Submitted:

02 February 2023

Posted:

03 February 2023

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Equivalence of Traffic Flow Models

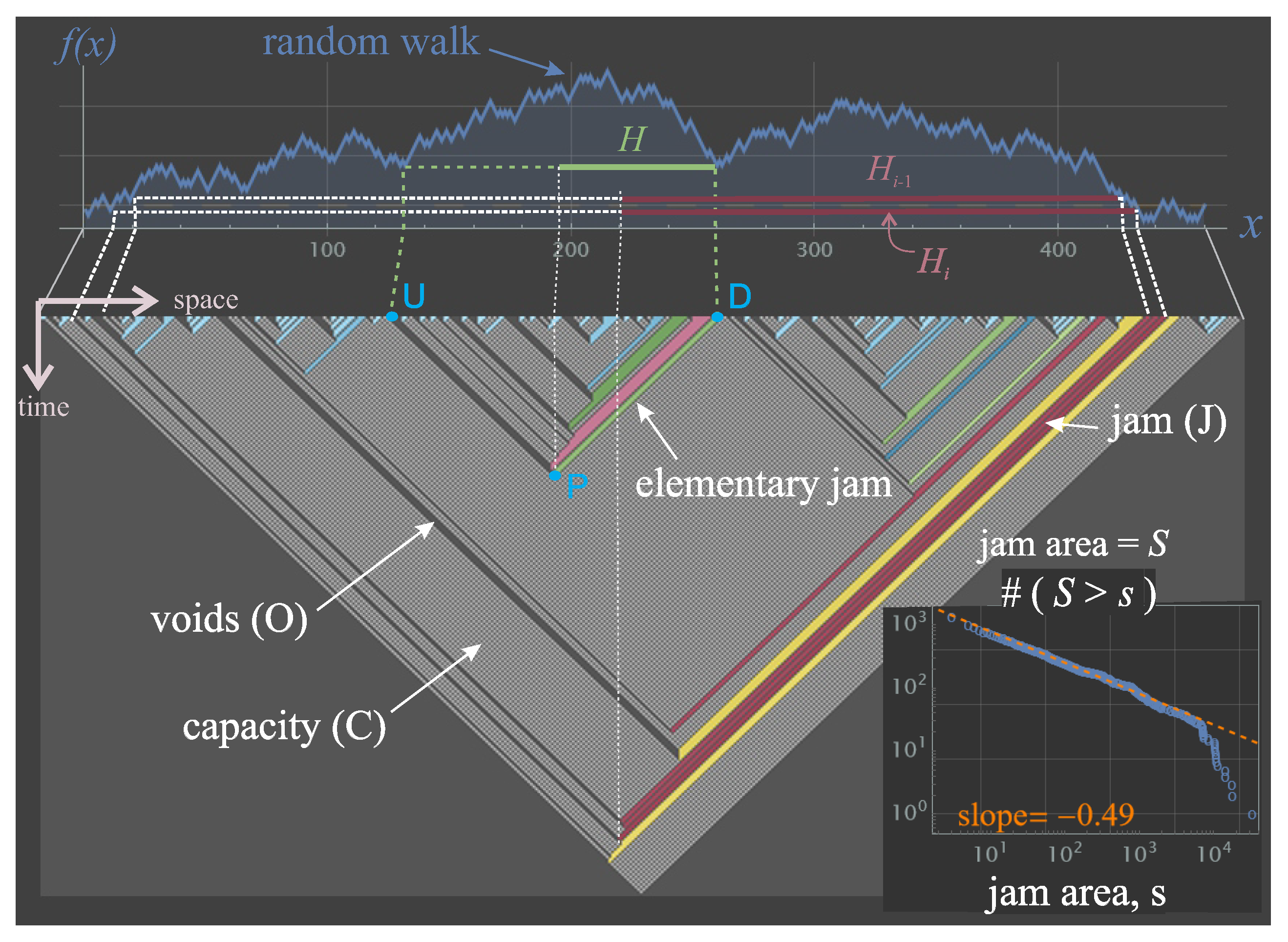

3. The Root Cause of Criticality in Traffic Flow

3.1. Lifetime of Elementary Jams

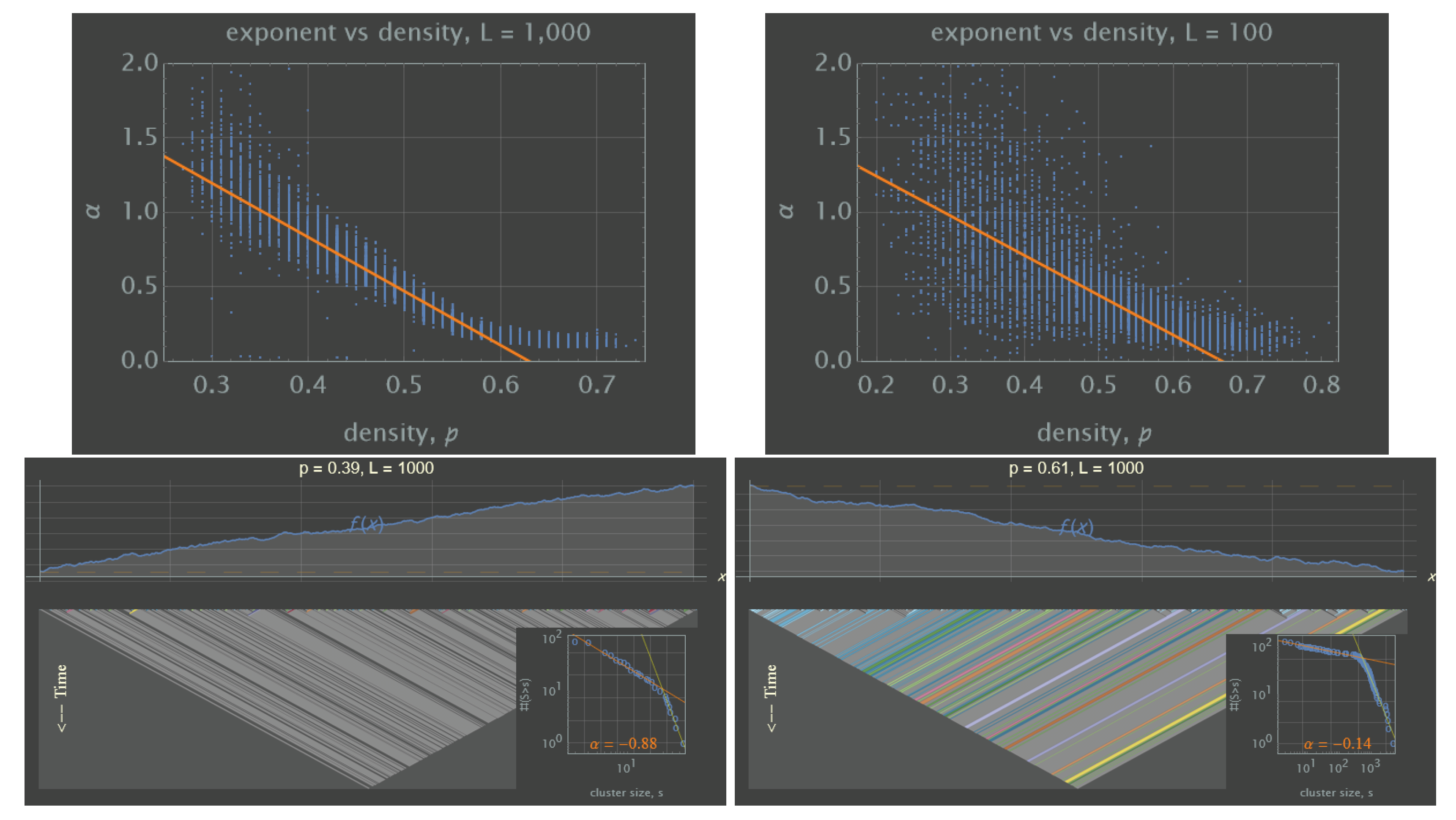

3.1.1. Jam sizes

3.1.2. Exponent Near the Critical Density

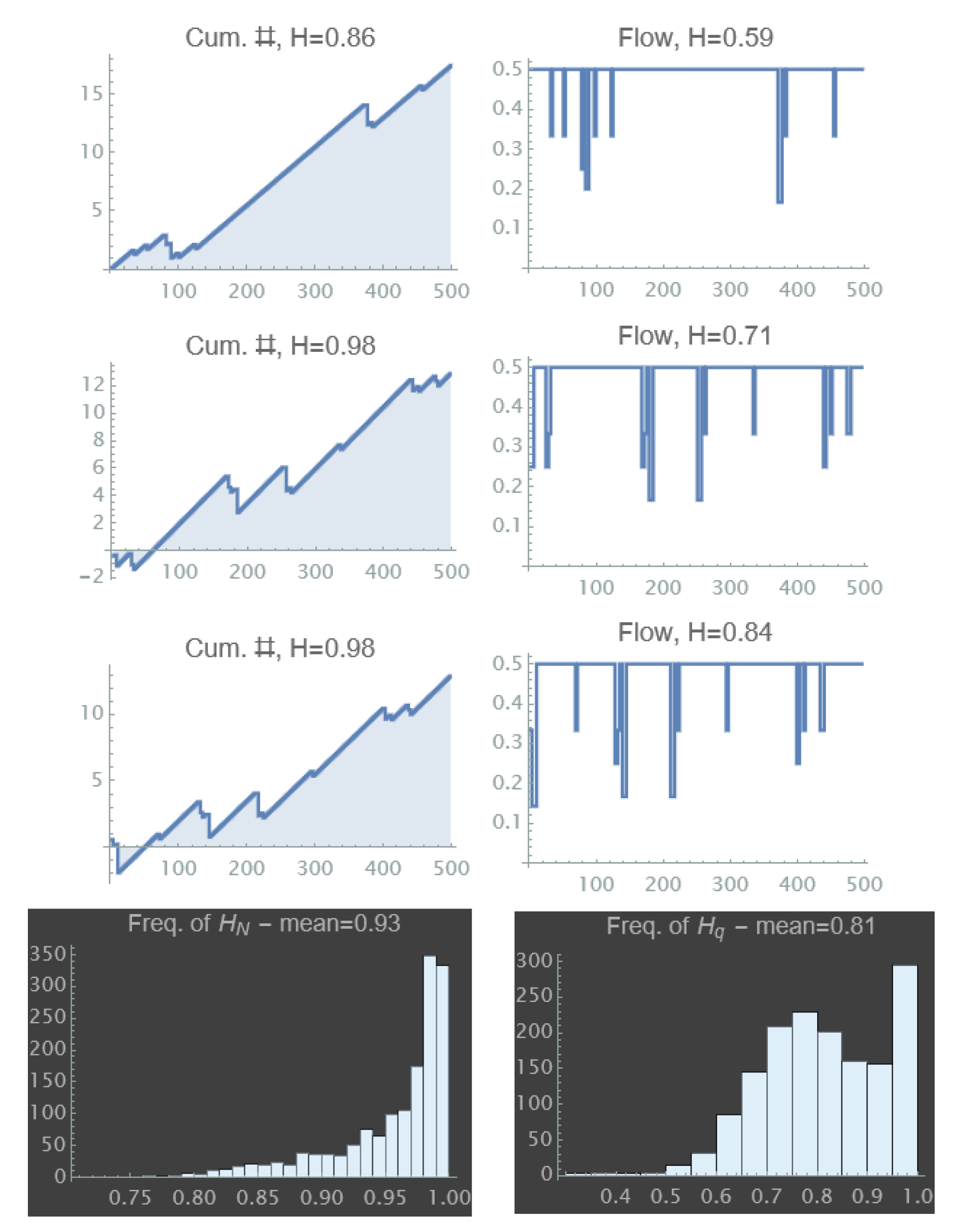

4. Aggregate Measures of Performance during the Transition to Equilibrium

4.1. Delay, Flow and Speed

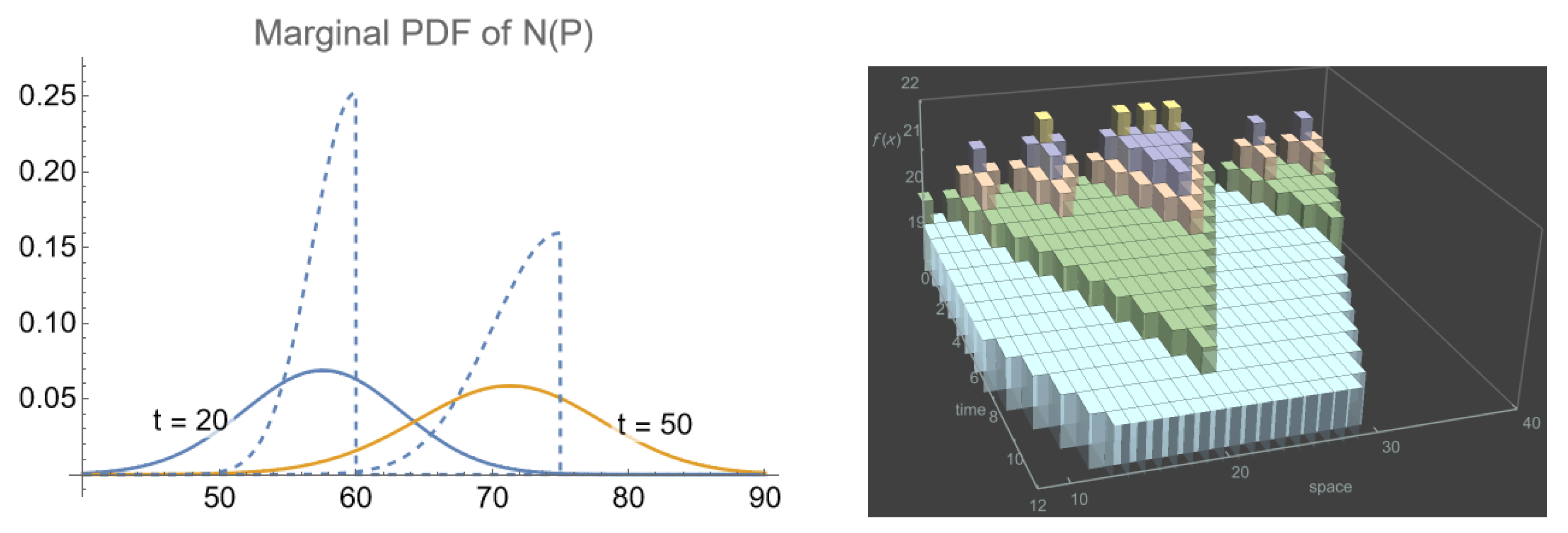

4.2. Moments and Probability Densities

5. Discussion and Outlook

Acknowledgments

Appendix A. Marginal Distribution of the N-surface

Appendix B. Distribution of Local Flows and a Validation

References

- Zeng, G.; Li, D.; Guo, S.; Gao, L.; Gao, Z.; Stanley, H.E.; Havlin, S. Switch between critical percolation modes in city traffic dynamics. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 2019, 116, 23–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, L.; Zeng, G.; Li, D.; Huang, H.J.; Stanley, H.E.; Havlin, S. Scale-free resilience of real traffic jams. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 2019, 116, 8673–8678. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zeng, G.; Gao, J.; Shekhtman, L.; Guo, S.; Lv, W.; Wu, J.; Liu, H.; Levy, O.; Li, D.; Gao, Z.; others. Multiple metastable network states in urban traffic. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 2020, 117, 17528–17534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bak, P.; Tang, C.; Wiesenfeld, K. Self-organized criticality: an explanation of 1/f noise. Phys. Rev. Lett 1987, 59, 381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dănilă, B.; Harko, T.; Mocanu, G. Self-organized criticality in a two-dimensional cellular automaton model of a magnetic flux tube with background flow. Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society 2015, 453, 2982–2991. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aschwanden, M.J. A macroscopic description of a generalized self-organized criticality system: Astrophysical applications. The Astrophysical Journal 2014, 782, 54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nagatani, T. The physics of traffic jams. Reports on progress in physics 2002, 65, 1331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Helbing, D. Traffic and related self-driven many-particle systems. Reviews of modern physics 2001, 73, 1067. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chowdhury, D.; Santen, L.; Schadschneider, A. Statistical physics of vehicular traffic and some related systems. Physics Reports 2000, 329, 199–329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nagatani, T. Traffic flow on percolation-backbone fractal. Chaos, Solitons & Fractals 2020, 135, 109771. [Google Scholar]

- Taleb, N.N. Statistical consequences of fat tails: Real world preasymptotics, epistemology, and applications; STEM Academic Press, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Halperin, B.; Hohenberg, P. Scaling laws for dynamic critical phenomena. Physical Review 1969, 177, 952. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zipf, G. Human Behaviour and the Principle of Least Effort, 1949.

- Hurst, H.E. Long-term storage capacity of reservoirs. Transactions of the American society of civil engineers 1951, 116, 770–799. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mori, T.; Smith, T.E.; Hsu, W.T. Common power laws for cities and spatial fractal structures. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 2020, 117, 6469–6475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- West, G.B.; Brown, J.H.; Enquist, B.J. A general model for the origin of allometric scaling laws in biology. Science 1997, 276, 122–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Newman, M.E. Power laws, Pareto distributions and Zipf’s law. Contemporary physics 2005, 46, 323–351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mandelbrot, B.; Hudson, R.L. The Misbehavior of Markets: A fractal view of financial turbulence; Basic books, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Kobayashi, Y.; Takayasu, H.; Havlin, S.; Takayasu, M. Robust Characterization of Multidimensional Scaling Relations between Size Measures for Business Firms. Entropy 2021, 23, 168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Watanabe, H.; Takayasu, H.; Takayasu, M. Relations between allometric scalings and fluctuations in complex systems: The case of Japanese firms. Physica A: Statistical Mechanics and its Applications 2013, 392, 741–756. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clauset, A.; Shalizi, C.R.; Newman, M.E. Power-law distributions in empirical data. SIAM review 2009, 51, 661–703. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nagel, K.; Paczuski, M. Emergent traffic jams. Physical Review E 1995, 51, 2909. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paczuski, M.; Nagel, K. Self-organized criticality and 1/f noise in traffic. Traffic and granular flow. World Scientific Singapore, 1996, p. 73.

- Nagel, K.; Schreckenberg, M. A cellular automaton model for freeway traffic. Journal de physique I 1992, 2, 2221–2229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Daganzo, C.F. A Variational Formulation of Kinematic Wave Theory: basic theory and complex boundary conditions. Transportation Research Part B 2005, 39, 187–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nagel, K. Personal communication, 2021.

- Schadschneider, A. Personal communication, 2021.

- Nagel, K.; Rasmussen, S.; Barrett, C.L. Network traffic as a self-organized critical phenomena. Technical report, Los Alamos National Lab., NM (United States), 1996.

- Rieser, M.; Nagel, K. Network breakdown “at the edge of chaos” in multi-agent traffic simulations. The European Physical Journal B 2008, 63, 321–327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olmos, L.E.; Çolak, S.; Shafiei, S.; Saberi, M.; González, M.C. Macroscopic dynamics and the collapse of urban traffic. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 2018, 115, 12654–12661. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lighthill, M.J.; Whitham, G.B. On kinematic waves II. A theory of traffic flow on long crowded roads. Proceedings of the Royal Society of London. Series A. Mathematical and Physical Sciences 1955, 229, 317–345. [Google Scholar]

- Richards, P.I. Shock waves on the highway. Operations research 1956, 4, 42–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Newell, G.F. A Simplified Car-Following Theory : a Lower Order Model. Transportation Research Part B 2002, 36, 195–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Daganzo, C.F. In Traffic Flow, Cellular Automata = Kinematic Waves. Transportation Research Part B 2006, 40, 396–403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laval, J.A.; Chilukuri, B.R. Symmetries in the kinematic wave model and a parameter-free representation of traffic flow. Transportation Research Part B: Methodological 2016, 89, 168–177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wolfram, S. Cellular automata as models of complexity. Nature 1984, 311, 419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laval, J.A.; Leclercq, L. The Hamilton-Jacobi partial differential equation and the three representations of traffic flow. Transportation Research Part B 2013, 52, 17–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hopf, E. On the Right Weak Solution of the Cauchy Problem for a Quasilinear Equation of First Order. Indiana Univ. Math. J. 1970, 19, 483–487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schroeder, M. Fractals, chaos, power laws: Minutes from an infinite paradise; Courier Corporation, 2009.

- Zaliapin, I.; Kagan, Y.Y.; Schoenberg, F.P. Approximating the distribution of Pareto sums. Pure and Applied geophysics 2005, 162, 1187–1228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fuks, H. Solution of the density classification problem with two cellular automata rules. Physical Review E 1997, 55, R2081. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Edie, L.C. Discussion of Traffic Stream Measurements and Definitions. 2nd Int. Symp. on Transportation and Traffic Theory;, 1965; pp. 139–154.

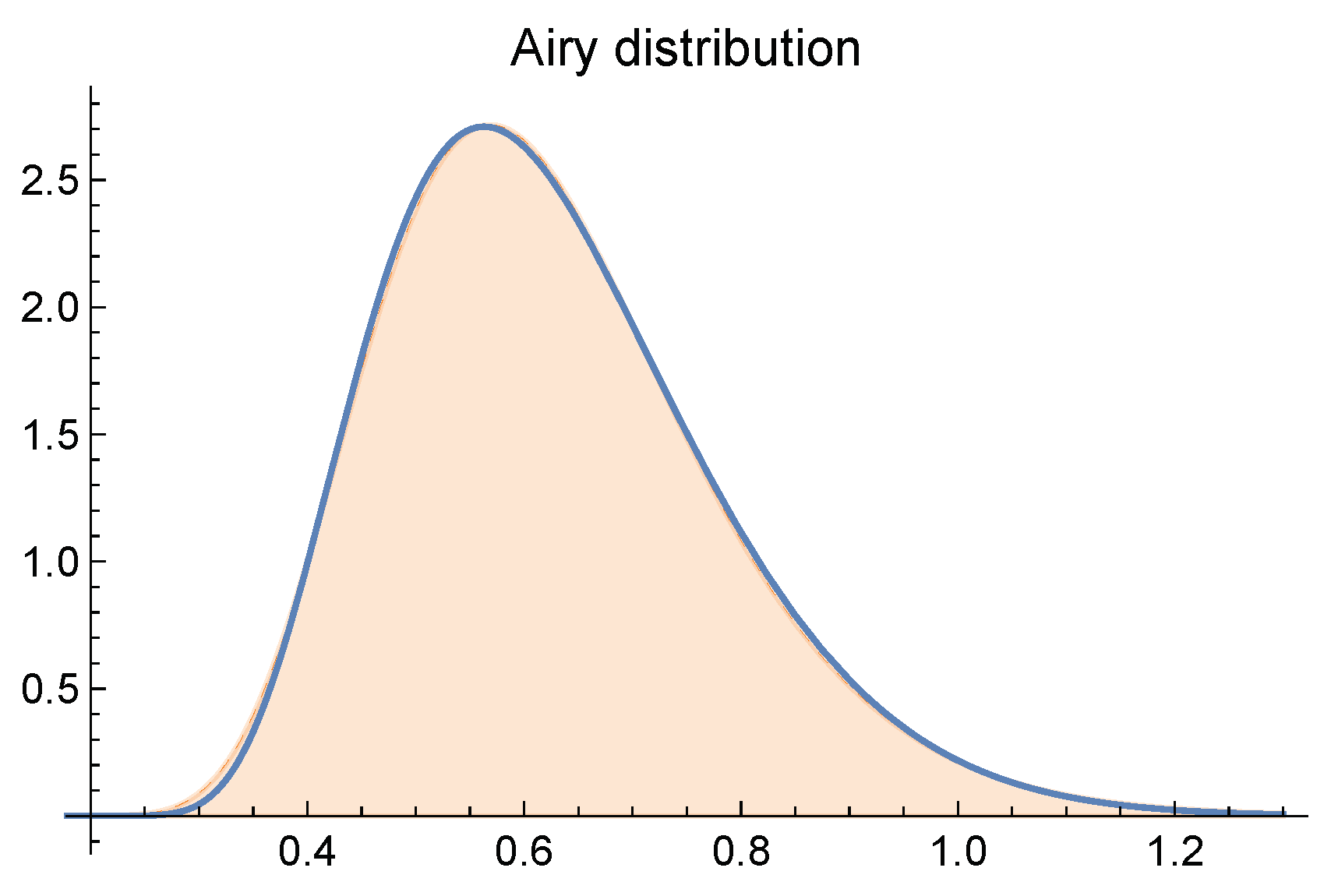

- Majumdar, S.N.; Comtet, A. Airy distribution function: from the area under a Brownian excursion to the maximal height of fluctuating interfaces. Journal of Statistical Physics 2005, 119, 777–826. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Janson, S. Brownian excursion area, Wright’s constants in graph enumeration, and other Brownian areas. Probability Surveys 2007, 4, 80–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agranov, T.; Zilber, P.; Smith, N.R.; Admon, T.; Roichman, Y.; Meerson, B. Airy distribution: Experiment, large deviations, and additional statistics. Physical Review Research 2020, 2, 013174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chand, S.; Aouad, G.; Dixit, V.V. Long-Range Dependence of Traffic Flow and Speed of a Motorway: Dynamics and Correlation with Historical Incidents. Transportation Research Record 2017, 2616, 49–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krause, S.M.; Habel, L.; Guhr, T.; Schreckenberg, M. The importance of antipersistence for traffic jams. EPL (Europhysics Letters) 2017, 118, 38005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Daganzo, C.F. The cell transmission model: A dynamic representation of highway traffic consistent with the hydrodynamic theory. Transportation Research Part B 1994, 28, 269–287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fuks, H.; Boccara, N. Generalized deterministic traffic rules. International journal of modern physics C 1998, 9, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shang, P.; Wan, M.; Kama, S. Fractal nature of highway traffic data. Computers & Mathematics with Applications 2007, 54, 107–116. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).