Submitted:

27 April 2023

Posted:

28 April 2023

Read the latest preprint version here

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

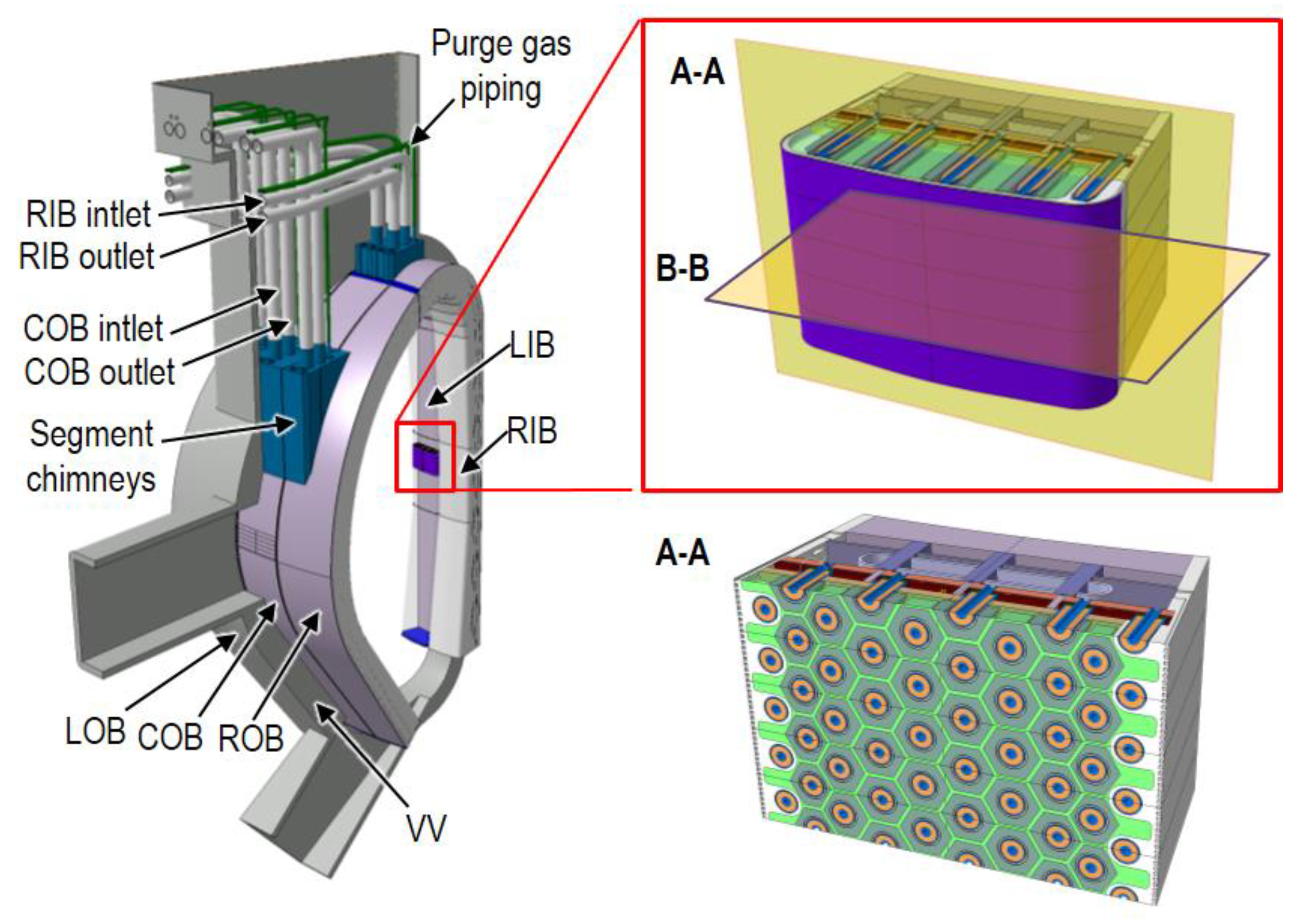

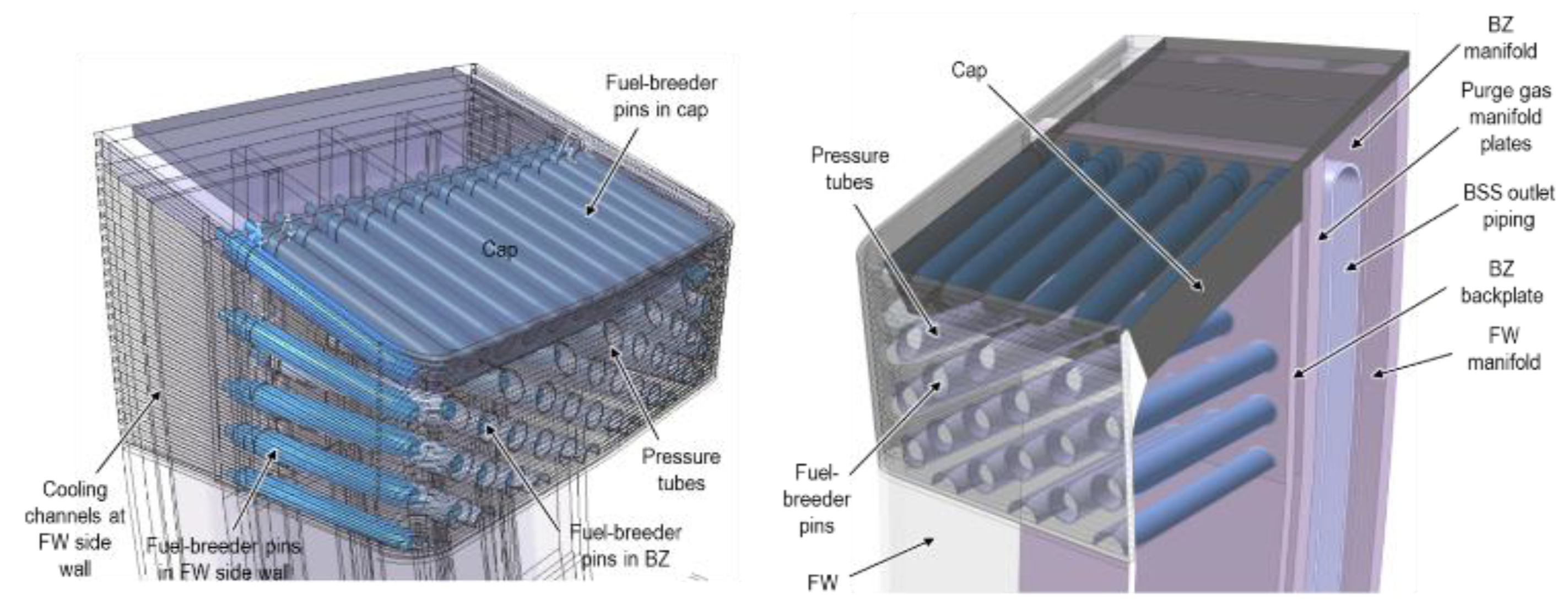

2. Design description of HCPB breeding blanket

2.1. Design evolution

2.2. Layout at end of PCD phase

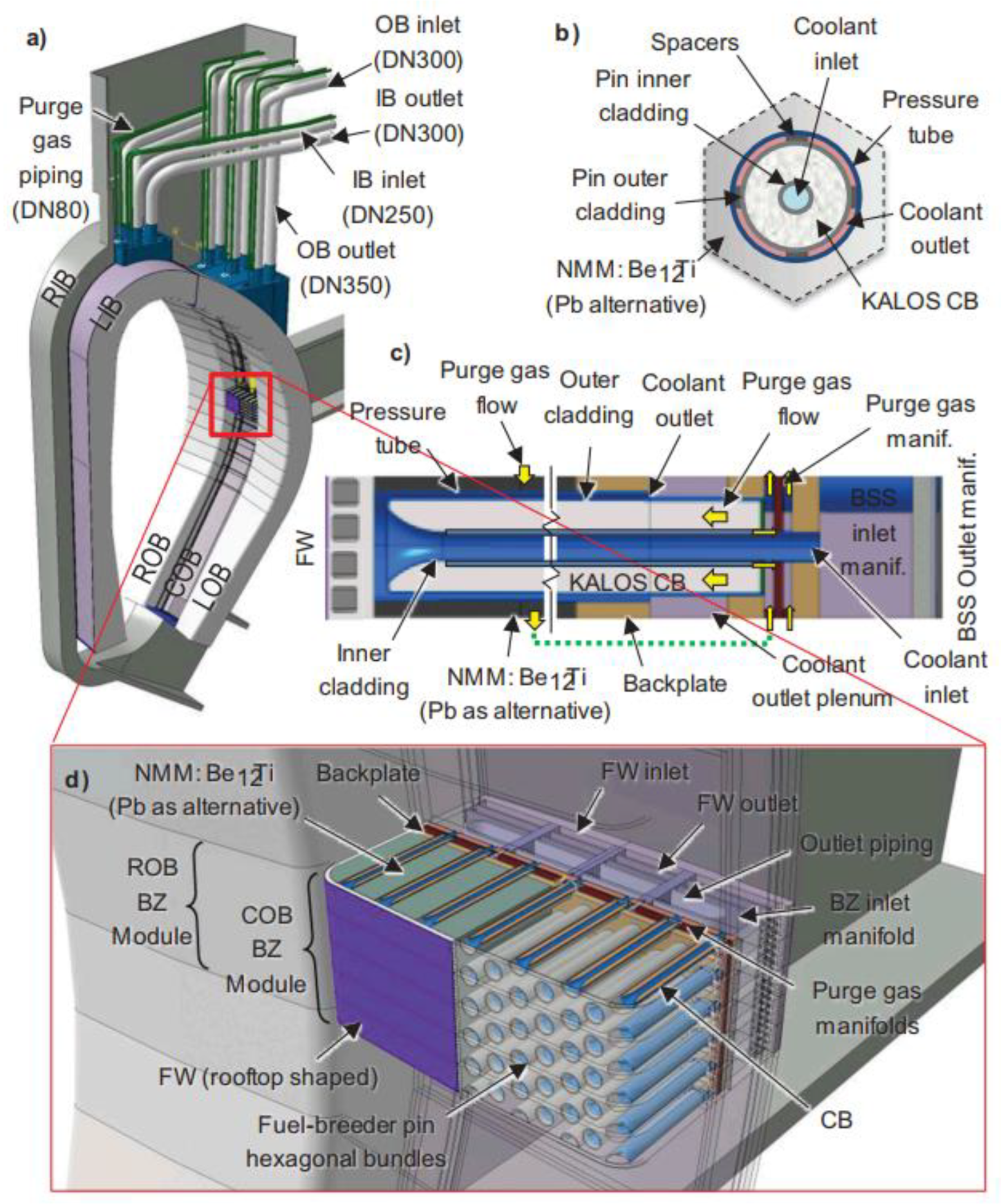

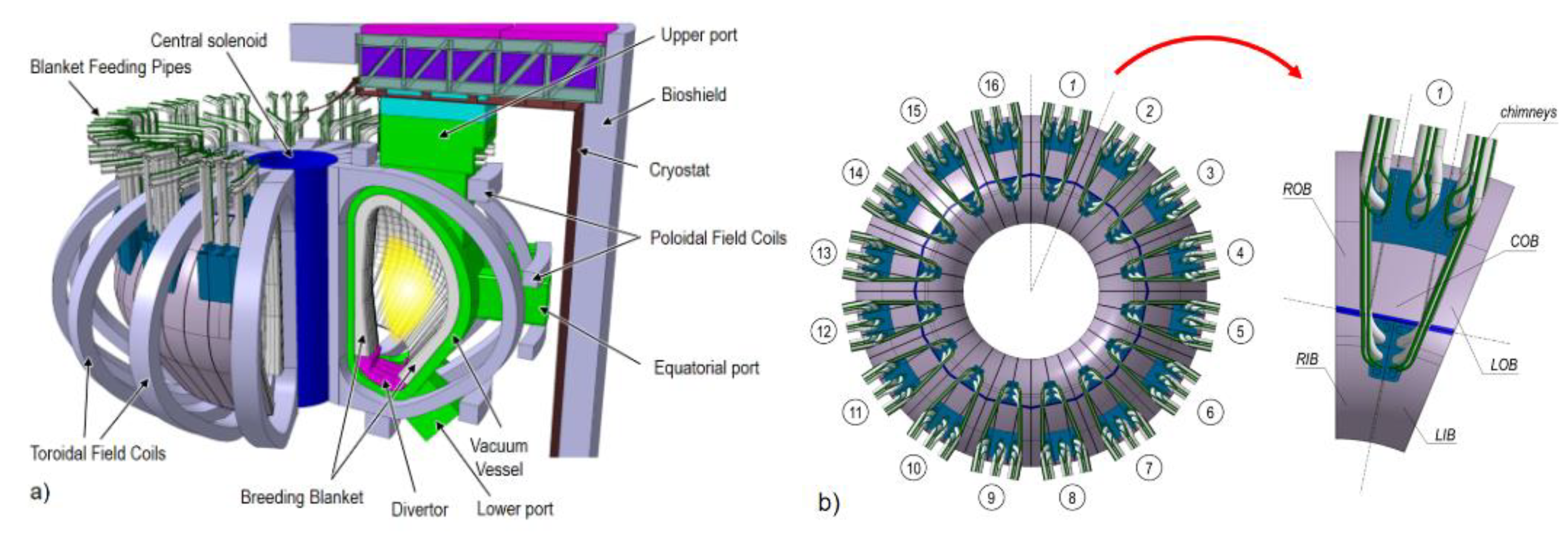

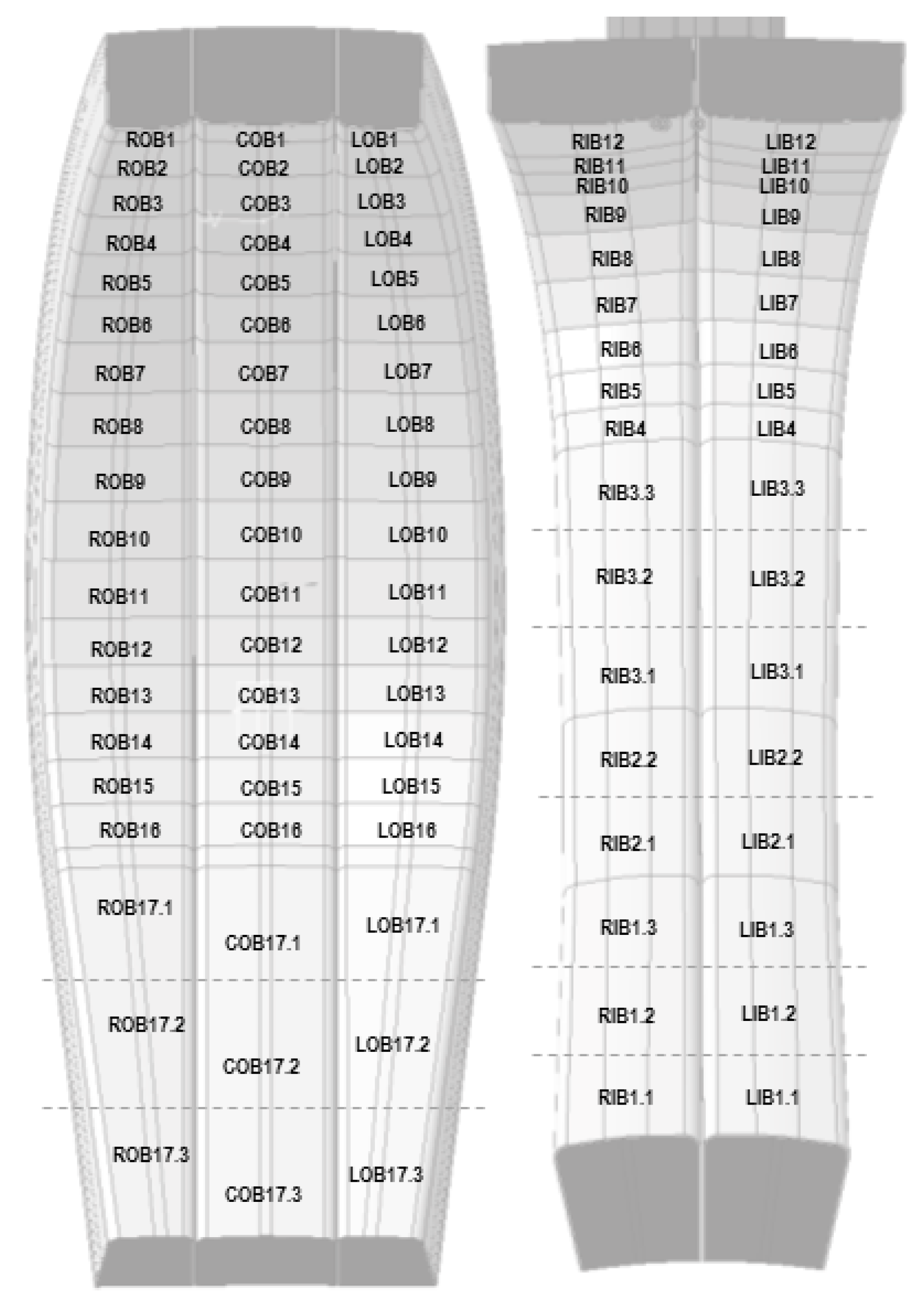

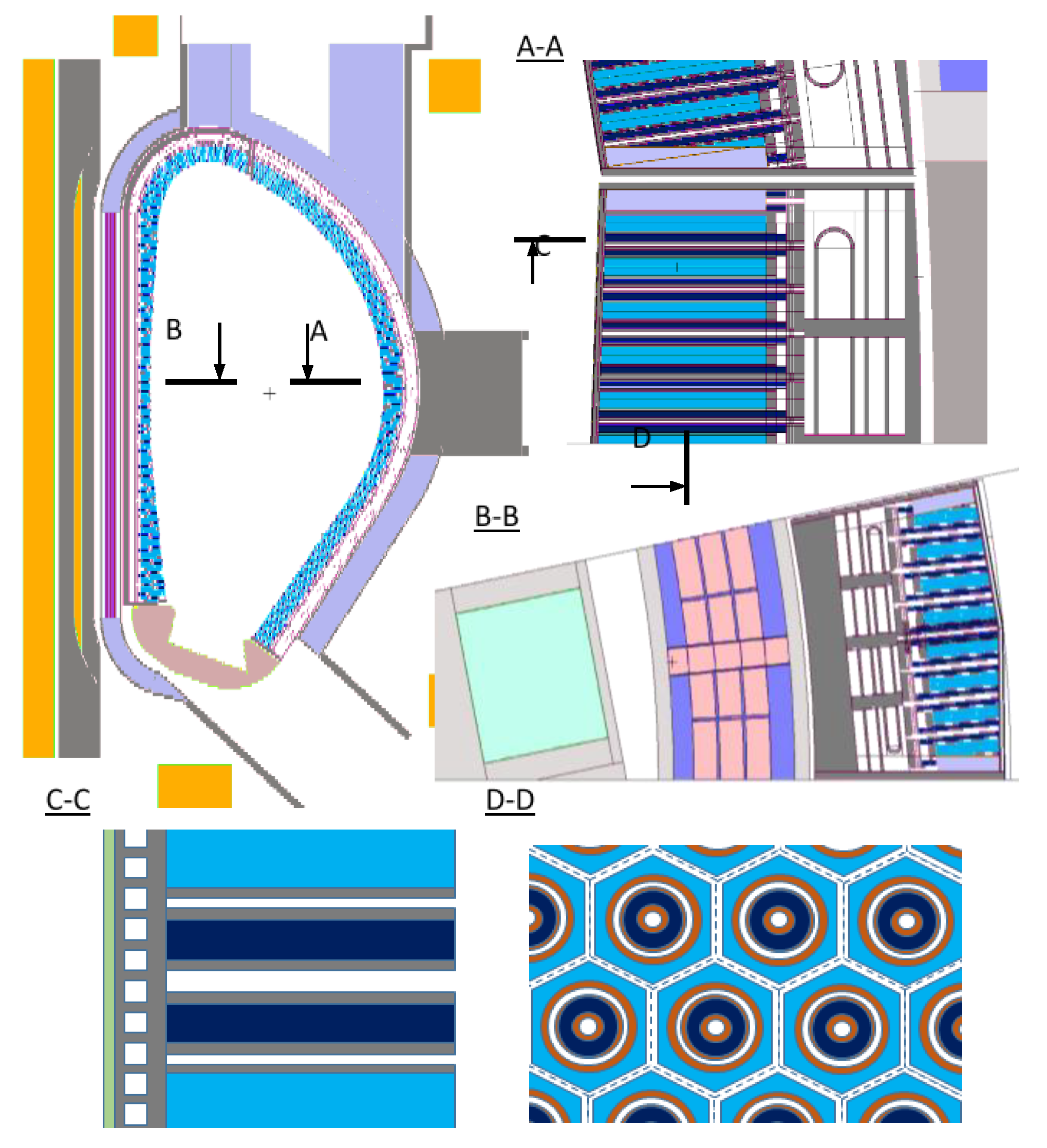

2.2.1. Segmentation and modularization

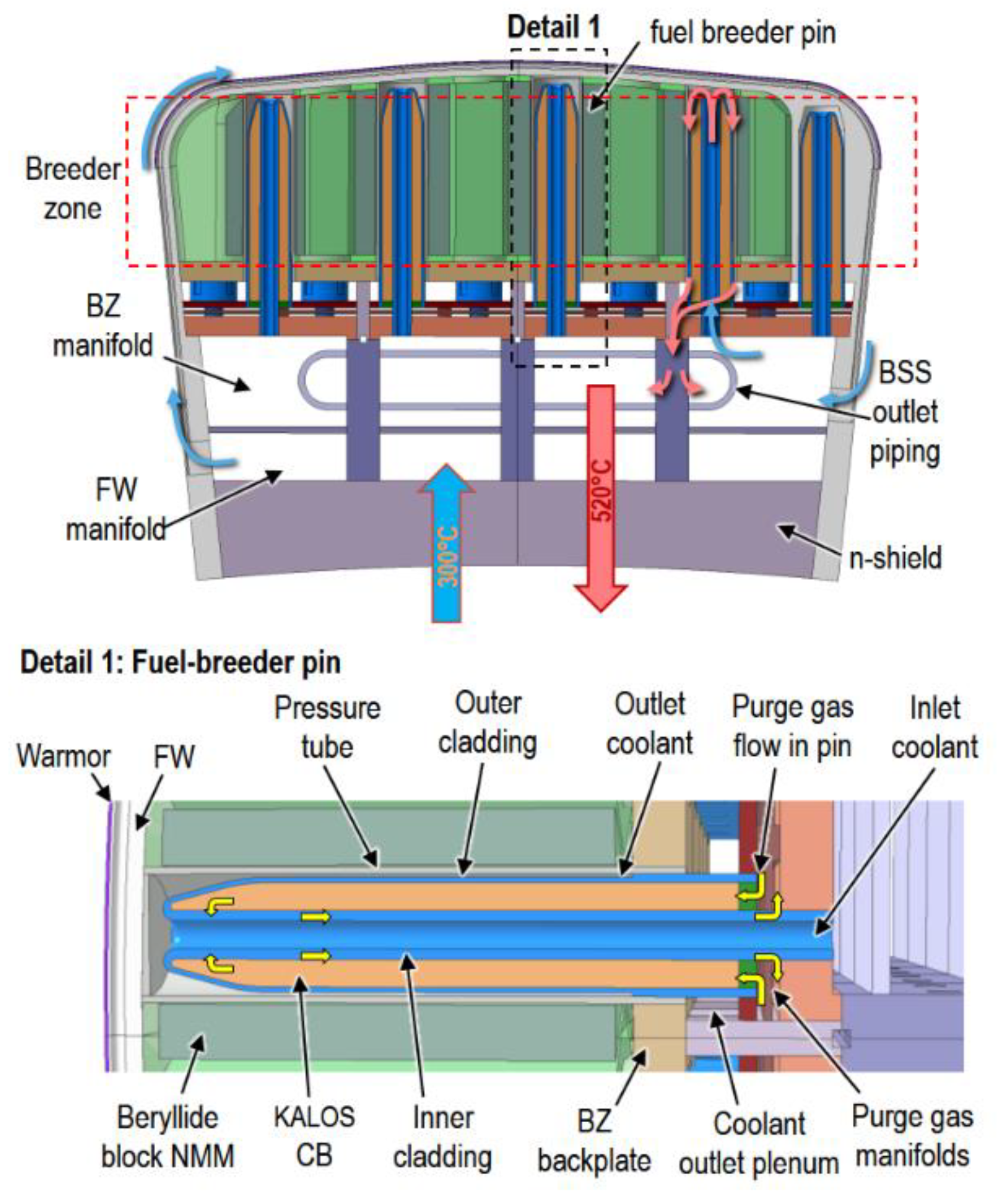

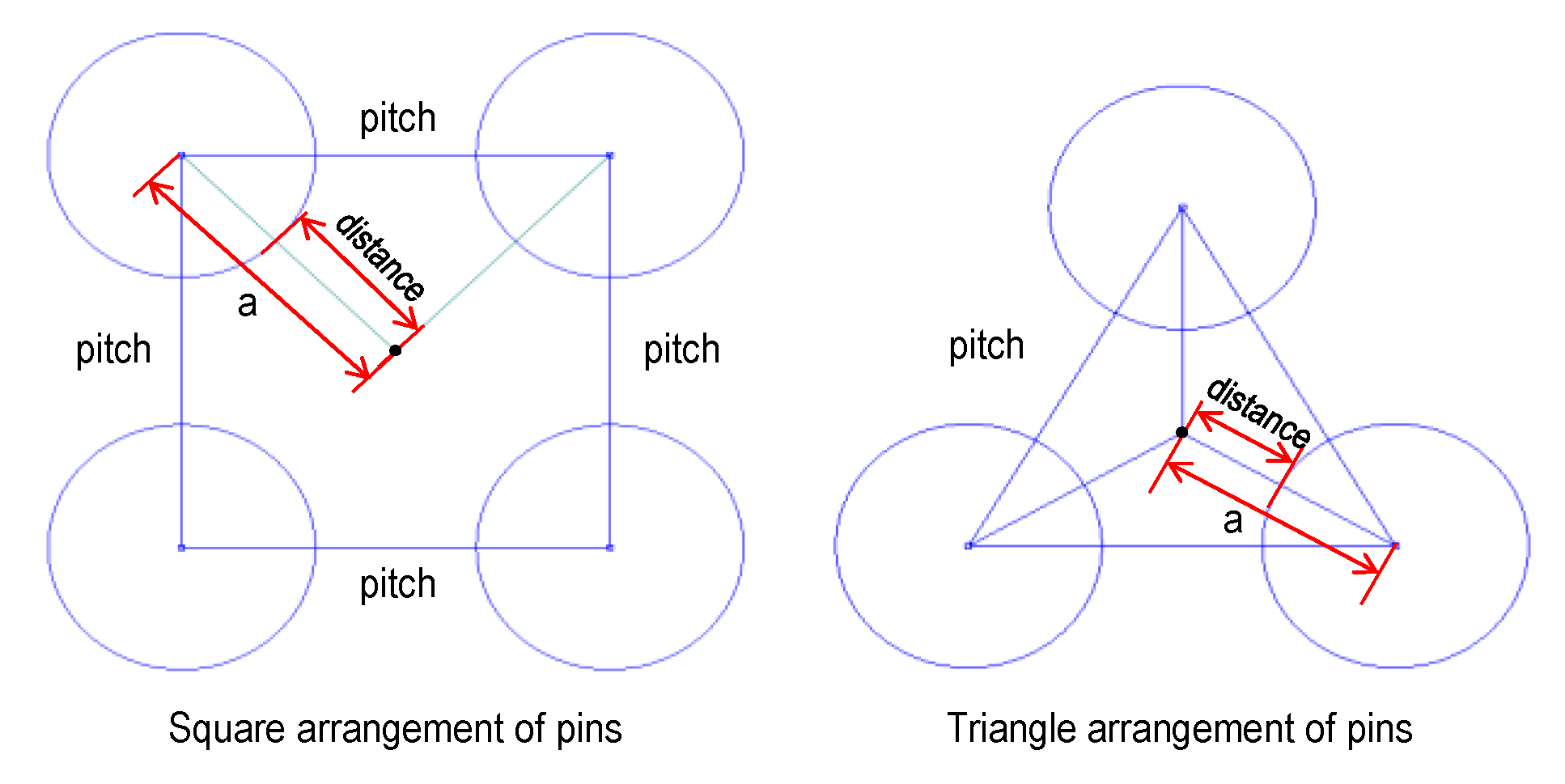

2.2.2. Design features

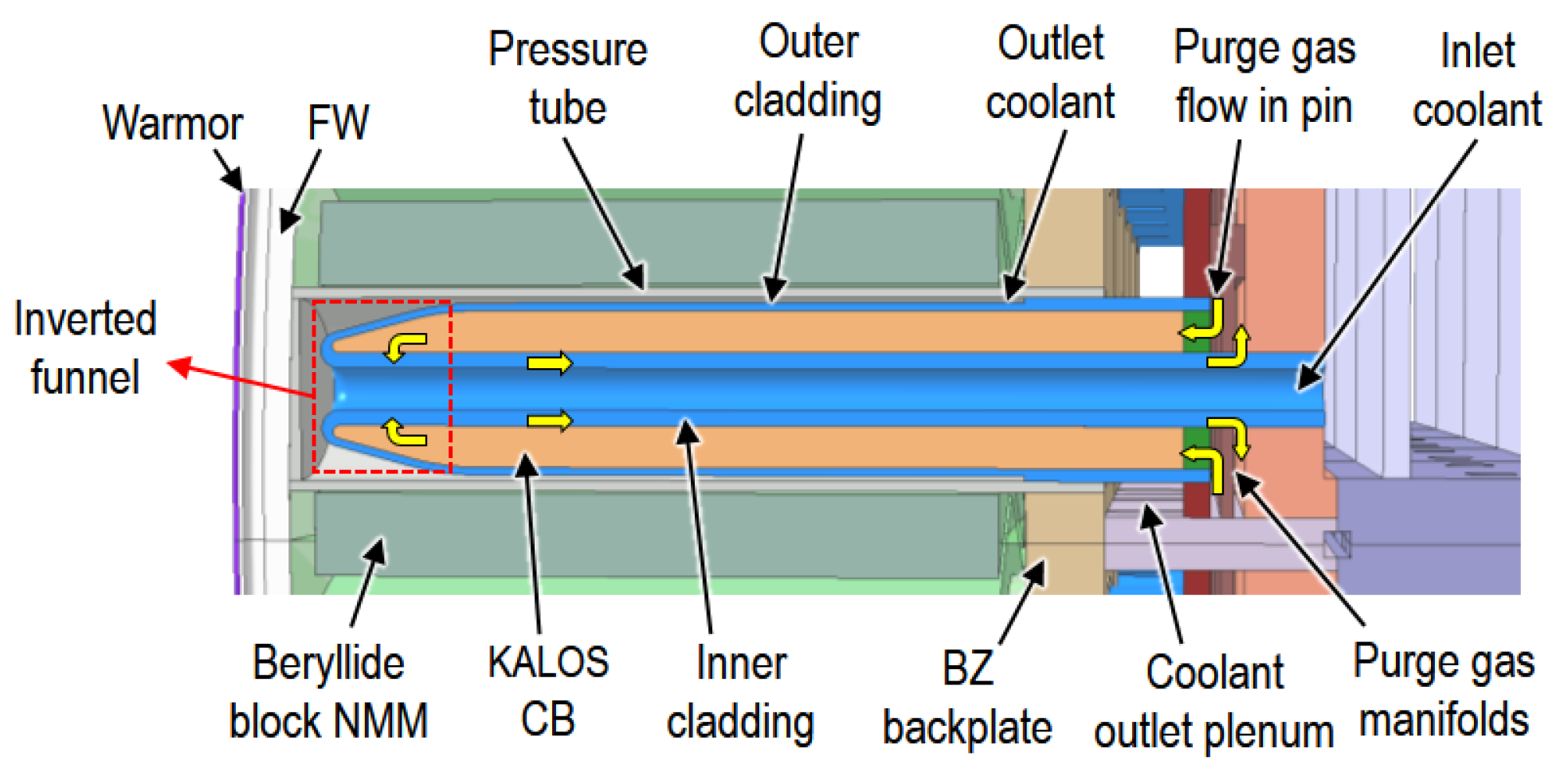

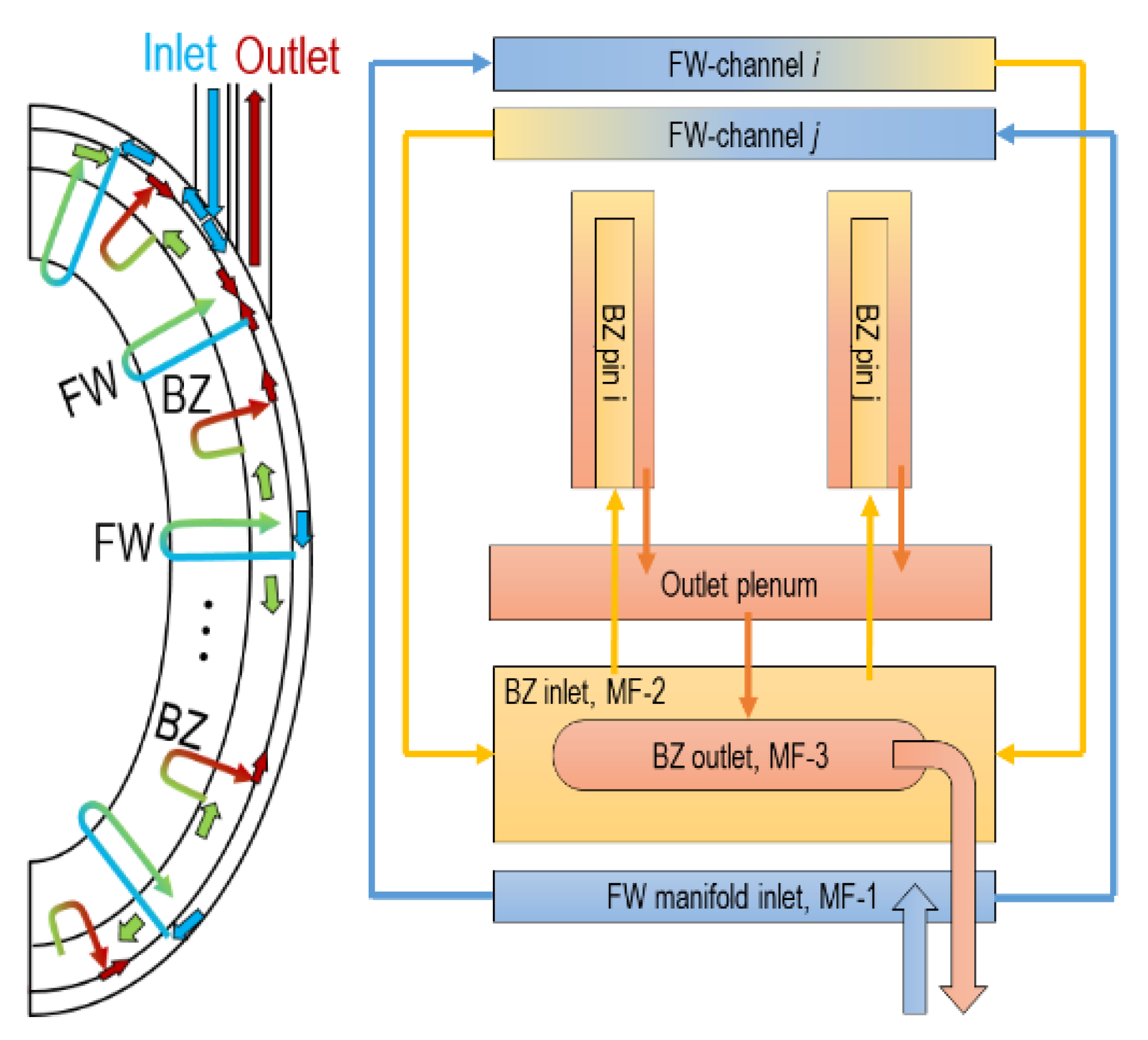

2.2.3. Coolant choice, parameters and flow scheme

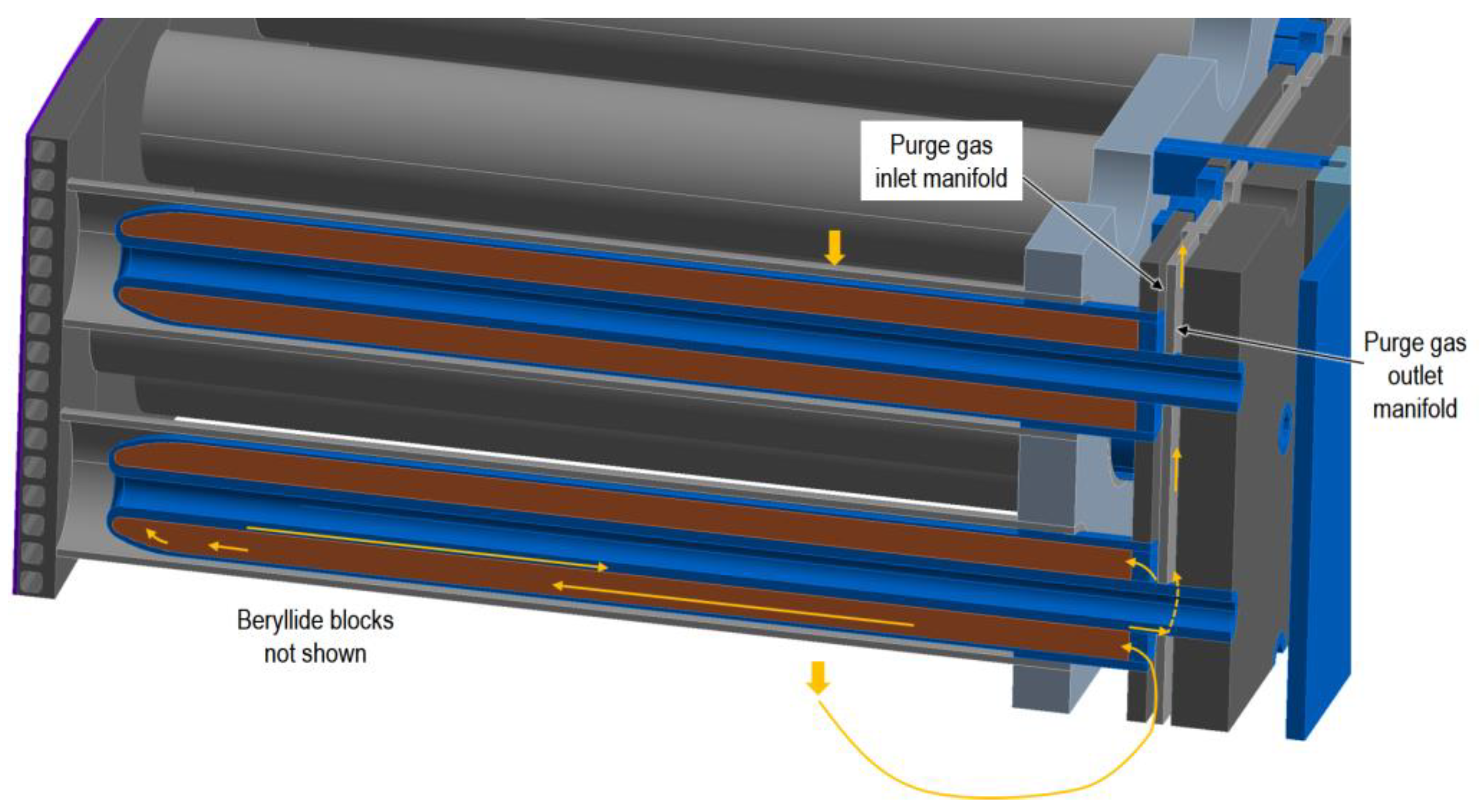

2.2.4. Purge gas choice, parameters and flow scheme

3. Main performance analyses

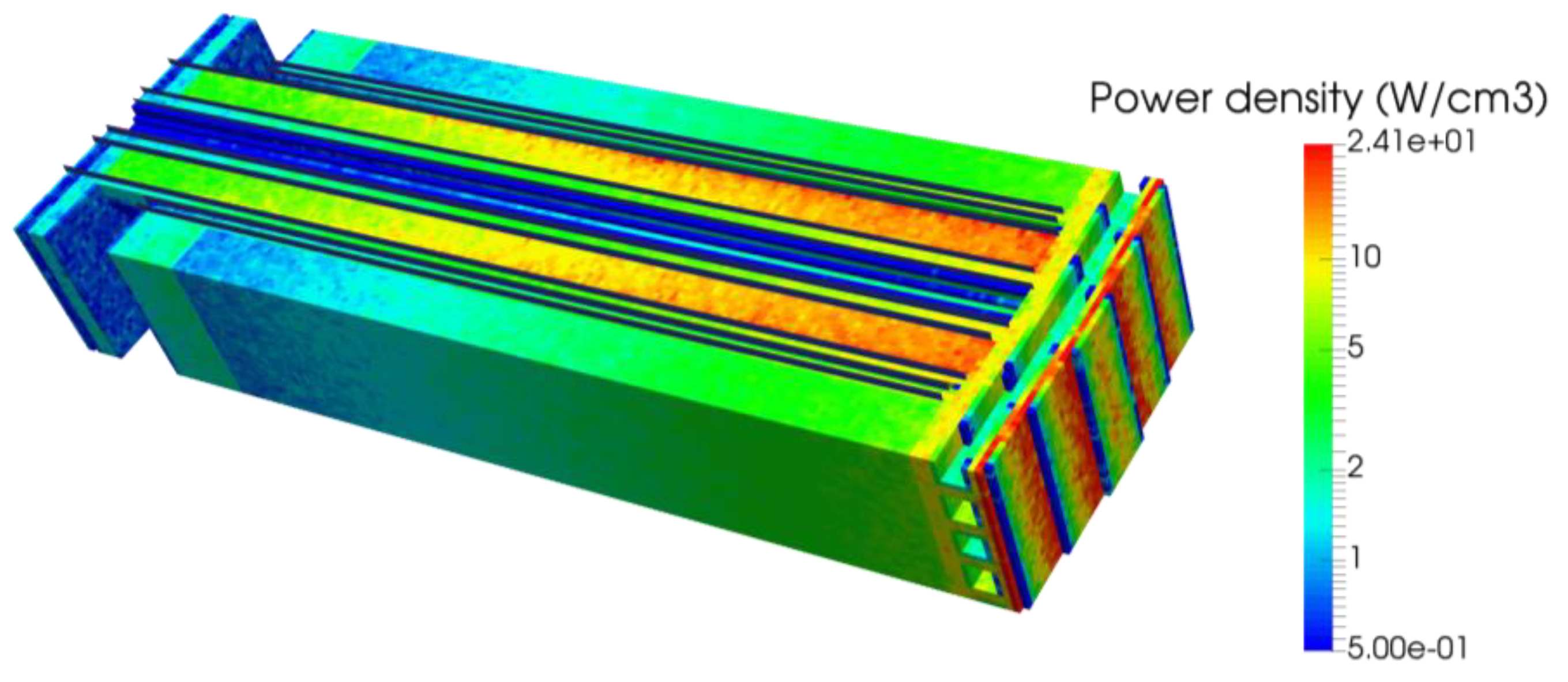

3.1. Nuclear analyses

3.2. Thermal hydraulic analyses

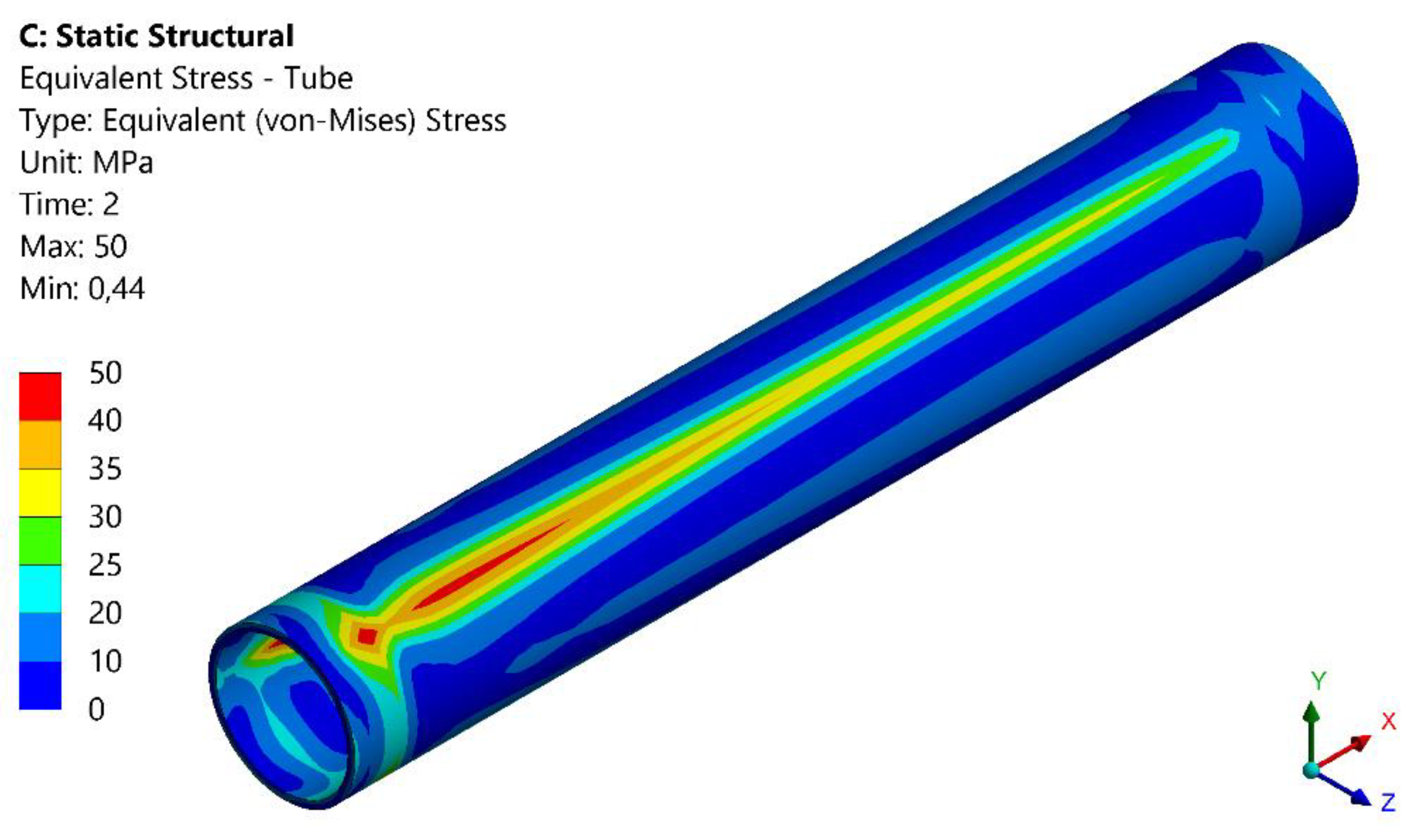

3.3. Thermal mechanical analyses

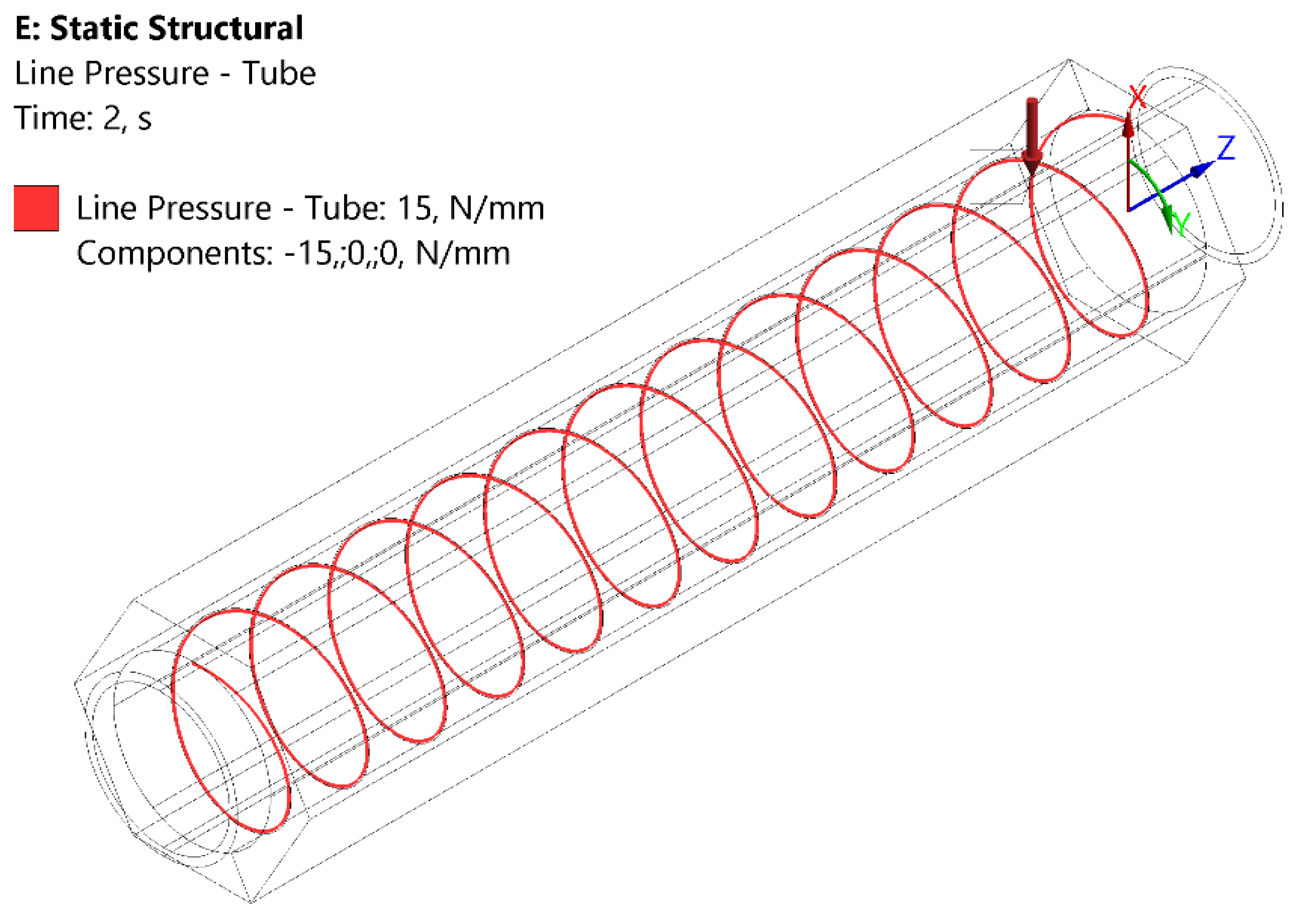

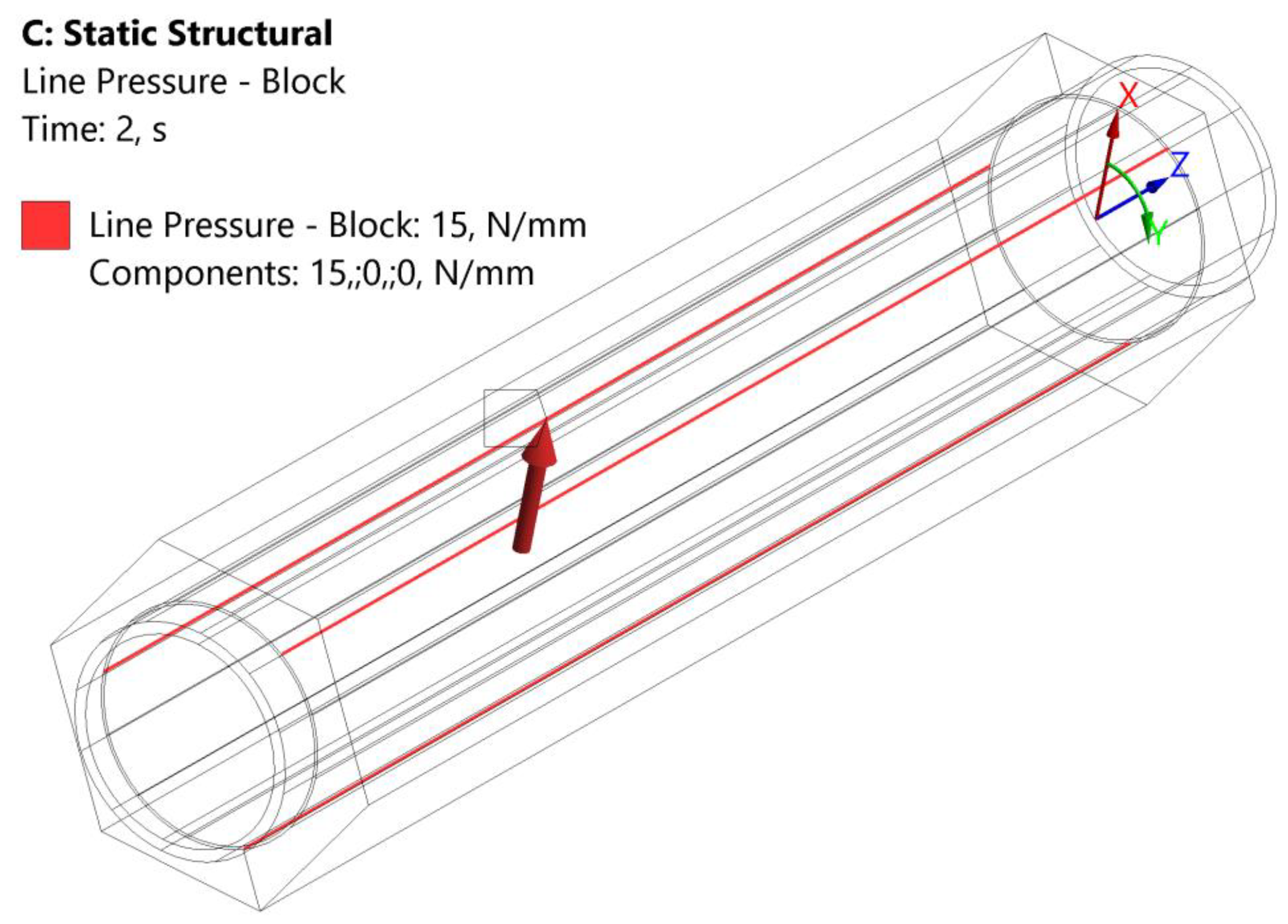

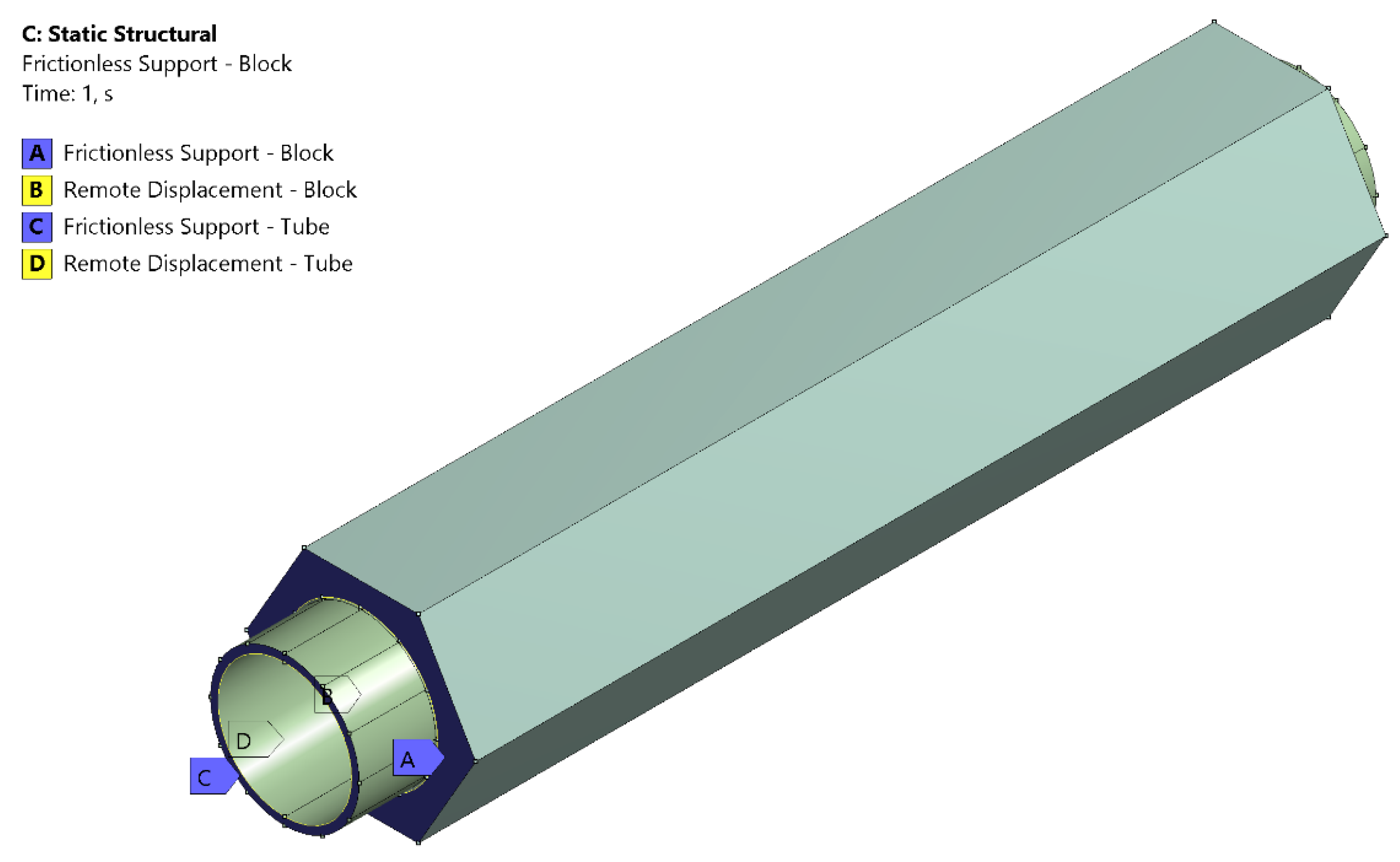

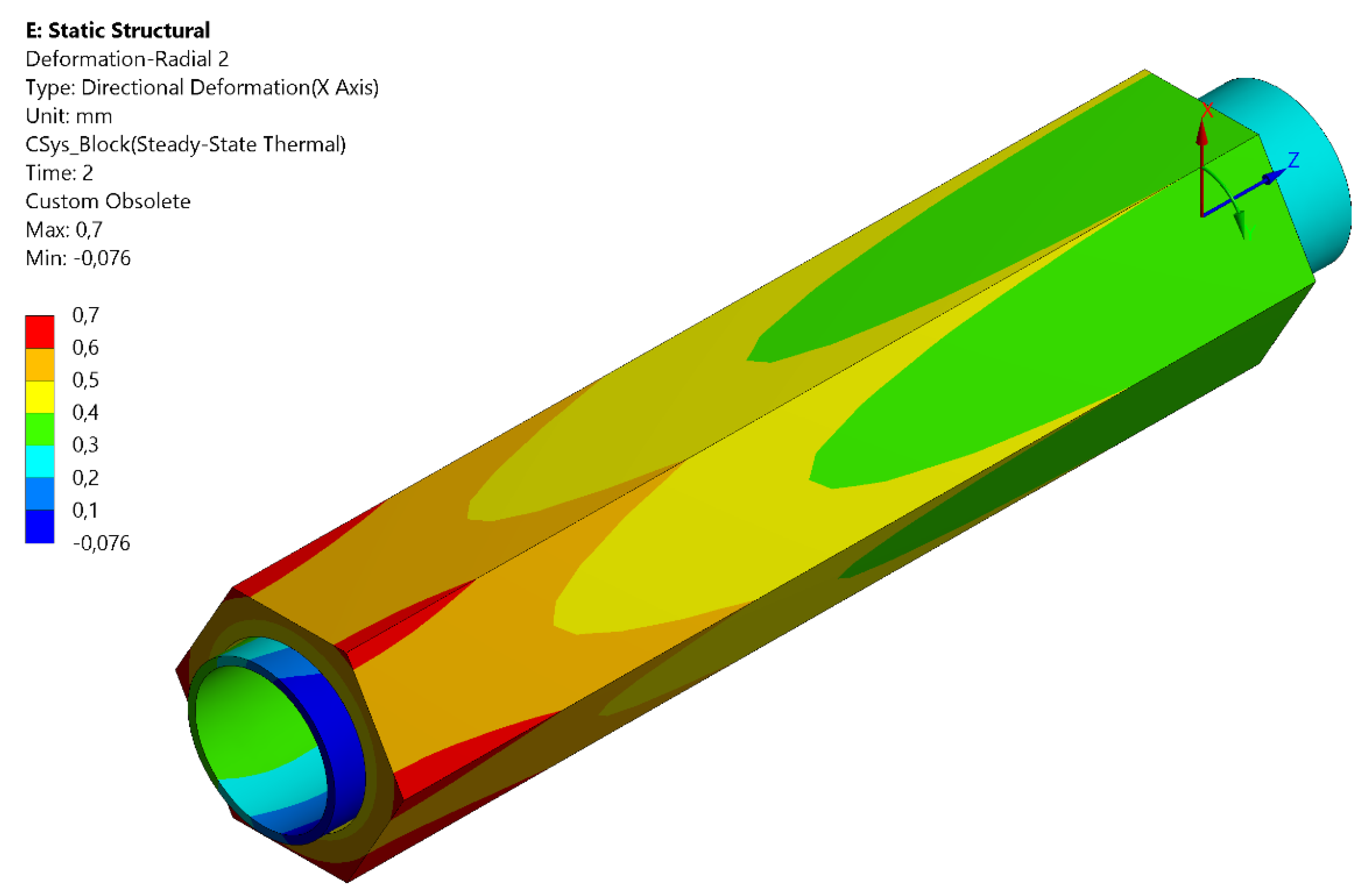

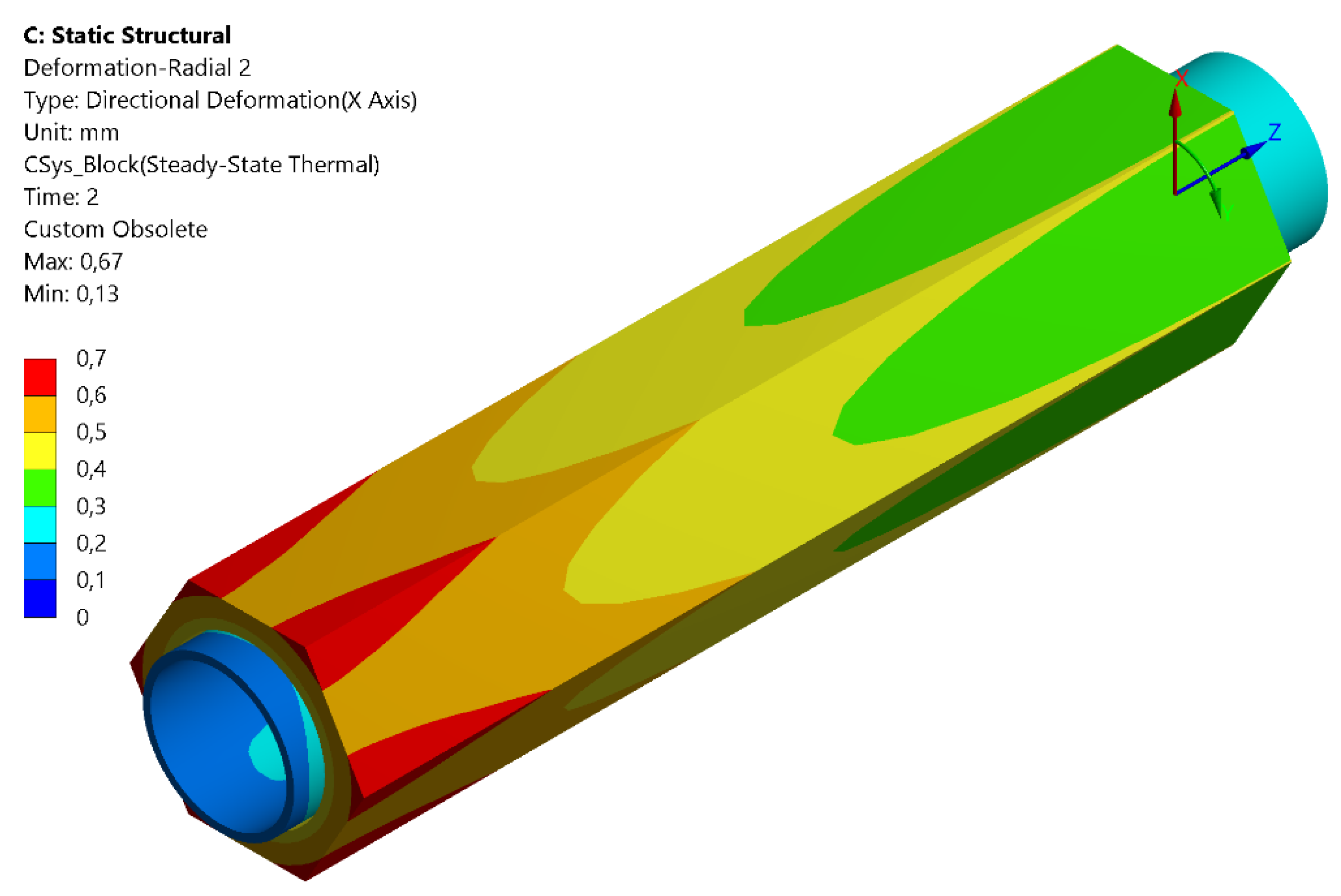

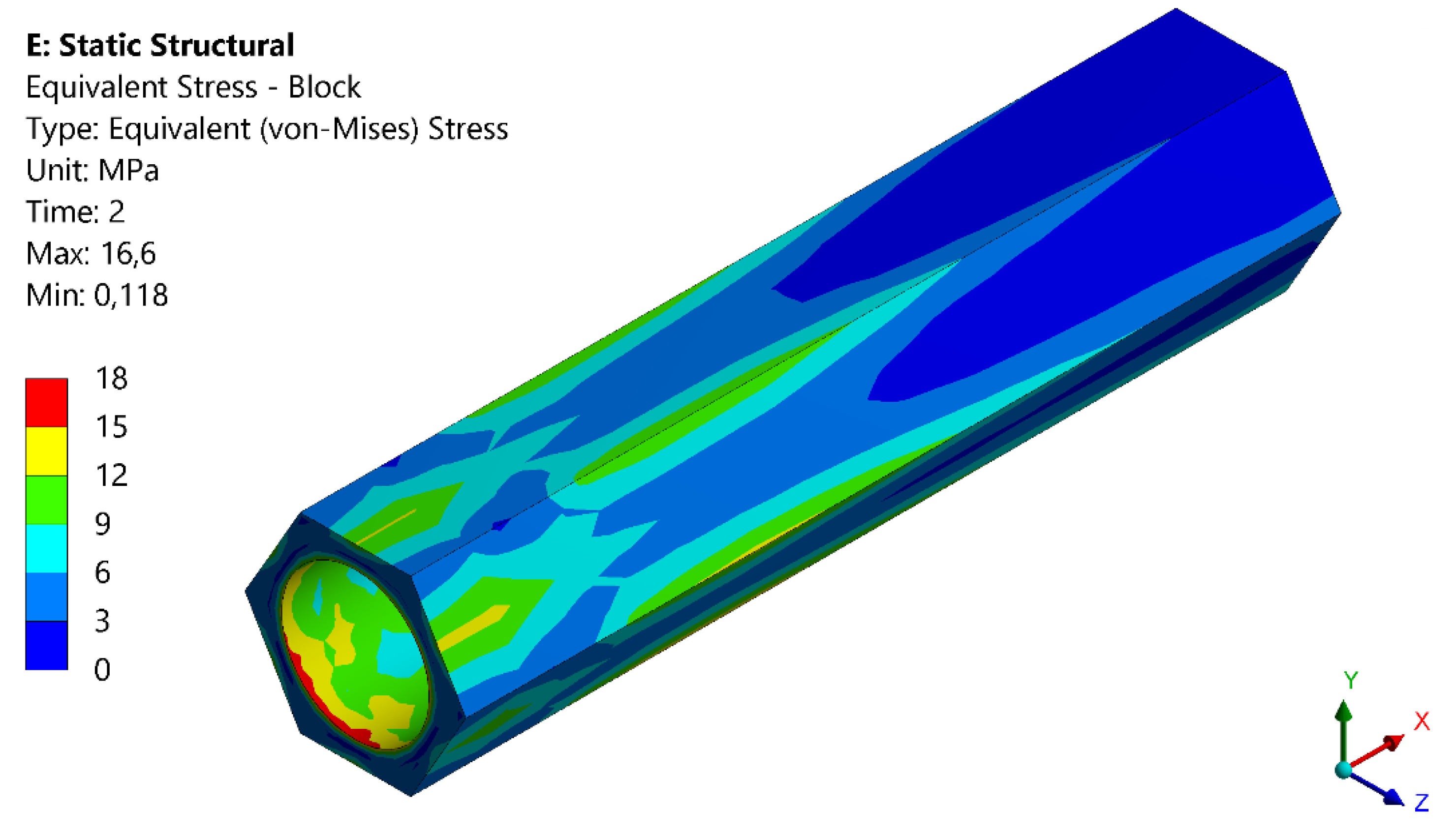

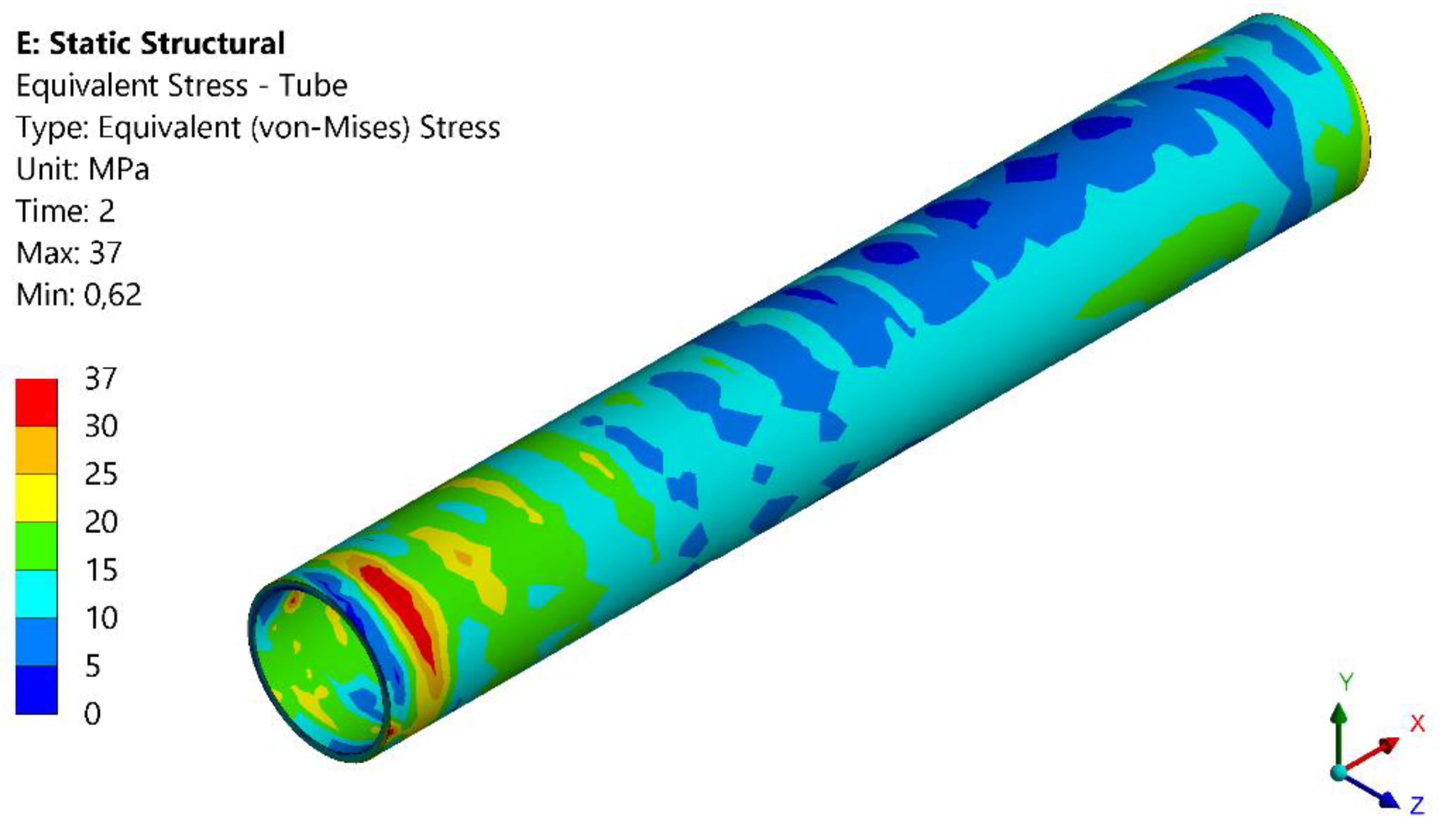

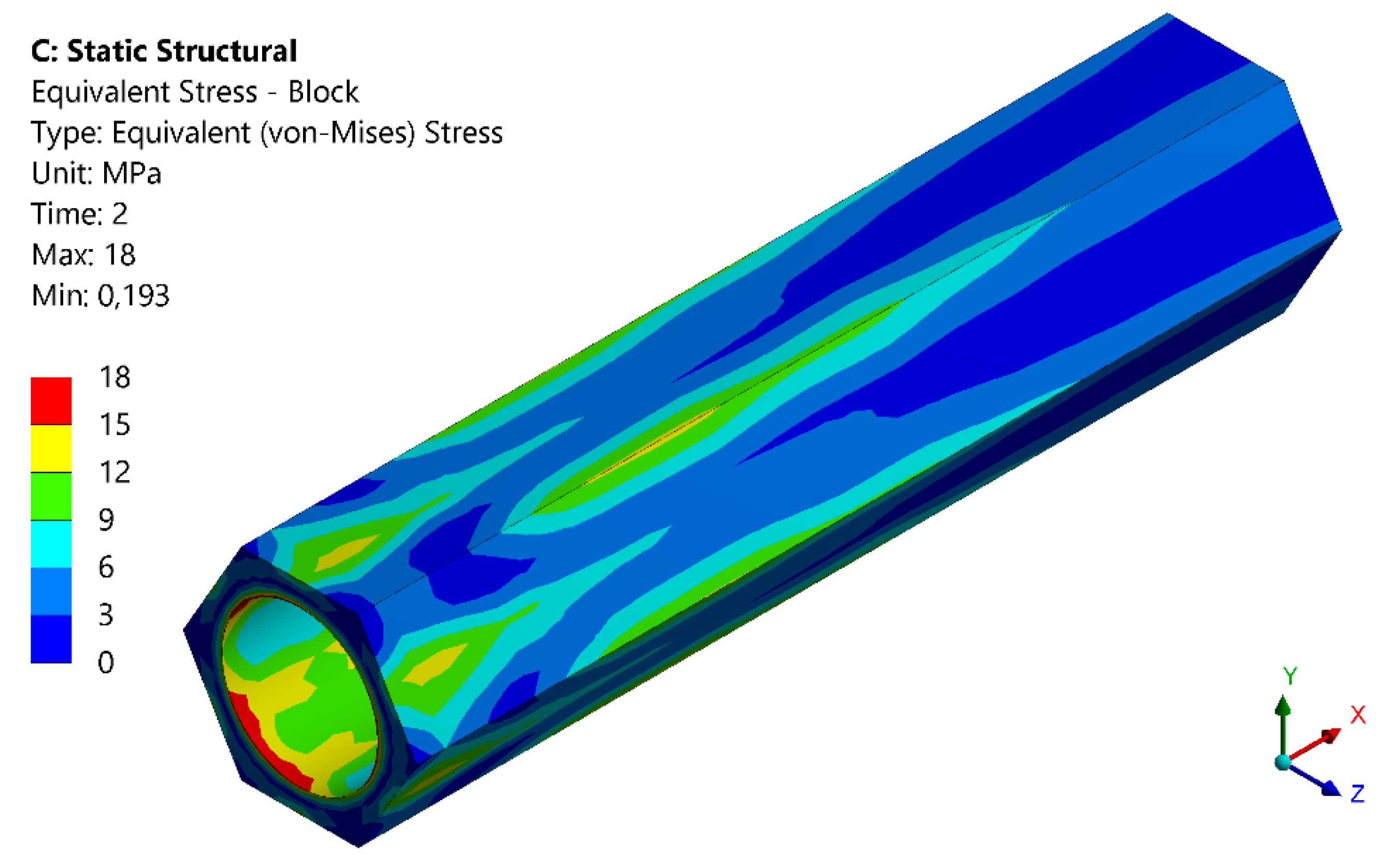

3.3.1. Elastic analyses on a detailed unit slice

3.3.2. Inelastic analyses on the cap region of HCPB BB

3.3.3. Global elastic analyses of blanket sector

3.3.4. First thermal mechanical analyses of a single beryllide block

3.4. Tritium transport analysis

4. Alternative breeding blanket concepts

4.1. CO2 Cooled Pebble Bed (CCPB) concept

4.2. Helium cooled Molten Lead Ceramic Breeder (MLCB) concept

4.3. Water cooled Lead Ceramic Breeder (WLCB) concept

5. Summary and outlook

- C1.

- Low reliability of BB system under DEMO conditions due to welds failure

- C2.

- Loss of structural integrity of beryllide blocks

- C3.

- High pressure drops in coolant loop contributing to total high pumping power

- C4.

- Large tritium permeation rates at the interface of breeder-coolant loop

- C5.

- Low BB shielding capability

- C6.

- High EM loads due to disruption events

- C7.

- Degradation of Eurofer97 at contact with pebbles in purge gas environment

- S1.

- Equalize purge gas and coolant to eliminate in-box LOCA welds, hence improving reliability

- S2.

- New shaping of block to reduce cracking of beryllide

- S3.

- Increase temperature difference between outlet and inlet, hence reducing flow velocity & pressure drop

- S4.

- Different purge gas schemes (add steam to purge gas and counter-permeation) to reduce permeation

- S5.

- Explore more efficient shielding materials

- S6.

- Insulate the connection between BB and VV

- S7.

- Make the pebble container have no structural function

- T1.

- Demonstrate high heat flux capability with augmented structure

- T2.

- Increase the scalability of beryllide block fabrication to DEMO scale

- T3.

- Demonstrate reaction of beryllide with water at high temperature is not critical

- T4.

- Select suitable supplier or different fabrication route to have low U impurity to eliminate the activation issue

- T5.

- Demonstrate industrial production of the KALOS ceramic breeder pebble

- T6.

- Demonstrate feasibility of manufacturing a full blanket segment at DEMO scale

- T7.

- Reduce tritium permeation by trying different purge gas schemes and demonstrate the selected scheme causes no additional issue

- T8.

- Develop & validate advanced tritium transport tools to increase confidence on tritium transport modelling

- T9.

- Develop reliable tools of pebble bed and validate tools with experiments

- T10.

- Develop suitable Li-6 enrichment process to ensure lower costs

- T11.

- Demonstrate feasibility of recycling functional materials

- T12.

- Irradiate the structural and function materials, conduct post-irradiation examination, to evaluate characteristics & properties to understand their irradiation behaviours

- T13.

- Establish a reproducible route of coating the FW with tungsten on large components

- T14.

- Age Eurofer97 in controlled environment at DEMO conditions and understand the degradation level of Eurofer97

- T15.

- Test the components of HCPB BB at prototypical scale to increase the maturity level of HCPB BB

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Donné, A.J.H. The European Roadmap towards Fusion Electricity. Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society A: Mathematical, Physical and Engineering Sciences 2019, 377, 20170432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Federici, G.; Bachmann, C.; Barucca, L.; Baylard, C.; Biel, W.; Boccaccini, L.V.; Bustreo, C.; Ciattaglia, S.; Cismondi, F.; Corato, V.; et al. Overview of the DEMO Staged Design Approach in Europe. Nucl. Fusion 2019, 59, 066013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- EUROfusion official website: https://www.euro-fusion.org/about-eurofusion/.

- Federici, G.; Baylard, C.; Beaumont, A.; Holden, J. The Plan Forward for EU DEMO. Fusion Engineering and Design 2021, 173, 112960. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hernández, F.A.; Pereslavtsev, P.; Zhou, G.; Kang, Q.; D’Amico, S.; Neuberger, H.; Boccaccini, L.V.; Kiss, B.; Nádasi, G.; Maqueda, L.; et al. Consolidated Design of the HCPB Breeding Blanket for the Pre-Conceptual Design Phase of the EU DEMO and Harmonization with the ITER HCPB TBM Program. Fusion Engineering and Design 2020, 157, 111614. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arena, P.; Del Nevo, A.; Moro, F.; Noce, S.; Mozzillo, R.; Imbriani, V.; Giannetti, F.; Edemetti, F.; Froio, A.; Savoldi, L.; et al. The DEMO Water-Cooled Lead–Lithium Breeding Blanket: Design Status at the End of the Pre-Conceptual Design Phase. Applied Sciences 2021, 11, 11592. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Federici, G.; Boccaccini, L.; Cismondi, F.; Gasparotto, M.; Poitevin, Y.; Ricapito, I. An Overview of the EU Breeding Blanket Design Strategy as an Integral Part of the DEMO Design Effort. Fusion Engineering and Design 2019, 141, 30–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dalle Donne, M. et al., Conceptual design of two helium cooled fusion blankets (ceramic and liquid breeder) for INTOR. KfK-3584. 1983 Kernforschungszentrum Karlsruhe.

- Dalle Donne, M.; Anzidei, L.; Kwast, H.; Moons, F.; Proust, E. Status of EC Solid Breeder-Blanket Designs and R&D for DEMO Fusion Reactors. Fusion Engineering and Design 1995, 27, 319–336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boccaccini, L.V.; Bekris, N.; Chen, Y.; Fischer, U.; Gordeev, S.; Hermsmeyer, S.; Hutter, E.; Kleefeldt, K.; Malang, S.; Schleisiek, K.; et al. Design Description and Performance Analyses of the European HCPB Test Blanket System in ITER Feat. Fusion Engineering and Design 2002, 61–62, 339–344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hernández, F.; Pereslavtsev, P.; Kang, Q.; Norajitra, P.; Kiss, B.; Nádasi, G.; Bitz, O. A New HCPB Breeding Blanket for the EU DEMO: Evolution, Rationale and Preliminary Performances. Fusion Engineering and Design 2017, 124, 882–886. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, G.; Hernández, F.; Boccaccini, L.V.; Chen, H.; Ye, M. Preliminary Structural Analysis of the New HCPB Blanket for EU DEMO Reactor. International Journal of Hydrogen Energy 2016, 41, 7053–7058. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, G.; Hernández, F.; Boccaccini, L.V.; Chen, H.; Ye, M. Design Study on the New EU DEMO HCPB Breeding Blanket: Thermal Analysis. Progress in Nuclear Energy 2017, 98, 167–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boccaccini, L.V.; Aiello, A.; Bede, O.; Cismondi, F.; Kosek, L.; Ilkei, T.; Salavy, J.-F.; Sardain, P.; Sedano, L. Present Status of the Conceptual Design of the EU Test Blanket Systems. Fusion Engineering and Design 2011, 86, 478–483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, G.; Hernández, F.A.; Zeile, C.; Maione, I.A. Transient Thermal Analysis and Structural Assessment of an Ex-Vessel LOCA Event on the EU DEMO HCPB Breeding Blanket and the Attachment System. Fusion Engineering and Design 2018, 136, 34–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hernández, F.A.; Pereslavtsev, P.; Zhou, G.; Kiss, B.; Kang, Q.; Neuberger, H.; Chakin, V.; Gaisin, R.; Vladimirov, P.; Boccaccini, L.V.; et al. Advancements in the Helium-Cooled Pebble Bed Breeding Blanket for the EU DEMO: Holistic Design Approach and Lessons Learned. Fusion Science and Technology 2019, 75, 352–364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Federici, G.; Bachmann, C.; Barucca, L.; Biel, W.; Boccaccini, L.; Brown, R.; Bustreo, C.; Ciattaglia, S.; Cismondi, F.; Coleman, M.; et al. DEMO Design Activity in Europe: Progress and Updates. Fusion Engineering and Design 2018, 136, 729–741. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Knitter, R.; Chaudhuri, P.; Feng, Y.J.; Hoshino, T.; Yu, I.-K. Recent Developments of Solid Breeder Fabrication. Journal of Nuclear Materials 2013, 442, S420–S424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vladimirov, P.V.; Chakin, V.P.; Dürrschnabel, M.; Gaisin, R.; Goraieb, A.; Gonzalez, F.A.H.; Klimenkov, M.; Rieth, M.; Rolli, R.; Zimber, N.; et al. Development and Characterization of Advanced Neutron Multiplier Materials. Journal of Nuclear Materials 2021, 543, 152593. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, G.; Ghidersa, B.-E.; Hernández, F.A.; Kang, Q.; Neuberger, H. Design of Two Experimental Mock-Ups as Proof-of-Concept and Validation Test Rigs for the Enhanced EU DEMO HCPB Blanket. Fusion Science and Technology 2019, 75, 1016–1023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bachmann, C.; Ciattaglia, S.; Cismondi, F.; Eade, T.; Federici, G.; Fischer, U.; Franke, T.; Gliss, C.; Hernandez, F.; Keep, J.; et al. Overview over DEMO Design Integration Challenges and Their Impact on Component Design Concepts. Fusion Engineering and Design 2018, 136, 87–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- CANDU 6 Program Team, CANDU® 6 Technical Summary, 2005.

- Smoluchowski, M. Über den Temperatursprung bei Wärmeleitung in Gasen. Pisma Mariana Smoluchowskiego 1924, 1, 113–138. [Google Scholar]

- Pupeschi, S.; Knitter, R.; Kamlah, M. Effective Thermal Conductivity of Advanced Ceramic Breeder Pebble Beds. Fusion Engineering and Design 2017, 116, 73–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cristescu, I.; Draghia, M. Developments on the Tritium Extraction and Recovery System for HCPB. Fusion Engineering and Design 2020, 158, 111558. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, F. et al. 2010 MCNP5-1.60 Release Notes. LA-UR-10-06235. Los Alamos National Laboratory.

- Plompen, A.J.M.; Cabellos, O.; De Saint Jean, C.; Fleming, M.; Algora, A.; Angelone, M.; Archier, P.; Bauge, E.; Bersillon, O.; Blokhin, A.; et al. The Joint Evaluated Fission and Fusion Nuclear Data Library, JEFF-3.3. Eur. Phys. J. A 2020, 56, 181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsige-Tamirat, H.; Fischer, U., CAD interface for Monte Carlo particle transport codes. The Conference of the Monte Carlo method: versatility unbounded in a dynamic computing world, Chattanooga, Tennessee, April 17–21, 2005 American Nuclear Society.

- Lu, L. et al., Improved solid decomposition algorithms for the CAD-to-MC conversion tool McCad. Fusion Eng. Des. 2017, 124, 1269–1272. [CrossRef]

- Pereslavtsev, P. et al., Nuclear analyses of solid breeder blanket options for DEMO: status, challenges and outlook. Fusion Eng. Des. 2019, 146, 563–567. [CrossRef]

- Pereslavtsev, P.; Cismondi, F.; Hernández, F.A. Analyses of the Shielding Options for HCPB DEMO Blanket. Fusion Engineering and Design 2020, 156, 111605. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guirao, J.; Walsh, M.J.; Udintsev, V.S.; Iglesias, S.; Giacomin, T.; Bertalot, L.; Shigin, P.; Kochergin, M.; Alexandrov, E.; Zvonkov, A.; et al. Standardized Integration of ITER Diagnostics Equatorial Port Plugs. Fusion Engineering and Design 2019, 146, 1548–1552. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, J.H.; Pereslavtsev, P. Comparative Activation Analyses for the HCPB Breeding Blanket in DEMO. Fusion Engineering and Design 2021, 167, 112338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, G.; Kang, Q.; Hernández, F.A.; D’Amico, S.; Kiss, B. Thermal Hydraulics Activities for Consolidating HCPB Breeding Blanket of the European DEMO. Nucl. Fusion 2020, 60, 096008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hernández, F.A.; Arbeiter, F.; Boccaccini, L.V.; Bubelis, E.; Chakin, V.P.; Cristescu, I.; Ghidersa, B.E.; González, M.; Hering, W.; Hernández, T.; et al. Overview of the HCPB Research Activities in EUROfusion. IEEE Transactions on Plasma Science 2018, 46, 2247–2261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- RCC-MRx: Design and Construction Rules for mechanical components of nuclear installations. Addenda included: n° 1 (2013).

- Aiello, G.; Aktaa, J.; Cismondi, F.; Rampal, G.; Salavy, J.F.; Tavassoli, F. Assessment of Design Limits and Criteria Requirements for Eurofer Structures in TBM Components. Journal of Nuclear Materials 2011, 414, 53–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Retheesh, A.; Hernández, F.A.; Zhou, G. Application of Inelastic Method and Its Comparison with Elastic Method for the Assessment of In-Box LOCA Event on EU DEMO HCPB Breeding Blanket Cap Region. Applied Sciences 2021, 11, 9104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maione, I.A.; Roccella, M.; Hernández, F.A.; Lucca, F. Update of Electromagnetic Loads on HCPB Breeding Blanked for DEMO 2017 Configuration. Fusion Engineering and Design 2020, 156, 111604. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carella, E.; Moreno, C.; Urgorri, F.R.; Rapisarda, D.; Ibarra, A. Tritium Modelling in HCPB Breeder Blanket at a System Level. Fusion Engineering and Design 2017, 124, 687–691. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Franza, F.; Boccaccini, L.V.; Ciampichetti, A.; Zucchetti, M. Tritium Transport Analysis in HCPB DEMO Blanket with the FUS-TPC Code. Fusion Engineering and Design 2013, 88, 2444–2447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pasler, V.; Arbeiter, F.; Klein, C.; Klimenko, D.; Schlindwein, G.; von der Weth, A. Development of a Component-Level Hydrogen Transport Model with OpenFOAM and Application to Tritium Transport Inside a DEMO HCPB Breeder. Applied Sciences 2021, 11, 3481. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carella, E.; Moreno, C.; Urgorri, F.R.; Demange, D.; Castellanos, J.; Rapisarda, D. Tritium Behavior in HCPB Breeder Blanket Unit: Modeling and Experiments. Fusion Science and Technology 2017, 71, 357–362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klimenko, D.; Arbeiter, F.; Pasler, V.; Schlindwein, G.; von der Weth, A.; Zinn, K. Definition of the Q-PETE Experiment for Investigation of Hydrogen Isotopes Permeation through the Metal Structures of a DEMO HCPB Breeder Zone. Fusion Engineering and Design 2018, 136, 563–568. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, S.; Hernández, F.A.; Bubelis, E.; Chen, H. Comparative Analysis of the Efficiency of a CO2-Cooled and a He-Cooled Pebble Bed Breeding Blanket for the EU DEMO Fusion Reactor. Fusion Engineering and Design 2019, 138, 32–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, S.; Hernández, F.A.; Zhou, G.; Chen, H. First Thermal-Hydraulic Analysis of a CO2 Cooled Pebble Bed Blanket for the EU DEMO. Fusion Engineering and Design 2019, 146, 2218–2221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, S.; Hernández, F.A.; Chen, H.; Zhou, G. Thermal-Hydraulic Analysis of the First Wall of a CO2 Cooled Pebble Bed Breeding Blanket for the EU-DEMO. Fusion Engineering and Design 2019, 138, 379–394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hernández, F.A.; Pereslavtsev, P. First Principles Review of Options for Tritium Breeder and Neutron Multiplier Materials for Breeding Blankets in Fusion Reactors. Fusion Engineering and Design 2018, 137, 243–256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, G.; Hernández, F.A.; Kang, Q.; Pereslavtsev, P. Progress on the Helium Cooled Molten Lead Ceramic Breeder Concept, as a near-Term Alternative Blanket for EU DEMO. Fusion Engineering and Design 2019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, G.; Lu, Y.; Hernández, F.A. A Water Cooled Lead Ceramic Breeder Blanket for European DEMO. Fusion Engineering and Design 2021, 168, 112397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, Y.; Ye, M.; Zhou, G.; Hernández, F.A.; Leppänen, J.; Hu, Y. Exploratory Tritium Breeding Performance Study on a Water Cooled Lead Ceramic Breeder Blanket for EU DEMO Using Serpent-2. Nuclear Materials and Energy 2021, 28, 101050. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| BB region | FW height (poloidal) | FW width (toroidal) | FW sidewall length (radial) |

|---|---|---|---|

| [mm] | [mm] | [mm] | |

| R/LOB1 | 531 | 947 | 485 |

| R/LOB2 | 750 | 1046 | 478 |

| R/LOB3 | 750 | 1170 | 474 |

| R/LOB4 | 625 | 1270 | 474 |

| R/LOB5 | 625 | 1355 | 488 |

| R/LOB6 | 625 | 1331 | 495 |

| R/LOB7 | 625 | 1494 | 505 |

| R/LOB8 | 625 | 1547 | 508 |

| R/LOB9 | 625 | 1585 | 510 |

| R/LOB10 | 625 | 1611 | 510 |

| R/LOB11 | 625 | 1624 | 502 |

| R/LOB12 | 500 | 1624 | 489 |

| R/LOB13 | 500 | 1612 | 461 |

| R/LOB14 | 500 | 1578 | 436 |

| R/LOB15 | 500 | 1552 | 416 |

| R/LOB16 | 500 | 1507 | 400 |

| R/LOB17.1 | 1528 | 1406 | 423 |

| R/LOB17.2 | 1528 | 1204 | 464 |

| R/LOB17.3 | 1528 | 1018 | 505 |

| BB region |

FW height (poloidal) | FW width (toroidal) | FW sidewall length (radial) |

|---|---|---|---|

| [mm] | [mm] | [mm] | |

| R/LIB12 | 1406 | 1140 | 658 |

| R/LIB11 | 1406 | 1140 | 497 |

| R/LIB10 | 1406 | 1140 | 352 |

| R/LIB9 | 1151 | 1095 | 291 |

| R/LIB8 | 1151 | 1095 | 291 |

| R/LIB7 | 1125 | 1117 | 322 |

| R/LIB6 | 1125 | 1117 | 415 |

| R/LIB5 | 1125 | 1117 | 482 |

| R/LIB4 | 375 | 1150 | 532 |

| R/LIB3.3 | 375 | 1172 | 573 |

| R/LIB3.2 | 375 | 1210 | 519 |

| R/LIB3.1 | 375 | 1263 | 498 |

| R/LIB2.2 | 375 | 1335 | 466 |

| R/LIB2.1 | 375 | 1414 | 464 |

| R/LIB1.3 | 250 | 1475 | 478 |

| R/LIB1.2 | 250 | 1536 | 488 |

| R/LIB1.1 | 531 | 1614 | 494 |

| BB Region | Width (pol.) | Height (rad.) | BB Region | Width (pol.) | Height (rad.) | BB Region | Width (pol.) | Height (rad.) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| [mm] | [mm] | [mm] | [mm] | [mm] | [mm] | |||

| R/LOB1 | 12 | 14 | COB1 | 12 | 12 | R/LIB12 | 12 | 12 |

| R/LOB2 | 12 | 11 | COB2 | 12 | 12 | R/LIB11 | 12 | 12 |

| R/LOB3 | 12 | 11 | COB3 | 12 | 12 | R/LIB10 | 15 | 15 |

| R/LOB4 | 12 | 11 | COB4 | 12 | 12 | R/LIB9 | 15 | 15 |

| R/LOB5 | 12 | 12 | COB5 | 12 | 12 | R/LIB8 | 15 | 15 |

| R/LOB6 | 12 | 12 | COB6 | 12 | 12 | R/LIB7 | 10 | 8 |

| R/LOB7 | 12 | 12 | COB7 | 12 | 12 | R/LIB6 | 10 | 8 |

| R/LOB8 | 12 | 12 | COB8 | 12 | 12 | R/LIB5 | 10 | 8 |

| R/LOB9 | 12 | 12 | COB9 | 12 | 12 | R/LIB4 | 10 | 8 |

| R/LOB10 | 12 | 12 | COB10 | 12 | 12 | R/LIB3.3 | 10 | 8 |

| R/LOB11 | 12 | 12 | COB11 | 12 | 12 | R/LIB3.2 | 10 | 8 |

| R/LOB12 | 12 | 12 | COB12 | 12 | 12 | R/LIB3.1 | 10 | 8 |

| R/LOB13 | 12 | 12 | COB13 | 12 | 12 | R/LIB2.2 | 10 | 8 |

| R/LOB14 | 12 | 12 | COB14 | 12 | 12 | R/LIB2.1 | 10 | 8 |

| R/LOB15 | 12 | 12 | COB15 | 12 | 12 | R/LIB1.3 | 10 | 8 |

| R/LOB16 | 12 | 12 | COB16 | 12 | 12 | R/LIB1.2 | 10 | 8 |

| R/LOB17.1 | 12 | 12 | COB17.1 | 13 | 13 | R/LIB1.1 | 10 | 8 |

| R/LOB17.2 | 12 | 11 | COB17.2 | 13 | 13 | |||

| R/LOB17.3 | 12 | 11 | COB17.3 | 13 | 13 |

| IPI | IPFL | ||||||

| Path | Path average temp. | Linearized stress value | Stress limit | Margin | Linearized stress value | Stress limit | Margin |

| A1 | 480.0 | 210.8 | 286.2 | 50.9% | 321.0 | 455.0 | 29% |

| A2 | 480.8 | 205.3 | 285.7 | 52.1% | 317.8 | 453.1 | 30% |

| A3 | 476.3 | 200.2 | 288.3 | 53.7% | 329.8 | 463.8 | 29% |

| A4 | 448.0 | 221.8 | 304.8 | 51.5% | 384.0 | 529.9 | 28% |

| A5 | 431.6 | 215.9 | 312.6 | 53.9% | 400.6 | 559.4 | 28% |

| A6 | 431.7 | 230.6 | 312.5 | 50.8% | 363.7 | 559.2 | 35% |

| A7 | 455.8 | 217.7 | 300.4 | 51.7% | 366.3 | 512.5 | 29% |

| A8 | 456.7 | 221.6 | 299.9 | 50.7% | 361.1 | 510.3 | 29% |

| A9 | 457.3 | 216.7 | 299.5 | 51.8% | 358.5 | 508.9 | 30% |

| A10 | 458.2 | 212.5 | 299.0 | 52.6% | 353.6 | 506.8 | 30% |

| A11 | 459.5 | 214.8 | 298.2 | 52.0% | 377.1 | 503.7 | 25% |

| A12 | 438.1 | 212.6 | 309.5 | 54.2% | 374.9 | 547.7 | 32% |

| A13 | 437.3 | 212.8 | 309.8 | 54.2% | 312.4 | 549.1 | 43% |

| A14 | 451.9 | 200.1 | 302.7 | 55.9% | 304.5 | 521.7 | 42% |

| A15 | 479.4 | 206.9 | 286.5 | 51.9% | 318.7 | 456.4 | 30% |

| A16 | 481.5 | 213.6 | 285.3 | 50.1% | 315.2 | 451.4 | 30% |

| A17 | 456.9 | 216.4 | 299.7 | 51.9% | 339.6 | 509.9 | 33% |

| Coolant | Density | Cp | Dynamic viscosity | Thermal conductivity |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| kg/m3 | J/kg*K | Pa*s | W/m*K | |

| He | 5.6376 | 5188.7 | 3.50E-05 | 0.27759 |

| CO2 | 63.09 | 1159.6 | 3.15E-05 | 0.049073 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).