Submitted:

11 April 2023

Posted:

12 April 2023

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

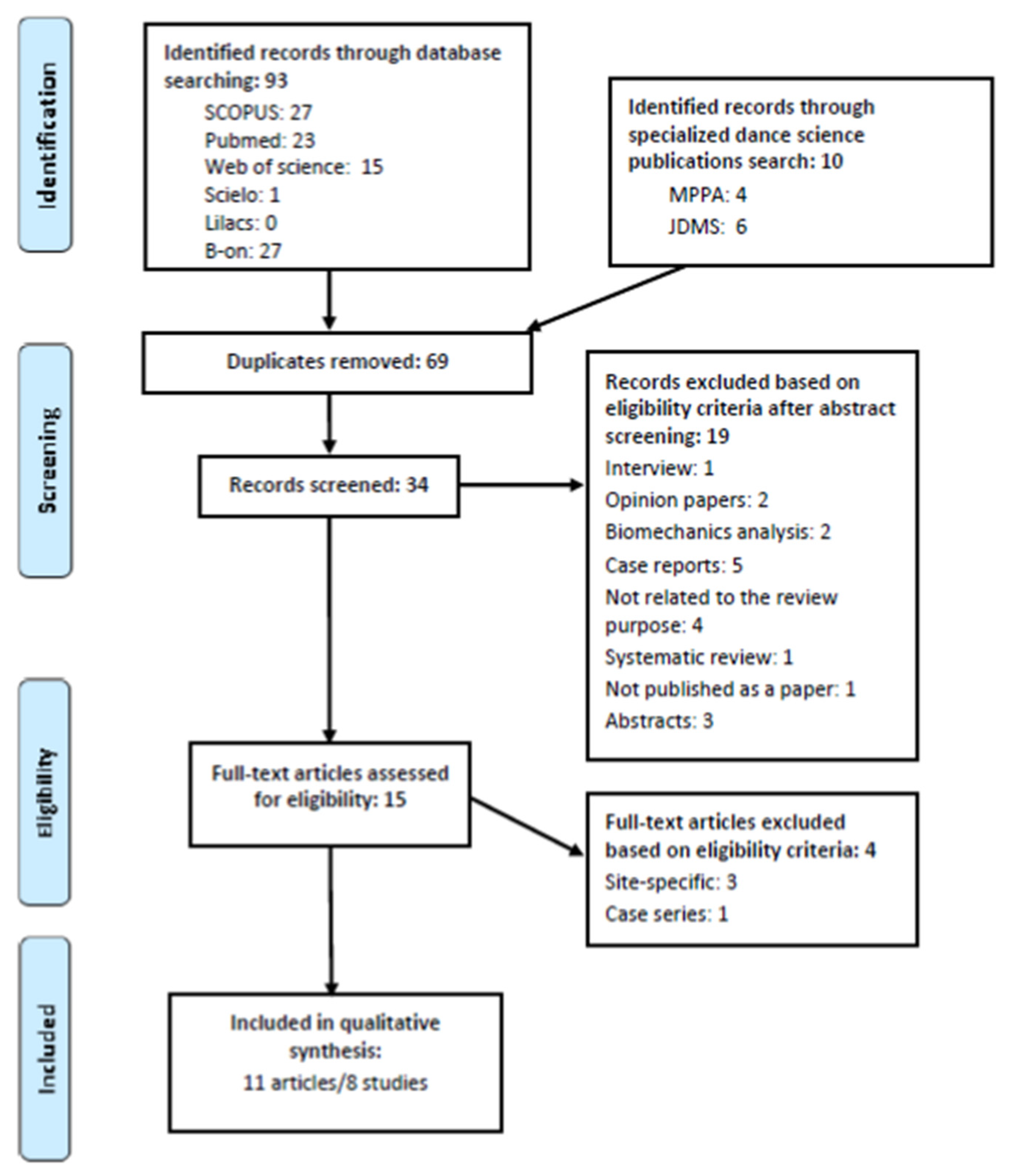

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Protocol and Registration

2.2. Eligibility Criteria

2.3. Search Strategy

2.4. Selection Process

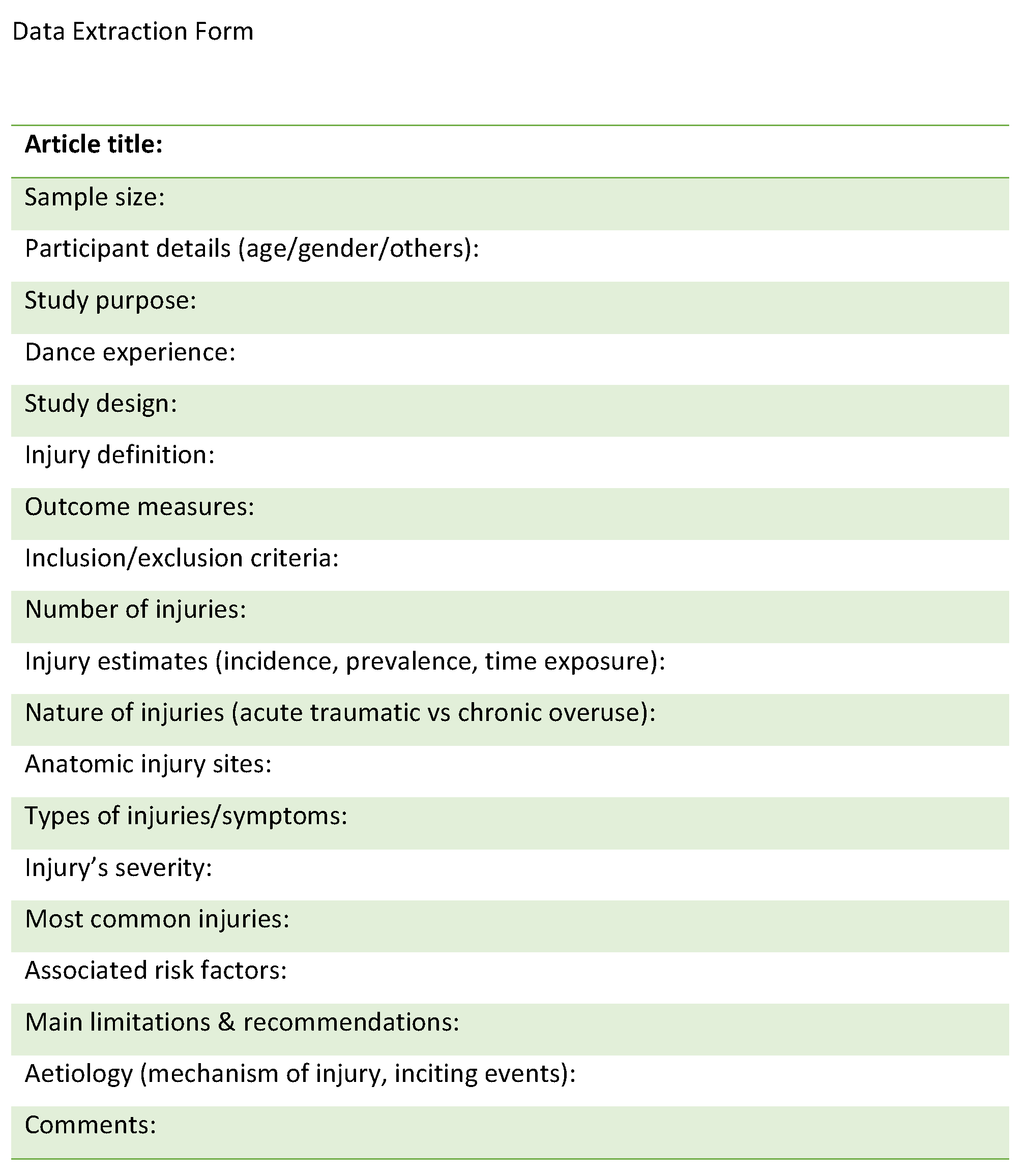

2.5. Data Collection Process

2.6. Study Quality Assessment

3. Results

3.1. Study Characteristics

| Author (Year) | Study Design (Data Source) |

Sample size (n=) | Age (means ± SD (range) years | Sex (F/M) | Level | Dance experience (means ± SD years) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| McGuinness et al. (2006) | Cross-sectional Retrospective (questionnaire 5y) | 159 | 18 ± 3 (15-27) | 142/17 | Competitors | 11 ± 4 (1-20) |

| Noon et al. (2010) | Cross-sectional retrospective (chart review 7y) | 69 | 13,1 (8-23) | 69/0 | 3 (compete in small, local competitions), 4 (as well as regional competitions) and 5 (qualify for international competitions) | Not reported |

| Stein et al. (2013) | Cross-sectional retrospective (medical records 11y) + Cross-sectional Retrospective (questionnaire) | 255 | 13,7 ± 5 (4 – 47), 95%<19 | 247/8 | Not reported | Not reported |

| Cahalan et al. (2013) | Cross-sectional (retrospective online questionnaire – entire career) | 178 | >18 72% (25-34) | 111/67 | Professional | 13,2 ± 3,4 |

| Eustergerling et al. (2015) | Cross-sectional retrospective questionnaire (1y) | 36 | 16 (12–46) | 35/1 | 22 elite/14 non-elite | Not reported |

| Cahalan et al. (2015) Cahalan et al. (2016) |

Cross-sectional retrospective (questionnaire 5y + physical screening) | 104 (questionnaire) 84 (physical screening) | Median (IQR) prof. 23 (21; 27,5), stud. 20 (19,22), comp. 20 (18,5; 20) | % prof. 50/50 stud. 85,7/14,3 comp. 80/20 |

Elite. 36 (34,6%) professionals, 28 (26,9%) students, 40 (38,5%) competitive | Prof. 17,5 ± 5,6 stud. 13,8 ± 5,3 comp. 13,0 ± 3,8 |

| Prospective cohort (1y) (online questionnaire every month) | 84 | Median (IQR) 20 (19-23,5) | 66/18 | Elite: Professional-15; Students-31; Competitive-38 | 14 (approx.) | |

| Cahalan, Kearney et al. (2018) Cahalan, Comber et al. (2019) |

Prospective (questionnaire every week over 1 year) | 21 ID + 29 CD | 21,5 ± 1,7 | 20/1 | Pre-professional students (full time students university) | “extensive dance experience” |

| Cross-sectional (retrospective questionnaire 1y + physical screening) | 27 ID | Median (IQR) 21(3) | 24/3 | Pre-professional students (full time students university) | “extensive dance experience” | |

| Cahalan, Bargary et al. (2019) Cahalan, Bargary et al. (2018) |

Prospective (questionnaire every week over 1 year) | 37 | 13-17 | 33/4 | Elite | Competing at open (elite) level for a period of at least 1 year |

| Cross-sectional (retrospective questionnaire 1y + physical screening) | 37 | 13-17 | 33/4 | Elite | Competing at open (elite) level for a period of at least 1 year |

3.2. Risk of Bias and Level of Evidence

| Items/ Reference |

McGuinness et al. (2006) | Noon et al. (2010) | Stein et al. (2013) | Cahalan et al. (2013) | Eustergerling et al. (2015) | Cahalan et al. (2015) | Cahalan et al. (2016) | Cahalan, Bargary et al. (2018) | Cahalan, Kearney et al. (2018) | Cahalan, Comber et al. (2019) | Cahalan, Bargary et al. (2019) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Reporting | |||||||||||

| 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| 2 | 1 | 0a | 1 | 1 | 0 a | 1 | 1 | 0 a | 1 | 0 a | 1 |

| 3 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| 5 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | NA | 0 |

| 6 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| 7 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| 10 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| External Validity |

|||||||||||

| 11 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 12 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Internal Validity (Bias) |

|||||||||||

| 16 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| 18 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| 20 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| Internal Validity (Confounding) |

|||||||||||

| 21 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | NA | 1 |

| 22 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | NA | 1 |

| 25 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Score | 10 | 7 | 10 | 10 | 10 | 11 | 11 | 10 | 11 | 8 | 11 |

| Percentage Score (%) | 63 | 44 | 63 | 63 | 63 | 69 | 69 | 63 | 69 | 67 | 69 |

| Level of Evidence | 3c | 3c | 3c | 3c | 3c | 3c | 3b | 3c | 3b | 3c | 3b |

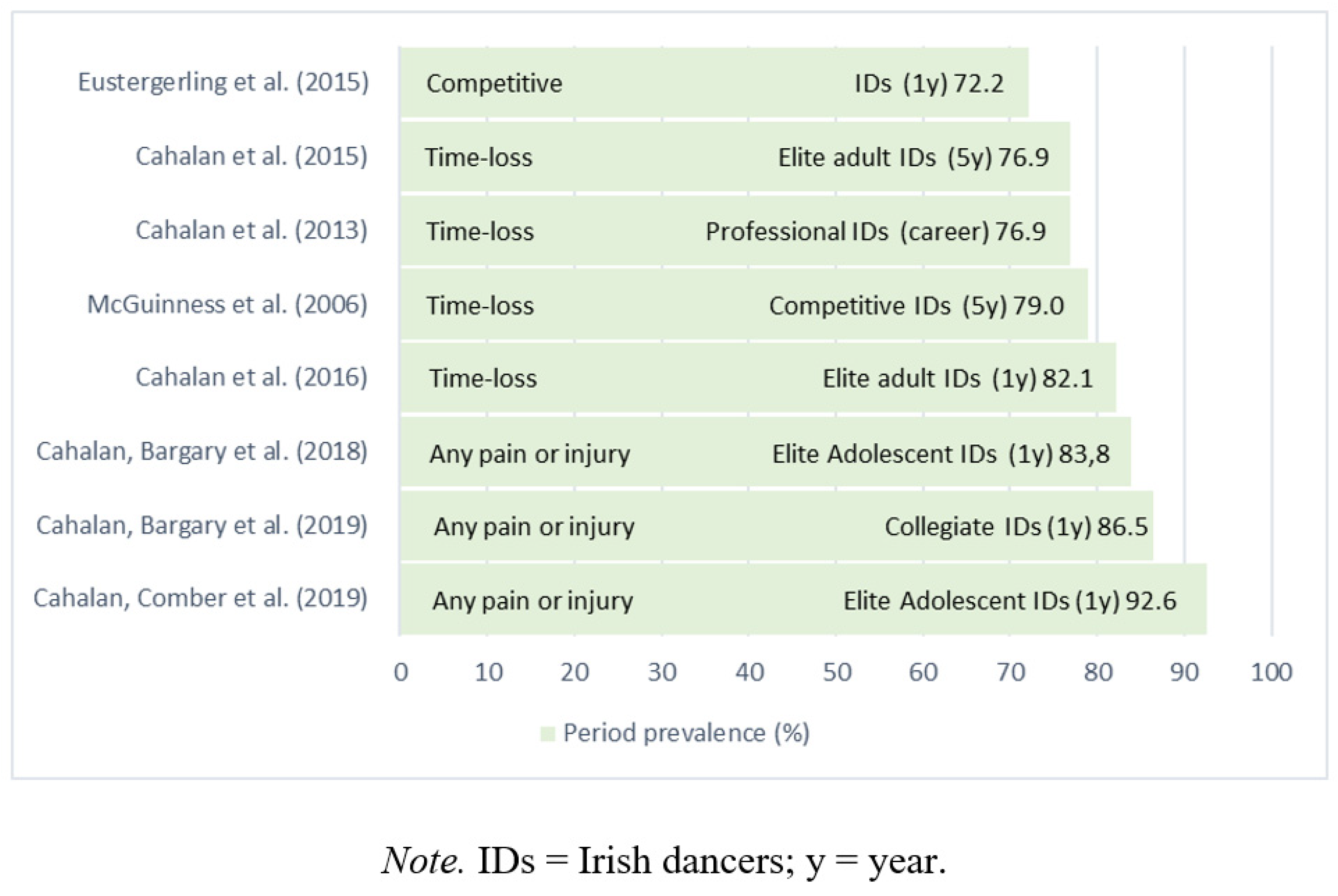

3.3. Injury Estimates

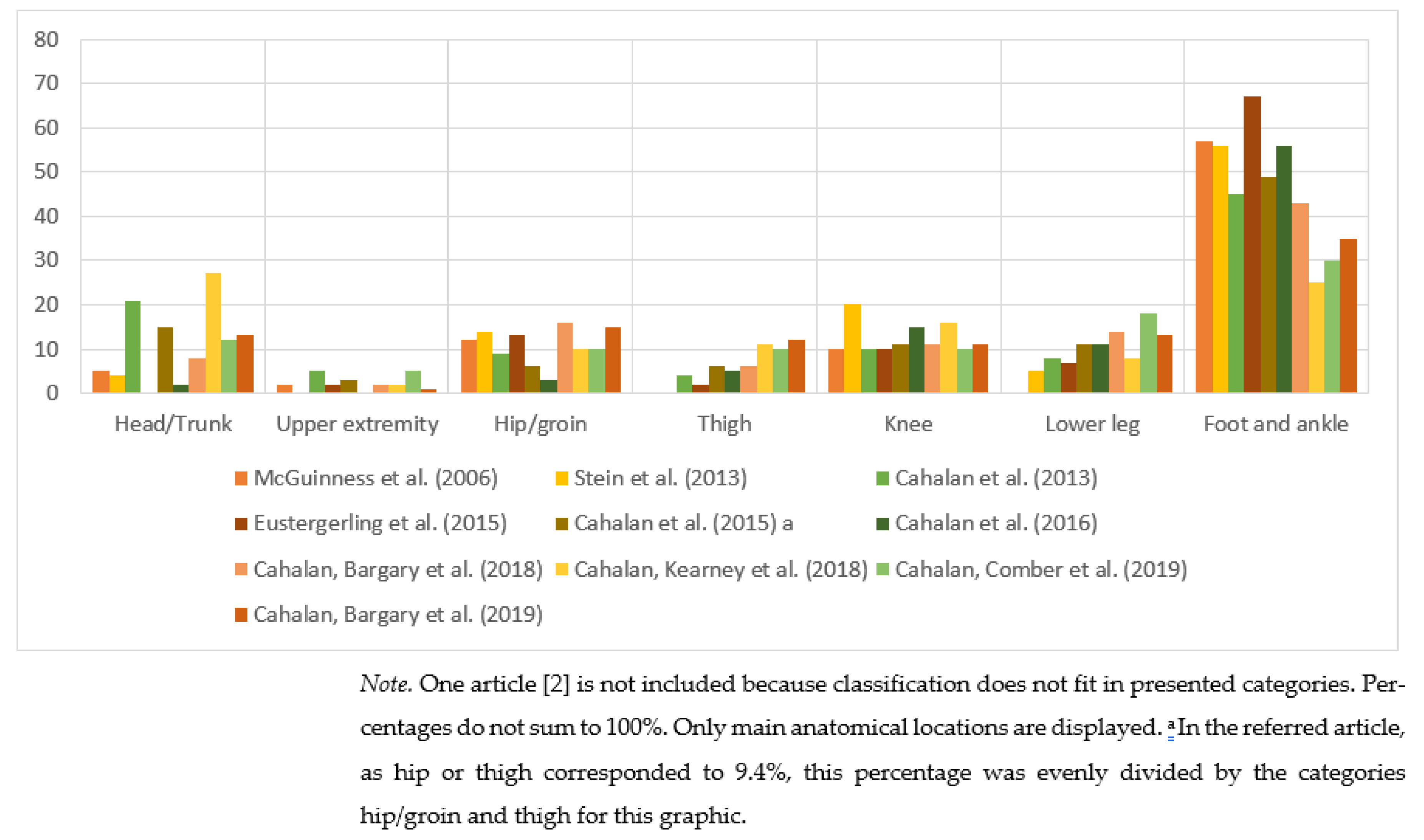

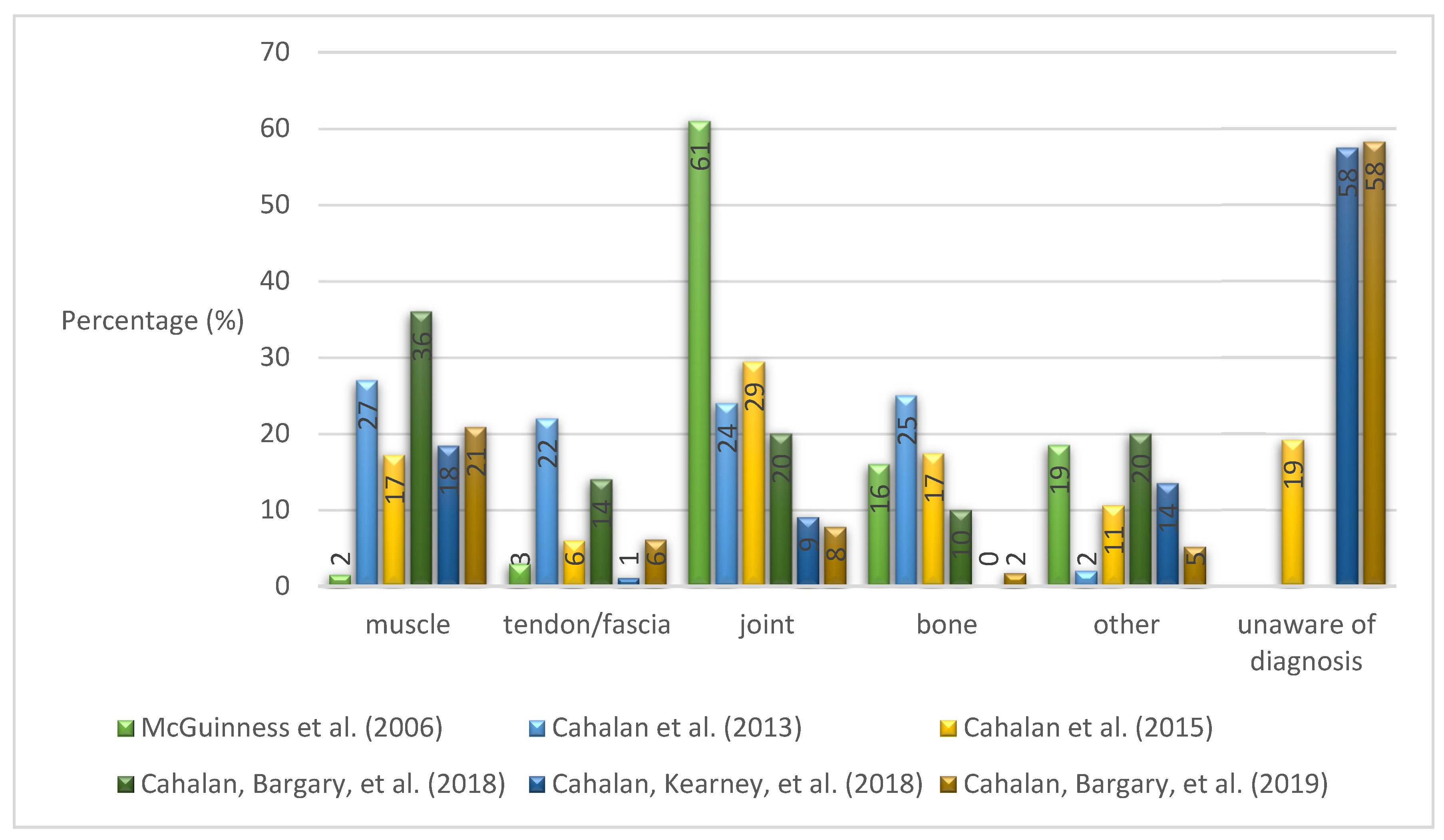

3.4. Anatomical Location

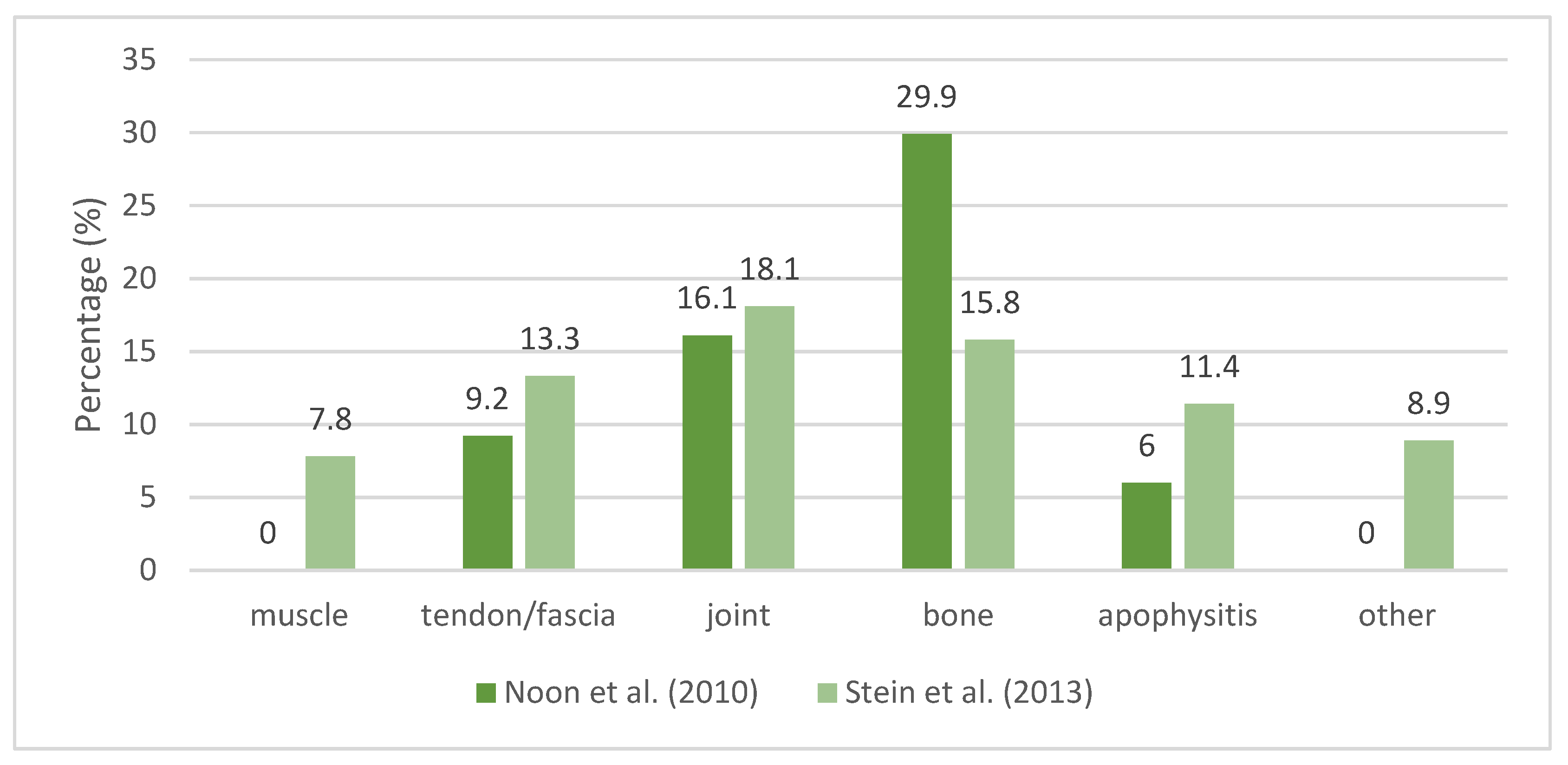

3.5. Type of Injuries

3.6. Nature, Severity and Aetiology of Injuries

3.7. Associated Factors

4. Discussion

4.1. Summary of Evidence

4.1.1. Prevalence/Incidence

4.1.2. Occurrence Pattern of Musculoskeletal Injuries

4.1.3. Associated Factors

4.4. Limitations

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

References

- Foley, C. Perceptions of Irish Step Dance: National, Global, and Local. Danc. Res. J. 2001, 33, 34. [CrossRef]

- Noon, M.; Hoch, A.Z.A.Z.A.Z.; McNamara, L.; Schimke, J. Injury Patterns in Female Irish Dancers. PM R 2010, 2, 1030–1034. [CrossRef]

- Cahalan, R.; O’Sullivan, P.; Purtill, H.; Bargary, N.; Ni Bhriain, O.; O’Sullivan, K. Inability to Perform Because of Pain/Injury in Elite Adult Irish Dance: A Prospective Investigation of Contributing Factors. Scand. J. Med. Sci. Sport. 2016, 26, 694–702. [CrossRef]

- Cahalan, R.; Kearney, P.; Ni Bhriain, O.; Redding, E.; Quin, E.; McLaughlin, L.C.L.C.L.C.; O’ Sullivan, K. Dance Exposure, Wellbeing and Injury in Collegiate Irish and Contemporary Dancers: A Prospective Study. Phys. Ther. Sport 2018, 34, 77–83. [CrossRef]

- Gans, A. The Relationship of Heel Contact in Ascent and Descent from Jumps to the Incidence of Shin Splints in Ballet Dancers. Phys. Ther. 1985, 65, 1192–1196. [CrossRef]

- Orishimo, K.F.; Kremenic, I.J.; Pappas, E.; Hagins, M.; Liederbach, M. Comparison of Landing Biomechanics between Male and Female Professional Dancers. Am. J. Sports Med. 2009, 37, 2187–2193. [CrossRef]

- Cahalan, R.; Purtill, H.; O’Sullivan, P.; O’Sullivan, K. Foot and Ankle Pain and Injuries in Elite Adult Irish Dancers. Med. Probl. Perform. Art. 2014, 29, 198–206. [CrossRef]

- Ward, R.E.; Fong Yan, A.; Orishimo, K.F.; Kremenic, I.J.; Hagins, M.; Liederbach, M.; Hiller, C.E.; Pappas, E. Comparison of Lower Limb Stiffness between Male and Female Dancers and Athletes during Drop Jump Landings. Scand. J. Med. Sci. Sport. 2019, 29, 71–81. [CrossRef]

- Cahalan, R.; O’Sullivan, K. Musculoskeletal Pain and Injury in Irish Dancing: A Systematic Review. Physiother. Pract. Res. 2013, 34, 83–92. [CrossRef]

- Cahalan, R.; Bargary, N.; O’Sullivan, K. Pain and Injury in Elite Adolescent Irish Dancers: A Cross-Sectional Study. J. Danc. Med. Sci. 2018, 22, 91–99. [CrossRef]

- Cahalan, R.; Bargary, N.; O’Sullivan, K. Dance Exposure, General Health, Sleep and Injury in Elite Adolescent Irish Dancers: A Prospective Study. Phys. Ther. Sport 2019, 40, 153–159. [CrossRef]

- Cahalan, R.; Comber, L.; Gaire, D.; Quin, E.; Redding, E.; Ni Bhriain, O.; O’Sullivan, K. Biopsychosocial Characteristics of Contemporary and Irish University-Level Student Dancers A Pilot Study. J. Danc. Med. Sci. 2019, 23, 63–71. [CrossRef]

- Cahalan, R.; Purtill, H.; O’Sullivan, P.; O’Sullivan, K. A Cross-Sectional Study of Elite Adult Irish Dancers: Biopsychosocial Traits, Pain, and Injury. J. Dance Med. Sci. 2015, 19, 31–43. [CrossRef]

- Cahalan, R.; O’Sullivan, K. Injury in Professional Irish Dancers. J. Danc. Med. Sci. 2013, 17, 150–158. [CrossRef]

- Eustergerling, M.; Emery, C. Risk Factors for Injuries in Competitive Irish Dancers Enrolled in Dance Schools in Calgary, Canada. Med. Probl. Perform. Art. 2015, 30, 26–29. [CrossRef]

- Stein, C.J.; Tyson, K.D.; Johnson, V.M.; Popoli, D.M.; D’Hemecourt, P.A.; Micheli, L.J. Injuries in Irish Dance. J. Dance Med. Sci. 2013, 17, 159–164. [CrossRef]

- Liederbach, M.; Hagins, M.; Gamboa, J.M.; Welsh, T.M. Assessing and Reporting Dancer Capacities, Risk Factors, and Injuries: Recommendations from the IADMS Standard Measures Consensus Initiative. J. Dance Med. Sci. 2012, 16, 139–153.

- Van Mechelen, W. Sports Injury Surveillance Systems: “One Size Fits All?” Sport. Med. 1997, 24, 164–168. [CrossRef]

- Liberati, A.; Altman, D.G.; Tetzlaff, J.; Mulrow, C.; Gøtzsche, P.C.; Ioannidis, J.P.A.; Clarke, M.; Devereaux, P.J.; Kleijnen, J.; Moher, D. The PRISMA Statement for Reporting Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses of Studies That Evaluate Healthcare Interventions: Explanation and Elaboration. BMJ 2009, 339. [CrossRef]

- Bahr, R.; Clarsen, B.; Derman, W.; Dvorak, J.; Emery, C.A.; Finch, C.F.; Hägglund, M.; Junge, A.; Kemp, S.; Khan, K.M.; et al. International Olympic Committee Consensus Statement: Methods for Recording and Reporting of Epidemiological Data on Injury and Illness in Sport 2020 (Including STROBE Extension for Sport Injury and Illness Surveillance (STROBE-SIIS)). Br. J. Sports Med. 2020, 32. [CrossRef]

- Sanderson, S.; Tatt, I.D.; Higgins, J.P.T. Tools for Assessing Quality and Susceptibility to Bias in Observational Studies in Epidemiology: A Systematic Review and Annotated Bibliography. Int. J. Epidemiol. 2007, 36, 666–676.

- Page, M.J.; McKenzie, J.E.; Higgins, J.P.T. Tools for Assessing Risk of Reporting Biases in Studies and Syntheses of Studies: A Systematic Review. BMJ Open 2018, 8, 1–16. [CrossRef]

- Downs, S.H.; Black, N. The Feasibility of Creating a Checklist for the Assessment of the Methodological Quality Both of Randomised and Non-Randomised Studies of Health Care Interventions. J. Epidemiol. Community Health 1998, 52, 377–384. [CrossRef]

- O’Connor, S.R.; Tully, M.A.; Ryan, B.; Bradley, J.M.; Baxter, G.D.; McDonough, S.M. Failure of a Numerical Quality Assessment Scale to Identify Potential Risk of Bias in a Systematic Review: A Comparison Study. BMC Res. Notes 2015, 8. [CrossRef]

- Moita, J.P.; Nunes, A.; Esteves, J.; Oliveira, R.; Xarez, L. The Relationship between Muscular Strength and Dance Injuries: A Systematic Review. Med. Probl. Perform. Art. 2017, 32, 40–50. [CrossRef]

- Howick, J.; Phillips, B.; Ball C, et al. Oxford Centre for Evidence-Based Medicine: Levels of Evidence Secondary Oxford Centre for Evidence-Based Medicine: Levels of Evidence 2009. 2009, 2009.

- Kenny, S.J.; Whittaker, J.L.; Emery, C.A. Risk Factors for Musculoskeletal Injury in Preprofessional Dancers: A Systematic Review. Br. J. Sports Med. 2016, 50, 997–1003. [CrossRef]

- Biernacki, J.; Stracciolini, A.; Fraser, J.; Micheli, L.; Sugimoto, D. Risk Factors for Lower-Extremity Injuries in Female Ballet Dancers. Clin. J. Sport Med. 2018, 1. [CrossRef]

- Beasley, M.A.; Stracciolini, A.; Tyson, K.D.; Stein, C.J. Knee Injury Patterns in Young Irish Dancers. Med. Probl. Perform. Art. 2014, 29, 70–73. [CrossRef]

- Cahalan, R.; Purtill, H.; O’Sullivan, K. Biopsychosocial Factors Associated with Foot and Ankle Pain and Injury in Irish Dance: A Prospective Study. Med. Probl. Perform. Art. 2017, 32, 111–117. [CrossRef]

- Walls, R.J.J.; Brennan, S.A.A.; Hodnett, P.; O’Byrne, J.M.M.; Eustace, S.J.J.; Stephens, M.M.M.; O’Byrne, J.M.; Eustace, S.J.J.; Stephens, M.M.M. Overuse Ankle Injuries in Professional Irish Dancers. Foot Ankle Surg. 2010, 16, 45–49. [CrossRef]

- McGuinness, D.; Doody, C. The Injuries of Competitive Irish Dancers. J. Danc. Med. Sci. 2006, 10, 35–39.

- Kenny, S.J.; Palacios-Derflingher, L.; Whittaker, J.L.; Emery, C.A. The Influence of Injury Definition on Injury Burden in Preprofessional Ballet and Contemporary Dancers. J. Orthop. Sports Phys. Ther. 2018, 48, 185–193. [CrossRef]

- Jacobs, C.L.; Cassidy, J.D.; Côté, P.; Boyle, E.; Ramel, E.; Ammendolia, C.; Hartvigsen, J.; Schwartz, I. Musculoskeletal Injury in Professional Dancers: Prevalence and Associated Factors: An International Cross-Sectional Study. Clin. J. Sport Med. 2017, 27, 153–160. [CrossRef]

- Mayers, L.; Judelson, D.; Bronner, S. The Prevalence of Injury among Tap Dancers. J. Danc. Med. Sci. 2003, 7, 121–125.

- Shippen, J.M.; May, B. Calculation of Muscle Loading and Joint Contact Forces during the Rock Step in Irish Dance. J. Danc. Med. & Sci. Off. Publ. Int. Assoc. Danc. Med. & Sci. 2010, 14, 11–18.

- Radcliffe, C.R.; Coltman, C.E.; Spratford, W.A. The Effect of Fatigue on Peak Achilles Tendon Force in Irish Dancing-Specific Landing Tasks. Sport. Biomech. 2021, 00, 1–14. [CrossRef]

- Christensen, S.K.; Johnson, A.W.; Van, N.; Corey, T.E.; Mcclung, M.S.; Hunter, I. Characteristics of Eight Irish Dance Landings Considerations for Training and Overuse Injury Prevention. J. Danc. Med. Sci. 2021, 25, 30–37. [CrossRef]

- Junge, A.; Dvorak, J. Influence of Definition and Data Collection on the Incidence of Injuries in Football. Am. J. Sports Med. 2000, 28, 40–46. [CrossRef]

- Bronner, S.; Ojofeitimi, S.; Mayers, L. Comprehensive Surveillance of Dance Injuries A Proposal for Uniform Reporting Guidelines for Professional Companies. J. Danc. Med. Sci. 2006, 10, 69–80.

- Clarsen, B.; Bahr, R. Matching the Choice of Injury/Illness Definition to Study Setting, Purpose and Design: One Size Does Not Fit All! Br. J. Sports Med. 2014, 48, 510–512. [CrossRef]

- Mainwaring, L.; Krasnow, D.; Kerr, G. And The Dance Goes On: Psychological Impact of Injury. J. Danc. Med. Sci. 2001, 5, 105–115.

- Higginbotham, O.; Cahalan, R. The Collegiate Irish Dancer’s Experience of Injury: A Qualitative Study. Med. Probl. Perform. Art. 2020, 35, 1–9. [CrossRef]

- Gamboa, J.M.; Robert, L.A.; Fergus, A. Injury Patterns in Elite Preprofessional Ballet Dancers and the Utility of Screening Programs to Identify Risk Characteristics. J. Orthop. Sports Phys. Ther. 2008, 38, 126–136. [CrossRef]

- Luke, A.C.; Kinney, S.A.; D’Hemecourt, P.A.; Baum, J.; Owen, M.; Micheli, L.J. Determinants of Injuries in Young Dancers. Med. Probl. Perform. Art. 2002, 17, 105–112.

- Allen, N.; Ribbans, W.; Nevill, A.; Wyon, M. Musculoskeletal Injuries in Dance: A Systematic Review. Int. J. Phys. Med. Rehabil. 2014, 03. [CrossRef]

- Smith, P.J.; Gerrie, B.J.; Varner, K.E.; McCulloch, P.C.; Lintner, D.M.; Harris, J.D. Incidence and Prevalence of Musculoskeletal Injury in Ballet A Systematic Review. 2015, 1–9. [CrossRef]

- Vassallo, A.J.; Trevor, B.L.; Mota, L.; Pappas, E.; Hiller, C.E. Injury Rates and Characteristics in Recreational, Elite Student and Professional Dancers: A Systematic Review. J. Sports Sci. 2019, 37, 1113–1122. [CrossRef]

- Caine, D.; Bergeron, G.; Goodwin, B.J.; Thomas, J.; Caine, C.G.; Steinfeld, S.; Dyck, K.; André, S. A Survey of Injuries Affecting Pre-Professional Ballet Dancers. J. Dance Med. Sci. 2016, 20, 115–126. [CrossRef]

- Allen, N.; Nevill, A.; Brooks, J.; Koutedakis, Y.; Wyon, M. Ballet Injuries: Injury Incidence and Severity over 1 Year. J. Orthop. Sports Phys. Ther. 2012, 42, 781–790. [CrossRef]

- Wild, C.Y.; Grealish, A.; Hopper, D. Lower Limb and Trunk Biomechanics after Fatigue in Competitive Female Irish Dancers. J. Athl. Train. 2017, 52, 643–648. [CrossRef]

- Azevedo, A.M.; Oliveira, R.; Vaz, J.R.; Cortes, N. Professional Dancers Distinct Biomechanical Pattern during Multidirectional Landings. Med. Sci. Sports Exerc. 2019, 51, 539–547. [CrossRef]

- Azevedo, A.M.; Oliveira, R.; Vaz, J.R.; Cortes, N. Oxford Foot Model Kinematics in Landings: A Comparison between Professional Dancers and Non-Dancers. J. Sci. Med. Sport 2020, 23, 347–352. [CrossRef]

- Self, B.P.; Paine, D. Ankle Biomechanics during Four Landing Techniques. Med. Sci. Sport. Exerc. 2001, 33, 1338–1344.

- Blackburn, J.T.; Padua, D.A. Sagittal-Plane Trunk Position, Landing Forces, and Quadriceps Electromyographic Activity. J. Athl. Train. 2009, 44, 174–179. [CrossRef]

- Devita, P.; Skelly, W. Effect of Landing Stiffness on Joint Kinetics and Energetics in the Lower Extremity. Med. Sci. Sports Exerc. 1992, 24, 108–115.

- Saunier, J.; Chapurlat, R. Stress Fracture in Athletes. Jt. Bone Spine 2018, 85, 307–310. [CrossRef]

- Abbott, A.; Bird, M.L.; Wild, E.; Brown, S.M.; Stewart, G.; Mulcahey, M.K. Part I: Epidemiology and Risk Factors for Stress Fractures in Female Athletes. Phys. Sportsmed. 2020, 48, 17–24. [CrossRef]

- Goulart, M.; O’Malley, M.J.; Hodgkins, C.W.; Charlton, T.P. Foot and Ankle Fractures in Dancers. Clin. Sports Med. 2008, 27, 295–304. [CrossRef]

- Trégouët, P.; Merland, F. The Effects of Different Shoes on Plantar Forces in Irish Dance. J. Danc. Med. Sci. 2013, 17, 41–46.

- Ahonen, J. Biomechanics of the Foot in Dance A Literature Review. J. Danc. Med. Sci. 2008, 12, 99–108.

- Cimelli, S.N.; Curran, S.A. Influence of Turnout on Foot Posture and Its Relationship to Overuse Musculoskeletal Injury in Professional Contemporary Dancers: A Preliminary Investigation. J. Am. Podiatr. Med. Assoc. 2012, 102, 25–33. [CrossRef]

- Gabbett, T.J. The Training-Injury Prevention Paradox: Should Athletes Be Training Smarter and Harder? Br. J. Sports Med. 2016, 50, 273–280. [CrossRef]

- Wyon, M. Preparing to Perform: Periodization and Dance. J. Dance Med. Sci. 2010, 14, 67–72.

- Gabbe, B.J.; Finch, C.; Bennell, K.L.; Wajswelner, H. How Valid Is a Self Reported 12 Month Sports Injury History? Br. J. Sports Med. 2003, 37, 545–547. [CrossRef]

- Caine, D.; Goodwin, B.J.; Caine, C.G.; Bergeron, G. Epidemiological Review of Injury in Pre-Professional Ballet Dancers. J. Danc. Med. Sci. 2015, 19, 140–149. [CrossRef]

- Russell, J.A. Preventing Dance Injuries: Current Perspectives. Open access J. Sport. Med. 2013, 4, 199–210. [CrossRef]

- Sobrino, F.J.; de la Cuadra, C.; Guillen, P. Overuse Injuries in Professional Ballet: Injury-Based Differences Among Ballet Disciplines. Orthop. J. Sport. Med. 2015, 3, 1–7. [CrossRef]

- Grove, J.R.; Main, L.C.; Sharp, L. Stressors, Recovery Processes, and Manifestations of Training Distress in Dance. J. Danc. Med. Sci. 2013, 17, 70–78. [CrossRef]

- McEwen, K.; Young, K. Ballet and Pain: Reflections on a Risk-Dance Culture. Qual. Res. Sport. Exerc. Heal. 2011, 3, 152–173. [CrossRef]

- Lampe, J.; Borgetto, B.; Groneberg, D.A.; Wanke, E.M. Prevalence, Localization, Perception and Management of Pain in Dance: An Overview. Scand. J. Pain 2018, 18, 567–574. [CrossRef]

- Bahr, R.; Krosshaug, T. Understanding Injury Mechanisms: A Key Component of Preventing Injuries in Sport. Br. J. Sports Med. 2005, 39, 324–329. [CrossRef]

- Bolling, C.; Mechelen, W. Van; Pasman, H.R.; Verhagen, E. Context Matters : Revisiting the First Step of the ‘ Sequence of Prevention ’ of Sports Injuries. Sport. Med. 2018, 48, 2233–2240. [CrossRef]

- Krosshaug, T.; Andersen, T.E.; Olsen, O.E.O.; Myklebust, G.; Bahr, R. Research Approaches to Describe the Mechanisms of Injuries in Sport: Limitations and Possibilities. Br. J. Sports Med. 2005, 39, 330–339. [CrossRef]

- Bowling, A. Injuries to Dancers: Prevalence, Treatment and Perceptions of Causes. BMJ 1989, 298, 731–734. [CrossRef]

- McCabe, T.R.; Ambegaonkar, J.P.; Redding, E.; Wyon, M. Fit to Dance Survey: A Comparison with Dancesport Injuries. Med. Probl. Perform. Art. 2014, 29, 102–110. [CrossRef]

- Bolling, C.; Mellette, J.; Pasman, H.R.; Van Mechelen, W.; Verhagen, E. From the Safety Net to the Injury Prevention Web: Applying Systems Thinking to Unravel Injury Prevention Challenges and Opportunities in Cirque Du Soleil. BMJ Open Sport Exerc. Med. 2019, 5, 1–9. [CrossRef]

- Bourdon, P.C.; Cardinale, M.; Murray, A.; Gastin, P.; Kellmann, M.; Varley, M.C.; Gabbett, T.J.; Coutts, A.J.; Burgess, D.J.; Gregson, W.; et al. Monitoring Athlete Training Loads: Consensus Statement. Int. J. Sports Physiol. Perform. 2017, 12, 161–170. [CrossRef]

- Halson, S.L. Monitoring Training Load to Understand Fatigue in Athletes. Sport. Med. 2014, 44, 139–147. [CrossRef]

- West, S.W.; Clubb, J.; Torres-Ronda, L.; Howells, D.; Leng, E.; Vescovi, J.D.; Carmody, S.; Posthumus, M.; Dalen-Lorentsen, T.; Windt, J. More than a Metric: How Training Load Is Used in Elite Sport for Athlete Management. Int. J. Sports Med. 2020. [CrossRef]

- Allen, N.; Nevill, A.; Brooks, J.; Koutedakis, Y.; Wyon, M. Ballet Injuries: Injury Incidence and Severity over 1 Year. J. Orthop. Sports Phys. Ther. 2012, 42, 781–790. [CrossRef]

- Ekegren, C.L.; Quested, R.; Brodrick, A. Injuries in Pre-Professional Ballet Dancers: Incidence, Characteristics and Consequences. J. Sci. Med. Sport 2014, 17, 271–275. [CrossRef]

- Eckard, T.G.; Padua, D.A.; Hearn, D.W.; Pexa, B.S.; Frank, B.S. The Relationship Between Training Load and Injury in Athletes: A Systematic Review; Springer International Publishing, 2018; Vol. 48; ISBN 0123456789.

- Gabbett, T.J. Debunking the Myths about Training Load, Injury and Performance: Empirical Evidence, Hot Topics and Recommendations for Practitioners. Br. J. Sports Med. 2020, 54, 58–66. [CrossRef]

- Bittencourt, N.F.N.; Meeuwisse, W.H.; Mendonça, L.D.; Nettel-Aguirre, A.; Ocarino, J.M.; Fonseca, S.T. Complex Systems Approach for Sports Injuries: Moving from Risk Factor Identification to Injury Pattern Recognition - Narrative Review and New Concept. Br. J. Sports Med. 2016, 50, 1309–1314. [CrossRef]

- Bowerman, E.; Whatman, C.; Harris, N.; Bradshaw, E.; Karin, J. Are Maturation, Growth and Lower Extremity Alignment Associated with Overuse Injury in Elite Adolescent Ballet Dancers? Phys. Ther. Sport 2014, 15, 234–241. [CrossRef]

- Johnson, D.M.; Williams, S.; Bradley, B.; Sayer, S.; Murray Fisher, J.; Cumming, S. Growing Pains: Maturity Associated Variation in Injury Risk in Academy Football. Eur. J. Sport Sci. 2020, 20, 544–552. [CrossRef]

- Wik, E.H.; Martínez-Silván, D.; Farooq, A.; Cardinale, M.; Johnson, A.; Bahr, R. Skeletal Maturation and Growth Rates Are Related to Bone and Growth Plate Injuries in Adolescent Athletics. Scand. J. Med. Sci. Sport. 2020, 30, 894–903. [CrossRef]

- Van Der Sluis, A.; Elferink-Gemser, M.T.; Coelho-E-Silva, M.J.; Nijboer, J.A.; Brink, M.S.; Visscher, C. Sport Injuries Aligned to Peak Height Velocity in Talented Pubertal Soccer Players. Int. J. Sports Med. 2014, 35, 351–355. [CrossRef]

- Cahalan, R.; Purtill, H.; O’Sullivan, K. Biopsychosocial Factors Associated with Foot and Ankle Pain and Injury in Irish Dance: A Prospective Study. Med. Probl. Perform. Art. 2017. [CrossRef]

- Campbell, R.S.; Lehr, M.E.; Livingston, A.; McCurdy, M.; Ware, J.K. Intrinsic Modifiable Risk Factors in Ballet Dancers: Applying Evidence Based Practice Principles to Enhance Clinical Applications. Phys. Ther. Sport 2019, 38, 106–114. [CrossRef]

- Kenny, S.J.; Palacios-Derflingher, L.; Shi, Q.; Whittaker, J.L.; Emery, C.A. Association between Previous Injury and Risk Factors for Future Injury in Preprofessional Ballet and Contemporary Dancers. Clin. J. Sport Med. 2017, 29, 209–217. [CrossRef]

- Verhagen, E.; Van Dyk, N.; Clark, N.; Shrier, I. Do Not Throw the Baby out with the Bathwater; Screening Can Identify Meaningful Risk Factors for Sports Injuries. Br. J. Sports Med. 2018, 52, 1223–1224. [CrossRef]

- Meeuwisse, W.H.; Tyreman, H.; Hagel, B.; Emery, C. A Dynamic Model of Etiology in Sport Injury : The Recursive Nature of Risk and Causation. 2007, 17, 215–219.

- Adam, M.U.; Brassington, G.S.; Steiner, H.; Matheson, G.O. Psychological Factors Associated with Performance-Limiting Injuries in Professional Ballet Dancers. J. Danc. Med. Sci. 2004, 8, 43–46.

- Gao, B.; Dwivedi, S.; Milewski, M.D.; Cruz, A.I. Lack of Sleep and Sports Injuries in Adolescents: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. J. Pediatr. Orthop. 2019, 39, e324–e333. [CrossRef]

- Watson, A.M. Sleep and Athletic Performance. Curr. Sports Med. Rep. 2017, 16, 413–418. [CrossRef]

- von Rosen, P.; Frohm, A.; Kottorp, A.; Fridén, C.; Heijne, A. Multiple Factors Explain Injury Risk in Adolescent Elite Athletes: Applying a Biopsychosocial Perspective. Scand. J. Med. Sci. Sport. 2017, 27, 2059–2069. [CrossRef]

- Johnson, M.; Blom, V. Development and Validation of Two Measures of Contingent Self-Esteem. Individ. Differ. Res. 2007, 5, 300–328.

- Elison, J.; Partridge, J. a Relationships between Shame-Coping, Fear of Failure, and Perfectionism in College Athletes. J. Sport Behav. 2012, 35, 19–39.

- Hamilton, L.H.; Solomon, R.; Solomon, J. A Proposal for Standardized Psychological Screening of Dancers. J. Danc. Med. Sci. 2006, 10, 40–45.

- Truong, L.K.; Bekker, S.; Whittaker, J.L. Removing the Training Wheels: Embracing the Social, Contextual and Psychological in Sports Medicine. Br. J. Sports Med. 2020, 0, 1–2. [CrossRef]

- Mainwaring, L.M.; Finney, C. Psychological Risk Factors and Outcomes of Dance Injury A Systematic Review. J. Danc. Med. Sci. 2017, 21, 87–96.

- Truong, L.K.; Mosewich, A.D.; Holt, C.J.; Le, C.Y.; Miciak, M.; Whittaker, J.L. Psychological, Social and Contextual Factors across Recovery Stages Following a Sport-Related Knee Injury: A Scoping Review. Br. J. Sports Med. 2020, 54, 1149–1156. [CrossRef]

- Wiese-Bjornstal, D.M. Psychology and Socioculture Affect Injury Risk, Response, and Recovery in High-Intensity Athletes: A Consensus Statement. Scand. J. Med. Sci. Sport. 2010, 20, 103–111. [CrossRef]

- Kamper, S.J. Types of Research Questions: Descriptive, Predictive, or Causal. J. Orthop. Sports Phys. Ther. 2020, 50, 468–469. [CrossRef]

- Meuli, L.; Dick, F. Understanding Confounding in Observational Studies. Eur. J. Vasc. Endovasc. Surg. 2018, 55, 737. [CrossRef]

- Bahr, R.; Holme, I. Risk Factors for Sports Injuries - A Methodological Approach. Br. J. Sports Med. 2003, 37, 384–392. [CrossRef]

- Nielsen, R.O.; Simonsen, N.S.; Casals, M.; Stamatakis, E.; Mansournia, M.A. Methods Matter and the ‘ Too Much , Too Soon ’ Theory ( Part 2 ): What Is the Goal of Your Sports Injury Research ? Are You Describing , Predicting or Drawing a Causal Inference ? Br J Sport. Med 2020, 0, 2–4.

- Dekkers, O.M.; Vandenbroucke, J.P.; Cevallos, M.; Renehan, A.G.; Altman, D.G.; Egger, M. COSMOS-E: Guidance on Conducting Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses of Observational Studies of Etiology. PLoS Med. 2019, 16, 1–24. [CrossRef]

| Authors | McGuinness et al. (2006) | Cahalan et al. (2013) | Eustergerling et al. (2015) | Cahalan et al. (2015) | Cahalan et al. (2016) | Cahalan, Bargary et al. (2018) | Cahalan, Kearney et al. (2018) | Cahalan, Bargary et al. (2019) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Factors | |||||||||

| Use of split sole sneakers | ↓ | ||||||||

| Cool down | ↓ | = | = | ||||||

| Warm up | ↓ | = | ↑ failure to complete | ||||||

| Cross-training | = | = | = | = | = | ||||

| Dance exposure | = | = | = | ↓ | |||||

| Statistics | Univariate | Univariate | Odds ratios (association) | Univariate, mulivariate | Multivariate | Univariate | Univariate | Multivariate | |

| Level of evidence | 3c | 3c | 3c | 3c | 3b | 3c | 3b | 3b | |

| Authors | McGuinness et al. (2006) | Cahalan et al. (2013) | Eustergerling et al. (2015) | Cahalan et al. (2015) | Cahalan et al. (2016) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Factors | ||||||

| Elite level | ↑ | |||||

| Years dancing/experience | = | ↑ | = | = | ↑ | |

| Sex | = | ↑ ♀ | ||||

| Age | = | ↑ | ↑ | = | ||

| Statistics | Univariate | Univariate | Odds ratios (association) | Univariate, mulivariate | Multivariate | |

| Level of evidence | 3c | 3c | 3c | 3c | 3b | |

| Authors | McGuinness et al. (2006) | Cahalan et al. (2013) | Eustergerling et al. (2015) | Cahalan et al. (2015) | Cahalan et al. (2016) | Cahalan, Bargary et al. (2018) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Factors | |||||||

| Psychological problems/complains | ↑ | ↑ | = | ||||

| Lower mood | ↑ | = | = | ||||

| Higher catastrophizing | ↑ | = | = | ||||

| Higher levels of anger-hostility | = | ↑ | ↑ | ||||

| Statistics | Univariate | Univariate | Odds ratios (association) | Univariate, mulivariate | Multivariate | Univariate | |

| Level of evidence | 3c | 3c | 3c | 3c | 3b | 3c | |

| Authors | Cahalan et al. (2013) | Cahalan et al. (2015) | Cahalan et al. (2016) | Cahalan, Bargary et al. (2018) | Cahalan, Kearney et al. (2018) | Cahalan, Bargary et al. (2019) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Factors | |||||||

| Higher nr of subjective health complaints | ↑ | ↑ | = | ||||

| A higher level of general everyday pain | ↑ | ||||||

| More body parts affected by pain/injury | ↑ | ↑ | ↑ | ||||

| Always/often dancing in pain | = | ↑ | ↑ | ||||

| Insufficient/poor sleep | ↑ | ↓ better sleep | = | ||||

| General health scores | ↓ | ||||||

| Nr of weeks participants reported poor/very poor general health | ↑ | ||||||

| Statistics | Univariate | Univariate, mulivariate | Multivariate | Univariate | Univariate | Multivariate | |

| Level of evidence | 3c | 3c | 3b | 3c | 3b | 3b | |

| Authors | Cahalan et al. (2015) | Cahalan et al. (2016) | Cahalan, Bargary et al. (2018) | Cahalan, Bargary et al. (2019) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Factors | |||||

| Physical screening tests | = | = | = | ||

| Change in weight or height | = | ||||

| Statistics | Univariate mulivariate |

Multivariate | Univariate | Multivariate | |

| Level of evidence | 3c | 3b | 3c | 3b | |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).