1. Introduction

Film therapy, the therapeutic use of movies in psychological therapies, is a growing area of interest to therapists and researchers. Film and television are accessible and creative mediums, seeped in imagery, symbolism and metaphor that can provide rich material for therapeutic dialogue. They can engage diverse client groups and encourage open dialogue around issues. While there is an expanding body of literature on the topic, much of the literature is centred around watching and discussing movies in group therapy. There is a relative sparsity of literature outlining specific models and approaches for working with movies in individual therapy. The model presented here aims to provide a framework for film therapy in both individual and group therapy that could additionally be employed as self-help and to facilitate discussion in counsellor education. I first considered film therapy when my counselling clients began to talk spontaneously about movies and television shows, noticing that working with these themes helped to further the therapeutic process. The MOVIE model presented in this paper initially began in practice as I adapted counselling methods to work with discussion of movies and television in my counselling and teaching practice. The finished model presented here is informed by a practice focused review of relevant literature. Electronic databases were used to search for peer reviewed journal articles that piloted or discussed film therapy interventions in psychological therapy. Books written by therapists or academics in the field were additionally included, along with articles in industry publications such as Therapy Today and Psychology Today to capture developing models and practice in this emergent area. The literature review identified findings on the benefits of working with movies, the therapeutic techniques used, ethical considerations and possible limitations of film therapy that therapists may need to consider. The model articulates a method of working with film imagery and themes in psychological therapy that can be adapted to work in different modalities and applied in a variety of settings.

2. What is Film Therapy?

Film or cinema therapy describes a process where movie watching is employed as a therapeutic intervention. Film therapy sits within a long therapeutic tradition of use of imagery, symbol, metaphor, and story to discuss client’s experience (Strong & Lotter, 2015). Movies offer living stories, metaphors that can be seen, heard and experienced, that viewers may become completely absorbed in during watching. Adept at evoking emotions in viewers, movies can facilitate catharsis, a process first identified by Aristotle, who noted that audiences released emotion while watching Greek tragedies (Aristotle, Applebaum & Butcher, 1997), and emotional processing (Hamilton, 2020), engaging the viewer via, image, music, and drama, often at both a cognitive and more visceral level. Talking about issues and feelings in the context of a movie, affords a degree of distance and separation that allows clients to discuss issues more safely, feeling less overwhelmed, offering different perspectives on experiences or feelings (Tannous, Haddad & Shechtman, 2019). They may recognise themselves in characters or situations, have a sense of shared humanity, feel less alone with issues, and experience de-stigmatisation of their difficulties (Hamilton, 2013). This can make movie watching a powerful route into therapeutic and emotional exploration. Therapists may show a movie to facilitate therapeutic discussion or may suggest that a client watches a particular movie between sessions, for subsequent discussion. Conversely, watching a movie of the client’s choice could afford greater insight into their world view and life experience. In counselling practice, discussion of films and television may occur organically. My definition of film therapy would include spontaneous and unplanned therapeutic discussion of films and television and so can be integrated easily across modalities and settings as prescribed movie watching can be included but is not required. Movies watching can be a therapeutic activity (Clyman, 2013) that could be used for self-help. We may define film therapy here then, as watching or discussing movies or television shows, as part of a therapeutic process.

3. Therapeutic Elements of Movie Watching

Engaging with film can take the audience on an emotional journey which can be therapeutic (Clyman, 2013, Soloman, 2001, Izod and Dovalis, 2015). For example, in movies such as A Monster Calls (Bayona, 2016) and The Shallows (Collet-Serra, 2016) young protagonists’ metaphorical encounters with monsters represent their struggle to face and integrate difficult feelings associated with facing cancer, grief, and terminal illness (Hamilton, 2020). Audiences may accompany them in this emotional journey, where they too may confront and process grief feelings and existential angst, to face and survive their worst fears in a safer way (Hamilton, 2020).

The ‘once removed’ quality of engaging with fictional characters may enable us to connect with and release feelings in a way that feels safer and less intense (Scheff, 2001). Tannous, Haddad & Shechtman (2019, p. 307) note that films enable clients to ‘consider a narrative’ that resembles their ‘own personal story, yet with a metaphorical distance that makes it less intimidating.’ We may cry at a movie and believe that we are crying for characters we identify with, not ourselves, but may be releasing our own unprocessed feelings, projecting emotions onto the characters. These feelings may arise because the movie themes relate directly or metaphorically to our own experience. However, we can feel strong emotions even in response to themes that appear unrelated to our life experience, through experiencing empathy with the movie characters, or at times when strong emotions are present for us but not expressed in other ways. Seeing some form of metaphorical representation of this emotional process on screen, may allow release of related emotions.

Clyman (2013) identifies key therapeutic outcomes of movie watching. Emotionally, movies may improve our mood or provide insight into relationship issues. Cognitively our attention is fully engaged and working out the motives of the characters. Finally, movie-watching with friends or family can be a social activity that helps to develop interpersonal skills, and viewers may learn consequences of behaviour through watching those experienced by the movie characters. Given the therapeutic benefits I suggest that movies may offer a source of self-care. Watching movies and television can offer a time out from life physically through the pause and rest required to sit and watch, and psychologically through the experience of engaging with different worlds or settings and new perspectives, alongside a chance to reflect on and process emotions. Films may additionally prompt discussion of difficult emotions and issues among friend and family groups and in wider culture. Audiences of reality television shows depicting therapeutic interventions may feel like they have shared in the therapeutic journey of the television client and see their issues de-stigmatised through watching sympathetic and supportive responses on-screen (Hamilton, 2013), while related social media chat may be empathic and encourage a sharing of stories (McMurria, 2005). Similarly, for trauma survivors, watching and discussing movies that reflect their experience may offer less intensity than engaging directly with their real-world overwhelming experience (Hamilton & Sullivan, 2015).

Movies may help us to learn life skills in watching others deal with life issues and events. Research during the Covid 19 pandemic has found that fans of apocalyptic horror, such as zombie movies, exhibited ‘greater resilience and preparedness’ supporting the idea that such movies can teach coping skills for real-life survival (Scrivner, et al. 2020). Similarly, Duncan, Beck and Granum (1986) found that a topic specific film therapy group helped adolescents in residential treatment to prepare for return to family and community life. Movie watching can be a therapeutic experience, more easily accessible within our everyday life. Dermer and Hutchings (2000) note that the usefulness of movie therapy perhaps ultimately lies in working with a popular medium that clients already know.

4. Working Therapeutically with Movie-Watching

There is a growing body of research on the benefits of film therapy. Tannous Haddad & Shechtman (2019) note that movie therapy proved beneficial in reducing parent-adolescent conflict in school-based counselling compared to a control group, finding benefits of catharsis, increased empathy, distance allowing more ease of discussion of issues and interpersonal learning. Dumtrache (2014) found there was a significant reduction in anxiety in participants of a cinema therapy group compared to a control group and use of cinema-therapy made participation in therapy more appealing, leading to increased personal and interpersonal development. Carroll and Sher (2018) found that a film therapy group helped young people diagnosed with autistic spectrum condition to identify positive strengths and build resilience, while participants reported working with the medium of film enjoyable. Reflecting on and discussing movies in cognitive behavioural counselling-based film therapy helped to improve communication skills in females with low sexual desire (Alizadeh et al, 2019). Talking about movie characters helped psychiatric patients to express their thoughts, feelings, and beliefs in group therapy (Yazici et al, 2014). Discussion of film and comic book superheroes enabled a peer support group of people diagnosed with schizophrenia to develop new stories about their experience. Participants identified with the way superheroes powers are often rooted in the things that make them ‘different’ or in a traumatic event or accident that transforms them (Tolfree, 2016, p.28). These movies helped the group to re-conceptualise their stories and envisage new possibilities for the future.

Much of the research on working with film in therapy is centred around working with groups, yet as discussion of films and television emerged organically in individual therapy, I began to develop and integrate methods for working individually in this area. With attention to working with clients individually, Hamilton and Sullivan (2015) integrate techniques from person centred, gestalt, experiential and narrative therapies to discuss science fiction and horror movies with trauma survivors who introduce these themes, while managing physiological trauma responses. The MOVIE model develops a framework for discussing movies that is not genre-specific but can incorporate attention to trauma-informed considerations.

5. Using Film in Counsellor Education

I have used film extensively in my work with students as a lecturer in counsellor eduction. Blumer (2010) discussed several benefits in using film with therapy students, that it holds attention, evokes emotion about real life issues but without the accompanying responsibility, it makes a more lasting impression and can be done in the students own time. In my experience, using film increases student engagement, as an accessible and enjoyable medium. The safe distance afforded by centring discussion on movie characters watching movies enables students to engage with and discuss issues difficult issues such as grief and diversity. Learning is emotional as well as intellectual, through experiencing empathy for characters, and bringing issues and theories to life.

6. The MOVIE Model for Working with Film Imagery and Themes in Psychological Therapy

The MOVIE model presented here aims to support watching or discussing movies as part of a therapeutic process. It is applicable to all movie genres and client groups. While the model integrates elements of mindfulness, experiential therapy and narrative therapy, the intention is that it can be applied across modalities, as it is centred around a series of steps that can be adapted to different counselling approaches. It can be utilised as a trauma–informed model that gives attention to safety and grounding techniques to create a safe foundation for movie watching or for therapeutic dialogue to explore the experience of watching and discuss movie themes. The model can additionally be applied in counsellor education, allowing counselling students to engage with issues taught on a visceral, empathetic, and intellectual level, adding an extra dimension to the learning that students may find accessible (Mangot and Murthy, 2017). Finally, the model could provide steps for therapeutic movie watching as self-help.

7. Ethical Considerations and Safety

It is recommended that consideration is given to ethical issues and safety when applying this model. The model can be applied either to talk about themes from film and television that arise spontaneously, or to support the method of watching and discussing prescribed films in individual or group therapy. Informed consent will be important (Schulenberg, 2003) if therapists suggest films to clients meaning that therapists should consider and discuss with the client or group if the themes, content, and the genre of the movie is appropriate for them and would contribute to their therapeutic process. It is recommended that similar consideration be applied if therapists watch movies suggested by clients and that movies should comply with relevant legal requirements. Schulenberg (2003) recommends that therapists consider why they would recommend this movie to this client, what they hope it would achieve, how they will facilitate a subsequent debrief with the client and ways to address any negative experiences of watching. It will be important to consider if a movie could initiate affective trauma responses or difficult emotions in a way that is detrimental to the client. These considerations are included early in the MOVIE model with attention given to deciding if watching would be helpful and monitoring experience throughout, equipped with techniques for grounding and emotional self-care. Additionally, debrief is built into the model, which provides a method for discussing films after watching. The model includes teaching trauma-informed techniques for grounding if appropriate and wider attention to emotional self-care while watching and discussing movies. It is intended that the model be applied with clients who are supported by a suitably skilled clinician.

For counselling clients, talking about their experience of engaging with a movie, can provide a tangible focus for therapeutic dialogue and create a safe distance to begin exploration of their own emotional world. While intended primarily for counselling clients, this model could also be used as a self-help practice providing that the viewer is able to assess the potential impact of viewing on their wellbeing and has skills to self sooth and ground themselves if they find the material distressing. It may be useful if the viewer has supportive relationships in place, or knows how to seek help, if they need to discuss any emotions that may emerge.

8. Mindful Engagement

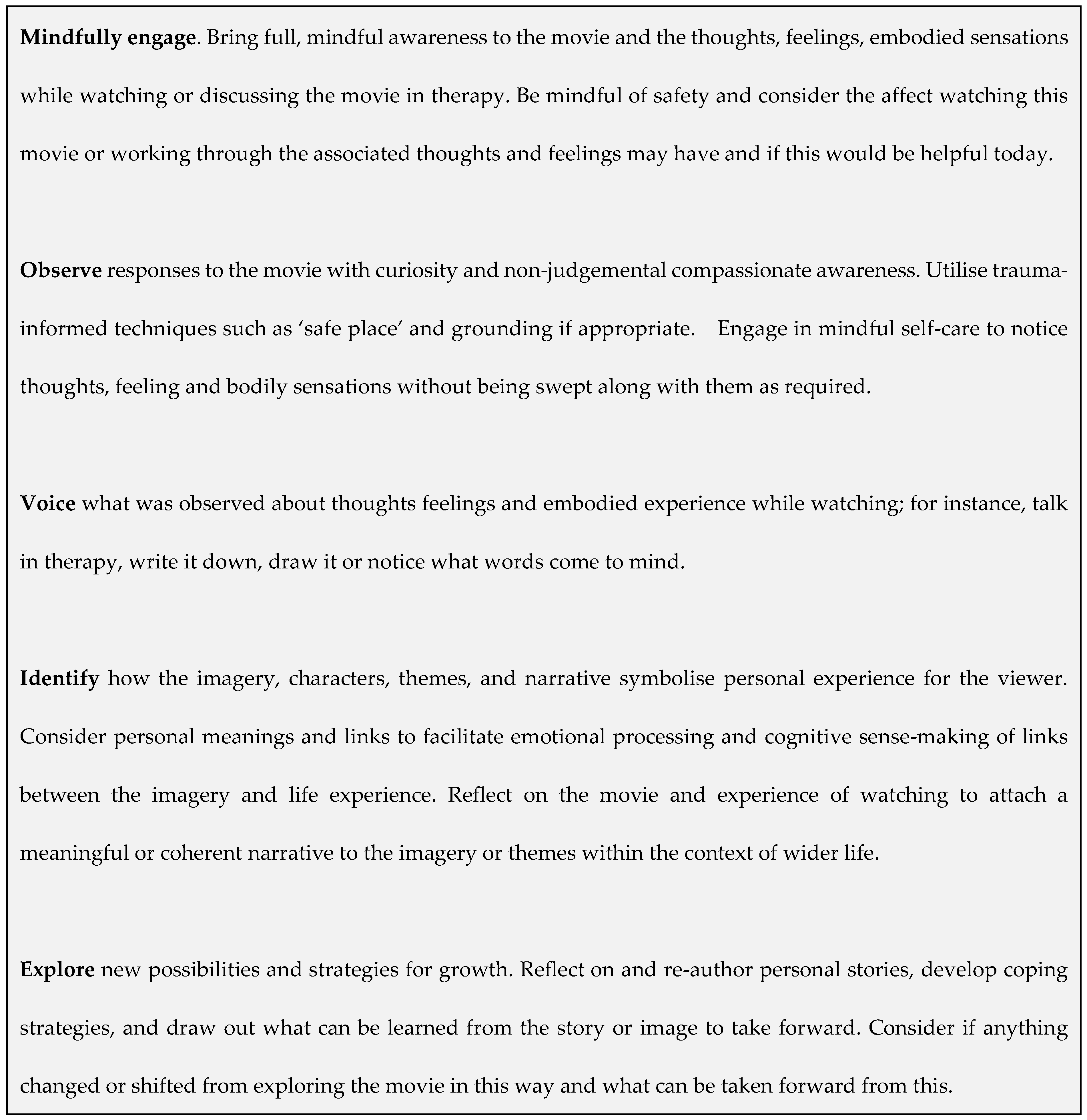

The MOVIE model presented in

Figure 1 begins with mindful engagement with the movie, noting Clyman’s (2013) suggested awareness of thoughts and feelings while viewing, and expanding awareness to include noticing bodily sensations that may be associated with emotional affect states (Gendlin, 2003). The model extends this to include awareness of the clients’ process during therapeutic discussion of the movie as well as their experience of watching. Nicols and Schwartz (1998) note that the therapist needs to ensure clients do not engage emotionally without reflection or engage on a purely intellectual level. The MOVIE model includes mindful and therapeutic techniques to facilitate self-aware emotional engagement and reflection on the movie, the experience of watching and the ways that the movie may be meaningful in the client’s wider life and relationships.

Mindful engagement begins with taking stock of thoughts and feelings before watching to decide if today is the best time to watch this movie or to work through the associated thoughts or feelings in therapy. The client and therapist will need to consider if these activities will facilitate therapeutic processing and exploration, even if it may be difficult and stimulate strong emotions, or if it could potentially feel too overwhelming. If suggesting a movie for the client to watch independently for discussion in the following session, the therapist could support the client in learning mindful or experiential techniques to complete a self ‘check-in’ on thoughts, feelings, and somatic experience (bodily sensations) in the moment to assess their wellbeing and resilience and make decisions about watching that support their own self-care. Taking an itinerary, the client may notice for instance that they feel tension in their shoulders, they feel very anxious, their thoughts are racing, they feel very agitated and are finding it difficult to focus. Knowing themselves and what tends to work in response to feeling this way, they can decide if watching this movie right now would be helpful or if other activities may help more. It may be that movie-watching could help to focus, distract from racing thoughts, process feelings, and take some time out. Perhaps they may benefit from other self-care techniques first, to ground themselves for movie watching. Alternatively, it may prove more helpful to watch the movie on another day, when they may feel better able to focus and process the feelings watching this movie may bring to the fore.

9. Observing responses

The next stage is to observe responses to the movie with curiosity and without judgement. While completing a mindful self-check-in at the first stage would help to reduce the likelihood of feeling overwhelmed while watching, clients can remain mindfully aware of their response during the process of watching. Techniques from trauma-informed practice can help clients learn to manage hyperarousal and any difficult visceral emotional responses associated with trauma, grief, stress, anxiety, and panic that arise in response to movie-watching or while discussing the movie in therapy. Use of trauma informed techniques can de-escalate the bodies stress response, by engaging the parasympathetic nervous system associated with ‘rest and digest’ functions (Rothschild, 2003). Examples include imagining a ‘safe place’, grounding in the here and now through noticing aspects of present experience or surroundings and breathing techniques (Rothschild, 2003).

More generally, non-trauma specific, mindful self-care techniques can be employed usefully at this stage of the model, to notice thoughts, feelings, and body sensations without being swept along with them (Kabat-Zinn, 2013). In addition to techniques for exploring the clients embodied sense of their emotions before viewing, focusing (Gendlin, 2003) could be used to work through emotions and body sensations that emerge while viewing. In this technique one tunes in to a bodily sensation and notices if an associated word or an image emerges that most closely matches the feeling itself. In noticing and staying with the feeling, one may experience a sense of resolution, shift or a change in the feeling and associated emotions through allowing it fully into awareness (Gendlin, 2003). In a solution focused addition to this process, work around creating the desired change to the feeling is added. For instance, if the feeling has a sense of a dark cloud, we may imagine it changing to a white wispy cloud in a blue sky and notice that as we change the image the accompanying feeling changes. Using mindful self-compassion practices, we may consider what the feeling needs, for example, if the feeling needs warmth or nurturing, we may imagine receiving those things or offering them to ourselves (Brach, 2019). These techniques, or other methods that achieve similar results, can be used as emotional self-care for clients working with a therapist or watching movies independently.

10. Voicing Experience

Voicing what was experienced while watching the movie can begin the therapeutic process of articulating and exploring thoughts and feelings. This could include creative therapy techniques for tuning into and expressing feelings through drawing or other creative activities, journaling or just working through and naming feelings in the moment of experiencing them. Voicing, naming, acknowledging, and exploring feelings is a key element of processing our experience of self and world. Rogers (1951) argued that the need to process or become fully aware of our emotional experiencing is part of a self-actualising drive to grow and develop. Rogers noted that inhibited processing is a source of psychological distress that creates incongruence between self-perception and real experience. Processing experience safely can play a key role in recovery from posttraumatic stress in trauma-informed work (Joseph, 2017,). Focusing could also be utilised here to tune into, explore and give voice to an embodied sense of an emotion. However, methods of staying with and exploring the clients emotional experiencing from any modality could be applied.

11. Identifying personal relevance

At this stage of the model, the therapist would use counselling skills within a therapeutic relationship to facilitate emotional processing and cognitive sense-making of links between the imagery and life experience, allowing the client to attach a meaningful or coherent narrative to the imagery or themes within the context of their wider life. Narrative therapy (White and Epston, 1990) presupposes that we make meaning of our lives and our identity through socially constructed narratives or self-stories, formed by our perceptions of self and others, our experience and interactions, and the stories about ourselves we have internalised from wider culture and socialisation. Cultural narratives include those around race, gender, sexuality, social class, or disability, for instance, that inform our sense of self and the way we perceive ourselves. There may be prevalent narratives around mental health and mental illness affecting the way we see ourselves when experiencing psychological distress. In narrative therapy clients reclaim ‘subjugated’ stories (Turns and Macey, 2015, p.592) from prevalent narratives they may have internalised. Dumtrache (2014, p.127) noted that participants in a cinematherapy group ‘restructured and transformed their own life scripts’ through identification with movie characters and themes. To facilitate this exploration, we may ask the client to reflect on their relationship with movie themes and characters. It is recommended that therapists use counselling skills to expand on client responses. The following example questions are adapted from Hamilton and Sullivan’s (2015) model and further developed here to support this stage of exploration in the MOVIE model. Therapists could adapt them as relevant to their client:

What was it that drew you to this film?

How did you feel when while watching? How did it leave you feeling?

What was important to you about the movie?

What were the key themes and issues that you feel the film conveyed?

Which character(s) did you identify with?

What was it about the character(s) and their story that most resonated with you?

Were there any messages or themes relevant to your situation or life? If so, how did the film enable you to connect with them?

How did the characters relate to each other and what does this mean to you?

Who did the characters remind you of in your life?

How did the characters approach the situation/ overcome their difficulties? Would you do it this way or differently?

How do you view the characters? How does this fit in with your beliefs about yourself, other people, and the wider world?

How do you feel about the way the characters or issues were portrayed? How does this match up to or contrast with your own experience of similar characters or issues?

Were there any messages or themes that you would take away about your own life?

12. Exploring New Possibilities

The MOVIE model ends with exploration of new possibilities and strategies for growth. Here we may facilitate re-authoring of personal stories, look at helping the client to develop coping strategies, and draw out what can be learned from the story or image to take forward. Turns and Macey (2015) note that new possibilities emerge for clients when watching movie characters solve familiar problems in ways not previously considered. To facilitate this, we may ask the client to notice if anything changed or shifted from exploring the movie in this way and what they could take forward from this. The client could consider if they would write a different ending and what that may look like, or if there is any learning from considering the movie they would apply to their own life, relationships, or situation. It may be helpful to consider if any beliefs, feelings, or perspectives were changed or perhaps affirmed. Thinking about how the movie story fits in with their personal story, they may consider if they would change their story or tell it differently based on the experience of watching the movie and working through the themes therapeutically. The client could plan how they could use movies therapeutically and how they could utilise the wider mindfulness, grounding and emotional self-care techniques learned to support their wellbeing.

13. Practice Considerations

Schulenberg (2003) notes that while movies can aid work with some clients who may not respond to other methods, not all clients enjoy movies. The MOVIE module would tend to be employed with those who already watch movies or television and may opt for this method as they find movies helpful or simply wish to discuss something they have already watched, utilising an activity that clients already engage with.

Turns and Macey (2015) found that attention span can be a limitation in work with children and some families may not have the technology or resources to access movies. They noted that views, perspectives, and interpretations of other family members watching with the client, can create an unanticipated mitigating influence. However, movies are a very accessible medium for most and therapists would need to explore and consider what methods would best suit the client’s resources and environment. Therapists can adapt the method to include shorter television shows instead of movies, for instance, and could discuss the impact of the setting in which the client will watch and who they plan to watch with.

Mainstream movies may feature stereotyped representations of gender, race, disability, sexuality and other diverse groups and populations. Additionally, movies can present inaccurate or stereotyped representations of mental health but can also educate the public with more accurate representations that can provide insight or prove educational (Mangot and Murthy, 2017, Hamilton, 2013). It may be difficult for clients to find characters they can identify with or find realistic depictions of the mental health issues they may be facing. Therapists could ensure they develop the awareness and skills, to discuss depictions of culture and mental health issues presented in movies. Dunham and Dermer (2020, p.1472) found cinematherapy helpful if used in ‘culture-informed’ interventions and cinema can be useful as a medium known to clients across cultures (Niemiec and Wedding, 2014) that can ‘transcend all barriers and differences’ (Strong and Lotter, 2015, p1).

Clients may not enjoy or respond to mindfulness techniques, necessitating application of other methods as appropriate. However, mindfulness is employed here as a mindset for noticing thoughts and feelings, rather than the associated breathing activities or formal meditation practices that some clients find off-putting or challenging. The therapist may need skill in trauma-informed practice, if working this way is relevant to the client, but no more so than working within any trauma-informed approach. However, these methods may not be required with each client. Therapists can adapt the model to the client’s issues and draw on techniques from their own modalities for exploration of emotions and client experience, making the model compatible with a range of therapeutic approaches. Finally, the model is yet to be tested empirically with a wider population, but is informed by current research and counselling practice, drawing on established techniques, applied here to working therapeutically with the medium of film and television.

14. Conclusions

Movies are a widely accessible part of everyday life for clients and therapists of different social, cultural, and economic backgrounds and age groups (Strong and Lotter, 2015). They provide rich material for therapeutic dialogue drawing on a medium in which most clients are literate and have experience. Turns and Macey (2015) found that use of movies increases children’s engagement with therapy who may respond to visual methods metaphor and story. Use of films could similarly increase engagement with therapy and education and increase ease of dialogue, suggesting this is a highly accessible and relatable method for many people that may transcend age, gender, culture, class, and other differences. The MOVIE model offers a widely applicable, trauma- informed model for working with film and television in psychological therapy, counsellor education and self-help. Following the model clients mindfully observe and voice their emotional and psychological responses to movie watching, identify how the imagery, characters, themes, and narrative symbolise personal experience and consider any new possibilities that emerged. Consideration is given to safe practice surrounding informed consent, debriefing, legal and ethical issues and deciding if watching the movie would best support the client’s well-being. The model has the flexibility to work in group or individual therapy that can include planned movie watching or can be applied to spontaneous discussion of movies or television shows already watched. It offers a framework that can be applied across different counselling modalities and settings with a wide variety of clients or can be utilised as self-help. This framework grew from my experience in counselling practice as clients introduced themes, metaphors and stories from film and television and I developed methods to facilitate this dialogue and exploration. The model is informed by a practice focused review of relevant literature and contributes to a growing body of research and practice in film therapy. Clients are already engaging culturally, socially, psychologically, and emotionally with this medium and therapists need to develop methods for incorporating dialogue around film, television, media, and other communication technologies within counselling practice. The MOVIE model could provide a starting point for this dialogue to aid therapists in working in a safe and trauma-informed framework, in this developing area of practice.

Data Availability Statement

Data sharing is not applicable to this article as no new data were created or analysed in this study.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Alizadeh, M., Akbari Turkestani, N., Oohadi, B., & Mehrabi Rezveh, F. (2019). Effectiveness of cognitive behavioral counselling-based film therapy on the communication skills of females with low sexual Desire. Journal of Nursing and Midwifery Sciences, 6(1), 8-14. https://www.jnmsjournal.org/text.asp?2019/6/1/8/255329.

- Aristotle, Applebaum, S., & Butcher, S. H. (1997) Poetics. Dover Publications.

- Bayona, J.A. (Director) (2016) A Monster Calls [Film]. Focus Features.

- Blumer, M.L.C. (2010) And Action! Teaching and Learning Through Film, Journal of Feminist Family Therapy, 22(3), 225-235. [CrossRef]

- Brach, T. (2019) Radical Compassion: Learning to Love Yourself and Your World with the Practice of R.A.I.N. Rider.

- Caroll, B. and Sher, M. (2018) Using cinema therapy to highlight and build character strengths and values in young people within a neurodevelopmental service: a pilot study. GAP. 19(1), 14-21. [CrossRef]

- Clyman, J. (2013) A Model for Therapeutic Move Watching. Psychology Today, May 3. https://www.psychologytoday.com/gb/blog/reel-therapy/201305/model-therapeutic-movie-watching.

- Collet-Serra, J. (Director) (2016) The Shallows [Film]. Columbia Pictures.

- Dermer, S.B., and Hutchings, J.B. (2000) Utilizing Movies in Family Therapy: Applications for Individuals, Couples, and Families, The American Journal of Family Therapy, 28(2),163-180. [CrossRef]

- Duncan, K., Beck, D.L., & Granum, R.A. (1986). Ordinary People: Using a Popular Film in Group Therapy. Journal of Counseling and Development, 65(1), 50-51. [CrossRef]

- Dumtrache, S. D. (2014). The effects of a cinema-therapy group on diminishing anxiety in young people. Procedia-Social and Behavioral Sciences, 127, 717-721. [CrossRef]

- Dunham, S. M., & Dermer, S. B. (2020). Cinematherapy with African American couples. Journal of clinical psychology, 76(8), 1472–1482. [CrossRef]

- Gendlin, E (2003) Focusing: How to gain direct access to your body’s knowledge. Rider.

- Hamilton, J. (2013) Reality TV as Therapy. Therapy Today, 24.(5), 14-17. https://www.bacp.co.uk/bacp-journals/therapy-today/2013/june-2013/reality-tv-as-therapy/.

- Hamilton, J. & Sullivan, J. (2015) Horror in Therapy: Working Creatively with Horror and Science-Fiction Films in Trauma Therapy. Createspace.

- Hamilton, J. (2020). Monsters and posttraumatic stress: an experiential-processing model of monster imagery in psychological therapy, film, and television. Humanities and Social Sciences Communications, 7(1). [CrossRef]

- Izod, J., & Dovalis, J. (2015). Cinema as Therapy: Grief and transformational film (1st ed.). Routledge. [CrossRef]

- Joseph, S. (2017). Understanding post-traumatic stress from the person-centred perspective. In Joseph, S. (Ed.), The handbook of person-centred therapy and mental health (pp. 233–224). PCCS Books.

- Kabat-Zinn, J. (2013) Full Catastrophe Living: Using the Wisdom of Your Body and Mind to Face Stress, Pain and Illness. Bantam Books.

- Mangot, A.G. and Murthy, V.S. (2017) Cinema: A Multimodal and Integrative Medium for education and Therapy. Annals of Indian Psychiatry, 1(1), 51-53.https://www.anip.co.in/text.asp?2017/1/1/51/208334.

- McMurria, J. (2005) Desperate citizens. Flow. 3. http://www.flowjournal.org/2005/10/desperate-citizens/.

- Nichols, M.P., and Schwartz, R.C. (1998) Family Therapy: Concepts and Methods. Boston: Allyn and Bacon.

- Niemiec, R.M., & Wedding, D. (2014). Positive psychology at the movies: using films to build character strengths and well-being. Hogrefe Publishing.

- Rogers, C. (1951) Client-Centred therapy: it’s current practice, implications and theory. Constable.

- Rothschild, B. (2013) The Body Remembers Casebook: Unifying Methods in the Treatment of Trauma and PTSD. Norton.

- Scrivner, C., Johnson, J. A., Kjeldgaard-Christiansen, J., & Clasen, M. (2021). Pandemic practice: Horror fans and morbidly curious individuals are more psychologically resilient during the COVID-19 pandemic. Personality and individual differences, 168(110397). [CrossRef]

- Schulenberg, S,E, (2003) Psychotherapy and Movies: On Using Films in Clinical Practice. Journal of contemporary psychotherapy, 33 (1), 35-48. https://link.springer.com/article/10.1023/A:1021403726961.

- Soloman, G. (2001) Reel Therapy: How Movies Inspire You to Overcome Life’s Problems. Aslan Publishing.

- Strong, P., & Lotter, G. (2015). Reel help for real life: film therapy and beyond. Hts Theological Studies, 71(3). [CrossRef]

- Tannous Haddad, L., & Shechtman, Z. (2019). Movies as a therapeutic technique in school-based counseling groups to reduce parent-adolescent conflict. Journal of Counseling & Development, 97(3), 306–316. [CrossRef]

- Tolfree, R. (2016). We could be heroes: how film and comic book heroes helped a peer support group to reconnect with their gifts. International Journal of Narrative Therapy & Community Work, 4(4), 26–31. https://search.informit.org/doi/10.3316/informit.529826981952514.

- Turns, B. and Macey, P. (2015) Cinema Narrative therapy: Utilising family films to externalize children’s problems. Journal of family therapy, 37, 590-606. https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-6427.12098. [CrossRef]

- White, M. and Epston, D. (1990) Narrative Means to Therapeutic Ends. W. W. Norton.

- Yazici, E., Ulus, F., Selvitop, R., Yazici, A. B., & Aydin, N. (2014). Use of movies for group therapy of psychiatric inpatients: theory and practice. International journal of group psychotherapy, 64(2), 254–270. https://doi.org/10.1521/ijgp.2014.64.2.254. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).