2. Finite Black Holes Inside an Infinite Black Hole

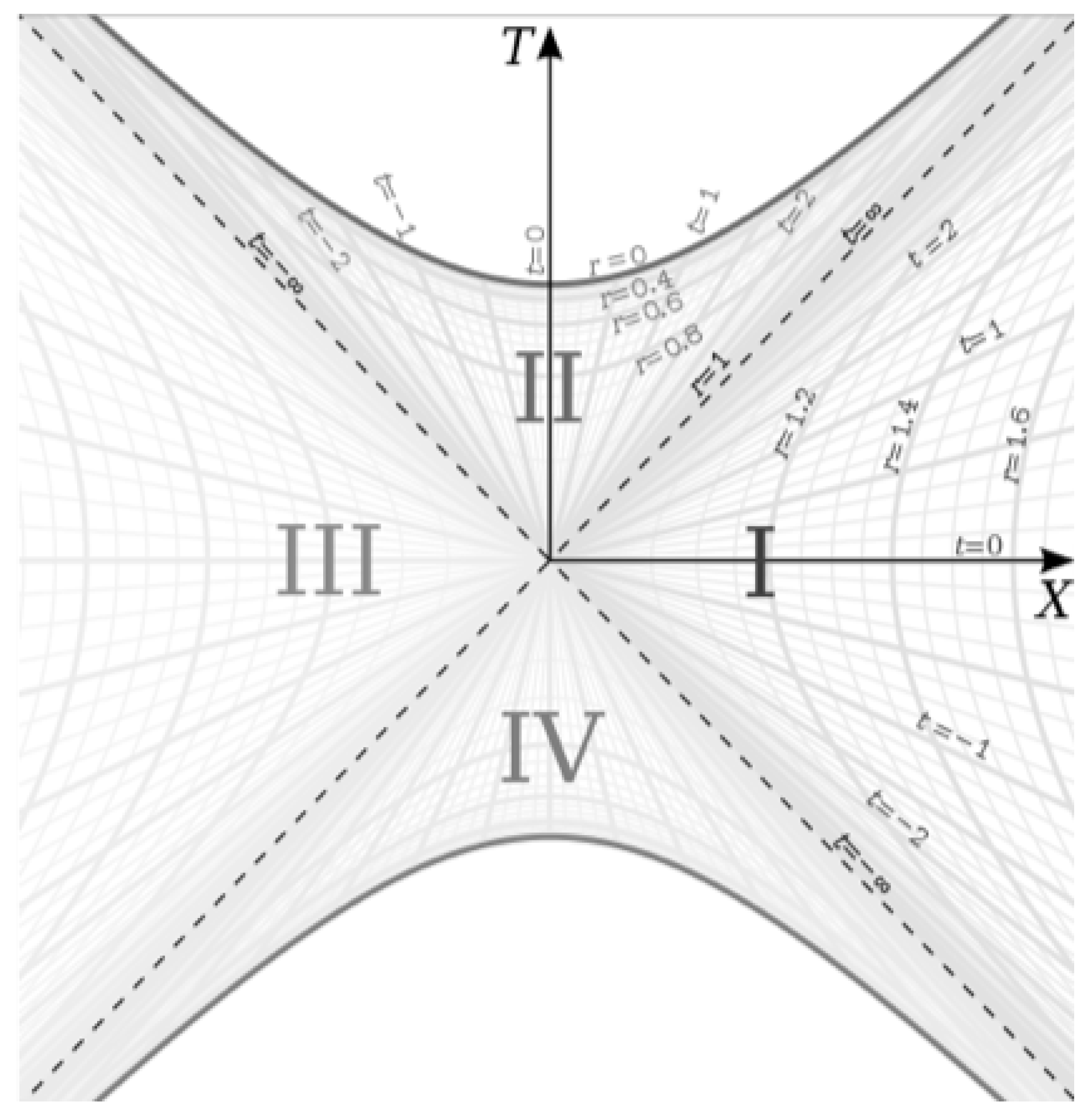

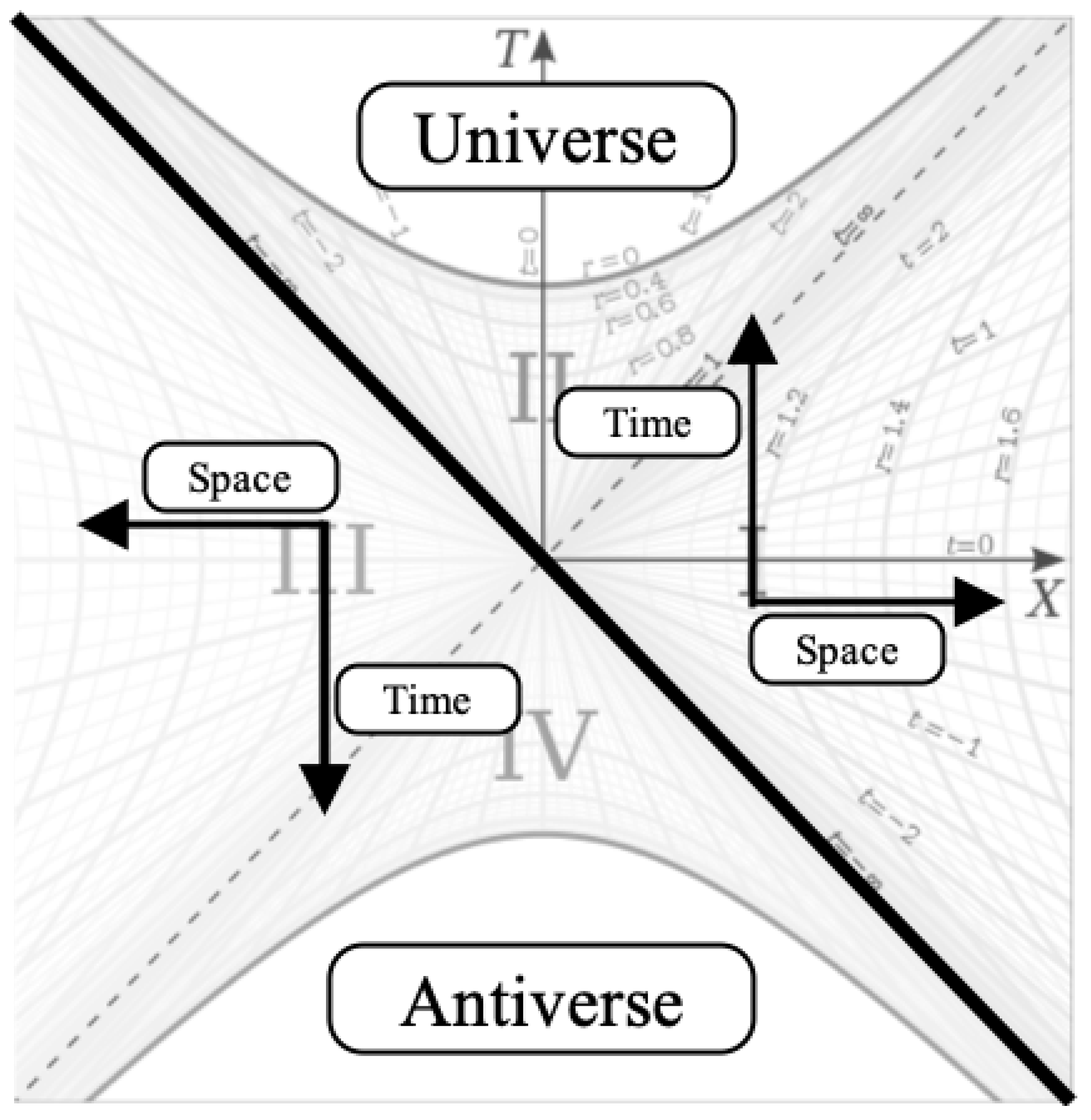

The interior region of the Schwarzschild metric (Region II in

Figure 1) is described by the Schwarzschild metric:

Equation

1 is the interior metric and for the rest of the paper it is important to remember that when discussing the interior metric,

t is the spacelike coordinate and r is the timelike coordinate.

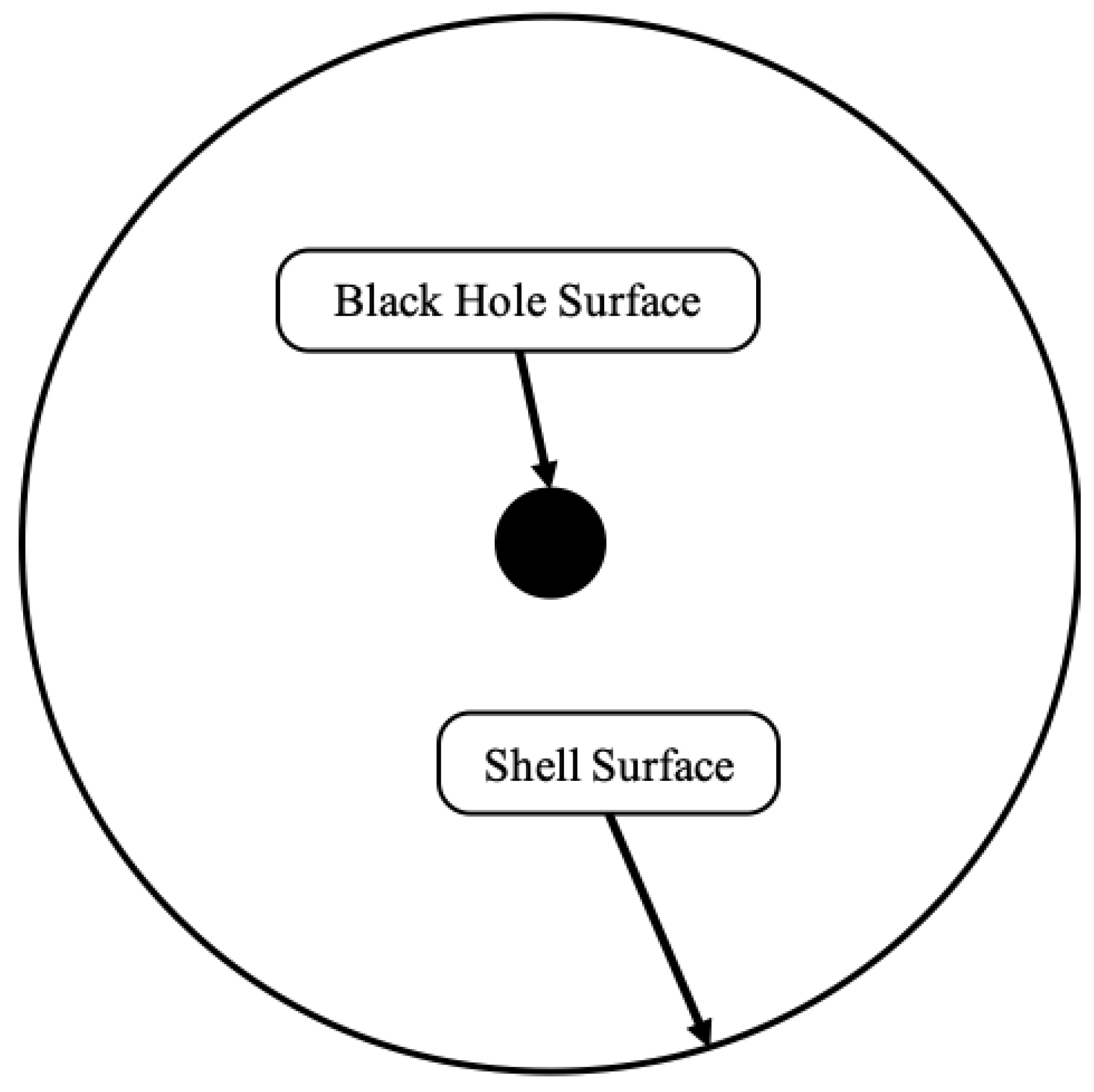

The interior metric describes the interior of a Black Hole. If we place a Black Hole inside the interior metric, the vacuum between the Black Hole and the surface of the shell of the interior metric is also a spherically symmetric vacuum. This can be trivially visualized in

Figure 2

We can see that the vacuum in

Figure 2 is spherically symmetric and therefore must also be described by the Schwarzschild metric.

The radial coordinate

r of the interior metric is timelike, so as

r goes from

u to 0, time moves forward. So the Black Hole at the center of

Figure 2 is at some

in the interior metric and moves toward

in that metric as time passes. A notable feature of the metric in equation

1 is the angular term

. This term is multiplied by

r which goes from

u to 0 as time passes. This means that as the Black Hole falls through time in this metric, it’s surface area will decrease proportionally to

r as a consequence of this angular term. At

, which is the curvature singularity of the metric, the Black Hole surface area will go to zero, and the Black Hole will no longer exist. It is as though the Black Hole gets squeezed out of existence at the singularity.

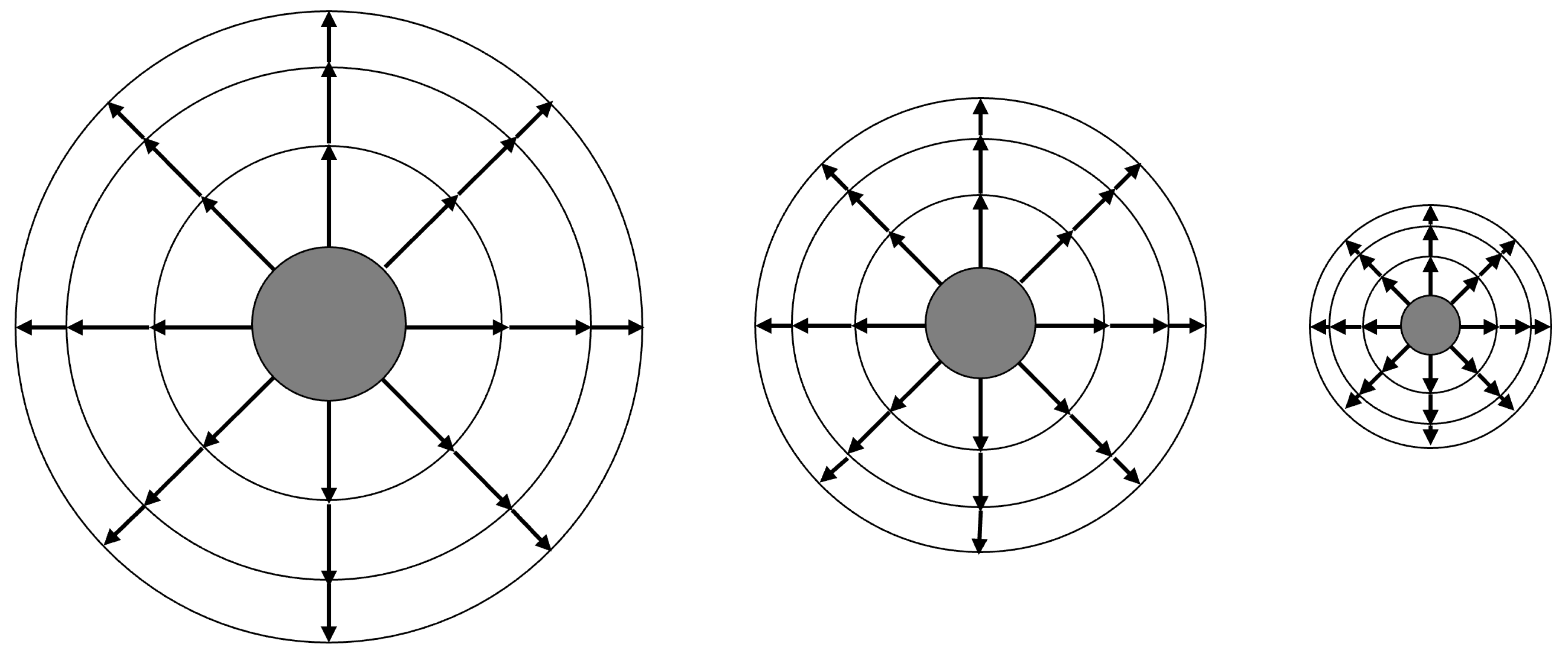

If we now imagine that the Black Hole is being orbited by some material, then the contraction of the

term will also cause those orbits to be squeezed closer to the surface of the Black Hole as time passes.

Figure 3 depicts the relative scale of the gravitational field around the Black Hole as it moves through time toward

in the interior metric.

According to the interior metric, the basis vectors get larger as r decreases, becoming infinite at . Therefore, the proper distance/time between t coordinates increases as the system falls to .

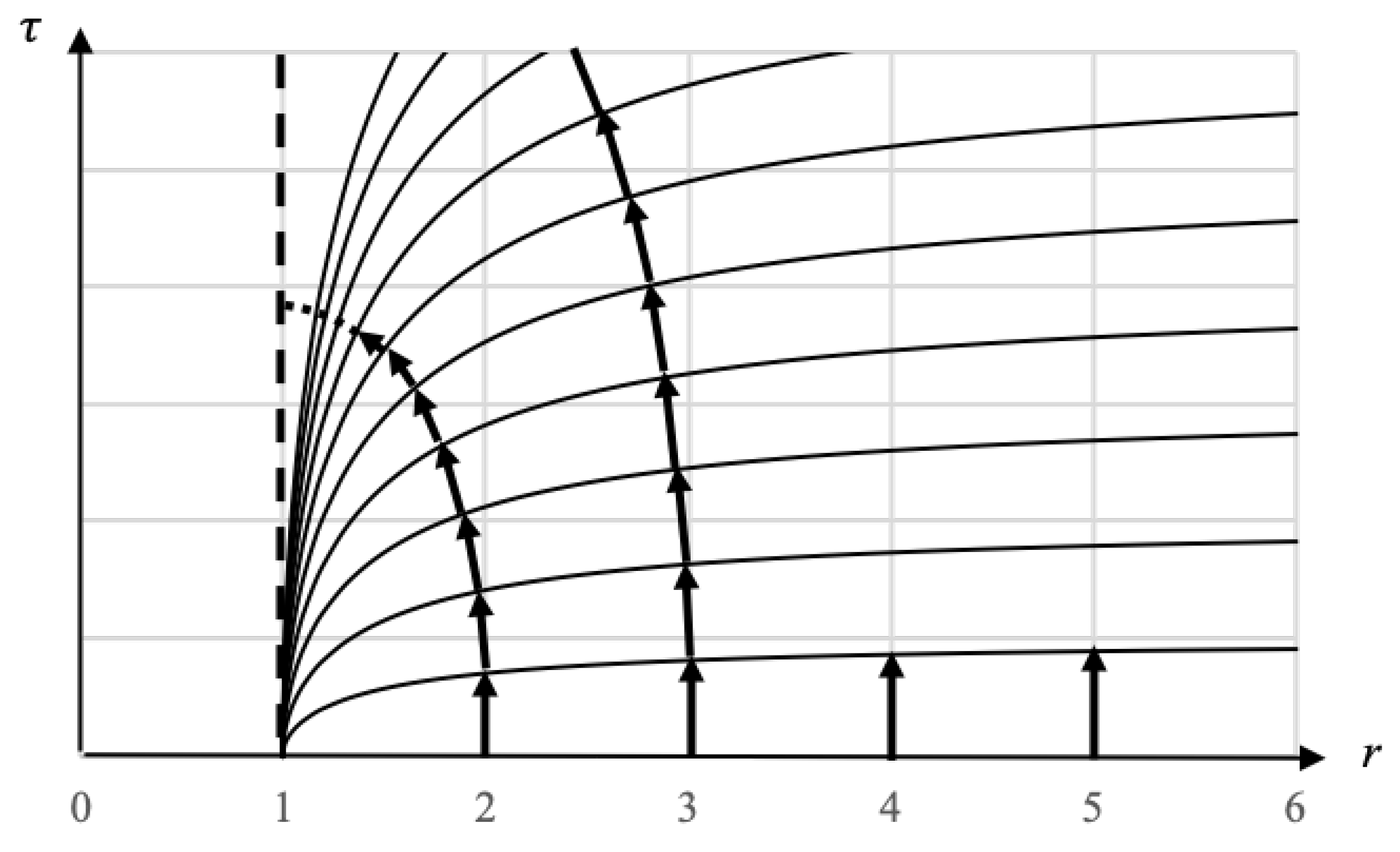

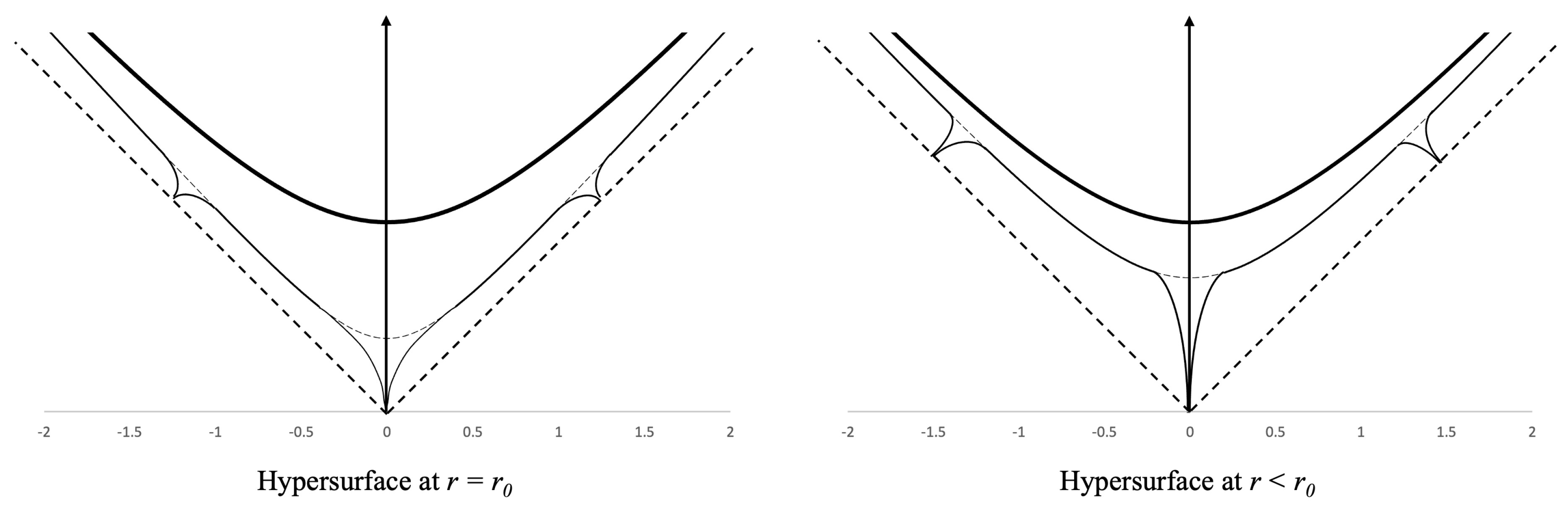

Consider

Figure 4 which depicts the curvature of the

t coordinates in the exterior metric near the surface of a Black Hole. The

t coordinate lines are the curved lines and they come from solving the metric for rest observers (

) and integrating to get the following equation:

Where each line corresponds to a fixed value of

t, with

being the flat line on the

r axis. Vertical worldlines on this coordinate chart are the worldlines of observers at rest and their height is the proper time elapsed. We can see that for a given

, less proper time passes for rest observers the closer they are to the horizon. The worldlines of observers falling from two different radii are also shown in

Figure 4.

We can conceptualize the t coordinate lines as analogous to isocontours on a contour chart, where represents the highest level and represents the lowest level. The trajectory of a falling observer follows the geodesic of shortest distance from the highest level to the lowest level, ensuring their worldline remains perpendicular to the t coordinate lines at every point. Consequently, the worldlines of all falling observers start vertically at , gradually curving to maintain orthogonality to the t coordinate lines at each point, and eventually becoming horizontal at , .

But if the Black Hole is in the interior metric, then the proper time between

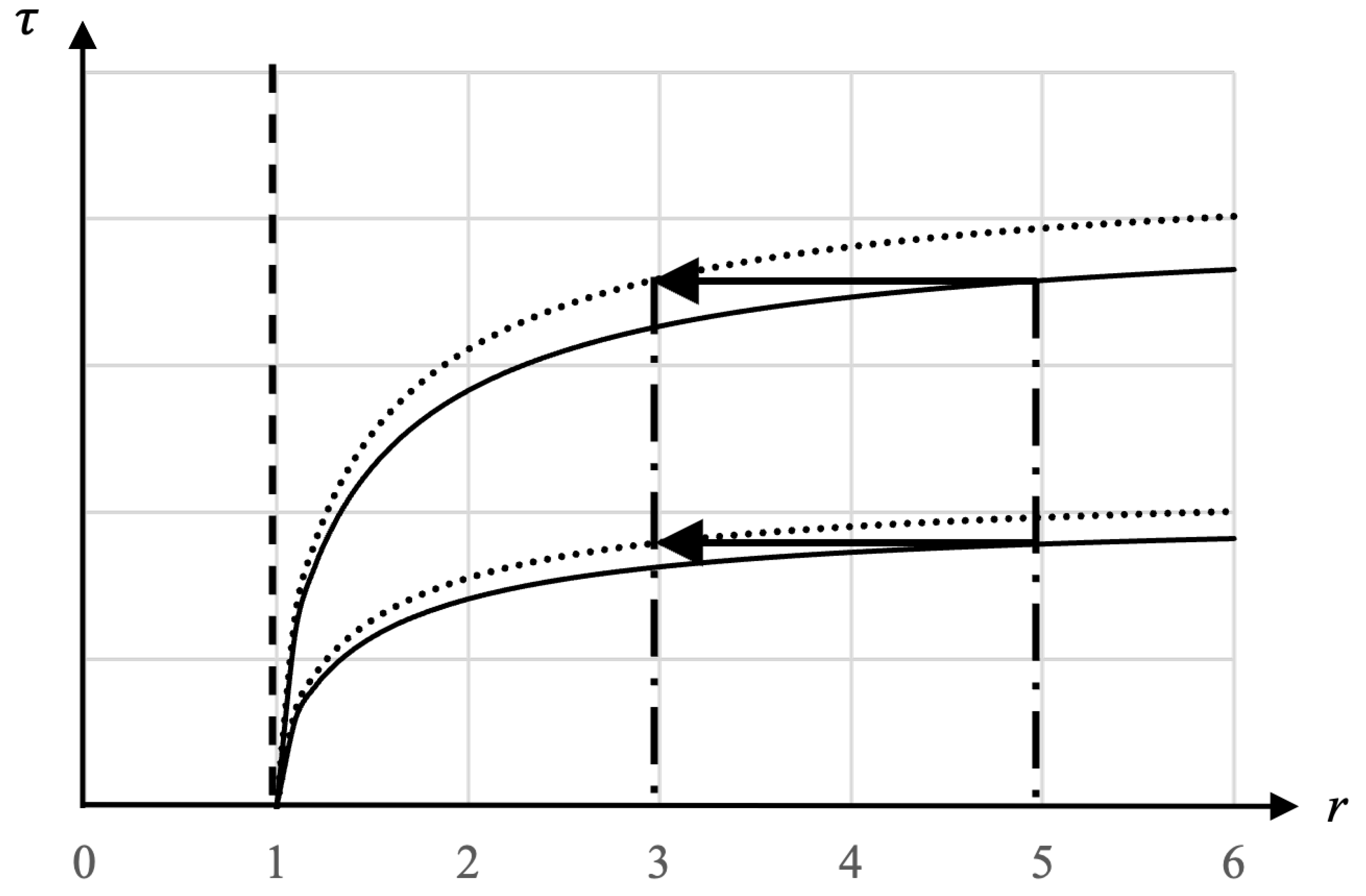

t coordinate lines will increase as the system falls to

in the interior metric. This has the effect of shifting the gravitational field inward toward the horizon over time as depicted in

Figure 5

The solid

t-coordinate lines are the

t coordinate lines at some reference time

in the interior metric. The dotted lines are the

t-coordinate lines at some

such that those lines are separated by more proper time relative to the solid lines. As shown in

Figure 5, this increase in proper distance between coordinate lines shifts the location of a given

closer to the horizon. Since

is related to the acceleration a rest observer feels at a given distance from the horizon, this tells us that the acceleration field is also squeezed toward the horizon as the Black Hole falls toward

in the interior metric.

So while the and terms of the Black Hole system are contracted to a point, the t coordinate far from the Black Hole we placed in the interior metric becomes spacelike and its expansion represents an expansion of space. We can understand this by adding more Black Holes into the shell such that they are distributed homogeneously and isotropically in the infinite space t inside the shell, but separated enough that they do not interact with each other gravitationally. The space between those systems is a vacuum parameterized by the t coordinate of the interior metric.

The equation for a 2D hyperboloid surface embedded in three dimensions is given by:

For our purposes, we will be considering the special case where

, which gives the one and two sheeted hyperboloids of revolution. Next, we note the following relationship with regards to the Kruskal-Szekeres coordinates:

Equation 4 appears to be only for one dimension of space, but if we think of

X as a radius, then it can describe a 3D isotropic hyperboloid. So comparing to Equation 3, if we set

and

where

R is a radius of a circle in this example, we obtain an equation that matches the form of Equation

3 where :

Equation

5 describes 2D hyperboloid surfaces for a given

r where the interior metric has negative

. This means that the interior metric describes a 2-sheeted hyperboloid. Note that

Figure 1 is for constant

and

, meaning there exists identical diagrams for each 3D spherical direction.

We will for now focus on region II from

Figure 1, where region I captures the external metric and region II captures the interior metric. If we choose some constant value of

in the interior metric and plot Equation

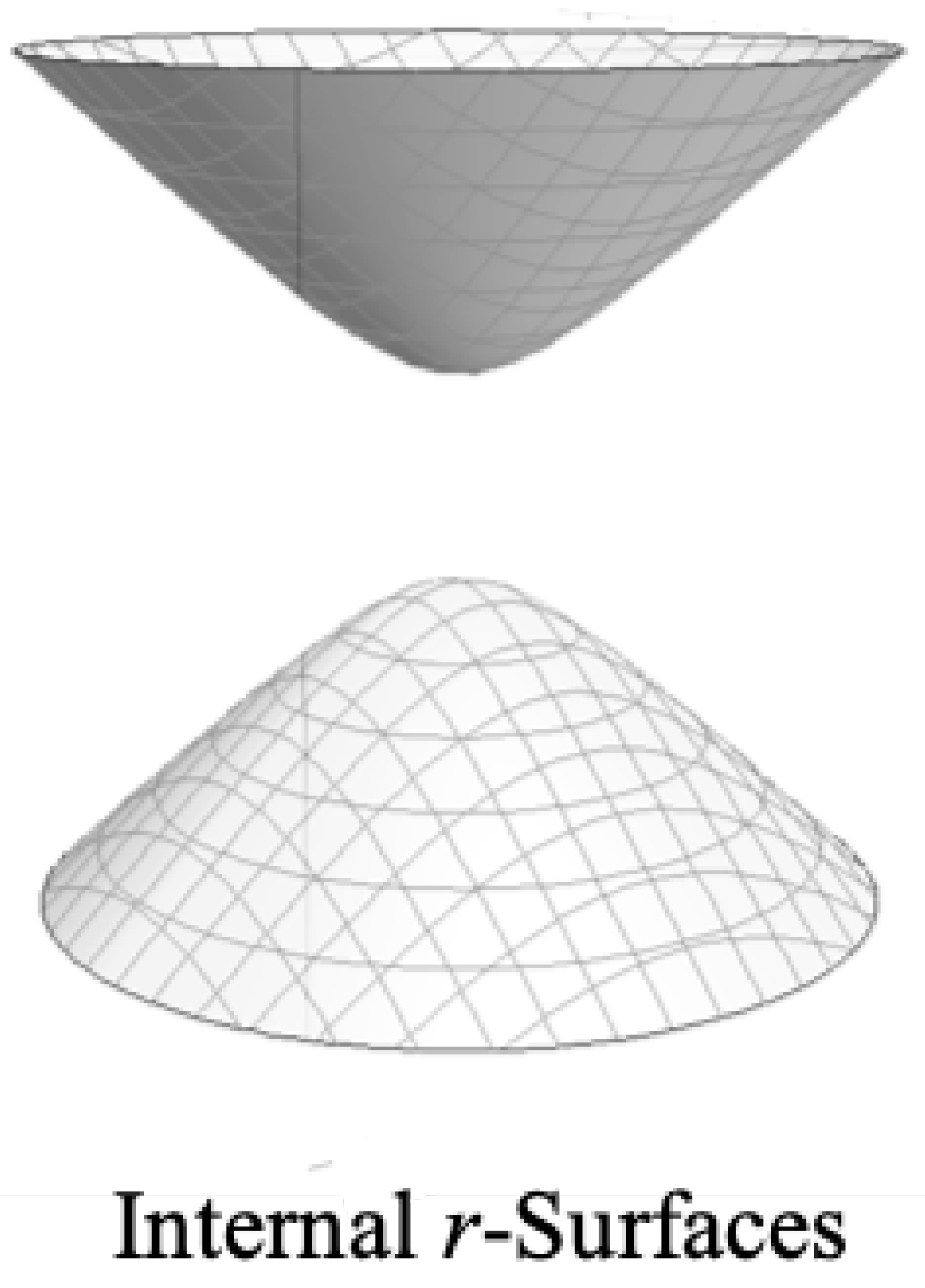

5 for the interior metric, we get the surfaces shown in

Figure 6.

We see we have two separate sheets, but for the moment, we will only focus on the top sheet. The meaning of the bottom sheet will be discussed in

Section 4.

Light cones in

Figure 6 are oriented vertically and light travels on 45 degree lines. If we choose any point on the surface and project a past and future light cone from that point. We can move that point to the apex of the surface (at

) by hyperbolically rotating the spacetime until the point is at the apex. We can do this without changing anything in the spacetime because the hyperbolic rotation is a translation in

t, and

is Killing vector of the manifold. When the point is rotated to the apex, we see then that the light cone is symmetric relative to the surface left and right and into and out of the page. This symmetry means the spacelike foliations of the interior metric’s vacuum are isotropic and homogeneous.

This can be extended to three spatial dimensions by allowing

R to be the radius of a 3D sphere. In this formulation, we put ourselves at

and the circles on the surfaces in

Figure 6 will become spheres that are isotropic and homogeneous in space and inhomogeneous in time, which is consistent with the Cosmological Principle.

So the surface of

Figure 6 represents the vacuum of the interior metric with nothing (not even another Black Hole) inside of it. There are no intrinsic spacelike spherical features in this vacuum, and so on its own, it describes a homogeneous space that expands over time (this will be discussed in more detail in

Section 3). But when we place black holes in this spacetime, they create spacelike spherical regions in the vacuum that contract over time as has been discussed.

We can depict Black Holes inside the interior metric and better understand their contraction over time with

Figure 7.

Figure 7 is a modified picture of region II from the Kruskal-Szekeres coordinate chart in

Figure 1 with the dark hyperbolas represent the singularity at

, the 45 degree dashed lines represent the surface of the interior metric, and the hyperbolas between those are the interior vacuum at some

with three black holes shown as wells stretching out from this hyperbola. The undeformed hyperbola where the wells are is shown as a dotted line for reference.

So we see from the figure that the gravitational wells created by Black Holes can be understood as the spacelike hypersurface in the interior spacetime being locally stretched back to the surface of the interior spacetime. Since is a Killing vector of the spacetime, we can apply hyperbolic rotations to the hyperbola to make any of the Black Holes on the surface centered on the diagram (i.e. there is no difference between the three Black Holes in the figure because we can hyperbolically rotate any of them to the center of the diagram). The relative sizes of the wells are related to the relative Schwarzschild radii of each Black Hole.

The wells stretch out to the surface on the interior region because, as shown in Appendix A, the event horizon of the exterior metric can always be hyperbolically rotated to . So it is important to keep in mind that the tips of the wells of the Black Holes represent the event horizon of the exterior solution, not the singularity.

The left side of

Figure 7 shows the vacuum with three Black Holes at some time

and the right side shows the same surface at a later time

. As the surface moves up toward

, the wells close. This is the contraction of the gravitational field discussed earlier. As the surface moves to

, the wells close completely and the spacelike surface becomes completely flat and empty. So the contraction of the

and

terms of the internal metric lead to a contraction of the wells and the expansion of the

term results in the expansion of the space between the different wells.

A notable point here is that the entire surface, including the wells, represent an interior hypersurface at some

r. The meaning of this will be expanded on in

Section 3, but we should note that as we change the value

r of the hypersurface, the relative positions of the wells can change and new wells can be formed at different times (i.e. the hypersurface at some

may have no wells, whereas the same surface at some later time

can have a well on it if, for instance, a gravitational collapse occurred at some time in between). In fact, we can say that two gravitating systems will combine if they move together more quickly than the

t-vacuum between them expands.

Furthermore, we can think of gravitational wells of non-Black Holes, such as a star, as being indents in the hypersurface that do not reach back to the interior surface at a sharp point, those are just smooth, shallower dips in the surface.

It is interesting to think about the interplay of space and time from these gravitational wells. The surface without a Black Hole is perpendicular to the time dimension r in the interior metric. But the gravitational wells stretch that surface in the r direction. Thus, the r direction of the interior region gains spacelike characteristics in the gravitational wells because the spacelike surface gets deformed in the r direction. This is why the r coordinate is timelike in the interior vacuum and spacelike in the exterior vacuum. It also creates a connection between the ’up’ and ’down’ directions of gravity that come from the exterior metric, and ’future’ and ’past’ from the interior metric. In this model, ’up’ and ’future’ are the same direction on the manifold, where when we observe this direction from the exterior metric point of view, we see the direction as spacelike and when we observe it from the interior metric point of view, we see it as timelike. The same is true for the ’down’/’past’ direction.

We will explore what occurs at the event horizon of the gravitational wells in

Section 4, but first we will look at this model in the context of the cosmology of the Universe.

3. The Interior Metric as a Model of Cosmology

The interior metric describes a situation where the volume of the space of the vacuum is zero when (because the term is zero there), expands over time, and becomes infinite at . This bears a striking resemblance to the Big Bang model of cosmology where the Universe started in an infinitely dense state and subsequently expanded and cooled, condensing into galaxies and gravitational clusters forming a cosmic web surrounding spherically symmetric vacuums of space.

The FRW metric of cosmology describes a perfect fluid with uniform pressure and matter density throughout space which expands over time. This is an adequate description of the Universe in early times when the entire Universe was a hot plasma with uniform density and pressure. But after recombination, The pressure and density of the Universe was no longer uniform. Matter began to clump together into structures creating areas of high and low pressure/density.

We can model cosmology as being described by the FRW metric in the pre-recombination era, but after recombination, the Universe is governed by the Schwarzschild metric. The CMB represents a surface r just inside the shell of the interior Schwarzschild metric, which is a uniform surface that is seen as a surface a the same constant time, regardless of the time r from which it is observed. As will be shown, modelling the Universe in this way will help us resolve the Dark Energy problem without the need for a cosmological constant. This is because the expansion of the t dimension of the interior metric follows a pattern of infinite initial expansion, followed by a period of slowing expansion, followed again by a period of accelerated expansion. This accelerated expansion accounts for the dark energy without the need for a cosmological constant.

If we consider a filament in the cosmic web, which is where most of the matter is but is still mostly vacuum, we can think of the filament as a cylinder that will get stretched along its length and squeezed radially over time. In other words, the cosmic web can be understood as the ongoing ’spagghetification’ of the matter in the Universe as it falls toward the singularity at . Furthermore, the contraction of the term which puts an inward pressure on the gravitating systems may account for the dark matter observations, but this is left as an area for future research.

Let us now compare the Schwarzschild cosmological model to cosmological data to show that the model is in very good agreement with experiment.

3.1. The Scale Factor

Expressions for the proper time interval along lines of constant

t and

and the proper distance interval along hyperbolas of constant

r and

from Equation

1 are:

And the coordinate speed of light is given by:

Where

a is the scale factor (because

t is the spatial coordinate and

r is the time coordinate and therefore Equation

6 describes how the proper distance between two points separated by coordinate distance

evolves over time). First we should notice that none of the three equations depend on the

t coordinate. This is good because the

t coordinate marks the position of other galaxies relative to ours. Since all galaxies are freefalling in time inertially, the particular position of any one galaxy should not matter. The proper temporal velocity, proper distance, and coordinate speed of light only depend on the cosmological time

r.

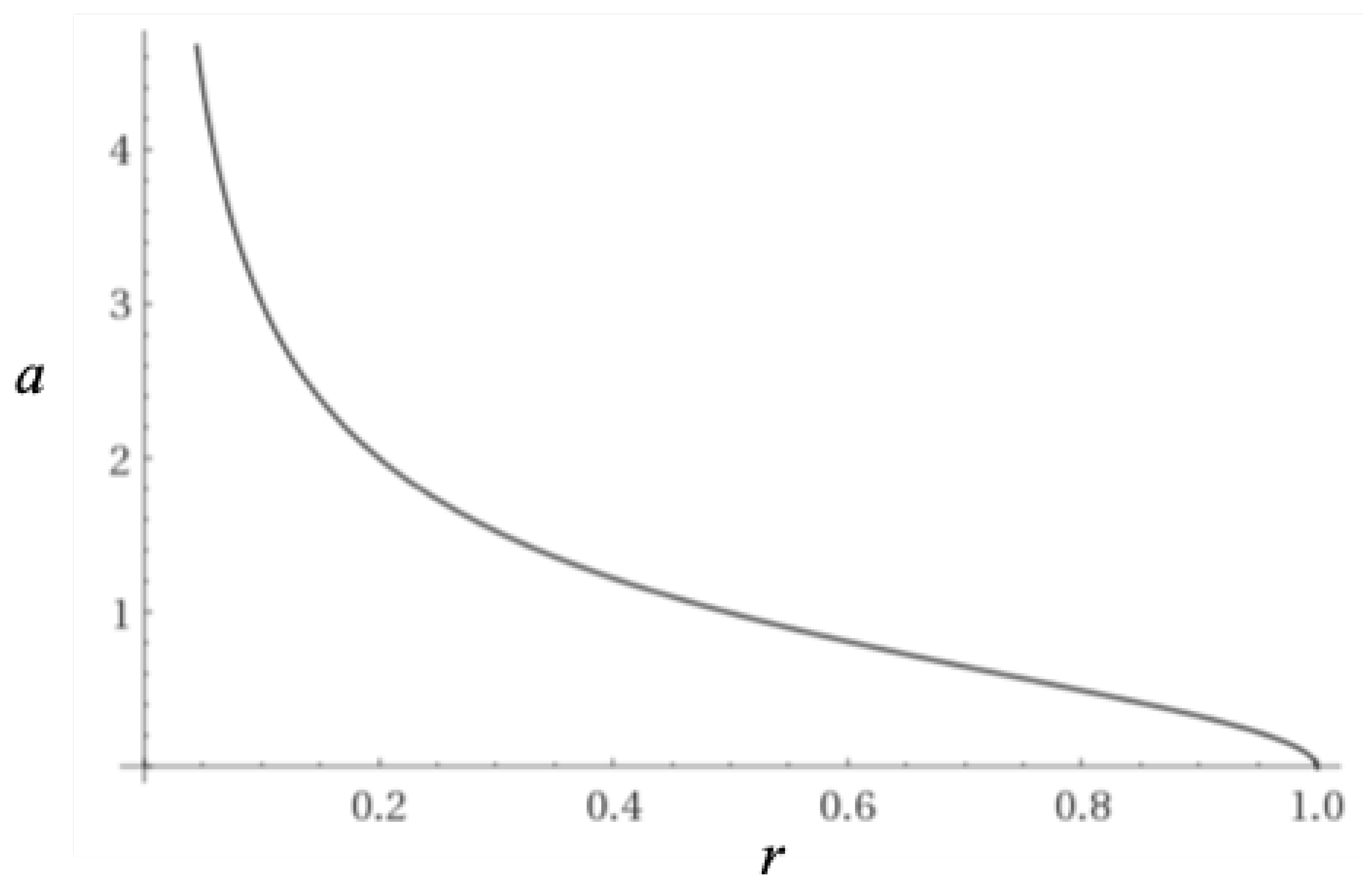

A plot of the scale factor vs.

r (with

) is given in

Figure 8 below:

3.2. The Co-Moving Observer

Let us take a co-moving observer somewhere in the Universe we label as as the origin of an inertial reference frame. We can draw a line through the center of the reference frame that extends infinitely in both directions radially outward. This line will correspond to fixed angular coordinates (). There are infinitely many such lines, but since we have an isotropic, spherically symmetric Universe, we only need to analyze this model along one of these lines, and the result will be the same for any line.

We must determine the paths of co-moving observers (

in the spacetime. For this we need the geodesic equations for the interior Schwarzschild metric [

1] given in Equation

1. In these equations

u represents a time constant (in

Figure 1, the value of

u is 1). The following equations are the geodesic equations of the interior metric for

t and

r) for

:

Looking at points

, then by inspection of Equation

9 it is clear that an inertial observer at rest at

t will remain at rest at

t (

if

).

Let us next demonstrate how the interior metric fits with existing cosmological data and calculate various cosmological parameters using that data.

3.3. Calculation of Cosmological Parameters

In order to compare this model to cosmological data, we must solve for

u and find our current position in time (

) in the model. Reference [

2] gives us transition redshift values ranging from

to

, depending on the model used. We can use the expression for the scale factor in Equation

6 to get the expression for cosmological redshift from some emitter at

r measured by an observer at

[

1]:

Furthermore, the deceleration parameter is given by:

By setting Equation

12 equal to zero, we can solve for

. With this and equation

6, we can calculate the scale factor at the Universe’s transition from decelerating to accelerating expansion

:

Using Equations

11,

13, and the transition redshift estimate, we can get an expression for the present scale factor:

Next, we find expressions for

u and our current radius

by noting that light from the CMB has been travelling for roughly 13.8 billion years of coordinate time

r. Therefore, we can set

and use Equations

6 and

14 to obtain the following for

u and

:

Next we compute the CMB scale factor (

) and coordinate time (

) in this model where the redshift of the CMB (

) is currently measured to be 1100:

We can next derive the Hubble parameter equation using the scale factor. The Hubble parameter is given by (in units of

):

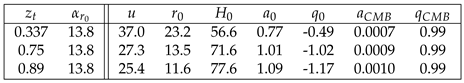

Table 1 below gives the values of

u,

,

,

,

,

, and

given the upper and lower bounds of

from [

2] as well as the 0.75 transition redshift value and assuming

. All times are in

and

is in

.

From the results in

Table 1, we see that the true transition redshift is likely close to 0.75 given the fact that the current value of the Hubble constant is known to be near 71.6. Thus, more accurate measurements of the transition redshift are needed to increase the confidence of this model, but the 0.75 transition redshift is in fact a prediction of the model and we will see this when it is compared to astronomical data later in this section.

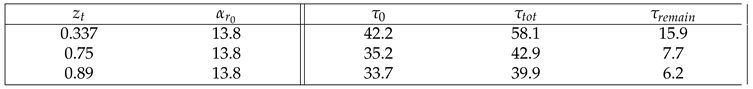

Table 2 has the proper times from

to the current time for co-moving observers (

) by integrating Equation

1. The column

gives the time from

to

. The expression for

turns out to be quite simple:

In

Table 2 below, the column

gives the time between

and

.

Note that the proper time

of the current age of the Universe is actually much larger than the coordinate time

. And even though we are presently only about halfway through the “coordinate life” of the Universe (according to

Table 1), the amount of proper time remaining is actually much less than the amount of proper time that has already passed (according to

Table 2). This provides a measurable prediction from the model: as telescopes such as the JWST peer farther into the past with greater accuracy, we should expect to find stars, galaxies, and structures that are much older than expected because of the increased amount of proper time available for such things to form in the early Universe. Hints of this has already been found with the star HD 140283, whose age is estimated to be nearly the age of the Universe itself [

3].

Next we would like to use the

u and

values found to compare the model to measured supernova and quasar data. First we need to find

r as a function of redshift. We can do this by solving for

r in Equation

11:

We can derive the expression for

t vs.

r along a null geodesic where the geodesic ends at the current time

and

by setting

in Equation

1 and integrating:

Next we substitute Equation

21 into Equation

22 to get coordinate distance in terms of redshift:

We need to convert the distance from Equation

23 to the distance modulus,

, which is defined as:

Where

in Equation

24 is the luminosity distance. Luminosity distance is inversely proportional to brightness

B via the relationship:

The brightness is affected by two things. First, the spatial expansion will effectively increase the distance between two objects at fixed co-moving distance from each other. This will reduce the brightness by a factor of

(because the distance in Equation

25 is squared). But there is also a brightening effect caused by the acceleration in the time dimension. We define

as the temporal velocity of the inertial observer at some

r and the speed of light at that

r as

. The ratio of these velocities gives us:

Equation

26 tells us how far a photon travels over a given period of time measured by the inertial observer’s clock. So we see that as light travels from the emitter to the receiver, this speed decreases. This decrease in the speed from emitter to receiver will result in an increased photon density at the receiver relative to the emitter, increasing the brightness. Therefore, this effect will increase the brightness by a factor of:

This effect is not accounted for in the current relativistic cosmological models and therefore gives a second prediction that light from the distant Universe should appear brighter than expected.

Taking these brightness effects into account, the total brightness will be reduced by an overall factor of

relative to the case of an emitter and receiver at rest relative to each other in flat spacetime. Equation

25 in terms of co-moving distance

t and redshift

z becomes:

Giving the luminosity distance as a function of co-moving distance

t and redshift

z:

Which gives us the final expression for the distance modulus as a function of co-moving distance and redshift:

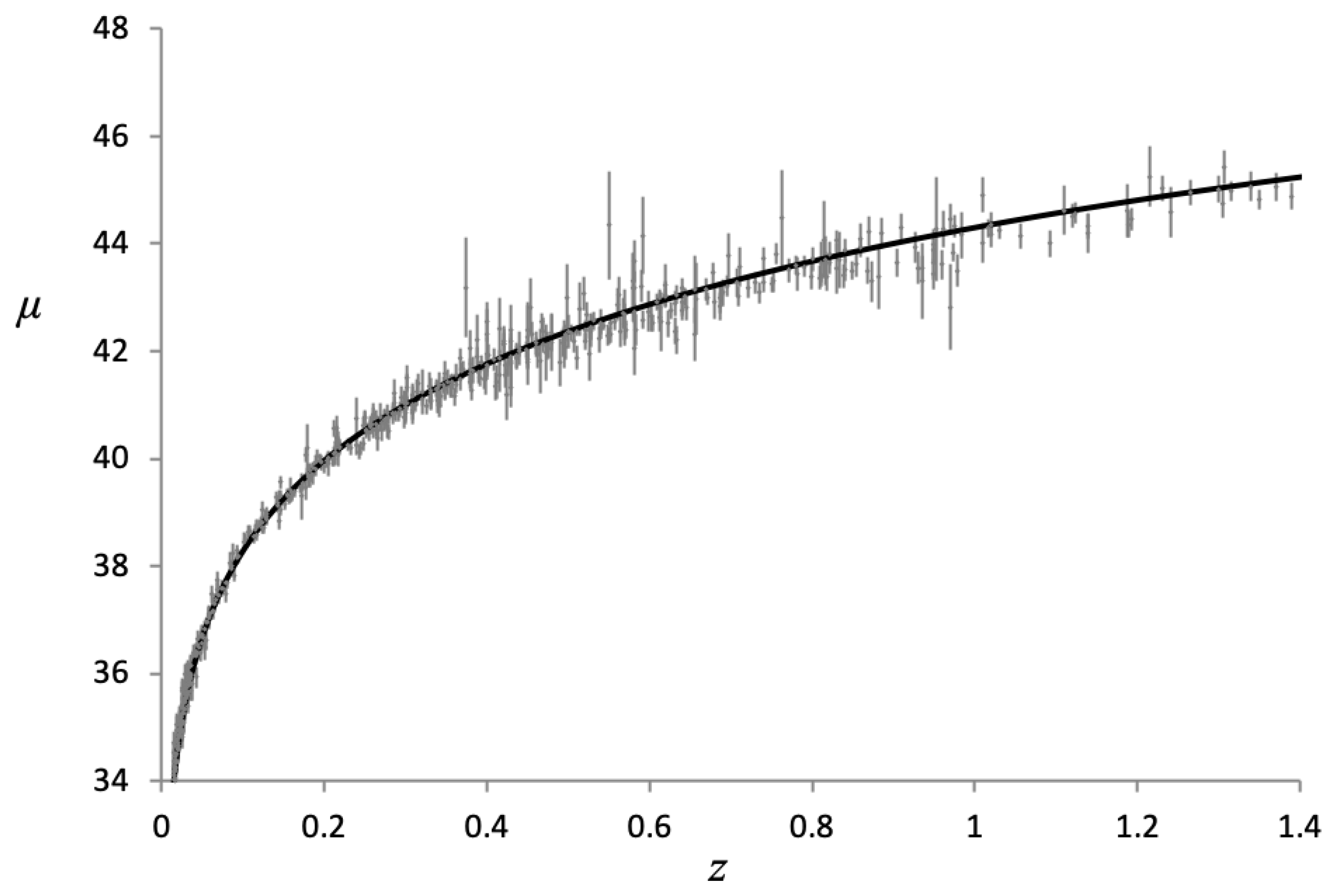

A plot of distance modulus vs. redshift is shown in

Figure 9 below plotted over data obtained from the Supernova Cosmology Project [

4]. A Curve calculated from the

row in

Table 1 is plotted as this value provides the best fit for the data.

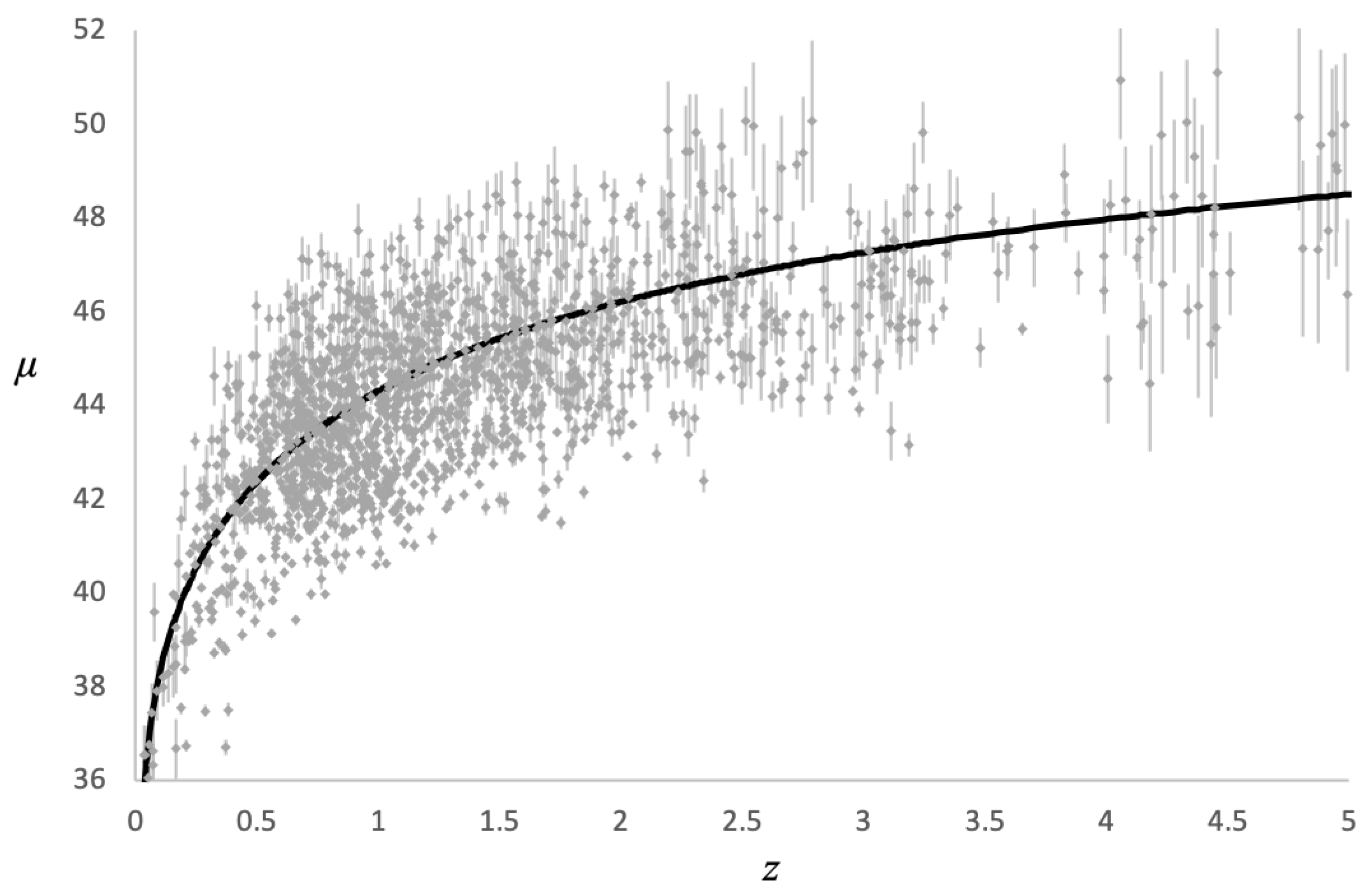

Figure 10 shows the same curve from

Figure 9 for the Hubble diagram plotted out to higher redshifts with the quasar data from [

5] also shown with error bars.

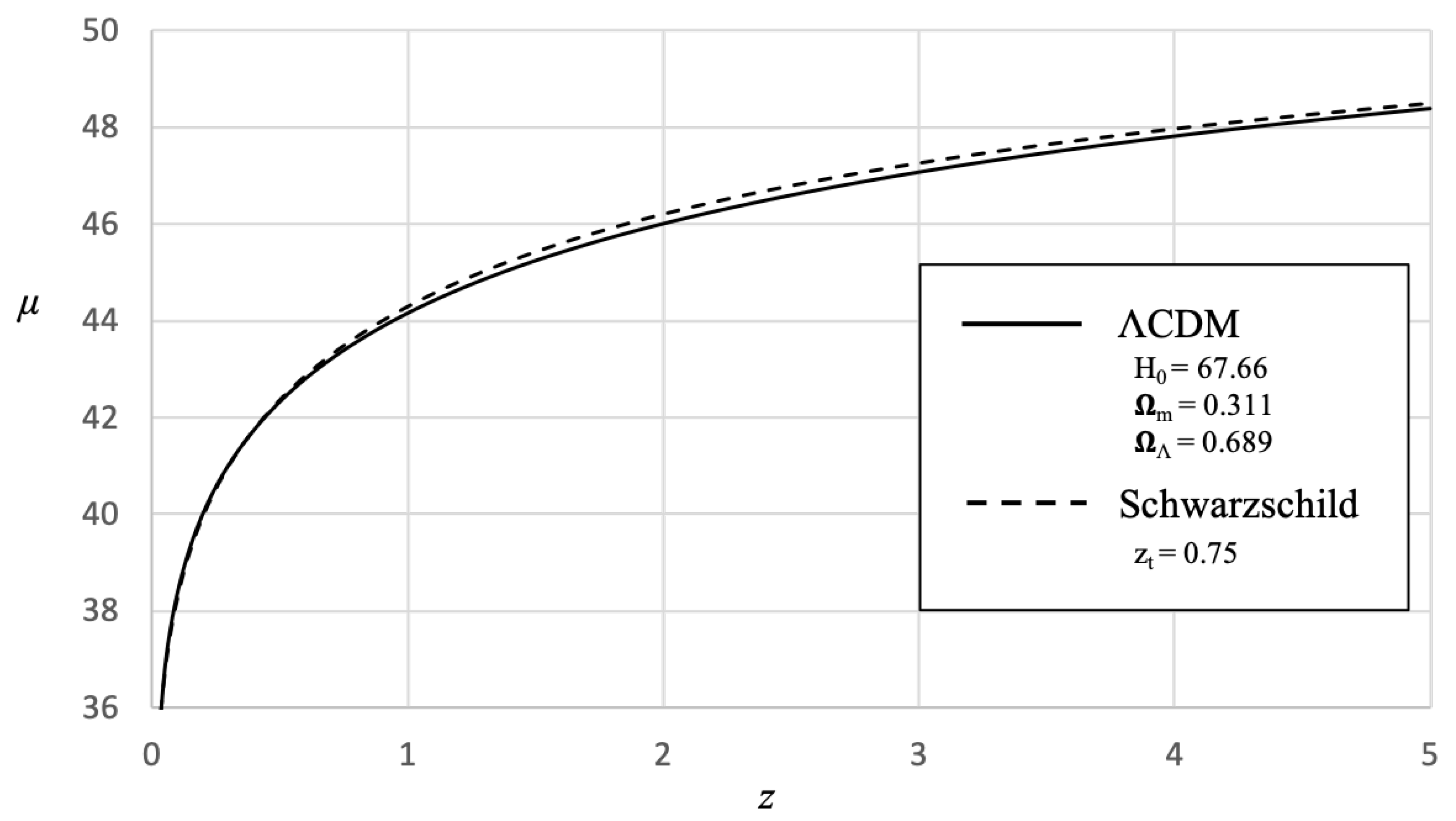

Figure 11 is a comparison of the

CDM model with the Schwarzschild model with the

transition redshift. As can be seen in this figure, both models are in very close agreement for the range of data available.

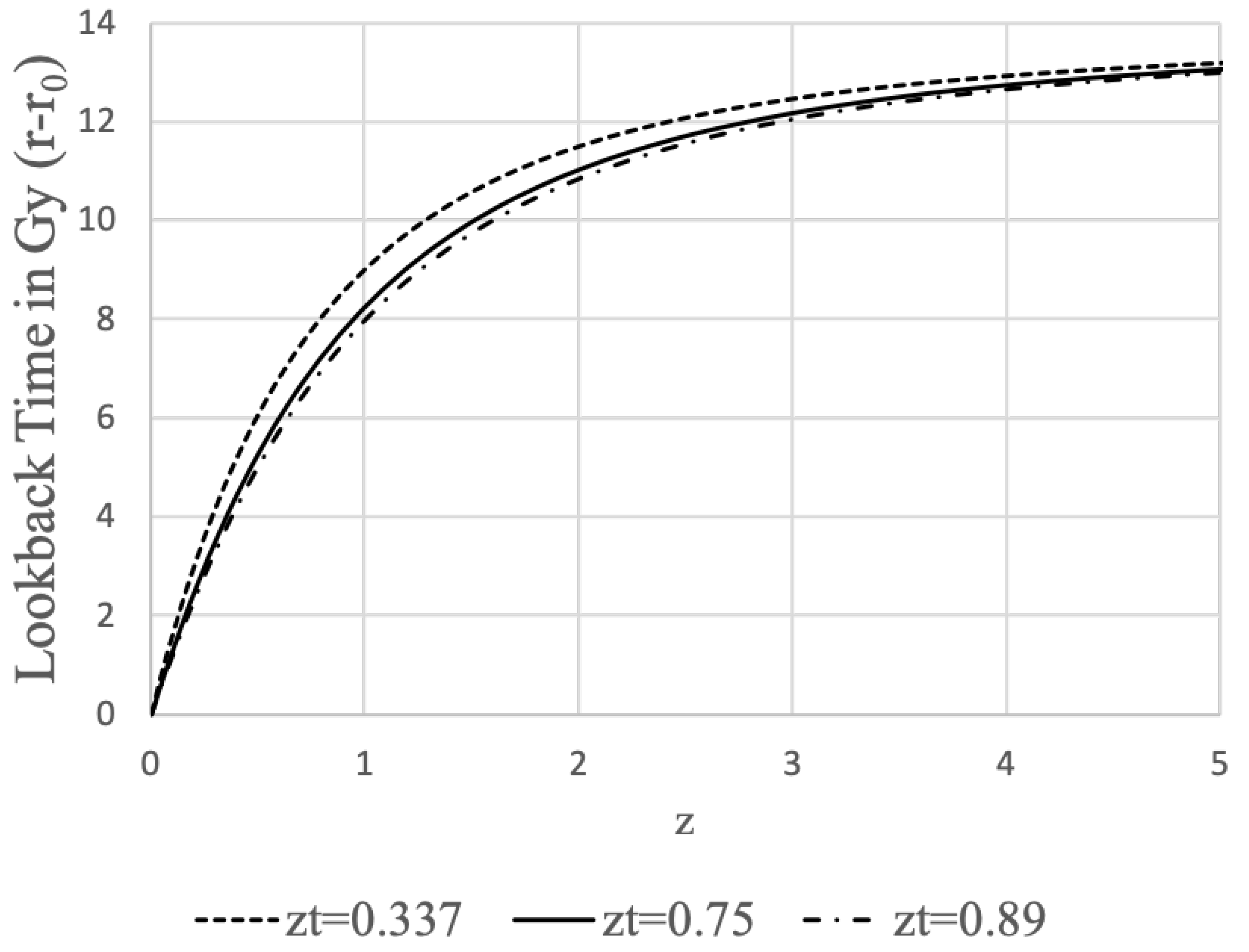

Finally, by subtracting

from Equation

21 we can calculate the lookback time for a given redshift.

Figure 12 shows the lookback time vs. redshift for the three transition redshifts from

Table 1.

3.4. Behavior of Light in the Interior Metric

The path of light should also be affected by the angular term of the interior metric. When light is gravitationally lensed, its momentum vector changes direction, meaning it gains a non-zero

. We can see the precise behaviour of lensed light by looking at the geodesic equation for angular motion [

1] (we will examine the case for planar rotation where

).

For light, we will use

. If we consider light lensed by a galaxy, as the light passes the galaxy at some coordinate time

, it will have some angular velocity

and initial angle

as it leaves the galaxy. It is currently assumed that the light then continues along a straight line as it leaves the gravitational field, but as we shall see, this is not the case. The

would be the angle caused only by the gravitational lensing, without any additional effects from the cosmological model (i.e. the angle we would expect when only taking into account the mass of the galaxy). Given these initial conditions, the solution to Equation

31 is:

Both the bracketed expression and

will always be negative (because

is negative and

) such that the second term is always positive. Therefore, the observed lensing angle will be increased by the amount

as a result of this effect (where

r is the coordinate time at which the light is observed). Furthermore, since

for the light increases over time, the

will correspondingly decrease as well and the result of this is that the increase in lensing angle over time will also result in a redshift of the light relative to unlensed light.

We see that the ’excess angle’ is dependant on the lensing rate . So if we consider two cases where in one case, the light is gently lensed over a large distance/time by some angle and in the other case, light is lensed by a more dense mass the same , the lensing rate would be higher in the second case relative to the first. So even though the pure gravitational lensing angle would be the same in both cases, the observed angle would be greater in the second case because the lensing rate would be greater in that case.