Submitted:

03 December 2024

Posted:

04 December 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

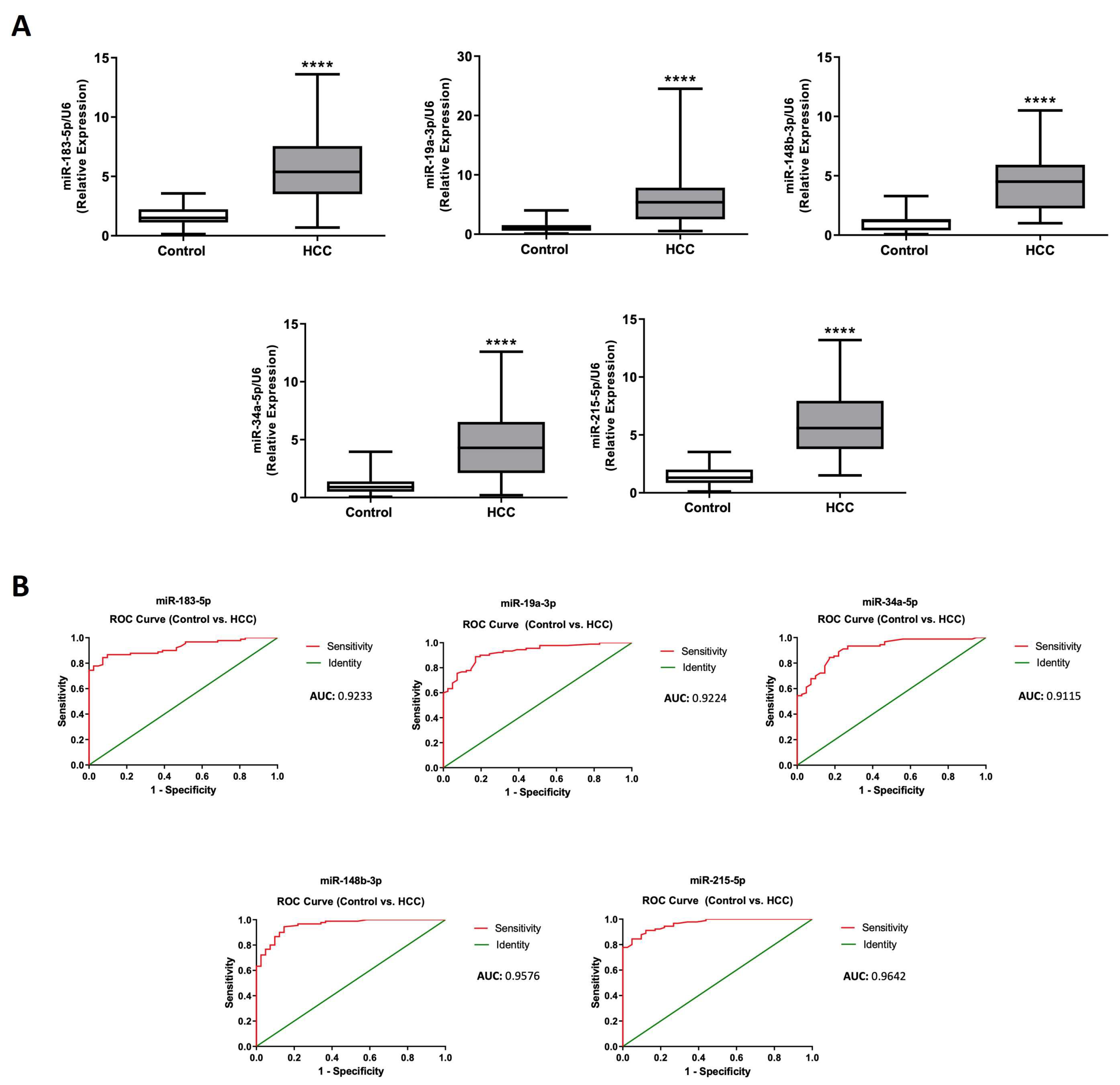

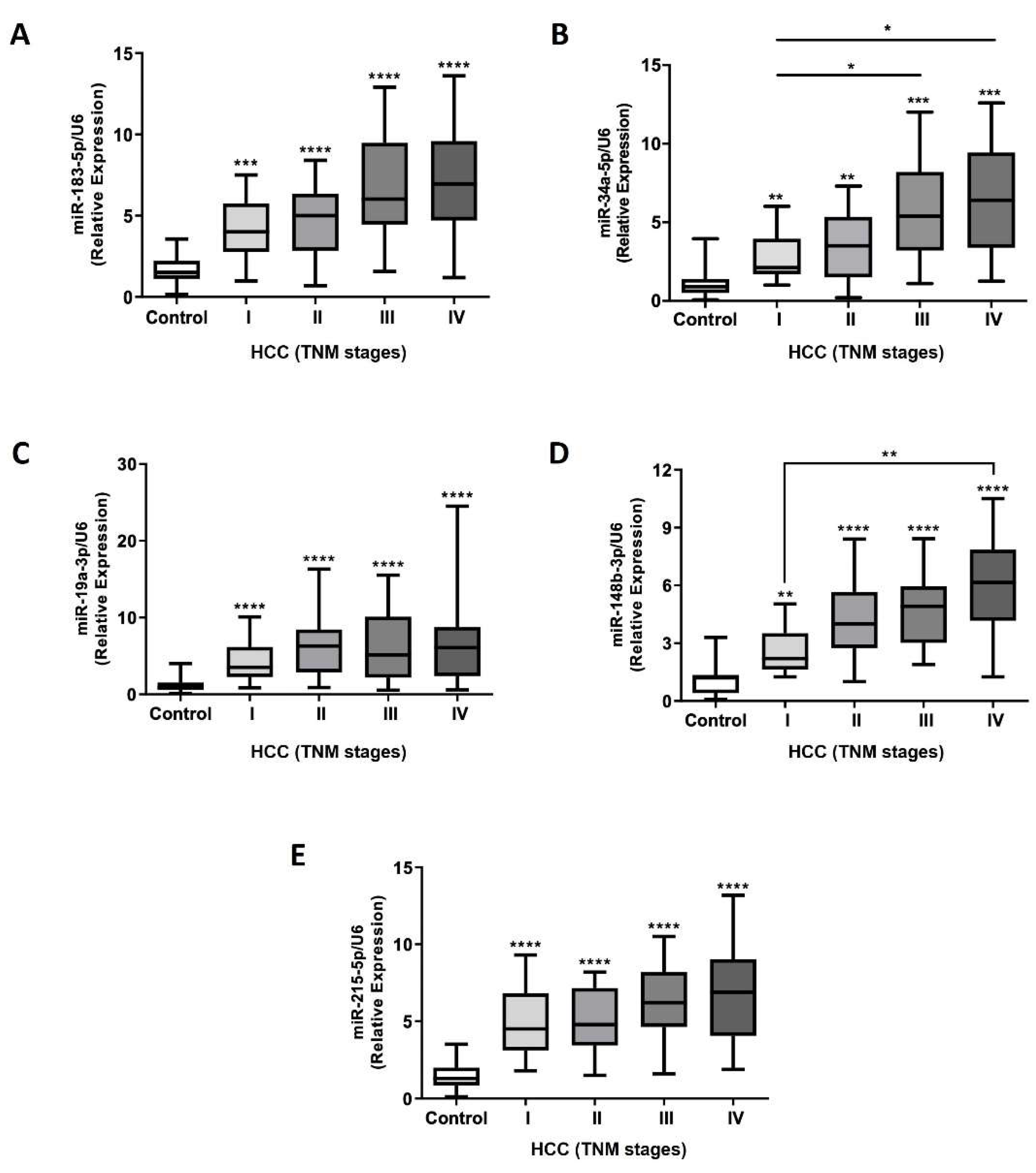

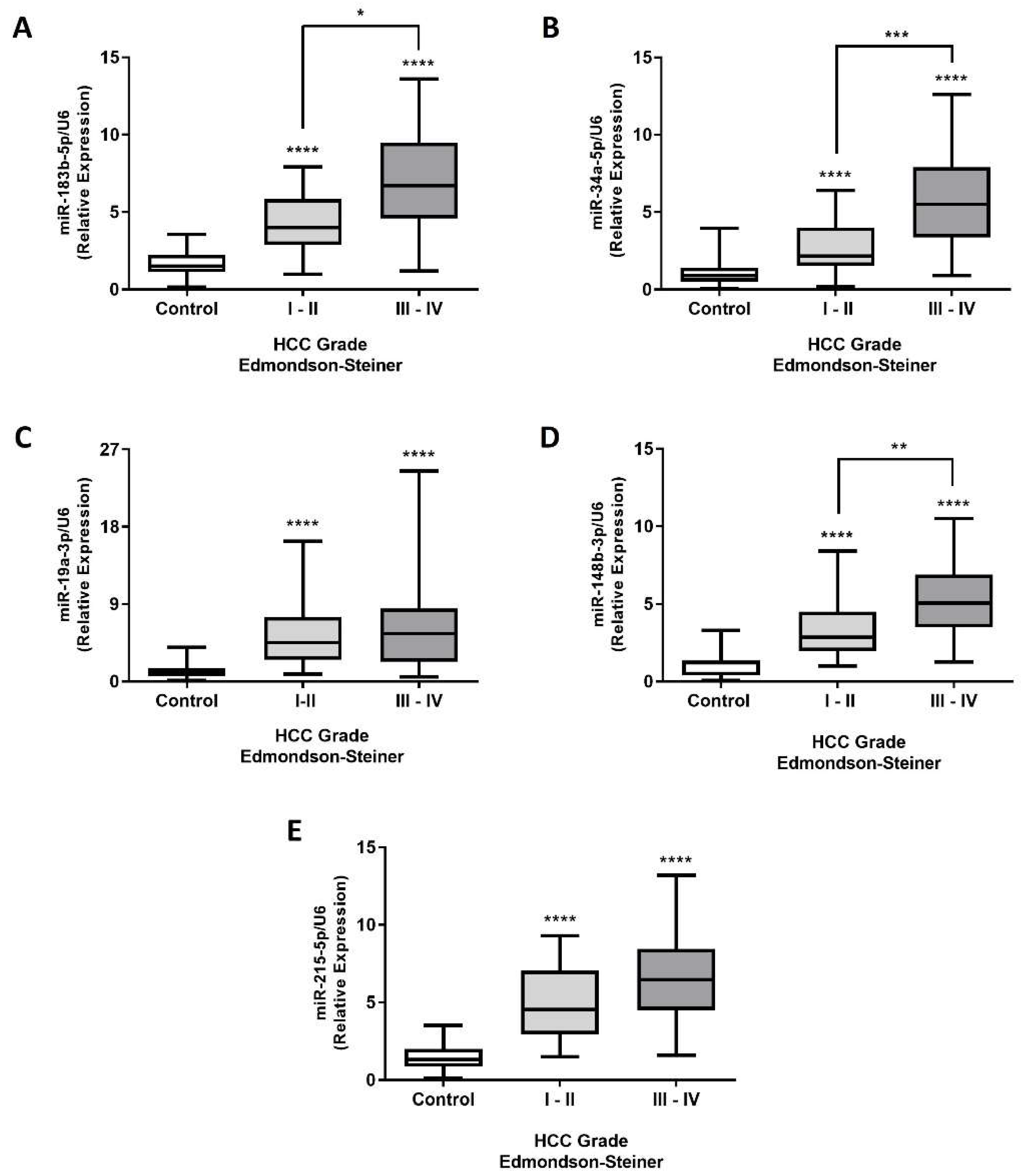

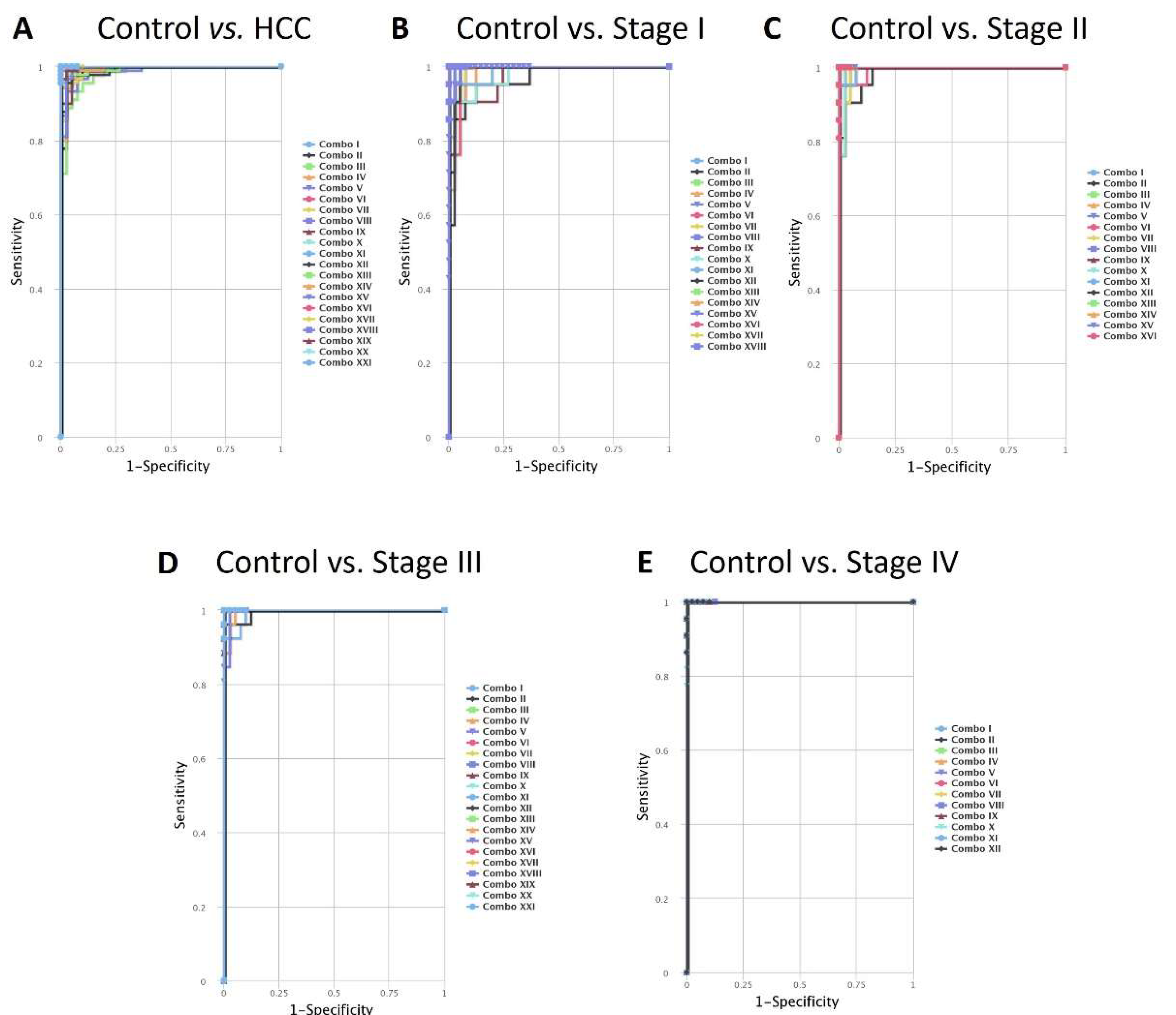

Hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) is the most common liver cancer, often diagnosed at advanced stages due to inadequate early diagnostic methods. MicroRNAs (miRNAs) play crucial roles in gene expression regulation and are possible biomarkers for molecular diagnosis in several diseases, including cancer. This study aimed to investigate the diagnostic potential of miRNAs contained in Extracellular Vesicles (EVs) from HCC. The miRNA expression contained in EVs was analyzed in HCC cell lines, circulating EVs in a Diethylnitrosamine (DEN)-induced HCC rat model, and plasma samples of HCC patients. Receiver Operating Characteristics (ROC) were applied to circulating EV-miRNAs from human patients to evaluate their diagnostic accuracy. The miRNA expression analysis identified five miRNAs (miR-183-5p, miR-19a-3p, miR-148b-3p, miR-34a-5p, and miR-215-5p) consistently up-regulated in EVs from in vitro and in vivo HCC models. These five EVs-derived miRNAs showed statistically significant differences in HCC patients stratified by TNM staging and Edmondson-Steiner grading compared to healthy controls. Individually and in combination, they demonstrated high sensitivity, specificity, and accuracy in distinguishing HCC patients from healthy subjects. The consistent upregulation of the five miRNAs across different experimental models and clinical samples suggests their robustness as biomarkers for HCC diagnosis, and it underscores their clinical potential in early disease management and prognosis.

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Results

2.1. Isolation and Characterization of EVs Secreted by HCC Cell Lines

2.5. Efficacy Validation of miRNA-Contained in Plasma Circulating EVs as Diagnostic Biomarkers of HCC

3. Discussion

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Cell Culture

4.2. Isolation of Extracellular Vesicles

4.3. Hepatocellular Carcinoma-induced Rat Model

4.4. Human Patients Sample Collection

4.5. Data Analysis

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

| Group | miRNA | Cut-off value | Sensitivity (%) | Specificity (%) | Accuracy(%) | Youden´s index (J) |

| Control vs. HCC | miR-183-5p | 2.614 | 84.44 | 92.68 | 88.56 | 0.7712 |

| miR-19a-3p | 1.801 | 88.89 | 82.93 | 85.91 | 0.7182 | |

| miR-148b-3p | 1.515 | 94.44 | 85.37 | 89.90 | 0.7981 | |

| miR-34a-5p | 1.810 | 84.44 | 82.93 | 83.68 | 0.6737 | |

| miR-215-5p | 3.163 | 84.44 | 95.12 | 89.78 | 0.7956 | |

| Control vs. Stage I | miR-183-5p | 2.495 | 80.95 | 90.24 | 85.59 | 0.7119 |

| miR-19a-3p | 1.801 | 90.48 | 82.93 | 86.70 | 0.7341 | |

| miR-148b-3p | 1.515 | 90.48 | 85.37 | 87.92 | 0.7585 | |

| miR-34a-5p | 1.510 | 90.48 | 78.05 | 84.24 | 0.6853 | |

| miR-215-5p | 2.833 | 85.71 | 90.24 | 87.97 | 0.7595 | |

| Control vs. Stage II | miR-183-5p | 2.480 | 85.71 | 90.24 | 87.97 | 0.7595 |

| miR-19a-3p | 2.700 | 80.95 | 92.68 | 86.81 | 0.7363 | |

| miR-148b-3p | 1.982 | 95.24 | 90.24 | 92.74 | 0.8548 | |

| miR-34a-5p | 1.400 | 80.95 | 75.61 | 78.28 | 0.5656 | |

| miR-215-5p | 3.213 | 80.95 | 95.12 | 88.03 | 0.7607 | |

| Control vs. Stage III | miR-183-5p | 3.457 | 88.46 | 97.56 | 93.01 | 0.8602 |

| miR-19a-3p | 1.635 | 88.46 | 80.49 | 84.47 | 0.6895 | |

| miR-148b-3p | 1.982 | 96.15 | 90.24 | 93.19 | 0.8639 | |

| miR-34a-5p | 2.582 | 88.46 | 92.68 | 90.57 | 0.8114 | |

| miR-215-5p | 3.163 | 92.31 | 95.12 | 94.21 | 0.8743 | |

| Control vs. Stage IV | miR-183-5p | 3.457 | 86.36 | 97.56 | 91.96 | 0.8392 |

| miR-19a-3p | 1.873 | 90.91 | 82.93 | 86.92 | 0.7384 | |

| miR-148b-3p | 3.010 | 86.36 | 97.56 | 91.96 | 0.8392 | |

| miR-34a-5p | 2.582 | 86.36 | 92.68 | 89.52 | 0.7904 | |

| miR-215-5p | 2.669 | 95.45 | 87.80 | 91.62 | 0.8325 |

| Group | miRNA | LR+ | LR- | AUC | SE | 95% CI | p-value |

| Control vs. HCC | miR-183-5p | 11.535 | 0.167 | 0.9233 | 0.02232 | 0.879-0.967 | <0.0001 |

| miR-19a-3p | 5.207 | 0.133 | 0.9224 | 0.02281 | 0.877-0.967 | <0.0001 | |

| miR-148b-3p | 6.455 | 0.065 | 0.9576 | 0.01604 | 0.926-0.989 | <0.0001 | |

| miR-34a-5p | 4.946 | 0.187 | 0.9115 | 0.02537 | 0.861-0.961 | <0.0001 | |

| miR-215-5p | 17.303 | 0.163 | 0.9642 | 0.01328 | 0.938-0.990 | <0.0001 | |

| Control vs. Stage I | miR-183-5p | 8.294 | 0.211 | 0.8827 | 0.05029 | 0.784-0.981 | <0.0001 |

| miR-19a-3p | 5.300 | 0.114 | 0.9199 | 0.03475 | 0.851-0.988 | <0.0001 | |

| miR-148b-3p | 6.184 | 0.111 | 0.9181 | 0.03396 | 0.851-0.984 | <0.0001 | |

| miR-34a-5p | 4.122 | 0.121 | 0.8705 | 0.04410 | 0.784-0.957 | <0.0001 | |

| miR-215-5p | 8.781 | 0.158 | 0.9506 | 0.02526 | 0.901-1.000 | <0.0001 | |

| Control vs. Stage II | miR-183-5p | 8.781 | 0.158 | 0.8995 | 0.04988 | 0.801-0.997 | <0.0001 |

| miR-19a-3p | 11.058 | 0.205 | 0.9274 | 0.03496 | 0.858-0.995 | <0.0001 | |

| miR-148b-3p | 9.758 | 0.052 | 0.9559 | 0.02877 | 0.899-1.000 | <0.0001 | |

| miR-34a-5p | 3.318 | 0.251 | 0.8339 | 0.05851 | 0.719-0.948 | <0.0001 | |

| miR-215-5p | 16.588 | 0.200 | 0.9547 | 0.02591 | 0.903-1.000 | <0.0001 | |

| Control vs. Stage III | miR-183-5p | 36.254 | 0.118 | 0.9587 | 0.02505 | 0.909-1.000 | <0.0001 |

| miR-19a-3p | 4.534 | 0.143 | 0.9203 | 0.03738 | 0.847-0.993 | <0.0001 | |

| miR-148b-3p | 9.851 | 0.042 | 0.9822 | 0.01154 | 0.959-1.000 | <0.0001 | |

| miR-34a-5p | 12.084 | 0.124 | 0.9601 | 0.02177 | 0.917-1.000 | <0.0001 | |

| miR-215-5p | 18.915 | 0.080 | 0.9737 | 0.01801 | 0.938-1.000 | <0.0001 | |

| Control vs. Stage IV | miR-183-5p | 35.393 | 0.139 | 0.9429 | 0.03764 | 0.869-1.000 | <0.0001 |

| miR-19a-3p | 5.325 | 0.109 | 0.9224 | 0.03873 | 0.846-0.998 | <0.0001 | |

| miR-148b-3p | 35.393 | 0.139 | 0.9678 | 0.02057 | 0.927-1.000 | <0.0001 | |

| miR-34a-5p | 11.797 | 0.147 | 0.9673 | 0.01856 | 0.930-1.000 | <0.0001 | |

| miR-215-5p | 7.823 | 0.051 | 0.9751 | 0.01619 | 0.943-1.000 | <0.0001 |

| Group | miRNA | Cut-off value | Sensitivity (%) | Specificity (%) | Accuracy (%) | Youden's index (J) |

| Control vs I - II | miR-183-5p | 2.48 | 82.35 | 90.24 | 86.67 | 0.7259 |

| miR-19a-3p | 2.515 | 79.41 | 92.68 | 86.67 | 0.7209 | |

| miR-148b-3p | 1.515 | 91.18 | 85.37 | 88.00 | 0.7655 | |

| miR-34a-5p | 1.24 | 88.24 | 73.17 | 80.00 | 0.6141 | |

| miR-215-5p | 2.833 | 82.35 | 90.24 | 86.67 | 0.7259 | |

| Control vs III- IV | miR-183-5p | 3.582 | 87.5 | 100 | 93.26 | 0.875 |

| miR-19a-3p | 1.801 | 89.29 | 82.93 | 86.60 | 0.7222 | |

| miR-148b-3p | 1.982 | 92.86 | 90.24 | 91.75 | 0.831 | |

| miR-34a-5p | 2.582 | 85.96 | 92.68 | 88.78 | 0.7864 | |

| miR-215-5p | 3.163 | 89.58 | 95.12 | 92.13 | 0.847 |

| Group | miRNA | LR + | LR - | AUC | SE | 95% CI | p-value |

| Control vs I - II | miR-183-5p | 8.44 | 0.12 | 0.892 | 0.03877 | 0.8161 - 0.9680 | <0.0001 |

| miR-19a-3p | 10.85 | 0.09 | 0.9186 | 0.03082 | 0.8582 - 0.9790 | <0.0001 | |

| miR-148b-3p | 6.23 | 0.16 | 0.9258 | 0.02952 | 0.8679 - 0.9836 | <0.0001 | |

| miR-34a-5p | 3.29 | 0.30 | 0.8375 | 0.04707 | 0.7453 - 0.9298 | <0.0001 | |

| miR-215-5p | 8.44 | 0.12 | 0.9426 | 0.02386 | 0.8958 - 0.9894 | <0.0001 | |

| Control vs III- IV | miR-183-5p | 87.50 | 0.00 | 0.9515 | 0.02246 | 0.9074 - 0.9955 | <0.0001 |

| miR-19a-3p | 5.23 | 0.19 | 0.9247 | 0.02624 | 0.8732 - 0.9761 | <0.0001 | |

| miR-148b-3p | 9.51 | 0.11 | 0.9769 | 0.01139 | 0.9546 - 0.9992 | <0.0001 | |

| miR-34a-5p | 11.74 | 0.09 | 0.9572 | 0.01746 | 0.9230 - 0.9914 | <0.0001 | |

| miR-215-5p | 18.36 | 0.05 | 0.9743 | 0.01323 | 0.9484 - 1.000 | <0.0001 |

References

- Farazi, P.A.; DePinho, R.A. Hepatocellular Carcinoma Pathogenesis: From Genes to Environment. Nat Rev Cancer 2006, 6, 674–687. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Forner, A.; Reig, M.; Bruix, J. Hepatocellular Carcinoma. The Lancet 2018, 391, 1301–1314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bray, F.; Laversanne, M.; Sung, H.; Ferlay, J.; Siegel, R.L.; Soerjomataram, I.; Jemal, A. Global Cancer Statistics 2022: GLOBOCAN Estimates of Incidence and Mortality Worldwide for 36 Cancers in 185 Countries. CA Cancer J Clin 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, W.; Wei, C. Advances in the Early Diagnosis of Hepatocellular Carcinoma. Genes Dis 2020, 7, 308–319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rao, A.; Rich, N.E.; Marrero, J.A.; Yopp, A.C.; Singal, A.G. Diagnostic and Therapeutic Delays in Patients with Hepatocellular Carcinoma. JNCCN Journal of the National Comprehensive Cancer Network 2021, 19, 1063–1071. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bruix, J.; Sherman, M. Management of Hepatocellular Carcinoma: An Update. Hepatology 2011, 53, 1020–1022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Di Tommaso, L.; Spadaccini, M.; Donadon, M.; Personeni, N.; Elamin, A.; Aghemo, A.; Lleo, A. Role of Liver Biopsy in Hepatocellular Carcinoma. World J Gastroenterol 2019, 25, 6041–6052. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Forner, A.; Vilana, R.; Ayuso, C.; Bianchi, L.; Solé, M.; Ayuso, J.R.; Boix, L.; Sala, M.; Varela, M.; Llovet, J.M.; et al. Diagnosis of Hepatic Nodules 20 Mm or Smaller in Cirrhosis: Prospective Validation of the Noninvasive Diagnostic Criteria for Hepatocellular Carcinoma. Hepatology 2008, 47, 97–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dimitroulis, D.; Damaskos, C.; Valsami, S.; Davakis, S.; Garmpis, N.; Spartalis, E.; Athanasiou, A.; Moris, D.; Sakellariou, S.; Kykalos, S.; et al. From Diagnosis to Treatment of Hepatocellular Carcinoma: An Epidemic Problem for Both Developed and Developing World. World J Gastroenterol 2017, 23, 5282–5294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Villanueva, A. Hepatocellular Carcinoma. New England Journal of Medicine 2019, 380, 1450–1462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Debes, J.D.; Romagnoli, P.A.; Prieto, J.; Arrese, M.; Mattos, A.Z.; Boonstra, A. Serum Biomarkers for the Prediction of Hepatocellular Carcinoma. Cancers (Basel) 2021, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Beudeker, B.J.B.; Boonstra, A. Circulating Biomarkers for Early Detection of Hepatocellular Carcinoma. Therap Adv Gastroenterol 2020, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Van Niel, G.; D’Angelo, G.; Raposo, G. Shedding Light on the Cell Biology of Extracellular Vesicles. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol 2018, 19, 213–228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Latifkar, A.; Cerione, R.A.; Antonyak, M.A. Probing the Mechanisms of Extracellular Vesicle Biogenesis and Function in Cancer. Biochem Soc Trans 2018, 46, 1137–1146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, S.; Gregory, R.I. MicroRNA Biogenesis Pathways in Cancer. Nat Rev Cancer 2015, 15, 321–333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bronte, F.; Bronte, G.; Fanale, D.; Caruso, S.; Bronte, E.; Bavetta, M.G.; Fiorentino, E.; Rolfo, C.; Bazan, V.; Marco, V. Di; et al. HepatomiRNoma: The Proposal of a New Network of Targets for Diagnosis, Prognosis and Therapy in Hepatocellular Carcinoma. Crit Rev Oncol Hematol 2016, 97, 312–321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Corsini, L.R.; Bronte, G.; Terrasi, M.; Amodeo, V.; Fanale, D.; Fiorentino, E.; Cicero, G.; Bazan, V.; Russo, A. The Role of MicroRNAs in Cancer: Diagnostic and Prognostic Biomarkers and Targets of Therapies. Expert Opin Ther Targets 2012, 16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, N.; Ekanem, N.R.; Sakyi, C.A.; Ray, S.D. Hepatocellular Carcinoma and MicroRNA: New Perspectives on Therapeutics and Diagnostics. Adv Drug Deliv Rev 2015, 81, 62–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jansson, M.D.; Lund, A.H. MicroRNA and Cancer. Mol Oncol 2012, 6, 590–610. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thurnherr, T.; Mah, W.C.; Lei, Z.; Jin, Y.; Rozen, S.G.; Lee, C.G. Differentially Expressed MiRNAs in Hepatocellular Carcinoma Target Genes in the Genetic Information Processing and Metabolism Pathways. Sci Rep 2016, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, W.H.; Cerione, R.A.; Antonyak, M.A. Extracellular Vesicles and Their Roles in Cancer Progression. Methods in Molecular Biology 2021, 2174, 143–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Théry, C.; Witwer, K.W.; Aikawa, E.; Alcaraz, M.J.; Anderson, J.D.; Andriantsitohaina, R.; Antoniou, A.; Arab, T.; Archer, F.; Atkin-Smith, G.K.; et al. Minimal Information for Studies of Extracellular Vesicles 2018 (MISEV2018): A Position Statement of the International Society for Extracellular Vesicles and Update of the MISEV2014 Guidelines. J Extracell Vesicles 2018, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Berardocco, M.; Radeghieri, A.; Busatto, S.; Gallorini, M.; Raggi, C.; Gissi, C.; D’Agnano, I.; Bergese, P.; Felsani, A.; Berardi, A.C. RNA-Seq Reveals Distinctive RNA Profiles of Small Extracellular Vesicles from Different Human Liver Cancer Cell Lines. Oncotarget 2017, 8, 82920–82939. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Colombo, M.; Moita, C.; Van Niel, G.; Kowal, J.; Vigneron, J.; Benaroch, P.; Manel, N.; Moita, L.F.; Théry, C.; Raposo, G. Analysis of ESCRT Functions in Exosome Biogenesis, Composition and Secretion Highlights the Heterogeneity of Extracellular Vesicles. J Cell Sci 2013, 126, 5553–5565. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kogure, T.; Lin, W.L.; Yan, I.K.; Braconi, C.; Patel, T. Intercellular Nanovesicle-Mediated MicroRNA Transfer: A Mechanism of Environmental Modulation of Hepatocellular Cancer Cell Growth. Hepatology 2011, 54, 1237–1248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hurwitz, S.N.; Rider, M.A.; Bundy, J.L.; Liu, X.; Singh, R.K.; Meckes, D.G. Proteomic Profiling of NCI-60 Extracellular Vesicles Uncovers Common Protein Cargo and Cancer Type-Specific Biomarkers; 2016; Vol. 7;

- Wu, Z.; Zeng, Q.; Cao, K.; Sun, Y. Exosomes: Small Vesicles with Big Roles in Hepatocellular Carcinoma. Oncotarget 2016, 7, 60687–60697. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Li, S.; Li, L.; Li, M.; Guo, C.; Yao, J.; Mi, S. Exosome and Exosomal MicroRNA: Trafficking, Sorting, and Function. Genomics Proteomics Bioinformatics 2015, 13, 17–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valadi, H.; Ekström, K.; Bossios, A.; Sjöstrand, M.; Lee, J.J.; Lötvall, J.O. Exosome-Mediated Transfer of MRNAs and MicroRNAs Is a Novel Mechanism of Genetic Exchange between Cells. Nat Cell Biol 2007, 9, 654–659. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, J.; Flores-Bellver, M.; Pan, J.; Benito-Martin, A.; Shi, C.; Onwumere, O.; Mighty, J.; Qian, J.; Zhong, X.; Hogue, T.; et al. Human Retinal Organoids Release Extracellular Vesicles That Regulate Gene Expression in Target Human Retinal Progenitor Cells. Sci Rep 2021, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mills, J.; Capece, M.; Cocucci, E.; Tessari, A.; Palmieri, D. Cancer-Derived Extracellular Vesicle-Associated MicroRNAs in Intercellular Communication: One Cell’s Trash Is Another Cell’s Treasure. Int J Mol Sci 2019, 20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Colombo, M.; Raposo, G.; Théry, C. Biogenesis, Secretion, and Intercellular Interactions of Exosomes and Other Extracellular Vesicles. Annu Rev Cell Dev Biol 2014, 30, 255–289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, D.; Woo, H.K.; Lee, C.; Min, Y.; Kumar, S.; Sunkara, V.; Jo, H.G.; Lee, Y.J.; Kim, J.; Ha, H.K.; et al. EV-Ident: Identifying Tumor-Specific Extracellular Vesicles by Size Fractionation and Single-Vesicle Analysis. Anal Chem 2020, 92, 6010–6018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Berezin, A.E.; Berezin, A.A. Endothelial Cell-Derived Extracellular Vesicles in Atherosclerosis: The Emerging Value for Diagnosis, Risk Stratification and Prognostication. Vessel Plus 2020, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, R.; Greening, D.W.; Rai, A.; Ji, H.; Simpson, R.J. Highly-Purified Exosomes and Shed Microvesicles Isolated from the Human Colon Cancer Cell Line LIM1863 by Sequential Centrifugal Ultrafiltration Are Biochemically and Functionally Distinct. Methods 2015, 87, 11–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soltész, B.; Buglyó, G.; Németh, N.; Szilágyi, M.; Pös, O.; Szemes, T.; Balogh, I.; Nagy, B. The Role of Exosomes in Cancer Progression. Int J Mol Sci 2022, 23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Basu, S.; Bhattacharyya, S.N. Insulin-like Growth Factor-1 Prevents MiR-122 Production in Neighbouring Cells to Curtail Its Intercellular Transfer to Ensure Proliferation of Human Hepatoma Cells. Nucleic Acids Res 2014, 42, 7170–7185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Lu, L.L.; Wen, D.; Liu, D.L.; Dong, L.L.; Gao, D.M.; Bian, X.Y.; Zhou, J.; Fan, J.; Wu, W.Z. MiR-612 Regulates Invadopodia of Hepatocellular Carcinoma by HADHA-Mediated Lipid Reprogramming. J Hematol Oncol 2020, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chiba, M.; Kimura, M.; Asari, S. Exosomes Secreted from Human Colorectal Cancer Cell Lines Contain MRNAs, MicroRNAs and Natural Antisense RNAs, That Can Transfer into the Human Hepatoma HepG2 and Lung Cancer A549 Cell Lines. Oncol Rep 2012, 28, 1551–1558. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pan, Q.; Ramakrishnaiah, V.; Henry, S.; Fouraschen, S.; De Ruiter, P.E.; Kwekkeboom, J.; Tilanus, H.W.; Janssen, H.L.A.; Van Der Laan, L.J.W. Hepatic Cell-to-Cell Transmission of Small Silencing RNA Can Extend the Therapeutic Reach of RNA Interference (RNAi). Gut 2012, 61, 1330–1339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Okoye, I.S.; Coomes, S.M.; Pelly, V.S.; Czieso, S.; Papayannopoulos, V.; Tolmachova, T.; Seabra, M.C.; Wilson, M.S. MicroRNA-Containing T-Regulatory-Cell-Derived Exosomes Suppress Pathogenic T Helper 1 Cells. Immunity 2014, 41, 89–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sorop, A.; Constantinescu, D.; Cojocaru, F.; Dinischiotu, A.; Cucu, D.; Dima, S.O. Exosomal MicroRNAs as Biomarkers and Therapeutic Targets for Hepatocellular Carcinoma. Int J Mol Sci 2021, 22, 4997. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nakano, T.; Chen, I.H.; Wang, C.C.; Chen, P.J.; Tseng, H.P.; Huang, K.T.; Hu, T.H.; Li, L.C.; Goto, S.; Cheng, Y.F.; et al. Circulating Exosomal MiR-92b: Its Role for Cancer Immunoediting and Clinical Value for Prediction of Posttransplant Hepatocellular Carcinoma Recurrence. American Journal of Transplantation 2019, 19, 3250–3262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cui, Y.; Xu, H.F.; Liu, M.Y.; Xu, Y.J.; He, J.C.; Zhou, Y.; Cang, S.D. Mechanism of Exosomal MicroRNA-224 in Development of Hepatocellular Carcinoma and Its Diagnostic and Prognostic Value. World J Gastroenterol 2019, 25, 1890–1898. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qu, Z.; Wu, J.; Wu, J.; Ji, A.; Qiang, G.; Jiang, Y.; Jiang, C.; Ding, Y. Exosomal MiR-665 as a Novel Minimally Invasive Biomarker for Hepatocellular Carcinoma Diagnosis and Prognosis; 2017; Vol. 8;

- Shi, M.; Jiang, Y.; Yang, L.; Yan, S.; Wang, Y.G.; Lu, X.J. Decreased Levels of Serum Exosomal MiR-638 Predict Poor Prognosis in Hepatocellular Carcinoma. J Cell Biochem 2018, 119, 4711–4716. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suehiro, T.; Miyaaki, H.; Kanda, Y.; Shibata, H.; Honda, T.; Ozawa, E.; Miuma, S.; Taura, N.; Nakao, K. Serum Exosomal MicroRNA-122 and MicroRNA-21 as Predictive Biomarkers in Transarterial Chemoembolization-Treatedhepatocellular Carcinoma Patients. Oncol Lett 2018, 16, 3267–3273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cho, H.J.; Eun, J.W.; Baek, G.O.; Seo, C.W.; Ahn, H.R.; Kim, S.S.; Cho, S.W.; Cheong, J.Y. Serum Exosomal MicroRNA, MiR-10b-5p, as a Potential Diagnostic Biomarker for Early-Stage Hepatocellular Carcinoma. J Clin Med 2020, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, S.; Mao, Y.; Chen, W.; Liu, C.; Wu, H.; Zhang, J.; Wang, S.; Wang, C.; Lin, Y.; Lv, Y. Serum Exosomal MiR-34a as a Potential Biomarker for the Diagnosis and Prognostic of Hepatocellular Carcinoma. J Cancer 2022, 13, 1410–1417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, H.; Zhang, Z. Diagnostic Value of a MicroRNA Signature Panel in Exosomes for Patients with Hepatocellular Carcinoma; 2019; Vol. 12;

- Xue, X.; Zhao, Y.; Wang, X.; Qin, L.; Hu, R. Development and Validation of Serum Exosomal MicroRNAs as Diagnostic and Prognostic Biomarkers for Hepatocellular Carcinoma. J Cell Biochem 2019, 120, 135–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ning, S.; Liu, H.; Gao, B.; Wei, W.; Yang, A.; Li, J.; Zhang, L. MiR-155, MiR-96 and MiR-99a as Potential Diagnostic and Prognostic Tools for the Clinical Management of Hepatocellular Carcinoma. Oncol Lett 2019, 18, 3381–3387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gharib, A.F.; Eed, E.M.; Khalifa, A.S.; Raafat, N.; Shehab-Eldeen, S.; Alwakeel, H.R.; Darwiesh, E.; Essa, A. Value of Serum MiRNA-96-5p and MiRNA-99a-5p as Diagnostic Biomarkers for Hepatocellular Carcinoma. Int J Gen Med 2022, 15, 2427–2436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qian, F.; Wang, J.; Wang, Y.; Gao, Q.; Yan, W.; Lin, Y.; Shen, L.; Xie, Y.; Jiang, X.; Shen, B. MiR-378a-3p as a Putative Biomarker for Hepatocellular Carcinoma Diagnosis and Prognosis: Computational Screening with Experimental Validation. Clin Transl Med 2021, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Edge, S.B. . AJCC Cancer Staging Manual; Springer, 2010; ISBN 9780387884400.

- Wu, J.-C.; Huang, Y.; Chen, C.; Chang, T.; Chen, S.; Wang, S.; Lee, H.; Lin, P.; Huang, G.; Sheu, J.; et al. Evaluation of Predictive Value of CLIP, Okuda, TNM and JIS Staging Systems for Hepatocellular Carcinoma Patients Undergoing Surgery. J Gastroenterol Hepatol 2005, 20, 765–771. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pu, C.; Huang, H.; Wang, Z.; Zou, W.; Lv, Y.; Zhou, Z.; Zhang, Q.; Qiao, L.; Wu, F.; Shao, S. Extracellular Vesicle-Associated Mir-21 and Mir-144 Are Markedly Elevated in Serum of Patients with Hepatocellular Carcinoma. Front Physiol 2018, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sorop, A.; Iacob, R.; Iacob, S.; Constantinescu, D.; Chitoiu, L.; Fertig, T.E.; Dinischiotu, A.; Chivu-Economescu, M.; Bacalbasa, N.; Savu, L.; et al. Plasma Small Extracellular Vesicles Derived MiR-21-5p and MiR-92a-3p as Potential Biomarkers for Hepatocellular Carcinoma Screening. Front Genet 2020, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eldosoky, M.A.; Hammad, R.; Elmadbouly, A.A.; Aglan, R.B.; Abdel-Hamid, S.G.; Alboraie, M.; Hassan, D.A.; Shaheen, M.A.; Rushdi, A.; Ahmed, R.M.; et al. Diagnostic Significance of Hsa-MiR-21-5p, Hsa-MiR-192-5p, Hsa-MiR-155-5p, Hsa-MiR-199a-5p Panel and Ratios in Hepatocellular Carcinoma on Top of Liver Cirrhosis in HCV-Infected Patients. Int J Mol Sci 2023, 24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ullmann, P.; Nurmik, M.; Schmitz, M.; Rodriguez, F.; Weiler, J.; Qureshi-Baig, K.; Felten, P.; Nazarov, P.V.; Nicot, N.; Zuegel, N.; et al. Tumor Suppressor MiR-215 Counteracts Hypoxia-Induced Colon Cancer Stem Cell Activity. Cancer Lett 2019, 450, 32–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vychytilova-Faltejskova, P.; Merhautova, J.; Machackova, T.; Gutierrez-Garcia, I.; Garcia-Solano, J.; Radova, L.; Brchnelova, D.; Slaba, K.; Svoboda, M.; Halamkova, J.; et al. MiR-215-5p Is a Tumor Suppressor in Colorectal Cancer Targeting EGFR Ligand Epiregulin and Its Transcriptional Inducer HOXB9. Oncogenesis 2017, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- White, N.M.A.; Khella, H.W.Z.; Grigull, J.; Adzovic, S.; Youssef, Y.M.; Honey, R.J.; Stewart, R.; Pace, K.T.; Bjarnason, G.A.; Jewett, M.A.S.; et al. MiRNA Profiling in Metastatic Renal Cell Carcinoma Reveals a Tumour-Suppressor Effect for MiR-215. Br J Cancer 2011, 105, 1741–1749. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yacoub, R.A.; Fawzy, I.O.; Assal, R.A.; Hosny, K.A.; Zekri, A.R.N.; Esmat, G.; El Tayebi, H.M.; Abdelaziz, A.I. MiR-34a: Multiple Opposing Targets and One Destiny in Hepatocellular Carcinoma. J Clin Transl Hepatol 2016, 4, 300–305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, G.; Qiu, J.; Liu, C.; Tian, B.; Cai, D.; Liu, S. MiR-148b-3p Regulates the Expression of DTYMK to Drive Hepatocellular Carcinoma Cell Proliferation and Metastasis. Front Oncol 2021, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, T.; Shi, C.; Xu, W.; Yang, H.-L.; Xia, B.; Tian, C. Extracellular Vesicles Derived from T-Cell Acute Lymphoblastic Leukemia Inhibit Osteogenic Differentiation of Bone Marrow Mesenchymal Stem Cells via MiR-34a-5p. Endocr J 2021, 68, 1197–1208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Luo, T.; Zhou, X.; Jiang, E.; Wang, L.; Ji, Y.; Shang, Z. Osteosarcoma Cell-Derived Small Extracellular Vesicles Enhance Osteoclastogenesis and Bone Resorption Through Transferring MicroRNA-19a-3p. Front Oncol 2021, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gerloff, D.; Kewitz-Hempel, S.; Hause, G.; Ehrenreich, J.; Golle, L.; Kingreen, T.; Sunderkötter, C. Comprehensive Analyses of MiRNAs Revealed MiR-92b-3p, MiR-182-5p and MiR-183-5p as Potential Novel Biomarkers in Melanoma-Derived Extracellular Vesicles. Front Oncol 2022, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ohkawa, H.; Ohishi, N.; Yagi, K. Assay for Lipid Peroxides in Animal Tissues by Thiobarbituric Acid Reaction. Anal Biochem 1979, 95, 351–358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cohen, J.F.; Korevaar, D.A.; Altman, D.G.; Bruns, D.E.; Gatsonis, C.A.; Hooft, L.; Irwig, L.; Levine, D.; Reitsma, J.B.; de Vet, H.C.W.; et al. STARD 2015 Guidelines for Reporting Diagnostic Accuracy Studies: Explanation and Elaboration. BMJ Open 2016, 6, e012799. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).