1. Introduction

Loran-C system is a low-frequency (LF) ground-based navigation system developed by the US Navy for military purposes in the 1950s based on the hyperbolic positioning principle [

1,

2]. The enhanced Loran (eLoran) system is an upgrade version of Loran-C system. With many advantages such as wide coverage, high stability and strong anti-interference ability, eLoran system has become a reliable backup for global navigation satellite system (GNSS), and will be combined with GNSS to further improve the national satellite-terrestrial integrated positioning, navigation and timing (PNT) system [

3,

4].

In order to improve the timing accuracy of the eLoran system, it is necessary to accurately measure the propagation delay. However, the propagation delay is time-varying, which will be analyzed in detail in the following sections. Currently, the most effective method is to aggregate the fluctuations caused by various factors into the

ASF fluctuation term, develop high-precision

ASF grid map, and provide delay correction services for users through

ASF interpolation [

5,

6]. The basis of this method is the precise prediction of the signal propagation delay and

ASF correction values of grid vertices. Fluctuations of various meteorological factors such as temperature, humidity, precipitation, etc., will cause different changes in conductive characteristics along the propagation path, and may lead to accumulated propagation delay measurement errors even up to the microsecond level, seriously affecting the accuracy of

ASF correction [

7]. Therefore, studying the impact of various meteorological factors on eLoran signal propagation delay fluctuation is the key to accurately establish propagation delay prediction model, which is of great significance for improving the service quality of eLoran system.

In the research field of long-wave propagation delay, it is mainly divided into the study of the calculation model of propagation delay from the terrain, and the exploration of time-varying characteristic and correction method of ASF value from the time.

The early theoretical calculation of LF groundwave propagation was based on smooth flat ground channel model [58–66]. In 1909, Sommerfeld deduced an expression for the field integral of a vertical electric dipole on a uniform flat surface [

8]. Based on this theory, scholars from all over the world have carried out a lot of relevant studies over the years. In 1945, Fock transformed and approximated the spherical harmonic series expression of the spherical groundwave field derived by Watson [

9], which improved the convergence rate of the series and was more suitable for engineering applications, namely the Fock diffraction formula [

10]. For smooth segmented uneven ground, the main methods include Wait integral formula [

11], wave-mode conversion method [

12], and Millington empirical formula widely used in engineering calculations [

13]. For irregular and uneven ground, the evolutionary calculation methods mainly include parabolic equation (PE) method [

14], integral equation method [

15] and finite different time domain (FDTD) algorithm [

16]. The above methods all have their important theoretical guidance and practical application value in different applicable environments.

In terms of time-varying characteristics of propagation delay, as early as 1985, McCollough et al. first discovered the seasonal variation of propagation delay through Loran-C observation data in the Gulf of Mexico, and preliminarily discussed its impact [

17]. In 1986, Ma made a study on the seasonal variation of ground conductivity in different regions of China and its influence on LF groundwave propagation [

18]. In 1991, Ren analyzed the influence of meteorology on the prediction of signal propagation in the Northeast Sea working area of Loran-C [

19].

In recent years, with the increasing demand for the timing and positioning accuracy of eLoran system in various countries, a lot of research work has emerged on the time-varying characteristics of propagation delay and the

ASF correction method. Yang et al. analyzed the correlation between daily variations of temperature and humidity and propagation delay, proposed a compensation scheme based on temperature for delay correction [

20]. Hwang et al. studied the influence of temperature and ground conductivity on the eLoran propagation delay, and corrected the

ASF by establishing a linear temperature model [

21]. Li et al. and Yang et al. respectively compared the measured propagation delay before and after heavy snow and rain, concluded that abrupt changes in meteorological factors such as temperature, humidity and precipitation are the key reasons for drastic changes in

ASF. [

22,

23]. Pu et al. and Feng et al. analyzed from the perspective of atmospheric refractive index and soil moisture content respectively, and concluded that each factor is closely related to the propagation delay changes [

24,

25]. Jia et al. obtained a conclusion that the groundwave propagation delay is larger in the day than that at night, and the fluctuation increases with distance [

26].

In 2019, Yang conducted a preliminary prediction modeling study on the short-term time-varying changes of short distance propagation delay and the fluctuations of various meteorological factors through the neural network principle [

27], which broke through the common linear correction model and was an innovative concept, but did not consider the regional changes of meteorological factors. In 2020, Wang et al. gridded the long-wave signal region and proposed a correction method based on neural network (ground conductivity, refractive index of light, temperature and humidity as inputs) [

28], which achieved certain effects, but took less meteorological factors into account.

In summary, the current research on the theoretical calculation methods of LF groundwave signal propagation delay has been relatively mature. However, the research on the time-varying characteristics of propagation delay is still limited, mostly focusing on the analysis of the relationship between weather and propagation delay, and the correction methods are mainly linear models, while the learning algorithms such as neural network models are in their infancy. Aiming at the above deficiencies this paper makes an in-depth study, and the main contributions of our study are as follows: (a) The influence of meteorological factors on different components of long-wave propagation delay (PF, SF, ASF) is theoretically analyzed quantitatively or qualitatively. (b) Through the correlation analysis of long-term measured data and theoretical analysis, seven relatively important meteorological influence factors are determined as modeling parameters. (c) Considering multiple meteorological factors and their regional changes, the prediction model based on Back-Propagation neural network (BPNN) is established, which significantly improves the accuracy of propagation delay prediction.

2. Background Principles

Each Loran-C station chain consists of a main station and 2~4 sub-stations, and has a special group repetition interval (GRI). The stations broadcast in cycles according to GRI in a certain time sequence to ensure a fixed receiving sequence within the signal coverage area [

29]. Loran-C signals are transmitted in the form of pulse groups, with 9 pulses in each pulse group of the main station and 8 pulses in each pulse group of each sub-station. The interval of the first 8 pulses in each group is 1ms, while the interval of the 9th and 8th pulses in the main station is 2ms [

30]. The main improvement of eLoran system on Loran-C is to adopt Eurofix data link technology to perform three state pulse position modulation (PPM) on the 3rd to 8th pulses of each pulse group to achieve the data information transmission function [

31,

32,

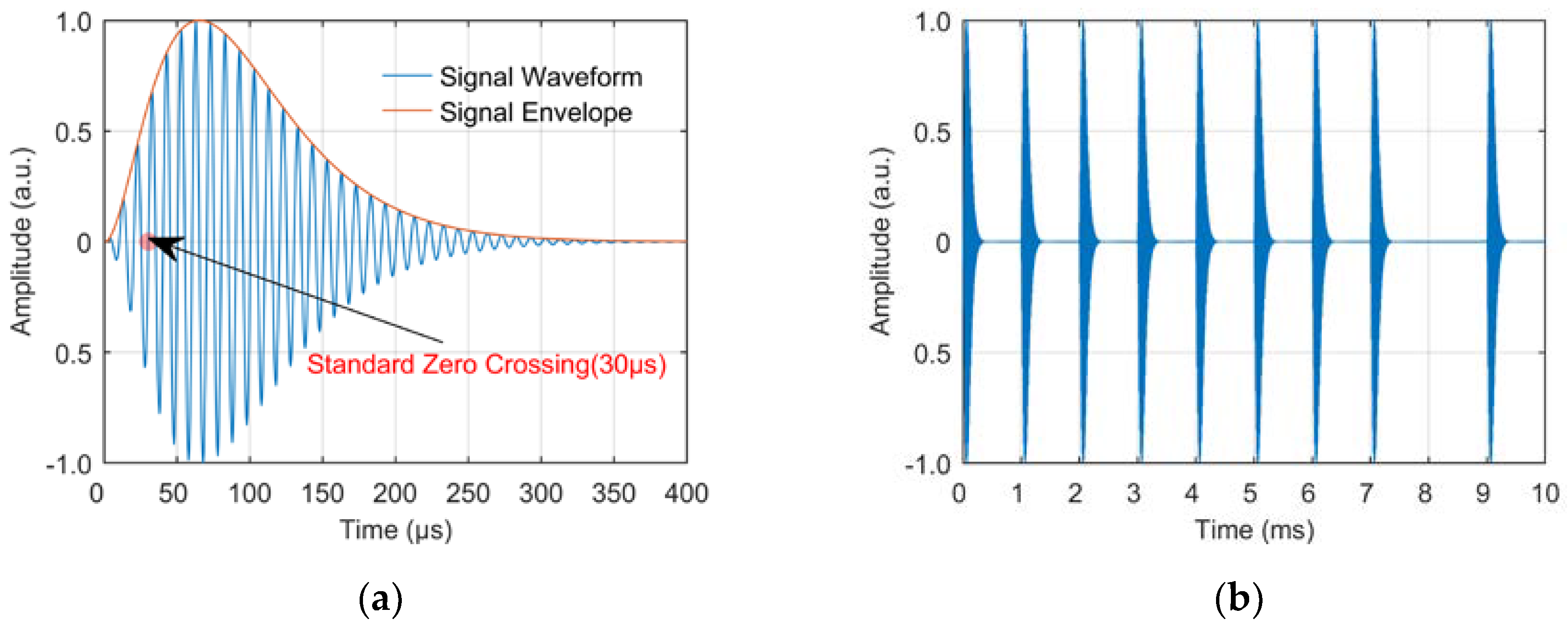

33]. The time domain waveform of standard Loran-C pulse is expressed by Formula (1) [

34], and the waveforms of standard Loran-C pulse and main station pulse group are shown in

Figure 1 below.

where

is the time in μs;

A is a normalization constant related to the peak amplitude; τ is the envelope-to-cycle difference (ECD), in µs; ,

=100 kHz is the carrier frequency, and

= 0 or π is the phase code parameter, in radians.

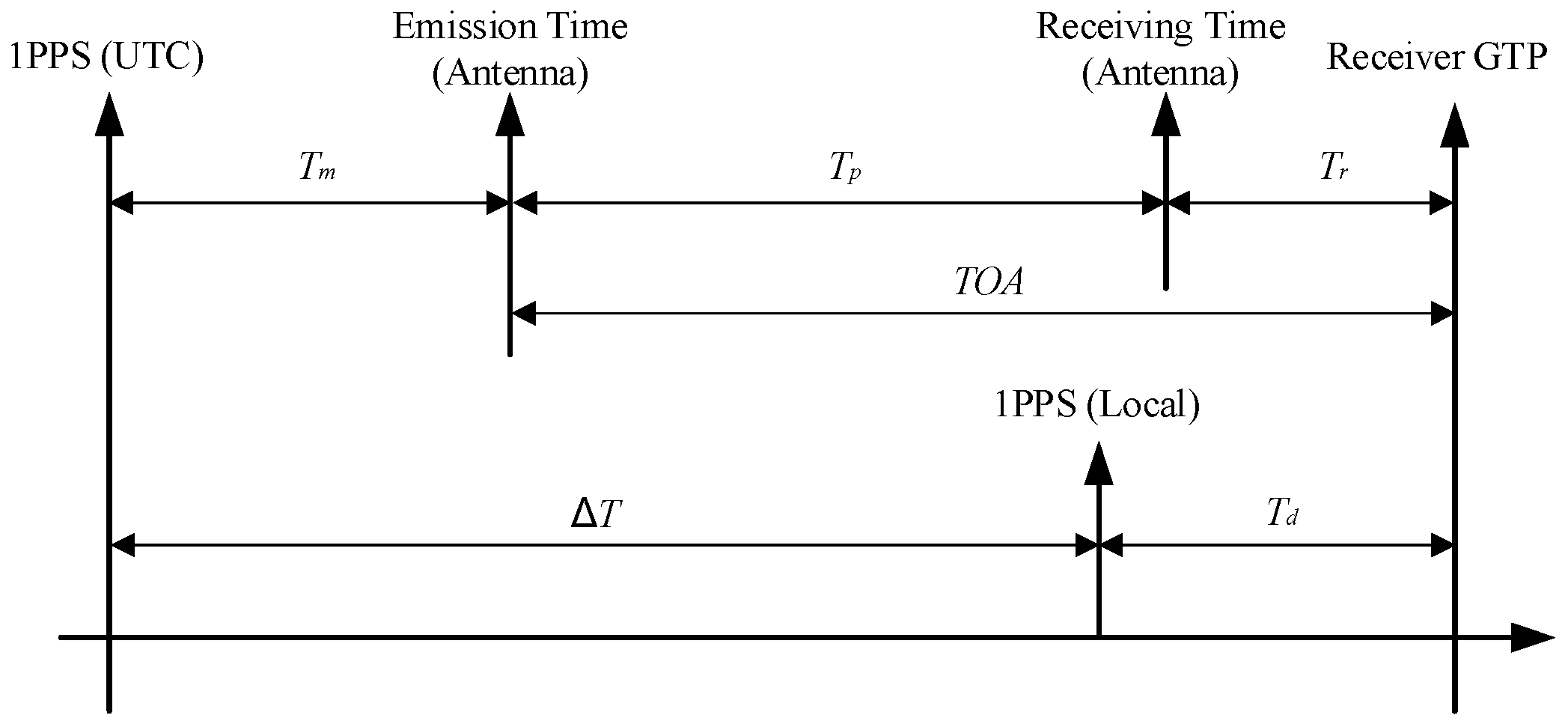

The autonomous timing function of the eLoran system is the process of synchronizing the local 1PPS signal of the receiver with the 1PPS signal of Universal Time Coordinated (UTC). The basic principle of autonomous timing is shown in

Figure 2.

According to the time axis relationship shown in

Figure 2, the process of autonomous timing is the process of calculating ∆

T, which can be expressed by the following formula:

where

Tm is the deviation between the transmit pulse and 1PPS (UTC);

Tp is the absolute propagation delay of eLoran groundwave signal from the transmitting antenna to the receiving antenna;

Tr is the delay of the receiving system;

Td is the time deviation between the receiver's local 1PPS time and the Group Trigger Pulse (GTP) time [

35].

The GTP time corresponds to the standard zero crossing of the first pulse signal of eLoran pulse group. Through the period identification process, eLoran receiver determines the GTP time, and tracks the phase of the standard zero-crossing point, then accurately measures the TOA of the groundwave signal, and finally realizes the timing and position service functions. According to Formula (2), TOA is composed of two parts of

Tp and

Tr [

36], where

Tr can be obtained by calibration. In addition,

Tm in the formula can be calculated by demodulating the time-code information, and

Td can also be measured by the internal counter of the receiver. Therefore, it can be said that the core of calculating

and realizing accurate autonomous timing is the accurate estimation of propagation delay

Tp. The expression of

Tp is as follows [

36,

37]:

where

PF is the primary factor;

SF is the secondary factor;

ASF is the additional secondary factor. The above parameters all have their characteristics and estimation methods, which will be discussed in

Section 3. Among them, since the calculation of

Tp components only considers the topographic factors, the

Tp measurement results of the fixed broadcasting stations at the same test site should be a fluctuation with a horizontal trend, taking into account the influence of some random noise or sudden jump interference.

However, through the analysis of long-term fixed-point observation data, it is found that the

Tp values present a real-time fluctuation trend.

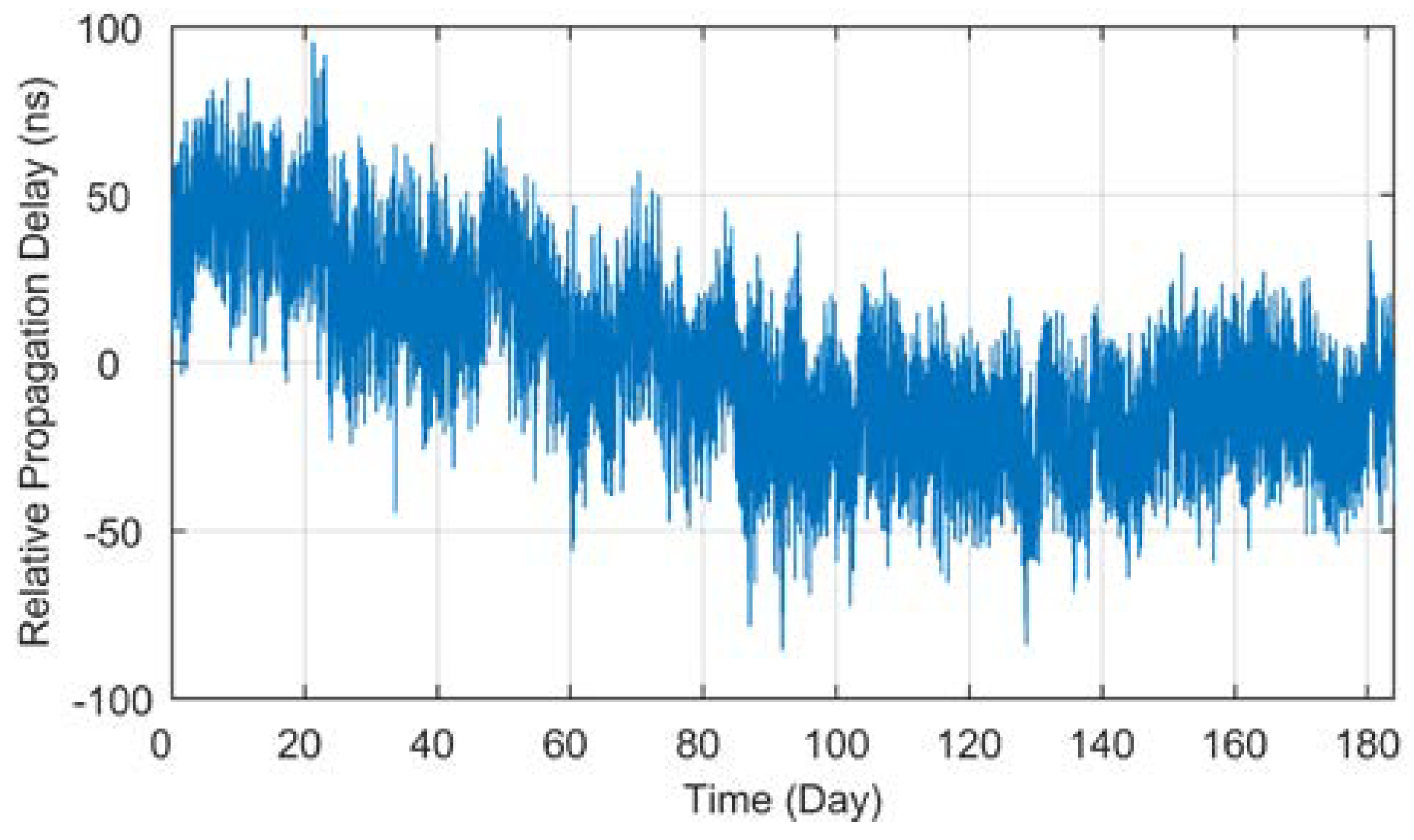

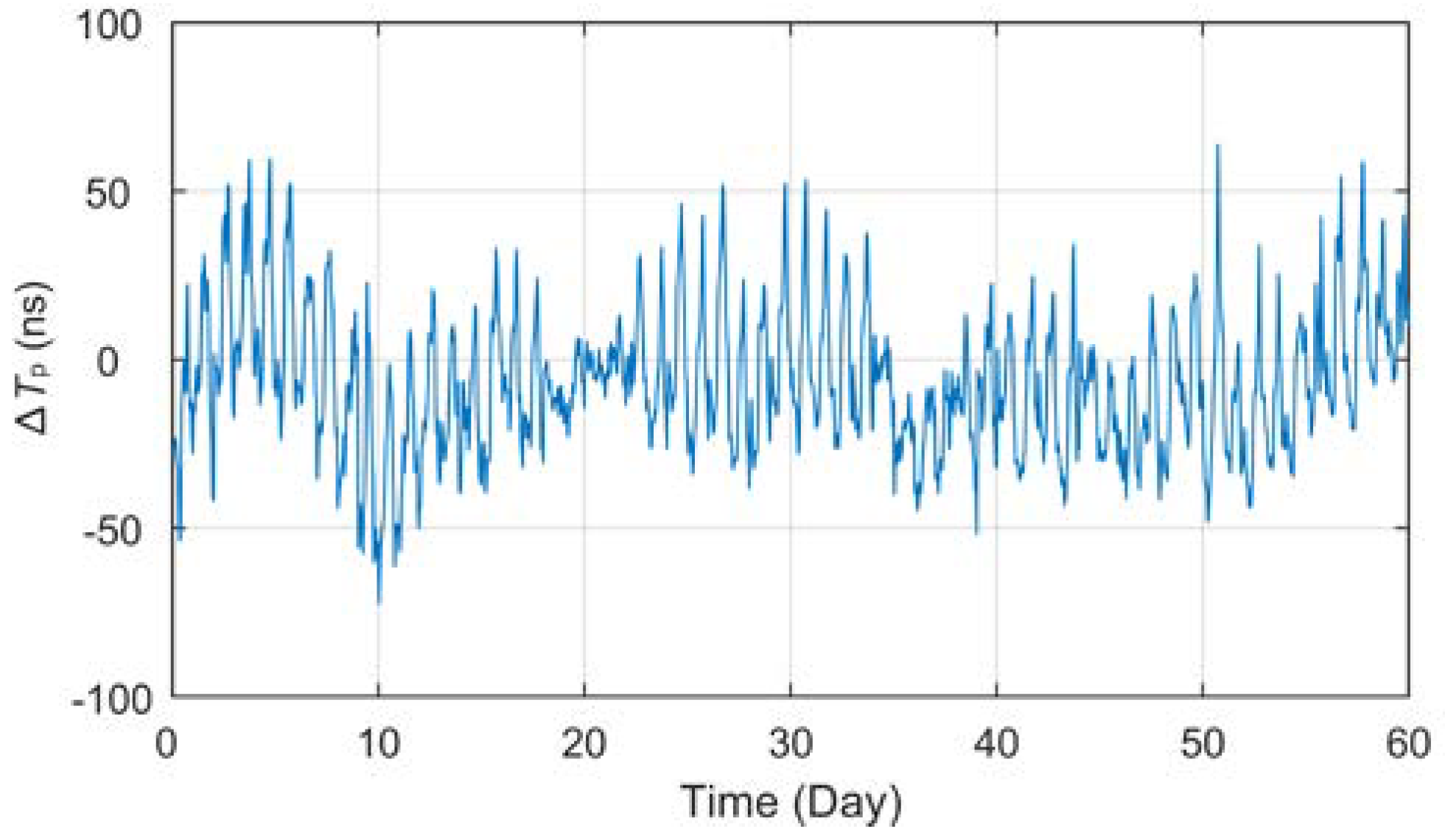

Figure 3 displays the curve of

Tp data collected at Lintong BPL long-wave monitoring station within the 184-day interval (July 1 to December 31, 2021) after the processing of outlier removal and mean value removal. It should be noted that all the

Tp data used in this paper are derived from eLoran groundwave signals broadcast by BPL long-wave timing station.

As can be seen from the

Tp curve in

Figure 3, the measured values collected at Lintong monitoring Station (71.4 km) have a slow seasonal change process of nearly 150 ns in half a year, and there also seems to be some regular fluctuation in the diurnal trend. However, the measurement results of the antenna bottom current loop obtained from the monitoring station in Pucheng show that the transmitting second signal is in a long-term stable state, the maximum jitter deviation fluctuates around ±20 ns, and the standard deviation is less than 11 ns. Therefore, it can be preliminarily judged that the measured value fluctuation of propagation delay has a certain correlation with the change of propagation medium characteristics on the fixed propagation path. In this paper, parameter ∆

Tp will be used to characterize the total relative fluctuation of such propagation delay

Tp, and as the core research object of this paper.

3. Correlation Analysis

The navigation and positioning functions of the eLoran system are based on the

Tp measurement of groundwave signals. Many previous studies have found that, on the relatively fixed groundwave propagation path, the main factors affecting the trend of ∆

Tp are various meteorological changes, including temperature, relative humidity, atmospheric pressure, etc., which may disturb the characteristics of propagation medium [

17,

18,

19,

20,

21,

22,

23,

24,

25,

26,

27,

28]. Indirectly, the

Tp value also changes.

The following will discuss the theoretical influence of meteorological fluctuations on PF, SF and ASF will be demonstrated separately in the following sections, and the complex correlations between various meteorological factors and ∆Tp will be demonstrated through sufficient measured data.

3.1. Theoretical Influence of Meteorological Factors

3.1.1. PF

The primary factor, also known as the basic time delay, refers to the signal propagation delay under the assumption of uniform air medium, which can be calculated by Formula (4). In order to reflect the spatial difference of the upper atmospheric refraction index in more detail, including the influence of altitude, temperature and humidity differences in different regions, and improve the estimation accuracy, Formula (4) can also be changed to Formula (5).

where

s is the great-circle distance of the propagation path, in km; c is the speed of light in vacuum, which is 299792.458 km/s;

n0 is the standard atmospheric refraction index, which takes

n0 = 1.000315 in China’s electromagnetic industry standard;

ns is the piecewise atmospheric refractive index related to the spatial inconsistency of the propagation path.

It can be seen from the above introduction that for fixed eLoran signal receiving points, the theoretical calculated value of

PF should be a definite value. However, considering that the atmospheric refraction index

n is a time-varying parameter in the real environment, the real-time fluctuation and compensation of

PF must be a problem worth paying studying. In order to facilitate the analysis, another parameter

N (unit: N) is commonly quoted to replace the atmospheric refractive index

n, and can be expressed as

According to the international standard atmosphere, the standard value of parameter

N0 = 315 (

n0 = 1.000315) is adopted in the electromagnetic industry in China, while

N0 = 338 (

n0 = 1.000338) is adopted in the United States. This value deviation also reflects the great differences in geological types and climate characteristics between different countries. Considering that the relative permeability in the air is approximately equal to 1, the relative dielectric constant

, electric polarization

and parameter N of the atmosphere are related as follows [

38]:

where

P is the atmospheric pressure, in hPa;

is the water vapor pressure, in hPa;

T is the temperature, in K. In addition, when the frequency of radio waves is below the UHF band, especially in the LF band, the transformation relation of

can be established [

39]. By combining this equation with equations (7) and (8), the approximate calculation formula of N can be obtained [

40]:

Table 1 shows the seasonal variation of parameter

N in different regions of China [

38]. The statistics show that the distribution of parameter

N varies greatly in different regions, and its value fluctuation is also very different, especially it is extremely sensitive to humidity changes. Due to the strong seasonal variation of humidity and temperature in the coastal and middle reaches of the Yangtze River, the value of N fluctuates obviously. However, Xinjiang, Xizang and other regions have relatively stable fluctuation of N due to the dry climate, less precipitation and little change in atmospheric humidity.

At the same time, the research shows that the diurnal variation of parameter N also has obvious regularity. Generally in the early and late hours of every day, the temperature is low and the humidity is high; in the afternoon, as the temperature rises, the humidity decreases accordingly. Therefore, the value of

N is larger in the morning and evening, and reaches its minimum around 14 pm. Generally speaking, the diurnal variation range of

N in most regions is 10~20 N under the normal weather environment [

41]. According to Formula (4), it can be calculated that for parameter N, the calculation error of

PF brought by fluctuation of 1 N is 3.3 ps/km. Therefore, at 1000 km, the

PF term may fluctuate by about 67 ns due to a variation of 20 N, while in the case of meteorological anomalies, the influence caused by the short and drastic variation of

N may even reach 200 ns.

3.1.2. SF and ASF

SF refers to the additional influence of seawater medium on signal propagation delay.

ASF refers to the additional influence of the difference of conduction characteristics of signals in land and seawater medium on the propagation delay, which is the disturbance compensation of different media based on the secondary time delay. The two parameters are essentially the same, that is, to calculate the groundwave attenuation function. The logical expression of

SF +

ASF can be described here as follows :

where

is the central angular frequency of the signal, and

is the groundwave attenuation function, which varies with distance

, and is also the core of delay measurement accuracy. When the signal propagation distance

s is relatively short,

W is generally calculated with a flat ground model, while when

s>70 km, the influence of spherical curvature of the ground on signal propagation needs to be considered [

5,

42]. The calculation formula of

W is very complex, which is related to coefficients such as

d and normalized surface impedance

q, and corresponds to different expressions respectively. For details, refer to literature [

43,

44], where only the calculation formula of

q is given directly:

where

is the ground relative dielectric constant of the propagation path;

is the ground conductivity;

is the wave number in the air;

is the equivalent earth coefficient;

is the wavelength in vacuum.

According to Formula (11) and the description in reference [

44], except for the fixed parameters, normalized surface impedance

q is the function of

,

and

n, in which the influence of

n is small, and the constant 1 is generally taken in calculations. Especially for eLoran signals in the LF band, the ground conductivity is the dominant factor affecting the propagation characteristics of groundwave. Therefore, in theoretical analysis, the attenuation function

W in Formula (10) can also be recorded as

.

Different geological types have different effects on the absorption, refraction and reflection of signal propagation. Therefore, the finer the regional division of ground conductivity and relative dielectric constant is, the more accurate the measurement of

SF (

ASF) will be. At present, there are several research on electronic digital map of ground conductivities [

45,

46], which are crucial to the refinement correction of

Tp, but they do not fully consider the real-time changes of

and

.

The factors determining the value of

and

mainly include: (1) geological structure; (2) ground vegetation; (3) underground layered structure; (4) electromagnetic wave frequency. The latter three items are generally stable, while the conductivity of geological structure is relatively easy to fluctuate due to the soil moisture and salinity caused by real-time environmental changes such as precipitation and temperature fluctuation. The research conclusion of literature [

47] points out that there is a strong positive correlation between soil water content and dielectric constant. Seasonal change of climate and diurnal temperature variation will cause the change of soil moisture. Especially in one day, due to the low temperature in the morning and evening, there is more water in the soil, and the value of

is larger. At noon, as the temperature rises and the water vapor evaporates, the soil will be slightly dry and the value of

will decrease accordingly.

Table 2 shows the conductivity characteristics of 9 typical ground types respectively. It can be seen that

and

of different geological characteristics are very different, and their time-varying characteristics will also affect the selection of equivalent earth radius parameters in the calculation formula, which will inevitably bring calculation errors and together lead to drastic changes in the calculated values of

ASF.

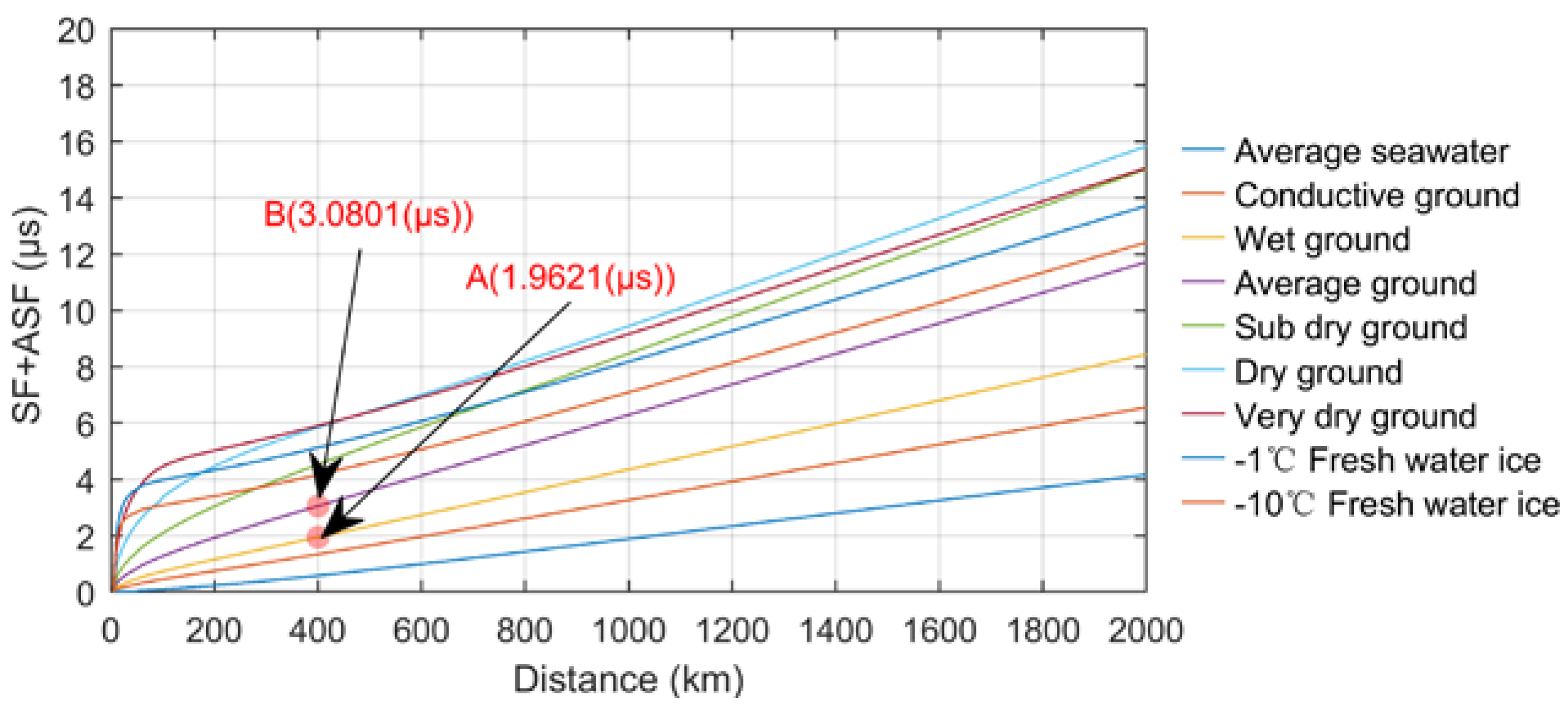

The attenuation function

W can be calculated using integral equation method, and the

SF (

ASF) change curve can also be obtained as shown in

Figure 4, which clearly shows the huge difference in attenuation function estimation caused by the characteristics of different conductive media. The numerical difference between two points A and B indicates that the difference of

ASF values between the two different ground types of average land and wet ground is more than 1μs over the propagation path of 400 km. In the real environment, heavy precipitation and other reasons are also the main reasons for real-time changes in ground conductivity and the occurrence of such delay deviations, which is unlikely to be corrected by real-time measurement of ground conductivity. It can be said that the fluctuation of

ASF is also the most important component of the overall ∆

Tp.

3.2. Anaylsis of Measured Data

There are many types of meteorological factors, which may have different effects on signal propagation. Therefore, it is necessary to first understand whether a certain parameter has an impact on

Tp and the magnitude of the impact. In the multivariate analysis of vectors of different types, correlation coefficient is generally needed. The three commonly used correlation coefficients in statistics are Pearson, Kendall and Spearman correlation coefficients [

48], all of which reflect the consistency and similarity of variation trends among different variables and have the same value range (-1~1), but also differ in application scopes and characteristics.

Pearson correlation coefficient (PCC), is a method to measure the degree of linear correlation between variables. It is defined as the quotient of the covariance and standard deviation of two variables X and Y, which is often expressed by the Greek letter . In large sample statistics, the expected value can be replaced by the sample mean according to the sample number m, and Formula (12) can be used for approximate calculation.

The principle of Spearman correlation coefficient is to use the rank of two variables for linear correlation analysis, usually expressed by the Greek letter . When calculating , it is necessary to sort the original data groups respectively by size to get the corresponding rank difference , and then calculate according to Formula (13).

Similar to

, Kendall correlation coefficient also depends on rank, and has the same requirements on data conditions. Generally, it is expressed by Greek letter

, which is used to reflect the correlation of classification variables. According to the number of harmonious and disharmonious pairs

C and

D of data group X and Y,

can be defined as the ratio of the difference between the two numbers and the total pairs as Formula (14).

Among the three types of analysis methods, PCC measures the linear relationship between variables and is very sensitive to extreme outliers. Spearman and Kendall correlation coefficient, as nonparametric methods, are both based on the rank and relative size of the observed value. They have stronger tolerance to outliers, mainly measure the relationship between variables and can describe nonlinear correlation to a certain extent, thereby are more widely applicable than PCC. Due to the complex relationship between the measured Tp and various meteorological factors, it cannot fully meet the applicable conditions of any of the above methods, and only using a certain correlation analysis method may lead to the error of ignoring the impact factors due to the possible low correlation coefficient. Therefore, in our study, the three correlation analysis methods were simultaneously used to conduct the joint analysis and mutual verification of the long-term and short-term correlation between meteorological factors and propagation delay, so as to find out more meteorological factors causing ∆Tp as much as possible.

3.2.1. Seasonal Correlation

According to the analysis in

Section 3.1, changes in meteorological factors such as temperature, relative humidity and atmospheric pressure will affect calculation factors of

Tp and indirectly lead to its fluctuation, which is verified by the measured data below.

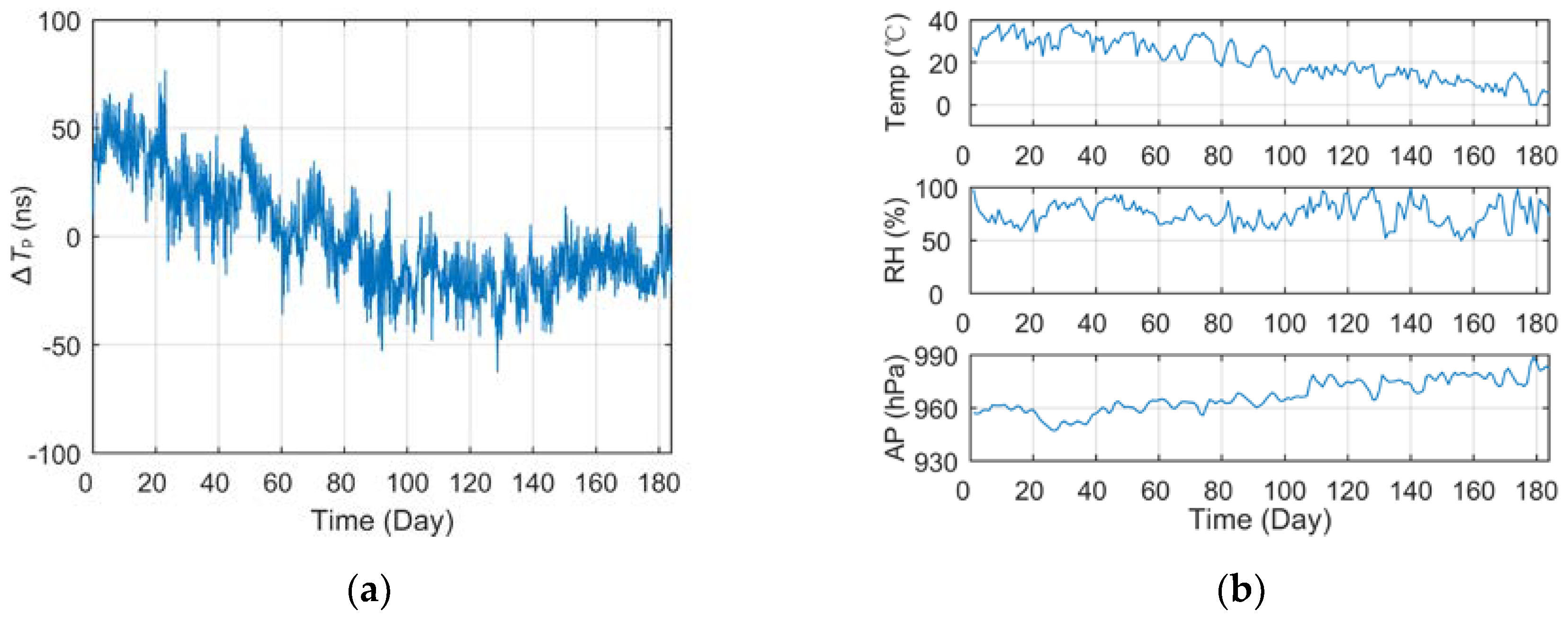

Figure 5a shows the curve of the long-term monitoring

Tp data in

Figure 3 after pre-processing such as smooth filtering, outlier removal, down-sampling and mean removal. Meanwhile,

Figure 5b shows the curve of meteorological data collected by the meteorological station (Weinan) on the corresponding signal propagation path in the same period.

It can be seen intuitively from

Figure 5 that the seasonal change of

Tp is strong linear correlation with the temperature and atmospheric pressure. The statistical data under different correlation analysis methods in

Table 3 also verify this conclusion. The PCC values of temperature and atmospheric pressure can reach to 0.8 and – 0.7 respectively. It can be seen that within a propagation distance of about 80 kilometers, the temperature difference of more than 40 °C leads to the peak-to-peak ∆

Tp exceeds 150 ns. This result also verifies the theoretical analysis in

Section 3.1 about the disturbance of meteorological factors in the calculation of

Tp and the conclusions of previous relevant studies.

3.2.2. Diurnal Correlation

According to the analysis results of seasonal correlation, it is not difficult to speculate that the short-term diurnal variation of

Tp should also be very strong because the temperature difference, rainfall, snowfall and other meteorological factors will also fluctuate dramatically within a day.

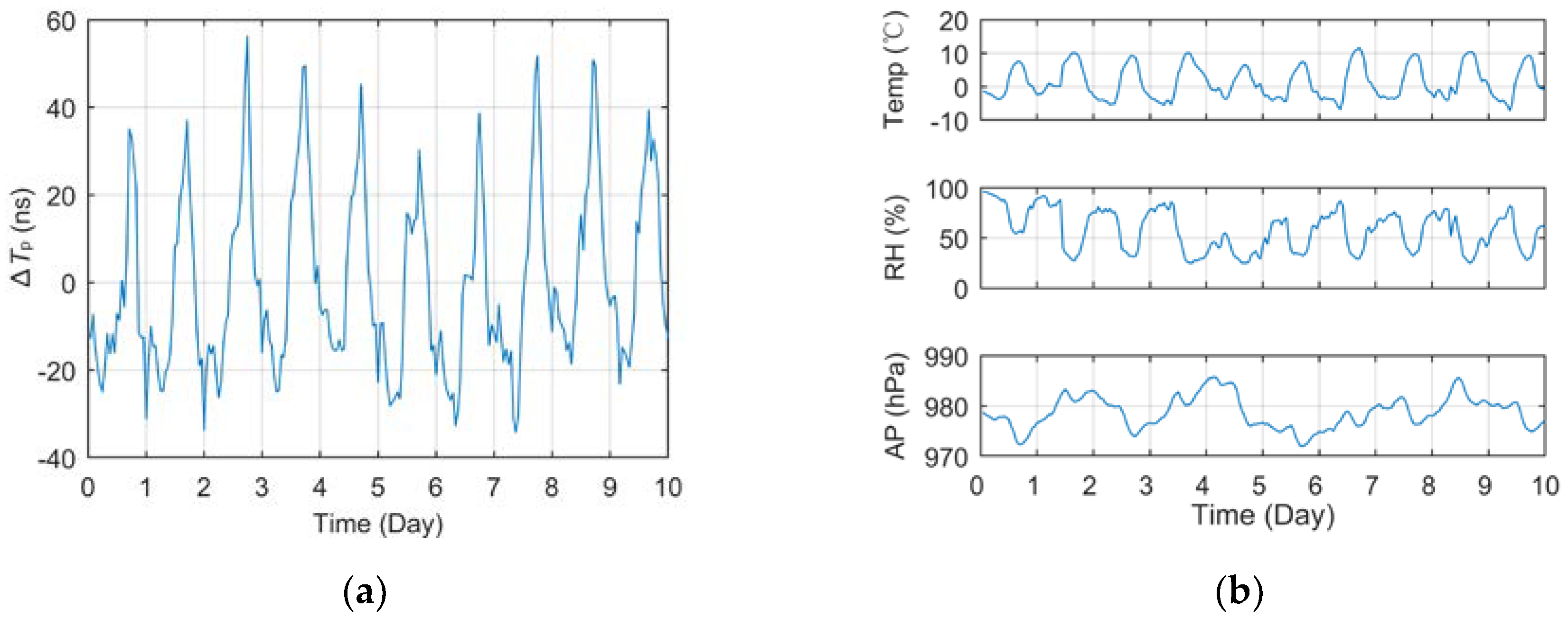

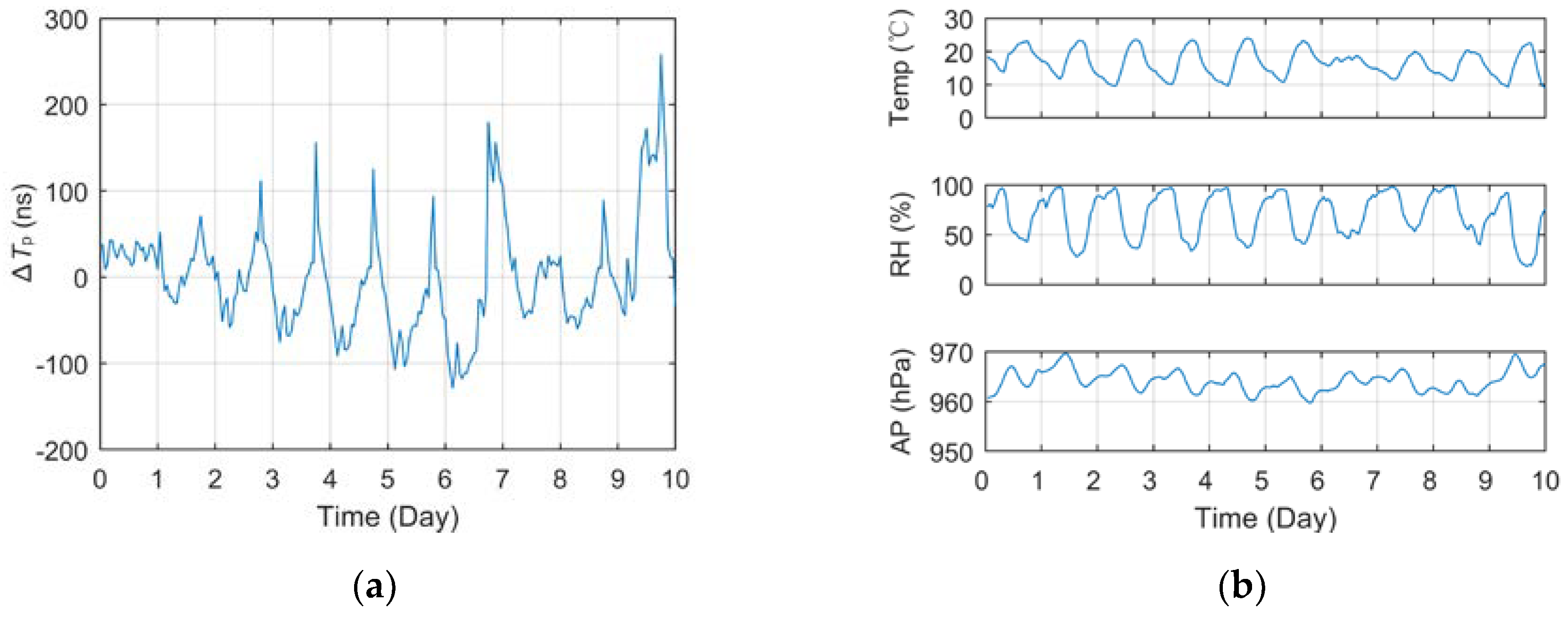

Figure 6 and

Figure 7 show the curves of short-term

Tp data collected at different test sites within 10 days and the meteorological data curves of corresponding meteorological station, including Jingyang (2021.1.9~2021.1.18, 70 km) and Meixian (2018.9.30~2018.10.9, 184 km). Among them, the

Tp data in the figure was pre-processed in the same way as in

Figure 5a.

The curve In the figures Indicated that the ∆Tp of different test locations vary dramatically within a day. In Meixian, where the propagation path is relatively long, the fluctuation of some days even exceeds 200 ns. In addition, the daily variation trend of Tp is similar to a certain extent, generally reaching the peak value around 14:00 to 15:00, and reaching the minimum value in the early morning, which has a strong consistency with the variation trend of temperature and relative humidity.

Table 4 shows the correlation coefficient between the daily measured

Tp and the three factors of temperature, relative humidity and atmospheric pressure respectively. Due to the large amount of data, only the PCC values are listed in the tables, while the other two types of unlisted correlation values have little difference. Among them, the linear correlation between temperature and

Tp is extremely high. Due to the close distance between Jingyang and the BPL station and the little change of the propagation path, the average PCC of temperature even exceeds 0.91, while the PCC of humidity reaches -0.89, and the correlation of atmospheric pressure also reaches a very high level.

At the same time, it can be seen that the PCC values of temperature and humidity decreased significantly at the far away test site in Meixian. On the one hand, on the 1st, 7th and 8th days, the receiver or the antenna failed respectively, resulting in the measurement error of Tp and the abnormal value of the correlation coefficient, which also affected the mean value. On the other hand, due to the longer propagation path, the meteorological changes in other parts of the path and other unconsidered meteorological factors may also affect the signal propagation characteristics, resulting in a lower correlation coefficient when the equipment is normal.

In order to identify more meteorological factors that may cause the ∆

Tp, while fully considering their regional changes, this paper applied different correlation analysis methods to jointly analyze the 60-day (January to March, 2022) continuous

Tp data collected at Jingyang test set and different meteorological factors from multiple meteorological observation stations on the same propagation path. Then, seven main meteorological factors including temperature, relative humidity, atmospheric pressure, water vapor pressure, wind speed, wind direction and precipitation with relatively strong correlation were identified. The correlation coefficient statistics are shown in

Table 5.

As can be seen from the data in

Table 5, there are obvious differences in the degree of correlation between different meteorological factors, and the same factor also has certain regional differences. For different correlation analysis types, the correlation characteristics of each meteorological factor are consistent, which also achieves the effect of mutual verification. In general, temperature and relative humidity have the greatest impact on

Tp, but other meteorological factors in the table also have non-negligible influence.

3.3. Correlation Discussion

The above theoretical analysis indicates that the real-time mutation of the three parameters of atmospheric refractive index , ground conductivity and relative dielectric constant will cause the calculation deviation of PF, SF and ASF, which is also the quantitative reflection of the influence of time-varying meteorological factors on Tp. The maximum fluctuation range of ∆Tp even reaches the microsecond level.

Firstly, the fluctuation of

PF is mainly affected by the time-varying characteristics of atmospheric refractive index

, and the maximum fluctuation range within the coverage of eLoran signal is generally in the order of 100 ns. At present, there have been some compensation models based on temperature, pressure factors [

49], which can partially correct some delay fluctuation errors. However, the applicable environment is mainly sea area, and the impact of

ASF fluctuation caused by changes in ground conductive environment is not fully considered.

Secondly, the fluctuation of SF and ASF is mainly affected by the time-varying characteristics of and , and the maximum variation range may reach the order of microsecond, which is the core component of ∆Tp. From the spatial dimension, the accuracy of calculation depends on the precision of terrain estimation and geodetic conductivity map. However, from the time dimension, due to the extremely complex correlation between meteorological disturbance and ground characteristics, there is no accurate compensation method for the fluctuation error.

What’s more, according to sufficient measurement data and different correlation coefficient analysis methods, it can be found that seven meteorological factors mentioned in section 3.2.2 are closely related to the real-time ∆Tp in different degrees. Among them:

Temperature and relative humidity have strong linear correlation with Tp, and are the leading factor affecting the ∆Tp.

The correlation of atmospheric pressure and vapor pressure is relatively stable, which will indirectly lead to ∆Tp fluctuation by affecting the characteristics of the propagation medium, but the linearity is limited.

Although the linear correlation is not obvious, the wind direction, wind speed and precipitation may have complex hidden correlation with the propagation medium. For example, wind speed and direction will affect the visibility, temperature and humidity of the atmosphere, and also seriously affect the roughness of the sea surface [

50,

51]. On the other hand, rain and snow can change the ground conductive properties in non-real-time [

52].

In addition to the unpredictable and serious impact of the propagation medium changes analyzed above on the propagation characteristics of electromagnetic waves, the regional differences of meteorological factors on the propagation path are also issues that must be considered in the study of propagation delay correction.

The nominal timing accuracy of eLoran system is 1 μs, and the future realization of differential technology requires that the timing accuracy be optimized to within 100 ns in the differential region. The compensation method of ∆Tp caused by meteorological disturbance is one of the urgent problem to be solved. According to the above analysis, a variety of meteorological factors have complex correlations with long-term seasonal and short-term daily changes of Tp that cannot be ignored, which may not be well described by simple models. Therefore, the nonlinear fitting ability of BP neural network algorithm is considered in this paper to explore the complex functional relationship between ∆Tp and multiple meteorological factors, and establish a prediction model of the overall fluctuation of Tp, so as to achieve accurate correction and prediction function of Tp.

4. Propagation Delay Prediction Model

4.1.LinearRegressionModel.

Previous studies mainly compensate ∆

Tp by establishing traditional linear model. Especially for the Loran-C system applied at sea, the linear correlation between temperature and

Tp is very strong, so the linear temperature model also has stable fitting and prediction capabilities. The mathematical form of the model is shown in Formula (15).

According to the residual between the fitting and the measured value

, the mean square error

of the sample is obtained, and then the partial derivatives of the two coefficients K and B of the linear model are calculated as

Based on the principle of least squares (LS), Formulas (16) and (17) are set to zero and solved simultaneously, and the following results can be obtained:

For terrestrial environment, the propagation characteristics of LF signal are more complex, and the effect of linear model may be somewhat reduced. However, considering the high linear correlation of temperature in the above analysis, a temperature-based linear prediction model of Tp is also established in our study, and its performance with other models is compared and analyzed in the following text.

4.2. BPNN Model

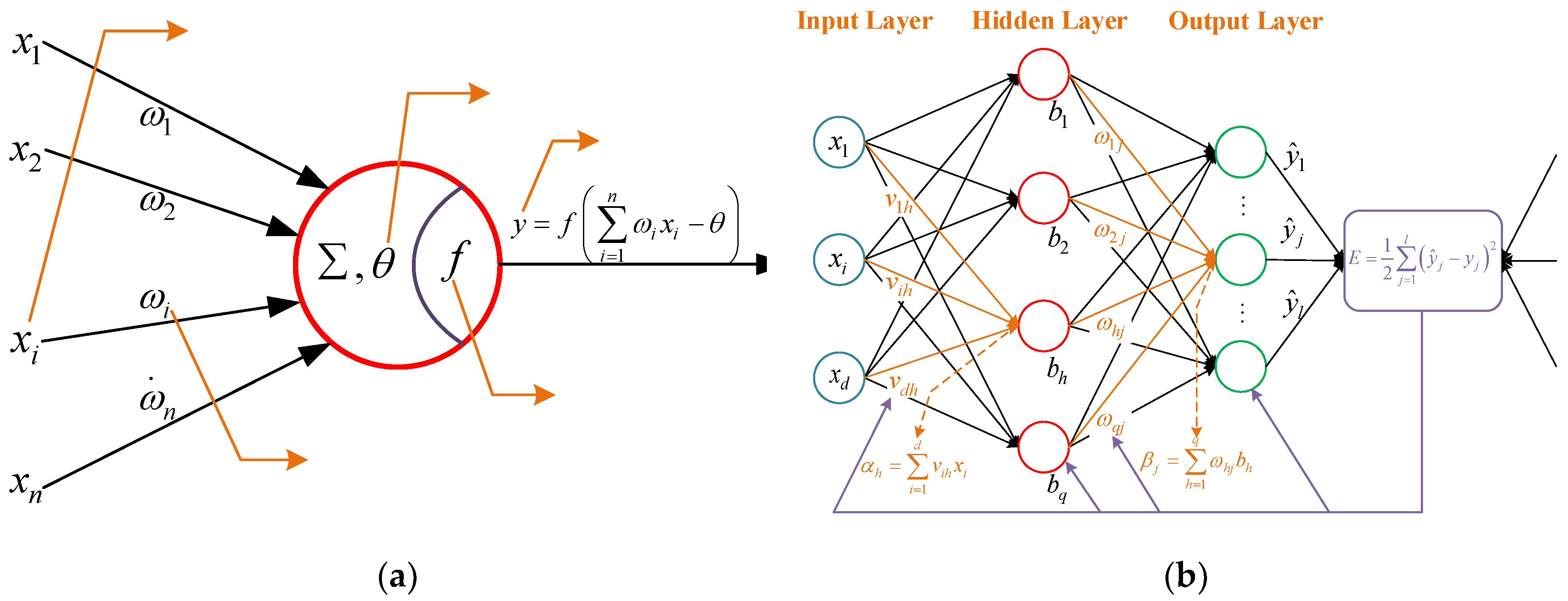

Neural network algorithm is a mathematical calculation model based on the structure and working principle of biological neural network. Its basic constituent structure is the neuron, as shown in

Figure 8a. Its mathematical composition is very simple, including weight vector

, threshold value (bias)

and activation function

. Activation function is to carry out nonlinear transformation of calculated results, so as to improve the mapping ability of neural network to deal with nonlinear fitting work. After each input vector

enters the neuron, it outputs the result in the form of

.

BPNN is the most successful and widely used feedforward neural network learning algorithm derived from the cross and fusion of multiple neurons. Its main feature is that the signal propagates forward, while the error propagates backward [

53]. The weight value of the network coefficient is corrected layer by layer through adaptive learning in the inverse propagation direction, so as to reduce the output error of the network as much as possible, finally achieve the purpose of training and realize the nonlinear fitting and prediction function. The principle of single hidden layer BPNN model can be described as the form in

Figure 8b, and the multi-hidden layer is similar [

54].

According to the analysis in

Section 3, multiple meteorological factors have direct or indirect effects on the real-time changes of

n,

,

and other factors that may affect the propagation characteristics of electromagnetic waves, and the correlation is extremely complex to be described by simple mathematical models. Relying on its powerful nonlinear mapping, fault tolerance and generalization capabilities, this paper considers skipping the indirect correlation, and uses BPNN to establish direct mapping between meteorological factors and

Tp, so as to improve the real-time prediction accuracy of ∆

Tp.

For the problems discussed in this paper, the number of hidden layers can be 1~3 according to different input conditions. As shown in

Figure 8b, the parameter derivation and modeling of BPNN with single hidden layer structure are carried out as follows:

Network Initialization. The cellular samples composed of various meteorological data and ∆

Tp should be divided into training set and test set in proportion (generally 7:3~9:1) and normalized to prevent overflow during training. Here, the training set

,

. According to the empirical Formula (20), the range of the number of hidden layer nodes can be estimated, and the best value q can be determined by trial-and-error method. In addition, set the learning rate and activation function, and initialize the connection weights and activation function thresholds between layers.

Input→Hidden→Output. In the network shown in

Figure 8b, three layers contain

d,

p and

l neurons respectively, and the forms of connection weights of forward transmission between layers are

and

respectively. The forms of activation function thresholds of the hidden and output layer are

and

respectively, then the corresponding activation function outputs can be expressed as:

Iterative Loss Function. For the

k-th training example

, after the activation function, the output layer gets

. Then the loss function

Ek can be obtained.

Reverse Gradient Calculation. BPNN algorithm is based on Stochastic Gradient Descent (SGD) strategy and updates parameters in the negative gradient direction of the target. For the iterative error

Ek, set the learning rate

,

, calculate the partial derivatives of the target parameters of each layer in reverse order, and then the corresponding gradient update value can be obtained as follows:

The above derivation process use the feature of sigmoid function: , and resolves the complex partial derivative operation of each parameter into a simple form, which greatly facilitates the calculation (similar to other activation function).

- 5.

Parameter Update and Iteration Judgment. Judge whether the training process meets the termination conditions. If not, adjust the parameters according to the calculation result of the updated values, and return to step 2 for the next training.

The above derivation process illustrates the basic framework and execution process of the BPNN model. Based on this, in view of the environment of multiple meteorological factors in multiple regions, different BP propagation delay prediction models are established in this study, and the optimal model is obtained by adjusting input meteorological factor type, hidden layer structure, learning rate, gradient overflow range and other parameters for model modification. The specific parameters and performance comparisons of all models are analyzed in detail in

Section 5.

5. Performance Analysis and Discussion

This section tests and compares different BPNN models and linear models under a variety of conditions, and the optimal model parameter selection will be uniformly displayed in

Section 5.4.

5.1. Data Acquisition and Processing

The data used to build the prediction model include the long-term continuous measurements of Tp collected from Jingyang test site and the statistical values of different meteorological factors at each meteorological station along the corresponding signal propagation path during the same period. Among them:

-

a.

-

Propagation delay data

Broadcasting station: BPL long-wave timing station in Pucheng;

Acquisition equipment: eLoran timing receiver (KTL-101B), long-wave receiving electric antenna (KTL-606A), GPS receiver, GPS receiving antenna, counter (SR620);

Collection site: Longquan Commune, Jingyang County, Xianyang City;

Collection period: 60 days (from Dec. 2021 to Mar. 2022, excluding some days of power failure and equipment failure);

Sampling rate: 1 times per second.

After the same preprocessing process as described in

Section 3.2.1, such as smooth filtering, outlier removal, down-sampling and mean value removal, the collected data can maintain the time corresponding relationship with the meteorological data and clearly show its fluctuations. The processed data is shown in

Figure 9.

-

b.

-

Meteorological data

Collection sites: 4 national meteorological observation stations in Pucheng, Fuping, Sanyuan and Jingyang;

Collection period: corresponding to propagation delay;

Data types: temperature, relative humidity, air pressure, water vapor pressure, wind speed, wind direction, amount of precipitation;

Data resolution: 1 times per hour.

The distribution of national meteorological stations (red marks) on the propagation path is shown in

Figure 10. Due to the long collection period, during which rain and snow or drastic temperature changes were experienced, the overall data of measured

Tp is representative to a certain extent.

5.2. Single-Factor Model

The correlation analysis results in

Section 3.2.2 show that temperature and relative humidity have strong linear correlation with

Tp, with PCC values up to 0.91 and -0.89 respectively. Therefore, this section considering using temperature and relative humidity as network inputs to adjust neural network parameters and train to obtain a single factor BPNN prediction model, and establishing the linear model for analysis and comparison.

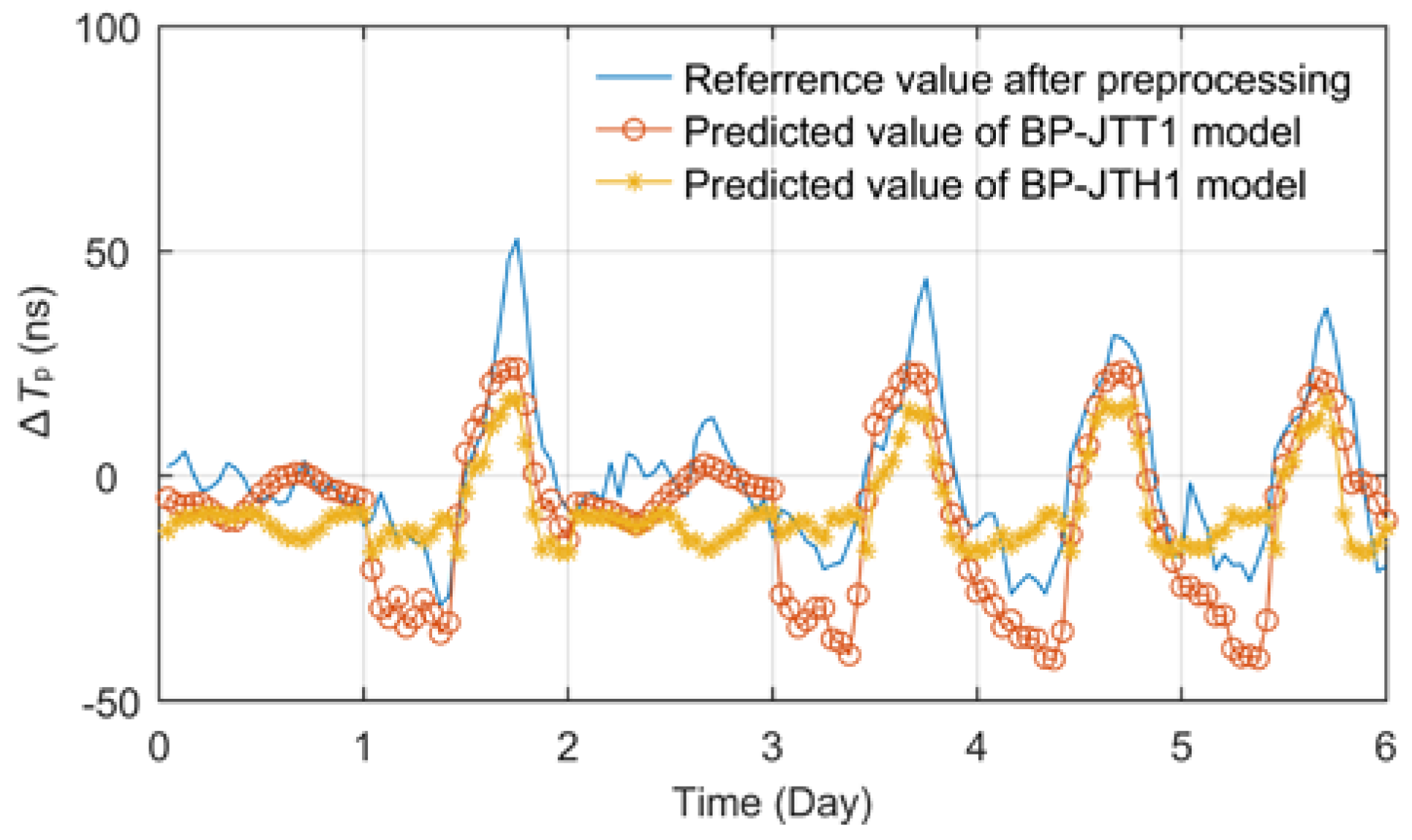

Firstly, 54 days (90%) of observation data were randomly selected to build the training set, and the other 6 days (10%) of data were used as the test set. Secondly, the temperature and relative humidity data of Jingyang meteorological station were used as the single-factor input respectively, the number of hidden layers was selected as 1~2, and the number of hidden layer nodes was selected as 3~12 to build different BPNN models. Then, according to the principles of minimum root mean square error (RMSE), the optimal models were obtained, which are called Jingyang time-delay temperature (single point) BP neural network (BP-JTT1) and Jingyang time-delay relative humidity (single point) BP neural network (BP-JTH1) respectively. The test results are shown in

Figure 11.

According to the effect comparison displayed in

Figure 11, the model BP-JTT1 established based on temperature factor has a higher fitting degree than BP-JTH1 based on relative humidity. The RMSE and mean absolute error (MAE) of BP-JTT1 are 9.4467 ns and 10.2120 ns, while those of BP-JTH1 model are 12.7932 ns and 13.1453 ns.

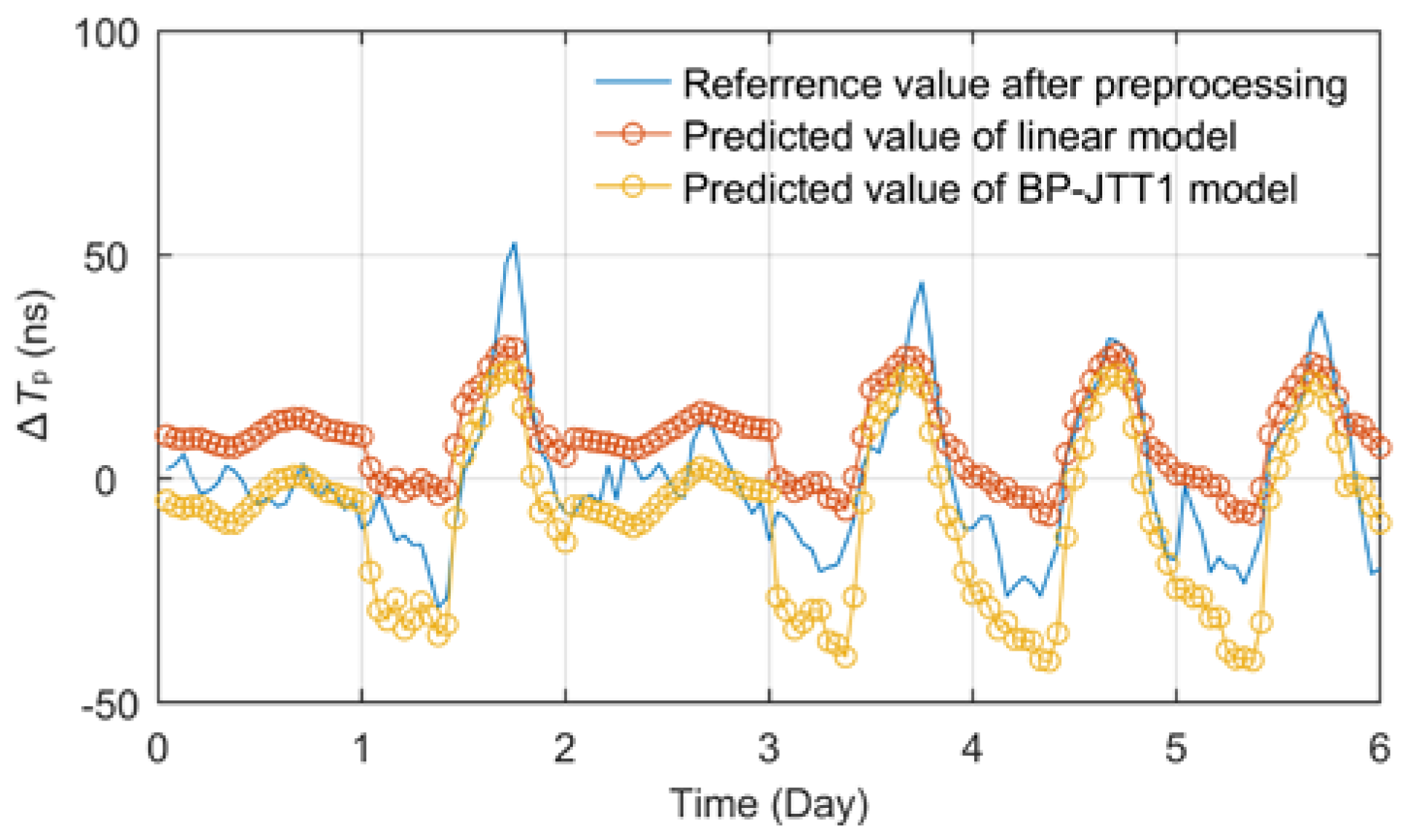

Both the two models have stable fitting and prediction capabilities for propagation delay fluctuations, but because of the stronger linear correlation of temperature factors, the prediction effect is also significantly better. Therefore, a linear prediction model based on temperature was established for comparative analysis. By substituting the same training set data above into Formulas (18) and (19), the linear model coefficients

K = 2.4065 and

B = 3.3738 can be obtained. Use the test set data to verify the model, and the effect comparison is shown in

Figure 12.

Data statistics show that the RMSE and MAE of the linear model are 9.2591 ns and 11.2292 ns, the maximum absolute error (MAXE) is 35.9205 ns. Several indexes are all slightly inferior to BP-JTT1 model, which also verifies the results and conclusions of previous studies on single-factor BP model and linear model [

20,

21,

27]. Especially when the weather changes abruptly and the temperature is relatively stable, the meteorological disturbance factors may affect the linearity of the temperature model, so the uncertainty of the model will increase and the fitting effect will further decline. This is also the inevitable result of simple model and too few interference factors taken into account.

5.3. Multi-Factor Model

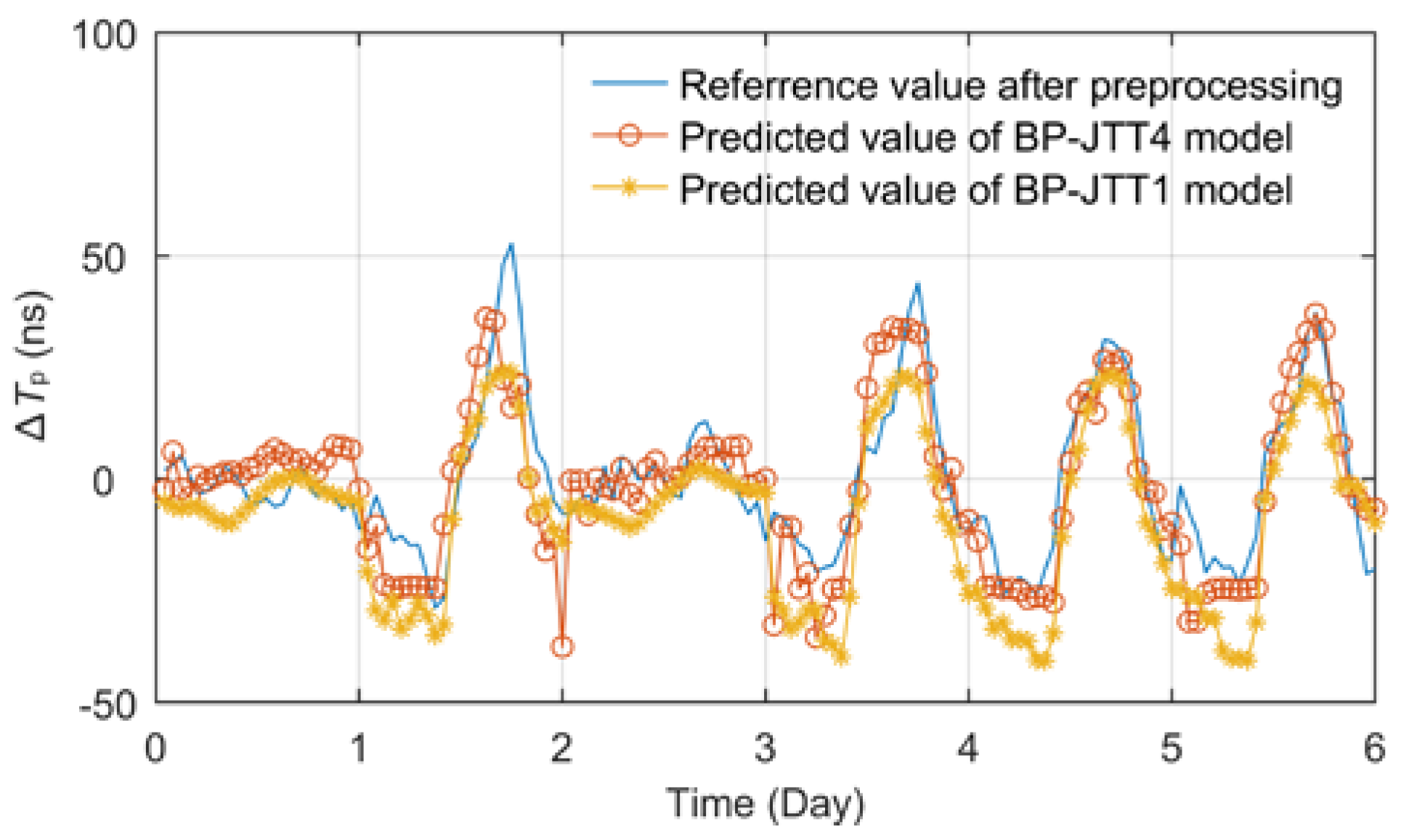

The single-factor BPNN model BP-JTT1, BP-JTH1 and linear model introduced in the previous section have stable fitting and prediction effect, but the accuracy is general. Therefore, this section took into account the influence of regional changes and diversity of meteorological factors to propose the multi-dimensional models.

Firstly, the influence of multiple meteorological regions was considered. According to the temperature statistics of 4 meteorological stations along the propagation path from Pucheng to Jingyang, a variety of BP neural network models with 1~2 hidden layers and 4~13 hidden layer nodes were established, and the optimal model BP-JTT4 was obtained. According to statistics, the number of hidden layers and nodes of this kind of BP models, which only considers temperature factors, has little influence on the fitting effect. However, there may be training overflow errors in a single hidden layer structure. Therefore, it is recommended to design the hidden layer as a two-layer structure.

The prediction effect of the optimal BP-JTT4 model is shown in

Figure 13. According to statistics, the RMSE, MAE and MAXE indexes of the BP-JTT4 model are 8.5696 ns, 6.4151 ns and 23.8801 ns, respectively. It can be seen that when considering the joint influence of multiple related meteorological regions at the same time, the effect of the BP temperature prediction model is improved to a certain extent compared with the BP-JTT1 model, which can cope with the temperature changes in different regions on a longer propagation path.

Although the BP-JTT4 model has been able to achieve good fitting and prediction results, the impact of more related meteorological factors, especially the recessive or weak correlation factors, cannot be quantified.

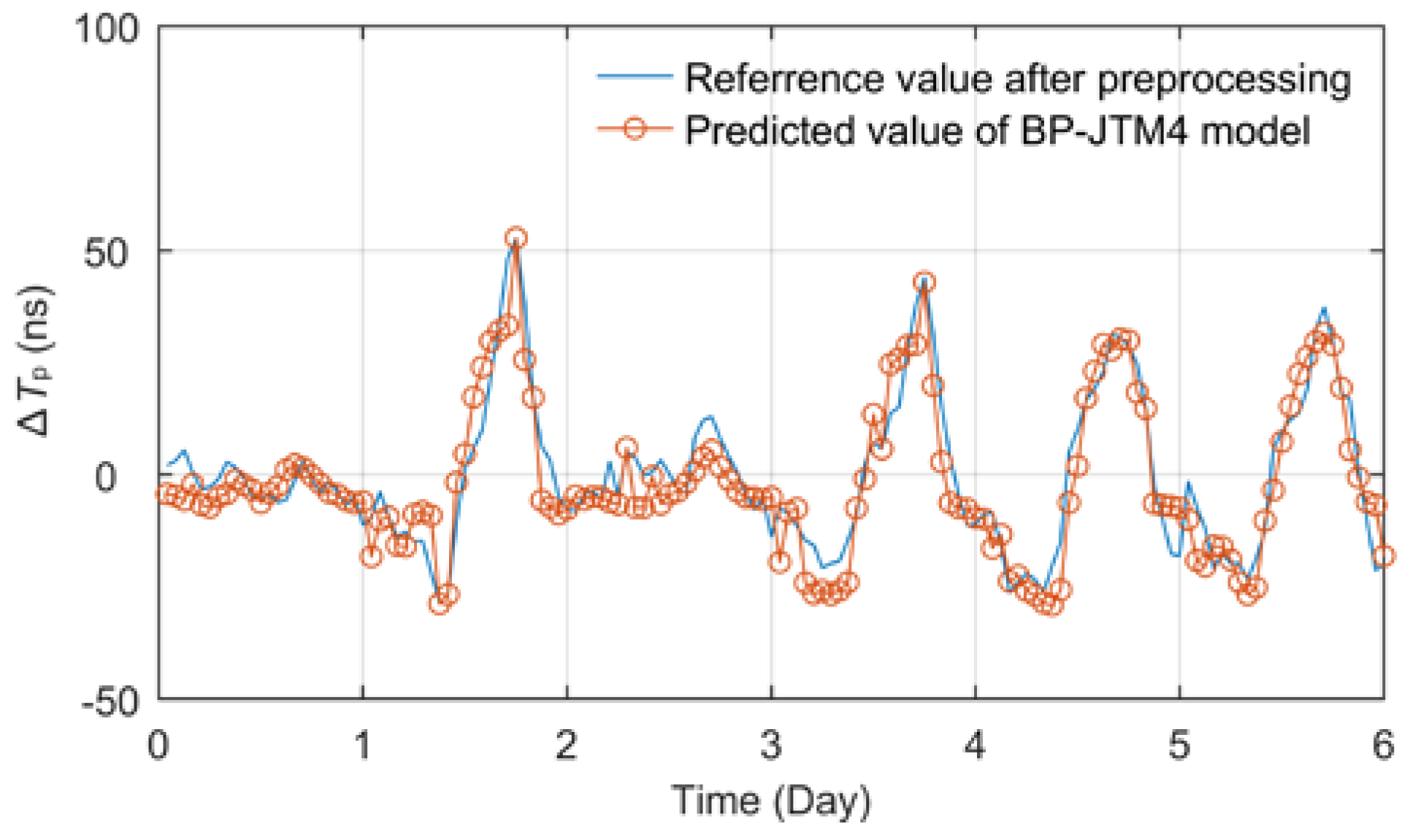

In view of the diversity of relevant meteorological factors, we also proposed the multi-layer BPNN models with input layer dimension of 28 on the basis of BP-JTT4 to fit the fluctuation of propagation delay. The data of the network input layer includes seven related meteorological factors such as temperature, relative humidity, atmospheric pressure, water vapor pressure, wind speed, wind direction and rainfall collected from 4 meteorological observation points along the signal transmission path. The number of hidden layers selected 1~3, and the number of nodes selected 7~16, 4~13 and 4~13 respectively. Then, according to the minimum RMSE principle, the optimal prediction model, called BP-JTM4, was obtained and its effect is shown in

Figure 14.

Obviously, when considering a variety of meteorological disturbance factors and their regional changes, the prediction effect of ∆Tp is excellent. The coincidence degree between the predicted curve and the measured curve is quite high, and the performance index also reaches the best. RMSE and MAE indexes reach 6.2457 ns and 5.0817 ns respectively, and MAXE value is only 14.8372 ns.

5.4. Comprehensive Performance Analysis

For accurate predict ∆

Tp, the above contents in this section studied and established the BPNN prediction models with various input conditions and types of meteorological factors and the temperature linear prediction model. Meanwhile, make statistical analysis and comparison of the predicted values of each model with the same test set. The performance indexes of each model and the optimal structure composition of the four types of BPNN models are respectively shown in

Table 6 and

Table 7.

Through the above modeling analysis and performance statistics, the following conclusions can be drawn:

The three models with single input factor all have certain fitting ability, among which the temperature model performs better than the relative humidity model and the linear model, which verifies the conclusions of previous studies. The setting of single hidden layer is sufficient to achieve the optimal state of single-factor BPNN model.

BPNN can effectively deal with the problem of ∆Tp prediction of eLoran groundwave, and with the increase of the input layer correlation factor dimension, the adaptive training ability of multi-layer network is fully reflected. Compared with BP-JTT1 model, the fitting stability and accuracy of BP-JTM4 model are significantly improved, and its RMSE and MAE decreased by 33.88% and 50.24%, respectively.

The BP-JTM4 prediction model proposed in this paper considering multi-regional and multi-meteorological factors has excellent performance. When the model parameters are optimal, RMSE and MAE can even reach 6.2457 ns and 5.0817 ns, and the MAXE is less than 15 ns, which fully reflects its superior propagation delay fitting ability. The modeling method can accurately predict the ∆Tp of ASF grid vertices in the future, so as to well meet the Tp correction requirement of eLoran system.

Figure 1.

Signal waveforms of (a) standard Loran-C pulse; (b) Loran-C main station pulse group.

Figure 1.

Signal waveforms of (a) standard Loran-C pulse; (b) Loran-C main station pulse group.

Figure 2.

Principle of autonomous timing of eLoran system.

Figure 2.

Principle of autonomous timing of eLoran system.

Figure 3.

Long-term measurement value of propagation delay at Lintong monitoring station.

Figure 3.

Long-term measurement value of propagation delay at Lintong monitoring station.

Figure 4.

Changes of SF + ASF under different ground types.

Figure 4.

Changes of SF + ASF under different ground types.

Figure 5.

Long-term data curve and meteorological factors change of corresponding test site (Lintong): (a) Relative propagation delay; (b) Major meteorological factors.

Figure 5.

Long-term data curve and meteorological factors change of corresponding test site (Lintong): (a) Relative propagation delay; (b) Major meteorological factors.

Figure 6.

Short-term data curve and meteorological factors change of corresponding test site (Jingyang): (a) Relative propagation delay; (b) Major meteorological factors.

Figure 6.

Short-term data curve and meteorological factors change of corresponding test site (Jingyang): (a) Relative propagation delay; (b) Major meteorological factors.

Figure 7.

Short-term data curve and meteorological factors change of corresponding test site (Meixian): (a) Relative propagation delay; (b) Major meteorological factors.

Figure 7.

Short-term data curve and meteorological factors change of corresponding test site (Meixian): (a) Relative propagation delay; (b) Major meteorological factors.

Figure 8.

Schemes diagrams of: (a) Artificial neuron model; (b) Single hidden layer BPNN model.

Figure 8.

Schemes diagrams of: (a) Artificial neuron model; (b) Single hidden layer BPNN model.

Figure 9.

Variation curve of ∆Tp at Jingyang test site for 60 consecutive days.

Figure 9.

Variation curve of ∆Tp at Jingyang test site for 60 consecutive days.

Figure 10.

Signal propagation path and distribution of meteorological stations.

Figure 10.

Signal propagation path and distribution of meteorological stations.

Figure 11.

Comparison of single-factor BPNN prediction models.

Figure 11.

Comparison of single-factor BPNN prediction models.

Figure 12.

Effect diagram of temperature linear prediction model.

Figure 12.

Effect diagram of temperature linear prediction model.

Figure 13.

Effect diagram of BP-JTT4 prediction model.

Figure 13.

Effect diagram of BP-JTT4 prediction model.

Figure 14.

Effect diagram of BP-JTM4 prediction model.

Figure 14.

Effect diagram of BP-JTM4 prediction model.

Table 1.

Seasonal variation of refractive index value (unit: N) in different regions of China.

Table 1.

Seasonal variation of refractive index value (unit: N) in different regions of China.

| Region |

January |

April |

July |

October |

Annual

Average |

Annual

Range |

| Guangzhou |

323 |

362 |

380 |

353 |

353 |

57 |

| Shanghai |

316 |

333 |

383 |

342 |

343 |

67 |

| Wuhan |

314 |

334 |

383 |

337 |

342 |

69 |

| Beijing |

301 |

301 |

361 |

311 |

320 |

60 |

| Chengdu |

303 |

320 |

351 |

320 |

320 |

48 |

| Urumqi |

292 |

281 |

290 |

285 |

285 |

11 |

| Kunming |

259 |

270 |

299 |

280 |

279 |

40 |

| Lanzhou |

253 |

246 |

272 |

265 |

278 |

26 |

| Hohhot |

277 |

260 |

292 |

272 |

272 |

32 |

| Lhasa |

192 |

194 |

220 |

202 |

202 |

28 |

Table 2.

Conductivity parameter values of 9 typical ground types.

Table 2.

Conductivity parameter values of 9 typical ground types.

Reference

Ground Type |

|

(S/m) |

(S/m) |

Equivalent Earth

Radius Coefficient |

| Average seawater |

70 |

5 |

7~3 |

1.14 |

| Conductive ground |

40 |

3×10-2

|

5.5×10-2~1.7×10-2

|

1.13 |

| Wet ground |

30 |

1×10-2

|

1.7×10-2~5.5×10-3

|

1.11 |

| Average ground |

22 |

3×10-3

|

5.5×10-3~1.7×10-3

|

1.08 |

| Sub dry ground |

15 |

1×10-3

|

1.7×10-3~5.5×10-4

|

1.06 |

| Dry ground |

7 |

3×10-4

|

5.5×10-4~1.7×10-4

|

1.05 |

| Very dry ground |

3 |

1×10-4

|

1.7×10-4~5.5×10-5

|

1.06 |

| -1 ℃ Fresh water ice |

3 |

3×10-5

|

5.5×10-5~1.7×10-5

|

1.06 |

| -10 ℃ Fresh water ice |

3 |

1×10-5

|

1.7×10-5~5.5×10-6

|

1.07 |

Table 3.

Correlation coefficients between long-term Tp and meteorological factors.

Table 3.

Correlation coefficients between long-term Tp and meteorological factors.

| CT |

TEMP |

RH |

AP |

| Pearson |

0.8119 |

-0.0051 |

-0.7087 |

| Spearman |

0.7939 |

-0.0119 |

-0.7218 |

| Kendall |

0.5892 |

-0.0023 |

-0.4881 |

Table 4.

PCC between measured diurnal Tp and meteorological factors (Jingyang and Meixian).

Table 4.

PCC between measured diurnal Tp and meteorological factors (Jingyang and Meixian).

| Test Time |

Jingyang |

|

Meixian |

| TEMP |

RH |

AP |

|

TEMP |

RH |

AP |

| Day 1 |

0.9206 |

-0.7002 |

0.3093 |

|

0.0042 |

0.0188 |

-0.1449 |

| Day 2 |

0.8996 |

-0.8645 |

-0.8277 |

|

0.7394 |

-0.6554 |

-0.7025 |

| Day 3 |

0.9354 |

-0.9065 |

0.3300 |

|

0.7136 |

-0.6240 |

-0.7472 |

| Day 4 |

0.9501 |

-0.9330 |

-0.4682 |

|

0.7292 |

-0.6936 |

-0.7937 |

| Day 5 |

0.9539 |

-0.9512 |

-0.6129 |

|

0.8416 |

-0.7745 |

-0.7364 |

| Day 6 |

0.8771 |

-0.8401 |

0.0435 |

|

0.7487 |

-0.6551 |

-0.7997 |

| Day 7 |

0.9072 |

-0.9134 |

-0.8320 |

|

-0.5730 |

0.4745 |

0.1897 |

| Day 8 |

0.9082 |

-0.9187 |

-0.0688 |

|

0.0790 |

0.1443 |

-0.5147 |

| Day 9 |

0.9523 |

-0.9409 |

-0.5955 |

|

0.7092 |

-0.7936 |

-0.3584 |

| Day 10 |

0.8864 |

-0.9143 |

-0.5088 |

|

0.8374 |

-0.8578 |

0.3577 |

| Mean Value |

0.9191 |

-0.8883 |

-0.3231 |

|

0.4829 |

-0.4416 |

-0.4250 |

Table 5.

Correlation coefficient between Tp and various meteorological factors of each meteorological stations along the propagation path.

Table 5.

Correlation coefficient between Tp and various meteorological factors of each meteorological stations along the propagation path.

| MS (Number) |

CT |

TEMP |

RH |

AP |

VP |

AoP |

WS |

WD |

Pucheng

(53948) |

|

0.6225 |

-0.6005 |

-0.1822 |

-0.2109 |

0.0929 |

0.2025 |

-0.1002 |

|

0.5872 |

-0.5912 |

-0.1573 |

-0.1762 |

0.1578 |

0.2118 |

-0.1061 |

|

0.4691 |

-0.4621 |

-0.1298 |

-0.1446 |

0.1205 |

0.1444 |

-0.0739 |

Fuping

(57042) |

|

0.6145 |

-0.5970 |

-0.1802 |

-0.2342 |

0.1177 |

0.1232 |

-0.2123 |

|

0.5845 |

-0.5738 |

-0.1597 |

-0.1783 |

0.1161 |

0.1134 |

-0.1801 |

|

0.4638 |

-0.4428 |

-0.1311 |

-0.1447 |

0.0858 |

0.0734 |

-0.1194 |

Sanyuan

(57041) |

|

0.6256 |

-0.6222 |

-0.1880 |

-0.2219 |

0.1428 |

0.1372 |

-0.2939 |

|

0.5931 |

-0.5918 |

-0.1627 |

-0.1840 |

0.1143 |

0.0980 |

-0.2671 |

|

0.4724 |

-0.4621 |

-0.1325 |

-0.1483 |

0.0819 |

0.0647 |

-0.1804 |

Jingyang

(57033) |

|

0.6201 |

-0.5681 |

-0.1863 |

-0.2125 |

0.0696 |

0.2747 |

-0.1249 |

|

0.6001 |

-0.5505 |

-0.1582 |

-0.1760 |

0.0516 |

0.2577 |

-0.1261 |

|

0.4786 |

-0.4318 |

-0.1293 |

-0.1463 |

0.0395 |

0.1797 |

-0.0877 |

Table 6.

Performance indexes of propagation delay prediction models.

Table 6.

Performance indexes of propagation delay prediction models.

| Meteorological Data Type |

Data Scope |

Model |

RMSE (ns) |

MAE (ns) |

MAXE (ns) |

| RH |

Single region |

BP-JTH1 |

12.7932 |

13.1453 |

30.1544 |

| TEMP |

Single region |

BP-JTT1 |

9.4467 |

10.2120 |

28.8836 |

| TEMP |

Single region |

Linear |

9.2591 |

11.2292 |

35.9205 |

| TEMP |

Full path |

BP-JTT4 |

8.5696 |

6.4151 |

23.8801 |

| TEMP, RH, AP, VP, AoP, WS and WD |

Full path |

BP-JTM4 |

6.2457 |

5.0817 |

14.8372 |

Table 7.

Parameters of different BP neural network models.

Table 7.

Parameters of different BP neural network models.

| Model |

Number of |

Activation Function |

Learning

Rate |

Iteration

Times |

| Input Layer Nodes |

Hidden Layer |

Hidden Layer Nodes |

| BP-JTH1 |

1 |

1 |

4 |

Sigmoid

Sigmoid

Sigmoid, Tanh

Sigmoid, Tanh |

0.1 |

5000 |

| BP-JTT1 |

1 |

1 |

4 |

| BP-JTT4 |

4 |

2 |

10, 4 |

| BP-JTM4 |

28 |

2 |

10, 4 |