendritic cells [

38,

39], microglia [

40] and macrophages [

6,

41]. Of note, not only millimolar concentration of eATP but also ATP endogenously released by astrocytes could induce P2X

7R-dependent EV release in microglia-astrocyte co-culture [

40].

The first evidence implicating P2X

7R activation in the release of EVs dates back to 2001 when MacKenzie and colleagues showed that within the first few minutes of P2X

7R activation bleb formation occurs at the surface of monocytes and large EVs with externalized phosphatidylserine (PS) are released into the extracellular space as a result of bleb detachment from the membrane [

42]. Notably, bleb formation and externalization of PS, a typical marker of apoptosis, are reversible processes under brief P2X

7R stimulation, dissociating ATP-induced bleb formation and EV release from apoptosis [

42].

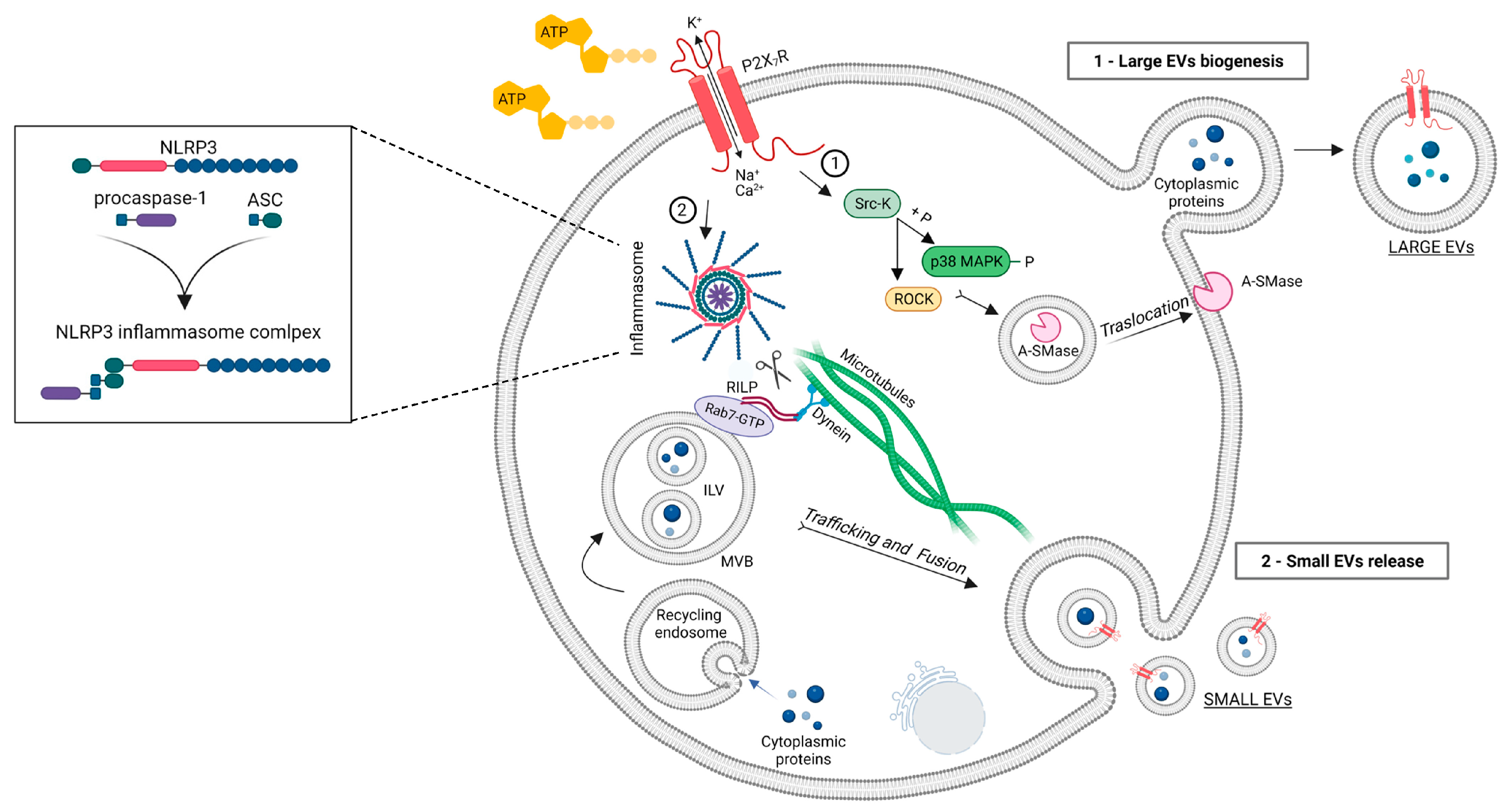

Subsequent studies clarified the mechanism by which P2X

7R activation drives large EV biogenesis. The pathway involves recruitment of a Src kinase at the C-terminus of the receptor, activation of ROCK and p38 MAP kinase, reorganization of cytoskeletal elements and translocation to the plasma membrane of acid sphingomyelinase (A-SMase) [

43,

44,

45,

46] (

Figure 1). This enzyme hydrolyzes sphingomyelin, a phospholipid abundant in the outer leaflet of the plasma membrane, to ceramide, facilitating formation of plasma membrane blebs and large EV shedding from microglia and astrocytes [

43]. The key role of A-SMase in EV release was indicated by genetic inactivation and pharmacological inhibition of the A-SMase. Both approaches strongly abolished EV release from LPS-primed microglia and astrocytes [

43] and alveolar macrophages [

7] (see also below).

In vivo validation of the role of P2X

7R and A-SMase in EV release was suggested by immunohistochemical quantification of EV-like particles immunoreactive for the P2X

7R in the cerebral cortex of rat administered intraperitoneally with the P2X

7R antagonist A804598 or the A-SMase inhibitor FTY720, immediately after traumatic brain injury (TBI), a condition inducing P2X

7R expression and EV release from microglia [

47]. Both drugs reduced the number of P2X

7R positive particles surrounding microglia, but the particles were not unequivocally identified as EVs [

47].

In addition to large EVs shed from the plasma membrane, P2X

7R activation promotes the release of small EVs generated in the endosomal compartment of innate immune cells [

48,

49,

50]. Interestingly, in human macrophages ATP-dependent small vesicles release was shown to be a consequence of NLRP3/ASC/procaspase-1 inflammasome assembling, as evidenced by suppression of small EVs secretion under genetic deletion of ASC or NLPR3 [

49]. These findings suggested that inflammasome activation may regulate the membrane trafficking pathways that control MVBs fusion to the plasma membrane. The involvement of NLRP3 inflammasome in small EV secretion was further indicated by a study showing that LPS/ATP-induced inflammasome and caspase-1 activation promotes loading of specific miRNAs into small EVs and their release via cleavage of the Rab-interacting lysosomal protein RILP in a human monocytic cell line. RILP is part of the complex that links the trafficking GTPase Rab7 to the dynein motor complex; cleaved RILP does not make the link to dynein complex and promotes the movement of MVBs toward the cell surface (

Figure 1). In addition, it induces selective miRNA cargo sorting via interaction with Hrs (hepatocyte growth factor–regulated tyrosine kinase substrate), a component of the ESCRT-0 complex, and the RNA-binding protein FMRP that acts as a chaperone to package specific AAUGC motif–containing miRNAs into ILV [

51]. Accordingly, inhibition of caspase-1 blocked small EV secretion from the monocytic cells activated with LPS/ATP [

51]. Further advances in the mechanism driving ATP-induced release of small EVs were made in 2022, when Ruan and colleagues identified Sepp1, Mcfd2, and Sdc1 as critical molecules for the release of CD63 positive small EVs from microglia using a genome-wide shRNA library screening [

52]. The identified molecules may represent interesting targets for inhibiting small EV release and limiting the pathogenic contribution of EVs and their inflammatory cargo to neuroinflammatory disorders.

3. Role of P2X7R-induced EVs in cytokine release and propagation of inflammation

Cytokines lacking the conventional secretory sequence do not follow the classical endoplasmic reticulum-to-Golgi pathway for secretion but are exported via membrane-enclosed vesicles [

53].

MacKenzie and colleagues showed that the pro-inflammatory cytokine IL-1β is packaged in EVs shed upon P2X

7R-mediated monocyte activation, providing the first evidence that P2X

7R-induced EV release represents an unconventional mechanism for secretion of a leaderless protein [

42]. In the following years, the presence of IL-1β was confirmed in EVs released from rat microglia and human dendritic cells [

39,

40] and it was clarified how IL-1β passes from the EVs lumen into the extracellular space. Specifically, it was observed that EVs contain the machinery necessary for IL-1β processing (they carry P2X

7R in their membranes and caspase-1 in their lumen) and that P2X

7R opening at the EV surface activates caspase-1-dependent IL-1β cleavage in the EVs like in the cells [

39,

40]. In addition, evidence was provided that IL-1β release may occur through the EV membrane as a consequence of P2X

7R-dependent pore opening [

5]. Collectively, these results indicated that large EVs released upon P2X

7R activation from immune cells carry IL-1β and mediate IL-1β secretion in a P2X

7R-dependent manner. Later evidence obtained in macrophages and dendritic cells showed that also small EVs carry inflammasome components, i.e. NLP3, caspase-1 and ASC, that are essential for IL-1β processing within EVs [

49,

50,

54]. These studies also showed that both small and large EVs released from mycobacterium-infected macrophages and dendritic cells upon P2X

7R activation are enriched in major histocompatibility complex class II (MHC-II) [

39,

55,

56], thus potentially contributing to rapid dissemination and presentation of foreign antigens as part of the immune response induced by local inflammation [

57,

58]. In line with the involvement of EVs in the immune response, large EVs released upon P2X

7R activation from LPS-treated microglia were reported to carry IL-1β transcript and to act as vehicles for the transfer of IL-1β mRNA between immune cells, participating in the propagation of inflammatory signals both

in vitro and

in vivo, upon EV injection into the mouse corpus callosum [

59].

Subsequent studies revealed that large EVs released upon P2X

7R activation mediate the release of other inflammatory cytokines, i.e. IL-18 and Tumor necrosis factor (TNF) [

6,

7]. Like IL-1β, IL-18 is a leaderless cytokine and its release from human blood-derived macrophages occurs in association with large EVs generated upon P2X

7R activation [

6]. Conversely, TNF is secreted by the classical endoplasmic reticulum- to-Golgi pathway in a mature soluble isoform of 17 kDa. Thus, the presence of TNF in EVs was quite unexpected. Notably, Soni and colleagues demonstrated that ATP stimulation alters the mechanism of TNF secretion from mouse bone-marrow derived macrophages, redirecting TNF release from classical to unconventional secretory pathway [

7]. Specifically, ATP inhibits the conventional secretion of soluble TNF and drives the packaging of the transmembrane pro-TNF isoform into large EVs [

7]. TNF carried by EVs was biologically more potent than soluble TNF at equal or even higher dose and mediated significant lung inflammation

in vivo [

7], revealing that ATP-dependent packaging into EVs uniquely protects enclosed TNF enhancing its biological activity. These findings were confirmed

in vivo upon intratracheal instillation of ATP and analysis of EV production and TNF quantification in the bronchoalveolar lavage fluid [

7].

To conclude, relevant cytokines are expressed in EVs at both mRNA and proteins levels and in both transmembrane/pro- and soluble/mature forms. The cytokines can be rapidly released from vesicles in the mature forms (IL-1β and IL-18) at sites of extracellular ATP accumulation via P2X

7R opening or be presented to recipient cells (pro-TNF), promoting acute inflammation. Given that packaging into EVs prevents degradation and dilution of the inflammatory mediators, cytokines-loaded EVs released by P2X

7R expressing cells can propagate long-distance inflammatory signals to recipient cells and tissues. Cytokines released as part of EVs upon P2X

7R activation are listed in

Table 1.

4. P2X7R activation influences the proteome of EVs

Distinct EV populations are released by cells in response to various stimuli that influence the cellular activation state [

37], with EV composition often mirroring those of donor cells. As already mentioned, P2X

7R activation influences the miRNA selectivity of small EV cargo loading through interactions with the RNA-binding protein FMR1 [

51]. Furthermore, a few studies identified proteins that are released as part of EVs via a P2X

7R-dependent mechanism (

Table 1). These molecules seem to share the ability to control the inflammatory response.

Takenouchi and coworkers showed that only under P2X

7R activation glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase (GAPDH), a key glycolytic enzyme and a leaderless cytoplasmic protein, is sorted in small and large EVs released by LPS-treated microglial cells [

60]. Once in the extracellular space, GAPDH might be involved in the regulation of neuroinflammation by favouring phosphorylation of p38 Map kinase in microglia [

60]. CD14 is another abundant protein cargo of EVs released upon P2X

7R activation from macrophage [

61]. P2X

7R-induced CD14 release in EVs ensures the maintenance of elevated concentration of circulating CD14 which, by acting as co-receptor for LPS, is fundamental to control infection and to increase survival during sepsis [

61].

Further studies associated P2X

7R activation to release of proteins modulating or amplifying the inflammatory response. Release of Interleukin-1 receptor antagonist (IL-Ra) occurs via a P2X

7R-dependent large EV-shedding mechanism in macrophages [

62]. Since IL-Ra functionally inhibits IL-1-dependent cellular activation, maintaining a balance between IL-1 and IL-1ra may be an important mechanism for regulating the overall inflammatory response [

63]. Conversely, the mature form of TNF converting enzyme (TACE), that is part of small EVs produced by LPS-primed macrophages under P2X

7R activation, by processing the membrane-bound TNF into a soluble cytokine may amplify the pro-inflammatory responses [

64]. Finally, other studies linked P2X

7R activation to an increased release of tissue factor (TF) containing large EVs from human dendritic cells and macrophages, producing an enhanced pro-thrombotic response [

38,

65].

To the best of our knowledge, only one label free proteomic study systematically explored how P2X

7R activation influences the protein composition of EVs. This work showed that the proteome composition of EVs (large and small) released from microglia under ATP activation is largely distinct from that of constitutively released EVs [

48]. Specifically, it revealed that EVs released under ATP stimulation contain an increased number of proteins involved in antigen processing and presentation which, along with inflammatory cytokines and MHC-II (see chapter above), can participate to the immune response. In addition, EVs released under P2X

7R activation show an increased number of autophagy-lysosomal proteins (i.e. Cathepsin D and C, Lamp1, Vcp and CD68), suggesting an enhancement of degradative pathways, and are enriched in proteins implicated in adhesion/extracellular matrix organization (Fibulin 1, Comp, Plasminogen and the Matricellular proteins thrombospondin 1 and 4, Vinculin and Fermt3), which likely account for stronger EV adhesion to astrocytic target cells compared to constitutive EVs. Interestingly, ATP also drives sorting in EVs of a set of proteins involved in energy metabolism (i.e. Gpi, Ldha, Mdh2, Tranketolase, Glutamate dehydrogenase 1, Acacb and others), which together with the glycolytic enzyme GAPDH identified by Takenouchi and colleagues, may influence the metabolism of receiving cells. Finally, a unique set of cytoskeletal proteins and proteins regulating the dynamics of actin filaments have been detected in EVs released upon P2X

7R activation, i.e. the capping actin protein Capzb, Cap1 and ARP2 actin related protein. These proteins, by controlling the organization of actin filaments present in a fraction of large EVs [

66], may favor changes in EV morphology and promote the capacity of a small fraction glial EVs to actively move at surface of target cells [

66,

67]. Interestingly, some of these cytoskeletal proteins interact with the C-terminus of the P2X

7R [

68], thus supporting a direct role for the receptor in the sorting of the protein cargo.

Further studies are necessary to define whether changes occurring in microglia-derived EVs under P2X7R activation may be common to EVs released by other cells following the receptor stimulation.

5. P2X7R activation and misfolded protein release in EVs: implications in neurodegeneration

Among the bioactive cargo of EVs released upon P2X

7R activation there are pathological misfolded proteins, included beta amyloid (Aβ) [

67,

69,

70], tau protein [

71,

72,

73] and α-synuclein [

74,

75] (for an extensive review see [

37];

Table 1).

By spreading throughout the brain in association with EVs, Aβ and tau protein contribute to progression of neurodegeneration in AD and tauopathies (reviewed in [

76]). Specifically, it has been demonstrated that EVs-associated tau released by microglia after ATP stimulation, but not an equal amount of free tau, are able to mediate efficient tau propagation in the mouse hippocampus [

71]. The pivotal involvement of P2X

7R in this process have been proven by recent findings showing that the administration of the orally applicable and CNS-penetrant P2X

7R selective antagonist GSK1482160, which inhibits EV secretion from microglia, blocks tau propagation and rescues memory impairment in the P301S mouse model of tauopathy [

73]. Furthermore, suppression of tau accumulation in the hippocampal region has been indicated in P301S mice lacking P2X

7R (P2X

7R

-/-:P301S mice) [

77]. Although for EV-mediated propagation of Aβ no direct proof of P2X

7R involvement by

in vivo inhibition/depletion is currently available, large EVs released upon ATP activation by Aβ-exposed microglia, and injected in the mouse brain parenchyma, were shown to cause amyloid-related impairment of synaptic plasticity and propagate the deficits to synaptically connected regions [

67]. Again, free oligomeric Aβ were not able to propagate synaptic alterations [

67]. Interestingly, P2X

7R expression and function have been found altered in both AD/tauopathies patients and mouse models, especially in microglia and astrocytes surrounding amyloid plaques, while its genetic or pharmacological inhibition ameliorated the pathology in mice, mitigating inflammation and improving cognitive defects [

78,

79,

80,

81]. For these reasons P2X

7R has been implicated in both Aβ and tau-mediated neurodegeneration [

79,

81] and recognized as a promising pharmacological target for AD [

82]. The involvement of the receptor in EV-mediated propagation of misfolded proteins strengthens its potential as therapeutic target for neurodegenerative diseases.

Small EVs released upon ATP stimulation can also transfer α-synuclein, a key molecule in Parkinson’s disease pathogenesis, from microglia to neurons, where they act as seeds to aggregate the native protein [

74]. Once injected in the striatum of healthy mice, microglial small EVs carrying α-synuclein, but not free α-synuclein, cause aggregation of the protein at the injection site and in anatomically connected regions, and loss of dopaminergic neurons in the nigrostriatal pathway associated to movement disorders months later [

75].

The presence of misfolded proteins in EVs released upon P2X

7R activation indicates that EV release represents a mechanism exploited by cells to get rid of toxic material, which cannot be degraded in the cells, an old hypothesis formulated many years ago when EVs were still considered cellular debris or culture artefacts, and currently supported by many findings [

67,

69,

74,

83].

Table 1.

Proteins released as part of EV cargo upon P2X7R activation and their phato/physiological impact.

Table 1.

Proteins released as part of EV cargo upon P2X7R activation and their phato/physiological impact.

| EV cargo |

EV type |

EV cellular source |

Involved patho/physiological processes |

Refs |

| Fibulin 1, Comp, Plasminogen and the Matricellular proteins thrombospondin 1 and 4, Vinculin and Fermt3 |

Small and large EVs |

Rat microglia |

Adhesion/extracellular matrix organization |

[48] |

| Cathepsin D and C, Lamp1, Vcp and CD68 |

Small and large EVs |

Rat microglia |

Autophagy-lysosomal pathway |

[48] |

| Capzb, Cap1 and ARP2 actin related protein |

Small and large EVs |

Rat microglia |

Cytoskeleton organization |

[48] |

MHC-II |

Small EVs |

Murine macrophages and dendritic cells |

Dissemination and presentation of

foreign antigens

|

[55] |

| Large EVs |

Human dendritic cells |

[39] |

| Small and large EVs |

Murine macrophages |

[56] |

| Gpi, Ldha, Mdh2, Tranketolase, Glutamate dehydrogenase 1, Acacb, and others |

Small and large EVs |

Rat microglia |

Energy metabolism |

[48] |

| CD14 |

EVs |

Murine macrophages |

Inflammation

|

[61] |

| GAPDH |

Small and large EVs |

Murine microglia |

[60] |

| IL-18 |

Large EVs |

Human macrophages |

[6] |

IL1b |

Large EVs |

Human monocytes

Rat microglia

Human dendritic cells |

[42]

[40]

[39] |

| Small EVs |

Murine macrophages |

[49] |

| IL-Ra |

Large EVs |

Murine macrophages |

[62] |

Inflammasome components |

Large EVs |

Rat microglia

Human dendritic cells |

[40] [39] |

| Small EVs |

Murine macrophages

Murine microglia |

[49] [54] |

| TACE |

Small EVs |

Mouse macrophages |

[64] |

| TF |

Large EVs |

Human dendritic cells

Murine macrophages |

[38]

[65] |

| TNF |

Large EVs |

Murine macrophage |

[7] |

| Aβ |

Large EVs |

Murine microglia

Rat microglia |

Neurodegeneration

|

[67,70]

[69] |

| Tau protein |

Small EVs |

Murine microglia |

[71,73] |

| Small EVs |

Murine microglia |

[72] |

| α-synuclein |

Small EVs |

Murine microglia |

[74,75] |

6. Conclusions

At inflammatory or damaged sites P2X7R activation by extracellular ATP or NAD+ promotes massive shedding of large EVs from the plasma membrane, via translocation of acid sphingomyelinase, and release of small EVs from multivesicular bodies, via inflammasome activation. The generated EVs expose MHCII on their surface, specific inflammatory miRNAs cargo in their lumen, and carry and release inflammatory cytokines into the extracellular space, promoting a local acute inflammatory response. Encapsulation into EVs can enhance cytokine activity, as shown for TNF, and by preventing cytokine degradation can deliver inflammatory signals to distant cells and tissues.

P2X7R-dependent EV release also represents a mechanism for the cells to get rid of unwanted materials, such as misfolded proteins (aβ, tau and a-synuclein), which are resistant to degradation, and to disseminate them throughout the brain. Encapsulation into EVs can also increase the activity of misfolded proteins. In fact, Aβ, tau and α−synuclein induce/propagate pathology more efficiently when associated to EVs, indicating that higher activity of EV-associated proteins compared to free soluble forms is not a mere consequence of protection from degradation.

Further research is needed to better characterize the molecules modulating or amplifying the inflammatory/degenerative response that are released as part of EVs upon P2X7R activation, in light of the emerging role of P2X7R inhibitors as promising therapeutic tools for limiting neurodegenerative and inflammatory processes.

Funding

This work was funded by Ministry of Health, grant number RF-2018-12365333.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Abbreviations

AIM2, Absent-in-melanoma 2; ASC, Apoptosis-associated speck-like protein containing a CARD; A-SMase, Acid sphingomyelinase; Aβ, Beta amyloid; eATP, Extracellular ATP; EVs, Extracellular vesicles; GAPDH, Glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase; Hrs, Hepatocyte growth factor–regulated tyrosine kinase substrate; IL, Interleukin; IL-Ra, Interleukin-1 receptor antagonist; ILV, Intraluminal vesicle; MHC-II, Major histocompatibility complex class II; MVBs, multivesicular bobies; NAD+, Nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide; NLRC4, NLR Family CARD Domain Containing 4; NLRP1, NLR Family Pyrin Domain Containing 1; NLRP3, NLR Family Pyrin Domain Containing 3; P2X7R, P2X7 receptor; PS, Phosphatidylserine; RILP, Rab-interacting lysosomal protein; TACE, TNF converting enzyme; TBI, Traumatic brain injury; TF, Tissue factor; TNF, Tumor necrosis factor.

References

- Steinberg, T.H.; Newman, A.S.; Swansonq, J.A.; Silverstein, S.C. ATP4-Permeabilizes the Plasma Membrane of Mouse Macrophages to Fluorescent Dyes*. Chemists 1987, 262, 88–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mutini, C.; Falzoni, S.; Ferrari, D.; Chiozzi, P.; Morelli, A.; Baricordi, O.R.; Collo, G.; Ricciardi-Castagnoli, P.; Di Virgilio, F. Mouse Dendritic Cells Express the P2X7 Purinergic Receptor: Characterization and Possible Participation in Antigen Presentation. J. Immunol. 1999, 163, 1958–1965. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cockcroft, S.; Gomperts, B.D. ATP induces nucleotide permeability in rat mast cells. 1979, 279, 541–2. 2. [CrossRef]

- Visentin, S.; Renzi, M.; Frank, C.; Greco, A.; Levi, G. Two different ionotropic receptors are activated by ATP in rat microglia. J. Physiol. 1999, 519, 723. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ferrari, D.; Pizzirani, C.; Adinolfi, E.; Lemoli, R.M.; Curti, A.; Idzko, M.; Panther, E.; Di Virgilio, F. The P2X7 receptor: a key player in IL-1 processing and release. J. Immunol. 2006, 176, 3877–3883. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gulinelli, S.; Salaro, E.; Vuerich, M.; Bozzato, D.; Pizzirani, C.; Bolognesi, G.; Idzko, M.; Virgilio, F. Di; Ferrari, D. IL-18 associates to microvesicles shed from human macrophages by a LPS/TLR-4 independent mechanism in response to P2X receptor stimulation. Eur. J. Immunol. 2012, 42, 3334–3345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Soni, S.; O’Dea, K.P.; Tan, Y.Y.; Cho, K.; Abe, E.; Romano, R.; Cui, J.; Ma, D.; Sarathchandra, P.; Wilson, M.R.; et al. ATP redirects cytokine trafficking and promotes novel membrane TNF signaling via microvesicles. FASEB J. 2019, 33, 6442–6455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grassi, F. The P2X7 Receptor as Regulator of T Cell Development and Function. Front. Immunol. 2020, 11, 1179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carotti, V.; Rigalli, J.P.; van Asbeck-van der Wijst, J.; Hoenderop, J.G.J. Interplay between purinergic signalling and extracellular vesicles in health and disease. Biochem. Pharmacol. 2022, 203, 115192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sperlágh, B.; Vizi, E.S.; Wirkner, K.; Illes, P. P2X7 receptors in the nervous system. Prog. Neurobiol. 2006, 78, 327–346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Y.F.; Tang, Y.; Illes, P. Astrocytic and Oligodendrocytic P2X7 Receptors Determine Neuronal Functions in the CNS. Front. Mol. Neurosci. 2021, 14, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Welter-Stahl, L.; da Silva, C.M.; Schachter, J.; Persechini, P.M.; Souza, H.S.; Ojcius, D.M.; Coutinho-Silva, R. Expression of purinergic receptors and modulation of P2X7 function by the inflammatory cytokine IFNγ in human epithelial cells. Biochim. Biophys. Acta - Biomembr. 2009, 1788, 1176–1187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ray, F.R.; Huang, W.; Slater, M.; Barden, J.A. Purinergic receptor distribution in endothelial cells in blood vessels: A basis for selection of coronary artery grafts. Atherosclerosis 2002, 162, 55–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Agrawal, A.; Gartland, A. P2X7 receptors: role in bone cell formation and function. J. Mol. Endocrinol. 2015, 54, R75–R88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Solini, A.; Chiozzi, P.; Falzoni, S.; Morelli, A.; Fellin, R.; Di Virgilio, F. High glucose modulates P2X7 receptor-mediated function in human primary fibroblasts. Diabetologia 2000, 43, 1248–1256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, X.; Hu, B.; Wang, L.; Xia, Q.; Ni, X. P2X7 receptor-mediated phenotype switching of pulmonary artery smooth muscle cells in hypoxia. Mol. Biol. Rep. 2021, 48, 2133–2142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Scarpellino, G.; Genova, T.; Munaron, L. Purinergic P2X7 Receptor: A Cation Channel Sensitive to Tumor Microenvironment. Recent Pat. Anticancer. Drug Discov. 2019, 14, 32–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Di Virgilio, F. P2X7 is a cytotoxic receptor….maybe not: implications for cancer. Purinergic Signal. 2021, 17, 55–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, L.H.; Caseley, E.A.; Muench, S.P.; Roger, S. Structural basis for the functional properties of the P2X7 receptor for extracellular ATP. Purinergic Signal. 2021, 17, 331–344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- North, R.A. Molecular physiology of P2X receptors. Physiol. Rev. 2002, 82, 1013–1067. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khadra, A.; Tomić, M.; Yan, Z.; Zemkova, H.; Sherman, A.; Stojilkovic, S.S. Dual Gating Mechanism and Function of P2X7 Receptor Channels. Biophys. J. 2013, 104, 2612–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Faas, M.M.; Sáez, T.; de Vos, P. Extracellular ATP and adenosine: The Yin and Yang in immune responses? Mol. Aspects Med. 2017, 55, 9–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bianco, F.; Ceruti, S.; Colombo, A.; Fumagalli, M.; Ferrari, D.; Pizzirani, C.; Matteoli, M.; Di Virgilio, F.; Abbracchio, M.P.; Verderio, C. A role for P2X7 in microglial proliferation. J. Neurochem. 2006, 99, 745–758. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Monif, M.; Reid, C.A.; Powell, K.L.; Smart, M.L.; Williams, D.A. The P2X7 receptor drives microglial activation and proliferation: a trophic role for P2X7R pore. J. Neurosci. 2009, 29, 3781–3791. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pelegrin, P. P2X7 receptor and the NLRP3 inflammasome: Partners in crime. Biochem. Pharmacol. 2021, 187, 114385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Orioli, E.; De Marchi, E.; Giuliani, A.L.; Adinolfi, E. P2X7 Receptor Orchestrates Multiple Signalling Pathways Triggering Inflammation, Autophagy and Metabolic/Trophic Responses. Curr. Med. Chem. 2017, 24, 1–1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sharma, D.; Kanneganti, T.D. The cell biology of inflammasomes: Mechanisms of inflammasome activation and regulation. J. Cell Biol. 2016, 213, 617–629. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Di Virgilio, F. Liaisons dangereuses: P2X7 and the inflammasome. Trends Pharmacol. Sci. 2007, 28, 465–472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martinon, F.; Burns, K.; Tschopp, J. The Inflammasome: A molecular platform triggering activation of inflammatory caspases and processing of proIL-β. Mol. Cell 2002, 10, 417–426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adriouch, S.; Bannas, P.; Schwarz, N.; Fliegert, R.; Guse, A.H.; Seman, M.; Haag, F.; Koch-Nolte, F. ADP-ribosylation at R125 gates the P2X7 ion channel by presenting a covalent ligand to its nucleotide binding site. 2008, 22, 861–9. 9. [CrossRef]

- Rissiek, B.; Haag, F.; Boyer, O.; Koch-Nolte, F.; Adriouch, S. P2X7 on mouse T cells: one channel, many functions. 2015, 6, 204. [CrossRef]

- Adriouch, S.; Hubert, S.; Pechberty, S.; Koch-Nolte, F.; Haag, F.; Seman, M. NAD+ released during inflammation participates in T cell homeostasis by inducing ART2-mediated death of naive T cells in vivo. J. Immunol. 2007, 179, 186–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Niel, G.; Raposo, G. Shedding light on the cell biology of extracellular vesicles. 2018, 19, 213–228. [CrossRef]

- Théry, C.; Witwer, K.W.; Aikawa, E.; Alcaraz, M.J.; Anderson, J.D.; Andriantsitohaina, R.; Antoniou, A.; Arab, T.; Archer, F.; Atkin-Smith, G.K.; et al. Minimal information for studies of extracellular vesicles 2018 (MISEV2018): a position statement of the International Society for Extracellular Vesicles and update of the MISEV2014 guidelines. https://doi.org/10.1080/20013078.2018.1535750 2018, 7. [CrossRef]

- Quek, C.; Hill, A.F. The role of extracellular vesicles in neurodegenerative diseases. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2017, 483, 1178–1186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yáñez-Mó, M.; Siljander, P.R.M.; Andreu, Z.; Zavec, A.B.; Borràs, F.E.; Buzas, E.I.; Buzas, K.; Casal, E.; Cappello, F.; Carvalho, J.; et al. Biological properties of extracellular vesicles and their physiological functions. J. Extracell. Vesicles 2015, 4, 1–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gabrielli, M.; Raffaele, S.; Fumagalli, M.; Verderio, C. The multiple faces of extracellular vesicles released by microglia: Where are we 10 years after? Front Cell Neurosci. 2022, 16, 984690. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Baroni, M.; Pizzirani, C.; Pinotti, M.; Ferrari, D.; Adinolfi, E.; Calzavarini, S.; Caruso, P.; Bernardi, F.; Di Virgilio, F. Stimulation of P2 (P2X 7 ) receptors in human dendritic cells induces the release of tissue factor-bearing microparticles. FASEB J. 2007, 21, 1926–1933. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pizzirani, C.; Ferrari, D.; Chiozzi, P.; Adinolfi, E.; Sandonà, D.; Savaglio, E.; Di Virgilio, F. Stimulation of P2 receptors causes release of IL-1-loaded microvesicles from human dendritic cells. Blood 2007, 109, 3856–3864. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bianco, F.; Pravettoni, E.; Colombo, A.; Schenk, U.; Möller, T.; Matteoli, M.; Verderio, C. Astrocyte-derived ATP induces vesicle shedding and IL-1 beta release from microglia. J. Immunol. 2005, 174, 7268–7277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thomas, L.M.; Salter, R.D. Activation of macrophages by P2X 7-induced microvesicles from myeloid cells is mediated by phospholipids and is partially dependent on TLR4. 2010, 185, 3740–3749. [CrossRef]

- MacKenzie, A.; Wilson, H.L.; Kiss-Toth, E.; Dower, S.K.; North, R.A.; Surprenant, A. Rapid secretion of interleukin-1β by microvesicle shedding. Immunity 2001, 15, 825–835. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bianco, F.; Perrotta, C.; Novellino, L.; Francolini, M.; Riganti, L.; Menna, E.; Saglietti, L.; Schuchman, E.H.; Furlan, R.; Clementi, E.; et al. Acid sphingomyelinase activity triggers microparticle release from glial cells. EMBO J. 2009, 28, 1043–1054. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morelli, A.; Chiozzi, P.; Chiesa, A.; Ferrari, D.; Sanz, J.M.; Falzoni, S.; Pinton, P.; Rizzuto, R.; Olson, M.F.; Di Virgilio, F. Extracellular ATP Causes ROCK I-dependent Bleb Formation in P2X 7-transfected HEK293 Cells □ V. Mol. Biol. Cell 2003, 14, 2655–2664. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pfeiffer, Z.A.; Aga, M.; Prabhu, U.; Watters, J.J.; Hall, D.J.; Bertics, P.J. The nucleotide receptor P2X7 mediates actin reorganization and membrane blebbing in RAW 264. 7 macrophages via p38 MAP kinase and Rho. 2004, 75, 1173–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verhoef, P.A.; Estacion, M.; Schilling, W.; Dubyak, G.R. P2X7 receptor-dependent blebbing and the activation of Rho-effector kinases, caspases, and IL-1 beta release. J. Immunol. 2003, 170, 5728–5738. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.; Zhao, Z.; Ji, R.; Zhu, J.; Sui, Q.Q.; Knight, G.E.; Burnstock, G.; He, C.; Yuan, H.; Xiang, Z. Inhibition of P2X7 receptors improves outcomes after traumatic brain injury in rats. Purinergic Signal. 2017, 13, 529–544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Drago, F.; Lombardi, M.; Prada, I.; Gabrielli, M.; Joshi, P.; Cojoc, D.; Franck, J.; Fournier, I.; Vizioli, J.; Verderio, C. ATP modifies the proteome of extracellular vesicles released by microglia and influences their action on astrocytes. Front. Pharmacol. 2017, 8, 910. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Qu, Y.; Franchi, L.; Nunez, G.; Dubyak, G.R. Nonclassical IL-1 beta secretion stimulated by P2X7 receptors is dependent on inflammasome activation and correlated with exosome release in murine macrophages. J. Immunol. 2007, 179, 1913–1925. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Qu, Y.; Dubyak, G.R. P2X7 receptors regulate multiple types of membrane trafficking responses and non-classical secretion pathways. Purinergic Signal. 2009, 5, 163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wozniak, A.L.; Adams, A.; King, K.E.; Dunn, W.; Christenson, L.K.; Hung, W.T.; Weinman, S.A. The RNA binding protein FMR1 controls selective exosomal miRNA cargo loading during inflammation. J. Cell Biol. 2020, 219, e201912074. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ruan, Z.; Takamatsu-Yukawa, K.; Wang, Y.; Ushman, M.L.; Thomas Labadorf, A.; Ericsson, M.; Ikezu, S.; Ikezu, T. Functional genome-wide short hairpin RNA library screening identifies key molecules for extracellular vesicle secretion from microglia Graphical abstract. 2022. [CrossRef]

- Rubartelli, A.; Sitia, R. Secretion of Mammalian Proteins that Lack a Signal Sequence. 1997, 87–114. [CrossRef]

- Sarkar, S.; Rokad, D.; Malovic, E.; Luo, J.; Harischandra, D.S.; Jin, H.; Anantharam, V.; Huang, X.; Lewis, M.; Kanthasamy, A.; et al. Manganese activates NLRP3 inflammasome signaling and propagates exosomal release of ASC in microglial cells. Sci. Signal. 2019, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qu, Y.; Ramachandra, L.; Mohr, S.; Franchi, L.; Harding, C. V.; Nunez, G.; Dubyak, G.R. P2X7 receptor-stimulated secretion of MHC class II-containing exosomes requires the ASC/NLRP3 inflammasome but is independent of caspase-1. J. Immunol. 2009, 182, 5052–5062. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramachandra, L.; Qu, Y.; Wang, Y.; Lewis, C.J.; Cobb, B.A.; Takatsu, K.; Boom, W.H.; Dubyak, G.R.; Harding, C. V. Mycobacterium tuberculosis Synergizes with ATP To Induce Release of Microvesicles and Exosomes Containing Major Histocompatibility Complex Class II Molecules Capable of Antigen Presentation. Infect. Immun. 2010, 78, 5116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barrera-Avalos, C.; Briceño, P.; Valdés, D.; Imarai, M.; Leiva-Salcedo, E.; Rojo, L.E.; Milla, L.A.; Huidobro-Toro, J.P.; Robles-Planells, C.; Escobar, A.; et al. P2X7 receptor is essential for cross-dressing of bone marrow-derived dendritic cells. iScience 2021, 24, 103520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeng, F.; Morelli, A.E. Extracellular vesicle-mediated MHC cross-dressing in immune homeostasis, transplantation, infectious diseases, and cancer. Semin. Immunopathol. 2018, 40, 477–490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verderio, C.; Muzio, L.; Turola, E.; Bergami, A.; Novellino, L.; Ruffini, F.; Riganti, L.; Corradini, I.; Francolini, M.; Garzetti, L.; et al. Myeloid microvesicles are a marker and therapeutic target for neuroinflammation. Ann. Neurol. 2012, 72, 610–624. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Takenouchi, T.; Tsukimoto, M.; Iwamaru, Y.; Sugama, S.; Sekiyama, K.; Sato, M.; Kojima, S.; Hashimoto, M.; Kitani, H. Extracellular ATP induces unconventional release of glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase from microglial cells. Immunol. Lett. 2015, 167, 116–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alarcón-Vila, C.; Baroja-Mazo, A.; de Torre-Minguela, C.; Martínez, C.M.; Martínez-García, J.J.; Martínez-Banaclocha, H.; García-Palenciano, C.; Pelegrin, P. CD14 release induced by P2X7 receptor restricts inflammation and increases survival during sepsis. Elife 2020, 9, 1–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wilson, H.L.; Francis, S.E.; Dower, S.K.; Crossman, D.C. Secretion of intracellular IL-1 receptor antagonist (type 1) is dependent on P2X7 receptor activation. J. Immunol. 2004, 173, 1202–1208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Arend, W.P. The balance between IL-1 and IL-1Ra in disease. Cytokine Growth Factor Rev. 2002, 13, 323–340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Barberà-Cremades, M.; Gómez, A.I.; Baroja-Mazo, A.; Martínez-Alarcón, L.; Martínez, C.M.; de Torre-Minguela, C.; Pelegrín, P. P2X7 Receptor Induces Tumor Necrosis Factor-α Converting Enzyme Activation and Release to Boost TNF-α Production. Front. Immunol. 2017, 8, 862. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moore, S.F.; MacKenzie, A.B. Murine macrophage P2X7 receptors support rapid prothrombotic responses. Cell. Signal. 2007, 19, 855–866. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- D’Arrigo, G.; Gabrielli, M.; Scaroni, F.; Swuec, P.; Amin, L.; Pegoraro, A.; Adinolfi, E.; Di Virgilio, F.; Cojoc, D.; Legname, G.; et al. Astrocytes-derived extracellular vesicles in motion at the neuron surface: Involvement of the prion protein. J. Extracell. vesicles 2021, 10, e12114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gabrielli, M.; Prada, I.; Joshi, P.; Falcicchia, C.; D’Arrigo, G.; Rutigliano, G.; Battocchio, E.; Zenatelli, R.; Tozzi, F.; Radeghieri, A.; et al. Microglial large extracellular vesicles propagate early synaptic dysfunction in Alzheimer’s disease. Brain 2022, 145, 2849–2868. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gu, B.J.; Rathsam, C.; Stokes, L.; McGeachie, A.B.; Wiley, J.S. Extracellular ATP dissociates nonmuscle myosin from P2X7 complex: This dissociation regulates P2X7 pore formation. Am. J. Physiol. - Cell Physiol. 2009, 297, 430–439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joshi, P.; Turola, E.; Ruiz, A.; Bergami, A.; Libera, D.D.; Benussi, L.; Giussani, P.; Magnani, G.; Comi, G.; Legname, G.; et al. Microglia convert aggregated amyloid-β into neurotoxic forms through the shedding of microvesicles. Cell Death Differ. 2014, 21, 582–593. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gouwens, L.K.; Ismail, M.S.; Rogers, V.A.; Zeller, N.T.; Garrad, E.C.; Amtashar, F.S.; Makoni, N.J.; Osborn, D.C.; Nichols, M.R. Aβ42 Protofibrils Interact with and Are Trafficked through Microglial-Derived Microvesicles. ACS Chem. Neurosci. 2018, 9, 1416–1425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Asai, H.; Ikezu, S.; Tsunoda, S.; Medalla, M.; Luebke, J.; Haydar, T.; Wolozin, B.; Butovsky, O.; Kügler, S.; Ikezu, T. Depletion of microglia and inhibition of exosome synthesis halt tau propagation. Nat. Neurosci. 2015, 18, 1584–1593. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Crotti, A.; Sait, H.R.; McAvoy, K.M.; Estrada, K.; Ergun, A.; Szak, S.; Marsh, G.; Jandreski, L.; Peterson, M.; Reynolds, T.L.; et al. BIN1 favors the spreading of Tau via extracellular vesicles. Sci. Rep. 2019, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ruan, Z.; Delpech, J.C.; Venkatesan Kalavai, S.; Van Enoo, A.A.; Hu, J.; Ikezu, S.; Ikezu, T. P2RX7 inhibitor suppresses exosome secretion and disease phenotype in P301S tau transgenic mice. Mol. Neurodegener. 2020, 15, 47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fan, R.Z.; Guo, M.; Luo, S.; Cui, M.; Tieu, K. Exosome release and neuropathology induced by α-synuclein: new insights into protective mechanisms of Drp1 inhibition. Acta Neuropathol. Commun. 2019, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guo, M.; Wang, J.; Zhao, Y.; Feng, Y.; Han, S.; Dong, Q.; Cui, M.; Tieu, K. Microglial exosomes facilitate α-synuclein transmission in Parkinson’s disease. Brain 2020, 143, 1476–1497. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gabrielli, M.; Tozzi, F.; Verderio, C.; Origlia, N. Emerging Roles of Extracellular Vesicles in Alzheimer’s Disease: Focus on Synaptic Dysfunction and Vesicle–Neuron Interaction. Cells 2023, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdullah, M.; Ruan, Z.; Bueser, K.R.; Ikezu, S.; Ikezu, T. The systemic disruption of P2rx7 alleviates tau pathology in P301S tau mice via inhibition of extracellular vesicle release. Alzheimer’s Dement. 2022, 18, e064257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Francistiová, L.; Bianchi, C.; Di Lauro, C.; Sebastián-Serrano, Á.; de Diego-García, L.; Kobolák, J.; Dinnyés, A.; Díaz-Hernández, M. The Role of P2X7 Receptor in Alzheimer’s Disease. Front. Mol. Neurosci. 2020, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carvalho, K.; Martin, E.; Ces, A.; Sarrazin, N.; Lagouge-Roussey, P.; Nous, C.; Boucherit, L.; Youssef, I.; Prigent, A.; Faivre, E.; et al. P2X7-deficiency improves plasticity and cognitive abilities in a mouse model of Tauopathy. Prog. Neurobiol. 2021, 206, 102139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Di Lauro, C.; Bianchi, C.; Sebastián-Serrano, Á.; Soria-Tobar, L.; Alvarez-Castelao, B.; Nicke, A.; Díaz-Hernández, M. P2X7 receptor blockade reduces tau induced toxicity, therapeutic implications in tauopathies. Prog. Neurobiol. 2022, 208, 102173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Martin, E.; Amar, M.; Dalle, C.; Youssef, I.; Boucher, C.; Le Duigou, C.; Brückner, M.; Prigent, A.; Sazdovitch, V.; Halle, A.; et al. New role of P2X7 receptor in an Alzheimer’s disease mouse model. Mol. Psychiatry 2018 241 2019, 24, 108–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Illes, P.; Rubini, P.; Huang, L.; Tang, Y. The P2X7 receptor: a new therapeutic target in Alzheimer’s disease. https://doi.org/10.1080/14728222.2019.1575811 2019, 23, 165–176. [CrossRef]

- Xia, Y.; Zhang, G.; Han, C.; Ma, K.; Guo, X.; Wan, F.; Kou, L.; Yin, S.; Liu, L.; Huang, J.; et al. Microglia as modulators of exosomal alpha-synuclein transmission. Cell Death Dis. 2019, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).