1. Introduction

Endometrial cancer represents one of the most frequently diagnosed gynecologic malignancies, and although many cases are detected at an early stage, disease recurrence and resistance to therapy continue to pose significant clinical challenges [

1,

2]. These challenges are not driven solely by genetic alterations but are also shaped by profound changes in cellular organization, including dysregulated cell-cycle control, altered cytoskeletal architecture, and disrupted mitochondrial homeostasis. Together, these alterations critically influence tumor behavior and treatment responsiveness [

2,

3].

Uncontrolled proliferation is a defining feature of malignant cells [

4]. In normal tissues, cell division is tightly regulated by growth factor–dependent signaling and checkpoint mechanisms, whereas cancer cells bypass these controls through aberrant receptor activation and downstream survival pathways [

4,

5]. Mitochondria play a central role in this adaptation. Beyond their bioenergetic function, mitochondria regulate reactive oxygen species production, calcium signaling, and stress-responsive pathways that directly influence proliferation, differentiation, and cell fate decisions [

6,

7]. Preservation of mitochondrial integrity therefore depends on coordinated quality-control mechanisms, including organelle turnover and adaptive stress responses [

8,

9].

In parallel with mitochondrial adaptations, the cytoskeleton, particularly the intermediate filament (IF) network, has emerged as a critical regulator of tumor cell behavior. Intermediate filaments are no longer viewed as static structural components; rather, they actively participate in signal transduction, mechanical resilience, intracellular organization, and cellular stress adaptation [

10,

11,

12,

13]. Aberrant expression and reorganization of keratins, vimentin, and nestin have been associated with tumor progression, invasiveness, and therapy resistance in multiple cancer types, including endometrial carcinoma [

10,

11,

12,

13,

14,

15]. Despite this growing recognition, the contribution of intermediate filaments to stress-induced organelle remodeling remains incompletely understood.

Lithium chloride (LiCl), a classical inhibitor of glycogen synthase kinase-3β (GSK-3β) [

16], has been reported to exert antiproliferative and cytotoxic effects in a variety of tumor models. These effects are frequently accompanied by mitochondrial stress, redox imbalance, and perturbation of cell-cycle regulators [

17,

18,

19]. However, substantial heterogeneity exists across studies with respect to LiCl concentration, exposure duration, and cellular context, complicating the distinction between adaptive stress responses and overt cytotoxicity [

19]. Moreover, how lithium-induced mitochondrial stress intersects with cytoskeletal remodeling processes, particularly within three-dimensional tumor architectures, remains largely unexplored.

Three-dimensional (3D) spheroid models provide an experimentally advantageous platform for addressing these questions, as they more closely recapitulate in vivo tumor features such as nutrient and oxygen gradients, cell–cell interactions, and differential drug penetration compared with conventional monolayer cultures [

20,

21]. Within this context, proliferative dynamics, mitochondrial integrity, and cytoskeletal organization can be examined under conditions that more closely reflect the structural complexity of solid tumors.

Although mitochondrial stress responses and quality-control mechanisms have been widely explored in cancer biology [

7,

9,

22,

23], the role of intermediate filament networks in shaping cellular responses to therapeutic or pharmacological stress remains poorly defined. In particular, the spatial and functional relationship between mitochondrial injury and intermediate filament remodeling under stress conditions has received limited attention. To date, no studies have directly examined whether LiCl exposure promotes intermediate filament accumulation or coordinated mitochondrial–cytoskeletal remodeling in endometrial cancer spheroids. Given the increasing recognition of IF proteins as both biomarkers and functional regulators of tumor behavior [

24,

25,

26,

27,

28,

29], addressing this gap is of particular relevance.

Accordingly, the present study investigates the dose- and time-dependent effects of lithium chloride on proliferation, mitochondrial morphology, and intermediate filament organization in 3D Ishikawa endometrial cancer spheroids. By integrating viability and proliferation assays with detailed ultrastructural analysis, we aimed to characterize organelle-centered stress responses and cytoskeletal remodeling associated with lithium exposure, without presupposing specific cell-death mechanisms. Our findings reveal that lithium-induced mitochondrial injury is consistently accompanied by prominent intermediate filament remodeling, providing a descriptive structural framework for future mechanistic studies of mitochondrial–cytoskeletal interactions during stress adaptation in endometrial cancer.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Cell Culture and Lithium Chloride Exposure

The human endometrial adenocarcinoma cell line Ishikawa (ATCC® CRL-12051™, RRID:CVCL_2529) was maintained in RPMI-1640 medium supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum and 1% penicillin–streptomycin under standard culture conditions (37 °C, 5% CO₂, humidified atmosphere). Cells were routinely passaged at approximately 80% confluence using 0.25% trypsin–EDTA.

Lithium chloride (LiCl) was freshly dissolved in sterile distilled water and added to the culture medium at final concentrations of 1, 10, or 50 mM. These concentrations were selected based on previous in vitro studies reporting lithium-induced mitochondrial stress and autophagy-associated cellular responses in cancer models [

17,

18,

30]. Control cultures received vehicle alone. Although these concentrations exceed physiological serum lithium levels, short-term exposure to high LiCl doses is widely employed in vitro to interrogate mitochondrial and cytoskeletal stress phenotypes under controlled experimental conditions [

17].

2.2. Trypan Blue Exclusion Assay

Cell viability was assessed by Trypan Blue exclusion. Following LiCl treatment, cells were collected, mixed at a 1:1 ratio with 0.4% Trypan Blue solution, and counted manually using a Neubauer hemocytometer under light microscopy. For each replicate, four randomly selected microscopic fields were evaluated, typically comprising 200–400 cells per field. Cells excluding the dye were classified as viable, whereas blue-stained cells were considered non-viable. Experiments were performed using three independent biological replicates, each analyzed in technical duplicate.

2.3. Three-Dimensional Spheroid Generation

Multicellular spheroids were generated using a liquid-overlay technique. Six-well culture plates were coated with 3% Noble agar, and 1 × 10⁶ viable Ishikawa cells were seeded per well. Plates were incubated for 5–7 days to allow spheroid formation. Spheroids exhibiting uniform spherical morphology, intact architecture, and absence of central necrosis, as confirmed by phase-contrast microscopy, were selected for subsequent experiments. Spheroid diameters ranged between 120 and 300 µm. Selected spheroids were treated with LiCl at concentrations of 1, 10, or 50 mM for 24 or 72 h.

2.4. BrdU Proliferation Analysis in Spheroids

Proliferative activity within spheroids was assessed by bromodeoxyuridine (BrdU) incorporation. At the end of treatment, spheroids were fixed in neutral-buffered formalin, routinely processed, and embedded in paraffin. Sections (5 µm) were subjected to antigen retrieval in citrate buffer (pH 6.0) and incubated with an anti-BrdU antibody. Immunoreactivity was visualized using diaminobenzidine chromogen. BrdU-positive nuclei were quantified independently by two blinded histologists across ten randomly selected fields per spheroid. Results were expressed as the percentage of BrdU-positive nuclei relative to total nuclei. Only nuclei exhibiting clear, above-background DAB staining were scored as positive.

2.5. Monolayer Proliferation Assay

For two-dimensional proliferation analysis, Ishikawa cells were seeded at a density of 3 × 10⁵ cells per well and exposed to LiCl for 24 or 72 h. Following treatment, cells were harvested and counted using a hemocytometer. This assay was performed exclusively in monolayer cultures due to technical limitations associated with dissociation and accurate cell enumeration from spheroids. Experiments were conducted using three independent biological replicates with technical duplicates.

2.6. Colony Formation Assay

Clonogenic capacity was evaluated using a double-layer soft agar system. A base layer of 0.6% agar was prepared, followed by a top layer consisting of 0.3% agar containing 3000 viable cells and LiCl at final concentrations of 1, 10, or 50 mM. Plates were incubated for approximately 5 days, with slight variation depending on colony growth kinetics. Colonies containing at least 30 cells were counted under light microscopy. Colony formation efficiency was calculated as the number of colonies formed per 3000 seeded cells.

2.7. Transmission Electron Microscopy (TEM)

For ultrastructural evaluation, at least three spheroids per experimental condition were fixed in 2.5% glutaraldehyde and post-fixed with 1% osmium tetroxide. Samples were dehydrated through a graded acetone series and embedded in epoxy resin. Ultrathin sections (~70 nm) were prepared using an ultramicrotome, mounted on copper grids, and contrasted with uranyl acetate and lead citrate. Sections were examined using a JEOL JEM-1011 transmission electron microscope operating at 80 kV. Multiple sections and fields were analyzed per spheroid to ensure reproducibility of ultrastructural observations.

2.8. Statistical Analysis

Statistical analyses were performed using GraphPad Prism (version 9.0). Data are presented as mean ± standard deviation. Normality was evaluated using the Shapiro–Wilk test. Comparisons between two groups were conducted using Student’s t-test when appropriate, while experiments involving multiple variables were analyzed by two-way ANOVA followed by Tukey’s post hoc test. Adjusted p values < 0.05 were considered statistically significant. All experiments were performed with three biological replicates unless otherwise stated, and no data points were excluded from analysis.

2.9. Use of Generative Artificial Intelligence

Generative artificial intelligence (GenAI) tools were not used in the design of the study, data collection, data analysis, data interpretation, or preparation of the manuscript.

2.10. Ethical Approval

This study did not involve human participants or animal experiments; therefore, ethical approval was not required.

3. Results

Lithium chloride (LiCl) exposure induced marked, dose- and time-dependent alterations in the structural integrity of 3D Ishikawa endometrial cancer spheroids. As shown in

Figure 1A, untreated control spheroids maintained a compact, spherical morphology with smooth contours throughout the experimental period. In contrast, LiCl-treated spheroids exhibited progressive disruption of spheroid architecture, characterized by loss of compactness, surface irregularities, and diminished structural cohesion. These changes became more pronounced with increasing LiCl concentration and longer exposure duration, with the most extensive disruption observed in spheroids treated with 50 mM LiCl at both 24 and 72 h.

Consistent with these morphological observations, Trypan Blue exclusion analysis demonstrated a concentration- and time-dependent reduction in cell viability following LiCl treatment (

Figure 1B). At 24 h, a significant increase in non-viable cells was detected exclusively in the 50 mM LiCl group compared with untreated controls (p < 0.0001), whereas 1 mM and 10 mM treatments did not significantly affect viability. After 72 h, both 10 mM (p < 0.001) and 50 mM (p < 0.0001) LiCl exposures resulted in a marked decline in viable cell numbers, with the highest concentration producing the most pronounced effect.

Analysis of DNA synthesis by BrdU incorporation revealed a significant reduction in S-phase entry following LiCl exposure (

Figure 2). At 24 h, a decrease in the proportion of BrdU-positive nuclei was observed only in spheroids treated with 50 mM LiCl (p < 0.0001). After 72 h, both 10 mM and 50 mM LiCl treatments were associated with a substantial reduction in BrdU incorporation (p < 0.0001 for both), whereas no significant change was detected at 1 mM. These findings indicate a dose- and time-dependent suppression of proliferative activity in LiCl-treated 3D spheroids.

In parallel, total cell number was significantly reduced in a concentration- and duration-dependent manner (

Figure 3A). At 24 h, only spheroids treated with 50 mM LiCl showed a significant decrease in total cell count relative to controls (p < 0.0001). Following 72 h of exposure, both 10 mM and 50 mM LiCl treatments resulted in a pronounced reduction in total cell number (p < 0.0001), whereas spheroids exposed to 1 mM LiCl remained comparable to untreated controls at both time points. These data indicate that spheroid expansion is primarily impaired at higher lithium concentrations and prolonged exposure.

Clonogenic assays further demonstrated that LiCl exposure compromises long-term proliferative capacity in a dose-dependent manner (

Figure 3B). Even low-dose LiCl treatment (1 mM) resulted in a modest but statistically significant reduction in colony number (p < 0.05). More pronounced suppression of colony formation efficiency was observed following exposure to 10 mM and 50 mM LiCl (p < 0.0001), indicating a sustained impairment in the ability of Ishikawa cells to re-initiate proliferative growth following lithium exposure.

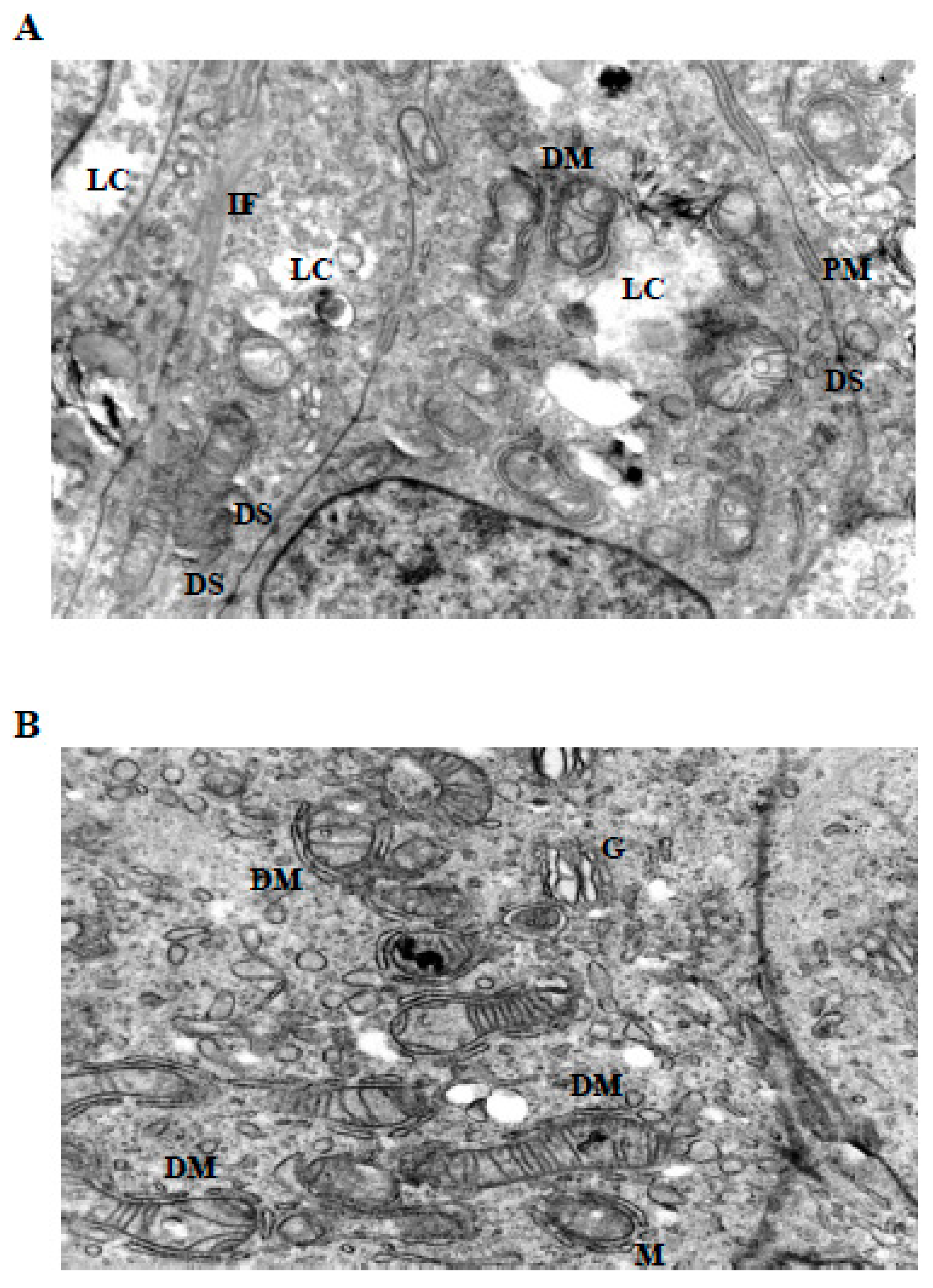

Ultrastructural analysis by transmission electron microscopy revealed distinct LiCl-induced alterations affecting mitochondrial morphology and intermediate filament organization in 3D Ishikawa endometrial cancer spheroids (

Figure 4,

Figure 5 and

Figure 6). Control spheroids displayed preserved cellular architecture, including mitochondria with intact outer and inner membranes, well-organized cristae, and homogeneous matrix density. The cytoplasm exhibited an organized intermediate filament network, intact plasma membranes, and preserved intercellular junctions (

Figure 4A).

Exposure to low-dose LiCl (1 mM) was associated with early mitochondrial alterations, including focal cristae irregularities and the appearance of double-membrane isolation-like structures in close proximity to mitochondria (

Figure 4B). These changes occurred without widespread cytoplasmic lysis, plasma membrane disruption, or global structural disorganization. At 72 h, low-dose LiCl treatment was characterized by an increased frequency of double-membrane structures and subtle mitochondrial matrix alterations (

Figure 5B), consistent with an early-stage mitochondrial stress response.

At moderate LiCl concentration (10 mM), mitochondria exhibited more pronounced ultrastructural abnormalities, including cristae depletion, mitochondrial swelling, and frequent double-membrane structures (

Figure 5A). Notably, these mitochondrial changes were accompanied by conspicuous accumulation and reorganization of intermediate filaments within the perimitochondrial cytoplasm. Despite these intracellular alterations, plasma membrane integrity and desmosomal junctions remained largely preserved. Prolonged exposure (72 h) further intensified mitochondrial disruption, intermediate filament accumulation, and the appearance of cytoplasmic lytic regions (

Figure 6A).

Cells exposed to high-dose LiCl (50 mM) displayed the most extensive ultrastructural damage (

Figure 6B). Mitochondria showed near-complete cristae loss, marked swelling, and severe disorganization of matrix architecture. Although double-membrane structures were present, their incomplete morphology suggested disrupted or inefficient isolation processes rather than effective organelle clearance. In addition to mitochondrial injury, prominent dilation of endoplasmic reticulum cisternae, diffuse cytoplasmic lysis, and pronounced intermediate filament disorganization were observed. Importantly, across all concentrations and time points examined, classical apoptotic ultrastructural features—such as chromatin condensation, nuclear fragmentation, or apoptotic body formation—were not detected, despite extensive organelle-level alterations.

4. Discussion

In this study, we examined the ultrastructural consequences of lithium chloride (LiCl) exposure in 3D Ishikawa endometrial cancer spheroids and identified a coordinated cellular stress response characterized by mitochondrial injury and prominent accumulation of intermediate filaments (IFs). These findings indicate that IF networks undergo substantial remodeling under lithium-induced stress and support the notion that cytoskeletal reorganization accompanies mitochondrial dysfunction within a three-dimensional tumor context.

Across multiple experimental endpoints, LiCl exposure exerted clear antiproliferative effects, including reduced cell viability, impaired clonogenic capacity, and decreased BrdU incorporation, particularly at concentrations of 10 mM and 50 mM. These observations are consistent with previous reports demonstrating that LiCl can disrupt proliferative signaling and cellular homeostasis in cancer models [

30]. However, as neither GSK3β activity nor apoptosis-associated molecular markers were directly assessed [

17,

18], the present study does not assign these effects to a specific signaling pathway. Importantly, despite marked reductions in spheroid viability and proliferative capacity, classical ultrastructural hallmarks of apoptosis, such as chromatin condensation, nuclear fragmentation, or apoptotic body formation, were not observed. This pattern suggests that LiCl-induced growth suppression occurs predominantly within a non-apoptotic cellular stress framework rather than through canonical apoptotic execution.

Ultrastructural analyses provided further insight into the nature of this stress response. LiCl-treated spheroids displayed mitochondria with cristae disruption, swelling, and altered matrix organization, frequently accompanied by membrane-associated structures in their vicinity. Such morphological features are commonly interpreted as indicators of mitochondrial stress and engagement of quality-control or adaptive responses, rather than definitive evidence of effective organelle clearance. The presence of these changes even at low LiCl concentrations (1 mM) suggests that lithium can elicit early mitochondrial remodeling under sub-cytotoxic conditions, in agreement with prior ultrastructural studies in cancer models [

17,

18,

30,

31]. At higher concentrations, the progression toward extensive cristae loss and mitochondrial swelling likely reflects a breakdown of adaptive capacity and escalating organelle dysfunction.

A particularly notable observation in this study is the consistent accumulation and reorganization of intermediate filaments in close spatial association with stressed mitochondria, most prominently at 10 mM and 50 mM LiCl. This perimitochondrial enrichment of IFs suggests that cytoskeletal remodeling is not merely a secondary consequence of cellular damage but may represent a coordinated component of the stress response. Intermediate filament proteins are increasingly recognized as dynamic regulators of intracellular organization, signaling, and mechanical stability, and have been implicated in cellular adaptation to metabolic and therapeutic stress [

10,

11,

12,

13,

24,

28,

29,

32,

33]. The spatial convergence of mitochondrial injury and IF accumulation observed here supports the concept of functional crosstalk between organelle stress and cytoskeletal architecture. In this context, intermediate filament remodeling may be interpreted as part of a broader adaptive restructuring process that accompanies mitochondrial stress rather than as a passive byproduct of cellular injury.

Dose-dependent differences further underscore this relationship. While low-dose LiCl primarily induced subtle mitochondrial alterations with limited IF rearrangement, exposure to 10 mM LiCl produced pronounced mitochondrial injury together with dense IF accumulation, suggesting a coordinated mitochondrial–cytoskeletal stress phenotype. At 50 mM, extensive mitochondrial disorganization, dilation of endoplasmic reticulum cisternae, cytoplasmic lytic changes, and marked IF network disruption were observed. Notably, despite severe intracellular alterations, plasma membrane integrity and desmosomal junctions were largely preserved, indicating that LiCl-induced injury may remain compartmentalized at the organelle and cytoskeletal levels before loss of overall membrane integrity. Comparable compartmentalized stress patterns have been described in models of severe mitochondrial dysfunction, in which organelle damage precedes overt membrane rupture [

7,

34].

Although IF accumulation was a consistent feature across LiCl-treated spheroids, the present study does not distinguish between specific intermediate filament subtypes. Consequently, whether vimentin, keratin 17/19, nestin, or other IF systems selectively contribute to the observed phenotype cannot be determined. Likewise, molecular markers of mitochondrial quality control or autophagy-related pathways were not assessed. Therefore, the findings should be interpreted as ultrastructural evidence of cytoskeletal remodeling associated with organelle-centered stress, rather than as mechanistic proof of defined degradation or cell death pathways. Future studies integrating immunofluorescence, immunoblotting, transcript-level analyses, and functional perturbation of IF networks will be essential to clarify whether IF accumulation reflects adaptive remodeling, impaired turnover, or active participation in stress signaling [

10,

11,

12,

13,

27,

28,

29,

32].

Collectively, these observations indicate that LiCl induces a complex cellular stress state in which mitochondrial dysfunction and cytoskeletal reorganization emerge concurrently. The prominent involvement of intermediate filaments highlights their potential role as integrators of structural and metabolic stress, emphasizing mitochondrial–cytoskeletal interactions as an underexplored dimension of lithium-induced cellular responses in endometrial cancer models and a promising direction for future investigation.

5. Conclusions

In summary, this study provides a detailed ultrastructural characterization of lithium chloride–induced cellular stress in three-dimensional endometrial cancer spheroids. Using transmission electron microscopy in combination with phenotypic assays, we demonstrate that LiCl exposure is associated with pronounced mitochondrial alterations and intermediate filament remodeling in the absence of classical apoptotic morphology. While the present conclusions are derived from ultrastructural observations rather than molecular interrogation, they reveal a coordinated organelle-centered and cytoskeletal stress response that extends beyond mitochondrial injury alone. By identifying intermediate filament accumulation as a prominent structural feature of lithium-induced stress in a 3D tumor model, this work establishes a framework for future mechanistic studies aimed at elucidating mitochondrial–cytoskeletal interactions and their relevance to stress adaptation in endometrial cancer.

Author Contributions

B.Y. performed data analysis and drafted the initial version of the manuscript. B.B. contributed to figure preparation and assisted in manuscript editing. M.H.K. supported the experimental design and contributed to manuscript revisions. A.B. conceptualized and designed the study, supervised the entire project, ensured scientific accuracy, and finalized the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The data supporting the findings of this study are included in the manuscript and its figures. Additional data are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest. The funders had no role in the design of the study; in the collection, analyses, or interpretation of data; in the writing of the manuscript; or in the decision to publish the results.:.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| LiCl |

Lithium chloride |

| IF |

Intermediate filament |

| TEM |

Transmission electron microscopy |

References

- Siegel, R.L.; Miller, K.D.; Jemal, A. Cancer Statistics, 2015. CA Cancer J Clin 2015, 65, 5–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Skok, K.; Maver, U.; Gradišnik, L.; Kozar, N.; Takač, I.; Arko, D. Endometrial Cancer and Its Cell Lines. Mol Biol Rep 2020, 47, 1399–1411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tran, A.-Q.; Gehrig, P. Recent Advances in Endometrial Cancer. F1000Res 2017, 6, 81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hanahan, D.; Weinberg, R.A. Hallmarks of Cancer: The Next Generation. Cell 2011, 144, 646–674. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tufail, M.; Hu, J.-J.; Liang, J.; He, C.-Y.; Wan, W.-D.; Huang, Y.-Q.; Jiang, C.-H.; Wu, H.; Li, N. Hallmarks of Cancer Resistance. iScience 2024, 27, 109979. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martínez-Reyes, I.; Chandel, N.S. Mitochondrial TCA Cycle Metabolites Control Physiology and Disease. Nat Commun 2020, 11, 102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wallace, D.C. Mitochondria and Cancer. Nat Rev Cancer 2012, 12, 685–698. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Glancy, B.; Kim, Y.; Katti, P.; Willingham, T.B. The Functional Impact of Mitochondrial Structure Across Subcellular Scales. Front Physiol 2020, 11, 541040. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- White, E.; Mehnert, J.M.; Chan, C.S. Autophagy, Metabolism, and Cancer. Clin Cancer Res 2015, 21, 5037–5046. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, P.; Alsharif, S.; Fallatah, A.; Chung, B.M. Intermediate Filaments as Effectors of Cancer Development and Metastasis: A Focus on Keratins, Vimentin, and Nestin. Cells 2019, 8, 497. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, S.; Coulombe, P.A. Intermediate Filament Scaffolds Fulfill Mechanical, Organizational, and Signaling Functions in the Cytoplasm. Genes Dev 2007, 21, 1581–1597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chung, B.-M.; Rotty, J.D.; Coulombe, P.A. Networking Galore: Intermediate Filaments and Cell Migration. Curr Opin Cell Biol 2013, 25, 600–612. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Etienne-Manneville, S. Cytoplasmic Intermediate Filaments in Cell Biology. Annu Rev Cell Dev Biol 2018, 34, 1–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moll, R.; Divo, M.; Langbein, L. The Human Keratins: Biology and Pathology. Histochem Cell Biol 2008, 129, 705–733. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oshima, R.G. Intermediate Filaments: A Historical Perspective. Exp Cell Res 2007, 313, 1981–1994. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beurel, E.; Kornprobst, M.; Blivet-Van Eggelpoël, M.-J.; Ruiz-Ruiz, C.; Cadoret, A.; Capeau, J.; Desbois-Mouthon, C. GSK-3beta Inhibition by Lithium Confers Resistance to Chemotherapy-Induced Apoptosis through the Repression of CD95 (Fas/APO-1) Expression. Exp Cell Res 2004, 300, 354–364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, H.; Zhang, Y.; Liang, J.; Wu, J.; Zhang, Y.; Su, H.; Zhang, Q.; Shen, Y.; Shen, S.; Wang, L.; et al. Lithium Chloride Induces Apoptosis by Activating Endoplasmic Reticulum Stress in Pancreatic Cancer. Transl Oncol 2023, 38, 101792. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Villegas-Vázquez, E.Y.; Quintas-Granados, L.I.; Cortés, H.; González-Del Carmen, M.; Leyva-Gómez, G.; Rodríguez-Morales, M.; Bustamante-Montes, L.P.; Silva-Adaya, D.; Pérez-Plasencia, C.; Jacobo-Herrera, N.; et al. Lithium: A Promising Anticancer Agent. Life (Basel) 2023, 13, 537. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, C.; Zhu, B.; Zhan, M.; Hua, Z.-C. Lithium in Cancer Therapy: Friend or Foe? Cancers 2023, 15, 1095. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tidwell, T.R.; Røsland, G.V.; Tronstad, K.J.; Søreide, K.; Hagland, H.R. Metabolic Flux Analysis of 3D Spheroids Reveals Significant Differences in Glucose Metabolism from Matched 2D Cultures of Colorectal Cancer and Pancreatic Ductal Adenocarcinoma Cell Lines. Cancer Metab 2022, 10, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weiswald, L.-B.; Bellet, D.; Dangles-Marie, V. Spherical Cancer Models in Tumor Biology. Neoplasia 2015, 17, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ling, Z.; Pan, J.; Zhang, Z.; Chen, G.; Geng, J.; Lin, Q.; Zhang, T.; Cao, S.; Chen, C.; Lin, J.; et al. Small-Molecule Molephantin Induces Apoptosis and Mitophagy Flux Blockage through ROS Production in Glioblastoma. Cancer Lett 2024, 592, 216927. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Wang, D. Mitophagy in Gynecological Malignancies: Roles, Advances, and Therapeutic Potential. Cell Death Discov. 2024, 10, 488. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, N.; Zhang, R.; Zou, K.; Yu, W.; Guo, W.; Gao, Y.; Li, J.; Li, M.; Tai, Y.; Huang, W.; et al. Keratin 23 Promotes Telomerase Reverse Transcriptase Expression and Human Colorectal Cancer Growth. Cell Death Dis 2017, 8, e2961. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, F.; Shen, Y.; Mohanasundaram, P.; Lindström, M.; Ivaska, J.; Ny, T.; Eriksson, J.E. Vimentin Coordinates Fibroblast Proliferation and Keratinocyte Differentiation in Wound Healing via TGF-β-Slug Signaling. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2016, 113, E4320-4327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhao, Z.; Lu, P.; Zhang, H.; Xu, H.; Gao, N.; Li, M.; Liu, C. Nestin Positively Regulates the Wnt/β-Catenin Pathway and the Proliferation, Survival and Invasiveness of Breast Cancer Stem Cells. Breast Cancer Res 2014, 16, 408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, B.; Antonyak, M.A.; Druso, J.E.; Cheng, L.; Nikitin, A.Y.; Cerione, R.A. EGF Potentiated Oncogenesis Requires a Tissue Transglutaminase-Dependent Signaling Pathway Leading to Src Activation. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2010, 107, 1408–1413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, J.; Zhuo, H.; Zhang, X.; Jiang, R.; Ji, J.; Deng, L.; Qian, X.; Zhang, F.; Sun, B. A Novel Biomarker Linc00974 Interacting with KRT19 Promotes Proliferation and Metastasis in Hepatocellular Carcinoma. Cell Death Dis 2014, 5, e1549. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Saha, S.K.; Choi, H.Y.; Kim, B.W.; Dayem, A.A.; Yang, G.-M.; Kim, K.S.; Yin, Y.F.; Cho, S.-G. KRT19 Directly Interacts with β-Catenin/RAC1 Complex to Regulate NUMB-Dependent NOTCH Signaling Pathway and Breast Cancer Properties. Oncogene 2017, 36, 332–349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Taskaeva, Y.S.; Bgatova, N.P.; Dossymbekova, R.S.; Solovieva, A.O.; Miroshnichenko, S.M.; Sharipov, K.O.; Tungushbaeva, Z.B. In Vitro Effects of Lithium Carbonate on Cell Cycle, Apoptosis, and Autophagy in Hepatocellular Carcinoma-29 Cells. Bull Exp Biol Med 2020, 170, 246–250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taskaeva, I.; Bgatova, N. Ultrastructural and Immunofluorescent Analysis of Lithium Effects on Autophagy in Hepatocellular Carcinoma Cells. Asian Pacific Journal of Cancer Biology 2018, 3, 83–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hemel, I.M.G.M.; Steen, C.; Denil, S.L.I.J.; Ertaylan, G.; Kutmon, M.; Adriaens, M.; Gerards, M. The Unusual Suspect: A Novel Role for Intermediate Filament Proteins in Mitochondrial Morphology. Mitochondrion 2025, 81, 102008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mohanasundaram, P.; Coelho-Rato, L.S.; Modi, M.K.; Urbanska, M.; Lautenschläger, F.; Cheng, F.; Eriksson, J.E. Cytoskeletal Vimentin Regulates Cell Size and Autophagy through mTORC1 Signaling. PLOS Biology 2022, 20, e3001737. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, X.; Xiong, X.; Wang, P.; Zhang, S.; Peng, D. SIRT1-Mediated Deacetylation of FOXO3 Enhances Mitophagy and Drives Hormone Resistance in Endometrial Cancer. Mol Med 2024, 30, 147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Figure 1.

Effects of lithium chloride on spheroid morphology and cell viability. (A) Representative bright-field images of 3D Ishikawa spheroids (10X). Control spheroids show compact and well-defined architecture, whereas LiCl exposure results in progressive structural disruption in a dose-dependent manner. (B) Trypan Blue exclusion assay quantifying viable and non-viable cells after LiCl treatment. Data are presented as mean ± SD (n = 3). Statistical significance: *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001, ****p < 0.0001.

Figure 1.

Effects of lithium chloride on spheroid morphology and cell viability. (A) Representative bright-field images of 3D Ishikawa spheroids (10X). Control spheroids show compact and well-defined architecture, whereas LiCl exposure results in progressive structural disruption in a dose-dependent manner. (B) Trypan Blue exclusion assay quantifying viable and non-viable cells after LiCl treatment. Data are presented as mean ± SD (n = 3). Statistical significance: *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001, ****p < 0.0001.

Figure 2.

BrdU incorporation analysis in LiCl-treated 3D endometrial cancer spheroids. Ishikawa spheroids were treated with 1, 10, or 50 mM LiCl for 24 or 72 hours and stained for BrdU to identify cells undergoing DNA synthesis. BrdU-positive nuclei appear brown in paraffin sections. Quantification was performed by counting labeled and unlabeled nuclei in randomly selected fields (10 sections per group). Data are presented as mean ± SD. Statistical significance: *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001, ****p < 0.0001.

Figure 2.

BrdU incorporation analysis in LiCl-treated 3D endometrial cancer spheroids. Ishikawa spheroids were treated with 1, 10, or 50 mM LiCl for 24 or 72 hours and stained for BrdU to identify cells undergoing DNA synthesis. BrdU-positive nuclei appear brown in paraffin sections. Quantification was performed by counting labeled and unlabeled nuclei in randomly selected fields (10 sections per group). Data are presented as mean ± SD. Statistical significance: *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001, ****p < 0.0001.

Figure 3.

LiCl suppresses total cell number and clonogenic potential in Ishikawa spheroids. (A) Following LiCl treatment (1, 10, or 50 mM; 24 or 72 h), spheroids were dissociated and total cell number was quantified using a hemocytometer. (B) Clonogenic capacity was evaluated using a soft agar assay. Colonies containing ≥30 cells were counted after 6 days. Data are presented as mean ± SD from three independent experiments. Statistical significance: *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001, ****p < 0.0001.

Figure 3.

LiCl suppresses total cell number and clonogenic potential in Ishikawa spheroids. (A) Following LiCl treatment (1, 10, or 50 mM; 24 or 72 h), spheroids were dissociated and total cell number was quantified using a hemocytometer. (B) Clonogenic capacity was evaluated using a soft agar assay. Colonies containing ≥30 cells were counted after 6 days. Data are presented as mean ± SD from three independent experiments. Statistical significance: *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001, ****p < 0.0001.

Figure 4.

Ultrastructural changes in Ishikawa spheroids following low-dose LiCl exposure (24 h). (A) Control spheroids display preserved mitochondrial morphology with intact cristae, organized cytoplasm, and normal plasma membrane integrity. (B) Treatment with 1 mM LiCl reveals early mitochondrial alterations, including focal cristae irregularities and double-membrane (DM) isolation structures, accompanied by mild cytoplasmic vacuolization and localized intermediate filament (IF) accumulation. Abbreviations: M, mitochondrion; N, nucleus; G, Golgi apparatus; PM, plasma membrane; DM, double membrane; IF, intermediate filament; DS, desmosome; V, vacuole; LC, lytic cytoplasm. Scale bar: 500 nm.

Figure 4.

Ultrastructural changes in Ishikawa spheroids following low-dose LiCl exposure (24 h). (A) Control spheroids display preserved mitochondrial morphology with intact cristae, organized cytoplasm, and normal plasma membrane integrity. (B) Treatment with 1 mM LiCl reveals early mitochondrial alterations, including focal cristae irregularities and double-membrane (DM) isolation structures, accompanied by mild cytoplasmic vacuolization and localized intermediate filament (IF) accumulation. Abbreviations: M, mitochondrion; N, nucleus; G, Golgi apparatus; PM, plasma membrane; DM, double membrane; IF, intermediate filament; DS, desmosome; V, vacuole; LC, lytic cytoplasm. Scale bar: 500 nm.

Figure 5.

Mitochondrial and cytoskeletal alterations following moderate LiCl exposure. (A) At 10 mM LiCl (24 h), mitochondria exhibit pronounced cristae loss, swelling, and frequent DM structures, accompanied by cytoplasmic lysis (LC) and marked IF accumulation. Desmosomal junctions (DS) remain preserved. (B) At 1 mM LiCl (72 h), mitochondria display early structural injury with initial cristae disruption and DM formation, consistent with early-stage mitochondrial stress responses. Abbreviations: M, mitochondrion; N, nucleus; G, Golgi apparatus; PM, plasma membrane; DM, double membrane; IF, intermediate filament; DS, desmosome; V, vacuole; LC, lytic cytoplasm. Scale bar: 500 nm.

Figure 5.

Mitochondrial and cytoskeletal alterations following moderate LiCl exposure. (A) At 10 mM LiCl (24 h), mitochondria exhibit pronounced cristae loss, swelling, and frequent DM structures, accompanied by cytoplasmic lysis (LC) and marked IF accumulation. Desmosomal junctions (DS) remain preserved. (B) At 1 mM LiCl (72 h), mitochondria display early structural injury with initial cristae disruption and DM formation, consistent with early-stage mitochondrial stress responses. Abbreviations: M, mitochondrion; N, nucleus; G, Golgi apparatus; PM, plasma membrane; DM, double membrane; IF, intermediate filament; DS, desmosome; V, vacuole; LC, lytic cytoplasm. Scale bar: 500 nm.

Figure 6.

Severe mitochondrial and cytoskeletal disruption induced by prolonged or high-dose LiCl exposure. (A) At 10 mM LiCl (72 h), mitochondria show extensive cristae disruption, dense IF accumulation, and increased cytoplasmic lysis, indicating enhanced organelle-centered stress. (B) Treatment with 50 mM LiCl results in profound mitochondrial swelling, near-complete cristae loss, and incomplete DM structures, accompanied by dilated endoplasmic reticulum (ER), IF disorganization, and widespread cytoplasmic lysis. Plasma membrane integrity remains largely preserved. Abbreviations: M, mitochondrion; DM, double membrane; IF, intermediate filament; ER, endoplasmic reticulum; PM, plasma membrane; LC, lytic cytoplasm; DS, desmosome; G, Golgi apparatus. Scale bar: 500 nm.

Figure 6.

Severe mitochondrial and cytoskeletal disruption induced by prolonged or high-dose LiCl exposure. (A) At 10 mM LiCl (72 h), mitochondria show extensive cristae disruption, dense IF accumulation, and increased cytoplasmic lysis, indicating enhanced organelle-centered stress. (B) Treatment with 50 mM LiCl results in profound mitochondrial swelling, near-complete cristae loss, and incomplete DM structures, accompanied by dilated endoplasmic reticulum (ER), IF disorganization, and widespread cytoplasmic lysis. Plasma membrane integrity remains largely preserved. Abbreviations: M, mitochondrion; DM, double membrane; IF, intermediate filament; ER, endoplasmic reticulum; PM, plasma membrane; LC, lytic cytoplasm; DS, desmosome; G, Golgi apparatus. Scale bar: 500 nm.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |