Submitted:

02 March 2023

Posted:

03 March 2023

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

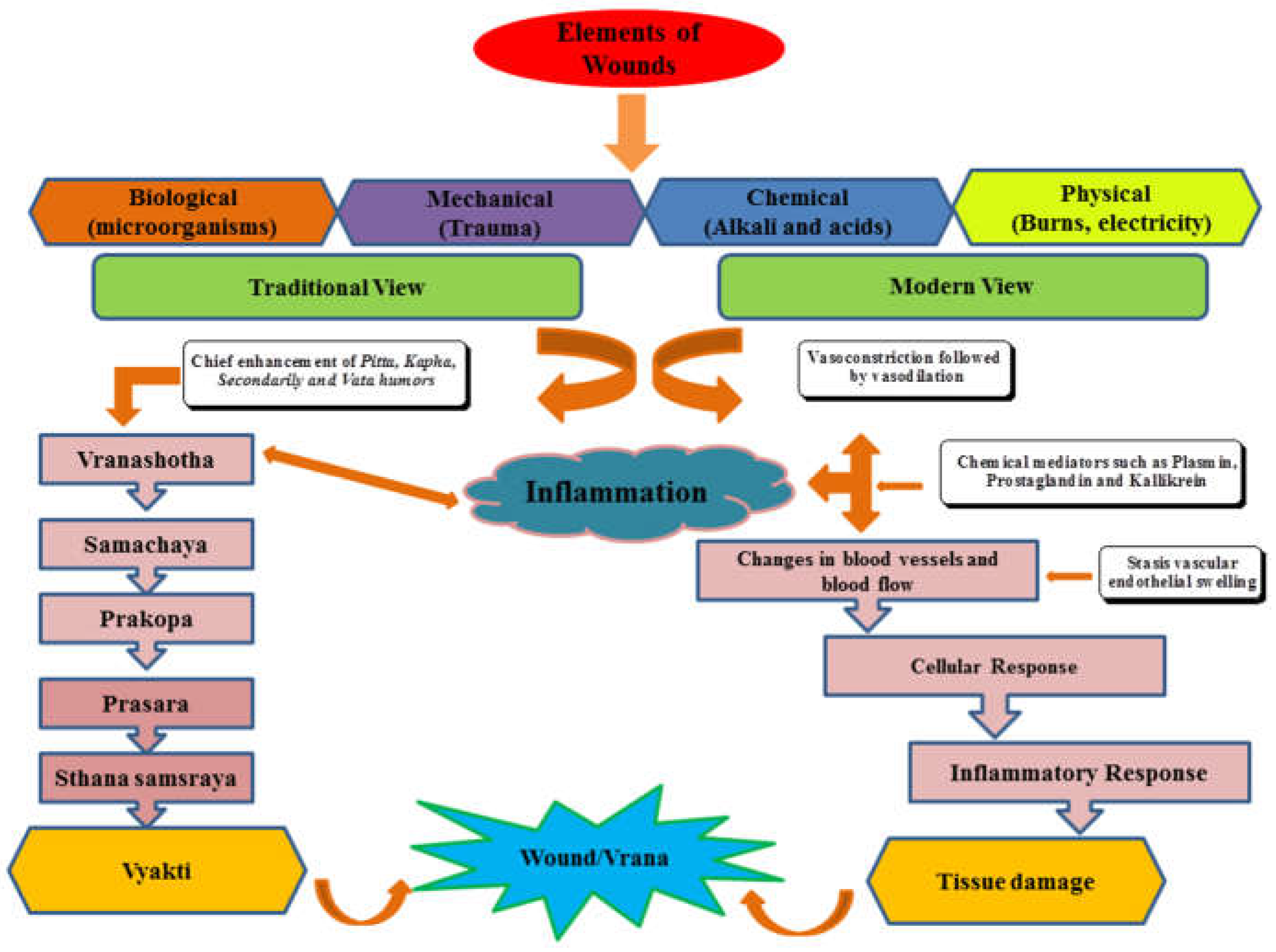

1. Introduction

2. Material and Methods

3. Medicinal Plants and Their Phytomolecules

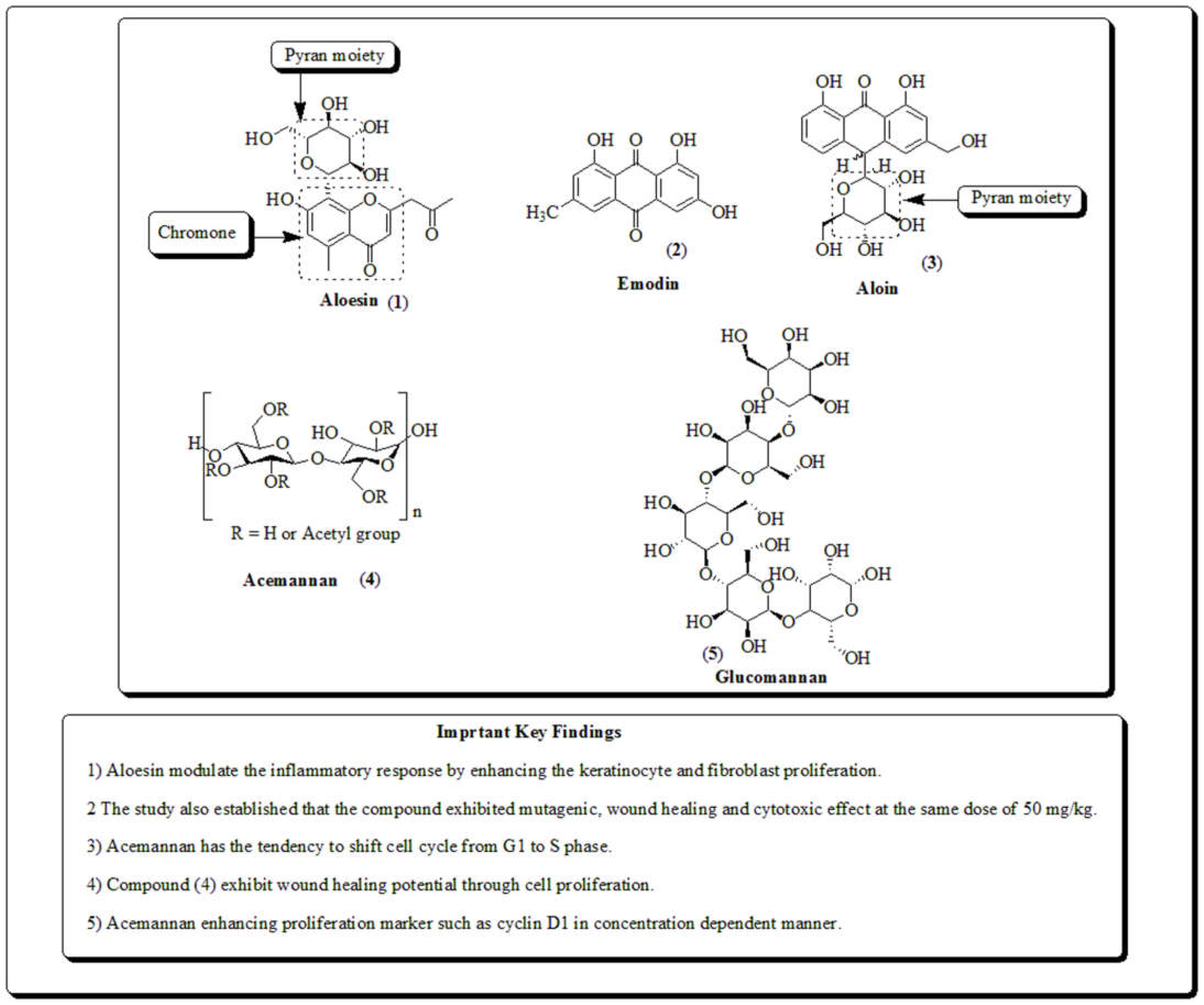

3.1. Aloe vera

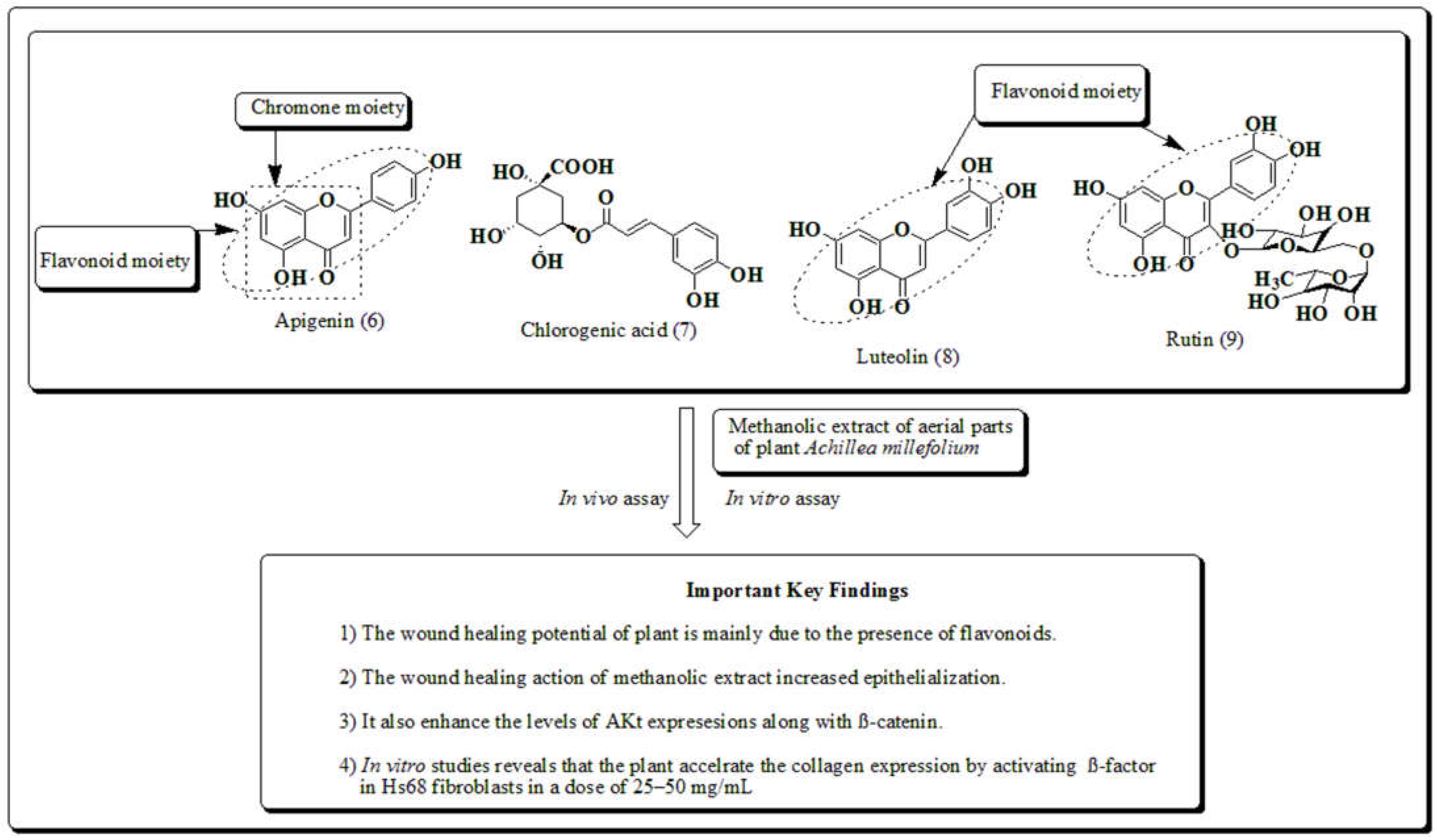

3.2. Achillea millefolium

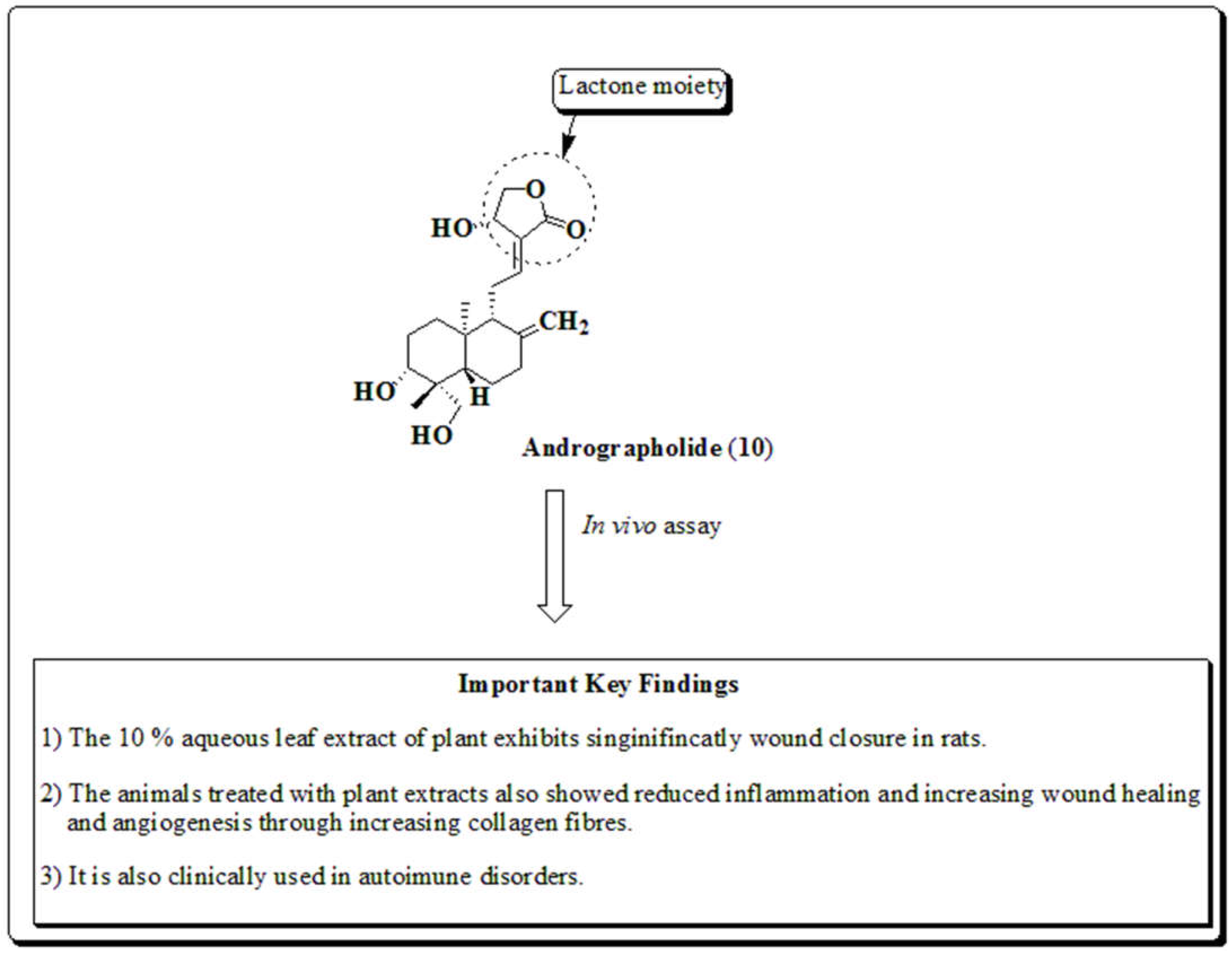

3.3. Andrographis paniculata

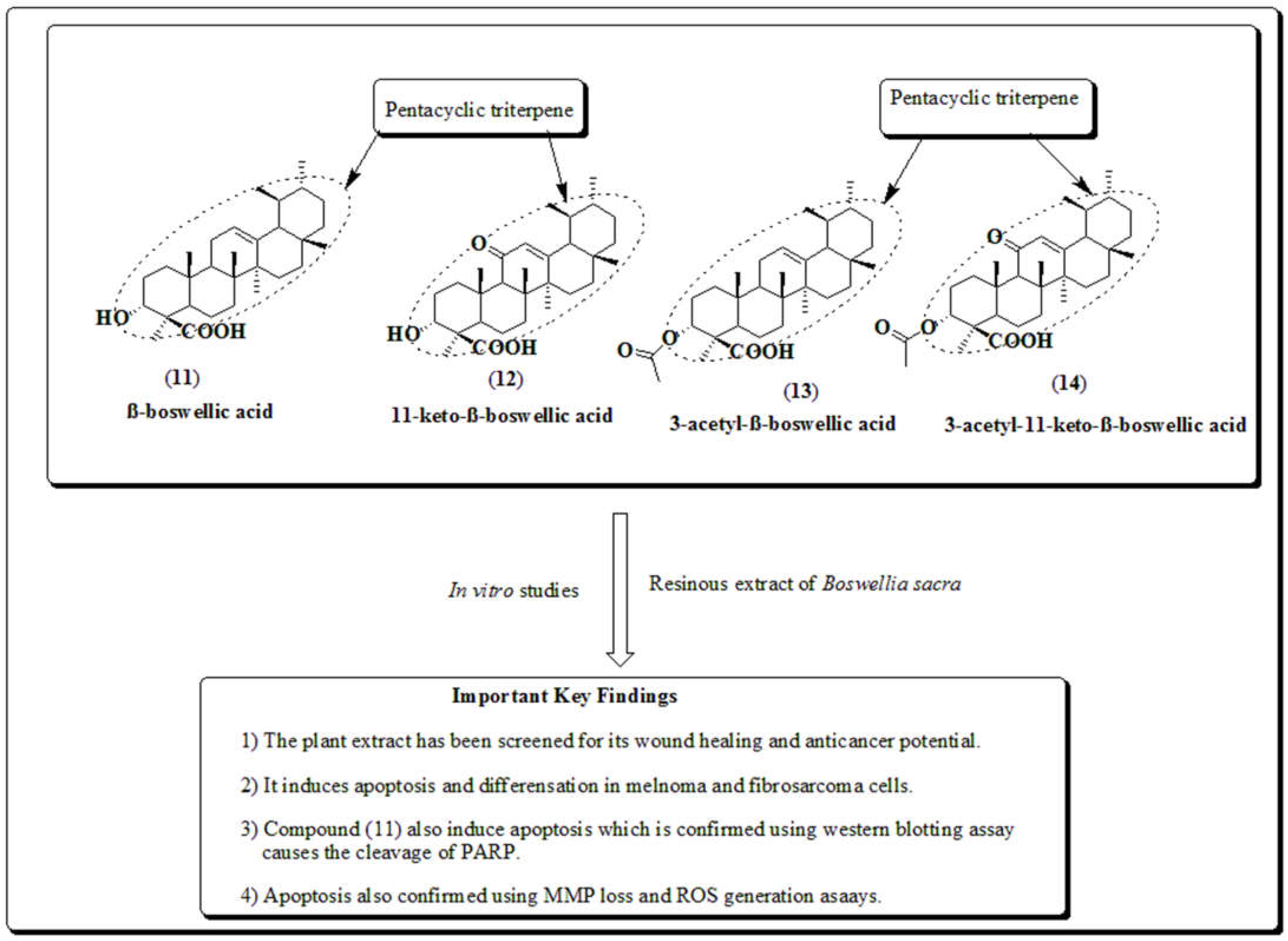

3.4. Boswellia sacra

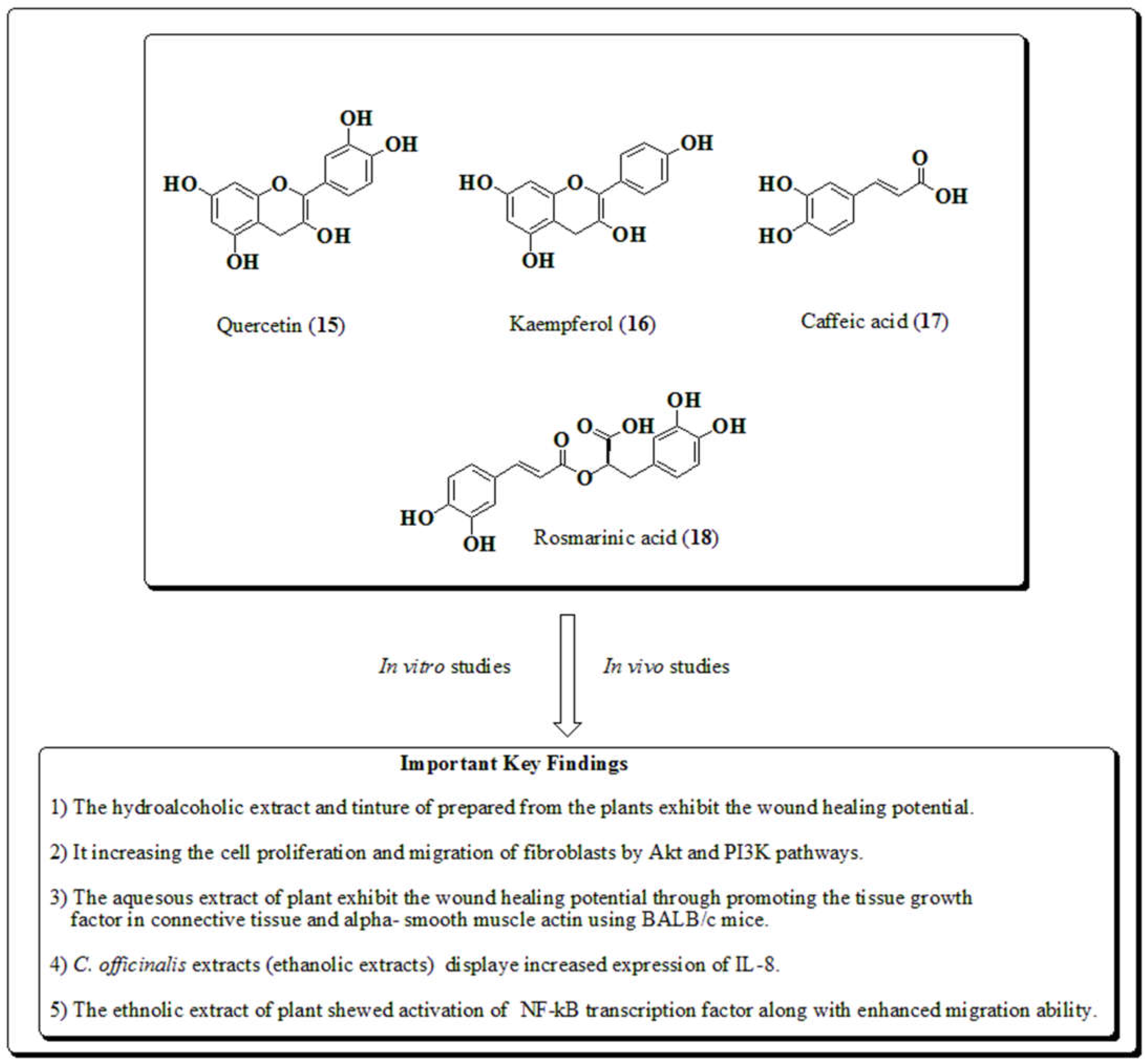

3.5. Calendula officinalis

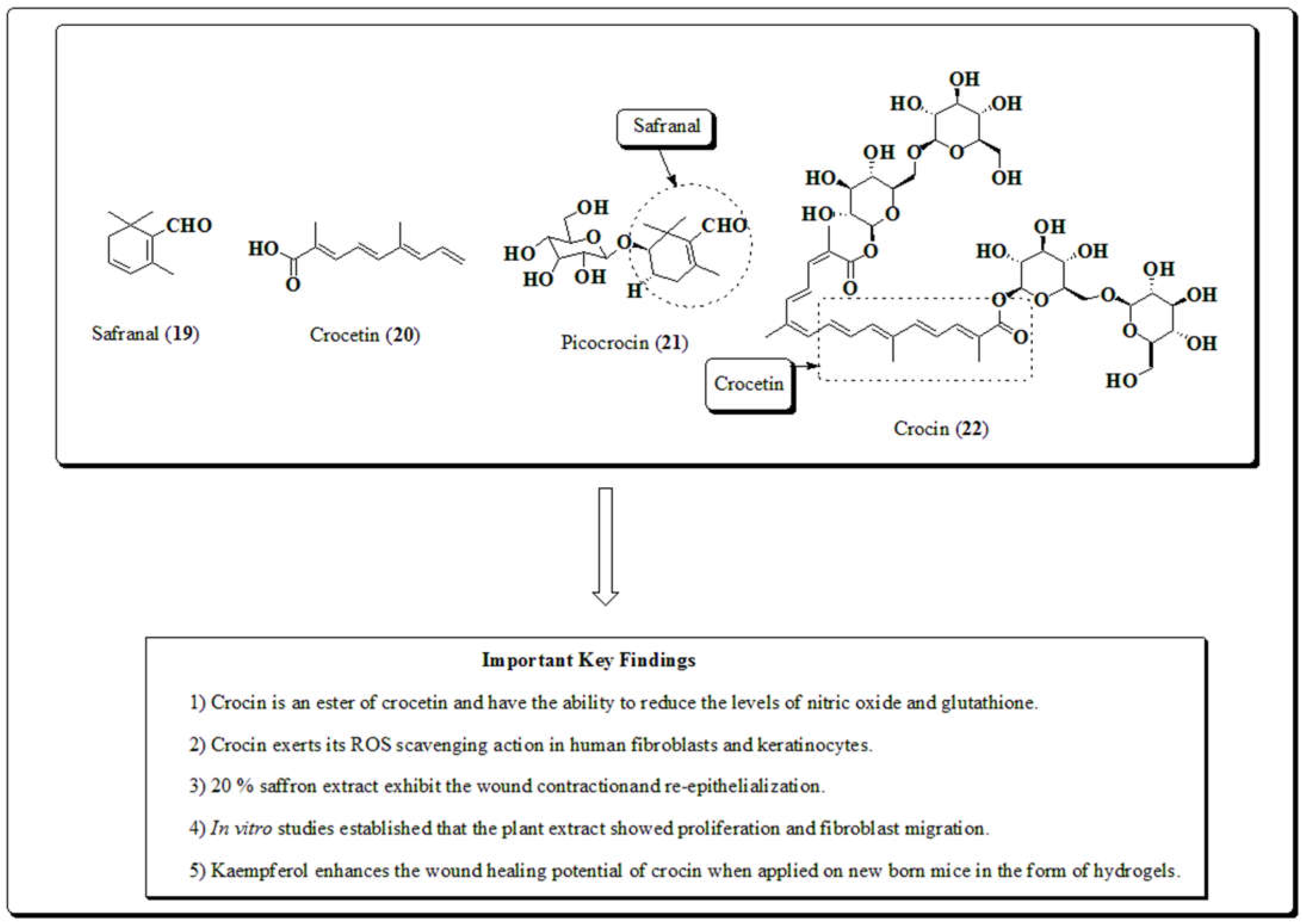

3.6. Crocus sativus

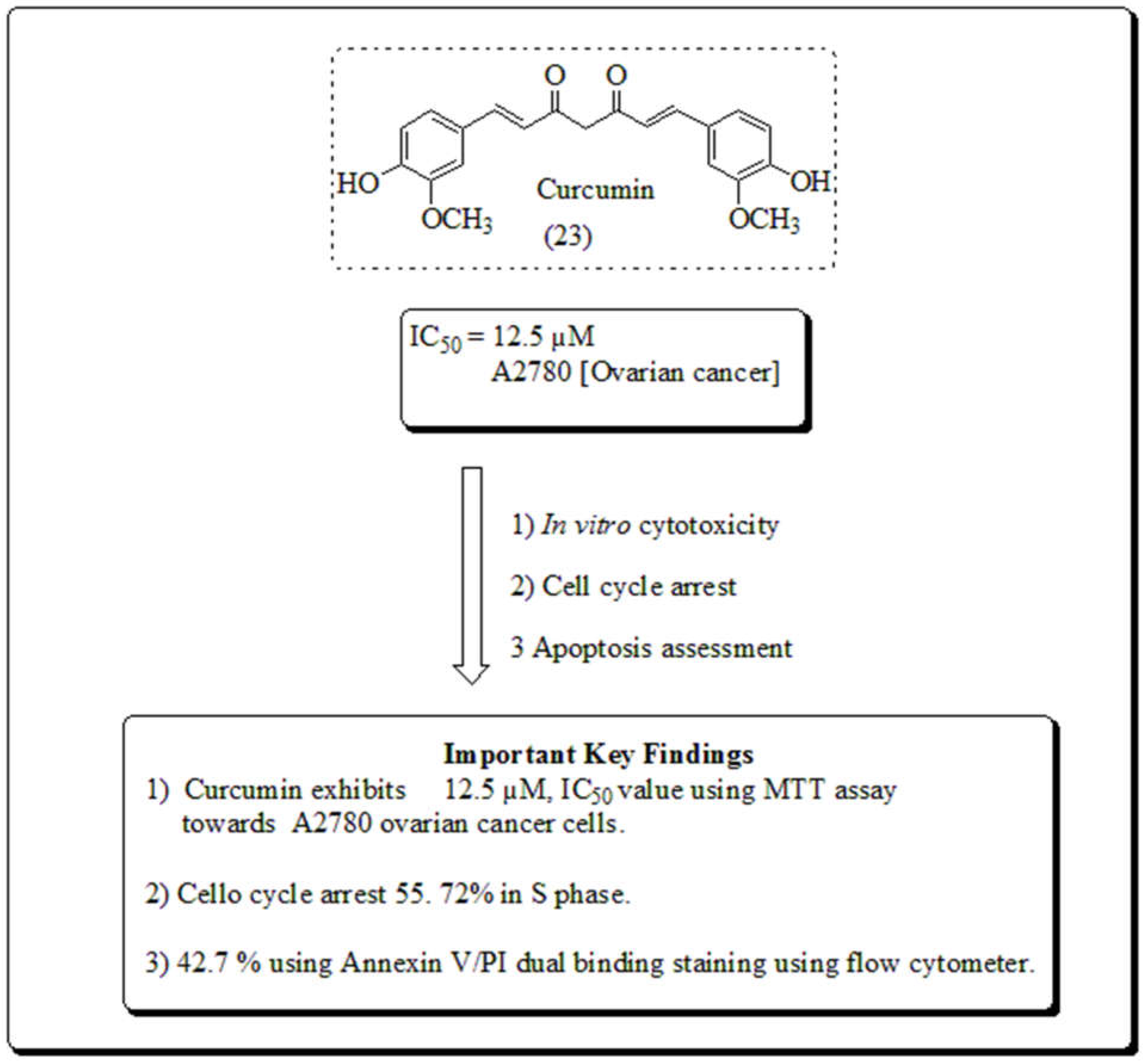

3.7. Curcuma longa

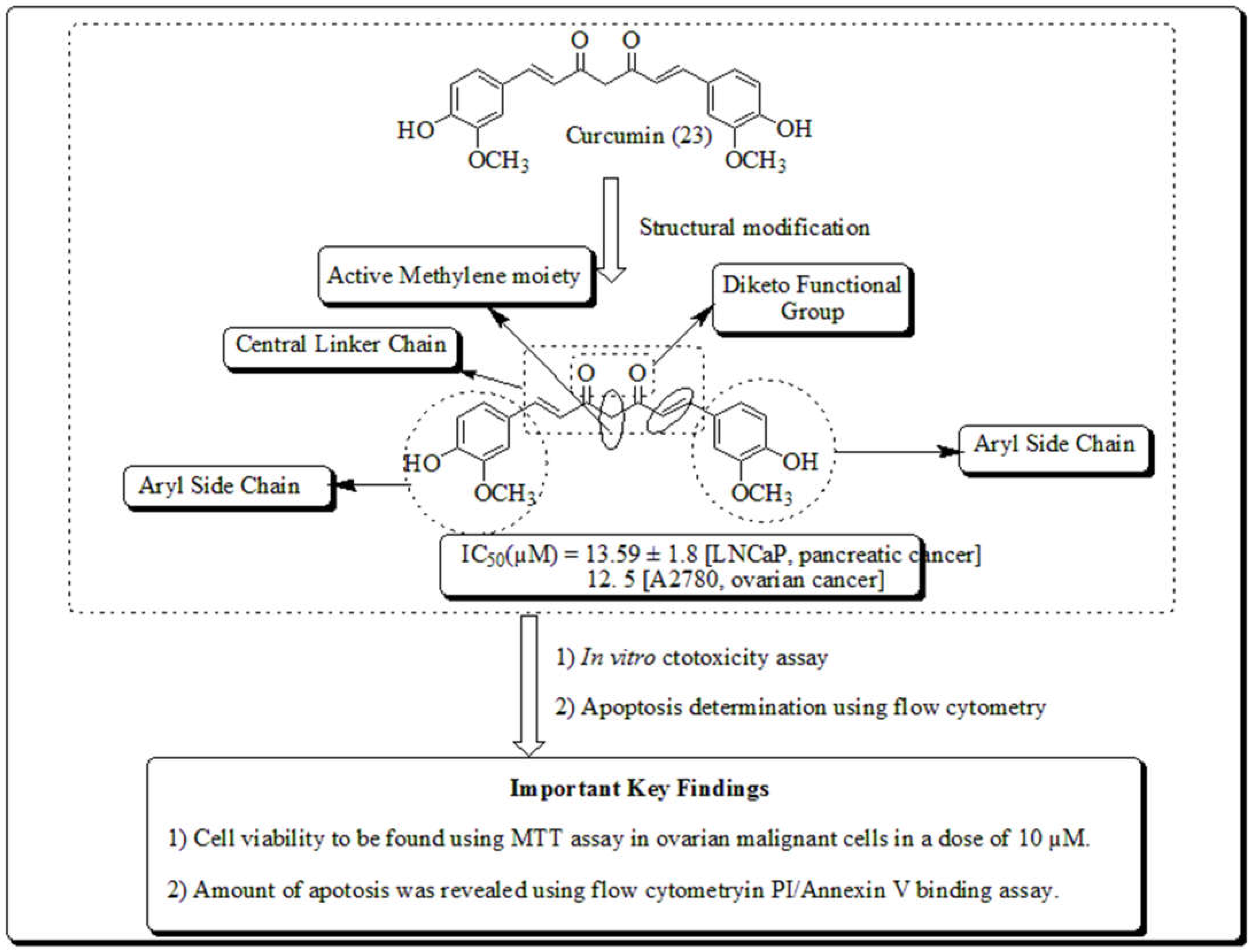

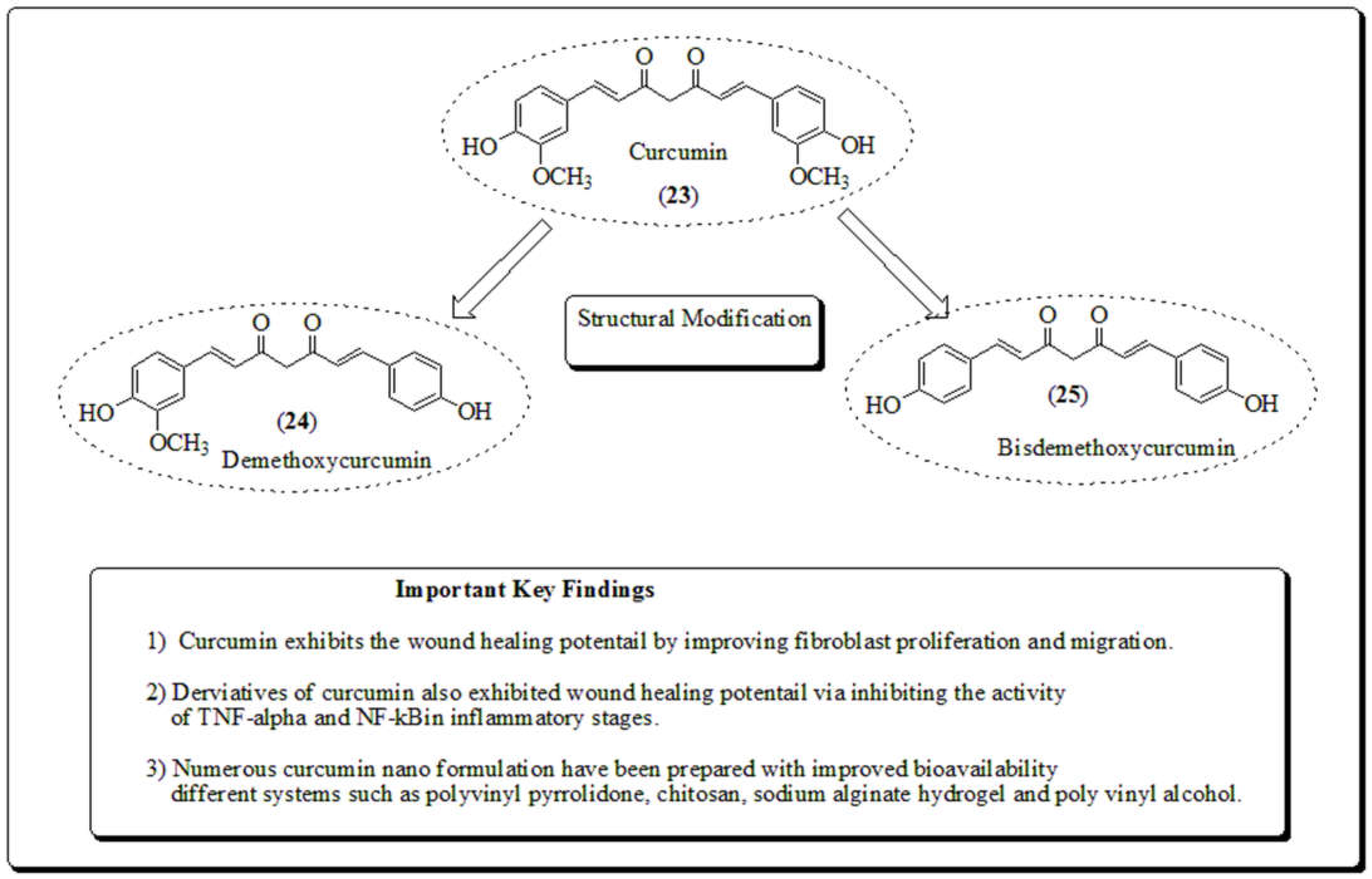

3.8. Ehretia laevis

3.9. Ehretia microphylla

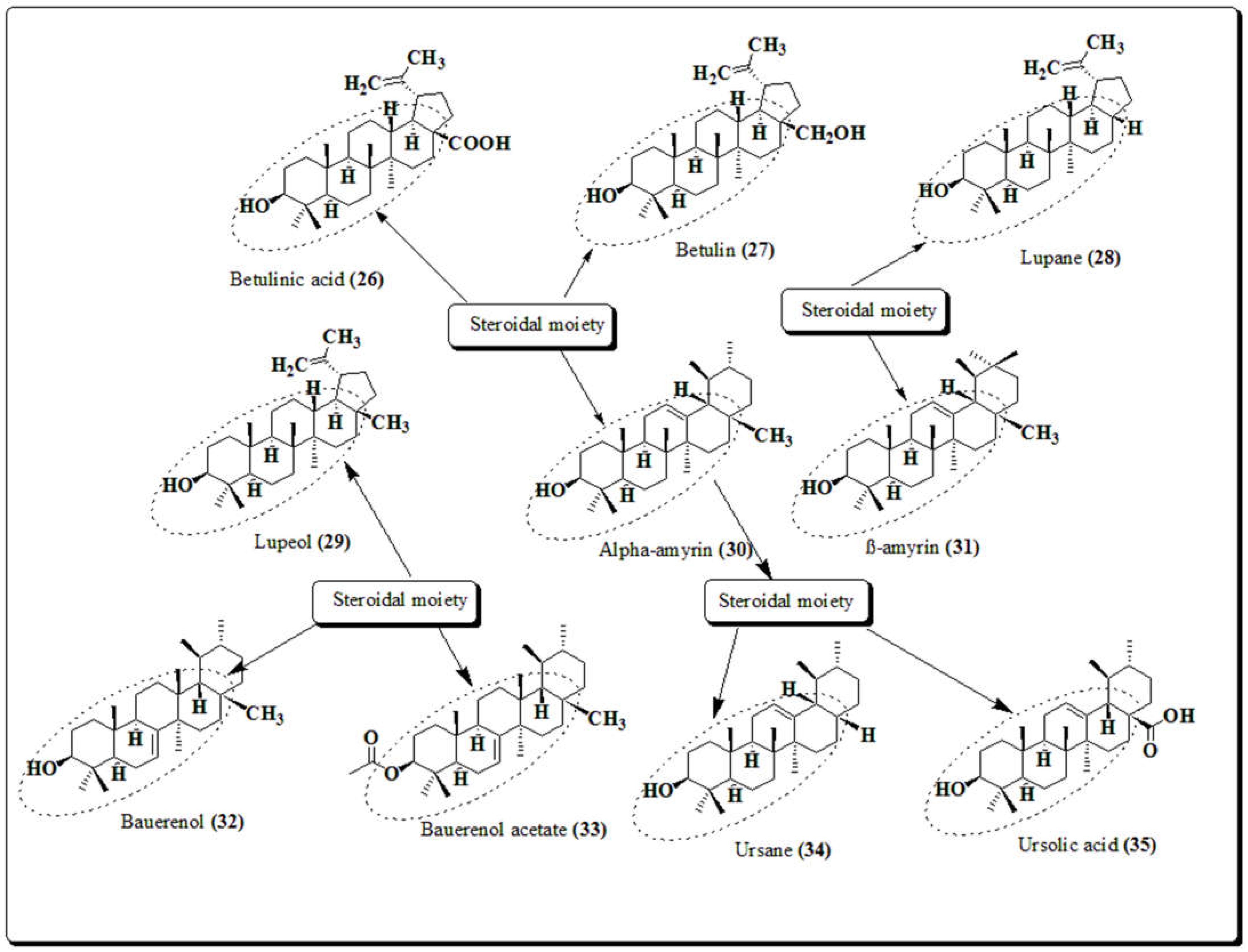

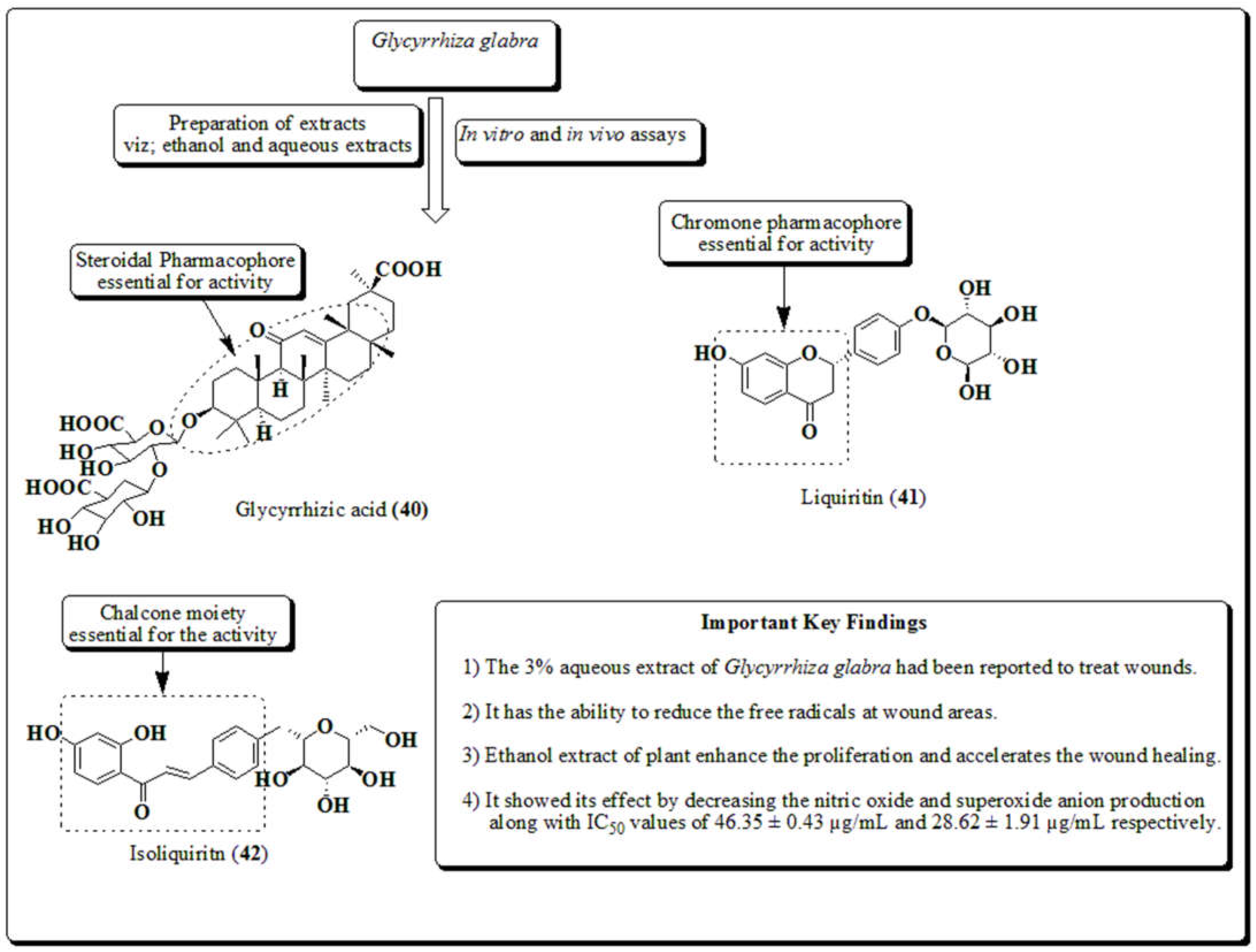

3.10. Glycyrrhiza glabra

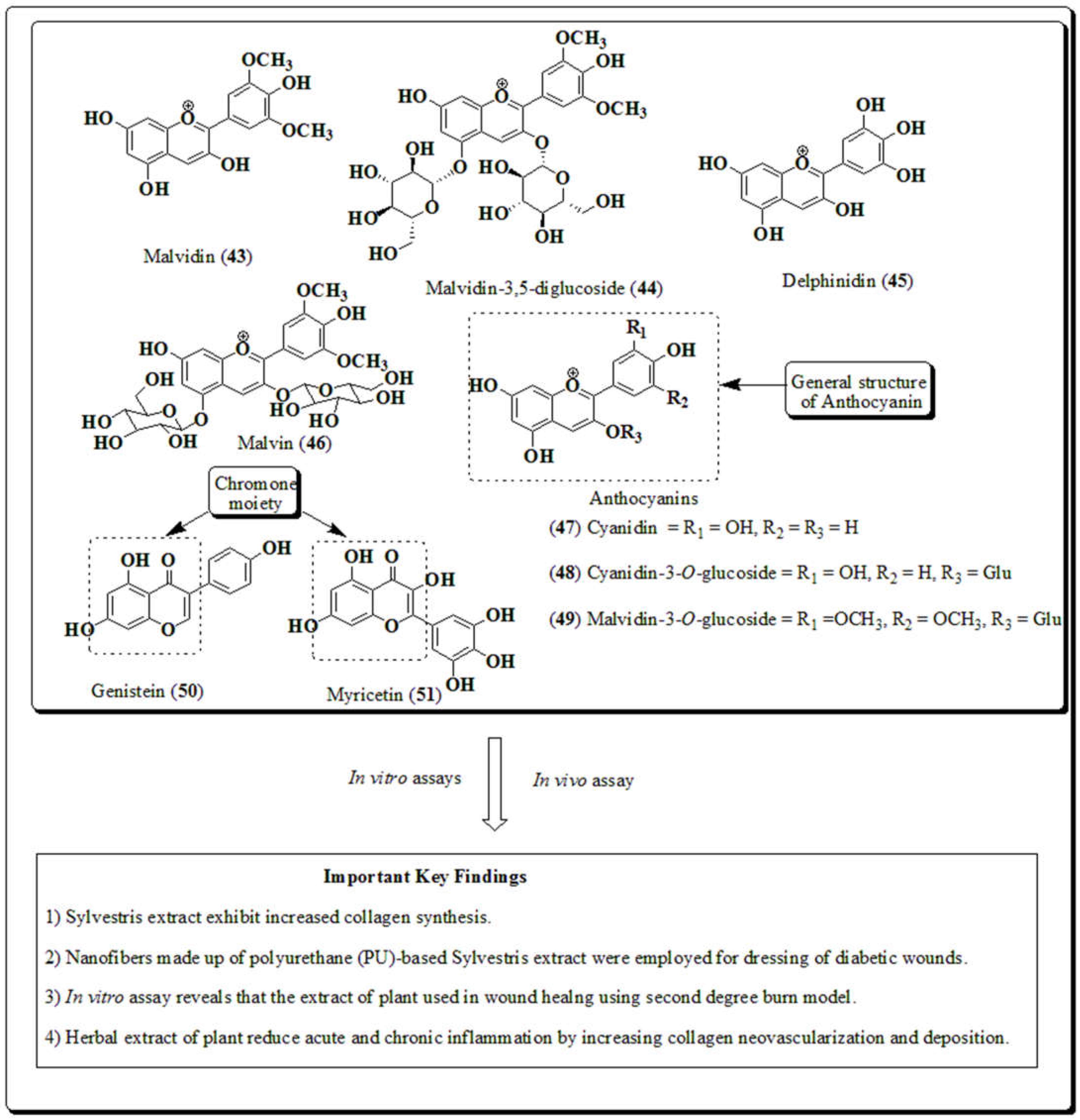

3.11. Malva sylvestris

3.12. Rosmarinus officinalis

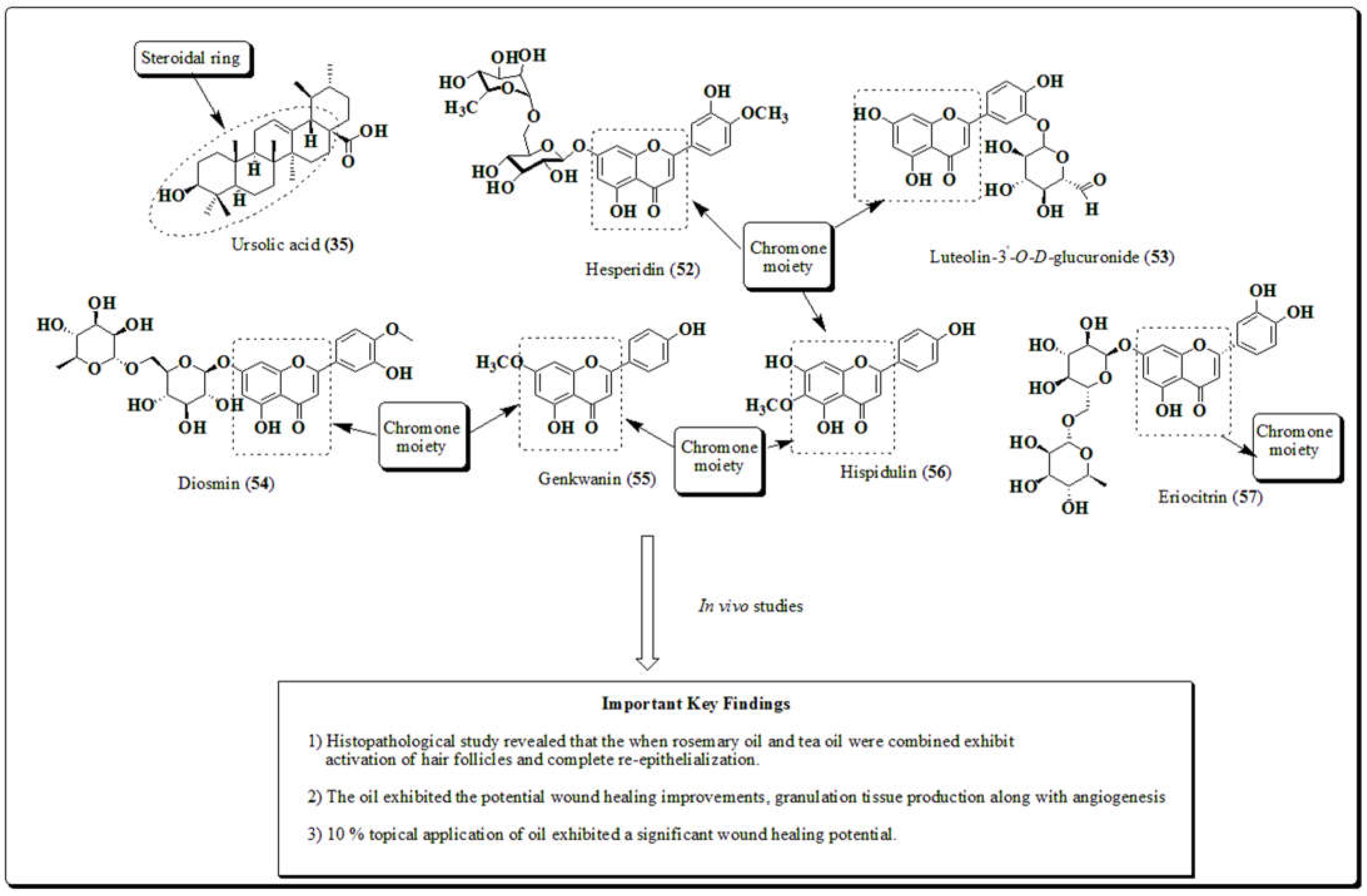

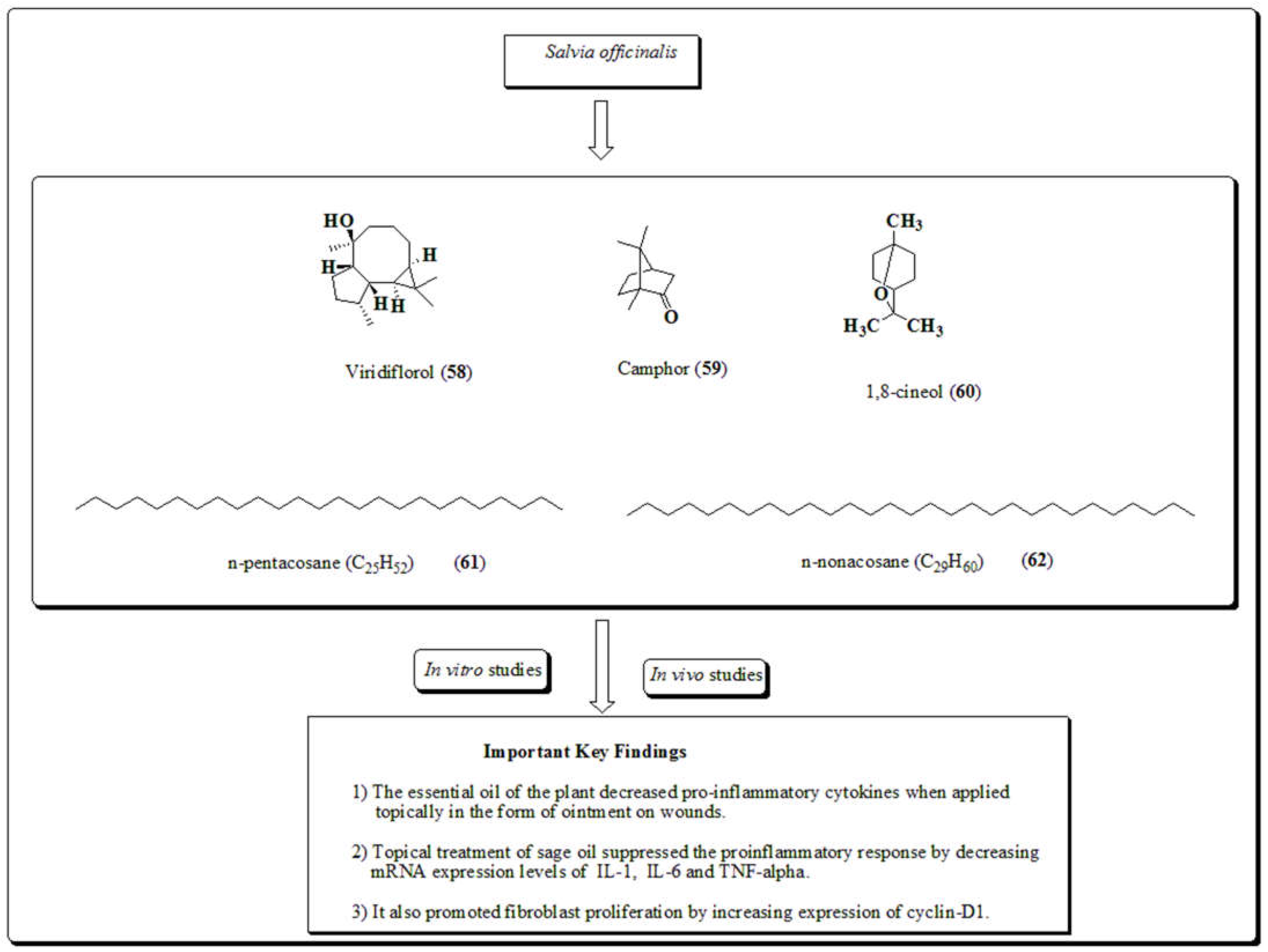

3.13. Salvia officinalis

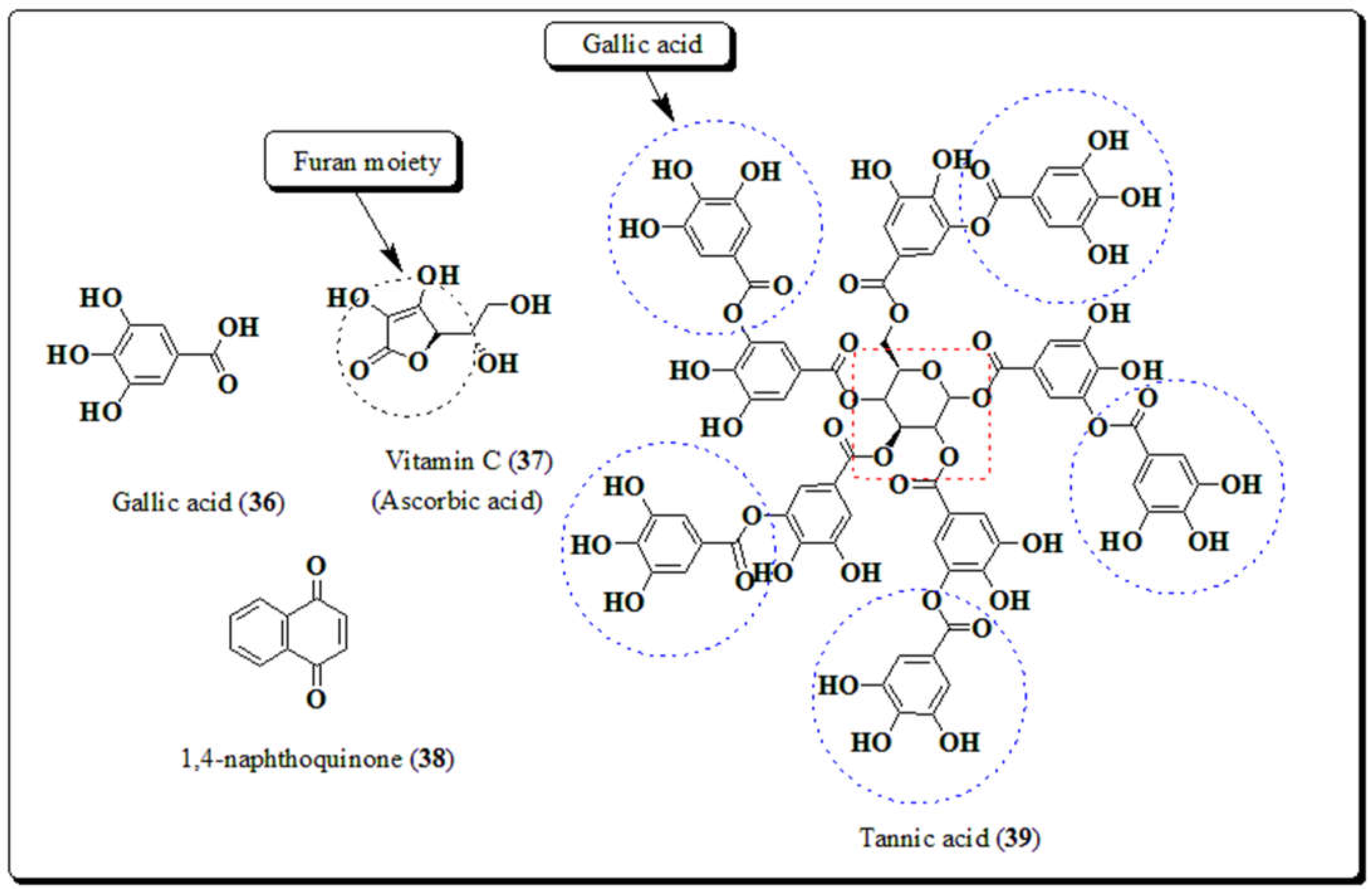

3.14. Miscellaneous

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Janis, J.E.; Harrison, B. Wound Healing: Part I. Basic Science. Plast. Reconstr. Surg. 2016, 138, 199e–207e. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Broughton, G.; Janis, J.E.; Attinger, C.E. The Basic Science of Wound Healing. Plast. Reconstr. Surg. 2006, 117, 12S–34S. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiaolong, M.; Neil, H.R. Cancer is a functional repair tissue. Med. Hypotheses. 2006, 66, 486–490. [Google Scholar]

- Martins-Green, M.; Boudreau, N.; Bissell, M.J. Inflammation is responsible for the development of wound-induced tumors in chickens infected with Rous sarcoma virus. . 1994, 54, 4334–41. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, S.; Umezu-Goto, M.; Murph, M.; Lu, Y.; Liu, W.; Zhang, F.; Yu, S.; Stephens, L.C.; Cui, X.; Murrow, G.; et al. Expression of Autotaxin and Lysophosphatidic Acid Receptors Increases Mammary Tumorigenesis, Invasion, and Metastases. Cancer Cell 2009, 15, 539–550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, S.; Murph, M.; Panupinthu, N.; Mills, G.B. ATX-LPA receptor axis in inflammation and cancer. Cell Cycle 2009, 8, 3695–3701. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Okada, Y. Expression of fos family and jun family proto-oncogenes during corneal epithelial wound healing. Curr. Eye Res. 1996, 15, 824–832. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anderson, M.W. Role of proto-oncogene activation in carcinogenesis. Environ. Health Perspect. 1992, 98, 13–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meden, H. Elevated serum levels of a c-erbB-2 oncogene product in ovarian cancer patients and in pregnancy. J. Cancer Res. Clin. Oncol. 1994, 120, 378–381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abitbol, M.; Delezoide, A.-L.; Pelet, A.; Amiel, J.; Pachnis, V.; Munnich, A.; Lyonnet, S.; Vekemans, M.; Attié-Bitach, T.; Gérard, M.; et al. Expression of theRET proto-oncogene in human Embryos. Am. J. Med Genet. 1998, 80, 481–486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quenby, S.; Gazvani, M.; Brazeau, C.; Neilson, J.; Lewis-Jones, D.; Vince, G. Oncogenes and tumour suppressor genes in first trimester human fetal gonadal development. Mol. Hum. Reprod. 1999, 5, 737–741. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stiles, C.D. The biological role of oncogenes--insights from platelet-derived growth factor: Rhoads Memorial Award lecture. . 1985, 45, 5215–5218. [Google Scholar]

- Virchow, R.; Virchow, R. Aetiologie der neoplastischen Geschwulste/Pathogenie der neoplastischen Geschwulste. Verlag von, Hirschwald, Berlin, Germany, 1863.

- Matthias, S.; Werner, S. Cancer as an overhealing wound: an old hypothesis revisited, Nature reviews, Mol. Cell Biol. 2008, 9, 628–638. [Google Scholar]

- Haddow, A. Molecular repair, wound healing, and carcinogenesis: tumor production a possible over healing? Adv. Cancer Res. 1972, 16, 181–234. [Google Scholar]

- Dvorak, H.F. Tumors: wounds that do not heal. Similarities between tumor stroma generation and wound healing. N. Engl. J. Med. 1986, 315, 1650–1659. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dolberg, D.S.; Hollingsworth, R.; Hertle, M.; Bissell, M.J. Wounding and Its Role in RSV-Mediated Tumor Formation. Science 1985, 230, 676–678. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Emerich, S. Induction of preneoplastic lung lesions in guinea pigs by cigarette smoke inhalation and their exacerbation by high dietary levels of vitamins C and E. Carcinogenesis, 2005, 26, 605–612. [Google Scholar]

- Platz, E.A.; De Marzo, A.M. Epidemiology of Inflammation and Prostate Cancer. J. Urol. 2004, 171, S36–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eming, S.A.; Krieg, T.; Davidson, J.M. Inflammation in Wound Repair: Molecular and Cellular Mechanisms. J. Investig. Dermatol. 2007, 127, 514–525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dahiya, R.; Lee, C.; Haughney, P.C.; Chui, R.; Ho, R.; Deng, G. Differential gene expression of transforming growth factors alpha and beta, epidermal growth factor, keratinocyte growth factor and their receptors in fetal and adult human prostatic tissues and cancer cell lines. Urology 1996, 48, 963–970. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martinez-Jaramillo, G. In vitro proliferation and expansion of hematopoietic progenitors present in mobilized peripheral blood from normal subjects and cancer patients. Stem Cells Develop. 2004, 13, 382–389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ouahes, N.; Phillips, T.J.; Park, H.-Y. Expression of c-fos and c-Ha-ras Proto-oncogenes is Induced in Human Chronic Wounds. Dermatol. Surg. 1998, 24, 1354–1358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, D.; Sharma, P.; Singh, H.; Nepali, K.; Gupta, G.K.; Jain, S.K.; Ntie-Kang, F. The value of pyrans as anticancer scaffolds in medicinal chemistry. RSC Adv. 2017, 7, 36977–36999. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, D.; Jain, S.K. A Comprehensive Review of N-Heterocycles as Cytotoxic Agents. Curr. Med. Chem. 2016, 23, 4338–4394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaur, R.; Sharma, P.; Gupta, G.K.; Ntie-Kang, F.; Kumar, D. Structure-Activity-Relationship and Mechanistic Insights for Anti-HIV Natural Products. Molecules 2020, 25, 2070. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, D.; Sharma, P.; Shabu; Kaur, R. ; Lobe, M.M.M.; Gupta, G.K.; Ntie-Kang, F. In search of therapeutic candidates for HIV/AIDS: rational approaches, design strategies, structure–activity relationship and mechanistic insights. RSC Adv. 2021, 11, 17936–17964. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, P.; Kumar, D.; Shri, R.; Kumar, S. Mechanistic Insights and Docking Studies of Phytomolecules as Potential Candidates in the Management of Cancer. Curr. Pharm. Des. 2022, 28, 2704–2724. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singla, R.K.; Sharma, P.; Dubey, A.K.; Gundamaraju, R.; Kumar, D.; Kumar, S.; Madaan, R.; Shri, R.; Tsagkaris, C.; Parisi, S.; et al. Natural Product-Based Studies for the Management of Castration-Resistant Prostate Cancer: Computational to Clinical Studies. Front. Pharmacol. 2021, 12, 732266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Singla, R.K.; Sharma, P.; Kumar, D.; Gautam, R.K.; Goyal, R.; Tsagkaris, C.; Dubey, A.K.; Bansal, H.; Sharma, R.; Shen, B. The role of nanomaterials in enhancing natural product translational potential and modulating endoplasmic reticulum stress in the treatment of ovarian cancer. Front. Pharmacol. 2022, 13, 987088. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, P.; Shri, R.; Ntie-Kang, F.; Kumar, S. Phytochemical and Ethnopharmacological Perspectives of Ehretia laevis. Molecules 2021, 26, 3489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, B.; Vijayakumar, M.; Govindarajan, R.; Pushpangadan, P. Ethnopharmacological approaches to wound healing—Exploring medicinal plants of India. J. Ethnopharmacol. 2007, 114, 103–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Biswas, T.K.; Mukherjee, B. Plant Medicines of Indian Origin for Wound Healing Activity: A Review. Int. J. Low. Extremity Wounds 2003, 2, 25–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matsuda, H.; Morikawa, T.; Ando, S.; Toguchida, I.; Yoshikawa, M. Structural Requirements of Flavonoids for Nitric Oxide Production Inhibitory Activity and Mechanism of Action. Bioorganic Med. Chem. 2003, 11, 1995–2000. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Claude, A.C.; Jean, C.L.; Patric, T.; Christelle, P.; Gerard, H.; Albert, J.C.; Jean, L.D. Chalcones: Structural requirements for antioxidant, estrogenic and antiproliferative activities. Anticancer Res. 2001, 21, 3949–3956. [Google Scholar]

- Kumar, D.; Nepali, K.; Bedi, P.; Kumar, S.; Malik, F.; Jain, S. 4,6-diaryl Pyrimidones as Constrained Chalcone Analogues: Design, Synthesis and Evaluation as Antiproliferative Agents. Anti-Cancer Agents Med. Chem. 2015, 15, 793–803. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Middleton, E.J.V.R. Effect of plant flavonoids on immune and inflammatory cell function. Adv. Exp. Med. Biol. 1998, 439, 175–182. [Google Scholar]

- Kumar, D.; Singh, O.; Nepali, K.; Bedi, P.M.S.; Qayum, A.; Singh, S.; Jain, S.K. Naphthoflavones as Anti-proliferative Agents: Design, Synthesis and Biological Evaluation. Anticancer Agents Med. Chem. 2016, 16, 881–890. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, D.; Malik, F.; Bedi, P.M.S.; Subheet, J. 2,4-diarylpyrano[3,2-c]chromen-5(4H)-ones as coumarin-chalcone conjugates : Design, synthesis and biological evaluation as apoptosis inducing agents. Chem. Pharm. Bull. 2016, 64, 399–409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vitale, S.; Colanero, S.; Placidi, M.; Di Emidio, G.; Tatone, C.; Amicarelli, F.; D’alessandro, A.M. Phytochemistry and Biological Activity of Medicinal Plants in Wound Healing: An Overview of Current Research. Molecules 2022, 27, 3566. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mehta, P.; Shah, R.; Lohidasan, S.; Mahadik, K. Pharmacokinetic profile of phytoconstituent(s) isolated from medicinal plants—A comprehensive review. J. Tradit. Complement. Med. 2015, 5, 207–227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maver, T.; Maver, U.; Kleinschek, K.S.; Smrke, D.M.; Kreft, S. A review of herbal medicines in wound healing. Int. J. Dermatol. 2015, 54, 740–751. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rathi, B.S.; Bodhankar, S.; Baheti, A. Evaluation of aqueous leaves extract of Moringa oleifera Linn for wound healing in albino rats. . 2006, 44, 898–901. [Google Scholar]

- Nayak, B.; Pereira, L.M.P. Catharanthus roseus flower extract has wound-healing activity in Sprague Dawley rats. BMC Complement. Altern. Med. 2006, 6, 41–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ovais, M.; Khalil, A.T.; Islam, N.U.; Ahmad, I.; Ayaz, M.; Saravanan, M.; Shinwari, Z.K.; Mukherjee, S. Role of plant phytochemicals and microbial enzymes in biosynthesis of metallic nanoparticles. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2018, 102, 6799–6814. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Long, V. Aloe Vera in Dermatology—The Plant of Immortality. JAMA Dermatol. 2016, 152, 1364–1364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeng, W.M.; Parus, A.; Barnes, C.W.; Hiro, M.E.; Robson, M.C.; Payne, W.G. Aloe vera—Mechanisms of Action, Uses, and Potential Uses in Plastic Surgery and Wound Healing. Surg. Sci. 2020, 11, 312–328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sánchez-Machado, D.I.; López-Cervantes, J.; Sendón, R.; Sanches-Silva, A. Aloe vera : Ancient knowledge with new frontiers. Trends Food Sci. Technol. 2017, 61, 94–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salehi, B.; Albayrak, S.; Antolak, H.; Kr˛egiel, D.; Pawlikowska, E.; Sharifi-Rad, M.; Uprety, Y.; Tsouh Fokou, P.V.; Yousef, Z.; Amiruddin Zakaria, Z. Aloe Genus Plants: From Farm to Food Applications and Phytopharmacotherapy. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2018, 19, 2843–2852. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hormozi, M.; Assaei, R.; Boroujeni, M.B. The Effect of Aloe vera on the Expression of Wound Healing Factors (TGF_1 and BFGF) in Mouse Embryonic Fibroblast Cell: In Vitro Study. Biomed. Pharmacother. 2017, 88, 610–616. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wahedi, H.M.; Jeong, M.; Chae, J.K.; Gil Do, S.; Yoon, H.; Kim, S.Y. Aloesin from Aloe vera accelerates skin wound healing by modulating MAPK/Rho and Smad signaling pathways in vitro and in vivo. Phytomedicine 2017, 28, 19–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yamao, M.; Naoki, H.; Kunida, K.; Aoki, K.; Matsuda, M.; Ishii, S. Distinct predictive performance of Rac1 and Cdc42 in cell migration. Sci. Rep. 2015, 5, 17527. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- De Oliveira, A.C.L.; Tabrez, S.; Shakil, S.; Khan, M.I.; Asghar, M.N.; Matias, B.D.; da Silva Batista, J.M.A.; Rosal, M.M.; de Lima, M.M.D.F.; Gomes, S.R.F. Mutagenic, Antioxidant andWound Healing Properties of Aloe vera. J. Ethnopharmacol. 2018, 227, 191–197. [Google Scholar]

- Oliveira, R.N.; Mancini, M.C.; De Oliveira, F.C.S.; Passos, T.M.; Quilty, B.; Da Silva Moreira Thiré, R.M.; McGuinness, G.B. FTIR analysis and quantification of phenols and flavonoids of five commercially available plants extracts used in wound healing. Matéria 2016, 21, 767–779. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teplicki, E.; Ma, Q.; Castillo, D.E.; Zarei, M.; Hustad, A.P.; Chen, J.; Li, J. The Effects of Aloe vera on Wound Healing in Cell Proliferation, Migration, and Viability. Wounds Compend. Clin. Res. Pract. 2018, 30, 263–268. [Google Scholar]

- Rossiter, H.; Barresi, C.; Pammer, J.; Rendl, M.; Haigh, J.; Wagner, E.F.; Tschachler, E. Loss of Vascular Endothelial Growth Factor A Activity in Murine Epidermal Keratinocytes Delays Wound Healing and Inhibits Tumor Formation. Cancer Res 2004, 64, 3508–3516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chantarawaratit, P.; Sangvanich, P.; Banlunara, W.; Soontornvipart, K.; Thunyakitpisal, P. Acemannan sponges stimulate alveolar bone, cementum and periodontal ligament regeneration in a canine class II furcation defect model. J. Periodontal Res. 2013, 49, 164–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xing, W.; Guo, W.; Zou, C.-H.; Fu, T.-T.; Li, X.-Y.; Zhu, M.; Qi, J.-H.; Song, J.; Dong, C.-H.; Li, Z.; et al. Acemannan accelerates cell proliferation and skin wound healing through AKT/mTOR signaling pathway. J. Dermatol. Sci. 2015, 79, 101–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cavalcanti, A.M.; Baggio, C.H.; Freitas, C.S.; Rieck, L.; de Sousa, R.S.; Da Silva-Santos, J.E.; Mesia-Vela, S.; Marques, M.C.A. Safety and antiulcer efficacy studies of Achillea millefolium L. after chronic treatment in Wistar rats. J. Ethnopharmacol. 2006, 107, 277–284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Benedek, B.; Kopp, B. Achillea millefolium L. s.l. revisited: Recent findings confirm the traditional use. Wien. Med. Wochenschr. 2007, 157, 312–314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chavez-Silva, F.; Ceron-Romero, L.; Arias-Duran, L.; Navarrete-Vazquez, G.; Almanza-Perez, J.; Roman-Ramos, R.; Ramirez-Ávila, G.; Perea-Arango, I.; Villalobos-Molina, R.; Estrada-Soto, S. Antidiabetic Effect of Achillea millefollium through Multitarget Interactions: Glucosidases Inhibition, Insulin Sensitization and Insulin Secretagogue Activities. J. Ethnopharmacol. 2018, 212, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ali, S.I.; Gopalakrishnan, B.; Venkatesalu, V. Pharmacognosy, Phytochemistry and Pharmacological Properties of Achillea millefolium L. : A Review. Phytother. Res. 2017, 31, 1140–1161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nemeth, E. Essential Oil Composition of Species in the GenusAchillea. J. Essent. Oil Res. 2005, 17, 501–512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nemeth, E.; Bernath, J. Biological Activities of Yarrow Species (Achillea spp.). Curr. Pharm. Des. 2008, 14, 3151–3167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bakkali, F.; Averbeck, S.; Averbeck, D.; Idaomar, M. Biological Effects of Essential Oils-A Review. Food Chem. Toxicol. 2008, 46, 446–475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vitalini, S.; Beretta, G.; Iriti, M.; Orsenigo, S.; Basilico, N.; Dall’Acqua, S.; Iorizzi, M.; Fico, G. Phenolic compounds from Achillea millefolium L. and their bioactivity. Acta Biochim. Pol. 2011, 58, 203–209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tadic, V.; Arsic, I.; Zvezdanovic, J.; Zugic, A.; Cvetkovic, D.; Pavkov, S. The Estimation of the Traditionally Used Yarrow (Achillea millefolium L. Asteraceae) Oil Extracts with Anti-Inflammatory Potential in Topical Application. J. Ethnopharmacol. 2017, 199, 138–148. [Google Scholar]

- Dorjsembe, B.; Lee, H.J.; Kim, M.; Dulamjav, B.; Jigjid, T.; Nho, C.W. Achillea asiatica extract and its active compounds induce cutaneous wound healing. J. Ethnopharmacol. 2017, 206, 306–314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Akbar, S. Andrographis paniculata: a review of pharmacological activities and clinical effects. Alternative Medicine Review 2011, 16, 66–77. [Google Scholar]

- Kabir, M.H.; Hasan, N.; Rahman, M.; Rahman, A.; Alam Khan, J.; Hoque, N.T.; Bhuiyan, R.Q.; Mou, S.M.; Jahan, R.; Rahmatullah, M. A survey of medicinal plants used by the Deb barma clan of the Tripura tribe of Moulvibazar district, Bangladesh. J. Ethnobiol. Ethnomedicine 2014, 10, 19–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, R.A.; Sridevi, K.; Kumar, N.V.; Nanduri, S.; Rajagopal, S. Anticancer and immune stimulatory compounds from Andrographis paniculata. J. Ethnopharmacol. 2004, 92, 291–295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, L.X.; He, H.; Xia, G.Y.; Zhou, K.L.; Qiu, F. A new flavonoid from the aerial parts of Andrographis paniculata. Nat. Prod. Res. 2014, 28, 138–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Adedapo, A.A.; Adeoye, B.O.; Sofidiya, M.O.; Oyagbemi, A.A. Antioxidant, antinociceptive and anti-inflammatory properties of the aqueous and ethanolic leaf extracts of Andrographis paniculata in some laboratory animals. J. Basic Clin. Physiol. Pharmacol. 2014, 26, 327–334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Al-Bayaty, F.H.; Abdulla, M.A.; Hassan, M.I.A.; Ali, H.M. Effect of Andrographis paniculata leaf extract on wound healing in rats. Nat. Prod. Res. 2012, 26, 423–429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shamsizadeh, A.; Roohbakhsh, A.; Ayoobi, F.; Moghaddamahmadi, A. The role of natural products in the prevention and treatment of multiple sclerosis, in Nutrition and Lifestyle in Neurological Autoimmune Diseases, Watson, R.R.; Killgore, W.D.S.; Eds., Academic Press, Cambridge, MA, USA, 2017, pp. 249–260.

- Shedoeva, A.; David, L.; Upton, Z.; Chen, F. Wound Healing and the Use of Medicinal Plants. Evid.-Based Complement. Altern. Med. 2019, 1-30.

- Ammon, H.P.T. Boswellic Acids in Chronic Inflammatory Diseases. Planta Medica 2006, 72, 1100–1116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Glaser, T.; Winter, S.; Groscurth, P.; Safayhi, H.; Sailer, E.-R.; Ammon, H.P.T.; Schabet, M.; Weller, M. Boswellic acids and malignant glioma: induction of apoptosis but no modulation of drug sensitivity. Br. J. Cancer 1999, 80, 756–765. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, J.-J.; Nilsson. ; Oredsson, S.; Badmaev, V.; Zhao, W.-Z.; Duan, R.-D. Boswellic acids trigger apoptosis via a pathway dependent on caspase-8 activation but independent on Fas/Fas ligand interaction in colon cancer HT-29 cells. Carcinog. 2002, 23, 2087–2093. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nicolaus, C.; Junghanns, S.; Hartmann, A.; Murillo, R.; Ganzera, M.; Merfort, I. In vitro studies to evaluate the wound healing properties of Calendula officinalis extracts. J. Ethnopharmacol. 2017, 196, 94–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Leach, M.J. Calendula officinalis and Wound Healing: A Systematic Review. . 2008, 20, 236–243. [Google Scholar]

- Muley, B.; Khadabadi, S.; Banarase, N. Phytochemical Constituents and Pharmacological Activities of Calendula officinalis Linn (Asteraceae): A Review. Trop. J. Pharm. Res. 2009, 8, 455–465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arora, D.; Rani, A.; Sharma, A. A review on phytochemistry and ethnopharmacological aspects of genus Calendula. Pharmacogn. Rev. 2013, 7, 179–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shafeie, N.; Naini, A.T.; Jahromi, H.K. Comparison of Different Concentrations of Calendula officinalis Gel on CutaneousWound Healing. Biomed. Pharmacol. J. 2015, 8, 979–992. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Givol, O.; Kornhaber, R.; Visentin, D.; Cleary, M.; Haik, J.; Harats, M. A systematic review of Calendula officinalis extract for wound healing. Wound Repair Regen. 2019, 27, 548–561. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Oliveira, R.N.; Mancini, M.C.; De Oliveira, F.C.S.; Passos, T.M.; Quilty, B.; Da Silva Moreira Thiré, R.M.; McGuinness, G.B. FTIR analysis and quantification of phenols and flavonoids of five commercially available plants extracts used in wound healing. Matéria 2016, 21, 767–779. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fronza, M.; Heinzmann, B.; Hamburger, M.; Laufer, S.; Merfort, I. Determination of the wound healing effect of Calendula extracts using the scratch assay with 3T3 fibroblasts. J. Ethnopharmacol. 2009, 126, 463–467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dinda, M.; Dasgupta, U.; Singh, N.; Bhattacharyya, D.; Karmakar, P. PI3K-Mediated Proliferation of Fibroblasts by Calendula officinalis Tincture: Implication in Wound Healing. Phytotherapy Res. 2015, 29, 607–616. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dinda, M.; Mazumdar, S.; Das, S. Water fraction of Calendula officinalis hydroethanol extract stimulates in vitro and in vivo proliferation of dermal fibroblasts in wound healing. Phytotherap. Res. 2016, 30, 1696–1707. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, R.; Singh, V.; Devi, K.; Sharma, M.; Singh, M.K.; Ahuja, P.S. State of Art of Saffron (Crocus sativus L. ) Agronomy: A Comprehensive Review. Food Rev. Int. 2008, 25, 44–85. [Google Scholar]

- Christodoulou, E.; Kadoglou, N.P.; Kostomitsopoulos, N.; Valsami, G. Saffron: a natural product with potential pharmaceutical applications. J. Pharm. Pharmacol. 2015, 67, 1634–1649. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abu-Izneid, T.; Rauf, A.; Khalil, A.A.; Olatunde, A.; Khalid, A.; Alhumaydhi, F.A.; Aljohani, A.S.M.; Uddin, S.; Heydari, M.; Khayrullin, M.; et al. Nutritional and health beneficial properties of saffron (Crocus sativusL): a comprehensive review. Crit. Rev. Food Sci. Nutr. 2020, 62, 2683–2706. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alonso, G.L.; Zalacain, A.; Carmona, M. Saffron. In Handbook of Herbs and Spices, Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2012; pp. 469–498.

- Del-Angel, D.; Martínez, N.; Cruz, M.; Urrutia, E.; Riverón-Negrete, L.; Abdullaev, F. SAFFRON EXTRACT AMELIORATES OXIDATIVE DAMAGE AND MITOCHONDRIAL DYSFUNCTION IN THE RAT BRAIN. Acta Hortic. 2007, 359–366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cerdá-Bernad, D.; Valero-Cases, E.; Pastor, J.-J.; Frutos, M.J. Saffron bioactives crocin, crocetin and safranal: effect on oxidative stress and mechanisms of action. Crit. Rev. Food Sci. Nutr. 2020, 62, 3232–3249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nanda, S.; Madan, K. The role of Safranal and saffron stigma extracts in oxidative stress, diseases and photoaging: A systematic review. Heliyon 2021, 7, e06117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, S.; Liu, X.; Lei, J.; Yang, J.; Tian, P.; Gao, Y. Crocin Protects Podocytes Against Oxidative Stress and Inflammation Induced by High Glucose Through Inhibition of NF-KB. Cell Physiol. Biochem. 2017, 42, 1481–1492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Festuccia, C.; Mancini, A.; Gravina, G.L.; Scarsella, L.; Llorens, S.; Alonso, G.L.; Tatone, C.; Di Cesare, E.; Jannini, E.A.; Lenzi, A.; et al. Antitumor Effects of Saffron-Derived Carotenoids in Prostate Cancer Cell Models. BioMed Res. Int. 2014, 2014, 45–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Colapietro, A.; Mancini, A.; D'Alessandro, A.M.; Festuccia, C. Crocetin and Crocin from Saffron in Cancer Chemotherapy and Chemoprevention. Anti-Cancer Agents Med. Chem. 2019, 19, 38–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hassan, A. Curcuma Longa, Turmeric: A Monograph. Aust. J. Med. Herbal. 2006, 18, 66–76. [Google Scholar]

- Memarzia, A.; Khazdair, M.R.; Behrouz, S.; Gholamnezhad, Z.; Jafarnezhad, M.; Saadat, S.; Boskabady, M.H. Experimental and Clinical Reports on Anti-Inflammatory, Antioxidant, and Immunomodulatory Effects of Curcuma Longa and Curcumin, an Updated and Comprehensive Review. BioFactors Oxf. Engl. 2021, 47, 311–350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anamika, B. Extraction of Curcumin. J. Env. Sci Toxicol Food Technol 2012, 1, 1–16. [Google Scholar]

- Akbik, D.; Ghadiri, M.; Chrzanowski, W.; Rohanizadeh, R. Curcumin as a wound healing agent. Life Sci. 2014, 116, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ak, T.; Gülçin, I. Antioxidant and radical scavenging properties of curcumin. Chem. Interactions 2008, 174, 27–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thangapazham, R.L.; Sharad, S.; Maheshwari, R.K. Skin regenerative potentials of curcumin. BioFactors 2013, 39, 141–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Barzegar, A.; Moosavi-Movahedi, A.A. Intracellular ROS Protection Efficiency and Free Radical-Scavenging Activity of Curcumin. PLoS ONE 2011, 6, e26012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Panchatcharam, M.; Miriyala, S.; Gayathri, V.S.; Suguna, L. Curcumin improves wound healing by modulating collagen and decreasing reactive oxygen species. Mol. Cell. Biochem. 2006, 290, 87–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yen, Y.H.; Pu, C.M.; Liu, CW.; Chen, Y.C.; Chen, Y.C.; Liang, C.J.; Hsieh, J.H.; Huang, H.F.; Chen, Y.L. Curcumin accelerates cutaneous wound healing via multiple biological actions: The involvement of TNF-α, MMP-9, α-SMA, and collagen, Int Wound J. 2018, 15, 605–617.

- Mohanty, C.; Das, M.; Sahoo, S.K. Emerging role of nanocarriers to increase the solubility and bioavailability of curcumin. Expert Opin. Drug Deliv. 2012, 9, 1347–1364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pandey, V.K.; Ajmal, G.; Upadhyay, S.N.; Mishra, P.K. Nano-fibrous scaffold with curcumin for anti-scar wound healing. Int. J. Pharm. 2020, 589, 119858. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rao, M.; Kumar, P.; Das, B. Comparative study of efficacy of Jatyadi Ghrita Pichu and Yasthimadhu Ghrita Pichu in the management of parikartika (fissure-in-ano). Int. J. Ayurveda Pharma Res. 2016, 4, 1–9. [Google Scholar]

- Meena, K.L.; Yadav, B.L. Some ethnomedicinal plants used by the Garasia tribe of Siroh, Rajasthan. Indian J. Trad. Knowl. 2011, 10, 354–357. [Google Scholar]

- Samantaray, S.; Bishwal, R.; Singhai, S. Clinical efficacy of jatyadi taila in parikartika (fissure-in-ano). World J. Pharm. Med. Res. 2017, 3, 250–254. [Google Scholar]

- Tichkule, S.V.; Khandare, K.B.; Shrivastav, P.P. Proficiency of Khanduchakka Ghrit in the management of Parikartika: A case report. J. Indian Syst. Med. 2019, 4, 47–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tafere, Y.; Chanie, S.; Dessie, T.; Gedamu, H. Assessment of prevalence of dental caries and the associated factors among patients attending dental clinic in Debre Tabor general hospital: a hospital-based cross-sectional study. BMC Oral Heal. 2018, 18, 119–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deshpande, R.; Walimbe, H.; Jadhav, M.; Deshpande, N.; Devare, S. Comparative evaluation of antimicrobial activity of various extracts of ‘Morinda pubescens’ in different concentration on human salivary microflora. Int. J. Pharm. Pharm. Sci. 2013, 5, 910–912. [Google Scholar]

- Cagampan, D.; Lacuata, K.; Ples, M.; Ii, R. Effect of Ehretia microphylla on the blood cholesterol and weight of ICR mice (Mus musculus). Natl. J. Physiol. Pharm. Pharmacol. 2018, 8, 983–987. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Demetrio, L.V.J.; Jeannie, I.A.; Juliana, J.M.P.; Esperanza, C.C.; Windell, L.R. Antibacterial activities of ethanol extracts of Philippine medicinal plants against multidrug-resistant bacteria. Asian Pac. J. Trop. Biomed. 2015, 5, 532–540. [Google Scholar]

- Murugesa, M.K.S. Gunapadam. Part-I; Tamil Nadu Siddha Medical Board: Chennai, India, 1956; pp. 274–280. [Google Scholar]

- Roeder, E.; Wiedenfeld, H. Plants containing pyrrolizidine alkaloids used in the traditional Indian medicine--including ayurveda. . 2013, 68, 83–92. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Vista, F.E.S.; Dalmacio, L.M.M.; Corales, L.G.M.; Salem, G.M.; Galula, J.U.; Chao, D.Y. Antiviral Effect of Crude Aqueous Extracts from Ten Philippine Medicinal Plants against Zika virus. Acta Med. Phillipin. 2022, 54, 195–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Safe, S.H.; Prather, P.L.; Brents, L.K.; Chadalapaka, G.; Jutooru, I. Unifying Mechanisms of Action of the Anticancer Activities of Triterpenoids and Synthetic Analogs. Anti-Cancer Agents Med. Chem. 2012, 12, 1211–1220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sharma, P.; Shri, R.; Kumar, S. Phytochemical and In Vitro Cytotoxic Screening of Chloroform Extract of Ehretia microphylla Lamk. Stresses 2022, 2, 384–394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Komes, D.; Belščak-Cvitanović, A.; Jurić, S.; Bušić, A.; Vojvodić, A.; Durgo, K. Consumer acceptability of liquorice root (Glycyrrhiza glabraL.) as an alternative sweetener and correlation with its bioactive content and biological activity. Int. J. Food Sci. Nutr. 2015, 67, 53–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jeon, J.S.; Kim, H.T.; Kim, M.G.; Oh, M.S.; Hong, S.R.; Yoon, M.H.; Shin, H.C.; Shim, J.H.; Afifi, N.A.; Hacımuftuo glu, A.; et al. Simultaneous Detection of Glabridin, (-), α-Bisabolol, and Ascorbyl Tetraisopalmitate in Whitening Cosmetic Creams Using HPLC-PAD. Chromatographia 2016, 79, 851–860. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pastorino, G.; Cornara, L.; Soares, S.; Rodrigues, F.; Oliveira, M.B.P.P. Liquorice (Glycyrrhiza glabra): A phytochemical and pharmacological review. Phytother. Res. 2018, 32, 2323–2339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Memariani, Z.; Hajimahmoodi, M.; Minaee, B.; Khodagholi, F.; Yans, A.; Rahimi, R.; Amin, G.; Moghaddam, G.; Toliyat, T.; Sharifzadeh, M. Protective Effect of a Polyherbal Traditional Formula Consisting of Rosa damascena Mill. , Glycyrrhiza glabra L. and Nardostachys jatamansi DC., Against Ethanol-Induced Gastric Ulcer. Iran. J. Pharm. Res. 2017, 16, 694–707. [Google Scholar]

- Al-Refai, A.S.; Najeeb, V.D. Antibacterial effect and healing potential of topically applied licorice root extract on experimentally induced oral wounds in rabbits. Saudi J. Oral Sci. 2015, 2, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, X.; Fang, D.; Li, L.; Chen, L.; Li, Q.; Gong, F.; Fang, M. Glycyrrhizin ameliorates experimental colitis through attenuating interleukin-17-producing T cell responses via regulating antigen-presenting cells. Immunol. Res. 2017, 65, 666–680. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shah, S.L.; Wahid, F.; Khan, N.; Farooq, U.; Shah, A.J.; Tareen, S.; Ahmad, F.; Khan, T. Inhibitory Effects of Glycyrrhiza glabra and Its Major Constituent Glycyrrhizin on Inflammation-Associated Corneal Neovascularization. Evid. Based Complement. Alternat. Med. 2018, 2018, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oloumi, M.M.; Derakhshanfar, A.; Nikpour, A. Healing Potential of Liquorice Root Extract on Dermal Wounds in Rats. J. Vet. Res. 2007, 62, 147–154. [Google Scholar]

- Li, B.; Wang, J.H.-C. Fibroblasts and myofibroblasts in wound healing: Force generation and measurement. J. Tissue Viability 2011, 20, 108–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geethalakshmi, R.; Sakravarthi, C.; Kritika, T.; Kirubakaran, M.A.; Sarada, D.V.L. Evaluation of Antioxidant and Wound Healing Potentials ofSphaeranthus amaranthoidesBurm.f. BioMed Res. Int. 2013, 2013, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zangeneh, A.; Pooyanmehr, M.; Zangeneh, M.M.; Moradi, R.; Rasad, R.; Kazemi, N. Therapeutic effects of Glycyrrhiza glabra aqueous extract ointment on cutaneous wound healing in Sprague Dawley male rats. Comp. Clin. Pathol. 2019, 28, 1507–1514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siriwattanasatorn, M.; Itharat, A.; Thongdeeying, P.; Ooraikul, B. In VitroWound Healing Activities of Three Most Commonly Used Thai Medicinal Plants and Their Three Markers. Evid.-Based Complement. Altern. Med. 2020, 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Barros, L.; Carvalho, A.M.; Ferreira, I.C. Leaves, flowers, immature fruits and leafy flowered stems of Malva sylvestris: A comparative study of the nutraceutical potential and composition. Food Chem. Toxicol. 2010, 48, 1466–1472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Quave, C.L.; Plano, L.R.; Pantuso, T.; Bennett, B.C. Effects of extracts from Italian medicinal plants on planktonic growth, biofilm formation and adherence of methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus. J. Ethnopharmacol. 2008, 118, 418–428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DellaGreca, M.; Cutillo, F.; Abrosca, B.D.; Fiorentino, A.; Pacifico, S.; Zarrelli, A. Antioxidant and Radical Scavenging Properties of Malva Sylvestris. Nat. Prod. Commun. 2009, 4, 893–896. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leporatti, M.L.; Ghedira, K. Comparative analysis of medicinal plants used in traditional medicine in Italy and Tunisia. J. Ethnobiol. Ethnomedicine 2009, 5, 31–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pirbalouti, A.G.; Azizi, S.; Koohpayeh, A.; Hamedi, B. Wound healing activity of Malva sylvestris and Punica granatum in alloxan-induced diabetic rats. . 2010, 67, 511–516. [Google Scholar]

- Pirbalouti, A.G.; Koohpyeh, A. Wound Healing Activity of Extracts of Malva sylvestris and Stachys lavandulifolia. Int. J. Biol. 2010, 3, 174–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gasparetto, J.C.; Martins, C.A.F.; Hayashi, S.S.; Otuky, M.F.; Pontarolo, R. Ethnobotanical and Scientific Aspects of Malva sylvestris L. : A Millennial Herbal Medicine. J. Pharm. Pharmacol. 2012, 64, 172–189. [Google Scholar]

- Mousavi, S.M.; Hashemi, S.A.; Behbudi, G.; Mazraedoost, S.; Omidifar, N.; Gholami, A.; Chiang, W.-H.; Babapoor, A.; Rumjit, N.P. A Review on Health Benefits of Malva sylvestris L. Nutritional Compounds for Metabolites, Antioxidants, and Anti-Inflammatory, Anticancer, and Antimicrobial Applications. Evidence-Based Complement. Altern. Med. 2021, 2021, e5548404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Afshar, M.; Ravarian, B.; Zardast, M.; Moallem, S.A.; Fard, M.H.; Valavi, M. Evaluation of cutaneous wound healing activity of Malva sylvestris aqueous extract in BALB/c mice. . 2015, 18, 616–625. [Google Scholar]

- Nasiri, E.; Hosseinimehr, S.J.; Azadbakht, M.; Akbari, J.; Enayati-Fard, R.; Azizi, S. Effect of Malva sylvestris cream on burn injury and wounds in rats. Avicenna J. phytomed. 2016, 5, 341–354. [Google Scholar]

- Almasian, A.; Najafi, F.; Eftekhari, M.; Ardekani, M.R.S.; Sharifzadeh, M.; Khanavi, M. Polyurethane/carboxymethylcellulose nanofibers containing Malva sylvestris extract for healing diabetic wounds: Preparation, characterization, in vitro and in vivo studies. Mater. Sci. Eng. C 2020, 114, 111039. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mena, P.; Cirlini, M.; Tassotti, M.; Herrlinger, K.A.; Dall’Asta, C.; Del Rio, D. Phytochemical Profiling of Flavonoids, Phenolic Acids, Terpenoids, and Volatile Fraction of a Rosemary (Rosmarinus Officinalis L. ) Extract. Molecules 2016, 21, 1576. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- del Baño, M.J.; Lorente, J.; Castillo, J.; Benavente-García, O.; Marín, M.P.; Del Río, J.A.; Ortuño, A.; Ibarra, I. Flavonoid Distribution during the Development of Leaves, Flowers, Stems, and Roots ofRosmarinus officinalis. Postulation of a Biosynthetic Pathway. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2004, 52, 4987–4992. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Umasankar, K.; Nambikkairaj, B.; Backyavathy, D.M. Effect of Topical Treatment of Rosmarinus Officinalis Essential Oil on Wound Healing in Streptozotocin Induced Diabetic Rats. Nat. Environ. Pollut. Technol. 2012, 11, 5–11. [Google Scholar]

- Labib, R.M.; Ayoub, I.M.; Michel, H.E.; Mehanny, M.; Kamil, V.; Hany, M.; Magdy, M.; Moataz, A.; Maged, B.; Mohamed, A. Appraisal on the wound healing potential of Melaleuca alternifolia and Rosmarinus officinalis L. essential oil-loaded chitosan topical preparations. PLOS ONE 2019, 14, e0219561. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, M.; Li, J.; Rangarajan, M.; Shao, Y.; LaVoie, E.J.; Huang, T.-C.; Ho, C.-T. Antioxidative Phenolic Compounds from Sage (Salvia officinalis). J. Agric. Food Chem. 1998, 46, 4869–4873. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Venskutonis, P.R. Effect of drying on the volatile constituents of thyme (Thymus vulgaris L.) and sage (Salvia officinalis L.). Food Chem. 1997, 59, 219–227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kamatou, G.P.P.; Makunga, N.P.; Ramogola, W.P.; Viljoen, A.M. South African Salvia species: A review of biological activities and phytochemistry. J. Ethnopharmacol. 2008, 119, 664–672. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Topçu, G. Bioactive Triterpenoids from Salvia Species. J. Nat. Prod. 2006, 69, 482–487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Raal, A.; Orav, A.; Arak, E. Composition of the Essential Oil of Salvia officinalis L. from Various European Countries. Nat. Prod. Res. 2007, 21, 406–411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karimzadeh, S.; Farahpour, M.R. Topical Application of Salvia officinalis Hydro ethanolic Leaf Extract Improves Wound Healing Process. Indian J. Exp. Biol. 2017, 55, 98–106. [Google Scholar]

- Zubair, M.; Widén, C.; Renvert, S.; Rumpunen, K. Water and ethanol extracts of Plantago major leaves show anti-inflammatory activity on oral epithelial cells. J. Tradit. Complement. Med. 2018, 9, 169–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sen, S.K.; Behara, L.M. Ethnomedicinal plants used against skin diseases in Bargat district of Orissa. Ethnobotan. 2003, 15, 90–96. [Google Scholar]

- Patil, K.S.; Mandewgade, S.D. Wound healing activity of leaves of Lawsonia alba. J. Nat. Remed. 2003, 3, 129–133. [Google Scholar]

- Kumar, D.; Singla, R.K.; Sharma, R.; Sharma, P.; Kumar, L.; Kaur, N.; Dhawan, R.K.; Sharma, S.; Dua, K. Phytochemistry and Polypharmacological Potential of Colebrookea oppositifolia Smith. Curr. Top. Med. Chem. 2023, 23, 334–348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sarma, S.K.; Bhattacharya, B.K.; Devi, B. Traditional use of herbal medicine by Modahi tribe of Nalabari district of Assam. Ethnobotan. 2002, 14, 103–111. [Google Scholar]

- Thomas, J.; Britto, A. Ethnobotanical study in Wyanad District of Kerala. J. Econom. Taxonom. Bot. 2003, 27, 915–924. [Google Scholar]

- Nautiyal, S.; Maikhuri, R.K.; Rao, K.S.; Saxena, K.G. Medicinal Plant Resources in Nanda Devi Biosphere Reserve in the Central Himalayas. J. Herbs, Spices Med. Plants 2001, 8, 47–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Udupa, S.L.; Udupa, A.L.; Kulkarni, D.R. Studies on anti-inflammatory and wound healing properties of Moringa oleifera and Aegle marmelos. Fitoterapia 1994, 65, 119–123. [Google Scholar]

- Ghanadian, M.; Soltani, R.; Homayouni, A.; Khorvash, F.; Jouabadi, S.M.; Abdollahzadeh, M. The Effect of Plantago major Hydroalcoholic Extract on the Healing of Diabetic Foot and Pressure Ulcers: A Randomized Open-Label Controlled Clinical Trial. Int. J. Low. Extremity Wounds 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).