Submitted:

28 April 2023

Posted:

28 April 2023

You are already at the latest version

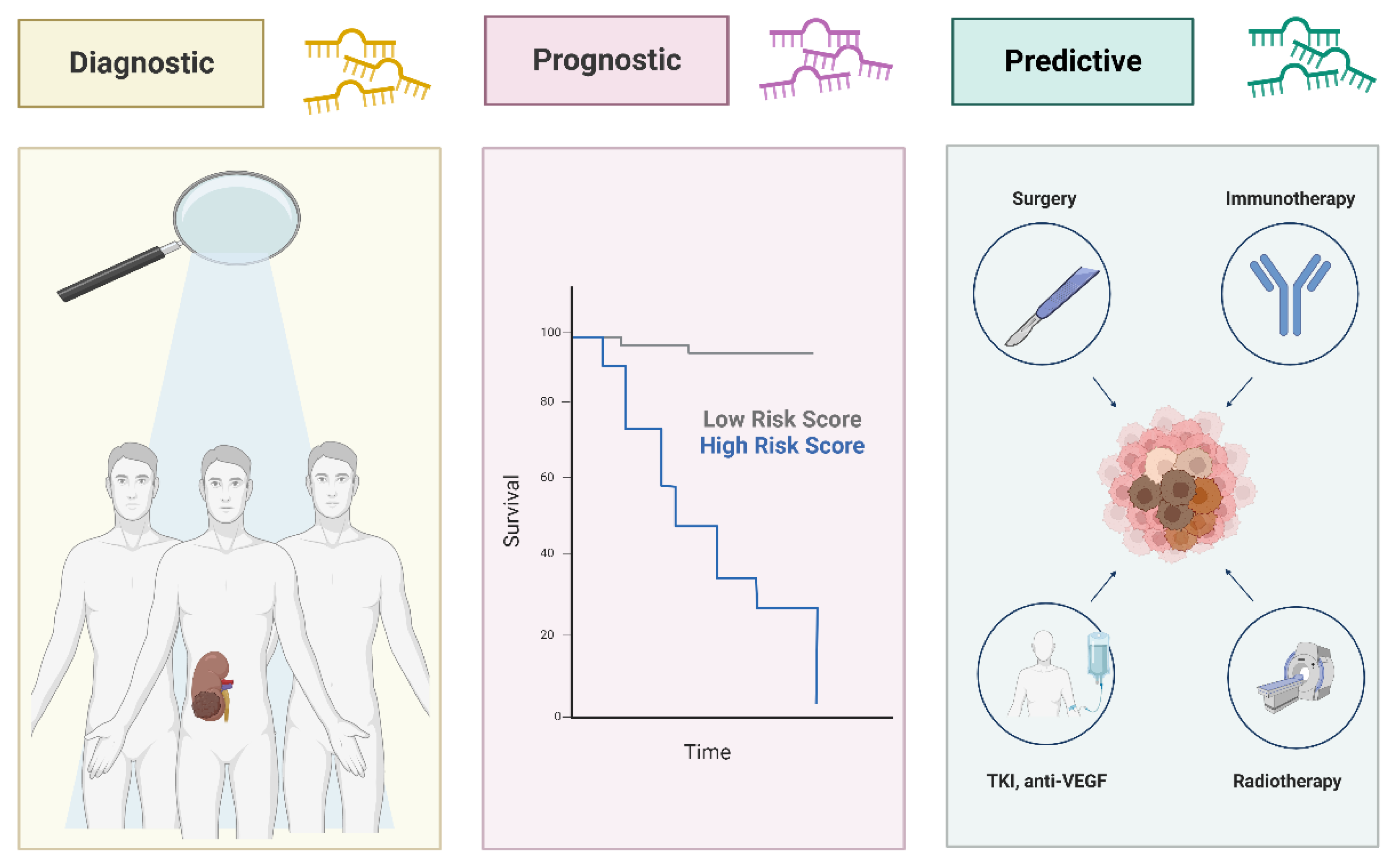

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Renal Cell Carcinoma: clinical diagnosis and staging

2. RCC treatments: advances and challenges in the lack of biomarkers

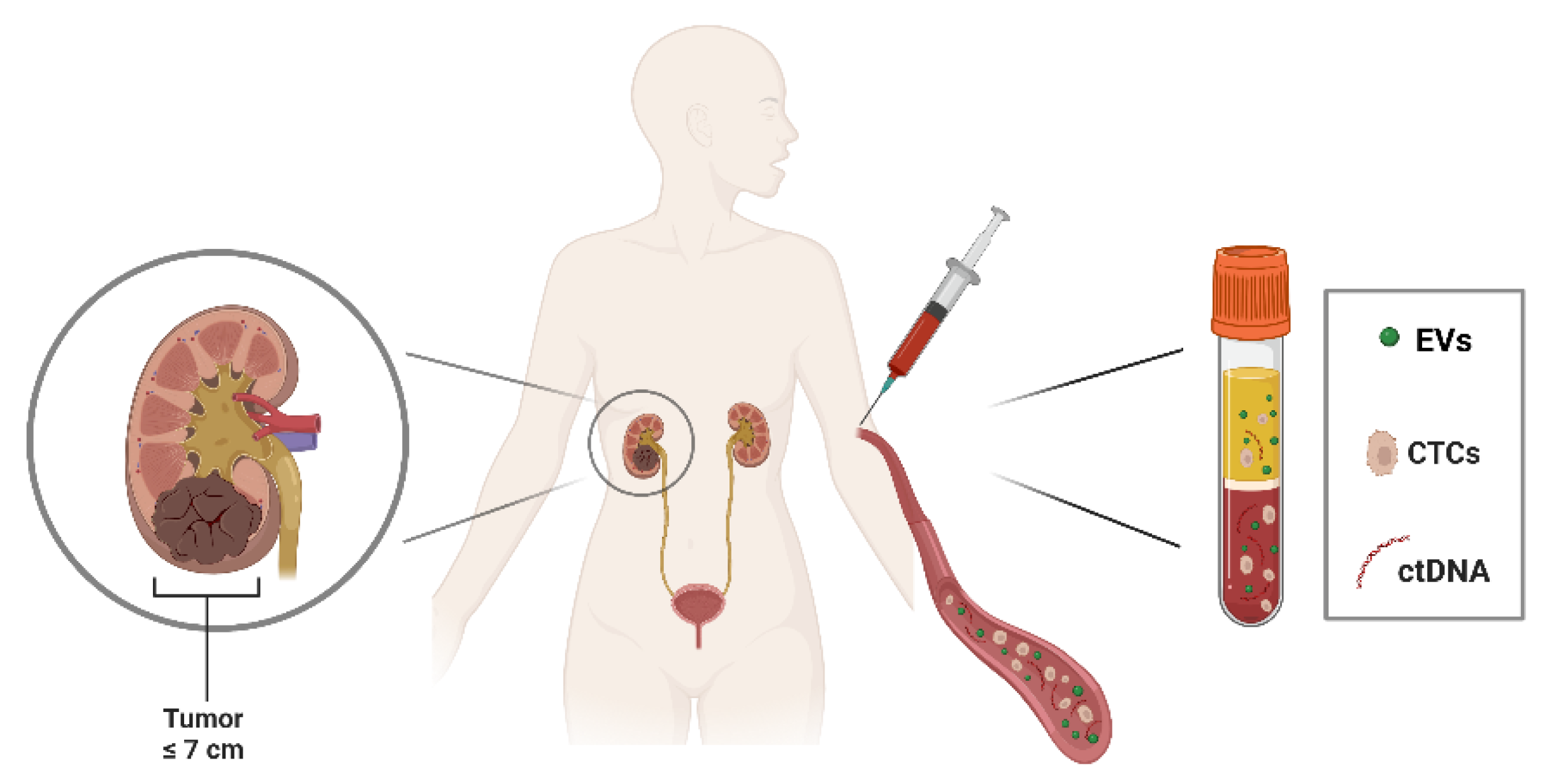

3. Liquid biopsy in RCC

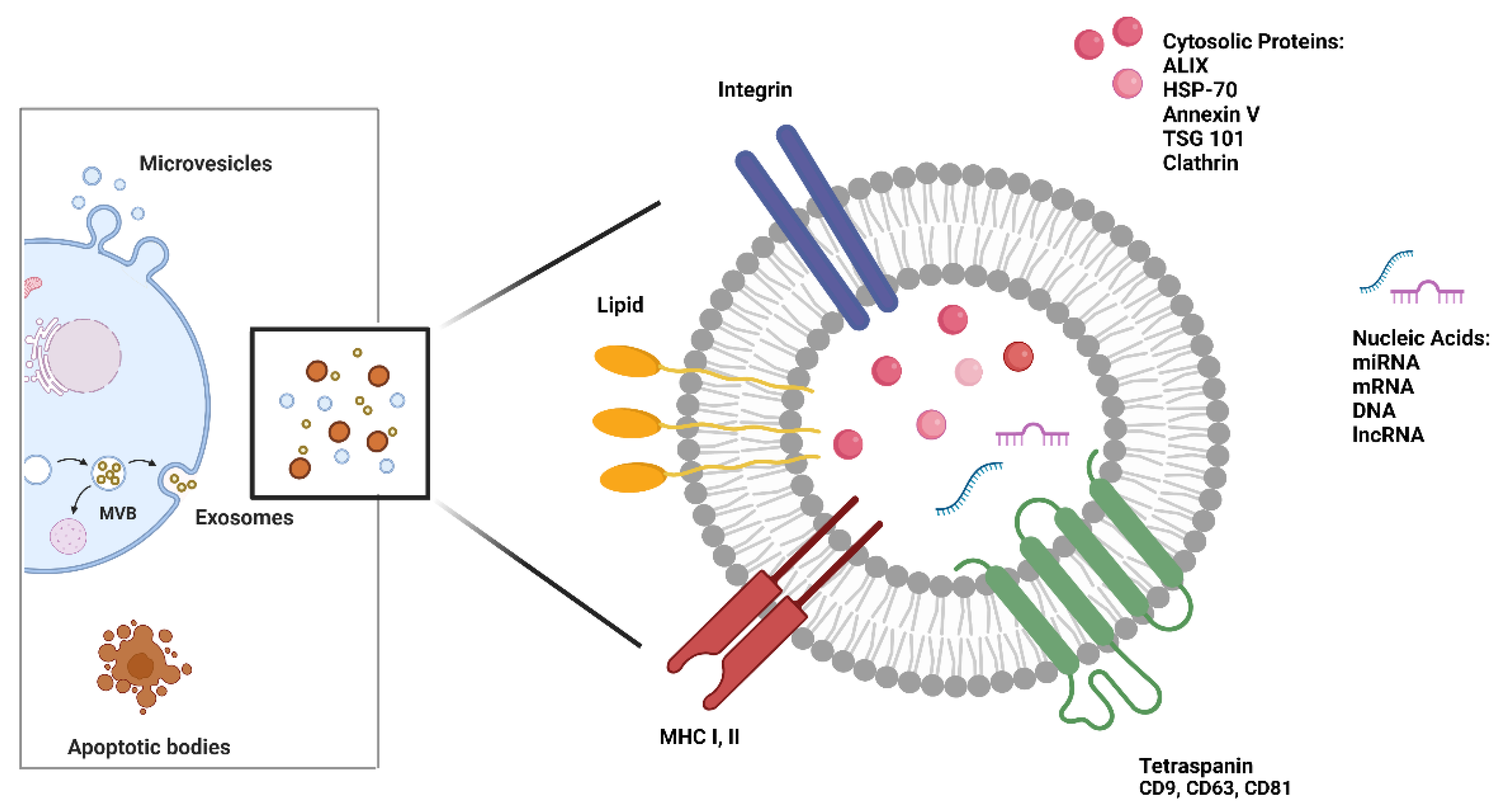

4. Extracellular vesicles: biogenesis and role in RCC

5. MicroRNA (miRNA): from free circulating to EV packaged biomarkers in RCC

| miRNA | Expression Changes in RCC |

Source | Therapeutic Role | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| miR-106 | Up-regulated | Serum | Diagnostic, Predictive |

Tusong et al., 2017 [51] |

| miR-122-5p | Up-regulated | Serum | Prognostic | Heinemann et al., 2018 [72] |

| miR-1233 | Up-regulated | Exosomes- Serum |

Diagnostic, Predictive |

Zhang et al., 2018 [60] |

| Up-regulated | Plasma | Diagnostic, Prognostic |

Dias et al., 2017 [56] | |

| Up-regulated | Serum | Diagnostic | Wulfken et al., 2011 [59] | |

| miR-141 | Down-regulated | Serum | Diagnostic | Cheng et al., 2013 [52] |

| miR-144-3p | Up-regulated | Plasma | Diagnostic, Prognostic |

Lou et al., 2017 [69] |

| miR-149-3p | Up-regulated | Exosomes- Plasma |

Diagnostic | Xiao et al., 2020 [58] |

| miR-150 | Down-regulated | Plasma | Prognostic | Chanudet et al., 2017 [73] |

| miR-182-5p | Down-regulated | Serum | Diagnostic | Huang et al., 2020 [61] |

| miR-187 | Down-regulated | Plasma | Diagnostic, Prognostic |

Zhao et al., 2013 [70] |

| miR-193a-3p | Up-regulated | Serum | Diagnostic | Wang et al., 2015 [63] |

| miR-196a | Up-regulated | Serum | Diagnostic, Prognostic |

Huang et al., 2020 [68] |

| miR-206 | Up-regulated | Serum | Prognostic | Heinemann et al., 2018 [72] |

| miR-20b-5p | Down-regulated | Serum | Diagnostic | Huang et al., 2020 [68] |

| miR-21 | Up-regulated | Serum | Diagnostic, Predictive |

Tusong et al., 2017 [51] |

| Up-regulated | Serum | Diagnostic, Prognostic |

Cheng et al., 2013 [52] | |

| Up-regulated | Serum | Diagnostic, Prognostic |

Liu et al., 2017 [53] | |

| miR-210 | Up-regulated | Serum | Diagnostic, Predictive |

Fedorko et al., 2015 [64] |

| Up-regulated | Exosomes- Serum |

Diagnostic, Predictive |

Zhang et al., 2018 [60] | |

| Up-regulated | Plasma | Diagnostic, Prognostic |

Dias et al., 2017 [56] | |

| Up-regulated | Serum | Diagnostic | Iwamoto et al., 2014 [66] | |

| Up-regulated | Serum | Diagnostic, Predictive |

Zhao et al., 2013 [65] | |

| miR-218 | Up-regulated | Plasma | Diagnostic | Dias et al., 2017 [56] |

| miR-22 | Down-regulated | Serum | Diagnostic, Prognostic, Predictive |

Li et al., 2017 [77] |

| miR-221 | Up-regulated | Plasma | Diagnostic, Prognostic |

Teixeira et al., 2014 [57] |

| Up-regulated | Plasma | Diagnostic, Prognostic |

Dias et al., 2017 [56] | |

| miR-222 | Up-regulated | Plasma | Diagnostic | Teixeira et al., 2014 [57] |

| miR-224 | Up-regulated | Serum | Diagnostic | Cheng et al., 2013 [52] |

| Up-regulated | Serum | Diagnostic | Huang et al., 2020 [61] | |

| miR-28-5p | Down-regulated | Serum | Diagnostic | Wang et al., 2015 [63] |

| miR-30a-5p | Down-regulated | Serum | Diagnostic | Huang et al., 2020 [68] |

| miR-34a | Up-regulated | Serum | Diagnostic | Cheng et al., 2013 [52] |

| miR-34b-3p | Down-regulated | Serum | Diagnostic | Huang et al., 2020 [61] |

| miR-362 | Up-regulated | Serum | Diagnostic | Wang et al., 2015 [63] |

| miR-378 | Up-regulated | Serum | Diagnostic, Predictive |

Fedorko et al., 2015 [64] |

| Down-regulated | Serum | Diagnostic | Wang et al., 2015 [63] | |

| Up-regulated | Serum | Diagnostic | Redova et al., 2012 [62] | |

| miR-424-3p | Up-regulated | Exosomes- Plasma |

Diagnostic | Xiao et al., 2020 [58] |

| miR-451 | Down-regulated | Serum | Diagnostic | Redova et al., 2012 [62] |

| miR-483-5p | Down-regulated | Plasma | Diagnostic, Prognostic, Predictive |

Wang et al., 2021 [76] |

| miR-508-3p | Down-regulated | Serum | Diagnostic | Liu et al., 2019 [54] |

| miR-572 | Up-regulated | Serum | Diagnostic | Wang et al., 2015 [63] |

| miR-625-3p | Down-regulated | Serum | Diagnostic | Zhao et al., 2019 [55] |

| miR-765 | Down-regulated | Plasma | Predictive | Xiao et al., 2020 [67] |

| miR-885-5p | Up-regulated | Serum | Diagnostic | Liu et al., 2019 [54] |

| miR-92a-1-5p | Down-regulated | Exosomes- Plasma |

Diagnostic | Xiao et al., 2020 [58] |

| miR-1293 | Down-regulated | EVs- Plasma |

Prognostic, Predictive |

Dias et al., 2020 [75] |

| miR-301a-3p | Up-regulated | EVs- Plasma |

Prognostic, Predictive |

Dias et al., 2020 [75] |

| miR-let-7i-5p | Down-regulated | Exosomes- Plasma |

Prognostic | Du et al., 2017 [74] |

| miR-183-5p | Up-regulated | Serum | Diagnostic, Prognostic |

Zhang et al., 2015 [71] |

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Shi, L.; Wang, M.; Li, H.; You, P. MicroRNAs in Body Fluids: A More Promising Biomarker for Clear Cell Renal Cell Carcinoma. Cancer Manag Res 2021, 13, 7663–7675. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Spadaccino, F.; Gigante, M.; Netti, G.S.; Rocchetti, M.T.; Franzin, R.; Gesualdo, L.; Castellano, G.; Stallone, G.; Ranieri, E. The Ambivalent Role of MiRNAs in Carcinogenesis: Involvement in Renal Cell Carcinoma and Their Clinical Applications. Pharmaceuticals (Basel) 2021, 14, 322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Singh, D. Current Updates and Future Perspectives on the Management of Renal Cell Carcinoma. Life Sci 2021, 264, 118632. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Padala, S.A.; Barsouk, A.; Thandra, K.C.; Saginala, K.; Mohammed, A.; Vakiti, A.; Rawla, P.; Barsouk, A. Epidemiology of Renal Cell Carcinoma. World J Oncol 2020, 11, 79–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, C.; Liao, Z. Comparison of Radical Nephrectomy and Partial Nephrectomy for T1 Renal Cell Carcinoma: A Meta-Analysis. Urol Int 2018, 101, 175–183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alam, R.; Patel, H.D.; Osumah, T.; Srivastava, A.; Gorin, M.A.; Johnson, M.H.; Trock, B.J.; Chang, P.; Wagner, A.A.; McKiernan, J.M.; et al. Comparative Effectiveness of Management Options for Patients with Small Renal Masses: A Prospective Cohort Study. BJU International 2019, 123, 42–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Campbell, S.C.; Novick, A.C.; Belldegrun, A.; Blute, M.L.; Chow, G.K.; Derweesh, I.H.; Faraday, M.M.; Kaouk, J.H.; Leveillee, R.J.; Matin, S.F.; et al. Guideline for Management of the Clinical T1 Renal Mass. Journal of Urology 2009, 182, 1271–1279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marchioni, M.; Rivas, J.G.; Autran, A.; Socarras, M.; Albisinni, S.; Ferro, M.; Schips, L.; Scarpa, R.M.; Papalia, R.; Esperto, F. Biomarkers for Renal Cell Carcinoma Recurrence: State of the Art. Curr Urol Rep 2021, 22, 31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borchiellini, D.; Maillet, D. Clinical Activity of Immunotherapy-Based Combination First-Line Therapies for Metastatic Renal Cell Carcinoma: The Right Treatment for the Right Patient. Bulletin du Cancer 2022, 109, 2S4–2S18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.-W.; Rini, B.I.; Beckermann, K.E. Emerging Targets in Clear Cell Renal Cell Carcinoma. Cancers (Basel) 2022, 14, 4843. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tung, I.; Sahu, A. Immune Checkpoint Inhibitor in First-Line Treatment of Metastatic Renal Cell Carcinoma: A Review of Current Evidence and Future Directions. Front Oncol 2021, 11, 707214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iaxx, R.; Lefort, F.; Domblides, C.; Ravaud, A.; Bernhard, J.-C.; Gross-Goupil, M. An Evaluation of Cabozantinib for the Treatment of Renal Cell Carcinoma: Focus on Patient Selection and Perspectives. Ther Clin Risk Manag 2022, 18, 619–632. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Iacovelli, R.; Nolè, F.; Verri, E.; Renne, G.; Paglino, C.; Santoni, M.; Cossu Rocca, M.; Giglione, P.; Aurilio, G.; Cullurà, D.; et al. Prognostic Role of PD-L1 Expression in Renal Cell Carcinoma. A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Target Oncol 2016, 11, 143–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Carlsson, J.; Sundqvist, P.; Kosuta, V.; Fält, A.; Giunchi, F.; Fiorentino, M.; Davidsson, S. PD-L1 Expression Is Associated With Poor Prognosis in Renal Cell Carcinoma. Applied Immunohistochemistry & Molecular Morphology 2020, 28, 213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dudani, S.; Savard, M.-F.; Heng, D.Y.C. An Update on Predictive Biomarkers in Metastatic Renal Cell Carcinoma. Eur Urol Focus 2020, 6, 34–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Makhov, P.; Joshi, S.; Ghatalia, P.; Kutikov, A.; Uzzo, R.G.; Kolenko, V.M. RESISTANCE TO SYSTEMIC THERAPIES IN CLEAR CELL RENAL CELL CARCINOMA: MECHANISMS AND MANAGEMENT STRATEGIES. Mol Cancer Ther 2018, 17, 1355–1364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Grange, C.; Brossa, A.; Bussolati, B. Extracellular Vesicles and Carried MiRNAs in the Progression of Renal Cell Carcinoma. Int J Mol Sci 2019, 20, 1832. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gerlinger, M.; Rowan, A.J.; Horswell, S.; Math, M.; Larkin, J.; Endesfelder, D.; Gronroos, E.; Martinez, P.; Matthews, N.; Stewart, A.; et al. Intratumor Heterogeneity and Branched Evolution Revealed by Multiregion Sequencing. N Engl J Med 2012, 366, 883–892. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martins, V.R.; Dias, M.S.; Hainaut, P. Tumor-Cell-Derived Microvesicles as Carriers of Molecular Information in Cancer. Curr Opin Oncol 2013, 25, 66–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, W.; Hurley, J.; Roberts, D.; Chakrabortty, S.K.; Enderle, D.; Noerholm, M.; Breakefield, X.O.; Skog, J.K. Exosome-Based Liquid Biopsies in Cancer: Opportunities and Challenges. Ann Oncol 2021, 32, 466–477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lone, S.N.; Nisar, S.; Masoodi, T.; Singh, M.; Rizwan, A.; Hashem, S.; El-Rifai, W.; Bedognetti, D.; Batra, S.K.; Haris, M.; et al. Liquid Biopsy: A Step Closer to Transform Diagnosis, Prognosis and Future of Cancer Treatments. Molecular Cancer 2022, 21, 79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lakshminarayanan, H.; Rutishauser, D.; Schraml, P.; Moch, H.; Bolck, H.A. Liquid Biopsies in Renal Cell Carcinoma—Recent Advances and Promising New Technologies for the Early Detection of Metastatic Disease. Front Oncol 2020, 10, 582843. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Michela, B. Liquid Biopsy: A Family of Possible Diagnostic Tools. Diagnostics (Basel) 2021, 11, 1391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, M.; Li, L.; Zheng, J.; Li, Z.; Li, S.; Wang, K.; Chen, X. Liquid Biopsy at the Frontier in Renal Cell Carcinoma: Recent Analysis of Techniques and Clinical Application. Mol Cancer 2023, 22, 37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bade, R.M.; Schehr, J.L.; Emamekhoo, H.; Gibbs, B.K.; Rodems, T.S.; Mannino, M.C.; Desotelle, J.A.; Heninger, E.; Stahlfeld, C.N.; Sperger, J.M.; et al. Development and Initial Clinical Testing of a Multiplexed Circulating Tumor Cell Assay in Patients with Clear Cell Renal Cell Carcinoma. Mol Oncol 2021, 15, 2330–2344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nuzzo, P.V.; Berchuck, J.E.; Korthauer, K.; Spisak, S.; Nassar, A.H.; Abou Alaiwi, S.; Chakravarthy, A.; Shen, S.Y.; Bakouny, Z.; Boccardo, F.; et al. Detection of Renal Cell Carcinoma Using Plasma and Urine Cell-Free DNA Methylomes. Nat Med 2020, 26, 1041–1043. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sequeira, J.P.; Constâncio, V.; Salta, S.; Lobo, J.; Barros-Silva, D.; Carvalho-Maia, C.; Rodrigues, J.; Braga, I.; Henrique, R.; Jerónimo, C. LiKidMiRs: A DdPCR-Based Panel of 4 Circulating MiRNAs for Detection of Renal Cell Carcinoma. Cancers (Basel) 2022, 14, 858. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peter, M.R.; Zhao, F.; Jeyapala, R.; Kamdar, S.; Xu, W.; Hawkins, C.; Evans, A.J.; Fleshner, N.E.; Finelli, A.; Bapat, B. Investigating Urinary Circular RNA Biomarkers for Improved Detection of Renal Cell Carcinoma. Front Oncol 2021, 11, 814228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kohli, M.; Tan, W.; Vire, B.; Liaud, P.; Blairvacq, M.; Berthier, F.; Rouison, D.; Garnier, G.; Payen, L.; Cousin, T.; et al. Prognostic Value of Plasma HPG80 (Circulating Progastrin) in Metastatic Renal Cell Carcinoma. Cancers (Basel) 2021, 13, 375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.-L.; Zhang, P.; Li, H.-C.; Yang, X.-J.; Zhang, Y.-P.; Li, Z.-L.; Xue, L.; Xue, Y.-Q.; Li, H.-L.; Chen, Q.; et al. Dynamic Changes of Different Phenotypic and Genetic Circulating Tumor Cells as a Biomarker for Evaluating the Prognosis of RCC. Cancer Biol Ther 2019, 20, 505–512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yamamoto, Y.; Uemura, M.; Fujita, M.; Maejima, K.; Koh, Y.; Matsushita, M.; Nakano, K.; Hayashi, Y.; Wang, C.; Ishizuya, Y.; et al. Clinical Significance of the Mutational Landscape and Fragmentation of Circulating Tumor DNA in Renal Cell Carcinoma. Cancer Sci 2019, 110, 617–628. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yu, D.; Li, Y.; Wang, M.; Gu, J.; Xu, W.; Cai, H.; Fang, X.; Zhang, X. Exosomes as a New Frontier of Cancer Liquid Biopsy. Molecular Cancer 2022, 21, 56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zaborowski, M.P.; Balaj, L.; Breakefield, X.O.; Lai, C.P. Extracellular Vesicles: Composition, Biological Relevance, and Methods of Study. Bioscience 2015, 65, 783–797. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zaborowski, M.P.; Balaj, L.; Breakefield, X.O.; Lai, C.P. Extracellular Vesicles: Composition, Biological Relevance, and Methods of Study. BioScience 2015, 65, 783–797. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Théry, C.; Witwer, K.W.; Aikawa, E.; Alcaraz, M.J.; Anderson, J.D.; Andriantsitohaina, R.; Antoniou, A.; Arab, T.; Archer, F.; Atkin-Smith, G.K.; et al. Minimal Information for Studies of Extracellular Vesicles 2018 (MISEV2018): A Position Statement of the International Society for Extracellular Vesicles and Update of the MISEV2014 Guidelines. Journal of Extracellular Vesicles 2018, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lötvall, J.; Hill, A.F.; Hochberg, F.; Buzás, E.I.; Di Vizio, D.; Gardiner, C.; Gho, Y.S.; Kurochkin, I.V.; Mathivanan, S.; Quesenberry, P.; et al. Minimal Experimental Requirements for Definition of Extracellular Vesicles and Their Functions: A Position Statement from the International Society for Extracellular Vesicles. J Extracell Vesicles 2014, 3, 26913. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Peinado, H.; Lyden, D. Metastasis. 2017, 30, 836–848. 30. [CrossRef]

- Qian, Z.; Shen, Q.; Yang, X.; Qiu, Y.; Zhang, W. The Role of Extracellular Vesicles: An Epigenetic View of the Cancer Microenvironment. BioMed Research International 2015, 2015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grange, C.; Tapparo, M.; Collino, F.; Vitillo, L.; Damasco, C.; Deregibus, M.C.; Tetta, C.; Bussolati, B.; Camussi, G. Microvesicles Released from Human Renal Cancer Stem Cells Stimulate Angiogenesis and Formation of Lung Premetastatic Niche. Cancer Research 2011, 71, 5346–5356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lindoso, R.S.; Collino, F.; Camussi, G. Extracellular Vesicles Derived from Renal Cancer Stem Cells Induce a Pro-Tumorigenic Phenotype in Mesenchymal Stromal Cells. Oncotarget 2015, 6, 7959–7969. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Skotland, T.; Sagini, K.; Sandvig, K.; Llorente, A. An Emerging Focus on Lipids in Extracellular Vesicles. Advanced Drug Delivery Reviews 2020, 159, 308–321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rimmer, M.P.; Gregory, C.D.; Mitchell, R.T. Extracellular Vesicles in Urological Malignancies. Biochim Biophys Acta Rev Cancer 2021, 1876, None. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Barth, D.A.; Drula, R.; Ott, L.; Fabris, L.; Slaby, O.; Calin, G.A.; Pichler, M. Circulating Non-Coding RNAs in Renal Cell Carcinoma—Pathogenesis and Potential Implications as Clinical Biomarkers. Front Cell Dev Biol 2020, 8, 828. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Butz, H.; Nofech-Mozes, R.; Ding, Q.; Khella, H.W.Z.; Szabó, P.M.; Jewett, M.; Finelli, A.; Lee, J.; Ordon, M.; Stewart, R.; et al. Exosomal MicroRNAs Are Diagnostic Biomarkers and Can Mediate Cell–Cell Communication in Renal Cell Carcinoma. European Urology Focus 2016, 2, 210–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Grange, C.; Brossa, A.; Bussolati, B. Extracellular Vesicles and Carried MiRNAs in the Progression of Renal Cell Carcinoma. International Journal of Molecular Sciences 2019, 20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Horie, K.; Kawakami, K.; Fujita, Y.; Sugaya, M.; Kameyama, K.; Mizutani, K.; Deguchi, T.; Ito, M. Exosomes Expressing Carbonic Anhydrase 9 Promote Angiogenesis. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 2017, 492, 356–361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jingushi, K.; Uemura, M.; Ohnishi, N.; Nakata, W.; Fujita, K.; Naito, T.; Fujii, R.; Saichi, N.; Nonomura, N.; Tsujikawa, K.; et al. Extracellular Vesicles Isolated from Human Renal Cell Carcinoma Tissues Disrupt Vascular Endothelial Cell Morphology via Azurocidin. Int J Cancer 2018, 142, 607–617. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grange, C.; Tapparo, M.; Collino, F.; Vitillo, L.; Damasco, C.; Deregibus, M.C.; Tetta, C.; Bussolati, B.; Camussi, G. Microvesicles Released from Human Renal Cancer Stem Cells Stimulate Angiogenesis and Formation of Lung Premetastatic Niche. Cancer Research 2011, 71, 5346–5356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lindoso, R.S.; Collino, F.; Camussi, G. Extracellular Vesicles Derived from Renal Cancer Stem Cells Induce a Pro-Tumorigenic Phenotype in Mesenchymal Stromal Cells. Oncotarget 2015, 6, 7959–7969. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grange, C.; Tapparo, M.; Tritta, S.; Deregibus, M.C.; Battaglia, A.; Gontero, P.; Frea, B.; Camussi, G. Role of HLA-G and Extracellular Vesicles in Renal Cancer Stem Cell-Induced Inhibition of Dendritic Cell Differentiation. BMC Cancer 2015, 15, 1009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jansson, M.D.; Lund, A.H. MicroRNA and Cancer. Mol Oncol 2012, 6, 590–610. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, Y.; Croce, C.M. The Role of MicroRNAs in Human Cancer. Signal Transduct Target Ther 2016, 1, 15004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Challagundla, K.B.; Wise, P.M.; Neviani, P.; Chava, H.; Murtadha, M.; Xu, T.; Kennedy, R.; Ivan, C.; Zhang, X.; Vannini, I.; et al. Exosome-Mediated Transfer of MicroRNAs within the Tumor Microenvironment and Neuroblastoma Resistance to Chemotherapy. J Natl Cancer Inst 2015, 107, djv135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ellinger, J.; Gevensleben, H.; Müller, S.C.; Dietrich, D. The Emerging Role of Non-Coding Circulating RNA as a Biomarker in Renal Cell Carcinoma. Expert Rev Mol Diagn 2016, 16, 1059–1065. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lokeshwar, S.D.; Talukder, A.; Yates, T.J.; Hennig, M.J.P.; Garcia-Roig, M.; Lahorewala, S.S.; Mullani, N.N.; Klaassen, Z.; Kava, B.R.; Manoharan, M.; et al. Molecular Characterization of Renal Cell Carcinoma: A Potential Three-MicroRNA Prognostic Signature. Cancer Epidemiology, Biomarkers & Prevention 2018, 27, 464–472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsiakanikas, P.; Giaginis, C.; Kontos, C.K.; Scorilas, A. Clinical Utility of MicroRNAs in Renal Cell Carcinoma: Current Evidence and Future Perspectives. Expert Rev Mol Diagn 2018, 18, 981–991. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tusong, H.; Maolakuerban, N.; Guan, J.; Rexiati, M.; Wang, W.-G.; Azhati, B.; Nuerrula, Y.; Wang, Y.-J. Functional Analysis of Serum MicroRNAs MiR-21 and MiR-106a in Renal Cell Carcinoma. Cancer Biomark 2017, 18, 79–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, T.; Wang, L.; Li, Y.; Huang, C.; Zeng, L.; Yang, J. Differential MicroRNA Expression in Renal Cell Carcinoma. Oncol Lett 2013, 6, 769–776. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Z.; Lu, Y.; Xiao, Y.; Lu, Y. Upregulation of MiR-21 Expression Is a Valuable Predicator of Advanced Clinicopathological Features and Poor Prognosis in Patients with Renal Cell Carcinoma through the P53/P21-cyclin E2-Bax/Caspase-3 Signaling Pathway. Oncology Reports 2017, 37, 1437–1444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, S.; Deng, X.; Zhang, J. Identification of Dysregulated Serum MiR-508-3p and MiR-885-5p as Potential Diagnostic Biomarkers of Clear Cell Renal Carcinoma. Mol Med Rep 2019, 20, 5075–5083. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, L.; Liu, K.; Pan, X.; Quan, J.; Zhou, L.; Li, Z.; Lin, C.; Xu, J.; Xu, W.; Guan, X.; et al. MiR-625-3p Promotes Migration and Invasion and Reduces Apoptosis of Clear Cell Renal Cell Carcinoma. Am J Transl Res 2019, 11, 6475–6486. [Google Scholar]

- Dias, F.; Teixeira, A.L.; Ferreira, M.; Adem, B.; Bastos, N.; Vieira, J.; Fernandes, M.; Sequeira, M.I.; Maurício, J.; Lobo, F.; et al. Plasmatic MiR-210, MiR-221 and MiR-1233 Profile: Potential Liquid Biopsies Candidates for Renal Cell Carcinoma. Oncotarget 2017, 8, 103315–103326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teixeira, A.L.; Ferreira, M.; Silva, J.; Gomes, M.; Dias, F.; Santos, J.I.; Maurício, J.; Lobo, F.; Medeiros, R. Higher Circulating Expression Levels of MiR-221 Associated with Poor Overall Survival in Renal Cell Carcinoma Patients. Tumor Biol. 2014, 35, 4057–4066. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xiao, C.-T.; Lai, W.-J.; Zhu, W.-A.; Wang, H. MicroRNA Derived from Circulating Exosomes as Noninvasive Biomarkers for Diagnosing Renal Cell Carcinoma. Onco Targets Ther 2020, 13, 10765–10774. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wulfken, L.M.; Moritz, R.; Ohlmann, C.; Holdenrieder, S.; Jung, V.; Becker, F.; Herrmann, E.; Walgenbach-Brünagel, G.; Ruecker, A. von; Müller, S.C.; et al. MicroRNAs in Renal Cell Carcinoma: Diagnostic Implications of Serum MiR-1233 Levels. PLOS ONE 2011, 6, e25787. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, W.; Ni, M.; Su, Y.; Wang, H.; Zhu, S.; Zhao, A.; Li, G. MicroRNAs in Serum Exosomes as Potential Biomarkers in Clear-Cell Renal Cell Carcinoma. Eur Urol Focus 2018, 4, 412–419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, G.; Li, X.; Chen, Z.; Wang, J.; Zhang, C.; Chen, X.; Peng, X.; Liu, K.; Zhao, L.; Lai, Y.; et al. A Three-MicroRNA Panel in Serum: Serving as a Potential Diagnostic Biomarker for Renal Cell Carcinoma. Pathol. Oncol. Res. 2020, 26, 2425–2434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Redova, M.; Poprach, A.; Nekvindova, J.; Iliev, R.; Radova, L.; Lakomy, R.; Svoboda, M.; Vyzula, R.; Slaby, O. Circulating MiR-378 and MiR-451 in Serum Are Potential Biomarkers for Renal Cell Carcinoma. J Transl Med 2012, 10, 55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, C.; Hu, J.; Lu, M.; Gu, H.; Zhou, X.; Chen, X.; Zen, K.; Zhang, C.-Y.; Zhang, T.; Ge, J.; et al. A Panel of Five Serum MiRNAs as a Potential Diagnostic Tool for Early-Stage Renal Cell Carcinoma. Sci Rep 2015, 5, 7610. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fedorko, M.; Stanik, M.; Iliev, R.; Redova-Lojova, M.; Machackova, T.; Svoboda, M.; Pacik, D.; Dolezel, J.; Slaby, O. Combination of MiR-378 and MiR-210 Serum Levels Enables Sensitive Detection of Renal Cell Carcinoma. Int J Mol Sci 2015, 16, 23382–23389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, A.; Li, G.; Péoc’h, M.; Genin, C.; Gigante, M. Serum MiR-210 as a Novel Biomarker for Molecular Diagnosis of Clear Cell Renal Cell Carcinoma. Exp Mol Pathol 2013, 94, 115–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iwamoto, H.; Kanda, Y.; Sejima, T.; Osaki, M.; Okada, F.; Takenaka, A. Serum MiR-210 as a Potential Biomarker of Early Clear Cell Renal Cell Carcinoma. International Journal of Oncology 2014, 44, 53–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xiao, W.; Wang, C.; Chen, K.; Wang, T.; Xing, J.; Zhang, X.; Wang, X. MiR-765 Functions as a Tumour Suppressor and Eliminates Lipids in Clear Cell Renal Cell Carcinoma by Downregulating PLP2. EBioMedicine 2020, 51, 102622. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, G.; Li, H.; Wang, J.; Peng, X.; Liu, K.; Zhao, L.; Zhang, C.; Chen, X.; Lai, Y.; Ni, L. Combination of Tumor Suppressor MiR-20b-5p, MiR-30a-5p, and MiR-196a-5p as a Serum Diagnostic Panel for Renal Cell Carcinoma. Pathol Res Pract 2020, 216, 153152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lou, N.; Ruan, A.-M.; Qiu, B.; Bao, L.; Xu, Y.-C.; Zhao, Y.; Sun, R.-L.; Zhang, S.-T.; Xu, G.-H.; Ruan, H.-L.; et al. MiR-144-3p as a Novel Plasma Diagnostic Biomarker for Clear Cell Renal Cell Carcinoma. Urologic Oncology: Seminars and Original Investigations 2017, 35, 36–e7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, J.; Lei, T.; Xu, C.; Li, H.; Ma, W.; Yang, Y.; Fan, S.; Liu, Y. MicroRNA-187, down-Regulated in Clear Cell Renal Cell Carcinoma and Associated with Lower Survival, Inhibits Cell Growth and Migration Though Targeting B7-H3. Biochemical and Biophysical Research Communications 2013, 438, 439–444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, Q.; Di, W.; Dong, Y.; Lu, G.; Yu, J.; Li, J.; Li, P. High Serum MiR-183 Level Is Associated with Poor Responsiveness of Renal Cancer to Natural Killer Cells. Tumor Biol. 2015, 36, 9245–9249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Heinemann, F.G.; Tolkach, Y.; Deng, M.; Schmidt, D.; Perner, S.; Kristiansen, G.; Müller, S.C.; Ellinger, J. Serum MiR-122-5p and MiR-206 Expression: Non-Invasive Prognostic Biomarkers for Renal Cell Carcinoma. Clin Epigenetics 2018, 10, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chanudet, E.; Wozniak, M.B.; Bouaoun, L.; Byrnes, G.; Mukeriya, A.; Zaridze, D.; Brennan, P.; Muller, D.C.; Scelo, G. Large-Scale Genome-Wide Screening of Circulating MicroRNAs in Clear Cell Renal Cell Carcinoma Reveals Specific Signatures in Late-Stage Disease. International Journal of Cancer 2017, 141, 1730–1740. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du, M.; Giridhar, K.V.; Tian, Y.; Tschannen, M.R.; Zhu, J.; Huang, C.-C.; Kilari, D.; Kohli, M.; Wang, L. Plasma Exosomal MiRNAs-Based Prognosis in Metastatic Kidney Cancer. Oncotarget 2017, 8, 63703–63714. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dias, F.; Teixeira, A.L.; Nogueira, I.; Morais, M.; Maia, J.; Bodo, C.; Ferreira, M.; Silva, A.; Vilhena, M.; Lobo, J.; et al. Extracellular Vesicles Enriched in Hsa-MiR-301a-3p and Hsa-MiR-1293 Dynamics in Clear Cell Renal Cell Carcinoma Patients: Potential Biomarkers of Metastatic Disease. Cancers (Basel) 2020, 12, 1450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.-G.; Zhu, Y.-W.; Wang, T.; Chen, B.; Xing, J.-C.; Xiao, W. MiR-483-5p Downregulation Contributed to Cell Proliferation, Metastasis, and Inflammation of Clear Cell Renal Cell Carcinoma. The Kaohsiung Journal of Medical Sciences 2021, 37, 192–199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, M.; Sha, Y.; Zhang, X. MiR-22 Functions as a Biomarker and Regulates Cell Proliferation, Cycle, Apoptosis, Migration and Invasion in Renal Cell Carcinoma. Int J Clin Exp Pathol 2017, 10, 11425–11437. [Google Scholar]

- Sun, I.O.; Bae, Y.-U.; Lee, H.; Kim, H.; Jeon, J.S.; Noh, H.; Choi, J.-S.; Doh, K.-O.; Kwon, S.H. Circulating MiRNAs in Extracellular Vesicles Related to Treatment Response in Patients with Idiopathic Membranous Nephropathy. Journal of Translational Medicine 2022, 20, 224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sun, Z.; Shi, K.; Yang, S.; Liu, J.; Zhou, Q.; Wang, G.; Song, J.; Li, Z.; Zhang, Z.; Yuan, W. Effect of Exosomal MiRNA on Cancer Biology and Clinical Applications. Mol Cancer 2018, 17, 147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).