Submitted:

16 November 2025

Posted:

18 November 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

1.1. Einstein’s Search for a Unified Field Theory

1.2. Challenges to Achieving Unification and General Approach of This Paper

1.3. Structure of This Paper

- Kaluza-Klein theories and spontaneous compactification;

- Non-linear realisations and spontaneous symmetry breaking.

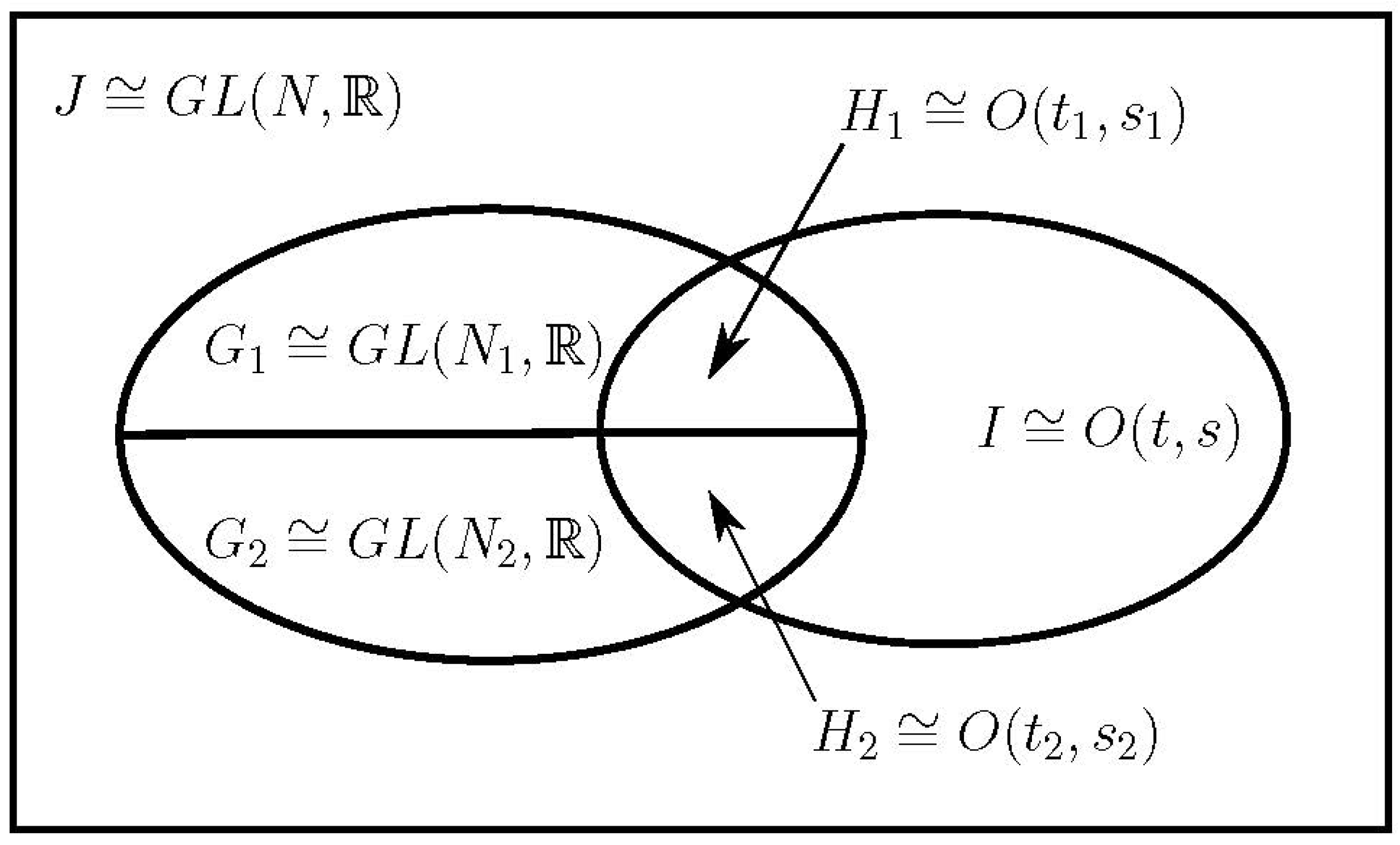

- the decomposition with respect to a direct product of general linear groups;

- how the presence of diagonalisable tensors provides information about these groups and the dimensionalities of the factor spaces;

- the decomposition of tensors on these spaces;

- how the Levi-Civita connection for such spaces can describe both gravity and gauge fields.

- Fermionic matter and how this affects the geometry;

- A field equation for the gauge fields;

- Transformations which mix Lorentz tensors;

- Translations;

- Isometries of spherical factor spaces;

- Quantum numbers, including charge quantisation;

- How the model evades O’Raifeartaigh’s no-go theorem;

- Symmetry restoration at the decompactification limit;

- The meaning of energy in the model;

- Infinite curvature and dimensional reduction.

1.4. Notation and Mathematical Language

- Greek indices relate to our familiar four-dimensional spacetime and run ;

- Upper-case Latin indices from the end of the alphabet () relate to additional dimensions and run from 5 to N, where N is the total number of space and time dimensions;

- Upper-case Latin indices from the middle of the alphabet () relate to the whole N-dimensional spacetime and run ;

- Lower-case Latin indices from the middle of the alphabet () run , for example for macroscopic spatial dimensions.

- We largely avoid the language of fibre bundles, as we are seeking to emphasise firstly how the group transformations are induced by changes of coordinates, and secondly how four-dimensional spacetime and the compact space relating to internal symmetries are two subspaces of a higher-dimensional spacetime that have similar properties within the theory;

- We usually use indices for coordinate bases and frame bases explicitly, rather than using the language of differential forms and exterior derivatives;

- We avoid talking about ‘tetrad fields’ altogether, preferring to talk about transformations between coordinate bases and various frame bases;

- We use the same indices for coordinate bases and frame bases, as frame bases may also be coordinate bases in some situations, and form part of the same carrier space for the transformations;

- The groups involved in this paper are considered to act directly on the bases on tangent spaces. These bases are given the abstract notation and , rather than considering them as differential operators, with the hat representing an orthonormal basis;

- Where we need to specify which coordinate system a set of tensor components relates to, we will do so by putting it in brackets in a superscript or subscript. For example, the components of a vector in a coordinate system will be written ;

- Where we are evaluating a quantity at a given point, we generally state explicitly which point it is evaluated at, to avoid confusion between the value of the quantity and the functional form of that quantity;

- A metric is denoted with a Roman , for example , to distinguish it from the element of the group G (more clearly than just the position of the indices).

2. Existing Literature from Other Authors

2.1. Kaluza-Klein Theories and Spontaneous Compactification

- The spacetime on which the theory is based;

- What the internal transformation group acts upon (where this is stated);

- How its gauge fields appear in the theory.

2.1.1. Kaluza-Klein Theories of the 1920s-1960s

so clearly this shape of spacetime was assumed by them.The idea of achieving [a unified field theory] by means of a five-dimensional cylinder world never dawned on me[27]

Then, in a follow-up letter[32], he showed that the periodicity of the extra dimension could lead to the quantization of charge – and that this would require its radius to be of the order of m.A main motivation for Klein was to relate the fifth dimension with quantum physics. From a postulated five-dimensional wave equation …and by neglecting the gravitational field, he arrived at the four-dimensional Schrödinger equation after insertion of the quantum mechanical differential operators

This has components1 which in our notation would be written . However, use of local geodesic coordinates means that the appear in the metric for these coordinates (as undifferentiated factors):there is a connection in the bundle, given by a Lie algebra valued 1-form A on the bundle manifold.

2.1.2. Spontaneous Compactification

2.1.3. Kaluza-Klein Theories of the 1970s and 1980s

2.2. Non-Linear Realisations and Spontaneous Symmetry Breaking

3. Motivations Behind This Model of Covariant Compactification

3.1. The Geometrised Universe

This idea is expressed by Davies as…variation of the curvature of space is what really happens in that phenomenon we call the motion of matter…That in the physical world nothing else takes place but this variation.[51]

We are familiar with taking measurements in space using a ruler and in time by using a clock. This is the spacetime of the ‘physical world’, as Clifford puts it. It is hard to see how a ruler or a clock could (hypothetically) be applied to the internal field spaces of Gell-Mann and Levy’s sigma models or those in the models proposed by Kerner and Luciani.the forces and fields … themselves being explained in terms of geometry[52].

3.2. The Relation Between Unitary Transformations on Spinors and Orthogonal Transformations on Tensors

3.3. Symmetry Breaking

4. Relevant Content from My Previous Papers

4.1. Basis Transformations and Connections

4.2. Compactification on Product Manifolds

4.2.1. Product Manifolds

4.2.2. Orbits of Rank-Two Tensors and Diagonalisability

4.2.3. Stabiliser Groups and the Product Space Decomposition Theorem

- The spacetime coincides with a product manifold across that region;

- The dimensionalities of its factor spaces are equal to the multiplicities of the eigenvalues;

- The tensor is stabilised by G across the region, where G is a direct product of the general linear groups of basis changes on the factor spaces;

- A representative of the coset space will take us from a generic coordinate basis to a basis relating to a set of coordinates which respect the factor spaces;

- In any coordinate system which respects the factor spaces, the tensor field is diagonalised.

4.2.4. Applying the Product Space Decomposition Theorem in the Kaluza-Klein Framework

5. Using a Covariant Derivative to Determine the Factor Spaces and Symmetry Groups

6. Deriving a Field Equation from a Lagrangian

7. Deriving a Field Equation by Generalising Poisson’s Equation

7.1. Generalising Laplace’s Equation

7.2. Using Poisson’s Equation to Interpret the Proportionality Constant

8. Solutions

8.1. Properties of the Field Equation

8.2. Solutions with a Trivial Operator

8.3. Solutions with Diagonalisable

- The algebraic invariants of ;

- The eigenvalues of ;

- The stabiliser groups of ;

- The dimensionalities of the factor spaces.

8.4. Specific Solutions for Symmetric

- A similar decomposition can naturally be used with analogous results when is itself a direct product of general linear groups;

- We have arrived at these solutions without any need to have a curvature tensor appearing explicitly in the Lagrangian. This provides some justification for choosing the covariant derivative as the tensor which determines the symmetry breaking pattern.

9. Worked Example: The Two-Sphere

10. Discussion

10.1. Spinors, Charge Quantisation and Non-Cartesian Product Spacetimes

10.1.1. Charge Quantisation and Calculations on a Cartesian Product Space

10.1.2. Gauge Fields and Their Interaction with Matter

10.1.3. Relaxing the ‘Cylinder Condition’

10.2. Symmetries Beyond G

10.2.1. O’Raifeartaigh’s Theorem and What Happens to Symmetries on Compactification

10.2.2. Symmetries and Degrees of Freedom on the Two-Sphere

10.3. Energy and the Limits of Curvature

10.4. Symmetries of the Standard Model

11. Conclusions

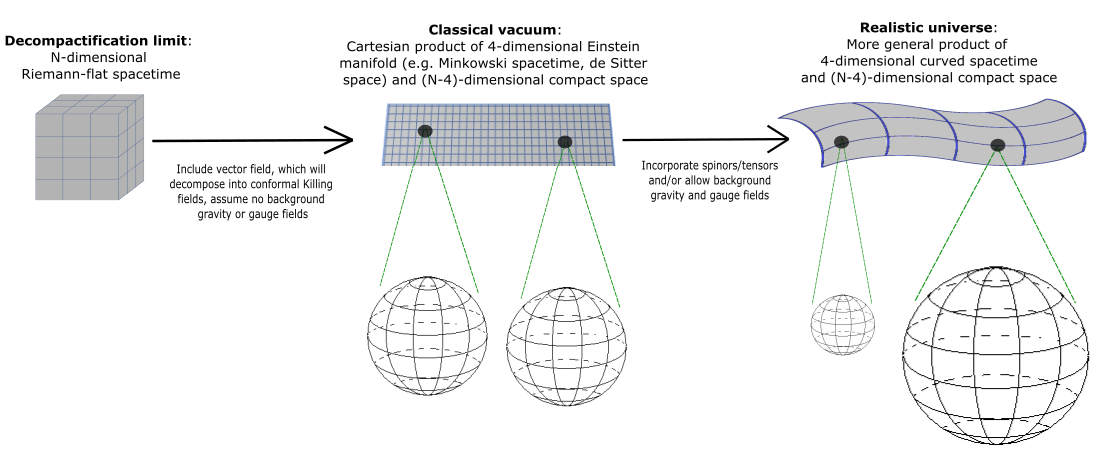

- Additional dimensions are physical dimensions, which appear on the same footing as the four we are familiar with in the ‘decompactification limit’ of zero curvature;

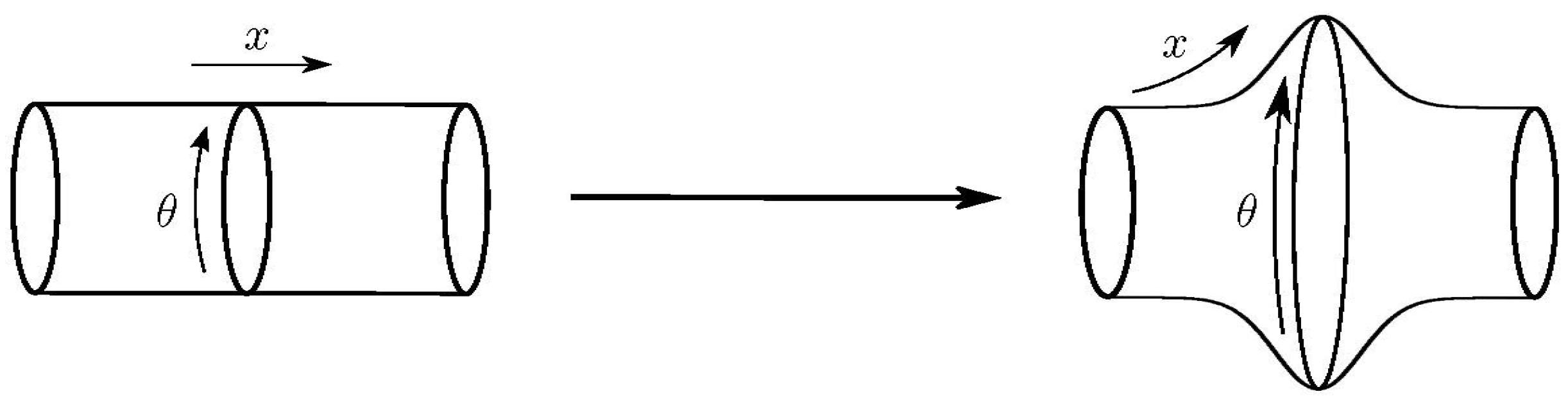

- Variations in the curvature of the compact factor space with the four-dimensional coordinates are manifested as gauge fields; singularities in the extra dimensions cannot result unless a quantity controlling their curvature becomes infinite - and unless the fields are zero everywhere, this can only happen if their rest mass density is infinite;

- The group of higher-dimensional coordinate transformations is non-linearly realised, by adopting coordinates adapted to the factor spaces;

- The full higher-dimensional symmetry is not restored at higher energies, it only becomes manifest at the ‘decompactification limit’;

- The action is invariant under the full higher-dimensional group of transformations, the field equation is fully covariant and symmetry breaking patterns are determined by invariants;

- Unitary gauge transformations do not act directly on the space or its tensors; they act directly on spinors, but the action of such a transformation on the outer products of a spinor and its conjugate includes an orthogonal transformation which rotates vector and tensor fields;

- There are only additional translation symmetries at the ‘decompactification limit’; in our universe, these are replaced by additional internal symmetries, which provide at most one additional quantum number with discrete eigenvalues, thus evading O’Raifeartaigh’s no-go theorem;

- The model could possibly provide a physical interpretation of renormalisation.

Funding

Acknowledgments

Abbreviations

| GR | General Relativity |

| SSB | Spontaneous Symmetry Breaking |

| 1 | Kerner calls these ‘coordinates’ when they are introduced, but they appear to be components of A |

| 2 | Gabrielli[58] also looks at extending the Lorentz group to include symmetries which mix fields of different integer spin, but in four dimensions. |

| 3 | In a similar vein, Tanaka[61] has studied the regulation of ultraviolet divergences with higher Kaluza-Klein modes of a spinor. |

References

- Yang, C.N.; Mills, R.L. Conservation of isotopic spin and isotopic gauge invariance. Physical Review 1954, 96, 191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Utiyama, R. Invariant theoretical interpretation of interaction. Physical Review 1956, 101, 1597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pereira, J. Lorentz connections and gravitation. In Proceedings of the AIP Conference Proceedings. American Institute of Physics, 2012, Vol. 1483, pp. 239–259, [1210.0379].

- Maluf, J.W. The teleparallel equivalent of general relativity. Annalen der Physik 2013, 525, 339–357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lawrence, T. Tangent space symmetries in general relativity and teleparallelism. International Journal of Geometric Methods in Modern Physics 2021, 18, 2140008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lawrence, T. Product manifolds as realizations of general linear symmetries. International Journal of Geometric Methods in Modern Physics 2022, 19, 2240006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nordström, G. On the possibility of unifying the electromagnetic and the gravitational fields. Phys. Zeitschr. 1914, 15, 504–506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nordström, G. On a theory of electricity and gravitation. Öfversigt af Finska Vetenskaps-Societetens Förhandlingar (Helsingfors), 1914-1915, Bd. LVII., 1–15, [physics/0702222]. [CrossRef]

- Nordström, G. On a possible foundation of a theory of matter. Öfversigt af Finska Vetenskaps-Societetens Förhandlingar (Helsingfors), 1914-1915, Bd. LVII., 1–21, [physics/0702223]. [CrossRef]

- Kaluza, T. On the unification problem in physics. International Journal of Modern Physics D 2018, 27, 1870001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Overduin, J.M.; Wesson, P.S. Kaluza-klein gravity. Physics reports 1997, 283, 303–378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Higgs, P.W. Broken symmetries, massless particles and gauge fields. Phys. Lett. 1964, 12, 132–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Higgs, P.W. Broken symmetries and the masses of gauge bosons. Physical review letters 1964, 13, 508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Higgs, P.W. Spontaneous symmetry breakdown without massless bosons. Physical review 1966, 145, 1156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kibble, T.W. Symmetry breaking in non-Abelian gauge theories. Physical Review 1967, 155, 1554. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salam, A.; Strathdee, J. Nonlinear realizations. I. The role of Goldstone bosons. Physical Review 1969, 184, 1750. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salam, A., Weak and electromagnetic interactions. In Elementary particle theory: relativistic groups and analyticity; Svartholm, N., Ed.; John Wiley & Sons; pp. 367–377.

- Weinberg, S. A Model of Leptons. Phys. Rev. Lett 1967, 19, 1264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Georgi, H.; Glashow, S.L. Unity of all elementary-particle forces. Physical Review Letters 1974, 32, 438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cremmer, E.; Scherk, J. Spontaneous compactification of space in an Einstein-Yang-Mills-Higgs model. Nuclear Physics B 1976, 108, 409–416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luciani, J. Space-time geometry and symmetry breaking. Nuclear Physics B 1978, 135, 111–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Volkov, L.; Tkach, V. Spontaneous compactification of subspace due to interaction of the Einstein fields with the gauge fields. JETP Lett. (United States) 1980, 32, 668–670. [Google Scholar]

- Randjbar-Daemi, S.; Percacci, R. Spontaneous compactification of a (4+ d)-dimensional Kaluza-Klein theory into M4× G/H for symmetric G/H. Physics Letters B 1982, 117, 41–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Volkov, L.; Tkach, V. Spontaneous compactification of subspaces. Theor. Math. Phys. 1982, 51, 427–431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Raifeartaigh, L. Lorentz invariance and internal symmetry. Physical Review 1965, 139, B1052. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coleman, S.; Mandula, J. All possible symmetries of the S matrix. Physical Review 1967, 159, 1251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goenner, H.F. On the history of unified field theories. Living reviews in relativity 2004, 7, 1–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coquereaux, R.; Esposito-Farese, G. The theory of Kaluza-Klein-Jordan-Thiry revisited. In Proceedings of the Annales de l’IHP Physique théorique, 1990, Vol. 52, pp. 113–150.

- Goenner, H.F. On the history of unified field theories. Part II.(ca. 1930–ca. 1965). Living Reviews in Relativity 2014, 17, 1–241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Straumann, N. On Pauli’s invention of non-abelian Kaluza-Klein Theory in 1953. In Proceedings of the The Ninth Marcel Grossmann Meeting: On Recent Developments in Theoretical and Experimental General Relativity, Gravitation and Relativistic Field Theories (In 3 Volumes). World Scientific, 2002, pp. 1063–1066, [gr-qc/0012054]. [CrossRef]

- Kerner, R. Generalization of the Kaluza-Klein theory for an arbitrary non-abelian gauge group. In Proceedings of the Annales de l’IHP Physique théorique, 1968, Vol. 9, pp. 143–152.

- Volkov, D.; Sorokin, D.; Tkach, V. Spontaneous compactification into symmetric spaces with nonsimple holonomy group. Theoretical and Mathematical Physics 1984, 61, 1117–1125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Volkov, D.; Sorokin, D.; Tkach, V. Gauge fields in mechanisms of spontaneous compactification of subspaces. Theoretical and Mathematical Physics 1983, 56, 746–751. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scherk, J.; Schwarz, J.H. How to get masses from extra dimensions. Nuclear Physics B 1979, 153, 61–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salam, A.; Strathdee, J. On kaluza-klein theory. Annals of Physics 1982, 141, 316–352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manton, N. A new six-dimensional approach to the Weinberg-Salam model. Nuclear Physics B 1979, 158, 141–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goldstone, J. Field theories with" superconductor" solutions. Nuovo Cimento 1960, 19, 154–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gell-Mann, M.; Lévy, M. The axial vector current in beta decay. Il Nuovo Cimento (1955-1965) 1960, 16, 705–726. [Google Scholar]

- Goldstone, J.; Salam, A.; Weinberg, S. Broken symmetries. Physical Review 1962, 127, 965. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schwinger, J. Chiral dynamics. Physics Letters B 1967, 24, 473–476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cronin, J.A. Phenomenological model of strong and weak interactions in chiral U(3) ⊗ U(3). Physical Review 1967, 161, 1483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, B.W.; Nieh, H. Phenomenological Lagrangian for field algebra, hard pions, and radiative corrections. Physical Review 1968, 166, 1507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weinberg, S. Nonlinear realizations of chiral symmetry. Physical Review 1968, 166, 1568. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coleman, S.; Wess, J.; Zumino, B. Structure of phenomenological Lagrangians. I. Physical Review 1969, 177, 2239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Callan Jr, C.G.; Coleman, S.; Wess, J.; Zumino, B. Structure of phenomenological Lagrangians. II. Physical Review 1969, 177, 2247. [Google Scholar]

- Isham, C. Metric structures and chiral symmetries. Nuovo Cimento A Serie 1969, 61, 188–202. [Google Scholar]

- Meetz, K. Realization of chiral symmetry in a curved isospin space. Journal of Mathematical Physics 1969, 10, 589–593. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boulware, D.G.; Brown, L.S. Symmetric space scalar field theory. Annals of Physics 1982, 138, 392–433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Honerkamp, J. Spontaneous symmetry breaking mechanism of SU(3) ⊗ SU(3). Nuclear Physics B 1969, 12, 227–238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Isham, C. The embedding of nonlinear meson transformations in a Euclidean space. Nuovo Cimento A Serie 1969, 61, 729–736. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clifford, W. On the space-theory of matter. Proc. Cambridge Philos. Soc. 1870, 2, 157–158. [Google Scholar]

- P, D. Superforce - The Search for a Grand Unified Theory of Nature; Unwin Paperbacks.

- R, D. Introducing Einstein’s Relativity; Oxford University Press.

- Lawrence, T. Symmetries of Field Configurations and No-Go Theorems. Preprints 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pons, J.M. Dimensional reduction, truncations, constraints and the issue of consistency. In Proceedings of the Journal of Physics: Conference Series. IOP Publishing, 2007, Vol. 68, p. 012030.

- Volkov, D.; Akulov, V. Is the neutrino a Goldstone particle? Physics Letters B 1973, 46, 109–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uematsu, T.; Zachos, C.K. Structure of phenomenological Lagrangians for broken supersymmetry. Nuclear Physics B 1982, 201, 250–268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gabrielli, E. Extended gauge theories in Euclidean space with higher spin fields. Annals of Physics 2001, 287, 229–259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Penrose, R. On the instability of extra space dimensions. The Future of Theoretical Physics and Cosmology 2003, pp. 185–201.

- Cipriani, N.; Senovilla, J.M. Singularity theorems for warped products and the stability of spatial extra dimensions. Journal of High Energy Physics 2019, 2019, 1–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tanaka, S. Ultraviolet divergences and extra space dimensions. In Quantum field theory; 1986.

- Duerksen, G. Dynamical symmetry breaking in supersymmetric U (n+ m) U (n)× U (m) chiral models. Physical Review D 1981, 24, 926. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kögerler, R.; Lucha, W.; Neufeld, H.; Stremnitzer, H. Dynamical generation of gauge bosons of hidden local symmetries in nonlinear sigma models. Physics Letters B 1988, 201, 335–339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Levi-Civita | Weitzenböck |

|---|---|

| Used in GR | Used in teleparallel theories |

| Metric-compatible | Metric-compatible |

| Symmetric on lower indices: | Has torsion: |

| For given coordinate system, uniquely defined across coordinate neighbourhood, in terms of metric | For a given coordinate system, not unique – depends on choice of parallelism; defined in terms of matrices |

| Parallel transport along segments of different geodesics don’t commute – so result depends on path | Uniquely defined once coordinates and parallelism are chosen – then parallel transport is independent of path taken |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).