1. Introduction

Streptococcus pneumoniae is a Gram-positive, lancet-shaped bacterium that contributes significantly to microbial diseases worldwide.

S. pneumoniae is commonly found in the nasopharynx of humans where 40-50% of healthy children and 20%-30% of healthy adults are carriers [

1]. However,

S. pneumoniae can cause a diversity of pneumococcal diseases (PD) such as Otitis Media (OM), pneumonia, sinusitis, septicemia, and meningitis [

2,

3,

4]. For example, children ≤ 4 years old have a high incidence rate of OM [

5], with certain local populations in Sub-Saharan Africa and Asia showing 100% incidence rates for children ages 1-4 [

6].

S. pneumoniae can spread from the nasopharyngeal into the lower airways and cause pneumonia. The estimated worldwide incidence rate of community-acquired pneumonia ranges between 1.5-14 cases per 1000/year [

7]. Pneumonia can be caused by multiple viral, bacterial, and fungal pathogens and is responsible for approximately 2.5 million deaths worldwide/year [

8,

9]. Among bacterial pneumonia, about 90% is caused by

S. pneumoniae [

10]. In addition,

S. pneumoniae can pass the blood-brain barrier (BBB) to cause pneumococcal meningitis. Meningitis is estimated at over 1.2 million cases worldwide each year, and if untreated, fatality rate can reach 70% and leaving 1 in 5 survivors with permanent brain damage [

11].

Among the >100 known serotypes in

S. pneumoniae, 16 cause approximately 90% of PDs worldwide [

12]. For example, Hausdorff et al. [

13] found that serotypes 4, 6, 9, 14, 18, 19, and 23 cause approximately 70-88% of PDs in young children in North America, Europe, Africa, and several regions in other continents. While much is known about the association between serotypes and PD, the relatively low number of serotypes in this species offered limited discriminating power to distinguish strains and was insufficient for many types of epidemiological investigations about this pathogen. In 1998, a multilocus sequence typing (MLST) scheme was established for genotyping strains of

S. pneumoniae. In this scheme, DNA sequences at the following seven housekeeping genes were recommended to identify the genotypes for individual isolates: d-alanine-d-alanine ligase (

ddl), signal peptidase I (

spi), transketolase (

recP), shikimate dehydrogenase (

aroE), glucose-6-phosphate dehydrogenase (

gdh), glucose kinase (

gki), and xanthine phosphoribosyltransferase (

xpt) [

12]. At each locus, a unique sequence was assigned a distinct allele and combinations of allele types (ATs) at the seven housekeeping loci were used to provide a sequence type (ST) for each isolate [

12]. The MLST scheme showed much greater discriminatory power over serotyping and provided a consistent method for many researchers around the world to expand on the MLST database of

S. pneumoniae over the following 25 years.

As of November 2022, there were 74346

S. pneumoniae isolates with MLST data at the seven loci deposited at PubMLST.org. These isolates came from diverse geographical populations and spanned over nine decades. Using MLST data, previous studies have described the associations between STs, serotypes, antibiotic resistance, and/or PD prevalence among various demographic groups [e.g., 14-22]. However, most of the studies have focused on local level, with a few included isolates and data from multiple countries. Interestingly, several studies identified the emergence of non- pneumococcal conjugate vaccine (PCV) serotypes following the introduction of PCVs. As of 2020, the WHO documented that 149 countries have introduced PCV [

10]. However, the effects of PCV introduction on ST distributions at the global level have not been investigated.

In this study, we aimed to use the archived global MLST data on S. pneumoniae to address several population genetic and epidemiological questions. First, how are STs distributed at the continental and national/regional levels? Second, are geographic populations genetically differentiated at the continental and national/regional levels? Third, what is the effect of PCV implementation on the distributions of STs? Because PCVs were designed to target the dominant serotypes, we expect that certain STs will be more impacted by PCV implementation than other STs. And lastly, is there evidence for recombination within individual continental populations and the global population of S. pneumoniae?

4. Discussion

In this study, we extracted and analyzed the genetic, geographical, ecological, and temporal data of the global S. pneumoniae isolates deposited within PubMLST up to November 2022. The extracted global population included 74346 isolates representing 17915 STs. The isolates were distributed among 6 continents and 115 countries. Among the six continents, Europe contributed the most isolates (32.403%). Among the 115 countries, USA had the most isolates (11.679%). The patterns of distribution of isolates among continents and countries likely reflected sampling and research efforts by scientists working on this pathogen as well as the differences in relative importance of S. pneumoniae to public health and in available resource for research among countries and continents.

Our analyses revealed a diversity of STs within most countries and continents. Indeed, most STs (15929 of 17915 STs) were found in only one continent. However, although only 36 STs were shared among all six continents, they represented over 20.53% of all the isolates in the database, consistent with recent gene flow and that a relatively small number of STs dominated the global

S. pneumoniae population. Our results are similar to previous research results that showed a few serotypes causing most pneumococcal diseases [

12]. A similar pattern was seen across temporal scales where a relatively small number of STs persisted across decades. Among these, ST191 was collected across all time intervals (

Figure S1). ST191 is among the top 50 most frequent STs and is associated with serotype 7F, a PCV-13 target [

30,

31]. ST191 was a frequent ST prior to PCV-13 implementation. However, introduction of PCV-13 has resulted in a reduction of ST191 frequency over time. While incomplete sampling could have contributed to the low number of shared STs across the analyzed time frames, the persistence of ST191 suggests its significant adaptability in human populations. Interestingly, between 1990-2022, only 1532 STs were collected, representing about 10% of all STs in the database but these STs account for 41.87% of all the isolates in the dataset. The overrepresented STs indicate that a relatively small number of STs are highly transmissible and/or pathogenic to humans. Further genetic and genomic studies of isolates of these frequent STs (e.g., ST199, ST180, and ST81) could help reveal the potential mechanisms for their broad distribution and/or persistence in humans.

Among geographical regions, we observed differences in the prevalence of PCV-13 and non-PCV-13 (top 50) STs. In Thailand, 4/5 of the most frequently represented STs belonged to serotypes targeted by PCV-13, including ST4414 (of serotype 19F), a top 50 PCV-13 ST, found so far only in Asia, with 99.53% of the strains of this ST reported from Thailand (

Figure S1). The high frequency of STs associated with PCV-13 is consistent with the lack of PCV immunization program in Thailand [

32]. In South Korea, the introduction of PCV-13 resulted in the emergence of novel STs due to serotype replacement [

33]. A similar pattern was found in other countries such as South Africa, the UK, and the USA where the implementation of PCV into their immunization programs [

32] caused STs not associated with PCV-13 to increase in their relative prevalence in these countries.

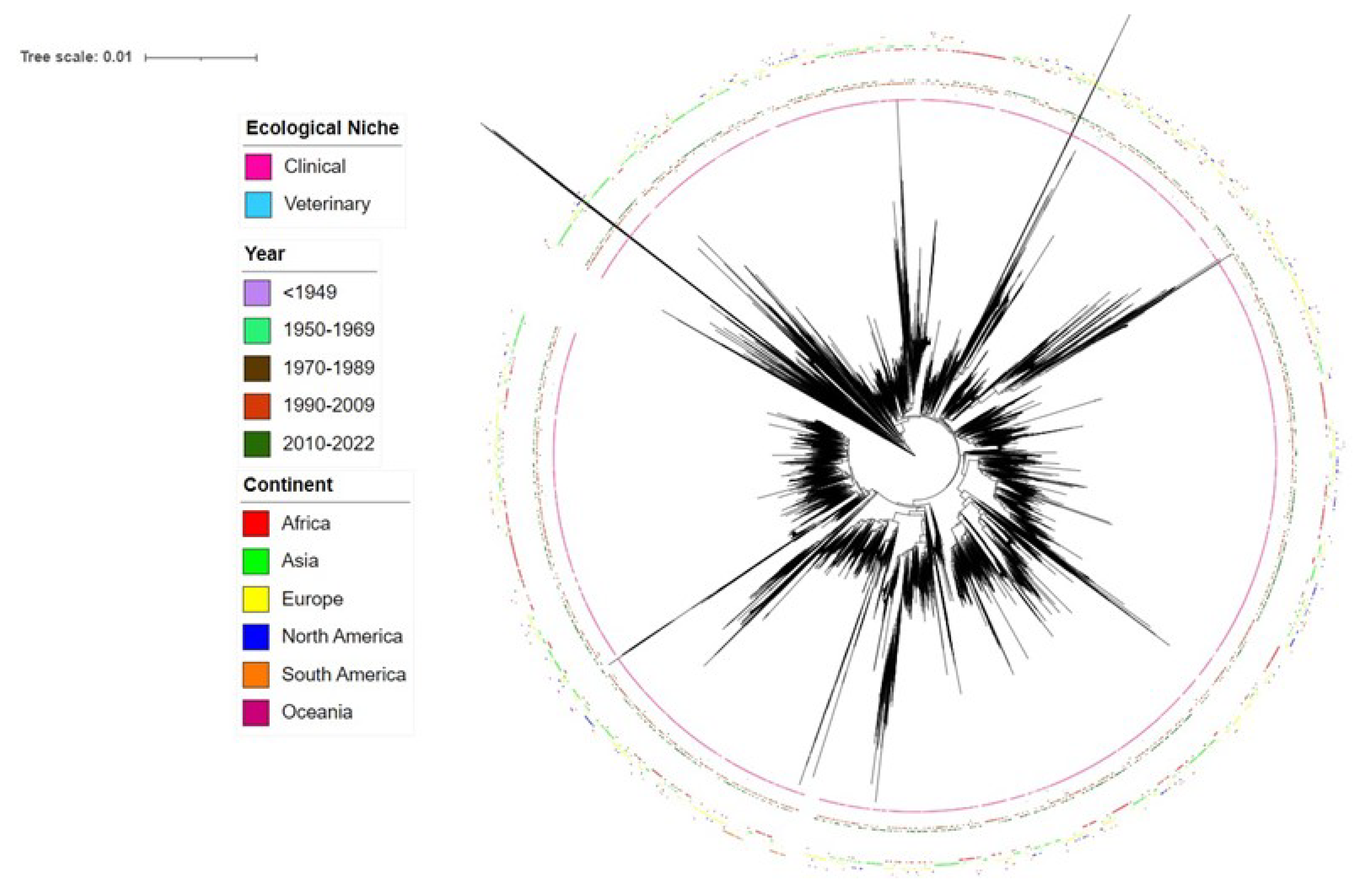

Phylogenetic analyses of all STs revealed both divergent STs and closely related STs (

Figure 1). Interestingly, our phylogenetic analyses revealed that two STs, ST14613 and ST17858, in the current MLST database for

S. pneumoniae were very divergent from most other STs in the database. Further analyses through BLAST revealed that these two STs belonged to

Streptococcus mitis, a close relative of

S. pneumoniae. Significantly,

S. mitis has been found to be a source for capsular polysaccharide variation for

S. pneumoniae through horizontal gene transfer and can contribute to vaccine escape in

S. pneumoniae [

34].

Similar to the overall phylogenetic relationships among all STs, the top 50 most frequent STs in the database also showed both significant divergence and close relatedness among each other. Though small clusters of PCV-13 associated STs were found, STs associated with PCV-13 were overall inter-mixed with those not associated with PCV-13 (

Supplementary Figures S2 and S3). Interestingly, 7 STs (ST156, ST81, ST63, ST193, ST320, ST695, and ST172) were each associated with more than one serotype covered by PCV-13. Three STs (ST199, ST162, and ST156) contained strains that were initially associated with PCV-13 prior to PCV implementation but changed their serotypes following PCV implementation. Previous literature has also identified ST199 switched from serotype 19A to 15B following PCV-7 implementation [

35]. These findings suggest evidence of capsular switching, a process by which a new capsule operon is acquired through horizontal gene transfer (HGT) [

36]. Due to flexibility and ease of DNA uptake in pneumococci, high rates of recombination via frequent HGT within the

cps operon could have occurred, causing increases in non-PCV-13 serotypes [

37]. Further genomic comparisons should help identify the relationship between STs and

cps operon allele variation and how mutation and/or HGT might have impacted capsular switching and serotype changes in the global population.

Analysis of molecular variance revealed statistically significant genetic differentiations among geographical, temporal, and ecological populations of

S. pneumoniae, rejecting the null hypothesis of no genetic differentiations among sub-populations in each the three types of analyses. However, in all cases, both the non-clone-corrected datasets and the clone-corrected datasets revealed that most genetic variations were found within subpopulations rather than between subpopulations. Among these, the highest inter-subpopulation differentiation (~12%) was observed for the non-clone corrected data between clinical and veterinary samples. Further investigation revealed that 46/112 veterinary isolates represented STs that were unique to veterinary niches. Among those 46 isolates, 26 belonged to ST6937 and 10 isolates belonged to ST6934. Localized selection and clonal expansion have likely contributed to the observed patterns. Differences between clinical and veterinary/environmental samples have also been reported in other microbial pathogens such as

Campylobacter jejuni and

Streptococcus agalactiae [

38,

39].

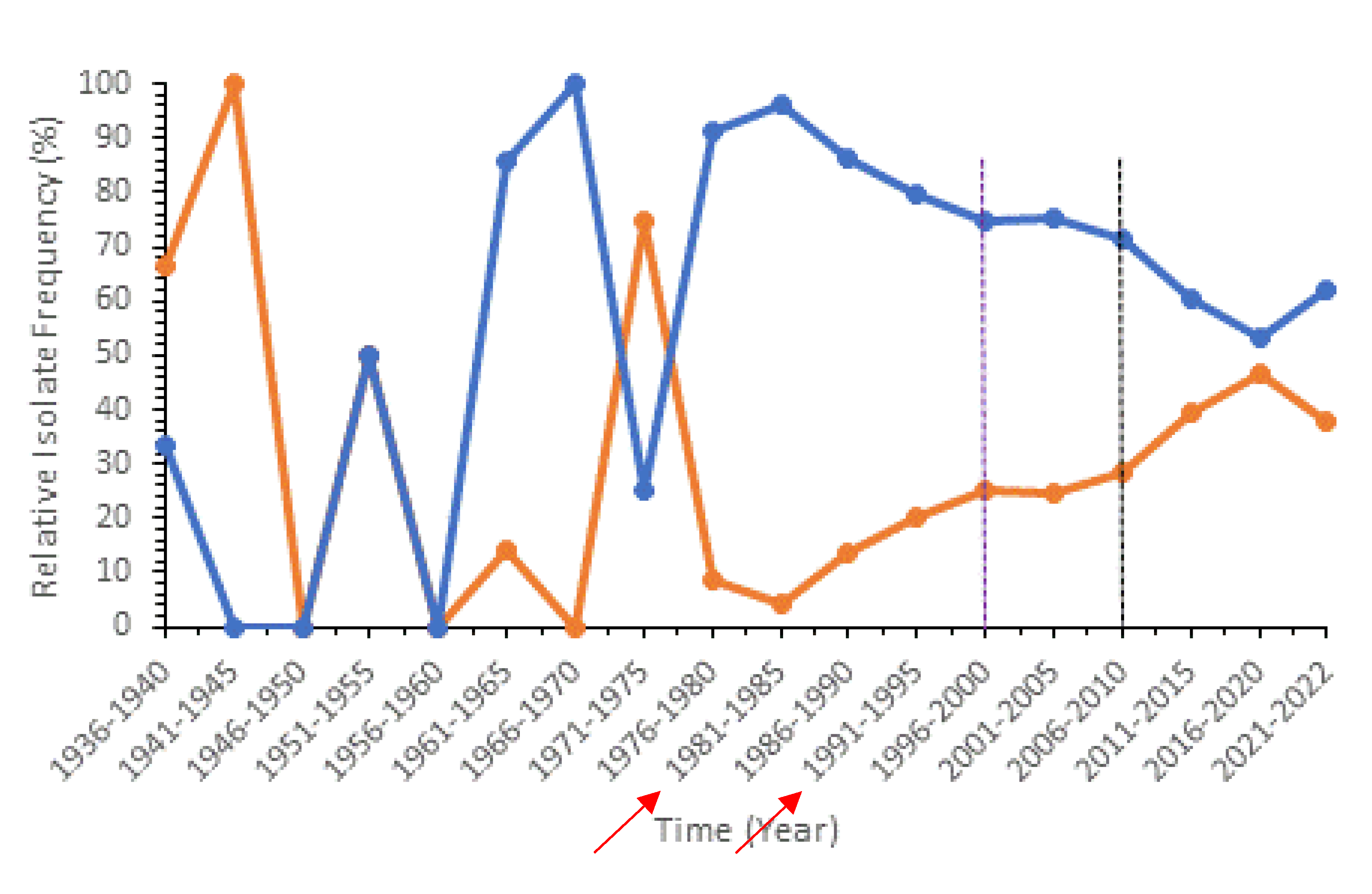

Population genetic analyses between pre- and post- PCV implementation revealed a decrease in relative frequency of PCV-13 associated STs and an increase in frequency of non-PCV-13 (top 50) STs as well as significant genetic differentiations between them based on AMOVA (

Figure 2). These global patterns are consistent with previous literature in England and Wales which found that PCV implementation led to a rise in non-PCV serotype infections [

40]. Interestingly in our analysis, we noticed a significant rise in some non-PCV-13 (top 50) STs that were not associated with new serotypes targeted by the upcoming PCV-20 (serotypes 35B, 23B, 9N, 15BC, and 6C). On the other hand, STs associated with serotypes 10A, 15B, and 33F, which are targeted by the new PCV-20, were not among the top 50 most represented STs. Thus, our results suggest that PCV-20 is not as optimized as it could be. We believe that further vaccine development and optimizations should take the global ST distributions into account to produce higher-valent PCVs. At the national level, we observed unique trends for countries that have implemented PCV and countries that have not (

Figure S11). In Thailand, which has not implemented PCV into their national immunization program (NIP), the relative frequency of PCV-13 associated STs increased over time, reaching almost 100%. In countries that have implemented PCV into their NIP, a reduction in PCV-13 associated STs is typically seen after PCV-13/PCV-10 introduction together with an increase in non-PCV-13 (top 50) STs. This observation is consistent with the previous finding that ST4414, a unique PCV-13 ST only found in Asia, has contributed to increased PCV-13 ST frequency in Thailand (

Figure S1).

S. pneumoniae has shown to be capable of importing DNA through transformation and homologous recombination, generating recombinant genotypes [

41]. In this study, we found that strains of the same ST or closely related STs were often associated the same serotypes. However, differences were also found, consistent with recombination and horizontal gene transfer in natural populations of this species. In our analyses, all continent populations of

S. pneumoniae showed evidence of recombination among the seven loci used for MLST. However, none of the analyzed populations showed evidence of random recombination, even in the clone-corrected samples.

In conclusion, global analyses of published MLST data for

S. pneumoniae revealed great diversity and distribution of STs spatially, temporally, and phylogenetically. Analysis of molecular variance quantified the genetic variations within and among

S. pneumoniae subpopulations. Implementation of PCV revealed an impact on both PCV-13 STs and non-PCV-13 (top 50) STs globally. We also demonstrated non-random association among alleles at the seven MLST loci. It is important to note that MLST data for

S. pneumoniae only reflects data collected and deposited by researchers. The distributions observed in this study may underrepresent the actual distributions of

S. pneumoniae. As new PCVs are being produced to reduce the incidence of pneumococcal diseases among global populations, the rise of non-PCV serotypes due to serotype replacement and capsular switching caused by recombination and horizontal gene transfer remains a major concern. At present, two new higher-valent PCVs, PCV-15 and PCV-20, are being implemented across the world to cover a wider range of serotypes causing pneumococcal diseases. However, information on the coverage and effectiveness of these new vaccines at the global level is scarce. At present, PCV-13 is still recommended by the US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) for infants and younger children. However, as shown in our analyses, after PCV-13 implementation, new serotypes and new STs not associated with PCV-13 emerged and spread, reduced the effectiveness of PCV-13 [

42]. New PCVs should be designed to target the most prevalent STs and serotypes that are not covered by previous PCVs in order to maximize the efficacy of the new vaccines. Indeed, genotype information from global isolates should be continuously deposited into the pubmlst database for monitoring the potential spatial and temporal patterns related to

S. pneumoniae and pneumococcal diseases. Such data, in combination with those on host and environmental factors related to

S. pneumoniae and pneumococcal diseases could help develop effective public health policies against this important human pathogen (Xu 2022).

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, J.X.; methodology, J.D., M.H.; software, J.D., M.H., J.X.; validation, J.D., M.H., J.X.; formal analysis, J.D.; investigation, J.D.; resources, M.H., J.X.; data curation, J.D.; writing—original draft preparation, J.D.; writing—review and editing, J.X.; visualization, J.D., M.H.; supervision, J.X.; project administration, J.X.; funding acquisition, J.X. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.