Submitted:

20 April 2023

Posted:

21 April 2023

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Results and discussion

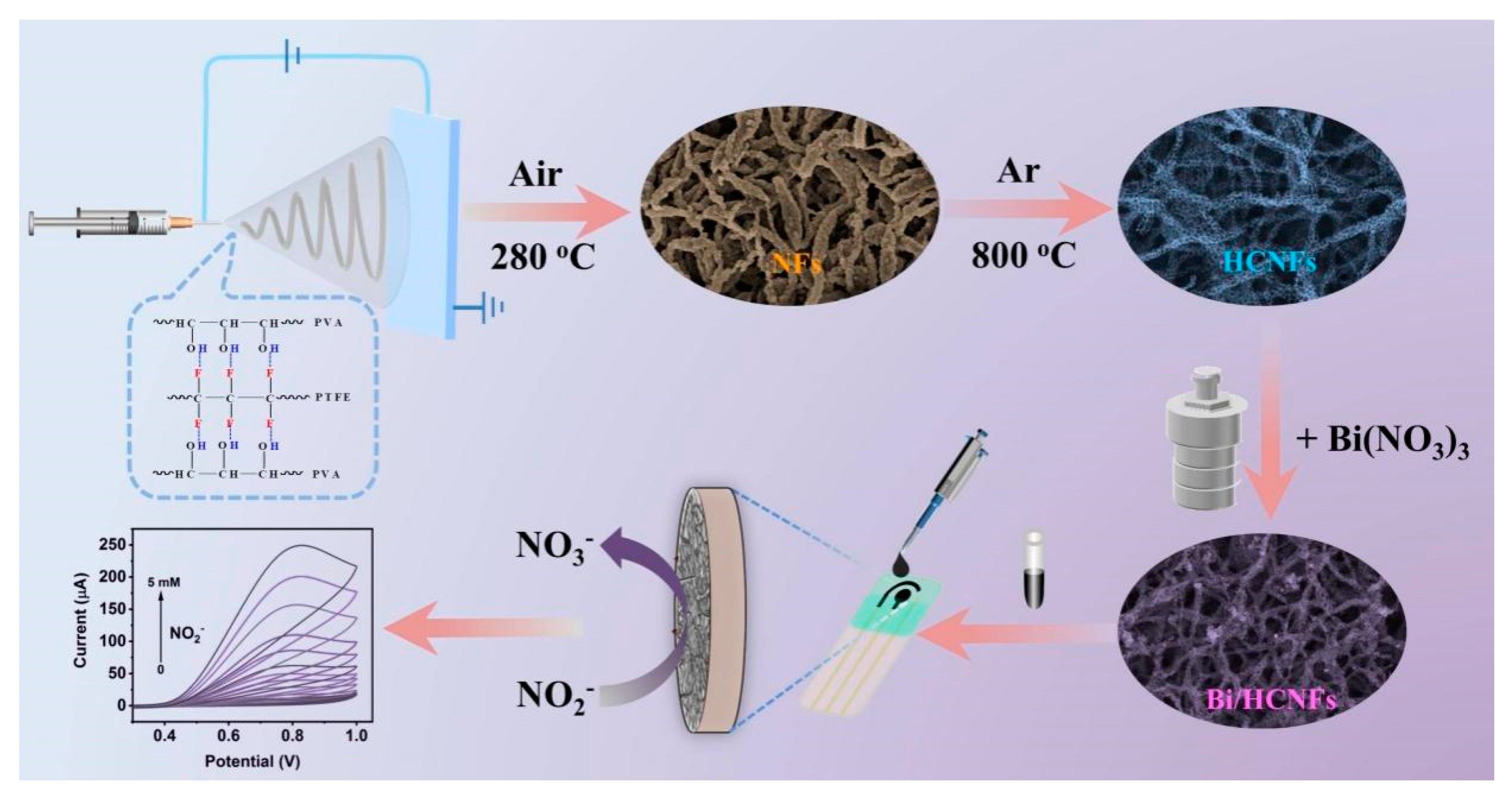

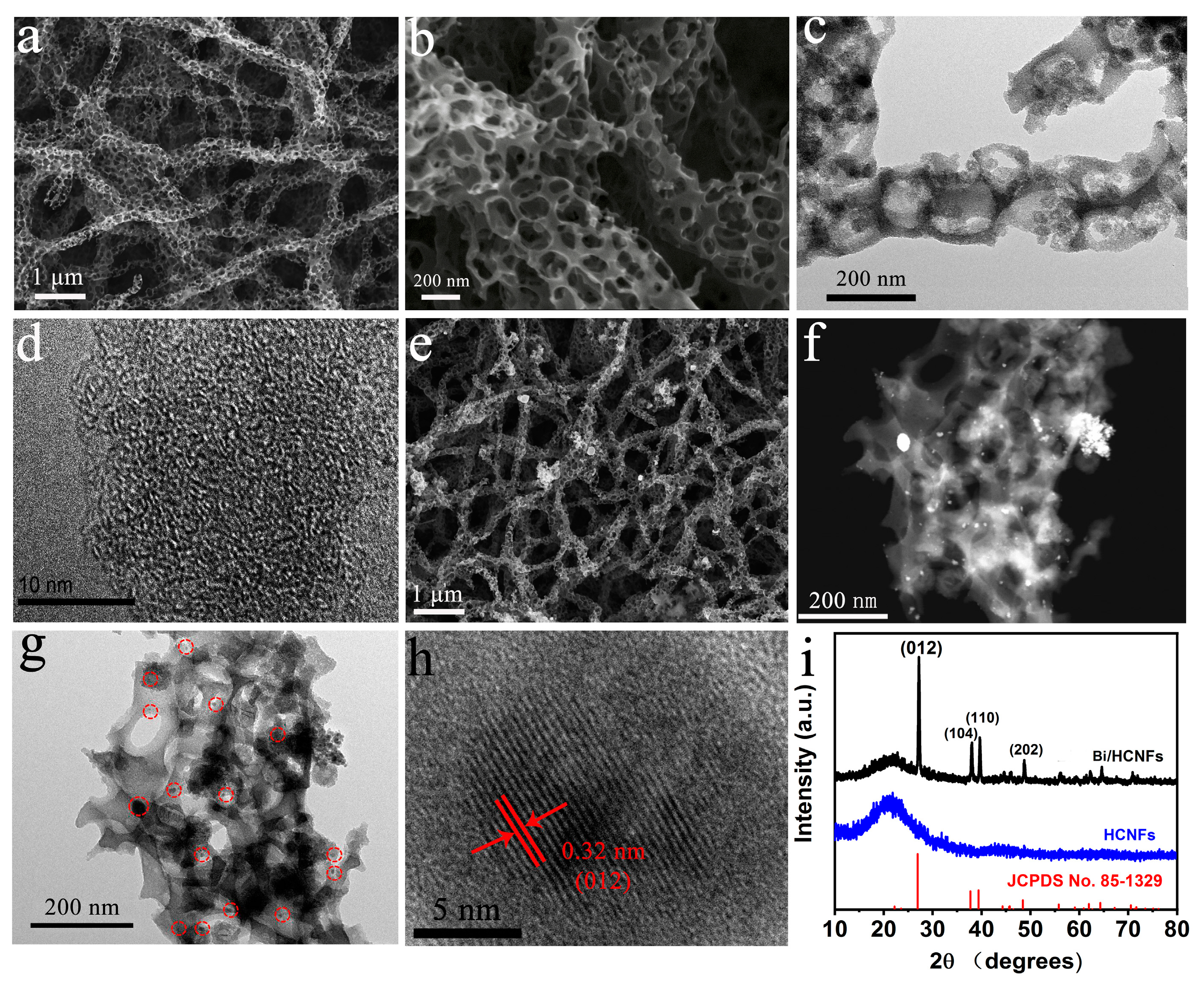

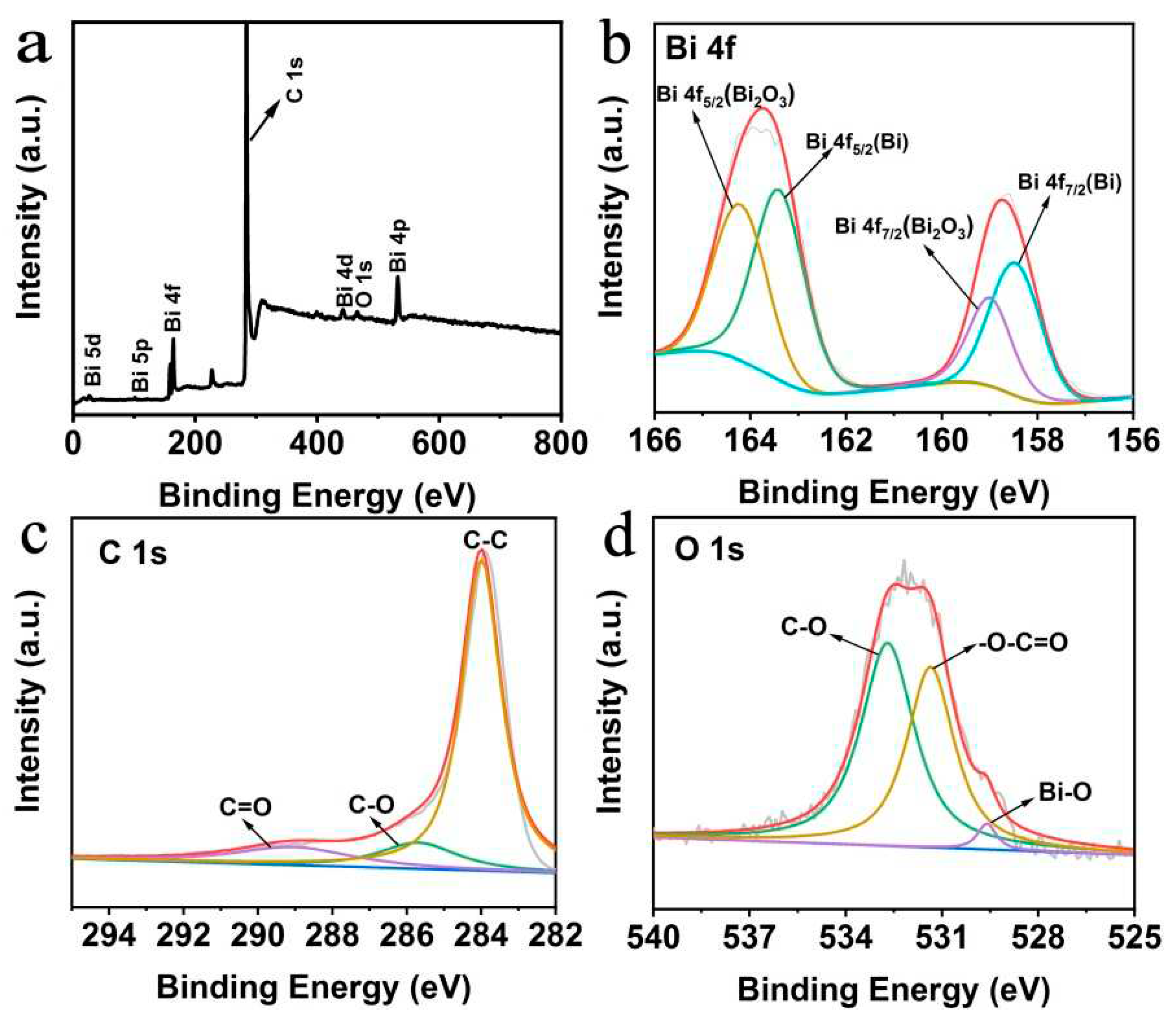

2.1. Synthesis and characterization of Bi/HCNFs

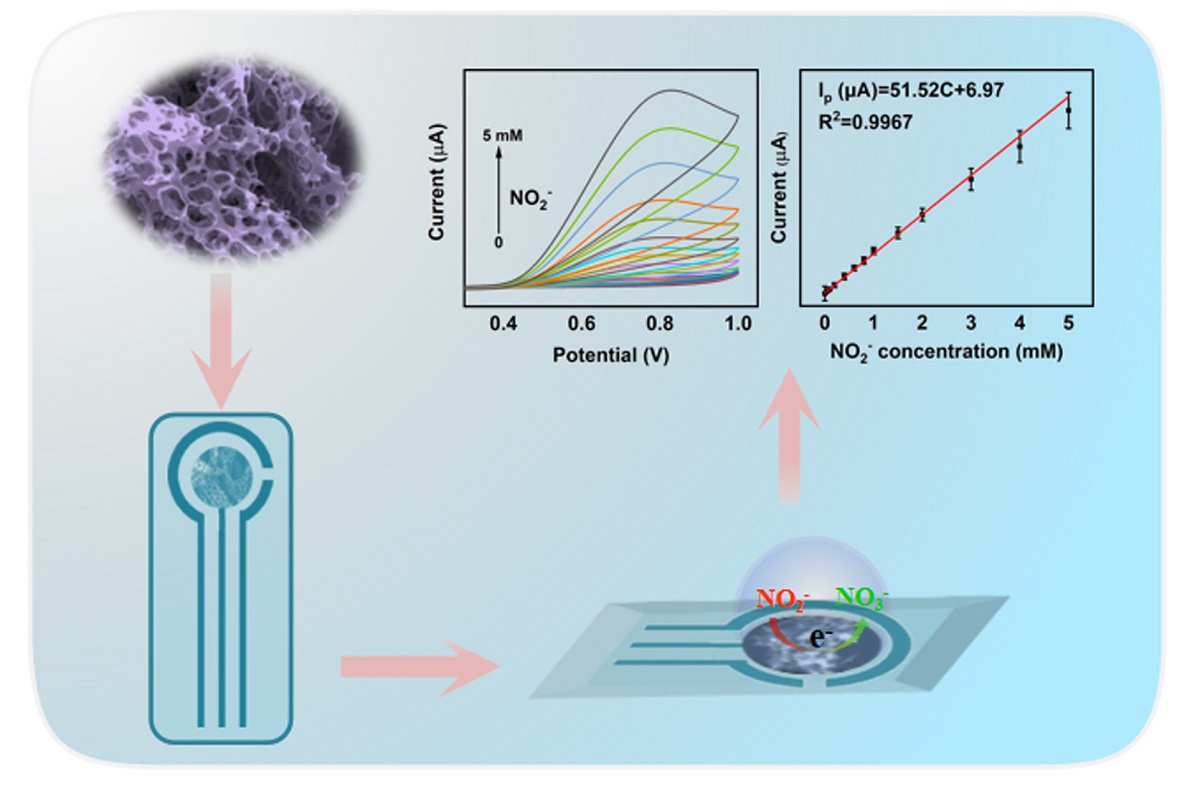

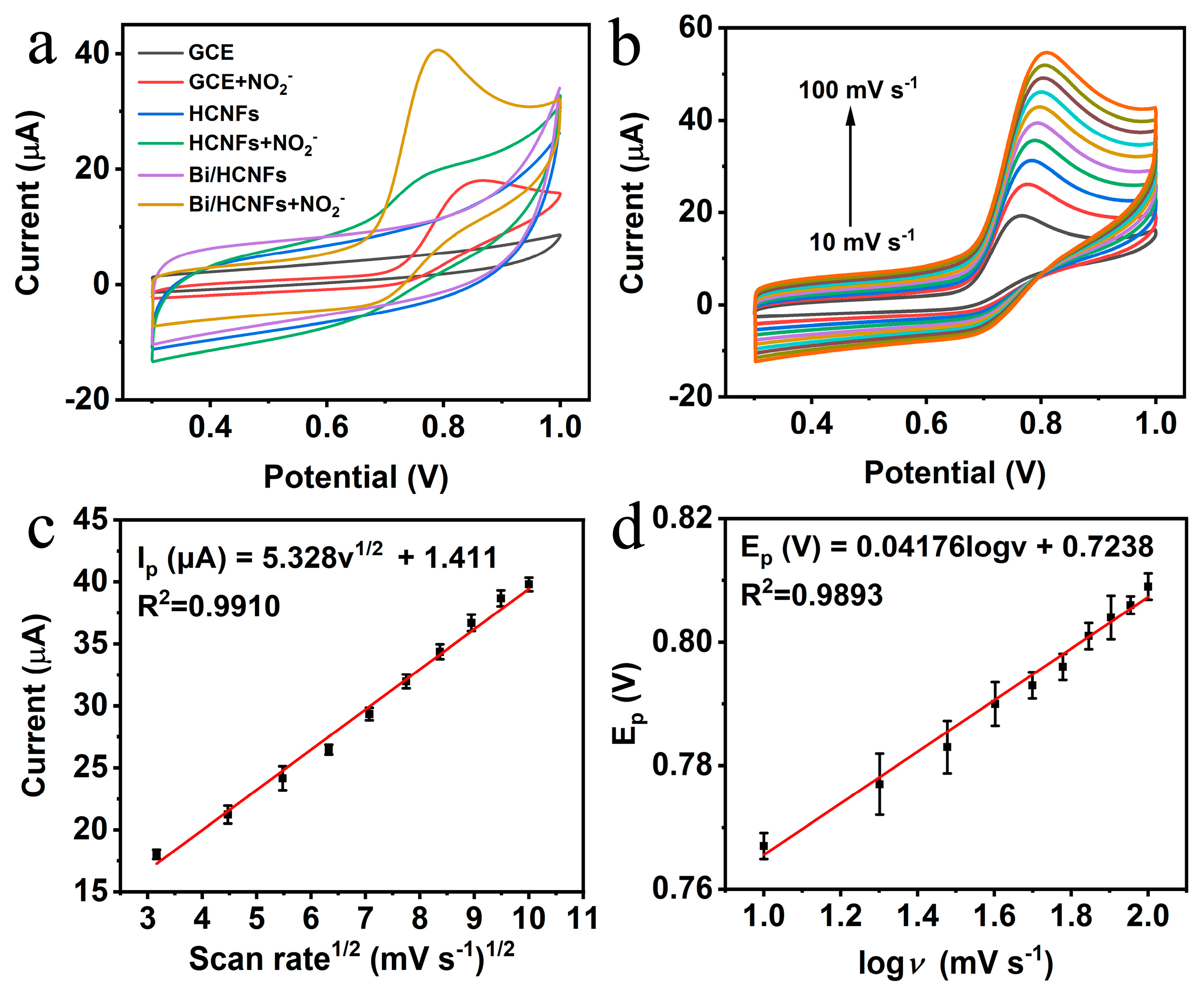

2.2. Investigation of electrocatalytic behavior of Bi/HCNFs toward NO2-

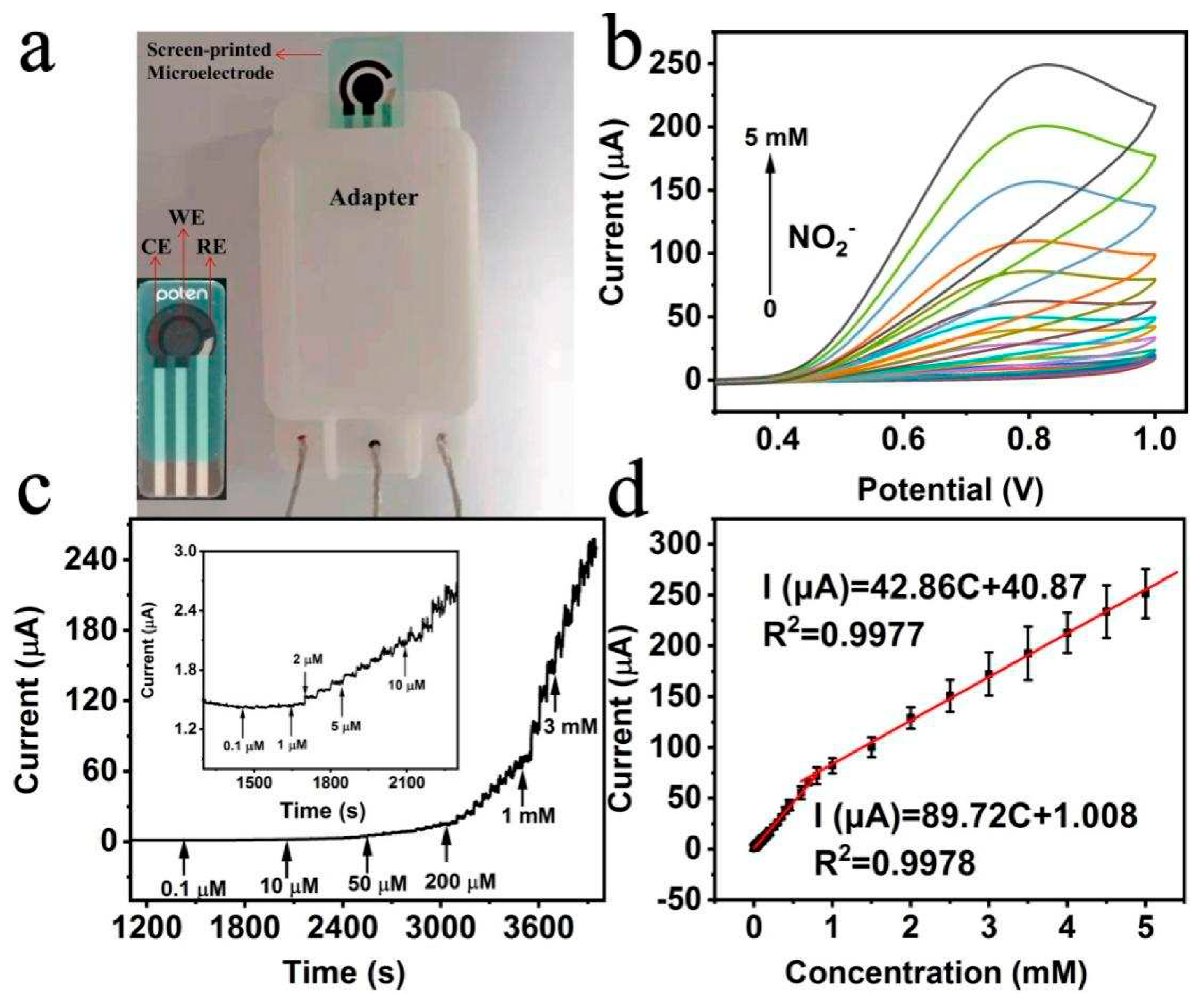

2.3. Detection of nitrite based on Bi/HCNFs electrode

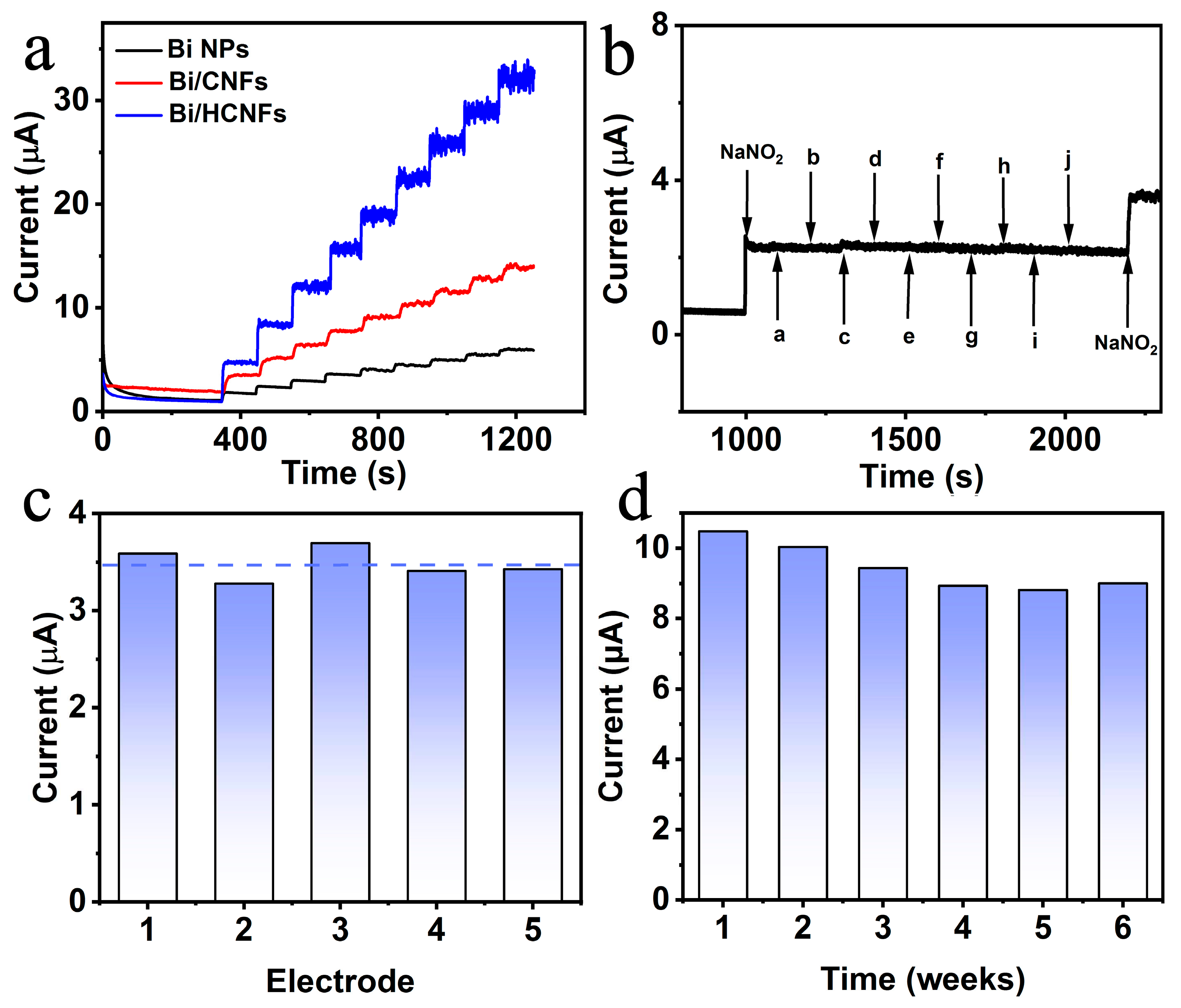

2.4. Interference, reproducibility and stability of Bi/HCNFs-SPE and real sample analysis

Materials and Methods

3.1. Reagent and materials

3.2. Characterizations

3.3. Synthesis of HCNFs

3.4. Synthesis of Bi/HCNFs

3.5. The pretreated of actual samples and spectrophotometric test of nitrite

3.6. Electrochemical properties investigation of Bi/HCNFs

4. Conclusion

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Li, X. Ping; J. & Ying, Y. Recent developments in carbon nanomaterial-enabled electrochemical sensors for nitrite detection. TrAC Trends in Anal. Chem. 2019, 113, 1–12. [Google Scholar]

- Wolff, I. A.; Wasserman, A.E. Nitrates, nitrites, and nitrosamines. Science 1972, 177, 15–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, C.; Howes, B.D.; Smulevich, G.; Rumpel, S.; Reijerse, E.J.; Lubitz, W.; Cox, N.; Knipp, M. Nitrite dismutase reaction mechanism: kinetic and spectroscopic investigation of the interaction between nitrophorin and nitrite. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2015, 137, 4141–4150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hegesh, E.; Shiloah, J. Blood nitrates and infantile methemoglobinemia. Clin. Chim. Acta 1982, 125(2), 107–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan,B. ; Zhang, J.; Zhang, R.; Shi, H.; Wang, N.; Li, J.; Ma, F.; Zhang, D. Cu-based metal–organic framework as a novel sensing platform for the enhanced electro-oxidation of nitrite. Sens. Actuators B: Chem. 2016, 222, 632–637. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Huang, X.; Liu, C.; Shi, H.; Hu, H. Nitrogen removal enhanced by intermittent operation in a subsurface wastewater infiltration system. Ecol. Eng. 2005, 25, 419–428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Radhakrishnan, S.; Krishnamoorthy, K.; Sekar, C.; Wilson, J.; Kim, S.J. A highly sensitive electrochemical sensor for nitrite detection based on Fe2O3 nanoparticles decorated reduced graphene oxide nanosheets. Appl. Catal. B: Environ. 2014, 148-149, 22–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, Z.; Xue, W.; Chen, H.; Lin, J.M. Peroxynitrous-acid-induced chemiluminescence of fluorescent carbon dots for nitrite sensing. Anal. Chem. 2011, 83, 8245–8251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, Z.; Li, J.; Hu, X.; Cai, Z.; Dou, X. Ultrasensitive, specific, and rapid fluorescence turn-on nitrite sensor enabled by precisely modulated fluorophore binding. Adv. Sci. 2020, 7, 2002991. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.; Kang, S.; Wang, G.; Zhang, Y.; Zhao, H. Fluorescence determination of nitrite in water using prawn-shell derived nitrogen-doped carbon nanodots as fluorophores. ACS Sensors 2016, 1(7), 875–881. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Antczak-Chrobot, A.; Bąk, P.; & Wojtczak, M. The use of ionic chromatography in determining the contamination of sugar by-products by nitrite and nitrate. Food Chem. 2018, 240, 648–654. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nam, J.; Jung, I.B.; Kim, B.; Lee, S.M.; Kim, S.E.; Lee, K.N.; Shin, D.S. A colorimetric hydrogel biosensor for rapid detection of nitrite ions. Sens. Actuators B: Chem. 2018, 270, 112–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, Y.; Zhang, R.; Dong, C.; Cheng, F.; Guo, Y. Sensitive electrochemical sensor for nitrite ions based on rose-like AuNPs/MoS2/graphene composite. Biosens. Bioelectron. 2019, 142, 111529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Li, M.; Yang, S.; Shan, J. A novel electrochemical sensor based on TiO2–Ti3C2TX/CTAB/chitosan composite for the detection of nitrite. Electrochim. Acta 2020, 359, 136938. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, F.; Lv, X.; Zhu, X.; Du, J.; Lu, S.; Alshehri, A.A.; Alzahrani, K.A.; Zheng, B.; Sun, X. Bi nanodendrites for efficient electrocatalytic N2 fixation to NH3 under ambient conditions. Chem. Commun. 2020, 56, 2107–2110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, F.; Zhang, L.; Wang, T.; Zhang, F.; Liu, Q.; Zhao, H.; Zheng, B.; Du, J.; Sun, X. In situ derived Bi nanoparticles confined in carbon rods as an efficient electrocatalyst for ambient N2 reduction to NH3. Inorg. Chem. 2021, 60, 7584–7589. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, J.; Du, H.L.; Nguyen, C.K.; B. Suryanto, H.R.; Simonov, A.N.; MacFarlane, D.R. Electroreduction of nitrates, nitrites, and gaseous nitrogen oxides: a potential source of ammonia in dinitrogen reduction studies. ACS Energy Lett. 2020, 5, 2095–2097. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fang, Z.; Wu, P.; Qian, Y.; Yu, G. Gel-derived amorphous BiNi alloy promotes electrocatalytic nitrogen fixation via optimizing nitrogen adsorption and activation. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2020, 60, 4275–4281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yin, H.; Li, Q.; Cao, M.; Zhang, W.; Zhao, H.; Li, C.; Huo, K.; Zhu, M. Nanosized-bismuth-embedded 1D carbon nanofibers as high-performance anodes for lithium-ion and sodium-ion batteries. Nano Res. 2017, 10, 2156–2167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jeromiyas, N.; Elaiyappillai, E.; Kumar, A.S.; Huang, S.T.; Mani,V. Bismuth nanoparticles decorated graphenated carbon nanotubes modified screen-printed electrode for mercury detection. J. Taiwan Inst. Chem. E. 2019, 95, 466–474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, S.; Yang, Y.; Liu, L.; Zhao, Q. Electron transfer-induced catalytic enhancement over bismuth nanoparticles supported by N-doped graphene. Chem. Eng. J. 2018, 334, 1691–1698. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Kaskel, S. KOH activation of carbon-based materials for energy storage. J. Mater. Chem. 2012, 22, 23710. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu,Y. ; Murali, S.; Stoller, M.; Ganesh, K.J.; Cai, W.; Ferreira, P.J.; Pirkle, A.; Cychosz, K.A.; Thommes, M.; Su, D.; Stach, E.A.; Ruoff, R.S. Carbon-based supercapacitors produced by activation of graphene. Science 2011, 332, 1537–1541. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, P.; Zhang, D.; Ma, F.; Ou, Y.; Chen, Q.N.; Xie, S.; Li, J. Mesoporous carbon nanofibers with a high surface area electrospun from thermoplastic polyvinylpyrrolidone. Nanoscale 2012, 4, 7199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, Y.; Zhang, C.; Zhou, M.; Fu, Q.; Zhao, C.; Wu, M.; Lei, Y. Highly nitrogen doped carbon nanofibers with superior rate capability and cyclability for potassium ion batteries. Nat. Commun. 2018, 9, 1720. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, J.; Dong, K.; Zhang, Y.; Wang, X.; Aboalhassan, A.A.; Yu, J.; Ding, B. Multifunctional flexible membranes from sponge-like porous carbon nanofibers with high conductivity. Nat. Commun. 2019, 10, 5584. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, P.; Zou, L.; Hu, H.; Wang, M.; Fang, J.; Lai, Y.; Li, J. 3D hierarchical carbon microflowers decorated with MoO2 nanoparticles for lithium ion batteries. Electrochim. Acta 2017, 250, 219–227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yi, L.; Chen, J.; Shao, P.; Huang, J.; Peng, X.; Li, J.; Wang, G.; Zhang, C.; Wen, Z. Molten-salt-assisted synthesis of bismuth nanosheets for long-term continuous electrocatalytic conversion of CO2 to formate. Angew. Chemie Int. Ed. 2020, 59, 20112–20119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kozub, B.R.; Rees, N.V.; Compton, R.G. Electrochemical determination of nitrite at a bare glassy carbon electrode; why chemically modify electrodes? Sens. Actuators B: Chem. 2010, 143, 539–546. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, S.; Liu, M.; He, S.; Zhang, S.; Lv, X.; Song, H.; Han, J.; Chen, D. Protonated carbon nitride induced hierarchically ordered Fe2O3/H-C3N4/rGO architecture with enhanced electrochemical sensing of nitrite. Sens. Actuators B: Chem. 2018, 260, 490–498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lei, H.; Zhu, H.; Sun, S.; Zhu, Z.; Hao, J.; Lu, S.; Cai, Y.; Zhang, M.; Du, M. Synergistic integration of Au nanoparticles, Co-MOF and MWCNT as biosensors for sensitive detection of low-concentration nitrite, Electrochim. Acta 2021, 365, 137375. [Google Scholar]

| Electrochemical method | Spectrophotometric method | ||||||

| Samples | Added (μM) | Found (μM) | Recovery (%) |

aRSD (%) |

Found (μM) | Recovery (%) |

aRSD (%) |

| Tap water | 5.0 50.0 500.0 |

4.9 52.1 527.1 |

98.0 104.2 105.4 |

0.4 0.8 1.9 |

4.8 46.7 501.6 |

96.0 93.4 100.3 |

2.8 1.6 0.5 |

| Pickles | 5.0 50.0 500.0 |

4.9 50.5 510.5 |

98.0 101.0 102.1 |

0.5 0.8 2.1 |

5.3 49.6 508.6 |

106.0 99.2 101.7 |

2.4 1.1 0.1 |

| Sausage | 5.0 50.0 500.0 |

4.9 47.1 511.5 |

98.0 94.2 102.3 |

4.9 1.4 4.8 |

5.1 50.8 513.3 |

102.0 101.6 102.7 |

1.4 1.5 0.7 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).