1. Introduction

Natural products are important sources of new drug discoveries and play an important role in drug development [

1]. Synthetic molecules and natural products would practically resolve the long-standing medication design challenges. The development of active antimicrobials from natural products would be aided from modern chemistry and bioinformatics approaches [

2]. 35% of medications available in the market are reported to be derived from natural materials, with 25% of those accounted for plants [

3]. Natural products, particularly antibiotics and therapeutic agents of cancer with their distinctive benefits are essential in the process of novel drug discovery [

4].

However, bacterial infections have a significant impact on public health. Treatment of bacterial infections are getting more difficult as a result of an increase in the number of patients with complex underlying problems and microorganisms resistant to current antimicrobial medications [

5]. These issues, as well as drug cytotoxicity and a limited therapeutic spectrum, have prompted the development of new antimicrobial drugs [

5]. One of the main reasons to discover new antimicrobial agents or to improve the efficacy already available antibiotics is the antimicrobial resistance (AMR), which is one of the world's most serious public health issues at present. Worldwide antibiotic resistance threatens our progress in healthcare, food production, and ultimately life expectancy Therefore, the identification of new antimicrobial agents is of immense need to save lives and protect health systems.

β-Lapachone is a natural compound isolated from the heartwood of lapacho tree (Tabebuia impetiginosa) found in different parts of South America [

6]. Numerous studies have demonstrated that β-lap has a variety of pharmacological actions, including anticancer [

7], anti-

Trypanosoma cruzi - the causative agent of Chagas disease [

8], antibacterial [

9], and antifungal properties. Having antifungal activity against azole-resistant

Candida spp. isolates, it not only inhibited the biofilm formation but disrupted the already formed mature biofilms. Cristian Salas et. al. used β -Lap to treat chagas disease, one of the most serious endemic disorders caused by

Trypanosoma cruzi and found that β -Lap inhibited epimastigote development in

trypanosoma cruzi cells and trypomastigote vitality in vitro [

8].

β -Lap possesses antibacterial properties against a variety of bacteria species, including

M. tuberculosis, its MDR clinical isolates, methicillin resistant

S. aureus (MRSA). β -Lap showed additive effect in combination with first line TB drugs and synergic effect with N-acetylcysteine against

M. tuberculosis H37Rv [

10]. In addition, it synergistically inhibited the growth of methicillin resistant

S. aureus (MRSA) in combination with fluoroquinolones, carbapenems, and beta lactams [

11]. Generation of hydrogen peroxide and superoxide anions in bacterial cells has been demonstrated as one of the mechanisms for the action of β -Lap [

12].

Nutrient limitation, slow growth, adaptive stress responses, and formation of persisted cells are hypothesized to constitute a multi-layered biofilm, which leads to the poor antibiotic penetration [

13] and thus difficult eradication of biofilm producers [

14]. It is believed that the reduced antibiotic susceptibility of bacteria in biofilms is thought to be due to a combination of poor antibiotic penetration, an altered microenvironment, adaptive responses, and the presence of bacterial persisted cells. Therefore, there is need to develop a novel antibiotic to inhibit the biofilm formation and to disrupt the formed biofilms, which would allow the cells to grow actively and thus might help the existing antibiotics to clear infections involving biofilms that are refractory to current treatments [

15].

2. Materials and methods

2.1. Solvents, media and chemicals used in this study

β -Lap was purchased from Sigma Aldrich and dissolved in dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO). Gram’s crystal violet, a bacteriological stain, was obtained from TITAN BIOTECH. Phosphate buffered saline (PBS) tablets were obtained from Sigma Aldrich®, Dorset, UK. Methanol (≥ 99.8 %) was purchased from Sigma-Aldrich® GmbH Chemie, Steinheim, France. Acetic acid (≥ 99.8%) was purchased from Sigma-Aldrich® GmbH Chemie, Steinheim, Germany. Six antibiotics belonging to different classes and potencies were purchased from different pharmaceutical companies. Gentamicin (10 µg) from BD BBL™ Sensi-Disc™, vancomycin (30 µg), amikacin (30 µg), tetracycline (30 µg), ciprofloxacin (5 µg) from Bioanalyse®, and amoxicillin (30 µg) from Oxoid™.

2.2. Bacterial strains used for antimicrobial susceptibility testing

Laboratory bacterial strains of Staphylococcus epidermidis, Pseudomonas aeruginosa ATCC 27853, Staphylococcus saprophyticus, Staphylococcus aureus, Pseudomonas, Shigella, Escherichia coli, Klebsiella pneumonia, Streptococcus mutans, Mycobacterium smegmatis, and Enterococcus faecalis grown in trypticase soy broth were tested for antibacterial activity of β -Lap. All strains are preserved as glycerol stocks in the freezer at −80°C.

2.3. Zone of inhibition

Agar well diffusion method is widely used to evaluate the antimicrobial activity of plants or microbial extracts. Wells of 6 mm diameter were punched aseptically with a sterile tip on TSA plates. Using aseptic techniques, inoculums of 0.5 McFarland were prepared by taking a colony from TSA plate into 2 ml of normal saline and mixing it thoroughly by vortexing. Subsequently, the bacterial suspension was diluted 100-fold by transferring 20 µL of the bacterial suspension in to 2mL of sterile normal saline. Above diluted bacterial suspensions were spread over the agar plate’s surface using a sterile cotton swab to get a uniform microbial growth on plates. 20 µL of 2.5 mM β-Lap dissolved in DMSO were dispensed into the wells of the plate, while for control 20 µL of DMSO was dispensed into separate wells. After 24 hr incubation, a ruler was used to measure the diameter of a clear zone around the well.

2.4. Minimum inhibitory concentration (MIC) by broth dilution method

MIC, the lowest concentration of antimicrobial agent that completely inhibits the growth of microorganism, was determined by broth dilution method. In brief, few individual colonies of a bacterial strain were suspended into 2ml of saline to an optical density of 0.5 McFarland. The culture was subsequently diluted 100-fold in trypticase soy broth. 180 µL of diluted culture was dispensed into the wells of 96-well plate of having periphery wells filled with 200 µL of distilled water to avoid evaporation during incubation period. The11th column was filled with 200 µL of sterile trypticase soy broth for the control of sterility of growth medium. Wells of the column 2 were reserved for control to which 20 µl of DMSO was added. The 20 μL of 5-fold serially diluted β -Lap were added to the wells of a row from 3rd column to 10th column. Working stocks of five-fold diluted β -Lap ranging from 10 mM – 0.000128 mM, including 5 mM stock were prepared in DMSO. For each bacterial strain, three wells per dilution of β -Lap were used. The plates were incubated for 24 hours at 37 ºC. The lowest concentration of the compound at which no visible growth was observed is considered as MIC for the bacterial strain tested.

2.5. Minimum bactericidal concentration by agar plate method

The minimum bactericidal concentration (MBC) is the lowest concentration of an antimicrobial at which microorganism is completely killed. A sterilized loop was used to streak the cultures from the wells of MIC up to the wells of highest concentration of β -Lap. The concentration of β –Lap where no growth was detected is considered as MBC for the bacterial strain tested.

2.6. Microplate alamar blue assay (MABA)

The Microplate AlamarBlue® assay (MABA) is a sensitive, rapid, and nonradiometric method, which evaluates cellular health and offers the potential for screening large numbers of antimicrobial compounds. The major advantage of MABA is that growth can be evaluated fluorometrically, spectrophotometrically or visually. In brief, 180 µL of aforementioned 100-fold diluted culture of a bacterial strain in trypticase soy broth containing 1x alamar blue were dispensed into the wells of 96-well plate. 20 µL of β-Lap at its MIC and 2xMIC were dispensed in triplicate culture wells. For positive control and medium sterility 20 µL of DMSO were added to triplicate wells of culture and growth media, respectively. The periphery wells were filled with 200 µL of water to avoid evaporation of the well content. The plate was sealed with breathable sealing film (Sigma Aldrich) to allow exchange of gasses. The plate was incubated in FLUOstar® Omega microplate reader overnight. The fluorescent readings (excitation/emission maxima at 544/590 nm) were recorded after every 30 min. The average values of blank corrected fluorescence units were plotted against time using Microsoft Excel software. Standard deviations were calculated by Microsoft Excel software.

2.7. Antibiotic activity assay and synergism

To investigate the synergetic effect of the β -Lap compound for several commercial antibiotics, the 0.5 McFarland of bacterial suspension was diluted 100-fold in normal saline and the resulting bacterial suspension was streaked on TSA plates using a sterile cotton swab to get a uniform lawn of microbial colonies. The antibiotic disks (diameter of 6mm) were placed on the surface of inoculated plate to determine its inhibition zone size. For synergy 20 µl of β -Lap from 2.5 mM working stock were dispensed onto the antibiotic discs. The size of inhibition zone was measured in millimetres after 18-24 hours of incubation at 37oC.

2.8. Crystal violet biofilm assay

180 µL of 100-fold diluted bacterial suspension obtained from 0.5 McFarland were dispensed into the wells of 96-well plate. To determine the MBIC, 20 µl of β -Lap compound at 5 fold dilutions ranging from 0.5 mM to 0.0016 were dispensed in triplicate wells. For the control 20 µL of DMSO were dispensed into the triplicate wells. After 24 hours of incubation under static conditions of growth at 37°C, the wells were rinsed thrice with sterile PBS (phosphate-buffered saline, pH 7.4) to remove the non-adherent bacteria. The cells on the walls of wells were fixed with 99% (v/v) methanol for 15 minutes. After discarding methanol wells were dried in laminar flow for 5 min. The attached biofilm cells were stained with 0.5% crystal violet (Sigma-Aldrich) for 5 min at room temperature. The excess stain was removed by washing thrice with distilled water and the crystal violet-bound cells were solubilized in 33 % acetic acid. The absorbance readings at 570 nm were taken in FLUOstar® Omega microplate reader and the average of the blank corrected values were plotted using Microsoft Excel. For mature biofilm formation, the cultures were allowed to grow statically for 24 or 48 hr at 37oC. The biofilms formed were washed thrice with PBS and incubated with sterile growth medium containing β –Lap. 24 hours later the biofilms were washed, stained and estimated as described above.

2.9. Colony forming units (CFU)

CFU of the cultures treated with DMSO or β -Lap were enumerated by plating 100 µl of 10-fold dilutions on nutrient agar plates. The colony count was calculated by the formula, CFU/ml= (Number of colonies in 0.1 ml of culture plated/0.1) x dilution factor. For hydrogen peroxide sensitivity assay, cells treated overnight with 1/5xMIC were pelleted down, washed thrice with 1xPBS and re-suspended in 1xPBS containing 20 mM H2O2. After one hour of incubation at 37oC, the cell suspensions were serially diluted and 100 uL were plated on nutrient agar plates. CFUs/ml ere enumerated from DMSO treated and β –Lap treated samples for each strain.

Catalase activity assay: For catalase activity, the bacterial cultures containing β –Lap at its 1/100xMIC were incubated overnight in a shaking incubator at 200 RPM. For control, bacterial cultures in presence of DMSO were incubated under similar conditions. The 200 µL of 3% H2O2 were dispensed into one ml of the overnight culture in a glass tube and mixed immediately. The height of air bubble column formed above the culture was measured using a ruler. The experiment was setup in triplicates for each strain and the average length of the air bubble column was plotted using Microsoft Excel.

Molecular modeling: Modeled

Pseudomonas aeruginosa catalase complexed with β–Lapachone using molecular docking approach. Coordinates of crystal structure of

P. aeruginosa catalase (KatA tetramer, PDB code: 4e37, resolution 2.53 Å) with heme and NADPH bound was downloaded from Protein Data Bank (

https://www.rcsb.org/structure/4E37). Bound ligands and water molecules were removed for docking studies. β–Lapachone structure (.sdf file) were downloaded from PubChem database (

https://pubchem.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/compound/3885). To generate KatA-ligand complexes CB-Dock2, cavity guided blind docking, web server available at

https://cadd.labshare.cn/cb-dock2/ (https://doi.org/10.1093/nar/gkac394) was used. Modeled KatA-ligand complexes were analyzed using BIOVIA Discovery Studio Visualizer, v21, 2021, Protein-Ligand Interaction Profiler available at

https://plip-tool.biotec.tu-dresden.de/plip-web/plip/index and PyMOL available at

https://pymol.org to identify biologically relevant KatA-ligand complexes.

2.10. Statistical analysis

Excel of Microsoft Office was used to perform the statistical analysis of data. All the data sets were obtained in triplicates from more than one biological replicates and the values were interpreted as means standard deviation (SD).

3. Results

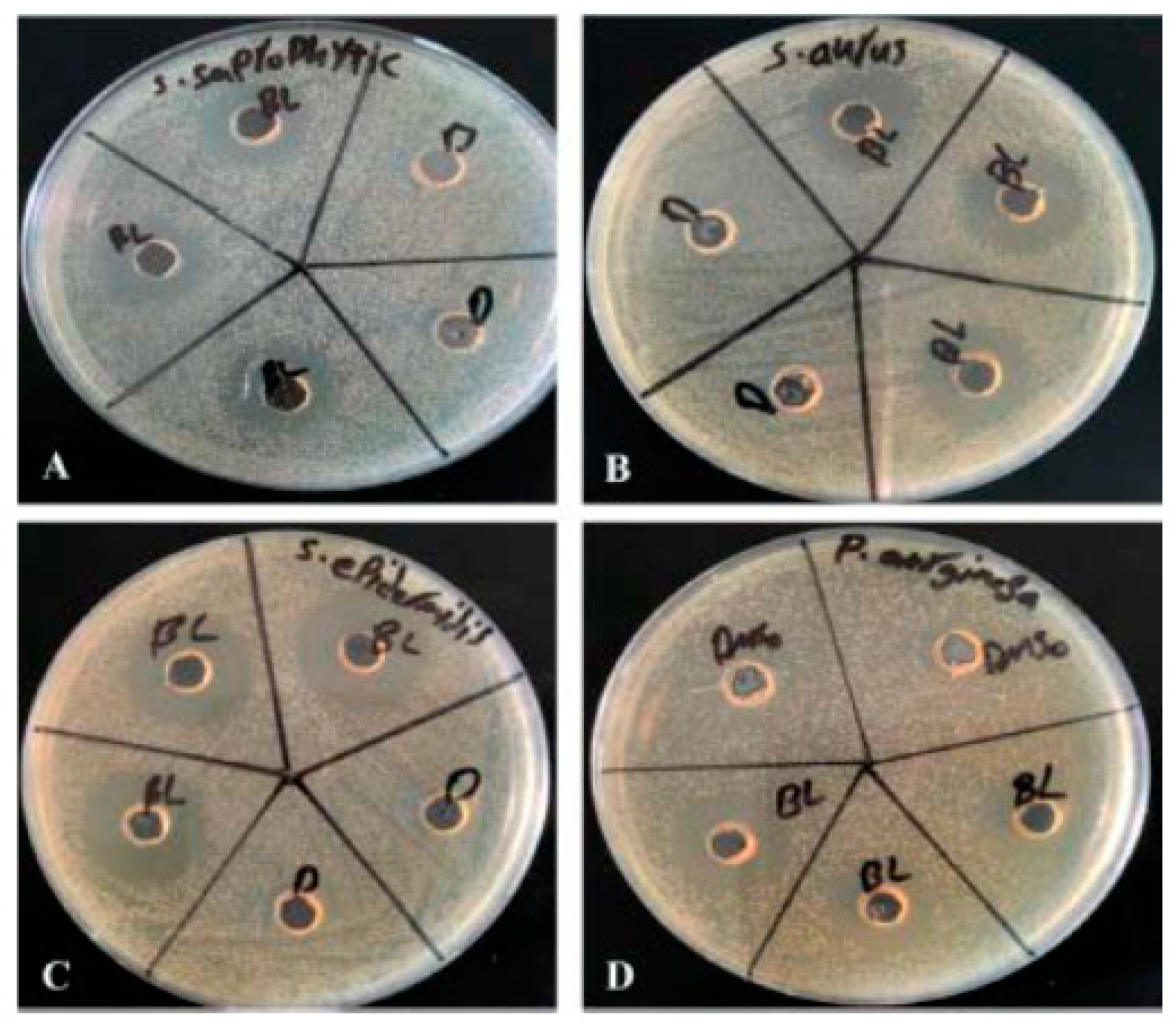

3.1. Antibacterial activity of β –Lap

Eleven bacterial strains including nine laboratory strains and two reference strains

viz Pseudomonas aeruginosa (ATCC 27853),

Streptococcus mutans (ATCC 25175),

Staphylococcus saprophyticus, Staphylococcus aureus, Staphylococcus epidermidis,

Pseudomonas spp, Shigella, Escherichia coli, Klebsiella pneumonia, Mycobacterium smegmatis, and

Enterococcus faecalis were screened for susceptibility to β –Lap by well-diffusion method. It was found that out of eleven bacterial strains tested only four

, S. epidermidis, S. aureus S. saprophyticus, and

P. aeruginosa (ATCC 27853) were susceptible to β –Lap. A clear zone of growth inhibition) (17.7 ± 1.7 mm to 26.7 ± 1.2 mm in diameter) was observed against the susceptible strains (

Figure 1 and Table 1). In order to determine the minimum concentration of β –Lap to inhibit the growth of aforementioned bacterial strains, the strains were treated with five-fold dilutions of β –Lap of final concentrations ranging from 1 mM to 0.0000128 mM. The MIC was found to be 0.2 mM for

S. saprophyticus and

S. aureus and 0.04 mM for

S. epidermidis and

P. aeruginosa (ATCC 27853). As expected, the MBC was higher than MIC (Table 1). These results suggested that

S. epidermidis and

P. aeruginosa were comparatively more susceptible to β –Lap than

S. saprophyticus and

S. aureus.

To further confirm the bactericidal effect of the β –Lap on these strains, CFUs were enumerated after bacterial cells were treated individually with four concentrations (½ MIC, MIC, 2xMIC, and 4xMIC ) of β –Lap. For control bacterial strains were treated with DMSO under similar conditions. It was evident that the growth of bacterial strains decreased in a dose dependent manner of β –Lap (Supplementary Figure 1). These results suggested that the β -Lap is a potent antimicrobial against all the four bacterial strains tested.

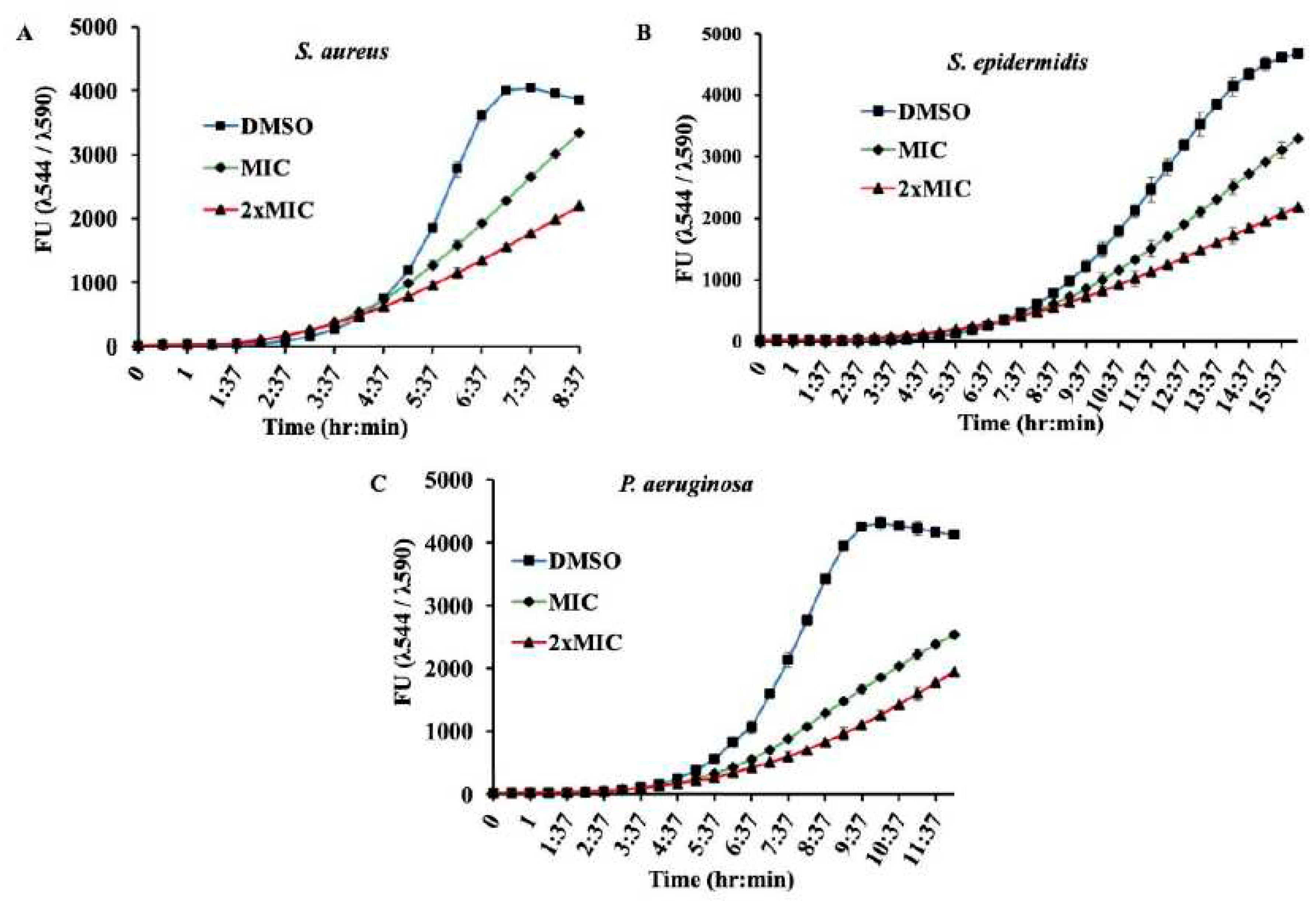

3.2. Growth kinetics of bacterial strains in presence of β -Lap

MABA, an adequate method for testing antimicrobial activity, was used to monitor the growth of β -Lap susceptible bacterial strains in continued presence of different concentrations of β -Lap. Alamar blue, a growth indicator, is a fluorescent dye that changes its colour from blue to pink by the reduced environment of the growing cells. 0.5 McFarland bacterial cultures diluted hundred times in trypticase soy broth containing 1x alamar blue were incubated with β -Lap at its MIC and 2xMIC. For control, the cultures were incubated with DMSO only. Growth media containing 1x alamar blue was used as a blank for its sterility. The growth at regular intervals of 30 min was monitored in FLUOstar® Omega microplate reader over the time of 16 hours. Blank corrected average fluorescence units (Ex

560/Em

590) plotted against the time for each strain (

Figure 2) showed that all the four strains tested had a normal pattern of growth in presence of DMSO. However, a decrease in growth was observed for all the three strains tested with the corresponding increase in the concentration of compound β -Lap from 1xMIC to 2xMIC.

3.3. Antibacterial activity of β -Lap in combination with commercial antibiotics

In order to determine the effect of the β -Lap on antibacterial activity of commercial antibiotics against S. saprophyticus, S. aureus, S. epidermidis, and P. aeruginosa, 2.5 mM β -Lap was added to the discs impregnated with antibiotics and subsequently placed on agar plates already streaked uniformly with a bacterial culture. The zone of inhibition measured after 24 hr (Table 2) indicated that the antibacterial activity of tetracycline, amoxicillin, and vancomycin in combination with β -Lap increased against S. epidermidis (zone size 8mm > antibiotic alone). Same was the case with ciprofloxacin and amoxicillin against P. aeruginosa and S. saprophyticus, respectively. Like the antibacterial activity of tetracycline against S. aureus, the antibacterial activity of gentamycin, tetracycline ciprofloxacin and amoxicillin in association with β –Lap was moderate against S. saprophyticus (zone size 5mm > antibiotic alone). In other settings, the combination of β -Lap with the antibiotics either mildly enhanced their antibacterial activity (zone size 2-4 mm > antibiotic alone) or had neither additive nor indifferent effect against the bacterial strains tested (Table 2).

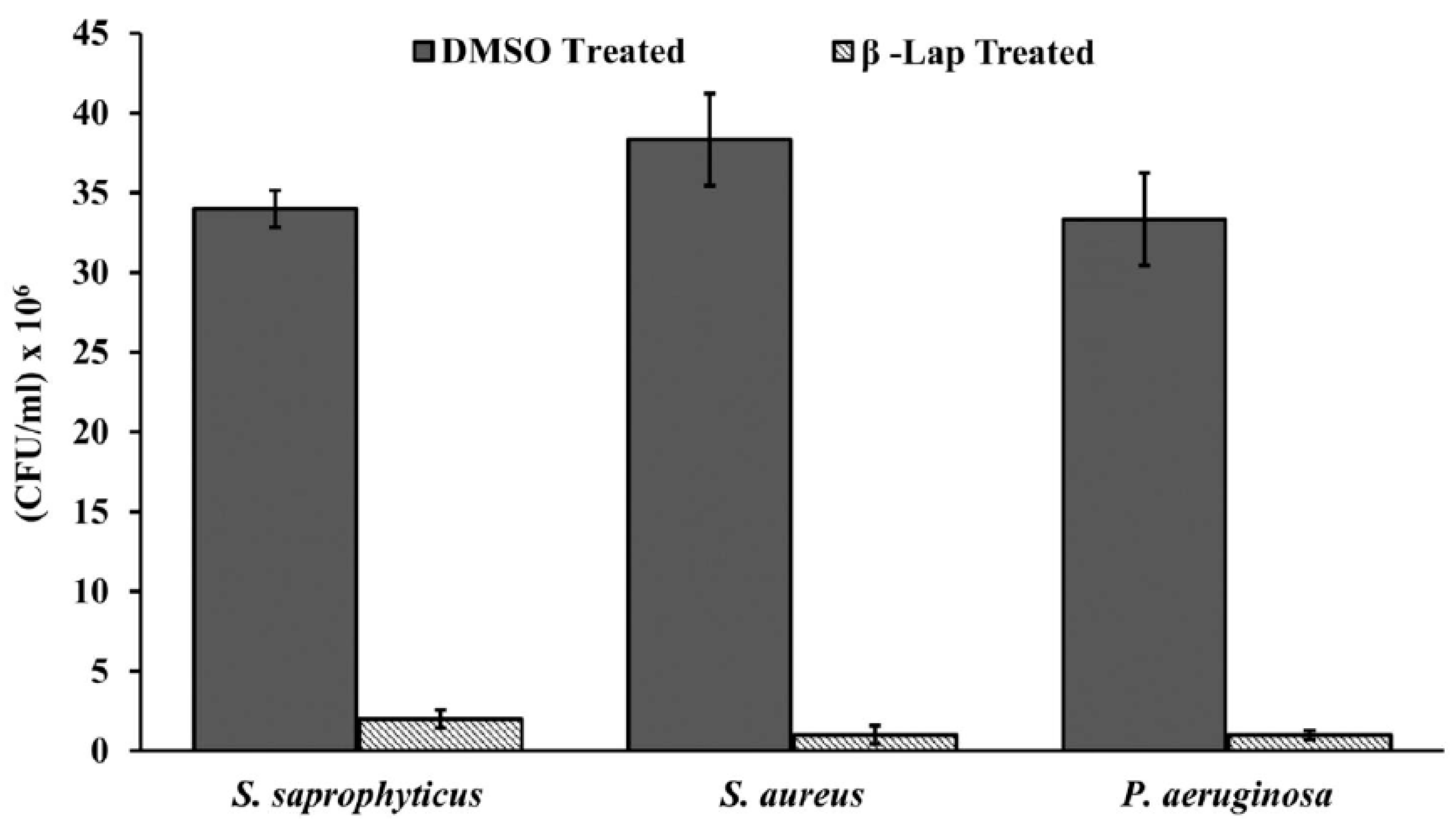

β -Lap treated cells are sensitive to H2O2 treatment. Since all the four susceptible bacterial strains are aerobic, we assume that the oxidative stress generated by the β –Lap might be the cause for its antibacterial activity. To investigate this assumption, the β –Lap treated cells were subjected to H

2O

2 treatment. For the control, DMSO treated cells were subjected to same treatment under similar conditions. CFUs enumerated showed that the β –Lap treated cells were very sensitive to H

2O

2 stress (

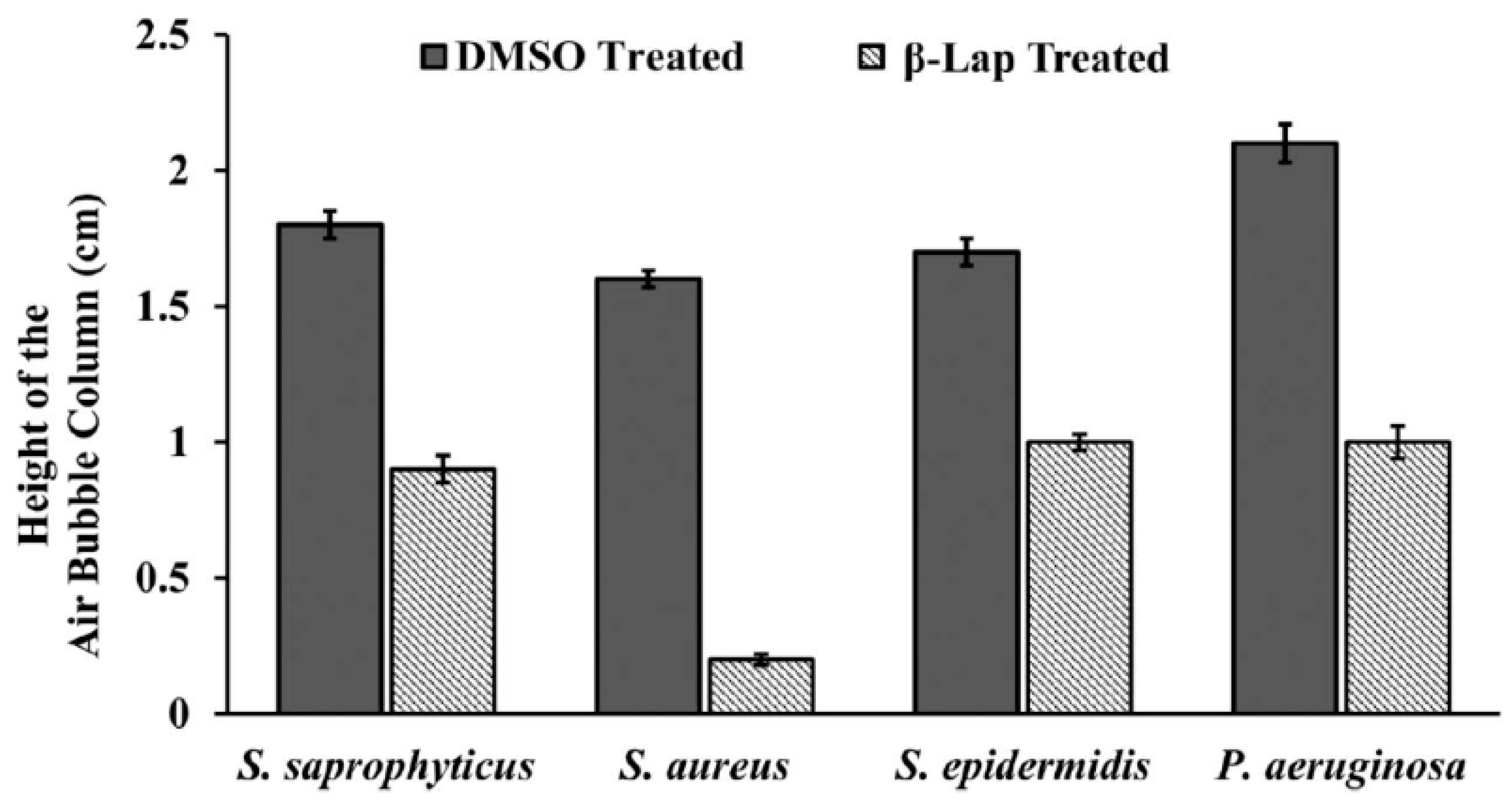

Figure 3). These results suggest that β –Lap treatment makes cells susceptible to oxidative stress. Since, all pathogens have mechanism in place to survive under oxidative stress of macrophages in human host. The catalase of the aerobic bacteria is one of the components of defensive mechanism to combat host’s stress. Therefore, we performed another experiment to determine whether the catalase activity of the bacterial strains tested is affected. It was found that the catalase activity of β –Lap treated cells was significantly reduced compared to DMSO treated control cells (

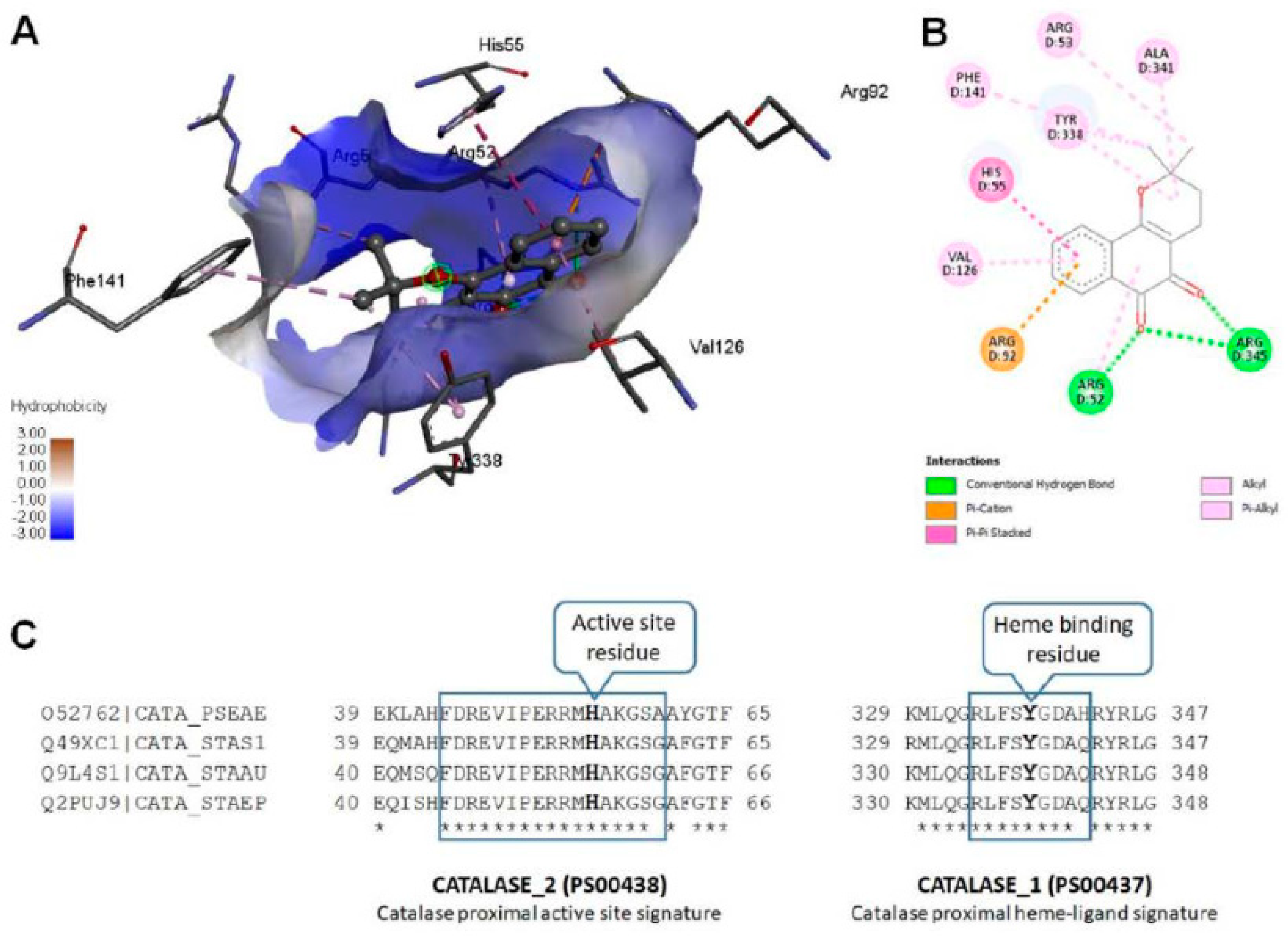

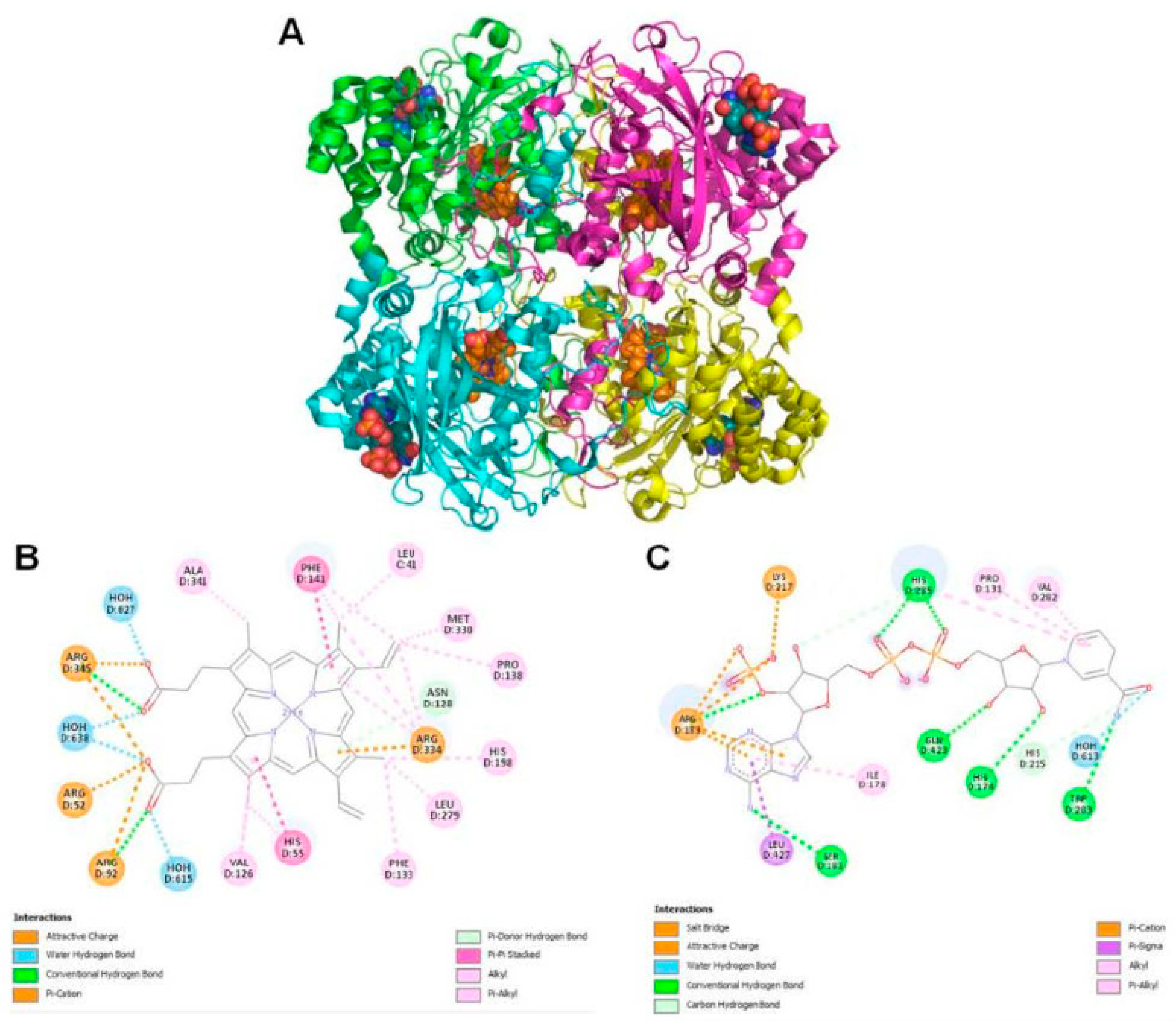

Figure 4, Supplementary Figure 2). More interestingly, we noticed that β –Lap exhibited a very strong antibacterial activity in shaking condition. The possible reason for reduced catalase activity of β –Lap treated cells could be either inhibition of catalase or reduction in its level, which needs further investigation by biochemical and molecular approaches. However, bioinformatic analysis predicted that β –Lap might inhibit the catalase by binding to it directly. Using bioinformatic approach, modeled KatA-ligand interactions (

Figure 5) were analyzed and compared with the crystal structure of

P. aeruginosa catalase complexed with heme and NADPH (

Figure 6). Biologically relevant KatA-ligand complexes shown in

Figure 5 and the details tabulated in Table 3 suggest that β–Lap can inhibit

P. aeruginosa catalase KatA activity by interacting with catalase proximal active site and heme binding site.

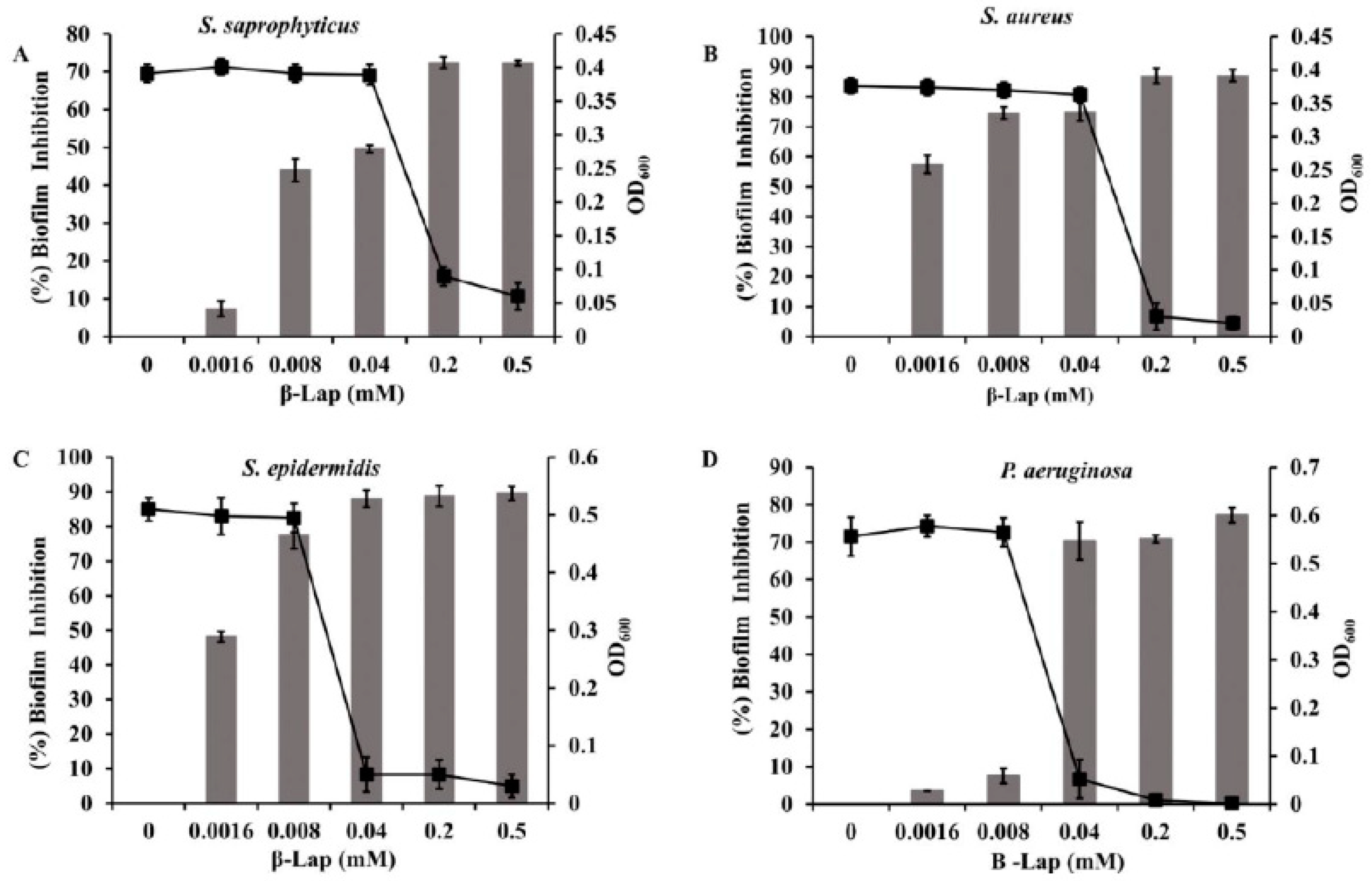

3.4. β-Lap inhibits biofilm formation

To investigate the effect of β -Lap on the biofilm formation of

S. saprophyticus,

S. aureus,

S. epidermidis and

P. aeruginosa, the cells were incubated with five-fold increasing concentrations (0.0016 mM to 0.2 mM), including 0.5 mM of β –Lap for 24 hours at 37

oC. For control, the cells were treated with DMSO under similar conditions. The biofilms were developed by crystal violet method and quantified by measuring absorbance at 570 nm. It is clear from

Figure 7 that the biofilm formation of the strains inhibited in a dose dependent manner (Supplementary Figure 3). A significant inhibition of biofilm formation was observed in

S. saprophyticus (50%) and

S. aureus (75%) at 0.04 mM concentration of β –Lap, without effecting their growth. Inhibition in growth was observed at concentration higher than 0.04 mM. Therefore 0.04 mM was considered as MBIC (minimum biofilm inhibition concentration) for the above-mentioned strains as an ideal anti-biofilm agent should not affect the growth of bacteria. Similarly, 0.008 mM concentration of β –Lap was fixed as MBIC for

S. epidermidis, on which 78% inhibition in biofilm formation was observed. However, β –Lap exhibited minimal inhibitory effect (less than 50%) on biofilm formation of

P. aeruginosa. The growth of all strains measured by absorbance readings at 600 nm suggests that the cells were metabolically active at sub-MBIC concentrations. These results suggest that the compound has promising anti-biofilm properties.

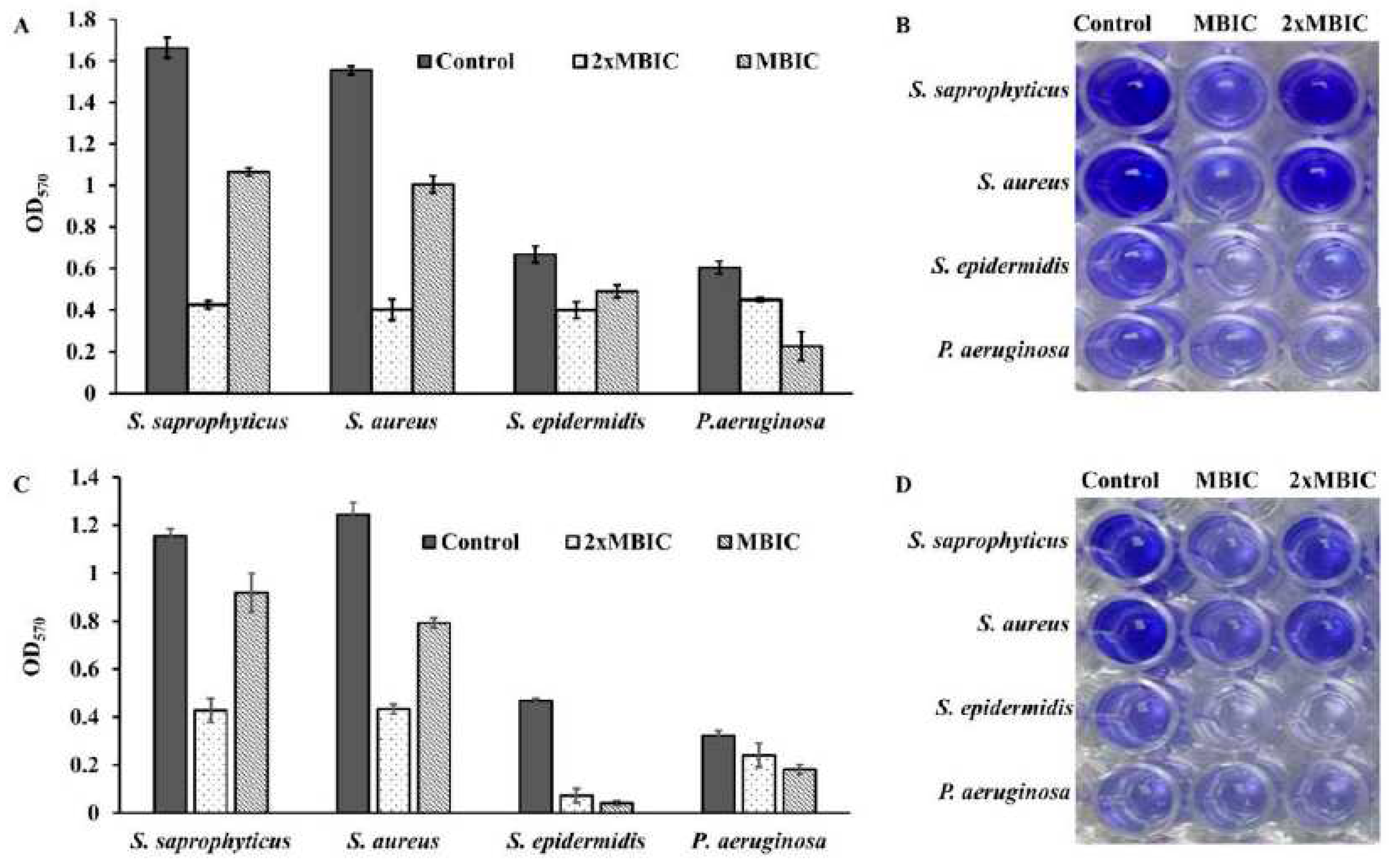

We further explored, whether β –Lap disrupts the mature biofilms of these strains. For biofilm disrupting ability, the bacterial cultures were grown for 24 and 48 hours to allow the bacterial cells form mature biofilms. Free planktonic cells were washed off and the biofilms were treated further for 24 hours with 1xMBIC and 2xMBIC of β –Lap in the same growth media. The remaining biofilms, which were resistant to β –Lap under given conditions, were quantified. It is clear from

Figure 8 that both the mature and extra mature biofilms were disrupted by β –Lap. Among the bacterial strains tested, the mature and ultra-mature biofilms of

S. saprophyticus and

S. aureus were highly sensitive to β –Lap. Contrarily, the mature and ultra-mature biofilms of

P. aeruginosa were least susceptible to β –Lap. Interestingly, the ultra-mature biofilms of

S. epidermidis showed highest sensitivity to β –Lap. However, it is worth noting that the biofilm inhibition activity of the compound was more prominent than its biofilm disruption capability.

4. Discussion

In recent decades the increase in infectious cases caused by bacterial species and the resulting disproportionate use of antimicrobials led to the development of resistance to antimicrobial drugs [

16]. To overcome such hurdles, scientists gained interest in recent decade to identify new antimicrobials. For which plants and their secondary metabolites are a prospective source of bioactive molecules as potential therapeutic agents [

17]. Naphthoquinones, a group of secondary metabolites commonly found in higher plants have great structural diversity and biological activity.

In the present study, we evaluated the ability of β –Lap, a naphthoquinone, to inhibit the growth of several pathogenic bacteria. Out of ten bacterial strains screened, only four

S. saprophyticus, S. aureus,

S. epidermidis, and

P. aeruginosa were susceptible to the tested concentration (2.5mM) of β –Lap with zone of inhibition ranging from 17.7 mm to 26.7 mm (Table 1). Among them

S. epidermidis, S. saprophyticus, and

P. aeruginosa showed highest zone of inhibition, while

S. aureus comparatively showed lower zone of inhibition. As expected, a positive correlation was observed between inhibition zone sizes and corresponding MIC values. To further evaluate the bactericidal activity of β –Lap, cells were treated with increasing concentration of β –Lap (1/2xMIC, MIC, 2xMIC and 4xMIC) and as expected CFUs enumerated decreased in a dose dependent matter, suggesting that the β -Lap compound was bactericidal in nature (Supplementary Figure 1). In addition to this endpoint analysis, growth kinetics of bacterial strains in presence of 1x and 2xMIC of β -Lap confirmed the decrease in growth rate in a dose-depended manner (

Figure 2). Though antibacterial activity of the β -Lap has not been studied in detail, our data was consistent to the other previous observations. In one of the studies, β -Lap encapsulated in liposomes inhibited different MRSA isolates [

9]. In another study it inhibited the methicillin sensitive and resistant strains of

S. aureus and methicillin resistant strains of

S. epidermidis and

S. haemolyticus [

18]. Among the naphthoquinones (lapachol, α-lapachone, and β-lapachone) tested against several strains of MRSA, β-lapachone exhibited not only antibacterial activity but synergic activity in association with commercial antibiotics [

11]. Since in the present study all the β –Lap susceptible strains are aerobes and Gram positive, we suspected that the activity of catalases might be compromised in such strains. In support of this notion, we assayed the sensitivity of β –Lap treated cells towards H

2O

2 treatment. it is evident from the

Figure 3 and

Figure 4 that the cells treated with β –Lap were very sensitive to H

2O

2 treatment due to the large reduction in their catalase activity. The cause of reduction of the catalase activity needs to be investigated, which is our future goal of research. It could be either due to the reduction in the level of catalase or inhibition of its catalytic activity. Molecular modelling predicted the inhibition of catalase activity by binding to the proximal active site and heme binding sites of the enzyme.

The combinational therapy of the new drugs with already existing commercial antimicrobials is an important strategy in the search of more effective antimicrobial agents for treating microbial infections. This can potentially increase efficacy, reduce toxicity, cure faster, prevent the emergence of resistance, and provide a broader spectrum of activity than mono therapy regimens. Combinational effect of β -Lap with other antibiotics on the bacterial strains tested (Table 2) showed that it has a potential to increase the activity of some drugs in vitro. These results are in agreement with the synergistic effects between β -Lap and conventional antimicrobials against methicillin resistant

Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA) strains [

11]. It needs to be seen whether the β -Lap will have same effect in combination with antibiotics in vivo.

Bacterial cells being substantially more resistant to drugs and host immune responses in biofilms pose a great challenge to chemotherapy of the infectious diseases. There is poor antibiotic penetration and slow growth due to nutrient limitation, which makes cells less prone to antibiotics. Hence there is a need to develop new drugs that could penetrate well and kill the bacterial cells protected by multi-layered extracellular polymeric matrix.

Four bacterial strains

S. saprophyticus, S. aureus, S. epidermidis, and

P. aeruginosa (ATCC 27853) were tested to investigate the effect of β -Lap on their biofilm formation. It was found that the biofilm formation in the tested strains significantly inhibited (50-80% biofilm inhibition) at MBIC. More importantly no inhibition of growth occurred to the strains at MBIC (

Figure 7). Not only β –Lap inhibited biofilm formation but disrupted the mature biofilms of these bacteria.

Our results of antibacterial and antibiofilm activities of β –Lap corroborates well with the study of Fernandes AWC, et. al., wherein the authors showed that β-Lapachone and Lapachol Oxime (semi-synthetic derivatives of Lapachol) exhibited antimicrobial and anti-biofilm potential against clinical isolates of

S. aureus [

19].

The results altogether certainly confirm that the β -Lap exhibited strong antibacterial and antibiofilm activities as well as the synergistic effect on commercial antibiotics. Therefore, β -Lap could be a drug of choice to be used in treating the bacterial infections, but its activity in vivo needs to be investigated, which demands further research.

5. Conclusions

Taken together, our data suggested that β -Lap is a promising novel antibacterial agent against clinically important microorganisms by inhibiting the catalase either at its activity or transcriptional level.

Acknowledgement

The Deanship of Scientific Research, King Khalid University, Abha, supported this work, under grant no. RGP.1/356/43

References

- Jones WP, Chin YW, Kinghorn AD. The role of pharmacognosy in modern medicine and pharmacy. Curr Drug Targets. 2006 Mar;7(3):247–64. [CrossRef]

- Rodrigues T, Reker D, Schneider P, Schneider G. Counting on natural products for drug design. Nat Chem. 2016 Jun;8(6):531–41.

- Calixto JB. The role of natural products in modern drug discovery. An Acad Bras Ciênc. 2019;91(suppl 3):e20190105. [CrossRef]

- Gong Q, Hu J, Wang P, Li X, Zhang X. A comprehensive review on β-lapachone: Mechanisms, structural modifications, and therapeutic potentials. Eur J Med Chem. 2021 Jan;210:112962. [CrossRef]

- Tetz G, Tetz V. In vitro antimicrobial activity of a novel compound, Mul-1867, against clinically important bacteria. Antimicrob Resist Infect Control. 2015 Dec;4(1):45. [CrossRef]

- de Almeida ER, da Silva Filho AA, Dos Santos ER, Correia Lopes CA. Antiinflammatory action of lapachol. J Ethnopharmacol. 1990 May;29(2):239–41.

- Ferraz da Costa DC, Pereira Rangel L, Martins-Dinis MMD da C, Ferretti GD da S, Ferreira VF, Silva JL. Anticancer Potential of Resveratrol, β-Lapachone and Their Analogues. Molecules. 2020 Feb 18;25(4):893. [CrossRef]

- Salas C, Tapia RA, Ciudad K, Armstrong V, Orellana M, Kemmerling U, et al. Trypanosoma cruzi: Activities of lapachol and α- and β-lapachone derivatives against epimastigote and trypomastigote forms. Bioorg Med Chem. 2008 Jan;16(2):668–74. [CrossRef]

- Cavalcanti IMF, Pontes-Neto JG, Kocerginsky PO, Bezerra-Neto AM, Lima JLC, Lira-Nogueira MCB, et al. Antimicrobial activity of β-lapachone encapsulated into liposomes against meticillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus and Cryptococcus neoformans clinical strains. J Glob Antimicrob Resist. 2015 Jun;3(2):103–8. [CrossRef]

- Ieque AL, Carvalho HC de, Baldin VP, Santos NC de S, Costacurta GF, Sampiron EG, et al. Antituberculosis Activities of Lapachol and β-Lapachone in Combination with Other Drugs in Acidic pH. Microb Drug Resist. 2021 Jul 1;27(7):924–32. [CrossRef]

- Macedo L, Fernandes T, Silveira L, Mesquita A, Franchitti AA, Ximenes EA. β-Lapachone activity in synergy with conventional antimicrobials against methicillin resistant Staphylococcus aureus strains. Phytomedicine. 2013 Dec;21(1):25–9. [CrossRef]

- Cruz FS, Docampo R, Boveris A. Generation of Superoxide Anions and Hydrogen Peroxide from β-Lapachone in Bacteria. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1978 Oct;14(4):630–3. [CrossRef]

- Wu H, Moser C, Wang HZ, Høiby N, Song ZJ. Strategies for combating bacterial biofilm infections. Int J Oral Sci. 2015 Mar;7(1):1–7. [CrossRef]

- Hengzhuang W, Wu H, Ciofu O, Song Z, Høiby N. Pharmacokinetics/Pharmacodynamics of Colistin and Imipenem on Mucoid and Nonmucoid Pseudomonas aeruginosa Biofilms. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2011 Sep;55(9):4469–74. [CrossRef]

- Stewart PS. Mechanisms of antibiotic resistance in bacterial biofilms. Int J Med Microbiol. 2002;292(2):107–13. [CrossRef]

- Llor C, Bjerrum L. Antimicrobial resistance: Risk associated with antibiotic overuse and initiatives to reduce the problem. Ther Adv Drug Saf. 2014;5(6):229–41. [CrossRef]

- Evans SM, Cowan MM. Plant products as antimicrobial agents. Cosmet Drug Microbiol. 2016;12(4):205–31.

- Pereira EM, Machado T de B, Leal ICR, Jesus DM, Damaso CR de A, Pinto AV, et al. Tabebuia avellanedae naphthoquinones: activity against methicillin-resistant staphylococcal strains, cytotoxic activity and in vivo dermal irritability analysis. Ann Clin Microbiol Antimicrob. 2006 Jan;5(1):5. [CrossRef]

- Fernandes AWC, dos Anjos Santos VL, Araújo CRM, de Oliveira HP, da Costa MM. Anti-biofilm Effect of β-Lapachone and Lapachol Oxime Against Isolates of Staphylococcus aureus. Curr Microbiol. 2020 Feb;77(2):204–9. [CrossRef]

Figure 1.

Zone of inhibition of susceptible strains. 20 μl each of β – Lap (2.5 mM) and DMSO were dispensed in triplicate and duplicate wells, respectively, of the plates uniformly streaked with bacterial suspension of A) S. saprophyticus, B) S. aureus, C) S. epidermidis, and D) P. aeruginosa (ATCC 27853).

Figure 1.

Zone of inhibition of susceptible strains. 20 μl each of β – Lap (2.5 mM) and DMSO were dispensed in triplicate and duplicate wells, respectively, of the plates uniformly streaked with bacterial suspension of A) S. saprophyticus, B) S. aureus, C) S. epidermidis, and D) P. aeruginosa (ATCC 27853).

Figure 2.

Growth of bacterial strains in presence of β –Lap: The growth of A) S. aureus, b) S. epidermidis, and C) P. aeruginosa was monitored in presence of MIC and 2xMIC of β -Lap by recording fluorescence readings at 30 min intervals using alarm blue as a growth indicator.

Figure 2.

Growth of bacterial strains in presence of β –Lap: The growth of A) S. aureus, b) S. epidermidis, and C) P. aeruginosa was monitored in presence of MIC and 2xMIC of β -Lap by recording fluorescence readings at 30 min intervals using alarm blue as a growth indicator.

Figure 3.

β -Lap treated cells are sensitive to H2O2: Bacterial cultures individually treated with DMSO and β -Lap were subjected to H2O2 stress. The CFUs enumerated post-H2O2 stress were plotted.

Figure 3.

β -Lap treated cells are sensitive to H2O2: Bacterial cultures individually treated with DMSO and β -Lap were subjected to H2O2 stress. The CFUs enumerated post-H2O2 stress were plotted.

Figure 4.

Catalase inhibition in β –Lap treated cells: The cells of the bacterial strains individually treated with DMSO (gray columns) and β –Lap (striated columns) were assayed for catalase production by measuring the height of air bubble column after the addition of H2O2.

Figure 4.

Catalase inhibition in β –Lap treated cells: The cells of the bacterial strains individually treated with DMSO (gray columns) and β –Lap (striated columns) were assayed for catalase production by measuring the height of air bubble column after the addition of H2O2.

Figure 5.

(A) Modeled Pseudomonas aeruginosa catalase (KatA tetramer, PDB code: 4e37) complexed with β–Lapachone. For clarity shown only β–Lapachone (ball-and-stick presentation) interaction with one chain (4e37, chain D) of P. aeruginosa catalase. (B) Modeled non-covalent interactions between β–Lapachone and KatA. (C) Conserved ligand binding sites (PROSITE ACs: PS00437 and PS00438) of catalase (KatA) from Pseudomonas aeruginosa (UniProtKB AC: O52762), Staphylococcus saprophyticus (UniProtKB AC: Q49XC1), Staphylococcus aureus (UniProtKB AC: Q9L4S1) and Staphylococcus epidermidis (UniProtKB AC: Q2PUJ9).

Figure 5.

(A) Modeled Pseudomonas aeruginosa catalase (KatA tetramer, PDB code: 4e37) complexed with β–Lapachone. For clarity shown only β–Lapachone (ball-and-stick presentation) interaction with one chain (4e37, chain D) of P. aeruginosa catalase. (B) Modeled non-covalent interactions between β–Lapachone and KatA. (C) Conserved ligand binding sites (PROSITE ACs: PS00437 and PS00438) of catalase (KatA) from Pseudomonas aeruginosa (UniProtKB AC: O52762), Staphylococcus saprophyticus (UniProtKB AC: Q49XC1), Staphylococcus aureus (UniProtKB AC: Q9L4S1) and Staphylococcus epidermidis (UniProtKB AC: Q2PUJ9).

Figure 6.

(A) Crystal structure of Pseudomonas aeruginosa catalase (KatA tetramer, PDB code: 4e37) complexed with Heme and NADPH. All four chains are represented as cartoon with different colors and bound ligands presented as spheres (Heme carbons as blue and NADPH carbons as orange). (B) Heme and (C) NADPH interactions with KatA.

Figure 6.

(A) Crystal structure of Pseudomonas aeruginosa catalase (KatA tetramer, PDB code: 4e37) complexed with Heme and NADPH. All four chains are represented as cartoon with different colors and bound ligands presented as spheres (Heme carbons as blue and NADPH carbons as orange). (B) Heme and (C) NADPH interactions with KatA.

Figure 7.

Inhibition of biofilm formation by β –Lap: The growth and the biofilms formed by bacterial cultures at different concentration of β –Lap were estimated by crystal violet absorbance at 570 nm and optical density at 600 nm respectively. The calculation for % inhibition of biofilm formation is discussed in material and methods section

Figure 7.

Inhibition of biofilm formation by β –Lap: The growth and the biofilms formed by bacterial cultures at different concentration of β –Lap were estimated by crystal violet absorbance at 570 nm and optical density at 600 nm respectively. The calculation for % inhibition of biofilm formation is discussed in material and methods section

Figure 8.

Mature biofilm disruption activity of β –Lap: A & B) the 24 hr mature biofilms were treated with β –Lap at 1xMBIC and 2xMBIC, developed with crystal violet and quantified by absorbance at 570 nm. C & D) the 48 hr ultra-mature biofilms were developed and quantified under similar conditions.

Figure 8.

Mature biofilm disruption activity of β –Lap: A & B) the 24 hr mature biofilms were treated with β –Lap at 1xMBIC and 2xMBIC, developed with crystal violet and quantified by absorbance at 570 nm. C & D) the 48 hr ultra-mature biofilms were developed and quantified under similar conditions.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).