1. Introduction

With climate change threatening the future of our environment and society, implementing immediate and effective strategies to curb Greenhouse Gas (GHG) emissions is the need of the hour. The transportation sector is one of the guiltiest parties, accounting for 35% of the worldwide energy consumption [

1]. Road vehicles, especially passenger cars and road freight transport vehicles, account for 86% of the global share [

2].

Along with GHG emissions, road congestion is a current problem for transport policy at all levels. According to Joint Research Centre (JRC), the cost of road congestion in Europe is estimated to be over €110 billion a year [

3]. Not to mention the dramatic effects that traffic has on the increased air pollution [

4] and environmental noise [

5]. Despite allowing competing flows of traffic to safely cross busy intersections, traffic signals lead to increased congestion in urban areas.

In this framework, global regulatory targets and customer demand are pushing the automotive industry to develop vehicles with improved fuel economy to curb GHG emissions [

6]. On the other hand, integrated with the feasible technical solutions aimed at improving the efficiency of current propulsion systems [

7], the adoption of Connected and Automated Vehicles (CAVs) could lead, in the next decade, to a major technological revolution in the mobility sector. The benefits of mass adoption of CAVs can range from enhanced road safety [

8], improved traffic handling [

9], and reduced fuel consumption [

10]. Moreover, creating systems in which information and communication technologies can be easily exchanged, namely Intelligent Transportation Systems (ITS) [

11], can also have a beneficial effect on reducing congestion in urban areas. Connected vehicles, featuring Vehicle-to-Vehicle (V2V) and Vehicle-to-Infrastructure (V2I) technologies [

12], can have access to the Signal Phase and Timing (SPaT) of traffic lights. This information can be directly transmitted to vehicles through a Dedicated Short Range Communications (DSRC) technology [

13] or may become available by the traffic control center through cellular and Wi-Fi networks, namely Cellular Vehicle-to-Everything (C-V2X) [

14]. The C-V2X potentiality could be further boosted by a possible coupling with the new 5G mobile network [

15] or a joint use of DSRC and C-V2X communications [

16]. Alternatively, several studies have demonstrated that SPaT information may be inferred via on-board cameras [

16] and via crowdsourcing [

17].

Traditional approaches focused more on signal control methods to enhance traffic flow at signalized intersections, such as signal timing optimization [

9], or actuated signals application in real-world traffic [

18] that could allow to smooth traffic oscillations and decrease vehicle waiting times at intersections. However, with the recent advances in ITS technology, it is also possible to focus on vehicle control, i.e., using V2V and V2I communications to develop eco-driving algorithms. Authors in [

19] demonstrated how upcoming traffic signal information can be used by a vehicle’s adaptive cruise control system to reduce idle time at traffic lights and fuel consumption, while [

20] introduced a novel software for detecting and predicting the SPaT to enable a Green Light Optimal Speed Advisory (GLOSA) system: i.e., a speed corrector to avoid unnecessary halts at traffic lights. [

21] takes into account also the performance degradation of the GLOSA system due to queuing effects and actual tracking driver errors, while [

22] introduces the uncertainties of SPaT information due to varying patterns of traffic lights. In the literature, several other applications of eco-driving optimization have been shown: [

23] proposes an algorithm to jointly adjust vehicle speeds at intersections and signal timings, while [

24] proposes a dynamic eco-driving system for signalized corridors based on an arterial velocity planning algorithm. [

24] also assesses the effect of different penetration rates of their algorithm through a sensitivity analysis. Finally, [

25] assesses the benefits of incorporating near-term technologies in a predictive management strategy.

From the powertrain control point of view, the increasing adoption of connected vehicles can allow for simultaneously optimizing powertrain control and velocity profile. Several studies have explored methods for optimizing the vehicle velocity profile for Battery Electric Vehicles (BEVs) as well as for Internal Combustion Engine Vehicles (ICEVs). In [

26], Dynamic Programming (DP) is used to optimize the velocity of a BEV, while in [

27] the fuel consumption reduction of a DP-based algorithm is assessed on a heavy-duty ICEV. However, Hybrid Electric Vehicles (HEVs) and plug-in Hybrid Electric Vehicles (pHEVs) can benefit the most from embedding them in an ITS, since the information from the surrounding environment can be used to optimize their control strategies [

28] [

29]. Vehicle-to-Everything (V2X) communication along with cloud computing adoption [

30] may enable a change of paradigm of the energy management problem: from an instantaneous optimization to globally minimizing it over the entire driver route [

31]. In many studies, DP is used for obtaining the optimal solution, but the heavy computation burden of this strategy has made its use largely limited to obtaining an offline performance benchmark. Suitable simplifications to the problem can make the DP real-time implementable, as shown in [

32], or the optimization problem can be solved in a remote and/or distributed cloud computing environment [

33]. Alternatively, in [

34], the optimal solutions provided by DP are used to train Recurrent Neural Networks (RNNs) in improving the energy management of a pHEV.

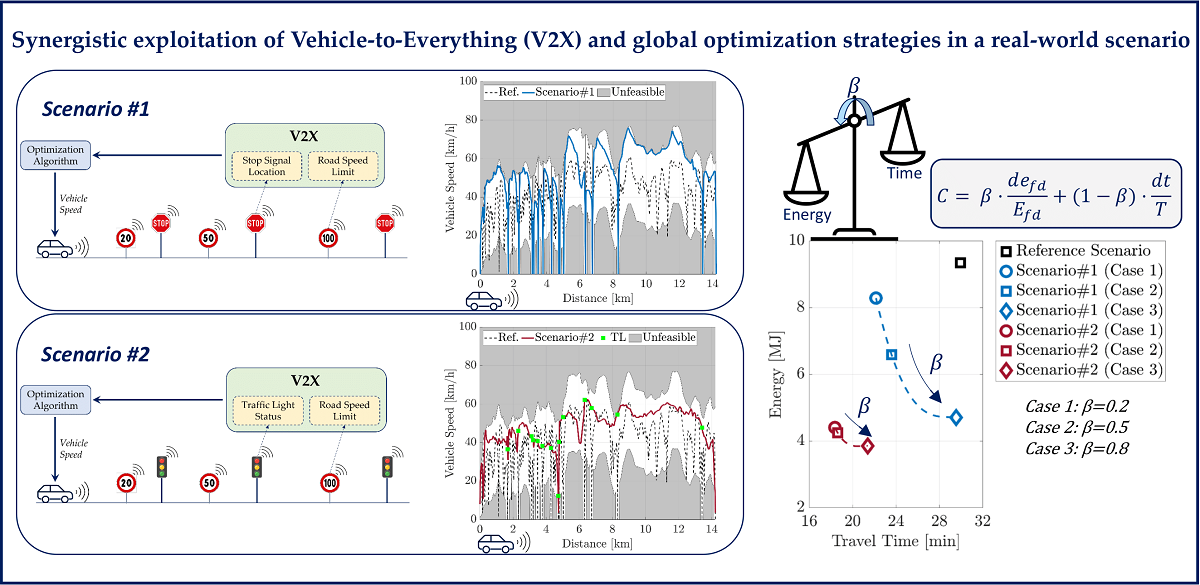

In this framework, this work aims to assess the benefits that the introduction of V2V and V2I communication, integrated with cloud computing, can have in a real-world route in terms of energy and time savings. The reference scenario is a pre-defined Real Driving Emissions (RDE) compliant route [

35], while the simulation scenarios are generated by assuming two different levels of penetration of V2X technologies. DP is used to solve the associated energy minimization problem, where the optimization framework includes information coming from the surrounding environment, e.g., traffic lights state, speed limits, distance to travel, etc. The simulations show that introducing a smart infrastructure along with optimizing the vehicle speed in a real-world urban route can potentially reduce the required energy by 54% while shortening the travel time by 38%. The results of the proposed analysis must be considered as a benchmark since the simulations are carried out for a simplified urban traffic network with vehicles in almost free flow, i.e., no direct constraints related to preceding vehicles. However, it can be conceptually extended to the case of multiple vehicles equipped with the proposed algorithm.

The rest of the paper is organized as follows. In

Section 2 the simulation scenarios are introduced along with the description of the virtual test rig used for the simulations. Then, the eco-driving optimization problem is formulated in

Section 3. In

Section 4, the results of the optimization algorithm are shown in the two different scenarios. In

Section 5, conclusions are summarized and further studies are provided.

3. Eco-Driving Optimization

In this section, the algorithm for eco-driving is introduced. It takes advantage of V2X communications and is designed for a simplified urban traffic network with vehicles in free flow, i.e., no direct constraints related to preceding vehicles. V2X information can be used to improve the energy efficiency of a vehicle at two different levels:

This work focuses only on the second stage, i.e., eco-driving. The eco-driving problem can be formalized as an optimal control problem, where the optimizer can access both the vehicle’s GPS coordinates (e.g., total trip length, road grade, and speed limits) and V2X information (e.g., SPaT, traffic conditions). Since the position of all the route features varies in a time-based perspective but remains fixed in a distance-based one, it is beneficial to express the model equations in distance-based coordinates: distance (instead of time) becomes the independent variable.

3.1. Optimal Control Problem

In the following, a formulation of the eco-driving problem in distance-based coordinates is proposed:

Where

J is the cost function,

is the vector of the state variable,

is the vector of the control variables,

d is the distance variable,

is the instantaneous cost function, and

is the terminal cost. The cost function is minimized by choosing, in the distance interval

the optimal control law

that leads to the minimization of the cost function. The cost function defined in Equation (

1) is subject to the following constraints:

Where

denotes a generic instantaneous constraint, while

and

are the admissible control and state ranges. Since the main objective of the optimization is to minimize the required energy along with the travel time, the cost function was defined according to the following:

Where

and

t denote, respectively the energy and time demand at the single distance step, while

and

T denote, respectively, the energy and time demand along the entire cycle.

is a calibration factor that can be used to trade-off between the vehicle energy demand and the traveling time. The constraints for the specific problem concern the physical limitations of the actuators (maximum deliverable power) and of the road infrastructure, e.g., speed limits and traffic lights stop. Moreover, limits regarding the maximum acceleration and deceleration values were imposed to enhance the driver’s comfort in the vehicle. As described in

Table 2, in Scenario #1 the vehicle speed is the only state variable and vehicle acceleration is the only control one. As for Scenario #2, since the SPaT is time-dependent, the time must be added as a state variable increasing the computational burden. Dynamic Programming (DP) [

41] was used by the Authors to solve the constrained optimal control problem. The open-source MATLAB code developed at ETH-Zurich [

42] was used for solving the optimal control problem.

3.2. Variable State Search Grid

DP was first introduced by R. Bellman in 1957 and is based on the concept of breaking up sequential decision problems into a finite number of manageable problems wherein the combination of their solutions leads to the global optimal solution of the entire problem. As already reported in [

43], the Achilles heel of discrete DP is the “curse of dimensionality”: in n-dimensional state and m-dimensional control spaces, the number of discrete grid points rises exponentially with the dimensions of n and m [

44]. Different techniques could be adopted to reduce the computational time required for finding the most energy-efficient path [

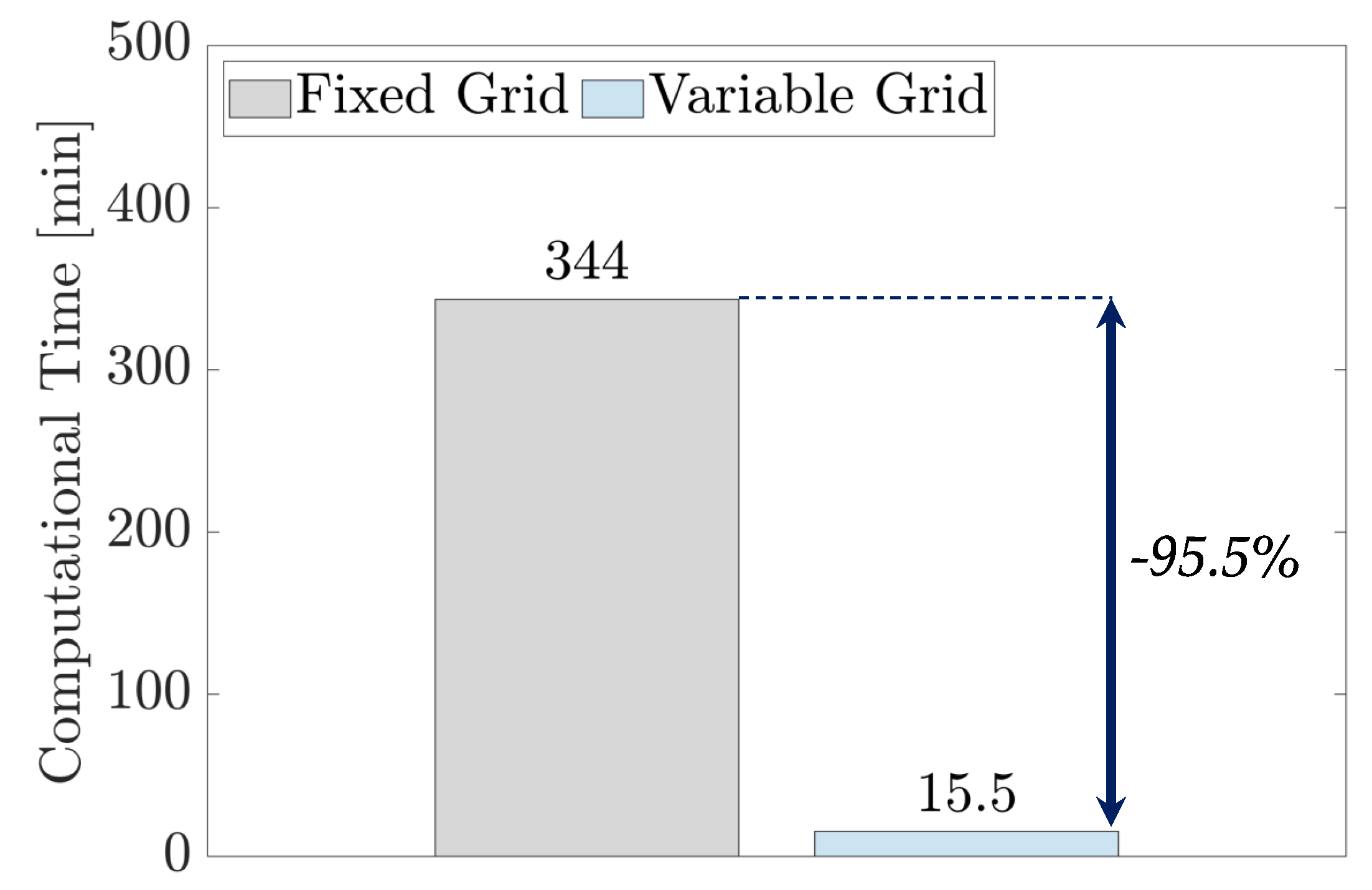

45]. In order to reduce the computational time, in this work, a variable state search grid was introduced. As shown in

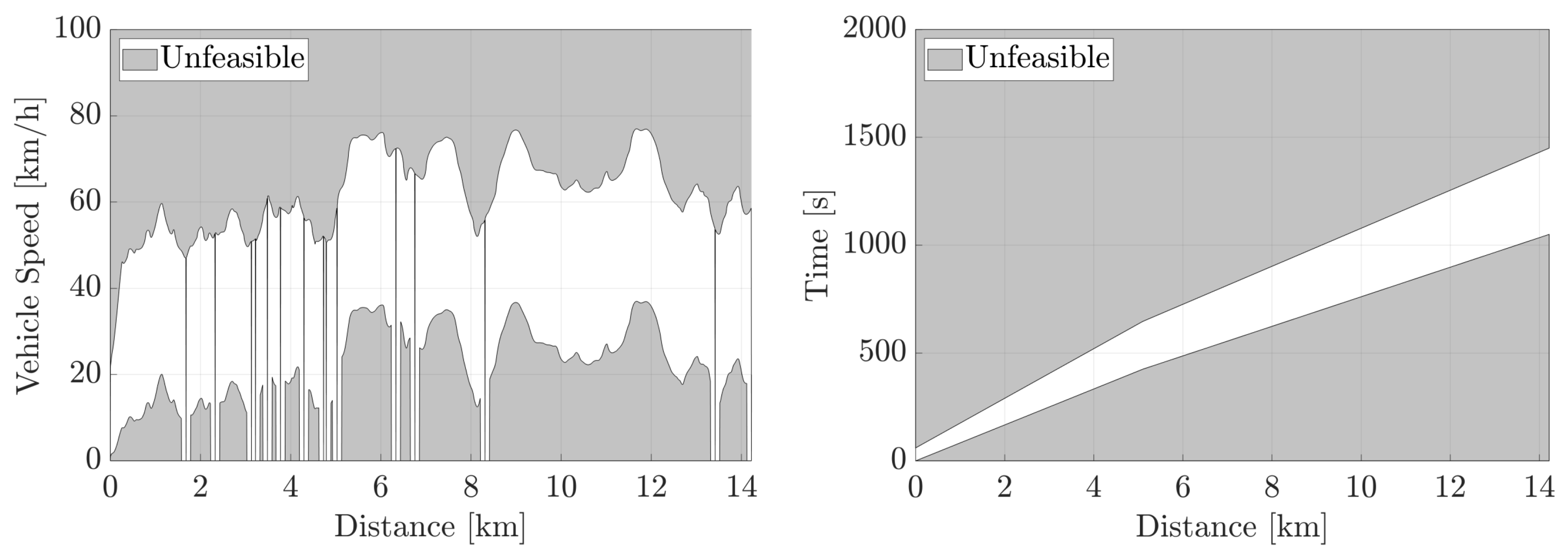

Figure 6, this artifice is particularly relevant for Scenario #2 (two control variables) allowing a reduction in the computational time of more than 95%. The computational times here shown refer to a workstation with the following specifications: Intel(R) Xeon(R) CPU E5-2680 v3 @ 2.50GHz, 64 GB RAM.

Figure 7 shows the definition of the variable grid in the urban section. The variable speed grid was defined according to the upper and lower boundaries, supposing that the vehicle can never exceed those limits. The variable time grid was defined allowing the optimizer to sufficiently vary around a predicted time of arrival, where V2X and GPS information plays a key role in providing a time arrival estimation. constraints about the maximum available power are introduced.

5. Conclusions

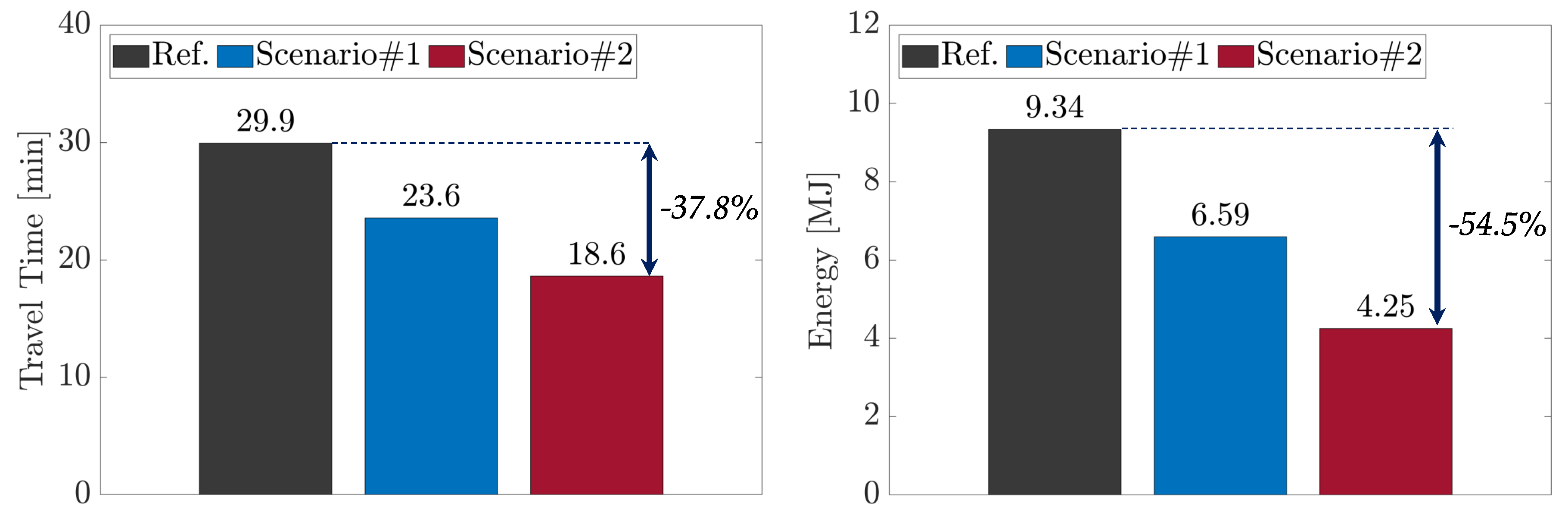

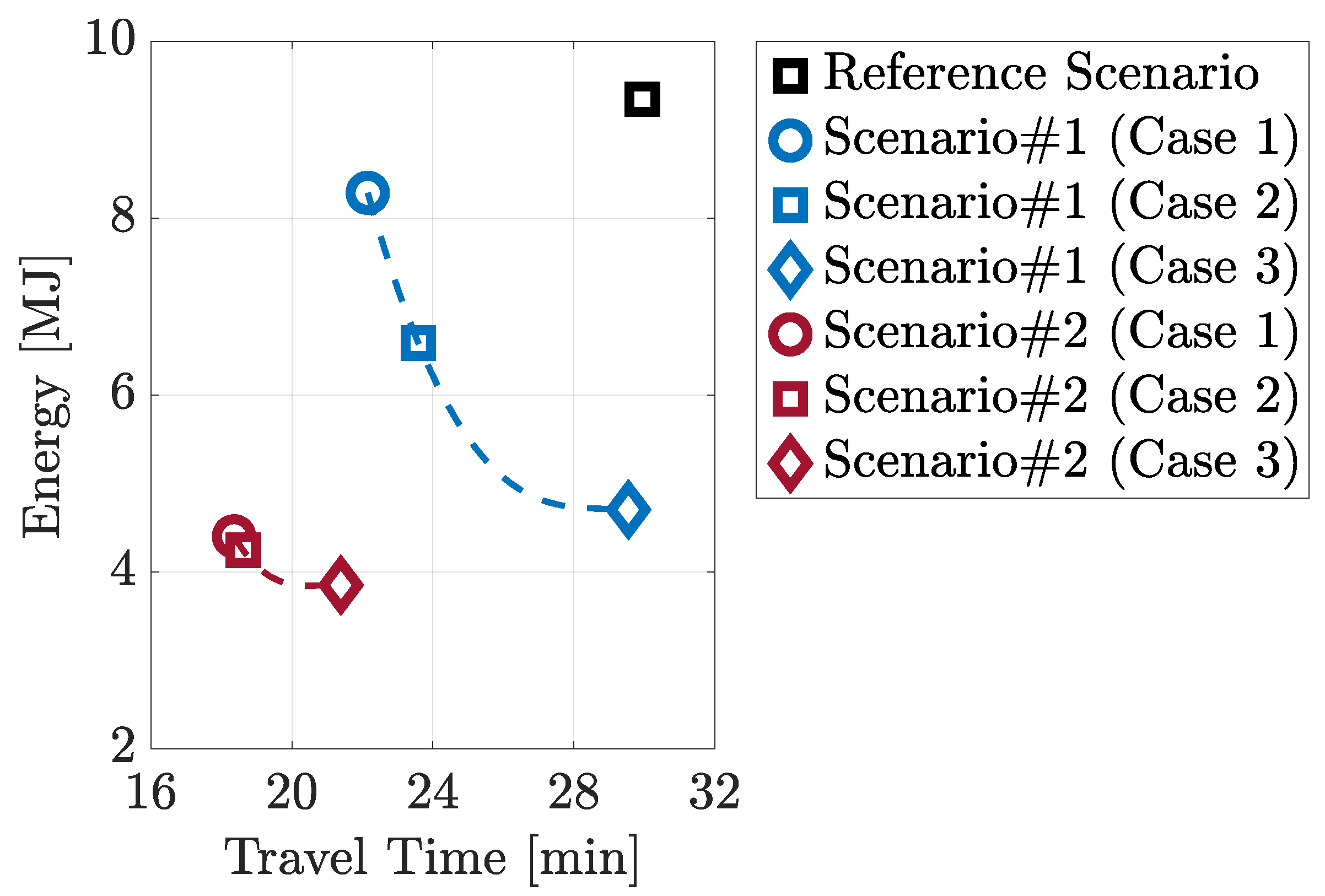

Over the next decade, Connected and Autonomous Vehicles (CAV) technologies are expected to become ever more commonly available on new vehicles. Although their ultimate goal is to improve safety and convenience for customers, they can provide significant information about the planned driver route and the surrounding environment. The knowledge of this information can improve the energy efficiency of a vehicle while reducing, at the same time, travel time. In this framework, this work assessed the benefits that the introduction of Vehicle-to-Vehicle (V2V) and Vehicle-to-Infrastructure (V2I) communication, integrated with cloud computing, can have in a real-world profile in terms of energy and time savings. The Reference Scenario is a pre-defined Real Driving Emissions (RDE) compliant route, while the simulation scenarios were generated by assuming two different levels of penetration of V2X technologies. The associated energy minimization problem was formulated and solved by means of a global optimization algorithm, i.e., Dynamic Programming (DP). The optimization framework included information coming from the surrounding environment, e.g., traffic lights state, speed limits, distance to travel, etc. Energy reduction benefits are dependent on several factors: route characteristics, traffic conditions, driver behavior, etc. For the route evaluated in this paper, numerical results showed that, in an urban context, introducing a smart infrastructure along with optimizing the vehicle speed in a real-world route can potentially reduce the required energy by 54% while shortening the travel time by 38%. The results of the proposed analysis must be considered as a benchmark since the simulations were carried out for a simplified urban traffic network with vehicles in almost free flow, i.e., no direct constraints related to preceding vehicles. However, it can be conceptually extended to the case of multiple vehicles equipped with the proposed algorithm. Finally, a sensitivity analysis was performed on the bi-objective optimization cost function to find a set of Pareto optimal solutions, between energy and travel time minimization. Future work will be aimed at testing the proposed algorithm on different powertrain topologies (i.e., BEV, ICE, PHEV) and assessing the impact that a real-time traffic simulator can have on the results.

Short Biography of Authors

Luca Pulvirenti is currently a Ph.D. student in Energetic at Politecnico di Torino, Italy, where he received his Master of Science in Mechanical Engineering in 2019. His research activity is mainly focused on hybrid electric vehicles to assess the

emissions reduction that can be achieved by synergically exploiting V2X connections and advanced energy management strategies. From November 1st,2019 to August 31st, 2022, he was a visiting student researcher at Stanford University where he worked on the health estimation of battery packs combining electrochemical modeling and data-inspired algorithms.

Luigi Tresca Luigi Tresca is currently a Ph.D. student in Energetic at Politecnico di Torino in Italy, working in the intelligent mobility field, mainly on research activity based on the integration of artificial intelligence models and vehicle connectivity information into the energy management system of hybrid electric vehicles. He got a MSc in Mechanical Engineering at Politecnico di Torino in 2021 and started his Ph.D. program in November 2022.

Luciano Rolando is an Associate Professor of the Energy Department of Politecnico di Torino where he currently teaches courses on Thermal Machines and Hybrid Propulsion Systems. In 2012, Luciano concluded his Ph.D. in Energetics at Politecnico di Torino defending a thesis on the design of hybrid electric vehicle energy management systems, after which he started a Post-Doc position at the same university. During his post-doctoral research activity, he participated to several projects in collaboration with major OEMs, among which it is worth mentioning the Cayman Project which was entitled by Honda Initiation Grant 2012. In 2017 he was enrolled as an assistant professor through a position funded by Ferrari and, afterwards, he won a tenure track position as Associate Professor. Since 2018 Dr. Rolando has also been an invited lecturer for the IFPEN master program in Powertrain Engineering.

Federico Millo is a full professor of automotive internal combustion engines at Politecnico di Torino, Italy, where he also received his master’s degree in mechanical engineering in 1989, before joining the faculty as a researcher assistant in 1991. His research activity has been entirely focused on internal combustion engines, in particular on the analysis and on the diagnostic of the combustion process, on the use of alternative fuels, on pollutant emissions control in s.i. and diesel engines, on engine modelling and on the development of engine control strategies for conventional as well as for hybrid powertrains. He has been principal investigator for several research projects with major OEMs such as General Motors, Honda and Ferrari and has published over 150 articles based off his research activity. Prof. Millo has been nominated SAE Fellow in 2015, being the first Italian from the Academia to be elevated to the role of Fellow.

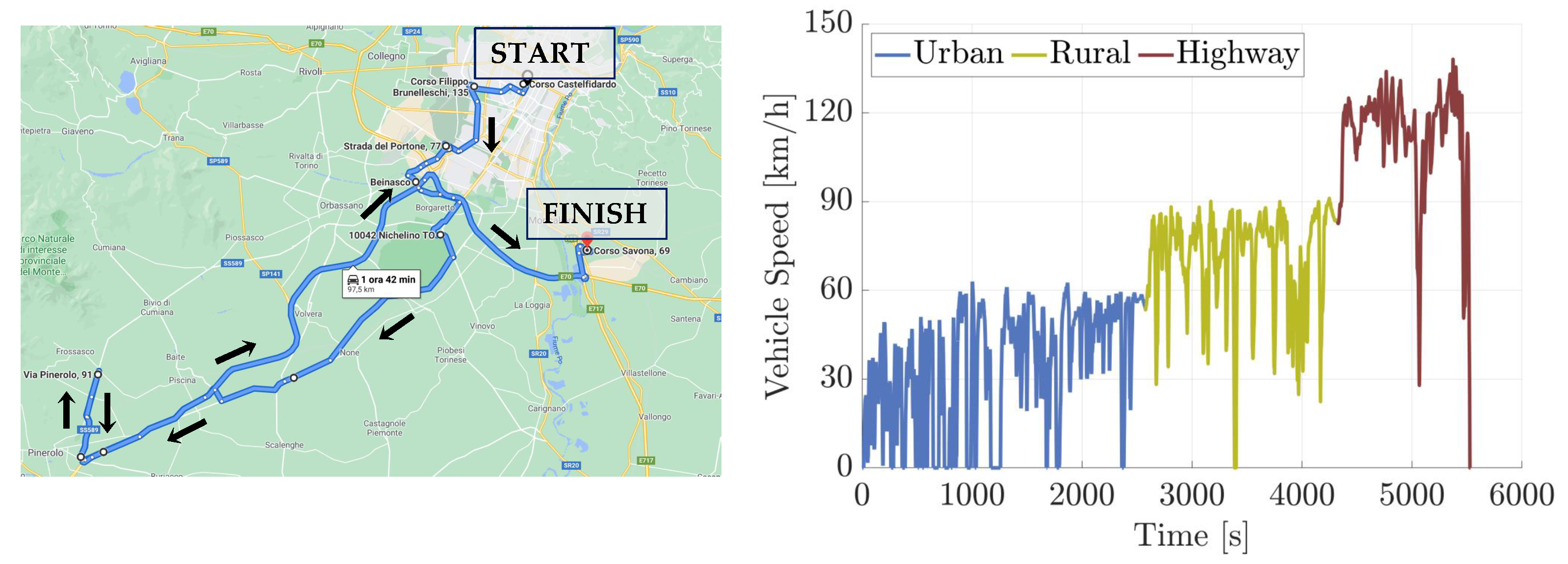

Figure 1.

Reference Scenario: vehicle position was obtained from PEMS and combined with a topographic map (Courtesy of Google Maps). The route lasted approximately 92 minutes and was 96 kilometers long.

Figure 1.

Reference Scenario: vehicle position was obtained from PEMS and combined with a topographic map (Courtesy of Google Maps). The route lasted approximately 92 minutes and was 96 kilometers long.

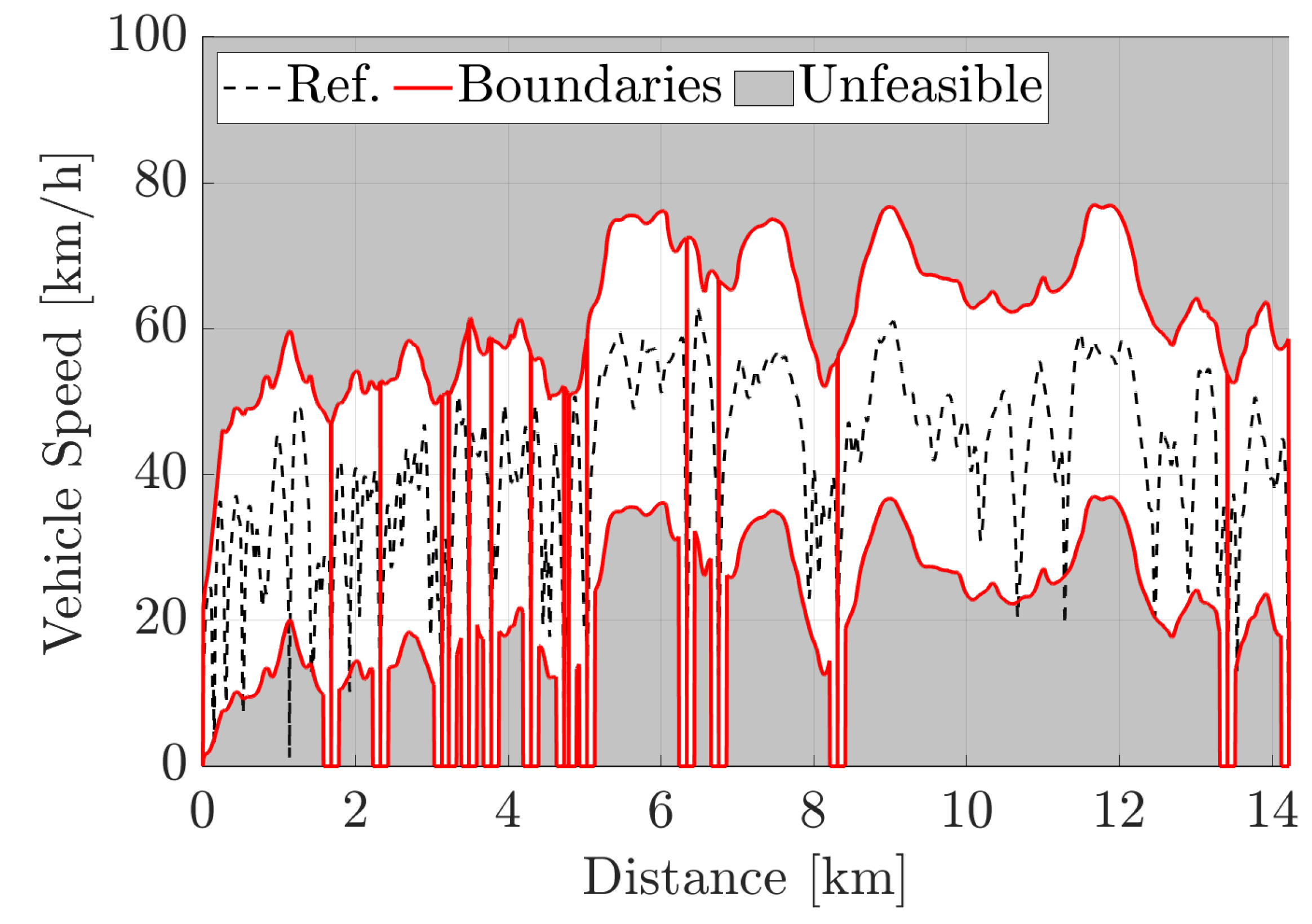

Figure 2.

Speed Boundaries: The upper and lower boundaries of the window were thought to merge the effects of speed limits and mild traffic conditions in a realistic scenario.

Figure 2.

Speed Boundaries: The upper and lower boundaries of the window were thought to merge the effects of speed limits and mild traffic conditions in a realistic scenario.

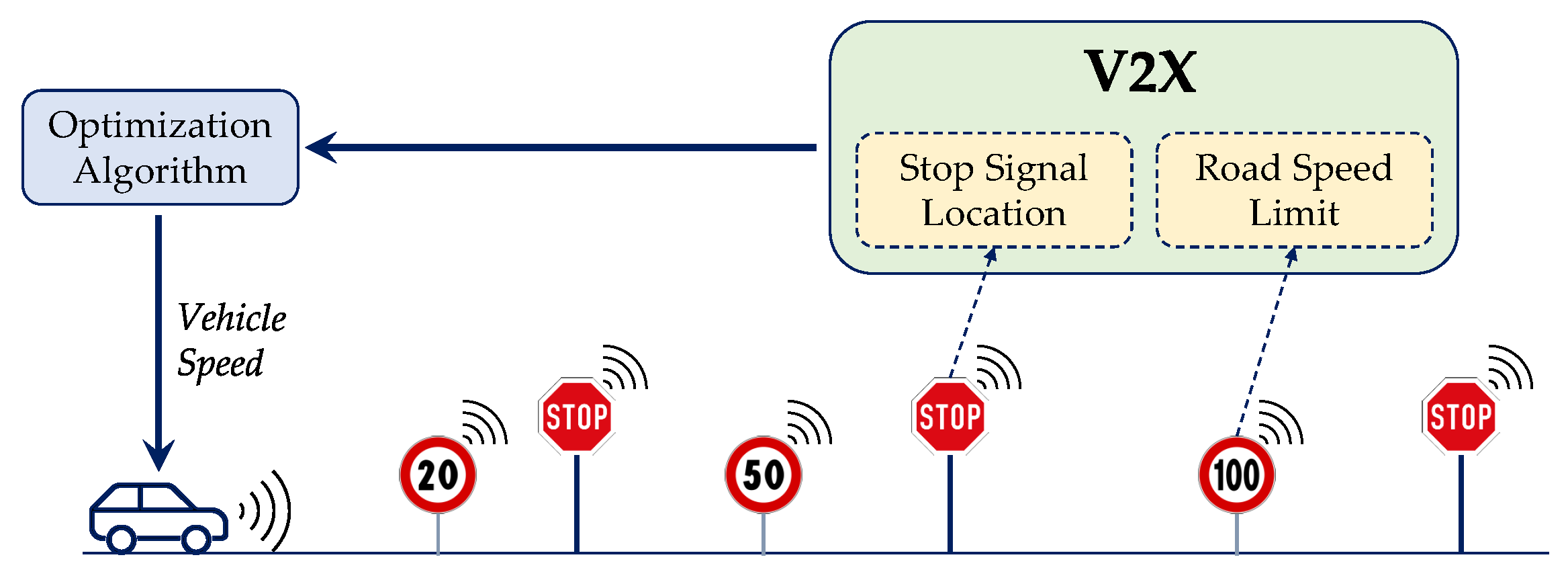

Figure 3.

Scenario #1: it was generated starting from the Reference Scenario and assuming an intersection regulated by a stop sign every time the vehicle comes to a full stop.

Figure 3.

Scenario #1: it was generated starting from the Reference Scenario and assuming an intersection regulated by a stop sign every time the vehicle comes to a full stop.

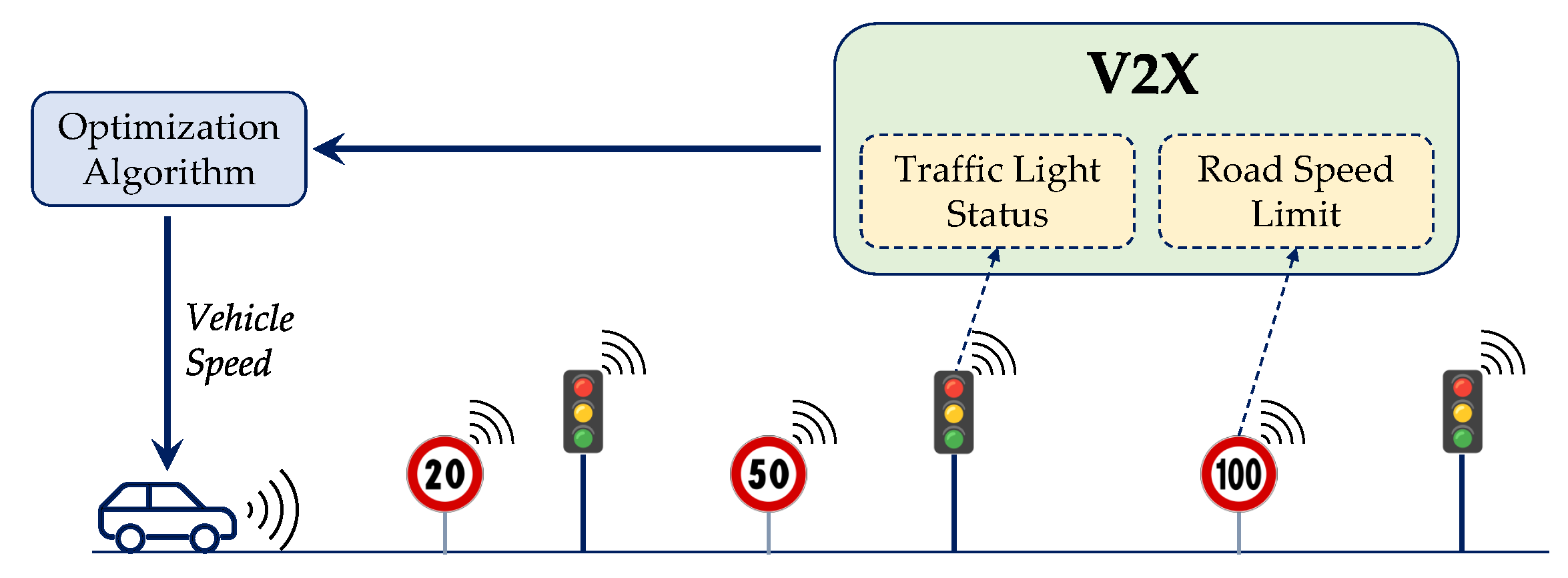

Figure 4.

Scenario #2: it was generated starting from Scenario #1 and converting all the stop signs into traffic lights.

Figure 4.

Scenario #2: it was generated starting from Scenario #1 and converting all the stop signs into traffic lights.

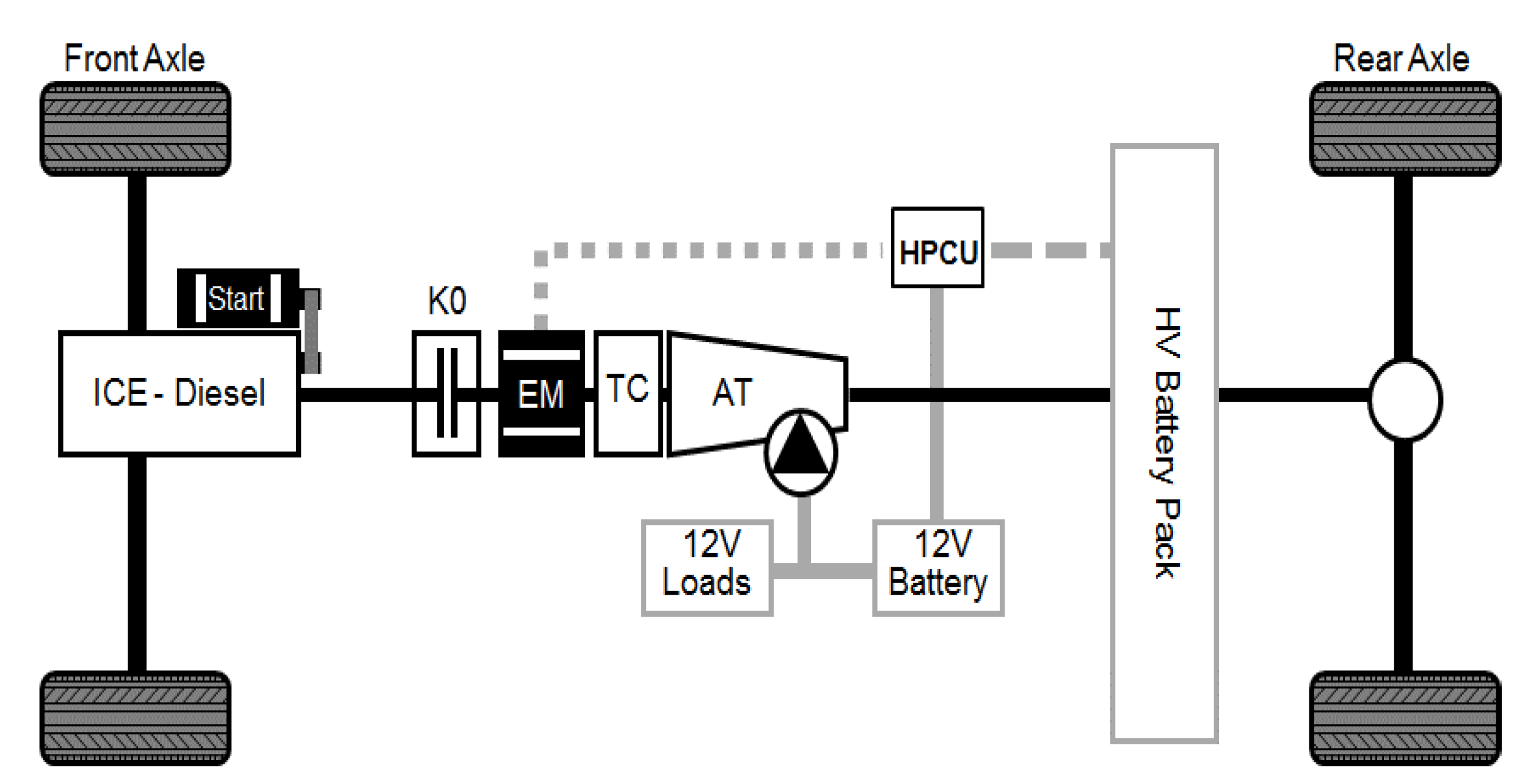

Figure 5.

Powertrain layout: a diesel engine is connected through an auxiliary clutch to an EM. Both the ICE and the EM are connected to the AT by means of a torque converter.

Figure 5.

Powertrain layout: a diesel engine is connected through an auxiliary clutch to an EM. Both the ICE and the EM are connected to the AT by means of a torque converter.

Figure 6.

Scenario #2: computational time for the optimal control problem with a fixed state search grid (grey) and a variable state search grid (light blue). The variable grid allows a reduction in the computational time of more than 95%.

Figure 6.

Scenario #2: computational time for the optimal control problem with a fixed state search grid (grey) and a variable state search grid (light blue). The variable grid allows a reduction in the computational time of more than 95%.

Figure 7.

Variable state search grid: the variable speed grid was defined according to the upper and lower boundaries, supposing that the vehicle can never exceed those limits. The variable time grid was defined allowing the optimizer to sufficiently vary around a predicted time of arrival.

Figure 7.

Variable state search grid: the variable speed grid was defined according to the upper and lower boundaries, supposing that the vehicle can never exceed those limits. The variable time grid was defined allowing the optimizer to sufficiently vary around a predicted time of arrival.

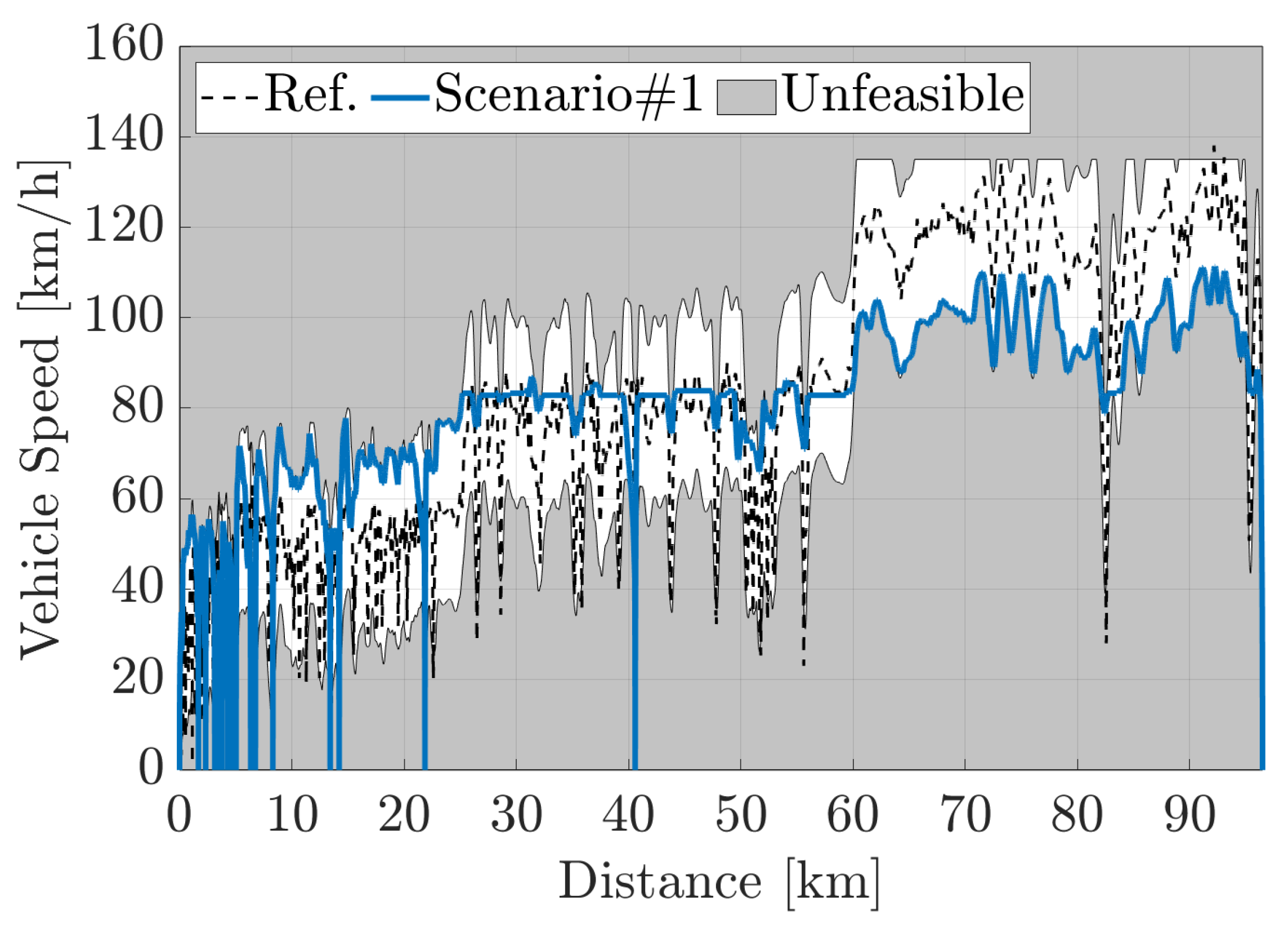

Figure 8.

Scenario #1: optimized vehicle speed compared to the Reference Scenario on the RDE-compliant route.

Figure 8.

Scenario #1: optimized vehicle speed compared to the Reference Scenario on the RDE-compliant route.

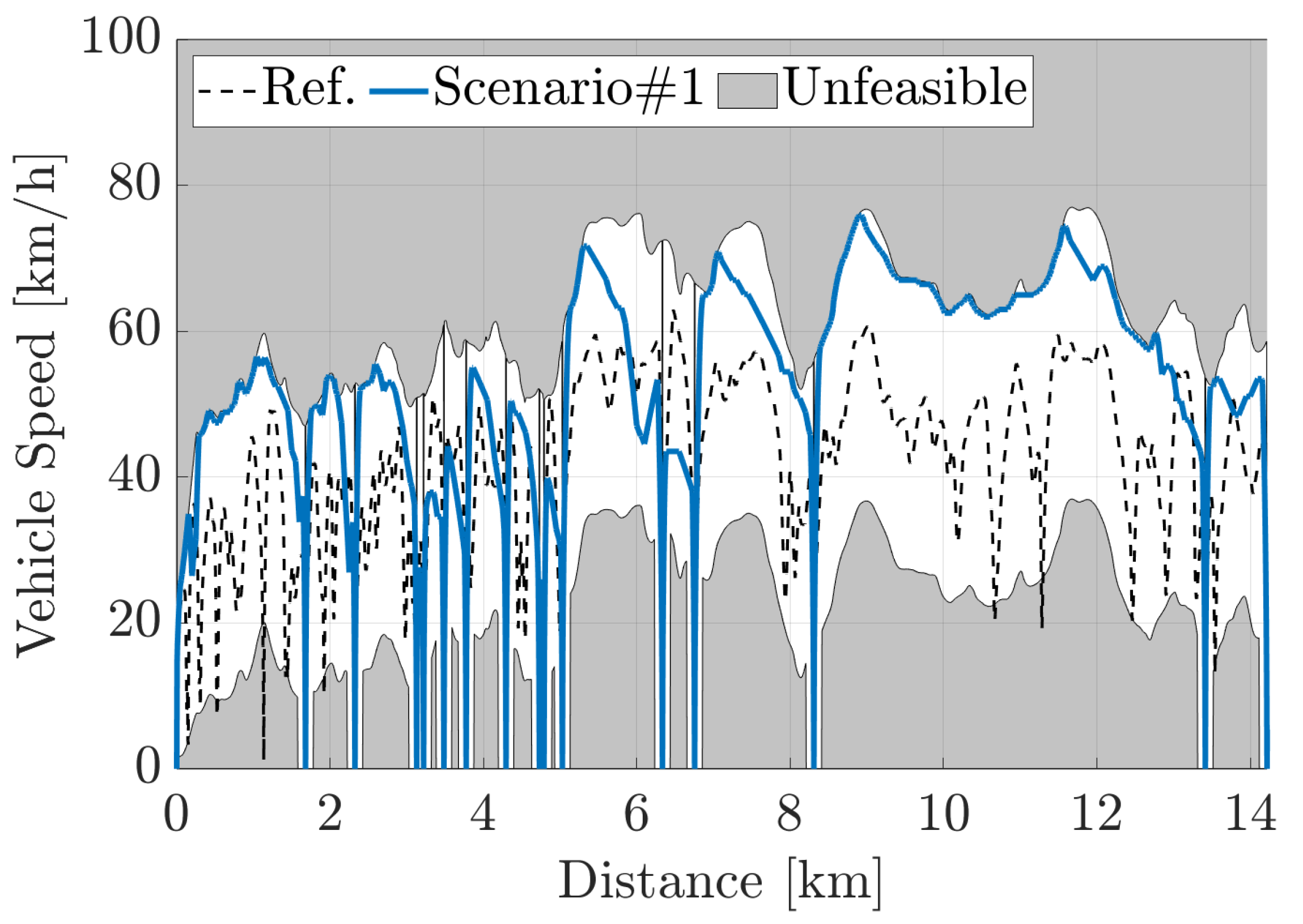

Figure 9.

Scenario #1: optimized vehicle speed compared to the Reference Scenario on the urban section of the RDE-compliant route.

Figure 9.

Scenario #1: optimized vehicle speed compared to the Reference Scenario on the urban section of the RDE-compliant route.

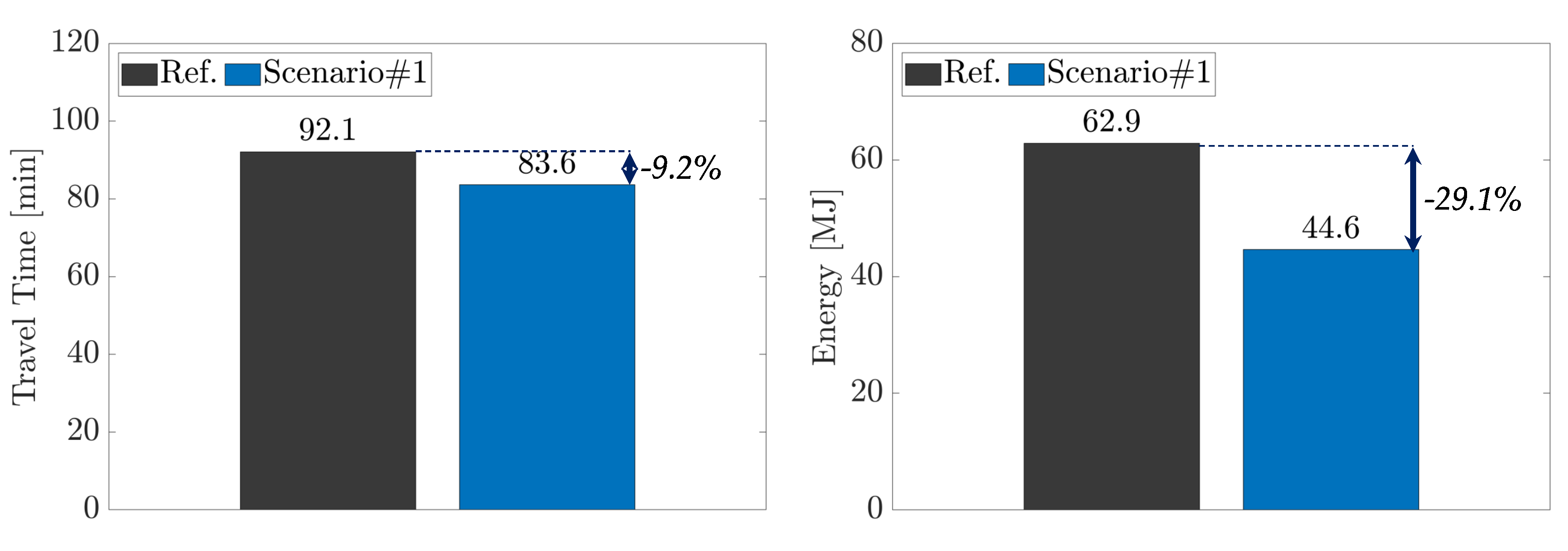

Figure 10.

Scenario #1: achievable reductions in terms of travel time and energy on the RDE-compliant route.

Figure 10.

Scenario #1: achievable reductions in terms of travel time and energy on the RDE-compliant route.

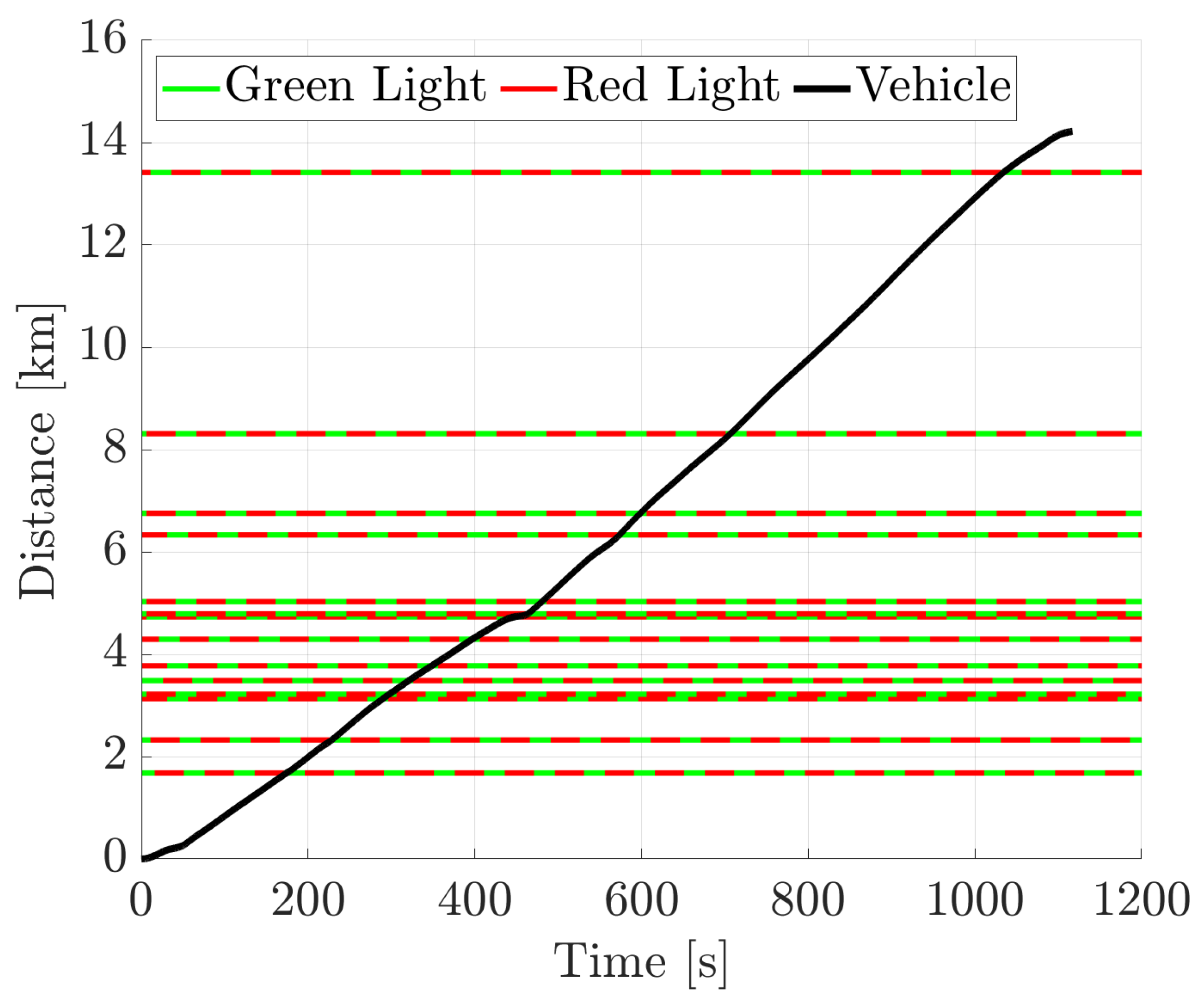

Figure 11.

Scenario #2: vehicle position as a function of the time axis along with all the traffic light phases. The optimizer chooses the best speed trajectory in order to cross all the intersections at a green light.

Figure 11.

Scenario #2: vehicle position as a function of the time axis along with all the traffic light phases. The optimizer chooses the best speed trajectory in order to cross all the intersections at a green light.

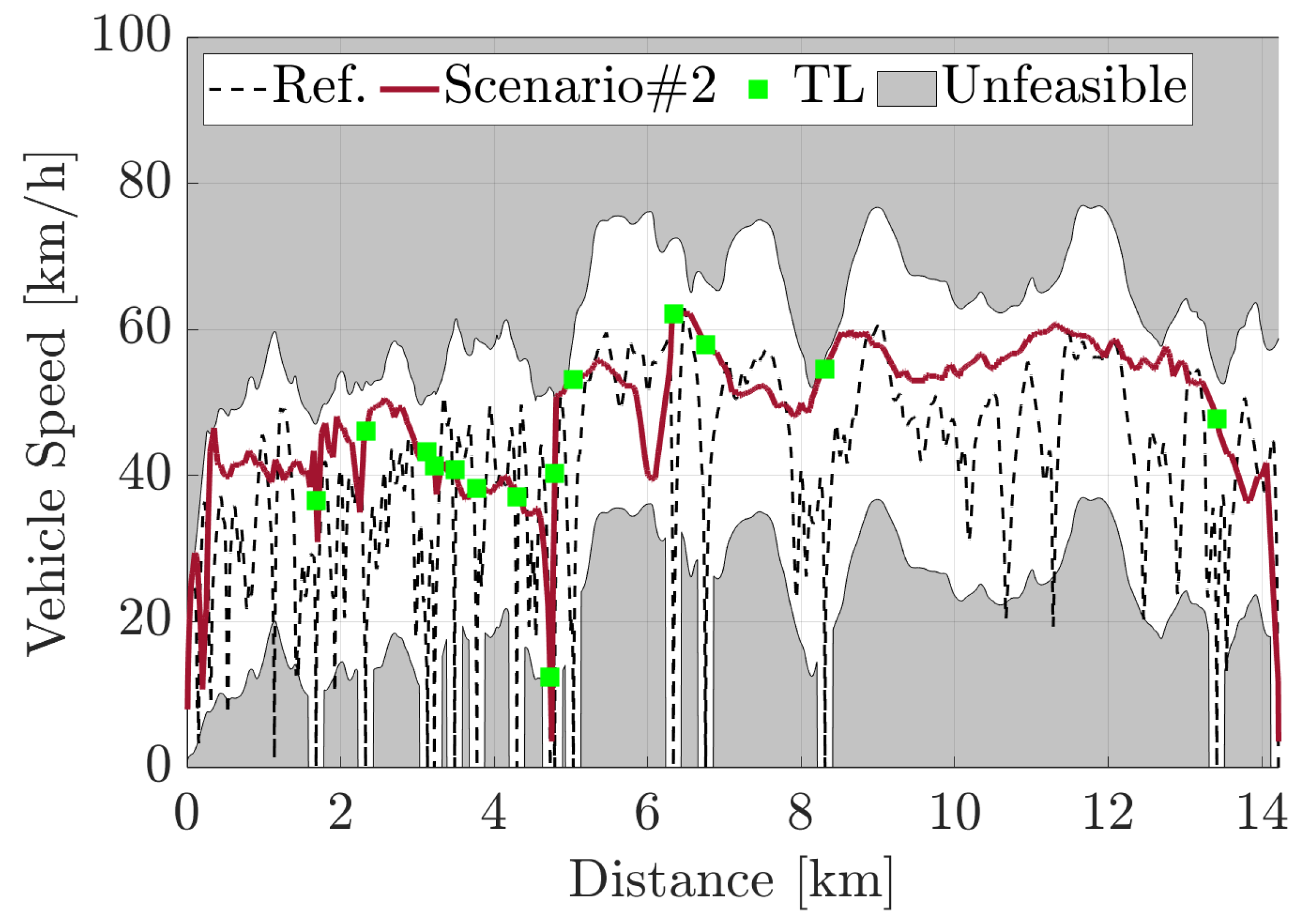

Figure 12.

Scenario #2: optimized vehicle speed compared to the Reference Scenario on the urban section of the RDE-compliant route.

Figure 12.

Scenario #2: optimized vehicle speed compared to the Reference Scenario on the urban section of the RDE-compliant route.

Figure 13.

Scenario #2: achievable reductions in terms of travel time and energy on the urban section of the RDE-compliant route.

Figure 13.

Scenario #2: achievable reductions in terms of travel time and energy on the urban section of the RDE-compliant route.

Figure 14.

Pareto front between energy and travel time for both Scenario #1 and Scenario #2 when varying the value of the weighting factor .

Figure 14.

Pareto front between energy and travel time for both Scenario #1 and Scenario #2 when varying the value of the weighting factor .

Table 1.

Vehicle and powertrain main specifications.

Table 1.

Vehicle and powertrain main specifications.

| Vehicle |

Curb Weight [kg] |

2060 |

| Power [kW] @ 100 km/h |

14.9 |

| Transmission |

Type |

9-AT w/ Torque Converter |

| ICE |

Type |

Turbo Diesel |

| # of Cylinders |

4 |

| Displacement

|

1950 |

| Max Power [kW] |

143 |

| Max Torque [Nm] |

400 |

| Compression Ratio |

15.5:1 |

| EM |

Type |

PM Synchronous Motor |

| Max Power [kW] |

90 |

| Max Torque [Nm] |

440 |

| Max Speed [rpm] |

6000 |

Table 2.

State and control variables for Scenario #1 and Scenario #2.

Table 2.

State and control variables for Scenario #1 and Scenario #2.

| |

Scenario #1 |

Scenario #2 |

| State Variables |

Speed |

Speed, Time |

| Control Variables |

Acceleration |

Acceleration |