Submitted:

23 December 2022

Posted:

05 January 2023

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

- Main Conclusion of the study

- Recommendation of key threshold discretization and computational speed to duplicate the results of the original prequel [3].

- Validation of the first sequel's [14] identification of paramountcy of discretization and computational speed.

- Validation of the second sequel's [13] identification of deterministic artificial intelligence performance and recommended selection of algorithms.

2. Materials and Methods

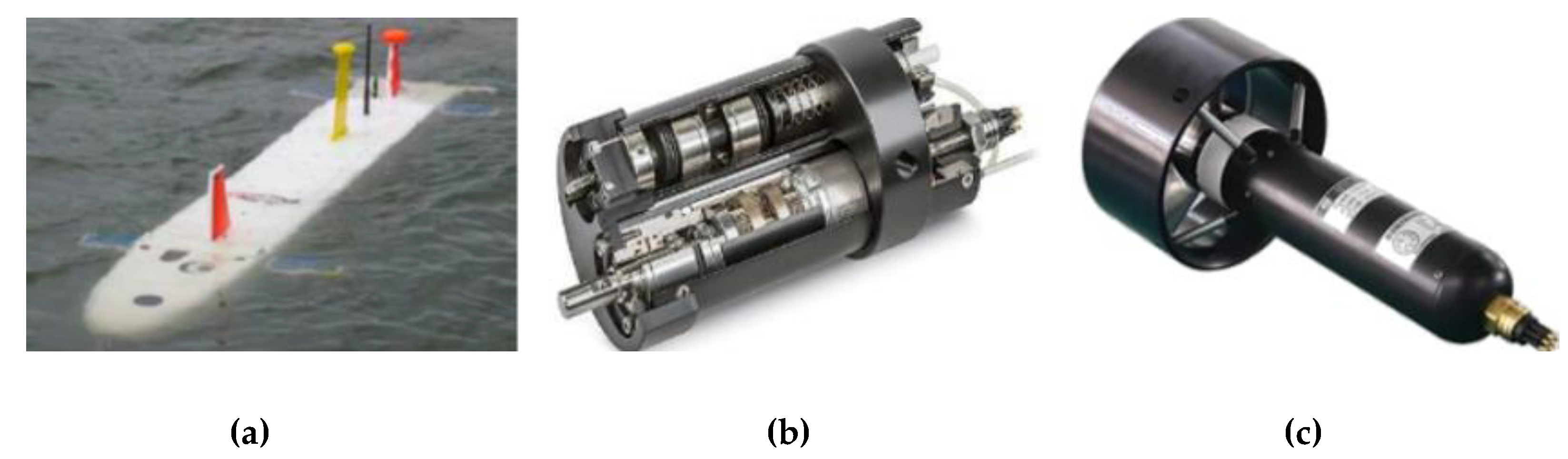

2.1. Truth Model for Motor Dynamics

2.2. Model-Following Self Tuner

2.3. Deterministic Artificial Intelligence

3. Results

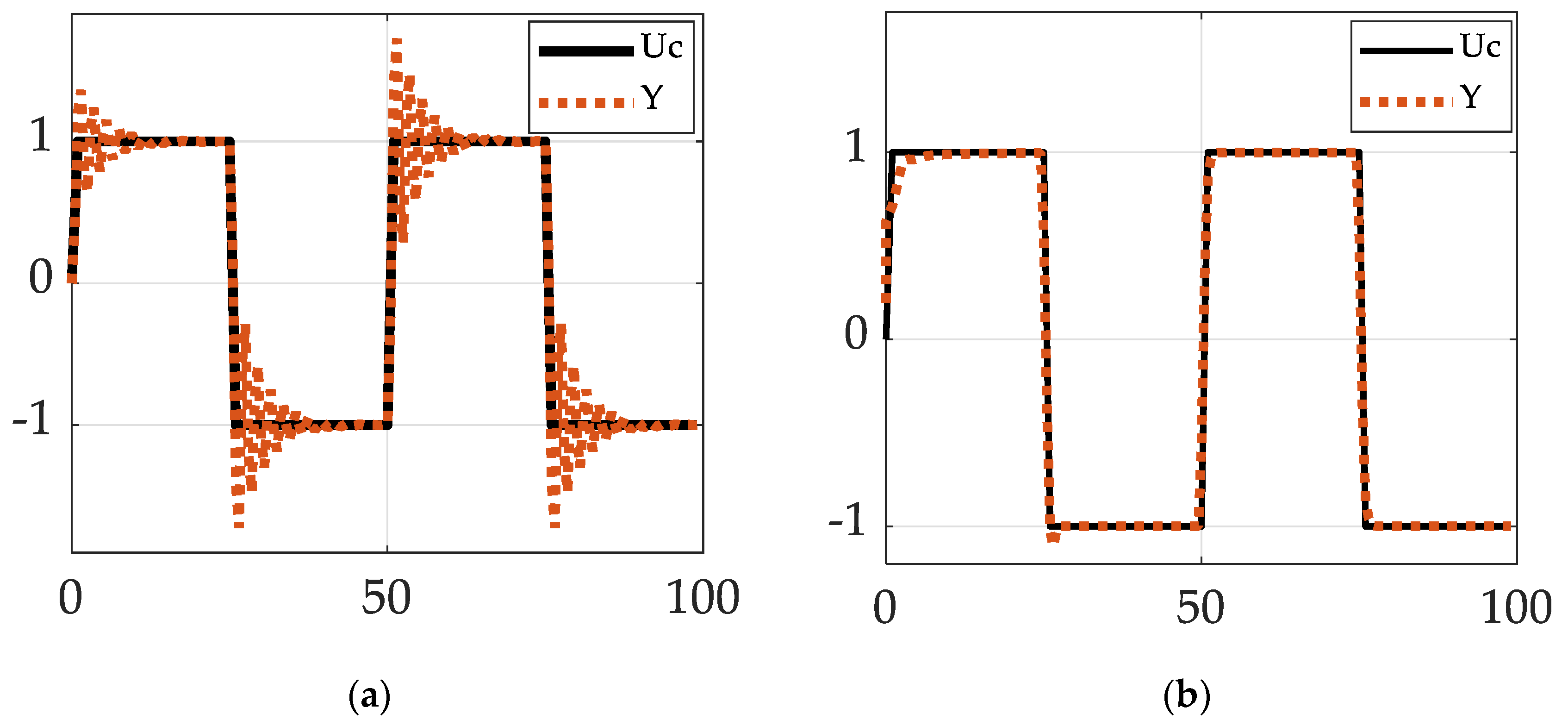

3.1. Model-following Self-tuner Control v.s. Deterministic Artificial Intelligence

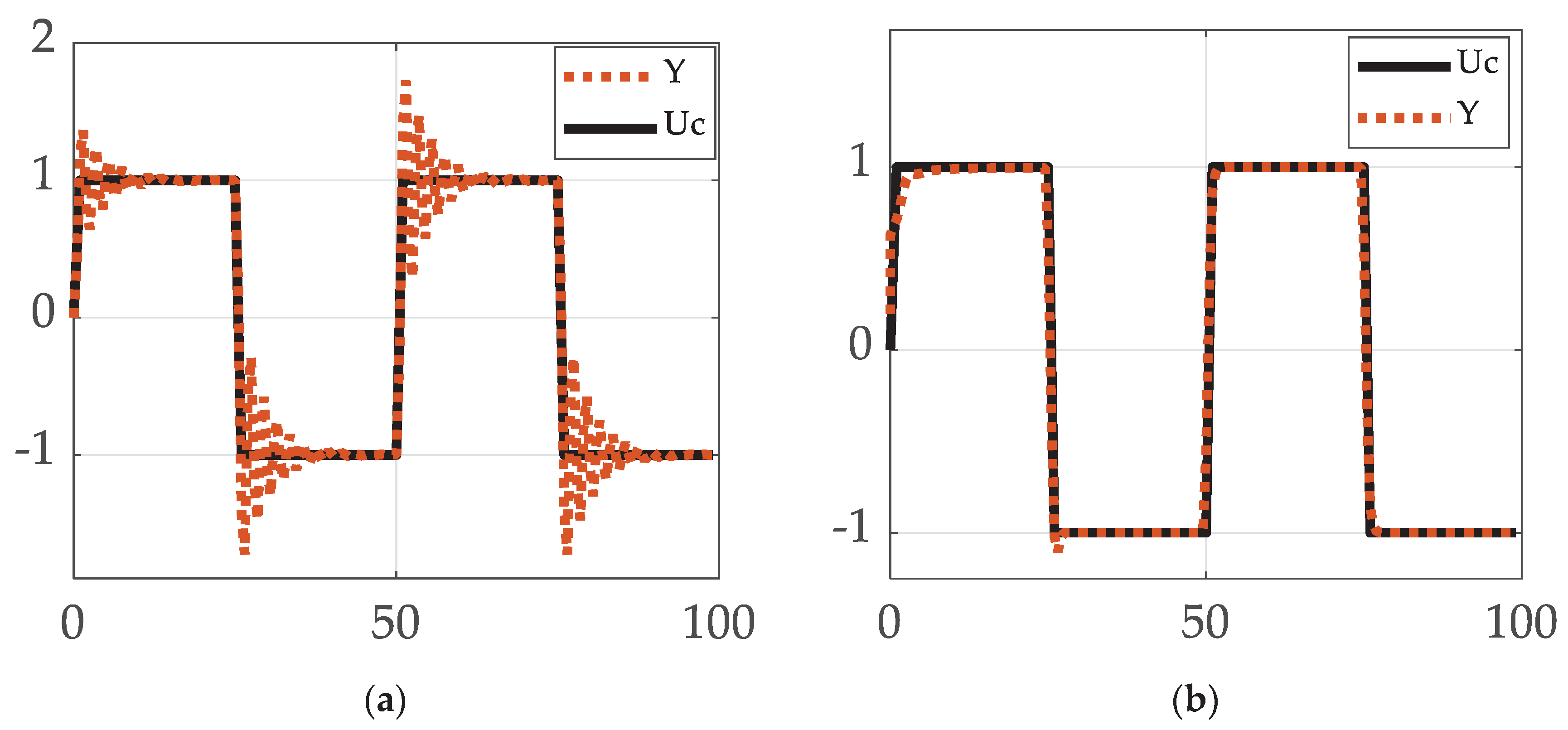

3.2. Discrete deterministic artificial intelligence v.s. Continuous deterministic artificial intelligence

4. Discussion

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

Appendix A.1. Discrete deterministic artificial intelligence

Appendix A.2. Continuous deterministic artificial intelligence

Appendix A.3. All deterministic artificial intelligence

References

- Harker, T. Department of the Navy Unmanned Campaign Framework, 16 March 2021. Available online: https://apps.dtic.mil/sti/pdfs/AD1125317.pdf (accessed on 7 December 2022).

- See, HA Coordinated Guidance Strategy for Multiple USVs during Maritime Interdiction Operations. Master’s Thesis, Naval Postgraduate School, Monterey, CA, USA, September 2017. Available online: https://apps.dtic.mil/sti/pdfs/AD1046921.pdf (accessed on 6 December 2022).

- Johnson, J.; Healey, A. AUV Steering Parameter Identification for Improved Control Design. Master’s Thesis, Naval Postgraduate School, Monterey, CA USA, June 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Sands, T. Control of DC Motors to Guide Unmanned Underwater Vehicles. Appl. Sci. 2021, 11, 2144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Underwater Thruster Propeller Motor for ROV AUV. Available online: https://www.alibaba.com/product-detail/underwater-thruster-propeller-motor-for-ROV_62275939884.html (accessed on 21 December 2022).

- Sarton, C.; Healey, A. Autopilot using differential thrust for Aries autonomous underwater vehicle. Master’s Thesis, Naval Postgraduate School, Monterey, CA USA, June 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Tan, W.; Healey, A. Horizontal steering control in docking the ARIES AUV. Master’s Thesis, Naval Postgraduate School, Monterey, CA USA, December 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, W.; Chen, Y.; Xia, Y.; Xu, G.; Zhang, W.; Wu, H. A Fault-tolerant Steering Prototype for X-rudder Underwater Vehicles. Sensors 2020, 20, 1816. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dinç, M.; Hajiyev, C. Identification of hydrodynamic coefficients of AUV in the presence of measurement biases. Proceedings of the Institution of Mechanical Engineers, Part M. Journal of Engineering for the Maritime Environment 2022, 236, 756–763. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gutnik, Y.; Avni, A.; Treibitz, T.; Groper, M. On the Adaptation of an AUV into a Dedicated Platform for Close Range Imaging Survey Missions. J. Mar. Sci. Eng. 2022, 10, 974. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rathore, Ankush and Mahendra Kumar. Robust Steering Control of Autonomous Underwater Vehicle: based on PID Tuning Evolutionary Optimization Technique. International Journal of Computer Applications 2015, 117, 1–6. [CrossRef]

- Sands, T. Development of deterministic artificial intelligence for unmanned underwater vehicles (UUV). J. Mar. Sci. Eng. 2020, 8, 578. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koo, S.M.; Travis, H.; Sands, T. Impacts of Discretization and Numerical Propagation on the Ability to Follow Challenging Square Wave Commands. J. Mar. Sci. Eng. 2022, 10, 419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shah, R.; Sands, T. Comparing Methods of DC Motor Control for UUVs. Appl. Sci. 2021, 11, 4972. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bernat, J.; Stepien, S. The adaptive speed controller for the BLDC motor using MRAC technique. IFAC Proc. Vol. 2011, 44, 4143–4148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gowri, K.; Reddy, T.; Babu, C. Direct torque control of induction motor based on advanced discontinuous PWM algorithm for reduced current ripple. Electr. Eng. 2010, 92, 245–255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rathaiah, M.; Reddy, R.; Anjaneyulu, K. Design of Optimum Adaptive Control for DC Motor. Int. J. Electr. Eng. 2014, 7, 353–366. [Google Scholar]

- Haghi, P.; Ariyur, K. Adaptive First Order Nonlinear Systems Using Extremum Seeking. In Proceedings of the 50th Annual Allerton Conference on Communication Control, Monticello, IL, USA, 1–5 October 2012; pp. 1510–1516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sands, T. Virtual sensoring of motion using Pontryagin's treatment of Hamiltonian systems. Sensors 2021, 21, 4603. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vidlak, M.; Gorel, L.; Makys, P.; Stano, M. Sensorless Speed Control of Brushed DC Motor Based at New Current Ripple Component Signal Processing. Energies 2021, 14, 5359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, J.; Wang, J.; Wang, W. Robust Adaptive Control for Nonlinear Aircraft System with Uncertainties. Appl. Sci. 2020, 10, 4270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Åström, K.; Wittenmark, B. Adaptive Control; Addison-Wesley: Boston, FL, USA, 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Slotine, J.; Benedetto, M. Hamiltonian adaptive control on spacecraft. IEEE Trans. Autom. Control 1990, 35, 848–852. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Slotine, J.; Weiping, L. Applied Nonlinear Control; Prentice Hall: Englewood Cliffs, NJ, USA, 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Fossen, T. Comments on "Hamiltonian Adaptive Control of Spacecraft". IEEE Trans. Autom. Control 1993, 38, 671–672. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sands, T.; Kim, J.J.; Agrawal, B.N. Improved Hamiltonian adaptive control of spacecraft. In Proceedings of the IEEE Aerospace, Big Sky, MT, USA, 7–14 March 2009; IEEE Publishing: Piscataway, NJ, USA, 2009; pp. 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smeresky, B.; Rizzo, A.; Sands, T. Optimal Learning and Self-Awareness Versus PDI. Algorithms 2020, 13, 23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fossen, T. Handbook of Marine Craft Hydrodynamics and Motion Control, 2nd ed.; John Wiley & Sons Inc.: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2021; ISBN 978-1-119-57505-4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fossen, T. Guidance and Control of Ocean Vehicles; John Wiley & Sons Inc.: Chichester, UK, 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Sands, T.; Bollino, K.; Kaminer, I.; Healey, A. Autonomous Minimum Safe Distance Maintenance from Submersed Obstacles in Ocean Currents. J. Mar. Sci. Eng. 2018, 6, 98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sands, T.; Lorenz, R. Physics-Based Automated Control of Spacecraft. In Proceedings of the AIAA Space Conference & Exposition, Pasadena, CA, USA, 14–17 September 2009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Available online: https://site.ieee.org/ias-idc/2019/01/29/prof-bob-lorenz-passed-away/ (accessed on 12 December 2022).

- Zhang, L.; Fan, Y.; Cui, R.; Lorenz, R.; Cheng, M. Fault-Tolerant Direct Torque Control of Five-Phase FTFSCW-IPM Motor Based on Analogous Three-phase SVPWM for Electric Vehicle Applications. IEEE Trans. Veh. Technol. 2018, 67, 910–919. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Apoorva, A.; Erato, D.; Lorenz, R. Enabling Driving Cycle Loss Reduction in Variable Flux PMSMs Via Closed-LoopMagnetization State Control. IEEE Trans. Ind. Appl. 2018, 54, 3350–3359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flieh, H.; Lorenz, R.; Totoki, E.; Yamaguchi, S.; Nakamura, Y. Investigation of Different Servo Motor Designs for Servo Cycle Operations and Loss Minimizing Control Performance. IEEE Trans. Ind. Appl. 2018, 54, 5791–5801. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flieh, H.; Lorenz, R.; Totoki, E.; Yamaguchi, S.; Nakamura, Y. Dynamic Loss Minimizing Control of a Permanent Magnet Servomotor Operating Even at the Voltage Limit When Using Deadbeat-Direct Torque and Flux Control. IEEE Trans. Ind. Appl. 2019, 3, 2710–2720. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flieh, H.; Slininger, T.; Lorenz, R.; Totoki, E. Self-Sensing via Flux Injection with Rapid Servo Dynamics Including a Smooth Transition to Back-EMF Tracking Self-Sensing. IEEE Trans. Ind. Appl. 2020, 56, 2673–2684. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sands, T. Comparison and Interpretation Methods for Predictive Control of Mechanics. Algorithms 2019, 12, 232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Method | Step Size [seconds] |

Error Mean | Error Standard Deviation |

|---|---|---|---|

| Deterministic artificial intelligence | 0.60 | 6.3918 | 4.8100 |

| Model following | 0.60 | 0.0264 | 0.0973 |

| Deterministic artificial intelligence | 0.50 | 0.0956 | 0.1632 |

| Model following | 0.50 | 0.0277 | 0.0917 |

| Deterministic artificial intelligence | 0.27 | 0.0175 | 0.0545 |

| Model following | 0.27 | 0.0471 | 0.1745 |

| Deterministic artificial intelligence | 0.20 | 0.0114 | 0.0487 |

| Model following | 0.20 | 0.0608 | 0.2446 |

| Deterministic artificial intelligence Type | Step Size [sec] | Error Mean | Error Standard Deviation |

|---|---|---|---|

| Discrete | 0.50 | 0.0956 | 0.1632 |

| Continuous | 0.50 | 0.0223 | 0.1654 |

| Discrete | 0.20 | 0.0114 | 0.0487 |

| Continuous | 0.20 | 0.0122 | 0.1401 |

| Method | Step Size [sec] | Error Mean | Error Standard Deviation |

|---|---|---|---|

| DAI | 0.60 | 6586% | 2847% |

| MF | 0.60 | -72% | -40% |

| DAI | 0.50 | 0% | 0% |

| MF | 0.50 | -71% | -44% |

| DAI | 0.27 | -82% | -67% |

| MF | 0.27 | -51% | 7% |

| DAI | 0.20 | -88% | -70% |

| MF | 0.20 | -36% | 50% |

| Deterministic artificial intelligence type | Step Size [sec] | Error Mean | Error Standard Deviation |

|---|---|---|---|

| Discrete | 0.50 | 0% | 0% |

| Continuous | 0.50 | -77% | 1% |

| Discrete | 0.20 | -88% | -70% |

| Continuous | 0.20 | -87% | -14% |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).