1. Introduction

There are 27 bones in each hand and 26 bones in each foot, adding up to a total of 106 bones which account for 52% of the body's 206 bones [

1]. The high number of bones and joints in these body parts is due to the essential role they play in various movements. While the hands are capable of intricate movements for writing or using tools, the bones in the feet move organically to aid in walking and exercise and to absorb impact from the body's weight.

These structural characteristics may limit the effectiveness of computer interfaces operated by the feet. However, foot-operated devices such as car pedals, door stoppers, foot switches, and foot mice have been in use since the inception of human-computer interaction (HCI) [

2], indicating the possibility of using foot-based input as a method. Recent technological advancements have led to the development of foot-based interactions that allow for direct contact between the foot and the device. With sensor technologies, the computer can recognize foot gestures and trigger specific commands [

3,

4].

This study focuses on direct foot interaction, in which users use a specific part of the foot to directly contact the foot pad while sitting. This approach to foot-based interaction is more intuitive than input by foot gesture, which requires users to remember foot gestures and mapped commands [

3,

4]. Although hands are the primary medium of human-computer interaction, feet can be used as inputs for secondary tasks while the hands are occupied. The feet have demonstrated potential as a tool for less precise tasks compared to hands [

5,

6,

7]. If feet can perform faster and more sophisticated tasks, the frequency and likelihood of using them for human-computer interaction will increase.

The goal of this study is to find ways to improve the speed and accuracy of the task of clicking the touchpad with the feet while sitting. Specifically, the study examines the influence of the slope of the foot touchpad, the moving direction of the foot, and the touch part of the foot on the accuracy and speed of the touch when a specific point (target) is touched. The results of this research are expected to provide guidance for the design of direct foot-based interfaces.

2. Related Works

2.1. Movement time and reponse time of foot

Foot movement time has been measured to compare with hand movement time [

8,

9,

10,

11]. Input device for the hands was not always same with input device for foot. Drury [

8] and Hoffmann [

9] measured foot movement times by tapping on physical blocks on the floor without using any specific input device. However, Springer and Siebes [

10] compared a foot joystick to a hands-operated mouse in a target selection task, while Garcia et al. [

11] compared a foot joystick and hand trackball. Despite the differences in input devices used, the results of these studies indicate that foot movement time is 1.58 to 2.32 times longer than hand movement time, and errors occur approximately 1.5 times more often when using the feet.

Furthermore, we also reviewed previous studies on the foot and hand reaction times. Simonen et al. [

12] conducted a study on the reaction times of the hands and feet. The decision time appeared to be slightly faster in the hand than in the foot during testing of simple reaction time. However, during the test of mutiple choice reaction time, the decision time was similar for both hands and feet. Another study found that the hands had much shorter reaction times in simulated microsurgery tests, and in the open-ended questionnaire after the experiment, 91.5% of the subjects preferred to use the hand switch [

13]. Our findings in previous studies suggest that while foot-based interaction may not be as efficient as hand-based interaction, improving the design of foot interfaces may enhance their effectiveness in certain scenarios.

2.2. Effects of three factors considered in this study

In order to enhance the efficacy of foot-based interaction as a viable alternative to hand-based interaction, this study aims to explore more effective alternatives by considering three factors: the movement direction of the foot, the touch area of the foot used for pointing to specific points on the foot touchpad, and the slope angle of the foot touchpad. Several previous studies on these factors is presented below.

Numerous studies have investigated the relationship between movement time and movement direction, with a focus on hand movements [

14,

15,

16,

17,

18,

19]. However, these studies have produced inconsistent results. For example, MacKenzie and Buxton found that target acquisition times on the horizontal and vertical axes were faster than those on the diagonal axis [

16]. In contrast, Whisenand and Emurian reported that pointing at horizontal targets was more efficient than pointing at vertical targets, across all 45° angles from 0° to 360° [

19]. Similarly, Thompson et al. found that horizontal pointing was generally faster and more accurate than vertical pointing across eight different movement directions [

18]. Grossman and Balakrishnan also investigated movement time in five different directions (0° to 90° at 22.5° intervals) and found that movement time was faster when one of the target dimensions was parallel to the direction of movement [

17]. This suggests an interaction between movement direction and target shape.

However, research exploring the impact of different foot movement directions on movement time is limited in comparison to studies on hand movement direction. Previous studies have primarily measured foot movement times in only one direction, such as horizontal [

8,

9,

20,

21,

22] and vertical [

23]. One study investigated angular foot movement, in which the heel of the foot was fixed and the toe was rotated to touch the target [

24]. Nevertheless, studies examining foot movement time while changing direction are particularly lacking. A recent study by Chan and Hoffmann compared foot movements in horizontal and vertical directions in both sitting and standing postures [

25]. The results showed that movement time was significantly shorter in the standing posture compared to sitting posture, and foot movement time was significantly shorter in the horizontal direction compared to the vertical direction. Notably, no studies have explored the effect of diagonal movement directions on foot movement, which is addressed in the current study.

Table 1 discribes the previous studies on the effect of movement direction on the movement time.

One question is whether accurate touch can be achieved when using a specific part of the foot to touch a target point. When using a finger to touch an interface, it can be challenging to hit a target accurately because the finger or hand can obstruct the point to be touched on the display, and users may not know which part of the fingertip touches the display first [

26]. To address this issue, many methods have been proposed, such as extending feedback beyond covering the fingers [

27], providing users with a copy of the hidden area under their finger [

28,

29,

30], remotely manipulating objects to avoid occluding them [

31], and setting the activation area in consideration of the differences between the physically visible area and the actual touched area [

32,

33,

34].

Similar to the hands, occlusion of the feet or toes can also occur. Compared to the hands, the feet are larger, and the ability for detailed movements is lower, making this occlusion phenomenon more pronounced. However, research on the occlusion of toes or feet is not as active. This study aims to investigate the frequency of this difficulty when touching the touchpad with different parts of the foot, namely the big toe, index toe, and ball. The touch speed and accuracy of each part will be measured.

The angle of the slope of the foot touchpad on the floor could impact input performance, but studies on this topic have mainly focused on hand-based interaction. Studies on keyboards, which are a primary input device, have been conducted for a long time to enhance their design and usability [

35,

36,

37,

38]. Using a keyboard with an inappropriate slope may result in WMSD (work-related musculoskeletal disorders) and lower input performance [

39,

40,

41]. Rempel et al. compared and evaluated six types of commercially available keyboards with different slope angles [

42]. When using a keyboard with a slope of 0 degrees, wrist extension ranged from 2.4 degrees to 13.1 degrees for the right hand and from 3.6 degrees to 12.8 degrees for the left hand. In contrast, the -7 degree keyboard design reduced wrist extension to -3.1 degrees for the right hand and -3.2 degrees for the left hand. Nash et al. conducted an experiment where the keyboard slope angle was changed between -16 degrees and +6 degrees in both sitting and standing positions [

43]. They found that the optimal slope angle was -4 degrees to -12 degrees in a sitting position and -9 degrees to -12 degrees in a standing position. This led to minimized wrist extension, increased typing performance, and higher user satisfaction.

There are relatively few studies on the slope of foot input devices compared to hand input devices. Konz et al.'s study investigated the slope of foot pedals in cars through two experiments [

44]. In the first experiment, the optimal pedal slope angle was reported to be between 30 to 40 degrees, and in the second experiment, it was between 30 and 45 degrees.

Table 2 discribes the previous studies on the effect of movement direction on the movement time.

Previous did not focus on touching the footpad using a specific part of the foot. In this study, we aim to investigate the effect of changing the slope of the footpad on foot movement time and accuracy when using different parts of the foot to touch a specific point.

Table 2.

Summary of previous research on the slope of input devices.

Table 2.

Summary of previous research on the slope of input devices.

| Foot/Hand |

Input Device |

Authors |

| Hand |

Keyboard |

Simoneau and Marklin (2001) [40]

Simoneau, et al. (2003) [41]

Rempel, et al. (2007) [42]

Nash, et al. (2021) [43] |

| Foot |

Foot padel |

Konz, et al, (1971) [44] |

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Participants

The participants in the experiment were 12 college students (3 females, 9 males), and their ages ranged from 23 to 27 years old, with an average age of 24.8 years. They had no difficulty in touching the foot touch pad in the sitting position, and the average foot size was 256.7 mm and ranged from 225 mm to 285 mm.

3.2. Apparatus and Measurement

Participants were aksed to click a specific point on the foot touchpad with their right foot after pressing the foot start button.

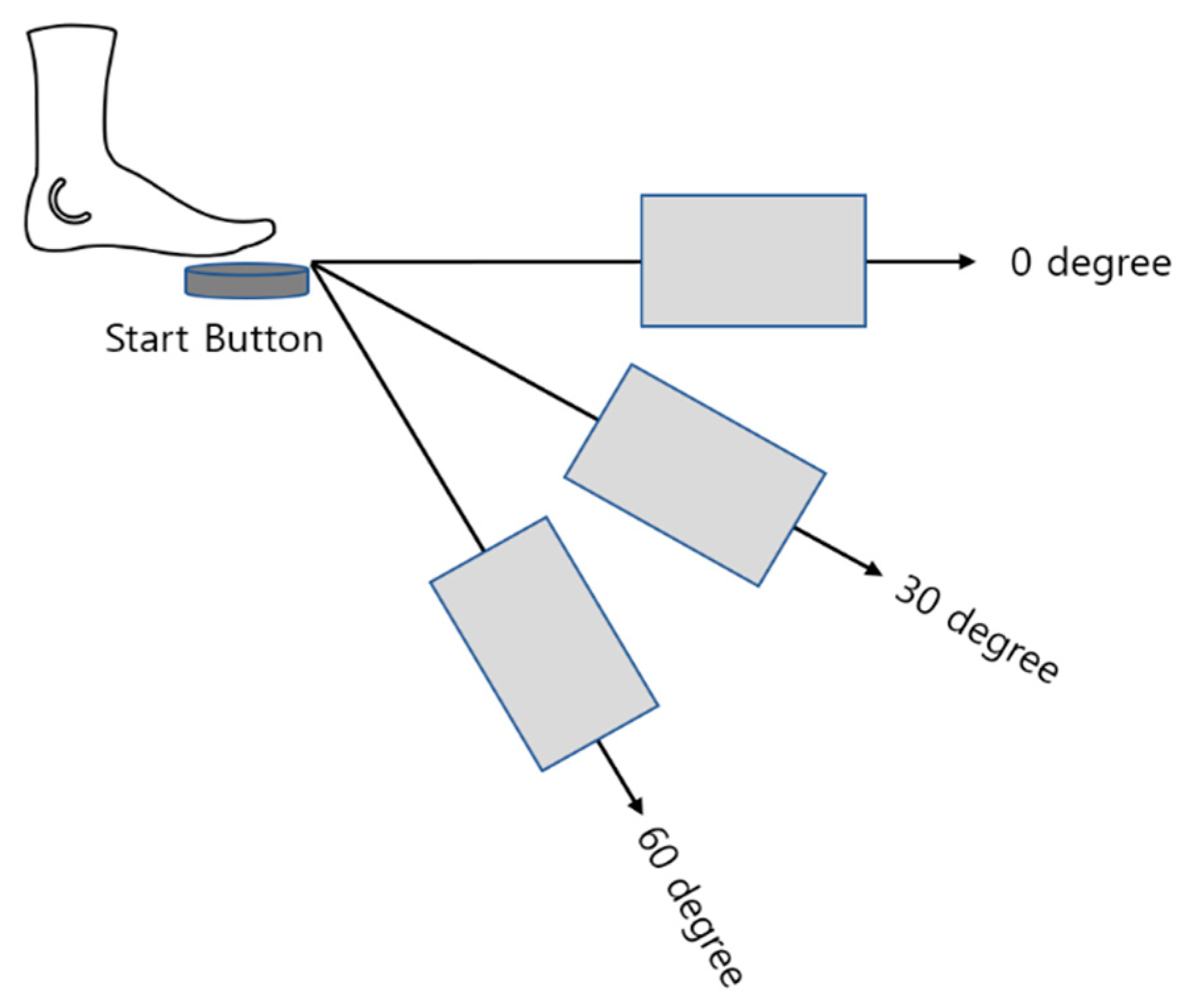

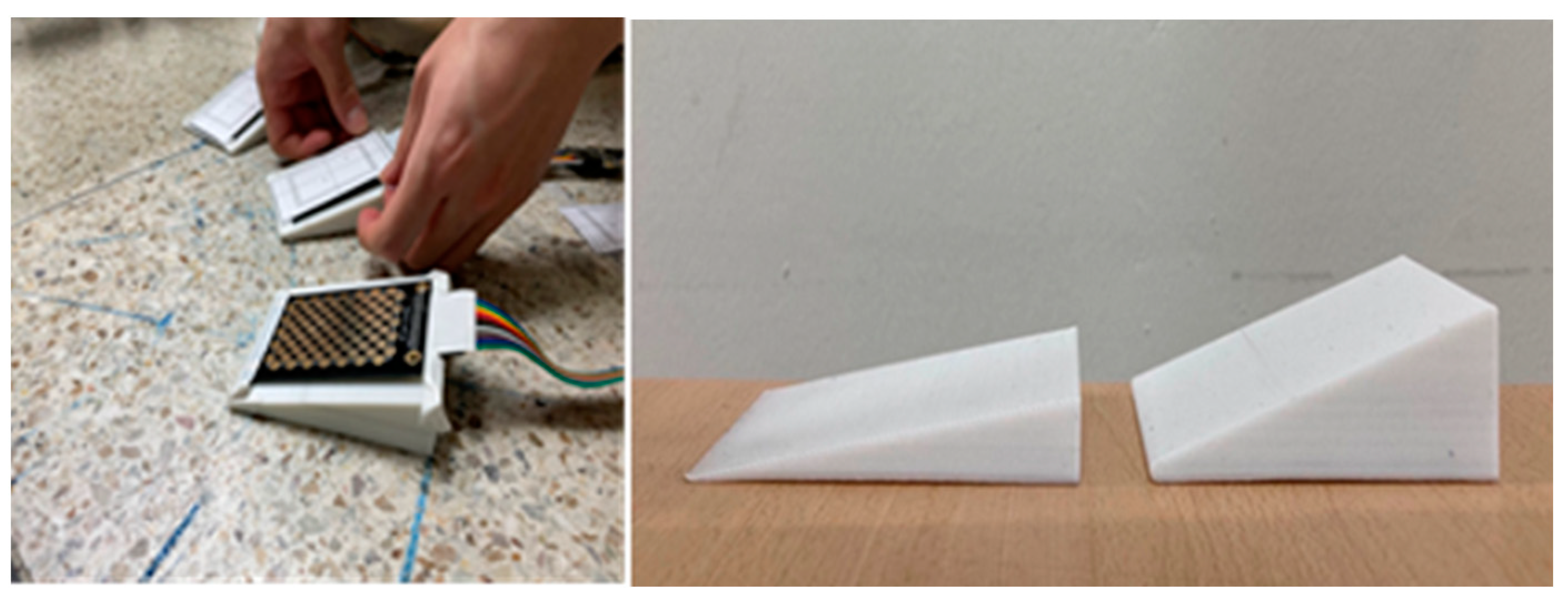

Figure 1 iluustrates the start button and possible positions of touchpad. The distance between the start button and touchpad was individually determined by each participant based on the length of their legs and feet, ensuring a comfortable clicking distance. The touchpads were placed at 0, 30, and 60 degrees with respect to the right foot, forming a circle with a constant radius from the start button as the origin.

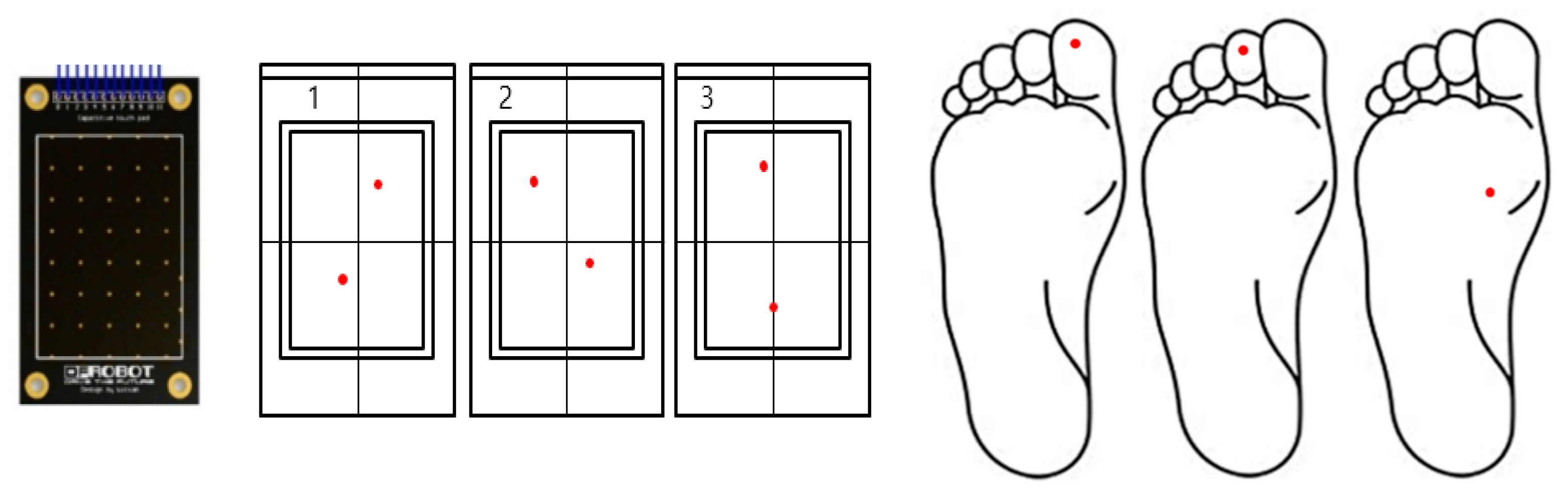

The study aimed to measure foot movement time and pointing error of participants while clicking a specific point on the foot touchpad with a designated part of the foot. The foot movement time was calculated as the time interval between pressing the start button and clicking the foot touchpad. Pointing error was defined as the distance between the center of the target point and the center of the touch point generated when touching a specific part of the foot. The specific point on the touchpad and the designated part of the foot were marked with red circles for accuracy measurement, as shown

Figure 2. The touchpad's slope was set at 7 and 15 degrees, as shown in

Figure 3.

3.3. Experimental Design

A within-subject design was employed in this experiment, with each participant completing 10 repetitions of each of the 18 experimental conditions. Three independent variables were manipulated: the part of the foot used for clicking the touchpad (Big toe, Index toe, and Ball), the direction of foot movement (0 degrees, 30 degrees, and 60 degrees to the right), and the slope of the touchpad (7 degrees and 15 degrees). Dependent variables included foot movement time and accuracy. Prior to each trial, the experimenter indicated which of the two dots on the touchpad the participant was to touch. The participant then waited with their right foot on the start button, and initiated movement to touch the target point on the touchpad upon receiving the start signal. The order of experimental conditions was randomized to reduce order effects, and participants were given a 1-minute break every 5 minutes to minimize fatigue. Following the experiment, participants were asked to provide subjective feedback regarding the degree of burden experienced by each part of their foot.

4. Results

4.1. Analysis of foot movement times

Three-way analysis of variance was performed on the movement time of the foot.

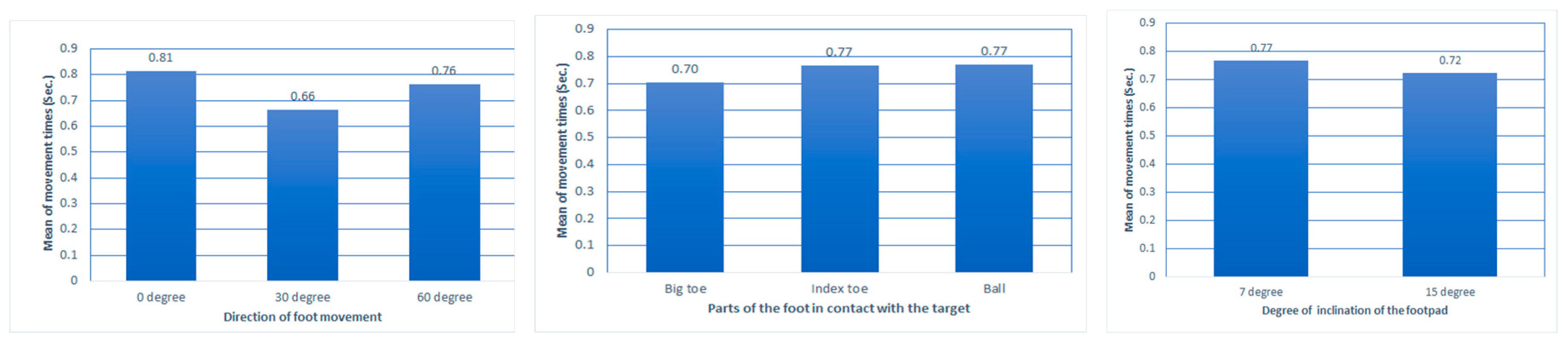

Figure 4 shows the average of the foot movement times according to the three independent variables. All three independent variables significantly affected foot movement time. Foot contact area (F(2, 2146) = 16.46, P < 0.001), foot movement direction (F(2, 2146) = 66.02, P < 0.001), and touchpad slope (F(1, 2146) = 16.93, P < 0.001). In the analysis of the foot movement time according to the part of the foot in contact with the target point, the average movement time was the fastest at 0.703 sec. in the case of contact using the big toe. As a result of the post hoc test by the Turkey test, there was no difference between index toe and ball, and big toe had a shorter foot movement time differentially. When the direction of movement of the feet was in the direction of 30 degrees, the average movement time was 0.664 sec., which was the fastest. As a result of the post-hoc test by the Turkey test, 1 degree, 30 degree, and 60 degree belonged to significantly different groups, respectively. The foot movement time was faster when the slope angle of the foot touchpad was 15 degrees than at 7 degrees. The average of the foot movement direction at 15 degrees was 0.724 sec.

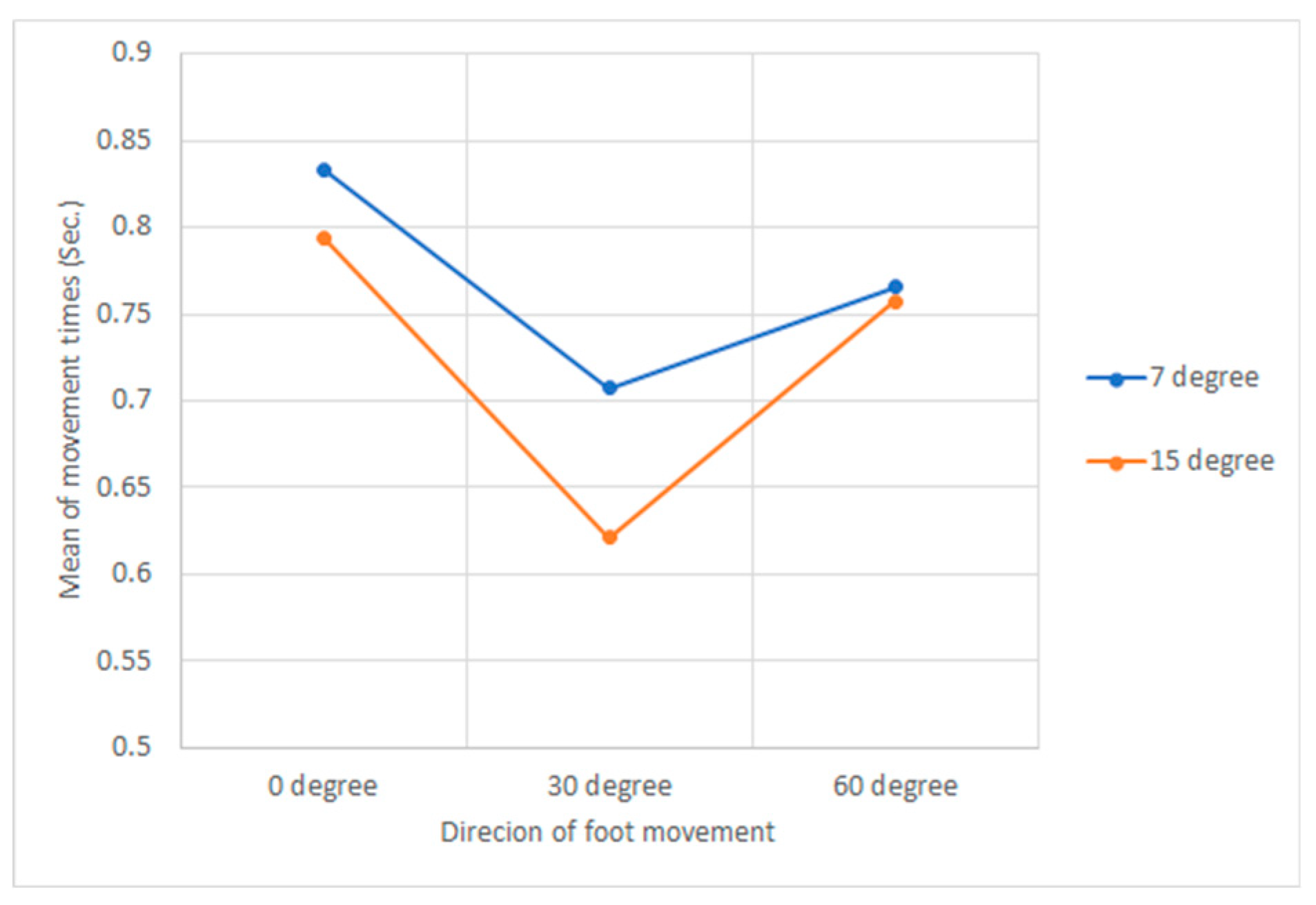

Among the three independent variables, the interaction effect on the foot movement time was significant only between the slope of the touchpad and the direction of foot movement (P < 0.001) and no significant interaction effect was found among the other factors. As shown in

Figure 5, when the direction of foot movement was 0 degrees or 60 degrees, it was less affected by the slope of the touch pad. However, when the foot movement direction was 30 degrees, the foot movement time was greatly affected by the slope of the touchpad. The average movement time was 0.612 sec., when the touchpad slope was 15 degrees and 0.707 sec., when the touchpad slope was 7 degrees, showing a large difference.

4.2. Analysis of pointing errors

A three-way analysis of variance was performed on the effect of the three independent variables on the pointing error distnace.

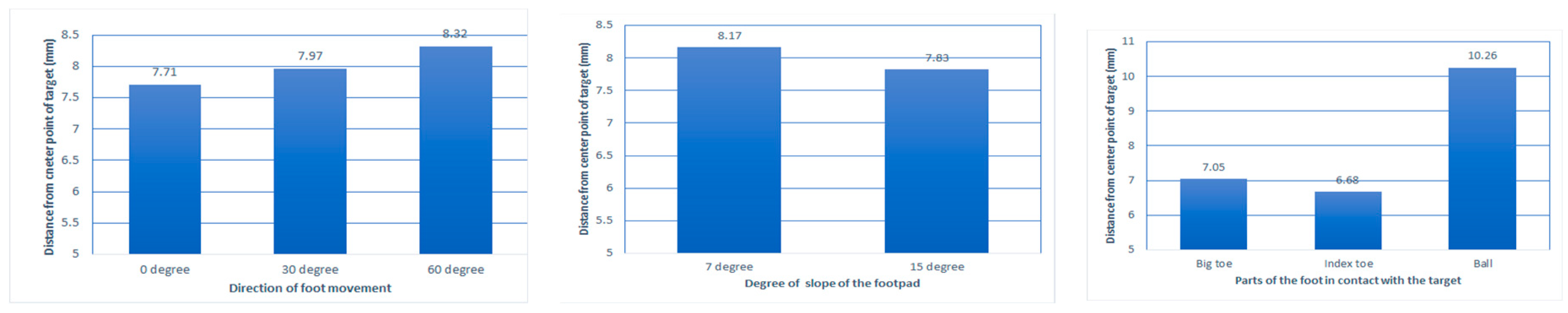

Figure 6 show average pointing error distance according to 3 independent variables. Among the three independent variables, two independent variables, the part of the foot in contact with the touchpad and foot movement direction, significantly affected the error distance; Foot contact part (F(2, 2146) =124.26, P < 0.001), foot movement direction (F(2, 2146) =3.08, P < 0.05), touchpad slope (F(1, 2146) = 2.83, P = 0.093) .

The average error distance according to the foot part in contact with the touchpad was 7.05 mm in the case of contact using the big toe, 6.68 mm in the case of using the index toe, and 10.26 mm in the case of using the ball. As a result of the post hoc test by the Turkey test, there was no significant difference in the error distance when using Big toe and Index toe, and this value was shorter than when using Ball.

The error distance according to the movement direction of the foot was 7.72 mm in the 0-degree direction, 7.97 mm in the 30-degree direction, and 8.32 mm in the 60-degree direction, and the error distance increased as the angle widened. The results of the ANOVA were significantly different depending on the angle (P = 0.046), but the results of the post-hoc test by the Turkey test showed no significant difference in the pointing error distance according to the movement direction.

Figure 6.

Main effects of the direction of foot movement (left), slope of foot touchpad (center) and the foot part in contact with target point (right) on the foot pointing error.

Figure 6.

Main effects of the direction of foot movement (left), slope of foot touchpad (center) and the foot part in contact with target point (right) on the foot pointing error.

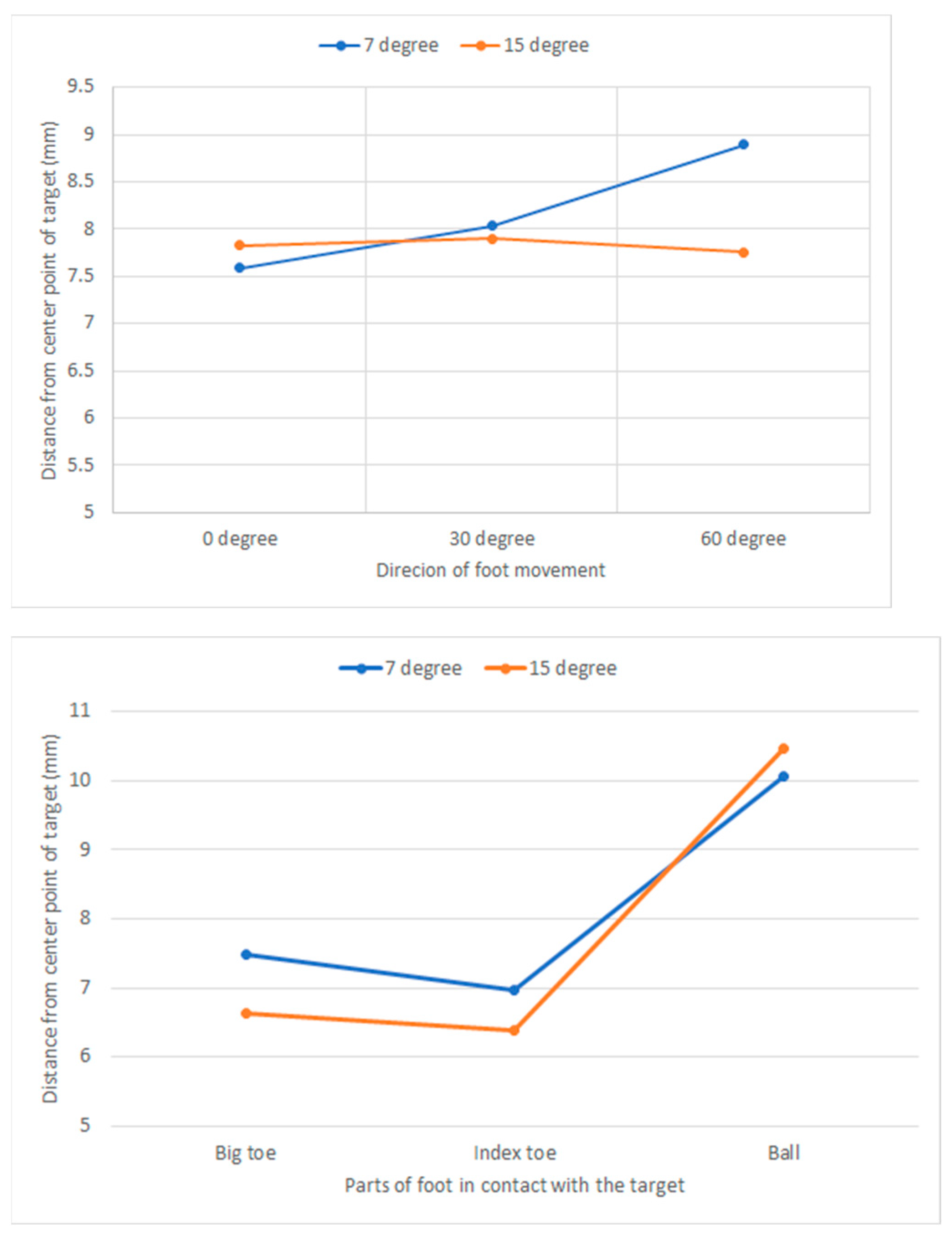

As a result of the analysis of the interaction effect between two factors in a row, a significant interaction effect on the error distance was between the part of the foot in contact with the touchpad and the slope of the touchpad (F(2, 2146 =3.08, P < 0.05) and between the direction of foot movement and the slope of the touchpad (F(2, 2146 =3.08, P < 0.05).

Figure 7 is a graph of the interaction that showed a significant interaction effect. In the interaction between the foot part contacting the touchpad and the touchpad slope, the ball part showed a longer error distance at the touchpad slope of 15 degrees (10.466 mm) than at the touchpad slope of 7 degrees (10.056 mm). On the other hand, in other parts (big toe, index toe), the error distance was shorter at the touchpad slope of 15 degrees than the touchpad slope of 7 degrees.

Looking at the interaction between the direction of foot movement and the slope of the touchpad, the error distance was much shorter at the touchpad slope of 15 degrees (7.758 mm) than that of the touchpad slope of 7 degrees (8.891 mm) in the direction of 60 degrees. However, in other moving directions (0 degree and 30 degree), the error distance was similar regardless of the touchpad slope (7 degree, 15 degree).

Figure 7.

Interaction effects between direction of foot movement and slope of touchpad, and between parts of foot in contect with the target and slope of touchpad.

Figure 7.

Interaction effects between direction of foot movement and slope of touchpad, and between parts of foot in contect with the target and slope of touchpad.

4.3. Subjective response

After all experiments were completed, a survey was conducted to investigate the physical burden and comfort experienced by participants when touching a target, and it consisted of three questions. Question 1 asked about the comfort level felt by participants according to the degree of slope of the touchpad. The results showed that most participants found the height of the 15-degree angle more comfortable than the 7-degree angle as shown in

Table 3. Question 2 measured the level of difficulty experienced by participants when using different parts of their feet to touch the target. Based on a 5-point Likert method, most participants found that using their big toe was easy, while using their index toe was very difficult or difficult, and using the ball of their foot was the most difficult, as shown in

Table 4. Finally, the third question aimed to assess the participants' perceived accuracy when touching the target. Based on a 5-point Likert method, the most common answer for the big toe was accurate, while the most frequent answer for the index toe and the ball of the foot was inaccurate, as shown in

Table 5. Overall, it seems that the survey provided useful insights into the physical burden and ease experienced by participants when interacting with the target using different parts of their feet, and can inform future designs or improvements of such targets.

5. Discussion

In this study, participants clicked the foot touchpad with their right foot in a sitting position and it was measured how accurately and quickly they pointed at a target. Foot movement performance was measured while changing three experimental conditions; foot part in contact with touchpad, touchpad slope, foot movement direction.

As for the movement direction of the foot, the saggital plane of the right foot was defined as 0 degrees, and the angle of the right foot to the right was defined as the direction of movement. The foot movement time according to the foot movement direction was shorter when the right foot was moved in the 30 degree direction than when the foot was moved in the 0 degree or 60 degree direction. The ANOVA results for pointing error showed a slightly significant difference according to the direction of movement (P = 0.046), but the results of the Turykey test did not show a significant difference. Therefore, it can be said that moving the right foot in the direction of 30 degrees is most excellent for foot movement performance. The movement time and error in the direction of 0 degree and 60 degree are said to be similar.

This result can be compared with existing studies on hand and foot movement directions. A study by Chan and Hoffmann on the direction of foot movement showed that the horizontal foot movement time was faster than the vertical foot movement time [

25]. Several studies on hand movement directions also reported that horizontal movement is faster than vertical movement, and that the closer the direction of the movement is to the horizontal, the faster the movement speed [

18,

19]. The foot movement directions set in this study are vertical (0 degree) and diagonal (30 and 60 degrees). Since horizontal foot movement was not considered in this study, it could not be compared with previous studies. However, it was found that the diagonal foot movement is faster or similar than vertical foot movement.

In the investigation of whether the target was pointed with a certain part of the foot more accurately and faster, pointing using the big toe took significantly less time than when touching with the index toe or ball. Also, when using the big toe and index toe, the pointing error was significantly smaller than when using the ball. On the other hand, in the results of the subjective response survey, participants felt less physical burden and higher perceived touch accuracy when using the Big Toe than other parts. In conclusion, it can be said that using big toe is efficient when requiring accuracy and speed of foot interaction.

When the slope angle of the touchpad was designed to be 15 degrees rather than 7 degrees, the foot movement time was significantly shorter. The pointing error according to the slope angle could not be said to be a stochastically significant difference (P = 0.093), but was slightly smaller at 15 degrees. On the other hand, in the survey of participants' subjective responses, the more comfortable slope angle was found to be 15 degrees rather than 7 degrees. The experiment in the current study was conducted by setting the slope angle of the touchpad to two levels. In future studies, it can be said that it is necessary to experiment by increasing the number of slope angle levels in order to closely examine the influence of the touchpad slope.

In the interaction analysis between the two factors, when the foot movement direction was 30 degrees, the foot movement time was noticeably shorter when the touchpad slope was 15 degrees than 7 degrees. This can be interpreted as the condition of the optimal foot movement task being a foot movement in the direction of 30 degrees with a touchpad slope of 15 degrees.

6. Conclusions

This study aimed to find an optimal work design for the foot interaction task of pointing to a touchpad with the right foot in a sitting position. The results of the study can be summarized in three points. First, it can be said that the movement direction of the foot is most effective in terms of accuracy and speed when moving in the direction of 30 degrees. The 0-degree direction and the 60-degree direction showed similar performance, and could be equally considered as the next best solution. Second, Big Toe is most suitable for the part of the foot that directly touches the touchpad. When using the big toe, it was the best in terms of foot movement speed, accuracy, and subjective satisfaction. The next best thing was to use index toe, and using ball was the worst of the three alternatives. Third, when the slope of the touchpad is 15 degrees rather than 7 degrees, it can be said that the efficiency of the foot movement work is higher. The results of this study can be used as guidelines for foot interface design.

Author Contributions

The following statements should be used “Conceptualization, S-K.H.; methodology, S-K.H.; software, S-W.K.; validation, S-K.H. and S-W.K.; formal analysis, S-K.H.; data curation, S-K.H.; writing—original draft preparation, S-K.H.; writing—review and editing, S-W.K.; visualization, S-K.H.; supervision, S-K.H.; funding acquisition, S-K.H. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.”

Funding

This research was funded by grants from National Research Foundation of Korea, Grant number #NRF-2022R1F1A1076475.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

References

- Steele, D.G.; Bramblett, C.A. The anatomy and biology of the human skeleton. Texas A&M University Press. 1988.

- English, W.; Engelbart, D.; Berman, M. Display-Selection Techniques for Text Manipulation. IEEE Trans. Hum. Factors Electron. 1967, HFE-8, 5–15. [CrossRef]

- Felberbaum, Y.; Lanir, J. Better understanding of foot gestures: An elicitation study. In Proceedings of the 2018 CHI Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems, 2018, 1–12. [Google Scholar].

- Wobbrock, J.O.; Morris, M.R.; Wilson, A.D. User-defined gestures for surface computing. In Proceedings of the SIGCHI Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems, 2009, 1083–1092. [Google Scholar].

- Pakkanen, T.; Raisamo, R. Appropriateness of foot interaction for non-accurate spatial tasks. In CHI ’04 Extended Abstracts on Human Factors in Computing Systems, 2004, 1123–1126. [CrossRef]

- Horodniczy, D.; Cooperstock, J.R. Free the hands! Enhanced target selection via a variable-friction shoe. In Proceedings of the 2017 CHI Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems, 2017, 255–259. [Google Scholar].

- Schöning, J.; Daiber, F.; Krüger, A.; Rohs, M. Using hands and feet to navigate and manipulate spatial data. In CHI’09 Extended Abstracts on Human Factors in Computing Systems, 2009, 4663–4668. [Google Scholar].

- Drury, C.G. Application of Fitts' Law to Foot-Pedal Design. Hum. Factors: J. Hum. Factors Ergon. Soc. 1975, 17, 368–373. [CrossRef]

- Hoffmann, E.R. A comparison of hand and foot movement times. Ergonomics 1991, 34, 397–406. [CrossRef]

- Springer, J.; Siebes, C. Position controlled input device for handicapped: Experimental studies with a footmouse. Int. J. Ind. Ergon. 1996, 17, 135–152. [CrossRef]

- Garcia, F.P.; Vu, K.-P. L. Effects of practice with foot-and hand-operated secondary input devices on performance of a word-processing task. Human Interface and the Management of Information. Designing Information Environments: Symposium on Human Interface 2009, Held as Part of HCI International 2009, San Diego, CA, USA, July 19-24, 2009, Procceedings, Part I, 505–514.

- Simonen, R.L.; Battié, M.C.; Videman, T.; Gibbons, L.E. Comparison of Foot and Hand Reaction Times among Men: A Methodologic Study Using Simple and Multiple-Choice Repeated Measurements. Percept. Mot. Ski. 1995, 80, 1243–1249. [CrossRef]

- Pfister, M.; Lue, J.-C.L.; Stefanini, F.R.; Falabella, P.; Dustin, L.; Koss, M.J.; Humayun, M.S. Comparison of Reaction Response Time between Hand and Foot Controlled Devices in Simulated Microsurgical Testing. BioMed Res. Int. 2014, 2014, 1–8. [CrossRef]

- Appert, C.; Chapuis, O.; Beaudouin-Lafon, M. Evaluation of pointing performance on screen edges. In Proceedings of AVI’08, ACM Press, 2008, 119–126.

- Boritz, J.; Booth, K.S.; Cowan, W.B. Fitts’ law studies of directional mouse movement. In Proceedings of Graphics Interface’91, Canada, 1991, 216–223. [Google Scholar].

- MacKenzie, I.S.; Buxton, W. Extending Fitts’ law to two-dimensional tasks. In Proceedings of CHI’92, ACM Press, 1992, 219–226.

- Grossman, T.; Balakrishnan, R. A probabilistic approach to modeling two-dimensional pointing. ACM Trans. Comput. Interact. 2005, 12, 435–459. [CrossRef]

- Thompson, S.; Slocum, J.; Bohan, M. Gain and Angle of Approach Effects on Cursor-Positioning Time with a Mouse in Consideration of Fitts' Law. 2004, 48, 823–827. [CrossRef]

- Whisenand, T.; Emurian, H. Analysis of cursor movements with a mouse. Comput. Hum. Behav. 1999, 15, 85–103. [CrossRef]

- Hoffmann, E.R. Accelerator-to-brake movement times. Ergonomics 1991, 34, 277–287. [CrossRef]

- Chan, A.H.S.; Ng, A.W.Y. Lateral Foot-Movement Times in Sitting and Standing Postures. Percept. Mot. Ski. 2008, 106, 215–24. [CrossRef]

- Chan, A.O.K.; Chan, A.H.S.; Ng, A.W.Y.; Luk, B.L. A preliminary analysis of movement times and subjective evaluations for a visually-controlled foot-tapping tasks on touch pad device. In Proceedings of the International Multi-Conference of Engineers and Computer Scientists, March 17-19, Hong Kong, 2010, Vol. 3, 1968-1970. [Google Scholar].

- Drury, C.G.; Woolley, S.M. Visually-controlled leg movements embedded in a walking task. Ergonomics 1995, 38, 714–722. [CrossRef]

- Park, J.-E.; Myung, R.-H. Fitts' Law for Angular Foot Movement in the Foot Tapping Task. J. Ergon. Soc. Korea 2012, 31, 647–655. [CrossRef]

- Chan, A.H.; Hoffmann, E.R. Effect of movement direction and sitting/standing on leg movement time. Int. J. Ind. Ergon. 2015, 47, 30–36. [CrossRef]

- Holz, C.; Baudisch, P. The generalized perceived input point model and how to double touch accuracy by extracting fingerprints. In Proceedings of the SIGCHI Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems, 2010, 581–590.

- Shen, C.; Ryall, K.; Forlines, C.; Esenther, A.; Vernier, F.D.; Everitt, K.; Wu, M.; Wigdor, D.; Morris, M.R.; Hancock, M.; et al. Informing the Design of Direct-Touch Tabletops. IEEE Comput. Graph. Appl. 2006, 26, 36–46. [CrossRef]

- Vogel, D.; Baudisch, P. Shift: a technique for operating pen-based interfaces using touch. In Proceedings of CHI'07, ACM 2007, 657-666. [Google Scholar].

- Käser, D.P.; Agrawala, M.; Pauly, M. FingerGlass: efficient multiscale interaction on multitouch screens. In Proceedings of CHI'11, ACM 2011, 1601-1610. [Google Scholar].

- Freeman, D.; Benko, H.; Morris, M.R.; Wigdor, D. ShadowGuides: visualizations for in-situ learning of multitouch and whole-hand gestures. In Proceedings of ITS'09, ACM, 2009, 165–172. [Google Scholar].

- Wigdor, D.; Benko, H.; Pella, J.; Lombardo, J.; Williams, S. Rock & rails: extending multi-touch interactions with shape gestures to enable precise spatial manipulations. In Proceedings of CHI'11, ACM, 2011, 1581–1590. [Google Scholar].

- Im, Y.; Kim, T.; Jung, E.S. Investigation of Icon Design and Touchable Area for Effective Smart Phone Controls. Hum. Factors Ergon. Manuf. 2014, 25, 251–267. [CrossRef]

- Jung, E.S.; Im, Y. Touchable area: An empirical study on design approach considering perception size and touch input behavior. Int. J. Ind. Ergon. 2015, 49, 21–30. [CrossRef]

- Kwon, S.; Lee, D.; Chung, M.K. Effect of key size and activation area on the performance of a regional error correction method in a touch-screen QWERTY keyboard. Int. J. Ind. Ergon. 2009, 39, 888–893. [CrossRef]

- Honan, M.; Serina, E.; Tal R.; Rempel D. Wrist postures while typing on a standard and split keyboard. In Proceedings of the Human Factors and Ergonomics Society 39th Annual Meeting, 1995, 366–368. [Google Scholar].

- Kroemer, K.H.E. Human Engineering the Keyboard. Hum. Factors: J. Hum. Factors Ergon. Soc. 1972, 14, 51–63. [CrossRef]

- Nakaseko, M.; Grandjeann, E.; Hunting, W.; Gierer, R. Studies on ergonomically designed alphanumeric keyboards. Hum. Factors, 1985, 27, 175–187. [Google Scholar].

- Zipp, P.; Haider, E.; Halpern, N.; Rohmert, W. Keyboard design through physiological strain measurements. Appl. Ergon. 1983, 14, 117–122. [CrossRef]

- Hedge, A.; Powers, J.R. Wrist postures while keyboarding: effects of a negative slope keyboard system and full motion forearm supports. Ergonomics 1995, 38, 508–517. [CrossRef]

- Simoneau, G.G.; Marklin, R.W. Effect of computer keyboard slope and height on wrist extension angle.. Hum. Factors: J. Hum. Factors Ergon. Soc. 2001, 43, 287–298. [CrossRef]

- Simoneau, G.G.; Marklin, R.W.; E Berman, J. Effect of Computer Keyboard Slope on Wrist Position and Forearm Electromyography of Typists Without Musculoskeletal Disorders. Phys. Ther. 2003, 83, 816–830. [CrossRef]

- Rempel, D.; Barr, A.; Brafman, D.; Young, E. The effect of six keyboard designs on wrist and forearm postures. Appl. Ergon. 2007, 38, 293–298. [CrossRef]

- Nash, H.; Nayak, G.K.; Thota, J.; Alsowaidi, M.; Alsowaidi, H.; Urbanic, J.; Kim, E. Effect of Computer Keyboard Slope on Upper Limb Postures at Sitting and Standing ComputerWorkstations : A Pilot Study. In Proceedings of the Human Factors and Ergonomics Society Annual Meeting, 2021, 65, 1235–1239. [CrossRef]

- Konz, S.; Wadhera, N.; Sathaye, S.; Chawla, S. Human Factors Considerations for a Combined Brake-Accelerator Pedal. Ergonomics 1971, 14, 279–292. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).