1. Introduction

The extensive root system allows plants to take up almost all nutrients from the soil, which makes soil fertilization the basic way of their nutrition. The availability of minerals depends on many factors. The main ones are the type of soil, the content of organic matter, the pH and the course of climatic conditions. These factors, by inducing microbiological and chemical processes in the soil, affect their uptake [

1].

Fruit plants are perennial plants, which means that they are characterized by lower nutritional requirements than annual plants. It is caused by a much larger and more durable root system, as well as the ability to store nutrients in permanent organs such as roots, trunk, branches, shoots, and buds. Fruit plants can meet nutritional needs even with a low concentration of nutritional compounds. The annual increase in stocks is difficult to estimate because it is impossible to calculate how many components collected were used to build new tissues and how much was ‘in stock’ [

2,

3]. Some of the collected components return to the soil with fallen leaves and cut shoots, and other parts removed during agrotechnical work, such as flowers or fruit buds [

4]. Orchard species differ in the demand for nitrogen. It depends mainly on the nitrogen content in the fruit and the weight of the entire crop relative to the weight of the rest of the plant. The least nitrogen contains apples because about 0.9g for each kg and the most kiwi, because as much as 4.5 g per kg of fruit[

3]. Assuming that the average kiwi yield is approximately 20 t ha

–1 [

5], it is to compensate for the loss of nitrogen, which results from the yield, fertilization should be 90 kg ha

֪–1. On the other hand, apples, although they contain much less nitrogen, the yield of apple trees is higher. In Poland, on many farms the yield is 50 t ha-1 and in some it may exceed 80 t ha

–1 [

6,

7,

8]. Along with the crop, from 50 to 80 kg of N ha

–1 are taken out from the orchard. Therefore, the amount of nitrogen fertilization should be depend of the yield of trees. According to the integrated cherry cultivation methodology, if for instance due to spring frost is expected lower yield, the dose of nitrogen fertilization should be reduced by 30-50% [

9].

In the cultivation of fruit plants, it is very important to maintain a balance between vegetative growth and fruiting of trees [

10]. This allows for regular and annual fruiting. Excessive nitrogen fertilization increases growth, causes a deterioration in the quality of fruits and their storability [

11]. Nitrogen, on the other hand, increases the weight of the fruit. The market requires the supply of large fruits with very good quality parameters. However, in the case of pome fruits, increasing nitrogen fertilization contributes to the deterioration of colour and greater sensitivity to storage diseases. Stone species react weaker than pome species to high nitrogen fertilization [

11]. This is due to an imbalance of minerals in the plant, which interferes with the growth and yield of trees. Nitrogen fertilization contributes to a greater sensitivity of fruits to storage diseases. Therefore, the amount of nitrogen fertilization should be dependent of the expected yield in a given year [

3], which depends on the course of the weather conditions [

12,

13]. It is recommended to divide the planned dose of nitrogen fertilization into 2 or 3 parts. This allows you to modify fertilization if there are factors limiting fruiting, e.g. frost or weather unfavourable for pollination during flowering [

3].

Nitrogen is a necessary element for the proper development of plants, however is very mobile in the soil. The use of too high doses can lead to losses of this component due to leaching and contamination of groundwater [

14]. Excessive use of nitrogen fertilisers can lead to high nitrate concentrations in the soil and then their leaching into groundwater [

15,

16]. Therefore, optimal nitrogen fertilization must be adjusted to ensure a high yield with the lowest possible fertilizer dose [

17].

High nitrogen fertilization also increases susceptibility to diseases by stimulating vegetative growth [

3]. In cherry orchards, the amount of recommended dose of fertilizer depends on the organic matter. The higher the content of organic matter, the lower the dose should be applied. According to the recommendations in cherry orchards fully fruiting, where the content of organic matter in the soil is in the range of 0.5-1.5%, the annual dose of nitrogen should be between 60 and 80 kg N ha

-1 [

18]. With a yield per hectare of full fruiting (yield 15 t ha

–1), approx. 45 kg N [

19] is removed from the orchard with the crop. The use of nitrogen applied in early spring by trees is small and usually not exceed more than 10-12 percent. Such a small use means that during flowering there is still a lot of fertilizer nitrogen in the soil and, as research shows, in the apple orchard during the flowering period there was still in the soil nearly 60% nitrogen of applied in spring [

20].

In the early stages of growth, plants use nitrogen taken up and accumulated in tissues in the previous season. The amount of nitrogen stored depends on the age of the tree, size and applied fertilization [

3]. In deciduous trees, before the end of the growing season and leaf fall, nitrogen is withdrawn from the leaves and transferred to the trunk, shoots, older roots, where it is stored and the tree uses it at the beginning of vegetation before it begins to take up from the soil [

21,

22]. In addition, fallen leaves decompose and nitrogen can be reused by the tree after undergoing decomposition and mineralization processes [

23], in the second year after the drop [

24].

The source of nitrogen is probably heterotrophic aerobic bacteria, including, among others, bacteria from the genera

Azotobacter and

Azospirillum. Assimilates N

2 only for the purpose of cell metabolism, so they do not secrete bound N into the environment. Nitrogen enters the soil environment when the bacterial cells die. The amount of nitrogen that is supplied to the soil is estimated at several kilograms of N∙ha

–1 per year [

25]. Despite the small amount, the quantities supplied are of great importance for soil fertility. However, their occurrence and abundance depend on various environmental factors such as organic matter content, moisture, soil reaction, climatic condition. [

26]. For example,

Azotobater is very high in soil pH and rarely occurs in soils with a pH below 6 [

27]. In contrast,

Azospirilllum naturally occurs in regions with warm and or hot climates. In these regions, populations of associative microorganisms in soils are significantly higher than in the soils of our climate zone [

28].

Nitrogen fertilization leads to an increase in the size of the tree and the area of the leaves [

29] and on the other hand, it limits the intensity of flowering [

30]. Trees grown under low nitrogen availability have a lower rate of photosynthesis, which results in a lower yield and fruit size [

31], because photosynthesis is a function of the surface of the leaves, not their mass [

32]. A significant correlation was found between the specific leaf weight (SLA specific leaf area) (leaf weight/area) and the nitrogen content of the leaves [

33].

Nitrogen should be available throughout the growing season, so sorption of mineral nitrogen is important. Plant roots are capable of absorbing nitrogen in the nitrate form (NO

3-), as well as in the ammonium form (NH

4+), but in well-aerated soils, nitrates are the dominant source of nitrogen [

34]. Ammonium nitrogen (NH

4+) as a cation is well absorbed interchangeably, so it does not leach into deeper layers of the soil. In contrast, nitrate nitrogen (NO

3-) as an anion is not subject to biological and exchange sorption. It is washed out into the deeper layers of the soil beyond the reach of the root system [

35]. This causes its loss as a nutrient and is also a source of environmental contamination. Additionally, in the process of oxidation of ammonium ions and their reduction to nitrite, nitrous oxide (N

2O) is formed, which is one of the factors that causes the degradation of the ozone layer in the atmosphere [

36,

37,

38]. One of the recommended solutions to reduce nitrogen loss is to divide the full dose of nitrogen into 2-4 components [

19].

The intensity of photosynthesis is directly proportional to the chlorophyll content in the leaves. Its content of chlorophyll depends on the availability of light, the vigour of tree growth, species, cultivar and rootstock, and stress factors [

39,

40,

41,

42]. The chlorophyll content of the leaves is thickened when poorly lit, than in central part of the crown is on average 1.3 times thickened than in the leaves on the outskirts of the crown [

43]. The higher concentration of green pigments in poorly lit leaves is explained by the mechanism of their adaptation to worse light conditions. Lack of light causes a decrease in the thickness of the leaf blade [

44]. However, conversion of chlorophyll concentrations per m

2 LSA (leaf surface area) shows that leaves from the peripheral part of the crown have the same or higher chlorophyll content as the middle [

43].

The purpose of the study was to evaluate the impact of different doses of nitrogen fertilization on the content of the basic element in the soil and in the leaves and its influence on selected cherry growth parameters.

5. Conclusions

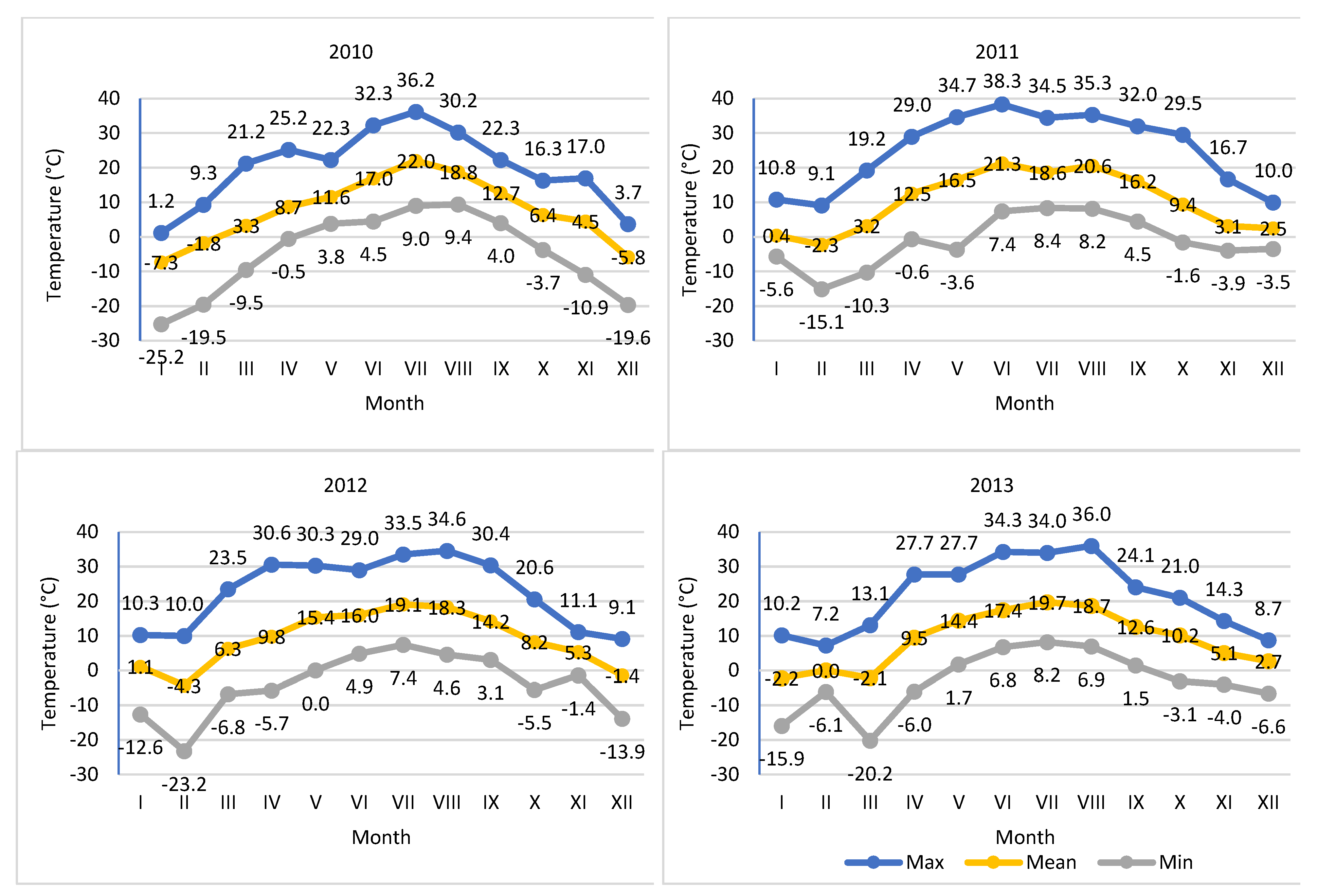

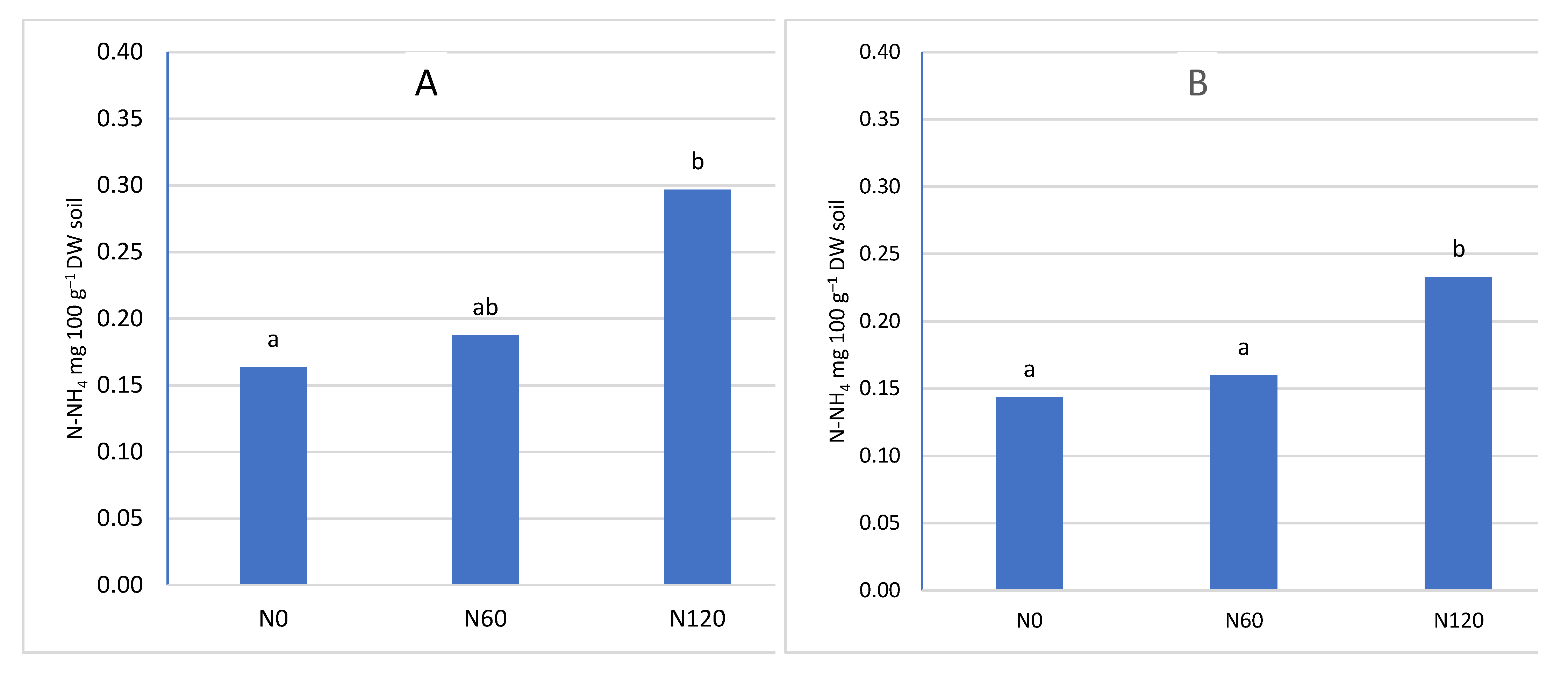

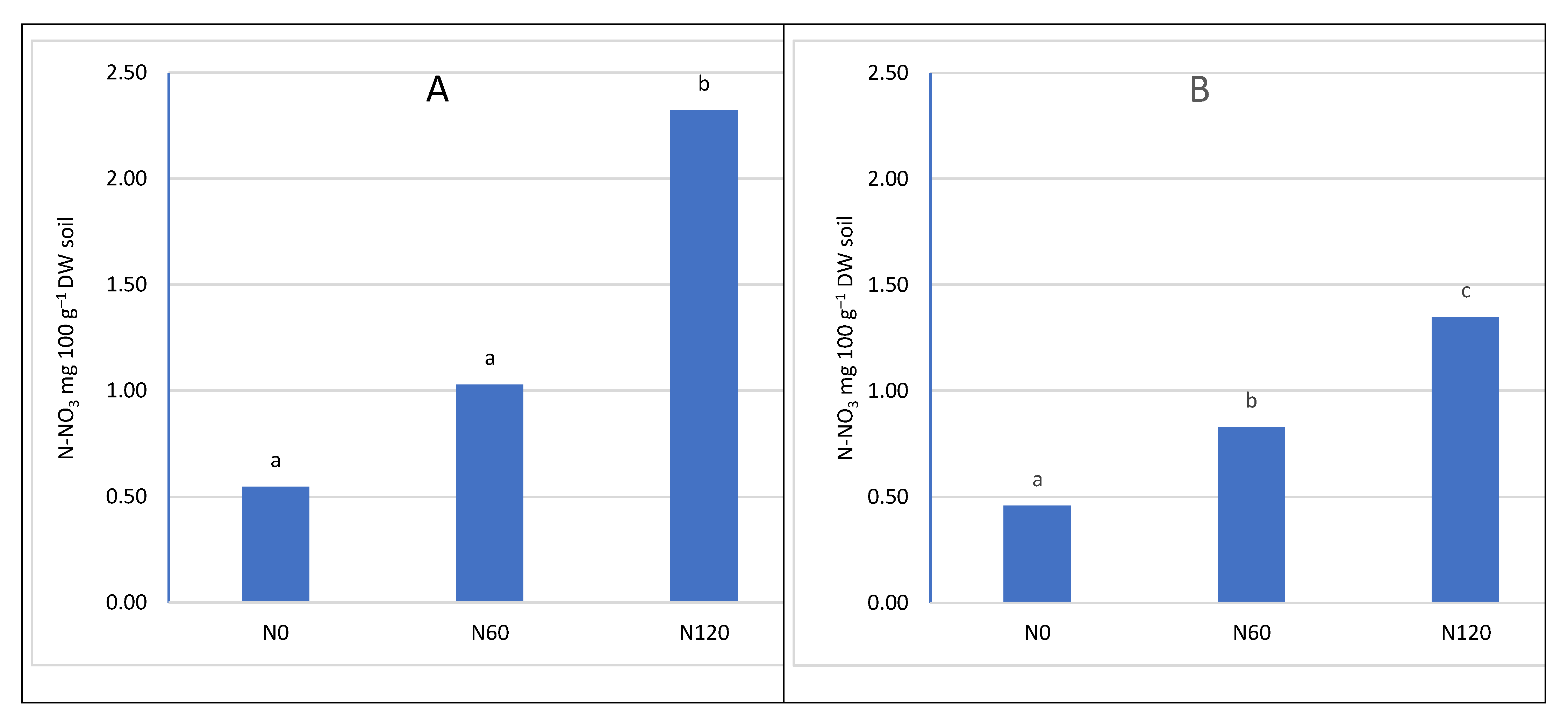

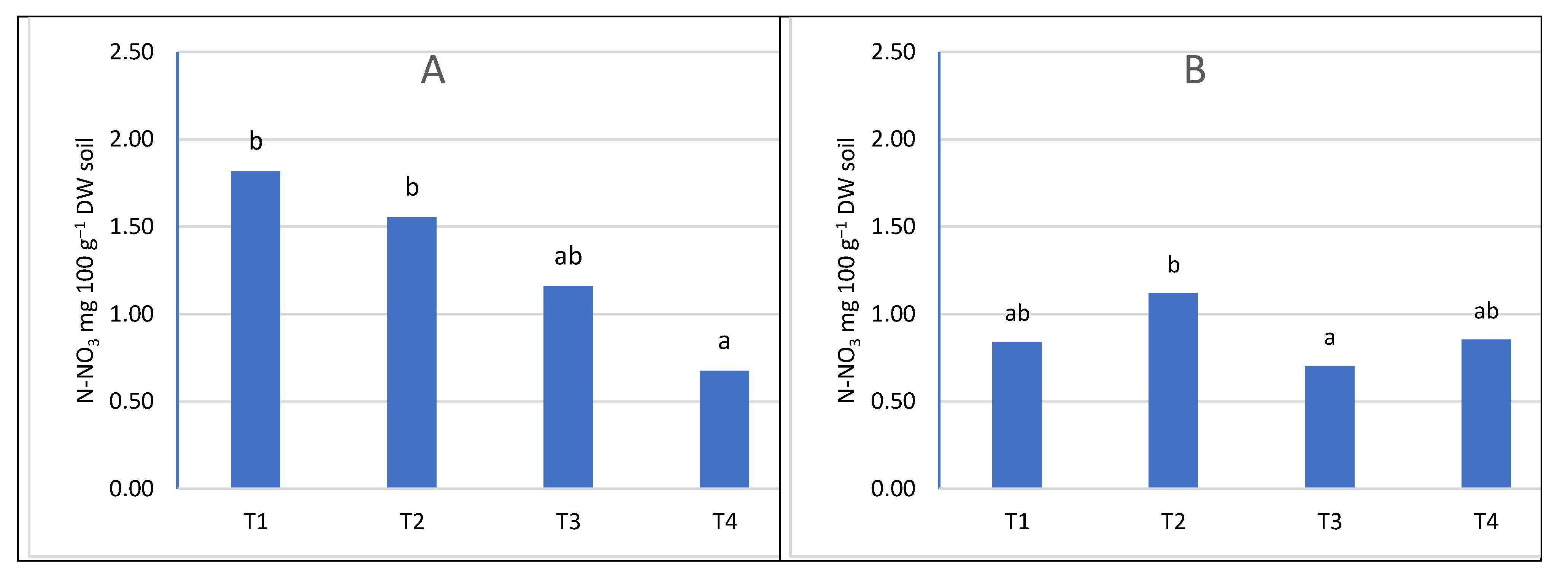

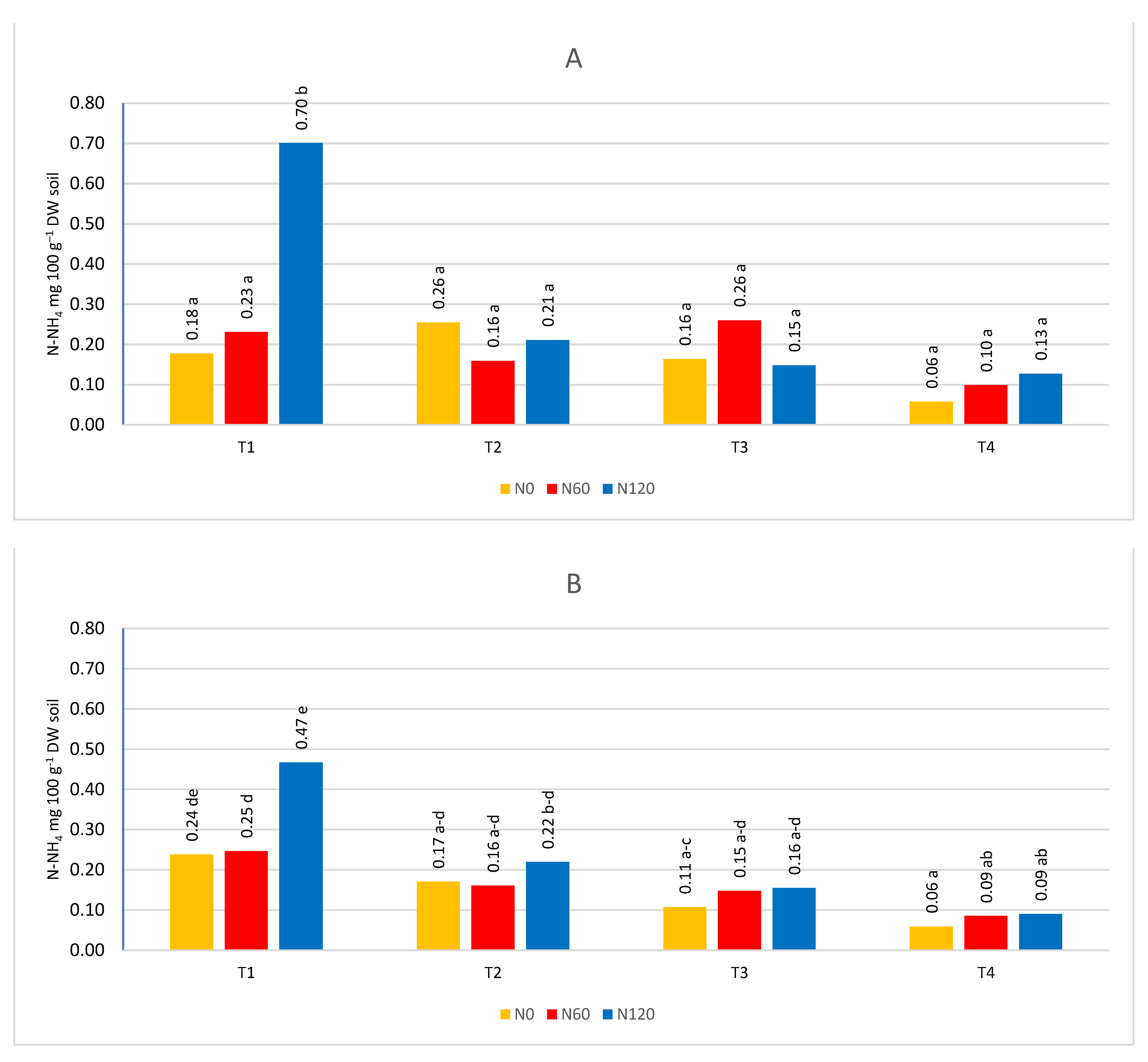

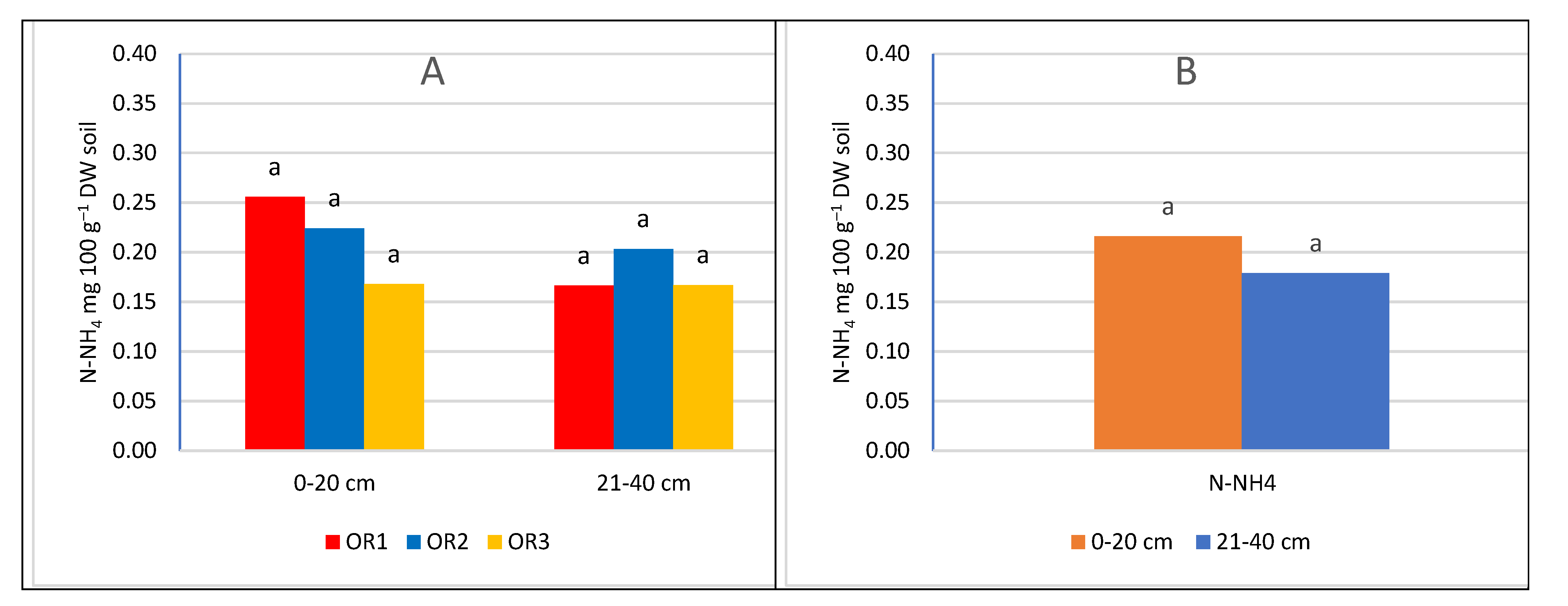

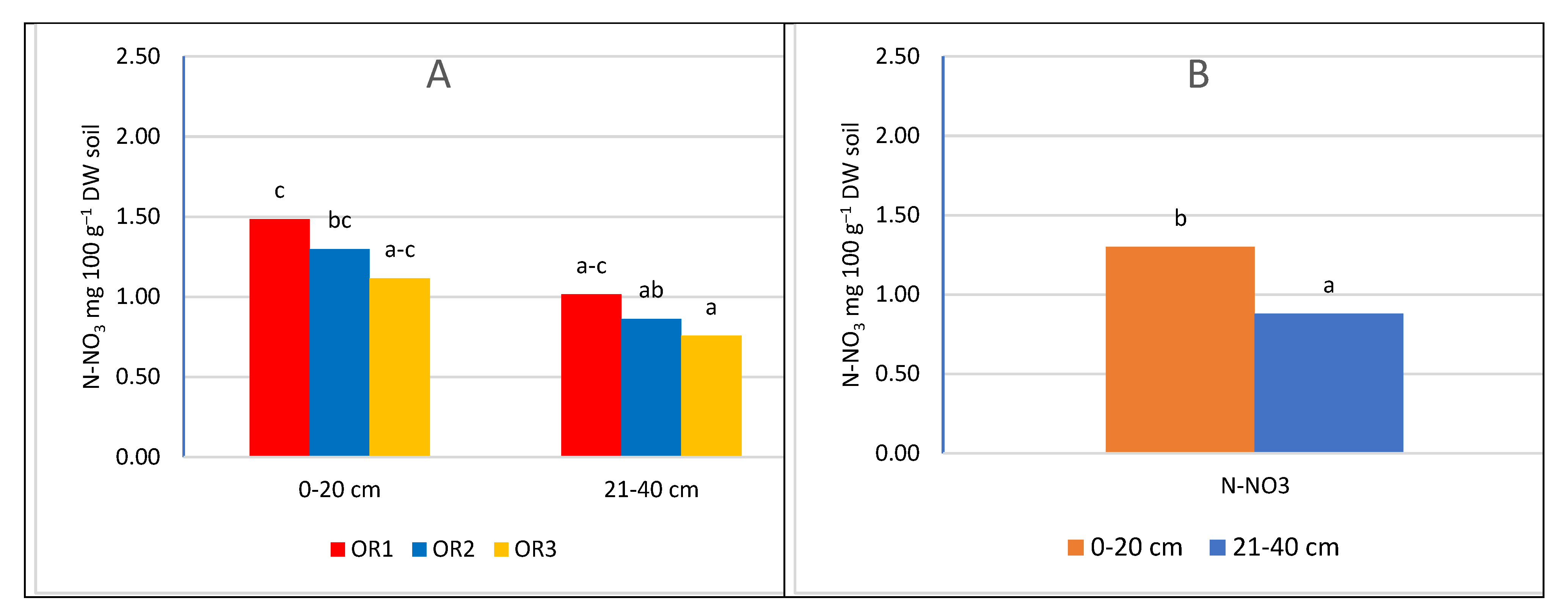

The nitrogen fertilization at the beginning of the growing season had an impact on the content of ammoniacal and nitrate nitrogen in the soil. The nitrogen content is influenced by the course of the weather, but above all by the uptake by trees. These changes are in a sense a reflection of the fertilizer needs of the studied species. The content of N60 and N120 increased the content of ammonium and nitrate forms. However, there was no significant difference between the control (N0) and N60 for the ammonium form of nitrogen. Nitrate nitrogen increased with the applied dose regardless of the sampling level, but only in the subarable layer were the differences between the combinations significant. Probably the use of N60 covered the fertilizer needs of cherry trees. Only the increase in the dose of N120 significantly increased the nitrogen content in the soil.

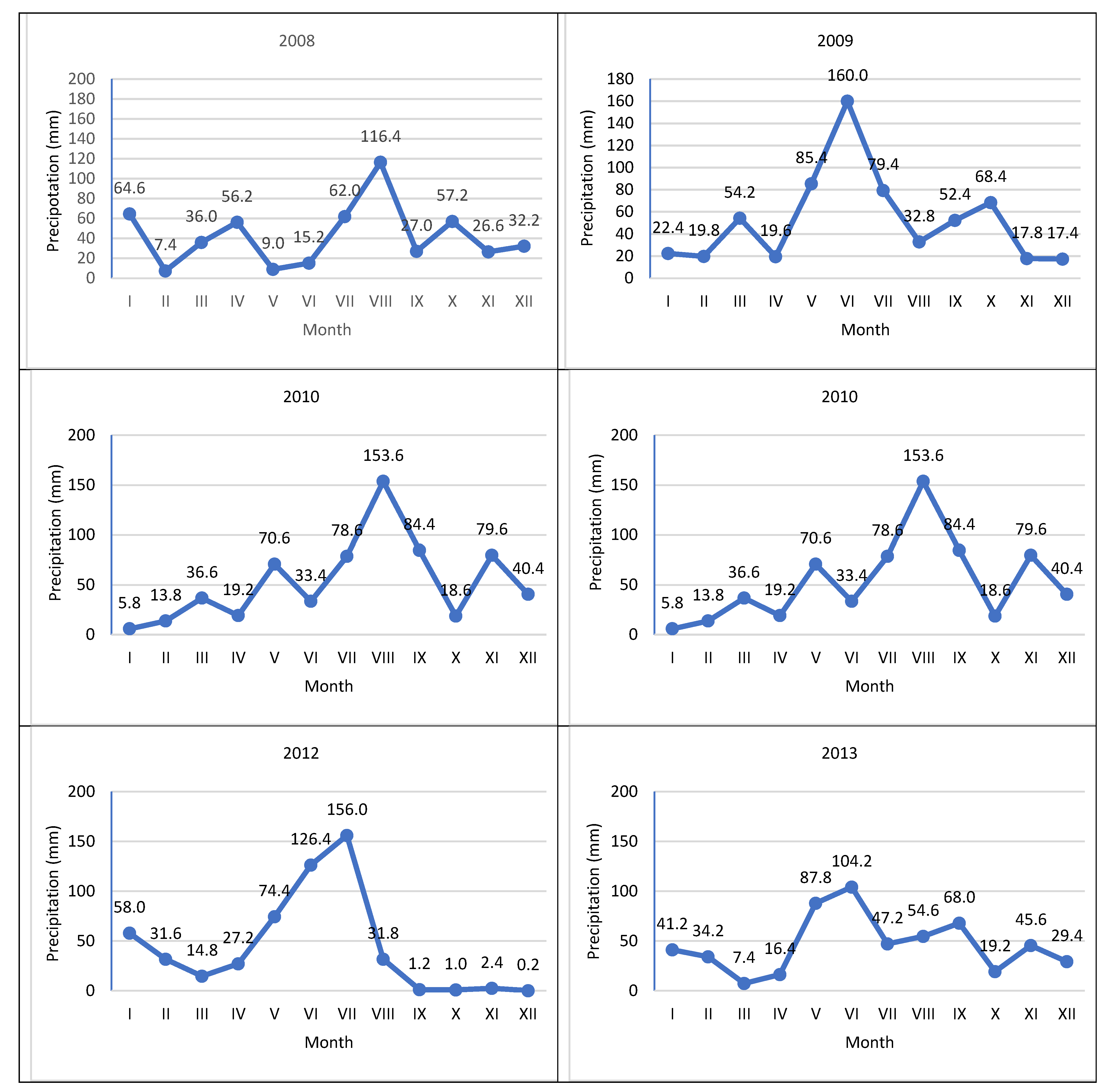

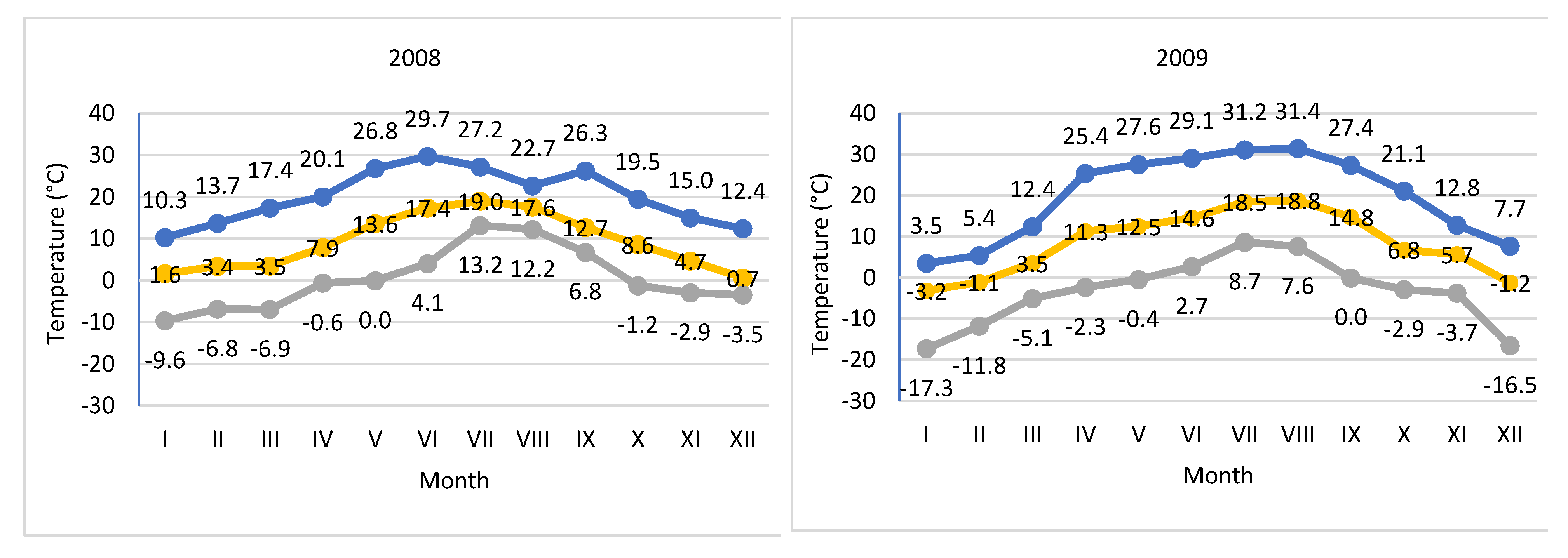

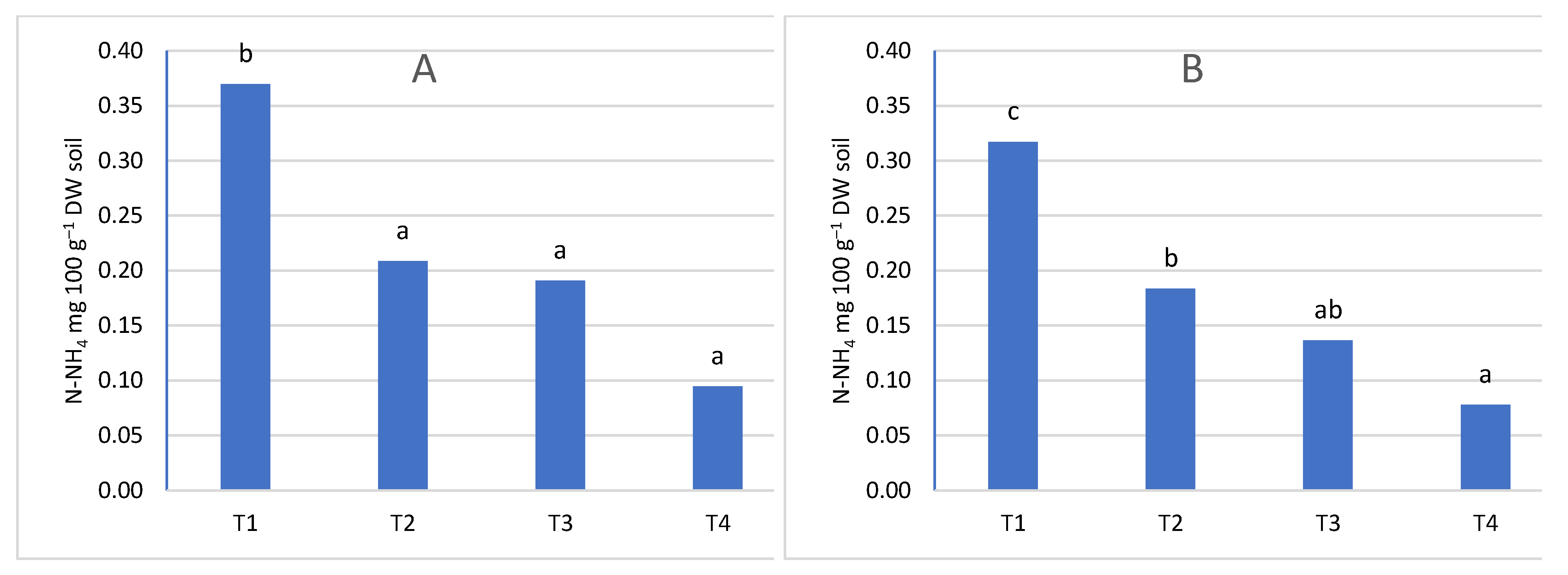

Nitrogen fertilization applied at the beginning of the growing season does not affect the content of nitrogen nitrate and ammonium in the soil. The highest nitrogen content in the soil was found in the first sampling period at the beginning of vegetation, when ammonium nitrate was fertilized. During this time, trees benefit from nitrogen that was accumulated in the tissues of the tree after being taken in the previous season. Nitrogen uptake begins a few weeks after the start of vegetation, when the soil temperature rises to 8–12°C. The ammonium form content decreased on subsequent sampling dates. A similar trend was observed for the nitrate form in the topsoil layer, while in the subarable layer the nitrate nitrogen content varied depending on the timing of the samples. An important factor that influenced the content was the course of climatic conditions, such as precipitation and temperature.

The age of the orchard had no significant effect on the nitrogen content of the soil. Although the lowest values were found in the youngest orchard (OR3). Only the ammonium form in the subarable area was highest in the OR2 orchard.

Regardless of the nitrogen form, the content was higher in the arable layer of the soil, but only for the ammonium form, the difference in content was significant.

High nitrogen fertilization increased the content of phosphorus and potassium and decreased the magnesium content in the topsoil layer, resulting in an increase in the K/Mg ratio. The nitrogen fertilization slightly reduced the pH of the soil in the upper soil layer, but the differences were insignificant. Similar changes were observed in the sublayer for phosphorus and magnesium, while the K level was significantly lower with N60 fertilization and no significant differences were found between the control combination and the highest dose of nitrogen fertilization. The pH of the soil was higher with nitrogen fertilization, but the differences were not significant.

The nitrogen content in the leaves increased with increasing doses of nitrogen fertilization. The content of phosphorus and potassium decreased with increasing nitrogen fertilization. However, the highest magnesium and calcium content was when fertilizing N60 and increasing the dose to N120 reduced its content, which can be explained by stronger vegetative growth and the effect of dilution of ingredients.

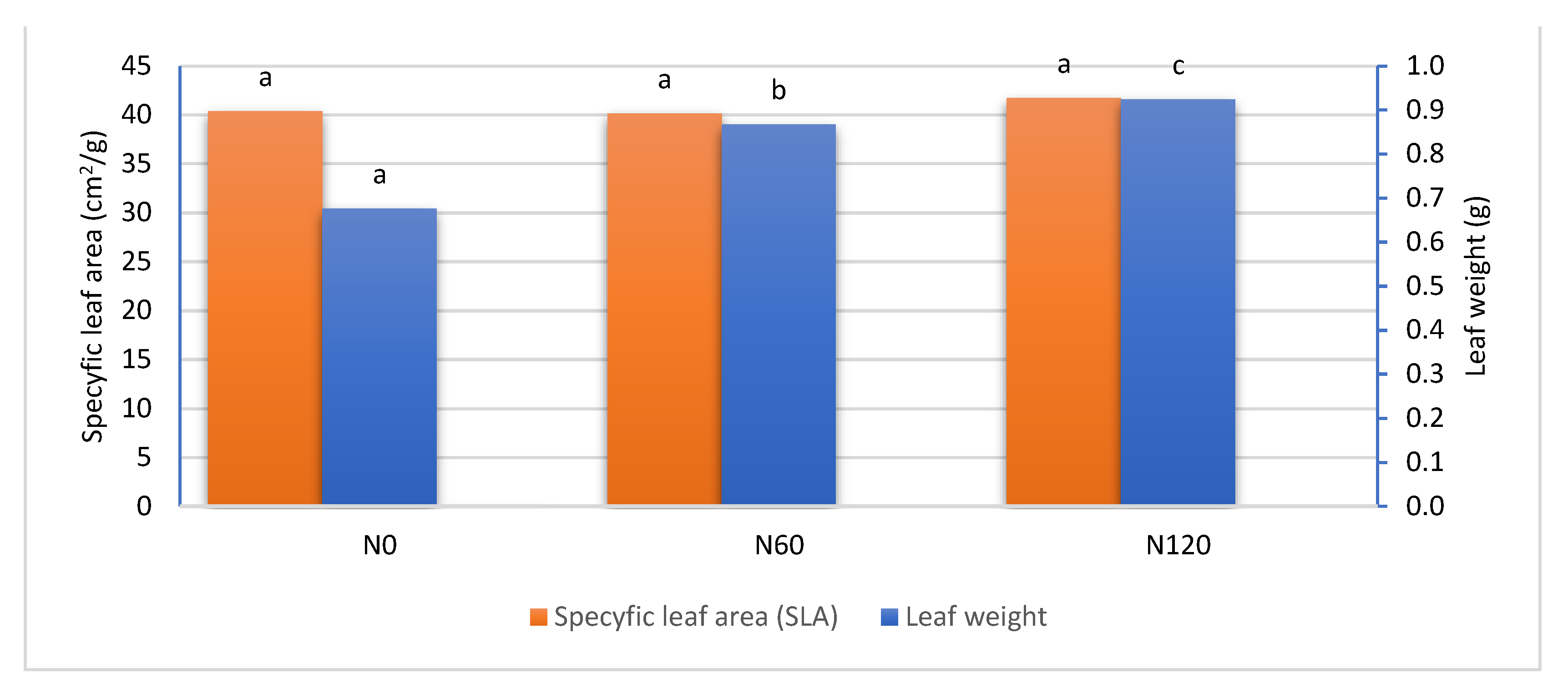

The use of nitrogen fertilization increased the vegetative growth of trees measured by leaf area, trunk cross-sectional area and its growth during the research period. However, SLA (cm2/g) did not differ significantly between combinations, because the thickness of the leaves in the control and fertilized ammonium nitrate combinations was the same, regardless of the dose used.

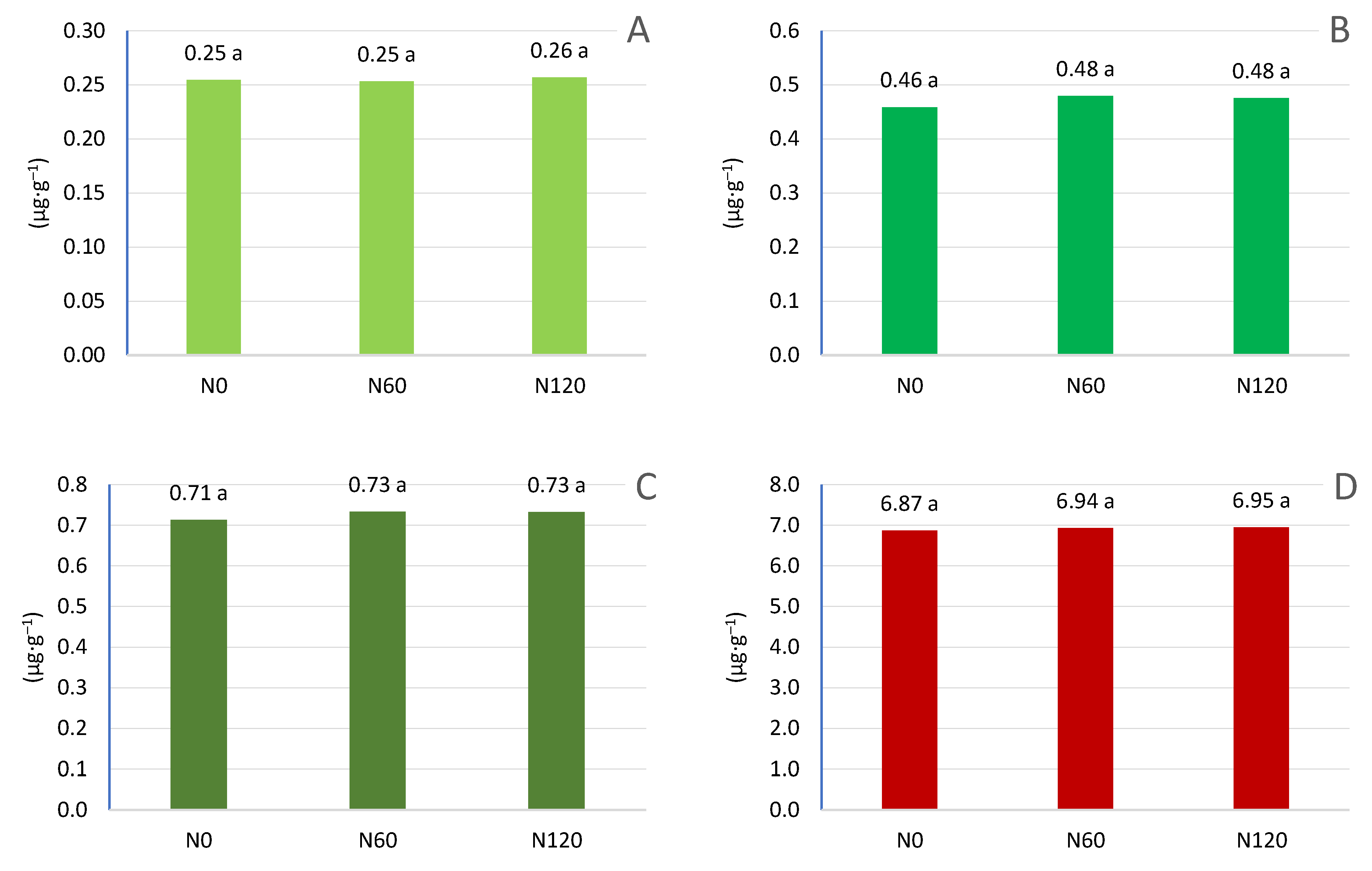

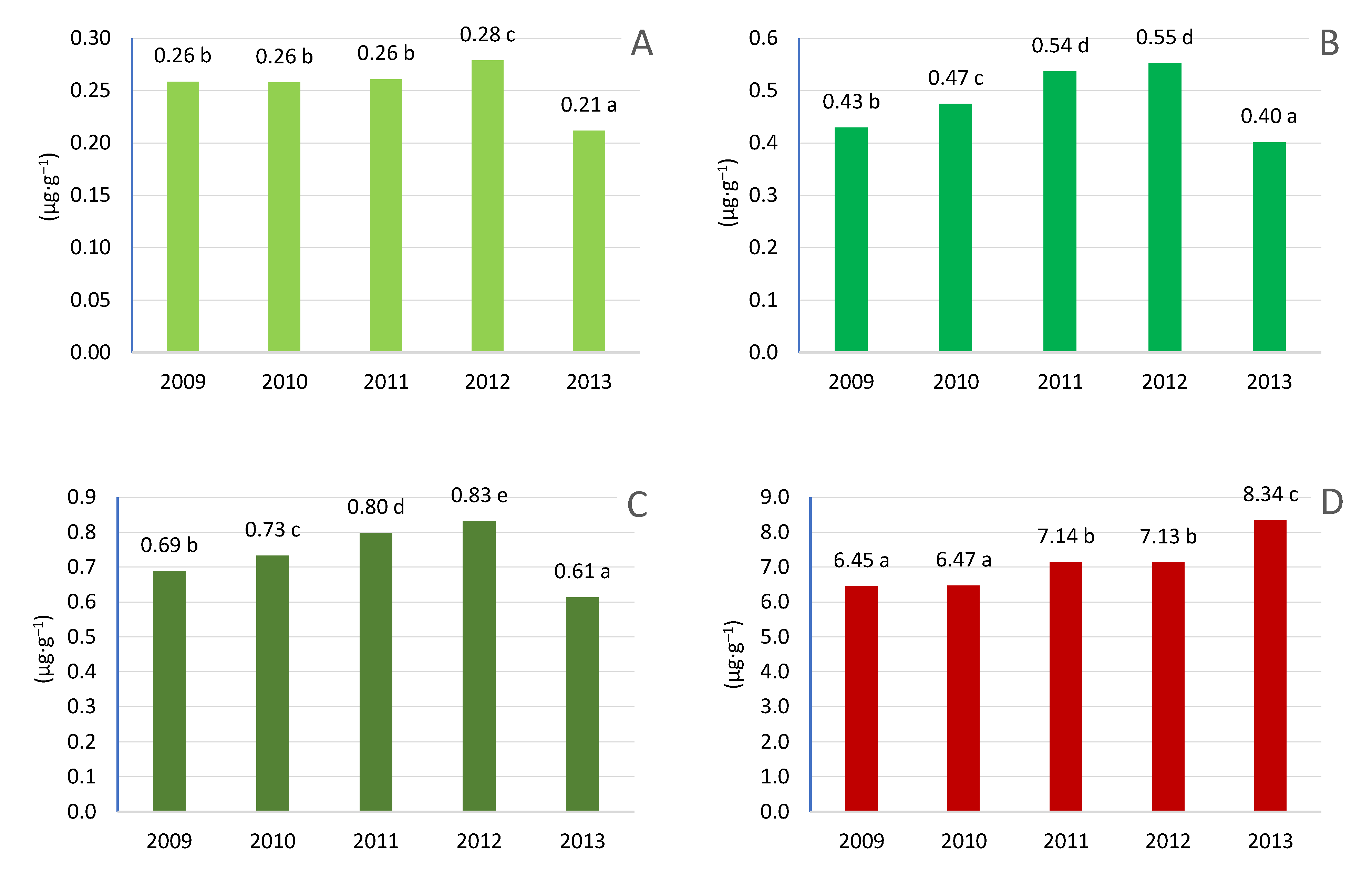

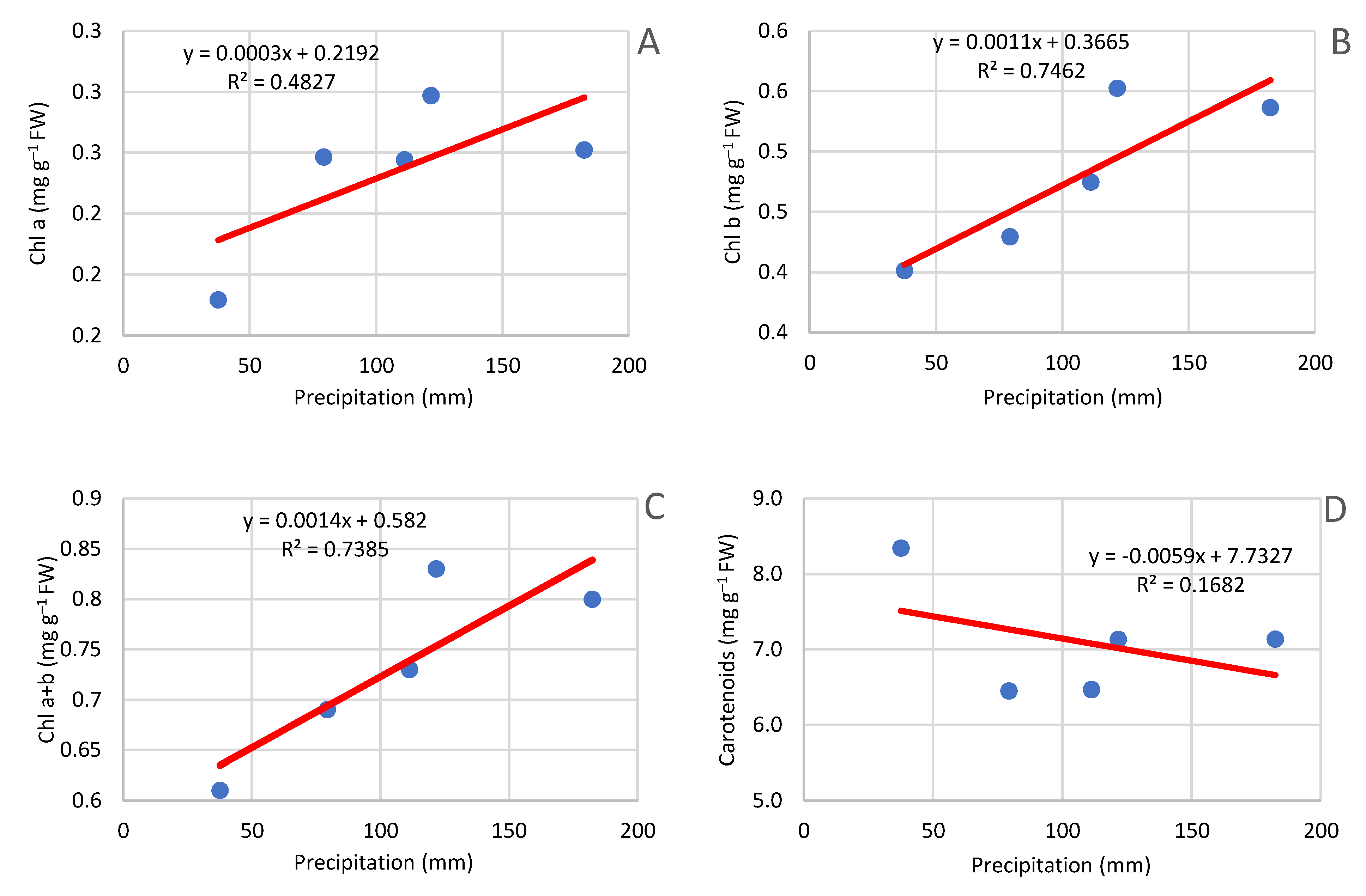

The chlorophyll content was not dependent on the amount of nitrogen fertilization. However, it should be emphasized that the overall chlorophyll content in the leaves was higher with nitrogen fertilization. The course of the climatic conditions, especially precipitation, which caused their growth, had a greater impact on the chlorophyll content. Not without significance is also the intensity of yielding and cutting trees in this cherry variety, which bears fruit on annual shoots and the cutting is carried out in the summer after fruit harvest.

Figure 1.

Precipitation per month in 2008-2013.

Figure 1.

Precipitation per month in 2008-2013.

Figure 2.

Average, actual minimum and maximum temperatures in 2008-2013.

Figure 2.

Average, actual minimum and maximum temperatures in 2008-2013.

Figure 3.

The content of N-NH4 depending on nitrogen fertilization A- in the soil layer 0-20 cm, B- in the soil layer 21-40 cm

Figure 3.

The content of N-NH4 depending on nitrogen fertilization A- in the soil layer 0-20 cm, B- in the soil layer 21-40 cm

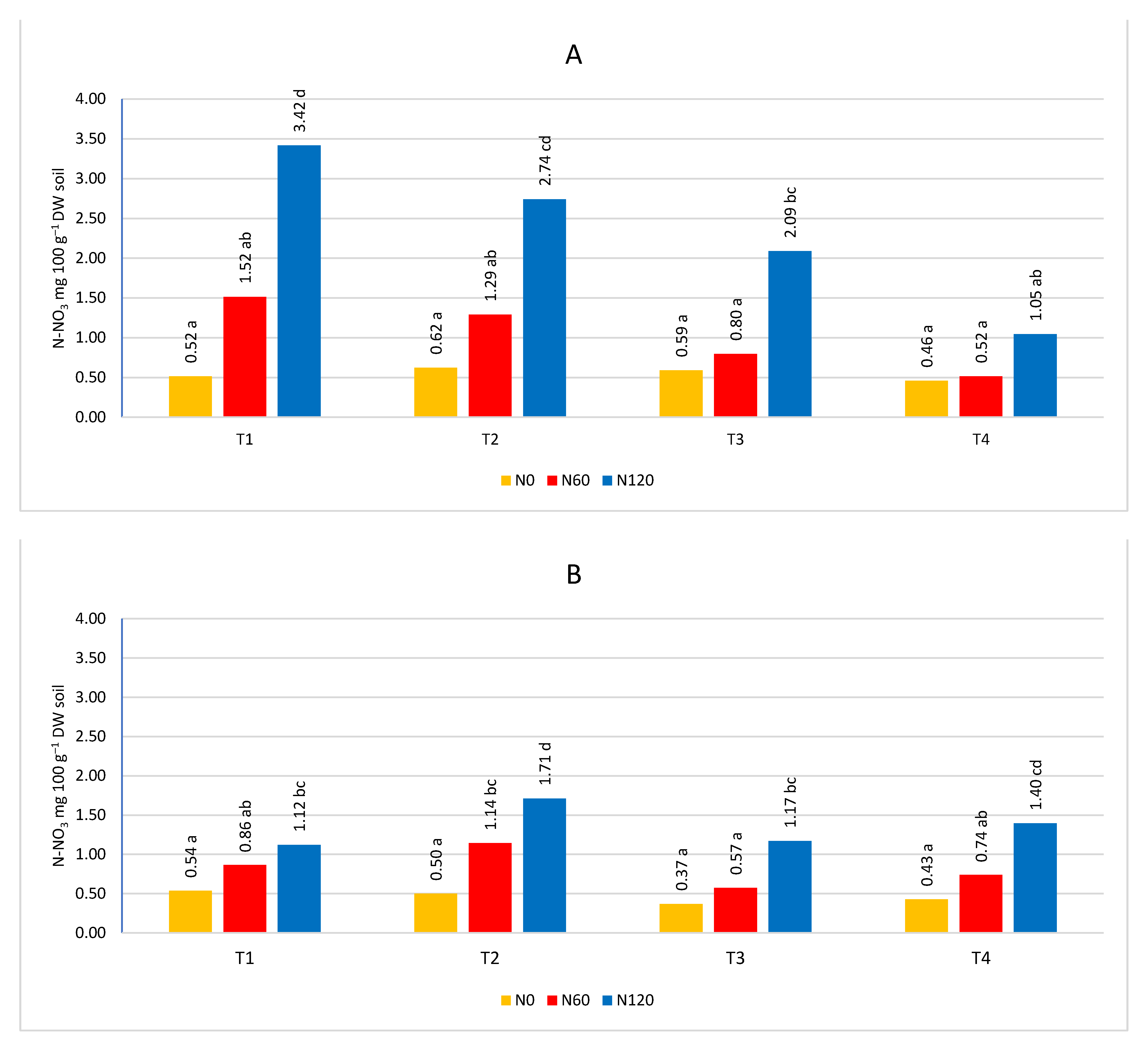

Figure 4.

The content of N-NO3 depending on nitrogen fertilization, A- in the soil layer 0-20 cm, B- in the soil layer 21-40 cm.

Figure 4.

The content of N-NO3 depending on nitrogen fertilization, A- in the soil layer 0-20 cm, B- in the soil layer 21-40 cm.

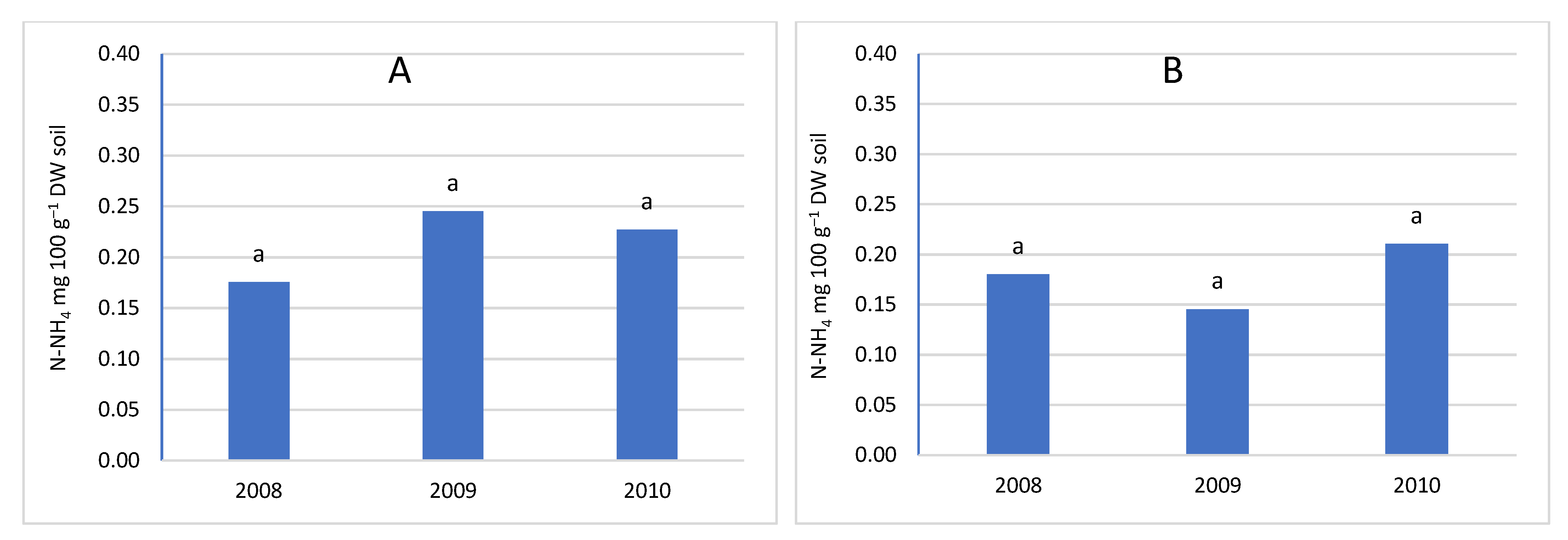

Figure 5.

The content of N-NH4 depends on the date of sampling A- in the soil layer 0-20 cm, B- in the soil layer 21-40 cm.

Figure 5.

The content of N-NH4 depends on the date of sampling A- in the soil layer 0-20 cm, B- in the soil layer 21-40 cm.

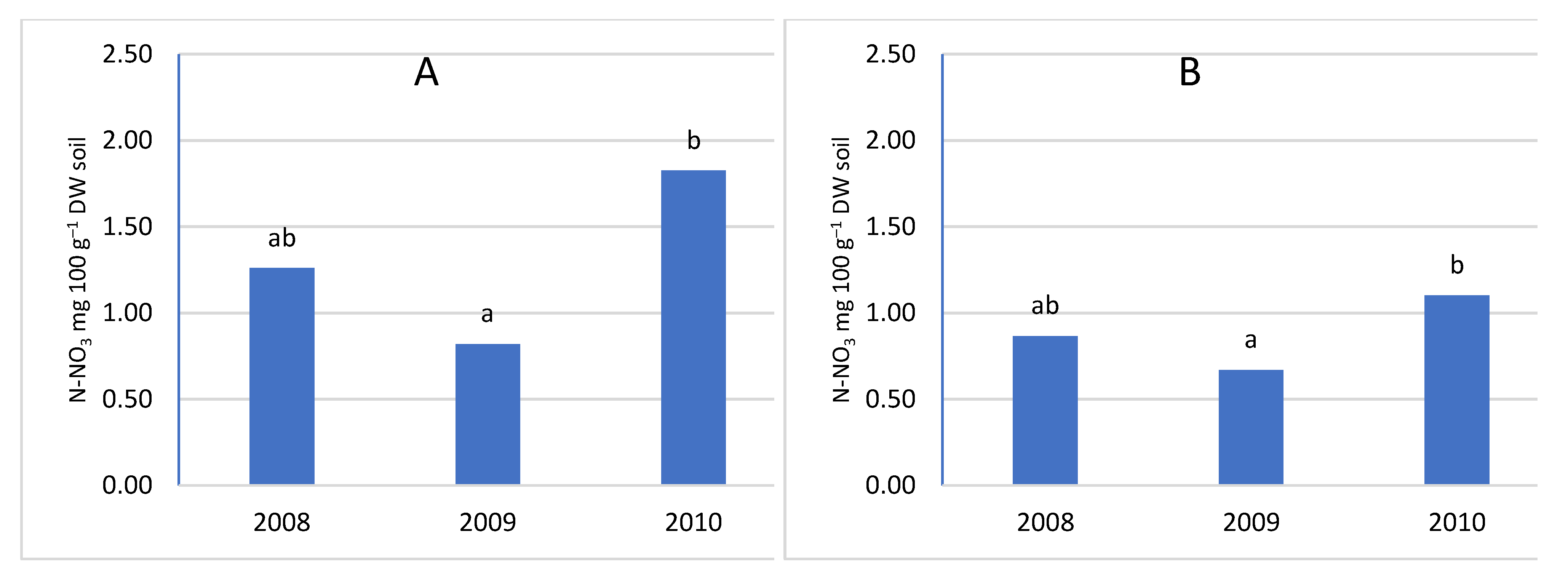

Figure 6.

The content of N-NO3 according to the date of sampling A- in the soil layer 0-20 cm, B- in the soil layer 21-40 cm.

Figure 6.

The content of N-NO3 according to the date of sampling A- in the soil layer 0-20 cm, B- in the soil layer 21-40 cm.

Figure 7.

The content of N-NH4 depending on the term and nitrogen fertilization A- in the soil layer 0-20 cm, B- soil layer 21-40 cm.

Figure 7.

The content of N-NH4 depending on the term and nitrogen fertilization A- in the soil layer 0-20 cm, B- soil layer 21-40 cm.

Figure 8.

The content of N-NO3 depending on the term and nitrogen fertilization A in the soil layer 0-20 cm, B in the soil layer 21-40 cm.

Figure 8.

The content of N-NO3 depending on the term and nitrogen fertilization A in the soil layer 0-20 cm, B in the soil layer 21-40 cm.

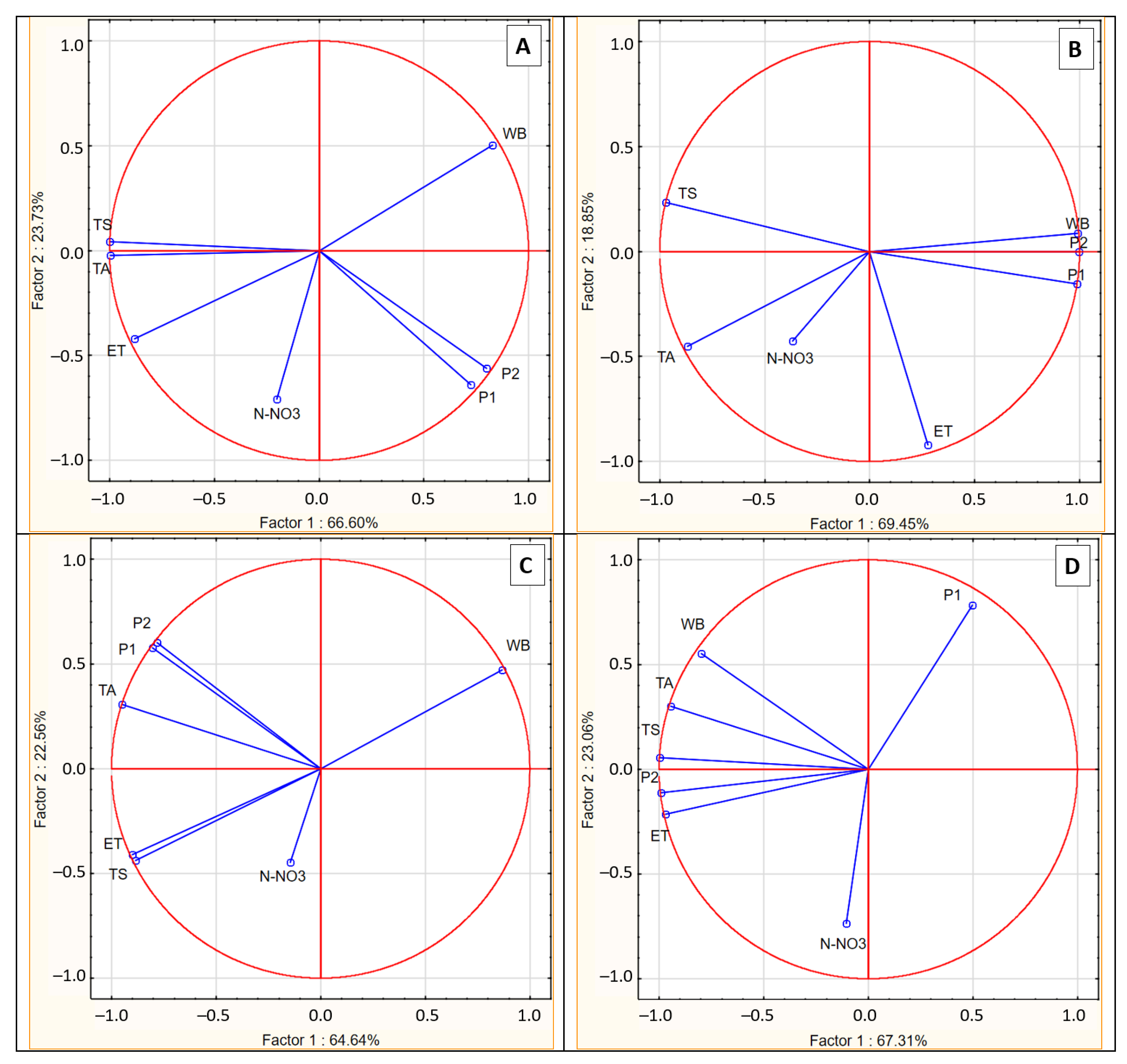

Figure 9.

Influence of climatic conditions on the nitrate nitrogen content in the soil according to the sampling time, as shown by PCA. A- sampling time T1, B- sampling time T2, C- sampling time T3, D – sampling time T4. WB- water balance, P1- sum precipitation 30 days before sampling, P2 sum precipitation 14 days before sampling, TA- average temperature 30 days before sampling, TS- soil temperature. ET- evapotranspiration.

Figure 9.

Influence of climatic conditions on the nitrate nitrogen content in the soil according to the sampling time, as shown by PCA. A- sampling time T1, B- sampling time T2, C- sampling time T3, D – sampling time T4. WB- water balance, P1- sum precipitation 30 days before sampling, P2 sum precipitation 14 days before sampling, TA- average temperature 30 days before sampling, TS- soil temperature. ET- evapotranspiration.

Figure 10.

The content of N-NH4 depending on the year of research A- in the soil layer 0-20 cm, B- in the soil layer 21-40 cm.

Figure 10.

The content of N-NH4 depending on the year of research A- in the soil layer 0-20 cm, B- in the soil layer 21-40 cm.

Figure 11.

The content of N-NO3 according to the year of research A- in the soil layer 0-20 cm, B- in the soil layer 21-40 cm.

Figure 11.

The content of N-NO3 according to the year of research A- in the soil layer 0-20 cm, B- in the soil layer 21-40 cm.

Figure 12.

The content of N-NH4 depending on the orchard A- orchard × soil layer, B- soil layer.

Figure 12.

The content of N-NH4 depending on the orchard A- orchard × soil layer, B- soil layer.

Figure 13.

The content of N-NO3 depending on the A- orchard × soil layer, B- soil layer.

Figure 13.

The content of N-NO3 depending on the A- orchard × soil layer, B- soil layer.

Figure 14.

Effect of nitrogen fertilization on the leaf surface (cm2) and SLW (leaf area per fresh weight) of sour cherries, average for 2012-2013.

Figure 14.

Effect of nitrogen fertilization on the leaf surface (cm2) and SLW (leaf area per fresh weight) of sour cherries, average for 2012-2013.

Figure 15.

The content of pigments in the leaves depends on nitrogen fertilization. A- chlorophyll a, B- chlorophyll b, C- chlorophyll a+b, D– Carotenoids.

Figure 15.

The content of pigments in the leaves depends on nitrogen fertilization. A- chlorophyll a, B- chlorophyll b, C- chlorophyll a+b, D– Carotenoids.

Figure 16.

The content of chlorophyll pigments in the leaves depends on the year of research. A- chlorophyll a, B- chlorophyll b, C- chlorophyll a+b, D- carotenoids.

Figure 16.

The content of chlorophyll pigments in the leaves depends on the year of research. A- chlorophyll a, B- chlorophyll b, C- chlorophyll a+b, D- carotenoids.

Figure 17.

Effect of precipitation in July on the content of chlorophyll pigments. A- chlorophyll a, B- chlorophyll b, C- chlorophyll a+b, D- carotenoids.

Figure 17.

Effect of precipitation in July on the content of chlorophyll pigments. A- chlorophyll a, B- chlorophyll b, C- chlorophyll a+b, D- carotenoids.

Table 1.

Meteorological conditions in 2008-2013.

Table 1.

Meteorological conditions in 2008-2013.

| Month |

Precipitation (mm) |

Temperature (°C) |

| Mean 1982-2007 |

Mean 2008-2013 |

Change from mean 1982-2007 in % |

Mean 1982-2007 |

Mean 2008 -2013 |

Change from mean 1982-2007 |

| January |

30.0 |

38.0 |

+26 |

–0.7 |

–1.6 |

–0.9 |

| February |

27.7 |

16.3 |

–41 |

–0.1 |

–1.0 |

–0.9 |

| March |

34.5 |

29.7 |

–14 |

3.5 |

3.0 |

–0.5 |

| April |

29.0 |

33.2 |

+15 |

9.1 |

10.0 |

0.8 |

| May |

45.9 |

65.6 |

+43 |

14.7 |

14.0 |

–0.7 |

| June |

61.4 |

69.7 |

+14 |

17.2 |

17.3 |

0.1 |

| July |

72.5 |

99.1 |

+37 |

19.5 |

19.5 |

0.0 |

| August |

60.5 |

63.8 |

+5 |

18.9 |

18.8 |

–0.1 |

| September |

41.1 |

47.5 |

+16 |

14.1 |

13.9 |

-0.2 |

| October |

30.7 |

41.1 |

+34 |

9.2 |

8.3 |

–0.9 |

| November |

36.0 |

39.1 |

+9 |

3.5 |

4.7 |

1.3 |

| December |

39.9 |

39.3 |

–2 |

0.5 |

-0.4 |

–0.9 |

| Total |

509.2 |

609.20 |

+14 |

9.1 |

8.9 |

–0.2 |

Table 2.

Influence of climatic conditions on ammonia nitrogen content in soil.

Table 2.

Influence of climatic conditions on ammonia nitrogen content in soil.

| |

T1 |

T2 |

T3 |

T4 |

| |

0-20 cm |

21-40 cm |

0-20 |

21-40 |

0-20 |

21-40 |

0-20 |

21-40 |

| P30 |

0.16 |

0.41* |

–0.51* |

–0.17 |

–0.10 |

0.17 |

–0.41* |

–0.45* |

| P14 |

0.09 |

0.33* |

–0.52* |

–0.27* |

–0.11 |

0.16 |

0.24* |

0.12 |

| Ts |

0.27* |

0.14 |

0.49* |

0.11 |

0.26* |

0.26* |

0.17 |

0.03 |

| EWT |

0.50* |

0.51* |

–0.08 |

0.54* |

0.25* |

0.26* |

0.27* |

0.18 |

| Pds |

–0.38* |

–0.32* |

–0.52* |

–0.25* |

0.18 |

0.27* |

0.10 |

–0.06 |

| WB |

–0.53* |

–0.57* |

–0.52* |

–0.33* |

–0.27* |

–0.26* |

0.07 |

–0.24* |

| Tair

|

0.30* |

0.20 |

0.49* |

0.54* |

0.01 |

0.22 |

0.06 |

–0.10 |

Table 3.

The influence of nitrogen fertilization on the content of P, K, Mg nutrients and on pH in 2010–2013 in depth 0-20 cm.

Table 3.

The influence of nitrogen fertilization on the content of P, K, Mg nutrients and on pH in 2010–2013 in depth 0-20 cm.

| Orchard |

Treatment |

mg 100 g–1 DW soil |

pH in KCl |

| P |

K |

Mg |

K/Mg |

| OR 1 |

N0 |

8.4 |

B1

|

8.5 |

ab |

13.2 |

b |

0.6 |

bc |

6.7 |

b |

| N60 |

9.5 |

c |

7.8 |

a |

11.7 |

a |

0.7 |

c |

6.7 |

b |

| N120 |

9.6 |

c |

9.8 |

cd |

11.9 |

a |

0.8 |

de |

6.5 |

ab |

| OR 2 |

N0 |

7.1 |

a |

7.8 |

a |

11.8 |

a |

0.7 |

c |

6.4 |

ab |

| N60 |

8.3 |

b |

8.3 |

ab |

11.0 |

a |

0.8 |

d |

6.2 |

a |

| N120 |

8.9 |

bc |

10.5 |

d |

10.8 |

a |

1.0 |

f |

6.1 |

a |

| OR 3 |

N0 |

11.5 |

e |

10.0 |

cd |

15.5 |

c |

0.9 |

e |

6.6 |

ab |

| N60 |

9.6 |

c |

9.2 |

bc |

15.8 |

c |

0.5 |

a |

6.4 |

ab |

| N120 |

11.8 |

e |

13.6 |

e |

15.7 |

c |

0.6 |

ab |

6.4 |

ab |

| Mean for orchard |

OR 1 |

9.2 |

b2

|

8.7 |

a |

12.3 |

b |

0.7 |

b |

6.6 |

b |

| OR 2 |

8.1 |

a |

8.9 |

a |

11.2 |

a |

0.8 |

c |

6.2 |

a |

| OR 3 |

11.0 |

c |

10.9 |

b |

15.6 |

c |

0.7 |

a |

6.4 |

ab |

| Mean for treatment |

N0 |

9.0 |

a3

|

8.8 |

a |

13.5 |

b |

0.7 |

b |

6.5 |

a |

| N60 |

9.1 |

a |

8.4 |

a |

12.8 |

a |

0.7 |

a |

6.4 |

a |

| N120 |

10.1 |

b |

11.3 |

b |

12.8 |

a |

0.8 |

c |

6.3 |

a |

Table 4.

The influence of nitrogen fertilization on the content of P, K, Mg nutrients and on pH in 2010–2013 in depth 21-40 cm.

Table 4.

The influence of nitrogen fertilization on the content of P, K, Mg nutrients and on pH in 2010–2013 in depth 21-40 cm.

| Orchard |

Treatment |

mg 100 g–1 DW soil |

pH in KCl |

| P |

K |

Mg |

K/Mg |

| OR 1 |

N0 |

7.4 |

cd1

|

5.9 |

a |

9.2 |

bc |

0.6 |

ab |

6.6 |

bc |

| N60 |

7.3 |

cd |

6.8 |

b |

7.8 |

a |

0.8 |

c-e |

6.7 |

c |

| N120 |

7.6 |

cd |

7.7 |

c |

7.9 |

a |

0.9 |

ef |

6.7 |

c |

| OR 2 |

N0 |

5.3 |

a |

8.7 |

d |

9.8 |

b-d |

0.9 |

ef |

6.0 |

a |

| N60 |

6.4 |

b |

7.7 |

c |

9.0 |

b |

0.9 |

d-f |

6.2 |

ab |

| N120 |

7.2 |

bc |

7.6 |

c |

8.0 |

a |

0.9 |

f |

6.3 |

a-c |

| OR 3 |

N0 |

8.2 |

d |

8.3 |

cd |

11.5 |

e |

0.7 |

bc |

6.2 |

ab |

| N60 |

6.3 |

b |

6.5 |

ab |

10.5 |

d |

0.6 |

a |

6.5 |

bc |

| N120 |

9.3 |

e |

7.6 |

c |

10.2 |

cd |

0.8 |

cd |

6.4 |

a-c |

| Mean for orchard |

OR 1 |

7.4 |

b2

|

6.8 |

a |

8.3 |

a |

0.8 |

b |

6.7 |

b |

| OR 2 |

6.3 |

a |

8.0 |

c |

9.0 |

b |

0.9 |

c |

6.2 |

a |

| OR 3 |

7.9 |

b |

7.5 |

b |

10.7 |

c |

0.7 |

a |

6.4 |

a |

| Mean for treatment |

N0 |

7.0 |

a3

|

7.6 |

b |

10.2 |

b |

0.8 |

a |

6.3 |

a |

| N60 |

6.7 |

a |

7.0 |

a |

9.1 |

a |

0.7 |

a |

6.5 |

a |

| N120 |

8.0 |

b |

7.7 |

b |

8.7 |

a |

0.9 |

b |

6.5 |

a |

Table 5.

Effect of nitrogen fertilization on component content in leaves, depending on tree age (mean values from 2010–2013).

Table 5.

Effect of nitrogen fertilization on component content in leaves, depending on tree age (mean values from 2010–2013).

| Orchard |

Treatment |

Nutrient content (% DW) |

| N |

P |

K |

Ca |

Mg |

| OR 1 |

N0 |

2.14 |

b1

|

0.31 |

e |

1.63 |

d |

2.73 |

f |

0.45 |

ab |

| N60 |

2.36 |

d |

0.18 |

ab |

1.24 |

bc |

2.71 |

f |

0.48 |

bc |

| N120 |

2.65 |

f |

0.17 |

a |

1.43 |

c |

2.39 |

de |

0.43 |

a |

| OR 2 |

N0 |

1.96 |

a |

0.28 |

d |

1.08 |

ab |

2.01 |

a |

0.52 |

de |

| N60 |

2.18 |

bc |

0.22 |

c |

1.06 |

ab |

2.22 |

b-d |

0.55 |

ef |

| N120 |

2.30 |

cd |

0.19 |

ab |

1.02 |

ab |

2.13 |

ab |

0.50 |

cd |

| OR 3 |

N0 |

1.99 |

a |

0.28 |

d |

1.10 |

ab |

2.17 |

a-c |

0.55 |

ef |

| N60 |

2.18 |

bc |

0.20 |

b |

0.89 |

a |

2.44 |

e |

0.58 |

f |

| N120 |

2.51 |

e |

0.17 |

ab |

0.95 |

a |

2.34 |

c-e |

0.52 |

de |

| Mean for orchard |

OR 1 |

2.39 |

b2

|

0.22 |

a |

1.43 |

b |

2.61 |

c |

0.45 |

a |

| OR 2 |

2.14 |

a |

0.23 |

a |

1.06 |

a |

2.12 |

a |

0.52 |

b |

| OR 3 |

2.23 |

a |

0.22 |

a |

0.98 |

a |

2.32 |

b |

0.55 |

c |

| Meant for treatment |

N0 |

2.03 |

a3

|

0.29 |

c |

1.27 |

b |

2.30 |

a |

0.51 |

a |

| N60 |

2.24 |

b |

0.20 |

b |

1.06 |

a |

2.46 |

b |

0.53 |

b |

| N120 |

2.49 |

c |

0.17 |

a |

1.13 |

a |

2.29 |

a |

0.48 |

a |

Table 6.

Influence of climatic conditions and soil mineral content on leaf content.

Table 6.

Influence of climatic conditions and soil mineral content on leaf content.

| |

N |

P |

K |

Ca |

Mg |

| T |

0.01 |

0.09 |

0.52* |

-0.66* |

-0.61* |

| T max. |

-0.06 |

0.12 |

0.55* |

-0.68* |

-0.62* |

| T min. |

0.18 |

-0.17 |

-0.45* |

0.55* |

0.50* |

| Precipitation |

0.01 |

0.08 |

0.52* |

-0.65* |

-0.61* |

| ET |

0.09 |

-0.14 |

-0.54* |

0.67* |

0.62* |

| BW |

0.21* |

-0.18 |

-0.39* |

0.46* |

0.42* |

| N-NO3 (0-20 cm) |

0.53* |

-0.08 |

-0.05 |

-0.07 |

-0.16 |

| Total N (0-20 cm) |

0.53* |

-0.02 |

-0.01 |

-0.09 |

-0.18 |

| N-NO3 (20-40 cm) |

0.58* |

-0.19* |

0.00 |

-0.04 |

-0.20* |

| Total N (20-40 cm) |

0.60* |

-0.20* |

-0.03 |

-0.04 |

-0.19 |

| P (0-20 cm) |

0.31* |

-0.02 |

0.23* |

-0.19 |

-0.06 |

| K (0-20 cm) |

0.40* |

-0.17 |

-0.09 |

0.02 |

0.21* |

| Mg (0-20 cm) |

-0.05 |

0.08 |

0.10 |

0.04 |

0.15 |

| K/Mg (0-20 cm) |

0.28* |

-0.09 |

-0.13 |

-0.09 |

0.09 |

| P (20-40 cm) |

0.43* |

-0.01 |

0.31* |

-0.17 |

-0.37* |

| K (20-40 cm) |

0.24* |

-0.10 |

-0.18 |

-0.02 |

0.15 |

| Mg (20-40 cm) |

-0.22* |

0.21* |

-0.07 |

-0.01 |

0.39* |

| K/Mg (20-40 cm) |

0.38* |

-0.22* |

-0.05 |

-0.02 |

-0.19 |

Table 7.

The influence of nitrogen fertilization on cherry growth in 2007-2013.

Table 7.

The influence of nitrogen fertilization on cherry growth in 2007-2013.

| Orchard |

Treatment |

Leaf area (cm2) |

TCSA |

| 2007 |

2013 |

Increase 2007-2013 |

| OR 1 |

N0 |

29.0 |

a1

|

56.5 |

b |

84.1 |

bc |

27.7 |

ab |

| N60 |

34.1 |

bc |

68.0 |

c |

102.4 |

d |

34.4 |

a-d |

| N120 |

34.7 |

bc |

54.9 |

b |

92.1 |

c |

37.2 |

b-d |

| OR 2 |

N0 |

28.0 |

a |

43.5 |

a |

69.3 |

a |

25.9 |

a |

| N60 |

32.8 |

b |

46.8 |

a |

78.0 |

ab |

31.2 |

a-c |

| N120 |

34.9 |

bc |

46.7 |

a |

88.6 |

c |

41.9 |

d |

| OR 3 |

N0 |

28.7 |

a |

41.5 |

a |

72.2 |

a |

30.8 |

a-c |

| N60 |

32.6 |

b |

43.1 |

a |

78.7 |

ab |

35.6 |

a-d |

| N120 |

36.3 |

c |

39.7 |

a |

77.9 |

ab |

38.2 |

cd |

| Mean for orchard |

OR 1 |

32.6 |

a2

|

59.8 |

c |

92.9 |

b |

33.1 |

a |

| OR 2 |

31.9 |

a |

45.7 |

b |

78.7 |

a |

33.0 |

a |

| OR 3 |

32.5 |

a |

41.4 |

a |

76.3 |

a |

34.9 |

a |

| Mean for treatment |

N0 |

28.6 |

a3

|

47.1 |

a |

75.2 |

a |

28.1 |

a |

| N60 |

33.2 |

b |

52.6 |

b |

86.4 |

b |

33.8 |

b |

| N120 |

35.3 |

c |

47.1 |

a |

86.2 |

b |

39.1 |

c |