1. Introduction

1.1. Silk and its Origin

Silk is one of the abundantly available natural fibrous proteins besides cellulose, chitosan and collagen that are spun by the larvae of Lepidoptera, such as silk worms, spiders, mites, scorpions, flies, and mites [

1]. It is a common raw material that is considered to be luxurious by the industry of textiles for more than a thousand years since it was first discovered by the Chinese and Indus cultures in the early 2500 BC [

2,

3]. The Chinese legends state that the Empress His Ling Shi was the first to have made the discovery of silk. The legend says that she was sipping tea under a Mulberry tree when a cocoon fell into her cup of tea and untangled. The empress was in awe of the shining threads and became the pioneer for sericulture, harvesting and cultivating silk worms and creation of the reel and loom [

4].

At the early stages silk was only to be used by the posh classes of the society and remained monopolised only in China till the Silk Road was inaugurated and the use of silk gradually spread. Even after this development China owned the silk trade for another millennium. Eventually the luxury of silk spread to Japan (300 AD) and Arabia, followed by its introduction to the European countries of Italy and France by the Crusades in the 16th century. Soon after when the industrial revolution began cotton became more preferable over silk for its cheap prices. At the same time several diseases started occurring in silk worms that brought the markets for silk down. Finally, by the 20th century Japan and China took over as the leading countries in the silk trade.

Silk occupies about 0.2% of the global industry of textiles and is produced by over 60 countries worldwide. The continent of Asia is the major producer of Silk - about 90% of the silk extracted from the mulberry species and 100% of silk extracted from non-mulberry species, after this industries of sericulture have recently taken root in Brazil, Bulgaria, Egypt and Madagascar. China is the largest silk producer in the world, followed by India close behind. The textile industry of silk also provides a lot of employment opportunities and has employed more than 1 million labourers in China, 7.9 million people in India and 20,000 families in Thailand. Besides this, silk is consumed largely by the countries of USA, Italy, Japan, India, France, China, UK, Switzerland, UAE, Korea, and Viet Nam [

5].

Besides having a lustrous outlook it had properties of tactile, being durable, first class mechanical strength, elasticity, Breathability and provided great level of comfort in both warm and cold weather, earning the name queen of textiles. Silk is also biocompatible to different biological systems and has been successfully used for suturing during surgeries since 150 AD. Still, we are several steps away from discovering the actual potential of silk in different dynamic and versatile developing fields, such as optics, electronics and biomedicine [

6].

1.2. Organisms that Produce Silk

Different arthropod species that produce different variants of silk have existed for a long time since the origin of life. The lists of the organisms producing silk are shown in the table below (

Table 1). Goats have also been found to produce milk with silk proteins that can be extracted [

7].

Among these the most commonly studied are the spider silk, dragline silk and mulberry silk that are synthesized by the major ampullate glands in spiders and cocoon silk from

Bombyx mori. The complete properties and characteristics of silk fibres is based on the morphology of the structure and the chemical composition. The structural morphology of silk originating from these species is very similar on the macroscopic level, they both have a core-shell framework [

8]. The properties of an even texture, shine and robustness has made silk from silkworms a suitable material for various fashion apparel, and those from spiders have been used for suturing and fishing.

2. Components of Silk

For producing silk in large quantities commercially the larvae of the

Bombycidae (mulberry silk) and

Saturniidae (non-mulberry silk) have been frequently known to be used. Based on the lifecycle, and feeding habits the silk can broadly be classified as mulberry silk and non-mulberry silk [

9]. The protein fibre silk is a combination of two parts–silk sericin (SS) and silk fibroin (SF) [

10]. SF makes up the core which brings the characteristics of robustness and the capability to bear weights, and SS is the adhesive. SS is a class of glycoproteins that is soluble in water and forms about 25-30% (w/w) of the entire cocoon. The habitat for feeding, type of nutrition and the biotic and abiotic factors determines the variation in the amino acids of SF and the variability of the presence of flavonoids or carotenoids in SS.

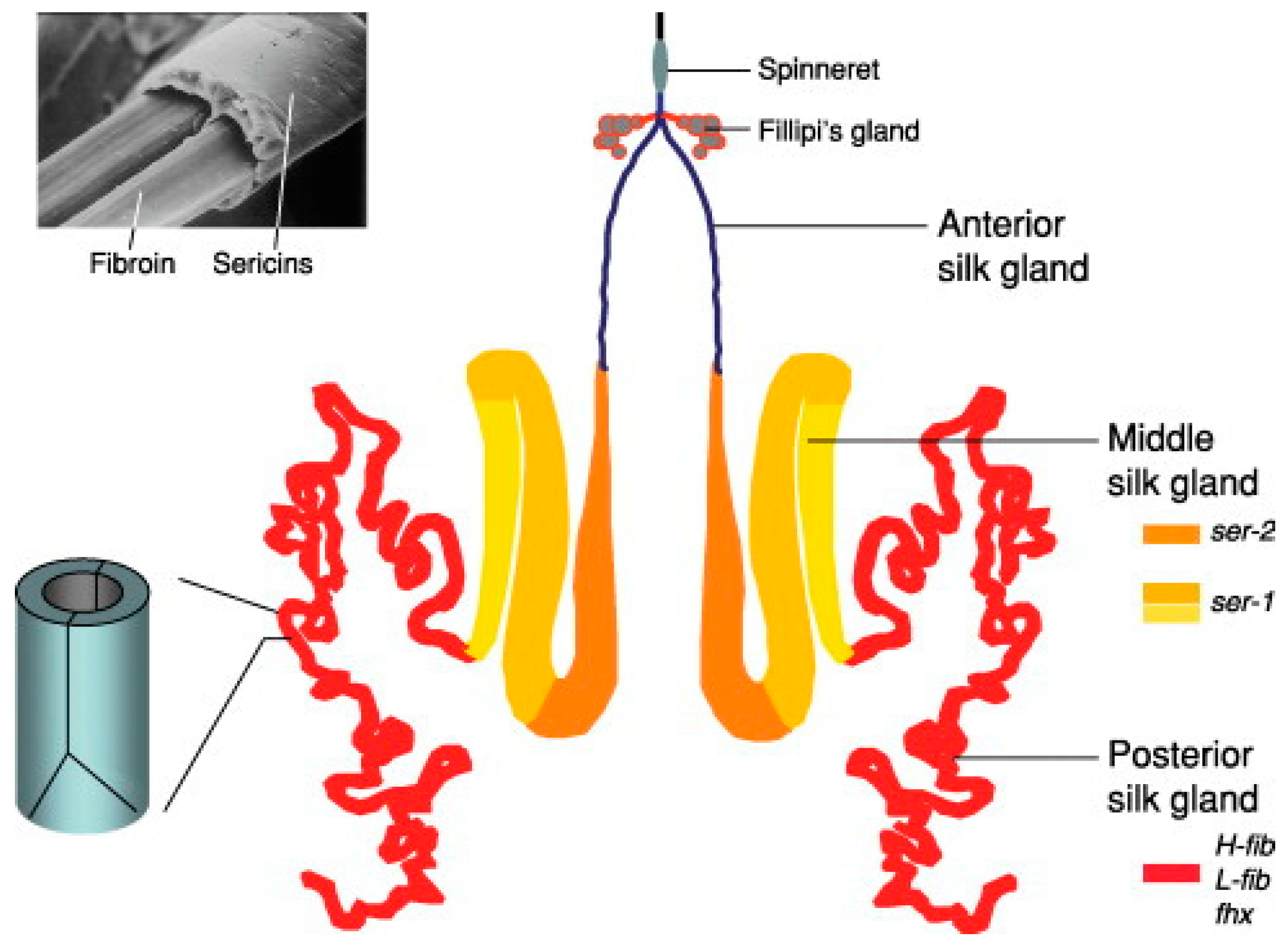

In order to comprehend the robustness and strength depicted by these fibres, it is required to inspect the methods by which the two proteins are processed within the silk glands. The cells of the lumen in the posterior silk glands secrete SF [

10,

11]. The secreted form of SF is in the α-helix-dominated conformation that is coined as the silk-I form [

12]. In the middle silk glands heterogeneous SS molecules are attached to the SF being transported via the same. Finally the mixture travels through the anterior silk gland, and drawn via the spinnerets.

Figure 1.

showing the structure of the silk glands.

Figure 1.

showing the structure of the silk glands.

On exposure to different forces and pH at the spinneret, the SF takes up an antiparallel-β-sheet crystal structure, which is known as the silk–II form, a filamentous form that is not soluble in water. Silkworms have in the process of evolution developed a unique method of folding and crystallization of SF for efficient production of fibre, which was found to be conserved between both the families [

13,

14,

15]. The distinction in the different silks produced is caused by; (a) the variation in the presence and assembly of the heavy chain (H-chain), light chain (L-chain) and the glycoproteins; (b) repetitive sequences of polypeptides that result in the distinct properties of silk; and (c) the various sericin segments present in different silk fibres.

2.1. Silk Sericin (SS)

SS is a glycoprotein produced in the middle silk glands that are mainly made up of serine, aspartic acid, and minute amounts of other amino acids such as histidine, threonine, tyrosine, and glutamic acid. Based on the level of solubility sericin is segregated into three segments, namely sericin A, sericin B, and sericin C. The outermost layer of the cocoon has sericin A, which is not soluble in water at high temperatures. Nitrogen and the amino acids serine, glycine, threonine, and aspartic acid make up 17.2% of the same. The middle layer of the cocoon contains sericin B, which has the same composition of amino acids as in sericin A, as well as tryptophan. Nitrogen makes up 16.8%. The innermost layer is sericin C, it is situated next to the layer of fibroin and cannot be dissolved in hot water. It is made up of sulphur, 16.6% nitrogen, and the amino acids, serine, glycine, threonine, aspartic acid, tryptophan and proline [

16]. Furthermore, sericin has been classified into different species on the basis of their relative solubility [

11,

17].

The conformation of sericin that is soluble in water is majorly a random coil, in contrast to this the β-sheet conformation is not easily soluble. A study of the sericin structure using the γ-ray by Wang et al., [

18] revealed that the outermost shell consisted of fibre direction filaments, the middle layer showed cross-fibre direction filaments, and the innermost layer exhibits filaments that are longitudinal. The temperature of casting is another important factor that determines how sericin will conform. At a low casting temperature, sericin conforms into β-sheets. At high temperatures the random coil structure of SS can easily dissolve in hot water, with the lowering of temperature, the structure converts to a β-sheet which leads to the formation of a gel. This property also makes it a sol-gel. The presence of a larger number of acidic amino acids brings the isoelectric point down to about 4.0. It is found to have a molecular weight in the range of 17100–18460 Da [

17,

19].

Even though SS is observed mainly as a by-product and waste in the silk-textile industry, it has gained a lot of fame in the cosmetic and pharmaceutical industry due to its antibacterial, antioxidant, anti-coagulant, and wound healing characteristics [

20].

2.2. Silk Fibroin (SF)

The SF filaments spun are in a group of two that is enveloped by SS that depicts a smooth triangular cross-section when viewed under the microscope. A light (L) chain polypeptide and a heavy (H) chain polypeptide when connected together by a single disulphide bond, at the C-terminus of the H-chain making an H-L complex, constituents silk fibroin [

21,

22,

23]. This complex also binds to the glycoprotein P25 in a 6:6:1 molar ratio respectively through hydrophobic bonds, finally giving rise to a primary micellar unit. Such units are responsible for the movement of large amounts of fibroin via the lumen of the silk glands to the spinnerets before they are spun into fibres. The H-chains arrange themselves into β-sheets which makes up the crystalline region of the fibre. It comprises mainly of glycine, alanine, serine, tyrosine, valine, aspartic acid, phenylalanine, glutamic acid, threonine, isoleucine, leucine, proline, arginine, lysine, and histidine [

24]. The chains mostly consist of glycine and alanine along with other amino acids. Fibroin that is produced naturally has a very high tensile strength of about 300-700 MPa, besides this it has a very high strain of breaking and robustness [

24,

25].

The N-terminal is glycosylated having residues of mannose and glucosamine [

26]. The regions of the β-sheet crystallite in silk consist the poly-repeats of glycine and alanine (GAGAGS, GAGAGY) as repeat sequences. It has been observed that these regions are embedded between the regions of α-helical structure. The strength that silk exhibits is due to the strong inter-chain interactions by hydrogen bond formation between the crystallite regions.

In the non-mulberry type of silk fibre the L-chain of SF and P25 is absent. It is hypothesised that the genes that code for P25 represent a paralog of gene/genes that may have developed new functions besides the formation of fibres observed in the mulberry silk class. The H-chain undergoes dimerization with itself forming homodimers, making up the core of the fibre. Another contrast, is the presence of poly alanine repeat regions instead of the poly-alanine and glycine repeats. The twin filaments of fibroin get disoriented while the fibre is formed, since the H-chains are unable to get packed giving rise to a large number of bulky SF chains [

27].

** Spider Silk–Spiders depend on the silk they produce for their entire lifecycle. Depending on the type of web weaved, spiders are segregated into orb web spinners or non-orb web spinners. The former trap their prey on the exterior part of the web, while the latter trap their prey in a complicated maze of their web. The orb weaving spiders make use of six varieties of silks and glue that is like silk generated in seven separate organs to spin a single orb [

28]. All of these structural proteins of silk are made up of repeating monomers called spidroins. Spidroin is made up of core that is unique and different for each silk, adjacent to this lies amino residues that are not repeated and the carboxy terminals. The variation in the strength of the fibre is due to the repeating units in the core of the spidroin.

A substance very similar to sericin is secreted to cause the silk fibres to adhere to each other by the aggregate gland [

29]. This coating is mainly made up of lipids, glycoproteins that are phosphorylated, and low molecular weight compounds that are organic such as γ-aminobutyramide, choline, betaine, and isethionic acid. Dragline silk produced by orb weavers is made up of major ampullate spidroins (MAS). The MAS complex constitutes two protein parts: (a) Major ampullate dragline silk protein 1 (MaSp1) and (b) Major ampullate dragline silk protein 2 (MaSp2) [

30]. Both these proteins are made up of domains rich in poly-alanine and poly-glycine. The major difference in these two is that the latter has 15% of proline, while the former is free of proline [

10].

3. Properties of Silk that Make it Suitable for Biomaterial Research

Silk is found to have different physical features that consist of the length of the silk filament, fineness of the fibre, and density. Silk filaments are obtained from cocoons using the process of reeling. While reeling is carried out, about 8–10 strands of silk filaments can be extracted from each cocoon that can be used several silk yarns. For successful reeling, the amount of filaments that can yielded from a cocoon should be known. A nonbreaking filament length (NBFL) is a silk filament that is present in a cocoon without any breaks. The property of fineness of silk is expressed in the unit of denier (this denotes the mass of 9 km of fibre length in terms of grams). Among all these, mulberry silk is the finest, following this are eri, oak tasar, muga and tasar varities of silk. Tasar is the roughest of the silks. It has been observed that the fineness of the fibre decreases gradually towards the inside of the cocoon. Muga silk fibre has the lowest density, while mulberry has the highest density [

31].

Silk is made up of a variety of amino acids, and its property as a protein is based on the characteristics of its integral amino acids along with the characteristics that arise from the size of the protein. Silk resists acidic substances to an extent, but heated acids are able to break the peptide bonds causing damage to the fibre. In contrast when treated with weak acids the “scroop effect” develops which is a well-renowned finishing treatment of silk creating a crackling sound when the fibres are rubbed against each other. They show a low resistance to alkaline substances and are prone to damage upon exposure to even weak alkalis that are heated. The presence of both acidic and alkaline amino acids, the fibre becomes amphoteric in nature, this also makes it possible for the fibre to be dyed by any class of dyes [

31].

The basic to acidic amino acid ratio in both mulberry and non-mulberry classes of silk is responsible for the variation in the hydrophilicity and hydrophobicity of the fibroin surface, and corresponds to the property of surface variability in biomaterials that are obtained from the solution of regenerated silk [

32]. The crystalline property of SF plays a role in the biodegradation of the regenerated SF based biomaterials, upon manipulating this factor using physico-chemical treatments the rate of biodegradation and stability in water of biomaterials can be controlled [

33,

34]. The good physical and chemical properties along with a high resistance to denaturation under heat adds an advantage to silk based biomaterials, which is that they can withstand a majority of the sterilization methods [

10].

One major advantage of using silk proteins is that a large quantity of silk is produced, almost more than 70% of the silk is produced by the continent of Asia. As compared to collagen which is extracted from animals, the green method of extracting silk proteins from silk cocoons and silk glands is much easier. Hence, the FDA has approved the use of silk proteins for drug delivery, surgical sutures, and applications of tissue engineering [

35]. Furthermore silk can be processed easily using aqueous solutions unlike the use of acidic solutions for processing collagen and chitosan. The presence of poly-alanine and poly-glycine repeats in mulberry silk, and poly-alanine repeats in non-mulberry silk make them suitable for use in tissue engineering [

36]. The simple processes of extraction and processing make it easy for the process to be scaled up in biomedical research. The regenerated aqueous SF solution is used to make several 2D films, 3D silk sponges, membranes that are electrospun, nanoparticles, microparticles, hydrogels, surfaces that are micropatterned, 3D printed constructs, micro-moulded, and microfluidic devices [

10]. The sequence of silk fibres that are stored in databases can be used to design biomaterials in silico, this ensures the material design predicted will suit the needs in the most appropriate manner. Such an example is seen in hydrogels formed by silk proteins, where atomistic modelling is used to regulate the different degrees of hydrogen bond formation [

37]. The scaffolds of silk proteins have high antigenicity and compatibility to cells that makes them suitable for use under

in vitro conditions. Finally being a protein, it can easily be degraded by proteolytic enzymes making silk protein based biomaterials biodegradable. This is vital for tissue engineering as a biomaterial used needs to be resorbed so that a secondary surgical procedure can be avoided.

4. Application of Silk Proteins as Biomaterials

4.1. Silk Hydrogels

Biomaterials have been playing a major role in the field of regenerative medicine its usage in implants, sutures, contact lenses, hip joints, vascular grafts, wounds dressing materials, drug-releasing stents, and many more biomedical devices. Recent advancements to develop suitable material properties have provided a great opportunity in the field of tissue engineering and therapeutic medicine [

38]. The development of three-dimensional structure providing support called Hydrogels have gained much attention in the biomedical field, these hydrogels are water-swollen three-dimensional viscoelastic macromolecular networks, cross-linked through covalent bonds or non-covalent interactions such as electrostatic interactions, hydrogen bonding, hydrophobic association and multivalent coordination [

39], hydrogels have attracted great importance due to their ability to absorb a large amount of water along with the maintenance of structural integrity, and high porosity allowing the rapid diffusion of small molecules resembling extracellular matrix of the cell [

40]. Various natural as well as synthetic polymeric materials have been used to prepare hydrogels. Synthetic polymers include polylactic acid (PLA), polyurethane (PU), poly (lactide-co-glycolide) (PLGA), and polycaprolactones (PCL), although these synthetic polymers had better mechanical properties and decomposition rates than most this polymer’s by-products are dangerous acidic chemicals causing undesired immunologic reactions. These limitations of synthetic polymers turned scientists towards naturally producing polymers [

41]

. Silk proteins have attracted much scientific attention because of their potential to be designed as a novel biomaterial for biomedical applications like drug delivery, tissue engineering, biosensors, etc [

42]. The unique feature of silk is its tenability in different morphological forms, economic manufacturing processes, advanced mechanical properties, biodegradability, biocompatibility, and bio-resorbability [

41]. Various kinds of silk-based hydrogels and nanogels having high efficiency have been designed to overcome the limitation of conventional polymers [

42]. These hydrogels have applications in drug delivery due to their control over the concentration, molecular weight, and crystallinity of the silk protein which allows tuneable mechanical properties and release kinetic with delivery systems. Their simple fabrication methods under mild conditions provide versatility to the retention of bioactive characters of therapeutics being delivered [

43].

Model drugs incorporated in the silk nanoparticles and silk hydrogels showed fast and constant release indicating successful dual drugs release [

44]. They have many other applications in the injectable scaffold, gene therapy, tissue regeneration, and 3D bioprinting of cardiac tissue that could recapitulate the native cardiac microenvironment, useful in the treatment of intervertebral disc of the spinal cord [

45,

46], silk fibroin hydrogels of Bombyx mori have been widely used to regenerate cartilage as it is found to be a promising alternative to the cartilage tissue [

47]

. In spite of the promising application mentioned, there are still some important issues to be addressed in the future focusing on the ability of a polymer to predict the possible toxicological reactions to the material and on characterizing the structure and chemical properties of the polymer in the host to reduce the immune response and chance of rejection in the patients.

4.2. Tissue Engineering

Tissue engineering is a biomedical field that makes use of the principles of engineering and life sciences to produce 3D natural tissue with the help of cells, scaffolds and biomolecules to restore, repair or maintain the functions of a tissue or an entire organ [

10,

48]. The kind of biomaterial used and its design mechanism determines whether the resulting scaffold will function successfully or not. Silk has a low rate of degradation and causes minimal inflammation, making it a good fit for scaffolds that need to be biodegradable and which require a slower growth.

A tissue scaffold generated by tissue engineering should be able to recruit cells, adhere cells, proliferate, and differentiate

in vivo. These can generated using a number of traditional techniques namely, freeze-dry method, fibre bond process, self-assembling, casting of solvent, foaming of gas method, electrospinning, and leaching of porogen. Even though they produce good scaffolds these methods have some limitations such as the pore size and distribution cannot be controlled, the seeding and the cell proliferation is not uniform. To deal with this mechanism of rapid prototyping (RP) can be used. This method uses computer aided design (CAD) softwares and high end imaging procedures to construct a 3D model of the desired tissue, which is then mimicked by selective lase sintering (SLS) [

49], fused deposition modelling [

50], pressure-assisted micro-syringe [

51] and 3D bioprinting. Different kinds of tissue scaffolds generated have been listed below in

Table 2.

4.3. Drug Delivery

The field of drug delivery is gaining a lot of popularity, specifically at a nanoscale so that the delivery of different therapeutic drugs can be released efficiently and regulated. For an ideal drug carrier system, the materials used should be such that: (i) they are not toxic under in vivo conditions; (ii) have the desired properties required to survive within the body; (iii) biodegradation.

SF has been used a lot in the biomedicine field as it is compatible in biological systems, has exceptional mechanical properties, and a property of biodegradation that can be manipulated. The rate of SF degradation can be easily controlled by altering the molecular weight, the level of crystallite formation, or the formation of cross-linking [

73,

74]. Some of the methods commonly used for developing such drug delivery systems are aqueous based procedure of preparation, salting-out method, using a co-flow capillary device, and coaxial electrospraying. A blend of PVA was used in the aqueous-based method of system fabrication to develop nanospheres of silk, whose size and shape could be regulated. The spheres exhibited that the distribution of the drug and efficiency of loading the drug was correlated to the hydrophobicity and the charge on the system, giving rise to a spectrum of profiles for the release of the drug [

75]. Magnetic SF nanoparticles were fabricated by the salting-out method, for which the loading of the drug could be controlled by manipulating the concentration of the magnetic nanoparticles of ferric oxide [

76]. SF spheres developed by the co-flow capillary device method makes use of PVA as the mobile phase and the silk as the unattached phase. Upon regulating the polymer concentration, ratio of the different rates of flow, and the molecular weight of the polymer, the diameter of the sphere generated could be changed accordingly. The drug release by the spheres could be further controlled by manipulating the diameter of the spheres [

77]. Silk nanoparticles produced by coaxial electrospraying can have different properties depending on the requirement, and can be a blend of both natural and synthetic materials. In nanoparticles of SF and with PVA as the core, the profiles of drug release could be changed by adjusting the ratio of PVA in the core. Furthermore, the targeted release can be achieved by modulating the pH [

78].

4.3.1. Drug-delivery System for Cancer

The major problems faced by cancer therapeutic drugs are that the release of the drug does not occur for a longer duration of time, as a result requiring more doses. Silk as a biomaterial can aid in overcoming this due to its properties of compatibility, degradability and no rejection possibility by the immune system in a biological system. Formulations like silk hydrogels, silk-coated liposomes, capsules, and nanoparticles can be used as systems for drug delivery. Also, the rate of drug delivery can be modulated by making changes in the silk film crystallinity [

78]. A lot of research has been done on mice models, by entrapping the drugs doxorubicin and paclitaxel, which showed that the rate of the drug release as well as efficiency of accurate target delivery had improved significantly [

79,

80].

Another application of SF in oncology, is that it can be used to depict the cancer

in vivo by replication in three dimension. This helps to understand what treatments would be better and how it can be dealt with [

81]. This has been done to study models of breast cancer, mammary adenocarcinoma, and liver cancer.

4.4. Tissue-on-chip for High Throughput-screening

There is a growing requirement for novel technologies that will reduce the number of lack of successes in the pre-clinical trials of drug-carrier systems. A high-end technique called tissue-on chip or organ-on-chip (TOC/OOC) was developed to combat this major issue [

82]. This technique attempts to replicate the actual active systems for the drug development and screening, so that there is minimal chance of failure. Several such TOCs for the heart, skin, lungs, kidneys, and arteries have already been constructed. In the recent years, hydrogels of silk have gained popularity for this purpose, as scaffolds of silk can easily mimic the functional tissues present

in vivo. SF has used to make a microfluid device that can mimic a functional liver, it was observed that the hepatocytes generated by this device exhibited functions and structure similar to the natural tissue. This high-end technology is a boon for the biomedical field as it will help in the better comprehension of the behaviour, functioning, and the physiology of cells.

4.5. Silk-based Biosensing and Biomedical Imaging

Different kinds of bio-inks can be developed using SF, which can further be loaded with compounds to generate functional devices which are printable by inkjet for sensing, regenerative medicine, and therapeutics [

10]. Inks that are silk-based can be loaded with compounds like antibiotics which are active therapeutically and then this can be placed in antimicrobial assays [

83]. SF has been used to detect pesticides by producing traditional biosensors that use amperometry [

84]. SF has also been incorporated into several consumable food biosensors to detect when the get spoiled [

85].

Bioimaging procedures using silk has progressed a lot by conducting studies on the construction of fluorescent SF nanospheres [

86], luminescent carbon dots made of silk [

87] and graphene oxide magnetic fluorophore [

88].

4.6. Food Technology

Globally more than a third of the food that is produced gets wasted or damaged, rather than consumed as per several reports. This does not only cause damage to the quality and safety of food but also significantly affects the economy and resources. Silk proteins have been proved to aid in dealing with this problem to a large extent. SF has been used as a consumable sensor in cheese and fruits to detect ageing and ripening respectively [

10]. The shelf life of food was increased by dipping food in a SF protein suspension that was based on water. The suspension was found to stick as an eatable coating on the food and worked by reducing the respiration rate and loss of moisture in the cell [

89]. A live hybrid composite of a single celled fungi and silk nanofibrils that are regenerated from fermenting yeast was constructed. The hybrid microbes with increased cellular activity decreases the permeability of water and improves the shelf life of the food as well. A method in which the packaging of food can be improved is by transferring this composite to the parafilm substrate, as a result the conditions of food storage are improved remarkably [

90]. SS from

Bombyx mori has been found to ease constipation, reduces the development of gastrointestinal tract cancers, and increases the absorption of different minerals [

91]. Proteins of silk have also been used in producing food for babies and has been attested that it can prevent and reduce atopic asthma and atopy [

92]. It has been also claimed that when added into healthcare food can be used to prevent and manage Parkinson’s disease [

93].

4.7. Electronics

Presently biomedical devices with electronic parts for therapy purposes or performing functions like regulation of cardiac signals, drug delivery, and improving the biological structures are being developed. These devices have been produced so that they can function from within the live tissue [

94]. Such devices that are implantable have a degradation rate that is degradable, and function in an efficient manner without causing any inflammatory response or any kind of rejection. Silk has special properties of having tough mechanical strength, degradation that can be regulated, and can be constructed into several forms. The Food and Drug Administration (FDA) has given the approval for the use of silk in the electronic devices that play a major role in healthcare and biomedical sectors [

95]. A degradable implant based on silk was developed, and was found to successfully fight infections of

Staphylococcus aureus. After the infection was over in the body the implant would get resorbed automatically. It was made up of a serpentine resistor and a coil that acquired the power through a substrate of silk. The device was created to treat

S. aureus infected areas with heat [

96].

4.8. Biomedical Textiles

For a long time materials for biomedical sector have been produced to be used for first aid, clinical aids, and hygiene requirements. Textile materials that cannot be implanted include wound dressings, while those that can be implanted consist of vascular grafts, heart valves, polymer-based sensors, and sutures [

97,

98]. These materials can be segregated into materials that cannot be implanted, implants, extracorporeal implants, and materials of healthcare.

Wound dressings, garments for applying pressure, orthopaedic bandages, prosthetic socks, and several other varieties. Silk has been used a lot for dressings of the wound, constructing fibre mats by electrospinning and techniques of non-weaving [

99]. It was found combinations of silver (Ag) nanomaterials and SF, and titanium dioxide and SF was used to make dressings with good antibacterial properties [

100]. In the present days. A wound dressing of two layers was constructed with SF that was wax coated, SS sponge, and a glutaraldehyde layer of cross-linked SF gelatin was showed a decrease in the size of the wound, epithelia and collagen formation [

101]. Besides these silk has been used for the production of masks, gowns, caps, drapes and cover cloths for patient especially for surgical operations in the healthcare sector.

Wound closures during skin surgeries, vascular implants, for artificial ligaments and tendons, and prosthetic heart valves are some commonly used textiles that can be implanted. Sil sutures have been used for a long time. The elasticity and robustness of SF was increased by 50% PVA by weight, making them appropriate for sutures [

102].

Extracorporeal organs are organs that are artificially created to purify blood. The organs that are usually used are artificial kidneys, artificial livers, and lungs. An artificial kidney system was created by making use of a urease enzyme immobilized SF-based membrane and a spherical polymer carbon-based adsorbent for peritoneal dialysis. It was able to efficiently elude toxins from the system [

103]. Mulberry and no-mulberry SF were used to make a functioning artificial liver that was able to efficiently function as well as stimulate the growth of the hepatocytes [

104].

4.9. Cosmetics

Several studies indicate that silk has been used as a major ingredient of cosmetic products for a long time. Combinations of SS and SF are used in products for the hair, skin, and nails. SS based lotions, creams, and ointments show effects of elasticity, anti-wrinkling and anti-aging on skin. The amino acid residues present in SS is responsible for its properties of retaining and absorbing moisture, making it suitable for skin products that maintain the skin’s moisture, elasticity thereby keeping it soft and smooth. SS was also reported to stop the activity of tyrosinase and formation of melanochrome, making it ideal for products to whiten the skin. A scanning electron microscopy (SEM) study also revealed that SS improves the quality of hair and helps to repair it as well [

105].

A study conducted on sericin gel revealed that the concentration of hydroxyproline had significantly increased in the stratum corneum, and the impedance of skin reduced drastically. Images of SEM demonstrated that the cracking and flaking of skin decreased as well [

106]. Experiments on cosmetic products created using cellulose fibres saturated with dispersed SF and aqueous SS showed a good adsorption efficiency of sweat and sebum [

10]. Several lotions, foundation creams, eyeliners have been created by depositing a coat of sericin hydrolysate on talc, nylon, mica, titanic, and iron oxide. Sericin based sunscreens have shown an improved screening effect of UV light specifically [

107]. Several cosmetic products for nails having about 0.02–20% sericin have inhibited nail brittleness, chapped nails, and retained gloss for longer durations [

108]. Hair care products such as shampoos and conditioners, having sericin as an ingredient can be used for the purpose of maintenance and repair [

109].

4.10. Bioremediation

Anthropogenic activities have led to severe pollution of the environment, thereby reducing the quality of land, air and ground-water, making this a major global concern at present. Hence, remediation of the environment to revive it is very vital. Several polymers combined with silk have been used to remove hard metals from the aqueous solutions, to purify water [

110,

111], as toxic dye adsorbents, and as air filters [

112,

113].

5. Challenges and Benefits

The increasing population has brought about a growing demand for healthcare and biomedical requirements. Biomaterials that are a blend of silk and other polymers produced have different clinical and healthcare applications. Silk has made drawn its path into the healthcare industry due to its properties of biocompatibility, degradability, simple processing, and high tensile strength. The possibility to alter the fibre and its reduced immunogenicity are factors that make it suitable for tissue engineering, drug delivery, cancer therapy, and biomedical imaging. Silk is able to replicate the functioning of the natural extracellular matrix of different tissues since it can be easily altered when engineered making it ideal as a biomaterial. It has a huge potential as a biomaterial in the domains of healthcare and biomedical imaging, but whether it will be able to match the surplus demand of the future is a matter of concern. The fields of electronics and sensors are undergoing development at exponential rates in order to produce counterparts for silk that bring out maximum efficiency of the products or devices. The production of silk-protein based products with negligible or no side effect will prove advantageous for the food and cosmetics industry. Finally, silk is able to provide solutions for remediation of the environment that are feasible and affordable in areas with severe pollution.

6. Conclusion

Silk as a polymeric fibre has several beneficial properties such as biocompatibility, low immune response generation, mechanical strength that can be regulated, biodegradability, along with the production of bio-products that are not toxic. In several Asian countries it is a major source of income and due to it being abundantly available and affordable it is a prominent material for research. By exploiting the non-mulberry silks available endemically new employment avenues will open up, thereby helping the local people involved in the silk textile industry and maintain the biodiversity. Silk having a broad spectrum of suitable characteristics has several applications in the production of healthcare products and methodologies. Since the olden times silk has been used as a fibre for dressing wounds, for suturing, and as textiles. Its immense potential in various other sectors such as cosmetics, oncology, tissue engineering, TOC screenings, for preserving food and bioremediation makes it a beguiling biopolymer for researchers. There are still a few impediments in regulating the products and technologies for producing silk-based products, but the large number of advantageous properties silk has exceeds the problems of the production of silk-based products.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, S.J.P, P.T. and V.N.; resources, R.D.; data curation, R.D., S.J.P.; writing, reviewing and data preparation, R.D., S.J.P.; writing, review and editing, R.D, S.J.P., P.T., V.N., A.O.; figure and tables, R.D., R.J.S., S.J.P.; supervision, V.T., S.J.P.; review and plagiarism, V.N., S.J.P.; funding acquisition, P.T., V.T., A.O., R.J.S., S.J.P.; All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Not applicable

LIST OF ABBREVIATIONS

BC–Before Christ

AD–Anno Domini

SS–Silk Sericin

SF–Silk Fibroin

w/w–weight by weight

H-chain–heavy chain

L-chain–light chain

Da–Dalton

MAS - Major ampullate spidroins

MaSp1–Major ampullate dragline silk protein 1

MaSP2 - Major ampullate dragline silk protein 2

NBFL–Non-breaking filament length

FDA–Food and Drug Administration

3D - Three dimension

RP–Rapid Prototyping

CAD–Computer aided design

SLS–Selective laser sintering

BMSCs–Bone marrow mesenchymal stromal cells

HA–Hydroxyapatite

PVA–Polyvinyl alcohol

hPL–Human Platelet Lysate

TGF-β3–Transforming Growth Factor

PCL–Polycarprolactone

MI–Myocardial Infarction

PLA–Polylactic acid

ACL–Anterior Cruciate Ligament

IVD–Intervertebral Disc

NP–Nucleus pulposus

AF–Annulus fibrous

TOC–Tissue on chip

OOC–Organ on chip

Ag–Silver

SEM–Scanning Electron Microscopy

UV–Ultraviolet

References

- Prasong, S.; Yaowalak, S.; Wilaiwan, S. Characteristics of Silk Fiber with and without Sericin Component: A Comparison between Bombyx mori and Philosamia ricini Silks. Pak. J. Biol. Sci. 2009, 12, 872–876. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vainker, S.J. Chinese Silk: A Cultural History; Rutgers University, Press: Pistacaway, NJ, USA, 2004; pp. 50–51. [Google Scholar]

- Good, I.L.; Kenoyer, J.M.; Meadow, R.H. New Evidence for early silk in the indus civilization. Archaeometry 2009, 51, 457–466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fromental “The history of silk” accessed on 1st June 2021 from the History of Silk-Fromental.

- International Sericulture Commission (2013). Statistics-Global Silk Industry. accessed from the website on 1st June 2021 at Schautatistics | International Sericultural Commission (inserco.org).

- Zubir, N.; Pushpanathn, K. Silk in Biomedical Engineering: A Review. Int. J. Eng. Invent. 2016, 5, 18–29. [Google Scholar]

- Elices, M.; Guinea, G.V.; Plaza, G.R.; Karatzas, C.; Riekel, C.; Agulló-Rueda, F.; Daza, R.; Pérez-Rigueiro, J. Bioinspired fibers follow the track of natural silk spider. Macromolecules 2011, 44, 1166–1176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hardy, J.G.; Römer, L.M.; Scheibel, T.R. Polymeric materials based on silk proteins. Polymer 2008, 49, 4309–4327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kundu, S.C.; Kundu, B.; Talukdar, S.; Bano, S.; Nayak, S.; Kundu, J.; Mandal, B.B.; Bhardwaj, N.; Botlagunta, M.; et al. Nonmulberry silk polymers. Biopolymers 2012, 97, 455–467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bandyopadhyay, A.; Chowdhury, S.K.; Dey, S.; Moses, J.C.; Mandal, B.B. Silk: A Promising Biomaterial Opening New Vistas Towards Affordable Healthcare Solutions. J. Indian Inst. Sci. 2019, 99, 445–487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mondal, M.; Trivedy, K.; Kumar, S.N. The silk proteins, sericin and fibroin in silkworm, Bombyx mori Linn.—A review. Casp. J. Environ. Sci. 2007, 5, 63–76. [Google Scholar]

- Hu, X.; Shmelev, K.; Sun, L.; Gil, E.-S.; Park, S.-H.; Cebe, P.; Kaplan, D.L. Regulation of Silk Material Structure by Temperature-Controlled Water Vapor Annealing. Biomacromolecules 2011, 12, 1686–1696. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Julien, E.; Coulon-Bublex, M.; Garel, A.; Royer, C.; Chavancy, G.; Prudhomme, J.C.; Couble, P. (2005). 2.11 Silk Gland Development and Regulation of Silk Protein Genes. In: Gilbert L. (2nd ed) Comprehensive Molecular Insect Science. Elsevier, pp. 369–384.

- Jin, H.-J.; Kaplan, D.L. Mechanism of silk processing in insects and spiders. Nature 2003, 424, 1057–1061. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asakura, T.; Yao, J.; Yang, M.; Zhu, Z.; Hirose, H. Structure of the spinning apparatus of a wild silkworm Samia cynthia ricini and molecular dynamics calculation on the structural change of the silk fibroin. Polymer 2007, 48, 2064–2070. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shaw, J.T.B.; Smith, S.G. Amino-acids of Silk Sericin. Nature 1951, 168, 745. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Padamwar, M.N.; Pawar, A.P. Silk sericin and its applications: A review. J. Sci. Ind. Res. 2004, 63, 323–329. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, T.; Wang, J.; Zhou, J. γ-Ray study on the sericin structure of cocoon silk. Fangzhi Xuebao 1985, 6, 133–134. [Google Scholar]

- Nandikolmath, V.; Kanth, R.L.; Padhy, S.K.; Padhy, M.R.; Patil, S.J. Preparation of Bio-Bandage from Human Platelet Lysate Admixed with Sericin Polymer for Efficient Wound Healing. Int. J. Med. Res. Health Sci. 2021, 10, 8–20. [Google Scholar]

- Kundu, S.C.; Dash, B.C.; Dash, R.; Kaplan, D.L. Natural protective glue protein, sericin bioengineered by silkworms: Potential for biomedical and biotechnological applications. Prog. Polym. Sci. 2008, 33, 998–1012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Javali, U.C.; Padaki, N.V.; Das, B.; Malali, K.B. (2015). Developments in the use of silk by-products and silk waste. In: Basu A (ed) Advances in silk science and technology. Woodhead Publishing, pp. 261–270.

- Narmadha, B.; Devi, R.S. Silk Proteins in Biomedical Applications–A Review. Int. J. Adv. Res. Innov. Ideas Educ. 2017, 3, 482–488. [Google Scholar]

- Koha, L.-D.; Cheng, Y.; Teng, C.-P.; Khina, Y.-W.; Loha, X.-J.; Teea, S.-Y.; Lowa, M.; Yea, E.; Yua, H.-D.; Zhang, Y.-W.; et al. Structures, mechanical properties and applications of silk fibroin materials. Prog. Polym. Sci. 2015, 46, 86–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vepari, C.; Kaplan, D.L. Silk as a biomaterial. Prog. Polym. Sci. 2007, 32, 991–1007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marsh, R.E.; Corey, R.B. Linus Pauling An investigation of the structure of silk fibroin. Biochem. Et Biophys. Acta 1955, 16, 1–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naskar, D.; Barua, R.R.; Ghosh, A.K.; Kundu, S.C. (2014). Introduction to silk biomaterials. In: Kundu SC (ed) Silk biomaterials for tissue engineering and regenerative medicine. Woodhead Publishing, pp 3–40.

- Asakura, T.; Yao, J.; Yamane, T.; Umemura, K.; Ulrich, A.S. Heterogeneous structure of silk fibers from Bombyx M Ori Resolved by 13C Solid-State NMR spectroscopy. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2002, 124, 8794–8795. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Heim, M.; Keerl, D.; Scheibel, T. Spider silk: From soluble protein to extraordinary fiber. Angew. Chem. 2009, 48, 3584–3596. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hu, X.; Yuan, J.; Wang, X.; Vasanthavadava, K.; Falick, A.M.; Jones, P.R.; La Mattina, C.; Vierra, C.A. Analysis of aqueous glue coating proteins on the silk fibers of the cob weaver, Latrodectus Hesperus. Biochemistry 2007, 46, 3294–3303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tokareva, O.; Jacobsen, M.; Buehler, M.; Wong, J.; Kaplan, D.L. Structure–function–property–design interplay in biopolymers: Spider silk. Acta Biomater. 2014, 10, 1612–1626. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- N. V. Padaki, B. Padaki, N. V., Das, B., & Basu, A. (2015). Advances in understanding the properties of silk. Advances in Silk Science and Technology, pp. 3–16. [CrossRef]

- Katanchalee, M.; Boonkitpattarakul, K.; Jaipaew, J.; Mai, B. Evaluation of the properties of silk fbroin flms from the non-mulberry silkworm Samia cynthia ricini for biomaterial design. J. Biomater. Sci. Polym. Ed. 2011, 22, 2001–2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mieszawska, A.J.; Llamasa, J.G.; Vaiana, C.A.; Kadakia, M.P.; Naik, R.R.; Kaplan, D.L. Clay enriched silk biomaterials for bone formation. Acta Biomater. 2011, 7, 3036–3041. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aznar-Cervantes, S.; Martínez, J.G.; Bernabeu-Esclapez, A.; Lozano-Péreza, A.A.; Meseguer-Olmo, L.; Oterob, T.F.; Cenis, J.L. Fabrication of electrospun silk fibroin scaffolds coated with graphene oxide and reduced graphene for applications in biomedicine. Bioelectrochemistry 2016, 108, 36–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bettinger, C.J.; Cyr, K.M.; Matsumoto, A.; Langer, R.; Borenstein, J.T.; Kaplan, D.L. Silk Fibroin Microfluidic devices. Adv. Mater. 2007, 19, 2847–2850. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mandal, B.B.; Kundu, S.C. Cell proliferation and migration in silk fbroin 3D scaffolds. Biomaterials 2009, 30, 2956–2965. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhu, Z.; Ling, S.; Yeo, J.; Zhao, S.; Tozzi, L.; Buehler, M.J.; Omenetto, F.; Li, C.; David, L. Kaplan High-Strength, Durable All-Silk Fibroin Hydrogels with Versatile Processability toward Multifunctional Applications. Adv. Funct. Mater. 2018, 28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sonia, K.; Kundu, M.S. Silk protein based hydrogels: Promising advanced materials for biomedical applications. Acta Biomater. 2016, 31, 17–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ozgun Can, O.; Syed, B.; Muhammad, N. Self assembled silk fibroin hydrogels: From preparation to biomedical applications. Mater. Adv. 2022, 3, 6920–6949. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohamed, C.; Fatima, S.; Marta, F.; et al. Accelerated simple preparation of Curcumin loaded silk fibroin/ Hyluronic acid hydrogels for Biomedical applications. Polymers 2023, 15, 504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kiran, R.E.K.; Priya, V.V.; Nikhita, R.; et al. Silk Hydrogel for Tissue engineering: A review. J. Contemp. Dent. Pract. 2022, 23, 467–477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, S.; Syed, S.; Basharat, K. Silk based nano hydrogels for futuristic biomedical application. J. Drug Deliv. Sci. Technol. 2022, 72, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burcin, Y.; Laura, C.; David, K. Extended release formulations using silk proteins for controlled delivery of therapeutics. Expert Opin. Drug Deliv. 2019, 16, 741–756. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keiji, N.; Shoya, Y.; Naofumi, N. Biocompatible and biodegradable dual drug release system based on silk hydrogel containing silk nanoparticles. Biomolecules 2012, 13, 1383–1389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laura, V.; Poonam, S.; Jelena, R.K.; et al. 3D bioprinting of cardiovascular tissues for in vivo and invitro applications using hybrid hydrogels containing silk fibroin: State of the art and challenges. Curr. Tissue Microenviron. Rep. 2020, 1, 261–276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frauchiger, D.; Tekari, A.; Woltje, M.; et al. A review of the application of reinforced hydrogels and silk as biomaterials for interverbal disc repair. Eur. Cells Mater. 2017, 34, 271–290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zohre, M.; Samira, A.; Mohammad, T.A.; et al. Composite silk fibroin hydrogel for cartilage tissue regeneration. J. Drug Deliv. Sci. Technol. 2022, 79, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Howard, D.; Buttery, L.D.; Shakesheff, K.M.; Roberts, S.J. Tissue engineering: Strategies, stem cells and scaffolds. J. Anat. 2008, 213, 66–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, K.H.; Chua, C.K.; Leong, K.F.; Cheah, C.M.; Cheang, P.; Bakar, M.S.A.; Cha, S.W. Scaffold development using selective laser sintering of polyetheretherketone–hydroxyapatite biocomposite blends. Biomaterials 2003, 24, 3115–3123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zein, I.; Hutmacher, D.W.; Tan, K.C.; Hin, S. Teoh Fused deposition modeling of novel scaffold architectures for tissue engineering applications. Biomaterials 2002, 23, 1169–1185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vozzi, G.; Previti, A.; De Rossi, D.; Ahluwalia, A. Microsyringe-based deposition of two-dimensional and three-dimensional polymer scaffolds with a well-defned geometry for application to tissue engineering. Tissue Eng. 2002, 8, 1089–1098. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moses, J.C.; Nandi, S.K.; Mandal, B.B. Multifunctional cell instructive silk-bioactive glass composite reinforced scaffolds toward osteoinductive, proangiogenic, and resorbable bone grafts. Adv. Healthc. Mater. 2018, 7, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mandal, B.B.; Kundu, S.C. Osteogenic and adipogenic differentiation of rat bone marrow cells on non-mulberry and mulberry silk gland fibroin 3D scaffolds. Biomaterials 2009, 30, 5019–5030. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leukers, B.; Gülkan, H.; Irsen, S.H.; Milz, S.; Tille, C.; Schieker, M.; Seitz, H. Hydroxyapatite scaffolds for bone tissue engineering made by 3D printing. J. Mater. Sci. Mater. Med. 2005, 16, 1121–1124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, L.; Liu, J.; Wang, M.; Min, S.; Cai, Y.; Zhu, L.; Yao, J. Preparation and characterization of nano-hydroxyapatite/silk fibroin porous scaffolds. J. Biomater. Sci. Polym. Ed. 2008, 19, 325–338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Kim, U.-J.; Blasioli, D.J.; Kim, H.-J.; Kaplan, D.L. In vitro cartilage tissue engineering with 3D porous aqueous-derived silk scaffolds and mesenchymal stem cells. Biomaterials 2005, 26, 7082–7094. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lovett, M.; Eng, G.; Kluge, J.A.; Cannizzaro, C.A.; Vunjak-Novakovick, G.; Kaplan, D.L. Tubular silk scaffolds for small diameter vascular grafts. Organogenesis 2010, 6, 217–224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McClure, M.J.; Simpson, D.G.; Bowlin, G.L. Tri-layered vascular grafts composed of polycaprolactone, elastin, collagen, and silk: Optimization of graft properties. J. Mech. Behav. Biomed. Mater. 2012, 10, 48–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Altman, G.H.; Diaz, F.; Jakuba, C.; Calabro, T.; Horan, R.L.; Chen, J.; Lu, H.; Richmond, J.; Kaplan, D.L. Silk-based biomaterials. Biomaterials 2003, 24, 401–416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patra, C.; Talukdar, S.; Novoyatleva, T.; Velagala, S.R.; Mühlfeld, C.; Kundu, B.; Kundu, S.C.; Engel, F.B. Silk protein fibroin from Antheraea mylitta for cardiac tissue engineering. Biomaterials 2012, 33, 2673–2680. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhaarathy, V.; Venugopal, J.; Gandhimathi, C.; Ponpandian, N.; Mangalaraj, D.; Ramakrishna, S. Biologically improved nanofibrous scaffolds for cardiac tissue engineering. Mater. Sci. Eng. C 2014, 44, 268–277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cirillo, B.; Morra, M.; Catapano, G. Adhesion and function of rat liver cells adherent to silk fbroin/collagen blend films. Int. J. Artif. Organs 2004, 27, 60–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- She, Z.; Liu, W.; Feng, Q. Silk fibroin/chitosan/heparin scaffold: Preparation, antithrombogenicity and culture with hepatocytes. Polym. Int. 2010, 59, 55–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lv, Q.; Hu, K.; Feng, Q.; Cui, F.; Cao, C. Preparation and characterization of PLA/fibroin composite and culture of HepG2 (human hepatocellular liver carcinoma cell line) cells. Compos. Sci. Technol. 2007, 67, 3023–3030. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manchineella, S.; Thrivikraman, G.; Khanum, K.K.; Ramamurthy, P.C.; Basu, B.; Govindaraju, T. Pigmented silk nanofibrous composite for skeletal muscle tissue engineering. Adv. Mater. 2016, 5, 1222–1232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Altman, G.H.; Horan, R.L.; Lu, H.H.; Moreau, J.; Martin, I.; Richmond, J.C.; Kaplan, D.L. Silk matrix for tissue engineered anterior cruciate ligaments. Biomaterials 2002, 23, 4131–4141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hennecke, K.; Redeker, J.; Kuhbier, J.W.; Strauss, S.; Allmeling, C.; Kasper, C.; Reimers, K.; Vogt, P.M. Bundles of spider silk, braided into sutures, resist basic cyclic tests: Potential use for flexor tendon repair. PLoS ONE 2013, 8, e61100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, S.-H.; Gil, E.S.; Cho, H.; Mandal, B.B.; Tien, L.W.; Min, B.-H.; Kaplan, D.L. Intervertebral disk tissue engineering using biphasic silk composite scaffolds. Tissue Eng. Part A 2012, 18, 447–458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mandal, B.V.; Park, S.-H.; Gil, W.S.; Kaplan, D.L. Stem cell-based meniscus tissue engineering. Tissue Eng. Part A 2011, 17, 2749–2761. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mandal, B.V.; Park, S.-H.; Gil, W.S.; Kaplan, D.L. Multilayered silk scaffolds for meniscus tissue engineering. Biomaterials 2011, 32, 639–651. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Kong, Y.; Zhao, Y.; Feng, Q.; Wu, Y.; Tang, X.; Gu, X.; Yang, Y. Electrospun, reinforcing network-containing, silk fibroin-based nerve guidance conduits for peripheral nerve repair. J. Biomater. Tissue Eng. 2016, 6, 53–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davis, N.E.; Beenken-Rothkopf, L.N.; Mirsoian, A.; Kojic, N.; Kaplan, D.L.; Barron, A.E.; Fontaine, M.J. Enhanced function of pancreatic islets co-encapsulated with ECM proteins and mesenchymal stromal cells in a silk hydrogel. Biomaterials 2012, 33, 6691–6697. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, X.-W.; Liang, H.; Li, Z.; Zhou, J.; Chen, X.; Bai, S.-M.; Yang, H.-H. Monodisperse phase transfer and surface bioengineering of metal nanoparticles via a silk fibroin protein corona. Nanoscale 2017, 9, 2695–2700. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wenk, E.; Merkle, H.P.; Meinel, L. Silk fibroin as a vehicle for drug delivery applications. J. Control. Release 2011, 150, 128–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Yucel, T.; Lu, Q.; Hu, X.; Kaplan, D.L. Silk nanospheres and microspheres from silk/pva blend films for drug delivery. Biomaterials 2010, 31, 1025–1035. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tian, Y.; Jiang, X.; Chen, X.; Shao, Z.; Yang, W. Doxorubicin-loaded magnetic silk fibroin nanoparticles for targeted therapy of multidrug-resistant cancer. Adv. Mater. 2014, 26, 7393–7398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mitropoulos, A.N.; Perotto, G.; Kim, S.; Marelli, B.; Kaplan, D.L.; Omenetto, F.G. Synthesis of Silk Fibroin Micro- and Submicron Spheres Using a Co-Flow Capillary Device. Adv. Mater. 2014, 26, 1105–1110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, Y.; Liu, F.; Chen, Y.; Yu, T.; Lou, D.; Gao, Y.; Li, P.; Wang, Z.; Ran, H. Drug release from core-shell PVA/ silk fibroin nanoparticles fabricated by one-step electrospraying. Sci. Rep. 2017, 7, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xia, X.-X.; Wang, M.; Lin, Y.; Xu, Q.; Kaplan, D.L. Hydrophobic Drug-Triggered Self-Assembly of Nanoparticles from Silk-Elastin-Like Protein Polymers for Drug Delivery. Biomacromolecules 2014, 15, 908–914. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cheema, S.K.; Gobin, A.S.; Rhea, R.; Lopez-Berestein, G.; Newman, R.A.; Mathur, A.B. Silk fibroin mediated delivery of liposomal emodin to breast cancer cells. Int. J. Pharm. 2007, 341, 221–229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tan, P.H.S.; Aung, K.Z.; Toh, S.L.; Goh, J.C.H.; Nathan, S.S. Three-dimensional porous silk tumor constructs in the approximation of in vivo osteosarcoma physiology. Biomaterials 2011, 32, 6131–6137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sontheimer-Phelps, A.; Hassel, B.A.; Ingber, D.E. Modelling cancer in microfuidic human organs-on-chips. Nat. Rev. Cancer 2019, 15, 65–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tao, H.; Marelli, B.; Yang, M.; An, B.; Onses, M.S.; Rogers, J.A.; Kaplan, D.L.; Omenetto, F.G. Inkjet printing of regenerated silk fibroin: From printable forms to printable functions. Adv. Mater. 2015, 27, 4273–4279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Burrs, S.L.; Vanegas, D.C.; Bhargava, M.; Mechulan, N.; Hendershot, P.; Yamaguchi, H.; Gomesd, C.; McLamore, E.S. A comparative study of graphene–hydrogel hybrid bionanocomposites for biosensing. Analyst 2015, 140, 1466–1476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tao, H.; Brenckle, M.A.; Yang, M.; Zhang, J.; Liu, M.; Siebert, S.M.; Averitt, R.D.; Mannoor, M.S.; McAlpine, M.C.; Rogers, J.A.; et al. Silk-based conformal, adhesive, edible food sensors. Adv. Mater. 2012, 24, 1067–1072. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khalid, A.; Mitropoulos, A.N.; Marelli, B.; Simpson, D.A.; Tran, P.A.; Omenetto, F.G.; Tomljenovic-Hanic, S. Fluorescent nanodiamond silk fibroin spheres: Advanced nanoscale bioimaging tool. ACS Biomater. Sci. Eng. 2015, 1, 1104–1113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, H.; Teng, C.P.; Huang, D.; Xu, W.; Zheng, C.; Chen, Y.; Liu, M.; Yang, D.-P.; Lin, M.; Li, Z.; et al. Microwave assisted synthesis of luminescent carbonaceous nanoparticles from silk fibroin for bioimaging. Mater. Sci. Eng. C 2017, 1, 616–623. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roy, M.; Kusurkar, T.S.; Maurya, S.K.; Meena, S.K.; Singh, S.K.; Sethy, N.; Bhargava, K.; Sharma, R.K.; Goswami, D.; Sarkar, S.; et al. Graphene oxide from silk cocoon: A novel magnetic fluorophore for multi-photon imaging. 3 Biotech 2014, 4, 67–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Marelli, B.; Brenckle, M.A.; Kaplan, D.L.; Omenetto, F.G. Silk fibroin as edible coating for perishable food preservation. Sci. Rep. 2016, 6, 25263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Valentini, L.; Bittolo Bon, S.; Pugno, N.M. Combining living microorganisms with regenerated silk provides nanofibril-based thin films with heat-responsive wrinkled states for smart food packaging. Nanomaterials 2018, 8, 518. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Joseph, B.; Raj, J. Therapeutic applications and properties of silk proteins from Bombyx mori. Front. Life Sci. 2013, 6, 55–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seul, G.K. Manufacturing method of baby food having silk protein. Korean patent, KR101882229(B1), granted: 26 July 2018.

- Ji, S.D.; Kim, K.Y.; Kim, N.S.; Kweon, H.Y.; Kang, P.D.; Kim, M.J.; Ko, Y.H.; Kim, A.Y. Rural Dev Administration (Rura-C) Univ Hallym Ind Academic Coop Found (Uyhm-C) (2017) Composition comprising silkworm having silk protein for preventing or treating Parkinson’s disease. South Korean Patent, KR101793552B1, granted: November 3.

- Grayson, A.C.R.; Shawgo, R.S.; Jhonson, A.M.; Flynn, N.T.; Li, Y.; Cima, M.J.; Langer, R. MEMS technology for physiologically integrated devices. Proc. IEEE 2004, 92, 6–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hwang, S.-W.; Tao, H.; Kim, D.-H.; Cheng, H.; Song, J.-K.; Rill, E.; Brenckle, M.A.; Panilaitis, B.; Won, S.M.; Kim, Y.-S.; et al. A physically transient form of silicon electronics. Science 2012, 337, 1640–1644. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tao, H.; Hwang, S.-W.; Marelli, B.; An, B.; Moreau, J.E.; Yang, M.; Brenckle, M.A.; Kim, S.; Kaplan, D.L.; Rogers, J.A.; et al. Silk-based resorbable electronic devices for remotely controlled therapy and in vivo infection abatement. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2014, 111, 17385–17389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, S.; Dong, C.; Lu, G.; Lu, Q.; Li, Z.; Kaplan, D.L.; Zhu, H. Bilayered vascular grafts based on silk proteins. Acta Biomater. 2013, 9, 8991–9003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, M.; Yu, J.H.; Kaplan, D.L.; Rutledge, G.C. Production of submicron diameter silk fibers under benign processing conditions by two-fluid electrospinning. Macromolecules 2006, 39, 1102–1107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gil, E.S.; Panilaitis, B.; Bellas, E.; Kaplan, D.L. Functionalized silk biomaterials for wound healing. Adv. Healthc. Mater. 2012, 2, 206–217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Youyi Xia, Guoan Gao, Yuewu Li Preparation and properties of nanometer titanium dioxide/silk fibroin blend membrane. J. Biomed. Mater. Res. 2009, 90, 653–658.

- Kanokpanont, S.; Damrongsakkul, S.; Ratanavaraporn, J.; Aramwit, P. Physico-chemical properties and efficacy of silk fibroin fabric coated with different waxes as wound dressing. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2013, 55, 88–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- K Hoon Lee, Doo Hyun Baek, Chang Seok Ki, Young Hwan Park Preparation and characterization of wet spun silk fibroin/poly (vinyl alcohol) blend filaments. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2007, 41, 168–172. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sultan, M.T.; Moon, B.M.; Yang, J.W.; Lee, O.J.; Kim, S.H.; Lee, J.S.; Lee, Y.J.; Seo, Y.B.; Kim, D.Y.; Ajiteru, O.; et al. Recirculating peritoneal dialysis system using urease-fixed silk fibroin membrane filter with spherical carbonaceous adsorbent. Mater. Sci. Eng. 2019, 97, 55–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Janani, G.; Nandi, S.K.; Biman, B. Mandal Functional hepatocyte clusters on bioactive blend silk matrices towards generating bioartifcial liver constructs. Acta Biomater. 2018, 67, 167–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sheng, J.Y.; Xu, J.; Zhuang, Y.; Sun, D.Q.; Xing, T.; Chen, G.Q. Study on the application of sericin in cosmetics. Adv. Biomater. Res. 2013, 796, 416–423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Daithankar, A.V.; Padamwar, M.N.; Pisal, S.; Mahadik, K.R. Moisturizing efficiency of silk protein hydrolysate: Silk fibroin. Indian J. Biotechnol. 2005, 4, 115–121. [Google Scholar]

- Das, G.; Shin, H.-S.; Campos, E.V.R.; Fraceto, L.F.; Rodriguez-Torres, M.D.P.; Mariano, K.C.F.; de Araujo, D.R.; Fernández-Luqueño, F.; Grillo, R.; Patra, J.K. Sericin based nanoformulations: A comprehensive review on molecular mechanisms of interaction with organisms to biological applications. J. Nanobiotechnology 2021, 19, 1–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yamada, H.; Yamasaki, K.; Zozaki, K. (2007). Nail cosmetics containing sericin. European Patent, EP1632214B1, granted: October 3.

- Jaime, A. Barajas-Gamboa, Angélica M Serpa-Guerra, Adriana Restrepo-Osorio, Catalina Álvarez-López Sericin applications: A globular silk protein. Ing. Y Compet. 2016, 18, 193–205. [Google Scholar]

- Koley, P.; Sakurai, M.; Takeia, T.; Aono, M. Facile fabrication of silk protein sericin-mediated hierarchical hydroxyapatite-based bio-hybrid architectures: Excellent adsorption of toxic heavy metals and hazardous dye from wastewater. RSC Adv. 2016, 6, 86607–86616. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Andrade, J.R.; da Silva, M.G.C.; Gimenes, M.L.; Vieira, M.G.A. Bioadsorption of trivalent and hexavalent chromium from aqueous solutions by sericin-alginate particles produced from Bombyx mori cocoons. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. Int. 2018, 25, 25967–25982. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Min, K.; Kim, S.; Kim, S. Silk protein nanofibers for highly efficient, eco-friendly, optically translucent, and multifunctional air filters. Nat. Sci. Rep. 2018, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gao, X.; Gao, J.; Zhang, L.; Duan, S.; Li, C. A silk fibroin based green nano-filter for air filtration. RSC Adv. 2018, 8, 8181–8189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).