Submitted:

25 April 2023

Posted:

26 April 2023

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Landfill Gas Generation Investigation Approaches

3. Materials and Methods

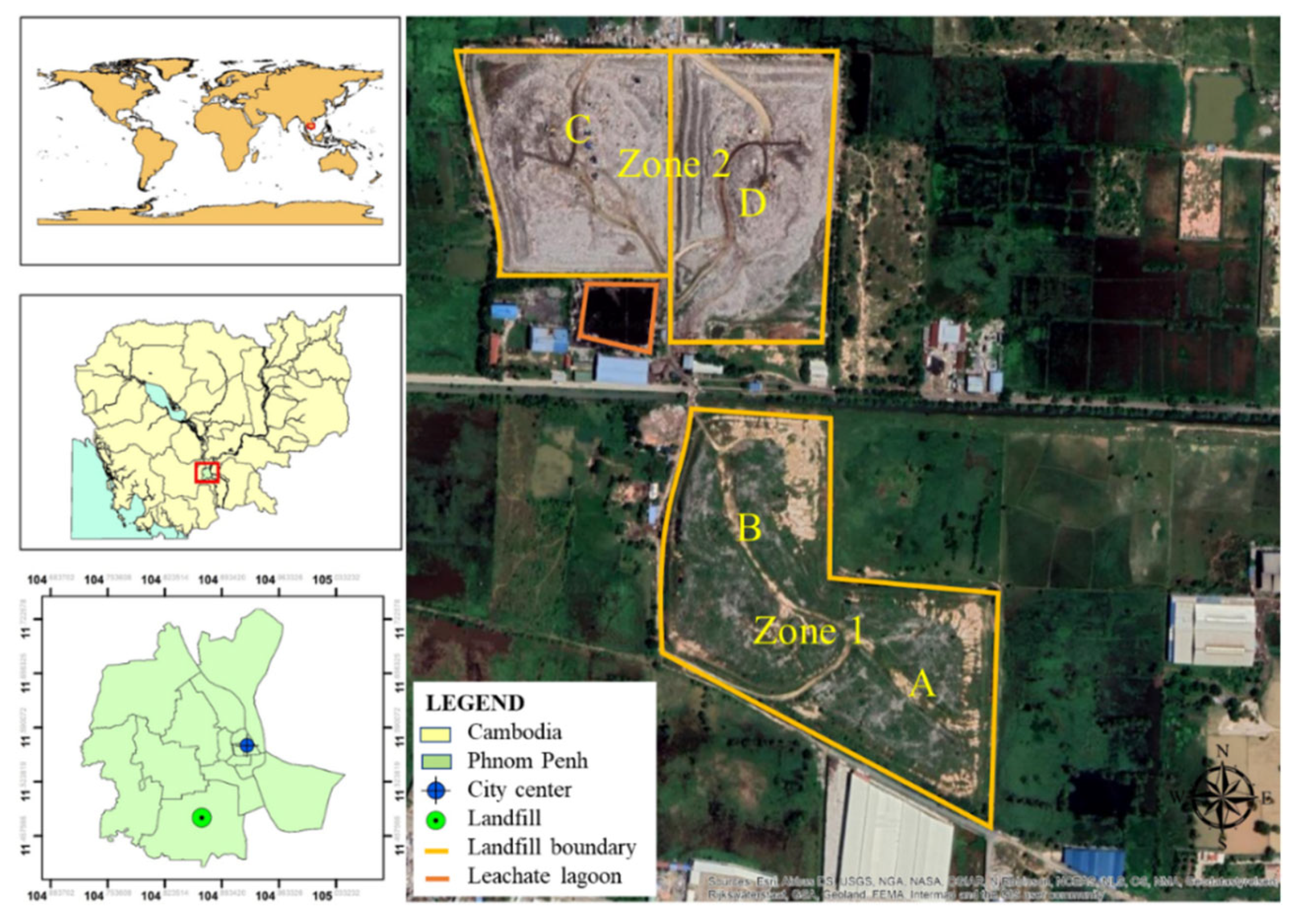

3.1. Study Area

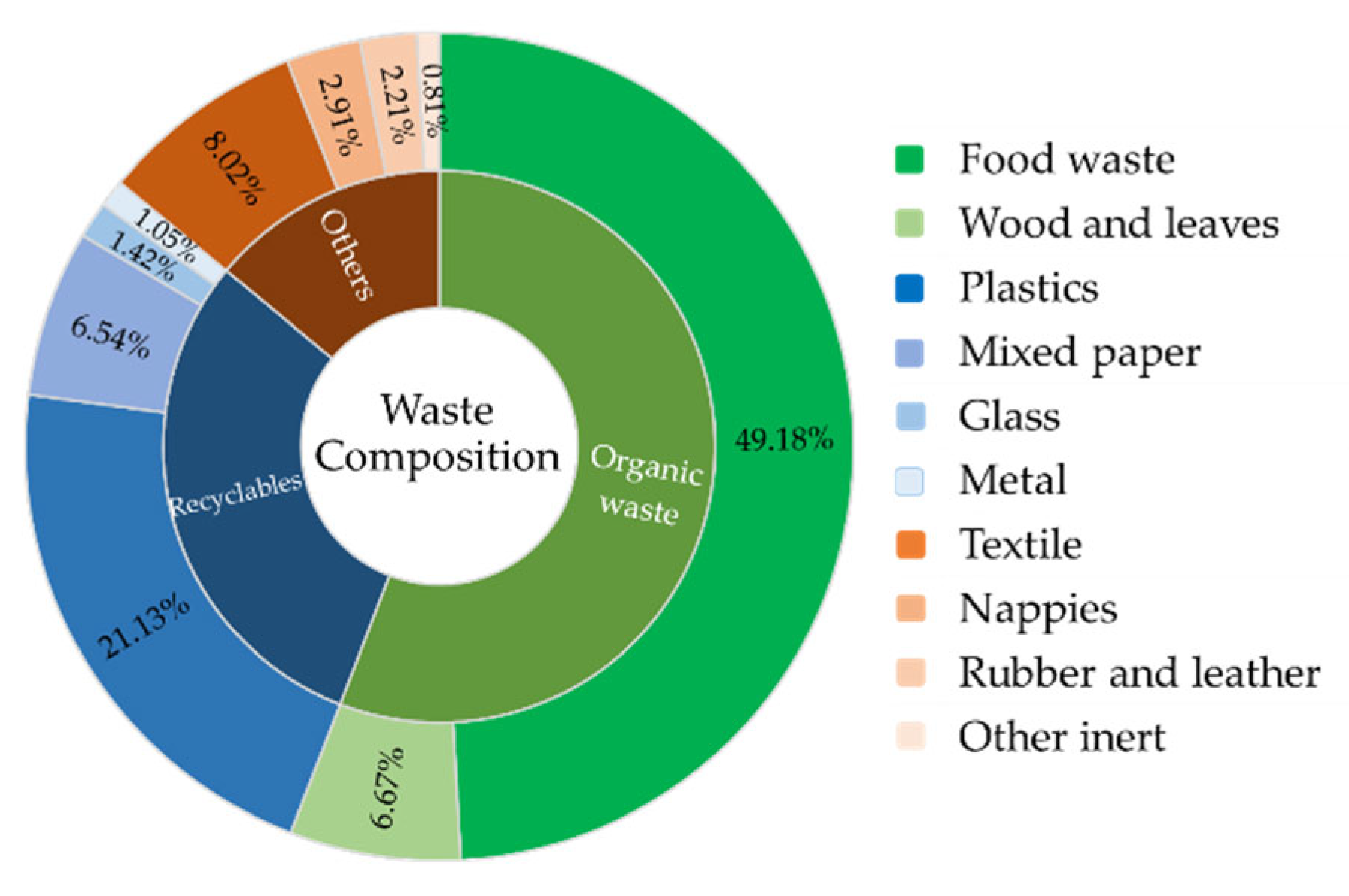

3.2. Data Collection

3.3. Landfill Management Scenarios

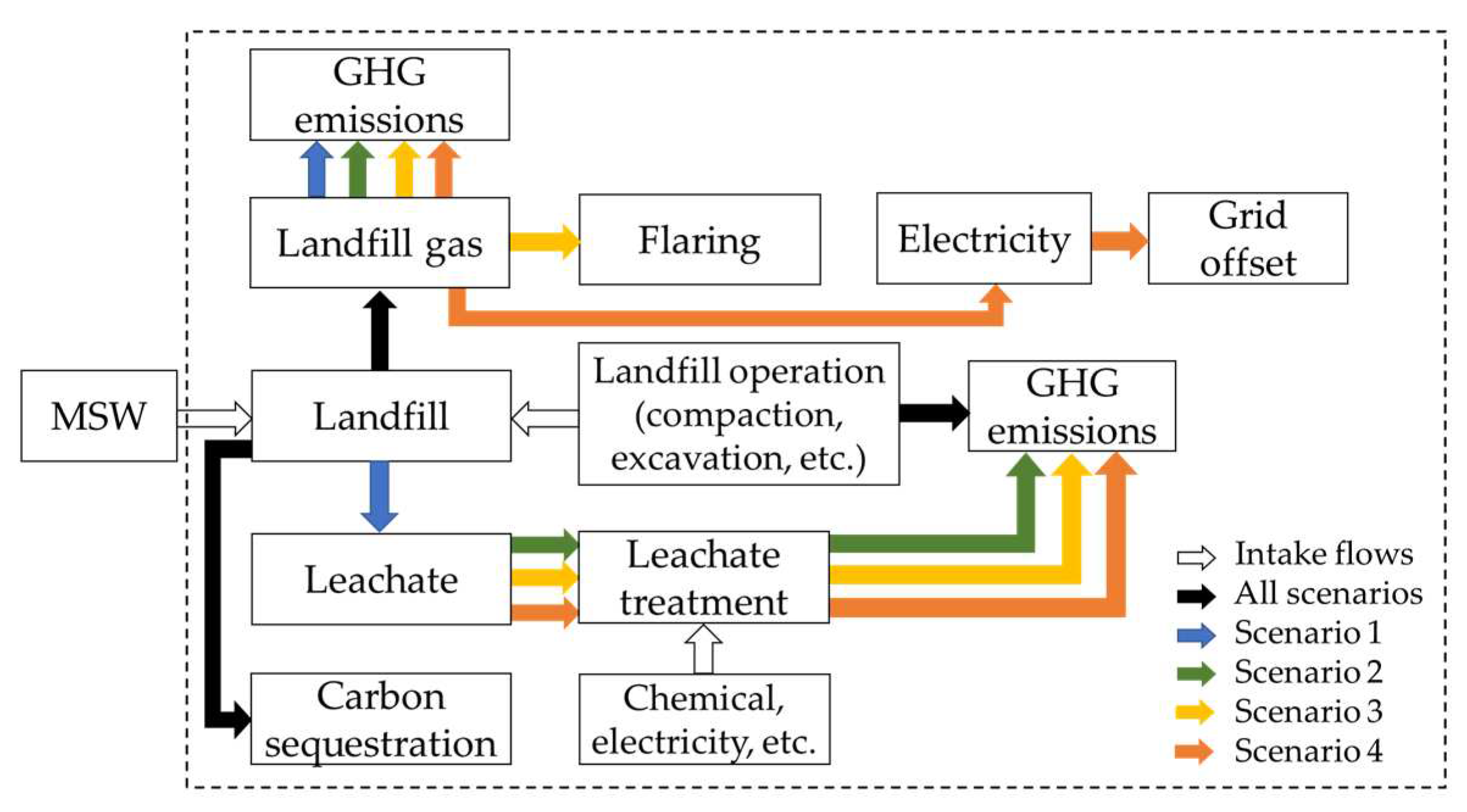

3.4. Calculation of LFG Generation

3.4.1. LandGEM Model

3.4.2. IPCC FOD Model

3.5. Calculation of Energy Recovery Potential

3.6. Calculation of Overall GHG Emissions

3.6.1. Fugitive CH4 Emissions

3.6.2. Avoided Emissions from Carbon Sequestration

3.6.3. N2O Emissions

3.6.4. Emissions from Landfill Operation

3.6.5. Emissions from Leachate Treatment

3.6.6. Calculation of Avoided Emissions from Electricity Substitution

3.6.7. Calculation of Overall Emissions from Landfill Management Technologies

3.7. Determination of Uncertainty in CH4 Emissions Estimation

4. Results and Discussion

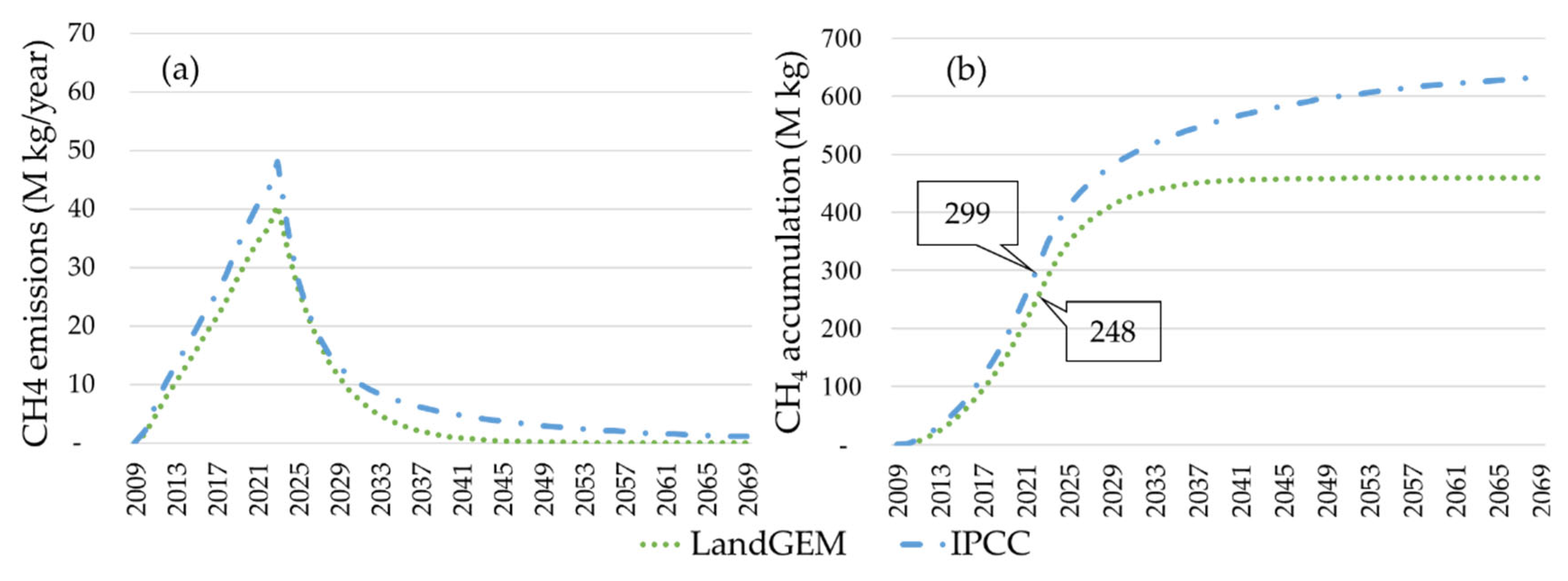

4.1. Estimation of CH4 Generation

4.2. Estimation of Energy Recovery Potential from LFG Recovery

4.3. Quantification of Emission Factors for Different Landfill Scenarios

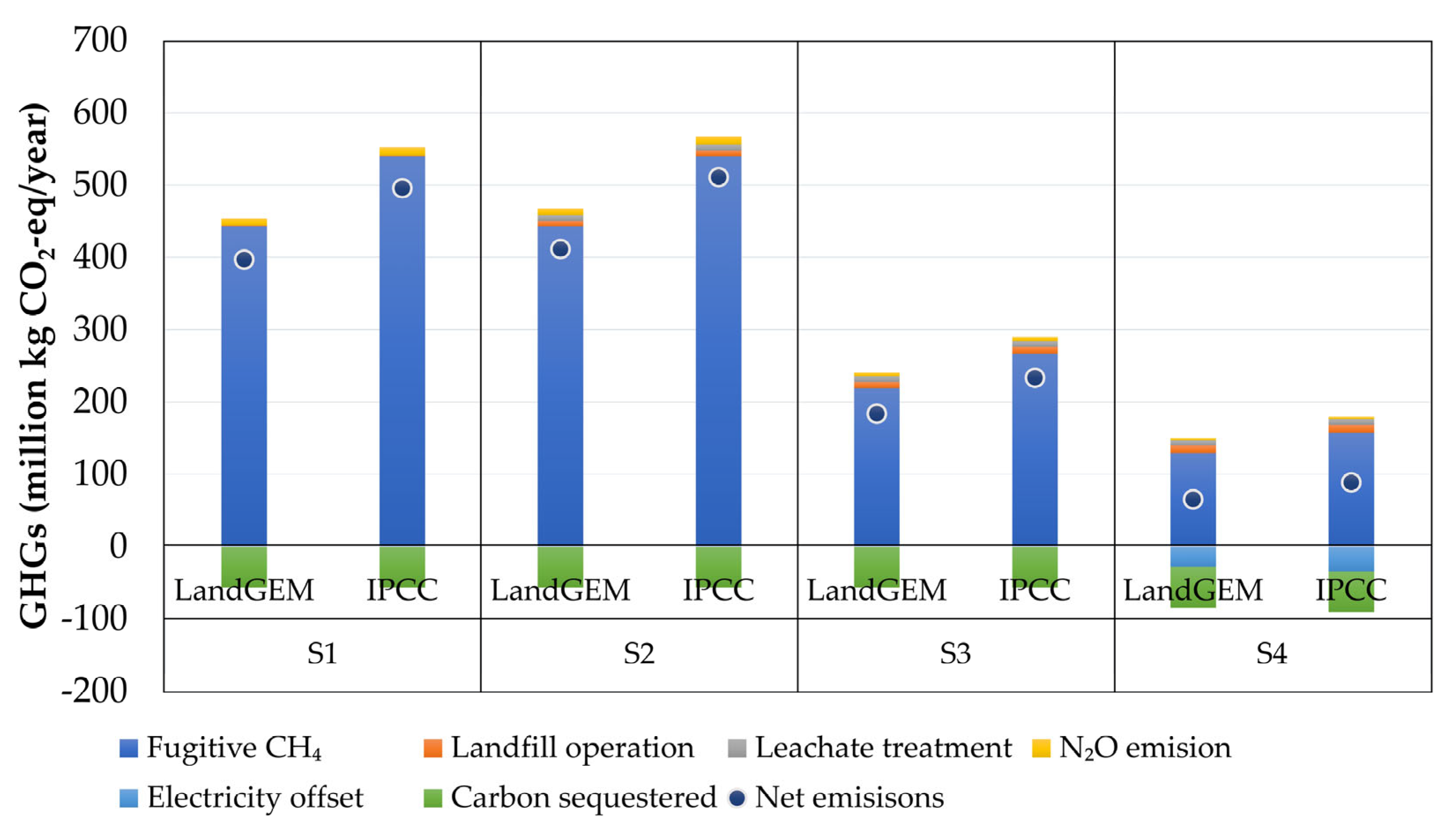

4.4. Overall GHG Emissions from 2009 to 2022

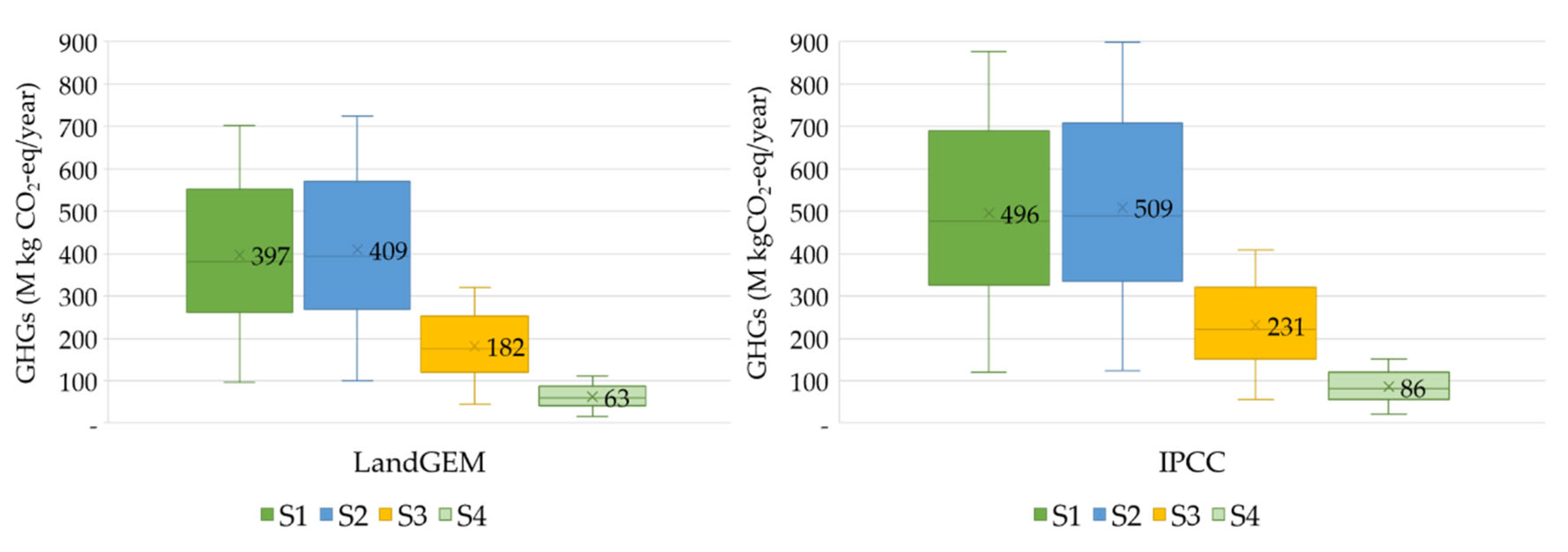

4.5. Uncertainty Assessment

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Amini, H.R.; Reinhart, D.R.; Niskanen, A. Comparison of First-Order-Decay Modeled and Actual Field Measured Municipal Solid Waste Landfill Methane Data. Waste Manag. 2013, 33, 2720–2728. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Machado, S.L.; Carvalho, M.F.; Gourc, J.P.; Vilar, O.M.; do Nascimento, J.C.F. Methane Generation in Tropical Landfills: Simplified Methods and Field Results. Waste Manag. 2009, 29, 153–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bogner, J.; Ahmed, M.A.; Diaz, C.; Faaij, A.; Gao, Q.; Hashimoto, S.; et al. Waste Management, in Climate Change 2007: Mitigation. Contribution of Working Group III to the Fourth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change. Metz, B., Davidson, O.R., Bosh, P.R., Dave, R., Meyer. L.A., Eds; Cambridge University Press: United Kingdom and New York, NY, USA, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change. 2006 IPCC Guidelines for National Greenhouse Gas Inventories, Prepared by the National Greenhouse Gas Inventories Programme; Eggleston, H.S., Buendia, L., Miwa, K., Ngara, T., Tanabe, K., Eds.; IGES: Kanagawa, Japan, 2006; Volume 5. [Google Scholar]

- Lizik, W.; Im, J.; Semrau, J.D.; Barcelona, M.J. A Field Trial of Nutrient Stimulation of Methanotrophs to Reduce Greenhouse Gas Emissions from Landfill Cover Soils. J Air Waste Manag Assoc. 2013, 63, 300–309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Spokas, K.A.; Bogner, J.; Corcoran, M. Modeling Landfill CH4 Emissions: CALMIM International Field Validation, using CALMIM to Simulate Management Strategies, Current and Future Climate Scenarios. Elem Sci Anthr. 2021, 9, 1–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohsen, R.A.; Abbassi, B.; Zytner, R. Investigation of Fugitive Methane and Gas Collection Efficiency in Halton Landfill in Ontario, Canada. Environ Monit Assess. 2020, 192, 326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scheutz, C.; Kjeldsen, P. Guidelines for Landfill Gas Emission Monitoring Using the Tracer Gas Dispersion Method. Waste Manag. 2019, 85, 351–360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- US EPA. Landfill Gas Energy Cost Model; Landfill Methane Outreach Program (LMOP), U.S. Environmental Protection Agency: Washington, DC, USA, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Environment Agency. Guidance on Landfill Gas Flaring Version 2.1; Environment Agency: Bristol, UK, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Barlaz, M.A.; Chanton, J.P.; Green, R.B. Controls on Landfill Gas Collection Efficiency: Instantaneous and lifetime performance. J Air Waste Manag Assoc. 2009, 59, 1399–1404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, A.; Sharma, M.P. GHG Emission and Carbon Sequestration Potential from MSW of Indian Metro Cities. Urban Clim. 2014, 8, 30–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barlaz, M.A.; Eleazer, W.E.; Odle, W.S., III; Qian, X.; Wang, Y-S. Biodegradative Analysis of Municipal Solid Waste in Laboratory-Scale Landfills; US EPA: Springfield, USA, 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Friedrich, E.; Trois, C. GHG Emission Factors Developed for the Collection, Transport and Landfilling of Municipal Waste in South African Municipalities. Waste Manag. 2013, 33, 1013–1026. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manfredi, S.; Tonini, D.; Christensen, T.H.; Scharff, H. Landfilling of Waste: Accounting of Greenhouse Gases and Global Warming Contributions. Waste Manag Res. 2009, 27, 825–836. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dek, V.P.; Nguyen, V.Q.; Tran, D.K.; Tran, D.X. Challenges and Priorities of Municipal Solid Waste Management in Cambodia. Int J Environ Res Public Heal. 2022, 19, 8458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seng, B.; Fujiwara, T.; Seng, B. Suitability Assessment for Handling Methods of Municipal Solid Waste. Glob J Environ Sci Manag. 2018, 4, 113–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seng, B.; Hirayama, K.; Katayama-Hirayama, K.; Ochiai, S.; Kaneko, H. Scenario Analysis of the Benefit of Municipal Organic-Waste Composting Over Landfill, Cambodia. J Environ Manage. 2013, 114, 216–224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Babilotte, A.; Lagier, T.; Fiani, E. Fugitive Methane Emissions from Landfills: Field Comparison of Five Methods on a French Landfill. J Environ Eng. 2010, 136, 777–784. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghosh, P.; Shah, G.; Chandra, R.; Sahota, S.; Kumar, H.; Vijay, V.K.; et al. Assessment of Methane Emissions and Energy Recovery Potential from the Municipal Solid Waste Landfills of Delhi, India. Bioresour Technol. 2019, 272, 611–615. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amini, H.R.; Reinhart, D.R.; Mackie, K.R. Determination of First-Order Landfill Gas Modeling Parameters and Uncertainties. Waste Manag. 2012, 32, 305–316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Majdinasab, A.; Zhang, Z.; Yuan, Q. Modelling of Landfill Gas Generation: A Review. Rev Environ Sci Biotechnol. 2017, 16, 361–380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alexander, A.; Burklin, C.; Singleton, A. Landfill Gas Emissions Model (LandGEM) Version 3.02 User’s Guide; US EPA: Washington, DC 20460, USA, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- National Institute of Statistics. General Population Census of the Kingdom of Cambodia 2019. 2020. (accessed on 20 September 2021).

- Xaypanya, P.; Takemura, J.; Chiemchaisri, C. , Seingheng, H.; Tanchuling, M.A.N. Characterization of Landfill Leachates and Sediments in Major Cities of Indochina Peninsular Countries—Heavy Metal Partitioning in Municipal Solid Waste Leachate. Environments. 2018, 5, 65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cudjoe, D.; Han, M.S.; Chen, W. Power generation from municipal solid waste landfilled in the Beijing-Tianjin-Hebei region. Energy. 2021, 217, 119393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ayodele, T.R.; Ogunjuyigbe, A.S.O.; Alao, M.A. Life Cycle Assessment of Waste-to-Energy (Wte) Technologies for Electricity Generation using Municipal Solid Waste in Nigeria. Appl Energy. 2017, 201, 200–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hadidi, L.A.; Omer, M.M. A Financial Feasibility Model of Gasification and Anaerobic Digestion Waste-to-Energy (WTE) Plants in Saudi Arabia. Waste Manag. 2017, 59, 90–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Plant, G.; Kort, E.A.; Brandt, A.R.; Chen, Y.; Fordice, G.; Negron, A.M.G.; et al. Inefficient and Unlit Natural Gas Flares Both Emit Large Quantities of Methane. Science. 2022, 377, 1566–1571. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, N.; Zhang, H.; Shao, L.M.; Lü, F.; He, P.J. Greenhouse Gas Emissions during MSW Landfilling in China: Influence of Waste Characteristics and LFG Treatment Measures. J Environ Manage. 2013, 129, 510–521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- 31. EPE. Protocol for the quantification of greenhouse gas emissions from waste management activities, Version 5.0, Entreprises pour L’Environnement: Paris, France, 2013.

- Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Chante. The Science of Climate Change: Contribution of Working Group I to the Second Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change. 1995.

- Ishigaki, T.; Nakagawa, M.; Nagamori, M.; Yamada, M. Anaerobic Generation and Emission of Nitrous Oxide in Waste Landfills. Environ Earth Sci. 2016, 75, 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Institute for Global Environmental Strategies. List of grid emission factors. https://doi.org/10.57405/iges-1215. (accessed on 10 December 2022).

- Garg, A.; Achari, G.; Joshi, R.C. A Model to Estimate the Methane Generation Rate Constant in Sanitary Landfills using Fuzzy Synthetic Evaluation. Waste Manag Res. 2006, 24, 363–375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wangyao, K.; Yamada, M.; Endo, K.; Ishigaki, T.; Naruoka, T.; Towprayoon, S.; et al. Methane Generation Rate Constant in Tropical Landfill. J Sustain Energy Environ. 2010, 1, 181–184. [Google Scholar]

- Anh, L.H.; Thanh, T.N.T.; Tuyen, N.T.K.; Bang, H.Q.; Son, N.P.; Schneider, P.; et al. Site-Specific Determination of Methane Generation Potential and Estimation of Landfill Gas Emissions from Municipal Solid Waste Landfill: A Case Study in Nam Binh Duong, Vietnam. Biomass Convers Biorefinery. 2021, 12, 3491–3502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abushammala, M.F.M.; Basri, N.E.A.; Kadhum, A.A.H.; Basri, H.; El-Shafie, A.H.; Sharifah, M.S.A. Evaluation of Methane Generation Rate and Potential from Selected Landfills in Malaysia. Int J Environ Sci Technol. 2014, 11, 377–384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Srivastava, A.N.; Chakma, S. Quantification of Landfill Gas Generation and Energy Recovery Estimation from the Municipal Solid Waste Landfill Sites of Delhi, India. Energy Sources, Part A Recover Util Environ Eff. 2020; 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramprasad, C.; Teja, H.C.; Gowtham, V.; Vikas, V. Quantification of Landfill Gas Emissions and Energy Production Potential in Tirupati Municipal Solid Waste Disposal Site by LandGEM Mathematical Model. MethodsX. 2022, 9, 101869. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ishigaki, T.; Hirata, O.; Oda, T.; Wangyao, K.; Chiemchaisri, C.; Towprayoon, S.; et al. Greenhouse Gas Emission from Solid Waste Disposal Sites in Asia. In Integrated Waste Management, Kumar, S., Eds; IntechOpen: London, United Kingdom, 2011; Volume 2, pp. 462–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Christensen, T.H.; Manfredi, S.; Knox, K. Landfilling: Reactor Landfills. In Solid Waste Technology & Management, Christensen, T.H., Eds; John Wiley & Sons: United Kingdom; 2010. [CrossRef]

- Chiemchaisri, C.; Juanga, J.P.; Visvanathan, C. Municipal Solid Waste Management in Thailand and Disposal Emission Inventory. Environ Monit Assess. 2007, 135, 13–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fallahizadeh, S.; Rahmatinia, M.; Mohammadi, Z.; Vaezzadeh, M.; Tajamiri, A.; Soleimani, H. Estimation of Methane Gas by LandGEM Model from Yasuj Municipal Solid Waste Landfill, Iran. MethodsX. 2019, 6, 391–398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gollapalli, M.; Kota, S.H. Methane Emissions from a Landfill in North-East India: Performance of Various Landfill Gas Emission Models. Environ Pollut. 2018, 234, 174–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chakraborty, M.; Sharma, C.; Pandey, J.; Singh, N.; Gupta, P.K. Methane Emission Estimation from Landfills in Delhi: A Comparative Assessment of Different Methodologies. Atmos Environ. 2011, 45, 7135–7142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, A.; Sharma, M.P. Estimation of GHG Emission and Energy Recovery Potential from MSW Landfill Sites. Sustain Energy Technol Assessments. 2014, 5, 50–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nordahl, S.L.; Devkota, J.P.; Amirebrahimi, J.; Smith, S.J.; Breunig, H.M.; Preble, C.V.; et al. Life-Cycle Greenhouse Gas Emissions and Human Health Trade-Offs of Organic Waste Management Strategies. Environ Sci Technol. 2020, 54, 9200–9209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Year | Population a (thousand) |

Waste landfilled (t/year) |

Per capita collection (kg/cap/day) |

Year | Population a (thousand) |

Waste landfilled (t/year) |

Per capita collection (kg/cap/day) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2009 | 1393 | 177,224 b | 0.70 | 2016 | 1947 | 717,435 | 1.01 |

| 2010 | 1461 | 409,336 | 0.77 | 2017 | 2043 | 808,530 | 1.08 |

| 2011 | 1533 | 442,469 | 0.79 | 2018 | 2143 | 965,944 | 1.24 |

| 2012 | 1608 | 492,380 | 0.84 | 2019 | 2282 | 1,015,980 | 1.22 |

| 2013 | 1687 | 532,471 | 0.86 | 2020 | 2394 | 1,035,878 | 1.19 |

| 2014 | 1770 | 617,489 | 0.96 | 2021 | 2511 | 1,012,039 | 1.10 |

| 2015 | 1856 | 681,905 | 1.01 | 2022 | 2634 | 1,288,223 | 1.34 |

| Type of waste disposal site | MCF default values |

|---|---|

| Managed – anaerobic | 1.0 |

| Managed – semi-aerobic | 0.5 |

| Unmanaged – deep (>5 m waste) and/or high-water table | 0.8 |

| Unmanaged – shallow (<5 m waste) | 0.4 |

| Uncategorized landfill | 0.6 |

| Item | Emission factor | Unit | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|

| Diesel fuel | 2.70 | kg CO2-eq/L | This study |

| Electricity grid | 0.586 | kg CO2-eq/kWh | [34] |

| HDPE liner | 1.9 | kg CO2-eq/kg | [14] |

| Gravel | 0.0027 | kg CO2-eq/kg | [30] |

| Water | 0.0002 | kg CO2-eq/L | [30] |

| HCl | 0.8 | kg CO2-eq/kg | [30] |

| NaOH | 1.04 | kg CO2-eq/kg | [30] |

| Location | k (year-1) | L0 (m3/t) | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|

| Phnom Penh, Cambodia | 0.21 | 90 | This study |

| Nam Binh Duong, Vietnam | 0.355 | 81 | [37] |

| Four landfills, Thailand | 0.33 | - | [36] |

| Sanitary landfills, Malaysia | 0.072–0.136 | 151.7 | [38] |

| Delhi, India | 0.05 | 130 | [39] |

| Andhra Pradesh, India | 0.05 | 110 | [40] |

| Salvador, Brazil | 0.21 | 70 | [2] |

| Year | LandGEM (GWh) |

IPCC FOD (GWh) |

Year | LandGEM (GWh) |

IPCC FOD (GWh) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2009 | - | - | 2016 | 50.04 | 60.36 |

| 2010 | 4.10 | 5.78 | 2017 | 56.99 | 68.00 |

| 2011 | 12.77 | 17.49 | 2018 | 64.71 | 76.84 |

| 2012 | 20.55 | 27.00 | 2019 | 74.58 | 88.73 |

| 2013 | 27.97 | 35.59 | 2022 | 83.71 | 99.35 |

| 2014 | 34.90 | 43.27 | 2021 | 91.54 | 108.11 |

| 2015 | 42.45 | 51.82 | 2022 | 97.31 | 114.18 |

| Activity | S1 | S2 | S3 | S4 | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| LandGEM | IPCC | LandGEM | IPCC | LandGEM | IPCC | LandGEM | IPCC | |

| Fugitive CH4 | 820.09 | 998.86 | 820.09 | 998.86 | 405.53 | 493.94 | 190.67 | 291.42 |

| Landfill operation | 1.16 | 1.16 | 10.16 | 11.32 | 11.92 | 13.08 | 14.27 | 15.43 |

| Leachate treatment | - | - | 14.38 | 14.38 | 14.38 | 14.38 | 14.38 | 14.38 |

| N2O emission | 17.60 | 21.43 | 17.60 | 21.43 | 8.80 | 10.72 | 4.40 | 5.36 |

| Electricity offset | - | - | - | - | - | - | ˗51.89 | ˗63.20 |

| Carbon sequestered | ˗104.51 | ˗104.51 | ˗104.51 | ˗104.51 | ˗104.51 | ˗104.51 | ˗104.51 | ˗104.51 |

| Total | 734.33 | 916.94 | 757.72 | 941.49 | 336.12 | 427.61 | 115.91 | 157.85 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).