Introduction

In 1983, Schuster and Sigmund [

36] recognized that the mathematical description of self-organization in seemingly completely different areas is based on the same differential equation, the formulation of which has been discovered several times independently. In population genetics, it describes the change in allele frequencies in the gene pool as Selection Equation [

21]; in Mathematical Ecology, it is represented by the Lotka-Volterra equation, which describes the dynamics of populations or species [

34,

42], in Quasispecies Theory it models the concentration of self-replicating, information-bearing macromolecules in the context of prebiotic evolution [

9], and in sociobiology as the Game Dynamics Equation heritable or tradable conflict behavior [

33]. If it was already astonishing to find it in all these fields of biology, it is certainly even more astounding to find it outside this scientific branch. In the same year 1983, H. Haken surprisingly noted that the equations describing, according to M. Eigen, the autocatalytic propagation of biomolecules coincide in the original version with those dealing with the amplification of light waves or photons in his laser model [

9,

31]. Thus, replicator dynamics or selection theory seem to be of importance in the whole field of natural sciences and the question now arises what conditions have to be fulfilled for it to be applicable. These are the following ones:

A replicator is information (In this context, information is an immaterial “something” that can be stored in physically very different storage media (such as a sheet of paper or a polynucleotide …), that can be transmitted from one medium to another, from one place to another, that can be copied and deleted (i.e. overwritten). Even the ability to be erased is not at all self-evident. A (material) object can be transformed, but not erased) (a message) that can be copied and the copying process is the fundamental phenomenon of replicator dynamics. The content of the message influences the copying frequency (often indirectly, by influencing the features of the information carrier). If the content of the message changes (mutation), this may also change the copying frequency.

If different replicators and thus messages are present, they usually do not blend but remain unchanged (a gene is a replicator, a genotype is a recombinator. In the case of the latter, genes can shuffle "like cards", i.e. they recombine).

From the ability to be copied follows (in principle) exponential propagation (autocatalysis) of the message and its carrier, because not only the original but also the copy can be further copied.

There is resource limitation so that one message must be deleted for another one to be copied. Thus competition follows if there are several different replicators.

If the replicator dynamics is indeed applicable to the emergence of coherence in lasers, these conditions must be met, which then implies that photons are replicator-carriers. However, a first attempt by the author [

40] to develop a model on this basis was flawed (e. g. photons were assumed to interact directly with each other), so a correction is required.

Single events or systems of moderate complexity can be described in a different way than many-particle systems, where often details have to be neglected in favor of a statistical approach. The replicator equation describes the behavior of an ensemble, i.e. a system of very high numbers of individuals (or macromolecules ...), yet, as the above list shows, replicator dynamics is based on a very precise notion of the underlying individual events and features. To apply it to e. g. photons, one has to know their properties and interaction modes. It would be obvious to look for this in the context of quantum theory which is also an ensemble theory, but „without foundation“, i.e. it has no significance concerning single events (“Der am Einzelsysteme sich abspielende Vorgang bleibt freilich bei solcher Betrachtungsweise völlig unaufgeklärt; letzterer ist eben durch die statistische Betrachtungsweise aus der Darstellung völlig eliminiert” (The process that takes place in the individual system, of course, remains completely unexplained by such an approach; the latter is completely eliminated from the representation by the statistical approach)) [

17] and thus it remains in the dark what is going on at the fundamental ("microscopic") level. The accompanying mainstream philosophies assume that the description of the single events is not necessary/ that it is not possible to describe them/ that on the relevant level ("quantum reality") no cause-and-effect processes exist at all. A. Einstein did not agree at all with this last interpretation, which originally goes back to W. Heisenberg and N. Bohr (Copenhagen interpretation). He wanted to create a quantum theory with foundation, and especially in 1905, 1914, 1916, 1917, 1919 and 1924 he made essential contributions to it [

10,

11,

12,

13,

14,

15]. After the discovery of matrix mechanics (W. Heisenberg 1925 [

32]) and wave mechanics (E. Schrödinger 1926 [

35]), he repeatedly tried to prove the Copenhagen interpretation absurd, whereby he discovered entanglement and one of its consequences, the immediate “spooky action at a distance” (“spukhafte Fernwirkung”) together with Rosen and Podolsky in 1935 (ref. [

16]; their intention was to show that quantum mechanics gives an incomplete description of reality). The existence of entanglement was seemingly proven by various experiments, which was honored by the award of the 2022 Nobel Prize in Physics. Another "quantum weirdness" is self-superposition, according to which a quantum can take several paths simultaneously and then interfere with itself. It was propagated in particular by R. Feynman [

18], who inferred its existence from his path integral method for amplitude calculation (rediscovered by him, originally described by G. Wentzel in 1924, who had drawn other conclusions from it; [

1,

43].

Beyond this mainstream, there have always been scientists who insisted on a cause-and-effect worldview. In this context, H. De Raedt and K. Michielsen are very worthy of mention, who, starting in 2005, together with others, have shown in numerous computer simulations that experimental results and observed phenomena can be explained without "quantum weirdness" (e.g., [

2,

3]). This is also shown in other ways [

5,

6,

7,

8]. Of particular relevance to the present publication is a paper in which the criterion of robustness is introduced [

4]. The authors state: "Quantum theory is fundamentally different from classical theories in that there may be uncertainties about each individual event, uncertainties which cannot be eliminated, not even in principle ... Clearly, this is a statement about the theory, not about the observed phenomena themselves." They "...classify theoretical abstractions of scientific experiments", whereas that category, which is specified in the following, belongs neither to classical physics nor to classical physics supplemented by statistics: "There may be uncertainty about each event. The conditions under which the experiment is carried out may be uncertain." Special attention is now given to that subset of this category of theoretical models in which "the frequencies with which events are observed are reproducible and robust against small changes in the conditions." The authors show in their paper that "the rules of logical inference applied to models of ..." the category just described "… lead rather straightforwardly to the basic equations of quantum theory". It should be emphasized once again that this is on the assumption that the laws of Newtonian dynamics hold for the observed events.

In the author's opinion, this publication does not prove that there is no "quantum weirdness", but it does show that this concept is completely unnecessary and if one applies "Ockham's razor" to it, one can assume that it will eventually vanish from the scientific literature just as the aether (the medium in which light waves were supposed to move) did in the years after 1905. For us, this is significant in that we conclude that it makes sense to ask about features and modes of interaction of photons, and not just about their statistical behavior in the ensemble. Preliminarily, a short summary:

We assume that Photons are replicators (or, more precise, they are replicator-carriers). The feature (message) relevant for us is the phase. The phases of different photons do not blend (otherwise the autocatalytic propagation of a phase would not be possible).

Photons are oscillating particles (they are not waves, neither wave and particle or sometimes this, sometimes that).

There is no superposition of a photon with itself.

Photons do not interact directly with each other, but they do with matter.

The author will here develop the view that interference is based on photon pair interaction mediated by matter. The compatibility of this view with Einstein's findings on the interaction of radiation and matter [

12] will be examined first, followed by its compatibility with the photoelectric effect [

10] and the double-slit experiment [

19,

20], and finally its application to the emergence of coherent light in lasers [

26,

27,

28,

29,

30]. As in previous publications by the author, another focus of this paper is on the change in entropy due to selection (Refs. [

38,

39,

40,

41]; on the subject, see also Refs. [

22,

23,

24,

25]).

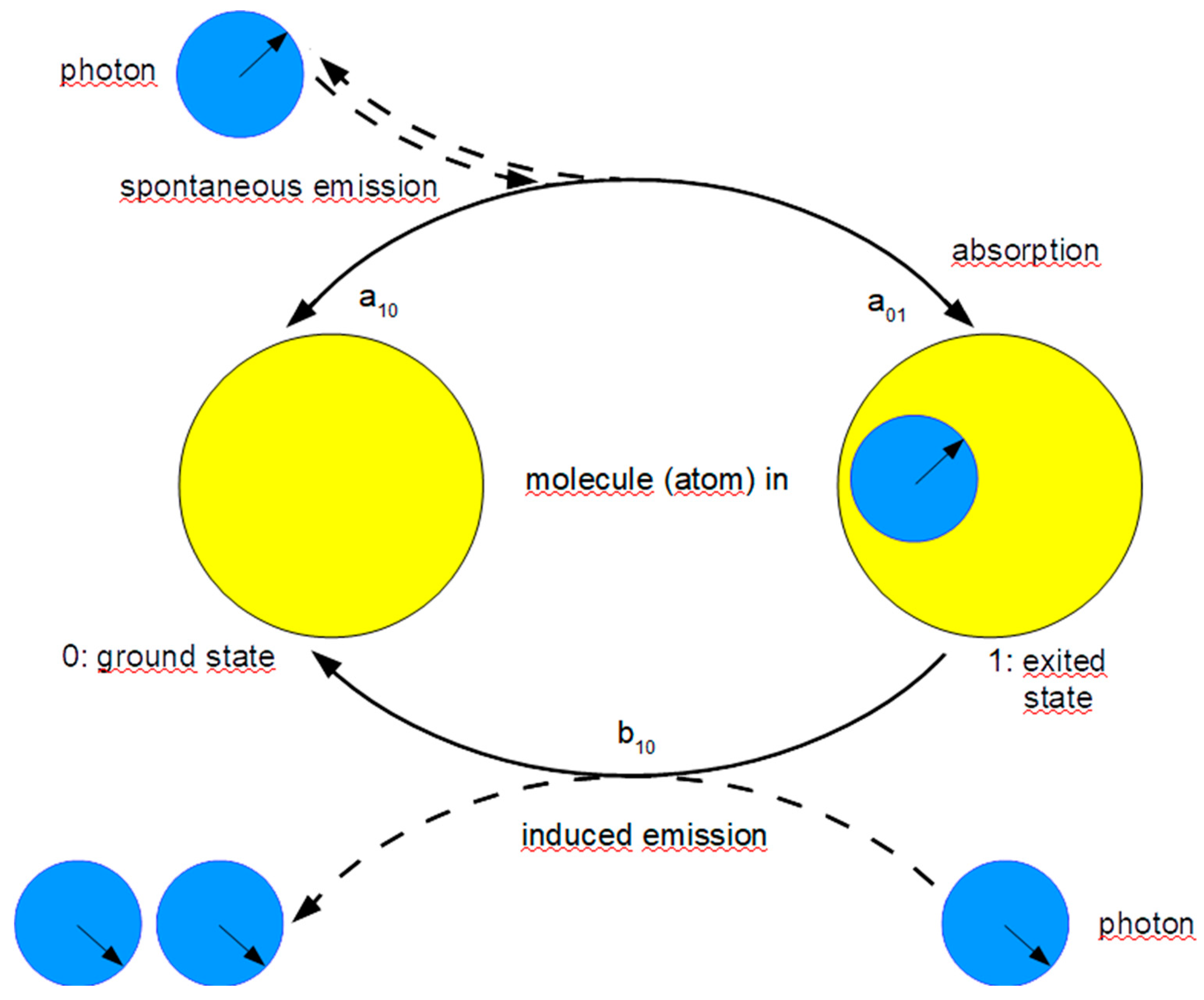

On the Interaction between Electromagnetic Radiation and Matter

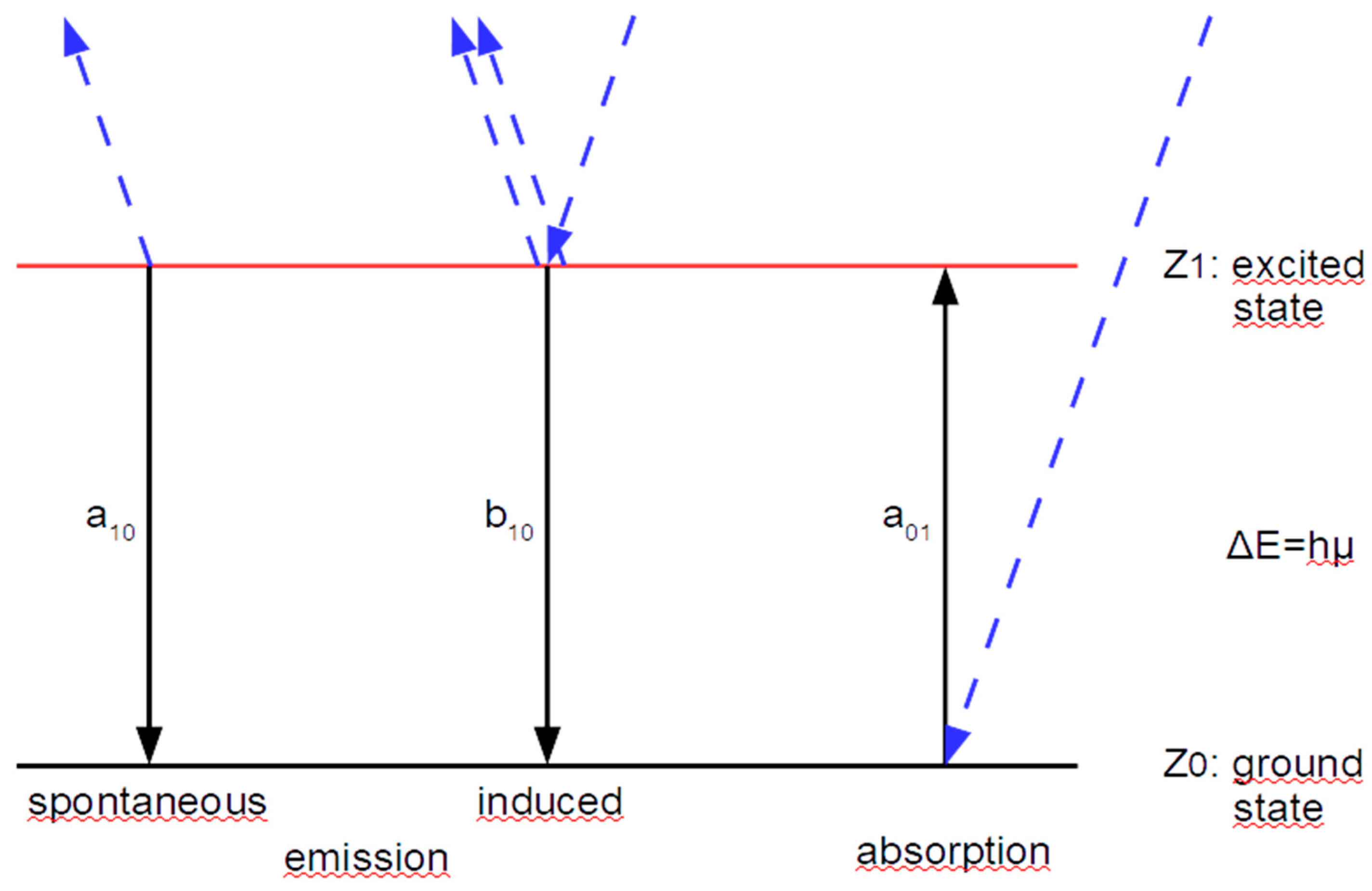

In 1916, A. Einstein developed a theory on the emission and absorption of electromagnetic radiation (subsequently often simplified as "light") by matter based on his photon theory of 1905 [

10,

12,

13]. The starting point was the law of blackbody radiation, established by M. Planck in 1900. Einstein found that, in addition to absorption, there must be two types of emission, namely spontaneous, which finds its analogue in radioactive decay, and induced (stimulated) emission. The latter is induced by photons of the same frequency as the emitted one and occurs when an “exited” molecule is irradiated by such a light quantum (Einstein uses "molecule", while today the term "atom" is usually used in this context; in any case, the actual interaction takes place between photon and shell electron). This transition between two (out of many) energy levels of an atom was presented in an illustrative form by R. Feynman in a lecture in 1961 [

19], apparently motivated by similar presentations on the energy change in catalytic reactions. His representation is the template for the following figure:

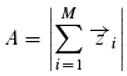

Figure 1.

Energy budget of the interaction between light and matter according to Einstein 1916 and Feynman 1961.

Figure 1.

Energy budget of the interaction between light and matter according to Einstein 1916 and Feynman 1961.

By absorption of a photon (symbolized by blue arrows) the atom moves from the ground state Z0 to the excited state Z1, the emission is a reversal of this event. The corresponding transition probabilities for the time interval Δt are given by a01 for absorption, a10 for spontaneous emission, and b10 for induced (stimulated) emission. The states Z0 and Z1 differ by the amount of energy ΔE=hμ, where h is Plank's quantum of action, a constant, and μ is the frequency of the photon.

To be able to describe the kinetics of these events, we define N0 as the frequency of atoms in the ground state, N1 as the frequency in the excited state. Let Mμ be the number of photons of frequency μ. Then n0=N0/(N0+N1), n1=N1/(N0+N1) and mμ=Mμ/(N0+N1) denote the relative frequencies related to the total number of atoms and molecules, respectively. Therefore, for the event-related relative frequencies x, the following relationship with the transition probabilities a during Δt is obtained (the consequences of a single event are shown in parentheses).

Emission (N

0→N

0+1; N

1→N

1-1; M

→M+1):

and for the emission as a whole:

Absorption (N

0→N

0-1; N

1→N

1+1; M

→M-1):

Einstein, however, used the light intensity Iμ instead of mμ, which is proportional to the photon number for non-coherent radiation, but not identical to it (this is only the case if a10=a01). By considering the equilibrium x0→1=x1→0, using the Boltzmann distribution and Planck's radiation equation, which he assumed to be correct, he found, among other things, that a01=b10, a result which is by no means self-evident and should also find explanation in an event-based model (in the framework of quantum theory, it is generally assumed that the probability for the occurrence of an event is equal to that for its reversal).

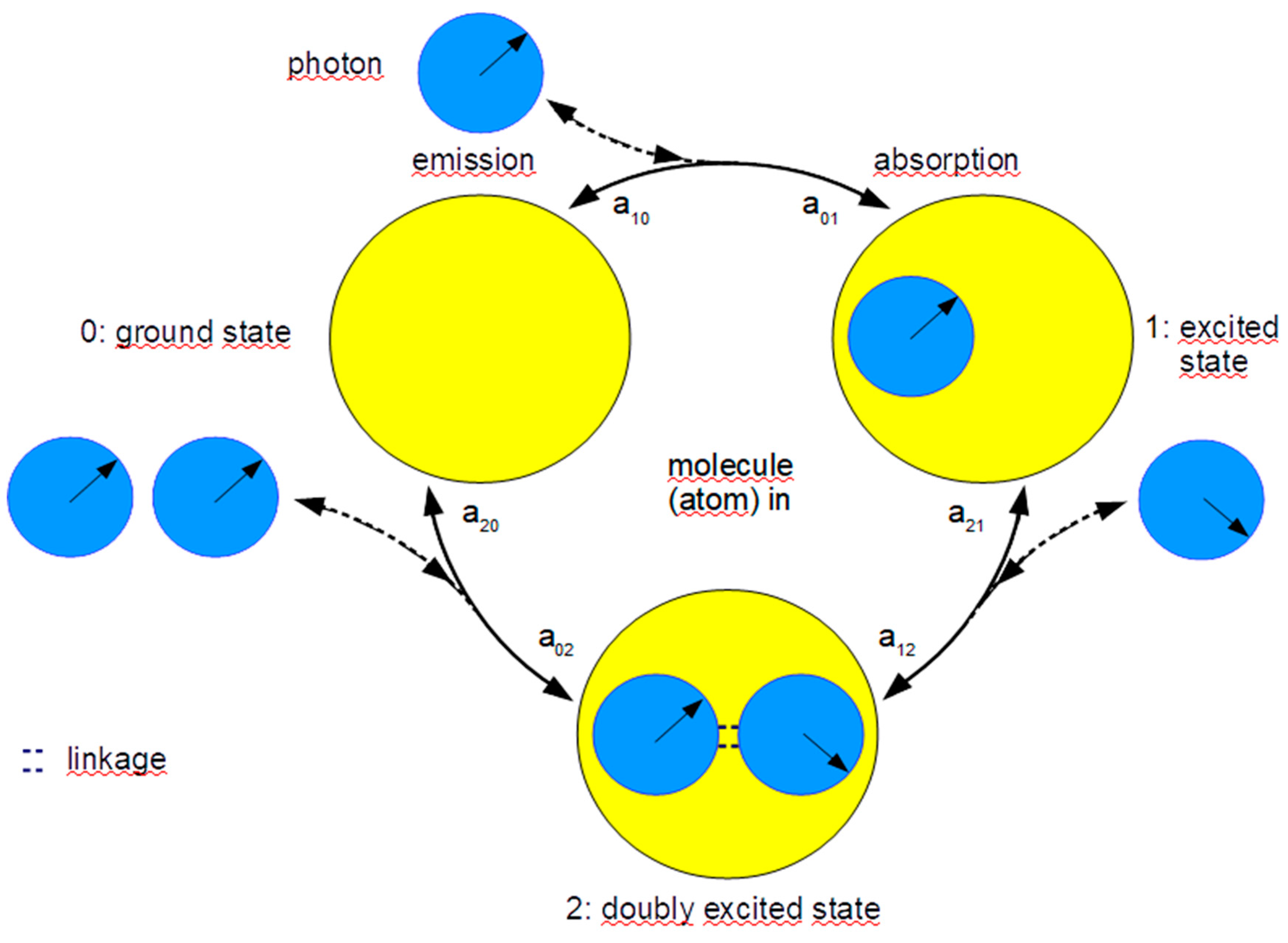

If one is not exclusively interested in the energy budget, but rather in the events themselves as described by the above equations, one can choose a highly schematized representation based on the structure. So this is what happens after Einstein 1916, if one thinks of the photon as an oscillating particle:

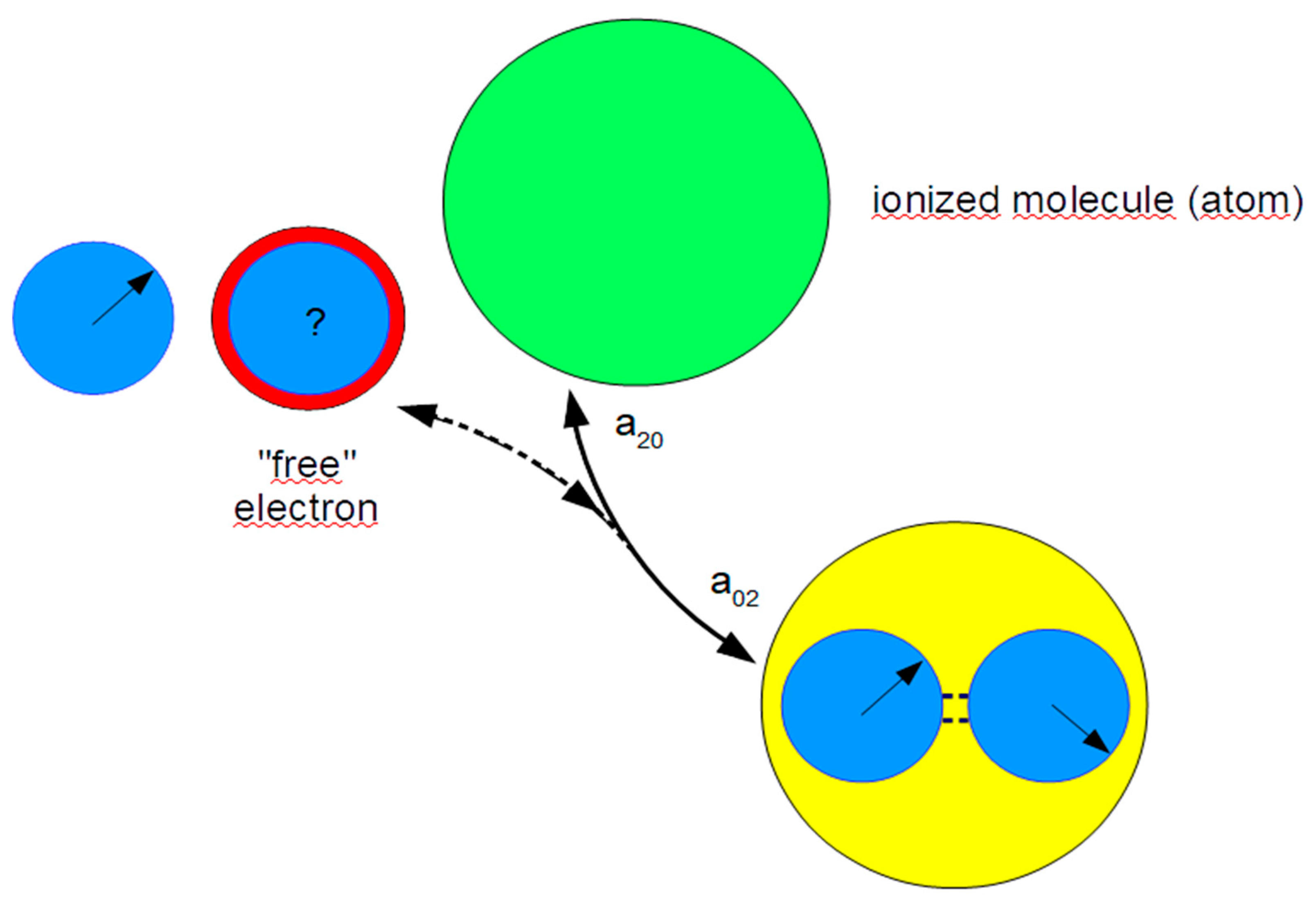

Figure 2.

Interaction between light and matter according to Einstein 1916. Atom: yellow circle; photon: blue circle.

Figure 2.

Interaction between light and matter according to Einstein 1916. Atom: yellow circle; photon: blue circle.

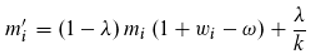

In this representation the photon appears as a circle with hand. This is because an oscillation cannot be represented schematically as easily as a rotation. We are now not only interested in the energy budget and thus the frequency, but also in the phase. A coincident hand position means that the photons involved oscillate in phase. Different hand position defines a phase difference, which is preserved in the time progression, because the light quanta we are interested in oscillate with the same frequency.

The above figure shows that the photon does not lose or change its phase during absorption. This finding results from the phenomenon of interference. The excited state of an atom is unstable (spontaneous emission); it has a half-life of about 10-8 seconds. Since photons do not interact directly with each other, only this period, the coherence time (in which a photon travels about 3m), remains for an interaction between excited atom and photon (one can also conclude that b10≥a10, otherwise spontaneous emission would generally occur before induced emission can happen which means that we could not observe interference). However, for interference to take place, the "stored" photon must also preserve its phase. That the phase is also preserved in the spontaneous emission is not so immediately obvious.

If the moment of this event is random, why not assume even more randomness, e. g. concerning the phase of the photon after emission? (It should be pointed out explicitly that the probability of spontaneous emission a10 during Δt is independent of how long the atom has been in the excited state. Unlike an organism, it does not age, so it has no memory with respect to its previous history. The situation is more similar to that of tossing an ideal coin: The probability that it will show head at the next toss is completely independent of how often head has already fallen before; the coin too has no memory).

The induced emission appears here as a somewhat mystical "fly-by" action (often the wave picture is strained: The photon as a wave shakes the atom, whereupon it passes from the excited to the ground state, losing its "stored" photon. As long as one accepts the wave-particle dualism, this idea is quite acceptable. It is problematic only if one does not do that). The "stored" photon thereby takes over the phase of the one flying by.

It is now to be investigated whether an even more descriptive, informative (though not simpler) model can be found for the interaction between radiation and matter by slight modification. It is represented in the following schematic diagram.

The model differs from the previous one on the one hand in that there is no induced emission, on the other hand a doubly excited state is postulated, a consequence of the absorption of two photons by the same shell electron. We now want to investigate the kinetics of the model.

For the emission events must be valid:

and for absorptions:

On a circle there are always two ways to get from A to B:

And:

We now have to choose the decay/formation probabilities a in such a way that the new model matches the original one as closely as possible. At first the assumption: a01=a12 makes sense, because both represent the probabilities for analogous processes, namely the absorption of a photon by the atom. But then, to be consistent with Einstein's model, the following must hold: a20=1. This is only approximately true. Like the excited state, the doubly excited state is also unstable. Compared to the first, however, it is much more short-lived. But the duration of its existence is sufficient to let the two photons interact with each other. From a20=1 it follows necessarily that a21=0, because if a doubly excited atom goes into the ground state practically immediately after its creation under emission of two photons, it cannot decay also in another way. We now need only one more assumption: namely, that a02=0 (at least approximately), in order to obtain agreement with Einstein's model and thus with Planck's radiation law. Let us summarize (sμ=8πhμ3/c3; c is the speed of light. It then follows from the following table that for visible light a01 is much larger than a10, as suspected earlier. For example, for light of 500nm, sμ is about 10-13, for electromagnetic radiation of 5nm about 10-7):

This simplifies the kinetic equations:

Because of the extremely short lifetime of the doubly excited state, at any time n

2=0. But this means that the rates x

2→1, x

2→0, x

1→2, x

0→2 are not observable and the observable (and relevant for the radiation law, because experimentally accessible) kinetics reduces to:

which agrees with that of Einstein's model (see Equations (1) and (2)). Thus, the modified model also satisfies Planck's radiation law. For the relative abundances of atoms n

0', n

1' and photons m

μ' at time t+Δt (when n

0, n

1 and m

μ are the frequencies at time t) holds:

We first note that in our model the formation and decay (the inverse of formation) probabilities for the same process do not always have the same value. Obviously, a

02 is not equal to a

20, the same is true for a

01 and a

10, respectively, and this is a contradiction to the common assumption in quantum theory [

20]. We have further found a plausible explanation for a

01=b

10 in the original model, because the induced emission is replaced by the succession of an absorption of another photon and the subsequent very rapid decay of the doubly excited atom (x

120 "replaces" y

10). So both times it is about an absorption and a mystical "fly-by" action does not exist. We can draw some more conclusions, e. g. that in the spontaneous emission the phase of the photon is indeed not lost. This is because the decay of the doubly excited state is also a spontaneous emission and that in it the phase is not lost, we know from the laser (more on this later) and from interference. We can now also think about the interaction of the photons in the doubly excited state. It starts of course only when both photons are "trapped" and then they are indistinguishable (also they have probably no memory). So whose phase is adopted, that of the first "swallowed" or the one "captured" afterwards should not be determined. In any case, the doubly excited state is the one where the copying process that is so important in replicator dynamics happens. We can make even more assumptions about the interaction in the doubly excited state and will do so when we consider the photoelectric effect and the double-slit experiment.

The Photoelectric Effect and the Double-Slit Experiment

If the energy of a photon is sufficient to "lift" an electron out from an atom (or molecule),

it may happen that we obtain a free electron and an ion as products of the interaction between photon and matter. We assume here that, although only one photon is relevant in the energy budget of the reaction, a doubly excited state is a prerequisite for its progress, and thus a photon pair and photon pair interaction, respectively, are crucial. As shown in

Figure 4, the doubly excited state can decay into an ion, a "free" electron with photon and a "free" photon, which is irrelevant for the energy budget as mentioned before (likewise, the reverse process can take place). This is an alternative to the event shown in the last figure (

Figure 3).

There are quite analogies to this process. They can be found, for example, in the context of chemistry in the form of catalyzed reactions, in which the catalyst is neither included in the list of educts nor in the one of products and is also not considered in the energy budget, but is nevertheless of decisive importance. If one thinks of a biochemical reaction, the second photon could be compared with a coenzyme in its function.

The photon, which remains bound to the electron in the schematized figure, is assumed in

Figure 4 to have an unknown phase (symbolized by a question mark). An experiment could change this: If one uses coherent light for the photoelectric effect and transports the released electrons at very low temperatures to another location, where one releases the photons again by a reverse reaction, one could investigate whether the coherence is preserved. We assume in the context of our considerations that the phase of the photon transported by the electron

is indeed preserved and the described experiment therefore provides a possibility of falsification.

Our assumption was that the photoelectric effect depends on photon pair interaction, i.e. for ionization the phase of the photons in the doubly excited state should be crucial. To investigate this hypothesis, we use the double-slit experiment or a generalization, so to speak, a "many-slit arrangement" as realized, for example, by the Fresnel zone plate. A source emits coherent light. It reaches an opaque plate with k transparent slits (or zones). Only through these can photons reach a detector behind it, which works on the basis of the photoelectric effect. The slits cause a path difference between the source and the detector, which causes a phase difference between the incoming photons. Thus, we have k different photons (photon classes) whose relative abundances are mi (i=1,...,k), where Σmi=1 (mi does not refer to the number of atoms N as mμ did, but to the number of photons M emitted by the source and reaching the target in total in the time interval Δt. We omit the photon index μ and assume that the light source is not only coherent but also monochromatic).

At first still to the concept of photon pair interference. The term interference originally refers to the interaction of partial waves e. g. emanating from the slits in the slit experiment, in the context of quantum theory also to that of photons or even a single photon interfering with itself after it is supposed to have taken different paths from the source to the detector through all slits simultaneously (auto-superposition and path integral; [

20]). The probability d that the photon is detected is then d=A

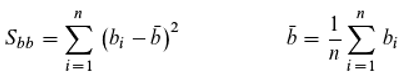

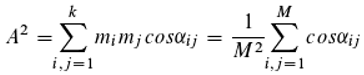

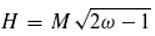

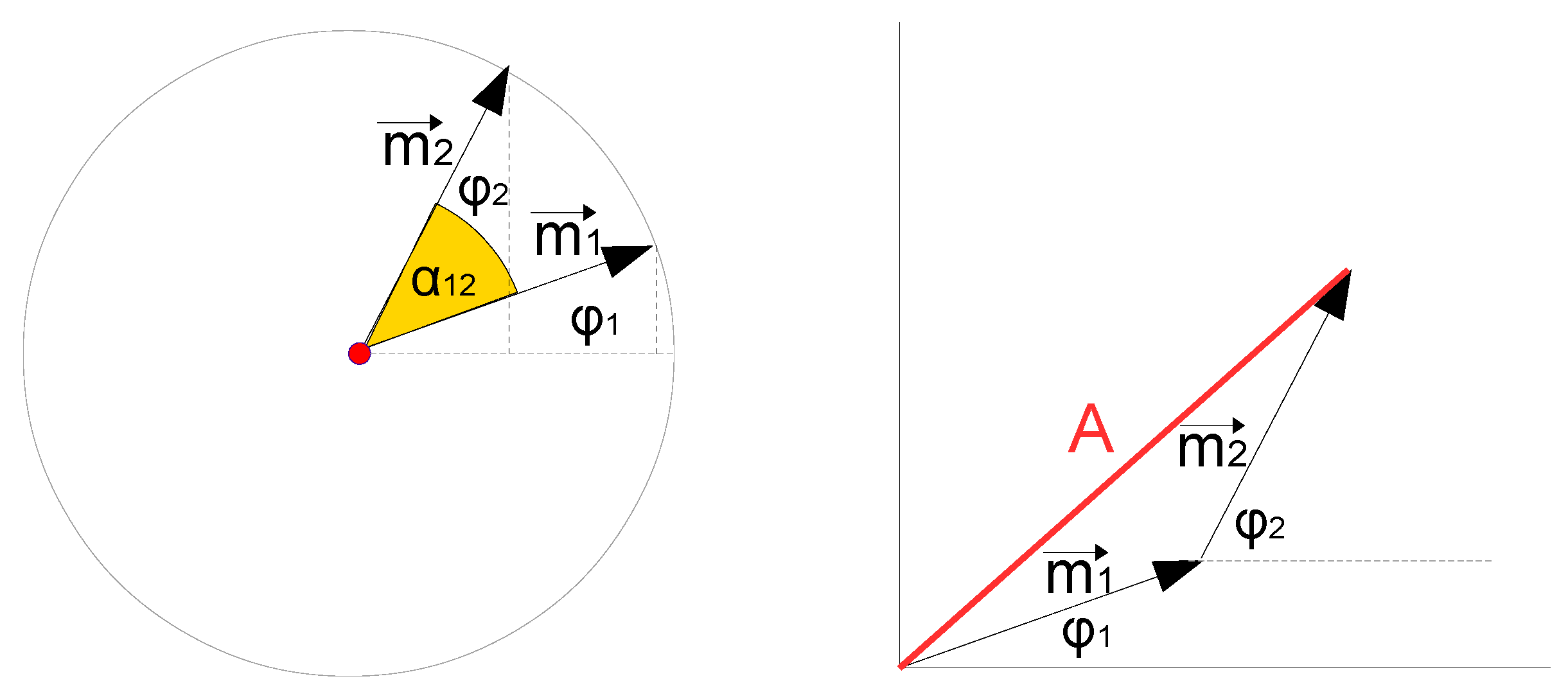

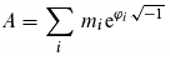

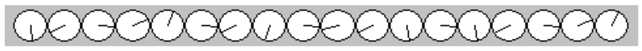

2 (according to Born's rule), where A is the amplitude, which is calculated for the slit experiment as follows:

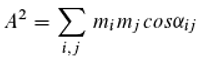

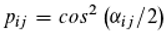

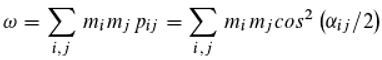

The amplitude A is thus expressed as a sum of complex numbers (since we use the letter i as an index, we do not follow the convention of representing the imaginary number by i). Here, φi represents the phase of those photons that reach the detector via the i-th slit. In fact, this mathematical formulation was crucial for the assumption of an auto-superposition. However, one can also use other mathematical representations. One of them, for A2 (and thus also for the detection probability d), which has nothing – at least not apparently – to do with the summation of complex numbers or also vectors, is:

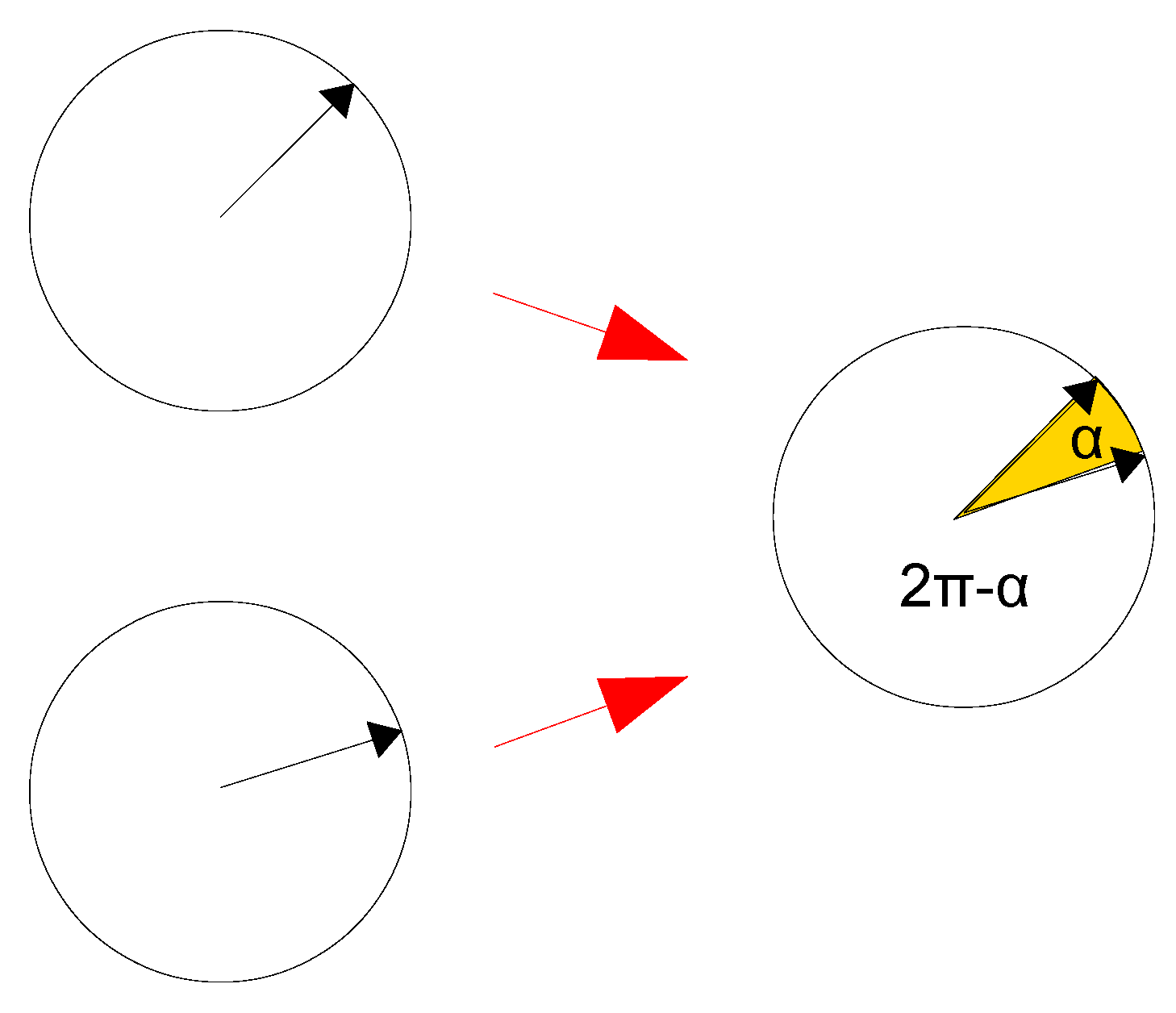

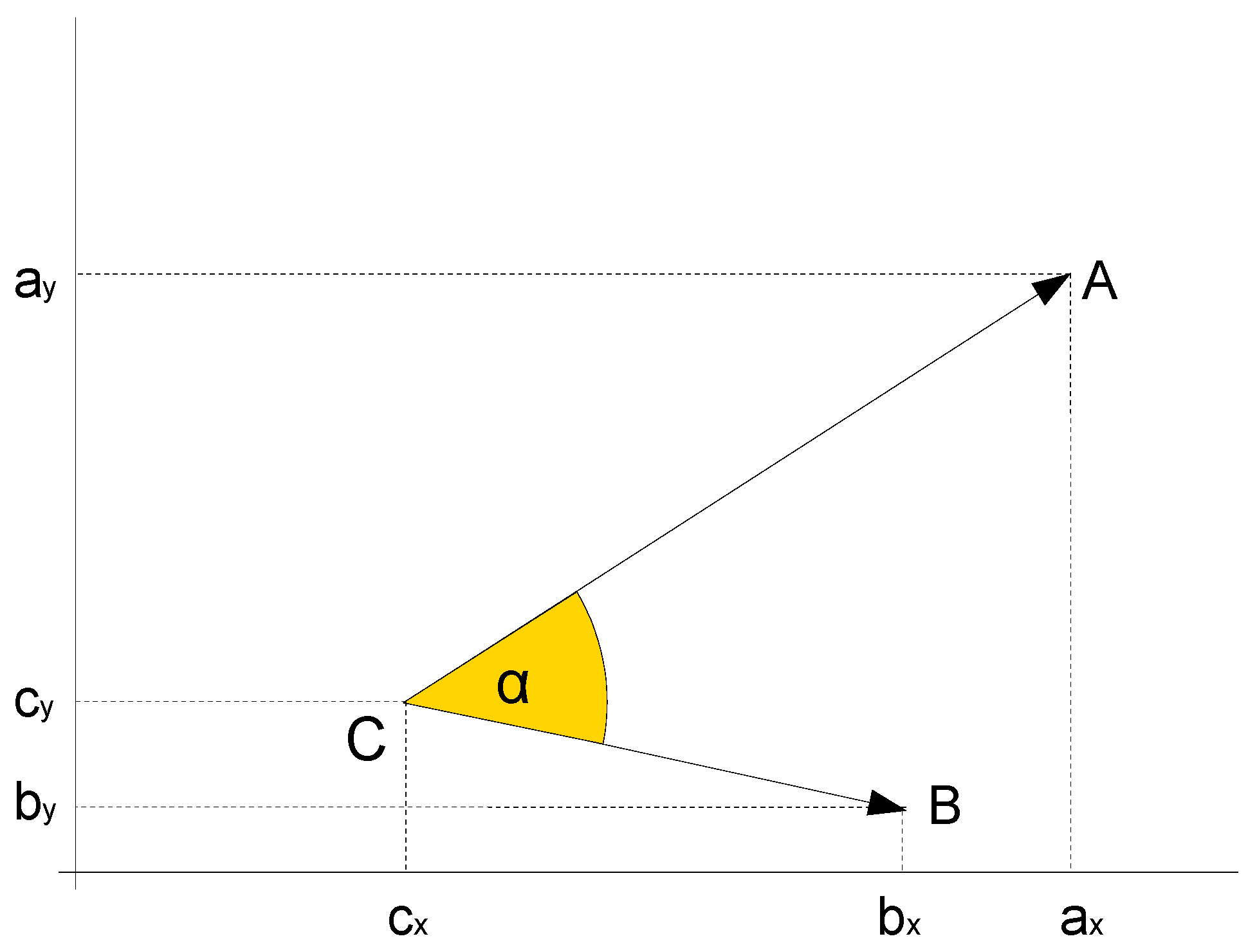

as is proved in the supplement. α refers to the phase difference of two photons as shown in the following figure:

Verbally formulated this means that quite generally A

2 corresponds to the mean of all pairwise comparisons of photon phases (expressed as cos α

ij, see

Figure 5). This equation can also be interpreted, but it leads to a completely different idea than the previous one, namely that the pairwise interaction of photons, pair interference, is crucial for the interaction between light and matter. This is the view that is attempted to be developed here.

The following figure will once again make clear the notation used for phase comparison and amplitude calculation.

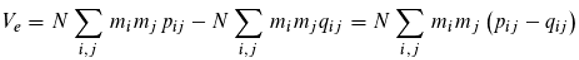

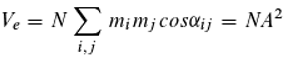

We are now interested in the number of released electrons Ve at the detector surface reachable by the light. If the source emits a very large number of photons and also a very large number of photons reach the detector, Ve depends only on the number N of irradiated detector atoms – and, since we can regard each atom as its own detector – further on the detection probability d per atom. This results in:

Let us now return to the double slit experiment (k=2). If the slits are vertically in the intermediate wall and the detector is moved horizontally in the background, α12 changes from 0 to π and further to 2π (or back to 0) and according to Equation (7) also the number of released electrons changes, thus an interference pattern arises, as it is actually observed in the realization of this experiment.

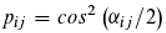

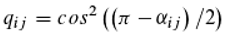

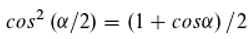

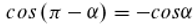

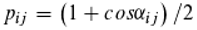

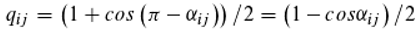

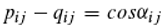

We now want to find out what events take place in the photoelectric effect. We assume that the probability pij for ionization by light depends on the phase difference or the phase angle between the two photons "trapped" in the doubly excited state. The smaller the phase difference, the larger pij should be. Also, the probability qij for the reverse process, the trapping of an electron, should depend on the phase angle between the photon transported by the electron and another one. However, we suspect that the larger the phase difference, the larger qij should be.

In

Figure 5, the phases of the photons are symbolized by hands. There are now two angles, α and 2π-α, between each of the hands and it should be irrelevant for the calculation of the transition probabilities which of the two angles we use. The cosine of an angle would have this property [cosα=cos(2π-α)], but yields values between minus one and one. Probabilities, on the other hand, are between zero and one. We now conjecture that the ionization and reionization probabilities in the presence of photons i and j as part of the doubly excited state are given by the following equations, which satisfy both conditions:

If ionization does not occur (because the phase difference is relatively large), the doubly excited state decays with the release of two photons, as described above, but the electron remains in the atomic bond. Conversely, if the phase difference is small, the reverse process, the capture of an electron, may fail.

We now assume that M>>N, i.e. there are always enough photons (M refers to the photons emitted by the source and reach the detector in the period Δt, N to the detector atoms (atoms of the surface) which can be reached by the light). Then, any atom will enter the doubly excited state and will be ionized with probability pij. According to our model, the "excess" photon will immediately leave the atom's sphere of influence, while the (much slower) electron will remain in a meta-stable state, where it is not yet completely free, but still remains associated with the atom. Therefore, with the participation of another photon – not the one emitted by the atom during ionization – re-ionization can occur with probability qij. If not, the electron is now finally released. This interplay of ionization and re-ionization shall finally determine the number Ve of released electrons, i.e.:

are

From this follows:

And therefore is valid:

So, with the help of the photon pair interference, one can definitely create a model which agrees with the observation in the case of the double-slit experiment. Of course, the "microcosmic" processes postulated here remain speculative and some things stay uncertain. Three electrons are involved in the process described. If the semi-free electron can exchange photons, there could be four. Possibly the cycle of ionization and re-ionization at an atom also takes place several times before the electron is finally free.

Besides simultaneous interaction, as assumed here, there would also be the possibility of successive interaction to produce the interference pattern in the double-slit experiment. This of course presupposes that matter has some kind of memory. This option is studied in [

2].

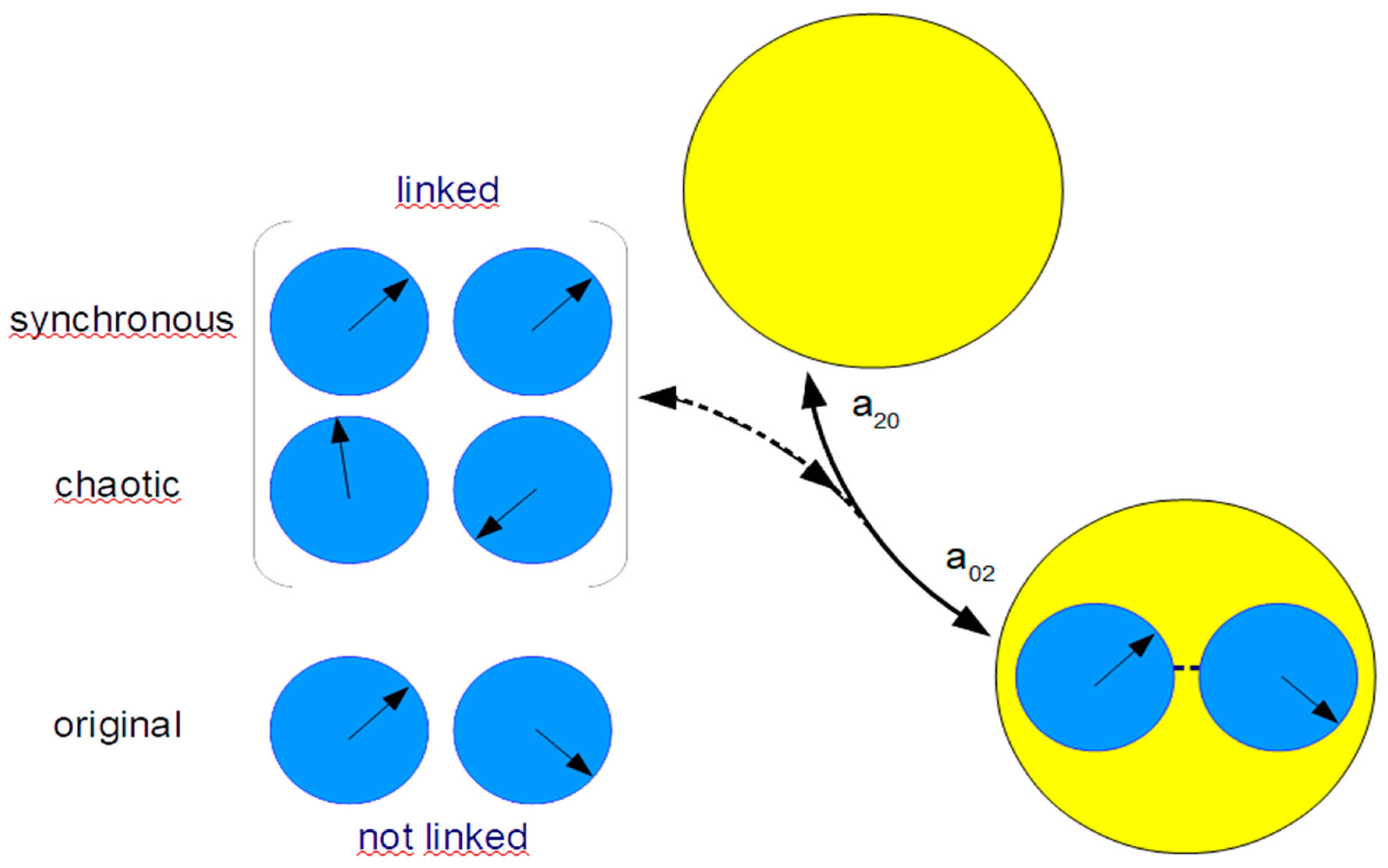

Replicator Dynamics and Laser

We now return to the interaction of light and matter and in particular to the doubly excited state. It is always extremely short-lived and may decay releasing two photons that have somehow been coupled during its existence. The best analogue the author can think of is linked pendulums, whose phases often align so that they eventually oscillate synchronously (in phase or with a phase difference of π). Sometimes chaotic behavior also occurs.

Similarly as with the linked pendulums, also with the photons in the doubly excited state a synchronization of the oscillation often occurs. The special characteristic, however, is that this happens in such a way that one of the two photons takes over the phase of the other, so there is no arbitrary alignment (no blending of the replicators occurs, but copying). According to the model, neither photon is preferred; once both photons are trapped, neither remembers which came first. What happens in the case that synchronization does not occur? In this respect, there are two possibilities: as in the case of the two pendulums, a chaotic development could have occurred. Then the phases of the two photons are random or pseudo-random. But there could also be no coupling at all – despite their common stay in the doubly excited state – and the photons leave the atom with the phase they had before (

Figure 7). Which of these is the case can, as we shall see, be determined by simulation. However, we assume here that the smaller the phase difference was originally, the higher the probability of synchronization p

ij. Taking into account those considerations we had made in the last section, we obtain (see also Equation (8)):

and with the counter probability 1-pij an arbitrary phase occurs with the photons or – as an alternative possibility – the phase remains.

In thermal equilibrium, the vast majority of atoms are in the ground state. For example, for visible light of wavelength 500nm, at room temperature (27°C), the excited/ground state ratio is only 2*10-42 (and the number of photons is correspondingly low relative to the number of atoms). Even at extremely high temperatures, there are never more excited atoms than ground state atoms in thermal equilibrium. However, one can create a population inversion far from equilibrium in an "active medium" and this is one of the prerequisites for the laser. Another is that the light of the relevant frequency stays as long as possible in the active medium. To do this, one confines it by two parallel mirrors (one is partially transparent) whose distance is an integer multiple of the wavelength. The photons thus move back and forth like a ball in table tennis – only there are an enormous number of balls and they are incredibly fast – and an interaction with atoms of the active medium therefore becomes extremely probable (a direct interaction of the light quanta with each other, however, does not take place).

In the dynamic equilibrium, as many photons leave the system in the time interval Δt through the partially transparent mirror (or by other means) as single excited atoms are produced by population inversion (by "pumping"). Pumping is enabled, for example, by absorption of higher-frequency light (details are not relevant here) and is then proportional to the number of these higher-frequency photons, their absorption probability, and the number of atoms in the ground state ("gain"). Emission (X1→0) results in conversion to photons of the "desired" frequency, some of which leave the system via the partially transparent mirror. This "loss" is proportional to the number of photons. Gain and loss thus control the number of photons in the system, which can therefore be larger than the number of atoms in the active medium. This in turn has two consequences: 1) emission can occur in two ways, spontaneously (x10=a10n1) or via the doubly excited state (x120=a12m n1= a01m n1). If we choose for simplicity m=1 (there are as many photons as atoms), then for example for visible light of 500 nm the relation spontaneous to "induced" emission (or a10/a01) takes approximately the value 10-13. Thus, spontaneous emission can be neglected compared to that which goes through the doubly excited state (absorption of a second photon plus decay of this state). 2) Another consequence of the high photon number is that a substantial part of those photons whose absorption lifts the atoms above the ground state are not higher-frequency pump photons at all but laser-produced light quanta. The relation between these two is an essential model component (loss factor λ).

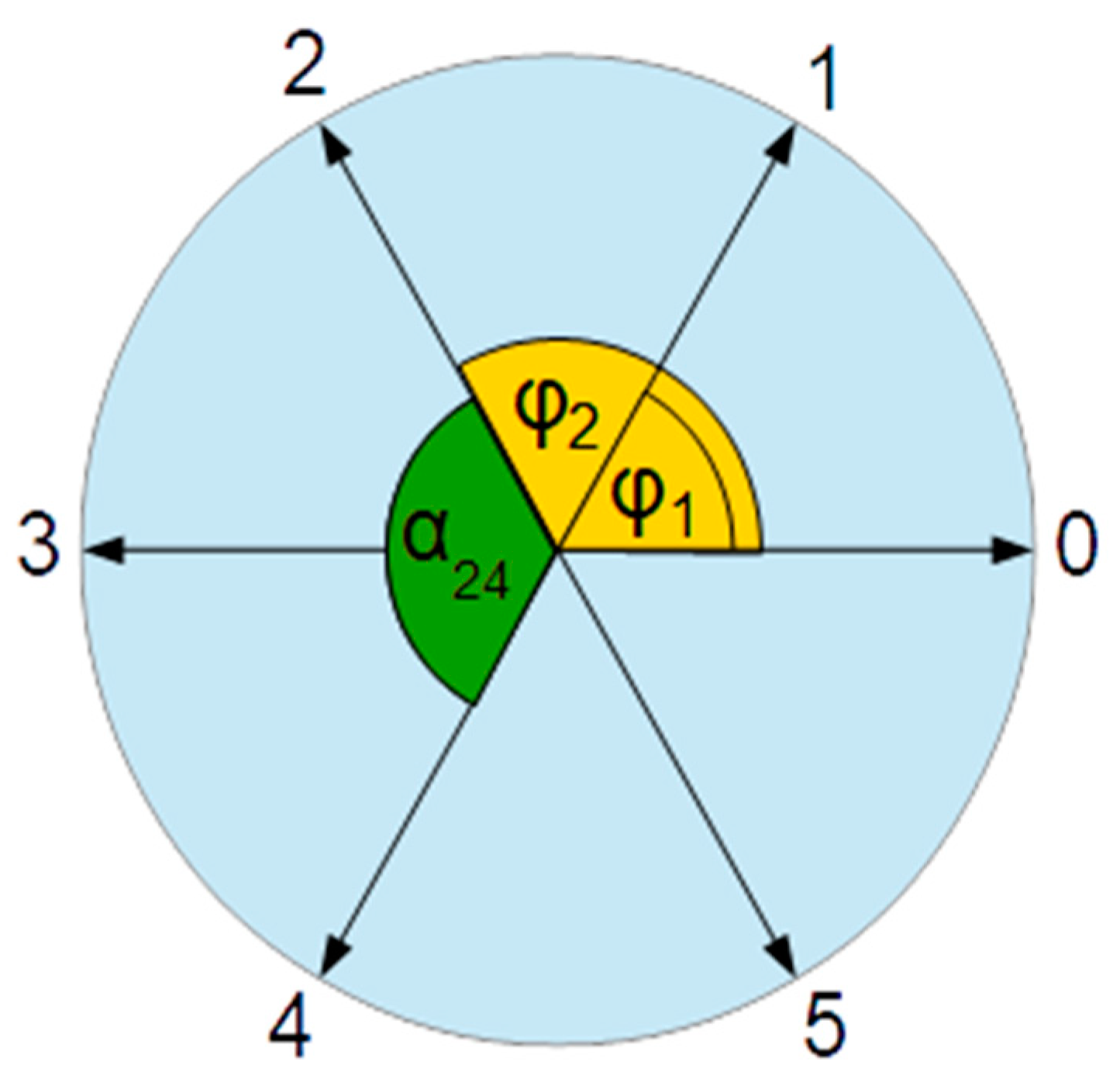

Laser light has many remarkable characteristics; it is monochromatic, monoaxial, and usually linearly polarized as well. We presuppose all of this in our model. What we are specifically interested in is how it comes about, through density-dependent selection, that it is also monophasic (coherent). If non-coherent light is used for pumping (which is generally the case), the photons in the singly excited state will have arbitrary phase (if they were excited by pump photons). The only way the light in the laser can then become coherent is by linking photons in the doubly excited state. In order to be able to use the basic considerations of replicator dynamics, we want to simplify the model with respect to reality by specifying that the phase difference between two photons cannot be arbitrarily small, i.e., we allow only discrete differences. There are k "phase classes" (corresponding in replicator dynamics to genotypes competing with each other) that differ from each other by an integer multiple of a phase angle φ=2π/k (

Figure 8), such that φ

i=iφ (i=1,...,k). The larger k and the smaller φ is, the closer the model approximates reality.

In the context of the model, we further use discrete time units Δt.

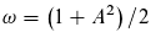

Whether synchronization occurs during the decay of the doubly excited state depends, as already mentioned, on the phase difference of the photon pair involved according to Equation (17). The average probability for a synchronization is then:

Because of Equations (6) and (11) we get further:

and the counter probability 1-ω=(1-A

2)/2 is the average probability for the photons to have any phase after the decay of the doubly excited state (this is an assumption we make here; as already explained, the original phase could also be preserved; see

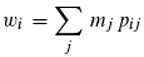

Figure 7). If we are interested in the change of an arbitrary phase class i by density-dependent selection, as is usual in replicator dynamics, we must define its fitness w

i for this purpose. It is obviously:

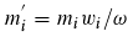

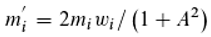

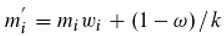

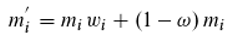

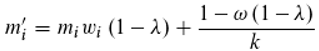

since all phase classes j contribute to the propagation of a particular (i) with probability pij. The mean fitness is then (since we operate with relative frequencies) Σmiwi, which corresponds to the synchronization probability (Equation (18)). Thus, ω is the mean fitness. The relative frequency (in terms of synchronized photons) mi' of photons of phase class i at time t+Δt, when mi was the abundance at time t, is given by:

Respectively

Obviously, Equation (21) is the discrete replicator equation. These equation describes as mentioned the change of the individual phase classes with respect to the totality of the synchronized photons, but not with respect to the whole photon population, because there are also non-synchronized light quanta. If we take these into account as well and the latter have a random phase, the result for mi' is:

If the unsynchronized photons do not change the phase, on the other hand, the result is:

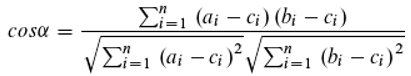

One can now also consider gain (λ/k) and loss (-λmi) in the dynamic equilibrium for any photon class i. λ (0≤λ≤1) is the loss constant. From Equation (23) then follows:

from Equation (24) on the other hand

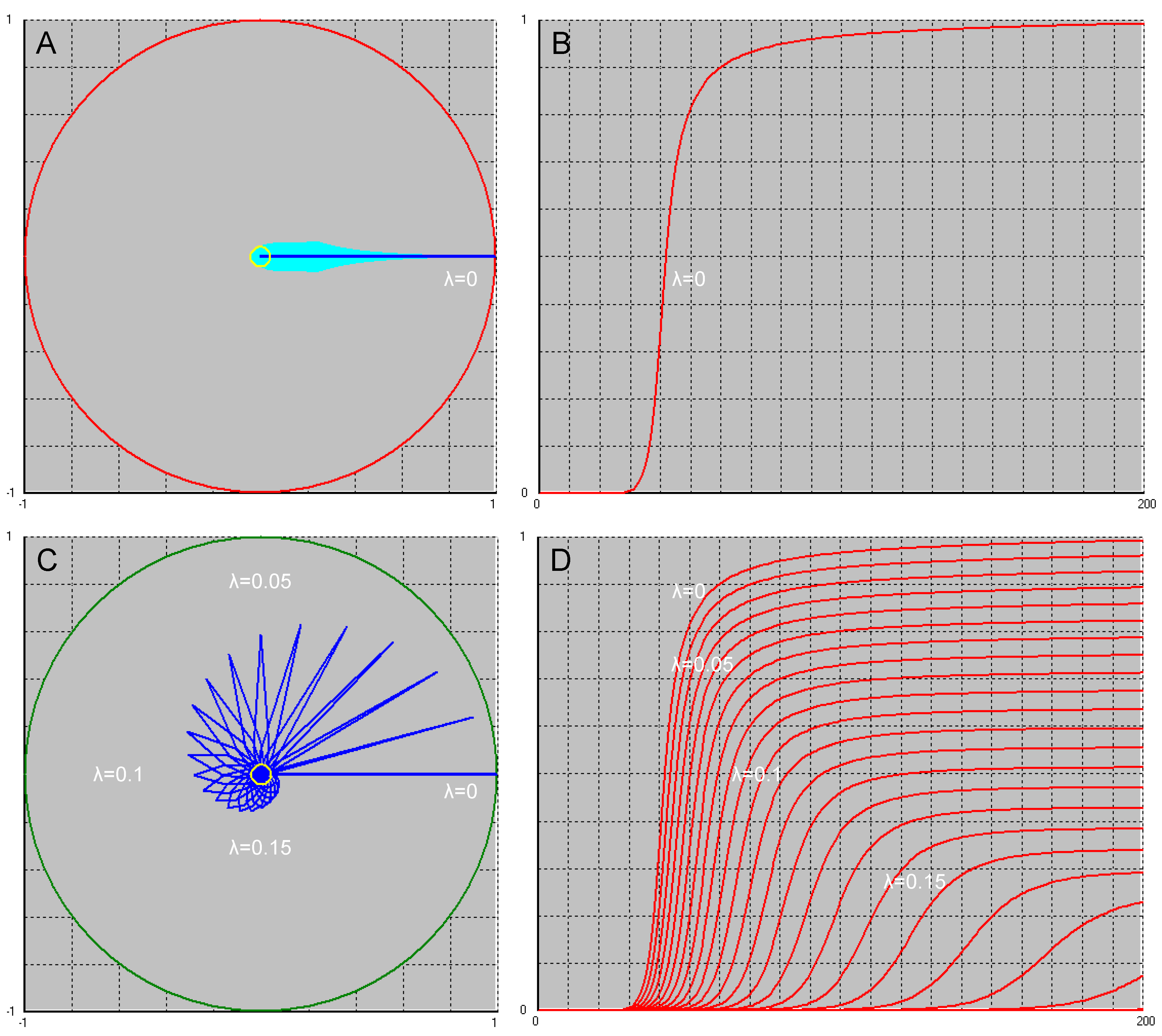

In the case of λ=0, Equation (25) is identical to Equations (23) and (26) is identical to Equation (24). We now use Equations (25) and (26) as a basis for simulations. It turns out that with Equation (25) (coupling leads to synchronization or chaos) no coherent light can be produced. It thus follows that when two photons are coupled in the doubly excited state, no chaos can be generated, or at least no arbitrary phases. If phase copying does not occur, the phases are apparently preserved, as assumed in Equation (26). The model which is based on Equation (26) now shows that it depends on the loss constant λ how coherent the resulting light can be. It is monophasic only when λ=0. If λ is larger, the coherence decreases, resulting in a phase distribution that becomes wider and wider around the maximum. Around λ≈0.2 finally a uniform distribution is obtained and thus there is no coherence anymore (

Figure 9C).

Since stochastic fluctuations are not included in the model, it is assumed that at the beginning one phase class in the photon ensemble deviates from the uniform distribution by a tiny value, e. g. is more frequent than all others. Density-dependent selection initially increases not only the frequency of this phase, but also those that are adjacent to it (

Figure 9A). However, if λ=0, one phase prevails and completely displaces all others.

Figure 9B shows how the amplitude square changes with time in this case.

Figure 9C, on the other hand, demonstrates how the phase distribution changes when λ becomes larger, and

Figure 9D illustrates the effect this has on the temporal development of the amplitude square.

Of course, in reality, when coherent light is created in the laser, there are neither discrete time steps (generations), as assumed in the model, nor phase classes. Therefore, the model represents a strong simplification.

Couldn't coherent light also arise without the copying of phases and therefore without the photon being a replicator carrier, e. g. by the phases of the coupled photons merely becoming more similar but not identical? The possibility should also be investigated, but this is beyond the scope of the present paper.

In the following, we are interested in the relation between mean fitness and entropy of the photon ensemble. For this purpose, we have to consider that the characteristic we are interested in here is the phase, which (outside the model just described) is not discrete.

An Information Measure for Continuous, Cyclically Closed Features

Usually symbols, i.e., discrete, nominal units, form the basis of information (0's and 1's or the letters), but here we want to study the case where the basis is metric and continuous, as well as being cyclically closed. It can be thought of as a hand position on a clock face.

In one direction – from letters to hand position – one can translate. One must specify only a translation key, e. g. as follows:

becomes

Then

is equivalent to the string: “TO_BE_OR_NOT_TO_BE”.

In the case of letters, one assumes that the distance between any two symbols is the same for all symbols (say: one) and that there is nothing in between. On the contrary, between two hand positions fit infinitely many more. Therefore a translation in the other direction is not possible: one would need infinitely many letters. The distance between two hand positions is also not the same for all, but can be represented by an angle α (or by a trigonometric function, e. g. cos α).

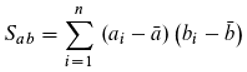

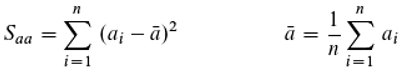

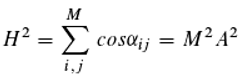

The second difference is that each hand position occurs with probability zero, since there are infinitely many. The Shannon information connects probability (or frequency) with information [

37], which is not possible here. C. Shannon has also investigated how much information can be transmitted by waves, i.e. on a continuous basis. As an alternative starting point, however, a very important information measure in bivariate statistics can be used, namely the coefficient of determination (the square of the correlation). This is because there is a very interesting mathematical relationship between the cosine of an angle and the correlation coefficient (M. Tiefenbrunner, pers. comm.), which is important in statistics and information theory (

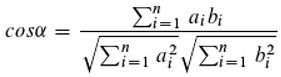

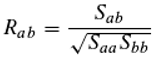

Figure 10).

The cosine of the angle α enclosed by two vectors with common origin in the Cartesian coordinate system, as shown in

Figure 10, is given by:

or, for any number of dimensions (i=1...n):

Here ai, bi, ci are the coordinates of the points A, B, C in the i-th dimension. And if C is the origin (C={0,0,...}):

We now move from geometry to statistics. The correlation coefficient R

ab is a statistical measure of the correlation between two features A and B. Its square, the coefficient of determination, indicates how much knowledge one can gain about feature A by examining feature B (and vice versa) and is thus a measure of information. One can define the correlation coefficient R (according to Pearson) using the variances S

aa and S

bb of the features and the covariance S

ab:

It is now immediately obvious that Equation (28) (about the cosine) and Equation (29) (about the correlation) agree completely, if one subtracts the common mean from all ai (coordinates of the feature A in the object space with n dimensions) and proceeds in the same way with the feature B (Equations (30)–(32)). So there is a remarkable connection between geometry and statistics, which we can make use of here by considering the cosine of the angle between two hand positions as a correlation. If we have entities, as described before, whose feature is continuous and cyclically closed (an oscillator or rotator fulfills this condition; imagine, for instance, clocks with only one hand each, which we want to assume all rotate at the same rate, but not necessarily all show the same time - so the phase difference remains constant), we can ask about the information that is due to an ensemble of such entities. The information measure we choose should satisfy two conditions:

Additivity: If two originally separate ensembles form a new one, the information content of the new ensemble should be the sum of the separate ones (Shannon information fulfills this requirement).

The information measure should not be negative.

As we have already seen, the cosine has some very useful properties: cos 0=1, as well as that it does not matter which of the two angles between two hands you take (cos α = cos (2π-α)). However, the cosine of an angle moves – just like the correlation coefficient – between minus one and one, so it can be negative, which we do not want. R2, the coefficient of determination, does not have this undesirable property, but it is not applicable to an ensemble. However, we already know a possible replacement for R2, namely the sum of the phase correlations of all possible photon pairs. This sum is always positive and thus fulfills condition two, but it is not additive. The absolute value of the root of this matrix, however, fulfills condition 1 too. As a result of plausibility reasoning (not due to compelling conclusion), we therefore obtain for the information content H (M is the number of Photons):

so that H=MA. Perhaps we need a little more explanation. We start with Equation (6), but now each phase class consists of exactly one photon and therefore k=M and mi=mj=1/M. It can be concluded from this:

and so we reach Equation (33). As is well known, the amplitude can also be written as vector sum (

Figure 6, right):

and in this sense additivity (requirement 1) is given. The vectors

zi have the length 1/M and the angle φ

i. So in photon ensembles the amplitude (multiplied with the photon number) plays the role of information content or negentropy. Returning now to the laser from the perspective of replicator theory, we are interested in the relationship between information content and mean fitness and find:

Acknowledgements

Thanks especially to my discussion partners Martin Tiefenbrunner, who taught me a lot about the connection between geometry and statistics, and Hans De Raedt, whose fascinating views on quantum theory and probability theory brought a lot that was unknown to me.

References

- Antoci, S.; Liebscher, D.-E. The third way to quantum mechanics is the forgotten first. arXiv:physics/9704028.

- De Raedt, H.; Michielsen, K. Event-by-event simulation of quantum phenomena. Ann. Phys. 2012, 524, 393–410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Michielsen, K.; De Raedt, H. Event-by-event simulation of experiments to create entanglement and violate Bell inequalities. Proc. of SPIE 2013, 8832, 540–555. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Raedt, H.; Katsnelson, M.I.; Michielsen, K. Quantum theory as the most robust description of reproducible experiments. Ann. Phys. 2014, 347, 45–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Raedt, H.; Katsnelson, M.I.; Michielsen, K. Quantum theory as plausible reasoning applied to data obtained by robust experiments. Phil. Trans. R. Soc. A 2016, 374, 20150233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Donker, H.C.; Katsnelson, M.I.; De Raedt, H.; Michielsen, K. Logical inference approach to relativistic quantum mechanics: Derivation of the Klein-Gordon equation. Ann. Phys. 2016, 372, 74–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Raedt, H.; Katsnelson, M.I.; Michielsen, K. Logical inference derivation of the quantum theoretical description of Stern-Gerlach and Einstein-Podolsky-Rosen-Bohm experiments. Ann. Phys. 2018, 396, 96–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Raedt, H.; Katsnelson, M.I.; Willsch, D.; Michielsen, K. Separation of conditions as a prerequisite for quantum theory. Ann. Phys. 2019, 403, 112–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eigen, M. Selforganisation of matter and the evolution of biological macromolecules. Die Naturwissenschaften 1971, 58, 465–523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Einstein, A. Über einen die Erzeugung und Verwandlung des Lichtes betreffenden heuristischen Gesichtspunkt. Ann. Phys. 1905, 322, 132–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Einstein, A. Beiträge zur Quantentheorie, Deutsche Physikalische Gesellschaft. Verhandlungen 1914, 16, 820–828. [Google Scholar]

- Einstein, A. Strahlungs-Emission und -Absortion nach der Quantentheorie, Deutsche Physikalische Gesellschaft. Verhandlungen 1916, 18, 318–323. [Google Scholar]

- Einstein, A. Zur Quantentheorie der Strahlung. Physikalische Zeitschrift 1917, 18, 121–128. [Google Scholar]

- Einstein, A. Zum Quantensatz von Sommerfeld und Epstein, Deutsche Physikalische Gesellschaft. Verhandlungen 1919, 19, 82–92. [Google Scholar]

- Einstein, A. Quantentheorie des einatomigen idealen Gases, erste und zweite Abhandlung. Zeitschrift für Physik 1924, 25, 37–41. [Google Scholar]

- Einstein, A.; Podolsky, B.; Rosen, N. Can Quantum-Mechanical Description of Physical Reality Be Considered Complete? Physical review 1935, 47, 777–780. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Einstein, A. Physik und Realität. Journal of the Franklin Institute 1936, 221, 313–347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feynman, R.P. Space-time approach to non-relativistic quantum mechanics. Rev. Mod. Phys. 1948, 20, 367–387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feynman, R.P.; Leighton, R.B.; Sands, M. Vorlesungen über Physik, Band I, Mechanik, Strahlung, Wärme, R. Oldenbourg Verlag München Wien, 1988 (orig. 1963-1965). https://www.feynmanlectures.caltech.edu/.

- Feynman, R.P.; Leighton, R.B.; Sands, M. Vorlesungen über Physik, Band III, Quantenmechanik, R. Oldenbourg Verlag München Wien, 1988 (orig. 1963-1965). https://www.feynmanlectures.caltech.edu/.

- Fisher, R.A. The genetical theory of natural selection. Oxford, Clarendon Press (1930).

- Frank, S.A. Natural selection maximizes Fisher information. J. Evol. Biol. 2009, 22, 231–244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Frank, S.A. Natural selection, V. How to read the fundamental equations of evolutionary change in terms of information theory. J. Evol. Biol. 2012, 25, 2377–2396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frank, S.A.; Natural selection, V.I. Partitioning the information in fitness and characters by path analysis. J. Evol. Biol. 2013, 26, 457–471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frieden, B.R.; Plastino, A.; Shoffer, B.H. ; Population genetics from an information perspective. J. Theor. Biol. 2001, 208, 49–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Haken, H.; Sauermann, H. Nonlinear Interaction of Laser Modes. Zeitschrift für Physik 1963, 173, 261–275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haken, H. A Nonlinear Theory of Laser Noise and Coherence. I. Zeitschrift für Physik 1964, 181, 96–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haken, H. Theory of coherence of laser light. Physical review letters 1964, 13, 329–331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haken, H. A Nonlinear Theory of Laser Noise and Coherence. II. Zeitschrift für Physik 1965, 182, 346–359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haken, H. Erfolgsgeheimnisse der Natur, Deutsche Verlagsanstalt, 1981.

- Haken, H. Synergetics; An Introduction. Springer-Verlag (1983).

- Heisenberg, W. Über quantentheoretische Umdeutung kinematischer und mechanischer Beziehungen. Zeitschrift für Physik 1925, 33, 879–893. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hofbauer, J.; Sigmund, K. Evolutionsheorie und dynamische Systeme. Mathematische Aspekte der Selektion, Paul Parey, 1984.

- Lotka, A.J. Undamped oscillations derived from the law of mass action. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1920, 42, 1595–1598. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schrödinger, E. Quantisierung als Eigenwertproblem. Ann. Phys. 1926, 79, 489–527. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schuster, P. Sigmund K., Replicator Dynamics. J. theor. Biology 1983, 100, 533–538. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shannon, C.E.; Weaver, W. The mathematical theory of communication, University of Illinois Press, Urbana and Chicago, 29, 1963.

- Tiefenbrunner, W. Selektion und Mutation aus informationstheoretischer Sicht - Grenzen der Erhaltbarkeit von genetischer Information. Z. Naturforsch 1995, 50c, 883–894. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tiefenbrunner, W. Change of information content due to natural selection in populations with and without recombination. bioRxiv. [CrossRef]

- Tiefenbrunner, W. Change of information by positive frequency-dependent selection in two very different models (laser-like and chirality of shell-coiling in the snail Partula suturalis), bioRχiv. [CrossRef]

- Tiefenbrunner, W. Entropy change due to selection in replicator and recombinator systems with randomly chosen interaction matrix values. bioRχiv. [CrossRef]

- Volterra, V. Leçons sur la theorie mathematique de la lutte pour la vie, Paris, Gauthier Villars, 1931.

- Wentzel, G. Zur Quantenoptik. Zeitschrift für Physik 1924, 193-199.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

and for the inversion

and for the inversion

and

and

with

with