Submitted:

06 February 2023

Posted:

13 February 2023

Read the latest preprint version here

Abstract

Keywords:

Introduction

Methods

Results

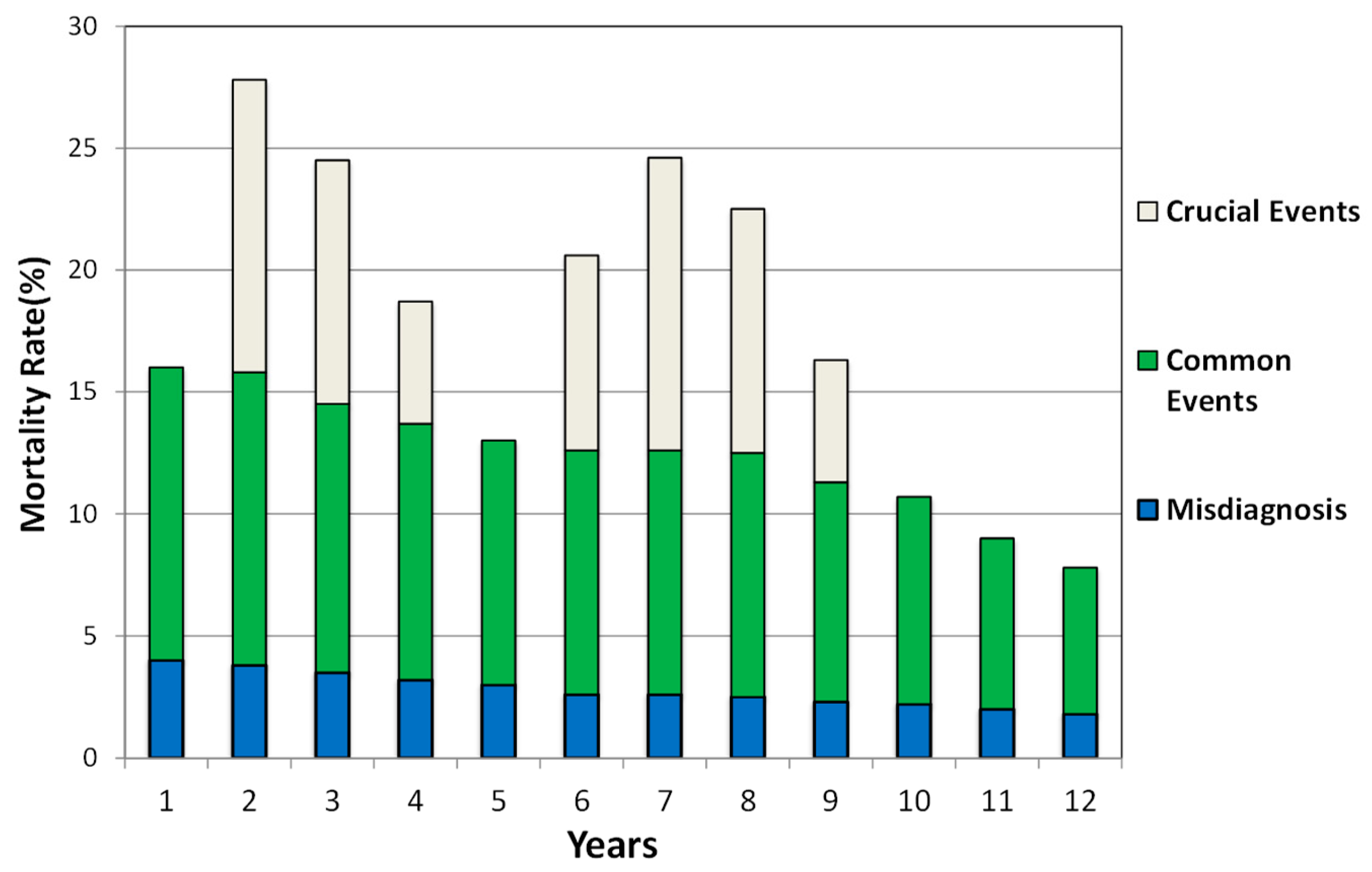

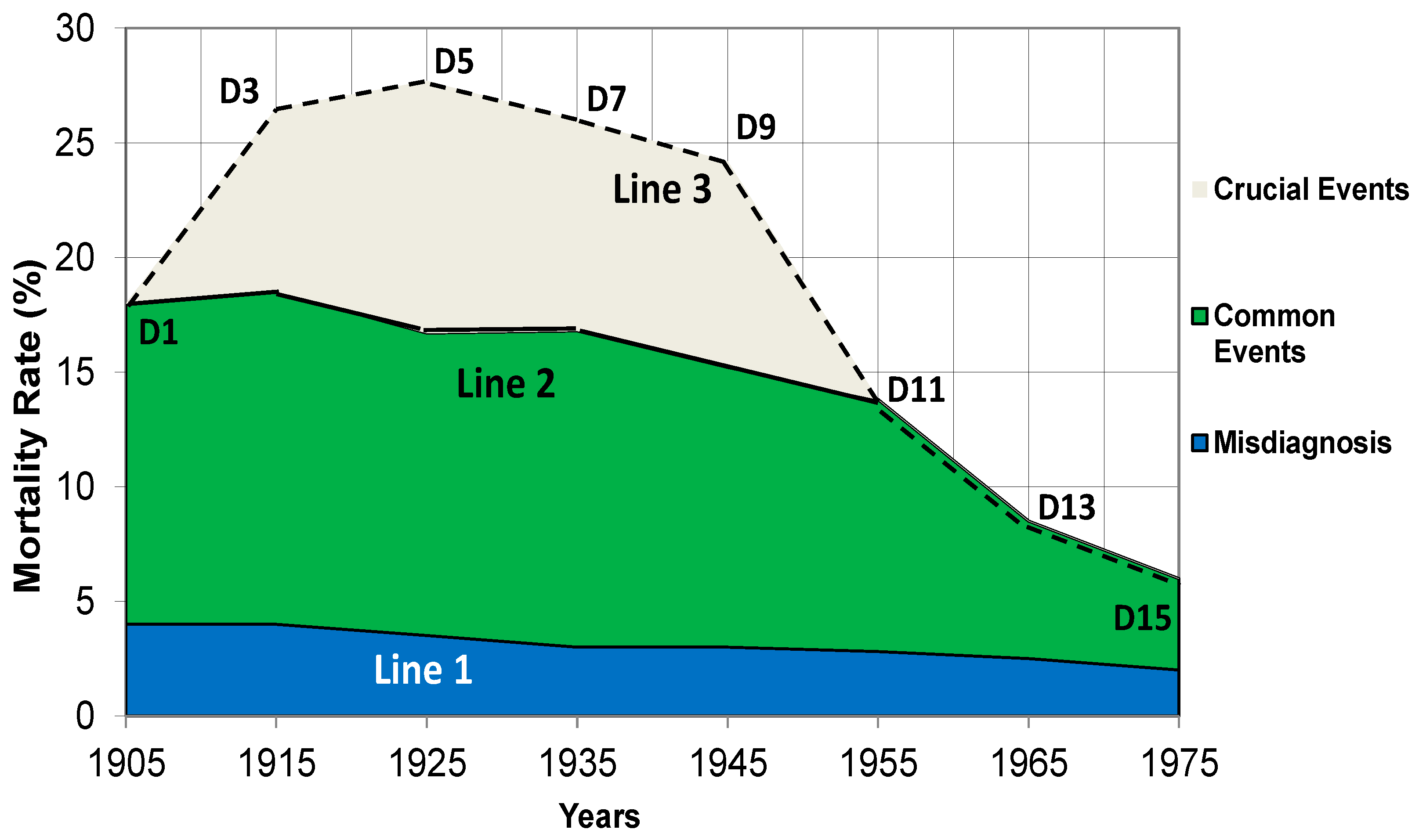

1. Classification of the stressors causing peptic ulcers

| Category | Stressors | Features |

|---|---|---|

| Clinical Misdiagnosis | 1. Commonly seen in the 20th century. | 1. Occurs at a certain frequency. 2. Causes a relatively consistent mortality. 3. The mortality caused by misdiagnosis fluctuates slightly. |

| Common Events | 1. Common social events: unemployment, divorce, poverty, family and neighbourhood conflicts, etc. 2. Struggling with personality disorders: immaturity, negative perception, hypochondriasis, dependency, impulsivity, etc. 3. Environment factors: seasonal alterations, working environment, urbanisation etc. |

1. Occur at a certain frequency. 2. Cause a relatively consistent mortality. 3. The mortality caused by common events fluctuates slightly. |

| Crucial Events | 1. Wars: worldwide or local wars, massacres, religious conflicts, etc. 2. Crucial economic or social crises, political movements etc. 3. Natural disasters: earthquake, tsunamis, typhoon, flood, or landslides, etc. |

1. Happen sporadically and lasts for a limited period of time. 2. Leads to an uneven mortality rate. 3. The mortality caused by crucial events fluctuates markedly. |

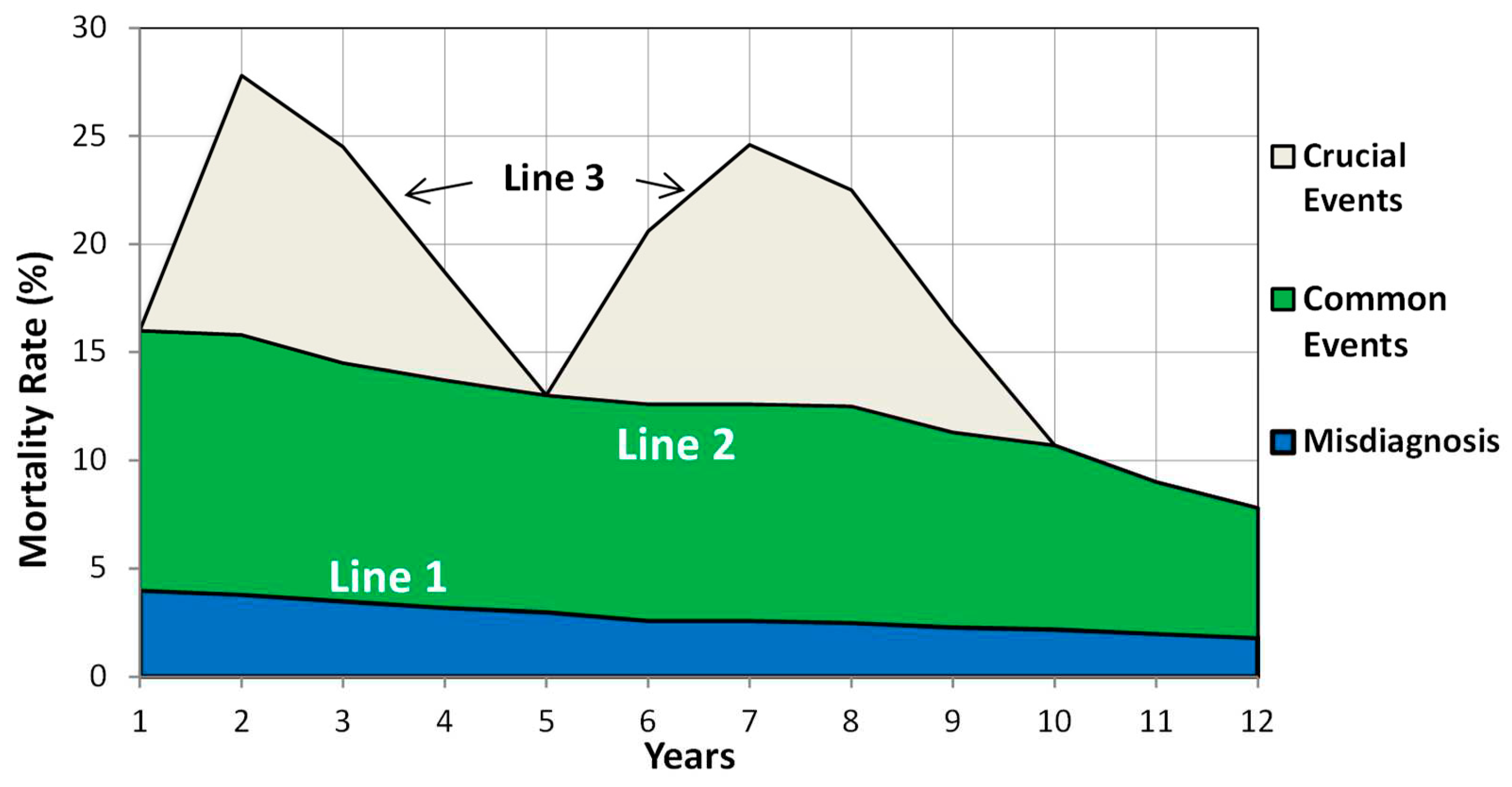

2. The vertical superposition of the mortality rates of gastric ulcers

3. The horizontal superposition to determine the trends of mortality rates over time

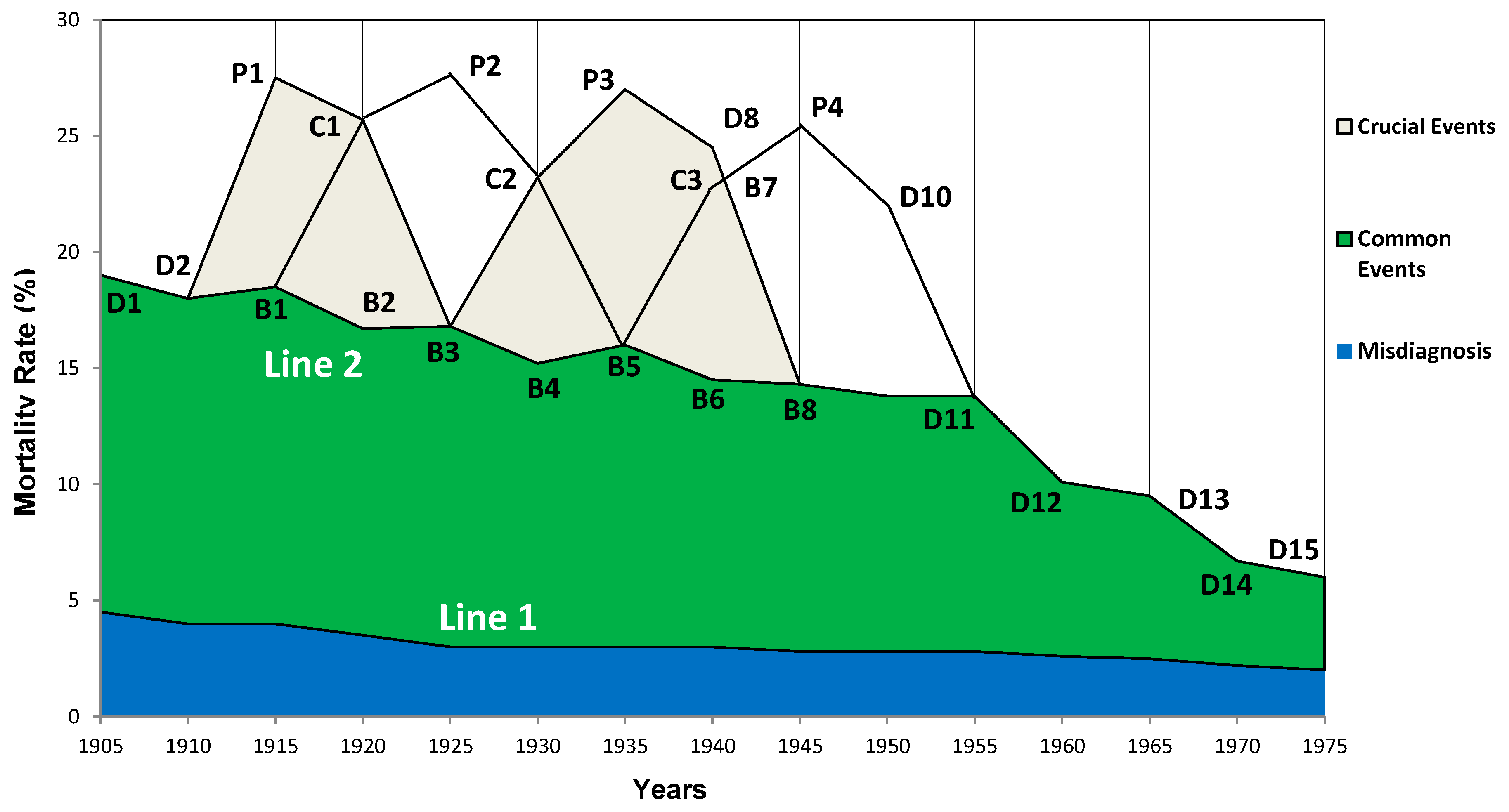

4. Overlapping of fluctuation curves due to a succession of crucial social events.

5. The mortality rates cause by a succession of crucial social events

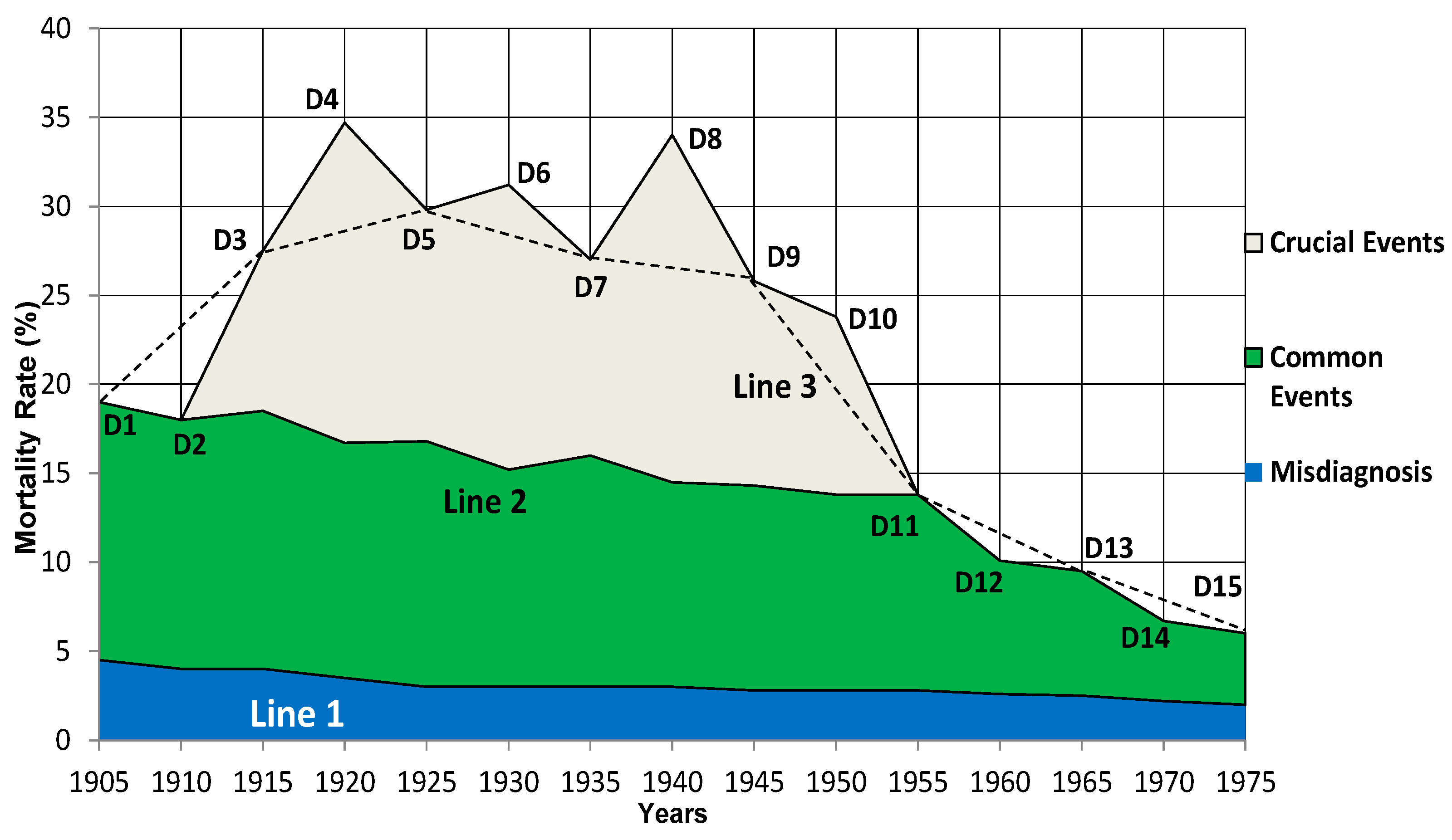

6. Reproduction of the mortality fluctuation curves of the birth-cohort phenomena

7. Understanding the birth-cohort phenomenon of gastric ulcers

8. The delayed occurrence of duodenal ulcers

Discussion

Conclusion

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

Conflict of Interest

References

- Susser M, Stein Z. Civilization and Peptic Ulcer. Lancet. 1962;279(7221):116-119. [CrossRef]

- Susser M, Stein Z. Civilization and peptic ulcer*. Int J Epidemiol. 2002;31(1):13-17. [CrossRef]

- Westbrook JI, Rushworth RL. The epidemiology of peptic ulcer mortality 1953-1989: A birth cohort analysis. Int J Epidemiol. 1993;22(6):1085-1092. [CrossRef]

- Sonnenberg A, Müller H, Pace F. Birth-cohort analysis of peptic ulcer mortality in Europe. J Chronic Dis. 1985;38(4):309-317. [CrossRef]

- Thors H, Svanes C, Thjodleifsson B. Trends in peptic ulcer morbidity and mortality in Iceland. J Clin Epidemiol. 2002;55(7):681-686. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/12160916.

- Sonnenberg A. Occurrence of a Cohort Phenomenon in Peptic Ulcer Mortality From Switzerland. Gastroenterology. 1984;86(3):398-401. [CrossRef]

- Dong SXM, Chang CCY, Rowe KJ. A collection of the etiological theories, characteristics, and observations/phenomena of peptic ulcers in existing data. Data Br. 2018;19:1058-1067. [CrossRef]

- Quan C, Talley NJ. Management of peptic ulcer disease not related to Helicobacter pylori or NSAIDs. Am J Gastroenterol. 2002;97(12):2950-2961. [CrossRef]

- Ford AC, Talley NJ. Head to Head: Does Helicobacter pylori really cause duodenal ulcers? Yes. BMJ. 2009;339(aug14 1):b2784. [CrossRef]

- Hobsley M, Tovey FI, Bardhan KD, Holton J. Head to Head: Does Helicobacter pylori really cause duodenal ulcers? No. BMJ. 2009;339(aug14 1):b2788. [CrossRef]

- Record CO, Rubin PC. Controversies in Management: Helicobacter pylori is not the causative agent. BMJ. 1994;309(6968):1571-1572. [CrossRef]

- Kate V, Ananthakrishnan N, Tovey FI. Is Helicobacter pylori Infection the Primary Cause of Duodenal Ulceration or a Secondary Factor? A Review of the Evidence. Gastroenterol Res Pract. 2013;2013:1-8. [CrossRef]

- Tovey FI, Hobsley M. Review: is Helicobacter pylori the primary cause of duodenal ulceration? J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 1999;14(11):1053-1056. [CrossRef]

- Marshall B. Commentary: Helicobacter as the ‘environmental factor’ in Susser and Stein’s cohort theory of peptic ulcer disease. Int J Epidemiol. 2002;31(1):21-22. [CrossRef]

- Sonnenberg A. Causes underlying the birth-cohort phenomenon of peptic ulcer: analysis of mortality data 1911–2000, England and Wales. Int J Epidemiol. 2006;35(4):1090-1097. [CrossRef]

- Jones MP. The role of psychosocial factors in peptic ulcer disease: Beyond Helicobacter pylori and NSAIDs. J Psychosom Res. 2006;60(4):407-412. [CrossRef]

- Freston JW. Role of proton pump inhibitors in non-H. pylori-related ulcers. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2001;15(s2):2-5. [CrossRef]

- Kato S, Nishino Y, Ozawa K, et al. The prevalence of Helicobacter pylori in Japanese children with gastritis or peptic ulcer disease. J Gastroenterol. 2004;39(8):734-738. [CrossRef]

- Elitsur Y, Lawrence Z. Non-Helicobacter pylori related duodenal ulcer disease in children. Helicobacter. 2001;6(3):239-243. [CrossRef]

- Kanotra R, Ahmed M, Patel N, et al. Seasonal Variations and Trends in Hospitalization for Peptic Ulcer Disease in the United States: A 12-Year Analysis of the Nationwide Inpatient Sample. Cureus. 2016;8(10):1-14. [CrossRef]

- Sonnenberg A, Wasserman IH, Jacobsen SJ. Monthly variation of hospital admission and mortality of peptic ulcer disease: A reappraisal of ulcer periodicity. Gastroenterology. 1992;103(4):1192-1198. [CrossRef]

- Rauws EAJJ, Tytgat GNJJ. Helicobacter pylori in duodenal and gastric ulcer disease. Baillieres Clin Gastroenterol. 1995;9(3):529-547. [CrossRef]

- Holcombe C. Helicobacter pylori: the African enigma. Gut. 1992;33(4):429-431. [CrossRef]

- Smith GD, Susser E. Zena Stein, Mervyn Susser and epidemiology: observation, causation and action. Int J Epidemiol. 2002;31(1):34-37. [CrossRef]

- Susser M. Peptic Ulcer: Rise and Fall. Christie DA, Tansey EM (eds). Wellcome Witnesses to Twentieth Century Medicine. Vol.14, 2002. London: The Wellcome Trust Centre for the History of Medicine, 2002, £10.00 ISBN: 0-85484-084-2. Int J Epidemiol. 2003;32(4):674-675. [CrossRef]

- Dong SXM, Chang CCY. Philosophical Principles of Life Science. Taipei: Wunan Culture Enterprise; 2012.

- Dong SXM. A Novel Psychopathological Model Explains the Pathogenesis of Gastric Ulcer. J Ment Heal Clin Psychol. 2022;6(3):13-24. [CrossRef]

- Dong SXM. The hyperplasia and hypertrophy of gastrin and parietal cells induced by chronic stress explain the pathogenesis of duodenal ulcer. J Ment Heal Clin Psychol. 2022;6(3):1-12. [CrossRef]

- Dong SXM. Painting a complete picture of peptic ulcers. Jounral Ment Heal Clin Psychol. 2022;6(3):32-43. [CrossRef]

- Damon A, Polednak AP. Constitution, genetics, and body form in peptic ulcer: A review. J Chronic Dis. 1967;20(10):787-802. [CrossRef]

- Magon P. Abdominal epilepsy misdiagnosed as peptic ulcer pain. Indian J Pediatr. 2010;77(8):916-916. [CrossRef]

- Kitchin DR, Lubner MG, Menias CO, Santillan CS, Pickhardt PJ. MDCT diagnosis of gastroduodenal ulcers: key imaging features with endoscopic correlation. Abdom Imaging. 2015;40(2):360-384. [CrossRef]

- Salleh MR. Life event, stress and illness. Malays J Med Sci. 2008;15(4):9-18. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/22589633.

- Feldman M, Walker P, Green JL, Weingarden K. Life events stress and psychosocial factors in men with peptic ulcer disease: a multidimensional case-controlled study. Gastroenterology. 1986;91(6):1370-1379. [CrossRef]

- Compas BE. Stress and life events during childhood and adolescence. Clin Psychol Rev. 1987;7(3):275-302. [CrossRef]

- Mcintosh JH, Nasiry RW, Frydman M, Waller SL, Piper DW. The Personality Pattern of Patients with Chronic Peptic Ulcer. Scand J Gastroenterol. 1983;18(7):945-950. [CrossRef]

- Schuster J-P, Limosin F, Levenstein S, Le Strat Y. Association Between Peptic Ulcer and Personality Disorders in a Nationally Representative US Sample. Psychosom Med. 2010;72(9):941-946. [CrossRef]

- Ellard K, Beaurepaire J, Jones M, Piper D, Tennant C. Acute and chronic stress in duodenal ulcer disease. Gastroenterology. 1990;99(6):1628-1632. [CrossRef]

- Kennedy DP, Adolphs R. Stress and the city. Nature. 2011;474(7352):452-453. [CrossRef]

- Kurata JH, Haile BM. Epidemiology of peptic ulcer disease. Clin Gastroenterol. 1984;13(2):289-307. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/6378441.

- Riley ID. Perforated peptic ulcer in war-time. Lancet. 1942;243:485. [CrossRef]

- Dragstedt LR, Ragins H, Dragstedt LR, Evans SO. Stress and Duodenal Ulcer. Ann Surg. 1956;144(3):450-463. [CrossRef]

- Sonnenberg A, Müller H, Pace F. Birth-cohort analysis of peptic ulcer mortality in Europe. J Chronic Dis. 1985;38(4):309-317. [CrossRef]

- Hikichi T, Sato M, Watanabe K, et al. Peptic Ulcers in Fukushima Prefecture Related to the Great East Japan Earthquake, Tsunami and Nuclear Accident. Intern Med. 2018;57(7):915-921. [CrossRef]

- Aoyama N, Kinoshita Y, Fujimoto S, et al. Peptic Ulcers After the Hanshin-Awaji Earthquake: Increased Incidence of Bleeding Gastric Ulcers. Am J Gastroenterol. 1998;93(3):311-316. [CrossRef]

- Glavin GB, Murison R, Overmier JB, et al. The neurobiology of stress ulcers. Brain Res Rev. 1991;16(3):301-343. [CrossRef]

- Ganguli PC, Pearse AGE, Polak J, Elder JB, Hegarty M. Antral-Gastrin-Cell hyperplasia in peptic ulcer disease. Lancet. 1974;303(7858):583-586. [CrossRef]

- McGuigan JE, Harty RF, Maico DG. The role of gastrin in duodenal ulcer. Trans Am Clin Climatol Assoc. 1981;92:199-207. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/6116307.

- Starcke K, Wiesen C, Trotzke P, Brand M. Effects of Acute Laboratory Stress on Executive Functions. Front Psychol. 2016;7(MAR):1-8. [CrossRef]

- Brouwer A-M, Hogervorst MA. A new paradigm to induce mental stress: the Sing-a-Song Stress Test (SSST). Front Neurosci. 2014;8(8 JUL):1-8. [CrossRef]

- Linda R, Ransohoff DF. Is helicobacter pylori a cause of duodenal ulcer? A methodologic critique of current evidence. Am J Med. 1991;91(6):566-572. [CrossRef]

- Walsh JH, Peterson WL. The Treatment of Helicobacter pylori Infection in the Management of Peptic Ulcer Disease. Wood AJJ, ed. N Engl J Med. 1995;333(15):984-991. [CrossRef]

- Arkkila P. Eradication of Helicobacter pylori improves the healing rate and reduces the relapse rate of nonbleeding ulcers in patients with bleeding peptic ulcer. Am J Gastroenterol. 2003;98(10):2149-2156. [CrossRef]

- Marshall BJ, Goodwin CS, Warren JR, et al. Prospective double-blind trial of duodenal ulcer relapse after eradication of Campylobacter pylori. Lancet (London, England). 1988;2(8626-8627):1437-1442. [CrossRef]

- Sivri B. Review Article: Trends in peptic ulcer pharmacotherapy. Fundam Clin Pharmacol. 2004;18(1):23-31. [CrossRef]

- Newton I, Shapiro AE. The Principia: Mathematical Principles of Natural Philosophy. Phys Today. 2000. [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).