1. Introduction

The affordances of reflective writing activities, such as blogging, are widely acknowledged in contemporary education, especially when the development of intercultural competencies (henceforth, ICC) is one of the learning objectives. Several authors (e.g. Elola & Oskoz (2008), Holmes & O’Neill (2012) and Jaidev (2014), amongst others) have promoted blogging as a useful activity to accompany immersive intercultural learning experiences such as an internship abroad, for multiple reasons: blogging is a time and place independent learning activity that deepens reflective thinking, cultural knowledge and self-knowledge, whilst at the same time it encourages peers to learn from each other (Hoefnagels & Schoenmakers, 2018).

Until recently, research was mainly focused on the organizational preconditions to make blogging a success. Teachers should provide clear instructions, technical support (Hourigan & Murray, 2010), a safe psychological environment (Chan, Wong & Luo, 2020) and regular feedback and guidance, to enhance the depth of reflection in the blogs (Carney, 2007; Lee, 2012) and deepen the intercultural learning path of students (Pinilla et al., 2013; Chen, 2014). At the same time, it is acknowledged that reflective writing is a challenging activity for students (Ramlal & Augustin, 2020), who often fail to reach in-depth reflection (Strampel & Oliver, 2008; Lucas & Fleming, 2012) because they are unfamiliar with the demands associated with this type of learning activity (Hourigan & Murray, 2010) or even feel uncomfortable writing about intercultural experiences that are often personal and emotional in nature (Chan, Wong & Luo, 2020). As a result, the sole fact of combining an internship with reflective blogging – or, in more general terms, combining experience with reflection − does not automatically lead to the desired intercultural learning outcomes (Jackson, 2015). Without proper guidance or feedback (viz., the above last-mentioned precondition), students will not automatically overcome the specific challenges imposed by the genre: they will not achieve the desired level of reflection and long-term intercultural learning goals will not be met (Ramlal & Augustin, 2020).

Yet, providing effective feedback is easier said than done. The few studies we found highlight that teachers often lack training in effectively deploying reflective activities in the classroom (van der Werf & van der Poel, 2014; Chan, Wong & Luo, 2020; Ramlal & Augustin, 2020), which leads to large differences in how they handle reflective writing assignments (Chen, 2014). A possible explanation for this might be the lack of insight we have into how a complex competence such as ICC manifests itself in the language use of learners. In order to be able to provide effective feedback to enhance the level of reflection in student blogs, teachers need tangible cues on which to base their assessment. And these cues might be found if we would study the language use of students as a source of information for their learning process and development.

Whereas former studies mostly focus on the challenges of reflective writing activities in the classroom or the benefits of reflective blogging to foster ICC, our study aims to identify tangible ‘linguistic markers’ for ICC in student blogs, to help students and teachers engage in a meaningful dialogue about intercultural learning experiences. Such ‘linguistic markers’ will not only support teachers in assessing the quality of the blogs, but also allow them to pinpoint concrete areas for improvement in their feedback and interaction with students.

In this paper we will analyze a corpus of roughly 1,600 student blogs that were written by students during an internship abroad, by means of the LIWC methodoloy (Linguistic Inquiry and Word Count) developed by the social psychologist James Pennebaker (2011; Pennebaker, Booth, Boyd & Francis, 2015) to investigate whether specific word patterns in student blogs can be linked to the students’ ICC development. Although a text-analytical approach is common practice in psychology to seek connections between language use and psychological variables such as mental health, personality or even leadership styles, and the LIWC methodology has been successfully implemented in domains like education, health, communication or political science (Dudău & Sava, 2021), it still is quite novel in the context of ICC development.

This study will not only provide a quantitative analysis to detect systematic differences in language use between blogs that have been classified as displaying high ICC and blogs that have been classified as displaying low ICC, we will also account for these numeric differences by linking them to different dimensions of ICC − such as reflection, curiosity and openness − and other contextual elements in support of the blog’s overall ICC score. By doing so, we aim to answer the following research question:

Which linguistic markers for intercultural competence can be identified in the language use of students blogging about intercultural experiences?

In the remainder of the text, we will first elaborate on the theoretical foundations of our study. Furthermore, we will describe some initial experiences and observations concerning blogging that led to the main research question of this paper. Then, we will explain our methodology and analytical approach, together with the main results of our study. Finally, we will discuss the implications of these results for theory and educational practice.

2. Theoretical Background

If the aim of this study is to identify linguistic markers of ICC to help teachers monitor and stimulate the ICC development of their students during an internship abroad, then we first have to explain how this need arose and how our approach, i.e. the textual analysis of student blogs, can offer a solution.

The Importance of Reflection for the Development of ICC

If we look at Deardorff’s (2006) definition of ICC as the “the ability to communicate effectively and appropriately in a variety of cultural contexts with people who are different than oneself, based on one’s intercultural knowledge, skills and attitudes”, it immediately becomes clear that an important role in the development of ICC is reserved for experiential learning (Allport, 1954). By coming into contact with people from different cultural backgrounds, you learn not only how cultures differ, but also which behaviors are effective and appropriate in different cultural contexts. This explains why in educational settings, many internationalisation initiatives are focused on providing students with intercultural learning experiences, either at home, in the so-called international classroom, or abroad, during study sojourns or work placements (Gregersen-Hermans, 2016). Such experiences can be expected to reduce negative stereotypes and create more openness towards other cultures and nationalities, which is an important precondition for the development of ICC (Deardorff, 2006).

The beneficial effects of international study sojourns or work placements have indeed been demonstrated by several authors. For example, Marcotte, Desroches and Poupart (2007) reported positive effects on cultural awareness, while Crossman and Clark (2010) found that an international study experience enhances language acquisition and the development of soft skills related to cultural understanding, personal characteristics and ways of thinking. Furthermore, multiple studies have reported a direct impact of international study sojourns on the development of cultural intelligence and multicultural personality (Boonen, Hoefnagels & Pluymaekers, 2019; Engle & Crowne, 2014; Brown, 2009; Leong, 2007).

However, there is also empirical evidence which suggests that the effects of an international study sojourn are less straightforward than previously assumed (Schartner, 2016; Strong, 2011; Shaules, 2007; Leask, 2015; Coleman, 1998) and that immersion in a different socio-cultural environment does not in itself reduce stereotypical thinking (Dervin, 2008). For example, Salisbury, An and Pascarella (2013) found an increase in students’ diversity of contact but no effect on students’ relativistic appreciation of cultural differences or comfort with these differences. Other studies have found students to return home more ethnocentric and less willing to interact with people who have a different linguistic and cultural background (Hoefnagels & Schoenmakers, 2018; Jackson, 2015).

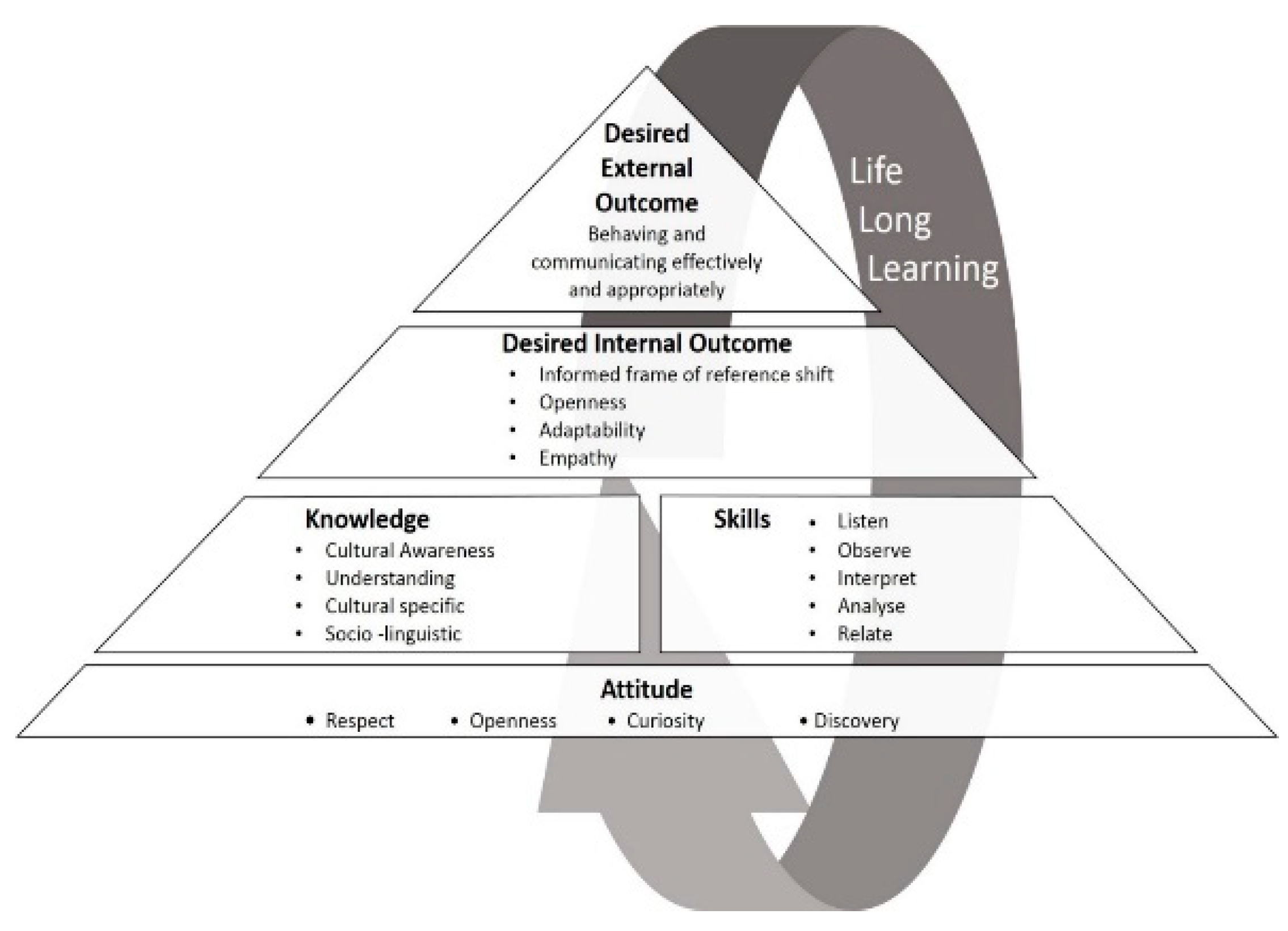

In order to decrease the likelihood of such negative outcomes, it is argued that students should be stimulated to reflect on their experiences (Alred, Byram & Fleming, 2003; Kruse & Brubaker, 2007; Jackson, 2010; Vande Berg, 2009). The importance of reflection for the development of ICC is also acknowledged in prominent models of ICC development. Deardorff (2006), for example, considers skills such as listening, observing, analysing and relating as necessary stepping stones for the achievement of internal outcomes (cultural empathy and an informed frame of reference shift) as well as external outcomes (the ability to behave and communicate effectively and appropriately in intercultural situations). Furthermore, she stresses the cyclical nature of the learning process, which ensures that new concrete experiences lead to the further refinement of previously acquired knowledge, skills and attitudes (see

Figure 1).

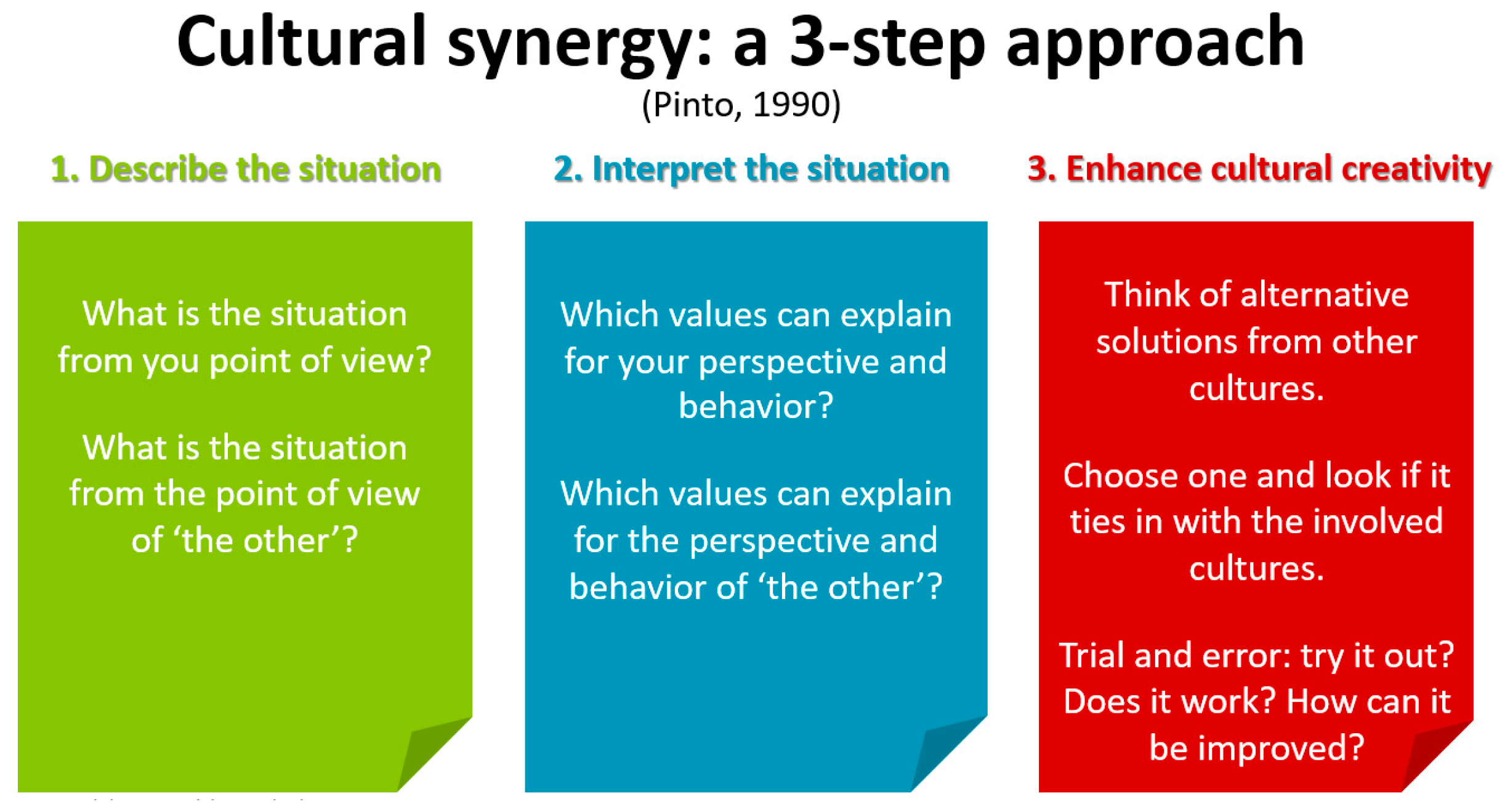

In Pinto’s (1990) model of cultural synergy (see

Figure 2), reflection also plays an important role in correctly interpreting the intercultural experience (step 3) to pave the way for creative and alternative outcomes.

Blogging to Stimulate Reflection

Reflection during an intercultural learning process can be stimulated in different ways. Many of the proposed activities in literature require students to write about their experiences in ethnographic assignments (e.g., Kruse & Brubaker, 2007), research reports (e.g., Holmes & O’Neill, 2012), or reflective blogs (e.g., Elola & Oskoz, 2008; Lee, 2011; Jaidev, 2014). The fundamental idea is that describing and explaining intercultural experiences can help students make sense of these experiences, and thereby strengthen their effects on the development of ICC (Messelink, Van Maele & Spencer-Oatey, 2015; Hoefnagels & Schoenmakers, 2018).

One form that seems to be gaining popularity over the last years is blogging. According to Hoefnagels & Schoenmakers (2018), reflective blogging has several affordances that make it a suitable tool for enhancing the development of ICC in the 21st century. Besides deepening reflective thinking and self-knowledge (Bartlett-Bragg, 2013; Osman & Koh, 2008), blogging also enhances community learning and enables students to acquire a rich body of knowledge.

Despite these promising affordances, it is important to note that asking students to write about intercultural experiences does not necessarily mean that they will automatically also reflect on them (Jackson, 2015). This became clear from early observations we made in our own blog corpus, in which students magnified and overgeneralized specific elements of their experience in relation to the Spanish (1) or German culture (2), as can be seen in the examples below:

- (1)

People in Spain don’t like to admit the fact that they are wrong. They won’t say ‘thank you’ when you help them out, let alone that they will say that you are right. This all had to do with the fact that Spanish people are long term orientated. […] Very different from Dutch people, who will thank you immediately.

- (2)

As we now know, the German eating-habits are quite strange for a Dutchmen. But being not flexible in the Gastronomy, is something we can't imagine actually! We were not able to find ourselves a restaurant, to serve us breakfast at 11 o’clock!! Eventually, that wasn't a big issue, because eating a Double Cheese-burger is also a very steady breakfast of course, and it was great to show my parents how crazy this eating-habit is here in Germany! After all, my parents and I concluded that the German Gastronomy culture isn't that flexible perhaps... I'm sure in Amsterdam for example, we would certainly be able to find a restaurant to serve us breakfast, even when their menu-card says it doesn't anymore.

These examples not only show the difficulty students experience having to write and reflect on culture; they also point out the challenge for teachers who want to help students develop their ICC. In these blogs, the language use of students serves as a vehicle of information on the students’ development of ICC, offering the reader concrete cues – henceforth referred to as linguistic markers – of their reflective learning process. In example (1), the ethnocentric attitude of the author manifests itself in the antagonistic use of the adjectives right versus wrong, in relation to different kinds of ‘people’, viz. the Dutch versus the Spanish. In example (2), the use of intensifiers such as very and certainly, in addition to polarising adjectives pointing at extremes such as crazy, weird, strange and sure, or decisive verbs such know or conclude highlight a lack of empathy and nuance. In both examples, language or word use provides the teacher insights into the student’s learning process. However, it remains difficult to uncover this information without proper training or knowledge on which markers one should look for. In order to prevent teachers from making ad hoc associations between words and ideas, we aim to systematically identify patterns in language use that can be linked to ICC.

Language in Relation to ICC

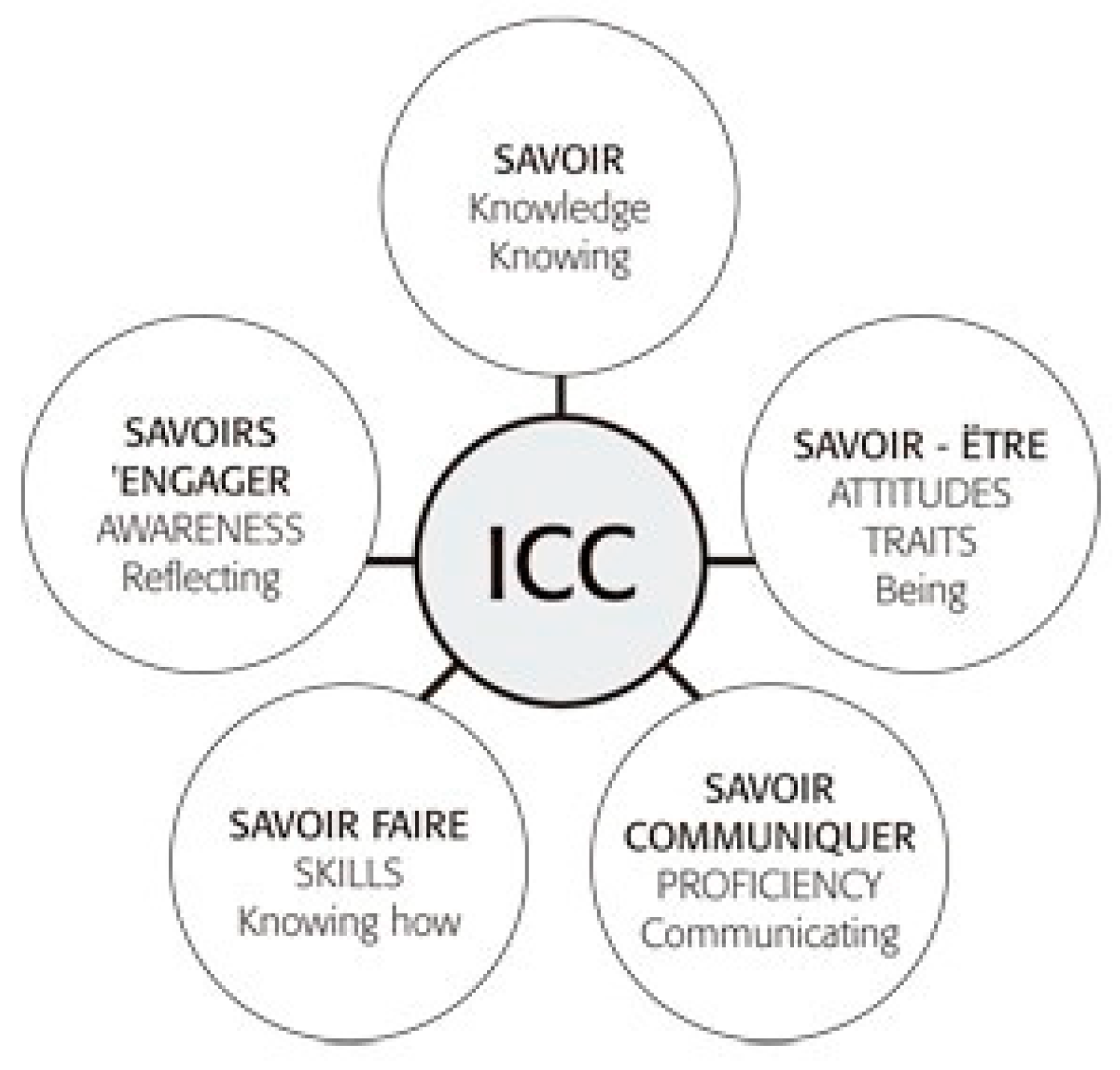

Traditionally, ICC has been closely linked to language education. Until recently, ICC was mostly framed as a dimension of or a goal in foreign language learning (Belz, 2002, 2003; Liaw, 2006; Lomicka, 2006; Mueller-Hartmann, 2006; O’Dowd, 2003, 2006; Schneider & von der Emde, 2006). Byram’s (1997) intercultural speaker model has long been the main frame of reference to study ICC in a language learning context, providing students with concrete objectives to become intercultural speakers or ‘mediators’ in interaction with people of different origins and identities.

Figure 3 describes the five components needed to become an intercultural speaker according to this model: a curious and open attitude to suspend cultural (dis)beliefs (

savoir être), knowledge of different cultural modes of interaction (

savoir), skills to interpret and relate cultural symbols and values, and the ability to transfer this all into real-time communication (

savoir communiquer) and interaction (

savoir faire), whilst being aware of how own values might interfere when evaluating others (

savoir s’engager).

Elola & Oskoz (2008) pioneered in adapting and using Byram’s framework to analyze the comments on blogs which functioned as a mediating tool between students abroad (i.e., in Spain) and students at home (i.e., in the United States). In these blogs, the authors looked for textual evidence on the five components of Byram’s model, which they rephrased as follows (Elola & Oskoz, 2008: 464):

- (3)

The interest in knowing other people’s way of life and introducing one’s own culture to others;

- (4)

The ability to change perspective;

- (5)

The ability to cope with living in a different culture;

- (6)

The knowledge about one’s own and others’ cultures for intercultural communication;

- (7)

And the knowledge about intercultural communication processes.

This qualitative analysis then resulted in a number of blog excerpts that could be considered evidence of certain aspects of ICC. Despite good inter-rater reliability, however, it remained unclear what the researchers were relying on. Which linguistic elements prompted them to refer to that particular fragment as, for instance, evidence of the ability to change perspective?

Although this shows that Byram’s framework may be suitable for assessing ICC at a holistic, macro-textual or paragraph level, we feel that the language used by students in writing about intercultural experiences offers the possibility to take the analysis to a next level: An analysis at micro-textual or word level.

A Text Analytical Approach to Identify linguistic Markers for ICC

If we no longer perceive language exclusively as a vehicle to practice intercultural communication, but also recognize its potential as a monitoring tool for ICC development, we can draw parallels to the way reflective writing is studied in mental health sciences, where words are seen as tools to excavate people’s thoughts and feelings (Pennebaker, 2011). This would allow us to approach the student blogs as valuable containers of information about the students’ ability to reflect on intercultural experiences and, consequently, their ICC development.

We derive this idea from Pennebaker (2011), a psychologist who studied the words of his patients as cues to their inner workings. Together with his team, he developed a computer program called LIWC (Linguistic Inquiry and Word Count) to count and categorize the words that patients used to write about traumatic experiences. Combining reflective therapeutic writing (as input) with computer technology (to quickly analyze large amounts of textual data), Pennebaker and his colleagues were able to detect patterns in word use that could be linked to age, gender, mental health, personality, and other psychological variables. For example, they used LIWC to link profiles on dating sites to certain personas, or to differentiate more task-oriented, high status profiles from more socially oriented, low status profiles within an organization.

Essentially, LIWC analyses text using a series of dictionaries. On the basis of these dictionaries, each word is labelled according to function and meaning, after which the program creates a statistical overview of the word usage in a text. Subsequently, it is up to the researcher to interpret and contextualize this quantitative information in the light of the main research question.

Some of the LIWC dictionaries also seem to link well to traits associated with ICC. In this paper, we will zoom in on the use of I-words as well as seven dictionaries linked to analytical thinking. More details about these dictionaries and their potential relation to ICC development is provided below.

First of all, the LIWC dictionary of

I-words contains different word categories that are all related to the expression of the first person singular, such as pronouns (

I, myself, me), possessives (

my, mine) or word strings combining one of these with a(n) (abbreviated) verb form (

I’d, I’ve, methink, …), and expressions (

idk, meaning ‘I don’t know’). According to Pennebaker (2011: 106-7, 278), a frequent use of I-words marks a more inward focus and, as such, can be linked to authors who are more self-aware and self-focused, who – if something happens − want to understand why it occurred. These self-conscious and self-critical authors also tend to be open-minded and more curious to discover new things; traits that are pre-conditional for the development of ICC (Deardorff, 2006) (

Figure 1). Moreover, the investigation of I-words resonates with the blogging assignment the students have received, which states that their blog should revolve around a unique, personal experience. The best intercultural observers can therefore be expected to describe in great detail the intercultural experience and the impact it has had on them, by writing from the I-perspective, as illustrated in (3).

- (8)

Travelling alone is one of the most exciting things I have been doing since I was 17. I got to know myself better, my horizon became broader and broader, I came across many new cultures and I always got the chance to be myself. But in the end, the most important thing of travelling alone is the fact that you will actually never feel alone. At least, if you are doing the things in the right way. How come? It is a matter of respect. Respecting yourself, respecting the values and norms of other cultures and being open minded about, actually, everything. In the very beginning, it was me often saying ‘no’. Saying no to activities, certain habits and especially saying no to people. Something I regret wholeheartedly. Since I have been saying yes, meeting new people and making new friends was the last thing I had to worry about. So this is exactly what I did during the first month in Hong Kong.

The other categories we will take into account for this analysis are the ones related to analytical thinking (Pennebaker, 2011: 80). These include:

- −

exclusives (but, without, except)

- −

negations (no, not, never)

- −

causal words (because, reason, effect)

- −

insight words (realize, know, meaning)

- −

tentative words (maybe, perhaps)

- −

certainty (absolutely, always), and

- −

quantifiers (some, many, greater)

According to Pennebaker (2011: 80), words from these dictionaries are frequently used when people try to make sense of what happens around them. Exhibiting a certain level of cognitive complexity, their use implies reflection on behalf of the speaker/writer, which we also expect to see in blogs from students who try to learn from their intercultural experiences. Authors who use many words associated with analytical thinking are supposed to be more open to new experiences, have more complex views of themselves and the world, and exhibit a higher cognitive complexity (Pennebaker, 2011: 162-3). Self-awareness, openness and reflection can also be found in theories and models of ICC as essential preconditions for achieving sustainable long-term intercultural learning outcomes (Byram, 1997; Deardorff, 2006).

In the following section we will explain how we added a text-analytical twist, based on the dictionaries offered by Pennebaker’s LIWC, to the more traditional holistic approach on ICC, in our quest to better support internship supervisors in responding to reflective blogging assignments.

3. Research Method and Results

3.1. Corpus Characteristics

The data presented here are drawn from a corpus of 1,635 blogs, written between December 2015 and March 2018 by 672 Hotel Management students during a semester-long work placement at a hotel abroad. All students were instructed to write three blogs in English

1 about authentic and personal intercultural experiences that occurred during their work placement. However, not all students submitted three blogs.

Table 1 shows how many authors wrote one, two, three or four blogs.

Following the principles of Pinto’s (1990) cultural synergy model (see

Figure 2), students were asked to start with a description of the experience, followed by a reflection on the subject and to end with some advice on how to handle a similar situation in the future.

All blogs were posted online in a closed community where they could be read, commented upon and graded by fellow students and supervisors. It should be noted that, unlike in other studies, the blogs were not used to exchange information between students at home and abroad. Furthermore, the comments posted by fellow students and supervisors were not included in the current study.

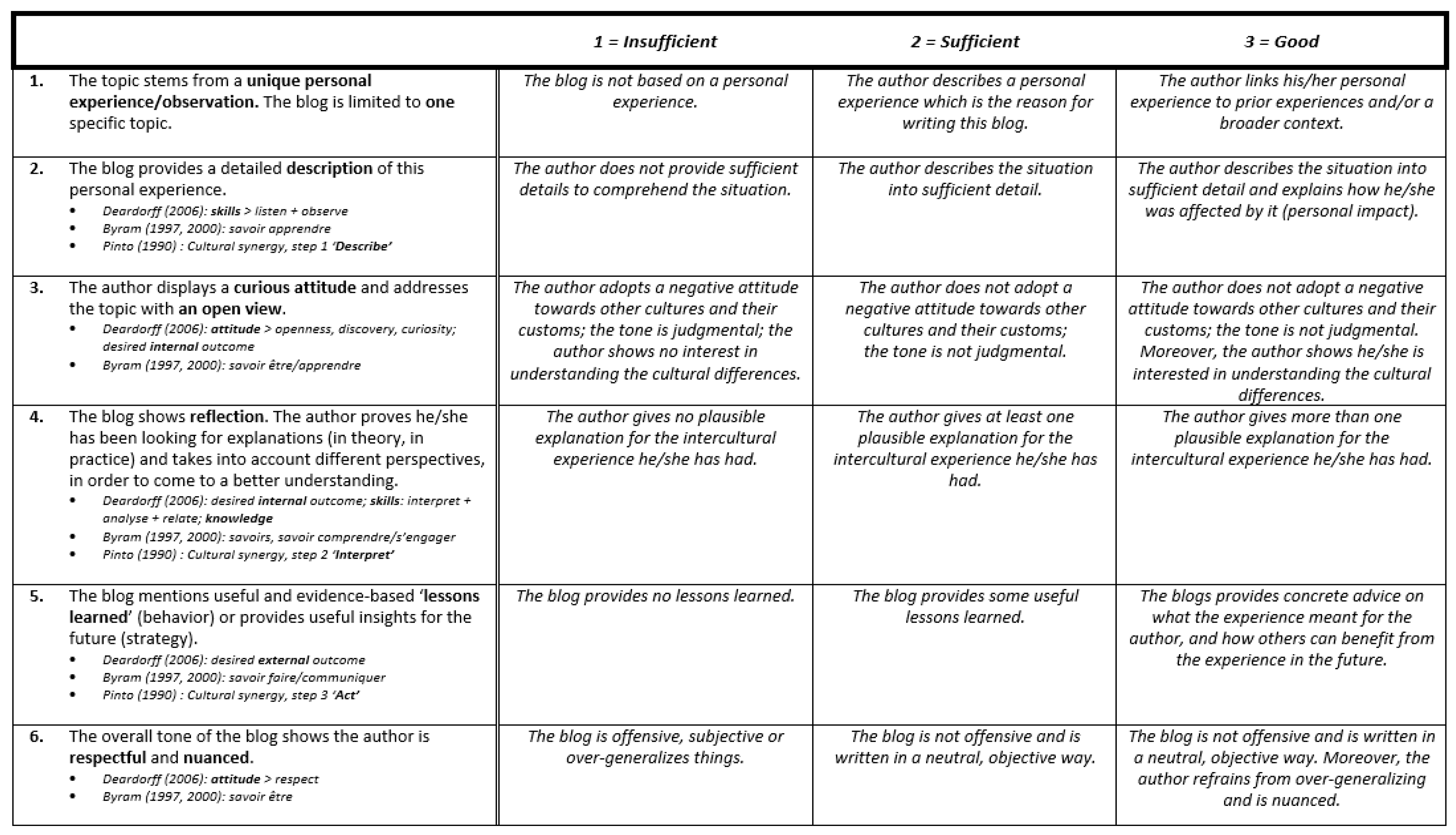

3.2. Analytical Approach

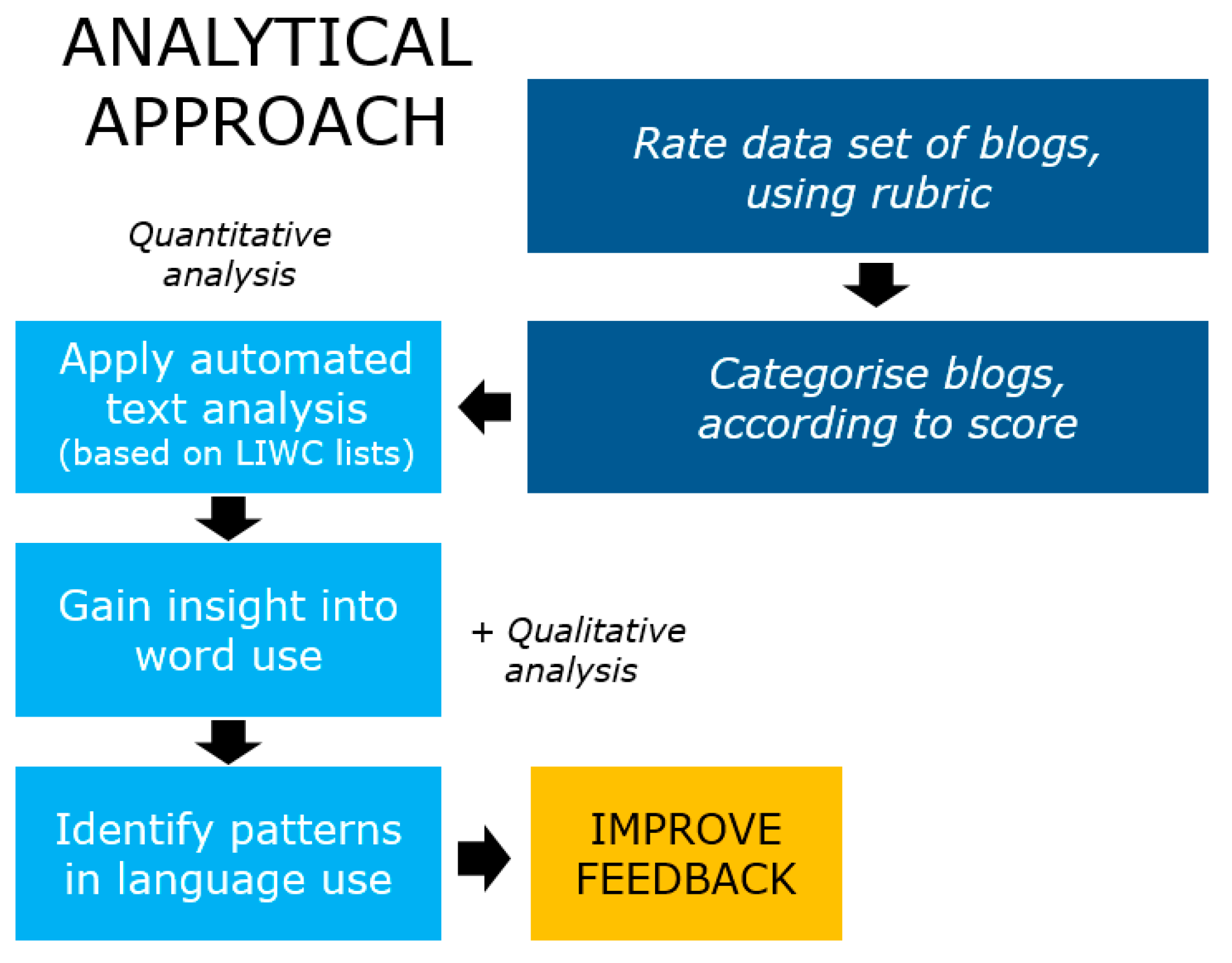

In our attempt to identify linguistic markers for ICC in the blogs, we took the approach visualized in

Figure 4. In the first phase of the study, all blogs were assessed to determine the overall level of ICC (

holistic, macro-textual level). In order to minimize the perceived subjectivity of this qualitative assessment (O’Connor & Joffe, 2020), we worked with a small group of five assessors: two lecturer-researchers, being the 1

st and 2

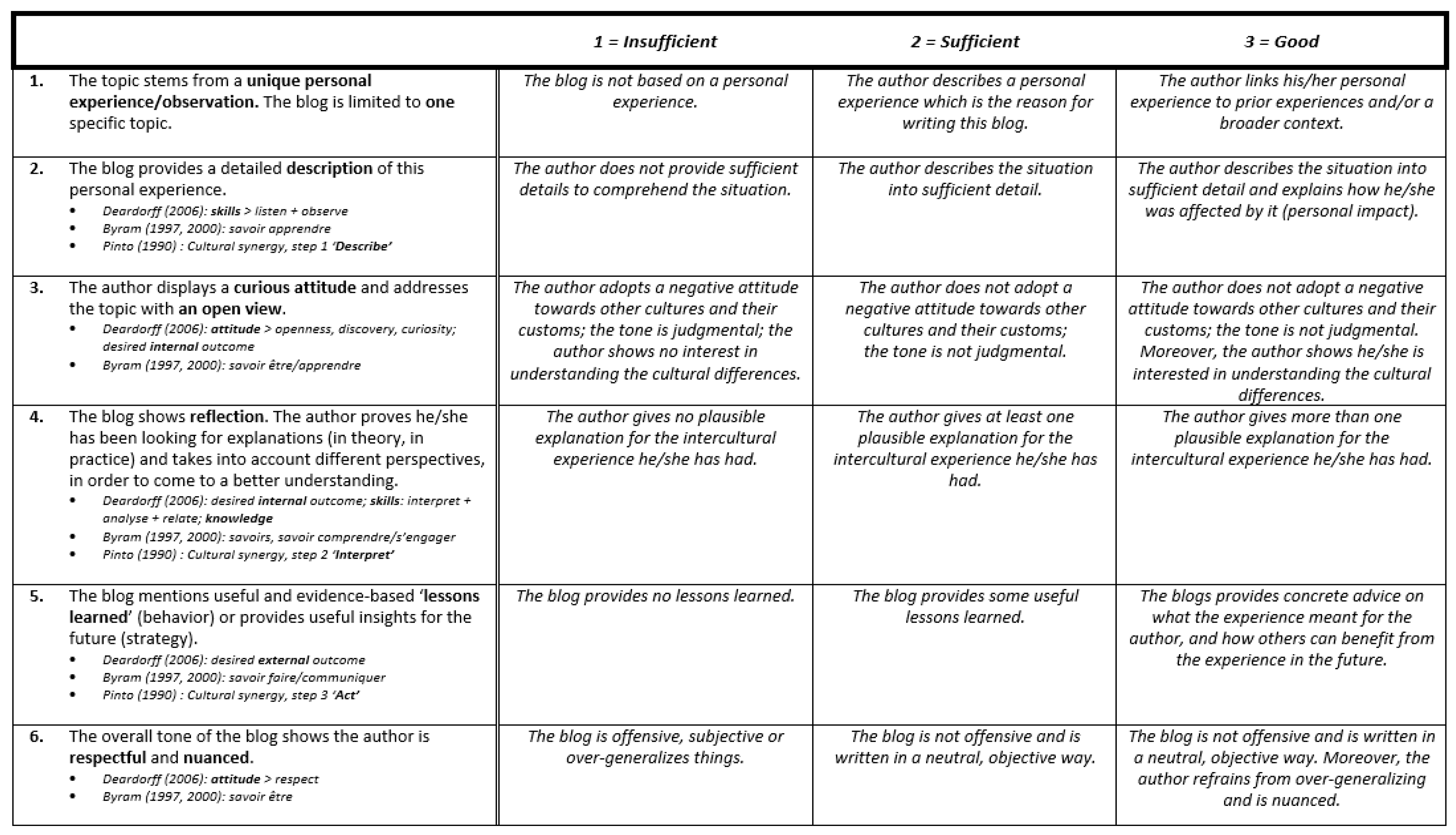

nd author of this article, and three senior students who had been trained as moderators on the blogging platform. To enhance inter-rater reliability, we created a rubric (included in the appendix) based on Byram’s intercultural speaker model (1997), which we further adapted and complemented using Deardorff’s pyramid model for ICC (2006) and Pinto’s cultural synergy model (1990). The rubric contains six criteria, for which three scores were possible: 1 = insufficient, 2 = sufficient and 3 = good. The rubric was pilot tested in two calibration sessions in which all assessors were involved. During these sessions we determined that a three-point scale was most suitable, and we also discussed possibly varying interpretations of these items. Once the inter-rater reliability could be ensured, the data set of blogs was divided amongst the different assessors. Each of them rated the six evaluation criteria per blog with a score ranging from 1 to 3. Finally, an overall mean score per blog was calculated, reflecting the blog’s overall level of ICC.

On the basis of the distribution of the rubric scores (mean score per blog), three sub-corpora were created to distinguish blogs exhibiting higher levels of ICC from blogs exhibiting lower levels of ICC:

Blogs with a score between 2 and 3 (high ICC, 344 blogs in total)

Blogs with a score between 1.667 and 2 (intermediate ICC, 622 blogs in total)

Blogs with a score between 1 and 1.667 (low ICC, 669 blogs in total)

Blogs which scored a 2 were placed in the intermediate category, while blogs which scored a 1.667 were placed in the low category. Such borderline cases were fairly frequent in the corpus, which explains why the number of blogs was not equal across the three groups. In the remainder of the analysis, only the high and low ICC groups (1 and 3) were compared. In

Table 2 below, you can find more information about these two sub-corpora.

In the second phase of the study, we compared the frequency of occurrence of words from multiple LIWC dictionaries in these two corpora (

analytical, micro-textual level). Since we were particularly interested in detecting the personal impact of intercultural experiences and the presence of reflection in the student blogs, we started our analysis using the LIWC dictionaries linked to self-awareness and analytical thinking, as explained at the end of

Section 2.

Differences in frequency of occurrence of words from these dictionaries in the high and low corpora were assessed using a t-test, following the recommendation of Lijffijt et al. (2016). For word categories that exhibited statistically significant differences, we conducted an additional qualitative analysis to gain more insight into the lexical differences between the high and low ICC corpora.

This integrated approach, combining a quantitative and qualitative text analysis, allows us to analyze a large corpus of texts in a targeted and fast manner. By adding a second, qualitative step to the statistical outcomes, we are able to interpret the results and to link them, in this case, to the differences in ICC score.

3.3. Results

Out of the eight dictionaries submitted to the t-test, three exhibited statistically significant differences:

I-words, insight words and

quantifiers (see

Table 3). The proportion of I-words and insight words was significantly higher in the high-ICC corpus than in the low-ICC corpus, whereas quantifiers were more frequently used in the low-ICC corpus than in the high-ICC corpus.

In the following sections, we will zoom in on the three word categories that – according to our statistical analysis – may function as ‘linguistic markers for ICC’. We will illustrate how these word categories manifests themselves in the blogs, in which contexts they are used and how their use may impact the perceived level of ICC. Subsequently, we will focus on the word level rather than the word category level, and see whether we can tie ICC to the use of specific words (rather than categories) in the blogs.

3.3.1. I-Words

Our hypothesis that student-bloggers using more I-words are more open-minded, self-aware and curious, seems to be confirmed when we look into the data: the t-test reveals that there are significantly more I-words in the blogs scoring high on ICC (see

Table 3). When we examine the blogs in which more I-words are used more closely, we notice that the more culturally sensitive author commonly writes from an I-perspective, relating the experience to prior knowledge and experiences and describing its personal impact. In that sense, the frequent use of I-words depicts a more immersed and involved author, as illustrated in example (4), where the author reverts to an I-word thirteen times to describe how a certain event impacted on her (

I feel that they value and respect my roots, language and culture; I feel so welcomed and accepted) and how she relates the situation to her own experience (

in my case) and identity (

I am from Brazil).

In example (5), by contrast, the author only uses three I-words when describing the experienced differences in culture. By refraining from the I-perspective, the author takes a more distant attitude, as if he were an outside witness observing what is happening around him.

- (4)

How do people usually react when you tell them where you are from? Well, in my case, there are different reactions, depending on where I am. Here in Paris when people ask me what my origins are and I tell them that I am from Brazil, I immediately get a smile on the person’s face, a happy reaction, a comment like “I love Brazilian music!” People react positively to the fact that I speak Portuguese, my colleagues at work as soon as there is someone from Brazil or Portugal they immediately call me. I feel that they value and respect my roots, language and culture. The reason why I feel so welcomed and accepted is due to the Multiculturalism in Paris, being its metropolitan area one of the most multi-cultural cities in Europe. According to the 2011 census, 20.3% of the population were born outside of France. Being most of the immigrants from the Maghreb countries (Algeria, Tunisia and Morocco). After French, those are the second more common nationalities at my work. As well as many people from Europe, such as Portugal, Romania, Germany, Bulgaria, Belgium and Moldavia. These aspects of Paris, therefore, make you feel surrounded by international people and it gives life to several different ethnic groups and shops in the 20 arrondissements. Paris has historically been a magnet for immigrants, hosting one of the largest concentrations of immigrants in Europe today. Its cultural diversity makes the city of lights a place for everyone, where I feel welcome being not the only one from a faraway foreign country. […] Concluding, because of Paris’ Multiculturalism, there is a place for everyone, allowing us to feel welcome here and equally respected as everyone else. Whenever you feel welcomed and respected by the people around you, you feel home.

- (5)

-

In my hotel here, there is a clear distinction regarding supervisors. On the one hand there are the Indian and Arab supervisors, on the other hand we have the European and American supervisors. After a couple of weeks here in Dubai, I have noticed that these 2 groups do not go well together. So far I have been here just over a month and already witnessed some strong arguments between both sides. The culture in both groups is the cause of the problems, especially the power distance dimension. The Netherlands and United States only score 40 on this dimension and India scores 77. Most Arab countries score even higher, 90+.

The reality is a very good reflection of the differences in power distance. The Arab and Indian supervisors are very strict with following rules. They will not allow you to bend any rules, even if the situation might ask for this. […] The American and European supervisors are the exact opposite of this. They are very flexible in attending to unorthodox guest needs and will bend rules if this will accomplish a greater good. […]

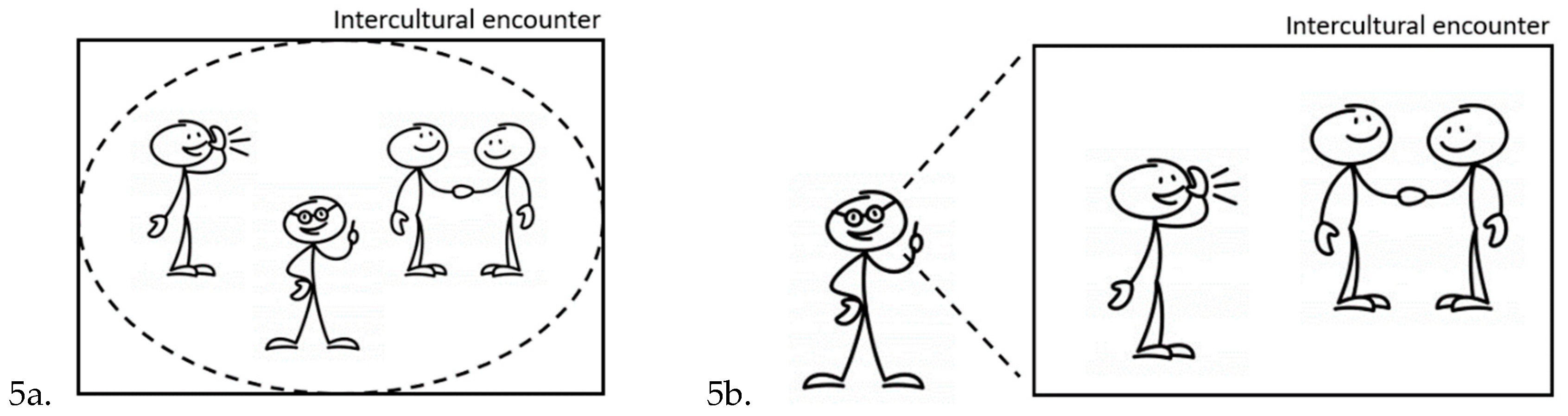

This suggests that the use of I-words marks a different approach of the student blogger to the intercultural situation, distinguishing between a more open, curious and involved stance (many I-words, as depicted in

Figure 5a) and a more distant or external stance (little or no I-words, as represented in

Figure 5b).

This more internal (involved) versus more external (distant) viewpoint is further continued and confirmed in these blogs, when – after having described the experience − the author tries to provide an explanation for the intercultural differences. In (7), the more involved student-blogger continues to take herself as a point of reference (I am Brazilian), when comparing Paris’ history of multiculturalism with a feeling of home and respect. The author of example (8), however, mainly refers to theories and models that offer him tools to categorize cultures and explain differences (in this case Hofstede’s power distance dimension).

The examples above show that the impact of the use of I-words on the perceived level of ICC is quite straightforward: the I-perspective links to more openness and involvement. At word-level, however, we did not find major differences in the type of I-words used in both sub-corpora (being I, my, me, myself and mine), nor in their relative frequency of use (I being the most frequent and mine being the least frequent). It should be noted, though, that we did observe lexical differences between both sub-corpora in the verbs following the subject pronoun ‘I’.

First of all, it came to our attention that the high-ICC blog corpus displays a greater variety of verbs following ‘I’, despite its smaller size (146,945 words (high) versus 269,583 words (low)): The type/token ratio (calculated as the number of different verbal lexemes following ‘I’, divided by the total number of ‘I + verb’-combinations) was 0.59 in the high-ICC corpus versus 0.56 in the low-ICC corpus. Furthermore, when we compare the relative frequency of the different ‘I + verb’-combinations between both corpora (

Table 4), lexical verb forms referring to cognitive acts such as

noticed, found, thought, decided, realized, felt, understand, looked, explained are significantly more frequent in the high-scoring corpus; whereas the only significant, more frequent combination in the low-scoring corpus is ‘I + say’.

Although we were not able to perform a more in-depth analysis for each of these verbs, we did see in examples such as (6) that the first person singular ‘I’ (highlighting personal focus) and the cognitive perception verbs such as notice or realize (pointing at introspection and reflection) seem to reinforce each other, enhancing the impression of a highly engaged, thoughtful and open-minded author, who is willing to revise certain knowledge or assumptions in the light of new events. In (6), the author even explicitly acknowledges learning from the experience.

- (6)

-

The Spanish are known for their lay-back-attitude, no hurry and their ‘mañana, mañana’. But is this vision we have on the Spanish culture also true at work? My experience after working in Moments for 2 months, I noticed that the Spanish culture outside of work is very different from the working atmosphere. […] What I immediately noticed was that everything is so well organised that an uncertainty is almost impossible to happen. Mise-en-place is always well done and perfectly on time. At 13.00 you have to be there, if not the manager comes to you and makes sure this never happens again. Before we go home we have to have done everything for the day after. It is way more organized than in the Netherlands. I have to admit that this is very new to me, but I learn a lot from it!

I also noticed that when something unexpected happens chaos and stress comes around. My colleagues are not used to stress and chaos at work, so communication fails during situations like this. In the Netherlands we learn to handle stress so I realized that is an advantage as well. I think that I can learn a lot from their organizational skills, but I can definitely learn them something about how to handle stress.

The above findings, regarding the frequent use of cognition verbs after ‘I’ fit in seamlessly with the result of the t-test for two of the dictionaries related to analytical thinking: Insight words and quantifiers. These results are elaborated upon in the next two sections.

3.3.2. Insight Words

We just saw how cognitive verbs frequently co-occur with the subject pronoun ‘I’, both implying a higher degree of involvement and introspection on behalf of the author. These cognitive verbs, such as think, realize, understand, perceive, notice, reflect, etc., typically belong to Pennebaker’s dictionary of insight words. This list also includes verbs like wonder, relate, refer, nouns like reason, solution or thought, and even adjectives like memorable and reasonable, which all refer in one way or another to steps in the mental process of acquiring insight. The fact that we found a statistically significant difference for the frequency of insight words between our two sub-corpora is therefore in line with our expectations.

In example (7), the student describes the personal impact of the Buddhist ritual of giving alms. The elaborate description (13 sentences) is written from an I-perspective and includes several perception verbs (‘see’) and expressions that explicitly refer to the cognitive process going on inside the author’s head (e.g., ‘I was surprised’, ‘Wondering what this was about’ or ‘I tried to find more information’). As such, the intercultural experience is depicted as an internalized event, which required perceptual and mental processing, in order to come to an understanding (evidenced by the repeated use of ‘understood’ by the end of the text) of the course of events.

- (7)

If you have ever been to Thailand, you must have seen a monk in an orange, red or brown robe and a shaved head. Monks are called Bhikkhus in Thailand and their religion is Buddhism. Living behind a temple I see them quite often. One early morning, when I was out to get some groceries I saw a young woman offering food to a monk. The monk was walking down the main street in Khao Lak when the woman held up a small plastic bag containing food. The monk stopped in front of her and opened his alms bowel and the women carefully placed her bag in the bowl. Then, the woman took of her shoes and kneeled down in the middle of the street, folding her hands to a “wai”, she pressed her palms together and formed a slight bow in a prayer-like fashion. Meanwhile the monk started praying to her. I was surprised when that happened, you would expect such scenes in a church, but not in the middle of the street. However, obviously I was the only one, it seemed to be normal to all the Thai people who surrounded that couple. They showed respect to the monk, but there was obviously nothing unusual about it. Even cars stopped and the drivers waited patiently for the monk to finish his prayer. When the monk completed his recite, he continued walking and the woman put on her shoes and left the street. Everybody came back into action, continuing what they were doing before. Wondering what this was about, I asked a colleague at the hotel. The physician has told me before that he was a Buddhist, so I asked him. He explained me the so-called “giving of alms” ceremony. He got very excited about my interest and encouraged me to research about spiritual acts that belong to the Buddhism. I tried to find more information about the “alms giving” and understood that it is not bound to specific days but can be held anywhere and anytime. It is a way to show respect to the monks and to Buddhism in general. Not only Buddhists undergo that ceremony, it is open to anybody. I also understood, that the local monks depend on these gifts, because they have no other income. Even though they would never beg for it. […] I have to admit, I am curious and decided to try it myself, one day. […]

Looking more closely at the word-level (

Table 5), it appears that words referring to a phase in the analytical thinking process (e.g.,

feel, felt, learned, noticed, thought, explained, explains, decided, concluding) are significantly more frequent in the high-ICC corpus than in the low-ICC corpus; This also goes for words like

curious and

remember, which respectively refer to a state-of-mind or a way of processing events, relating them to former experiences.

The act of remembering also relates to the analytical thinking process, as shown by example (8), in which a more involved author uses I-words and several cognitive and other perception verbs (realize, find, learn, notice, look, know, see, hear) that help her recall a certain event.

- (8)

'Time will fly by' is what they said when we were leaving for our internship all across the world; and they were right. I’m living for almost 3 months in the States now and I realize that I only have 3 months left. I’m working in the housekeeping department and one major thing that I face every day are the housekeeping ladies who all have a different background. […] I work with a lot of ladies that are born in different countries like Honduras, Peru, Portugal, India, Afghanistan , Bolivia, El Salvador, Guatemala and the Dominican Republic. I find it very special to work with so many different cultures and I’m learning a lot from it. Even at moments when there are some heated discussions between the ladies […]. Another big challenge is the fact that I need to talk to a lot of Spanish with them to communicate. Something else that I noticed in the beginning of my internship is the fact that one of the housemen is praying every day at 5 PM in the back of the laundry loft. Eastward, in the direction of Mecca. I didn’t know this at first so in the beginning I was looking for him and when I couldn’t find him, I called him on his phone. After a few times I heard some music in the back of the laundry, and there I saw him praying. I remember that I felt very uncomfortable and surprised. […].

Two insight words turned out more frequent in the low-scoring corpus than in the high-scoring corpus: becoming and referendum. In the case of referendum (9), we suspect that the specific time frame of our blog corpus, which coincided with Brexit and the Catalan fight for independence, can account for its higher frequency. Furthermore, the blogs about these news topics were usually limited to a description of the context, historical background or parties involved, and often lacked a personal reflection on the intercultural differences. In these instances, the specific topic choice – more distant to a student’s personal life – most probably explains why these blogs ended up in the low-ICC corpus.

- (9)

Who hasn’t heard about the situation in Barcelona? I think most of you guys have heard or seen something about it. Mostly in Barcelona and Madrid are big protests about the referendum which was hold on the 1st of October. There is still a lot going on in Barcelona, they will not rest until it is clear what is going to happen. But how did this all happen and why do they want to be independent? In the past, Spain used to be a monocracy. It was ruled by the well-known dictator Francisco Franco. […] At the battle of Ebro in 1938 he took control of the region, it cost 3,500 people their lives. In 1977 democracy returned to Spain. As from 2010, calls for independence were growing. The government reacted to this with a new law, article 155. It made a referendum illegal. This action caused a lot of incomprehension. Especially because Spain is a democracy, voices are there to be heard. In the past few years, the pressure of a referendum of independence of Catalonia started to grow. The president of Catalonia, Carles Puidgemont, was backed by a big party to hold a referendum. In September 2017, the majority agreed to hold a referendum. […]

3.3.3. Quantifiers

Quantifiers were the third dictionary for which we observed a significant difference in frequency between the high-ICC and low-ICC blogs; Yet, this time, to the disadvantage of the high-scoring blogs, where this word category was less commonly used. This finding runs counter to what we initially expected, namely that quantifiers − in the same way as the insight words and the other dictionaries linked to analytical thinking − would be more frequent in the corpus of blogs scoring high on ICC. According to Pennebaker (2011: 80), the frequent use of quantifiers would be symptomatic of an analytical thinking/writing style. So how can we explain their more prominent presence in the low-scoring blog corpus?

At first sight there is hardly any difference in the type of quantifiers used in both corpora: if we rank them from more to less frequent, the top 10 of most frequently used quantifiers is more or less the same: all, more, lot, some, most, every, many, much, another, few in the low-ICC corpus; with each instead of another in the high-ICC corpus. However, a more thorough contextual analysis shows that quantifiers implying a more thoughtful attitude of the student blogger, nuance and tempering (e.g., few, bit, part, several, somewhat, scarce, single, either, any, each) are more commonly used in the high-ICC corpus; whereas quantifiers indicating inclusion, propagation and exaggeration (e.g., all, more, lot, most, every, many, much, another, whole, total, entire, majority, plenty, bunch, double) seem to thrive in the low-ICC corpus.

The quantifiers used in blog excerpts (10) and (11) reveal important information on the author’s view on cultural differences, going from very prototypical/over-generalizing (‘very’ and ‘exact’, in (5)) to more nuanced (‘not everyone’, ‘almost always’ and ‘some’, in (6)):

- (10)

The Arab and Indian supervisors are very strict with following rules. […] The American and European supervisors are the exact opposite of this.

- (11)

Let me get back to the story I started off with. Not everyone arrived at the restaurant after one hour of waiting. We already started with the appetizers when the remaining colleagues arrived. They didn’t apologize. Nevertheless, we had a great evening. The fact that Arubans always take their time for everything, doesn't mean they don't do their job properly. They are almost always on time –of course there are some exceptions.

In example (12), the use of the quantifier somewhat adds nuance to the Hofstede model (Hofstede Hofstede & Minkov, 2010). Together with the modal verb would, and indefinites like sometimes and something, the quantifier somewhat is used by the author to mitigate his statements. It is a sign of prudence, self-relativism and reflection; features we generally identify with an interculturally competent speaker/writer. On the other hand, the quantifier whole, implying inclusion and comprehensiveness, is used by the author of example (13) to reinforce his claim that the experience of a sports game in the U.S. is completely different than in Europe. The more polarizing and generalized discourse of this author may have contributed to his blog getting a lower ICC score.

- (12)

We have a great multicultural team on the work floor, coming from all around the world, so the only thing you would like to do after work is hanging around with this bunch of people and getting to know each other better. On top of that, something people do not realize sometimes is that eating or better said ‘sharing food’ is actually one of the most social activities you could think of. But how is that possible at 5am? Well, in Hong Kong, it is possible because of one reason: here they have real hard working people who open their restaurants and bars 24 hours a day, 7 days a week. It is a somewhat restrained society, Hofstede would say. They don’t put much emphasis on leisure time because of the feeling that indulging themselves is somewhat wrong.

- (13)

Sports games in the States are again on a whole other level than the European ones. You don’t even have to know anything about the specific sport to be able to feel as a part of the team. The whole experience of the actual game, the cheerleading and the food are seriously on the next level. The person next to you becomes your best friends within the first 10 seconds of the game. It doesn’t matter if you have been a fan for 20 years or if it is your first game ever, you are part of the team. It doesn’t get more collectivistic than this.

Zooming in on the word level, a t-test comparing the relative frequencies of the individual quantifiers in both sub-corpora renders a significant result for the quantifiers

each, few and

bit in the high-scoring corpus, and the quantifiers

lot, every, less, group, extra, majority, lots and

percentage in the low-scoring blog corpus, as can be seen in

Table 6.

The quantifiers in this list with a more prominent presence in the low-ICC corpus generally comply with the idea stated above: They indicate a large quantity (group, majority, lot(s)), a set of categories (group, percentage) or have an superlative, intensifying and cumulative effect (extra, every, less). In example (14), the quantifiers most, lot, whole and every are used to reinforce the author’s opinion that Americans are treated too generously after a complaint. By putting all Americans in the same category, without looking at the underlying cause of this phenomenon, the blog lacks open-mindedness, curiosity and reflection and therefore reflects a lower level of ICC.

- (14)

In the Netherlands, it barely happens that when someone has a complaint, they actually get something for it. Most of the times, we have to do it with just a sorry. Which is in most of the situation completely normal, because something happened that we just cannot control. A lot of guests, as I noticed mainly American guests, cannot cope with this. When there goes something wrong, they will let you know for sure. Most of the them let every associate they face know about the problem. They only do this because they want free stuff: a free breakfast, ‘points for the inconvenience’ or a whole comped night. Of course, when your room keys are not working, that is an inconvenience, but a free night because you had to step by at the front desk one more time? The problem is that they can do this is because they know that the associate that is helping them with their problem, is most of the time very generous. And in my opinion, way too generous. This turns about to be 'American'. The person who screams the loudest, gets the most for free. This is weird, but unfortunately, it is a way of living here.

Only three quantifiers appear to be significantly more used in the high-ICC corpus: each, few and bit. Whereas few and bit have a more tempering and nuancing meaning in line with our claim based on the exploratory contextual analysis, we need to look deeper into the specific use of the inclusive quantifier each to see whether it supports our hypothesis. It appears that each is commonly used in the high scoring blogs as part of the compound ‘each other’, implying reciprocity and mutual respect. Therefore, it can be seen as indicative for a culturally sensitive author, as in blog excerpt (15), where the author actively tries to explain the origin of French politeness. Also note the frequent use of I-words, insight words (wonder, understand, explain, interpret) and other mitigating contextual elements like sometimes even, not really, etc. that contribute to this higher level of perceived ICC.

- (15)

Not many Dutch people are surprised when they receive feedback in a direct or even harsh way; this is our communication style and helps us to improve ourselves and our work. However, I didn’t think I wouldn’t receive any feedback at all when I asked for it. What about this? […] When my colleague and I were finished for the day, I was wondering what I could do to make everything work better the next day. Therefore, I easily asked my colleague if she had any tips for me, expecting to hear some things I could work on. However, she answered my question in an incredibly sweet way and said: “Don’t worry, you are here to learn anyway.” I did not really understand this reaction, because it wasn’t very useful, so I thanked her in the first instance and let it sink for a while. But now I understand, let me explain it. During the feudal system, a lot of Europeans lived as a serf, under the protection of their Lord who fed them. In return, the serfs yield a part of their harvest to the Lord and must be grateful for his protection. However, in the Netherlands prevailed a civilian culture more than a century before the French Revolution. The Dutch civilians were proud to be independent and equal, which resulted in more direct manners. Currently, boundaries of politeness are continually moving further, which makes our communication style in the Netherlands very direct. For people who are not used to this, it is interpreted as impolite and sometimes even unintelligent. In France, it serves people to respect each other and formulate their messages in an indirect and tactical way, based on logic and feeling for hierarchy, hierarchy that is not normal for Dutch people. When we look at power distance, it appears that France scores 68 points which, in comparison to the Netherlands with a score of 38, is a high score. This reveals why my colleague didn’t give me any straight-forward feedback but reacted so kindly and respectful instead.

These results allow us to further nuance Pennebaker’s claim by stating that not only the gross frequency of quantifiers is an indicator of reflection or analytical thinking. In the context of ICC, it is certainly also useful to examine which kind of quantifier is used to further determine the specific tone of the blog: Do the quantifiers steer the reader to a black-and-white, overgeneralizing interpretation, or do they help to put things in perspective, by adding a touch of nuance? This brings us to our discussion and conclusions.

4. Discussion and Conclusions

The goal of this study was to analyze the language use of students blogging about intercultural experiences, and see whether we could identify linguistic markers of ICC at the micro-textual or word level. Whereas in previous research, the assessment of reflective writing assignments in the context of language teaching and ICC was generally situated at a holistic, textual level, using frameworks such as Byram’s intercultural speaker model, we have shown that this macro-textual level of assessment can be enriched and deepened by adding a complementary step to the analysis at micro- or word level, with the help of Pennebaker’s LIWC framework. By adding a textual analysis to a holistic rubric, we intend to make the perceived level of ICC more tangible. By focusing on language use, we enable teachers to substantiate their holistic claims and help students become more nuanced, curious, reflective and open-minded writers who, consequently, develop their intercultural competences.

Our analysis of the student blogs provides support for Pennebaker’s claim that words are like fingerprints. After subdividing our blog corpus in three groups based on a holistic assessment of ICC (see appendix), we compared the language use in the high-ICC blogs with that in the low-ICC blogs. In order to bring more focus to our research, we initially focused on word categories that are characteristic of properties that can be linked to ICC and cultural sensitivity, such as openness, self-relativity, curiosity and reflection or analytical thinking. More specifically, we looked at the relative frequency of I-words, exclusives, negations, causal words, insight words, tentative words, certainty and quantifiers. Statistical comparisons between the high-ICC blogs and the low-ICC blogs revealed that more curious, open-minded and reflective bloggers tend to use significantly more I-words, more insight words and fewer quantifiers.

From these results we can conclude that our search for linguistic markers of ICC has been fruitful. With respect to the category of I-words, we have tried to demonstrate that students who are more involved and immersed in the cultural interplay and the intercultural experiences they have, use significantly more I-words. They more frequently describe their impression of the event and the impact it had on them. Moreover, we noticed that these student bloggers often use verbs pertaining to the category of insight words, such as think, realize, feel, understand, etc. In this way, they openly refer to the inner process of registering and analyzing the events. Lastly, the relative frequency of quantifiers was inversely related to the level of ICC: this category turned out to be less frequent in the high-scoring blog corpus. A further contextual analysis however showed that especially polarizing quantifiers were more frequent in the low-ICC corpus, highlighting the lack of analytical thinking and nuance, two features that contribute to a higher perceived level of ICC.

The outcomes of this exploratory study contribute to research within the domain of ICC in various ways. First and foremost, we have demonstrated that ICC is detectable in students' language use. Our study gives ICC ‘a face’, as it were, in students' reflective writing assignments. It helps to substantiate the often more subjective assessment of ICC based on holistic models such as those of Byram (1997) or Deardorff (2006), by linking ICC to concrete words and word patterns. We have been able to identify word categories, and even specific words, that correlate with high perceived levels of ICC. Secondly, this research offers some concrete tools to give the assessment of ICC in reflective writing assignments more depth and focus. It meets the needs of teachers who are looking for tools to discuss a complex concept such as ICC with their students, based on the experiences the students have described in reflective writing (Chan, Wong & Luo, 2020). Now we have identified some linguistic markers for ICC, it becomes easier to pinpoint those areas of a text that need extra attention. In a general sense, but also specifically in the context of foreign language learning (Elola & Oskoz, 2008) or a virtual exchange setting (Belz, 2003), our text-analytical approach to the assessment of ICC will help teachers to formulate more accurate and targeted feedback for the student that they can consequently link to their overall assessment of the level of ICC of a specific blog.

By means of illustration, let’s revisit example (5) (copied in (16). This example was assigned to the low-ICC corpus based on a macro-textual, holistic assessment. And this is confirmed when we zoom in on the micro-textual or word level: We see that the student blogger hardly uses I-words or insight words. At the same time, he does use quantifiers such as very to intensify his claim that managers can be put into boxes: the Indian and Arab supervisors being the exact opposite of the European and American ones.

- (16)

-

In my hotel here, there is a clear distinction regarding supervisors. On the one hand there are the Indian and Arab supervisors, on the other hand we have the European and American supervisors. After a couple of weeks here in Dubai, I have noticed that these 2 groups do not go well together. So far I have been here just over a month and already witnessed some strong arguments between both sides. The culture in both groups is the cause of the problems, especially the power distance dimension. The Netherlands and United States only score 40 on this dimension and India scores 77. Most Arab countries score even higher, 90+.

The reality is a very good reflection of the differences in power distance. The Arab and Indian supervisors are very strict with following rules. They will not allow you to bend any rules, even if the situation might ask for this. […] The American and European supervisors are the exact opposite of this. They are very flexible in attending to unorthodox guest needs and will bend rules if this will accomplish a greater good. […]

With the help of these linguistic markers, teachers can pinpoint certain areas of improvement in their feedback to students. More specifically, they can make the holistic claim of the blog lacking a personal perspective, in-depth reflection and nuance, more concrete by pointing at the lack of I-words, insight words and the frequent use of intensifying quantifiers. By stimulating students to pay attention to their usage of specific word categories, it may in fact be possible to influence their way of thinking about the intercultural experience as well (Pennebaker, 2011: 13-15).

All in all, the outcomes of this study are promising. However, there are also some limitations we need to address. First of all, the initial categorization of the blogs into three groups (blogs with a high, low or intermediate perceived level of ICC) is based on a rubric that was designed for a specific educational context. Changing its content or the weight attached to each of its components could affect the composition of the sub-corpora and therefore the outcomes of this study. For example, the fact that descriptions of personal experiences were valued more than generic descriptions of cultural differences reflects the nature of the assignment and the accompanying rubric, rather than ICC as such.

We also need to interpret the quantitative outcomes of this study with caution. A significant difference in frequency of use in itself has little explanatory value. It can merely be seen as a symptom of a particular writing behavior and, consequently, mindset or attitude of the author. This is also why we refer to the categories of I-words, insight words and quantifiers as ‘linguistic markers’ for ICC. They ‘mark’ part of the students’ text and should thereby attract the attention of the reader, teacher or assessor to further explore their context. Most of the I-words, insight words and quantifiers we discussed in the examples above occur in both sub-corpora. Only certain lexical combinations or lexemes appear to be relatively more frequent in one of the two corpora. A more in-depth, qualitative analysis of these occurrences has shown that a contextual analysis is needed before we can draw conclusions about the intercultural competencies of the student-blogger.

This leads us to the third limitation: We were not able to perform a thorough contextual analysis for all words that showed significant frequency differences, and in some cases, the contextual analysis did not help us in interpreting or contextualizing the statistical result. Fortunately, the size of the corpus offers sufficient possibilities to deepen the analyses further in the future.

A fourth limitation has to do with the specific population of this study. Our student bloggers had no linguistic background and most of them were non-native speakers of English. Their proficiency level of English might therefore have had an effect on their level of cultural reflection and nuance in the blogs (Elola & Oskoz, 2008).

Finally, this study was limited to identifying linguistic markers for ICC based on a text-analytical approach. We did not look into the further implications of our findings on the assessment and feedback process, and on the students’ development of ICC. It seems like a logical next step to investigate the effectiveness of the different ways of providing feedback for developing ICC, based on these linguistic markers. This could be done by means of an experiment or an intervention study in which we compare a control group to an experimental group of students who have received specific feedback to stimulate the use of certain words or constructions. The rubric we developed can then be used to determine whether this type of feedback also leads to better blogs, i.e., blogs scoring higher on ICC.

In conclusion, we were able to demonstrate how the analysis of students’ language use in reflective blogs can help to make a complex competence such as ICC more tangible by identifying specific linguistic markers that teachers can use to monitor their students’ intercultural development. However, the way in which these cues are best used to bring more focus and depth to the feedback process is food for future research.

Appendix 1 – The Rubric Used for the Holistic Analysis of ICC

References

- Allport, G.W. The Nature of Prejudice; Addison-Wesley: Reading, MA, USA, 1954. [Google Scholar]

- Alred, G.; Byram, M.; Fleming, M. (Eds.) Intercultural Experience and Education; Multilingual Matters: Clevedon, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Bartlett-Bragg, A. An investigation into adult learners’ experiences of developing distributed learning networks with self-publishing technologies; University of Technology: Sydney, 2013.

- Belz, J.A. Social dimensions of telecollaborative FL study. Language Learning & Technology 2002, 6, 60–81. [Google Scholar]

- Belz, J.A. Linguistic perspectives on the development of intercultural competence in telecollaboration. Language, Learning & Technology 2003, 7, 68–93. [Google Scholar]

- Boonen, J.; Hoefnagels, A.; Pluymaekers, M. The Development of Intercultural Competencies During a Stay Abroad: Does Cultural Distance Matter. In The Three Cs of Higher Education: Competition, Collaboration and Complementarity; MO Pritchard, R., et al., Eds.; CEU Press: Budapest, 2019; pp. 185–204. [Google Scholar]

- Brown, L. The Transformative Power of the International Sojourn. An Ethnographic Study of the International Student Experience. Annals of tourism research 2009, 36, 502–521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Byram, M. Teaching and assessing intercultural communicative competence; Multilingual Matters: Clevedon, UK, 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Carney, N. (2007). Language study through blog exchanges. Paper presented at the Wireless Ready Symposium: Podcasting Education and Mobile Assisted Language Learning, Nagoya, Japan.

- Chan, C.K.Y.; Wong, H.Y.; Luo, J. An exploratory study on assessing reflective writing from teachers’ perspectives. Higher Education Research & Development 2020, 40, 706–720. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, W.-C. Actual and preferred teacher feedback on student blog technology. Australasian Journal of Educational Technology 2014, 30, 402–414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coleman, JA. Evolving intercultural perceptions among university language learners in Europe In, M. Byram & M. Fleming (Eds.), Language learning in intercultural perspective: Approaches through drama and ethnography; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, 1998; pp. 45–75. [Google Scholar]

- Crossman, J.E.; Clark, M. International experience and graduate employability: Stakeholder perceptions on the connection. Higher Education 2010, 59, 599–613. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deardorff, D. Identification and Assessment of Intercultural Competence as a Student Outcome of Internationalisation. Journal of Studies in International Education 2006, 10, 241–266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dervin, F. Métamorphoses identitaires en situation de mobilité; Presses Universitaires de Turku: Turku, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Dudău, D.P.; Sava, F.A. Performing Multilingual Analysis With Linguistic Inquiry and Word Count 2015 (LIWC2015). An Equivalence Study of Four Languages. Frontiers in Psychology 2021, 12, 570568. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Elola, I.; Oskoz, A. Blogging: Fostering Intercultural Competence Development in Foreign Language and Study Abroad Contexts. Foreign Language Annals 2008, 41, 454–477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Engle, R.L.; Crowne, K.A. The impact of international experience on cultural intelligence: An application of contact theory in a structured short-term programme. Human Resource Development International 2014, 17, 30–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gregersen-Hermans, J. The impact of an international university environment on students’ intercultural competence development (Doctoral dissertation). (2016). Retrieved from https://www.researchgate.net/publication/313388295_Intercultural_Competence_Development_in_Higher_Education.

- Hofstede, G.; Hofstede, G.J.; Minkov, M. Cultures and Organisations: Software of the Mind. McGraw-Hill: New York, 2010.

- Hoefnagels, A.; Schoenmakers, S. Developing the intercultural competence of 21st century learners with blogging during a work placement abroad In, J.A. Oskam, D.M. Dekker, & K. Wiegerink (Eds). Innovation in Hospitality Education; Springer: Cham, 2018; pp. 123–141. [Google Scholar]

- Holmes, P.; O’Neill, G. Developing and evaluating intercultural competence: Ethnographies of intercultural encounters. International Journal of Intercultural Relations 2012, 36, 707–718. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hourigan, T.; Murray, L. Using blogs to help language students to develop reflective learning strategies: Towards a pedagogical framework. Australasian Journal of Educational Technology 2010, 26, 209–225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jackson, J. Intercultural journeys: From study to residence abroad; Palgrave Macmillan: Basingstoke, Hampshire, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Jackson, J. Becoming interculturally competent: Theory to practice in international education. International Journal of Intercultural Relations 2015, 48, 91–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jaidev, R. How pedagogical blogging helps prepare students for intercultural communication in the global workplace. Language and Intercultural Communication, 2014; 14, 132–139. [Google Scholar]

- Kruse, J.; Brubaker, C. Successful Study Abroad: Tips for Student Preparation, Immersion, and Postprocessing. Die Unterrichtspraxis / Teaching German 2007, 40, 147–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leask, B. Internationalising the Curriculum; Abingdon: Routledge, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Lee, L. Blogging: Promoting learner autonomy and intercultural competence through study abroad. Language Learning & Technology 2011, 15, 87–109. [Google Scholar]

- Lee. L. Engaging Study Abroad Students in Intercultural Learning Through Blogging and Ethnographic Interviews. Foreign Language Annals 2012, 45, 7–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leong, C.-H. Predictive validity of the Multicultural Personality Questionnaire: A longitudinal study on the sociopsychological adaptation of Asian undergraduates who took part in a study-abroad program. International Journal of Intercultural Relations 2007, 31, 545–559. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liaw, M.-L. E-learning and the development of intercultural competence. Language Learning & Technology 2006, 10, 49–64. [Google Scholar]

- Lijffijt, J.; Nevalainen, T.; Saïly, T.; Papapetrou, P.; Puolamäki, K.; Mannila, H. Significance testing of word frequencies in corpora. Digital Scholarship in the Humanities 2016, 31, 374–397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lomicka, L. Understanding the other: Virtual exchange and CMC. Calling on CALL: From theory and research to new directions in foreign language teaching 2006, 5, 211–236. [Google Scholar]

- Lucas, P.; Fleming, J. Reflection in sport and recreation cooperative education: Journals or blogs? Asia-Pacific Journal of Cooperative Education 2012, 13, 55–64. [Google Scholar]

- Marcotte, C.; Desroches, J.; Poupart, I. Preparing internationally minded business graduates: The role of international mobility programs. International Journal of Intercultural Relations 2007, 31, 655–668. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Messelink, H.E.; Van Maele, J.; Spencer-Oatey, H. Intercultural competencies: What students in study and placement mobility should be learning. Intercultural Education 2015, 26, 62–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Müller-Hartmann A Learning how to teach intercultural communicative competence via telecollaboration: A model for language teaching education In, J. Belz & S. Thorne (Eds.), Internet-mediated intercultural foreign language education (pp. 63-86). Boston, MA: Thomson Heinle. (2006).

- O’Connor, C.; Joffe, H. Intercoder Reliability in Qualitative Research: Debates and Practical Guidelines. International Journal of Qualitative Methods. ( 2020. [CrossRef]

- O'Dowd, R. Understanding the "other side": A qualitative analysis of intercultural learning in networked exchanges. Language Learning & Technology 2003, 7, 118–144. [Google Scholar]

- O’Dowd, R. The use of videoconferencing e-mail as mediators of intercultural student ethnography In, J. Belz Q S. Thorne (Eds.), Internet-mediated intercultural foreign language education; Thomson Heinle: Boston, MA, 2006; pp. 86–120. [Google Scholar]

- Osman, G.; Koh, J.H.L. Understanding management students' reflective practice through blogging. The Internet and Higher Education 2013, 16, 23–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pennebaker, J.W. The secret life of pronouns; Bloomsbury Press: New York/London, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Pennebaker, J.W.; Booth, R.J.; Boyd, R.L.; Francis, M.E. Linguistic Inquiry and Word Count: LIWC2015; Pennebaker Conglomerates: Austin, TX, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Pinilla, S.; Weckbach, L.T.; Alig, S.K.; Bauer, H.; Noerenberg, D.; Singer, K.; Tiedt, S. Blogging Medical Students: A Qualitative Analysis. GMS Zeitschrift für Medizinische Ausbilding 2013, 30. [Google Scholar]

- Pinto, D. Interculturele communicatie; Bohn Stafleu van Loghum: Houten/Zaventem, 1990. [Google Scholar]

- Ramlal, A.; Augustin, D.S. Engaging students in reflective writing: An action research project. Educational Action Research 2020, 28, 518–533. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salisbury, M.H.; An, B.P.; Pascarella, E.T. The effect of study abroad on intercultural competence among undergraduate college students. Journal of Student Affairs Research and Practice 2013, 50, 1–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schartner, A. The effect of study abroad on intercultural competence: A longitudinal case study of international postgraduate students at a British university. Journal of Multilingual and Multicultural Development 2016, 37, 402–418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schneider, J.; von der Emde, S. Conflicts in cyberspace: From communication breakdown to intercultural dialogue in online collaborations In Internet-mediated intercultural foreign language education; J. Belz & S. Thome (Eds.); Thomson Heinle: Boston, MA, 2006; pp. 178–206. [Google Scholar]

- Shaules, J. Deep culture: The hidden challenges of global living; Multilingual Matters: Clevedon, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Strampel, K.E.; Oliver, R.G. We've Thrown Away The Pens, But Are They Learning? Using Blogs In Higher Education. Proceedings of ASCILITE. (pp. 992-1001); ASCILITE: Melbourne; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Strong, D. Discourse of bi-national exchange students: Constructing dual identifications In, Analysing the consequences of academic mobility and migration; F. Dervin (Ed.); Cambridge University Press: Newcastle upon Tyne, 2011; pp. 51–66. [Google Scholar]

- Vande Berg, M. Intervening in student learning abroad: A research-based inquiry. Intercultural Education 2009, 20, 15–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van der Poel, M.H.; van der Werf, E. Professional development of teaching staff for the international higher education environment. In Proceedings: Cross-cultural business conference 2014; M. Überwimmer, S. Wiesinger, M. Gaisch, Ed.; Shaker Verlag: Aachen, Germany, 2014; pp. 231–241. [Google Scholar]

| 1 |

It should be noted that English is not the native language of the majority of these students. |

| 2 |

T is the calculated difference represented in units of standard error. The greater the magnitude of T, the greater the evidence against the null hypothesis, viz. the assumption that there is no difference in language use between blogs scoring high vs. low in perceived level of ICC. |

| 3 |

A p-value measures the probability of obtaining the observed results, assuming that the null hypothesis is true.

The lower the p-value, the greater the statistical significance of the observed difference. A p-value of 0.05 or lower is generally considered statistically significant, meaning that the null hypothesis can be rejected.

|

| 4 |

Short for ‘not significant’ = p-value above 0.05. |

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).