Submitted:

31 March 2023

Posted:

03 April 2023

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Results

2.1. Developmental assays of leb-2 GFP-h

2.2. Microscopic characterization of the ER-defective plants

2.3. SP-PSIA/B–mCherry transient expression in the mutated plants

2.4. Endogenous Arabidopsis Aspartic proteinases analysis

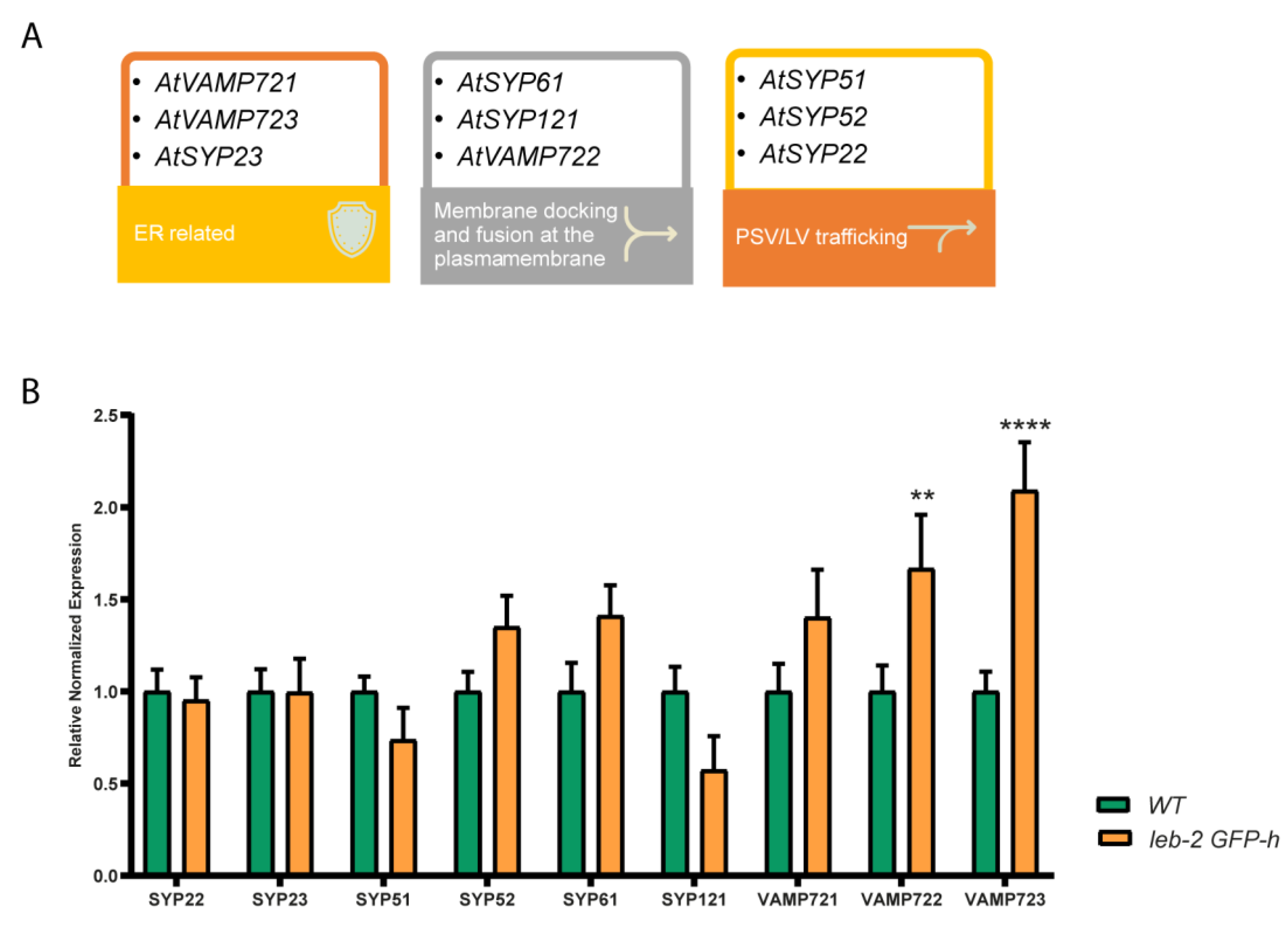

2.5. Endomembrane genes expression testing

3. Discussion

3.1. The leb-2 GFP-h Arabidopsis mutant

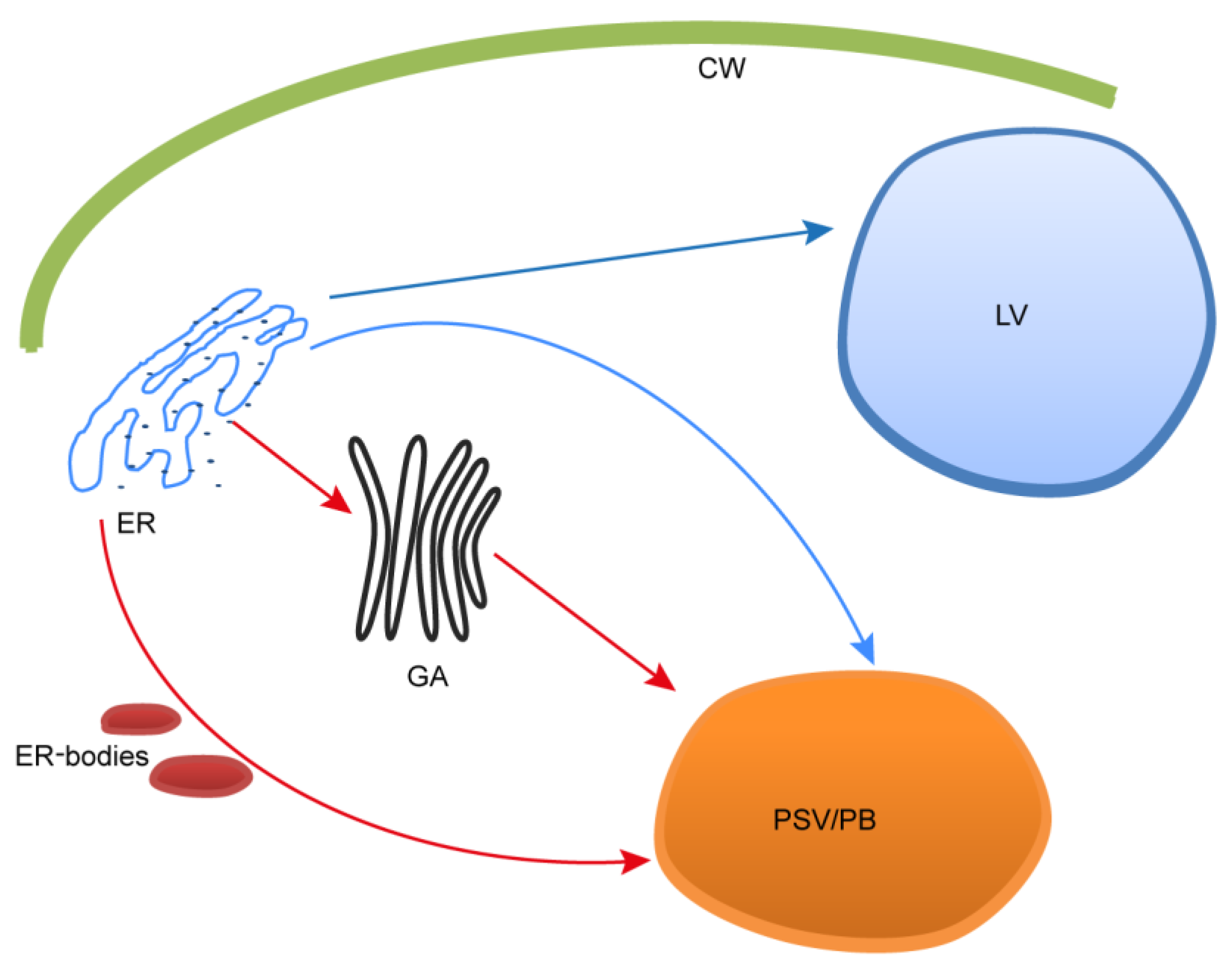

3.2. PSIs-mediated sorting and unconventional routes

3.3. Endomembrane system effectors expression level analysis

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Biological Material

4.2. Transmission Electron Microscopy (TEM)

4.2. Transient Transformation of Arabidopsis thaliana Seedlings through Vacuum Infiltration

4.2. Transformation of Arabidopsis thaliana for stable expression

4.2. Drug Treatment Assays

4.2. CLSM Analysis

4.2. cDNA Preparation

4.2. Gene Selection

4.2. Quantitative RT-PCR

Supplementary Material

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Morita, M.T.; Shimada, T. The Plant Endomembrane System—A Complex Network Supporting Plant Development and Physiology. Plant Cell Physiol. 2014, 55, 667–671. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cevher-Keskin, B. Endomembrane Trafficking in Plants. Electrodialysis 2020, 1–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frigerio, L.; Hawes, C. The endomembrane system: A green perspective. Traffic 2008, 9, 1563. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stefano, G.; Hawes, C.; Brandizzi, F. ER - the key to the highway. Curr. Opin. Plant Biol. 2014, 22, 30–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Chung, K.P.; Lin, W.; Jiang, L. Protein secretion in plants: Conventional and unconventional pathways and new techniques. J. Exp. Bot. 2018, 69, 21–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Xu, M.; Gao, C.; Zeng, Y.; Cui, Y.; Shen, W.; Jiang, L. The roles of endomembrane trafficking in plant abiotic stress responses. J. Integr. Plant Biol. 2020, 62, 55–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Staehelin, L.A. The plant ER: a dynamic organelle composed of a large number of discrete functional domains. Plant J. 1997, 11, 1151–1165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stefan, C.J.; Manford, A.G.; Emr, S.D. ER-PM connections: Sites of information transfer and inter-organelle communication. Curr. Opin. Cell Biol. 2013, 25, 434–442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stefano, G.; Renna, L.; Lai, Y.; Slabaugh, E.; Mannino, N.; Buono, R.A.; Otegui, M.S.; Brandizzi, F. ER network homeostasis is critical for plant endosome streaming and endocytosis. Cell Discov. 2015, 1, 15033. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nakano, R.T.; Matsushima, R.; Ueda, H.; Tamura, K.; Shimada, T.; Li, L.; Hayashi, Y.; Kondo, M.; Nishimura, M.; Hara-Nishimura, I. GNOM-LIKE1/ERMO1 and SEC24a/ERMO2 Are Required for Maintenance of Endoplasmic Reticulum Morphology in Arabidopsis thaliana. Plant Cell 2009, 21, 3672–3685. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quader, H.; Schnepf, E. Endoplasmic reticulum and cytoplasmic streaming: Fluorescence microscopical observations in adaxial epidermis cells of onion bulb scales. Protoplasma 1986, 131, 250–252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matsushima, R.; Hayashi, Y.; Yamada, K.; Shimada, T.; Nishimura, M.; Hara-Nishimura, I. The ER Body, a Novel Endoplasmic Reticulum-Derived Structure in Arabidopsis. Plant Cell Physiol. 2003, 44, 661–666. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hara-Nishimura, I.; Matsushima, R.; Shimada, T.; Nishimura, M. Diversity and Formation of Endoplasmic Reticulum-Derived Compartments in Plants. Are These Compartments Specific to Plant Cells? Plant Physiol. 2004, 136, 3435–3439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sampaio, M.; Neves, J.; Cardoso, T.; Pissarra, J.; Pereira, S.; Pereira, C. Coping with Abiotic Stress in Plants—An Endomembrane Trafficking Perspective. Plants 2022, 11, 1–15, doi:https://www.mdpi.com/2223-7747/11/3/338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Marcos Lousa, C.; Gershlick, D.C.; Denecke, J. Mechanisms and Concepts Paving the Way towards a Complete Transport Cycle of Plant Vacuolar Sorting Receptors. Plant Cell 2012, 24, 1714–1732. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rojo, E.; Denecke, J. What is moving in the secretory pathway of plants? Plant Physiol. 2008, 147, 1493–503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olbrich, A.; Hillmer, S.; Hinz, G.; Oliviusson, P.; Robinson, D.G. Newly formed vacuoles in root meristems of barley and pea seedlings have characteristics of both protein storage and lytic vacuoles. Plant Physiol. 2007, 145, 1383–1394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paris, N.; Stanley, C.M.; Jones, R.L.; Rogers, J.C. Plant Cells Contain Two Functionally Distinct Vacuolar Compartments. Cell 1996, 85, 563–572. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramalho-Santos, M.; Verissimo, P.; Cortes, L.; Samyn, B.; Van Beeumen, J.; Pires, E.; Faro, C. Identification and proteolytic processing of procardosin A. Eur. J. Biochem. 1998, 255, 133–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vieira, M.; Pissarra, J.; Veríssimo, P.; Castanheira, P.; Costa, Y.; Pires, E.; Faro, C. Molecular cloning and characterization of cDNA encoding cardosin B, an aspartic proteinase accumulating extracellularly in the transmitting tissue of Cynara cardunculus L. Plant Mol. Biol. 2001, 45, 529–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramalho-Santos, M.; Pissarra, J.; Veríssimo, P.; Pereira, S.; Salema, R.; Pires, E.; Faro, C.J. Cardosin A, an abundant aspartic proteinase, accumulates in protein storage vacuoles in the stigmatic papillae of Cynara cardunculus L. Planta 1997, 203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pissarra, J.; Pereira, C.; Soares, D.; Figueiredo, R.; Duarte, P.; Teixeira, J.; Pereira, S. From Flower to Seed Germination in Cynara cardunculus : A Role for Aspartic Proteinases. Int. J. Plant Dev. Biol. 2007, 1, 274–281. [Google Scholar]

- Pereira, C.S.; da Costa, D.S.; Pereira, S.; de Moura Nogueira, F.; Albuquerque, P.M.; Teixeira, J.; Faro, C.; Pissarra, J. Cardosins in postembryonic development of cardoon: towards an elucidation of the biological function of plant aspartic proteinases. Protoplasma 2008, 232, 203–213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oliveira, A.; Pereira, C.; Costa, D.S. d. D.S. da; Teixeira, J.; Fidalgo, F.; Pereira, S.; Pissarra, J. Characterization of aspartic proteinases in C. cardunculus L. callus tissue for its prospective transformation. Plant Sci. 2010, 178, 140–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duarte, P.; Pissarra, J.; Moore, I. Processing and trafficking of a single isoform of the aspartic proteinase cardosin A on the vacuolar pathway. Planta 2008, 227, 1255–1268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pereira, C.; Pereira, S.; Satiat-Jeunemaitre, B.; Pissarra, J. Cardosin A contains two vacuolar sorting signals using different vacuolar routes in tobacco epidermal cells. Plant J. 2013, n/a–n/a. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- da Costa, D.S.; Pereira, S.; Moore, I.; Pissarra, J. Dissecting cardosin B trafficking pathways in heterologous systems. Planta 2010, 232, 1517–1530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simões, I.; Faro, C. Structure and function of plant aspartic proteinases. Eur. J. Biochem. 2004, 271, 2067–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Soares, A.; Ribeiro Carlton, S.M.; Simões, I. Atypical and nucellin-like aspartic proteases: emerging players in plant developmental processes and stress responses. J. Exp. Bot. 2019, 70, 2059–2076. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Egas, C.; Lavoura, N.; Resende, R.; Brito, R.M.M.; Pires, E.; de Lima, M.C.P.; Faro, C. The Saposin-like Domain of the Plant Aspartic Proteinase Precursor Is a Potent Inducer of Vesicle Leakage. J. Biol. Chem. 2002, 275, 38190–38196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Terauchi, K.; Asakura, T.; Ueda, H.; Tamura, T.; Tamura, K.; Matsumoto, I.; Misaka, T.; Hara-Nishimura, I.; Abe, K. Plant-specific insertions in the soybean aspartic proteinases, soyAP1 and soyAP2, perform different functions of vacuolar targeting. J. Plant Physiol. 2006, 163, 856–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- De Moura, D.C.; Bryksa, B.C.; Yada, R.Y. In silico insights into protein-protein interactions and folding dynamics of the saposin-like domain of Solanum tuberosum aspartic protease. PLoS One 2014, 9, 18–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Frey, M.E.; D’Ippolito, S.; Pepe, A.; Daleo, G.R.; Guevara, M.G. Transgenic expression of plant-specific insert of potato aspartic proteases (StAP-PSI) confers enhanced resistance to Botrytis cinerea in Arabidopsis thaliana. Phytochemistry 2018, 149, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muñoz, F.; Palomares-Jerez, M.F.; Daleo, G.; Villalaín, J.; Guevara, M.G. Possible mechanism of structural transformations induced by StAsp-PSI in lipid membranes. Biochim. Biophys. Acta - Biomembr. 2014, 1838, 339–347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Caroli, M.; Lenucci, M.S.; Di Sansebastiano, G.-P.; Dalessandro, G.; De Lorenzo, G.; Piro, G. Protein trafficking to the cell wall occurs through mechanisms distinguishable from default sorting in tobacco. Plant J. 2011, 65, 295–308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Marchis, F.; Bellucci, M.; Pompa, A. Unconventional pathways of secretory plant proteins from the endoplasmic reticulum to the vacuole bypassing the Golgi complex. Plant Signal. Behav. 2013, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stigliano, E.; Faraco, M.; Neuhaus, J.-M.M.; Montefusco, A.; Dalessandro, G.; Piro, G.; Di Sansebastiano, G.-P. Pietro Two glycosylated vacuolar GFPs are new markers for ER-to-vacuole sorting. Plant Physiol. Biochem. 2013, 73, 337–343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sansebastiano, G.P. Di; Barozzi, F.; Piro, G.; Denecke, J.; Lousa, C.D.M. Trafficking routes to the plant vacuole: Connecting alternative and classical pathways. J. Exp. Bot. 2018, 69, 79–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vieira, V.; Peixoto, B.; Costa, M.; Pereira, S.; Pissarra, J.; Pereira, C. N-linked glycosylation modulates Golgi-independent vacuolar sorting mediated by the plant specific insert. Plants 2019, 8, 1–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nagano, A.J.; Maekawa, A.; Nakano, R.T.; Miyahara, M.; Higaki, T.; Kutsuna, N.; Hasezawa, S.; Hara-Nishimura, I. Quantitative analysis of ER body morphology in an arabidopsis mutant. Plant Cell Physiol. 2009, 50, 2015–2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nebenführ, A.; Ritzenthaler, C.; Robinson, D.G. Brefeldin A: Deciphering an enigmatic inhibitor of secretion. Plant Physiol. 2002, 130, 1102–1108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Caroli, M.; Barozzi, F.; Renna, L.; Piro, G.; Di Sansebastiano, G. Pietro Actin and microtubules differently contribute to vacuolar targeting specificity during the export from the er. Membranes (Basel). 2021, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matsushima, R.; Kondo, M.; Nishimura, M.; Hara-Nishimura, I. A novel ER-derived compartment, the ER body, selectively accumulates a β-glucosidase with an ER-retention signal in Arabidopsis. Plant J. 2003, 33, 493–502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Boyes, D.C.; Zayed, A.M.; Ascenzi, R.; McCaskill, A.J.; Hoffman, N.E.; Davis, K.R.; Görlach, J. Growth Stage–Based Phenotypic Analysis of Arabidopsis: A Model for High Throughput Functional Genomics in Plants. Plant Cell 2001, 13, 1499–1510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Faro, C.; Gal, S. Aspartic Proteinase Content of the Arabidopsis Genome. Curr. Protein Pept. Sci. 2005, 6, 493–500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, X.; Pfeil, J.E.; Gal, S. The three typical aspartic proteinase genes of Arabidopsis thaliana are differentially expressed. Eur. J. Biochem. 2002, 269, 4675–4684. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ito, Y.; Uemura, T.; Nakano, A. Formation and maintenance of the golgi apparatus in plant cells, 1st ed.; Elsevier Inc., 2014; Vol. 310, ISBN 9780128001806. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, B.; Karnik, R.; Wang, Y.; Wallmeroth, N.; Blatt, M.R.; Grefen, C. The arabidopsis R-SNARE VAMP721 interacts with KAT1 and KC1 K+ channels to moderate K+ current at the plasma membrane. Plant Cell 2015, 27, 1697–1717. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, L.; Zhang, H.; Liu, P.; Hao, H.; Jin, J.B.; Lin, J. Arabidopsis R-SNARE Proteins VAMP721 and VAMP722 Are Required for Cell Plate Formation. PLoS One 2011, 6, e26129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laloux, T.; Matyjaszczyk, I.; Beaudelot, S.; Hachez, C.; Chaumont, F. Interaction Between the SNARE SYP121 and the Plasma Membrane Aquaporin PIP2;7 Involves Different Protein Domains. Front. Plant Sci. 2021, 11, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hachez, C.; Laloux, T.; Reinhardt, H.; Cavez, D.; Degand, H.; Grefen, C.; De Rycke, R.; Inzé, D.; Blatt, M.R.; Russinova, E.; et al. Arabidopsis SNAREs SYP61 and SYP121 coordinate the trafficking of plasma membrane aquaporin PIP2;7 to modulate the cell membrane water permeability. Plant Cell 2014, 26, 3132–3147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bassham, D.C.; Blatt, M.R. SNAREs: cogs and coordinators in signaling and development. Plant Physiol. 2008, 147, 1504–1515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bernat-Silvestre, C.; De Sousa Vieira, V.; Sánchez-Simarro, J.; Aniento, F.; Marcote, M.J. Transient Transformation of A. thaliana Seedlings by Vacuum Infiltration BT - Arabidopsis Protocols. In Methods in Molecular Biology; Sanchez-Serrano, J.J., Salinas, J., Eds.; Springer US: New York, NY, 2021; ISBN 978-1-0716-0880-7. [Google Scholar]

- Clough, S.J.; Bent, A.F. Floral dip: A simplified method for Agrobacterium-mediated transformation of Arabidopsis thaliana. Plant J. 1998, 16, 735–743. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Czechowski, T.; Stitt, M.; Altmann, T.; Udvardi, M.K.; Scheible, W.R. Genome-wide identification and testing of superior reference genes for transcript normalization in arabidopsis. Plant Physiol. 2005, 139, 5–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- TAIR - Home Page.

- De Benedictis, M.; Bleve, G.; Faraco, M.; Stigliano, E.; Grieco, F.; Piro, G.; Dalessandro, G.; Di Sansebastiano, G. Pietro AtSYP51/52 functions diverge in the post-golgi traffic and differently affect vacuolar sorting. Mol. Plant 2013, 6, 916–930. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hachez, C.; Laloux, T.; Reinhardt, H.; Cavez, D.; Degand, H.; Grefen, C.; De Rycke, R.; Inzé, D.; Blatt, M.R.; Russinova, E.; et al. Arabidopsis SNAREs SYP61 and SYP121 coordinate the trafficking of plasma membrane aquaporin PIP2;7 to modulate the cell membrane water permeability. Plant Cell 2014, 26, 3132–3147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Eisenach, C.; Chen, Z.H.; Grefen, C.; Blatt, M.R. The trafficking protein SYP121 of Arabidopsis connects programmed stomatal closure and K+ channel activity with vegetative growth. Plant J. 2012, 69, 241–251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shirakawa, M.; Ueda, H.; Shimada, T.; Koumoto, Y.; Shimada, T.L.; Kondo, M.; Takahashi, T.; Okuyama, Y.; Nishimura, M.; Hara-Nishimura, I. Arabidopsis Qa-SNARE SYP2 proteins localized to different subcellular regions function redundantly in vacuolar protein sorting and plant development. Plant J. 2010, 64, 924–935. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kwon, C.; Bednarek, P.; Schulze-Lefert, P. Secretory pathways in plant immune responses. Plant Physiol. 2008, 147, 1575–1583. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kwon, C.; Neu, C.; Pajonk, S.; Yun, H.S.; Lipka, U.; Humphry, M.; Bau, S.; Straus, M.; Kwaaitaal, M.; Rampelt, H.; et al. Co-option of a default secretory pathway for plant immune responses. Nature 2008, 451, 835–840. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neves, J.; Sampaio, M.; Séneca, A.; Pereira, S.; Pissarra, J.; Pereira, C. Abiotic Stress Triggers the Expression of Genes Involved in Protein Storage Vacuole and Exocyst-Mediated Routes. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021, 22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neves, J.; Monteiro, J.; Sousa, B.; Soares, C.; Pereira, S.; Fidalgo, F.; Pissarra, J.; Pereira, C. Relevance of the Exocyst in Arabidopsis exo70e2 Mutant for Cellular Homeostasis under Stress. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023, Vol. 24, Page 424 2022, 24, 424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Genes | Identifier | Role and Localisation | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|

| AtSAND-1 | AT2G28390 | Housekeeping gene. | [55,56] |

| AtGAPDH | AT1G13440 | Housekeeping gene. | [55,56] |

| AtUBC9 | AT4G27960 | Housekeeping gene. | [55,56] |

| AtSYP51 | AT1G16240.1 | Transport to the PSV, vesicle docking and fusion. Enables SNAP receptor activity, SNARE binding and protein binding. Interacts with VTI12. | [56,57] |

| AtSYP121 | AT3G11820.1 | Syntaxin found in the plasma membrane. Capable of forming a complex with SYP51 and VTI11. | [58,59] |

| AtSYP23 | AT4G17730.2 | Transmembrane domain-free cytosolic syntaxin. Role in transport vesicles docking or fusion with the prevacuolar membrane, enabling SNAP receptor activity and SNARE binding. | [56,60] |

| AtVAMP723 | AT2G33110.1 | Found in the endoplasmic reticulum. Directs transport vesicles towards their intended membrane and/or fusing them there. | [48] |

| AtSYP22 | AT5G46860.1 | Syntaxin-related protein necessary for vacuolar assembly. Localized in the vacuolar membranes, late endosome and trans-Golgi network (TGN) transport vesicles. | [56,60] |

| AtVAMP722 | AT2G33120.2 | Directs transport vesicles towards their intended membrane and/or fusing them there. Response to biotic stress. Outlines a complex that includes SYP121. | [61,62] |

| AtVAMP721 | AT1G04750 | Involved in TGN/early endosome mediated secretory trafficking to the plasma membrane, contributing to cell plate formation. | [48,49] |

| AtSYP61 | AT1G28490.1 | Vesicle trafficking protein. Along with SYP121, coordinates plasma membrane aquaporin PIP2;7 trafficking to modulate membrane water permeability. Complexes with VTI12. | [56,58] |

| AtSYP52 | AT1G79590.2 | Localized to TGN/vacuole, participates in the route to the Lytic vacuole and complexes with VTI11. | [56,57] |

| AtAP1 | AT1G11910 | Saposin-like aspartyl protease with a PSI domain, located along the secretory pathway. | [56] |

| AtAP2 | AT1G62290 | Saposin-like aspartyl protease with a PSI domain, located in the vacuole and secretory vesicles. | [56] |

| AtAP3 | AT4G04460 | Saposin-like aspartyl protease with a PSI domain, secreted to the extracellular region. | [56] |

| Genes | Primer Forward | Primer Reverse |

|---|---|---|

| SAND1 | AACTCTATGCAGCATTTGATCCACT | TGATTGCATATCTTTATCGCCATC |

| GAPDH1 | TTGGTGACAACAGGTCCAAGCA | AAACTTGTCGCTCAATGCAATC |

| UBC91 | TCACAATTTCCAAGGTGCTGC | TCATCTGGGTTTGGATCCGT |

| SYP51 | TGGCGTCTTCATCGGATTCATGG | AGCTGAAGCACGACGCTGAGCA |

| SYP121 | TCCTCCGATCGAACCAGGACCTC | TTCTCGCCGGTGACGGTGAA |

| SYP23 | GCAGCGTGCCCTTCTTGTGG | TCCTTGGGCAGTTGCAGCGTA |

| VAMP723 | CCCGTGGTGTGATATGTGAG | CCACAAACCGAGAGGATGAT |

| SYP22 | CGAGGAAATTCAATGGTGGT | ACGTGGAGACTCCGGTATTG |

| VAMP722 | CAATTTGTGGGGGATTCAAC | GATCTTGGGAAGCACAGAGC |

| SYP61 | TTGAAAAACGGAGGAGATGG | TTCACTTGCATGACCTGCTC |

| SYP52 | ATGTGGTGGCAACTTGTGAA | CTTTGCCTCACAGACACGAA |

| AtAP1 | GGCATTGAGTCGGTGGTGGACA | TCTCACATGCAGAACACGCAGCA |

| AtAP2 | GGGGATTGAATCGGTGGTGGA | ACATGCAGGACAACCCGCGTCT |

| AtAP3 | TGCAAGGCCGTGGTGGATCA | GCGCAGACTCCAATTTGTGAGCA |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).