Submitted:

25 January 2023

Posted:

30 January 2023

Read the latest preprint version here

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

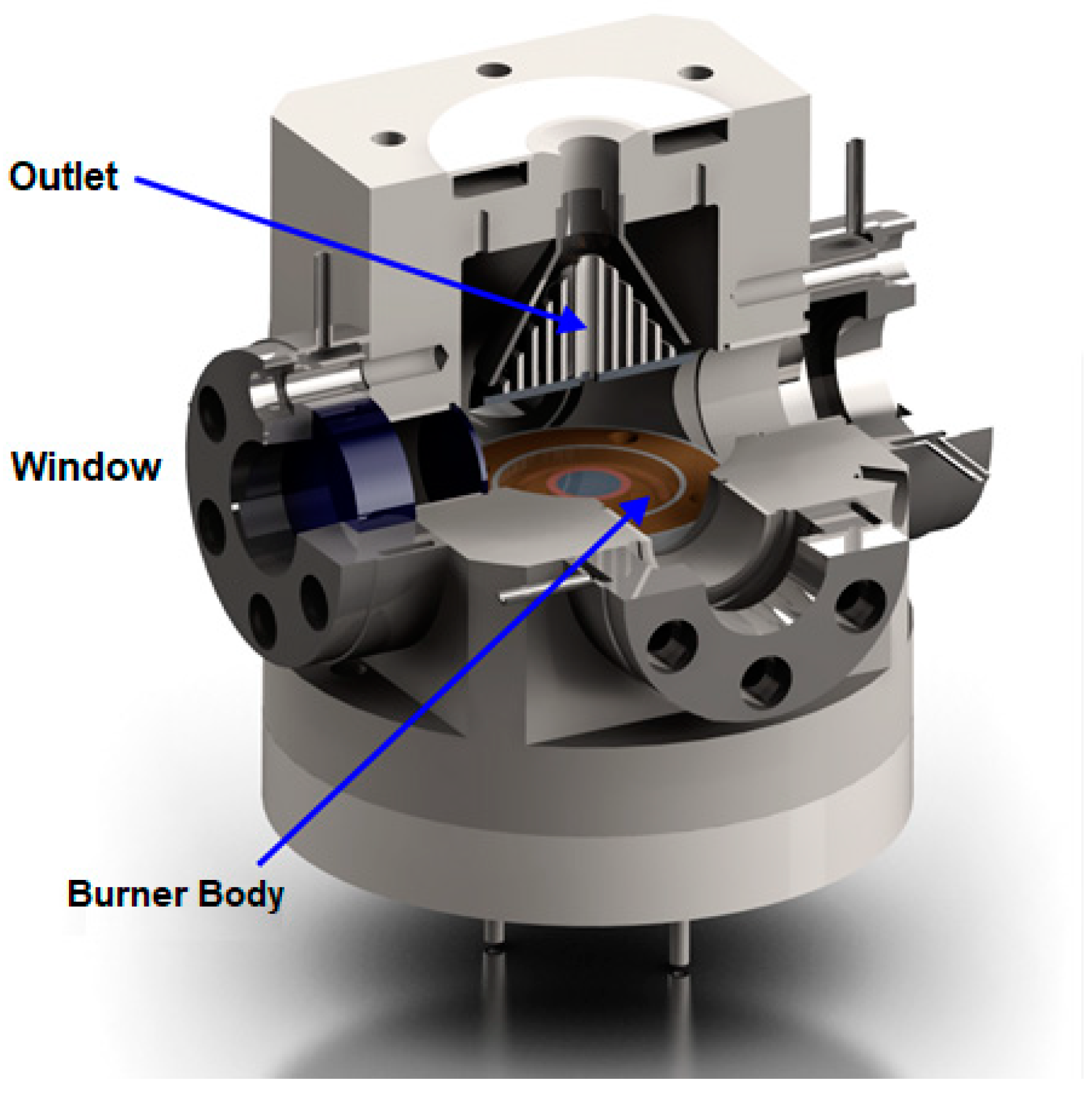

2. Simulation conditions and approaches

3. Results and discussion

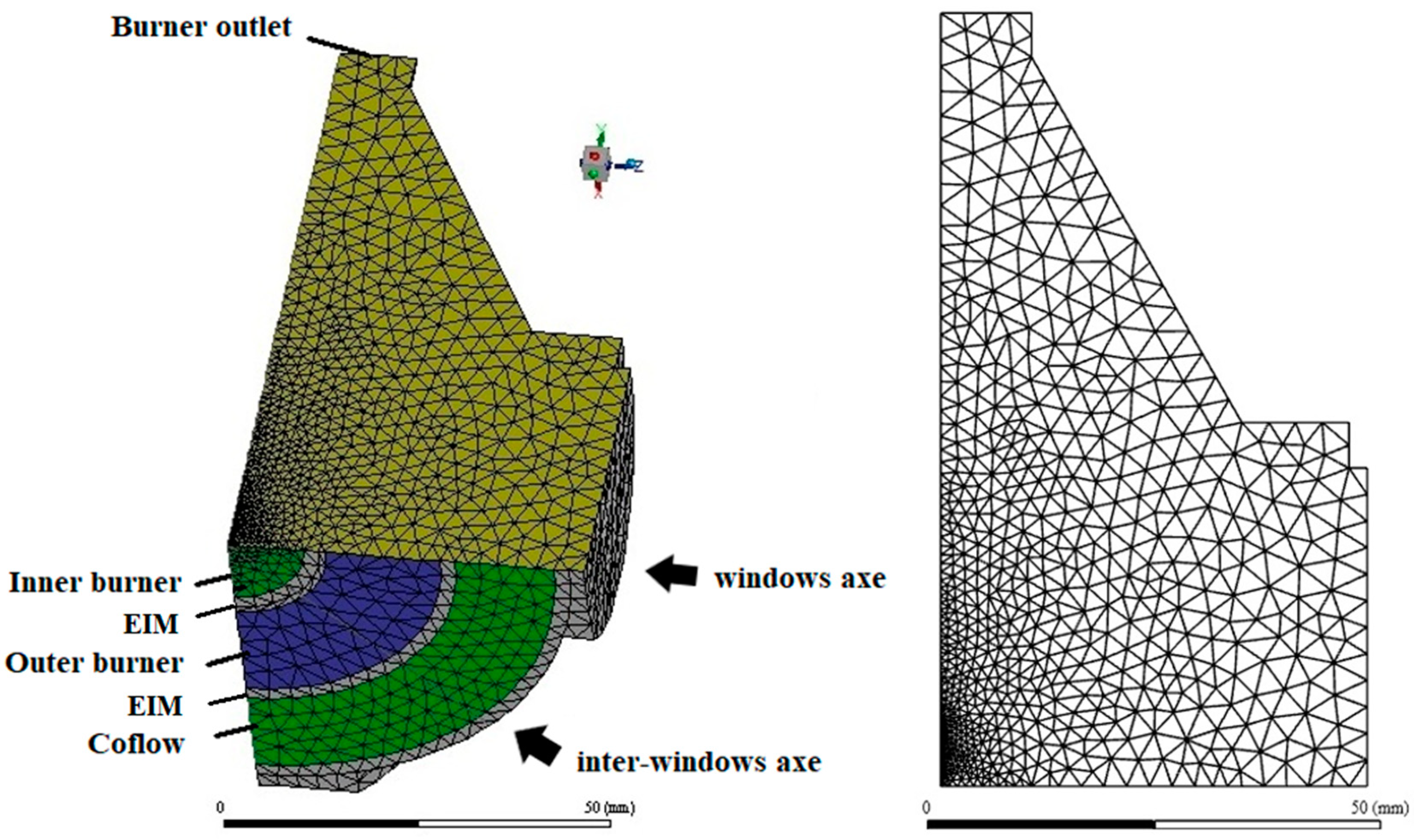

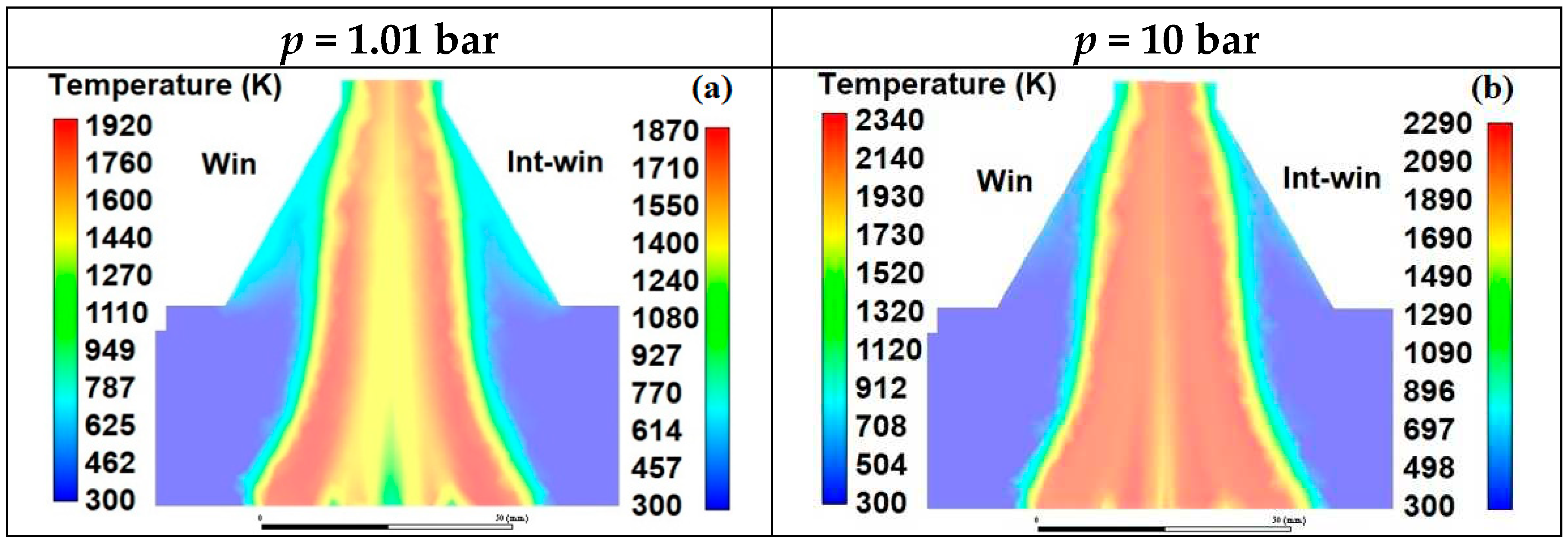

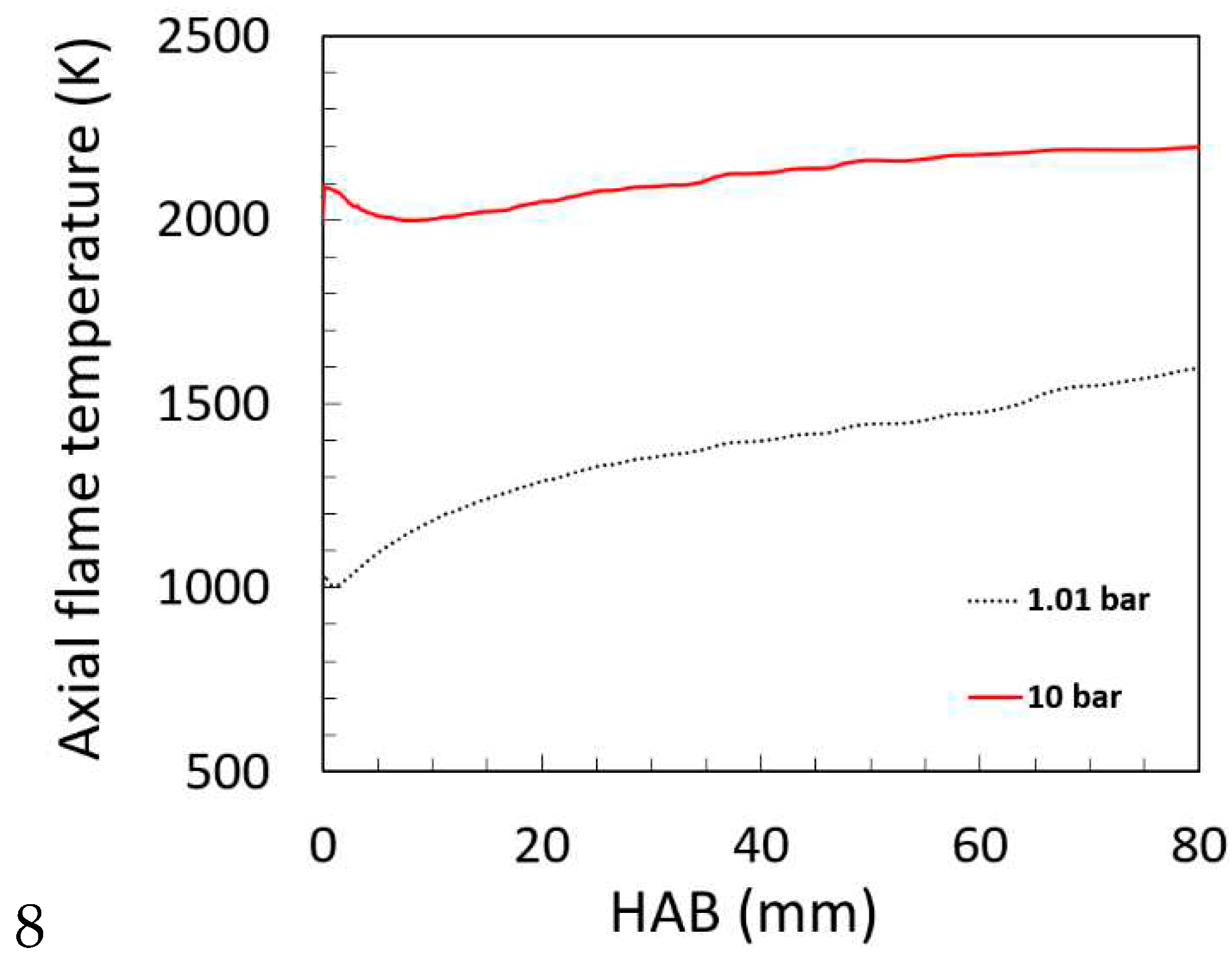

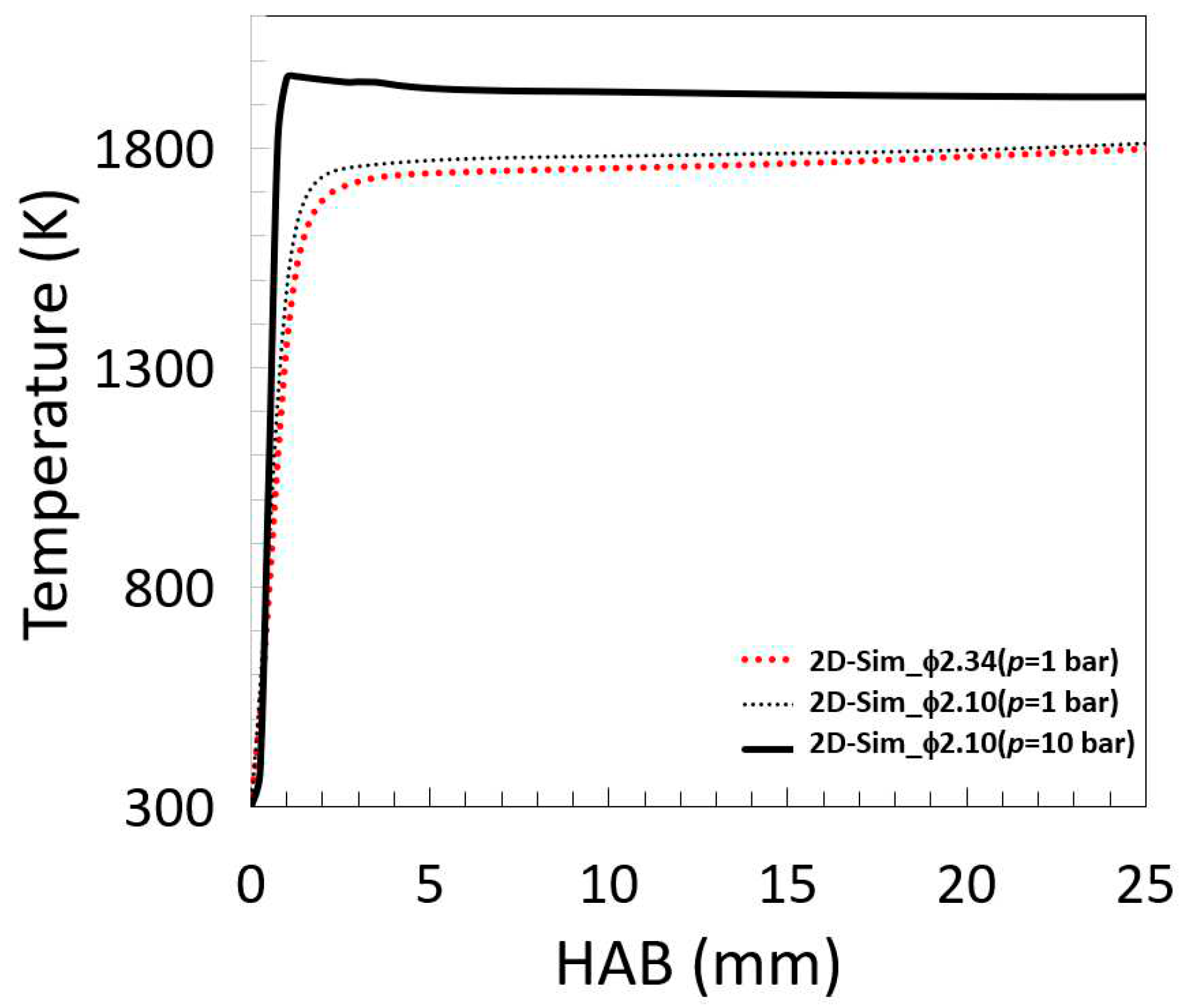

3.1. Justifying 2D- and 1D-simulation

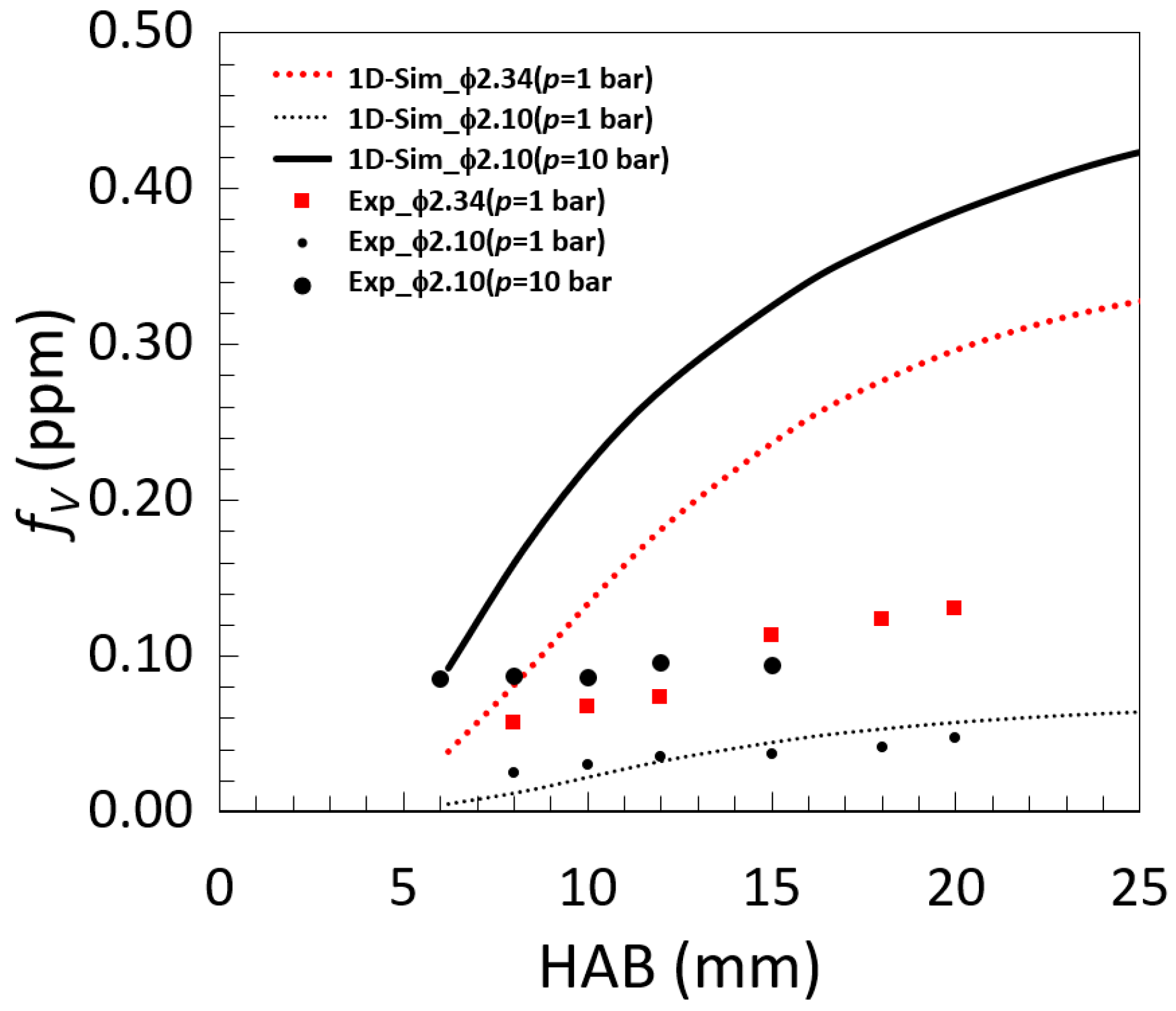

3.2. Demonstration study

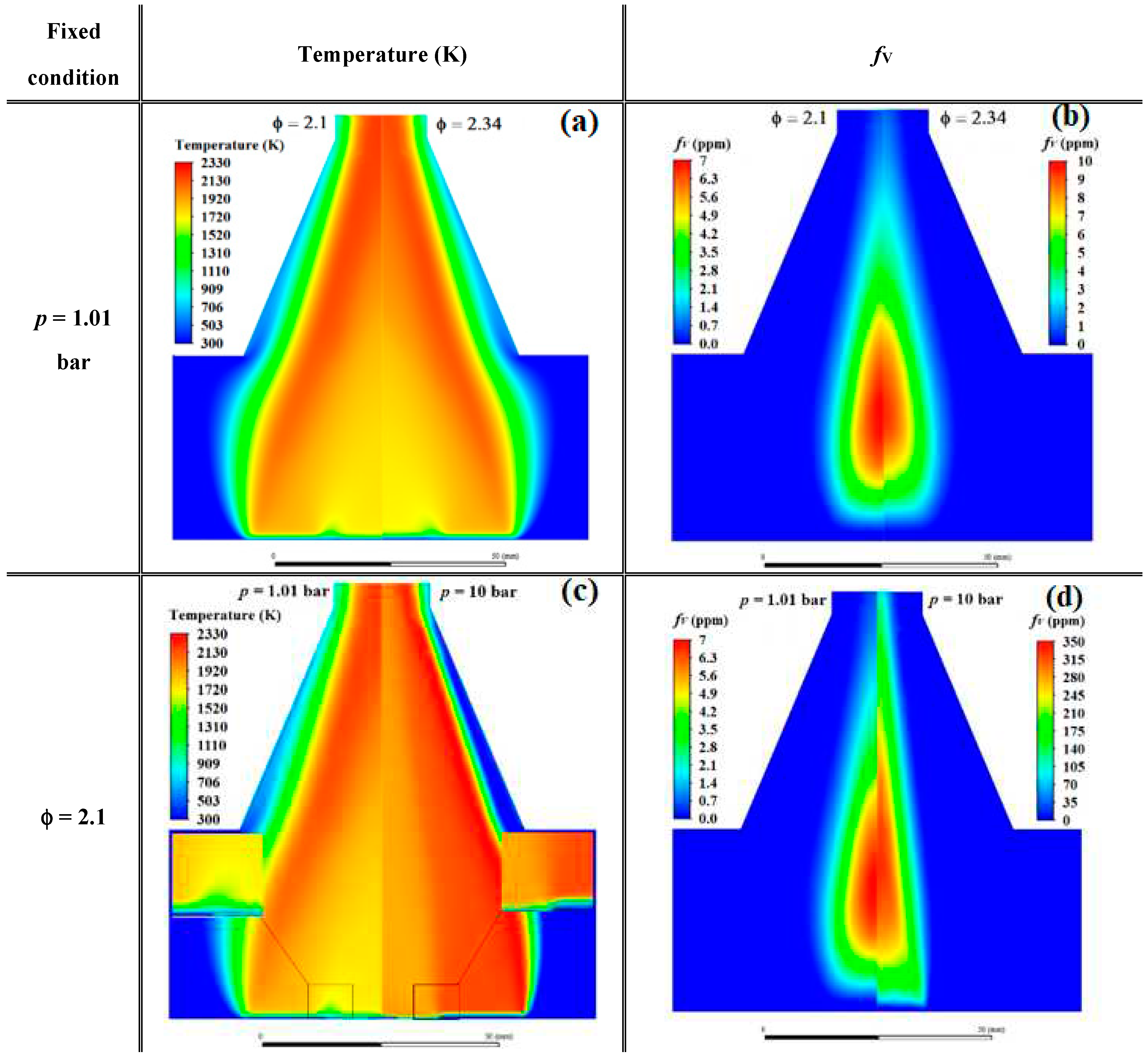

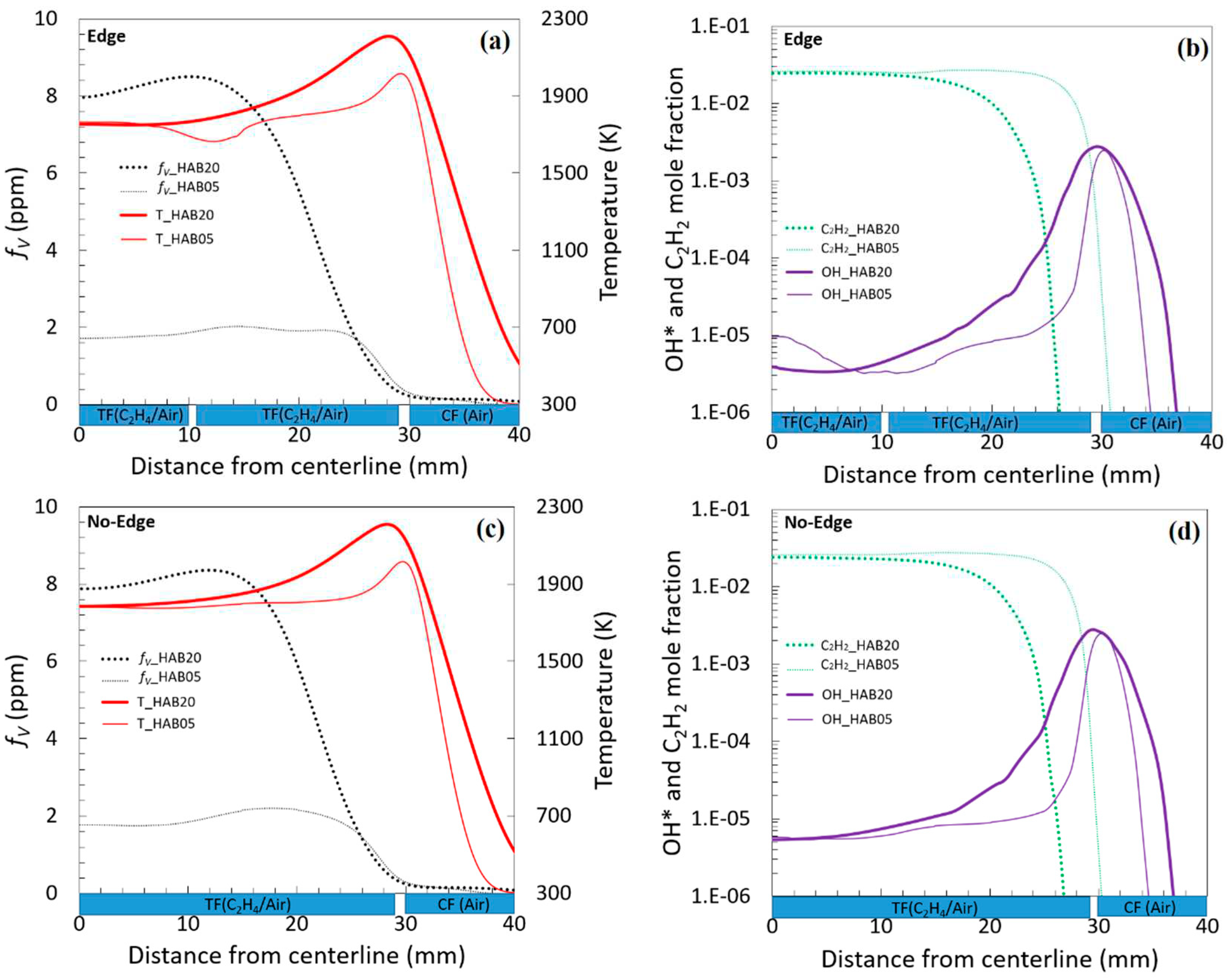

3.3. Pressure and edge inter-matrices effect

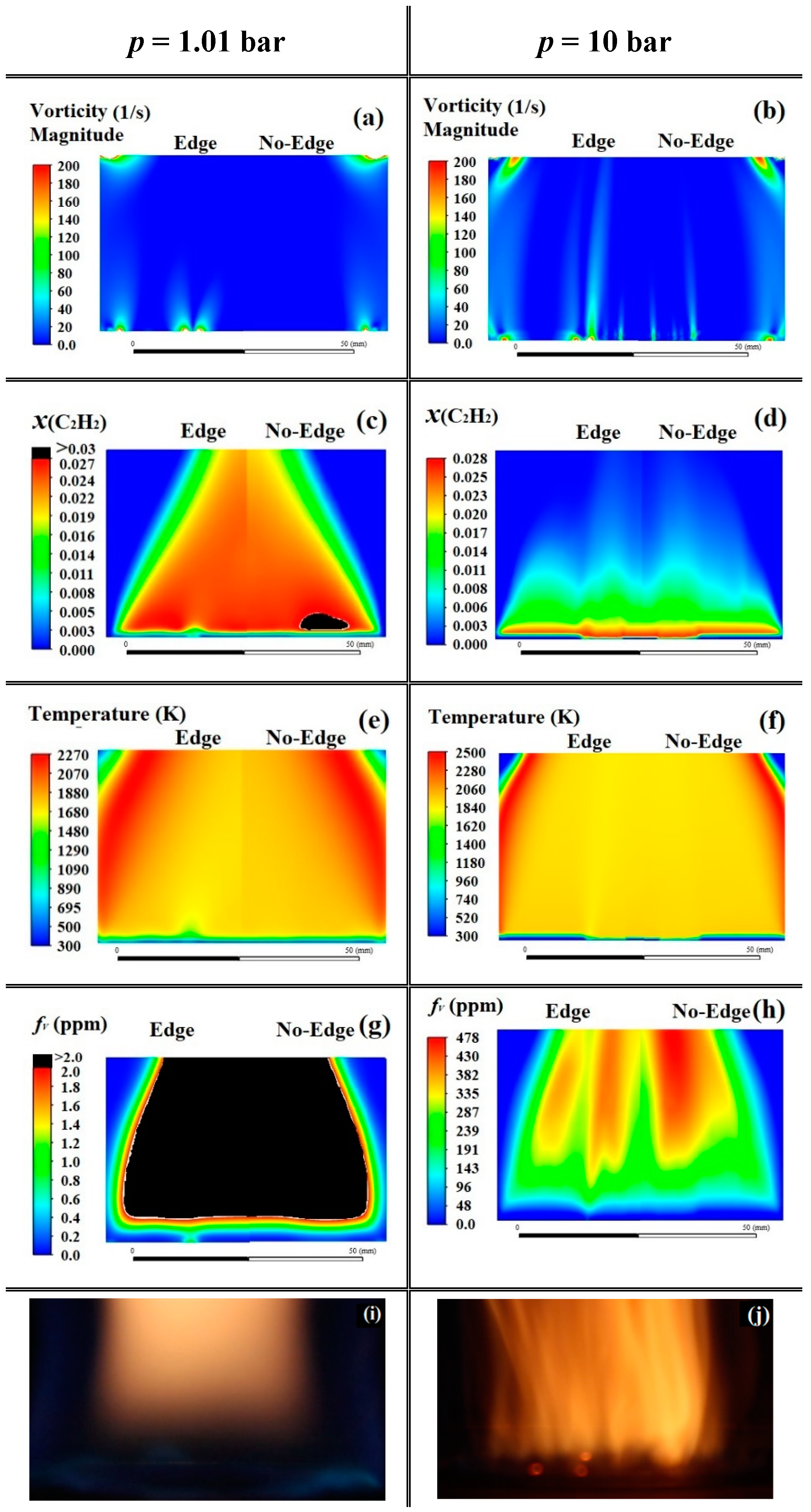

4. Conclusions

Acknowledgments

References

- M. Hofmann, W.G. Bessler, C. Schulz, H. Jander, Laser-induced incandescence for soot diagnostics at high pressures, Appl. Optics 42 (2003) 2052-2062.

- M. Hofmann, H. Kronemayer, B. Kock, H. Jander, C. Schulz, Laser-induced incandescence and multi-line NO-LIF thermometry for soot diagnostics at high pressures, In European Combustion Meeting, Louvain-la-Neuve, Belgium2005.

- M.S. Tsurikov, K.P. Geigle, V. KrÜGer, Y. Schneider-KÜHnle, W. Stricker, R. LÜCkerath, R. Hadef, M. Aigner, Laser-based investigation of soot formation in laminar premixed flames at atmospheric and elevated pressures, Combust. Sci. Technol. 177 (2005) 1835-1862.

- M. Leschowski, T. Dreier, C. Schulz, An automated thermophoretic soot sampling device for laboratory-scale high-pressure flames, Rev. Sci. Instrum. 85 (2014) 045103.

- M. Leschowski, T. Dreier, C. Schulz, A Standard Burner for High Pressure Laminar Premixed Flames: Detailed Soot Diagnostics, Zeitschrift für Physikalische Chemie, 2015, pp. 781-805.

- X. Mi, A. Saylam, T. Endres, C. Schulz, T. Dreier, Near-threshold soot formation in premixed flames at elevated pressure, Carbon 181 (2021) 143-154.

- T. Heidermann, H. Jander, H. Gg. Wagner, Soot particles in premixed C2H4–air-flames at high pressures (P=30–70 bar), Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 1 (1999) 3497-3502.

- F. Migliorini, S. De Iuliis, F. Cignoli, G. Zizak, How “flat” is the rich premixed flame produced by your McKenna burner?, Combust. Flame 153 (2008) 384-393.

- R. Hadef, K.P. Geigle, W. Meier, M. Aigner, Soot characterization with laser-induced incandescence applied to a laminar premixed ethylene–air flame, International Journal of Thermal Sciences 49 (2010) 1457-1467.

- P. Desgroux, X. Mercier, B. Lefort, R. Lemaire, E. Therssen, J.F. Pauwels, Soot volume fraction measurement in low-pressure methane flames by combining laser-induced incandescence and cavity ring-down spectroscopy: Effect of pressure on soot formation, Combust. Flame 155 (2008) 289-301.

- P. Desgroux, A. Faccinetto, X. Mercier, T. Mouton, D. Aubagnac Karkar, A. El Bakali, Comparative study of the soot formation process in a “nucleation” and a “sooting” low pressure premixed methane flame, Combust. Flame 184 (2017) 153-166.

- P. Desgroux, C. Betrancourt, X. Mercier. Development of highly sensitive quantitative measurements of nascent soot particles in flames by coupling cavity-ring-down extinction and laser induced incandescence for improving the understanding of soot nucleation process. In: editor^editors. OSA Technical Digest. In Laser Applications to Chemical, Security and Environmental Analysis; 2018/06/25 2018; Orlando, Florida: Optical Society of America. p. LTu5C.1.

- S. Bejaoui, S. Batut, E. Therssen, N. Lamoureux, P. Desgroux, F. Liu, Measurements and modeling of laser-induced incandescence of soot at different heights in a flat premixed flame, Appl. Phys. B 118 (2015) 449-469.

- Holthuis & Associates, The McKenna Flat Flame Burner, P.O. Box 1531, Sebastopol, CA 95473.

- C. Kim, F. Xu, P. Sunderland, A. El-Leathy, G. Faeth. Soot formation and oxidation in laminar flames. In: editor^editors. 44th AIAA Aerospace Sciences Meeting and Exhibit; 2006. p. 1508.

- T. Mouton, X. Mercier, M. Wartel, N. Lamoureux, P. Desgroux, Laser-induced incandescence technique to identify soot nucleation and very small particles in low-pressure methane flames, Appl. Phys. B 112 (2013) 369-379.

- D. Aubagnac-Karkar, A. El Bakali, P. Desgroux, Soot particles inception and PAH condensation modelling applied in a soot model utilizing a sectional method, Combust. Flame 189 (2018) 190-206.

- G. Skandan, Y.J. Chen, N. Glumac, B.H. Kear, Synthesis of oxide nanoparticles in low pressure flames, Nanostructured Materials 11 (1999) 149-158.

- C. Weise, A. Faccinetto, S. Kluge, T. Kasper, H. Wiggers, C. Schulz, I. Wlokas, A. Kempf, Buoyancy induced limits for nanoparticle synthesis experiments in horizontal premixed low-pressure flat-flame reactors, Combustion Theory and Modelling 17 (2013) 504-521.

- A.M. Pennington, H. Halim, J. Shi, B.H. Kear, F.E. Celik, S.D. Tse, Low-pressure flame synthesis of carbon-stabilized TiO2-II (srilankite) nanoparticles, Journal of Aerosol Science 156 (2021) 105775.

- M. Gu, F. Liu, J.-L. Consalvi, Ö.L. Gülder, Effects of pressure on soot formation in laminar coflow methane/air diffusion flames doped with n-heptane and toluene between 2 and 8 atm, Proc. Combust. Inst. 38 (2021) 1403-1412.

- H. Böhm, C. Feldermann, T. Heidermann, H. Jander, B. Lüers, H.G. Wagner, Soot formation in premixed C2H4-air flames for pressures up to 100 bar, Symposium (International) on Combustion 24 (1992) 991-998.

- H. Böhm, D. Hesse, H. Jander, B. Lüers, J. Pietscher, H.G.G. Wagner, M. Weiss, The influence of pressure and temperature on soot formation in premixed flames, Symposium (International) on Combustion 22 (1989) 403-411.

- Ciajolo, A. D'Anna, R. Barbella, A. Tregrossi, A. Violi, The effect of temperature on soot inception in premixed ethylene flames, Symposium (International) on Combustion 26 (1996) 2327-2333.

- K. Ishii, N. Ohashi, A. Teraji, M. Kubo. Soot formation in hydrocarbon pyrolysis behind reflected shock waves. In: editor^editors. Proc. 22nd Int. Colloquium on the Dynamics of Explosions and Reactive Systems; 2009. p.

- G. Prado, J. Lahaye, Physical Aspects of Nucleation and Growth of Soot Particles, in: D.C. Siegla, G.W. Smith (Eds.), Particulate Carbon: Formation During Combustion, Springer US, Boston, MA, 1981, pp. 143-175.

- R. Whitesides, M. Frenklach, Detailed Kinetic Monte Carlo Simulations of Graphene-Edge Growth, The Journal of Physical Chemistry A 114 (2010) 689-703.

- P. Fortugno, S. Musikhin, X. Shi, H. Wang, H. Wiggers, C. Schulz, Synthesis of freestanding few-layer graphene in microwave plasma: the role of oxygen, Carbon 186 (2021) 560-573.

- H. Bladh, N.-E. Olofsson, T. Mouton, J. Simonsson, X. Mercier, A. Faccinetto, P.-E. Bengtsson, P. Desgroux, Probing the smallest soot particles in low-sooting premixed flames using laser-induced incandescence, Proc. Combust. Inst. 35 (2015) 1843-1850.

- ANSYS® Academic Research Mechanical, Release 20.0.

- S.J. Brookes, J.B. Moss, Predictions of soot and thermal radiation properties in confined turbulent jet diffusion flames, Combust. Flame 116 (1999) 486-503.

- Z. Luo, T. Lu, J. Liu, A reduced mechanism for ethylene/methane mixtures with excessive NO enrichment, Combust. Flame 158 (2011) 1245-1254.

- M. Frenklach, Method of moments with interpolative closure, Chemical Engineering Science 57 (2002) 2229-2239.

- Saggese, S. Ferrario, J. Camacho, A. Cuoci, A. Frassoldati, E. Ranzi, H. Wang, T. Faravelli, Kinetic modeling of particle size distribution of soot in a premixed burner-stabilized stagnation ethylene flame, Combust. Flame 162 (2015) 3356-3369.

- R.L.S. David G. Goodwin, Harry K. Moffat, and Bryan W. Weber, Cantera: An object-oriented software toolkit for chemical kinetics, thermodynamics, and transport processes, https://www.cantera. [CrossRef]

- T.S. Wang, R.A. Matula, R.C. Farmer, Combustion kinetics of soot formation from toluene, Symposium (International) on Combustion 18 (1981) 1149-1158.

- Y. Zhang, Y. Huang, F. Wang, Y. Wu, Y. Xiao. Influence of Multi-Source Vortex Structure on the Mixing of Fuel/Air. In: editor^editors. 2010 Asia-Pacific Power and Energy Engineering Conference; 28-31 March 2010 2010. p. 1-4.

- N. Chakraborty, Influence of Thermal Expansion on Fluid Dynamics of Turbulent Premixed Combustion and Its Modelling Implications, Flow, Turbulence and Combustion 106 (2021) 753-848.

- Denet, V. Bychkov, Low vorticity and small gas expansion in premixed flame, Combust. Sci. Technol. 177 (2005) 1543-1566.

- P. Liu, C. Chu, I. Alsheikh, S.R. Gubba, S. Saxena, O. Chatakonda, J.W. Kloosterman, F. Liu, W.L. Roberts, Soot production in high pressure inverse diffusion flames with enriched oxygen in the oxidizer stream. Combustion and Flame, 2022. 245: p. 112378.

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).