1. Introduction

The reflection of light as a mechanical phenomenon [

1,

2,

3] considers the speed of light independent from its moving source and its reflection similar to a ball by a mirror in motion. This study continues with emission, propagation, and reflection of light as mechanical phenomena in inertial frames [

4], observation of a star’s orbit [

5], a general consideration of light reflection [

6,

7], and here with the reflection of light applied to the Miller experiment [

8,

9].

The emission, propagation, and reflection of light in inertial frames [

4] conclude that physics phenomena in an inertial frame can be studied in any other inertial frame considered at relative rest. Here, the Sun’s frame at relative rest replaces the absolute frame for physics studies in Earth’s inertial frame. Thus, the Sun is a fixed light source for Earth, and Earth may be considered an inertial frame in the Sun’s frame at relative rest at the time of an experiment. The light from the Sun travels at the constant speed

in any direction in the Sun’s frame at relative rest.

The reflection of light as a mechanical phenomenon applied to Michelson’s interferometer with a particular geometry [

1,

2] predicts zero fringe shift, and to a geometry [

3] close to that presented in the Michelson-Morley experiment [

10] offers

fringe shift and greater for other geometries. Michelson’s derivation predicts a

fringe shift.

This paper applies the theoretical derivation [

1,

2] and numerical calculation [

3] to Miller’s experiments. Unlike the Tomaschek experiments [

11], the fringe shifts in Miller’s experiments are predictable.

The reflection of light as a mechanical phenomenon [

1,

2,

5] based on the elastic collision of balls with a wall in motion at the limit when the mass of balls converges to zero offers the equation

In Equation (1), is the speed of a reflected wavefront of a ray of light by a mirror in motion, is the wavefront speed from the source or a mirror as a source, is the mirror speed in the opposite direction of the incident wavefront from the source, and is the mirror speed in the direction of the reflected wavefront. Here, these speeds are in the Sun’s frame at relative rest. The mirror moves in one unique observable direction with speed . However, regarding the light wavefront, as far as the collision effect is concerned, it has multiple directions of and at the moment of collision according to the mirror inclinations. Speeds and are projections of in their corresponding directions.

Another form of Equation (1) is

In Equation (2), the speeds and replace and in Equation (1), respectively. Angle corresponds to the opposite direction of the incident wavefront, and angle to the direction of the reflected wavefront. These angles are measured from the direction of velocity vector , originating at the point of collision. The directions

of and are outward from the point of collision.

Michelson [

10] derives the fringe shift in the space filled with ether. Consequently, the speed of light from a source before and after reflection is the constant

. The study of light reflection as a mechanical phenomenon [

1,

2,

5] occurs in a vacuum. Like a ball in an elastic collision with a wall, the wavefront speed changes after reflection by a moving mirror. Therefore, the difference between these two approaches is the reflection of light by a moving mirror.

2. Interferometer on the Earth’s Equator

2.1. General considerations

The following drawings illustrate a way to bring the light from the Sun to a modified Michelson interferometer. For simplicity, Earth’s axis has no tilt.

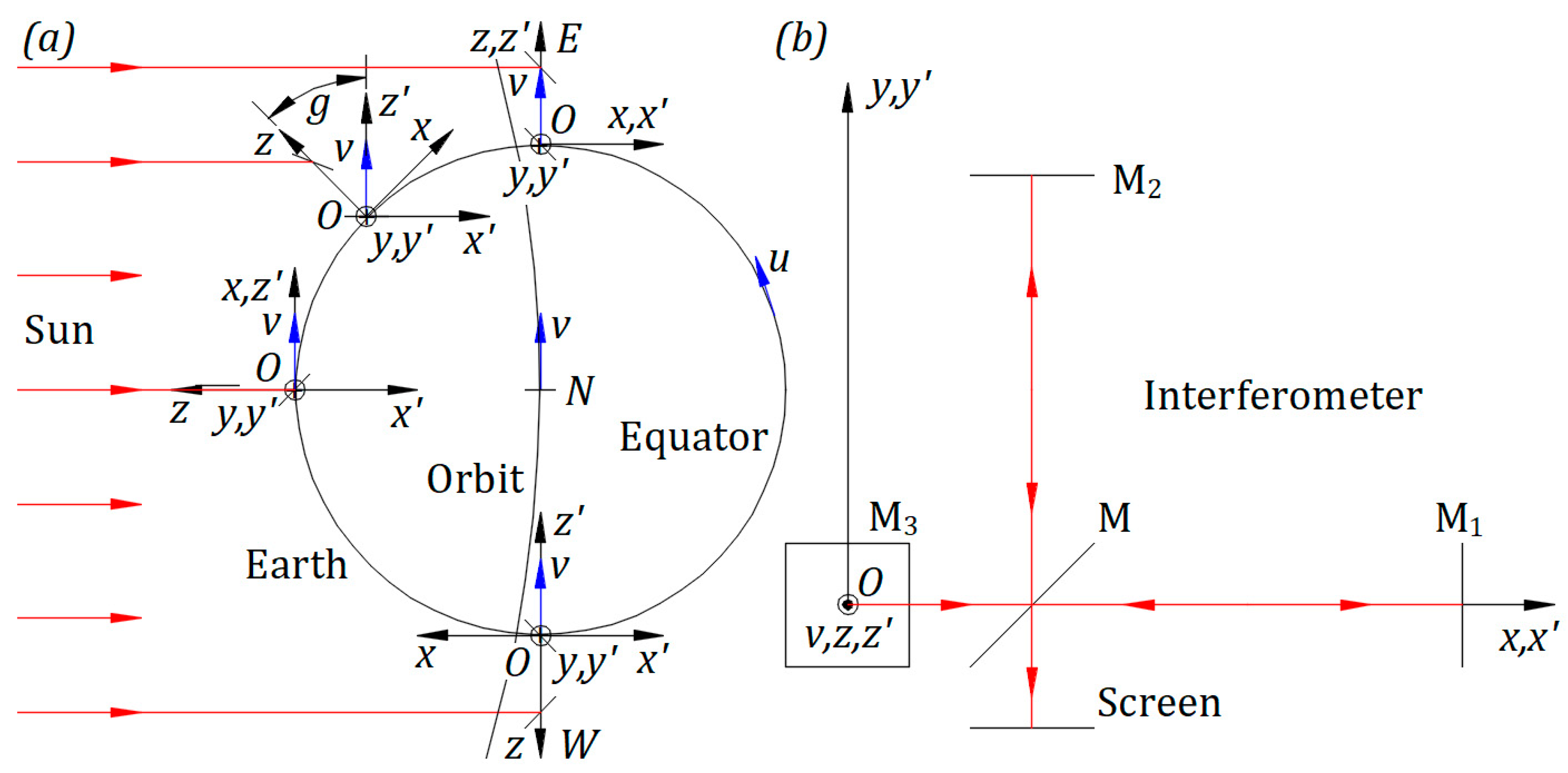

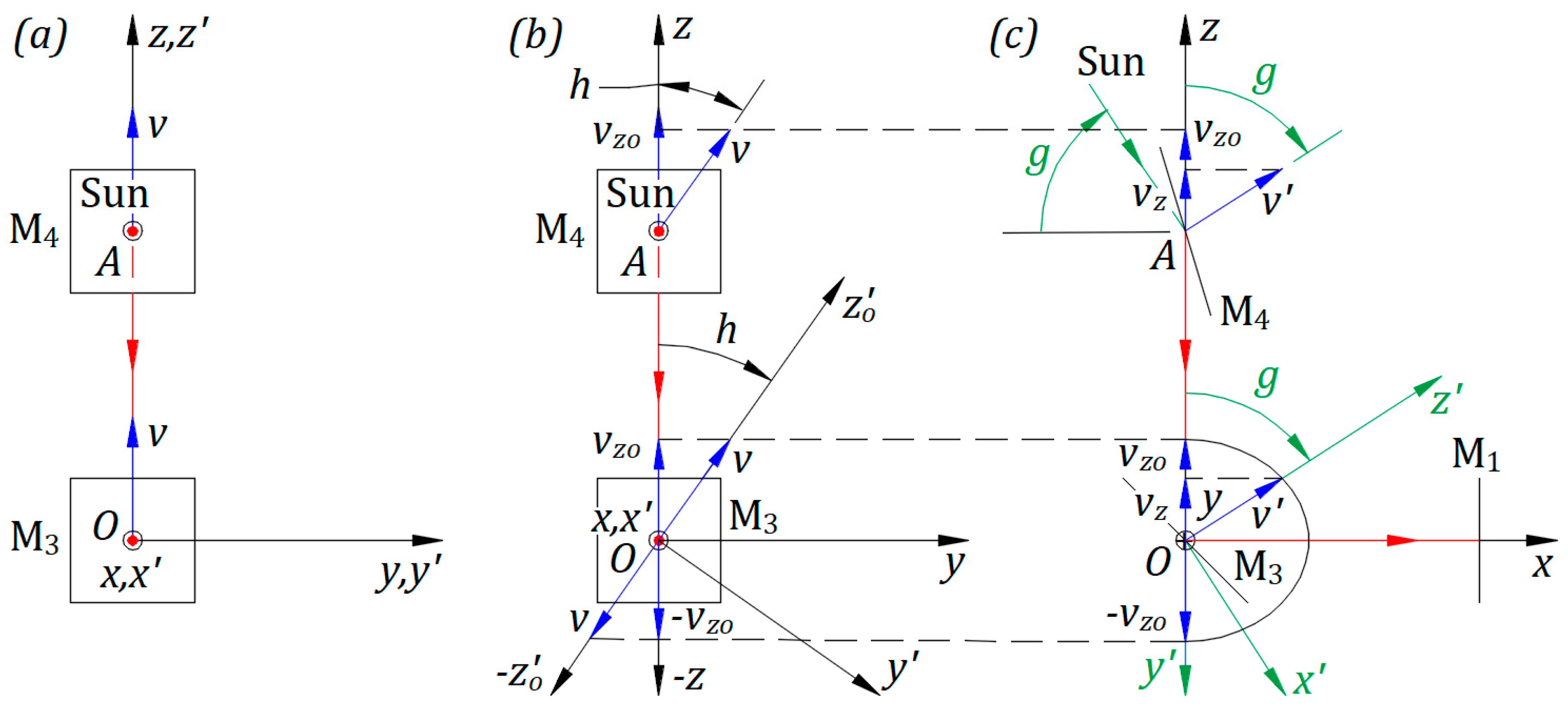

Figure 1(a) illustrates Earth's equatorial circle, Earth's revolving orbit around the Sun, and the center of the Sun and Earth in the same plane. The North Pole is outward, and the South Pole is inward, perpendicular to the paper plane.

An observer in the Sun’s frame at relative rest also perceives the physics phenomena as a local observer in Earth’s inertial frame. The observer’s location is on the North side of the Equator.

Figure 1(b) illustrates the Michelson interferometer at 6 am, as seen from the top side of

Figure 1(a). Mirrors M

1, M

2, M

3, and beam splitter M belong to the instrument. Mirror M

3 replaces the instrument’s source of light.

The cartesian frame , fixed to the instrument, originates at point of M3. Axis is on the horizontal line, and axis is perpendicular to Earth’s local surface. Plane is parallel to Earth’s local surface and perpendicular to the local Earth’s radius. At 6 am, the revolving velocity of Earth coincides with .

The interferometer is in plane

. It rotates counterclockwise around

with an angle

measured from

. The initial position of the instrument is when direction

coincides with

for

, as shown in

Figure 1(b).

In the Sun’s frame at relative rest, a vector velocity in the direction of the cartesian frame is attached permanently to the origin of . Earth’s spin changes the origin position of and ; different from , keeps its axes’ directions fixed in the Sun’s frame at relative rest.

The instrument on the Equator belongs to a local Meridian. The Equator's start position can be defined when: the local Meridian of the instrument is at 6 am, frames

and

coincide, and the device is at the initial position, as illustrated in

Figure 1(b).

In the Sun’s frame at relative rest, the center of the Sun, Earth’s orbit, and the Equator’s circle are always in the same plane. Planes and belong to Equator’s plane. Plane is parallel to Earth’s local surface and perpendicular to Equator’s plane. Axes and are overlapping from 6 am to 6 pm.

Earth’s spin changes the position of . At the same time, in plane , axis rotates clockwise around , keeping the directions of unchanged. with the vector velocity at makes the angle measured from .

Figure 1(a) indicates the position of the interferometer at 6 am, which is the Equator's start position, corresponding to

. Earth’s spin brings the interferometer to an angle

between 6 am and 6 pm, to

at noon, and

at 6 pm.

2.2. Interferometer on the Equator at 6 am, noon, and 6 pm

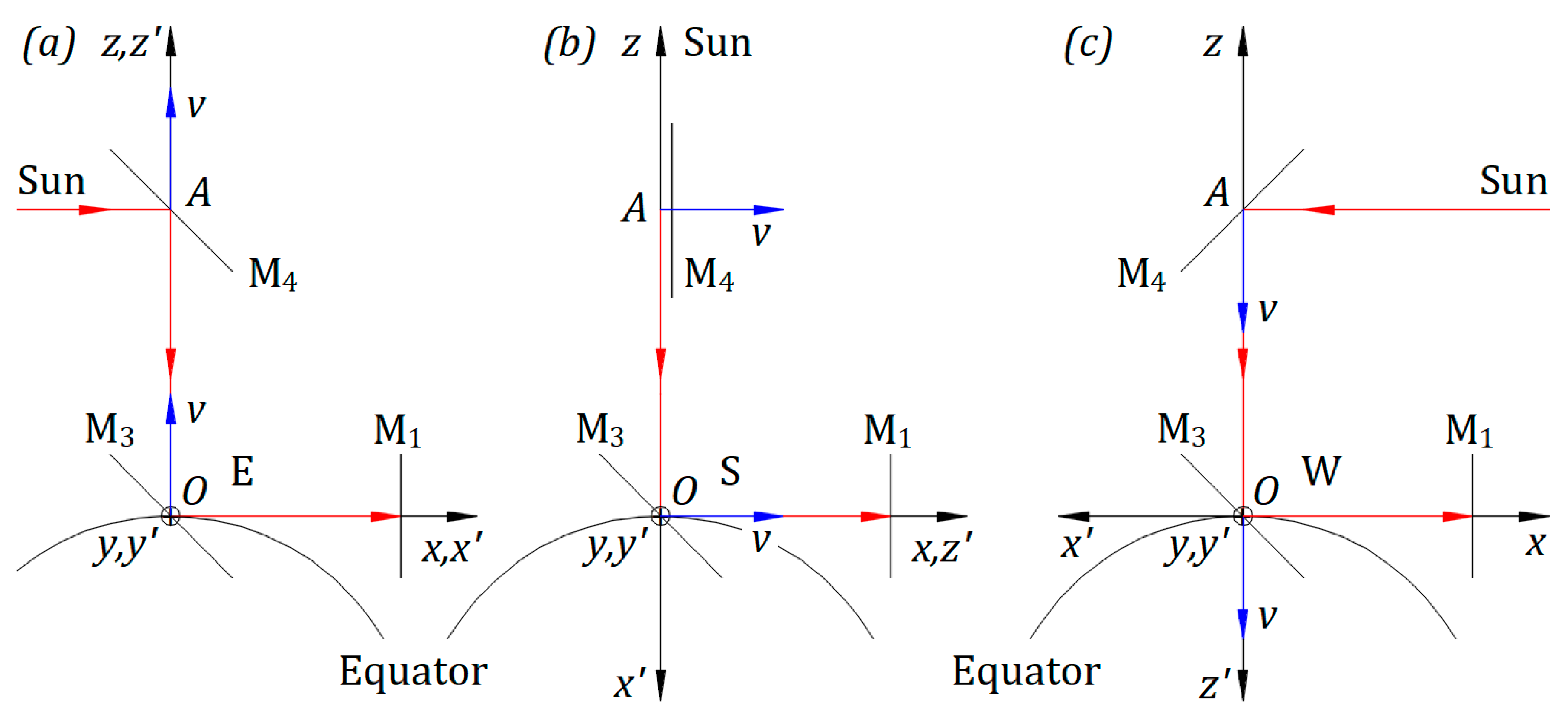

Figure 2(a) depicts the Equator's start position at 6 am for

. Earth’s spin brings the interferometer at noon, as illustrated in

Figure 2(b) for

, at 6 pm, as presented in

Figure 2(c) for

, and in general, at a time between 6 am and 6 pm, as shown in

Figure 3(a) for an angle

.

Point belongs to mirror M4 and to axis . Mirror M4, axis , mirror M3, and interferometer form a solid structure. Mirror M4 rotates at the Equator around an axis through point perpendicular to . At the North Pole around axis . And between the Equator and the North Pole around both. M4 stays fixed while the interferometer rotates around axis .

Considering that the Sun emits parallel rays of light in the direction from the Sun’s center toward Earth’s center, only these rays are reflected by M4 in the opposite direction to toward M3. The incident rays from the Sun are perpendicular to at any location on Earth.

In

Figure 2(a), point

of M

4 reflects the ray of light toward

with the speed

given by Equation (2),

.

The ray reflected at along and for has the speed . With , .

The projection of on is . The rays reflected by M3 drift transversal opposite to velocity .

In Figure 2(b), the light from the Sun travels perpendicular to ; therefore, no need for mirror M4. At this position, M4 rotates around to continue reflecting rays for .

The ray reflected at along and for has, according to Equation (2), the speed .

The projection of on is zero. Thus, there is no transversal drift on rays reflected at M3.

Figure 2(c) shows the device at 6 pm. Point

of M

4 reflects the ray of light toward

with the speed

given by Equation (2),

.

The ray reflected at along and for has the speed .

The projection of on is . The rays reflected by M3 drift transversal opposite to velocity .

2.3. Interferometer on the Equator at an angle g

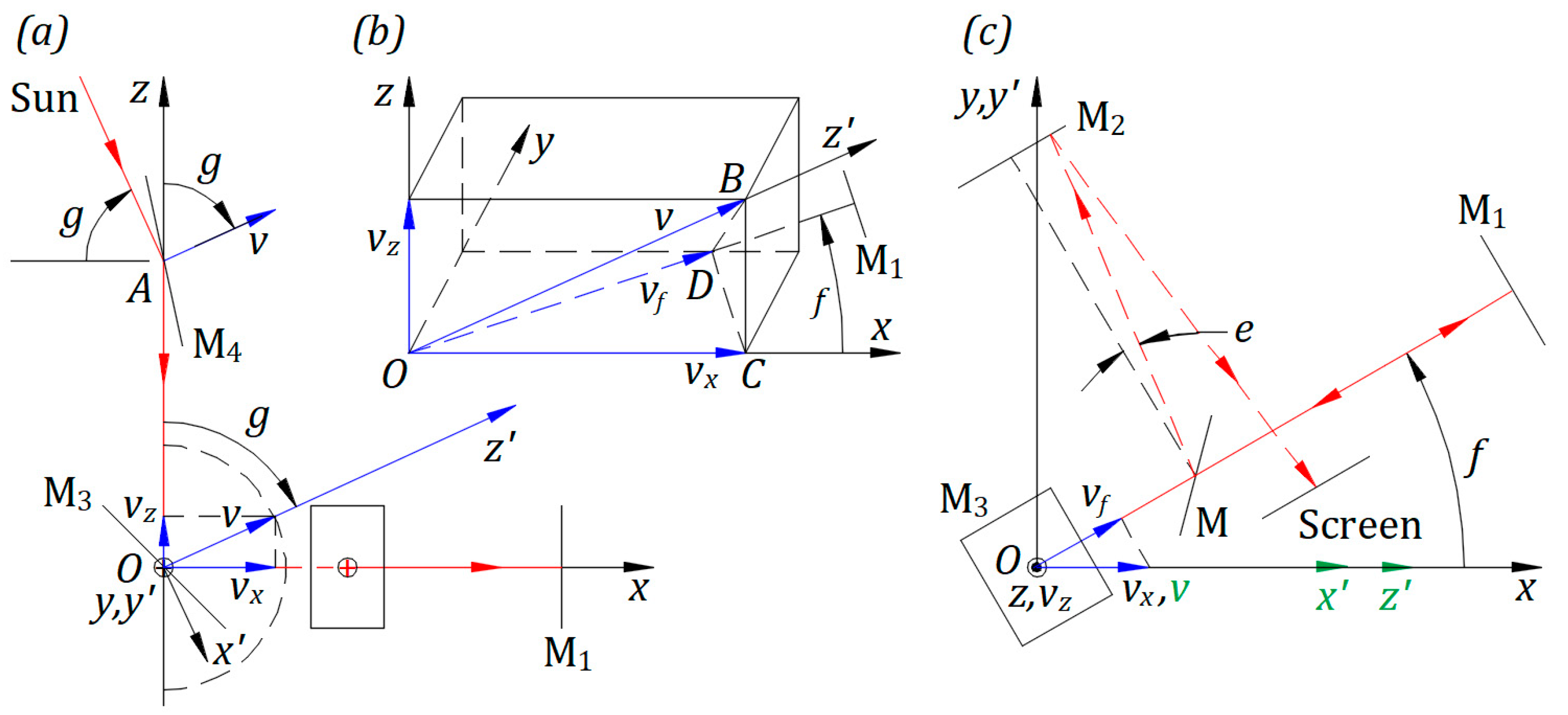

Figure 3(a) presents the instrument between 6 am and 6 pm when

makes an angle

measured from

. To reflect the rays in the direction

, M

4 rotates around the axis through point

and perpendicular to

. Angle

has an opposite direction to Earth’s spin.

From 6 am to 6 pm for

, projection of

on

is the transversal speed of the instrument in the Sun’s frame at relative rest

Projection of

on

is the longitudinal speed of the instrument in the Sun’s frame at relative rest

, then

Figure 3(b) is a detail at point

in a three-dimensional view when the instrument is at an angle

from

.

and

planes and their intersection along

are perpendicular to

, and

is perpendicular to

. Therefore,

is perpendicular to plane

, and

is perpendicular to

. Thus, the projections of

and

on

are identical to

; with

from Equation (4),

Figure 3(c) illustrates the top side view of

Figure 3(a) with the interferometer rotated by an angle

from

. For the geometry presented in Ref. [

3], reflected rays by beam splitter M travel as illustrated at an angle

from the perpendicular line to M

2.

,

and

in green indicate that they are not in plane

.

Point

of M

4 reflects the ray of light toward

with the speed

that gives the equation

The ray from

reflected at

along

, employing Equation (2), has the speed

. With

from Equation (6) and

from Equation (4),

yields the equation

The reflected speed of light at

along

at an angle

is

, therefore,

3. The Interferometer on the North Pole

The solid structure, illustrated in

Figure 2(a), brought from the Equator at 6 am along the local Meridian at the North Pole, looks like in Figure 4(a). From the Equator to the North Pole, the frame

rotates

in the Sun’s frame at relative rest. In plane

,

rotates

around

from

to

; after rotation,

has the same direction as

. Planes

and

coincide and are parallel to Equator’s plane. Axis

is perpendicular to Equator’s plane.

Earth’s spin rotates

in the Sun’s frame at relative rest. In plane

,

rotates around fixed

from

at 6 am at angle

, as illustrated in

Figure 4(a), to

at noon at angle

, as in

Figure 4(b), and to

at 6 pm at angle

, as in

Figure 4(c). At the North Pole, mirror M

4 rotates only around

.

4. Interferometer on a Latitude

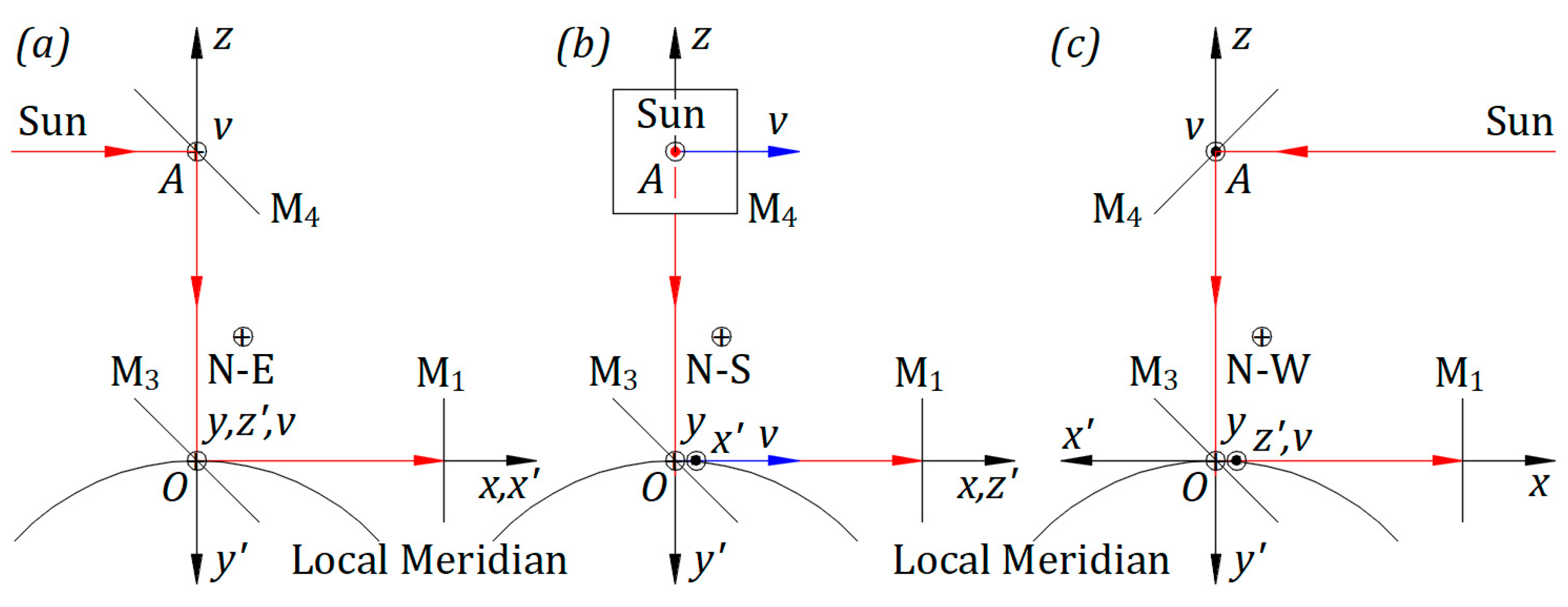

The right side view of

Figure 2(a), ignoring M

1, is as in

Figure 5(a). Moving the solid structure from the Equator toward the North Pole,

rotates in the Sun’s frame at relative rest. Velocity

with its axis

rotates in plane

around

with angle

measured from axis

, as visualized in

Figure 5(b). For

, the interferometer is at the Equator, and for

at the North Pole. In the rotation on a Meridian, from the Equator to the North Pole, Mirror M

4 stays fixed.

In

Figure 5(b), we can define the Latitude's start position at the intersection of the local Meridian with the local Latitude at 6 am.

is marked with index o for angle

,

, and is in plane

making an angle

measured from

.

Plane is parallel, and axis is perpendicular to Equator’s plane here and at any location on Earth. Plane is parallel, and the axis is perpendicular to Earth’s local surface as on any place on Earth. and are perpendicular to plane and intersect along .

Earth’s spin rotates the frame on the Latitude from 6 am to 6 pm. At the same time, velocity with its axis rotates around fixed axis from at 6 am for angle to at noon for and to at 6 pm for . Thus, on a Meridian, angle is identical when the instrument is on different Latitudes to that at the Equator. On a Latitude, mirror M4 rotates around both axes to capture only the parallel rays from the Sun.

The view from the opposite direction of

shows vector

with its axis

rotating from 6 am to 6 pm on a semicircle with origin at

and radius

. The semicircle is in plane

. Any angle

yields an identical image. The semicircle is identical to that in

Figure 3(a), illustrated in a dashed line in plane

.

The view from the opposite direction of

sees the semicircle projection of the vector

as a semi-ellipse in plane

, as illustrated in

Figure 5(c). The projection points of this semi-ellipse on

represent the speeds

for angles

.

Figure 5(c) is the left side view of

Figure 5 (b) for an angle

measured from

. The projection of the velocity

that belongs to

on plane

is

.

,

, and

axes are depicted in green to indicate that they are not in plane

;

is in the front, and

and

are in the back of plane

.

Planes and intersect along . coincides with only at . Axis rotates in the back of plane from at the Latitude’s start position when it is behind for to plane coinciding with for . Then rotates in front of plane to for , above . rotates in front of plane from for to above for , then to for .

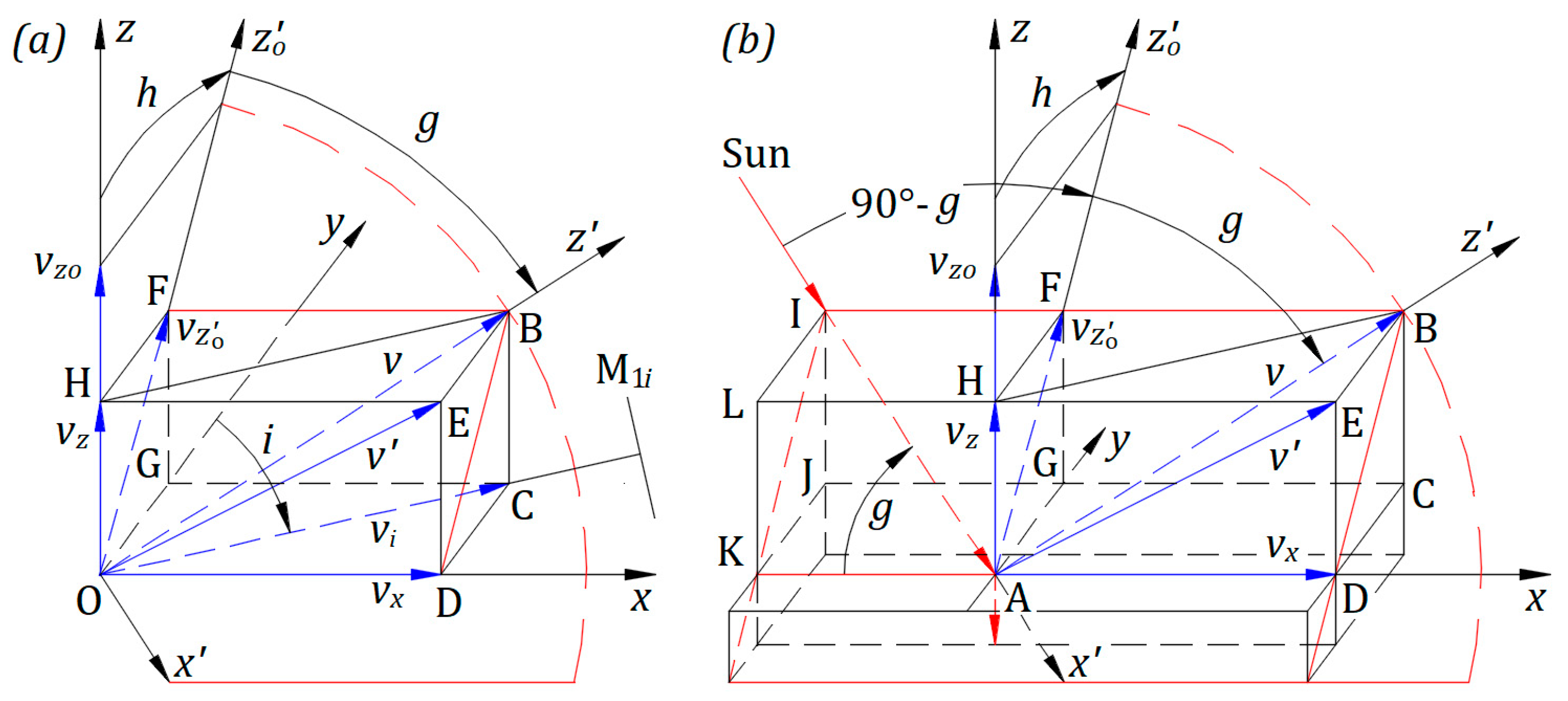

Figure 6(a) offers a three-dimensional visualization of the mechanical velocities at point

of

Figure 5(c). Axis

is in plane

. Rectangular

belongs to

,

to

, and

to

. The speed

is along axis

. Index

for

indicates that mirror M

1 location corresponds to angles

defined below. Velocities

and

belong to rectangular

of the plane in red;

and

to plane

.

The projection of

on

at the Latitude’s start position offers the equation

The projection of

on

is

, therefore,

The projection of

on

,

, is also the projection of

on

. Employing Equation (10),

is the transversal speed of the instrument in the Sun’s frame at relative rest.

The projection of

on

is

, therefore,

. From triangle

, the longitudinal velocity of the instrument in the Sun’s frame at relative rest has the magnitude of

that with

from Equation (11) yields the equation

In triangle

,

, then

Angle indicates the interferometer's initial position direction when and directions coincide.

Figure 6(b) offers a three-dimensional visualization of the mechanical velocities at point

of

Figure 5(c). At

, we can attach the same frame as at

,

, and

. Axis

is in plane

. Velocities

and

belong to rectangular

with its sides in red, which belongs to

. The ray from the Sun travels in this plane along the line

. Point

of M

4 reflects it towards

. M

4 must be adjusted with both axes to reflect the incident ray at

along

’s direction towards

.

The ray of light reflected at

toward

has the speed

that gives the equation

From

Figure 6(a), the speed of light reflected in the direction

for angle

,

, offers the equation

Equation (16) corresponds to Equation (7) when the interferometer is on the Equator.

For the same reason as in

Figure 3(b), the projections of

and

along

are identical for any angle

measured from

. The speed of light reflected at

in the direction of

for an angle

measured from

is

that yield the equation

Equation (17) corresponds to Equation (8) when the interferometer is on the Equator.

5. Numerical calculation of the fringe shift

For the length

m of the interferometer’s arms, Miller expected a

fringe shift based on Michelson’s derivation [

10] and observed, at Mount Wilson,

in 1921 and

in 1925 [

8,

9]. The observations taken in the laboratory at Cleveland 1924, with sunlight and laboratory sources, show a null result of experiments. The above discrepancy in experimental results requires a theory to support it or a reevaluation of Miller’s experiments.

The velocity is the moving velocity of the instrument in the Sun’s frame at relative rest. The device has the longitudinal velocity at Equator and on a Meridian parallel to and the transversal velocity perpendicular to plane . To correctly calculate the fringe shift within the interferometer, we have to consider both velocities, but there is no such theoretical derivation.

In the following derivation, we assume that the fringe shift is not affected by the transversal speed

, and we calculate the fringe shift for the four positions offered by Ref. [

3].

The numerical calculation can be performed on a spreadsheet according to the theoretical derivation of Ref. [

3], starting with the set of speeds

,

,

,

, and

, followed by the times the light travels its paths and their differences, and finally, the fringe shift, for each of the four positions at angle

,

, and

.

The initial position of the interferometer for

corresponds to the

position in Ref. [

3] because between the two selected initial positions, there is a difference of

. Thus, for

,

,

, and

positions correspond to

,

,

, and

positions in Ref. [

3].

The speed

from Equation (17) replaces the speed

correspondingly in the sets of speeds

,

,

,

, and

in the four positions as defined in Ref. [

3]. The numerical magnitude of speed

from Equation (13) replaces speed

in all four positions of Ref. [

3], including in the sets of speeds mentioned above.

In Ref. [

3], rays along the screen interfere because their speeds,

and

, are equal. Ref. [

3] derives the difference between the two light paths in the number of wavelengths

with formula

, where

is the difference of time the two rays travel their paths with the same or different speeds,

is the constant

m/s, and

the wavelength of light for constant

.

If the speed of the two interfering rays increases or decreases, their wavelengths increase or decrease directly proportional. Therefore, the ratio speed/wavelength is a constant for any of their corresponding speeds/wavelengths. Therefore, are not affected by the speed magnitude of rays that interfere along the way to the screen. Thus, no need to change the formula .

For any location on Earth, the numerical calculation of the fringe shift, for m, predicts unobservable fringe shifts in the range. For m, the fringe shift is in the range of . The rays reflected by M4 coming from different points of the Sun, or corresponding to different altitudes, or magnitudes of angle greater than aberration angle do not change the result of the fringe shifts.

In Ref. [

3], different from this article, the source of light is a part of the interferometer belonging to Earth’s inertial frame. For

m, the fringe shift is

, and for

m, the fringe shift is

. According to emission, propagation, and reflection of light as mechanical phenomena in inertial frames [

4], the fringe shift in the Michelson interferometer is zero.

5. Conclusions

With the assumption that the transversal velocity of the interferometer does not affect the fringe shift, Michelson derivation does not agree with Miller’s experiments at Mount Wilson in 1921 and 1025 and with those at Cleveland laboratory in 1924. The derivation based on the reflection of light as a mechanical phenomenon does not agree with Miller’s experiments at Mount Wilson but agrees with experiments at Cleveland laboratory with sunlight and laboratory sources.

When the local meridian is at noon, from the Equator to the North Pole, there is no transversal speed for the instrument, and the numerical calculation yields zero fringe shift. Miller observed fringe shifts at Mount Wilson for these positions as well. Therefore, a derivation considering the transversal speed should not affect the fringe shift for these positions and is not likely for any position of the instrument on Earth.

For any angle , the speed of light , and the longitudinal speed of the interferometer is . Thus, the speed of light within the interferometer is , which could explain why the fringe shift is zero or undetectable.

The Tomaschek experiment [

11] may display a fringe shift if the star's velocity in the Universe is different from that of the Sun. The light from a star arrives on Earth, no matter the distance from the star to the Sun, with two components: the emitted velocity

and the star's velocity [

4,

5]. The fringe shift depends on the difference of star and Sun velocities. Experiments consist of trials and observations with different stars without any expectations. Nevertheless, the theoretical derivation is more complex, even if we know the star's velocity to the Sun.

However, regardless of the outcome of a complete theoretical derivation, the contradictory results observed at Mount Wilson and the Cleveland laboratory leave this subject open to theoretical and experimental challenges.

Ref. [

3] offers zero fringe shift for

rad,

for aberration angle

rad, and greater than

for an angle

beyond the aberration angle. We chose a geometry for theoretical derivation and calculation of the fringe shift, but an experiment yields a fringe shift according to an unknown geometry. The author expected this study to predict Miller's observations at the Mount Wilson and Cleveland laboratory because different actual geometries of the interferometer's light paths, which imply different angles

, could explain the observations at the two locations.

References

- Filipescu, F. D. Reflection of Light as a Mechanical Phenomenon Applied to a Particular Michelson Interferometer. Preprints 2020, 2020090032. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Filipescu, F. D. Opposing hypotheses of the reflection of light applied to the Michelson interferometer with a particular geometry. Phys. Essays. 2021, 3, 268–273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Filipescu, F. D. Opposing hypotheses of the reflection of light applied to the Michelson interferometer. Phys. Essays. 2021, 3, 389–396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Filipescu, F. D. Emission, propagation, and reflection of light as mechanical phenomena in inertial frames. Phys. Essays 2021, 34, 587–590. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Filipescu, F. D. Observation of a star's orbit based on the emission and propagation of light as mechanical phenomena. Phys. Essays. 2022, 2, 111–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Filipescu, F. D. Emission, Propagation, and Reflection of Light as Mechanical Phenomena. Preprints 2022, 2022040061. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Filipescu, F. D. Emission, propagation, and reflection of light as mechanical phenomena: General considerations. Phys. Essays. 2022, 3, 266–269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miller, D. C. Ether-Drift Experiments at Mount Wilson. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 1925, 6, 306–314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Miller, D. C. The Ether-Drift Experiment and the Determination of the Absolute Motion of the Earth. Reviews of Modern Physics. 1933, 5, 203–242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Michelson, A. A.; Morley, E. W. On the relative motion of the earth and the luminiferous ether. Am. J. Sci. 1887, 203, 333–345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tomaschek, R. Über das Verhalten des Lichtes außerirdischer Lichtquellen. Ann. Phys. 1924, 378, 105–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).