1. Introduction

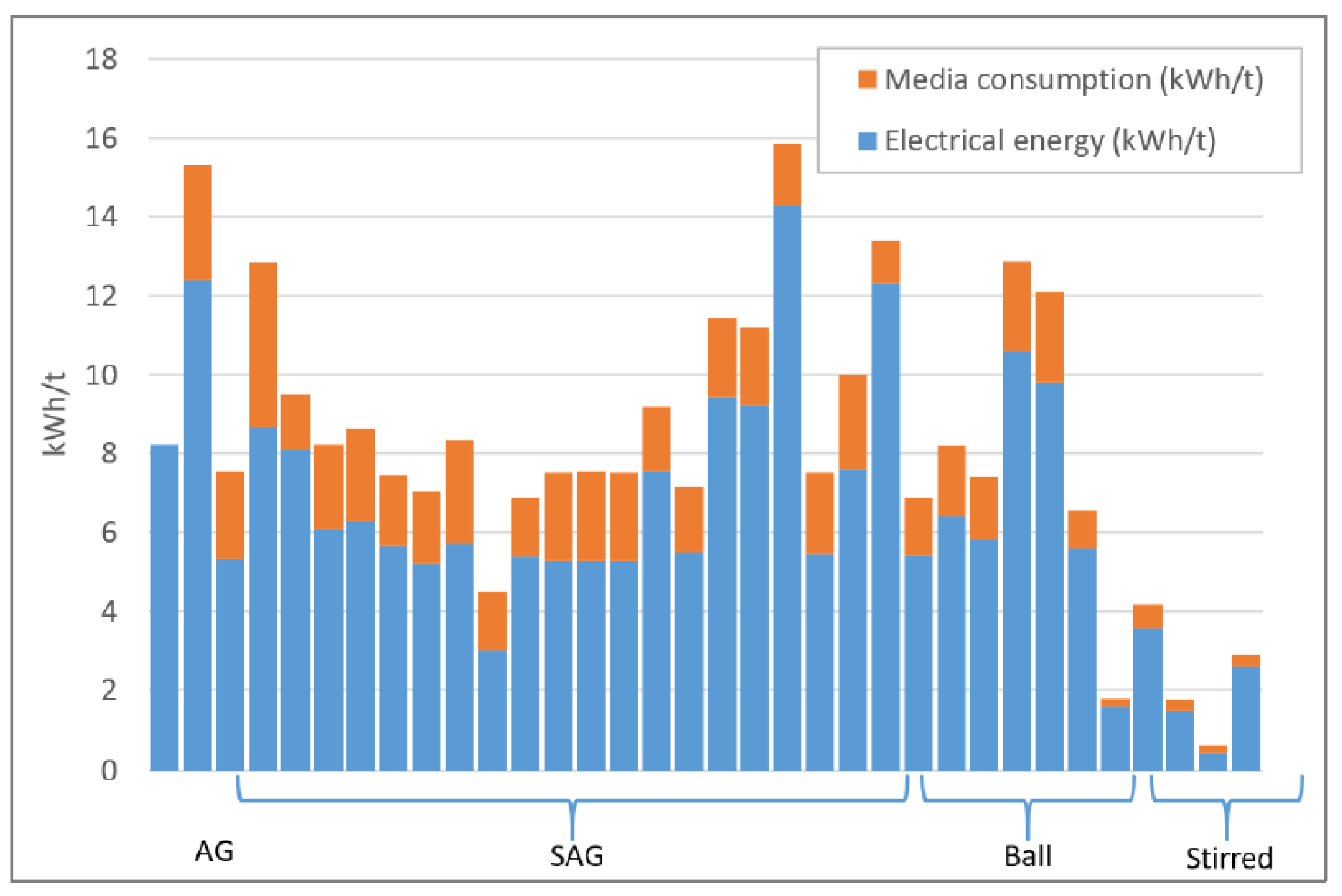

According to data analysis by Napier-Munn [

1] the comminution process consumes 1.8% of the world’s generated electricity, excluding energy used by ancillary equipment and indirect energy consumption by liners and grinding media. The ancillary equipment includes conveyors and slurry pumps, which are used to transfer material. The indirect energy expenditure is the amount used in consumables that supports the comminution process such as steel balls and liners, whereas the direct energy is energy used by comminution equipment such as mills and crushers. According to Ballantyne [

2] indirect energy has been classified as embodied energy and, from the study conducted, it was shown to be of significance when considering power usage of the comminution process, as depicted in

Figure 1. The embodied energy considered took into account the media's life cycle assessment, which included mining, smelting, casting and shipping costs. In another study conducted by Fatahi et al. [

3] the comminution process was shown to consume about 4% of the world’s electricity. Concentration plants, which include grinding after mining the ore, consumed 48.6% of global energy in the copper mining industry and it could reach 64.2% by 2025 [

4].

Recently, it was realised that high-grade ores are depleting fast and are almost extinct. Therefore, low-grade ores are currently being mined, which has forced many mines to upgrade the size of their mills, to increase the mill throughput. Larger mills have a low energy efficiency, hence costly to operate [

5]. Ball mills operate by movement and interaction between the grinding media and the ore to be broken [

6]. According to Hassanzadeh [

7] about 37% of the costs are used for grinding media only,13% for liners and about 50% is used for energy.

Grinding is the final stage of comminution, which reduces particle size to micron size level. The size reduction is achieved by attrition, abrasion, and impact between the ore itself and between the ore particles and grinding media [

8]. According to Swart et al. [

9], ball mills are mostly used because of their very high size reduction ratio, although they have a very low energy efficiency of about 20%. According to Conger et al. [

10], many factors affecting ball mill efficiency include mill design, liner design, mill speed, charge ratio, and grinding media properties. The authors also indicated that circuit efficiency is determined by how well the power applied to coarse material grinds the coarse material.

This review paper is mainly going to focus on the effect of grinding media on ball mill performance. Grinding media directly affects energy consumption, product size and consequently the grinding costs [

11]. Proper selection of the grinding media reduces energy and material consumption in a ball mill. Different performances are achieved when different sizes and shapes of grinding media are used [

12]. Good grinding media should have high wear and impact resistance to last longer, thus increasing their life of service and that of mill liners hence reducing the cost of comminution.

2. Grinding Media in Ball Mills

Various grinding media are used for milling in ball mills to achieve sufficient particle size reduction and mineral liberation for downstream separation processes. Particle breakage is attained by the collisions between the ore and the grinding media. During the interaction of ore and grinding media, a complex physical and chemical system is formed, causing changes in particle size, pulp chemistry, surface chemistry, and crystal structure of minerals. [

13]. The movement of grinding media which results in collisions is affected by mill design, mill speed, mill filling and grinding media properties[

14]. The collision impact cause particle breakage due to the kinetic and potential energy of the grinding media. For a successful collision to happen, the grinding media should attain a minimum collision energy first. Research done by Wang et al. [

15] in which the author was investigating the effect of ground material (limestone) on material flow inside the mill, showed that the collision energy of grinding media increased with mill speed from 22 to 45rpm giving more undersized product of 15.2mm, 11.2mm and 8.6mm and suddenly dropped when the mill was run at 67rpm. This therefore suggests that the ball mill should be run within its optimum range in this case, which is between 22-45 rpm. Another factor investigated in the same study which affects the collision rate between the grinding media and the ore was the grinding media loading. The collision rate increased when the grinding media loading increased from 10% to 40% whilst the loading of the ore was constant. The grinding performance greatly increased with increasing loading up to 40%. However, beyond 50% loading, the grinding performance dropped slightly.

The most commonly used grinding media is made from various types of steels, iron and its alloys. Poor and unreasonable grinding media give rise to inferior granule product size distribution in which the valuable mineral is unliberated or an overground product which deteriorates the concentration processes at the same time consuming unnecessary excess energy [

16]. In ball mill operations, it is always helpful to optimise the grinding media system to minimize the costs of the operation. In a research done by Yu et al. [

16] to optimize grinding media system, there was a 30% increase in grinding efficiency and also a reduction in energy consumption. Laboratory tests were done to optimize the grinding media system by ascertaining optimal media size, media proportion and material ball ratio.

According to Kelsall et al. [

17] changes in media (quantity, density, size, shape) change the product distribution in continuous ball mills. In an experiment conducted using a wet laboratory continuous ball mill filled with pebbles, cylinders and balls of equivalent volume and a 95% calcite feed combined with a 5% quartz, ball load, density and shape were varied. It was shown that decreasing the ball load by 0.5 by weight also decreased the residence time by 40%. Breakage rates were also affected by the frequency of the impacts. Reduction in the specific gravity of the grinding media resulted in a disproportionate decrease in breakage rate for the coarse sizes compared with the fine sizes. As the specific gravity of the media approached that of the pulp within the mill, zero breakage rate was observed. However, media density had no effect on the breakage function, but the change in media shape caused a distinct change in the breakage function.

2.1. Types of Grinding Media

Grinding media are the main components of the grinding process involving a ball mill. Research has been done to select the most suitable materials to manufacture improved grinding media [

18] [

19], [

20], [

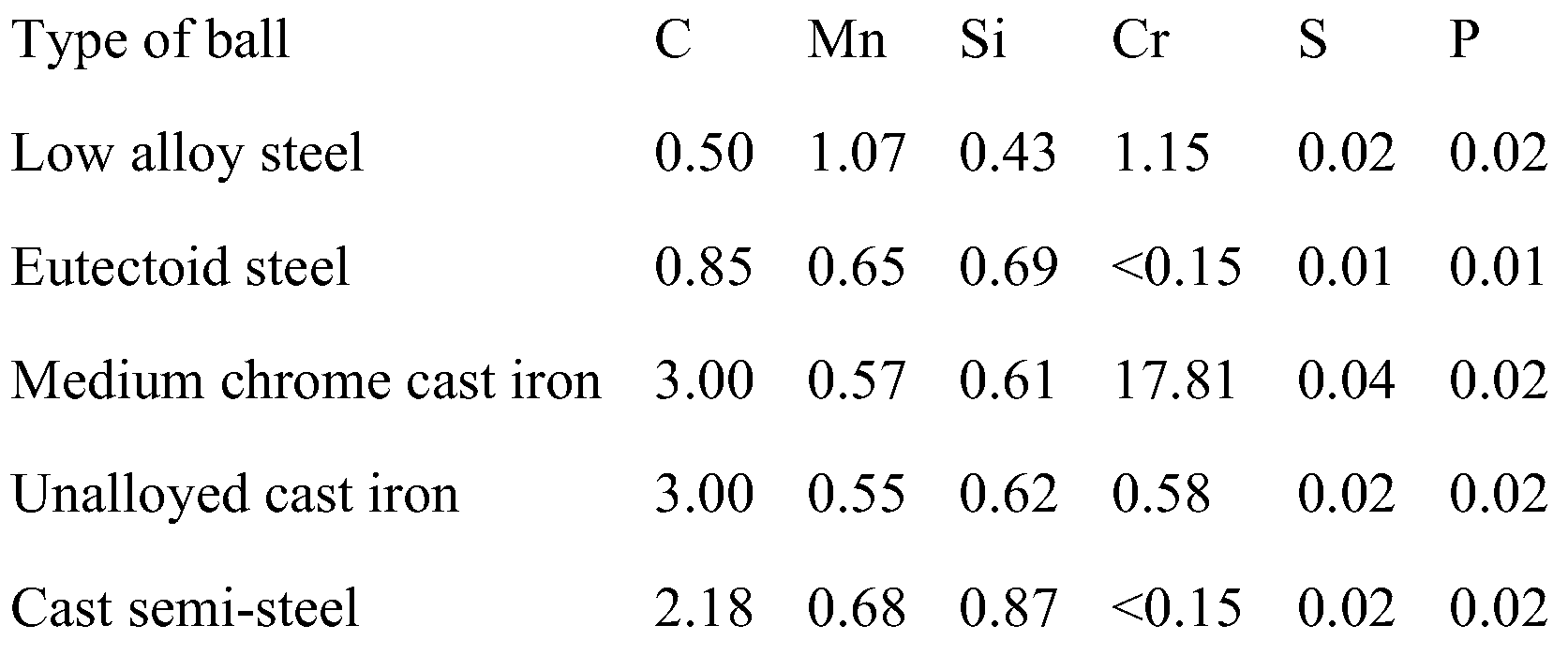

21]. Good grinding media should have high hardness, fracture toughness, wear resistance and corrosion resistance, but at the same time, it should have adequate ductility to minimize sudden ruptures and chipping. Grinding media can be classified according to the materials used to manufacture them (cast iron, low alloy steels, high alloy steels) or according to the process used to make them (forged or cast, rolled). Cast irons are iron-containing alloys containing carbon contents generally between 2 and 4 wt. % whereas steels contain carbon content less than 2 wt. %.

Grinding media gets consumed during grinding and poses a danger of contamination in subsequent processes. The specific consumption of grinding media depends on the microstructure of the media, the mineralogical composition and the hardness of the ore [

22]. The chemical composition and process conditions during the manufacturing of grinding media determine its microstructure, which directly affects the grinding media quality [

23]. Spherical balls are better for crushing large particles by impact due to their point of contact between the grinding media and the ore. Spherical balls are manufactured using cast iron, low-alloy and high-alloy carbon steels. Alloy steels are made by the addition of alloying elements like chromium, aluminium, manganese, and silica. The typical composition of grinding media is shown in

Table 1.

2.1.1. Cast Iron

Cast iron can be grey cast iron or white cast iron, but white cast irons are commonly used in abrasive wear applications involved in the comminution process. Cast iron grinding media is one of the ancient media first used in mineral processing [

25]. However, it presented several problems, which included spalling and premature breakage. These cast irons contained iron carbides. In large-diameter ball mills, they had an average resistance to abrasion and insufficient impact toughness. To date, the rest of the world phased out the use of unalloyed cast iron, but some countries still use it because of its low cost, but in the long run, they are not cost-effective. Around the 1960s, improved cast iron balls manufactured were made of ductile cast iron with medium manganese (5-6% Mn) which were applied in the mining industry. However, these balls had serious fatigue spalling and breakage in service caused by retained austenite and eutectic carbides in its matrix but were later improved by investigating martensitic ductile cast iron, bainitic ductile cast iron, austempered ductile cast iron, and as-cast pearlitic ductile cast iron. The resulting balls had an appropriate cooperation of impact fatigue resistance and abrasive wear resistance. They also had lower breakage, lower fatigue spalling and lower production costs [

26].

These problems presented by unalloyed cast irons and ductile cast irons were solved by the development of high chromium cast irons, which had very low wear rates. According to Rajagopal and Iwasaki [

23], their wear rate was ten times lower than that of cast or forged steel when used in dry grinding applications. Metallurgical developments and manufacturing process refinement in heat treatment and machining techniques resulted in broader use of high chromium cast irons. From a study done by Chenje et al. [

27] to compare 5 types of grinding media balls (eutectoid steel, low alloy steel, medium chromium cast iron, cast semi-steel and unalloyed white cast iron), heat-treated medium chromium (HTMC) cast iron balls showed superior qualities in terms of microstructure, and wear resistance despite its high cost per ton. Due to their microstructure, the cast irons had relatively high carbon content, which gave them high hardness compared to other ball types. HTMC balls had higher hardness than unalloyed cast iron (UCI). Therefore, from this research, it was apparent that adding an alloying element to purely cast-iron grinding media enhances their performance during grinding.

In another research done by Rahman et al. [

28] in Bangladesh to manufacture grinding balls locally, high chromium cast iron (HCCI) balls were found to have excellent wear resistance, which can be used widely in mineral processing, coal and cement. HCCI is ferrous based alloyed with 11-35 wt.% chromium and 1.8-7.5 wt.% carbon. The excellent wear resistance of HCCI balls is from the high-volume fraction of hard chromium carbides, which form in-situ on cooling from the melt of a casting, in a softer ductile matrix. After casting, the HCCI balls had high hardness, impact toughness and wear resistance. In a recent overview on cast irons done by Ngqase and Pan [

29], it was revealed that the white cast irons have been developed over the years to have an excellent combination of good mechanical strength and high wear resistance. The optimal addition of chromium helps to prevent the formation of graphite and stabilises the carbide and elements such Mo, Mn, Cu or Ni increasing hardenability by suppressing the formation of pearlite during cooling to room temperature.

However, in other operations in which the ore is soft and has a Mohr’s hardness of less than 6, cast iron grinding media can have a higher cost-benefit analysis as compared to other media. In a study done by Gates et al. [

30] to investigate the effect of abrasive minerals on alloy performance in a ball mill, four abrasives which were slag, ilmenite, staurolite quartz and garnet were used in four different alloy classes. White cast iron had the least mass loss per unit mass of ore as compared to pearlitic and martensitic steels.

2.1.2. Low alloy Steel

Most commercial grinding media today is produced from martensitic low-alloy steels, which may be forged or cast. They can adapt to most milling conditions and have a favourable cost-to-wear ratio. Low-alloy high-carbon steels are used because they are the strongest, hardest and least ductile, therefore offering high resistance to abrasive wear compared to other steels when used in the tempered form [

31], [

32]. Most floatation plants use forged high carbon low alloy grinding media prior to flotation due to their low cost as compared to other media, but they present problems in the floatation circuit since they form a galvanic cell consisting of grinding media-sulfide mineral system. Usually, the forged steel balls act as the anode whilst the sulfide mineral will be the cathode. The iron ball form hydrophilic hydroxides which coat sulfide minerals, thereby rendering them hydrophilic as well and also hindering collector adsorption [

33].

Other low alloy-high carbon steels contain titanium between 0.04-2 wt.%. In a research done to investigate the impact of titanium on the wear properties of the grinding media, three types of balls were used with varying titanium content (0.04wt%, 0.1wt%, 2wt%). The grinding media with 0.04wt% had superior mechanical properties, with a hardness of 745 HV and an impact toughness of 97J/cm3. From the research, it was concluded that excessive titanium degrades the mechanical properties of grinding media due to the precipitation of large particles in the steel matrix [

34].

2.1.3. High Alloy Steel Grinding Media

High chrome grinding media is a very economical media based on its wear performance. In a study done by Kinal et al. [

33] using a laboratory ball mill which found Kagara’s Mount Garnet operation changing from low alloy forged steel to high chrome media (30% chrome), the recoveries and the grade of copper were expected to improve from the laboratory tests done. The wear rate of the high chrome media was 3 times less than that of forged steel. This was due to the rapid formation of a chrome oxide layer, which suddenly halts the corrosion process. Additionally, there was an improvement in the pulp chemistry and a reduction of reagent dosage rates by 25%. The presence of oxygen freed in the system when the corrosion stops enhances collector absorption and mineral floatability. In another study done by Greet et al. [

35] to investigate the effect of grinding media on pulp chemistry and floatation performance on galena, high chrome grinding media produced high lead recovery and galena floatation rate in the fine particle size range(-10m) as compared to the forged steel media. Results obtained in this study agreed with what had been done by Cullinan et al. [

36] where galena was ground using forged high carbon low alloy steel balls, high chrome white iron balls and ceramic balls. The recovery of galena using high chrome balls was higher than using forged low alloy steel balls.

However, changes in pH had detrimental effects on the wear rates observed from a study of high chromium alloy grinding media in a grinding mill with about 26-30 wt.% chrome by Chen et al. [

37] using a phosphate ore in a modified ball laboratory ball mill whose electrochemical potential could be controlled. Of all the factors which were investigated, including the grinding time, rotation speed, and feed percentage solids, the highest wear rate of about 224 mills penetration per year (MPY) was observed at an acidic pH of 3.1. The mill critical was 90rpm. The wear rate decreased when the mill speed changed from 35rpm to 55rpm. This was because of less wear since the motion was still in the cascading phase, hence less interaction between the grinding media. The wear rate started to increase from 60rpm to 80rpm because the media was in the impact speed range which led to an increase in grinding media interaction. The wear rate started to drop again until it reached 90rpm because it had reached its centrifugal speed. At 75% critical speed, the optimum speed was determined to be 70rpm. The grinding media wear rate also showed a linear relationship with an increase in grinding time. With increasing feed solids percentage, the wear rate decreased. The wear rate was about 289MPY at a feed solids percentage of 44% and 103MPY at a feed solids percentage of 84%. This is because a higher feed solids percentage increased the pulp viscosity, thereby coating the balls, and providing a cushion effect which decreases the abrasion rate. At lower feed solids percentage, more oxygen was dissolved in the pulp, which gives rise to corrosion of metal since the galvanic cell is set up.

From these various studies, it can be denoted that high alloy grinding media has advantageous properties, which may result in a favourable cost-benefit analysis. However, to fully reap the advantages of using high alloy grinding media, the operational parameters such as Ph discussed should be optimized as well.

2.2. Properties of Grinding Media

2.2.1. Grinding Media Density

In order to increase the efficiency of the grinding mill, Stoimenov et al. [

38] suggested the increment of grinding media density. Kelsall et al. [

17] investigated the influence of grinding media density on the grinding behaviour of a small amount of quartz in calcite in a continuous ball mill using different grinding media of different densities. The author found that the breakage rate constantly decreased with decreasing grinding media density. The decrease was more significant when grinding coarse particles as compared to fine particles. In a study by Yildinm et al. [

39] using different grinding media of different shapes and densities, mill power draw was linearly proportional to media density. Harriss et al. [

40] also included grinding media density as one of the variables that affect power consumption.

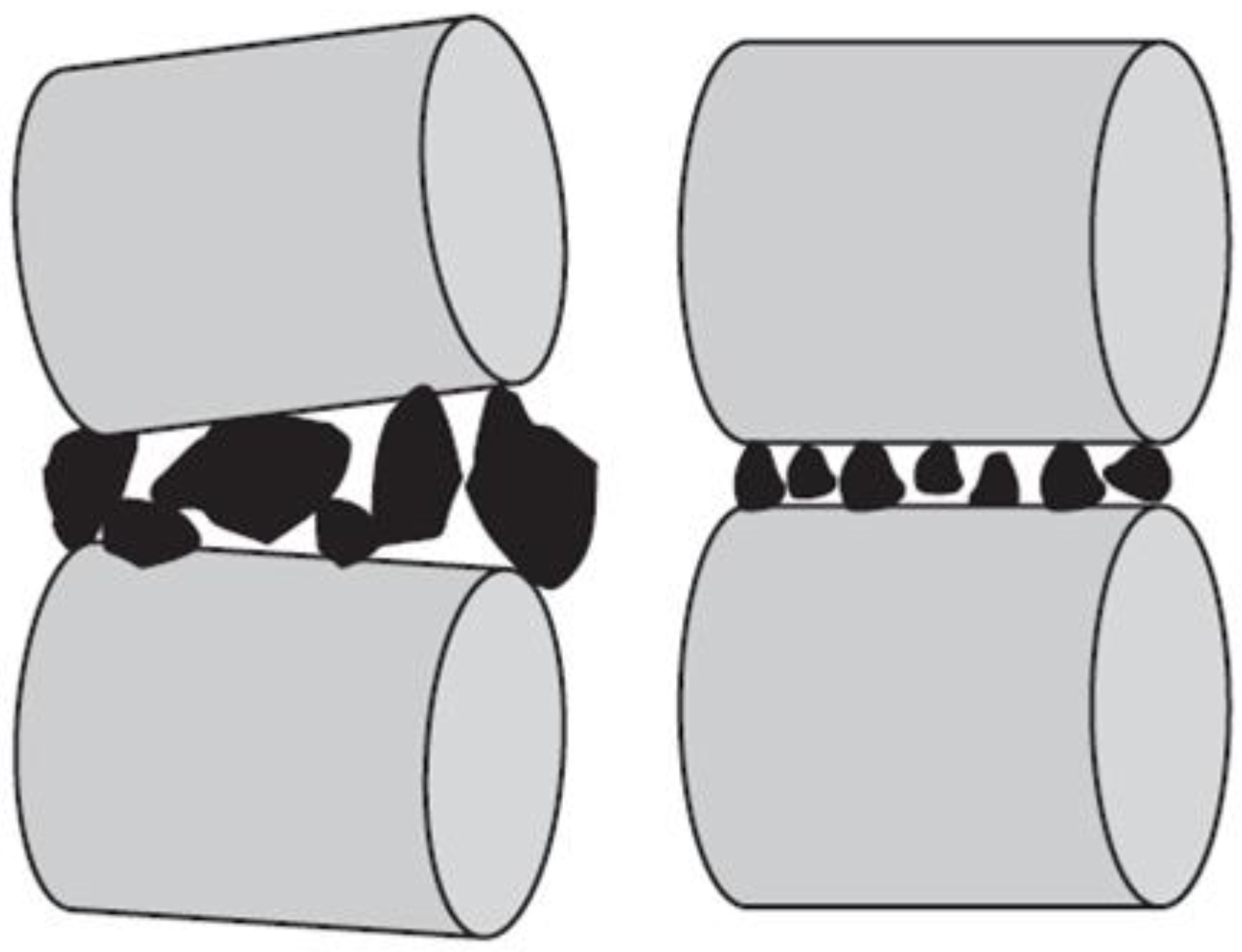

2.2.2. Grinding Media Hardness

Abrasion wear is due to friction between the surfaces where there is sliding contact, which causes mechanical disintegration to the surface of the grinding media. Impact wear is a result of shock between surfaces from multiple angles, causing disintegration. As the hardness of the grinding media increases, the wear resistance increases as well. This is because hard grinding media resists penetration of particles on its surface layer. In the ball mill, it has been observed that wear is due to a combination of one or more mechanisms but there will be a dominant mechanism depending on the process parameters which are fill rate, mill speed, ball diameter, ball shape and grinding time [

41].

In the ball mill, friction is formed due to the difference between surfaces of adjacent grinding balls in the abrasion zone, whilst impact is due to rock-ball impact and ball-ball impact in the impact zone, as shown in Figure 8. In a series of experiments done by Aissat et al. [

42], smaller diameter balls of 50mm had a higher wear rate than larger diameter balls of 70mm. This was due to the higher percentage of chromium in the 70mm balls as compared to the 50mm balls. Therefore, this suggests that when a seasoned charge of grinding media is used, the wear rate of each specific ball diameter should be known. This affects the rate at which different sizes of makeup balls are added to the mill. Hardness is also affected by the process used to manufacture the grinding media. The heat treatment, temperature and quenching method determine the hardness of the grinding media. In one study, oil-quenched alloy-steel balls heat-treated at lower temperatures showed greater hardness than compressed air-quenched alloy-steel balls, which were heat treated at a higher temperature. This is due to the formation of a martensite matrix in oil-cooled media, which is more wear resistant than the ferrite matrix in compressed air-cooled media [

43].

2.2.3. Grinding Media Size

Ball sizes which are used in grinding should be large enough to break the largest and hardest ore particles. Optimal ball sizes depend on the feed/product size ratio, mill dimensions, and breakage kinetics parameters. Usually, larger balls grind coarser ore particles efficiently and smaller balls grind fine particles more efficiently [

44]. Larger balls break particles by impact, whilst smaller balls break by abrasion. Sometimes the smaller balls do not have sufficient impact energy to break an ore particle therefore, both media sizes are vital. An optimal ball size range should provide sufficient energy to break coarse ore particles, but at the same time should not produce unnecessary ultrafine particles.

From experiments done by Lameck [

45], larger balls were effective for large feed sizes due to their impact, though they had a reduced surface area whilst small balls were effective on small feed sizes because of their abrasion and higher surface area. In another experiment, to determine the effect of ball size on mill efficiency, Kabezya and Motjotji [

46] observed that 30mm diameter balls were better than 10 and 20mm diameter balls in grinding a quartzite ore of feed size -8 to +5.6mm. However, there was an increase in efficiency when the feed size -2mm to +1.4mm was ground by 20mm diameter balls. Therefore, it was concluded that the effect of ball size on mill performance depends also on the feed size.

Another study conducted by Petrakis et al. [

47] on grinding ferronickel slag using different-sized balls (12.7mm, 25.4mm, 40mm) showed that for each ball size, the breakage rates obey non-first-order kinetics and coarser particles are ground more efficiently as the grinding time increases. This may be due to the energy transfer mechanisms in ball mill machines whereby coarser particles are preferentially ground or be cushioned by fines from the energy dissipation through inter-particle friction and heterogeneities produced in the feed particles [

48]. A seasoned ball charge of (12.7mm, 25.4mm, and 40mm) balls and the 25.4mm balls alone resulted in a decrease in energy consumption by 24% and 31% respectively compared to the smaller-sized balls (12.7mm). The mill was operated at 70% of its critical speed with a ball filling of 20% (J). Material filling volume was 4% (fc) and interstitial space was kept at 50%. Another factor to consider when selecting the optimum media is the mill speed. At each mill speed, there is an optimal ball size. Shin et al. [

49] found that the diameter of optimal ball size decreases as mill speed increases. Small balls have low kinetic energy but a high number of contact points, whilst big balls have high kinetic energy but a low number of contact points, which results in the intermediate size being the optimal ball size.

Another study by Hassanzadeh [

7] found that using mono-sized balls reduces abrasion grinding and this results in a coarser product. In the experiment, mono-sized balls of 80mm were compared with a binary ball size containing 60% of 60mm and 40% of 80mm. The binary charge produced a product with more fines of less than 75µm by 4%. This is because, at a fixed volume charging, the binary ball size has more collisions, which increases the grinding rate. Adding smaller balls inside the mill also improved cascading motion, therefore producing a finer product, with an improved P80 as shown in

Figure 2 [

7]. However, as ball size increases, the particle-ball collision frequency decreases hence, optimal ball sizes should be used. Another factor to take into consideration is the feed size because the coarser the feed, the larger the fraction of large balls required [

50]. The mode of breakage, be it impact, chipping or attrition, also depends on feed size and the grinding balls. The size of grinding media and feed particles determines the product size. Large balls have shown to have less ability to break smaller particles by attrition, whilst smaller balls were better at it.

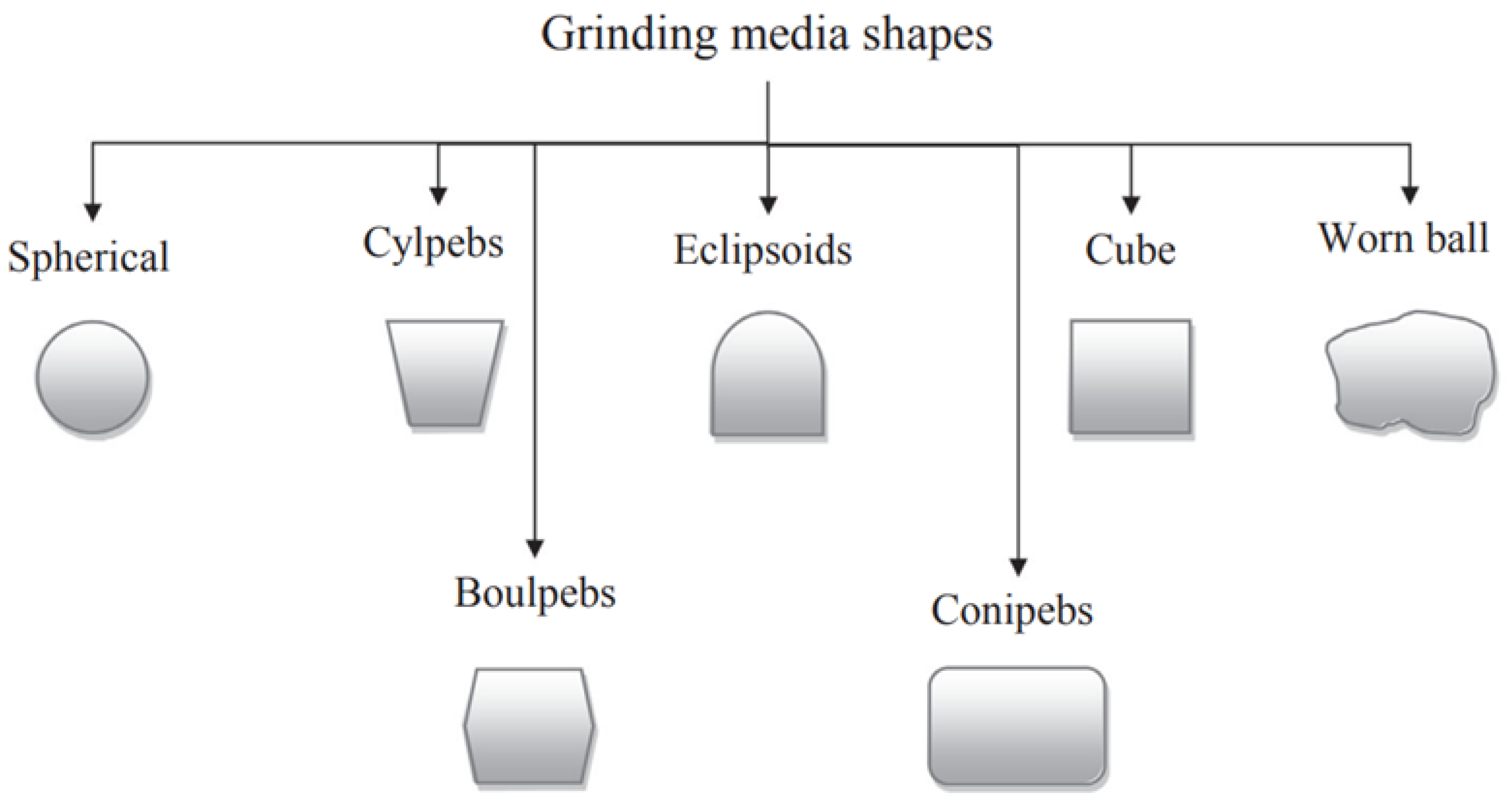

2.2.4. Grinding Media Shape

The difference in media shape results in different surface area of the media, bulk density, and contact mechanisms during grinding. Different grinding media shapes have different toe and shoulder positions in the mill, resulting in different power draws and load behaviour. Toe and shoulder positions are the angular positions where the liner comes into contact with the charge and when the charge departs from the liners, respectively. However, for all grinding media, the power draw increases with an increase in mill speed [

51]. Some of the shapes of the grinding media that have been tested are shown in

Figure 3.

Ball mills use various grinding media to grind the ore inside them into finer products. Spherical balls are mostly used for ball mill processes, and they change their shape with time due to the wearing away of the outer layer caused by abrasion and impact. According to experiments done by Dökme et al. [

11] using worn balls and spherical balls, the spherical balls produced 27% finer particles and consumed 5% less power which suggests that worn balls should be constantly removed from the mill since they affect the breakage kinetics of ore particles. Worn balls reduce grinding efficiency by affecting product size because they reduce the grinding surface area compared with spherical balls. However, there is a need to investigate the relationship between worn balls and mill speed, liner profiles, or filling ratios.

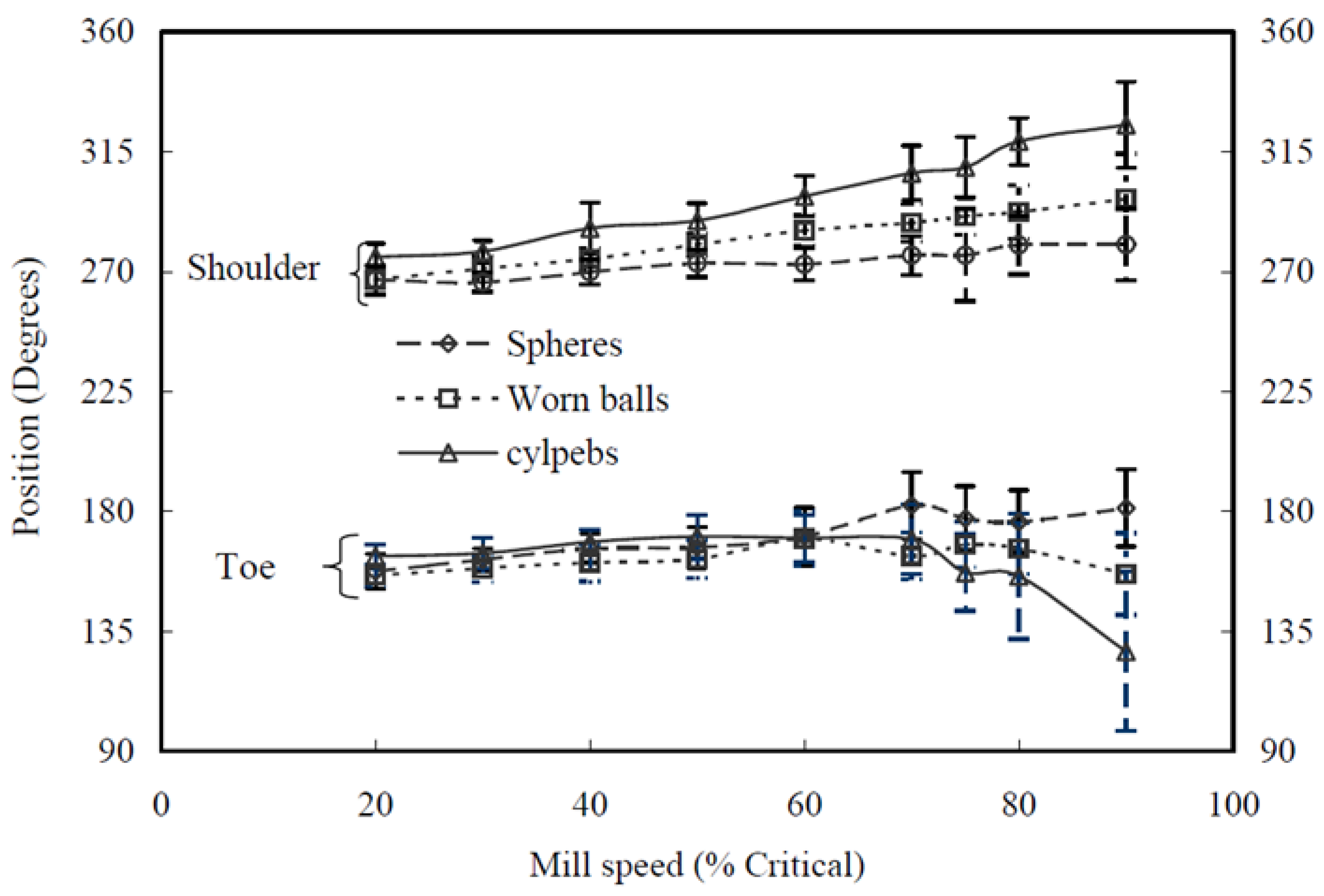

Findings from Lameck [

45] showed that cylpebs have the highest shoulder position and lowest toe position than spherical and worn balls at a critical speed of more than 60% as shown in

Figure 4. The higher shoulder positions of cylpebs than other media is due to cataracting and premature centrifuging for cylpebs as compared to the other media shapes. The lower toe positions for the cylpebs were due to close packing and locking of the media such that their cascading speed is less than the mill speed. Shoulder positions of spherical and worn balls increased with charge filling, but the toe positions for all media shapes were similar for speeds below 70% of the critical speed. Cylpebs showed a very small variation of shoulder positions with a change in mill speed. Power draw increased with mill speed for all media shapes, which showed that there is no relationship between media shape and power draw. During the experiments, the author also observed that the breakage kinetics of ore depend on ball size and shape.

In a review done by Shahbazi et al. [

51], cylpebs produced a less oversized product than steel balls with the same mass and similar size distribution. The cylpebs had 14.5% surface area and 9% bulk density, which was more compared to spherical media. From various experiments conducted by Shahbazi et al. [

51], it has been observed that spherical balls have the lowest shoulder position as shown in

Table 2. It was also found that shoulder positions do not solely rely on media shape but also on mill filling as well. The shoulder position increased while the toe position decreased as the mill filling increased. Cylpebs were found to have the highest shoulder position and the lowest power draw and thus a more cataracting behaviour than worn and spherical grinding media. Aldrich [

53] found out that the specific breakage of cement clinkers was higher with cylpebs grinding media than with steel balls in a ball mill.

In another study done by Kiangi et al. [

54], spherical balls and a multifaceted polyhedron with grinding media filling (J) =16% and 20% respectively, had a negligible difference in their power draw. This was due to inefficient interlocking of the multi-faceted polyhedron because of the charge strength compromise and therefore behaved like the spherical media. As J increased to 25% the power used by the multi-faceted polyhedron media decreased slightly at mill speeds greater than 75% of the critical speed. This was due to an increase in cataracting of balls within the load. The study showed that grinding media shape has a small impact on power draw when the mill filling level is low.

Another very essential phenomenon during the grinding process that is affected by the media shape is the grinding kinetics. In one comparative study between spherical and non-spherical media shapes, cylpebs proved to have higher grinding kinetics than spherical grinding media [

50]. In another study done by Simba & Moys, [

56], it was shown that mixing different shapes of grinding media enhances the grinding kinetics. Kolev et al. [

52] also confirm that a mixture of grinding media with different shapes increases the volume of the grinding zone, which will improve milling kinetics. In the comparative study done between spherical grinding media and Realeaux-tetrahedron shaped (RELO) grinding media (RGM) at different circulating loads rotating at the same mill speed, the authors concluded that RGM had a 14% higher undersize product than spherical balls which gives way to improving energy efficiency.

Grinding media shape affects the mass transport of ore inside the ball mill during comminution. A comparison between the ball mill and rod mill showed that particles in a ball mill have a shorter residence time than in a rod mill [

58]. This is because balls offer less resistance to the flow of material compared to rods. Therefore, even as far back as forty years ago, some experiments with different media shapes proved that media shape affects the residence time of the ore [

17].

Different grinding media shapes produce particles with different surface properties and roughness, which affects flotability and other concentration processes, so changing media may also affect downstream processes [

59]. In one study by Luo et al. [

60] using ball and rod media, the flotation data indicated that the rod-milled spodumene has a higher flotability than ball-milled ones under anionic/cationic collector system. This was because the rod-milled spodumene is too elongated and flat, which are parameters closely related to bubble adhesion.

In another research done by Kfiiger et al. [

61] using concave-convex balls (modified spheres) and spherical balls to grind in batch tests, replacing some of the spherical grinding media with concave-convex balls gave a 10% increase in the fineness of the ground product. However, increasing the number of concave-convex balls replacing the spherical media decreased the grinding efficiency due to the irregular movement of the concave-convex grinding media. Concave grinding media have larger specific areas than spheres, which increases the grinding efficiency.

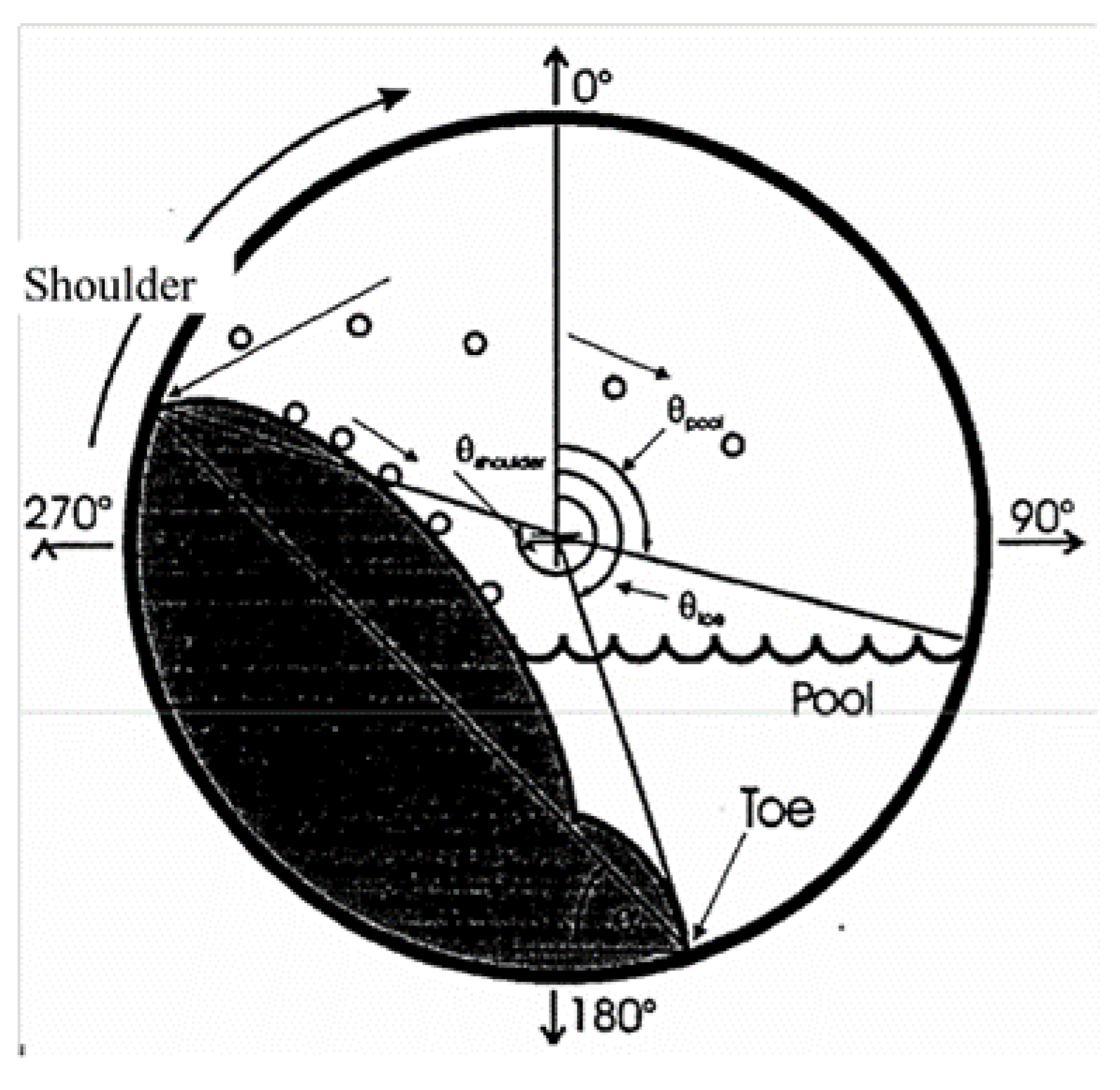

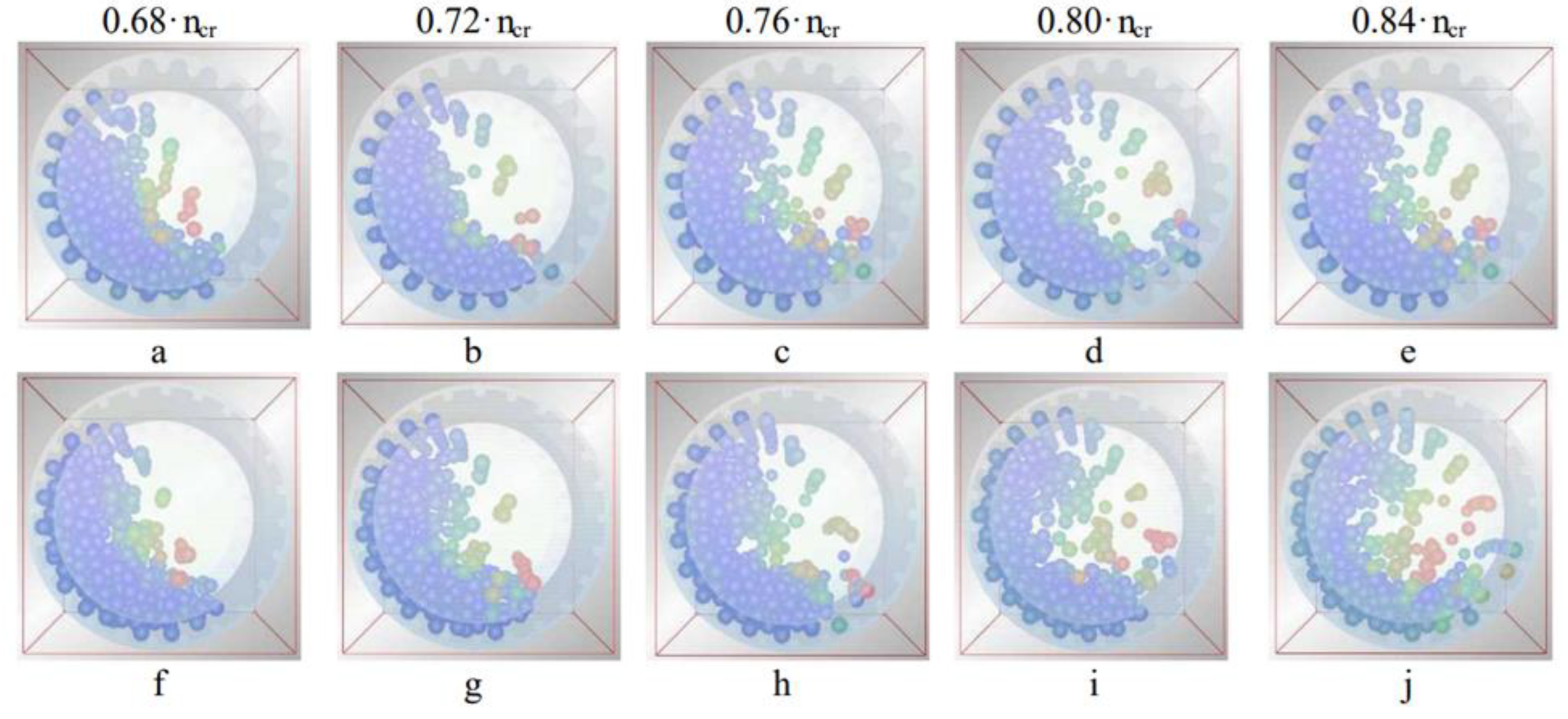

2.3. Motion of Grinding Media in a Ball Mill

The motion of grinding media in a ball mill is essential since it has a great impact on the breakage of ore particles. When the mill speed increases, the charge motion changes from sliding to cascading, then to cataracting and when the critical speed is exceeded, it reaches centrifugation. At very low mill speed, balls experience a sliding motion with charge. Cascading motion is expected at the intermediate speed of about 60% critical speed whilst cataracting occurs at high speeds of about 90%, causing breakage of large ore particles whilst reducing the mill’s energy efficiency. The number of cataracting media increases as mill speed increases [

62]. At 100% critical speed, centrifugation happens, and impact breakage of ore particles does not happen [

63].

Abrasion is dominant at low cascading speeds and impact occurs at cataracting speeds. According to Orozco et al. [

64] increasing the number of balls increases the grinding rate but decreases the energy efficiency of the mill as the balls further increase. This is because the motion of balls will result in increased inelastic collisions between the balls themselves. During milling, it may take a longer time for the balls to capture an ore particle and break it and the balls will be hitting each other all along, hence decreasing energy efficiency.

Research done by Khakhalev et al. [

65] showed that ball motion is also affected by critical speed and liner design, as depicted in

Figure 5. The researcher concluded that the height to which the grinding media is lifted increases with an increased mill speed regardless of the type of liners, hence values of kinetic and potential energy increase. At 80% of the critical speed, there is more liner wear because more grinding media will be hitting the liners.

According to experiments conducted, it has been observed that prolonging the grinding time results in particles being broken effectively by abrasion [

66]. This is because as the grinding time increases, more fine particles are produced, which can be effectively ground by abrasion. One of the major factors also affecting the grinding efficiency is the ore grinding resistance and surface area. Different types of ore have different grinding resistance, hence different breakage rates. Harder ores have a larger grinding resistance than soft ores therefore, hard ores have lower breakage rates than soft ores. Wear resistance depends on the strength of the ore being ground [

67].

2.4. Grinding Media Filling

Amongst other factors to be considered in the ball mill is the grinding media filling level, which affects the interstitial filling between the grinding media [

68]. Interstitial filling are the spaces between balls which are filled with ore material. The amount of grinding media and ore charge should allow free movement in the grinding zone. A low filling level allows the charge material to attain high kinetic energy that causes strong impacts. High filling levels result in a restriction in the movement of charge, causing a low degree of grinding. Very low interstitial filling gives rise to increased grinding media collisions and less ore breakage, whilst also very high interstitial filling gives rise to the cushioning effect and reduces ore breakage as well. Therefore, an optimal interstitial filling is of vital importance for the optimum breakage of ore particles by the grinding media. From one study, at a very low particle load (U), a lot of energy is used up in media-to-media contacts, leaving less energy available to grind particulate mass than the actual energy input to the ball mill [

69]. Various research has been done by so many researchers [

70], [

71], [

72] which showed that the optimum interstitial filling varies from ore to ore. The void fractions in a ball mill affect the internal flow of mass and heat transfer. It also depends on the grinding media shape and in one research, it was observed that cylinders have a lower void fraction than spheres [

73]. The particle packing in the interstitial spaces is dominated by complex physical-mechanical mechanisms. Random particle packing is widely used in industrial production.

2.5. Grinding Media Wear Rate

The performance of grinding media in a ball mill is also measured in terms of its wear rate. Abrasive ores such as gold and copper produce high wear rates of about 120µm/hr [

74]. The wear of grinding media is due to impact, abrasion and corrosion. It is caused by media characteristics and process conditions, such as pH. Ball mills experience more abrasive and corrosive wear than impact wear because of the ball sizes. Corrosive wear is greatly dominant in wet grinding when using steel grinding media and it is responsible for up to 50% of steel grinding media consumption [

75]. Mass loss by corrosion is due to oxidative electrochemical reactions. The wear rate of grinding media is proportional to the surface area exposed to the wearing environment.

Jankovic et al. [

74] observed that the wear rate was higher for one-hour tests than for three-hour tests. The authors suggest that the wear rate of the grinding media varied inversely with milling time. However, different observations were presented in a study conducted by Chenje et al. [

24] where the mass loss of high chromium alloy balls increased linearly with time, and they had a higher wear resistance than forged steel. This observation shows that the materials and processes used to manufacture balls influence the wear properties of the grinding media. Chromium grinding media possesses very high corrosion resistance in the presence of oxygen. Another researcher also concluded that different grades of grinding media have different wear rates [

76]. A review by Conger et al. [

10] showed that the wear rate of grinding media is also affected by conditions such as ore type and the presence of anions in slurry. Research which has already been conducted so far on steel balls has shown a linear behaviour in the wear rate of steel balls [

77]. When balls wear out, their mass is reduced, and this may reduce their ability to break large ore particles, resulting in decreased milling efficiency overall. Wearing of grinding media also changes the ball shape, therefore decreasing mill efficiency since non-spherical balls are produced.

2.6. Effect of Grinding Media on the Grinding Rate

The grinding rate of a ball mill is one of the most essential factors used to evaluate the grinding process. Ball diameter is one of the factors that affects the grinding rate in a ball mill [

78]. The grinding of ore occurs either by abrasion or impact. Particles also undergo weakening due to unsuccessful stressing impacts of insufficient magnitude. The impact from the grinding media produces catastrophic breakage or weakens the ore particles due to repeated stress [

79].

In some batch grinding tests done by Katubwila and Moys [

80] using single-sized grinding media of 30.6, 38.8 and 49.2 mm and a mixture of the grinding media on a coal sample, OEM-BSD (original equipment manufacturer recommended ball size distribution) and EQM-BSD (Equilibrium Ball Size distribution) were used. EQM had the same number of balls in each ball size class with different mass fractions, whilst OEM-BSD had a different number of balls but the same mass fraction in each ball size class. The OEM-BSD had a higher number of small balls, thus a bigger surface area of the balls which increased the rate of fine particle production, albeit with a limited capacity to break larger particles due to a low number of bigger balls. However, the EQM-BSD had an equal number of balls in each ball size class, hence more capable of breaking coarser particles. In comparison, the OEM-BSD was efficient for up to 7mm particle size and EQM-BSD was efficient for particles of more than 7mm. Changing from EQM-BSD to OEM-BSD for -7mm particles increased the grinding rate by 20%. For ore particles greater than 7mm, changing from OEM-BSD to EQM-BSD increased the grinding rate by 45%. From this study, it can be concluded that the ball size distribution affects the grinding rate depending on the ore feed particle size. Cayirli [

81] also agrees with the fact that larger balls are able to crush large particles better but at a lower grinding rate whilst smaller balls are unable to break large ore particles but grind smaller particles at a higher grinding rate but.

Another research done on the grinding rate constant showed that it is affected by the grinding ball diameter. Olejnik [

82] used several sets of grinding media sets of different diameters together with various ores of one size range consisting of granite, quartzite and greywacke of different hardness. After 30 minutes of grinding, different grinding media sets gave different grinding rates. The variability of the grinding rate was caused by a different number of balls in the grinding media sets. However, the grinding rate was similar for the different ores. The study findings agreed with results found by Katubwila and Moys [

80] in previous studies. Differentiating the ball composition using a partial mass of smaller balls at a constant mass increased the probability of finding particles in the grinding medium impact area. For greywacke and granite, smaller grinding media were able to grind larger feed particles, but it was not the same case with quartzite owing to its high elasticity, which would need larger grinding media to break its feed particles. Previous studies done by Olejnik [

83] were also in agreement with the results obtained. Magdalinovic et al. [

84] also showed that bigger balls have a higher milling rate constant for coarser feed size, whilst smaller balls had a higher milling rate constant for finer feed.

A study done by Cuhadaroglu et al. [

85] investigated the effect of media shape on the breakage parameters of colemanite using cylinders and spherical grinding media made from cast iron on 3 mono-sized fraction feed, - 425 + 300 μm, - 300 + 212 μm and - 212 + 150 μm. The specific rate of breakage obtained, and the model parameters showed that cylinders have a higher breakage rate than spheres for all size fractions of the feed. The cylinders had a faster breakage rate for relatively coarse feeds for short grinding periods that were 0.5 to 2 minutes. This is because a shear effect takes place at the beginning of rod grinding, which may cause staged grinding, as shown in

Figure 6. The feed particles would be experiencing ball mill and rod mill conditions due to the contact mechanisms of cylinders, which are linear, area and point contact. However, for longer grinding times surpassing 4 minutes, the spherical grinding media produces a finer product compared to the cylinders, as observed from the product particle size distribution. This is a result of halting the stage grinding as grinding progress because the effective grinding size of ore particles would have been exceeded due to the production of more fines.

In a similar study done by Ipek [

55] investigating the effect of grinding media shape of equal diameters and specific surface area on the breakage rate, cylindrical media had a faster breakage rate compared to spheres. Seven different feed mono-sized fractions were used which were progressively ground from 0.5 min to 8min. For both grinding media, the breakage rate increased from -1180 +850 µm feed size and dropped sharply afterwards. This was because of the large particle sizes, which cannot be properly nipped and broken by both grinding media. For cylindrical media, the breakage rate for coarser size fraction particles was higher than that of finer size fractions.

Ball filling ratio also affects the grinding rate. High mill filling reduces the grinding rate because the collision zone would be saturated. Deniz [

71] in his dry ball mill studies investigated the impacts of media filling on the kinetic breakage parameters of a gypsum sample, and he found that the filling ratio of 0.35 gave the highest grinding rate. Yu et al. [

16] also found that higher contents of the qualified product were produced at 35% media filling ratio.

From the various experiments conducted, it can be deduced that grinding media shape, ball filling ratio and ball size distribution affect the grinding rate in a ball mill.

2.7. Effect of Grinding Media on the Mill Energy Consumption

The specific energy consumed by a ball mill is affected by various parameters of the grinding media. Some of the parameters are the ball size distribution, ball shape and media loading [

38]. According to Longhurst [

86], tests from laboratories and commercial ball mills have shown that low charge ball filling coupled with proper media size distribution can reduce the specific energy by 15-45%.

Media loading is the amount of grinding material fed into the mill. In an experiment to determine the effect of ball loading ratio on a calcite ore, Cayirli [

81] found out that as the ball charge increases, the mill’s energy input also increases and gets to a maximum at 50% ball loading. This is because when the mass inside the mill increases, more energy is needed to turn the mill. Fortsch [

87] also found that when the mill loading is reduced, there is a reduction in mill power draw. However, in a commercial mill study, the findings indicated a negative impact for ball mill loading less than 25%. In some commercial operations, the mill power readings are used to determine the ball filling degree of the mill, even though the mill power also depends on pulp density and liner configuration. A study done by Clermont and De Haas [

88] in a pilot plant showed an increase in product fineness when ball loading increased from 25%-30% and a decrease in energy consumption. Increasing the ball loading from 30% did not further increase the product fineness but also increased the energy input, hence 30% was the optimum ball filling. Panjipour and Barani [

89] during their simulations also found that power draw increases with mill filling. These findings contradict what Touil et al. [

90] found in a study on the energy efficiency of cement finish grinding in a dry batch ball mill. The author found that the energy efficiency factor increases as ball loading increases to 0.38 and then starts to drop afterwards.

Lameck et al. [

45] investigated the effects of three media shapes i.e., cylpebs, spherical and worn balls, on the power draw at different media filling. It was found that the mill power draw is sensitive to media shape. At 72% of the critical speed, the cylpebs and spherical media power draw were almost the same, but beyond that, the power draw of cypebs decreased whilst that of spheres continued to increase. However, at lower speeds, the cylpebs drew more power, followed by worn balls and lastly spherical balls. In another experiment conducted by Shi [

91] at the same specific energy input level, cylpebs with the same charge mass and similar size distribution produced material with a smaller coarser size fraction. This is because cylpebs have a greater surface area as compared to spherical media. Cylpebs also have linear and area contact, which increases the tendency to preferentially break larger particles whilst spheres have only point contact. The laboratory tests done by Kayaci et al. [

92] in milling ceramic raw materials (kaolin, feldspar, clay, and floor tile waste) showed that the use of cylindrical media is better than grinding with spherical balls in terms of energy consumption. The energy consumption for spherical balls was 3.6 Kw after grinding for 420 minutes, producing a 45µm residue of 4.37% whilst that of cylpebs was 2.6kW after grinding for 295 minutes producing a 45µm residue of 4.2%.

Ball size distribution plays a significant role in a ball mill’s energy consumption. A properly seasoned charge of grinding media should be able to break large particles and not produce unnecessary ultrafine particles. In recent research done by AmanNejad and Barani [

93] using DEM to investigate the effect of ball size distribution on ball milling, charging the mill speed with 40% small balls and 60% big balls had a more significant influence on power draw than using mono-sized balls. This is because when there is a homogenous charge, ball segregation is less, therefore the power consumption will be less affected as well. In a previous study done by Panjipour and Barani [

89] using the DEM, the results showed that a constant mill filling change in ball size distribution also resulted in a change in a power draw with the highest power draw experienced when the small balls were 30-40% of the ball charge volume. Also, as the ball filling ratio increased, the influence of the ball size distribution also increased with a maximum power draw at 35% ball filling volume. Petrakis and Komnitsas [

47] also found that there is an optimal specific energy input for a given ball size distribution to get the required product size.

2.8. Effect of Grinding Media on the Mill Efficiency

Ball mill efficiency directly affects the cost of mineral processing. Grinding media also plays a vital role in enhancing the efficiency of a ball mill in terms of its size and mill filling volume. Selecting the most appropriate ball size distribution and ball loading improves the performance of the mill, hence its efficiency.

Ball mill efficiency is affected primarily by the size of the grinding media. This was investigated by Abdelhaffez [

94] by varying grinding media distribution in four groups of 19.5, 38 mm; 19.5, 50 mm; 38, 50 mm and 19.5, 38, 50 mm. The ball size affects the number of balls and the surface area for the same charge weight. As the experiments were conducted, it was noted that the number of balls was the most affected parameter. Though the amounts of required energy were close in value, the first mixture of balls consumed the highest energy and produced the finest product. Different ball loading composition enhances the surface area occupied by ore particles, which promotes faster grinding of a higher amount of ore compared to using mono-sized balls.

In another study to investigate ball size distribution on ball mill efficiency by Hlabangana et al. [

50] using the attainable region technique on a silica ore by dry milling, a three-ball mix of 10mm, 20mm and 50mm was the most effective in grinding a coarser feed and a binary mixture of 10mm and 20mm was most effective in grinding a finer feed. This outlines that the ball size distribution affects the mill performance, hence the mill efficiency according to the feed size of the material. Magdalinovic et al. [

84] after experimental explorations, came up with equations for quartz and copper ore to determine optimum ball size in relation to feed size and also defined a process of making optimal ball charge in order to provide the highest grinding efficiency. Fortsch [

87] also agrees that the grinding efficiency of a ball mill can be improved by theoretical modeling using empirical data to determine the optimal ball size distribution in a ball mill. Hassanzadeh [

7] also found out that proper ball size distribution increases the ball mill’s efficiency in his investigation to evaluate the effect of ball size distribution on the grinding efficiency of a ball mill operating in an industrial condition. In another study done by Muanpaopang et al. [

95] using a Population Balance Model (PBM), the dynamic simulations conducted showed that milling with a ball mixture outperforms milling with a single ball size. Also, a ball size distribution with a uniform mass of balls achieved an 8% increase in the surface area per unit mass of cement (cement-specific surface area) compared to that with a uniform number of balls. However, it is not always when ball size distribution brings a positive result, since the efficiency of the mill is also affected by the feed size. This was shown in a recent experimental study by Petrakis and Komnitsas [

47] done on ferronickel slag with particle size less than 0.85mm where a seasoned charge of balls had a lower grinding efficiency than mono-sized balls with a diameter of 25.4mm.

From a study done by Longhurst [

86] it was shown that the concept of low mill filling level high grinding efficiency has been a matter of debate from long ago, even in Bond’s time. However, with the increase in the size of ball mills, the concept proved to be advantageous and is currently in use nowadays. High mill filling levels were always used to put maximum energy between the trunnion bearings until the use of low filling levels initially was encouraged to prevent a failure on a dual drive ball mill after one of its drives failed, thus a 32% filling level was used which resulted in a gain in efficiency and a minimal loss in production. Fortsch [

87] found similar theories, which gave the same results where ball mill efficiency can be improved by decreasing the grinding media loading to approximately 22%. In a recent experimental study done by Kamarova et al. [

96] to study the effect of grinding parameters on the efficiency of a ball mill in the coal industry at a thermal power plant, the ball loading consisting of a seasoned charge of balls was varied from 14%, 27%, 41%, 55% and 68%. The ball mill was most efficient when the mill was filled at 41%.

In the 1980’s some proponents claimed that the truncated cones had higher efficiencies than spherical balls of equivalent media size distribution because of their relatively low manufacturing costs, but this was proven otherwise by experiments done by Herbst and Lo [

97]. The batch grinding tests using copper porphyry ore showed that balls had a higher breakage function than truncated cones. The selection function for balls was 20% higher than that of truncated cones. The selection function of balls increased with ball diameter whilst that of truncated cones decreased with increasing cone height. Therefore, the breakage rate for truncated cones was lower than that of balls, and that made balls have a higher efficiency than truncated cones.

2.9. Effect of Grinding Media on the Mineral’s Liberation

Inside the ball mill, enhanced liberation of the valuable mineral gives a homogenous product particle size, improves the technical index of the classification circuit, and improves the concentration in subsequent processes. The grinding media, such as steel balls, generate a breakage force that causes fractures on the mineral interface. Different types of grinding media have a different effect on the liberation degree of the valuable mineral.

In experiments done by Si et al. [

98] using magnetite ores to determine the effect of grinding media diameter on the mineral liberation degree, 8 different sizes of steel balls were used i.e., 10mm, 13mm, 16mm, 19mm, 22mm, 25mm, 28mm, and 32mm under the same grinding conditions and the mineral liberation degree of the product was tested using mineral liberation analyser. Some magnetite particles were incompletely liberated whilst others were still intergrown. The breakage force was small when the diameter of the steel balls was small. For 10mm and 13mm, steel balls, the breakage was low, and the breakage mode was by partial fatigue fracture. This reduced their grinding efficiency due to their small diameter, but their mineral liberation degree was better compared to other ball sizes. However, they were rendered not appropriate. As the ball diameter increased, the mineral liberation decreased, but the high breakage energy was generated along the direction of the effect of the force, not at the mineral interface. From this study, after matching the ball diameter and the ground product, it was concluded that for a specific product size, there is a suitable ball diameter that would give the highest degree of liberation due to the impact energy generated. In the experiment 22mm was found to give better liberation and qualified product size. In another study done by Yang et al. [

99] using steel balls of varying diameters from 16-40mm where batch grinding tests were done using mono-sized balls and multi-sized balls. At 30% ball filling using 40mm balls, was the optimum for single-sized balls because it reduced overgrinding significantly though it produced coarser particles. From that same study, it was concluded that the liberation of the locked minerals is dependent on the mill filling rate and ball size. The highest liberation was obtained at a mill filling rate 35% of and ball size of 18 or 40mm. Different ball mixtures also resulted in different liberation degrees, as shown by the product particle size distribution.

3. Comparison of Grinding Media

From the review that has been outlined in this paper, the grinding media can be compared in terms of their types and properties they possess. According to the types of grinding media, cast iron grinding is the hardest grinding media but with the least ductility. They also encounter the highest corrosive wear, therefore, are most suitable for soft ores and for uses in environments where they do not form galvanic reactions. In terms of cost, they are the cheapest. In comparison, high alloy steel balls are the most ductile and wear-resistant grinding media which can withstand corrosive environments. Using chromium grinding media in a wet grinding system improves the flotation in comparison with other steel media. However, its wear resistance is greatly affected by changes in pH and it is also the most expensive media due to the large vast amounts of alloying elements added. Low alloy steel grinding media have inferior qualities than high alloy steel but are better than cast iron grinding media. Only the properties of high alloy cast iron grinding media can be comparable to the high steel alloy grinding media.

A couple of grinding media shapes other than the sphere have been used. Cylpebs have a more specific surface area and bulk density than balls. This has resulted in them having a higher grinding rate than spheres. However, as grinding time increases, their grinding time becomes less than that of spheres because cylpebs are good at grinding coarse particles whilst spheres are good at grinding fine particles. Therefore, the choice between cylpebs and spherical media is also dependent on the feed-to-product specifications, mill speed and subsequent processes. Cylpebs can outperform spherical media when a coarser product is required, whilst on the other hand spherical media can outperform cylpebs when a finer product is required. Worn balls are also produced during milling, which decreases the grinding chamber as compared to spheres hence decreasing the grinding efficiency of the mill. Worn balls also consume more energy than spherical grinding media.

The size of the grinding media is vital for the efficient operation of the ball mill. Large grinding media are efficient in breaking ore particles by impact, whilst small grinding media are efficient in breaking small particles by attrition or abrasion. However, in practice, both large balls and small balls are fed into the mill because the feed also contains both fine and coarse ore particles. For the same ball charge weight, small grinding media has more surface area and a higher grinding rate than larger grinding media. For some hard ores like quartz, the grinding rate is higher when using large grinding media. The effect of grinding rate does not solely rely on media size but also on ore characteristics. The shoulder position of the larger grinding media in a ball mill is always less than that of the larger grinding media. This is because less energy is required to lift a smaller grinding media than larger grinding media.

The density of different grinding media is also different. Grinding media with high density is suitable for hard and coarse ores. Grinding media with low density doesn’t possess enough breakage force but may only weaken the ore particles hence smaller media density results in a decrease in breakage rate. Grinding media with high density consumes more energy than grinding media with less density.

3.1. Research Outlooks

From the review carried out on the use of grinding media in ball mills, there were various areas observed which are still green as far as research is concerned, and thus would be improved by further research.

A few studies have been conducted using other grinding media shapes alone, like ellipsoids, cylpebs which are not spherical. Spheres still prove to be the best, but there is a chance of other shapes being better if their relationship between media shape and other operating parameters (milling speed, liner profiles and filling ratio) is further investigated. In some experiments using polyhedral and spherical media, the power consumption difference was negligible, and at a slightly higher mill filling, the polyhedral media consumed less power [

54]. RGM performed better than spherical media, as it produced a more undersized product. However, there is a need to define a coefficient to obtain an RGM work index from standard bond tests. These observations can serve as a green light to further investigate other media shapes to enhance ball mill performance [

57]. Still, very little is known about the effect of various mill conditions on the performance of mixed grinding media shapes. As milling proceeds, spherical balls tend to change shape. Some mixtures of media shape may be beneficial, whilst others can have a negative impact. Mixture of spherical and worn shape showed a decrease in mill performance whilst pebble and steel balls enhanced the mill performance. Therefore, there is a need to really investigate the effect of mill conditions on various mixed grinding media shapes [

11].

According to Hlabangana et al. [

50] there is a need to find a correlation factor between the ball size distribution and feed size to further enhance mill performance since the authors found that the performance of a particular ball size distribution is dependent on the feed size. Katubwila [

80] estimated the effect of ball size and ball size distribution and came up with an equation to be used for parameter estimation of breakage properties of coal. However, further research is needed to investigate whether the constant, n is material dependent in the following equation.

where: K is the maximum breakage rate factor

x is size of particle to be ground

D is the ball diameter

It has been shown by experiments that increasing hardness of the grinding media also increases the abrasion resistance of the media, but it is not the only factor. Therefore, the correlation between corrosion resistance and hardness has to be established [

42]. Although there have been many ball mill power models up to date, they do not incorporate the effect of media shape, which has been shown by many studies that it has a significant effect on load behaviour inside the mill [

45].

There is so much information regarding the effect of grinding media on the grinding rate, mill efficiency and energy consumption, however there is very little information on influence of grinding media shape on the liberation of minerals which makes it a research gap that needs to be explored and filled by research.

4. Conclusions

From this review paper, it is apparent that a lot of research has been conducted on the grinding process using a ball mill, particularly on the grinding media. However, there are still many areas concerning the ball mill operation as a function of the grinding media that still need to be studied to get a profound understanding of the grinding process. There is still much more work to be done to come up with better alternatives for grinding media, which can withstand wear better and prolong the service life of the grinding media. Properties of grinding media, such as shape, hardness and size, should be further exploited to increase mill efficiency.

Author Contributions

Nyasha Matsanga: Conceptualisation, Investigation, writing original draft. Willie Nheta: Review and editing, Supervision, Project administration. Ngonidzashe Chimwani; Review and editing, Supervision. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This review paper received no external funding.

Data Availability Statement

No datasets were generated or analyzed during the current study. Any information regarding this review can be obtained from the authors upon request.

Acknowledgments

The authors also acknowledge the contributions of anonymous reviewers that improved this work.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

References

- Napier-Munn, T. Is progress in energy-efficient comminution doomed? Miner. Eng. 2015, 73, 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ballantyne, G. Quantifying the additional energy consumed by ancillary equipment and embodied in grinding media in comminution circuits. SAG Conference, pp. 1–12, Sep. 2019.

- Fatahi, R.; Nasiri, H.; Dadfar, E.; Chelgani, S.C. Modeling of energy consumption factors for an industrial cement vertical roller mill by SHAP-XGBoost: a "conscious lab" approach. Sci. Rep. 2022, 12, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jeswiet, J.; Szekeres, A. Energy Consumption in Mining Comminution. Procedia CIRP 2016, 48, 140–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- W. Valery, A. W. Valery, A. Jankovic, and K. Duffy, “ADVANCES IN ORE COMMINUTIONPRACTICES OVER THE LAST 25 YEARS,” In XVI Balkan Mineral Processing Congress, Belgrád, Szerbia, 2015; pp. 123–130. Available online: https://www.researchgate. 3097. [Google Scholar]

- Machado, M.V.C.; Santos, D.A.; Barrozo, M.A.S.; Duarte, C.R. Experimental and Numerical Study of Grinding Media Flow in a Ball Mill. Chem. Eng. Technol. 2017, 40, 1835–1843. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hassanzadeh, “The Effect of Make-up Ball Size Regime on Grinding Effciency of Full-scale Ball Mill Fine, coarse and fine/coarse particle processing in mineral processing systems View project A Study on Batch and Industrial Flotation of Copper Porphyry Ores View project,” In XVII Balkan Mineral Processing Congress (BMPC); 2017; pp. 117–123. Available online: https://www.researchgate. 3208.

- Van Hinsberg, v.j. , 2008. Wills’mineral processing technology: An introduction to the practical aspects of ore treatment and mineral recovery: by BA Wills and TJ Napier-Munn. Butterworth-Heinemann (Elsevier), Burlington, Massachusetts. 2006; 456p. ISBN: 978-0-7506-4450-1.

- Swart, C.; Gaylard, J.M.; Bwalya, M.M. A Technical and Economic Comparison of Ball Mill Limestone Comminution with a Vertical Roller Mill. Miner. Process. Extr. Met. Rev. 2021, 43, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Conger, W.; DuPont, J.F.; McIvor, R.E.; Weldum, T.P. Ball mill media optimization. Min. Eng. 2018, 28–27. [Google Scholar]

- Dökme, F.; Kimyasallar, Ş.; Soda, G.; Fabrikası, S.A.Ş.K. “INVESTIGATION OF EFFECTS OF GRINDING MEDIA SHAPES TO THE GRINDING EFFICIENCY IN BALL”. Sisecam Chem. 2015, 1, 1–2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Corin, K.; Song, Z.; Wiese, J.; O'Connor, C. Effect of using different grinding media on the flotation of a base metal sulphide ore. Miner. Eng. 2018, 126, 24–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Han, Y.; Kawatra, S.K. Effects of Grinding Media on Grinding Products and Flotation Performance of Sulfide Ores. Miner. Process. Extr. Met. Rev. 2020, 42, 172–183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- P. Muhayimana, J. K. P. Muhayimana, J. K. Kimotho, and H. M. Ndiritu, “A Review of Ball mill grinding process modeling using Discrete Element Method.” In Proceedings of the Sustainable Research and Innovation Conference, 2022; pp. 221–229.

- Wang, M.; Yang, R.; Yu, A. DEM investigation of energy distribution and particle breakage in tumbling ball mills. Powder Technol. 2012, 223, 83–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, J.; Qin, Y.; Gao, P.; Han, Y.; Li, Y. An innovative approach for determining the grinding media system of ball mill based on grinding kinetics and linear superposition principle. Powder Technol. 2020, 378, 172–181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kelsall, D.; Stewart, P.; Weller, K. Continuous grinding in a small wet ball mill. Part IV. A study of the influence of grinding media load and density. Powder Technol. 1973, 7, 293–301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, Q.; Noble, A.; Talan, D. Exploratory investigation on the use of low-cost alternative media for ultrafine grinding of coal. Int. J. Coal Prep. Util. 2020, 42, 2127–2144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prziwara, P.; Hamilton, L.; Breitung-Faes, S.; Kwade, A. Impact of grinding aids and process parameters on dry stirred media milling. Powder Technol. 2018, 335, 114–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- K. P. Simba, N. K. P. Simba, N. Hlabangana, and D. Hildebrandt, “Fineness of the Grind produced by Mixtures of Grinding media of Different shapes,” 16th International Mineral Processing Symposium, 2018; pp. 388–393. Available online: https://www.researchgate. 3394. [Google Scholar]

- Koval, A.D.; Efremenko, V.G.; Brykov, M.N.; Andrushchenko, M.I.; Kulikovskii, R.A.; Efremenko, A.V. Principles of development of grinding media with increased wear resistance. Part 2. Optimization of steel composition to suit conditions of operation of grinding media. J. Frict. Wear 2012, 33, 153–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- V. ’Rajagopal and I. ’Iwasaki, “Nature of Corrosive and Abrasive Wear of Chromium-Bearing Cast Iron Grinding Media,” NACE 1998, 48.

- Rajagopal, V.; Iwasaki, I. The Properties and Performance of Cast Iron Grinding Media. Miner. Process. Extr. Met. Rev. 1992, 11, 75–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chenje, T.; Simbi, D.; Navara, E. Relationship between microstructure, hardness, impact toughness and wear performance of selected grinding media for mineral ore milling operations. Mater. Des. 2004, 25, 11–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Remark, J.F.; Wick, O.J. Corrosion control in Ball and Rod Mills. NACE 1976, 76, 121. [Google Scholar]

- Lu, Z.-L.; Zhou, Y.-X.; Rao, Q.-C.; Jin, Z.-H. An investigation of the abrasive wear behavior of ductile cast iron. J. Mater. Process. Technol. 2001, 116, 176–181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chenje, T.; Simbi, D.; Navara, E. Wear performance and cost effectiveness––a criterion for the selection of grinding media for wet milling in mineral processing operations. Miner. Eng. 2003, 16, 1387–1390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- T. Rahman, “Development of Grinding Media Balls Using Locally Available Materials,” In the Third International Conference on Structure, Processing and Properties of Materials 2010, SPPM 2010 24-, Dhaka, Bangladesh, SPPM 2010 A11. 26 February.

- Ngqase, M.; Pan, X. An Overview on Types of White Cast Irons and High Chromium White Cast Irons. 2020, 1495, 012023. [CrossRef]

- Gates, J.; Dargusch, M.; Walsh, J.; Field, S.; Hermand, M.-P.; Delaup, B.; Saad, J. Effect of abrasive mineral on alloy performance in the ball mill abrasion test. Wear 2008, 265, 865–870. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- S. and H. S. and R. T. I. and O. T. Usman Husni and Fonna, “The Effect of Hardening on Mechanical Properties of Low Alloy Steel Grinding Media,” in Proceedings of the 2nd International Conference on Experimental and Computational Mechanics in Engineering: ICECME 2020, Banda Aceh, –14, Akhyar, Ed. Singapore: Springer Singapore, 2021, pp. 459–469. 13 October. [CrossRef]

- Tanaka, Y.; Pahlevani, F.; Kitamura, S.-Y.; Privat, K.; Sahajwalla, V. Behaviour of Sulphide and Non-alumina-Based Oxide Inclusions in Ca-Treated High-Carbon Steel. Met. Mater. Trans. B 2020, 51, 1384–1394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- J. Kinal, C. J. J. Kinal, C. J. Greet, R. Whittering, and G. Qld, “Metallurgical Improvements at Kagara’s Mount Garnet Mine Through the Use of High Chrome Grinding Media,” In Proceedings of Metallurgical Plant Design and Operating Strategies Conference, AusIMM (pp. 33-46), 2006.

- Li, S.; Yu, H.; Lu, Y.; Lu, J.; Wang, W.; Yang, S. Effects of titanium content on the impact wear properties of high-strength low-alloy steels. Wear 2021, 474–475, 203647. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Greet, C.; Small, G.; Steinier, P.; Grano, S. The Magotteaux Mill®: investigating the effect of grinding media on pulp chemistry and flotation performance. Miner. Eng. 2004, 17, 891–896. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cullinan, V.J.; Grano, S.R.; Greet, C.J.; Johnson, N.W.; Ralston, J.; Wark, I. Investigating fine galena recovery problems in the lead circuit of mount isa mines lead/zinc concentrator part 1: grinding media effects. Miner. Eng. 1999, 12, 147–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, G.; Tao, D.; Parekh, B. A laboratory study of high chromium alloy wear in phosphate grinding mill. Int. J. Miner. Process. 2006, 80, 35–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stoimenov, N.; Karastoyanov, D.; Klochkov, L. Study of the factors increasing the quality and productivity of drum, rod and ball mills. RECENT ADVANCES ON ENVIRONMENT, CHEMICAL ENGINEERING AND MATERIALS. LOCATION OF CONFERENCE, MaltaDATE OF CONFERENCE; p. 020024.

- Yildinm, K.; Silica, U.S.; Austin, L.G.; Cho, H. A Study of Mill Power as a Function of Media Type and Shape. Part. Sci. Technol. 1997, 15, 179–179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harris, C.C.; Schnock, E.M.; Arbiter, N. Grinding Mill Power Consumption. Miner. Process. Extr. Met. Rev. 1985, 1, 297–345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, P.; Zhou, W.; Han, Y.; Li, Y.; Ren, W. Enhancing the capacity of large-scale ball mill through process and equipment optimization: An industrial test verification. Adv. Powder Technol. 2020, 31, 2079–2091. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aissat, S.; Zaid, M.; Sadeddine, A. Correlation between hardness and abrasive wear of grinding balls. Met. Res. Technol. 2020, 117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zurnadzhy, V.I.; Efremenko, V.G.; Wu, K.M.; Lekatou, A.G.; Shimizu, K.; Chabak, Y.G.; Zotov, D.S.; Dunayev, E.V. Quenching and Partitioning–Based Heat Treatment for Rolled Grinding Steel Balls. Met. Mater. Trans. A 2020, 51, 3042–3053. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cho, H.; Kwon, J.; Kim, K.; Mun, M. Optimum choice of the make-up ball sizes for maximum throughput in tumbling ball mills. Powder Technol. 2013, 246, 625–634. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- N. Nistlaba and S. Lameck, “Effects of grinding media shapes on ball mill performance,” Master’s Thesis, University of the Witwatersrand, 2005; pp. 1–146.

- Km, K. The Effect of Ball Size Diameter on Milling Performance. J. Mater. Sci. Eng. 2014, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petrakis, E.; Komnitsas, K. Effect of Grinding Media Size on Ferronickel Slag Ball Milling Efficiency and Energy Requirements Using Kinetics and Attainable Region Approaches. Minerals 2022, 12, 184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bu, X.; Chen, Y.; Ma, G.; Sun, Y.; Ni, C.; Xie, G. Wet and dry grinding of coal in a laboratory-scale ball mill: Particle-size distributions. Powder Technol. 2019, 359, 305–313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shin, H.; Lee, S.; Jung, H.S.; Kim, J.-B. Effect of ball size and powder loading on the milling efficiency of a laboratory-scale wet ball mill. Ceram. Int. 2013, 39, 8963–8968. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hlabangana, N.; Danha, G.; Muzenda, E. Effect of ball and feed particle size distribution on the milling efficiency of a ball mill: An attainable region approach. South Afr. J. Chem. Eng. 2018, 25, 79–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shahbazi, B.; Jafari, M.; Parian, M.; Rosenkranz, J.; Chelgani, S.C. Study on the impacts of media shapes on the performance of tumbling mills – A review. Miner. Eng. 2020, 157, 106490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- M. A. van Nierop and M. H. Moys, “Discrete Element method simulations: predicting grinding mill load behaviour.,” Chemical Technology, vol. 1, pp. 3–6, Nov. 1999.

- Aldrich, C. Consumption of steel grinding media in mills – A review. Miner. Eng. 2013, 49, 77–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kiangi, K.; Potapov, A.; Moys, M. DEM validation of media shape effects on the load behaviour and power in a dry pilot mill. Miner. Eng. 2013, 46-47, 52–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ipek, H. The effects of grinding media shape on breakage rate. Miner. Eng. 2006, 19, 91–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simba, K.P.; Moys, M.H. Effects of mixtures of grinding media of different shapes on milling kinetics. Miner. Eng. 2014, 61, 40–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kolev, N.; Bodurov, P.; Genchev, V.; Simpson, B.; Melero, M.G.; Menéndez-Aguado, J.M. A Comparative Study of Energy Efficiency in Tumbling Mills with the Use of Relo Grinding Media. Metals 2021, 11, 735. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ji, P.; Xie, G.; Xie, N.; Li, J.; Chen, J.; Chen, J. Microwave Absorbing Properties of Flaky Carbonyl Iron Powder Prepared by Rod Milling Method. J. Electron. Mater. 2019, 48, 2495–2500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, C.; Gao, Z. Effect of grinding media on the surface property and flotation behavior of scheelite particles. Powder Technol. 2017, 322, 386–392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, L.; Xu, L.; Shi, X.; Meng, J.; Liu, R. Microscale insights into the influence of grinding media on spodumene micro-flotation using mixed anionic/cationic collectors. Int. J. Min. Sci. Technol. 2021, 32, 171–179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- F. von Kfiiger, J. F. von Kfiiger, J. Donda, M. Drummond, A. Peres, E. de Minas, and O. Preto, “The effect of using concave surfaces as grinding media,” In Developments in Mineral Processing, vol. 13, pp. C4-86, 2000.

- Bian, X.; Wang, G.; Wang, H.; Wang, S.; Lv, W. Effect of lifters and mill speed on particle behaviour, torque, and power consumption of a tumbling ball mill: Experimental study and DEM simulation. Miner. Eng. 2017, 105, 22–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ali, Y.; Garcia-Mendoza, C.D.; Gates, J.D. Effects of ‘impact’ and abrasive particle size on the performance of white cast irons relative to low-alloy steels in laboratory ball mills. Wear 2019, 426-427, 83–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Orozco, L.F.; Nguyen, D.-H.; Delenne, J.-Y.; Sornay, P.; Radjai, F. Discrete-element simulations of comminution in rotating drums: Effects of grinding media. Powder Technol. 2019, 362, 157–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- A Khakhalev, P.; Bogdanov, V.; Kovshechenko, V.M. Kinetic parameters of grinding media in ball mills with various liner design and mill speed based on DEM modeling. 2018, 327. 327. [CrossRef]

- de Carvalho, R.M.; Campos, T.M.; Faria, P.M.; Tavares, L.M. Mechanistic modeling and simulation of grinding iron ore pellet feed in pilot and industrial-scale ball mills. Powder Technol. 2021, 392, 489–502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shvedov, K.N.; Galim’yanov, I.K.; Kazakovtsev, M.A. Production of Grinding Balls of High Surface and Normalized Volume Hardness. Metallurgist 2020, 64, 499–507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sitotaw, Y.W.; Habtu, N.G.; Gebreyohannes, A.Y.; Nunes, S.P.; Van Gerven, T. Ball milling as an important pretreatment technique in lignocellulose biorefineries: a review. Biomass- Convers. Biorefinery 2021, 13, 15593–15616. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]