Submitted:

28 February 2023

Posted:

28 February 2023

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1.Introduction

2. Air Data Evaluation

2.1 Background

2.2. Purpose

2.2.1. Data Download and Cleaning

- Data for 2009-2022 were obtained from EPA’s outdoor air quality data download page. [4]

- Data from the sites analyzed in Nowell et al. (2022) was selected.

- Data was categorized into “Harvest” (October through March, inclusive) and “Non-Harvest” (April through September, inclusive).

- In cases where the POC code [5] was greater than 1, data points for a given day were averaged.

- For days in which there was data with both AQS Parameter [6] “PM2.5 – Local Conditions” and AQS Parameter “Acceptable PM2.5 AQI & Speciation Mass,” the data with AQS Parameter “PM2.5 – Local Conditions” was selected.

2.2.2. Data Analysis

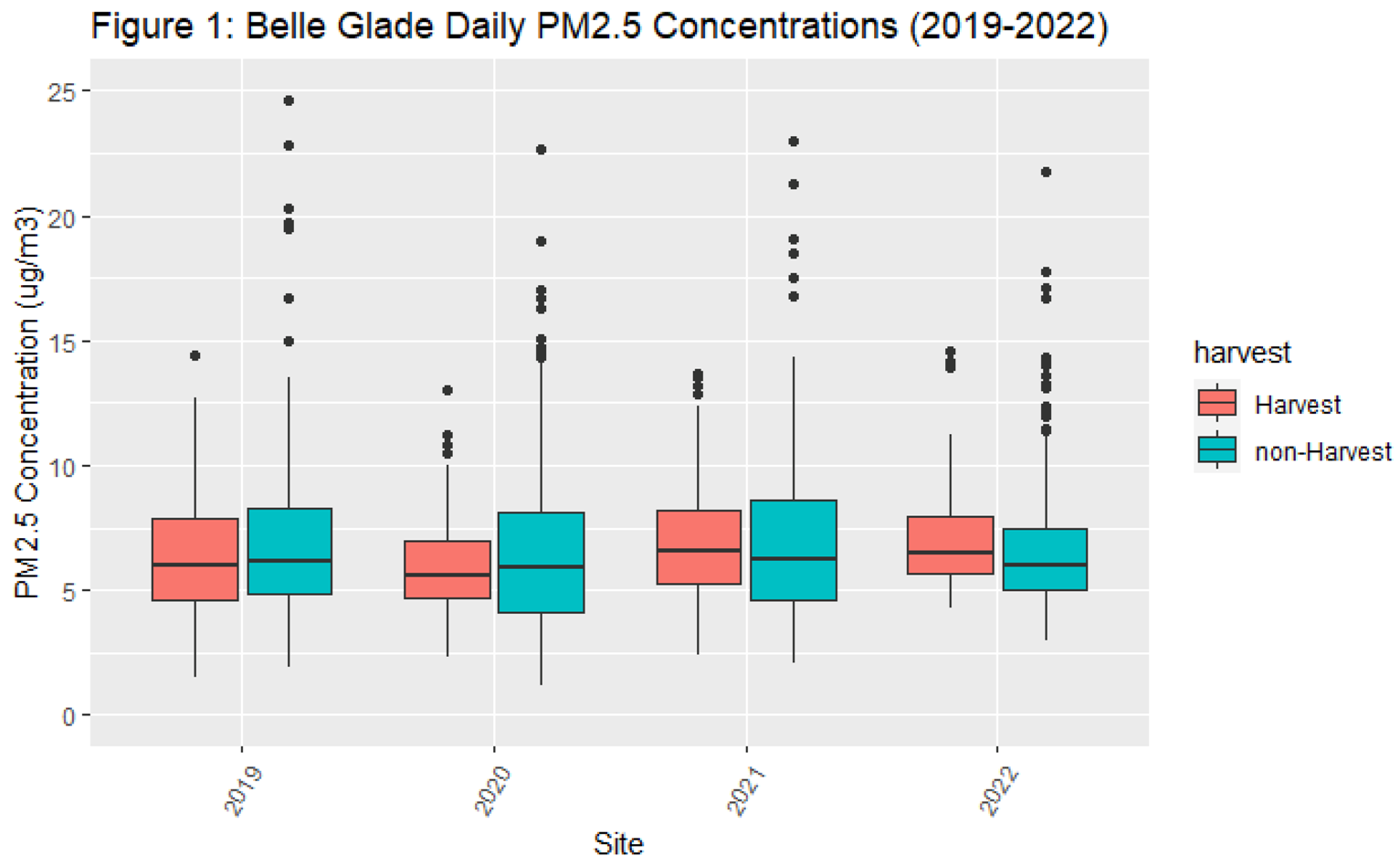

- While the authors’ publication was submitted in 2022, the dataset they relied upon only spanned from 2009 to 2018. According to the authors, their analysis did not extend beyond 2018 because the satellite-derived PM2.5 data was not available (Holmes and Nowell, 2023). Figure 1 presents the data the authors excluded from 2019-2022 that shows some years’ PM2.5 concentrations are lower during harvest compared to non-harvest season, contradicting their conclusion.

- The authors’ use of an unpaired t-test was inappropriate to compare harvest versus non-harvest PM2.5 concentrations since the data used in the t-test are not independent—a requirement for conducting a t-test. At a minimum, such an evaluation requires use of a regression that accounts for yearly fixed effects and clustered standard errors. When using the full dataset from 2009-2022 and clustering standard errors at the month level, there was a statistically insignificant difference at Belle Glade (95% CI: -0.99, 0.25; p = 0.24). Further, adding a fixed effect for the year variable did not substantially change the results (95% CI: -0.99, 0.25; p = 0.25).

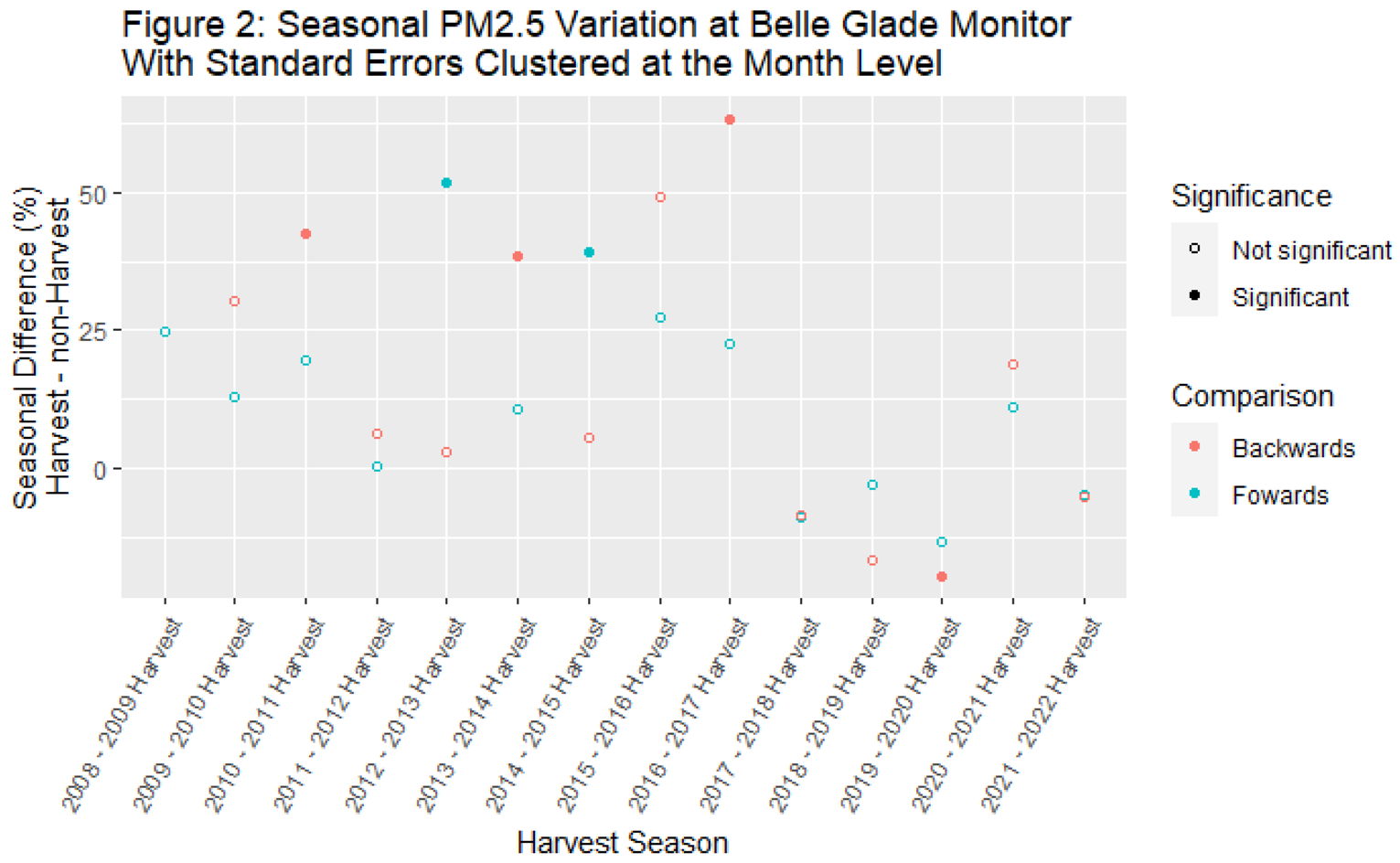

- We further evaluated the data by evaluating concentrations in neighboring seasons on a year-by-year basis. We compared the mean concentration in each harvest season with the mean concentration in the previous non-harvest season (“backwards” analysis) and the following non-harvest season (“forwards” analysis). We conducted this analysis clustering standard errors at the month level. We log-transformed the concentration data for these analyses. Regression coefficients were transformed to be interpreted as percent increases and are shown in Figure 2.

- When clustering standard errors, no harvest season had PM2.5 concentrations that were significantly greater than both the preceding non-harvest season and the following non-harvest season. For example, during the 2012-2013 harvest season, mean PM2.5 concentration was greater than the 2013 non-harvest season. But the 2012-2013 harvest season mean PM2.5 concentration was no different from the 2012 non-harvest season mean PM2.5 concentration. Since the 2017-2018 harvest season, mean concentrations during the harvest season have more often than not been lower than mean concentrations during the preceding and following harvest seasons.

2.3. Discussion:

3. Air Modeling Critique

3.1. Nowell et al. (2022) Background

3.2. Fire Data

- The authors cite Nowell et al. (2018) [7] in a discussion of uncertainty of fire area inputs and indicate that open burn authorization (OBA) data and actual observations differ by <10% overall and by up to 20-40% for individual fires. Nowell et al. (2018) was not an analysis of sugarcane fires; therefore, its relevance to the matter at hand is questionable, and at a minimum increases the uncertainty associated with extrapolation of the data from that study. However, the authors do not quantitatively incorporate any uncertainty in fire area into its analysis: the OBA fire area data is utilized at face value.

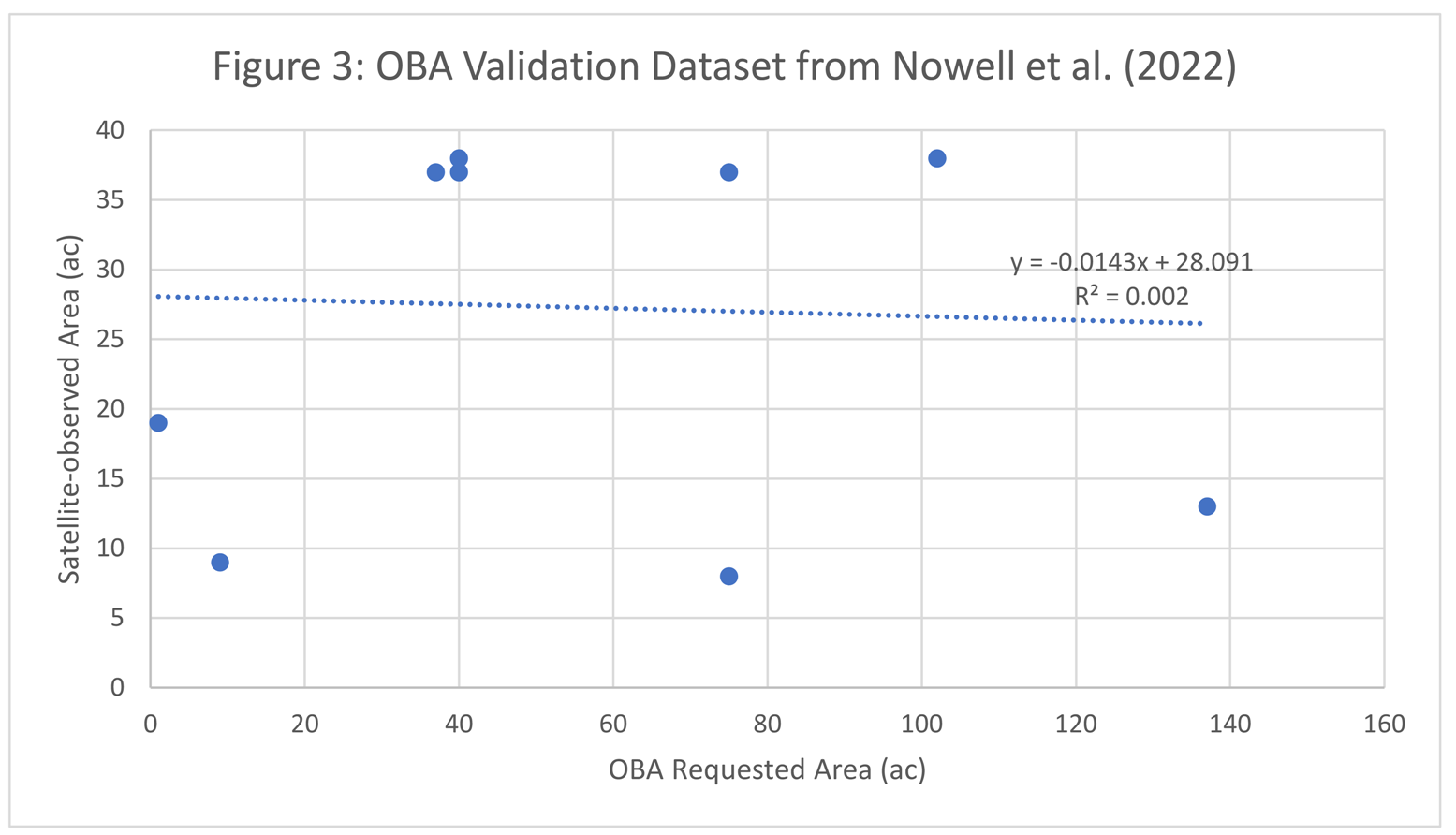

- The authors compare a random sample of 10 sugarcane OBAs with satellite imagery. It is unclear why the authors relied on satellite imagery for this check, given that, “satellites detect only 25% of open biomass fire area” (Nowell et al., 2018). Nevertheless, the authors imply that there is adequate agreement between the OBA data and the satellite data by stating that they, “found a median area discrepancy of just [emphasis added] 2.5 acres (ac) or 6%.” Roux has confirmed this median calculation. However, the average discrepancy was 28 acres or 77%. Roux also found no statistical relationship between the OBA data and the satellite data (as seen in Figure 3).

3.3. Plume Rise Models

3.4. Sugarcane Emission Factors

3.5. Sugarcane Loading Factors

3.6. Secondary particle formation factors

References

- Shapero, A.; Keck, S.; Goswami, E.; Love, A.H. Comment on “Impacts of Sugarcane Fires on Air Quality and Public Health in South Florida”. Environ. Health Perspect. 2022, 131, 028001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nowell, H.K.; et al. Impacts of sugarcane fires on air quality and public health in south Florida. Environ. Health Perspect. 2022, 130, 087004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Holmes, C.D.; Nowell, H.K. Response to “Comment on ‘Impacts of Sugarcane Fires on Air Quality and Public Health in South Florida’”. Environ. Health Perspect. 2023, 131, 028002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- EPA. AirNow.gov - Home of the U.S. Air Quality Index. Year 2009 through September 2022. Available online: https://www.epa.gov/outdoor-air-quality-data/download-daily-data.

- EPA. What does the POC number refer to? Available online: https://www.epa.gov/outdoor-air-quality-data/what-does-poc-number-refer#:~:text=POC%20is%20the%20Parameter%20Occurrence%20Code%20and%20is,and%20monitor%20type%20are%20independent%20of%20each%20other.

- EPA. AQS Memos–Technical Note on Reporting PM2.5 Continuous Monitoring and Speciation Data to the Air Quality System (AQS). Available online: https://www.epa.gov/aqs/aqs-memos-technical-note-reporting-pm25-continuous-monitoring-and-speciation-data-air-quality.

- Nowell, H.K.; Holmes, C.D.; Robertson, K.; Teske, C.; Hiers, J.K. A new picture of fire extent, variability, and drought interaction in prescribed fire landscapes: insights from Florida government records. Geophys. Res. Lett. 2018, 45, 7874–7884. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Draxler, R.R.; Hess, G.D. An overview of the HYSPLIT_4 modelling system for trajectories, dispersion and deposition. Aust. Meteorol. Mag. 1998, 47, 295–308. [Google Scholar]

- Stein, A.F.; et al. Verification of the NOAA Smoke Forecasting System: Model Sensitivity to the Injection Height. Weather Forecast. 2009, 24, 379–394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stein, A.F.; et al. Verification of the NOAA Smoke Forecasting System: Model Sensitivity to the Injection Height. Weather Forecast. 2009, 24, 379–394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Achtemeier, G.L.; Goodrick, S.A.; Liu, Y.; Garcia-Menendez, F.; Hu, Y.; Odman, M.T. Modeling smoke plume-rise and dispersion from Southern United States prescribed burns with Daysmoke. Atmosphere 2011, 2, 358–388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Achtemeier, G.L.; Goodrick, S.L.; Jackson, W.A. Important parameters for smoke plume rise simulation with Daysmoke. Atmos. Pollut. Res. 2010, 1, 250–259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Val Martin, M.; Logan, J.A.; Kahn, R.A.; Leung, F.-Y.Y.; Nelson, D.L.; Diner, D.J. Smoke injection heights from fires in North America: analysis of 5 years of satellite observations. Atmos. Chem. Phys. 2010, 10, 1491–1510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCarty, J.L. Remote sensing-based estimates of annual and seasonal emissions from crop residue burning in the contiguous United States. J. Air Waste Manag. Assoc. 2011, 61, 22–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pouliot, G.; Rao, V.; McCarty, J.L.; Soja, A.J. Development of the crop residue and rangeland burning in the 2014 national emissions inventory using information from multiple sources. J. Air Waste Manag. Assoc. 2017, 67, 613–622. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fang, Z.; Deng, W.; Zhang, Y.; Ding, X.; Tang, M.; Liu, T.; et al. Open burning of rice, corn and wheat straws: primary emissions, photochemical aging, and secondary organic aerosol formation. Atmos. Chem. Phys. 2017, 17, 14821–14839. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.; Zhang, Y.; Huey, L.G.; Yokelson, R.J.; Wang, Y.; Jimenez, J.L.; et al. Agricultural fires in the southeastern U.S. during SEAC4RS. J. Geophys. Res. Atmos. 2016, 121, 7383–7414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vakkari, V.; Kerminen, V.; Beukes, J.P.; Tiitta, P.; Zyl, P.G.; Josipovic, M.; et al. Rapid changes in biomass burning aerosols by atmospheric oxidation. Geophys. Res. Lett. 2014, 41, 2644–2651. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahern, A.T.; Robinson, E.S.; Tkacik, D.S.; Saleh, R.; Hatch, L.E.; Barsanti, K.C.; et al. Production of secondary organic aerosol during aging of biomass burning smoke from fresh fuels and its relationship to VOC precursors. J. Geophys. Res. Atmos. 2019, 124, 3583–3606. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cubison, M.J.; Ortega, A.M.; Hayes, P.L.; Farmer, D.K.; Day, D.; Lechner, M.J.; et al. Effects of aging on organic aerosol from open biomass burning smoke in aircraft and laboratory studies. Atmos. Chem. Phys. 2011, 11, 12049–12064. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yokelson, R.J.; Crounse, J.D.; DeCarlo, P.F.; Karl, T.; Urbanski, S.; Atlas, E.; et al. Emissions from biomass burning in the Yucatan. Atmos. Chem. Phys. 2009, 9, 5785–5812. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vakkari, V.; Beukes, J.P.; Dal Maso, M.; Aurela, M.; Josipovic, M.; van Zyl, P.G. Major secondary aerosol formation in Southern African open biomass burning plumes. Nature Geosci. 2019, 11, 580–583. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).