Introduction:

Bronchiolitis is the most common cause of acute hypoxemic respiratory failure and hospital admissions in young children [

1]. Although admission rates to the pediatric intensive care unit (PICU) have doubled over the last 10 years, controversy over effective therapies remains unsettled [

2].

Recommendations from the American Academy of Pediatrics (AAP) have changed over the past three decades, and, currently, routine use of bronchodilators in bronchiolitis is not supported [

3,

4]. However, beta-agonists are still commonly used in emergency rooms (ER), wards, and PICUs worldwide, and notably, the 2014 AAP recommendations excluded children with severe disease, making choosing the optimal therapies for these cases challenging [

5]. Clinical heterogeneity of bronchiolitis has been proposed as a rationale for variable phenotypic responses to therapies, with many studies supporting the use of bronchodilators [

6]. Due to the absence of definitive guidance, wide practice variations in bronchodilator use have persisted in the ICU, with some authors proposing a trial of albuterol in children with severe bronchiolitis who require non-invasive or invasive ventilatory support [

7,

8].

Studies have aimed to define subsets of patients with bronchiolitis who benefit from bronchodilators based on metrics like airway hyper-reactivity, month of presentation, expiratory wheezing appreciated on physical exam, RSV or rhinovirus positivity, and the presence of family history of atopy [

6,

9,

10,

11]. Bronchodilators are also commonly used in viral-triggered bronchopulmonary dysplasia exacerbations, which are frequently observed among premature infants [

12]. The guideline statement excluded children with severe respiratory failure, and part of the AAP’s argument against bronchodilator use was the absence of a standardized method to assess response to therapy [

3].

This study aimed to evaluate whether the use of bronchodilators is associated with differences in ICU-LOS, hospital LOS, and ICU-level of respiratory support (ICU-LRS) among patients with critical bronchiolitis. As a secondary objective, we assessed whether a family history of atopy or RSV/rhinovirus positivity was associated with differences in these outcomes when patients were stratified by bronchodilator use. Critical bronchiolitis was defined as the need for ICU-LRS and included the use of high-flow nasal cannula (HFNC), non-invasive mechanical ventilation (NIMV), or invasive mechanical ventilation (IMV).

Materials and Methods:

Study Overview

This is a single-center retrospective study conducted at a tertiary children’s hospital. We included children aged 0-24 months admitted to the PICU, step-down ICU (SDICU), and pediatric cardiothoracic ICU (PCTICU) with clinical bronchiolitis requiring ICU-LRS. Children with a recent history of cardiac surgery (<7 days) prior to symptom onset were excluded. The study period was from January 1, 2022, to December 31, 2022. This study was approved by the Institutional Review Board at Loma Linda University Children’s Hospital (IRB #5220357).

Outcome Measure

The primary outcome measures were ICU-LOS, ICU-LRS, and hospital LOS. Patients were divided into two groups for primary analysis: those who received bronchodilators (intermittent or continuous doses) and those who did not. Intermittent bronchodilator use was defined as administration of ≥2 doses during the index hospital admission. Patients who received bronchodilators only in the emergency department, without continued use during the inpatient stay, were assigned to the no-bronchodilator group.

Bronchodilators were delivered via nebulization or metered-dose inhaler (MDI) and included albuterol and levalbuterol. The Critical Bronchiolitis Score (CBS) was used to calculate predicted ICU-LOS and ICU-LRS for all patients [

13]. Although originally validated in patients with bronchiolitis admitted to the PICU, we applied it to patients admitted to both the SDICU and the PCTICU. At our center, patients requiring up to 1.5 L/kg/min of HFNC can be managed in the SDICU—a level of support that would meet PICU admission criteria at many other institutions. To reduce confounding in patients with congenital heart disease (CHD), we excluded those admitted within 7 days of cardiac surgery. For the remaining patients with CHD, documentation in the electronic medical record (EMR) confirmed that their ICU admission was primarily for bronchiolitis rather than cardiac decompensation. This distinction supported the application of the CBS in this subgroup.

Observed ICU-LOS and ICU-LRS were then compared to the CBS-predicted values. We hypothesized that bronchodilator use may be associated with a shorter observed ICU-LOS and ICU-LRS in patients with viral bronchiolitis.

For the secondary analysis, patients were categorized into four subgroups based on their family history of atopy (positive/negative) and bronchodilator use (yes/no). ICU-LOS, hospital LOS, and ICU-LRS were compared across subgroups. We hypothesized that bronchodilators may reduce hospital and ICU-LOS and shorten ICU-LRS in patients with a positive family history of atopy in a first-degree relative.

The four subgroups based on family history of atopy and bronchodilator use were as follows [

Figure 1]:

Positive family history of atopy with bronchodilator use – hereon referred to as FHx Alb (+FH, yes-bronchodilators)

Positive family history of atopy without bronchodilator use – hereon referred to as FHx NoAlb (+FH, no-bronchodilators)

No family history of atopy with bronchodilator use – hereon referred to as NoFHx Alb, (-FH, yes-bronchodilators)

No family history of atopy and no bronchodilator use – hereon referred to as NoFHx NoAlb, (-FH, no-bronchodilators)

Next, for the subgroup analysis, patients with a positive respiratory viral panel (RVP) for RSV or rhinovirus were stratified based on bronchodilator use to evaluate differences in ICU-LOS, ICU-LRS, and hospital LOS. As RSV status is already incorporated into the CBS prediction model, comparisons were made between the two groups in predicted ICU-LOS and ICU-LRS. For rhinovirus-positive patients, patients were stratified by bronchodilator use, and differences in outcomes were assessed independently. We hypothesized that bronchodilator use may be associated with shorter ICU and hospital LOS and reduced ICU-LRS in patients with RSV or rhinovirus bronchiolitis.

Finally, a post hoc exploratory analysis was performed in patients born at <37 weeks' gestation. Outcomes (ICU LOS, hospital LOS) were then compared between the bronchodilator and no-bronchodilator groups. Given the small number of premature patients in the no-bronchodilator group (n = 7), observed ICU and hospital LOS were descriptively compared between groups.

Data Collection

Subjects were identified using ICD codes and the EMR problem list. Data were extracted from medical records through individual chart reviews. Collected variables included demographics, medical and surgical history, home-oxygen use, illness- day- at presentation, month and year of presentation, viral infection status, ICU-LOS, hospital LOS, type and duration of respiratory support, steroid administration, and in-patient bronchodilator use (intermittent or continuous) during the index bronchiolitis admission. Illness day-at-presentation was determined from the symptom onset documented in the EMR.

A family history of atopy in a first-degree relative was also recorded. A positive diagnosis of atopy was defined by the presence of one or more of the following conditions in a first-degree family relative: 1) asthma, 2) allergic rhinitis, and/or 3) eczema. The presence of these diagnoses was determined through a review of the patient's problem list and documentation in the EMR.

For the CBS calculation, additional variables at 12 hours after ICU admission included the highest respiratory rate, the highest heart rate, the highest temperature, the worst GCS, the lowest serum bicarbonate, and the lowest pH/highest pCO2 ratio. If intubated, the highest BUN and lowest systolic blood pressure were also recorded. A list of collected variables for data analysis is provided in eTable 1.

Statistical Analysis

An a priori target sample size of 97 patients was calculated to achieve a power of 0.8 with an effect size of 2 days and an alpha value of 0.05. Fisher’s Exact Test was used to assess differences in demographic characteristics between the two groups.

Given the non-parametric nature of the variables, differences in ICU/hospital LOS and ICU-LRS with bronchodilator use were assessed using the Mann-Whitney U test. For the secondary analysis, differences in outcomes when stratified by family history of atopy and bronchodilator use were analyzed using the Kruskal-Wallis test. Post-hoc Wilcoxon pairwise tests were performed on variables with significant differences in the Kruskal-Wallis test. All analyses used GraphPad Prism version 10.3.0 (461) (GraphPad Software, LLC, 2024; www.graphpad.com).

Results

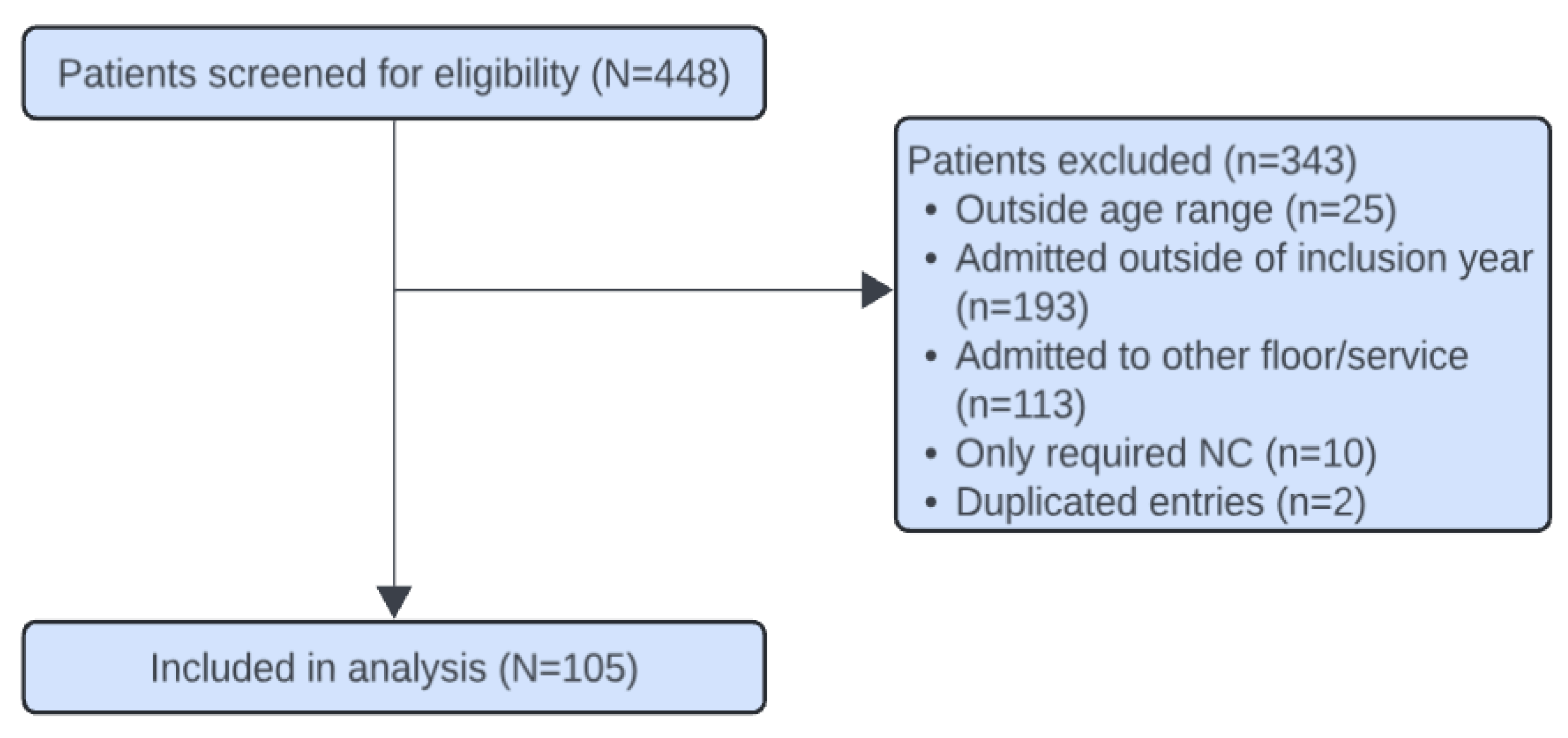

Among the 448 patients screened, 105 were included. Given the granularity of the data, we used a manual screening process via individual chart review to ensure accurate inclusion. A total of 343 patients were excluded: 25 (7.2%) were older than the inclusion age, 193 (57.4%) were admitted outside the inclusion year, 113 (33.6%) were admitted to the general pediatric floor, 10 (3%) required only nasal cannula for respiratory support, and 2 (0.6%) had duplicate entries [

Figure 2].

Of the 105 patients included, 56 (53.3%) received bronchodilators. The demographic characteristics of the groups are listed in

Table 1.

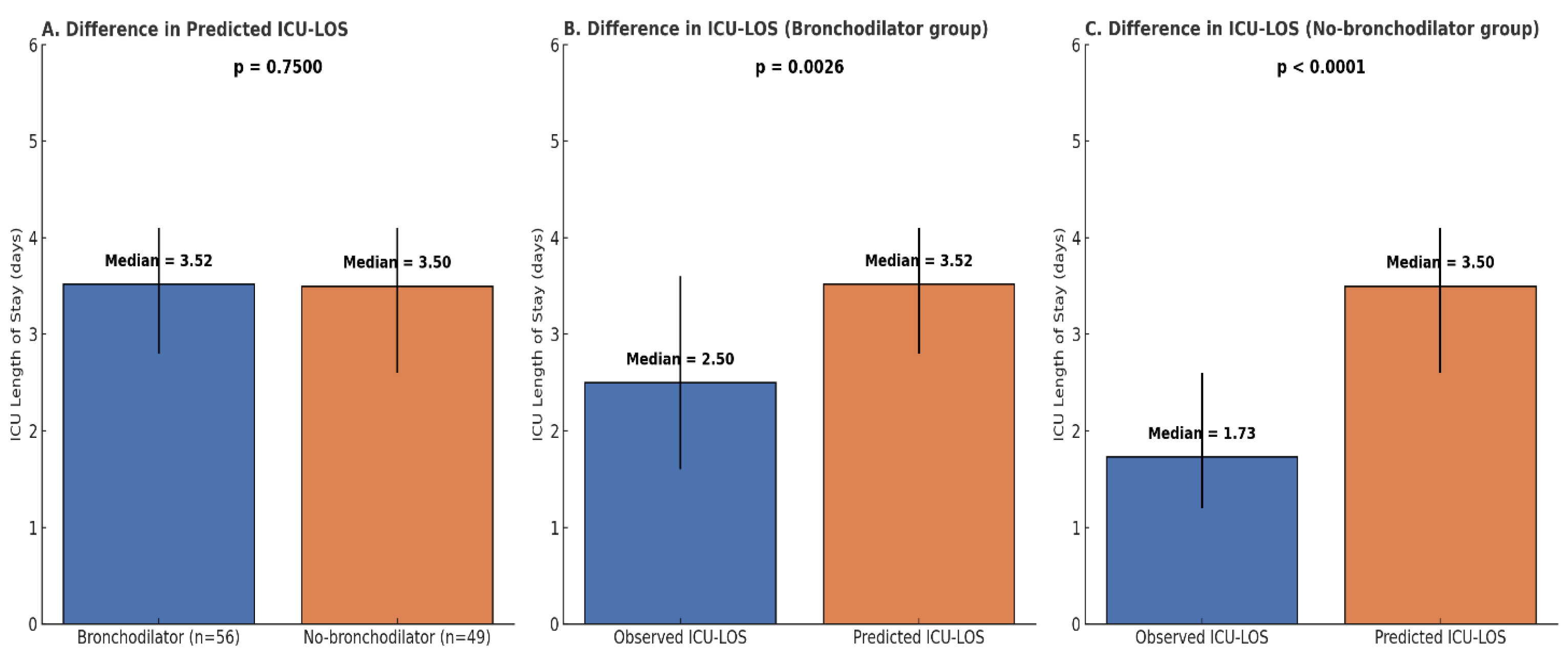

The no-bronchodilator group had a significantly shorter median observed ICU-LOS of 1.73 days (IQR: 1.2–2.6) compared to 2.53 days (IQR: 1.9-3.6) in the bronchodilator group (p=0.00052). Similarly, the median hospital LOS was shorter in the no-bronchodilator group of 2.14 days (IQR: 1.4–3.4) compared to 3.4 days (IQR: 2.3–4.8) in the bronchodilator group (p=0.0038) [

Figure 3].

The median observed ICU-LRS was similar between the bronchodilator (2.26 days, IQR: 1.3–3.3) and no-bronchodilator group (1.47 days, IQR: 1.2–2.5), without a significant difference (p = 0.058) [eFigure 1]. Only 4 patients were intubated (3.8% of the sample): 3 patients (75%) in the bronchodilator group and 1 patient (25%) in the no-bronchodilator group.

When comparing observed ICU-LOS to predicted ICU-LOS, both the bronchodilator and no-bronchodilator groups had a shorter observed ICU-LOS than predicted (p = 0.0026 and p < 0.0001, respectively) [

Figure 4]. The predicted ICU-LOS was comparable between the bronchodilator and no-bronchodilator groups, with median values of 3.52 days (IQR: 2.8–4.1) and 3.5 days (IQR: 2.6–4.1), respectively (p =0.75).

The secondary analysis, which explored differences in ICU and hospital LOS when patients were stratified based on family history of atopy and bronchodilator use, identified a significant difference in both observed ICU and hospital LOS between the four subgroups (p = 0.006 and p = 0.02, respectively). For the subgroup with a family history of atopy and bronchodilator use, the median ICU-LOS was 2 days (IQR: 1-3). In contrast, the subgroup with a family history of atopy without bronchodilator use had a median ICU-LOS of 1 day (IQR: 1–2) [

Table 2]. There were no differences in the duration of HFNC or NIMV among the four subgroups (p = 0.75 and p = 0.15, respectively) [eFigure 2].

Post-hoc analysis revealed that among patients without a family history of atopy, those managed without bronchodilators had a shorter observed ICU-LOS (p = 0.015). There was no significant difference in hospital LOS between the four subgroups [eTable 2].

In rhinovirus-positive patients, ICU and hospital LOS were significantly shorter in the no-bronchodilator group. The median ICU-LOS was 1.62 days (IQR: 1.2–2) compared to 2.33 days (IQR: 1.7–3.5) in the bronchodilator group (p = 0.008), while the median hospital LOS was 1.63 days (IQR: 1.2–2.3) versus 2.82 days (IQR: 2.02–4.12) in the bronchodilator group (p = 0.0077). However, no significant difference in ICU-LRS was observed between the groups (p = 0.081) [eFigure 3].

RSV positivity is a component of the Critical Bronchiolitis Score and was therefore not analyzed separately. Patients were stratified by bronchodilator use, and predicted outcomes were compared between groups. There were no significant differences in predicted ICU-LOS or ICU-LRS between the bronchodilator and no-bronchodilator groups (p =0.75 and p = 0.60, respectively) [eFigure 4].

A post-hoc exploratory subgroup analysis was performed among premature patients (born <37 weeks’ gestation). Median ICU-LOS was 3.0 days (IQR: 2.4–6.4) in the bronchodilator group and 2.0 days (IQR: 1.2–2.4) in the no-bronchodilator group, while median hospital LOS was 3.9 days (IQR: 2.9–7.0) and 2.0 days (IQR: 1.2–2.4), respectively [eFigure5].

Discussion:

This retrospective study, to the authors’ knowledge, is the first to examine the association between bronchodilator use in bronchiolitis and ICU length of stay using a validated metric for predicted ICU-LOS (i.e., the CBS) as a surrogate for illness severity [

13]. The CBS, as a disease-specific stratification method, has begun to be used in outcome-associated research [

14]. The decision to use bronchodilators in the PICU often arises from the fact that AAP guidelines excluded critically ill patients. Our findings suggest that family history alone, independent of predicted ICU-LOS, may not be a reliable predictor of an associated response to albuterol in bronchiolitis.

Interestingly, despite strong AAP recommendations, albuterol was still used in over half (53.3%) of our cohort, and these patients had longer inpatient stays [

3]. Evidence suggests that this is not an anomaly unique to this institution; studies have shown that a prolonged admission period (>1.5 days) is independently associated with albuterol prescription [

15,

16,

17]. In our study, the predicted ICU-LOS did not differ between groups, suggesting that illness severity is unlikely to explain the observed differences in LOS. It is possible that clinicians encountering atypical presentations of bronchiolitis are more likely to trial albuterol or consider other diagnoses, such as reactive airway disease, which could influence recovery trajectories due to inherent differences in lung physiology. Alternatively, reverse causality is also possible, wherein longer ICU stays and more complex cases prompted albuterol prescription, rather than resulting from it.

While the AAP guidelines acknowledge that a subset of children may benefit from bronchodilators, they do not define this population. Our subgroup analysis attempted to refine this by stratifying patients by family history of atopy. Although initial stratification suggested differences in hospital and ICU-LOS, post-hoc analysis did not confirm statistical significance. Surprisingly, patients without a family history of atopy who were managed without bronchodilators had shorter ICU-LOS, indicating that family history alone may be insufficient to guide bronchodilator use.

Similarly, bronchiolitis patients with rhinovirus who were managed without bronchodilators had shorter admission stays, while no significant differences were observed in RSV cases. These observations differ from prior studies that have linked RSV and rhinovirus bronchiolitis to long-term asthma [

18,

19,

20,

21,

22]. Longitudinal follow-up is needed to identify which children in these subgroups may ultimately benefit from asthma-directed therapies. These findings also suggest that viral panel testing could play a role in guiding therapeutic decisions in critical bronchiolitis, though this requires prospective validation. In our exploratory subgroup analysis of premature patients, we had only 7 patients to comment on, but we noted a similar trend toward longer ICU and hospital LOS in the bronchodilator group. This is consistent with existing literature and is interesting, as it may reflect the clinical uncertainty surrounding bronchodilator use in premature patients, a population frequently encountered in the PICU [

23].

Levin et al. reported improved airway resistance with albuterol in intubated bronchiolitis cases; however, with only 4 (3.8%) intubated patients in our cohort, such comparisons are limited [

24]. Although not statistically significant, patients managed without bronchodilators trended toward a shorter ICU-LRS—a signal that may hold clinical relevance. These findings highlight the complexity of clinically assessing the impact of bronchodilators on lung architecture and airway resistance, an area that warrants further exploration in future research.

Both groups had ICU-LOS shorter than predicted, likely reflecting local ICU admission practices or regional variation in bronchiolitis presentation, rather than treatment effects. This study is limited by its retrospective, single-center design. While the CBS is a validated tool for estimating ICU-LOS, it does not include known variables associated with illness severity, such as increased work of breathing or co-infection with multiple viruses. Additionally, it also does not capture all the nuances of real-time clinical decision-making. However, it is a more appropriate way to adjust for illness severity in low-mortality diseases, such as bronchiolitis, where traditional ICU scores may be less applicable.

Due to sample size limitations, this study was not powered to perform multivariable regression to adjust for other potential confounding variables, such as older age, history of prematurity, history of bronchopulmonary dysplasia, corticosteroid administration, and other existing comorbidities. While our data highlight an essential signal, they do not establish causality. Future prospective studies should focus on adjusting for this to better understand which subsets of patients may benefit from bronchodilators in the ICU setting.

Conclusion

This study shows that bronchodilator use in critical bronchiolitis was prevalent and suggests an association with longer ICU and hospital LOS, even after adjusting for predicted illness severity. Additionally, our secondary analysis suggested that neither a family history of atopy nor positivity for RSV or rhinovirus affected bronchodilator outcomes. Future prospective research is needed to identify targeted subgroups of patients who may benefit from this therapy.

Abbreviations

PICU (pediatric intensive care unit), SDICU (step-down ICU) and PCTICU (pediatric cardiac ICU), ICU (intensive care unit), LOS (length of stay), CBS (critical bronchiolitis score), LRS (level of respiratory support), HR (heart rate), RR (respiratory rate), GCS (glasgow coma scale), pCO2 (carbon dioxide), SBP (systolic blood pressure), BUN (blood urea nitrogen), HFNC (high flow nasal cannula), NIMV (non-invasive mechanical ventilation), IMV (invasive mechanical ventilation), FHx Alb (Positive family history of atopy with bronchodilator use), FHx NoAlb (Positive family history of atopy without bronchodilator use), NoFHx Alb (No family history of atopy with bronchodilator use), NoFHx NoAlb (No family history of atopy and no bronchodilator use), IQR (Interquartile range), AAP (American Academy of Pediatrics), EMR (electronic medical record).

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at the website of this paper posted on Preprints.org.

Data Availability

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article/Supplementary Material. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author(s).

Author Contributions

Author contributions: T.S. had full access to all the data in the study and takes responsibility for the integrity of the data and the accuracy of the analysis, including, and especially, any adverse effects. T.S., R.D.G., H.C., and H.S.C.conceived and designed the study. T.S., R.D.G., H.C., and H.S.C. acquired, analyzed, and interpreted the data. All authors drafted the manuscript and revised it for intellectual content, approved the final manuscript, and agreed to be accountable for the accuracy and integrity of the work.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional review board

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, and approved by the Institutional Review Board of Loma Linda University Health (IRB #5220357, approved on 11/1/2022.

Informed consent

Patient consent was waived because this study was a retrospective chart review.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank the pediatric residents who helped with data collection: Arjun Jindal, and Tiffany Seik Ismail. Additionally, John Tan assisted with the statistical analysis. We also thank Mike Mount for his expertise and assistance with calculating the critical bronchiolitis score, and Steven Shein for his guidance on the application and interpretation of the Critical Bronchiolitis Score in our cohort.

References

- Mahant, S; Parkin, PC; Thavam, T; et al. Rates in bronchiolitis hospitalization, intensive care unit use, mortality, and costs from 2004 to 2018. JAMA Pediatr. 2022, 176(3), 270–279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pelletier, JH; Au, AK; Fuhrman, D; et al. Trends in Bronchiolitis ICU Admissions and Ventilation Practices: 2010–2019. Pediatrics 2021, 147(6), e2020039115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ralston, SL; Lieberthal, AS; Meissner, HC; et al. Clinical practice guideline: the diagnosis, management, and prevention of bronchiolitis. Pediatrics 2014, 134(5), e1474–e1502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gadomski, AM; Scribani, MB. Bronchodilators for bronchiolitis. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2014, 2014(6), CD001266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Condella, A; Mansbach, JM; Hasegawa, K; et al. Multicenter Study of Albuterol Use Among Infants Hospitalized with Bronchiolitis. West J Emerg Med. 2018, 19(3), 475–483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rodríguez-Martínez, CE; Nino, G; Castro-Rodriguez, JA; et al. For which infants with viral bronchiolitis could it be deemed appropriate to use albuterol, at least on a therapeutic trial basis? Allergol Immunopathol (Madr) 2021, 49(1), 153–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Florin, TA; Byczkowski, T; Ruddy, RM; et al. Variation in the management of infants hospitalized for bronchiolitis persists after the 2006 American Academy of Pediatrics bronchiolitis guidelines. J Pediatr. 2014, 165(4), 786–792.e1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gelbart, B; McSharry, B; Delzoppo, C; et al. Pragmatic randomized trial of corticosteroids and inhaled epinephrine for bronchiolitis in children in intensive care (DAB trial). J Pediatr. 2022, 244, 17–23.e1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chawes, BL; Poorisrisak, P; Johnston, SL; et al. Neonatal bronchial hyperresponsiveness precedes acute severe viral bronchiolitis in infants. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2012, 130(2), 354–361.e3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bisgaard, H; Jensen, SM; Bønnelykke, K. Interaction between asthma and lung function growth in early life. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2012, 185(11), 1183–1189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jartti, T; Mäkelä, MJ; Vanto, T; et al. The link between bronchiolitis and asthma. Infect Dis Clin North Am. 2005, 19(3), 667–689. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clouse, BJ; Jadcherla, SR; Slaughter, JL. Systematic review of inhaled bronchodilator and corticosteroid therapies in infants with bronchopulmonary dysplasia: implications and future directions. PLoS One 2016, 11(2), e0148188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mount, MC; Ji, X; Kattan, MW; et al. Derivation and Validation of the Critical Bronchiolitis Score for the PICU. Pediatr Crit Care Med. 2022, 23(1), e45–e54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sunderajan, T; Choi, DS; LaFerla, C; et al. Routine Chest X-Rays in Critical Bronchiolitis Do Not Improve Outcomes. J Clin Med. 2025, 14(21), 7810. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Del Vecchio, MT; Doerr, LE; Gaughan, JP. The Use of Albuterol in Young Infants Hospitalized with Acute RSV Bronchiolitis. Interdiscip Perspect Infect Dis. 2012, 2012, 585901. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Piña-Hincapie, SM; Sossa-Briceño, MP; Rodriguez-Martinez, CE. Predictors for the prescription of albuterol in infants hospitalized for viral bronchiolitis. Allergol Immunopathol (Madr) 2020, 48(5), 469–474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarmiento, L; Rojas-Soto, GE; Rodríguez-Martínez, CE. Predictors of Inappropriate Use of Diagnostic Tests and Management of Bronchiolitis. Biomed Res Int. 2017, 2017, 9730696. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Carroll, KN; Gebretsadik, T; Griffin, MR; et al. The severity-dependent relationship of infant bronchiolitis on the risk and morbidity of early childhood asthma. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2009, 123(5), 1055–1061.e1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rubner, FJ; Jackson, DJ; Evans, MD; et al. Early life rhinovirus wheezing, allergic sensitization, and asthma risk at adolescence. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2017, 139(2), 501–507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jartti, T; Gern, JE. Role of viral infections in the development and exacerbation of asthma in children. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2017, 140(4), 895–906. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bergroth, E; Aakula, M; Korppi, M; et al. Post-bronchiolitis Use of Asthma Medication: A Prospective 1-year Follow-up Study. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 2016, 35(4), 363–368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jartti, T; Korppi, M. Rhinovirus-induced bronchiolitis and asthma development. Pediatr Allergy Immunol. 2011, 22(4), 350–355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Van Hasselt, TJ; Webster, K; Gale, C; Draper, ES; Seaton, SE. Children born preterm admitted to paediatric intensive care for bronchiolitis: a systematic review and meta-analysis. BMC Pediatr. 2023, 23(1), 326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Levin, DL; Garg, A; Hall, LJ; et al. A prospective randomized controlled blinded study of three bronchodilators in infants with respiratory syncytial virus bronchiolitis on mechanical ventilation. Pediatr Crit Care Med. 2008, 9(6), 598–604. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Corneli, HM; Zorc, JJ; Mahajan, P; et al. A multicenter, randomized, controlled trial of dexamethasone for bronchiolitis. N Engl J Med. 2007, 357(4), 331–339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).