Submitted:

16 March 2023

Posted:

20 March 2023

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

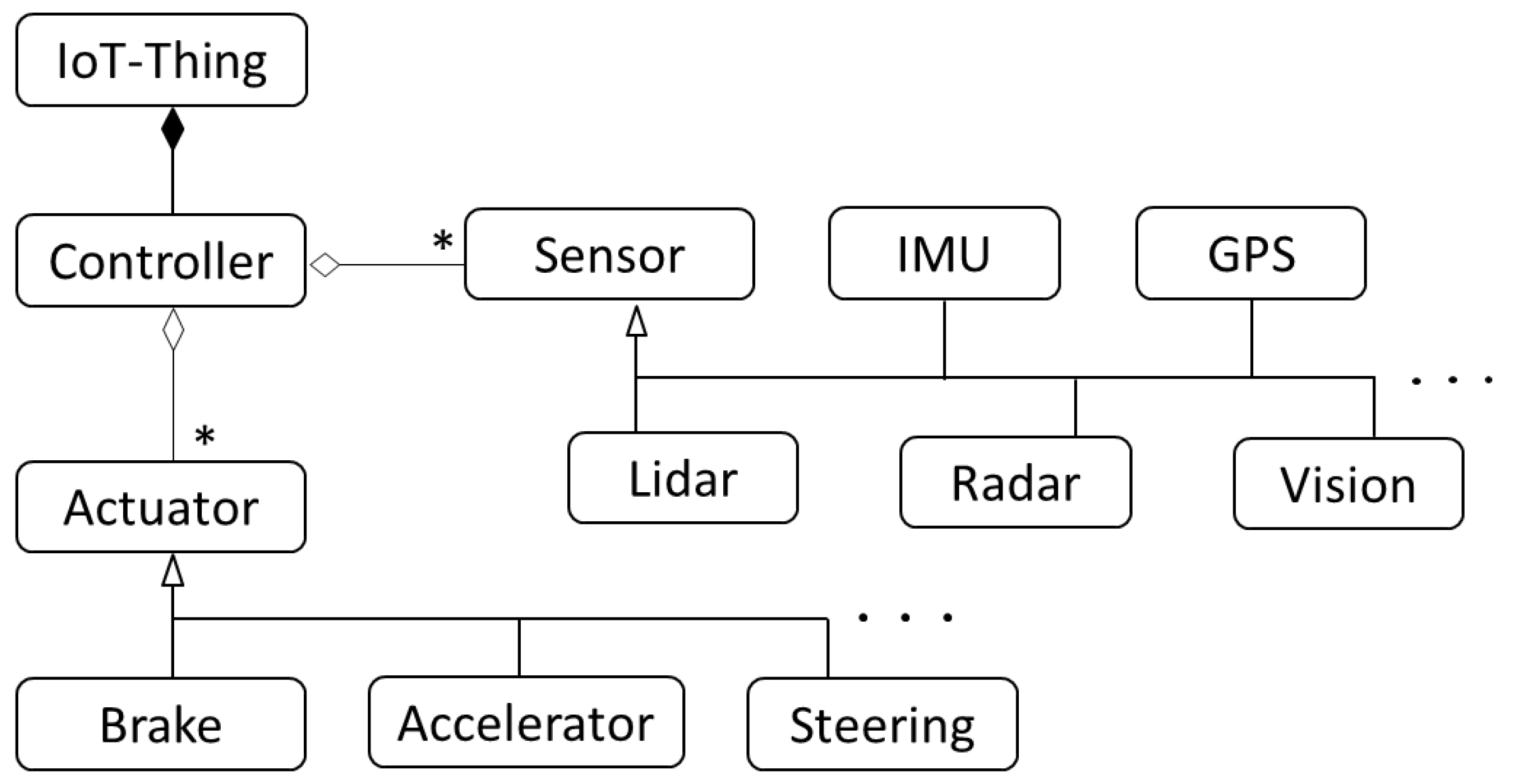

- AEPs for sensors and actuators. These patterns are paradigms for any concrete type of sensor or actuator, from which concrete patterns can be derived.

- Two concrete patterns derived from these AEPs: the Lidar Sensor and the Brake Actuator.

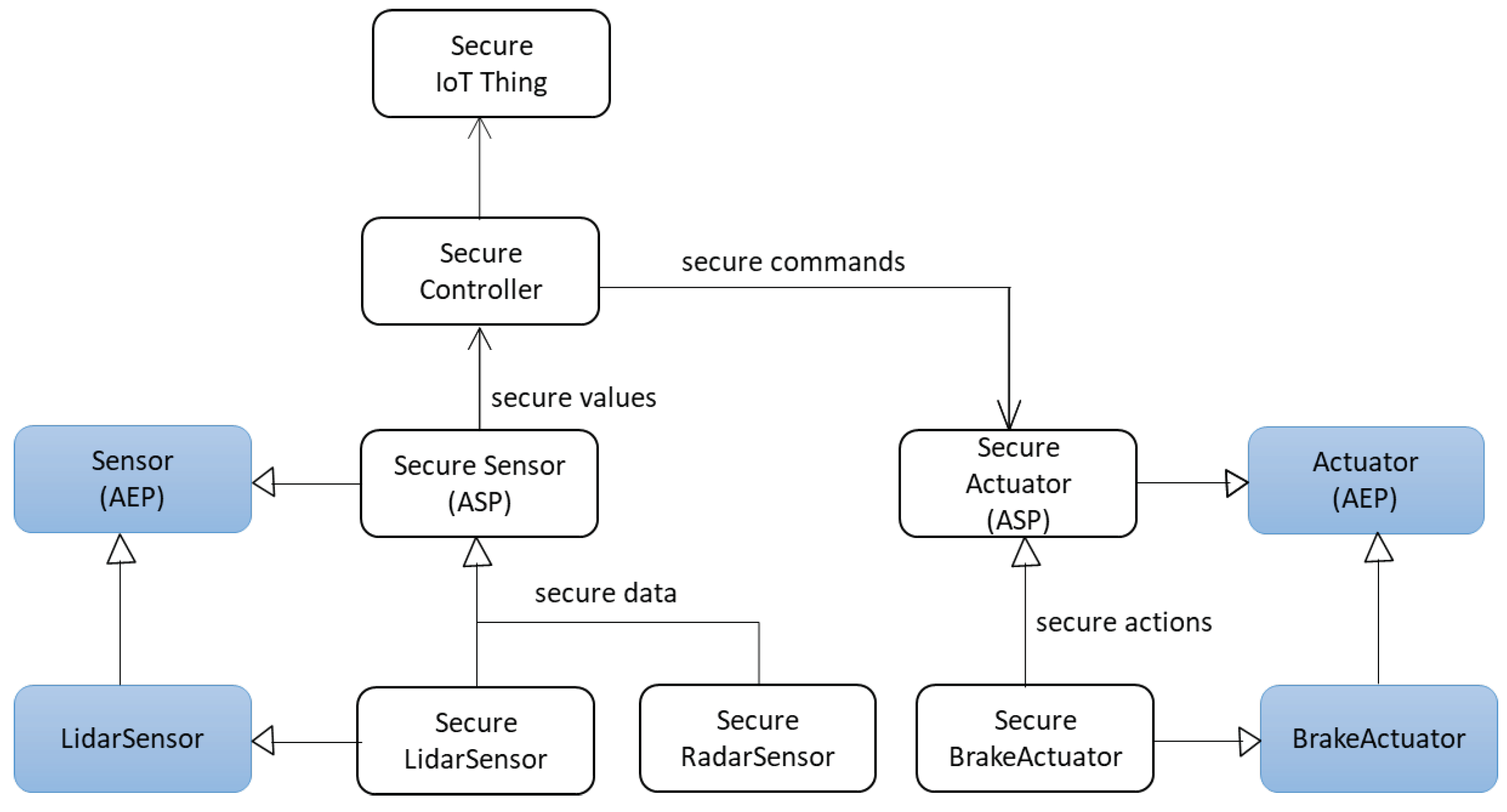

- The structure and behavior of the ESFs for sensors and actuators. These ESFs are the basis for SSFs, secure units that can be applied in the design of a variety of CPSs.

- A validation of the functional correctness of these AEPs and of their derived patterns.

- A roadmap to derive concrete security patterns for sensors and actuators and build the corresponding SSFs.

2. Background

2.1. Cyber-Physical Systems (CPSs) and Internet of Things (IoT)

2.2. Autonomous Cars

2.3. Patterns

2.4. Security Solution Frames (SSFs)

3. Abstract Entity Patterns for Sensors and Actuators

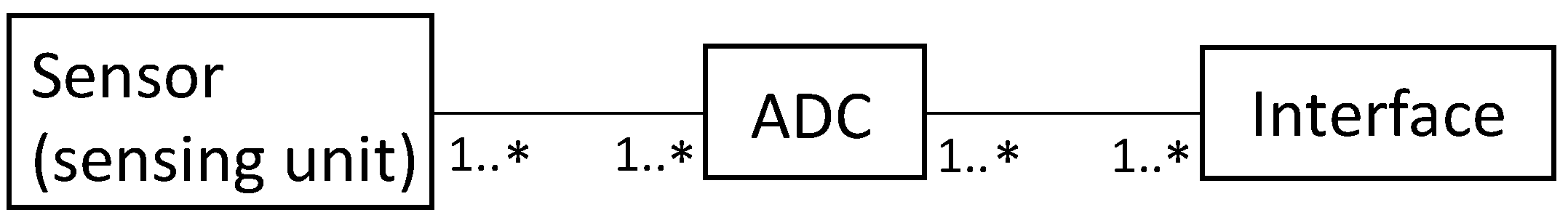

3.1. Abstract Entity Sensor [3]

3.1.1. Intent

3.1.2. Context

3.1.3. Problem

- The measuring devices must collect physical values from their environment.

- The collected values should be able to be converted to digital data.

- The data collected must be sent accurately to a designated destination or stored.

- The device must have a sufficient amount of resources, such as computational capacity, power supply (battery life), etc.

- There is a need to collect data from different types and numbers of devices. Complex systems need a variety of measurements.

- Devices used for data collection should not be very expensive, which would increase the cost of the systems that use them.

3.1.4. Solution

3.1.5. Known Uses

3.1.6. Consequences

- Sensors can collect physical values from their environment.

- Sensors have their own ADCs to convert information into digital data.

- Sensors have interfaces, and data collected by sensors can be sent accurately to a designated destination.

- Sensors have power supplies and may use them only when required. Sensor technologies have increased due to the inexpensive availability of computational resources.

- Various systems/applications use different types and numbers of sensors and collect data; however, sensor fusion technology can combine sensory data from disparate sources.

- Elaborated sensors are more expensive; their use must be justified by need.

- Since sensors may collect any activities around them, their use can raise concerns over the privacy of individuals. This point depends on the type of sensor.

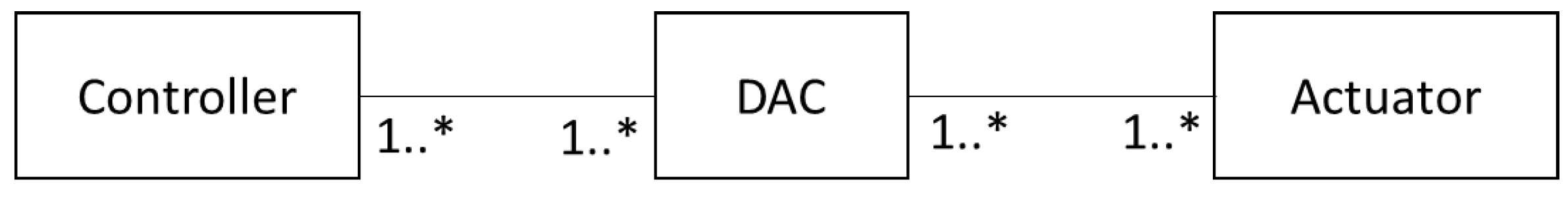

3.2. Abstract Entity Actuator

3.2.1. Intent

3.2.2. Context

3.2.3. Problem

- Command faithfulness: Commands sent by controllers must be faithfully executed.

- Resource availability: There must be enough resources, e.g., batteries, to perform the actions.

- Functional availability: Systems must be available to act when needed.

- Action variety: There must be ways to perform different varieties of actions according to the needs of applications.

- Power heterogeneity: Different types of actions (electric, hydraulic, pneumatic) require different sources of power, such as electric or hydraulic power.

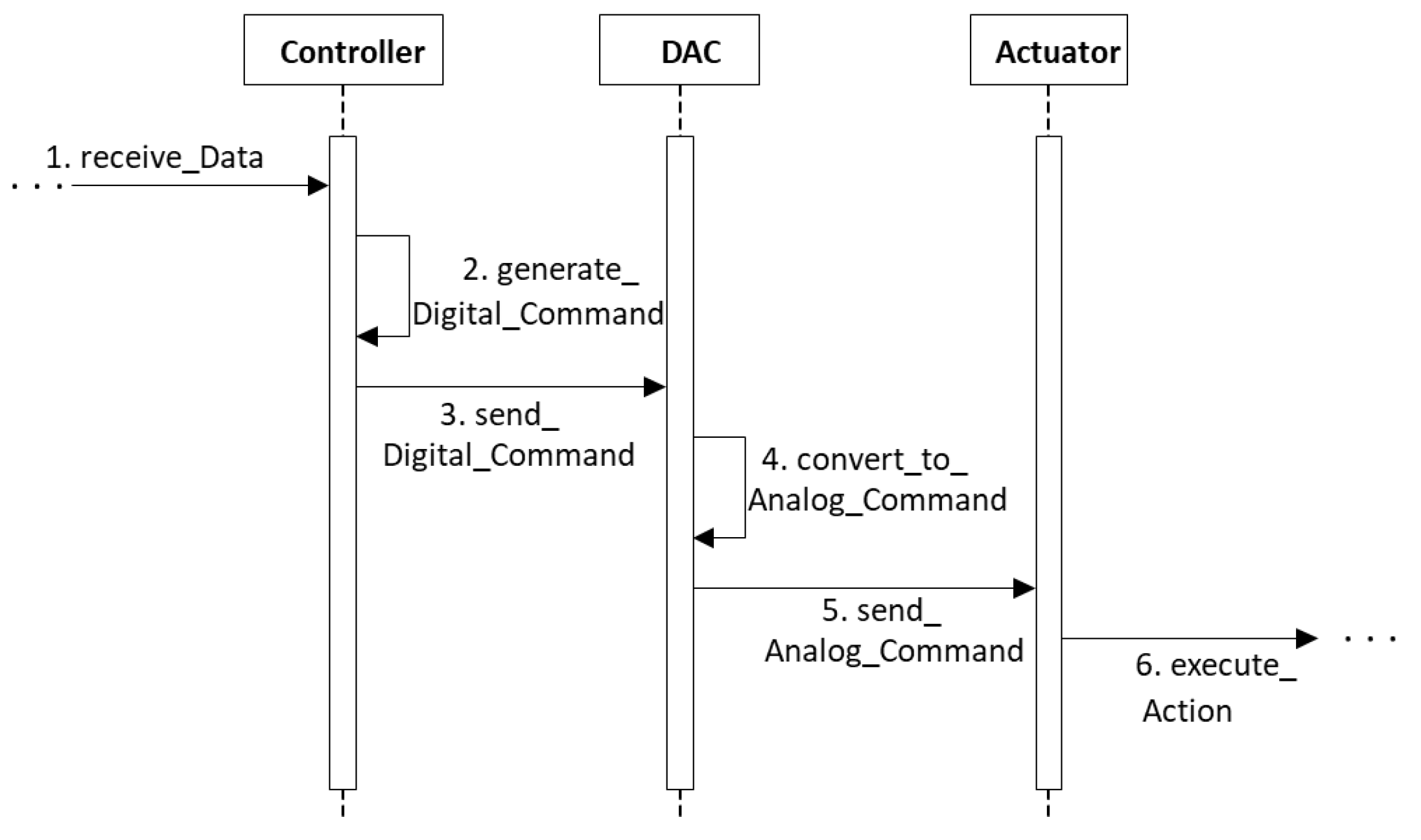

3.2.4. Solution

- The controller receives data with instructions for physical actions.

- The controller generates digital commands.

- The controller sends digital commands to the DAC.

- The DAC converts these digital commands into analog commands

- The DAC sends the analog commands to the actuator.

- The actuator executes the requested physical action.

3.2.5. Known Uses

3.2.6. Consequences

- Actuators include mechanisms to perform physical actions following commands.

- Actuators can be provided with enough resources to perform their work, such as electrical power, fuel, or hydraulic/pneumatic energy.

- Different sources of power can be used in the actuators to perform different types of action. For example, electrically driven actuators may use power from the electricity grid [17]

- It is possible to build actuators appropriate for different types of applications.

- This pattern has the following disadvantages:

- Inexpensive concrete actuators may have limited resources and cannot perform elaborate commands, they may not meet design constraints on mass and volume. Advanced actuators may be costly.

4. Concrete Patterns for Sensors and Actuators

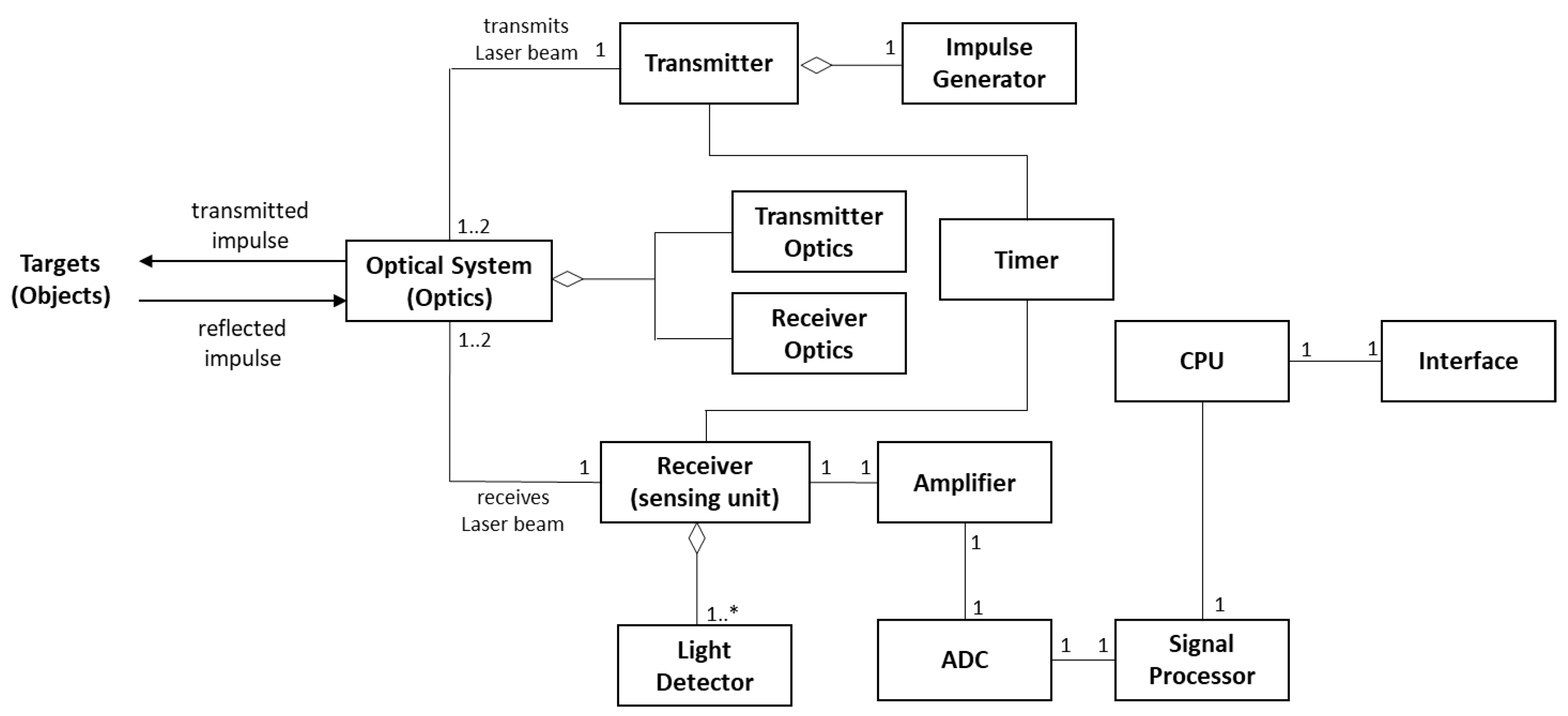

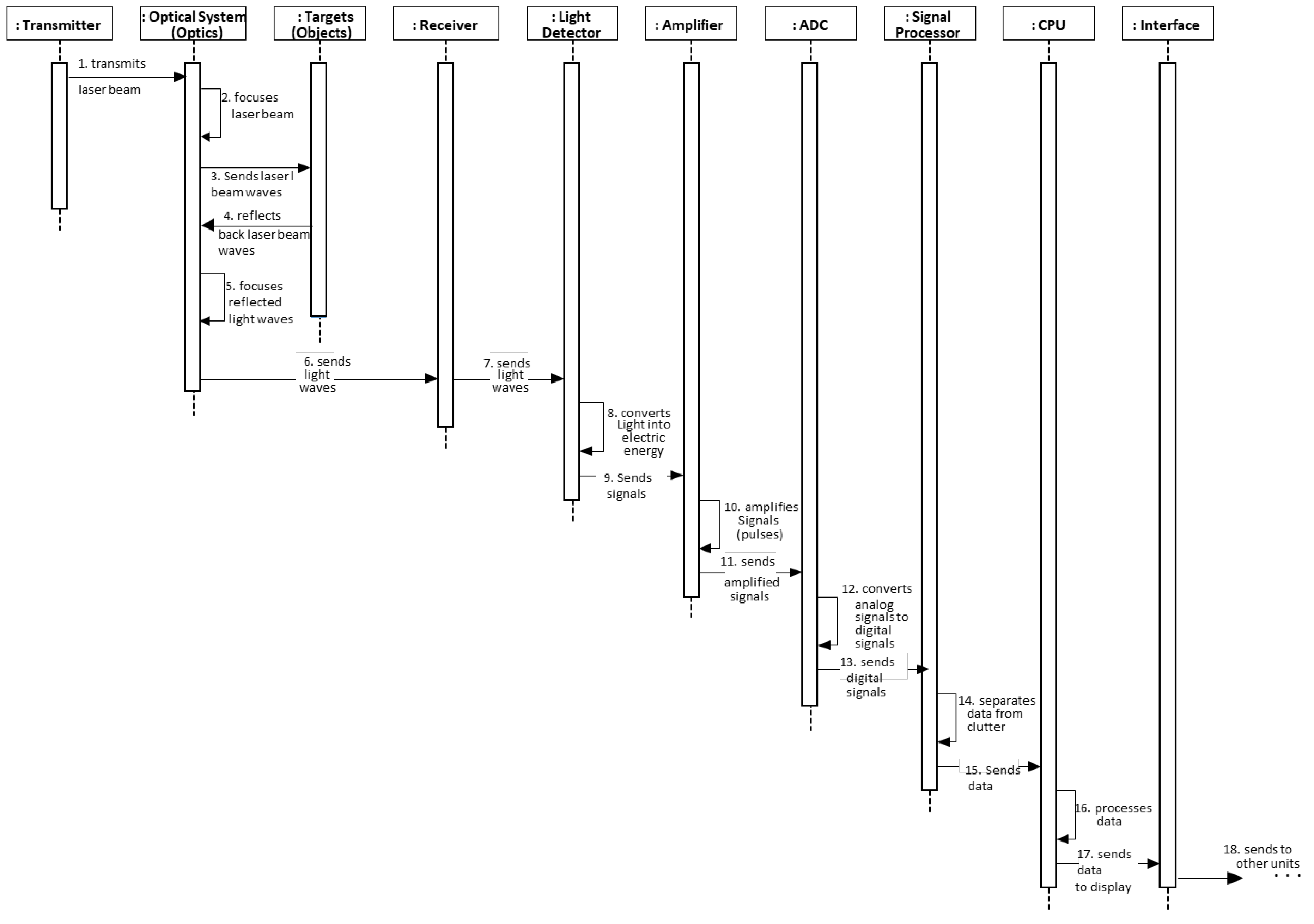

4.1. Lidar Sensor

4.1.1. Intent

4.1.2. Example

4.1.3. Context

4.1.4. Problem

- Accuracy: The measurement must be accurate enough and produced in real-time.

- Cost: The solution must have a reasonable cost.

- Performance: The performance of the sensor should not be limited by poor weather conditions, such as heavy rain, cloud, snow, fog, atmospheric haze, and strong and dazzling light, which can attenuate the signal and negatively affect the detection of objects.

- Complementarity: Different types of sensors should complement the measures of other sensors; otherwise, they would be a waste of money and functions.

- Reliability: Data measured and collected by sensors must be reliable.

4.1.5. Solution

4.1.6. Implementation

4.1.7. Example Resolved

4.1.8. Known Uses

- Autonomous systems: Honda Motor’s new self-driving Legend luxury sedan uses lidar sensors. Also, Waymo and many other autonomous car manufacturers are using lidar. Some car manufacturers, such as Germany’s Daimler, Sweden’s Volvo, the Israel-based Mobileye, and Toyota Motors have adopted lidar sensors (produced by Luminar Technologies) for their self-driving prototypes [23].

- Lidar sensors are used for Adaptive Cruise Control (ACC), Autonomous Emergency Brake (AEB), Anti-lock Braking System (ABS), etc. In addition, five lidar units produced by the German company Sick AG were used for short-range detection on Stanley, the autonomous car that won the 2005 DARPA Grand Challenge [24].

- Forestry: lidar sensors are used to measure vegetation height, density, and other characteristics across large areas, such as forests, by capturing information about the landscape. Lidar directly measures vertical forest structure; this direct measurement of canopy heights, sub-canopy topography, and the vertical distribution of intercepted surfaces provides high-resolution maps and much data for forest characterization and management [25]. Aerial lidar was used to map the bush fires in Australia in early 2020 [24].

- Apple products: lidar sensors are used on iPhone 12 Pro, Pro Max, and iPad Pro, to improve portrait mode photos and to improve background shots in night mode.

- A Doppler lidar system was used in the 2008 Summer Olympics to measure wind fields during the yacht competition [24]

- A robotic Boeing AH-6 (light attack/reconnaissance helicopter) performed a fully autonomous flight in June 2010 using lidar to avoid obstacles [24].

4.1.9. Consequences

- Accuracy: Accuracy is high in lidar sensors because of their high spatial resolution, produced by the small focus diameter of their beam of light and shorter wavelength.

- Cost: The production of lidar sensors in high volume can bring their cost down. Luminar Technologies has developed low-priced lidar sensors priced at $500 to $1000 [23]. Some companies are trying to reduce the cost of lidar even more. Also, lidar manufacturing companies are using 905-nm diode lasers (inexpensive and can be used with silicon detectors) to bring lidar costs down [26].

- Performance: High-performance lidar sensors produced by Luminar Technologies can detect dark objects, such as debris or a person wearing black clothes [23]. Also, the performance of lidar sensors can be improved by combining them with other types of sensors like vision-based cameras, radar, etc.

- Complementarity: All the data collected by lidar, and other sensors are sent to Sensor Fusion Processor to combine them and build a more accurate model.

- Heterogeneity in lidar sensors makes complex their integration with other systems. Different types of lidar sensors are produced by different lidar manufacturing companies and there are no strict international protocols that guide the collection and analysis of the data using lidar [29].

- Lidar technology is not accepted by all auto manufacturing companies. For example, Tesla uses camera-based technology, instead of lidar sensors.

- Computational requirements for real-time use are high [24].

4.1.10. See Also (Related Patterns)

- A pattern for Sensor Network Architectures describes sensor network configurations [30].

- Sensor Node Design pattern [31], is a design pattern intended to model the architecture of a wireless sensor node with real-time constraints; it is designed and annotated using the UML/MARTE standard.

- Sensor Node pattern [32] describes the architecture and dynamics of a Sensor Node that includes a processor, memory, and a radio frequency transceiver.

- This pattern is derived from the Sensor AEP.

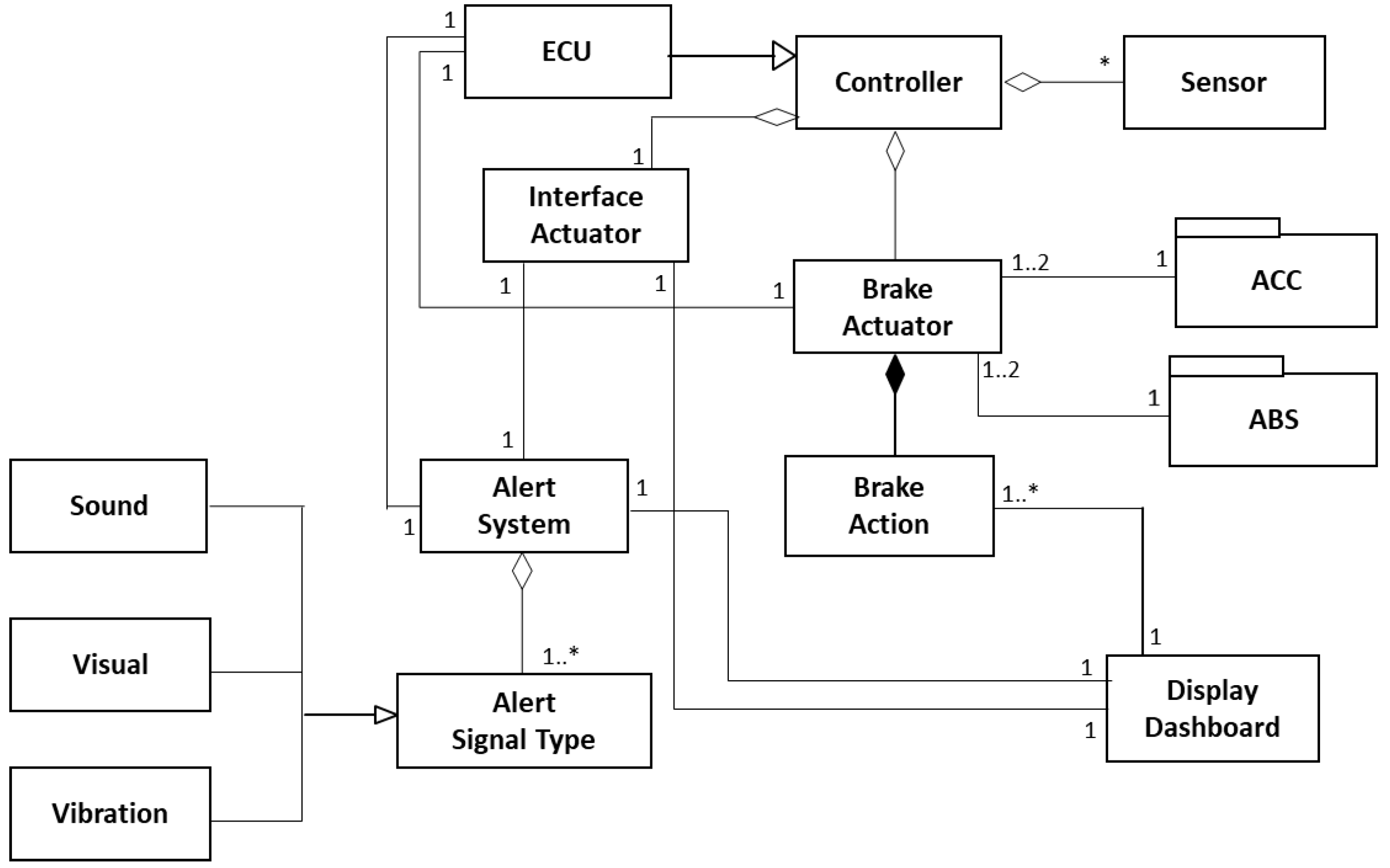

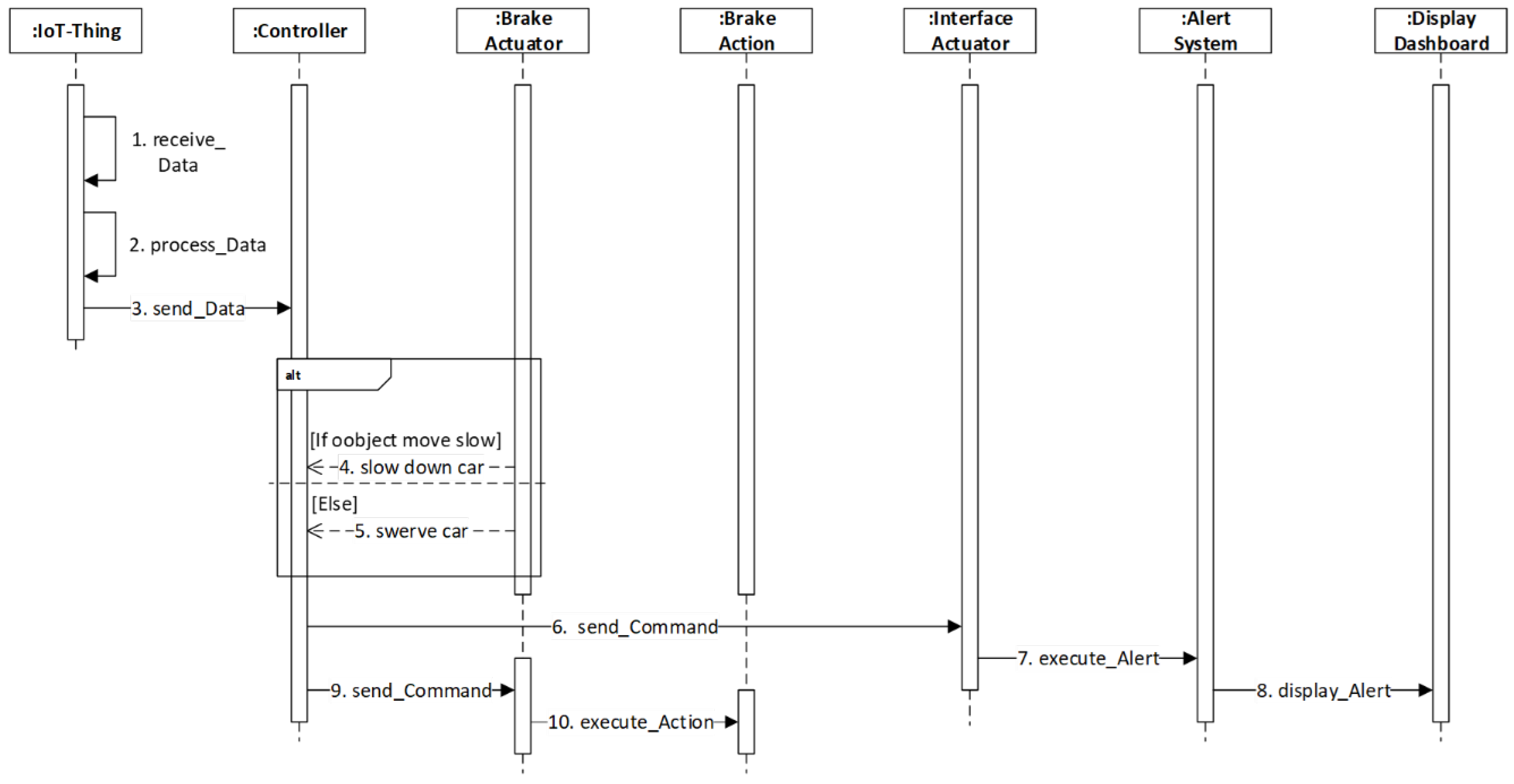

4.2. Autonomous Emergency Braking System (AEB)

4.2.1. Intent

4.2.2. Context

4.2.3. Problem

- Accuracy: Systems in autonomous cars must be able to execute commands from controllers accurately.

- Reliability: Autonomous cars must have reliable systems that perform correctly when needed.

- Resources: There must be enough resources, e.g., energy and computing power, to perform the actions.

- Safety: Systems must be able to stop cars in time with minimal delay.

- Availability: Systems must be available to act all the time in emergencies.

- Autonomy: Systems must be able to operate autonomously based on needs.

- Performance: There must be ways to perform different varieties of actions (slow down, speed up, or stop the systems if necessary) according to the needs of the systems.

4.2.4. Solution

4.2.5. Implementation

4.2.6. Known Uses

- Tesla Model 3 is designed to determine the distance from a detected object traveling in front of the car and apply the brakes automatically to reduce the speed of the car when there is a possible collision. When the AEB applies brakes, the dashboard displays a visual warning and sounds a chime [39]. The system is also active when the autopilot feature is disengaged.

- Subaru models have an AEB system called EyeSight. This system is comprised of two cameras mounted above the windscreen to monitor the path ahead and it brings the car to a complete stop if it detects any issues [4]. Subaru’s AEB system is integrated with ACC and lane departure warning.

- Mercedes-Benz introduced an early version of AEB in their S-Class 2005 model, which was one of the first cars with AEB. The recent S-class model of Mercedes-Benz has short-range and long-range radar, optical cameras, and ultrasonic detectors to detect the closest obstacles [40].

- The AEB system used in Volvo XC40 applies brakes automatically when objects like cyclists, pedestrians, city traffic, and faster-moving vehicles are detected [41].

- Other examples are Ford F-150, Honda CR-V, Toyota Camry, and many other car brands/models [42].

4.2.7. Consequences

- Accuracy: The units in the architecture described earlier are able to brake automatically in the presence of objects.

- Reliability: Autonomous braking systems can be built to be reliable by using high-quality materials and some redundancy.

- Resources: It is possible to provide enough resources, e.g., power, to perform the actions because cars generate energy that can be reused.

- Safety: Autonomous braking systems stop cars at a precise time (when the collision is expected) to avoid accidents. They are effective in reducing collisions.

- Availability: AEB systems give alerts and are available to act in emergencies all the time by the appropriate implementation.

- Autonomy: AEB systems operate autonomously and unattended.

- Performance: AEB systems can handle different situations, such as sensor errors, road conditions, obstacles, speed, velocity, position, direction, timing, etc., and slow down or stop cars completely if necessary.

- AEB systems are less effective in the dark, in the glare from sunrise and sunset, and in bad weather because sensors may not be able to detect objects efficiently. They also may not be very effective at very high speeds.

- Each car manufacturer has its specific approach to braking system designs and names them differently, therefore no two braking systems work in the same manner, except for fundamental characteristics. This may make maintenance complex.

4.2.8. See Also (Related Patterns)

- A Pattern for a Secure Actuator Node [43], describes how an actuator node performs securely on commands sent by a controller and communicates the effect of these actions to other nodes or controllers.

- A Real-Time Design Pattern for Actuators in Advanced Driver Assistance Systems [44] defines a design pattern for an action subsystem of an advanced driver assistance system to model the structural and behavioral aspects of the subsystem.

- Design Patterns for Advanced Driver Assistance Systems in [45] describes three patterns, namely i) Sensing, ii) Data Processing, and iii) Action-Taking, to cover design problems of sensing, processing, and control of sensor data, and taking actions for warning and actuation.

- This pattern is derived from the Actuator AEP.

5. Validation of AEPs and their derived patterns

6. An SSF for Autonomous Driving

7. Related Work

8. Conclusions

| 1 | The point clouds are datasets that represent objects or space; they are mostly generated using 3D laser scanners and lidar technology and techniques [51]. They are created at sub-pixel accuracy, at very dense intervals, and in real-time [52]. |

| 2 | An ego vehicle is a vehicle that contains sensors to sense the physical environment around it. |

References

- Thapa B, Fernandez EB (2020) A Survey of Reference Architectures for Autonomous Cars. Proceedings of the 27th Conference on Pattern Languages of Programs (PLoP '20). The Hillside Group, USA.

- Fernandez EB (2013) Security Patterns in Practice: Designing Secure Architectures Using Software Patterns. John Wiley & Sons.

- Thapa B, Fernandez EB (2021) Secure Abstract and Radar Sensor Patterns. Proceedings of the 28th Conference on Pattern Languages of Programs (PLoP’21).

- Thomes S (2021) How Autonomous Emergency Braking (AEB) is redefining safety. https://www.einfochips.com/blog/how-autonomous-emergency-braking-aeb-is-redefining-safety/ (accessed Mar. 18, 2022).

- Wardlaw C (2021) What is Automatic Emergency Braking? https://www.jdpower.com/cars/shopping-guides/what-is-automatic-emergency-braking (accessed Mar. 18, 2022).

- Salfer-Hobbs M, Jensen M (2020) Acceleration, Braking, and Steering Controller for a Polaris Gem e2 Vehicle. Intermountain Engineering, Technology and Computing (IETC). pp. 1–6. doi: 10.1109/IETC47856.2020.9249175.

- Buschmann F, Meunier R, Rohnert H, Sommerlad P, Stal M (1996) Pattern-Oriented Software Architecture. Vol 1. Wiley Publishing.

- Fernandez EB, Yoshioka N, Washizaki H, Yoder J (2022) Abstract security patterns and the design of secure systems. Cybersecurity. [CrossRef]

- Schmidt DC, Fayad M, Johnson RE (1996) Software patterns. Commun ACM, vol. 39, no. 10, pp. 37–39. doi: 10.1145/236156.236164.

- Fernandez EB, Washizaki H, Yoshioka N, Okubo T (2021) The design of secure IoT applications using patterns: State of the art and directions for research. Internet of Things, vol 15. doi: 10.1016/j.iot.2021.100408.

- Fernandez, EB, Astudillo, H, Orellana, C. A pattern for a Secure IoT Thing. 26th European Conference on Pattern Languages of Programs (EuroPLoP’21), July 07–11, 2021, Graz, Austria. ACM, New York, NY, USA. [CrossRef]

- Fernandez EB, Washizaki H, Yoshioka N (2008) Abstract security patterns. Proceedings of the 15th Conference on Pattern Languages of Programs - PLoP ’08. doi: 10.1145/1753196.1753201.

- Gamma E, Helm R, Johnson R, Vlissides J (1994) Design Patterns: Elements of Reusable Object-Oriented Software. Addison-Wesley.

- Avgeriou P (2003) Describing, Instantiating and Evaluating a Reference Architecture: A Case Study. Enterprise Architecture Journal, 342:1-24.

- Fernandez EB, Monge R, Hashizume K (2016) Building a security reference architecture for cloud systems. Requirements Engineering, vol. 21, no. 2, pp. 225–249. doi: 10.1007/s00766-014-0218-7.

- Uzunov AV, Fernandez EB, Falkner K (2015) Security solution frames and security patterns for authorization in distributed, collaborative systems. Computers & Security, vol. 55, pp. 193–234. doi: 10.1016/j.cose.2015.08.003.

- Zupan M, Ashby MF, Fleck NA (2002) Actuator Classification and Selection—The Development of a Database. Advanced Engineering Materials, vol. 4, no. 12, pp. 933–940. doi: 10.1002/adem.200290009.

- Behroozpour B, Pandborn PAM, Wu MC, Boser BE (2017) Lidar System Architectures and Circuits. IEEE Communications Magazine, vol. 55, no. 10, pp. 135–142. doi: 10.1109/MCOM.2017.1700030.

- Rablau C, (2019) Lidar: a new self-driving vehicle for introducing optics to broader engineering and non-engineering audiences. Fifteenth Conference on Education and Training in Optics and Photonics: ETOP 2019, vol.11143, Quebec, Canada. doi: 10.1117/12.2523863.

- Haj-Assaad S, (2021) What Is LiDAR and how is it used in cars? https://driving.ca/car-culture/auto-tech/what-is-lidar-and-how-is-it-used-in-cars (accessed Sep. 16, 2021).

- Torun R, Bayer MM, Zaman IU, Velazco JE, Boyraz O, (2019) Realization of Multitone Continuous Wave Lidar. IEEE Photonics Journal, vol. 11, no. 4, pp. 1–10. doi: 10.1109/JPHOT.2019.2922690.

- Kocic J, Jovicic N, Drndarevic V (2018) Sensors and Sensor Fusion in Autonomous Vehicles. 2018 26th Telecommunications Forum (TELFOR), pp. 420–425. doi: 10.1109/TELFOR.2018.8612054.

- Watanabe N, Ryugen H (2021) Cheaper lidar sensors brighten the future of autonomous cars. Nikkei Asia. https://asia.nikkei.com/Business/Automobiles/Cheaper-lidar-sensors-brighten-the-future-of-autonomous-cars (accessed Sep. 09, 2021).

- Lidar - Wikipedia. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Lidar (accessed Mar. 18, 2022).

- Dubayah R, Drake J (2000), Lidar Remote Sensing for Forestry. Journal of Forestry, vol. 98, no. 6, pp. 44–46.

- Hecht J (2018), Lidar for Self-Driving Cars. Optics and Photonics News, vol. 29, no. 1, p. 26. doi: 10.1364/OPN.29.1.000026.

- Kumar GA, Lee JH, Hwang J, Park J, Youn SH, Kwon S, (2020) LiDAR and Camera Fusion Approach for Object Distance Estimation in Self-Driving Vehicles. Symmetry (Basel), vol. 12, no. 2, p. 324. doi: 10.3390/sym12020324.

- Why Optical Phased Array is the Future of Lidar for Autonomous Vehicles - LIDAR Magazine. https://lidarmag.com/2021/08/18/why-optical-phased-array-is-the-future-of-lidar-for-autonomous-vehicles/ (accessed May 29, 2022).

- Advantages and Disadvantages of LiDAR – LiDAR and RADAR Information. https://lidarradar.com/info/advantages-and-disadvantages-of-lidar (accessed Apr. 02, 2022).

- Cardei M, Fernandez EB, Sahu A, Cardei I (2011) A pattern for sensor network architectures. Proceedings of the 2nd Asian Conference on Pattern Languages of Programs (AsianPLoP ’11), pp. 1–8. doi: 10.1145/2524629.2524641.

- Saida, R, Kacem, YH, BenSaleh, MS, Abid, M (2020) A UML/MARTE Based Design Pattern for a Wireless Sensor Node. In: Abraham, A., Cherukuri, A., Melin, P., Gandhi, N. (eds) Intelligent Systems Design and Applications. ISDA 2018. Advances in Intelligent Systems and Computing, vol 940. Springer, Cham. [CrossRef]

- Sahu A, Fernandez EB, Cardei M, Vanhilst M (2010) A pattern for a sensor node. Proceedings of the 17th Conference on Pattern Languages of Programs (PLOP ’10), pp. 1–7. doi: 10.1145/2493288.2493295.

- Ross P (2021) Europe Mandates Automatic Emergency Braking. IEEE Spectrum. https://spectrum.ieee.org/europe-mandates-automatic-emergency-braking (accessed Mar. 18, 2022).

- A quick guide to ADAS | Delphi Auto Parts. https://www.delphiautoparts.com/usa/en-US/resource-center/quick-guide-adas (accessed Mar. 18, 2022).

- Szuszman P (2005) Adaptive cruise control system overview. 5th Meeting of the U.S. Software System Safety Working Group, Anaheim, California, USA.

- Kurczewski N (2021) Best Cars with Automatic Emergency Braking. U.S. News. https://cars.usnews.com/cars-trucks/best-cars-with-automatic-emergency-braking-systems (accessed Mar. 18, 2022).

- What is autonomous emergency braking?. Kia British Dominica. https://www.kia.com/dm/discover-kia/ask/what-is-autonomous-emergency-braking.html (accessed Apr. 02, 2022).

- Kapse R, Adarsh S (2019) Implementing an Autonomous Emergency Braking with Simulink using two Radar Sensors. Cornell University. https://arxiv.org/abs/1902.11210. doi: . [CrossRef]

- Tesla (2022) Collision Avoidance Assist. Model 3 Owner’s Manual. https://www.tesla.com/ownersmanual/model3/en_us/GUID-8EA7EF10-7D27-42AC-A31A-96BCE5BC0A85.html#CONCEPT_E2T_MSQ_34 (accessed Mar. 18, 2022).

- Laursen L (2014) Autonomous Emergency Braking. IEEE Spectrum. https://spectrum.ieee.org/autonomous-emergency-braking (accessed Mar. 18, 2022).

- Healy J (2019) 10 best cars with automatic emergency braking. Car Keys. https://www.carkeys.co.uk/guides/10-best-cars-with-automatic-emergency-braking (accessed Mar. 18, 2022).

- Doyle L (2020) Can brake assist be turned off?. ici2016.org. https://ici2016.org/can-brake-assist-be-turned-off/ (accessed Apr. 02, 2022).

- Orellana C, Astudillo H, Fernandez EB (2021) A Pattern for a Secure Actuator Node. 26th European Conference on Pattern Languages of Programs (EuroPLoP), pp. 1–6. doi: 10.1145/3489449.3490007.

- Marouane H, Makni A, Duvallet C, Sadeg B, Bouaziz R (2013) A Real-Time Design Pattern for Actuators in Advanced Driver Assistance Systems. 8th International Conference on Software Engineering Advances (ICSEA), pp. 152–161.

- Marouane H, Makni A, Bouaziz R, Duvallet C, Sadeg B (2016) Definition of Design Patterns for Advanced Driver Assistance Systems. Proceedings of the 10th Travelling Conference on Pattern Languages of Programs - VikingPLoP ’16, pp. 1–10. doi: 10.1145/3022636.3022639.

- Molina PJ, Meliá S, Pastor O (2002) User Interface Conceptual Patterns. Interactive Systems: Design, Specification, and Verification, 9th International Workshop, DSV-IS 2002, Rostock Germany, pp. 159–172. doi: 10.1007/3-540-36235-5_12.

- Grone B (2006) Conceptual patterns. 13th Annual IEEE International Symposium and Workshop on Engineering of Computer-Based Systems (ECBS’06), Potsdam, Germany, pp. 241– 246. doi: 10.1109/ECBS.2006.31.

- Gruber T (1995) Toward principles for the design of ontologies used for knowledge sharing. International Journal of Human-Computer Studies, vol. 43, no. 4–5, pp. 907–928.

- Janowicz K, Haller A, Cox S, Phuoc DL, Lefrançois M (2019) SOSA: A lightweight ontology for sensors, observations, samples, and actuators. Journal of Web Semantics, vol. 56, pp. 1–10. doi: 10.1016/j.websem.2018.06.003.

- Haller A, Janowicz K, Cox S, Phuoc DL, Taylor K, Lefrançoi M (2021) Semantic sensor network ontology. https://www.w3.org/TR/vocab-ssn/ (accessed Nov. 21, 2021).

- Thomson C (2019) What are point clouds? 5 easy facts that explain point clouds. Vercator. https://info.vercator.com/blog/what-are-point-clouds-5-easy-facts-that-explain-point-clouds (accessed Jun. 10, 2022).

- Leberl F, Irschara A, Pock T, Meixner P, Gruber M, Scholz S, Wiechert A (1010) Point Clouds. Photogrammetric Engineering & Remote Sensing, vol. 76, no. 10, pp. 1123–1134. doi: 10.14358/PERS.76.10.1123.

- Fernandez EB, Washizaki H (2022) “Abstract Entity Patterns (AEPs)”, submitted for publication.

- Wieringa R (2009). “Design Science as nested problem solving”. 4th International Conference on Design Science Research in Information Systems and Technology.

- Rumbaugh J, Jacobson I, Booch G, The Unified Modeling Language Reference Manual (2nd Edition), Addison-Wesley, 2005.

- Villagran-Velasco Olga, Fernandez E.B., Ortega-Arjona J., Refining the evaluation of the degree of security of a system built using security patterns, Procs. 15th Int. Conference on Availability, Reliability and Security (ARES 2020), Dublin, Ireland, Sept. 2020.

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).