Submitted:

31 January 2023

Posted:

01 February 2023

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

Introduction

Role of Mitochondria in Brain Energy Metabolism, Calcium Homeostasis, and Signal Transduction

Role of Mitochondria in Degenerative Disease

Mitochondria Bioenergy in Parkinson’s Disease, Huntington Disease Rodents Animal Models

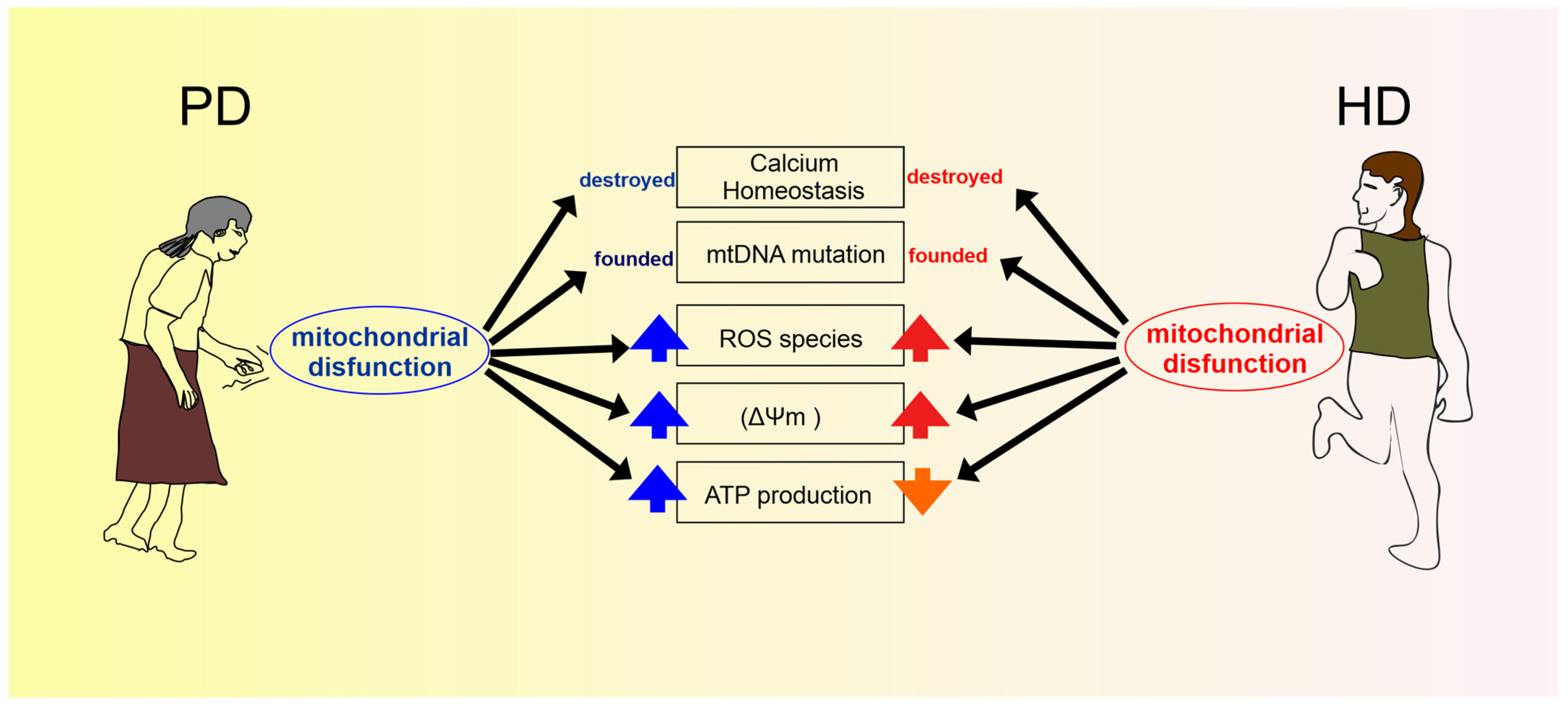

Parkinson Disease

Huntington Disease

Mitochondria Bioenergy in Parkinson’s Disease, Huntington Disease, Human Evidences

Discussion

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Sagan L. On the origin of mitosing cells. J Theor Biol. 1967 Mar;14, 255-74. https://doi.org/10.1016/0022-5193(67)90079-3. PMID: 11541392.

- Pizzorno J. Mitochondria-Fundamental to Life and Health. Integr Med. 2014 Apr;13, 8-15. PMID: 26770084; PMCID: PMC4684129.

- Alberts B, Johnson A, Lewis J, et al. New York: Garland Science; 2002.

- Golpich M, Amini E, Mohamed Z, Azman Ali R, Mohamed Ibrahim N, Ahmadiani A. Mitochondrial Dysfunction and Biogenesis in Neurodegenerative diseases: Pathogenesis and Treatment. CNS Neurosci Ther. 2017 Jan;23, 5-22. https://doi.org/10.1111/cns.12655. Epub 2016 Nov 22. PMID: 27873462; PMCID: PMC6492703.

- Gao J, Wang L, Liu J, Xie F, Su B, Wang X. Abnormalities of Mitochondrial Dynamics in Neurodegenerative Diseases. Antioxidants 2017 Apr 5;6, 25. https://doi.org/10.3390/antiox6020025. PMID: 28379197; PMCID: PMC5488005.

- Wang Y, Xu E, Musich PR, Lin F. Mitochondrial dysfunction in neurodegenerative diseases and the potential countermeasure. CNS Neurosci Ther. 2019 Jul;25, 816-824. https://doi.org/10.1111/cns.13116. Epub 2019 Mar 19. PMID: 30889315; PMCID: PMC6566063.

- Jadiya P, Garbincius JF, Elrod JW. Reappraisal of metabolic dysfunction in neurodegeneration: Focus on mitochondrial function and calcium signaling. Acta Neuropathol Commun. 2021 Jul 7;9, 124. https://doi.org/10.1186/s40478-021-01224-4. PMID: 34233766; PMCID: PMC8262011.

- Zhu XH, Qiao H, Du F, Xiong Q, Liu X, Zhang X, Ugurbil K, Chen W. Quantitative imaging of energy expenditure in human brain. Neuroimage. 2012 May 1;60, 2107-17. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neuroimage.2012.02.013. Epub 2012 Feb 17. PMID: 22487547; PMCID: PMC3325488.

- Vergara RC, Jaramillo-Riveri S, Luarte A, Moënne-Loccoz C, Fuentes R, Couve A, Maldonado PE. The Energy Homeostasis Principle: Neuronal Energy Regulation Drives Local Network Dynamics Generating Behavior. Front Comput Neurosci. 2019 Jul 23;13:49. https://doi.org/10.3389/fncom.2019.00049. Erratum in: Front Comput Neurosci. 2020 Oct 29;14:599670. PMID: 31396067; PMCID: PMC6664078.

- Brand MD, Nicholls DG. Assessing mitochondrial dysfunction in cells. Biochem J. 2011 Apr 15;435, 297-312. https://doi.org/10.1042/BJ20110162. Erratum in: Biochem J. 2011 Aug 1;437, 575. PMID: 21726199; PMCID: PMC3076726.

- Akbar M, Essa MM, Daradkeh G, Abdelmegeed MA, Choi Y, Mahmood L, Song BJ. Mitochondrial dysfunction and cell death in neurodegenerative diseases through nitroxidative stress. Brain Res. 2016 Apr 15;1637:34-55. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.brainres.2016.02.016. Epub 2016 Feb 13. PMID: 26883165; PMCID: PMC4821765.

- Jellinger KA. Basic mechanisms of neurodegeneration: a critical update. J Cell Mol Med. 2010 Mar;14, 457-87. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1582-4934.2010.01010.x. Epub 2010 Jan 11. PMID: 20070435; PMCID: PMC3823450.

- Osellame, L.D.; Blacker, T.S.; Duchen, M.R. Cellular and molecular mechanisms of mitochondrial function. Best Pract. Res. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 2012, 26, 711–723. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Murali Mahadevan, H.; Hashemiaghdam, A.; Ashrafi, G.; Harbauer, A.B. Mitochondria in neuronal health: from energy metabolism to parkinson’s disease. Advanced Biology 2021, 5, e2100663. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhao, R.-Z.; Jiang, S.; Zhang, L.; Yu, Z.-B. Mitochondrial electron transport chain, ROS generation and uncoupling (Review). Int. J. Mol. Med. 2019, 44, 3–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nolfi-Donegan, D.; Braganza, A.; Shiva, S. Mitochondrial electron transport chain: Oxidative phosphorylation, oxidant production, and methods of measurement. Redox Biol. 2020, 37, 101674. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Trigo, D.; Avelar, C.; Fernandes, M.; Sá, J.; da Cruz E Silva, O. Mitochondria, energy, and metabolism in neuronal health and disease. FEBS Lett. 2022, 596, 1095–1110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McBride, H.M.; Neuspiel, M.; Wasiak, S. Mitochondria: more than just a powerhouse. Curr. Biol. 2006, 16, R551-60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giorgi, C.; Agnoletto, C.; Bononi, A.; Bonora, M.; De Marchi, E.; Marchi, S.; Missiroli, S.; Patergnani, S.; Poletti, F.; Rimessi, A.; Suski, J.M.; Wieckowski, M.R.; Pinton, P. Mitochondrial calcium homeostasis as potential target for mitochondrial medicine. Mitochondrion 2012, 12, 77–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pathak, T.; Trebak, M. Mitochondrial Ca2+ signaling. Pharmacol. Ther. 2018, 192, 112–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shoshan-Barmatz, V.; De Pinto, V.; Zweckstetter, M.; Raviv, Z.; Keinan, N.; Arbel, N. VDAC, a multi-functional mitochondrial protein regulating cell life and death. Mol. Aspects Med. 2010, 31, 227–285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rostovtseva, T.K.; Bezrukov, S.M.; Hoogerheide, D.P. Regulation of Mitochondrial Respiration by VDAC Is Enhanced by Membrane-Bound Inhibitors with Disordered Polyanionic C-Terminal Domains. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021, 22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jung, H.; Kim, S.Y.; Canbakis Cecen, F.S.; Cho, Y.; Kwon, S.-K. Dysfunction of mitochondrial ca2+ regulatory machineries in brain aging and neurodegenerative diseases. Front. Cell Dev. Biol. 2020, 8, 599792. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sparagna, G.C.; Gunter, K.K.; Gunter, T.E. A system for producing and monitoring in vitro calcium pulses similar to those observed in vivo. Anal. Biochem. 1994, 219, 96–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sparagna, G.C.; Gunter, K.K.; Sheu, S.S.; Gunter, T.E. Mitochondrial calcium uptake from physiological-type pulses of calcium. A description of the rapid uptake mode. J. Biol. Chem. 1995, 270, 27510–27515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Grienberger, C.; Konnerth, A. Imaging calcium in neurons. Neuron 2012, 73, 862–885. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petersen, O.H. Calcium signal compartmentalization. Biol. Res. 2002, 35, 177–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laude, A.J.; Simpson, A.W.M. Compartmentalized signalling: Ca2+ compartments, microdomains and the many facets of Ca2+ signalling. FEBS J. 2009, 276, 1800–1816. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Panda, S.; Behera, S.; Alam, M.F.; Syed, G.H. Endoplasmic reticulum & mitochondrial calcium homeostasis: The interplay with viruses. Mitochondrion 2021, 58, 227–242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hirabayashi, Y.; Kwon, S.-K.; Paek, H.; Pernice, W.M.; Paul, M.A.; Lee, J.; Erfani, P.; Raczkowski, A.; Petrey, D.S.; Pon, L.A.; Polleux, F. ER-mitochondria tethering by PDZD8 regulates Ca2+ dynamics in mammalian neurons. Science 2017, 358, 623–630. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ashrafi, G.; de Juan-Sanz, J.; Farrell, R.J.; Ryan, T.A. Molecular tuning of the axonal mitochondrial ca2+ uniporter ensures metabolic flexibility of neurotransmission. Neuron 2020, 105, 678–687.e5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ryan, K.C.; Ashkavand, Z.; Norman, K.R. The role of mitochondrial calcium homeostasis in alzheimer’s and related diseases. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2020, 21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Görlach, A.; Bertram, K.; Hudecova, S.; Krizanova, O. Calcium and ROS: A mutual interplay. Redox Biol. 2015, 6, 260–271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kuznetsov, A.V.; Margreiter, R.; Ausserlechner, M.J.; Hagenbuchner, J. The Complex Interplay between Mitochondria, ROS and Entire Cellular Metabolism. Antioxidants (Basel) 2022, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Angelova, P.R.; Abramov, A.Y. Functional role of mitochondrial reactive oxygen species in physiology. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 2016, 100, 81–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Angelova, P.R. Sources and triggers of oxidative damage in neurodegeneration. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 2021, 173, 52–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tait, S.W.G.; Green, D.R. Mitochondria and cell signalling. J. Cell Sci. 2012, 125, 807–815. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hordijk, P.L. Regulation of NADPH oxidases: the role of Rac proteins. Circ. Res. 2006, 98, 453–462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Angajala, A.; Lim, S.; Phillips, J.B.; Kim, J.-H.; Yates, C.; You, Z.; Tan, M. Diverse Roles of Mitochondria in Immune Responses: Novel Insights Into Immuno-Metabolism. Front. Immunol. 2018, 9, 1605. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pearce, E.L.; Pearce, E.J. Metabolic pathways in immune cell activation and quiescence. Immunity 2013, 38, 633–643. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Breda, C.N. de S.; Davanzo, G.G.; Basso, P.J.; Saraiva Câmara, N.O.; Moraes-Vieira, P.M.M. Mitochondria as central hub of the immune system. Redox Biol. 2019, 26, 101255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.; Zhou, Z.; Min, W. Mitochondria, oxidative stress and innate immunity. Front. Physiol. 2018, 9, 1487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chu, X.; Wu, S.; Raju, R. NLRX1 regulation following acute mitochondrial injury. Front. Immunol. 2019, 10, 2431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stokman, G.; Kors, L.; Bakker, P.J.; Rampanelli, E.; Claessen, N.; Teske, G.J.D.; Butter, L.; van Andel, H.; van den Bergh Weerman, M.A.; Larsen, P.W.B.; Dessing, M.C.; Zuurbier, C.J.; Girardin, S.E.; Florquin, S.; Leemans, J.C. NLRX1 dampens oxidative stress and apoptosis in tissue injury via control of mitochondrial activity. J. Exp. Med. 2017, 214, 2405–2420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, Q.; Zhang, D.; Hu, D.; Zhou, X.; Zhou, Y. The role of mitochondria in NLRP3 inflammasome activation. Mol. Immunol. 2018, 103, 115–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lamkanfi, M.; Kanneganti, T.-D. Nlrp3: an immune sensor of cellular stress and infection. Int. J. Biochem. Cell Biol. 2010, 42, 792–795. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- He, Y.; Hara, H.; Núñez, G. Mechanism and regulation of NLRP3 inflammasome activation. Trends Biochem. Sci. 2016, 41, 1012–1021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guo, C.; Sun, L.; Chen, X.; Zhang, D. Oxidative stress, mitochondrial damage and neurodegenerative diseases. Neural Regen. Res. 2013, 8, 2003–2014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Singh, A.; Kukreti, R.; Saso, L.; Kukreti, S. Oxidative stress: A key modulator in neurodegenerative diseases. Molecules 2019, 24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Behrouzi, A.; Kelley, M.R.; Fehrenbacher, J.C. Oxidative DNA damage: A role in altering neuronal function. J. Cell Signal. 2022, 3, 160–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Poljsak, B.; Šuput, D.; Milisav, I. Achieving the balance between ROS and antioxidants: when to use the synthetic antioxidants. Oxid. Med. Cell. Longev. 2013, 2013, 956792. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, Q. Role of nrf2 in oxidative stress and toxicity. Annu. Rev. Pharmacol. Toxicol. 2013, 53, 401–426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dinkova-Kostova, A.T.; Kostov, R.V.; Kazantsev, A.G. The role of Nrf2 signaling in counteracting neurodegenerative diseases. FEBS J. 2018, 285, 3576–3590. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Thomas, R.L.; Gustafsson, A.B. Mitochondrial autophagy--an essential quality control mechanism for myocardial homeostasis. Circ. J. 2013, 77, 2449–2454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pattingre, S.; Tassa, A.; Qu, X.; Garuti, R.; Liang, X.H.; Mizushima, N.; Packer, M.; Schneider, M.D.; Levine, B. Bcl-2 antiapoptotic proteins inhibit Beclin 1-dependent autophagy. Cell 2005, 122, 927–939. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Narendra, D.P.; Jin, S.M.; Tanaka, A.; Suen, D.-F.; Gautier, C.A.; Shen, J.; Cookson, M.R.; Youle, R.J. PINK1 is selectively stabilized on impaired mitochondria to activate Parkin. PLoS Biol. 2010, 8, e1000298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Elmore, S. Apoptosis: a review of programmed cell death. Toxicol. Pathol. 2007, 35, 495–516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Suen, D.-F.; Norris, K.L.; Youle, R.J. Mitochondrial dynamics and apoptosis. Genes Dev. 2008, 22, 1577–1590. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, C.; Youle, R.J. The role of mitochondria in apoptosis*. Annu. Rev. Genet. 2009, 43, 95–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sheng, Z.-H. The interplay of axonal energy homeostasis and mitochondrial trafficking and anchoring. Trends Cell Biol. 2017, 27, 403–416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Seager, R.; Lee, L.; Henley, J.M.; Wilkinson, K.A. Mechanisms and roles of mitochondrial localisation and dynamics in neuronal function. Neuronal Signal. 2020, 4, NS20200008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vos, M.; Lauwers, E.; Verstreken, P. Synaptic mitochondria in synaptic transmission and organization of vesicle pools in health and disease. Front. Synaptic Neurosci. 2010, 2, 139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chanaday, N.L.; Cousin, M.A.; Milosevic, I.; Watanabe, S.; Morgan, J.R. The Synaptic Vesicle Cycle Revisited: New Insights into the Modes and Mechanisms. J. Neurosci. 2019, 39, 8209–8216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Datta, S.; Jaiswal, M. Mitochondrial calcium at the synapse. Mitochondrion 2021, 59, 135–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Orth M, Schapira AH. Mitochondria and degenerative disorders. Am J Med Genet. 2001 Spring;106, 27-36. https://doi.org/10.1002/ajmg.1425. PMID: 11579422.

- Liesa M, Shirihai OS. Mitochondrial dynamics in the regulation of nutrient utilization and energy expenditure. Cell Metab. 2013 Apr 2;17, 491-506. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cmet.2013.03.002. PMID: 23562075; PMCID: PMC5967396.

- Zhang PN, Zhou MQ, Guo J, Zheng HJ, Tang J, Zhang C, Liu YN, Liu WJ, Wang YX. Mitochondrial Dysfunction and Diabetic Nephropathy: Nontraditional Therapeutic Opportunities. J Diabetes Res. 2021 Dec 9;2021:1010268. https://doi.org/10.1155/2021/1010268. PMID: 34926696; PMCID: PMC8677373.

- Molina AJ, Wikstrom JD, Stiles L, Las G, Mohamed H, Elorza A, Walzer G, Twig G, Katz S, Corkey BE, Shirihai OS. Mitochondrial networking protects beta-cells from nutrient-induced apoptosis. Diabetes. 2009;58:2303–2315.

- Gomes LC, Di BG, Scorrano L. During autophagy mitochondria elongate, are spared from degradation and sustain cell viability. Nat Cell Biol. 2011;13:589–598.

- Lewin R. Trail of ironies to Parkinson's disease. Science. 1984 Jun 8;224, 1083-5. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.6426059. PMID: 6426059.

- Hauser DN, Hastings TG. Mitochondrial dysfunction and oxidative stress in Parkinson’s disease and monogenic parkinsonism. Neurobiol Dis. 2013;51:35–42.

- Surmeier, D. J., Obeso, J. A. & Halliday, G. M. Selective neuronal vulnerability in Parkinson disease. Nat. Rev. Neurosci. 18, 101–113 (2017).

- Park JS, Davis RL, Sue CM. Mitochondrial Dysfunction in Parkinson's Disease: New Mechanistic Insights and Therapeutic Perspectives. Curr Neurol Neurosci Rep. 2018 Apr 3;18, 21. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11910-018-0829-3. PMID: 29616350; PMCID: PMC5882770.

- Magalhães JD, Cardoso SM. Mitochondrial signaling on innate immunity activation in Parkinson disease. Curr Opin Neurobiol. 2022 Dec 16;78:102664. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.conb.2022.102664. Epub ahead of print. PMID: 36535149.

- Rossi A, Pizzo P. Mitochondrial bioenergetics and neurodegeneration: a paso doble. Neural Regen Res. 2021 Apr;16, 686-687. https://doi.org/10.4103/1673-5374.295331. PMID: 33063726; PMCID: PMC8067919.

- Zhang C, Chen S, Li X, Xu Q, Lin Y, Lin F, Yuan M, Zi Y, Cai J. Progress in Parkinson's disease animal models of genetic defects: Characteristics and application. Biomed Pharmacother. 2022 Nov;155:113768. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.biopha.2022.113768. Epub 2022 Sep 28. PMID: 36182736.

- Valente EM, Abou-Sleiman PM, Caputo V, et al. Hereditary early-onset Parkinson's disease caused by mutations in PINK1. Science 2004; 304: 1158– 1160.

- Arena G, Valente EM. PINK1 in the limelight: multiple functions of an eclectic protein in human health and disease. J Pathol. 2017 Jan;241, 251-263. https://doi.org/10.1002/path.4815. Epub 2016 Nov 12. PMID: 27701735.

- Silvestri L, Caputo V, Bellacchio E, et al. Mitochondrial import and enzymatic activity of PINK1 mutants associated to recessive parkinsonism. Hum Mol Genet 2005; 14: 3477– 3492.

- Unoki M, Nakamura Y. Growth-suppressive effects of BPOZ and EGR2, two genes involved in the PTEN signaling pathway. Oncogene 2001; 20: 4457–4465.

- Garber K. Parkinson's disease and cancer: the unexplored connection. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2010 Mar 17;102, 371-4. https://doi.org/10.1093/jnci/djq081. Epub 2010 Mar 9. PMID: 20215596.

- Masgras I, Laquatra C, Cannino G, Serapian SA, Colombo G, Rasola A. The molecular chaperone TRAP1 in cancer: From the basics of biology to pharmacological targeting. Semin Cancer Biol. 2021 Nov;76:45-53. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.semcancer.2021.07.002. Epub 2021 Jul 6. PMID: 34242740.

- Exner N, Treske B, Paquet D, Holmström K, Schiesling C, Gispert S, Carballo-Carbajal I, Berg D, Hoepken HH, Gasser T, Krüger R, Winklhofer KF, Vogel F, Reichert AS, Auburger G, Kahle PJ, Schmid B, Haass C. Loss-of-function of human PINK1 results in mitochondrial pathology and can be rescued by parkin. J Neurosci. 2007 Nov 7;27, 12413-8. https://doi.org/10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0719-07.2007. PMID: 17989306; PMCID: PMC6673250.

- Kitada T, Pisani A, Porter DR, Yamaguchi H, Tscherter A, Martella G, Bonsi P, Zhang C, Pothos EN, Shen J. Impaired dopamine release and synaptic plasticity in the striatum of PINK1-deficient mice. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2007 Jul 3;104, 11441-6. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.0702717104. Epub 2007 Jun 11. PMID: 17563363; PMCID: PMC1890561.

- Martella G, Madeo G, Maltese M, Vanni V, Puglisi F, Ferraro E, Schirinzi T, Valente EM, Bonanni L, Shen J, Mandolesi G, Mercuri NB, Bonsi P, Pisani A. Exposure to low-dose rotenone precipitates synaptic plasticity alterations in PINK1 heterozygous knockout mice. Neurobiol Dis. 2016 Jul;91:21-36. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.nbd.2015.12.020. Epub 2016 Feb 23. PMID: 26916954.

- Imbriani P, Tassone A, Meringolo M, Ponterio G, Madeo G, Pisani A, Bonsi P, Martella G. Loss of Non-Apoptotic Role of Caspase-3 in the PINK1 Mouse Model of Parkinson's Disease. Int J Mol Sci. 2019 Jul 11;20, 3407. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms20143407. PMID: 31336695; PMCID: PMC6678522.

- Imbriani P, D'Angelo V, Platania P, Di Lazzaro G, Scalise S, Salimei C, El Atiallah I, Colona VL, Mercuri NB, Bonsi P, Pisani A, Schirinzi T, Martella G. Ischemic injury precipitates neuronal vulnerability in Parkinson's disease: Insights from PINK1 mouse model study and clinical retrospective data. Parkinsonism Relat Disord. 2020 May;74:57-63. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.parkreldis.2020.04.004. Epub 2020 Apr 20. PMID: 32335490.

- Brunelli F, Valente EM, Arena G. Mechanisms of neurodegeneration in Parkinson's disease: keep neurons in the PINK1. Mech Ageing Dev. 2020 Jul;189:111277. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.mad.2020.111277. Epub 2020 Jun 3. PMID: 32504621.

- Zhi L, Qin Q, Muqeem T, Seifert EL, Liu W, Zheng S, Li C, Zhang H. Loss of PINK1 causes age-dependent decrease of dopamine release and mitochondrial dysfunction. Neurobiol Aging. 2019 Mar;75:1-10. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neurobiolaging.2018.10.025. Epub 2018 Nov 2. PMID: 30504091; PMCID: PMC6778692.

- Onyango IG, Bennett JP, Stokin GB. Regulation of neuronal bioenergetics as a therapeutic strategy in neurodegenerative diseases. Neural Regen Res. 2021 Aug;16, 1467-1482. https://doi.org/10.4103/1673-5374.303007. PMID: 33433460; PMCID: PMC8323696.

- Khalil B, El Fissi N, Aouane A, et al. PINK1-induced mitophagy promotes neuroprotection in Huntington's disease. Cell Death Dis 2015; 6: e1617.

- Anderson KE, Marshall FJ. Behavioral symptoms associated with Huntington's disease. Adv Neurol. 2005;96:197-208. PMID: 16383221.

- Caron NS, Wright GEB, Hayden MR. Huntington Disease. 1998 Oct 23 [updated 2020 Jun 11]. In: Adam MP, Everman DB, Mirzaa GM, Pagon RA, Wallace SE, Bean LJH, Gripp KW, Amemiya A, editors. GeneReviews® [Internet]. Seattle (WA): University of Washington, Seattle; 1993–2023. PMID: 20301482.

- Damiano M, Galvan L, Déglon N, Brouillet E. Mitochondria in Huntington's disease. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2010 Jan;1802, 52-61. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bbadis.2009.07.012. Epub 2009 Aug 11. PMID: 19682570.

- Rehman MU, Sehar N, Dar NJ, Khan A, Arafah A, Rashid S, Rashid SM, Ganaie MA. Mitochondrial dysfunctions, oxidative stress and neuroinflammation as therapeutic targets for neurodegenerative diseases: An update on current advances and impediments. Neurosci Biobehav Rev. 2023 Jan;144:104961. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neubiorev.2022.104961. Epub 2022 Nov 14. PMID: 36395982.

- Jurcau A, Jurcau CM. Mitochondria in Huntington's disease: implications in pathogenesis and mitochondrial-targeted therapeutic strategies. Neural Regen Res. 2023 Jul;18, 1472-1477. https://doi.org/10.4103/1673-5374.360289. PMID: 36571344.

- Kawsar, M., Taz, T.A., Paul, B.K. et al. Identification of vital regulatory genes with network pathways among Huntington’s, Parkinson’s, and Alzheimer’s diseases. Netw Model Anal Health Inform Bioinforma 9, 50 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1007/s13721-020-00257-4.

- Li Z, Zhang Z, Ren Y, Wang Y, Fang J, Yue H, Ma S, Guan F. Aging and age-related diseases: from mechanisms to therapeutic strategies. Biogerontology. 2021 Apr;22, 165-187. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10522-021-09910-5. Epub 2021 Jan 27. PMID: 33502634; PMCID: PMC7838467.

- Quijano C, Cao L, Fergusson MM, Romero H, Liu J, Gutkind S, Rovira II, Mohney RP, Karoly ED, Finkel T. Oncogene-induced senescence results in marked metabolic and bioenergetic alterations. Cell Cycle. 2012;11:1383–1392.

- Sun N, Youle RJ, Finkel T. The Mitochondrial Basis of Aging. Mol Cell. 2016 Mar 3;61, 654-666. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.molcel.2016.01.028. PMID: 26942670; PMCID: PMC4779179.

- Moro L. Mitochondrial Dysfunction in Aging and Cancer. J Clin Med. 2019 Nov 15;8, 1983. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm8111983. PMID: 31731601; PMCID: PMC6912717.

- Boland ML, Chourasia AH, Macleod KF. Mitochondrial dysfunction in cancer. Front Oncol. 2013 Dec 2;3:292. https://doi.org/10.3389/fonc.2013.00292. PMID: 24350057; PMCID: PMC3844930.

- Wang XL, Feng ST, Wang YT, Yuan YH, Li ZP, Chen NH, Wang ZZ, Zhang Y. Mitophagy, a Form of Selective Autophagy, Plays an Essential Role in Mitochondrial Dynamics of Parkinson's Disease. Cell Mol Neurobiol. 2022 Jul;42, 1321-1339. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10571-021-01039-w. Epub 2021 Feb 2. PMID: 33528716.

- Ryan BJ, Hoek S, Fon EA, Wade-Martins R. Mitochondrial dysfunction and mitophagy in Parkinson's: from familial to sporadic disease. Trends Biochem Sci. 2015 Apr;40, 200-10. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tibs.2015.02.003. Epub 2015 Mar 8. PMID: 25757399.

- Büeler H. Impaired mitochondrial dynamics and function in the pathogenesis of Parkinson's disease. Exp Neurol. 2009 Aug;218, 235-46. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.expneurol.2009.03.006. Epub 2009 Mar 18. PMID: 19303005.

- Chen C, Turnbull DM, Reeve AK. Mitochondrial Dysfunction in Parkinson's Disease-Cause or Consequence? Biology (Basel). 2019 May 11;8, 38. https://doi.org/10.3390/biology8020038. PMID: 31083583; PMCID: PMC6627981.

- Parker WD Jr, Boyson SJ, Parks JK. Abnormalities of the electron transport chain in idiopathic Parkinson's disease. Ann Neurol. 1989 Dec;26, 719-23. https://doi.org/10.1002/ana.410260606. PMID: 2557792.

- Rekha KR, Selvakumar GP. Gene expression regulation of Bcl2, Bax and cytochrome-C by geraniol on chronic MPTP/probenecid induced C57BL/6 mice model of Parkinson's disease. Chem Biol Interact. 2014 Jun 25;217:57-66. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cbi.2014.04.010. Epub 2014 Apr 24. PMID: 24768735.

- Lee JH, Han JH, Kim H, Park SM, Joe EH, Jou I. Parkinson's disease-associated LRRK2- G2019S mutant acts through regulation of SERCA activity to control ER stress in astrocytes. Acta Neuropathol Commun. 2019 May 2;7, 68. https://doi.org/10.1186/s40478-019- 0716-4. PMID: 31046837; PMCID: PMC6498585.

- Exner N, Lutz AK, Haass C, Winklhofer KF. Mitochondrial dysfunction in Parkinson's disease: molecular mechanisms and pathophysiological consequences. EMBO J. 2012 Jun 26;31, 3038-62. https://doi.org/10.1038/emboj.2012.170. PMID: 22735187; PMCID: PMC3400019.

- Meredith GE, Rademacher DJ. MPTP mouse models of Parkinson's disease: an update. J Parkinsons Dis. 2011;1, 19-33. https://doi.org/10.3233/JPD-2011-11023. PMID: 23275799; PMCID: PMC3530193.

- Zeng XS, Geng WS, Jia JJ. Neurotoxin-Induced Animal Models of Parkinson Disease: Pathogenic Mechanism and Assessment. ASN Neuro. 2018 Jan- Dec;10:1759091418777438. https://doi.org/10.1177/1759091418777438. PMID: 29809058; PMCID: PMC5977437.

- Imbriani P, Schirinzi T, Meringolo M, Mercuri NB, Pisani A. Centrality of Early Synaptopathy in Parkinson's Disease. Front Neurol. 2018 Mar 1;9:103. https://doi.org/10.3389/fneur.2018.00103. PMID: 29545770; PMCID: PMC5837972.

- Imbriani P, Sciamanna G, Santoro M, Schirinzi T, Pisani A. Promising rodent models in Parkinson's disease. Parkinsonism Relat Disord. 2018b Jan;46 Suppl 1:S10-S14. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.parkreldis.2017.07.027. Epub 2017 Jul 27. PMID: 28760592.

- Innos J, Hickey MA. Using Rotenone to Model Parkinson's Disease in Mice: A Review of the Role of Pharmacokinetics. Chem Res Toxicol. 2021 May 17;34, 1223-1239. https://doi.org/10.1021/acs.chemrestox.0c00522. Epub 2021 May 7. PMID: 33961406.

- Imbriani P, Martella G, Bonsi P, Pisani A. Oxidative stress and synaptic dysfunction in rodent models of Parkinson's disease. Neurobiol Dis. 2022 Oct 15;173:105851. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.nbd.2022.105851. Epub 2022 Aug 23. PMID: 36007757.

- McLean PJ, Ribich S, Hyman BT. Subcellular localization of alpha-synuclein in primary neuronal cultures: effect of missense mutations. J Neural Transm Suppl. 2000;(58):53-63. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-7091-6284-2_5. PMID: 11128613.

- Zhang L, Zhang C, Zhu Y, Cai Q, Chan P, Uéda K, Yu S, Yang H. Semi-quantitative analysis of alpha-synuclein in subcellular pools of rat brain neurons: an immunogold electron microscopic study using a C-terminal specific monoclonal antibody. Brain Res. 2008 Dec 9;1244:40-52. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.brainres.2008.08.067. Epub 2008 Sep 4. PMID: 18817762.

- Cole NB, Dieuliis D, Leo P, Mitchell DC, Nussbaum RL. Mitochondrial translocation of alpha-synuclein is promoted by intracellular acidification. Exp Cell Res. 2008 Jun 10;314, 2076-89. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.yexcr.2008.03.012. Epub 2008 Mar 28. PMID: 18440504; PMCID: PMC2483835.

- Polymeropoulos MH, Higgins JJ, Golbe LI, Johnson WG, Ide SE, Di Iorio G, Sanges G, Stenroos ES, Pho LT, Schaffer AA, Lazzarini AM, Nussbaum RL, Duvoisin RC. Mapping of a gene for Parkinson's disease to chromosome 4q21-q23. Science. 1996 Nov 15;274, 1197-9. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.274.5290.1197. PMID: 8895469.

- Koprich JB, Kalia LV, Brotchie JM. Animal models of α-synucleinopathy for Parkinson disease drug development. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2017 Sep;18, 515-529. https://doi.org/10.1038/nrn.2017.75. Epub 2017 Jul 13. PMID: 28747776.

- Ingelsson M. Alpha-Synuclein Oligomers-Neurotoxic Molecules in Parkinson's Disease and Other Lewy Body Disorders. Front Neurosci. 2016 Sep 5;10:408. https://doi.org/10.3389/fnins.2016.00408. PMID: 27656123; PMCID: PMC5011129.

- Martin LJ, Pan Y, Price AC, Sterling W, Copeland NG, Jenkins NA, Price DL, Lee MK. Parkinson's disease alpha-synuclein transgenic mice develop neuronal mitochondrial degeneration and cell death. J Neurosci. 2006 Jan 4;26, 41-50. https://doi.org/10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4308-05.2006. PMID: 16399671; PMCID: PMC6381830.

- Portz P, Lee MK. Changes in Drp1 Function and Mitochondrial Morphology Are Associated with the α-Synuclein Pathology in a Transgenic Mouse Model of Parkinson's Disease. Cells. 2021 Apr 13;10, 885. https://doi.org/10.3390/cells10040885. PMID: 33924585; PMCID: PMC8070398.

- Xie W, Chung KK. Alpha-synuclein impairs normal dynamics of mitochondria in cell and animal models of Parkinson's disease. J Neurochem. 2012 Jul;122, 404-14. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1471-4159.2012.07769.x. Epub 2012 May 23. PMID: 22537068.

- Chinta SJ, Mallajosyula JK, Rane A, Andersen JK. Mitochondrial α-synuclein accumulation impairs complex I function in dopaminergic neurons and results in increased mitophagy in vivo. Neurosci Lett. 2010 Dec 17;486, 235-9. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neulet.2010.09.061. Epub 2010 Sep 29. PMID: 20887775; PMCID: PMC2967673.

- Merino-Galán L, Jimenez-Urbieta H, Zamarbide M, Rodríguez-Chinchilla T, Belloso- Iguerategui A, Santamaria E, Fernández-Irigoyen J, Aiastui A, Doudnikoff E, Bézard E, Ouro A, Knafo S, Gago B, Quiroga-Varela A, Rodríguez-Oroz MC. Striatal synaptic bioenergetic and autophagic decline in premotor experimental Parkinsonism. Brain. 2022 Jun 30;145, 2092-2107. https://doi.org/10.1093/brain/awac087. PMID: 35245368; PMCID: PMC9460676.

- Anandhan A, Jacome MS, Lei S, Hernandez-Franco P, Pappa A, Panayiotidis MI, Powers R, Franco R. Metabolic Dysfunction in Parkinson's Disease: Bioenergetics, Redox Homeostasis and Central Carbon Metabolism. Brain Res Bull. 2017 Jul;133:12-30. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.brainresbull.2017.03.009. Epub 2017 Mar 21. PMID: 28341600; PMCID: PMC5555796.

- Kurz A, Double KL, Lastres-Becker I, Tozzi A, Tantucci M, Bockhart V, Bonin M, García- Arencibia M, Nuber S, Schlaudraff F, Liss B, Fernández-Ruiz J, Gerlach M, Wüllner U, Lüddens H, Calabresi P, Auburger G, Gispert S. A53T-alpha-synuclein overexpression impairs dopamine signaling and striatal synaptic plasticity in old mice. PLoS One. 2010 Jul 7;5, e11464. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0011464. PMID: 20628651; PMCID: PMC2898885.

- Durante V, de Iure A, Loffredo V, Vaikath N, De Risi M, Paciotti S, Quiroga-Varela A, Chiasserini D, Mellone M, Mazzocchetti P, Calabrese V, Campanelli F, Mechelli A, Di Filippo M, Ghiglieri V, Picconi B, El-Agnaf OM, De Leonibus E, Gardoni F, Tozzi A, Calabresi P. Alpha-synuclein targets GluN2A NMDA receptor subunit causing striatal synaptic dysfunction and visuospatial memory alteration. Brain. 2019 May 1;142, 1365- 1385. https://doi.org/10.1093/brain/awz065. PMID: 30927362.

- Tozzi A, de Iure A, Bagetta V, Tantucci M, Durante V, Quiroga-Varela A, Costa C, Di Filippo M, Ghiglieri V, Latagliata EC, Wegrzynowicz M, Decressac M, Giampà C, Dalley JW, Xia J, Gardoni F, Mellone M, El-Agnaf OM, Ardah MT, Puglisi-Allegra S, Björklund A, Spillantini MG, Picconi B, Calabresi P. Alpha-Synuclein Produces Early Behavioral Alterations via Striatal Cholinergic Synaptic Dysfunction by Interacting With GluN2D N-Methyl-D-Aspartate Receptor Subunit. Biol Psychiatry. 2016 Mar 1;79, 402-414. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.biopsych.2015.08.013. Epub 2015 Aug 20. PMID: 26392130.

- Tozzi A, Sciaccaluga M, Loffredo V, Megaro A, Ledonne A, Cardinale A, Federici M, Bellingacci L, Paciotti S, Ferrari E, La Rocca A, Martini A, Mercuri NB, Gardoni F, Picconi B, Ghiglieri V, De Leonibus E, Calabresi P. Dopamine-dependent early synaptic and motor dysfunctions induced by α-synuclein in the nigrostriatal circuit. Brain. 2021 Dec 16;144, 3477-3491. https://doi.org/10.1093/brain/awab242. PMID: 34297092; PMCID: PMC8677552.

- Calì T, Ottolini D, Negro A, Brini M. α-Synuclein controls mitochondrial calcium homeostasis by enhancing endoplasmic reticulum-mitochondria interactions. J Biol Chem. 2012 May 25;287, 17914-29. https://doi.org/10.1074/jbc.M111.302794. Epub 2012 Mar 27. PMID: 22453917; PMCID: PMC3365710.

- Alves Da Costa C, Paitel E, Vincent B, Checler F. Alpha-synuclein lowers p53-dependent apoptotic response of neuronal cells. Abolishment by 6-hydroxydopamine and implication for Parkinson's disease. J Biol Chem. 2002 Dec 27;277, 50980-4. https://doi.org/10.1074/jbc.M207825200. Epub 2002 Oct 22. PMID: 12397073.

- Chan SL, Mattson MP. Caspase and calpain substrates: roles in synaptic plasticity and cell death. J Neurosci Res. 1999 Oct 1;58, 167-90. PMID: 10491581.

- D’Amelio M, Cavallucci V, Cecconi F. Neuronal caspase-3 signaling: not only cell death. Cell Death Differ. 2010 Jul;17, 1104-14. https://doi.org/10.1038/cdd.2009.180. Epub 2009 Dec 4. PMID: 19960023.

- Snigdha S, Smith ED, Prieto GA, Cotman CW. Caspase-3 activation as a bifurcation point between plasticity and cell death. Neurosci Bull. 2012 Feb;28, 14-24. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12264-012-1057-5. PMID: 22233886; PMCID: PMC3838299.

- Bonifati V, Rizzu P, van Baren MJ, Schaap O, Breedveld GJ, Krieger E, Dekker MC, Squitieri F, Ibanez P, Joosse M, van Dongen JW, Vanacore N, van Swieten JC, Brice A, Meco G, van Duijn CM, Oostra BA, Heutink P. Mutations in the DJ-1 gene associated with autosomal recessive early-onset Parkinsonism. Science. 2003 Jan 10;299, 256-9. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.1077209. Epub 2002 Nov 21. PMID: 12446870.

- Thomas KJ, McCoy MK, Blackinton J, Beilina A, van der Brug M, Sandebring A, Miller D, Maric D, Cedazo-Minguez A, Cookson MR. DJ-1 acts in parallel to the PINK1/Parkin pathway to control mitochondrial function and autophagy. Hum Mol Genet. 2011 Jan 1;20, 40-50. https://doi.org/10.1093/hmg/ddq430. Epub 2010 Oct 11. PMID: 20940149; PMCID: PMC3000675.

- Trancikova A, Tsika E, Moore DJ. Mitochondrial dysfunction in genetic animal models of Parkinson's disease. Antioxid Redox Signal. 2012 May 1;16, 896-919. https://doi.org/10.1089/ars.2011.4200. Epub 2011 Oct 4. PMID: 21848447; PMCID: PMC3292748.

- Dzamko N, Zhou J, Huang Y, Halliday GM. Parkinson's disease-implicated kinases in the brain; insights into disease pathogenesis. Front Mol Neurosci. 2014 Jun 24;7:57. https://doi.org/10.3389/fnmol.2014.00057. PMID: 25009465; PMCID: PMC4068290.

- Du F, Yu Q, Yan S, Hu G, Lue LF, Walker DG, Wu L, Yan SF, Tieu K, Yan SS. PINK1 signalling rescues amyloid pathology and mitochondrial dysfunction in Alzheimer's disease. Brain. 2017 Dec 1;140, 3233-3251. https://doi.org/10.1093/brain/awx258. PMID: 29077793; PMCID: PMC5841141.

- Lazarou M, Sliter DA, Kane LA, Sarraf SA, Wang C, Burman JL, Sideris DP, Fogel AI, Youle RJ. The ubiquitin kinase PINK1 recruits autophagy receptors to induce mitophagy. Nature. 2015 Aug 20;524, 309-314. https://doi.org/10.1038/nature14893. Epub 2015 Aug 12. PMID: 26266977; PMCID: PMC5018156.

- Lücking CB, Dürr A, Bonifati V, Vaughan J, De Michele G, Gasser T, Harhangi BS, Meco G, Denèfle P, Wood NW, Agid Y, Brice A; French Parkinson's Disease Genetics Study Group; European Consortium on Genetic Susceptibility in Parkinson's Disease. Association between early-onset Parkinson's disease and mutations in the Parkin gene. N Engl J Med. 2000 May 25;342, 1560-7. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJM200005253422103. PMID: 10824074.

- Moore DJ. Parkin: a multifaceted ubiquitin ligase. Biochem Soc Trans. 2006 Nov;34(Pt 5):749-53. https://doi.org/10.1042/BST0340749. PMID: 17052189.

- Xiong H, Wang D, Chen L, Choo YS, Ma H, Tang C, Xia K, Jiang W, Ronai Z, Zhuang X, Zhang Z. Parkin, PINK1, and DJ-1 form a ubiquitin E3 ligase complex promoting unfolded protein degradation. J Clin Invest. 2009 Mar;119, 650-60. https://doi.org/10.1172/JCI37617. Epub 2009 Feb 23. PMID: 19229105; PMCID: PMC2648688.

- Periquet M, Corti O, Jacquier S, Brice A. Proteomic analysis of Parkin knockout mice: alterations in energy metabolism, protein handling and synaptic function. J Neurochem. 2005 Dec;95, 1259-76. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1471-4159.2005.03442.x. Epub 2005 Sep 7. PMID: 16150055.

- Darios F, Corti O, Lücking CB, Hampe C, Muriel MP, Abbas N, Gu WJ, Hirsch EC, Rooney T, Ruberg M, Brice A. Parkin prevents mitochondrial swelling and cytochrome c release in mitochondria-dependent cell death. Hum Mol Genet. 2003 Mar 1;12, 517-26. https://doi.org/10.1093/hmg/ddg044. PMID: 12588799.

- Shin JH, Ko HS, Kang H, Lee Y, Lee YI, Pletinkova O, Troconso JC, Dawson VL, Dawson TM. PARIS (ZNF746) repression of PGC-1α contributes to neurodegeneration in Parkinson's disease. Cell. 2011 Mar 4;144, 689-702. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cell.2011.02.010.

- Jo A, Lee Y, Kam TI, Kang SU, Neifert S, Karuppagounder SS, Khang R, Kang H, Park H, Chou SC, Oh S, Jiang H, Swing DA, Ham S, Pirooznia S, Umanah GKE, Mao X, Kumar M, Ko HS, Kang HC, Lee BD, Lee YI, Andrabi SA, Park CH, Lee JY, Kim H, Kim H, Kim H, Cho JW, Paek SH, Na CH, Tessarollo L, Dawson VL, Dawson TM, Shin JH. PARIS farnesylation prevents neurodegeneration in models of Parkinson's disease. Sci Transl Med. 2021 Jul 28;13, eaax8891. https://doi.org/10.1126/scitranslmed.aax8891. PMID: 34321320.

- Narendra D, Tanaka A, Suen DF, Youle RJ. Parkin-induced mitophagy in the pathogenesis of Parkinson disease. Autophagy. 2009 Jul;5, 706-8. https://doi.org/10.4161/auto.5.5.8505. Epub 2009 Jul 22. PMID: 19377297.

- Palacino JJ, Sagi D, Goldberg MS, Krauss S, Motz C, Wacker M, Klose J, Shen J. Mitochondrial dysfunction and oxidative damage in Parkin-deficient mice. J Biol Chem. 2004 Apr 30;279, 18614-22. https://doi.org/10.1074/jbc.M401135200. Epub 2004 Feb 24. PMID: 14985362.

- Goldberg MS, Pisani A, Haburcak M, Vortherms TA, Kitada T, Costa C, Tong Y, Martella G, Tscherter A, Martins A, Bernardi G, Roth BL, Pothos EN, Calabresi P, Shen J. Nigrostriatal dopaminergic deficits and hypokinesia caused by inactivation of the familial Parkinsonism- linked gene DJ-1. Neuron. 2005 Feb 17;45, 489-96. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neuron.2005.01.041. PMID: 15721235.

- Itier JM, Ibanez P, Mena MA, Abbas N, Cohen-Salmon C, Bohme GA, Laville M, Pratt J, Corti O, Pradier L, Ret G, Joubert C, Periquet M, Araujo F, Negroni J, Casarejos MJ, Canals S, Solano R, Serrano A, Gallego E, Sanchez M, Denefle P, Benavides J, Tremp G, Rooney TA, Brice A, Garcia de Yebenes J. Parkin gene inactivation alters behaviour and dopamine neurotransmission in the mouse. Hum Mol Genet. 2003 Sep 15;12, 2277-91. https://doi.org/10.1093/hmg/ddg239. Epub 2003 Jul 22. PMID: 12915482.

- Kitada T, Pisani A, Karouani M, Haburcak M, Martella G, Tscherter A, Platania P, Wu B, Pothos EN, Shen J. Impaired dopamine release and synaptic plasticity in the striatum of parkin-/- mice. J Neurochem. 2009b Jul;110, 613-21. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1471- 4159.2009.06152.x. Epub 2009 May 5. PMID: 19457102.

- Cortese GP, Zhu M, Williams D, Heath S, Waites CL. Parkin Deficiency Reduces Hippocampal Glutamatergic Neurotransmission by Impairing AMPA Receptor Endocytosis. J Neurosci. 2016 Nov 30;36, 12243-12258. https://doi.org/10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1473-16.2016. PMID: 27903732; PMCID: PMC5148221.

- Calì T, Ottolini D, Negro A, Brini M. Enhanced parkin levels favor ER-mitochondria crosstalk and guarantee Ca(2+) transfer to sustain cell bioenergetics. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2013 Apr;1832, 495-508. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bbadis.2013.01.004. Epub 2013 Jan 9. PMID: 23313576.

- Bianchi K, Rimessi A, Prandini A, Szabadkai G, Rizzuto R. Calcium and mitochondria: mechanisms and functions of a troubled relationship. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2004 Dec 6;1742(1-3):119-31. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bbamcr.2004.09.015. PMID: 15590062.

- Vos M, Lauwers E, Verstreken P. Synaptic mitochondria in synaptic transmission and organization of vesicle pools in health and disease. Front Synaptic Neurosci. 2010 Sep 22;2:139. https://doi.org/10.3389/fnsyn.2010.00139. PMID: 21423525; PMCID: PMC3059669.

- Jo D, Song J. Irisin Acts via the PGC-1α and BDNF Pathway to Improve Depression-like Behavior. Clin Nutr Res. 2021 Oct 20;10, 292-302. https://doi.org/10.7762/cnr.2021.10.4.292. PMID: 34796134; PMCID: PMC8575642.

- Zhou H, Falkenburger BH, Schulz JB, Tieu K, Xu Z, Xia XG. Silencing of the Pink1 gene expression by conditional RNAi does not induce dopaminergic neuron death in mice. Int J Biol Sci. 2007 Mar 5;3, 242-50. https://doi.org/10.7150/ijbs.3.242. PMID: 17389931; PMCID: PMC1820878.

- Madeo G, Schirinzi T, Martella G, Latagliata EC, Puglisi F, Shen J, Valente EM, Federici M, Mercuri NB, Puglisi-Allegra S, Bonsi P, Pisani A. PINK1 heterozygous mutations induce subtle alterations in dopamine-dependent synaptic plasticity. Mov Disord. 2014 Jan;29, 41-53. https://doi.org/10.1002/mds.25724. Epub 2013 Oct 25. PMID: 24167038; PMCID: PMC4022284.

- Dave KD, De Silva S, Sheth NP, Ramboz S, Beck MJ, Quang C, Switzer RC 3rd, Ahmad SO, Sunkin SM, Walker D, Cui X, Fisher DA, McCoy AM, Gamber K, Ding X, Goldberg MS, Benkovic SA, Haupt M, Baptista MA, Fiske BK, Sherer TB, Frasier MA. Phenotypic characterization of recessive gene knockout rat models of Parkinson's disease. NeurobiolDis. 2014 Oct;70:190-203. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.nbd.2014.06.009. Epub 2014 Jun 24. PMID:24969022.

- Stauch KL, Villeneuve LM, Purnell PR, Ottemann BM, Emanuel K, Fox HS. Loss of Pink1 modulates synaptic mitochondrial bioenergetics in the rat striatum prior to motor symptoms: concomitant complex I respiratory defects and increased complex II-mediated respiration. Proteomics Clin Appl. 2016 Dec;10, 1205-1217. https://doi.org/10.1002/prca.201600005. Epub 2016 Sep 21. PMID: 27568932; PMCID: PMC5810131.

- Villeneuve LM, Purnell PR, Boska MD, Fox HS. Early Expression of Parkinson's Disease- Related Mitochondrial Abnormalities in PINK1 Knockout Rats. Mol Neurobiol. 2016 Jan;53, 171-186. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12035-014-8927-y. Epub 2014 Nov 25. PMID: 25421206; PMCID: PMC4442772.

- Creed RB, Goldberg MS. Analysis of α-Synuclein Pathology in PINK1 Knockout Rat Brains. Front Neurosci. 2019 Jan 9;12:1034. https://doi.org/10.3389/fnins.2018.01034. PMID: 30686993; PMCID: PMC6333903.

- Li Z, Jo J, Jia JM, Lo SC, Whitcomb DJ, Jiao S, Cho K, Sheng M. Caspase-3 activation via mitochondria is required for long-term depression and AMPA receptor internalization. Cell. 2010 May 28;141, 859-71. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cell.2010.03.053. PMID: 20510932; PMCID: PMC2909748.

- Snigdha S, Smith ED, Prieto GA, Cotman CW. Caspase-3 activation as a bifurcation point between plasticity and cell death. Neurosci Bull. 2012 Feb;28, 14-24. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12264 012-1057-5. PMID: 22233886; PMCID: PMC3838299.

- Gautier CA, Kitada T, Shen J. Loss of PINK1 causes mitochondrial functional defects and increased sensitivity to oxidative stress. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2008 Aug 12;105, 11364-9. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.0802076105. Epub 2008 Aug 7. PMID: 18687901; PMCID: PMC2516271.

- Zhi L, Qin Q, Muqeem T, Seifert EL, Liu W, Zheng S, Li C, Zhang H. Loss of PINK1 causes age-dependent decrease of dopamine release and mitochondrial dysfunction. Neurobiol Aging. 2019 Mar;75:1-10. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neurobiolaging.2018.10.025. Epub 2018 Nov 2. PMID: 30504091; PMCID: PMC6778692.

- Zhang L, Shimoji M, Thomas B, Moore DJ, Yu SW, Marupudi NI, Torp R, Torgner IA, Ottersen OP, Dawson TM, Dawson VL. Mitochondrial localization of the Parkinson's disease related protein DJ-1: implications for pathogenesis. Hum Mol Genet. 2005 Jul 15;14, 2063-73. https://doi.org/10.1093/hmg/ddi211. Epub 2005 Jun 8. PMID: 15944198.

- Guzman JN, Sanchez-Padilla J, Wokosin D, Kondapalli J, Ilijic E, Schumacker PT, Surmeier DJ. Oxidant stress evoked by pacemaking in dopaminergic neurons is attenuated by DJ-1. Nature. 2010 Dec 2;468, 696-700. https://doi.org/10.1038/nature09536. Epub 2010 Nov 10. Erratum in: Nature. 2015 May 21;521, 380. PMID: 21068725; PMCID: PMC4465557.

- Goldberg JA, Guzman JN, Estep CM, Ilijic E, Kondapalli J, Sanchez-Padilla J, Surmeier DJ. Calcium entry induces mitochondrial oxidant stress in vagal neurons at risk in Parkinson's disease. Nat Neurosci. 2012 Oct;15, 1414-21. https://doi.org/10.1038/nn.3209. Epub 2012 Sep 2. PMID: 22941107; PMCID: PMC3461271.

- Andres-Mateos E, Perier C, Zhang L, Blanchard-Fillion B, Greco TM, Thomas B, Ko HS, Sasaki M, Ischiropoulos H, Przedborski S, Dawson TM, Dawson VL. DJ-1 gene deletion reveals that DJ-1 is an atypical peroxiredoxin-like peroxidase. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2007 Sep 11;104, 14807-12. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.0703219104. Epub 2007 Aug 31. PMID: 17766438; PMCID: PMC1976193.

- Lopert P, Patel M. Brain mitochondria from DJ-1 knockout mice show increased respiration- dependent hydrogen peroxide consumption. Redox Biol. 2014 Apr 24;2:667-72. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.redox.2014.04.010. PMID: 24936441; PMCID: PMC4052521.

- Chen W, Liu H, Liu S, Kang Y, Nie Z, Lei H. Altered prefrontal neurochemistry in the DJ-1 knockout mouse model of Parkinson's disease: complementary semi-quantitative analyses with in vivo magnetic resonance spectroscopy and MALDI-MSI. Anal Bioanal Chem. 2022 Nov;414, 7977-7987. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00216-022-04341-8. Epub 2022 Oct 8. PMID: 36208327.

- Dringen R, Hirrlinger J. Glutathione pathways in the brain. Biol Chem. 2003 Apr;384, 505- 16. https://doi.org/10.1515/BC.2003.059. PMID: 12751781.

- Kirkinezos IG, Moraes CT. Reactive oxygen species and mitochondrial diseases. Semin Cell Dev Biol. 2001 Dec;12, 449-57. https://doi.org/10.1006/scdb.2001.0282. PMID: 11735379.

- Dringen R, Gutterer JM, Hirrlinger J. Glutathione metabolism in brain metabolic interaction between astrocytes and neurons in the defense against reactive oxygen species. Eur J Biochem. 2000 Aug;267, 4912-6. https://doi.org/10.1046/j.1432-1327.2000.01597.x. PMID: 10931173.

- Heo JY, Park JH, Kim SJ, Seo KS, Han JS, Lee SH, Kim JM, Park JI, Park SK, Lim K, Hwang BD, Shong M, Kweon GR. DJ-1 null dopaminergic neuronal cells exhibit defects in mitochondrial function and structure: involvement of mitochondrial complex I assembly. PLoS One. 2012;7, e32629. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0032629. Epub 2012 Mar 5. PMID: 22403686; PMCID: PMC3293835.

- Junn E, Jang WH, Zhao X, Jeong BS, Mouradian MM. Mitochondrial localization of DJ-1 leads to enhanced neuroprotection. J Neurosci Res. 2009 Jan;87, 123-9. https://doi.org/10.1002/jnr.21831. PMID: 18711745; PMCID: PMC2752655.

- Irrcher I, Aleyasin H, Seifert EL, Hewitt SJ, Chhabra S, Phillips M, Lutz AK, Rousseaux MW, Bevilacqua L, Jahani-Asl A, Callaghan S, MacLaurin JG, Winklhofer KF, Rizzu P, Rippstein P, Kim RH, Chen CX, Fon EA, Slack RS, Harper ME, McBride HM, Mak TW, Park DS. Loss of the Parkinson's disease-linked gene DJ-1 perturbs mitochondrial dynamics. Hum Mol Genet. 2010 Oct 1;19, 3734-46. https://doi.org/10.1093/hmg/ddq288. Epub 2010 Jul 16. PMID: 20639397.

- Im JY, Lee KW, Woo JM, Junn E, Mouradian MM. DJ-1 induces thioredoxin 1 expression through the Nrf2 pathway. Hum Mol Genet. 2012 Jul 1;21, 3013-24. https://doi.org/10.1093/hmg/dds131. Epub 2012 Apr 5. PMID: 22492997; PMCID: PMC3373246.

- Dolgacheva LP, Berezhnov AV, Fedotova EI, Zinchenko VP, Abramov AY. Role of DJ-1 in the mechanism of pathogenesis of Parkinson's disease. J Bioenerg Biomembr. 2019 Jun;51, 175-188. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10863-019-09798-4. Epub 2019 May 3. PMID: 31054074; PMCID: PMC6531411.

- Goldberg MS, Pisani A, Haburcak M, Vortherms TA, Kitada T, Costa C, Tong Y, Martella G, Tscherter A, Martins A, Bernardi G, Roth BL, Pothos EN, Calabresi P, Shen J. Nigrostriatal dopaminergic deficits and hypokinesia caused by inactivation of the familial Parkinsonism-linked gene DJ-1. Neuron. 2005 Feb 17;45, 489-96. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neuron.2005.01.041. PMID: 15721235.

- Farshim PP, Bates GP. Mouse Models of Huntington's Disease. Methods Mol Biol. 2018;1780:97-120. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-1-4939-7825-0_6. PMID: 29856016.

- Jurcau A, Jurcau CM. Mitochondria in Huntington's disease: implications in pathogenesis and mitochondrial-targeted therapeutic strategies. Neural Regen Res. 2023 Jul;18, 1472-1477. https://doi.org/10.4103/1673-5374.360289. PMID: 36571344.

- Pouladi MA, Morton AJ, Hayden MR. Choosing an animal model for the study of Huntington's disease. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2013 Oct;14, 708-21. https://doi.org/10.1038/nrn3570. PMID: 24052178.

- Yu ZX, Li SH, Evans J, Pillarisetti A, Li H, Li XJ. Mutant huntingtin causes context-dependent neurodegeneration in mice with Huntington's disease. J Neurosci. 2003 Mar 15;23, 2193-202. https://doi.org/10.1523/JNEUROSCI.23-06-02193.2003. PMID: 12657678; PMCID: PMC6742008.

- Choo YS, Johnson GV, MacDonald M, Detloff PJ, Lesort M. Mutant huntingtin directly increases susceptibility of mitochondria to the calcium-induced permeability transition and cytochrome c release. Hum Mol Genet. 2004 Jul 15;13, 1407-20. https://doi.org/10.1093/hmg/ddh162. Epub 2004 May 26. PMID: 15163634.

- Panov AV, Gutekunst CA, Leavitt BR, Hayden MR, Burke JR, Strittmatter WJ, Greenamyre JT. Early mitochondrial calcium defects in Huntington's disease are a direct effect of polyglutamines. Nat Neurosci. 2002 Aug;5, 731-6. https://doi.org/10.1038/nn884. PMID: 12089530.

- Mangiarini L, Sathasivam K, Seller M, Cozens B, Harper A, Hetherington C, Lawton M, Trottier Y, Lehrach H, Davies SW, Bates GP. Exon 1 of the HD gene with an expanded CAG repeat is sufficient to cause a progressive neurological phenotype in transgenic mice. Cell. 1996 Nov 1;87, 493-506. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81369-0. PMID: 8898202.

- Menalled L, El-Khodor BF, Patry M, Suárez-Fariñas M, Orenstein SJ, Zahasky B, Leahy C, Wheeler V, Yang XW, MacDonald M, Morton AJ, Bates G, Leeds J, Park L, Howland D, Signer E, Tobin A, Brunner D. Systematic behavioral evaluation of Huntington's disease transgenic and knock-in mouse models. Neurobiol Dis. 2009 Sep;35, 319-36. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.nbd.2009.05.007. Epub 2009 May 21. PMID: 19464370; PMCID: PMC2728344.

- Bogdanov MB, Andreassen OA, Dedeoglu A, Ferrante RJ, Beal MF. Increased oxidative damage to DNA in a transgenic mouse model of Huntington's disease. J Neurochem. 2001 Dec;79, 1246-9. https://doi.org/10.1046/j.1471-4159.2001.00689.x. PMID: 11752065.

- Tabrizi SJ, Workman J, Hart PE, Mangiarini L, Mahal A, Bates G, Cooper JM, Schapira AH. Mitochondrial dysfunction and free radical damage in the Huntington R6/2 transgenic mouse. Ann Neurol. 2000 Jan;47, 80-6. https://doi.org/10.1002/1531-8249(200001)47:1<80::aid-ana13>3.3.co;2-b. PMID: 10632104.

- Petersen MH, Willert CW, Andersen JV, Madsen M, Waagepetersen HS, Skotte NH, Nørremølle A. Progressive Mitochondrial Dysfunction of Striatal Synapses in R6/2 Mouse Model of Huntington's Disease. J Huntingtons Dis. 2022;11, 121-140. https://doi.org/10.3233/JHD-210518. PMID: 35311711.

- Milnerwood AJ, Raymond LA. Corticostriatal synaptic function in mouse models of Huntington's disease: early effects of huntingtin repeat length and protein load. J Physiol. 2007 Dec 15;585(Pt 3):817-31. https://doi.org/10.1113/jphysiol.2007.142448. Epub 2007 Oct 18. PMID: 17947312; PMCID: PMC2375504.

- Giralt A, Saavedra A, Alberch J, Pérez-Navarro E. Cognitive Dysfunction in Huntington's Disease: Humans, Mouse Models and Molecular Mechanisms. J Huntingtons Dis. 2012;1, 155-73. https://doi.org/10.3233/JHD-120023. PMID: 25063329.

- Ghiglieri V, Bagetta V, Calabresi P, Picconi B. Functional interactions within striatal microcircuit in animal models of Huntington's disease. Neuroscience. 2012 Jun 1;211:165-84. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neuroscience.2011.06.075. Epub 2011 Jul 1. PMID: 21756979.

- Nithianantharajah J, Hannan AJ. Dysregulation of synaptic proteins, dendritic spine abnormalities and pathological plasticity of synapses as experience-dependent mediators of cognitive and psychiatric symptoms in Huntington's disease. Neuroscience. 2013 Oct 22;251:66-74. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neuroscience.2012.05.043. Epub 2012 May 24. PMID: 22633949.

- Ghiglieri V, Campanelli F, Marino G, Natale G, Picconi B, Calabresi P. Corticostriatal synaptic plasticity alterations in the R6/1 transgenic mouse model of Huntington's disease. J Neurosci Res. 2019 Dec;97, 1655-1664. https://doi.org/10.1002/jnr.24521. Epub 2019 Sep 9. PMID: 31498496.

- Rosenstock TR, Bertoncini CR, Teles AV, Hirata H, Fernandes MJ, Smaili SS. Glutamate-induced alterations in Ca2+ signaling are modulated by mitochondrial Ca2+ handling capacity in brain slices of R6/1 transgenic mice. Eur J Neurosci. 2010 Jul;32, 60-70. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1460-9568.2010.07268.x. PMID: 20608968.

- Clark JB. N-acetyl aspartate: a marker for neuronal loss or mitochondrial dysfunction. Dev Neurosci. 1998;20(4-5):271-6. https://doi.org/10.1159/000017321. PMID: 9778562.

- Jenkins BG, Klivenyi P, Kustermann E, Andreassen OA, Ferrante RJ, Rosen BR, Beal MF. Nonlinear decrease over time in N-acetyl aspartate levels in the absence of neuronal loss and increases in glutamine and glucose in transgenic Huntington's disease mice. J Neurochem. 2000 May;74, 2108-19. https://doi.org/10.1046/j.1471-4159.2000.0742108.x. PMID: 10800956.

- Andreassen OA, Dedeoglu A, Ferrante RJ, Jenkins BG, Ferrante KL, Thomas M, Friedlich A, Browne SE, Schilling G, Borchelt DR, Hersch SM, Ross CA, Beal MF. Creatine increase survival and delays motor symptoms in a transgenic animal model of Huntington's disease. Neurobiol Dis. 2001 Jun;8, 479-91. https://doi.org/10.1006/nbdi.2001.0406. PMID: 11447996.

- Jenkins BG, Andreassen OA, Dedeoglu A, Leavitt B, Hayden M, Borchelt D, Ross CA, Ferrante RJ, Beal MF. Effects of CAG repeat length, HTT protein length and protein context on cerebral metabolism measured using magnetic resonance spectroscopy in transgenic mouse models of Huntington's disease. J Neurochem. 2005 Oct;95, 553-62. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1471-4159.2005.03411.x. Epub 2005 Aug 31. PMID: 16135087.

- Tkac I, Dubinsky JM, Keene CD, Gruetter R, Low WC. Neurochemical changes in Huntington R6/2 mouse striatum detected by in vivo 1H NMR spectroscopy. J Neurochem. 2007 Mar;100, 1397-406. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1471-4159.2006.04323.x. Epub 2007 Jan 8. PMID: 17217418; PMCID: PMC2859960.

- Browne SE. Mitochondria and Huntington's disease pathogenesis: insight from genetic and chemical models. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2008 Dec;1147:358-82. https://doi.org/10.1196/annals.1427.018. PMID: 19076457.

- Lopes C, Ferreira IL, Maranga C, Beatriz M, Mota SI, Sereno J, Castelhano J, Abrunhosa A, Oliveira F, De Rosa M, Hayden M, Laço MN, Januário C, Castelo Branco M, Rego AC. Mitochondrial and redox modifications in early stages of Huntington's disease. Redox Biol. 2022 Oct;56:102424. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.redox.2022.102424. Epub 2022 Aug 10. PMID: 35988447; PMCID: PMC9420526.

- Wright DJ, Renoir T, Smith ZM, Frazier AE, Francis PS, Thorburn DR, McGee SL, Hannan AJ, Gray LJ. N-Acetylcysteine improves mitochondrial function and ameliorates behavioral deficits in the R6/1 mouse model of Huntington's disease. Transl Psychiatry. 2015 Jan 6;5, e492. https://doi.org/10.1038/tp.2014.131. PMID: 25562842; PMCID: PMC4312826.

- Herbst EA, Holloway GP. Exercise training normalizes mitochondrial respiratory capacity within the striatum of the R6/1 model of Huntington's disease. Neuroscience. 2015 Sep 10;303:515-23. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neuroscience.2015.07.025. Epub 2015 Jul 14. PMID: 26186895.

- Gardian G, Browne SE, Choi DK, Klivenyi P, Gregorio J, Kubilus JK, Ryu H, Langley B, Ratan RR, Ferrante RJ, Beal MF. Neuroprotective effects of phenylbutyrate in the N171-82Q transgenic mouse model of Huntington's disease. J Biol Chem. 2005 Jan 7;280, 556-63. https://doi.org/10.1074/jbc.M410210200. Epub 2004 Oct 19. PMID: 15494404.

- Hermel E, Gafni J, Propp SS, Leavitt BR, Wellington CL, Young JE, Hackam AS, Logvinova AV, Peel AL, Chen SF, Hook V, Singaraja R, Krajewski S, Goldsmith PC, Ellerby HM, Hayden MR, Bredesen DE, Ellerby LM. Specific caspase interactions and amplification are involved in selective neuronal vulnerability in Huntington's disease. Cell Death Differ. 2004 Apr;11, 424-38. https://doi.org/10.1038/sj.cdd.4401358. PMID: 14713958.

- Wellington CL, Ellerby LM, Hackam AS, Margolis RL, Trifiro MA, Singaraja R, McCutcheon K, Salvesen GS, Propp SS, Bromm M, Rowland KJ, Zhang T, Rasper D, Roy S, Thornberry N, Pinsky L, Kakizuka A, Ross CA, Nicholson DW, Bredesen DE, Hayden MR. Caspase cleavage of gene products associated with triplet expansion disorders generates truncated fragments containing the polyglutamine tract. J Biol Chem. 1998 Apr 10;273, 9158-67. https://doi.org/10.1074/jbc.273.15.9158. PMID: 9535906.

- Ona VO, Li M, Vonsattel JP, Andrews LJ, Khan SQ, Chung WM, Frey AS, Menon AS, Li XJ, Stieg PE, Yuan J, Penney JB, Young AB, Cha JH, Friedlander RM. Inhibition of caspase-1 slows disease progression in a mouse model of Huntington's disease. Nature. 1999 May 20;399, 263-7. https://doi.org/10.1038/20446. PMID: 10353249.

- Carroll JB, Southwell AL, Graham RK, Lerch JP, Ehrnhoefer DE, Cao LP, Zhang WN, Deng Y, Bissada N, Henkelman RM, Hayden MR. Mice lacking caspase-2 are protected from behavioral changes, but not pathology, in the YAC128 model of Huntington disease. Mol Neurodegener. 2011 Aug 19;6:59. https://doi.org/10.1186/1750-1326-6-59. PMID: 21854568; PMCID: PMC3180273.

- M. Avenali, S. Cerri, G. Ongari, C. Ghezzi, C. Pacchetti, C. Tassorelli, E.M. Valente, F.vBlandini, Profiling the Biochemical Signature of GBA-Related Parkinson’s Disease invPeripheral Blood Mononuclear Cells, Mov. Disord. 36 (2021) 1267–1272. [CrossRef]

- S. Petrillo, T. Schirinzi, G. Di Lazzaro, J. D’Amico, V.L. Colona, E. Bertini, M. Pierantozzi, L. Mari, N.B. Mercuri, F. Piemonte, A. Pisani, Systemic activation of Nrf2 pathway in Parkinson’s disease, Mov. Disord. (2019). https://doi.org/10.1002/mds.27878.

- T. Schirinzi, I. Salvatori, H. Zenuni, P. Grillo, C. Valle, G. Martella, N.B. Mercuri, A. Ferri,vPattern of Mitochondrial Respiration in Peripheral Blood Cells of Patients with Parkinson’s Disease, Int. J. Mol. Sci. 23 (2022) 10863. [CrossRef]

- S.J. Annesley, S.T. Lay, S.W. De Piazza, O. Sanislav, E. Hammersley, C.Y. Allan, L.M. Francione, M.Q. Bui, Z.P. Chen, K.R.W. Ngoei, F. Tassone, B.E. Kemp, E. Storey, A. Evans, D.Z. Loesch, P.R. Fisher, Immortalized Parkinson’s disease lymphocytes have enhanced mitochondrial respiratory activity, Dis. Model. Mech. 9 (2016) 1295. [CrossRef]

- W. Haylett, C. Swart, F. Van Der Westhuizen, H. Van Dyk, L. Van Der Merwe, C. Van Der Merwe, B. Loos, J. Carr, C. Kinnear, S. Bardien, Altered Mitochondrial Respiration and Other Features of Mitochondrial Function in Parkin-Mutant Fibroblasts from Parkinson’s Disease Patients, Parkinsons. Dis. 2016 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1155/2016/1819209.

- P.M.A. Antony, O. Kondratyeva, K. Mommaerts, M. Ostaszewski, K. Sokolowska, A.S. Baumuratov, L. Longhino, J.F. Poulain, D. Grossmann, R. Balling, R. Krüger, N.J. Diederich, Fibroblast mitochondria in idiopathic Parkinson’s disease display morphological changes and enhanced resistance to depolarization, Sci. Rep. 10 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1038/S41598- 020-58505-6.

- M. Fais, A. Dore, M. Galioto, G. Galleri, C. Crosio, C. Iaccarino, Parkinson’s Disease- Related Genes and Lipid Alteration, Int. J. Mol. Sci. 22 (2021). [CrossRef]

- A.M. Smith, C. Depp, B.J. Ryan, G.I. Johnston, J. Alegre-Abarrategui, S. Evetts, M. Rolinski, F. Baig, C. Ruffmann, A.K. Simon, M.T.M. Hu, R. Wade-Martins, Mitochondrial dysfunction and increased glycolysis in prodromal and early Parkinson’s blood cells, Mov. Disord. 33 (2018) 1580–1590. [CrossRef]

- J.F. Havelund, N.H.H. Heegaard, N.J.K. Færgeman, J.B. Gramsbergen, Biomarker researchvin parkinson’s disease using metabolite profiling, Metabolites. 7 (2017). [CrossRef]

- D. Willkommen, M. Lucio, F. Moritz, S. Forcisi, B. Kanawati, K.S. Smirnov, M. Schroeter,A. Sigaroudi, P. Schmitt-Kopplin, B. Michalke, Metabolomic investigations in cerebrospinal fluid of Parkinson’s disease, PLoS One. 13 (2018). [CrossRef]

- S. Saiki, T. Hatano, M. Fujimaki, K.-I. Ishikawa, A. Mori, Y. Oji, A. Okuzumi, T. Fukuhara,T. Koinuma, Y. Imamichi, M. Nagumo, N. Furuya, S. Nojiri, T. Amo, K. Yamashiro, N. Hattori, Decreased long-chain acylcarnitines from insufficient β-oxidation as potential early diagnostic markers for Parkinson’s disease OPEN, (n.d.). [CrossRef]

- Ascherio, M.A. Schwarzschild, The epidemiology of Parkinson’s disease: risk factors and prevention, Lancet Neurol. 15 (2016) 1257–1272. https://doi.org/10.1016/S1474-4422(16)30230-7.

- T. Schirinzi, G. Di Lazzaro, G.M. Sancesario, S. Summa, S. Petrucci, V.L. Colona, S. Bernardini, M. Pierantozzi, A. Stefani, N.B. Mercuri, A. Pisani, Young-onset and late-onset Parkinson’s disease exhibit a different profile of fluid biomarkers and clinical features, Neurobiol. Aging. 90 (2020) 119–124. [CrossRef]

- T. Schirinzi, G. Vasco, G. Zanni, S. Petrillo, F. Piemonte, E. Castelli, E.S. Bertini, Serum uric acid in Friedreich Ataxia, Clin. Biochem. 54 (2018) 139–141. [CrossRef]

- T. Schirinzi, G. Di Lazzaro, V.L. Colona, P. Imbriani, M. Alwardat, G.M. Sancesario, A. Martorana, A. Pisani, Assessment of serum uric acid as risk factor for tauopathies., J. Neural Transm. (2017). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00702-017-1743-6.

- Z. Wei, X. Li, X. Li, Q. Liu, Y. Cheng, Oxidative Stress in Parkinson’s Disease: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis, Front. Mol. Neurosci. 11 (2018) 236. [CrossRef]

- S.I. Ueno, T. Hatano, A. Okuzumi, S. Saiki, Y. Oji, A. Mori, T. Koinuma, M. Fujimaki, H. Takeshige-Amano, A. Kondo, N. Yoshikawa, T. Nojiri, M. Kurano, K. Yasukawa, Y.Yatomi, H. Ikeda, N. Hattori, Nonmercaptalbumin as an oxidative stress marker in Parkinson’s and PARK2 disease, Ann. Clin. Transl. Neurol. 7 (2020) 307–317. [CrossRef]

- Y. Yamagishi, K. Saigoh, Y. Saito, I. Ogawa, Y. Mitsui, Y. Hamada, M. Samukawa, H. Suzuki, M. Kuwahara, M. Hirano, N. Noguchi, S. Kusunoki, Diagnosis of Parkinson’s disease and the level of oxidized DJ-1 protein, Neurosci. Res. 128 (2018) 58–62. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neures.2017.06.008.

- G.M. Sancesario, G. Di Lazzaro, P. Grillo, B. Biticchi, E. Giannella, M. Alwardat, M. Pieri, S. Bernardini, N.B. Mercuri, A. Pisani, T. Schirinzi, Biofluids profile of α-Klotho in patients with Parkinson’s disease, Parkinsonism Relat. Disord. 90 (2021) 62–64. [CrossRef]

- E. Fernández-Espejo, F. Rodriguez de Fonseca, J. Suárez, Á. Martín de Pablos, Cerebrospinal fluid lactoperoxidase level is enhanced in idiopathic Parkinson’s disease, and correlates with levodopa equivalent daily dose, Brain Res. 1761 (2021) 147411. [CrossRef]

- W. Sun, J. Zheng, J. Ma, Z. Wang, X. Shi, M. Li, S. Huang, S. Hu, Z. Zhao, D. Li, Increased Plasma Heme Oxygenase-1 Levels in Patients With Early-Stage Parkinson’s Disease, Front. Aging Neurosci. 13 (2021) 39. [CrossRef]

- R. Shamir, C. Klein, D. Amar, E.J. Vollstedt, M. Bonin, M. Usenovic, Y.C. Wong, A. Maver, S. Poths, H. Safer, J.C. Corvol, S. Lesage, O. Lavi, G. Deuschl, G. Kuhlenbaeumer, H. Pawlack, I. Ulitsky, M. Kasten, O. Riess, A. Brice, B. Peterlin, D. Krainc, Analysis of blood-based gene expression in idiopathic Parkinson disease, Neurology. 89 (2017) 1676–1683. [CrossRef]

- Picca, F. Guerra, R. Calvani, F. Marini, A. Biancolillo, G. Landi, R. Beli, F. Landi, R. Bernabei, A.R. Bentivoglio, M.R. Lo Monaco, C. Bucci, E. Marzetti, Mitochondrial Signatures in Circulating Extracellular Vesicles of Older Adult with Parkinson’s Disease: Results from the EXosomes in PArkiNson’s Disease (EXPAND) Study, J. Clin. Med. 2020, Vol. 9, Page 504. 9 (2020) 504. https://doi.org/10.3390/JCM9020504.

- B.D. Paul, S.H. Snyder, Impaired Redox Signaling in Huntington’s Disease: Therapeutic Implications, Front. Mol. Neurosci. 12 (2019). https://doi.org/10.3389/FNMOL.2019.00068.

- P. Jędrak, P. Mozolewski, G. Węgrzyn, M.R. Więckowski, Mitochondrial alterations accompanied by oxidative stress conditions in skin fibroblasts of Huntington’s disease patients, Metab. Brain Dis. 33 (2018) 2005–2017. [CrossRef]

- M. Vanisova, H. Stufkova, M. Kohoutova, T. Rakosnikova, J. Krizova, J. Klempir, I. Rysankova, J. Roth, J. Zeman, H. Hansikova, Mitochondrial organization and structure are compromised in fibroblasts from patients with Huntington’s disease, Ultrastruct. Pathol. 46 (2022) 462–475. [CrossRef]

- A. Neueder, M. Orth, Mitochondrial biology and the identification of biomarkers of Huntington’s disease, Neurodegener. Dis. Manag. 10 (2020) 243–255. https://doi.org/10.2217/NMT- 2019-0033.

- C.M. Chen, Y.R. Wu, M.L. Cheng, J.L. Liu, Y.M. Lee, P.W. Lee, B.W. Soong, D.T.Y. Chiu, Increased oxidative damage and mitochondrial abnormalities in the peripheral blood of Huntington’s disease patients, Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 359 (2007) 335–340. https://doi.org/10.1016/J.BBRC.2007.05.093.

- Spinelli JB, Zaganjor E. Mitochondrial efficiency directs cell fate. Nat Cell Biol. 2022 Feb;24, 125-126. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41556-021-00834-3. PMID: 35165414.

- Ahmad M, Wolberg A, Kahwaji CI. Biochemistry, Electron Transport Chain. 2022 Sep 5. In: StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; 2022 Jan–. PMID: 30252361.

- McAdam E, Brem R, Karran P. Oxidative Stress-Induced Protein Damage Inhibits DNA Repair and Determines Mutation Risk and Therapeutic Efficacy. Mol Cancer Res. 2016 Jul;14, 612-22. https://doi.org/10.1158/1541-7786.MCR-16-0053. Epub 2016 Apr 22. PMID: 27106867; PMCID: PMC4955916.

- Korovila I, Hugo M, Castro JP, Weber D, Höhn A, Grune T, Jung T. Proteostasis, oxidative stress and aging. Redox Biol. 2017 Oct;13:550-567. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.redox.2017.07.008. Epub 2017 Jul 12. PMID: 28763764; PMCID: PMC5536880.

- Gerencser AA, Doczi J, Töröcsik B, Bossy-Wetzel E, Adam-Vizi V. Mitochondrial swelling measurement in situ by optimized spatial filtering: astrocyte-neuron differences. Biophys J. 2008 Sep;95, 2583-98. https://doi.org/10.1529/biophysj.107.118620. Epub 2008 Apr 18. PMID: 18424491; PMCID: PMC2517017.

- O'Sullivan JDB, Bullen A, Mann ZF. Mitochondrial form and function in hair cells. Hear Res. 2023 Feb;428:108660. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.heares.2022.108660. Epub 2022 Nov 25. PMID: 36525891.

- Woo J, Cho H, Seol Y, Kim SH, Park C, Yousefian-Jazi A, Hyeon SJ, Lee J, Ryu H. Power Failure of Mitochondria and Oxidative Stress in Neurodegeneration and Its Computational Models. Antioxidants (Basel). 2021 Feb 3;10, 229. https://doi.org/10.3390/antiox10020229. PMID: 33546471; PMCID: PMC7913624.

- Polyzos AA, McMurray CT. The chicken or the egg: mitochondrial dysfunction as a cause or consequence of toxicity in Huntington's disease. Mech Ageing Dev. 2017 Jan;161(Pt A):181-197. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.mad.2016.09.003. Epub 2016 Sep 12. PMID: 27634555; PMCID: PMC5543717.

- Franco-Iborra S, Vila M, Perier C. Mitochondrial Quality Control in Neurodegenerative Diseases: Focus on Parkinson's Disease and Huntington's Disease. Front Neurosci. 2018 May 23;12:342. https://doi.org/10.3389/fnins.2018.00342. PMID: 29875626; PMCID: PMC5974257.

- Catherine, E. Lang, Marghuretta D. Bland. Chapter 17 - Impaired Motor Control and Neurologic Rehabilitation in Older Adults, Editor(s): Dale Avers, Rita A. Wong, Guccione's Geriatric Physical Therapy (Fourth Edition), Mosby, 2020, Pages 379-399,ISBN 9780323609128. [CrossRef]

- Lee LN, Huang CS, Chuang HH, Lai HJ, Yang CK, Yang YC, Kuo CC. An electrophysiological perspective on Parkinson's disease: symptomatic pathogenesis and therapeutic approaches. J Biomed Sci. 2021 Dec 9;28, 85. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12929-021-00781-z. PMID: 34886870; PMCID: PMC8656091.

- Jamwal S, Kumar P. Insight Into the Emerging Role of Striatal Neurotransmitters in the Pathophysiology of Parkinson's Disease and Huntington's Disease: A Review. Curr Neuropharmacol. 2019;17, 165-175. https://doi.org/10.2174/1570159X16666180302115032. PMID: 29512464; PMCID: PMC6343208.

- Terreros-Roncal J, Moreno-Jiménez EP, Flor-García M, Rodríguez-Moreno CB, Trinchero MF, Cafini F, Rábano A, Llorens-Martín M. Impact of neurodegenerative diseases on human adult hippocampal neurogenesis. Science 2021 Nov 26;374, 1106-1113. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.abl5163. Epub 2021 Oct 21. PMID: 34672693; PMCID: PMC7613437.

- Carmo C, Naia L, Lopes C, Rego AC. Mitochondrial Dysfunction in Huntington's Disease. Adv Exp Med Biol. 2018, 1049, 59–83. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-71779-1_3. PMID: 29427098.

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).