1. Introduction

As the cell cycle progresses, the cell divides and this division implies the duplication of its genetic material. Thus, the cell cycle is a highly regulated process that integrates many signals coming from the membrane, as well as from cellular pathways involved in controlling the genetic integrity to ensure the absence of genetic damage. The E2F/RB pathway is key to this regulation, and in fact mutations affecting this pathway induce an aberrant cell cycle activity and are highly associated with many types of cancer. The retinoblastoma tumor suppressor protein (RB) and the other “pocket protein” members, either p107 or p130, act as tumor suppressors through their important function as regulators of proliferation, differentiation, and apoptosis. The RB family exerts its role by interacting with many proteins, with E2F transcription factors being the best-characterized binding partners of RB. Activation of cyclin/CDKs complexes phosphorylates RB family members, decreasing their ability to interact with target proteins and thus altering their biological functions. Although eight E2F family members have been identified in mammals, only E2F1-6 have both a conserved DNA-binding domain and a dimerization domain, with E2F1-3 also containing an RB-binding sequence near the C-terminus [

1]. Despite the sequence similarities among the Rb family members, RB preferentially binds to E2F1-4, this fact accounts for the fact that only RB mutations are frequently detected in cancers. In recent years, several reports have demonstrated that the E2F/RB pathway is regulated by independent cell cycle regulators including members of the poly(ADP-ribose) polymerase gene family. Currently, of the 17 identified members of the poly(ADP)-ribose) polymerase (PARP) family, most are enzymes capable of attaching poly(ADP-ribose) units to proteins or DNA using NAD

+ as a substrate [

2]. Although PARP proteins have been classically implicated in DNA repair, several important functions have recently been identified, including cell division and transcriptional regulation. PARP1 regulates gene expression by various mechanisms, either through physical and direct functional interactions with chromatin, or by regulating the activity of chromatin regulating enzymes and transcriptional co-regulators [

3,

4,

5,

6].

Among these, PARP1 is known to alter gene expression by acting as either a co-activator or a co-repressor of transcription in a promoter-specific manner independent of its catalytic activity. Indeed, PARP1 can upregulate the transcriptional activity of E2F1 through its function as a co-activator during the re-entry of quiescent cells into S phase [

7,

8]. Recently, we have shown how PARP1 regulates the E2F1 transcriptional function through their interaction [

9]. Here, we show how this transcriptional modulation can be affected by pharmacological treatment with PARP1-interacting molecules.

3. Discussion

Functional inactivity of the tumor suppressor pRB present in various tumor types and transgenic animal models, leads to dysregulation of E2F1 transcriptional activity, which correlates with aberrant cell proliferation and, in some cases, with cell death [

27,

28,

29]). The effects of Rb deficiency, or hyperactivation of E2F1, have been extensively studied both in relation to the initiation of the oncogenic process [

10,

30,

31], and the induction of embryonic lethality in mice [

32,

33].

Based on studies by Simbulan-Rosenthal [

7,

8] and previous results from our group [

9], we have shown that the PARP1 protein plays an important role in the transcriptional activity of E2F1 by modulating it at the G1/S transition. This modulation of E2F1 occurs through the direct interaction of both proteins and that in the case of PARP1 takes place through the central domain or self-modification which contains a BRCT motif like other proteins that interact with E2F1. In studies published by our group and others [

8,

9], it has been demonstrated that the association of PARP1 and E2F1 occurs directly on the promoter of E2F1 and other transcriptional targets of E2F1 such as cyclin A. Similarly, we also observed that the hyperactivation of E2F1 transcriptional activity in pRb-deficient cells can be reduced if PARP1 is also absent, confirming the role of this protein as a co-activator of E2F1 [

9].

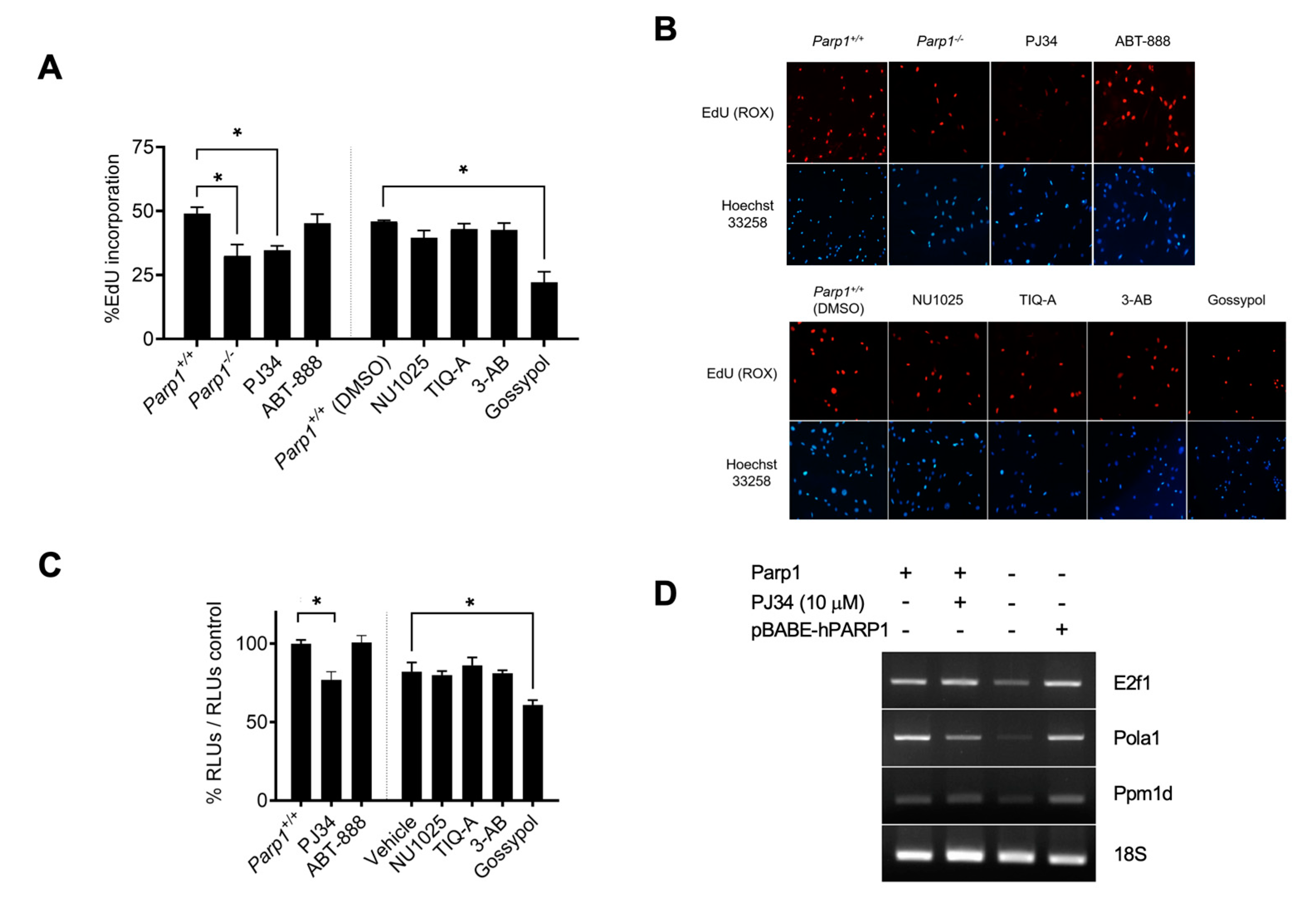

Although this interaction does not seem to depend on the enzymatic activity of PARP1, since E2F1 is not poly(ADP-ribosyl)ated in vitro, we observed that treatment with an inhibitor reduces de the expression of some E2F1 transcriptional targets involved in the transition between low- and high-grade gliomas, such as POLA1 polymerase or WIP-1 phosphatase, in MEFs synchronized by serodeprivation [

19,

25]. Interestingly, a similar effect was observed when cells treated PJ34, a inhibitor of PARP1 enzymatic activity, and with gossypol, a molecule capable of specifically blocking the protein-protein interactions mediated by the BRCT motif of PARP1 [

16].

Gossypol is a naturally occurring compound usually obtained as a racemic mixture of two stereoisomers of which only the (-)-gossypol isomer has the ability to interfere with PARP1 protein-protein interactions. Mechanistically, this biological activity translates into the ability of this molecule to react to form a Schiff base by reacting its two aldehyde functional groups with the amino groups of lysines 438 and 441 of the BRCT domain, thus blocking any possible interaction between PARP1 and other proteins.

In the case of PJ34, this molecule lacks aldehyde groups that allow a gossypol-like interaction with the BRCT domain of PARP1. As is well known, this inhibitor developed by Inotek [

34], like many other PARP1 inhibitors, takes nicotinamide (NAM) as a structural model to bind to its binding site in the enzyme's catalytic center and block its activity. In addition to binding to the NAM pocket, this molecule can locate itself between the α-helix and the D-loop of tankyrase-1 (PARP-5a), both structural motifs that are also present in the domains of PARP1 catalytic agents, suggesting that, like PARP-5a, it is capable of binding two PJ34 molecules simultaneously at both binding sites [

35].

In relation to these results, the assays with the EGFP-PARP1 and RFP-E2F1 fusion proteins not only confirm that the co-localization of PARP1 and E2F1 increases with time from the G1 to S phase, but in the case of cells treated with PJ34, the levels of the RFP-E2F1 fusion protein appear to decrease significantly. As seen below, in the same synchronized cells, whose protein translation had been inhibited by cycloheximide treatment, E2F1 levels decreased more sharply over time in the case of PJ34, suggesting that this inhibitor may affect the stability of E2F1.

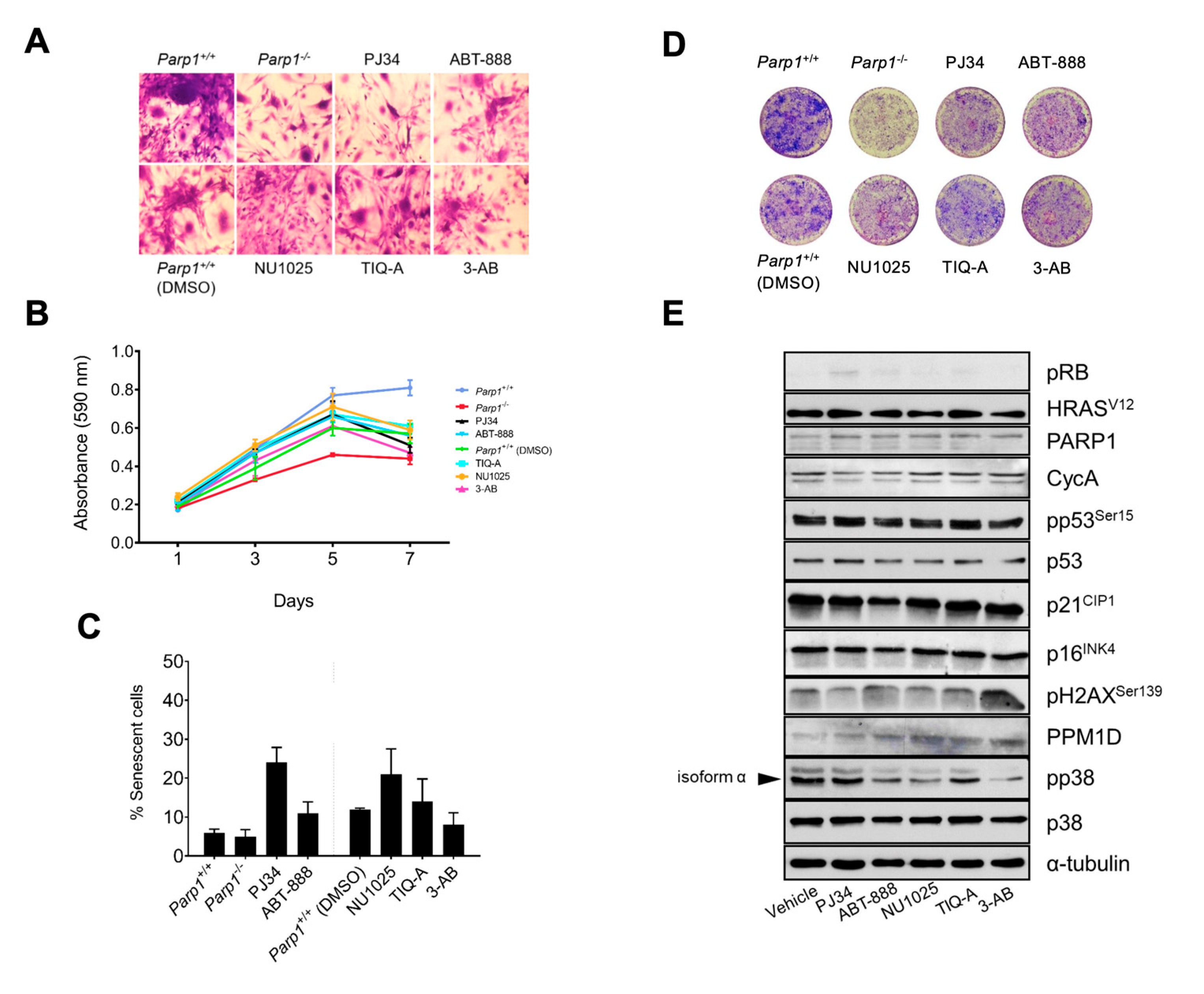

Finally, we wanted to test whether this cooperation between both proteins also extends to an oncogenic context, which would allow us to modulate the activity of E2F1 by inhibiting PARP1. To do this, we used a model of gliomagenesis already characterized by our group, which is largely based on the hyperactivation of E2F1 by conditional deletion of pRb [

19]. As in non-transformed cells, PARP1 inhibition leads to reduced proliferation, in addition to the reduction of aggressiveness and cell transformation observed in control cells (

Parp1+/+ cRb-/-HRas

V12), especially in the case of PJ34. However, we also observed that in the case of cells treated with PJ34, the percentage of senescent cells in the culture increased (

Figure 3C), which would also explain the lower proliferation rate of astrocytes treated with this inhibitor, in addition to the generation of fewer foci or colonies compared to untreated control astrocytes (

Figure 3D). Consistent with this, the biochemical analysis shows an increase in the levels of the cycle inhibitor p21CIP as well as of phosphorylated p53 in the case of the group treated with PJ34, which would explain the increase in senescent cells observed in this group. Regarding this result, it is important to consider that PJ34, like the rest of the inhibitors used, may have some off-target or non-specific effects that could confound the results obtained. A review of the available literature shows that PJ34, in addition to presenting a high affinity for the catalytic centers of PARP1 and PARP-2, as expected since they are the ones with the greatest homology to each other, is also capable of binding to several members of its family (PARP-3, -4, -5a, -5b, -14, -16) [

36], as well as the metalloprotease MMP-2 and the kinases PIM1 and PIM2, albeit with lower avidity [

37]. Despite the apparent redundancy of the biological functions of the different PARPs, especially PARP1 and PARP-2, more and more specific functions are being discovered for these proteins [

15,

38,

39]. Therefore, it is logical to speculate that the combined inhibition of multiple members of this family may have more durable and/or profound effects than the deletion of PARP1 alone and thus explain these differences between

Parp1-/- cRb-/- HRas

V12 and

Parp1+/+ cRb-/- HRas

V12 treated with PJ34.

Also noteworthy, although expected, is the decrease in PPM1D (Wip1) and cyclin A levels in this group and in

Parp1-/- cRb-/- HRas

V12 cells, since both proteins are transcriptional targets of E2F1 itself. 1. Interestingly, the levels of p38-α kinase (MAPK14) were also increased in the case of PJ34 treatment in contrast to control cells. As we have already observed in previous studies in our laboratory, the level of oncogenesis-induced senescence (OIS) in

cRb-/- HRas

V12 astrocytes is closely related to the activity of the p38-α-specific phosphatase, Wip1. This phosphatase, once inactivated, allows p38 to activate and act as a brake on tumorigenesis by forcing astrocytes to slow down their proliferation and enter a senescent state [

19,

25]. In the same way, by reducing the transcriptional activity of E2F1, we also reduce the levels of Wip1 and therefore the proliferation of these cells that lack the protection of this phosphatase are affected by senescence mediated by oncogenes, and that in our case is HRas

V12.

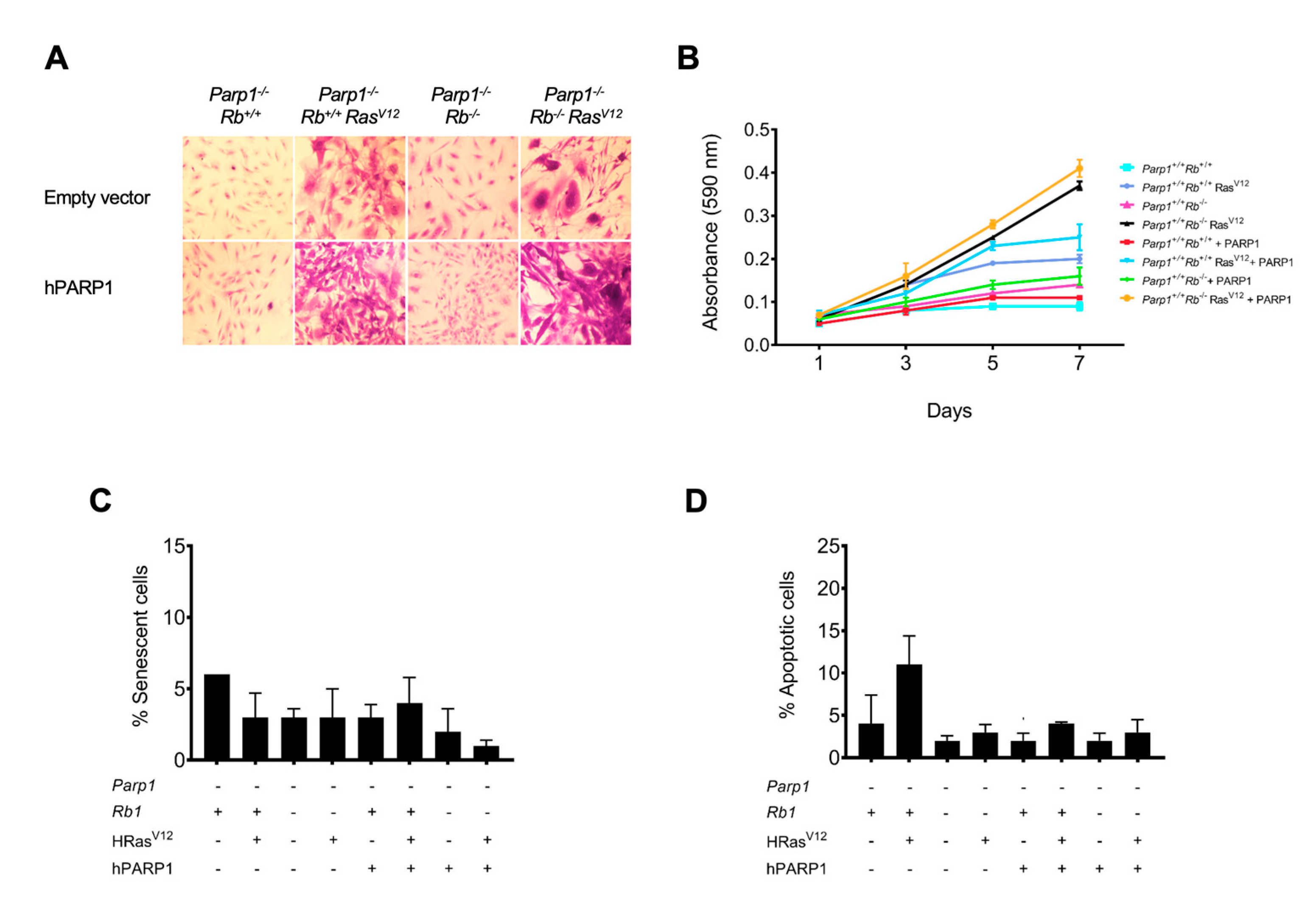

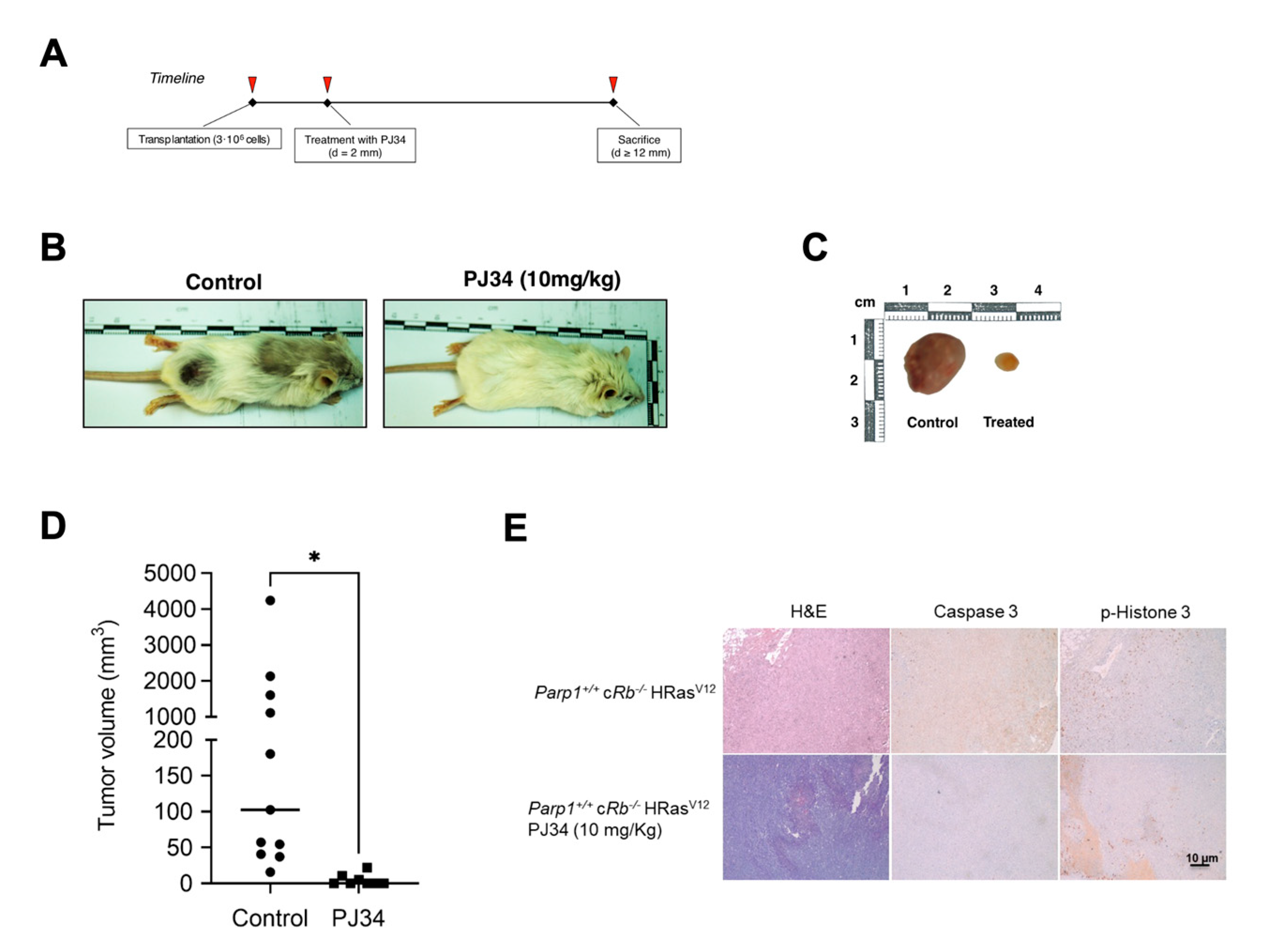

To complement these results, we wanted to verify once again that the absence of PARP1 is responsible for the change in phenotype and aggressiveness of our astrocytes. In the results that we have presented previously, it can be clearly observed that the reintroduction of a copy of PARP1 with reduced catalytic activity increases the proliferation and the degree of transformation of Parp1-/- cRb-/- HRasV12 astrocytes, whereas, as in the previous experiment, the chemical inhibition of PARP1 by means of PJ34 has an antagonistic effect. We reached the same conclusion when injecting these astrocytes into SCID mice, since Parp1-/- cRb-/- HRasV12 cells had a very tumorigenic capacity compared to controls. In turn, a single-dose treatment (10 mg/kg) of the PJ34 inhibitor was sufficient to reduce the volume of the masses obtained in the treated mice. Finally, the immunohistological analysis of these tumor tissues confirmed that in the case of treatment with PJ34, proliferation is greatly reduced, as evidenced by the low labeling of phosphorylated histone H3 compared to control tissue. In the case of Parp1-/- cRb-/- HRasV12 astrocyte tumors, the labeling of proliferating cells was also reduced, but unlike what occurred in in vitro oncogenesis studies, the levels of cell apoptosis were reduced inside the tumor.

In conclusion, in the present study we have shown that treatment with the inhibitor PJ34 or the inhibitor of protein-protein interactions gossypol can reduce the transcriptional activity of E2F1 and the proliferation of the treated cells. Inhibition of PARP1 protects the cell against oncogenic stimuli by reducing its proliferative rate, both in vivo and in vitro, or by reactivating other cell signaling pathways involved in oncogenesis-induced senescence.

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Primary Cell Cultures

Cells were maintained in Dulbecco’s modified Eagle medium (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO, USA) with 10% fetal bovine serum and 1% L-glutamine (GIBCO-Invitrogen, Waltham, MA, USA). Primary astrocytes were generated from both Parp1+/+ cRbloxP/loxP and Parp1−/− cRbloxP/loxP neonatal mice at P3. Oncogenic Ras expression and deletion of Rb was also achieved by retroviral transduction using Phoenix-Eco cells (Swift et al, 2001) transfected with pBABE, pBABE-HRasV12, PIG-puro, and PIG-CRE retroviral plasmids (a gift from P.P. Pandolfi). Transduced cells were selected by adding puromycin to the culture medium at 2 μg/mL.

4.2. PARP1 inhibition and other pharmacological treatments

The inhibitors 3-aminobenzamide (3-AB, sc-3501, Santa Cruz), NU 1025 (sc-203166, Santa Cruz), ABT-888 (sc-202901, Santa Cruz), TIQ-A (sc-204916, Santa Cruz) and PJ34 (528150, Sigma-Aldrich) were used to inhibit the catalytic activity of PARP1. In addition, an allosteric inhibitor of BRCT-mediated protein-protein interactions of PARP1, gossypol (G8761, Sigma-Aldrich), was also included in some of the experiments.

For the E2F-1 half-life assay, HEK293 cells were seeded in a 12-well multiwell plate at a density of 5-104 cells/cm2 and transfected with equimolar amounts of the pEGFP-PARP-1 (a gift from A. Chiarugi) and pRFP-E2F-1 (a gift from B. Su). After synchronisation with double-thymidine treatment, cells were released with fresh DMEM medium along with the treatments (PJ34 and gossypol) and their respective controls plus cycloheximide (C7698, Sigma-Aldrich) at a final concentration of 35 µM.

4.3. Co-localization studies

For co-localization studies, 5 × 104 per cm2 HEK293 cells were seeded on EZ-multiwell slides (Millipore, Burlington, MA, USA). Cells were transfected using equimolar quantities of pEGFP-PARP1 (a gift from A. Chiarugi) and pRFP-E2F1 (a gift from B. Su) and synchronized by double thymidine treatment. Upon release from cell cycle block, cells were fixed with 2% paraformaldehyde (pH 7.4) and nuclei were counterstained using DAPI (Invitrogen, Waltham, MA, USA) and fluorescent images from three independent experiments were taken using a Leica TCS SP2 microscope.

4.4. Incorporation of 5-Ethynyl-2’-Deoxyuridine (EdU)

Mouse fibroblasts were seeded at 5000 cells per cm2 in 24-well plates. Culture medium was removed twenty-four hours later and replaced with low-serum medium (0.5% FCS). After 48 h, the starvation medium was replaced with high-serum medium (15% FCS) along with PARP1 inhibitors for 16 h and subsequently treated with 10 μM 5-ethynyl-2’-deoxyuridine (EdU) (Sigma-Aldrich) for two additional hours. Nuclei were stained using Hoechst 3358 (Sigma-Aldrich) and fluorescence images were collected from three different experiments.

4.5. Luciferase Assays

MEF were seeded in 12-well plates at 2500 cells per cm2. Cells were subsequently transfected with vectors pE2F-Luc (a gift from M. Collado) and pCMV-β-Gal (Clontech, Mountain View, CA, USA). The data from three independent experiments were normalized using beta-galactosidase activity.

4.6. Animal Studies

Xenografts were established in SCID (Severe Combined Immunodeficiency) mice aged 10 to 12 weeks. Cell implantation was carried out by subcutaneous injection in the hindquarters with 3 × 106 transduced astrocytes resuspended in 100 µL PBS 1×. Treatment with PJ34 (Sigma-Aldrich) was initiated once the tumor reached a minimum diameter of 2 mm with a single-dose of 10 mg/kg, injected intraperitoneally. Control animals were injected PBS in similar manner. All tumors included in the analysis reached a minimum diameter of 4 mm and mice were euthanized when they approached a maximum diameter of 12 mm. Tumors were considered ellipsoid in shape and their volume was calculated using the equation volume = 0.5 × (length × width) [

40]. The conditional mouse strain for

Rb1 [

41], was obtained from the Mouse Models of Human Cancer Consortium (MMHHC) repository.

Parp1−/− strain [

42] was a gift from Prof. de Murcia. All animal procedures were approved and performed according to the guidelines set out by the Institutional Ethics Committee for Animal Experimentation.

4.7. Immunoblot

Analysis of protein levels was carried out by immunoblot analysis of whole cell lysates using polyclonal antibodies against PARP1 (H-300, Santa Cruz), cyclin A (C-19, Santa Cruz), p53 (CM5, Novocastra), p-p53 ser15 (9284, Cell Signaling), p38 (C-20, Santa Cruz), p-p38 (Thr180/Tyr182) (sc-17852, Santa Cruz), p16 (M-156, Santa Cruz), p-H2AX Ser139 (07-164 Upstate), p21 (M-19, Santa Cruz), PPM1D/WIP1 (H-300, Santa Cruz) and E2F-1 (C-20, Santa Cruz), as well as monoclonal antibodies against pan-Ras-V12 (Ab-1, Calbiochem), cyclin D1 (DCS6, Cell Signaling), α-tubulin (T5168, Sigma-Aldrich), β-actin (MAB1501, Millipore), and Rb (554136, BD).

4.8. Immunohistochemistry

Analysis of fetal erythrocytes from cord blood samples was carried out by Wright-Giemsa staining. For immunohistochemical analysis, anti-cleaved caspase 3 (monoclonal, Cell Signaling) and phospho-histone H3 (polyclonal, Cell Signaling Technology, Inc) were used as primary antibodies. Immunohistochemical analysis was performed using a universal second antibody kit that uses a peroxidase-conjugated labelled dextran polymer (Envision Plus, Dako, Glostrup, Denmark). The following primary antibodies were used: anti-cleaved caspase 3 (monoclonal, Cell Signaling Technology, Inc) and phospho-histone H3 (polyclonal, Cell Signaling Technology, Inc).

4.9. Semiquantitative RT-PCR

Embryonic fibroblasts were seeded at a rate of 4-104 cells/cm2 in 10 cm plates and synchronized for 44 hours serodeprivation. Cells were released from arrest and left in factor-rich medium (DMEM 15% FBS) for 16 hours before RNA extraction. After obtaining the cDNA, specific sequences of each gene were amplified using the following oligonucleotide pairs: qE2F1-F 5’ CTCGACTCCTCGCAGATCG 3’, qE2F1-R 5’ AGCTCGGCGAGAAAAGAAATC3’, qPOLA1-F 5’ GAAGAACGAGATCAGCAG 3’, qPOLA1-R 5’ CCACATAGCCTATCCCATCGTC 3’, qWIP1-F 5’ GATGTATGTAGCGCATGTAGGTG 3’, qWIP1-R 5’ GTTCTGGCTTGTGATCTTGTGT 3’, 18S-F 5’ TTGACGGAAGGGCACCACCAG 3’, 18S-R 5’ CTCCTTAATGTCACGCACGATTTC 3’.

4.10. Statistics

Statistical analysis was performed with ANOVA and Student’s t-test for multiple or simple comparisons, respectively. Tukey and Student–Neumel–Kaus tests were used for post-hoc analysis of ANOVA results. Mantel–Cox test was used to analyze Kaplan–Meier curves. In all cases, statistical significance was established at p < 0.05.

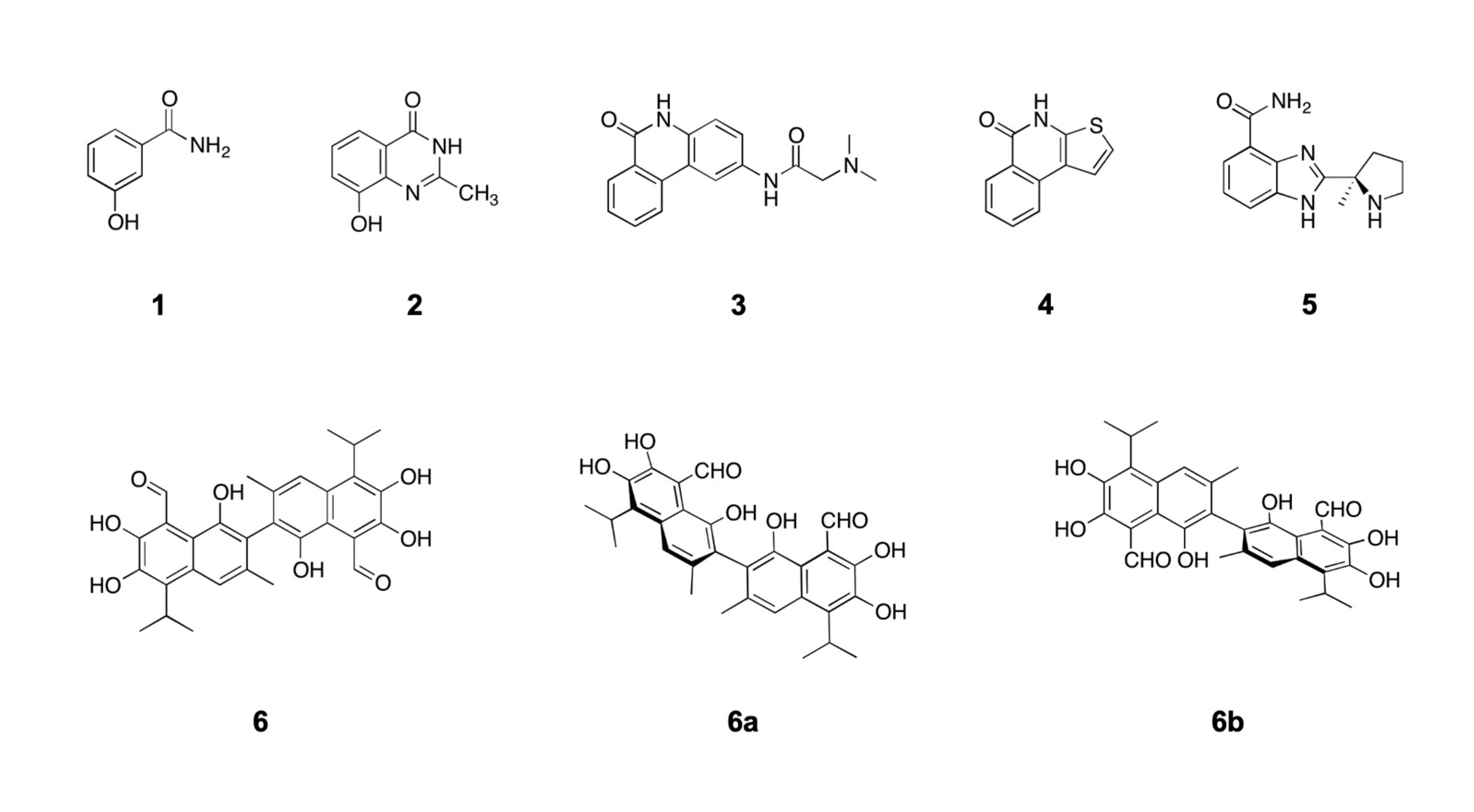

Figure 1.

Structure of PARP1 inhibitors and gossypol, an inhibitor of PARP1 protein-protein interactions. Compound 1, 3-aminobenzamide; Compound 2, NU1025; Compound 3, PJ34; Compound 4, TiQ-A; Compound 5, ABT-888; Compound 6, gossypol. Gossypol was obtained from its natural source (cotton) as a racemic mixture of two atropisomers where the (-)-gossypol isomer (6a) specifically interferes with PARP1 protein-protein interactions.

Figure 1.

Structure of PARP1 inhibitors and gossypol, an inhibitor of PARP1 protein-protein interactions. Compound 1, 3-aminobenzamide; Compound 2, NU1025; Compound 3, PJ34; Compound 4, TiQ-A; Compound 5, ABT-888; Compound 6, gossypol. Gossypol was obtained from its natural source (cotton) as a racemic mixture of two atropisomers where the (-)-gossypol isomer (6a) specifically interferes with PARP1 protein-protein interactions.

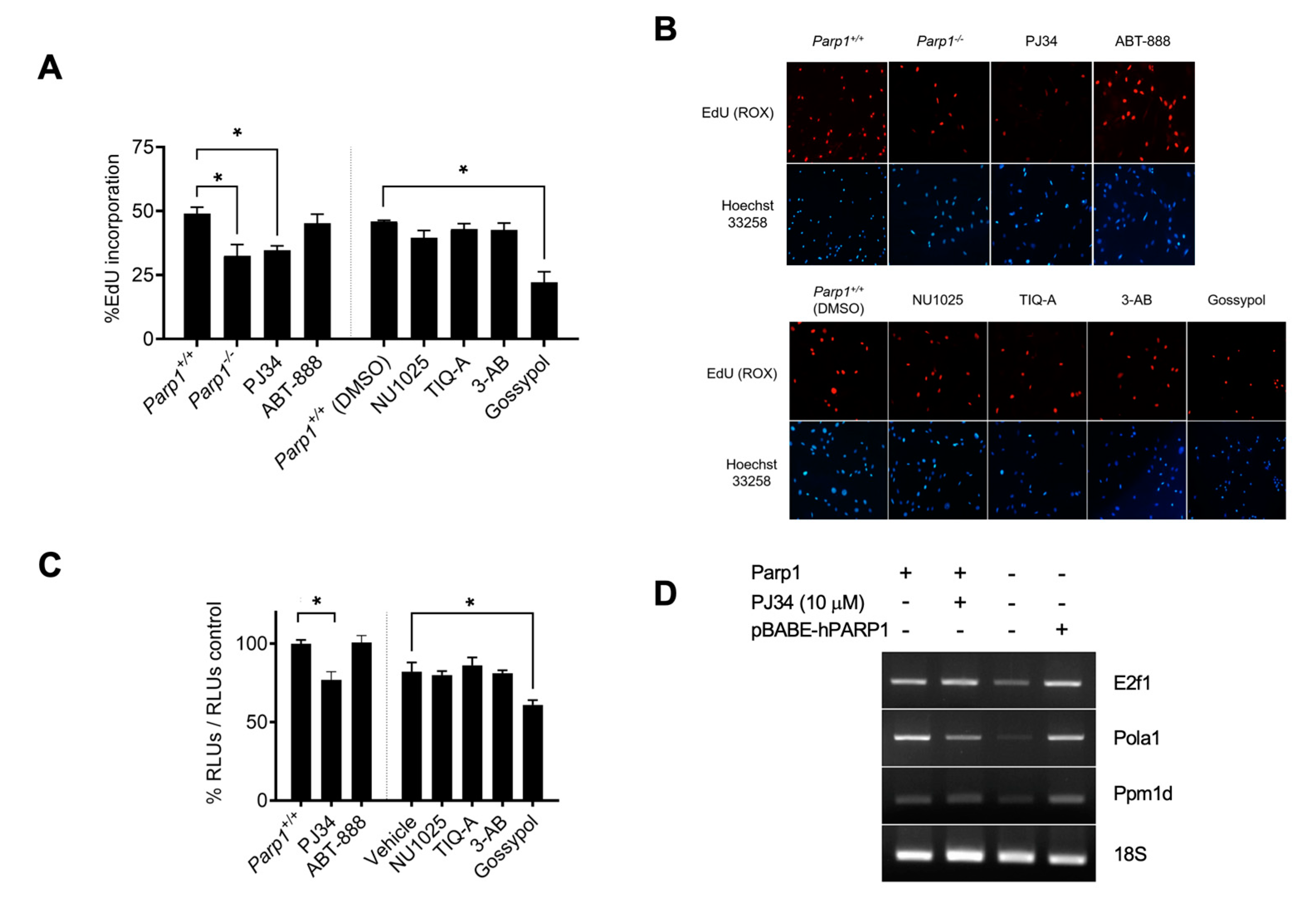

Figure 2.

Effects of PARP1 inhibition on E2F1 transcriptional activity. A, EdU incorporation assay in MEF treated with the PARP1 inhibitors PJ34 (10 µM), ABT-888 (10 µM), NU1025 (100 µM), TIQ-A (50 µM), 3-AB (5 mM) and gossypol (25 µM). A vertical line separates cells treated with inhibitors dissolved in water and inhibitors dissolved in DMSO (*=p<0.01). B, representative images of results presented in panel A. Cell nuclei were counterstained with Hoechst 33258 (bisbenzimide). C, luciferase activity assay in HEK293 transfected with E2F-Luc plasmid treated with PARP-1 inhibitors. A vertical line separates cells treated with inhibitors dissolved in water and inhibitors dissolved in DMSO. Cells were synchronised prior to treatment, and results were normalized to its corresponding vehicle (water or DMSO). Shown is a representative experiment of three independent replicates (*=p<0.01) D, semiquantitative RT-PCR of E2F1 transcriptional targets. Results are representative from three independent experiment replicates.

Figure 2.

Effects of PARP1 inhibition on E2F1 transcriptional activity. A, EdU incorporation assay in MEF treated with the PARP1 inhibitors PJ34 (10 µM), ABT-888 (10 µM), NU1025 (100 µM), TIQ-A (50 µM), 3-AB (5 mM) and gossypol (25 µM). A vertical line separates cells treated with inhibitors dissolved in water and inhibitors dissolved in DMSO (*=p<0.01). B, representative images of results presented in panel A. Cell nuclei were counterstained with Hoechst 33258 (bisbenzimide). C, luciferase activity assay in HEK293 transfected with E2F-Luc plasmid treated with PARP-1 inhibitors. A vertical line separates cells treated with inhibitors dissolved in water and inhibitors dissolved in DMSO. Cells were synchronised prior to treatment, and results were normalized to its corresponding vehicle (water or DMSO). Shown is a representative experiment of three independent replicates (*=p<0.01) D, semiquantitative RT-PCR of E2F1 transcriptional targets. Results are representative from three independent experiment replicates.

Figure 3.

Effect of PARP1 inhibitors on primary astrocytes. Postnatal-day-3 astrocytes obtained from Parp1-/- cRb-/- HRasV12 or Parp1 +/+ cRb-/- HRasV12 mice were treated in vitro with PARP1 inhibitors. A, morphological changes in cells stained with crystal violet. B, proliferation rate. Cells were stained with crystal violet, and cell number was determined by spectrophotometry. C, percent of senescent cells, obtained by quantification of SA-β-galactosidase activity. D, colony formation. Astrocytes were fixed with methanol-acetic acid (3;1, v/v) and stained with 0.1% (w/v) crystal violet in PBS on day 7 of culture. D, biochemical analysis of the main checkpoints of the DNA damage response (DDR) as well as transcriptional targets of E2F1. All results are representative of, at least, three independent experiments.

Figure 3.

Effect of PARP1 inhibitors on primary astrocytes. Postnatal-day-3 astrocytes obtained from Parp1-/- cRb-/- HRasV12 or Parp1 +/+ cRb-/- HRasV12 mice were treated in vitro with PARP1 inhibitors. A, morphological changes in cells stained with crystal violet. B, proliferation rate. Cells were stained with crystal violet, and cell number was determined by spectrophotometry. C, percent of senescent cells, obtained by quantification of SA-β-galactosidase activity. D, colony formation. Astrocytes were fixed with methanol-acetic acid (3;1, v/v) and stained with 0.1% (w/v) crystal violet in PBS on day 7 of culture. D, biochemical analysis of the main checkpoints of the DNA damage response (DDR) as well as transcriptional targets of E2F1. All results are representative of, at least, three independent experiments.

Figure 4.

Effect of partially restoring of PARP1 catalytic activity. Primary astrocytes obtained from Parp1-/- cRbflox/flox, Parp1-/- cRbflox/flox HRasV12, Parp1-/- cRb-/- , or Parp1-/- cRb-/-HRasV12 mice were transduced with a copy of hPARP1 with reduced catalytic activity. A, morphological changes in cells stained with crystal violet. B, proliferation rate. Cells were stained with crystal violet, and cell number was determined by spectrophotometry. C, percent of senescent cells, obtained by quantification of SA-β-galactosidase activity. D, percent of apoptotic cells. Apoptotic nuclei were stained with Hoechst 33258. All results are representative of, at least, three independent experiments.

Figure 4.

Effect of partially restoring of PARP1 catalytic activity. Primary astrocytes obtained from Parp1-/- cRbflox/flox, Parp1-/- cRbflox/flox HRasV12, Parp1-/- cRb-/- , or Parp1-/- cRb-/-HRasV12 mice were transduced with a copy of hPARP1 with reduced catalytic activity. A, morphological changes in cells stained with crystal violet. B, proliferation rate. Cells were stained with crystal violet, and cell number was determined by spectrophotometry. C, percent of senescent cells, obtained by quantification of SA-β-galactosidase activity. D, percent of apoptotic cells. Apoptotic nuclei were stained with Hoechst 33258. All results are representative of, at least, three independent experiments.

Figure 5.

Effect of PARP-1 inhibition in vivo. A, timeline of the in vivo transformation assay. B, Effect of PJ34 on tumoral growth. Parp1+/+ cRb-/- HRasV12 mice were injected subcutaneously with 3-106 astrocytes and treated with vehicle (control) or PJ34 (10 mg/kg). C, tumor volume in control (n=11) or PJ34-treated (n=8) mice (*=p<0.05). D, representative images or results presented in panel B. D, Caspase 3 and p-histone 3 expression in tumors obtained from control or PJ34-treated (n=8) mice.

Figure 5.

Effect of PARP-1 inhibition in vivo. A, timeline of the in vivo transformation assay. B, Effect of PJ34 on tumoral growth. Parp1+/+ cRb-/- HRasV12 mice were injected subcutaneously with 3-106 astrocytes and treated with vehicle (control) or PJ34 (10 mg/kg). C, tumor volume in control (n=11) or PJ34-treated (n=8) mice (*=p<0.05). D, representative images or results presented in panel B. D, Caspase 3 and p-histone 3 expression in tumors obtained from control or PJ34-treated (n=8) mice.