1. INTRODUCTION

During meiosis, a single round of DNA replication is followed by two successive divisions (meiosis I and meiosis II), producing haploid gametes. This is achieved by segregation of homologous chromosomes during meiosis I, followed by segregation of sister chromatids in meiosis II. During meiosis, homolog pairing and recombination culminate at the pachytene stage, when homologs are paired along their entire lengths and are connected by the synaptonemal complex (SC). Upon pachytene exit, the SC disassembles and the homologs are connected by crossovers (1-3). SC disassembly in mice is known to require a complex comprising the master cell cycle regulator protein CDK1 and Cyclin B1 and Polo-like kinase PLK1.

Further, multiple protein mutants have been shown to disrupt the activation of CDK1, leading to SC disassembly defects and ultimately result in the arrest of spermatogenesis at the prophase I stage of meiosis (4-6). Although some of the biochemical details remain unknown, CDK1 activation in meiotic prophase I is known to require interaction with the chaperone protein HSPA2 prior to its interaction with Cyclin B1. Several studies have reported that HSPA2 localizes to the SC, and one study proposed that CDK1 recruitment to the SC is mediated via its interaction with HSPA2 in the pachytene stage (7-9). If correct, this hypothesis would indicate that CDK1 activation occurs at the SC, and suggests that the CDK1–Cyclin B1 complex may somehow assist SC disassembly, possibly via CDK1-mediated phosphorylation of SC components and/or unknown proteins.

SC disassembly in mice is also known to require Polo-like kinase 1 (PLK1). Mouse PLK1 localizes to the central region of the SC during the pachytene stage and is involved in disassembly of the SC central element by directly phosphorylating SYCP1 and TEX12, two central region components that function in central element disassembly during the diplotene stage (10,11). During the mitotic cell cycle, PLK1 is activated via phosphorylation by Aurora A (in a CDK1/Cyclin A-dependent manner), and activated PLK1 then phosphorylates CDC25, triggering activation of the CDK1–Cyclin B1 complex. However, it is not known if or how CDK1 and PLK1 functionally interact during the meiotic cell cycle (12-14).

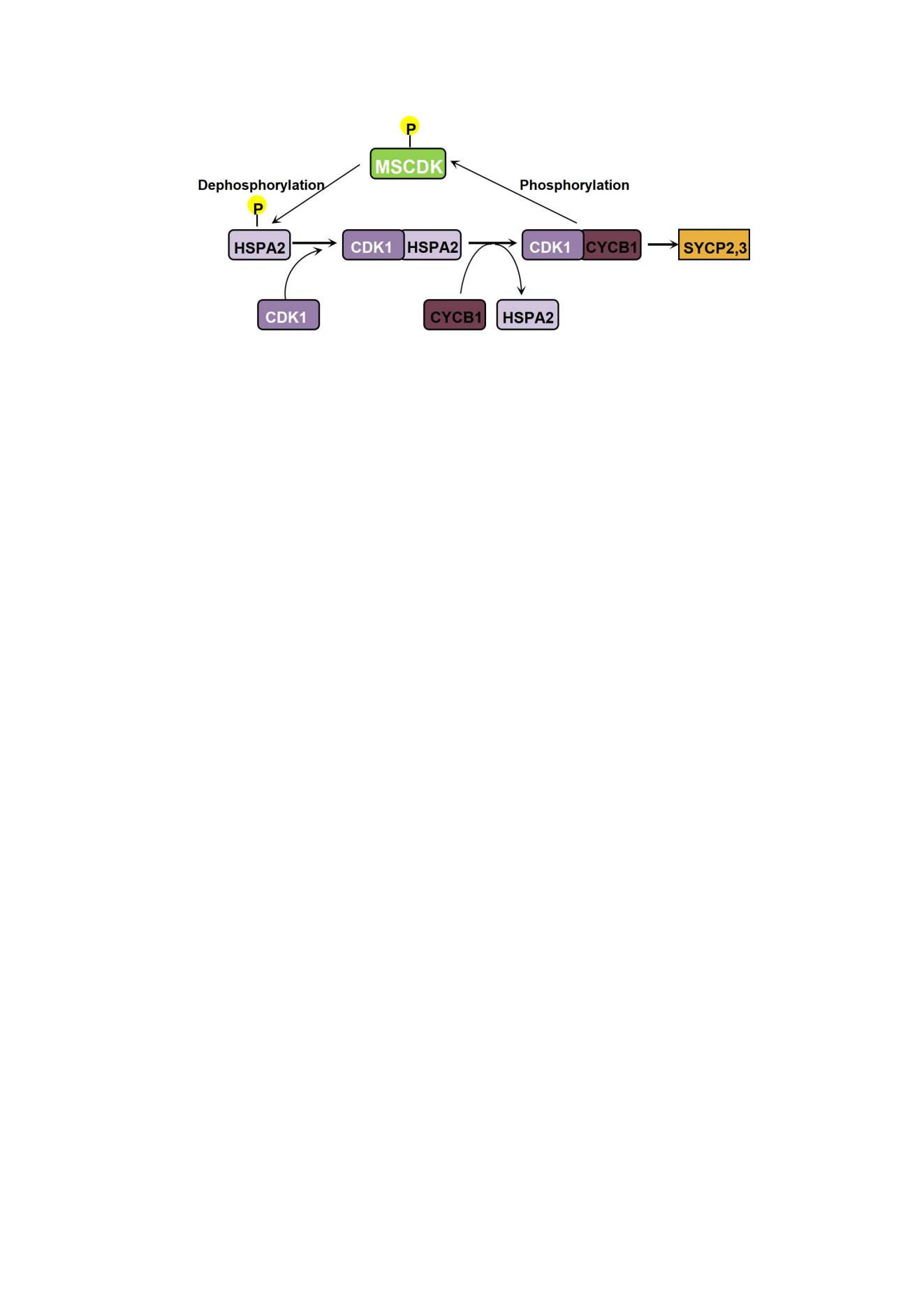

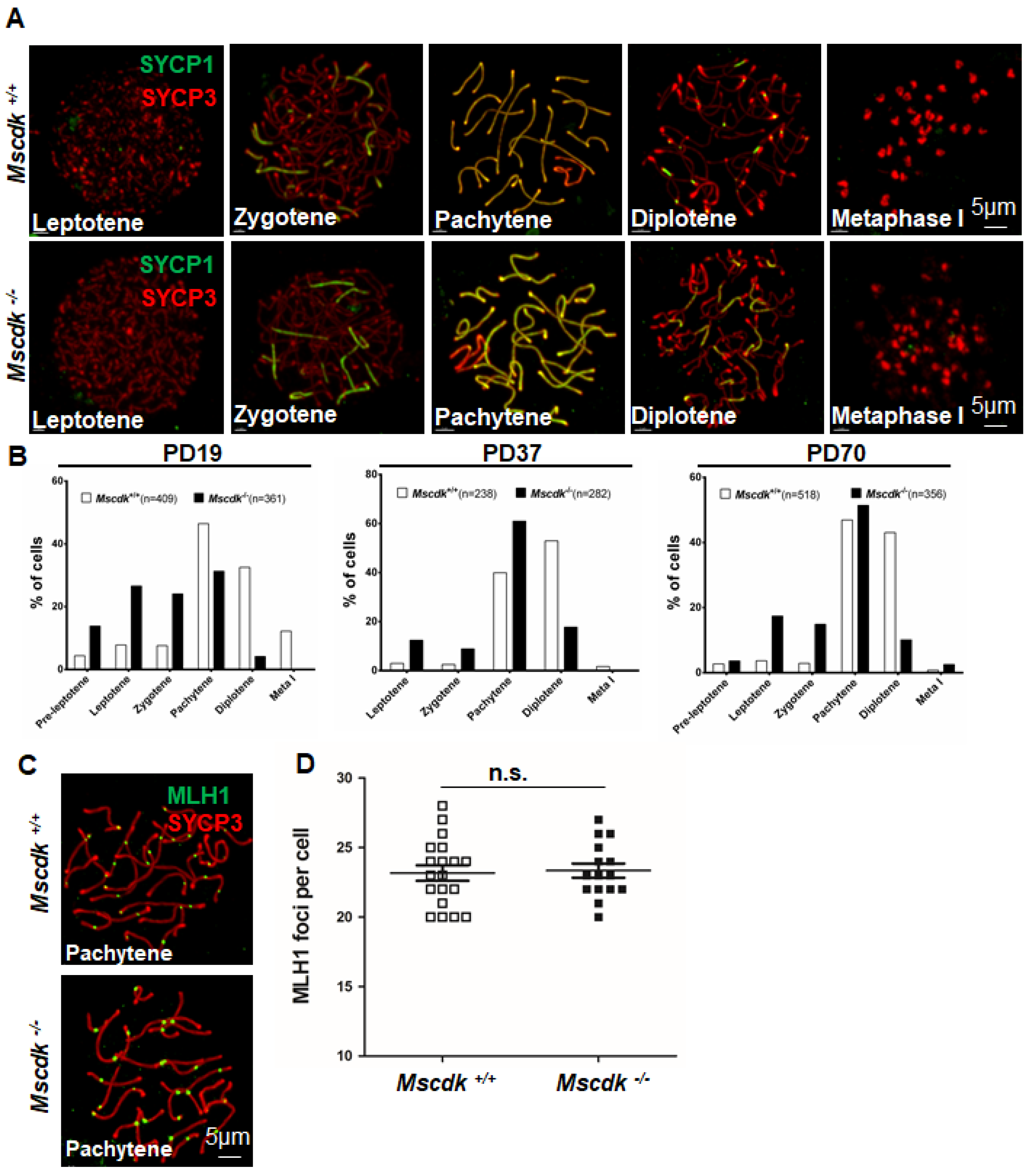

Here, we have identified a novel protein MSCDK in the germ cells of male mice that controls SC disassembly and regulates the metaphase I transition during meiosis prophase I. We used an antibody against MSCDK (developed in the present study) for immunofluorescence analyses which revealed that MSCDK appears with a sparsely distributed pattern of discrete foci along the synapsed axes of homologous chromosomes from the early zygotene to the early diplotene stages of meiosis prophase I. We generated Mscdk knockout mice and observed that their crossover formation is not obviously affected, although they exhibit clear SC disassembly defects that result in infertility in male but not female mice. In vitro phosphorylation assays demonstrate that MSCDK is a phosphorylation substrate of CDK1 and a dephosphorylation substrate of the cell cycle exit regulator PP1α. Intriguingly, we also found that MSCDK expedites SC disassembly by participating in the dephosphorylation of HSPA2, thereby promoting its protein stability and nuclear recruitment. We propose a model wherein SC-localized HSPA2 can activate CDK1 in early pachytene stage nuclei, after which CDK1 mediates the phosphorylation-based activation of MSCDK. Activated MSCDK then functions to dephosphorylate HSPA2, further promoting HSPA2 recruitment to expedite SC disassembly.

2. METHODS AND MATERIALS

2.1. Mice

The mice used in this study were housed in the animal management center under SPF conditions of Shandong University. Mice were raised in the animal management center of Shandong University in accordance with the guidelines of the animal ethics committee and the Animal Care and Use Committee of Shandong University..All animal experiments were performed according to approved institutional animal care and use committee (IACUC) protocols (#2018-36) of Shandong University.

2.2. Production of CRISPR/Cas9-edited Mscdk gene knockout mice

The mouse Mscdk gene (Transcript: ENSMUSG00000032611) is located on chromosome 9. Four exons have been identified, with an ATG start codon in exon 2 and a TGA stop codon in exon 4. The Mscdk-deficient mice in a C57BL/6 genetic background were generated by deleting the genomic DNA fragment covering exon 3 using a CRISPR/Cas9-mediated genome editing system from Cyagen Biosciences. The founders were genotyped by PCR followed by DNA sequencing analysis. Intercrossing of Mscdk heterozygous mice yielded healthy offspring at Mendelian ratios. The mice were housed under controlled environmental conditions with free access to water and food, and illumination was on between 6 am and 6 pm. All experimental protocols were approved by the Animal Ethics Committee of the School of Medicine, Shandong University.

2.3. Genotyping

Genotyping was performed using genomic DNA extracted from mouse tails by PCR amplification. PCR primers for the Mscdk mutant allele were Forward: 5'-ACCGTCCTTTCCCACACCTAAGTCT-3' and Reverse: 5'- AGTGTCCACACACACGGTTCAATTC-3', yielding a 613 bp fragment. PCR primers for the Mscdk wild-type allele were Forward: 5'- ACCGTCCTTTCCCACACCTAAGTCT-3' and Reverse: 5'- TTGAGGGGAGAAGATGGGGAATTA-3', yielding a 732 bp fragment.

2.4. Real-time PCR

Total RNA was isolated from various tissues of wild-type mice and testis tissues of various aged wild-type mice. To analyze the expression of Mscdk mRNAs in various tissues and various aged mice, equal amounts of cDNA were synthesized using the PrimeScript RT reagent Kit with gDNA Eraser (Takara). qPCR was performed using TB Green Premix Ex Taq (Takara) and specific forward and reverse primers: Mscdk primer pair F 5'-GTGATGGGGAAGACTGGAGA-3' and R 5'-AAGGGTGAATCTTGGCAGTG-3'. β-actin was amplified as a housekeeping gene with the primers β-actin F 5'-CAT CCG TAA AGA CCT CTA TGC CAA C-3' and β-actin R 5'-ATG GAG CCA CCG ATC CAC A-3'. All RT-PCR reactions were performed with an initial denaturation at 95°C for 10 min followed by 25 cycles of denaturation at 95°C for 30 s, annealing at 60°C for 30 s, and extension at 72°C for 30 s, and a final extension at 72°C for 5 min using a T100 Thermal Cycler (Bio-Rad).

2.5. Tissue collection and histological analysis

Testes and ovaries from more than three mice for each genotype were dissected immediately after euthanasia, fixed in 4% (mass/vol) paraformaldehyde (Solarbio, #P1110) for up to 24 h, stored in 70% ethanol, and embedded in paraffin after dehydration. The 5 μm sections were prepared and mounted on glass slides. After deparaffinization, slides were stained with hematoxylin for histological analysis.

2.6. Immunocytology and antibodies

Spermatocyte spreads were prepared as previously described (15). Primary antibodies used for immunofluorescence were as follows: rabbit anti-SYCP3 (1:500 dilution; Abcam #ab15093), mouse anti-SYCP3 (1:500 dilution; Abcam #ab97672), rabbit anti-SYCP1 (1:2,000 dilution; Abcam #ab15090), rabbit anti-SYCP1 (1:2,000 dilution; Abclonal #A12139), rabbit anti-RPA2 (1:200 dilution; Abcam #ab76420), rabbit anti-RAD51 (1:200 dilution; Thermo Fisher Scientific #PA5-27195), mouse anti-γH2AX (1:500 dilution; Millipore #05-636), mouse anti-MLH1 (1:50 dilution; BD Biosciences #550838), rabbit anti-HSPA2 (1:200 dilution; Abclonal #A7902), mouse anti- CDK1(1:200 dilution; Abcam #ab18), mouse anti- PLK1 (1:200 dilution, BD Pharmingen #pT210), MSCDK (1:200 dilution; homemade). Primary antibodies were detected with Alexa Fluor 488-, 594-, or 647-conjugated secondary antibodies (1:500 dilution, Thermo Fisher Scientific #A-11070, Abcam #ab150084, #ab150067, #ab150113, #ab150120, #ab150119, #ab150165, #ab150168, and #ab150167) for 1 h at room temperature. The slides were washed several times with PBS and mounted using VECTASHIELD medium with DAPI (Vector Laboratories, #H-1200).

2.7. In vitro assay

Purified His-MSCDK (WT) was incubated with cyclin B1/CDK1 (Invitrogen, #PV3292), with or without PP1a (Merck Millipore, #14-595) at 4°C overnight. The reaction samples were subjected to SDS-PAGE and blotted with indicated antibodies. Purified His-MSCDK wild-type (WT)/ MSCDK Mutation (S135A; S149A) protein was incubated with cyclin B1/CDK1 at 4°C overnight. The reaction samples were subjected to SDS-PAGE and blotted with indicated antibodies.

2.8. Western Blotting

To prepare extracts, tissues were collected from male C57BL/6 mice and suspended in lysis buffer described before (16). After homogenization, the cell extracts were centrifuged at 20,000 × g for 20 min at 4°C. The supernatant extracts were used for Western blots. Equal amounts of protein were electrophoresed on 10% Bis-Tris Protein Gels, and the bands were transferred to polyvinylidene fluoride membranes (Millipore). Immunoreactive bands were detected and analyzed with a BIO-RAD ChemiDoc MP Imaging System and Image Lab Software (BIO-RAD). The primary antibodies for immunoblotting included anti-β-actin (1:1,000 dilution; Cell Signaling Technology, #4970), rabbit anti-Lamin B1 (1:2000 dilution; Proteintech, #12987-1-AP), rabbit anti-α-Tubulin (1:2000 dilution; Proteintech, #11224-1-AP), and anti-MSCDK (1:1,000 dilution; produced as described above).

2.9. Generation of plasmids

Full-length cDNAs encoding Mscdk and Hspa2 were amplified by RT-PCR from murine testis RNA. Full-length cDNAs were cloned into the PCAG and PCMV6 mammalian expression vectors.

2.10. Immunoprecipitation and antibodies

HEK 293T cells were transiently transfected using X-tremeGENE HP DNA Transfection Reagent (Roche). Transfected cells were lysed in TAP lysis buffer (50 mM HEPES-KOH, pH 7.5, 100 mM KCl, 2 mM EDTA, 10% glycerol, 0.1% NP-40, 10 mM NaF, 0.25 mM Na3VO4, 50 mM β-glycerolphosphate) plus protease inhibitors (Roche, #04693132001) for 30 min on ice and then centrifuged at 13,000 × g for 15 min. The antibody was added and the mixture was rotated in Eppendorf tubes at 4°C overnight, and immunocomplexes were isolated by adsorption to protein A/G Sepharose beads for 1 h. After washing, the beads were loaded onto 10% Bis-Tris Protein Gels (Invitrogen), and separated proteins were detected by western blotting with the indicated antibodies. Immunoprecipitations were performed using rabbit anti-GFP antibody (Proteintech, #50430-2-AP) and mouse anti-FLAG antibody (Sigma-Aldrich, #F1804,). Primary antibodies used for western blotting were mouse anti-FLAG antibody (1:1,000 dilution; Sigma-Aldrich, #F1804), and rabbit anti-GFP antibody (1:5000 dilution; Proteintech, #50430-2-AP). Secondary horseradish peroxidase-conjugated anti-mouse (Zhong Shan Jin Qiao) and anti-rabbit (Zhong Shan Jin Qiao) antibodies were used at 1:5,000 dilution. Antibodies were detected with the Immobilon Western Chemiluminescent HRP Substrate from Millipore.

2.11. Imaging

Immunolabeled chromosome spreads were imaged by confocal microscopy using a Leica TCS SP5 resonant-scanning confocal microscope driven by Leica. Application Suite Software, or an Andor Dragonfly spinning disc confocal microscope driven by Fusion Software. Projection images were then prepared using ImageJ Software (NIH, Ver. 1.6.0-65) or Bitplane Imaris (version8.1) software. Histology were analyzed with an epifluorescence microscope (BX52, Olympus),and processed using Photoshop (Adobe) software packages. SIM analysis was performed with Acquire SR software on a DeltaVision OMX SR super resolution imaging system (GE Healthcare) equipped with a 60x/1.42 oil objective, and the images were further computationally reconstructed and processed with softWoRx software (GE Healthcare) to generate super resolution optical series sections with two-fold extended resolution in both xy and z axes.

2.12. Phosphoproteomic analysis

The samples were ground into cell powder under liquid nitrogen and added to the lysis buffer with inhibitors. The protein solution was reduced with 5 mM dithiothreitol for 30 min at 56 °C and alkylated with 11 mM iodoacetamide for 15 min at room temperature in darkness. The protein sample was then diluted by adding 100 mM TEAB to a final urea concentration of less than 2M. Finally, trypsin was added at 1:50 trypsin-to-protein mass ratio for the first digestion overnight and 1:100 trypsin-to-protein mass ratio for a second 4 h-digestion. After trypsin digestion, peptides were desalted using a Strata X C18 SPE column (Phenomenex) and vacuum-dried. Peptides were then reconstituted in 0.5 M TEAB and processed according to the manufacturer’s protocols for TMT kit/iTRAQ kit. Briefly, one unit of TMT/iTRAQ reagent was thawed and reconstituted in acetonitrile. The peptide mixtures were then incubated for 2 h at room temperature and pooled, desalted, and dried by vacuum centrifugation. Then affinity enrichment and LC-MS/MS Analysis.

2.13. Statistical analysis

The statistical significance of the differences between the mean values for the different genotypes was measured by Welch’s t-test with a paired, 2-tailed distribution. The data were considered significant when the p-value was less than 0.001(***).

3. RESULTS and DISCUSSION

3.1. Expression of the meiosis- specific Mscdk gene in mice

Through mRNA sequencing of mouse male germ cells, we identified a highly transcribed gene in meiosis prophase I encoded by

1700102P08Rik, which we subsequently named

Mscdk (meiotic substrate of cyclin dependent kinase)

. Mscdk was specifically expressed in the adult testes, the organs where meiotic prophase I occurs (

Figure 1A). More specifically, the

Mscdk mRNA was only expressed in testes that had entered meiosis (

Figure 1B). To determine the subcellular localization of MSCDK, we developed a polyclonal antibody against MSCDK and performed western blotting of cytoplasmic and nuclear fractions. This revealed that MSCDK is present in both the cytoplasmic and nuclear fractions prepared from mouse testes extracts, indicating that MSCDK may potentially function in both the cytoplasm and nuclei (

Figure 1C).

3.2. Dynamic localization of MSCDK to SCs

To further investigate functional roles of MSCDK, we carried out a detailed immunofluorescence analysis of mouse spermatocyte spreads using double labeling with antibodies against MSCDK and against the classic SC lateral element marker SYCP3 (17). In wild-type spermatocytes, MSCDK was expressed as distinct foci along the axes of synapsed chromosomes from the early zygotene to the early diplotene stage (

Figure 1D, white arrow). Note that MSCDK protein accumulation increased sharply in spermatocytes starting from the late zygotene stage up to the mid-pachytene stages, after which it gradually decreased. The pseudoautosomal region (PAR) was also labeled positively for MSCDK on the XY bivalent (

Figure 1D, yellow arrow) (18). As the spermatocytes progressed into the early diplotene stage, the MSCDK signals disappeared at the de-synapsed regions but remained on the synapsed chromosomes (

Figure 1D, inset). By the late diplotene stage, no MSCDK foci were detected (

Figure 1D). Collectively, our results strongly suggest that MSCDK has functions related to the assembly and disassembly of the SC.

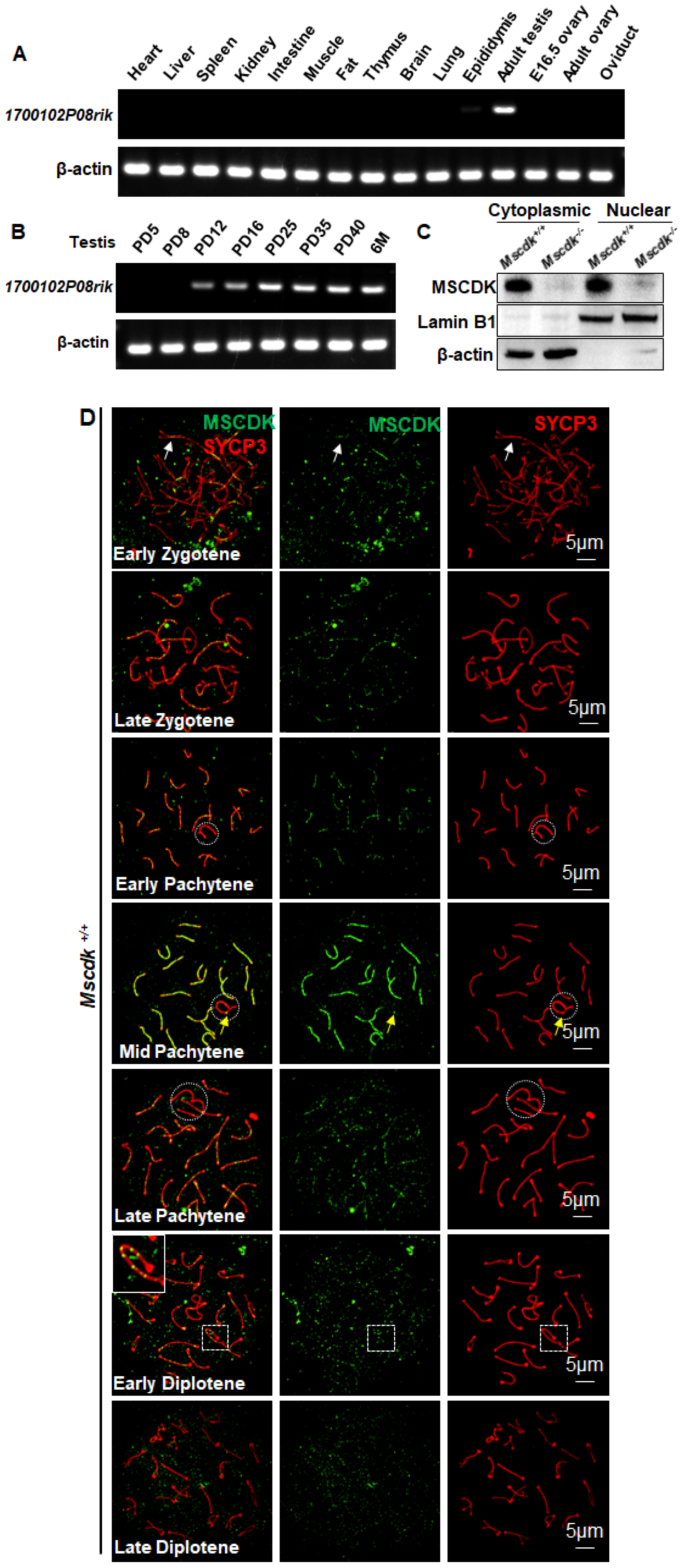

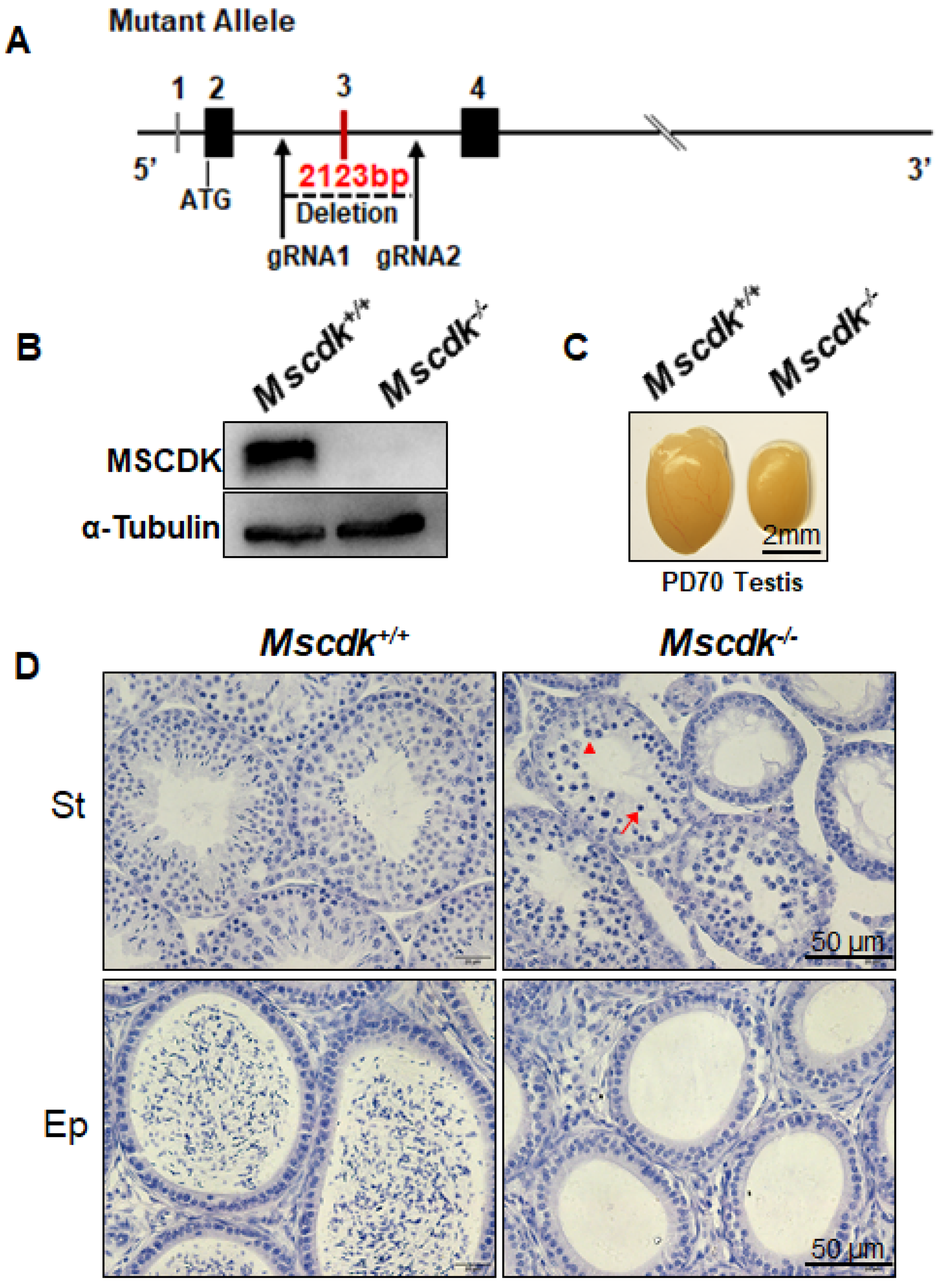

3.3. MSCDK is needed for maintaining fertility in a sex-dependent manner

To investigate the functions of MSCDK, we generated a

Mscdk knockout mouse line using CRISPR/Cas9. The

Mscdk gene locus comprises 4 exons, with an ATG start codon at the 5

th nt of the 405 bp exon 2 and a TGA stop codon in exon 4. The DNA fragment that was deleted in our

Mscdk−/− mice is 2123 bp in length and contains exon 3 (

Figure 2A). Western blotting confirmed the absence of the MSCDK protein in

Mscdk−/− testes (

Figure 2B). We also confirmed the immunofluorescence specificity of the antibody against MSCDK in

Mscdk-/- spermatocytes, and no MSCDK was detected (

Supplemental Figure S1B). Offspring resulting from crosses of heterozygous (

Mscdk+/−) male and female mice exhibited a normal Mendelian distribution of genotypes, and

Mscdk−/− mice were viable and exhibited no clear difference from wild type during development. Despite their largely normal outward appearance,

Mscdk−/− males had very small testes and were found to be completely infertile (

Figure 2C,

Supplemental Figure S2A). We observed the difference in testes size as early as postnatal day 18 (PD18), the point in mouse development when the first wave of spermatocytes are ready to leave the pachytene stage (

Supplemental Figure S2B).

Histological analysis of

Mscdk−/− testes showed that the spermatogenesis was blocked at epithelial stage IV, and most of the spermatocytes arrested at the pachytene stage (

Figure 2D). Although some spermatocytes did continue developing past epithelial stage IV, these had all become non-viable by epithelial stage XII (

Figure 2D, arrowhead). In

Mscdk−/− males, the seminiferous tubules lacked post-meiotic spermatocytes and contained apoptotic cells (

Figure 2D, arrow). Furthermore, no spermatozoa were observed in the

Mscdk−/− epididymis (

Figure 2D). Collectively, these results establish that MSCDK is essential for spermatogenesis in mice. In contrast to males, the fertility of

Mscdk−/− females was found to be indistinguishable from

Mscdk+/- females, with comparable numbers of pups (

Supplemental Figure S2C). Additionally, no clear morphological differences were identified between the ovaries of PD19

Mscdk−/− and those of

Mscdk+/+ ovaries (

Supplemental Figure S2D).

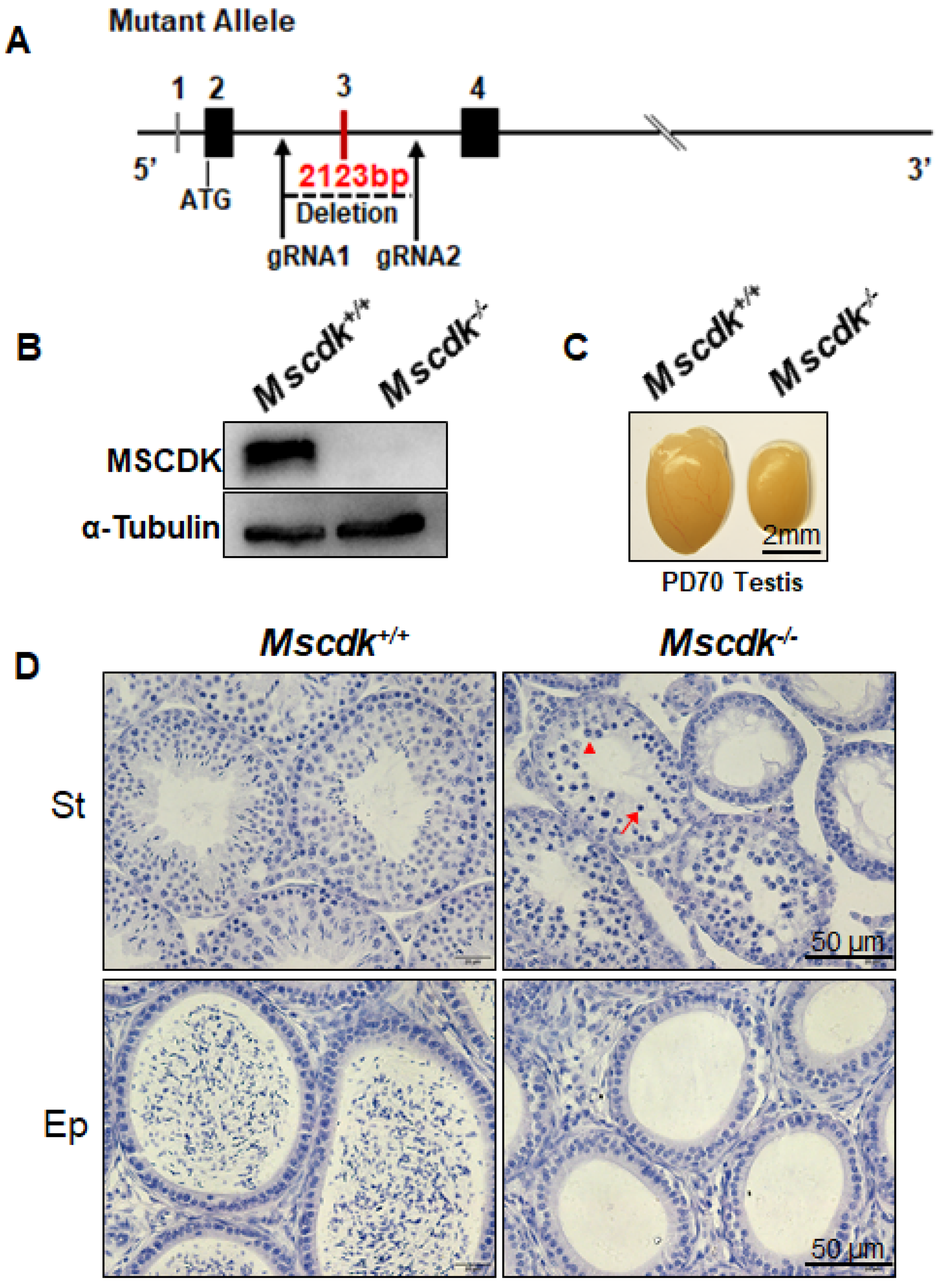

3.4. MSCDK is essential for synaptonemal complex disassembly during the pachytene stage

Seeking to determine the reason for the observed disruption of meiosis in

Mscdk−/− spermatocytes, we monitored the process of chromosomal synapsis by assessing the distribution of the central element components (

e.g., SYCP1) and axial elements (

e.g., SYCP3) of the SCs (19). Fundamentally, these analyses suggested that deficiency for MSCDK did not affect the structure of SC. Specifically, we found that mice of both the

Mscdk−/− and

Mscdk+/+ genotypes exhibited spermatocytes with indistinguishable morphologies from the leptotene stage to the metaphase I stage (

Figure 3A). We also used high resolution structured illumination microscopy (SIM) to observe fine SC structures (which cannot otherwise be distinguished using confocal microscopy) and thusly found that lateral elements in both Mscdk

-/- and Mscdk

+/+ spermatocytes appeared as two separate strands (SYCP3 immunostaining;

Supplemental Figure S3A). SYCP1 occurs as a homodimer, and the N-termini of SYCP1 dimers have been shown to localize to the central region of the SC, whereas their C-termini localizes to lateral regions (20): analyses with N-terminus- and C-terminus-specific antibodies revealed the expected SYCP1 localization trends in both

Mscdk-/- and

Mscdk+/+ spermatocytes at all of the meiosis stages we examined (

Supplemental Figure S3A, B.

Having excluded any obvious impacts of MSCDK deletion on the structure of the SC, we next quantified spermatocytes at different meiotic stages from PD19, PD37, and PD70 for both

Mscdk−/− and

Mscdk+/+ testes in order to more precisely pinpoint the stage at which meiosis disruption occurs in

Mscdk-/- mice (

Figure 3B). In

Mscdk-/- mice, the process of spermiogenesis was apparently slowed down compared with that of

Mscdk+/+ mice, that is, most spermatocytes showed arrest in the pachytene stage, with fewer than 20% of the spermatocytes capable of development beyond the pachytene stage, and all of which had become non-viable by metaphase I. These results confirm that MSCDK is essential for orderly spermiogenesis during meiosis prophase I.

3.5. Mscdk−/− spermatocytes exhibited no obvious defects in DSB repair or crossover formation.

It has long been known that during meiosis SPO11-catalyzed DSBs trigger the phosphorylation of H2AX through activation of the ATM kinase (21,22). We were thus interested in examining the process of DSB repair and meiotic recombination in spermatocyte spreads; however, these analyses revealed no obvious differences between the

Mscdk−/− and

Mscdk+/+ spermatocytes. In both genotypes, the γH2AX signals had all disappeared from autosomes but were still present at XY bodies at the pachytene stage (

Supplementary Figure S4A), indicating that DSB repair is apparently not affected by the lack of MSCDK in adult

Mscdk−/− spermatocytes. We further explored the distribution of proteins involved in recombination but observed no significant differences in the number of RPA2, RAD51, or MLH1 foci between

Mscdk−/− and

Mscdk+/+ spermatocytes from the leptotene to pachytene stages (

Figure 3C, D;

Supplementary Figure S4B, C) (23-25). Thus, MSCDK does not ostensibly cause meiotic arrest by disruption of DSB repair or recombination.

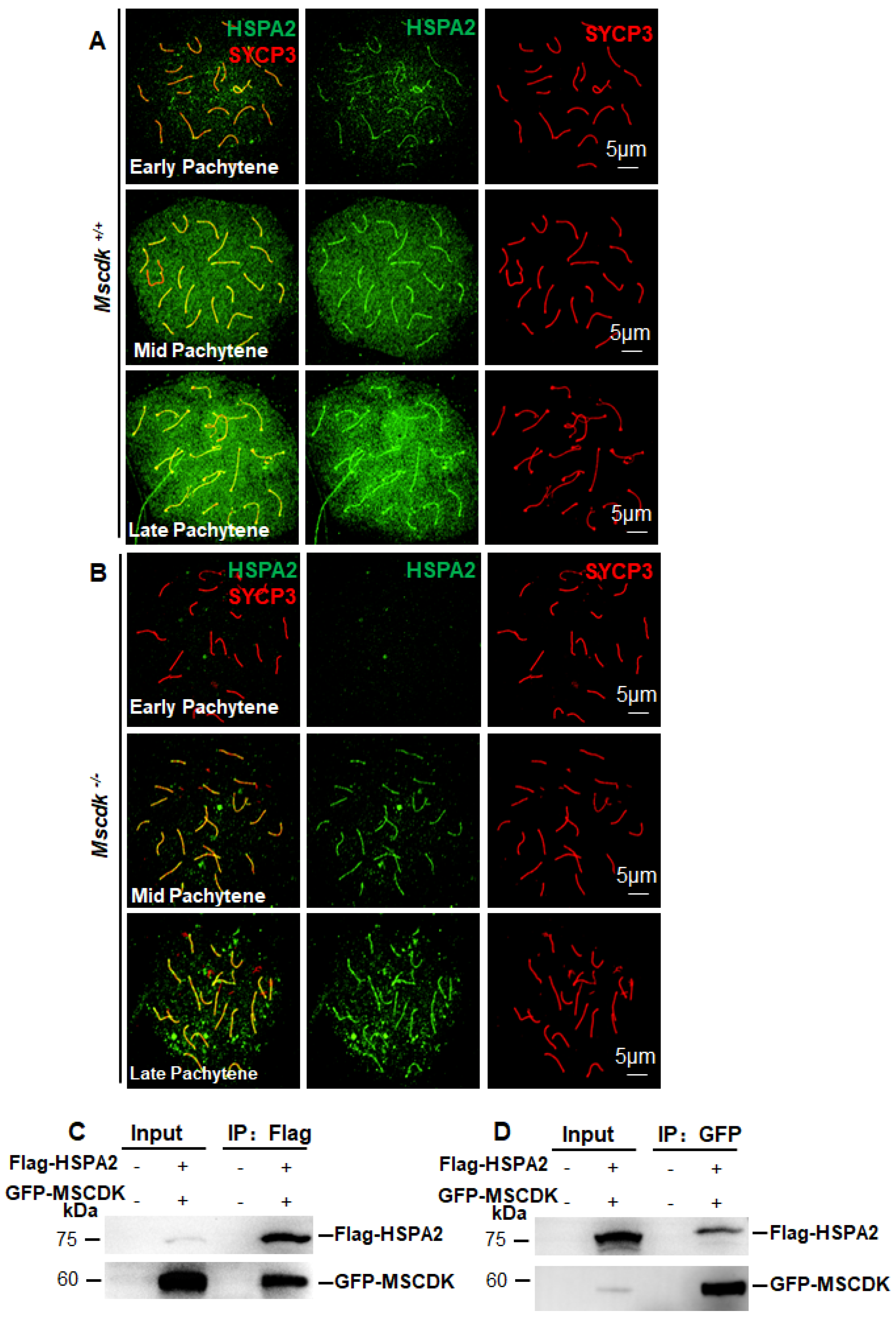

3.6. MSCDK may function in the positive-feedback-driven HSPA2 recruitment during the pachytene stage

As MSCDK apparently plays no significant role in DSB repair or recombination, we explored potential roles of MSCDK in SC disassembly and in pachytene exit. Previous studies have shown that SC disassembly requires the spermatocyte-specific chaperone heat shock related 70 kDa protein 2 (HSPA2) (4,7,8). We therefore speculated that MSCDK may function in SC disassembly. Supporting this, we double labeled

Mscdk-/- and

Mscdk+/+ spermatocytes with specific antibodies against HSPA2 and SYCP3 and found that in

Mscdk+/+ spermatocytes HSPA2 foci are apparent on chromosomal axes beginning at the early pachytene stage and gradually accumulate in the nucleus from the early pachytene stage to the late pachytene stage (

Figure 4A). In contrast, in

Mscdk-/- spermatocytes HSPA2 foci did not appear until the mid-pachytene stage, and the overall number of HSPA2 foci in the pachytene stage were obviously decreased compared with

Mscdk+/+ spermatocytes (

Figure 4B).

These results collectively support the idea that chromosomal-axis-localized MSCDK may promote HSPA2 recruitment to the SC during the early to mid-pachytene stage—possibly by increasing the protein stability of HSPA2— and we suspect that the function of MSCDK may help ensure that there is an adequate nuclear population of HSPA2 during the late pachytene stage to support SC disassembly. Supporting this, we performed Co-IP experiments which showed that Flag-HSPA2 was able to pull down GFP-MSCDK (

Figure 4C) and

vice versa (

Figure 4D). These findings demonstrate a capacity for MSCDK to directly physically interact with HSPA2, providing a plausible mechanism to explain our observations of differential HSPA2 foci at the chromosome axes during different phases of the pachytene stage. Pushing these ideas further—in light of reports about the self-assembly process underlying SC extension during this stage (26)—it is possible that MSCDK somehow facilitates a positive-feedback-driven accumulation/recruitment process for HSPA2 that ultimately promotes SC disassembly.

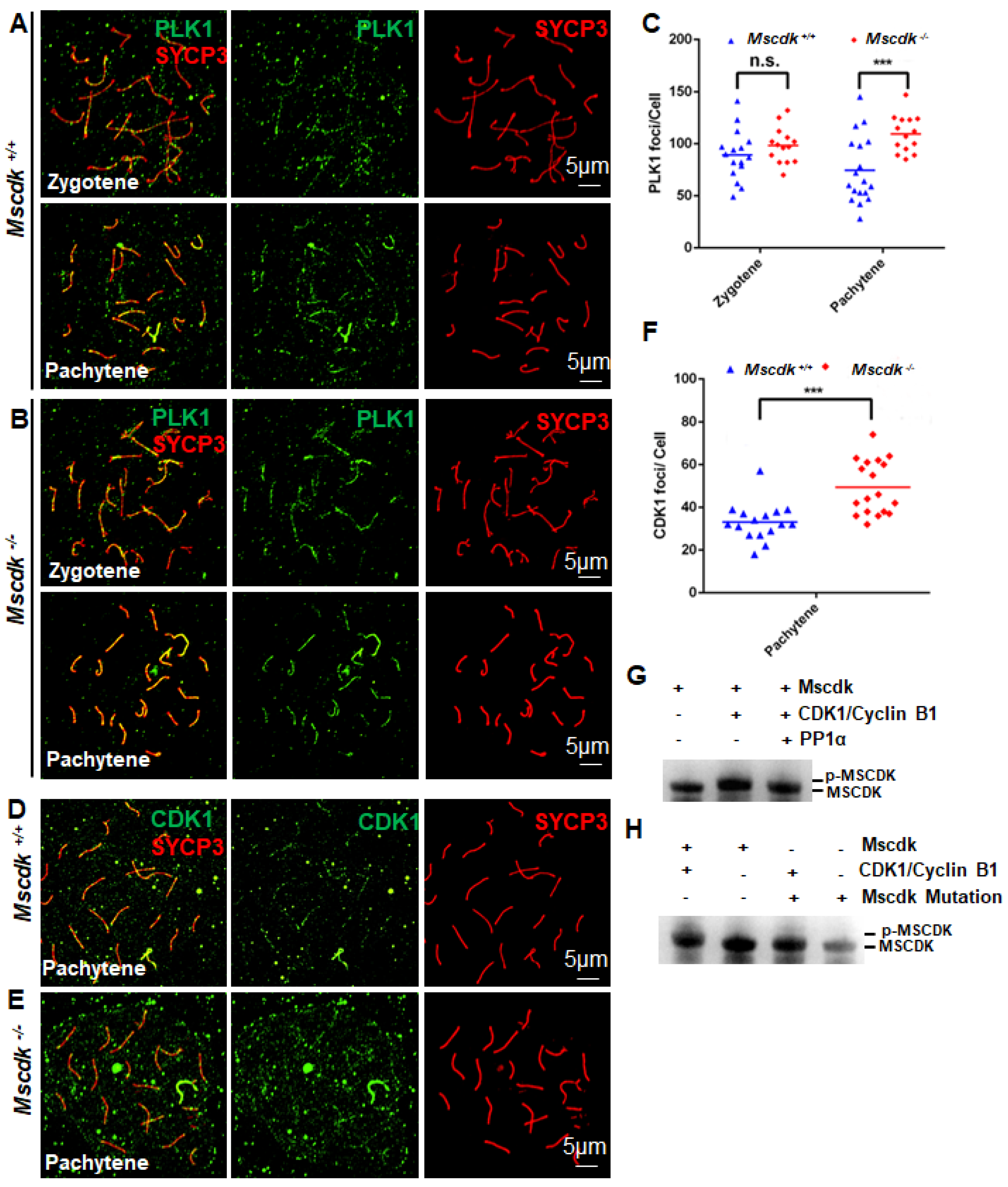

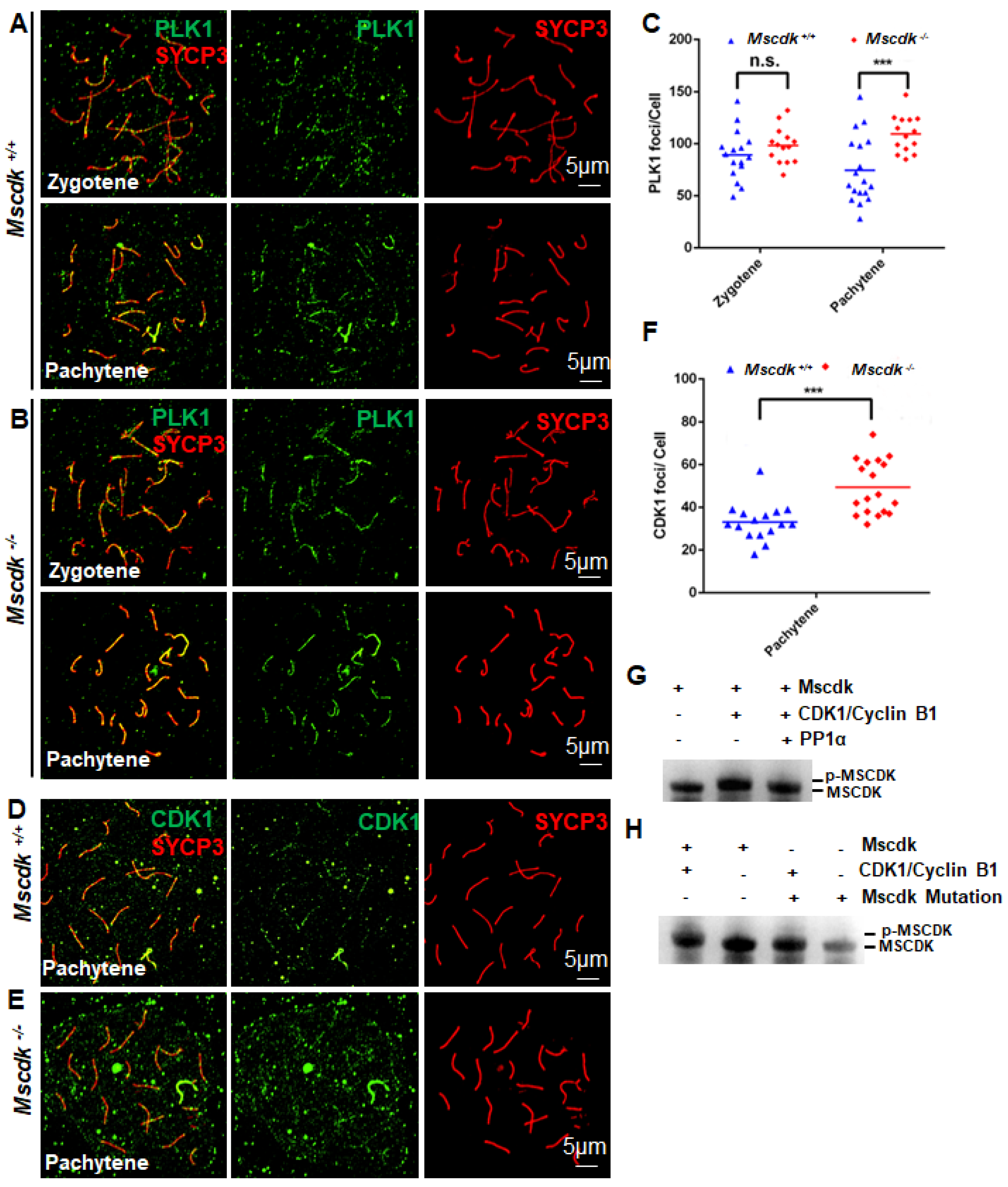

SC disassembly in mice is also reported to require PLK1 (6). To determine if this process was impacted in

Mscdk-/- mice, we also performed double labeling of SYCP3 and PLK1 in wild-type and

Mscdk−/− spermatocytes and found significantly more pachytene stage PLK1 foci in

Mscdk-/- spermatocytes than in the wild type (

Figure 5A-C). This result provides additional evidence that the defects in SC disassembly in the

Mscdk-/- spermatocytes are not contributed by the PLK1-mediated pathway, but is probably a result of an interrupted HSPA2-mediated pathway.

3.7. CDK-catalyzed MSCDK phosphorylation regulates synaptonemal complex disassembly and meiosis M-phase transition

Recall that the formation of highly condensed metaphase I bivalents and SC disassembly are both regulated by the CDK1/cyclin B1 complex, the assembly of which is controlled through interactions with HSPA2 (11). We observed a sharp decrease in the number of HSPA2 foci in the pachytene stage in

Mscdk-/- spermatocytes. Moreover, we detected CDK1 recruitment to the SC in both

Mscdk-/- and

Mscdk+/+ spermatocytes: for both genotypes there were extensive CDK1 foci by the mid-pachytene stage, when crossover formation has finished (immediately prior to SC disassembly) (

Figure 5D, E). We quantified the number of CDK1 foci in both genotypes and notably found that there were significantly more CDK1 foci in

Mscdk-/- spermatocytes (

Figure 5F). This result was surprising, because a previous study showed that, in the absence of HSPA2, recruitment of CDK1 and assembly of CDK1/cyclin B1 complex at SCs is sharply decreased.

It is challenging to conceptually resolve this apparent discrepancy in the role of nuclear HSPA2 in CDK1/cyclin B1 complex formation in pachytene spermatocytes, but our aforementioned speculations about the HSPA2-recruiting function of MSCDK may shed informative light on this issue. We propose that early pachytene stage nuclei have SC-localized HSPA2 that can activate CDK1, after which CDK1 may mediate the phosphorylation-based activation of other meiotic factors. These factors potentially function to promote the further nuclear recruitment of HSPA2, which may then expedite SC disassembly. We carried out

in vitro kinase assays to pursue this line of reasoning. When the CDK1/cyclin B1 complex was incubated with purified MSCDK, wild-type MSCDK was phosphorylated, indicated by an upward shift in its western blot migration pattern (

Figure 5G), and thereby showing that MSCDK may be a phosphorylation substrate of CDK1. Previous work has shown that many phosphorylation substrates of the master cell cycle regulator CDK1 are subsequently dephosphorylation substrates of the cell cycle exit regulator PP1α (27), so we were not entirely surprised when we found through further

in vitro enzymatic assays that PP1α can dephosphorylate p-MSCDK (

Figure 5G). We predicted through group-based prediction system (

http://gps.biocuckoo.cn/online.php) that MSCDK is potentially phosphorylated at two Serine residues (S135A; S149A). We mutated these Ser residues to alanine and observed no changes in shifting of the MSCDK band following

in vitro enzymatic assays (

Figure 5H). Together, these results establish that CDK1 can catalyze MSCDK phosphorylation and show that PP1a functions as a phosphatase to dephosphorylate MSCDK, thereby regulating SC disassembly and the Metaphase I transition.

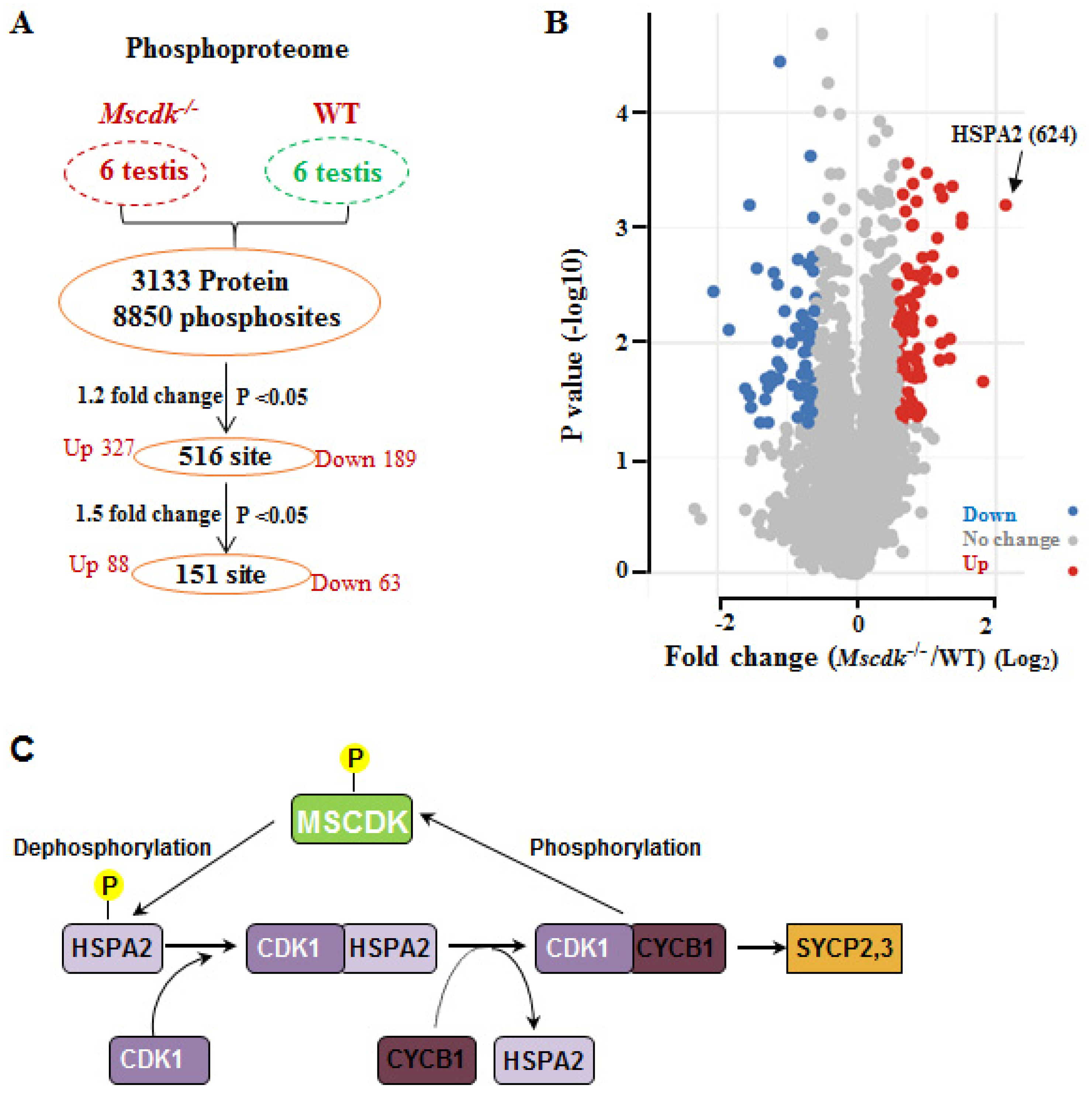

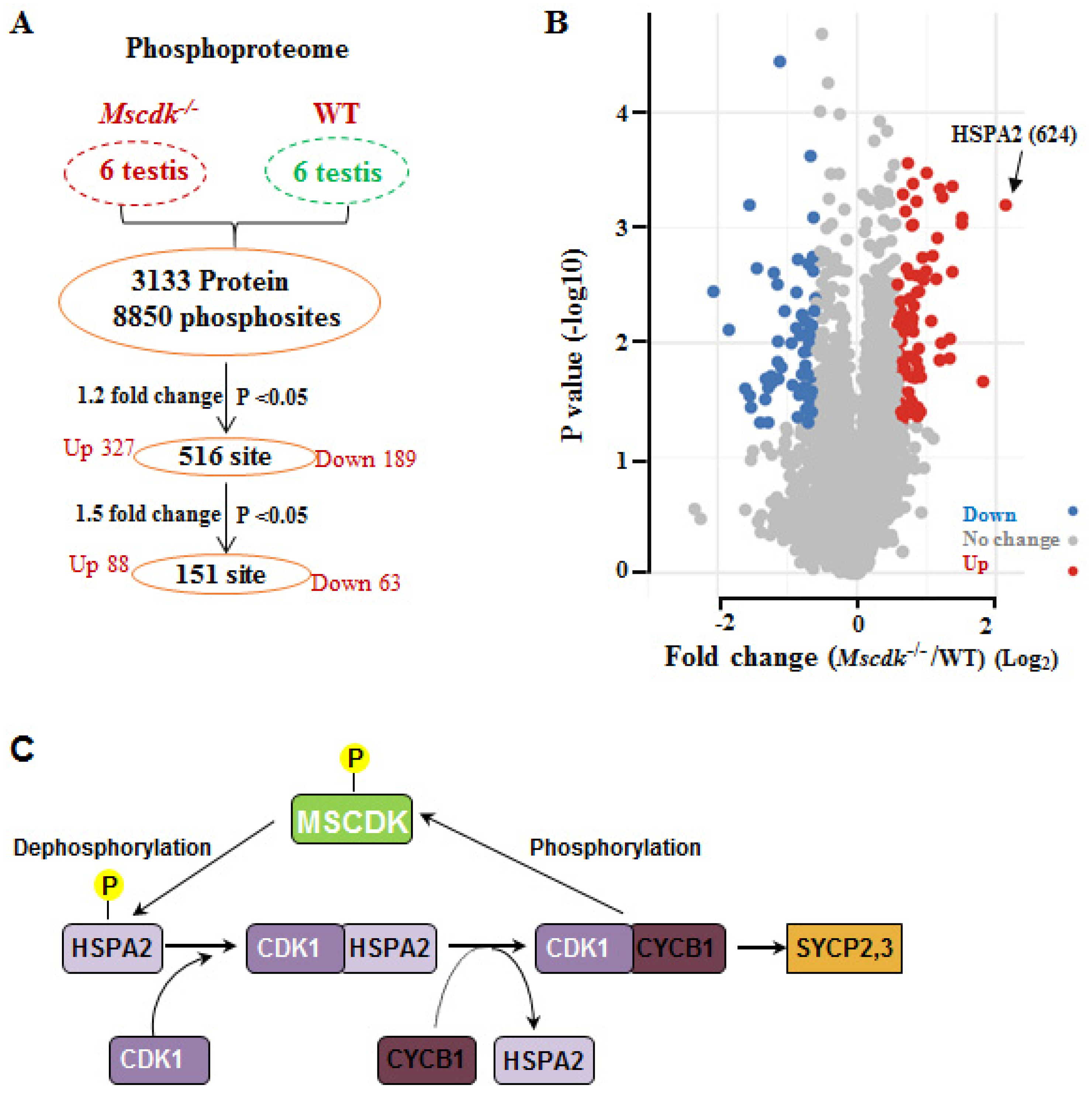

3.8. The phosphorylation level of HSPA2 serine 624 is 4-fold higher in Mscdk-/- testes

In light of our finding that MSCDK is a substrate of the master cell cycle regulator CDK1/ cyclin B1 complex, we performed phospho-proteomics analysis of

Mscdk-/- and wild type testes from PD19 mice. A total of 8850 phosphosites and 3133 proteins was quantified in all six subjects (

Figure 6A, B;

Supplementary Table S1). Compared with wild type testes, there were 516 significantly differentially phosphorylated residues (p<0.05, fold change>1.2), with 327 residues having increased phosphorylation and 189 residues having decreased phosphorylation in the

Mscdk-/- testes (

Figure 6A, B); and 151 phosphorylated residues (p<0.05, fold change>1.5), with 88 residues having increased phosphorylation and 63 residues having decreased phosphorylation in the

Mscdk-/- testes (

Figure 6A, B) . Gene ontology analysis and KEGG analysis identified germ cell development related pathway as the most highly enriched pathway (including genes such as

Hspa2;

Hfm1;

Setx; Tdrd9; Map7; Tesmin, etc.) (Supplementary Figure 5A). Strongly supporting a role for MSCDK in dephosphorylation, we found that the phosphorylation level of HSPA2 residue 624 was increased by more than 4-fold in

Mscdk-/- testes compared with wild type testes, the largest change we observed across the entire phospho-proteome (

Figure 6B, C;

Supplementary Table S1). These results provide evidence supporting the participation of MSCDK in the dephosphorylation of multiple proteins previously established to participate in germ cell development, with an especially pronounced impact on the dephosphorylation of HSPA2, which functions to promote the further nuclear recruitment of HSPA2, thus expediting SC disassembly.

4. CONCLUSION

In summary, our immunofluorescence analyses reveal that MSCDK localizes to the SC from the early zygotene to the early diplotene stage. Upon deletion of MSCDK, although the formation of crossovers in

Mscdk-/- spermatocytes is not obviously affected, clear defects are induced in the SC disassembly that result in infertility in male but not female mice. Moreover, we observed nuclear accumulation of CDK1 while its chaperone protein HSPA2, which is essential for its activation, decreased significantly. This finding apparently contradicts the spatiotemporal trends reported in previous studies. Further,

in vitro phosphorylation assays showed that MSCDK can be phosphorylated by the master cell cycle entry kinase CDK1 and can be dephosphorylated by the cell cycle exit regulator phosphatase PP1α. We also found through global mass spectrometry of the phosphoproteomes of wild type and

Mscdk-/- testes that HSPA2 undergoes a ∼four-fold increase in phosphorylation. We thus proposed a potential model in which SC-localized HSPA2 can activate CDK1 in early pachytene stage nuclei, after which CDK1 may mediate the phosphorylation-based activation of MSCDK. MSCDK then likely dephosphorylates HSPA2 to promote the further nuclear recruitment of HSPA2, demonstrating that MSCDK participates in regulation of SC disassembly (

Figure 6C).

The number of pachytene PLK1 foci increased significantly in the Mscdk-/- spermatocytes compared with Mscdk+/+. Recall the relationship between CDK1 and PLK1 in mitosis in which PLK1 is activated via Aurora A in a CDK1/Cyclin A-dependent manner, leading us to propose that the increased levels of PLK1 during meiosis may be a result of a concomitant increase in CDK1 (12,13). Alternatively, the increase in PLK1 may be a compensatory phenotype related to defects of the HSPA2-mediated SC disassembly mechanism. Thus, the relationship between CDK1 and PLK1 in meiosis still requires further study. The sex-specific functions of MSCDK in male vs. female germ cells also merits consideration. In mammals, exit from meiotic prophase exhibits significant sexual dimorphism: mice spermatocytes (as well as budding yeast) proceed directly from pachynema into diplonema. In oocytes, meiotic prophase is arrested in a diplotene-like dictyate stage, and such arrest can last for months (in laboratory mice) or decades (in humans). Ultimately, obtaining a deeper understanding of the functional mechanisms underlying HSPA2-CDK1-MSCDK interactions will be particularly informative in delineating the sex-specific functional aspects of gametogenesis.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at the website of this paper posted on Preprints.org.

Author Contributions

HB.L. and H.T conceived and designed the entire project. HB.L., H.T. and L.G. designed and supervised the research. MJ.L. and MY.Z. performed most of the experiments. MY.Z. and HZ. L. performed the co-immunoprecipitation and data analysis. MJ.L., T.H., HB.L., Chan Wai-yee and JL.M. wrote the manuscript, with contributions from all authors. All authors discussed the results and commented on the manuscript.

Funding

This work was supported by the National Key R&D Program(2021YFC2700500); Research Unit of Gametogenesis and Health of ART-Offspring, Chinese Academy of Medical Sciences(2020RU001). Major Innovation Projects in Shandong Province (2021ZDSYS16) and the Science Foundation for Distinguished Yong Scholars of Shandong (ZR2021JQ27).

Institutional Review Board Statement

All experiments involving animals were conducted according to the ethical policies and procedures approved by the Animal Ethics Committee of the School of Medicine of Shandong University.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

References

- Gerton, J.L.; Hawley, R.S. Homologous chromosome interactions in meiosis: diversity amidst conservation. Nat Rev Genet 2005, 6, 477–487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- de Massy, B. Initiation of meiotic recombination: how and where? Conservation and specificities among eukaryotes. Annu Rev Genet 2013, 47, 563–599. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cahoon, C.K.; Hawley, R.S. Regulating the construction and demolition of the synaptonemal complex. Nat Struct Mol Biol 2016, 23, 369–377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhu, D.; Dix, D.J.; Eddy, E.M. HSP70-2 is required for CDC2 kinase activity in meiosis I of mouse spermatocytes. Development 1997, 124, 3007–3014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gopinathan, L.; Szmyd, R.; Low, D.; Diril, M.K.; Chang, H.Y.; Coppola, V.; Liu, K.; Tessarollo, L.; Guccione, E.; van Pelt, A.M.M.; et al. Emi2 Is Essential for Mouse Spermatogenesis. Cell Rep 2017, 20, 697–708. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jordan, P.W.; Karppinen, J.; Handel, M.A. Polo-like kinase is required for synaptonemal complex disassembly and phosphorylation in mouse spermatocytes. J Cell Sci 2012, 125, 5061–5072. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dix, D.J.; Allen, J.W.; Collins, B.W.; Mori, C.; Nakamura, N.; Poorman-Allen, P.; Goulding, E.H.; Eddy, E.M. Targeted gene disruption of Hsp70-2 results in failed meiosis, germ cell apoptosis, and male infertility. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 1996, 93, 3264–3268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dix, D.J.; Allen, J.W.; Collins, B.W.; Poorman-Allen, P.; Mori, C.; Blizard, D.R.; Brown, P.R.; Goulding, E.H.; Strong, B.D.; Eddy, E.M. HSP70-2 is required for desynapsis of synaptonemal complexes during meiotic prophase in juvenile and adult mouse spermatocytes. Development 1997, 124, 4595–4603. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allen, J.W.; Dix, D.J.; Collins, B.W.; Merrick, B.A.; He, C.; Selkirk, J.K.; Poorman-Allen, P.; Dresser, M.E.; Eddy, E.M. HSP70-2 is part of the synaptonemal complex in mouse and hamster spermatocytes. Chromosoma 1996, 104, 414–421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sourirajan, A.; Lichten, M. Polo-like kinase Cdc5 drives exit from pachytene during budding yeast meiosis. Genes Dev 2008, 22, 2627–2632. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, F.; Handel, M.A. Regulation of the meiotic prophase I to metaphase I transition in mouse spermatocytes. Chromosoma 2008, 117, 471–485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Thomas, Y.; Cirillo, L.; Panbianco, C.; Martino, L.; Tavernier, N.; Schwager, F.; Van Hove, L.; Joly, N.; Santamaria, A.; Pintard, L.; et al. Cdk1 Phosphorylates SPAT-1/Bora to Promote Plk1 Activation in C. elegans and Human Cells. Cell Rep 2016, 15, 510–518. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gheghiani, L.; Loew, D.; Lombard, B.; Mansfeld, J.; Gavet, O. PLK1 Activation in Late G2 Sets Up Commitment to Mitosis. Cell Rep 2017, 19, 2060–2073. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vigneron, S.; Sundermann, L.; Labbe, J.C.; Pintard, L.; Radulescu, O.; Castro, A.; Lorca, T. Cyclin A-cdk1-Dependent Phosphorylation of Bora Is the Triggering Factor Promoting Mitotic Entry. Dev Cell 2018, 45, 637–650. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Peters, A.H.; Plug, A.W.; van Vugt, M.J.; de Boer, P. A drying-down technique for the spreading of mammalian meiocytes from the male and female germline. Chromosome Res 1997, 5, 66–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, H.; Huang, T.; Li, M.; Li, M.; Zhang, C.; Jiang, J.; Yu, X.; Yin, Y.; Zhang, F.; Lu, G.; et al. SCRE serves as a unique synaptonemal complex fastener and is essential for progression of meiosis prophase I in mice. Nucleic Acids Res 2019, 47, 5670–5683. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yuan, L.; Liu, J.G.; Zhao, J.; Brundell, E.; Daneholt, B.; Hoog, C. The murine SCP3 gene is required for synaptonemal complex assembly, chromosome synapsis, and male fertility. Mol Cell 2000, 5, 73–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kauppi, L.; Barchi, M.; Baudat, F.; Romanienko, P.J.; Keeney, S.; Jasin, M. Distinct properties of the XY pseudoautosomal region crucial for male meiosis. Science 2011, 331, 916–920. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Vries, F.A.; de Boer, E.; van den Bosch, M.; Baarends, W.M.; Ooms, M.; Yuan, L.; Liu, J.G.; van Zeeland, A.A.; Heyting, C.; Pastink, A. Mouse Sycp1 functions in synaptonemal complex assembly, meiotic recombination, and XY body formation. Genes Dev 2005, 19, 1376–1389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaniecki, K.; De Tullio, L.; Greene, E.C. A change of view: homologous recombination at single-molecule resolution. Nat Rev Genet 2018, 19, 191–207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baudat, F.; Manova, K.; Yuen, J.P.; Jasin, M.; Keeney, S. Chromosome synapsis defects and sexually dimorphic meiotic progression in mice lacking Spo11. Mol Cell 2000, 6, 989–998. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bellani, M.A.; Romanienko, P.J.; Cairatti, D.A.; Camerini-Otero, R.D. SPO11 is required for sex-body formation, and Spo11 heterozygosity rescues the prophase arrest of Atm-/- spermatocytes. J Cell Sci 2005, 118, 3233–3245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pittman, D.L.; Cobb, J.; Schimenti, K.J.; Wilson, L.A.; Cooper, D.M.; Brignull, E.; Handel, M.A.; Schimenti, J.C. Meiotic prophase arrest with failure of chromosome synapsis in mice deficient for Dmc1, a germline-specific RecA homolog. Mol Cell 1998, 1, 697–705. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ashley, T.; Plug, A.W.; Xu, J.; Solari, A.J.; Reddy, G.; Golub, E.I.; Ward, D.C. Dynamic changes in Rad51 distribution on chromatin during meiosis in male and female vertebrates. Chromosoma 1995, 104, 19–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Baker, S.M.; Plug, A.W.; Prolla, T.A.; Bronner, C.E.; Harris, A.C.; Yao, X.; Christie, D.M.; Monell, C.; Arnheim, N.; Bradley, A.; et al. Involvement of mouse Mlh1 in DNA mismatch repair and meiotic crossing over. Nat Genet 1996, 13, 336–342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dunce, J.M.; Dunne, O.M.; Ratcliff, M.; Millan, C.; Madgwick, S.; Uson, I.; Davies, O.R. Structural basis of meiotic chromosome synapsis through SYCP1 self-assembly. Nat Struct Mol Biol 2018, 25, 557–569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ceulemans, H.; Bollen, M. Functional diversity of protein phosphatase-1, a cellular economizer and reset button. Physiol Rev 2004, 84, 1–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Figure 1.

Transcriptional analysis and distribution of MSCDK in mouse meiocytes. (A) RT-PCR detection of Mscdk transcripts in various tissues, indicating that Mscdk was specifically expressed in adult testes. (B) Levels of Mscdk mRNA in developing testes. (C) Western blotting of cytoplasmic and nuclear fractions of PD35 wild-type testes, using an anti-MSCDK antibody developed for this study, showing that MSCDK is localized in the nucleus and the cytoplasm. Lamin B1 was used as the marker protein for nuclear fraction and β-actin was used as marker for the cytoplasmic fraction. (D) Immunofluorescence analysis showing the dynamic localization of MSCDK to SCs in mouse spermatocytes. MSCDK localized to the chromosomal axes as distinct foci, starting from the early zygotene stage and persisting until the late diplotene stage.

Figure 1.

Transcriptional analysis and distribution of MSCDK in mouse meiocytes. (A) RT-PCR detection of Mscdk transcripts in various tissues, indicating that Mscdk was specifically expressed in adult testes. (B) Levels of Mscdk mRNA in developing testes. (C) Western blotting of cytoplasmic and nuclear fractions of PD35 wild-type testes, using an anti-MSCDK antibody developed for this study, showing that MSCDK is localized in the nucleus and the cytoplasm. Lamin B1 was used as the marker protein for nuclear fraction and β-actin was used as marker for the cytoplasmic fraction. (D) Immunofluorescence analysis showing the dynamic localization of MSCDK to SCs in mouse spermatocytes. MSCDK localized to the chromosomal axes as distinct foci, starting from the early zygotene stage and persisting until the late diplotene stage.

Figure 2.

Generation of Mscdk−/− mice and analysis of gonad morphology. (A) Schematic representation of the genome editing strategy for the Mscdk locus, showing the gRNAs (arrows), the corresponding coding exons (black and red thick lines), and the non-coding exons (grey thick lines). Red thick lines (coding exons) represent the 2123 bp fragment that was selectively deleted from the wild-type Mscdk allele. ATG, initiation codon. (B) Western blotting of PD35 Mscdk−/− testes indicating that knockout mice produced no MSCDK. α-tubulin was used as the loading control. (C) Mscdk−/− male mice had reduced testis size at PD70 (n = 5 wild-type and knockout mice, Welch’s t-test analysis: p < 0.0001). (D) Mscdk−/− male mice had almost complete arrest of spermatogenesis in epithelial stage IV, as shown by hematoxylin staining of testis sections. The arrow indicates a spermatocyte exhibiting apoptotic morphology. A small quantity of spermatocytes survived epithelial stage IV but then died before the end of epithelial development; the arrowhead indicates a post-metaphase I spermatocyte. The epididymides of knockout mice were empty when examined at PD35. (St) Seminiferous tubules, (Ep) Epididymides.

Figure 2.

Generation of Mscdk−/− mice and analysis of gonad morphology. (A) Schematic representation of the genome editing strategy for the Mscdk locus, showing the gRNAs (arrows), the corresponding coding exons (black and red thick lines), and the non-coding exons (grey thick lines). Red thick lines (coding exons) represent the 2123 bp fragment that was selectively deleted from the wild-type Mscdk allele. ATG, initiation codon. (B) Western blotting of PD35 Mscdk−/− testes indicating that knockout mice produced no MSCDK. α-tubulin was used as the loading control. (C) Mscdk−/− male mice had reduced testis size at PD70 (n = 5 wild-type and knockout mice, Welch’s t-test analysis: p < 0.0001). (D) Mscdk−/− male mice had almost complete arrest of spermatogenesis in epithelial stage IV, as shown by hematoxylin staining of testis sections. The arrow indicates a spermatocyte exhibiting apoptotic morphology. A small quantity of spermatocytes survived epithelial stage IV but then died before the end of epithelial development; the arrowhead indicates a post-metaphase I spermatocyte. The epididymides of knockout mice were empty when examined at PD35. (St) Seminiferous tubules, (Ep) Epididymides.

Figure 3.

MSCDK is essential for orderly spermatogenesis progression. (A) Double immunofluorescence labeling of spermatocyte spreads of wild-type and Mscdk−/− spermatocytes with antibodies against SYCP3 (red) and SYCP1 (green). (B) Spermatocytes at different meiotic stages were quantified from Mscdk+/+ and Mscdk−/− testes at PD19, PD37, and PD70. (C) Mscdk +/+ and Mscdk−/− spermatocytes stained against SYCP3 (red) and MLH1 (green). (D) Quantities of MLH1 foci in Mscdk +/+ and Mscdk−/− spermatocytes.

Figure 3.

MSCDK is essential for orderly spermatogenesis progression. (A) Double immunofluorescence labeling of spermatocyte spreads of wild-type and Mscdk−/− spermatocytes with antibodies against SYCP3 (red) and SYCP1 (green). (B) Spermatocytes at different meiotic stages were quantified from Mscdk+/+ and Mscdk−/− testes at PD19, PD37, and PD70. (C) Mscdk +/+ and Mscdk−/− spermatocytes stained against SYCP3 (red) and MLH1 (green). (D) Quantities of MLH1 foci in Mscdk +/+ and Mscdk−/− spermatocytes.

Figure 4.

MSCDK is essential for HSPA2 nuclear recruitment during the pachytene stage. (A) Spermatocyte nuclei from a Mscdk+/+ mouse with immunolabeling of SYCP3 and HSPA2. (B) Spermatocyte nuclei from a Mscdk−/− mouse with immunolabeling of SYCP3 and HSPA2. (C, D) A co-IP experiment detecting the interaction between MSCDK and HSPA2. HEK293T cells were co-transfected with the indicated tagged expression vectors. After 48h, the cell lysates were immunoprecipitated with anti-Flag (C) and anti-GFP (D) antibodies.

Figure 4.

MSCDK is essential for HSPA2 nuclear recruitment during the pachytene stage. (A) Spermatocyte nuclei from a Mscdk+/+ mouse with immunolabeling of SYCP3 and HSPA2. (B) Spermatocyte nuclei from a Mscdk−/− mouse with immunolabeling of SYCP3 and HSPA2. (C, D) A co-IP experiment detecting the interaction between MSCDK and HSPA2. HEK293T cells were co-transfected with the indicated tagged expression vectors. After 48h, the cell lysates were immunoprecipitated with anti-Flag (C) and anti-GFP (D) antibodies.

Figure 5.

CDK1 and PLK1 accumulate on chromosomal axes in Mscdk-/- spermatocytes during the pachytene stage. (A, B) Double immunofluorescence labeling of spermatocyte spreads of wild-type (A) and Mscdk−/− (B) spermatocytes with antibodies against SYCP3 (red) and PLK1 (green). (C) Quantitation of PLK1 foci in wild-type and Mscdk−/− spermatocytes during the zygotene and the pachytene stages. Student's t-test, p<0.001 (***). (D, E) Double immunofluorescence labeling of spermatocyte spreads of wild-type (D) and Mscdk−/− (E) spermatocytes with antibodies against SYCP3 (red) and CDK1 (green). (F) Quantification of CDK1 foci in wild-type and Mscdk−/− spermatocytes during pachytene stages; Student's t-test, p < 0.001 (***). (G) An in vitro phosphorylation assay performed with purified proteins (MSCDK (WT), PP1a, and the CDK1/cyclin B1 complex). Various protein mixtures (as indicated in the figure) were subjected to western blotting with an anti-MSCDK antibody. p-MSCDK refers to the phosphorylated form of MSCDK. (H) An in vitro phosphorylation assay performed with purified proteins (MSCDK (WT), MSCDK Mutation (S135A; S149A) and the CDK1/cyclin B1 complex). Various protein mixtures (as indicated in the figure) were subjected to western blotting with an anti-MSCDK antibody. p-MSCDK refers to the phosphorylated form of MSCDK.

Figure 5.

CDK1 and PLK1 accumulate on chromosomal axes in Mscdk-/- spermatocytes during the pachytene stage. (A, B) Double immunofluorescence labeling of spermatocyte spreads of wild-type (A) and Mscdk−/− (B) spermatocytes with antibodies against SYCP3 (red) and PLK1 (green). (C) Quantitation of PLK1 foci in wild-type and Mscdk−/− spermatocytes during the zygotene and the pachytene stages. Student's t-test, p<0.001 (***). (D, E) Double immunofluorescence labeling of spermatocyte spreads of wild-type (D) and Mscdk−/− (E) spermatocytes with antibodies against SYCP3 (red) and CDK1 (green). (F) Quantification of CDK1 foci in wild-type and Mscdk−/− spermatocytes during pachytene stages; Student's t-test, p < 0.001 (***). (G) An in vitro phosphorylation assay performed with purified proteins (MSCDK (WT), PP1a, and the CDK1/cyclin B1 complex). Various protein mixtures (as indicated in the figure) were subjected to western blotting with an anti-MSCDK antibody. p-MSCDK refers to the phosphorylated form of MSCDK. (H) An in vitro phosphorylation assay performed with purified proteins (MSCDK (WT), MSCDK Mutation (S135A; S149A) and the CDK1/cyclin B1 complex). Various protein mixtures (as indicated in the figure) were subjected to western blotting with an anti-MSCDK antibody. p-MSCDK refers to the phosphorylated form of MSCDK.

Figure 6.

CDK-catalyzed MSCDK phosphorylation regulates synaptonemal complex disassembly and the meiosis M-phase transition. (A) Schematic diagram showing the PD19 mouse testes, Mscdk-/- testes and WT testes for phosphoproteomics (2 testes per group, 3 replicates) and post-proteomic data analyses. (B) A global, mass-spectrometry-based phospho-proteome analysis showed that compared with wild type testes, the Mscdk−/− mice had significantly increased phosphorylation for 88 residues and had significantly decreased phosphorylation for 63 residues (1.5-fold change, p <0.05). The largest detected difference between the wild type and Mscdk−/− mice was for HSPA2 residue 624. (C) The regulation of CDK1 activation in meiotic prophase I occurs through control of timing for CDK1 interaction with the chaperone protein HSPA2 (formerly HSP70-2), which must occur before CDK1 can interact with Cyclin B1. The activated CDK1 phosphorylates MSCDK, which dephosphorylates HSPA2, further promoting HSPA2 recruitment to the synaptonemal complex and initiating SC disassembly. Deletion of MSCDK, which acts as a substrate of CDK1, disrupts the feedback-driven dephosphorylation/recruitment of HSPA2 and contributes to the accumulation of CDK1 and PLK1 in spermatocytes.

Figure 6.

CDK-catalyzed MSCDK phosphorylation regulates synaptonemal complex disassembly and the meiosis M-phase transition. (A) Schematic diagram showing the PD19 mouse testes, Mscdk-/- testes and WT testes for phosphoproteomics (2 testes per group, 3 replicates) and post-proteomic data analyses. (B) A global, mass-spectrometry-based phospho-proteome analysis showed that compared with wild type testes, the Mscdk−/− mice had significantly increased phosphorylation for 88 residues and had significantly decreased phosphorylation for 63 residues (1.5-fold change, p <0.05). The largest detected difference between the wild type and Mscdk−/− mice was for HSPA2 residue 624. (C) The regulation of CDK1 activation in meiotic prophase I occurs through control of timing for CDK1 interaction with the chaperone protein HSPA2 (formerly HSP70-2), which must occur before CDK1 can interact with Cyclin B1. The activated CDK1 phosphorylates MSCDK, which dephosphorylates HSPA2, further promoting HSPA2 recruitment to the synaptonemal complex and initiating SC disassembly. Deletion of MSCDK, which acts as a substrate of CDK1, disrupts the feedback-driven dephosphorylation/recruitment of HSPA2 and contributes to the accumulation of CDK1 and PLK1 in spermatocytes.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).