1. Introduction

It should be noted that one of the most important threats to the favourable status of world biodiversity is the increasing, human-induced impact on ecological connectivity [

1]. The critical cumulative value of the negative impact has been recognized as an "barrier effect” [

2]. The question is why, taking into account the contemporary knowledge and practical experience, especially in the field of ecology and legal science, the “barrier effect” is still increasing.

At the beginning , the authors would like to confirm that it is obvious that the individual disciplines of environmental science are continuously developing as regards wide range of improvements. Starting from engineering solutions [

3], elaboration of unprecedented impact assessment techniques [

4], monitoring methods [

5] ending for example with multifunctional databases [

6,

7]. However, in fact all of these scientific achievements may be of no added value because of two circumstances. First, it must be noted that the “science in practice” approach requires that the effects of R&D projects are properly integrated with existing or planned legal schemes. The second condition of effective nature protection concerns the overall coherency of legal schemes and policies. As for the non-lawyers the authors would like to explain in this section that the Strategic Environmental Assessment – (SEA) and Environmental Impact Assessment (EIA) reports are being verified in the context of formal and substantive requirements. The second group includes i.a. provisions on nature quality standards . In case of proceedings concerning plans or projects significantly affecting ecological connectivity, the environmental authorities will assess i.e. the methods of nature inventory, species distribution models [

8], the legal consequences of predictions on negative impact indicator [

9] as well as the technical and economic feasibility of alternative solutions. If the substantive requirements are met, the proposed plan or project will be proceeded under certain conditions. The authorisation of the strategic document or the development consent shall include clear and precise obligations, especially regarding mitigation, compensatory and monitoring measures [

10,

11].

In case of inadequate transposition of innovatory methods and techniques into appropriate legal instruments disintegration of sciences will arise at the stage of application of law. On the other hand even if the scientific improvements are fully consolidated with nature protection regulatory framework their efficiency will be much lower or even annulled in case of collision of laws or policies. Finally it must be noted that all the mentioned analytical, legal and political dimensions bidirectionally determine the possible space for enhancing vertical and horizontal cooperation.

2. Materials and Methods

The one important question the authors would like to ask in this place is if the decision-makers are able to execute policies without regular scientific and practitioner support? In this context the necessity of finding the “common language” becomes much more important. In order to benefit from the essence of this article as far as possible, all the stakeholders must be familiar with the multistage law-making and its application scheme [see Figure no 1]. After acquiring this knowledge, it will be much easier for the audience to find the relevant context of the subsequent sections of the article.

Figure 1.

Nature protection law-making and application. Vertical and Horizontal cooperation sheme.

Figure 1.

Nature protection law-making and application. Vertical and Horizontal cooperation sheme.

Theoretically, there are two methods that may be used in order to justify the authors’ thesis. The first one assumes a review of existing literature and elaboration of suitable conclusions. However, this approach is not feasible because of the original profile of the adopted narration. The second approach assumes designation of pragmatic objectives the authors intend to achieve. The proposed approach is also, as far as possible, scientifically based, but the main method still remains unprecedented. Because of the need for strengthening the awareness of importance of discussed topics the conclusions of two recent scientific reports are especially worth citing.

The first one have been presented as a result of legal indicator-based analysis elaborated by experts of International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN). The final report underlines that the Multilateral Environmental Agreements are neither efficient nor effective [

12]. This statement has been confirmed by the first ever report on the implementation of the Convention on Protection of Migratory Species [

13]. The report underlines that forty years after the CMS came into force, the overall conservation status of protected species is still deteriorating [

14,

15].

In the light of the initial assumptions of the article, the above conclusions must be considered as a ‘nexus’. The first one within the “human dimension” and the second one in ecological. However the supreme pragmatic results expected by the authors concern the primary “causative factors” which should be closer to interdisciplinary human communication. That is the reason for the proposal on empirical method, which consists of two sketches. Taking into account the positive scenario both sketches shall enter the “viral” discussion. That’s why the authors would like to underline that the article will bring measurable and continuous effects in case of development of similar plays during everyday practice (without exaggeration).

The Results section is organised into two sketches, each representing one operationalised application of the above method. A sketch is not a case study in the empirical sense; it is a bounded interdisciplinary scenario designed to: select a concrete conceptual tension; anchor it in the relevant normative and interpretative framework and translate its consequences into operational “lessons learnt” for SEA/EIA practice and for the protection of ecological connectivity.

Each sketch follows the same internal structure: (1) core of the sketch, defining the focal interconnection; (2) legal background, mapping the normative setting and interpretative sources; (3) a critical point of disintegration (misunderstanding or a procedural/normative gap) showing how the barrier effect accumulates in practice; and (4) lessons learnt, formulating transferable outcomes for interdisciplinary cooperation and decision-making. The material used within the sketches consists of binding legal acts, official guidance and soft-law instruments adopted under relevant international and EU frameworks, complemented by jurisprudence and scientific literature. In this sense, sketches function as a methodological bridge: they build a shared language between disciplines and expose where the “quantity” of regulation does not guarantee the “quality” of nature protection.

As regards section “discussion” the presented model of cooperation has been dedicated mainly (but not entirely) to the law-making stage. Next in the light of proposed model, the discussion has been focused on the one of the most up to date topics regarding application of law stage. The effects of the discussion should bring the added value in the form of conclusions of “science in practice” nature. The conclusions must guarantee adequate solutions so as to immediate face the challenge concerning transboundary impact of wind farms developments on migratory bird species.

3. Results

3.1. Sketch no 1 - Coherency of ecological networks v. “Coherency of law” principle

3.1.1. Core of the sketch

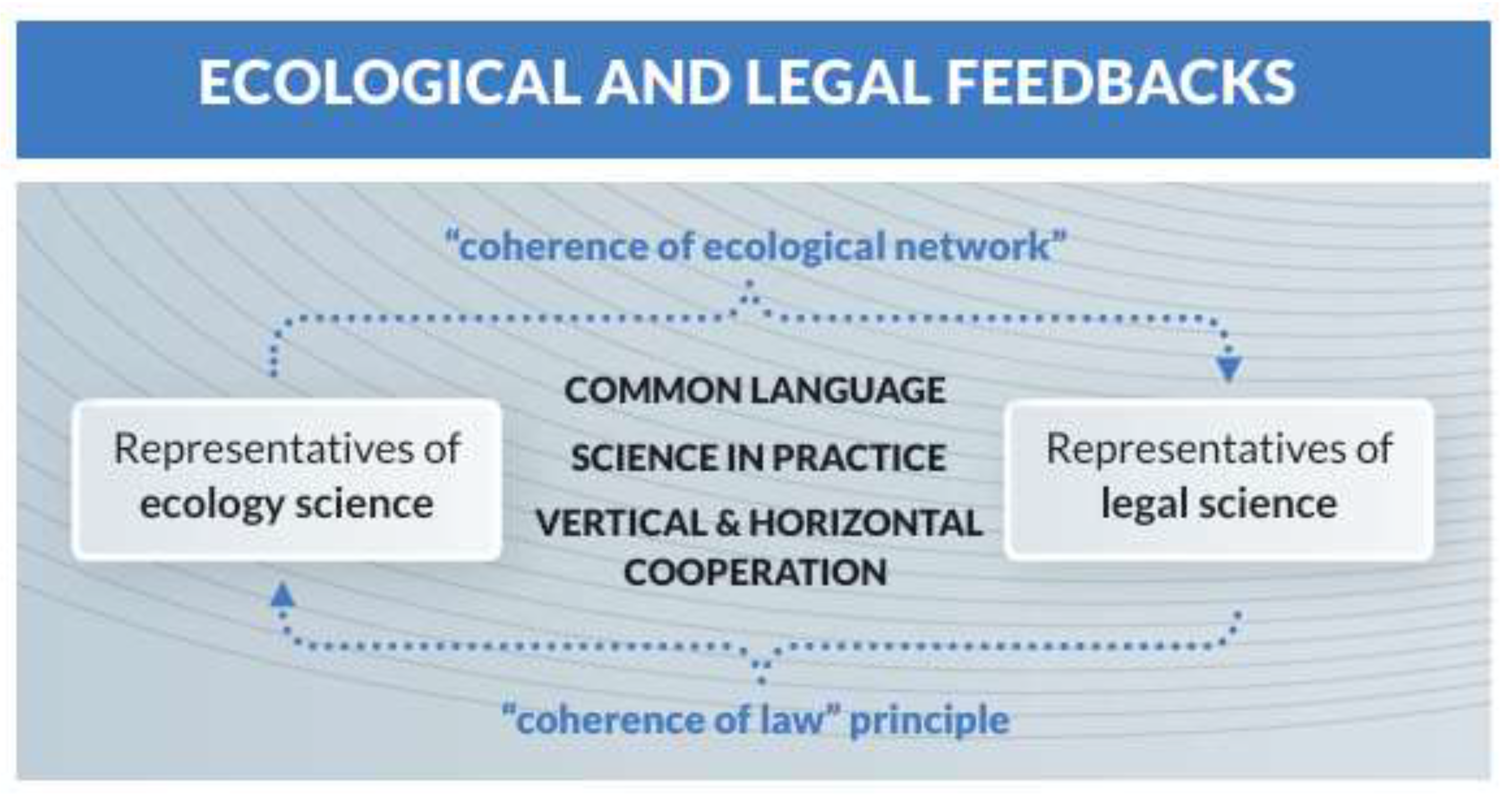

The main objective of the first sketch is to explain the interconnection between the determinants of “coherency of ecological network” and the meaning of the “coherence of law” principle [Figure no 2]. As for the education of lawyers this sketch should be understood as an introduction to ecological conditions, spatial levels and main threats to terrestrial, water and air migration of wild animals. On the other hand the lawyers should give a feedback to their colleagues from ecological team explaining why the “quantity” of legal regulations does not guaranty the “quality” of nature protection. The presented case study proves that strong misunderstandings are the effect both of lack of adequate knowledge of law makers as well as the reckless approach of non-lawyers to interpretation of fundamental legal concepts.

Figure 2.

Ecological–legal feedbacks linking ecological network coherence and the “coherence of law” principle through a common language.

Figure 2.

Ecological–legal feedbacks linking ecological network coherence and the “coherence of law” principle through a common language.

3.1.2. Legal background

Since the adoption of the Wetland Convention [

16] until the entry into force of the Landscape Convention [

17,

18], no one of the global or European wildlife protection agreement has defined such concepts as “ecological connectivity” [

19], “ecological network” [

20] or “migratory corridor” [

21]. In effect, in order to interpretate these terms for the purposes of administrative proceedings (e.g. SEA/EIA) it is necessary to conduct the cross-check of several dozen of executive acts or voluntary guidelines.. Such documents are regularly adopted during conferences and meetings of the Parties of already indicated treaties, as well as the CMS, Convention on the Conservation of European Wildlife and Natural Habitats [

22] and the Biodiversity Convention [

23].

3.2. Misunderstanding of Law

It should be noted that the only one definition concerning ecological connectivity has been included in the main text of major conventions. It is the definition of “migratory species” adopted under the CMS provisions. Paradoxically, the wording of the legal explanation constitutes the best example of factual results of a lack of vertical and horizontal cooperation during legislative stage [

24]. Unfortunately, the case concerns the recent EU official guidelines elaborated for the purposes of implementation of the European Regulation referred to as “Nature Restoration Law”. As for the water migration the main objective of the Regulation is to remove the obsolete barriers and reopen rivers patency, especially for European diadromous fish species migrating to the sea. The list of such species is compiled and publicly available as FishBase [

25]. However while defining migratory fish species the guidelines refers to the provisions of the Convention on Migratory Species [

26]. Regardless of the protection status (Appendix I or II), CMS defines “migratory species” as the “any population or any geographically separate part of the population of any species or lower taxon of wild animals, members of which periodically cross one or more national jurisdiction boundaries”. In effect if the potential beneficiaries would apply the text of the guidelines strictly and unconditionally, the only one species determining the need for restoration of longitudinal connectivity will be the Acipenser sturio (common name Baltice Sturgeon, European Sturgeon).

3.3. Lessons learnt

The main reason for the above legal status is the lack of obligation on binding interdisciplinary cooperation, which should be included in regulations on legislative techniques at all levels of nature protection law making [

27]. Based on the conclusions arising from sketch no 1, it must be remembered that the disintegration of law, as well as the legal loopholes, are the main reasons for the loopholes in ecological networks. In this metaphorical meaning, the ecological loopholes include fragmentation of terrestrial habitats [

28], infrastructural barriers concerning water and air migration [

2,

29], as well as insufficient conservation and restoration activities as regards status of migratory corridors. Next it should be noted that the “coherency of law” principle assumes that the legal schemes are appropriately integrated, regularly updated and free of systemic shortcomings [

30]. In effect, the final reflection shows that the overall coherency of ecological network is fully dependent on the coherency of law [

31]. In this context, coherent ecological networks at all scales of migration [

32] must fulfil the same criteria as a coherent legal system at all the levels of hierarchy of law [

33].

3.4. Sketch no 2 - “Integrity between legal norms” v. “Integrity of the site”

3.4.1. Core of the sketch

The second sketch shows the interconnections between the achievement of nature protection objectives such as the “integrity of conservation area” with the rules on “integrity between substantive and procedural norms” [see Figure no 3]. At first it should be remainded that the nature protection law establishes “qualitative standards and objectives” [

34], which belong to the category of “substantive norms”, also defined as “material norms” [

35]. As for the education of lawyers the main objective of this sketch should be understood as an illustration of exceptional character of nature quality standards, which are variable depending on ecological and climate feedbacks. On the other hand the lawyers shall explain to their colleagues from ecological team why the “nature quality standards” must be appropriately integrated with procedural schemes such as environmental impact assessment. In this context the authors’ argumentation assumes that the major role of the competent authority is to assess if the proposal of the plan or the project does not infringe nature quality standards.

Figure 3.

Conceptual scheme of ecological and legal feedbacks: building a common language (“science in practice”) through vertical and horizontal cooperation between ecology and legal science.

Figure 3.

Conceptual scheme of ecological and legal feedbacks: building a common language (“science in practice”) through vertical and horizontal cooperation between ecology and legal science.

3.4.2. Legal background

The best example serving development of the common language is the literal meaning of Article 6(3) and 6(4) of the Habitats Directive [

36] as well as Article 4(7) of the Water Framework Directive (WFD) [

37]. It should be remembered that all of those provisions are dedicated i.e. to the protection of ecological connectivity. The “conservation quality standard” established for the purposes of protection of Natura 2000 network at the level of core areas is the “integrity of the site” (Article 6(3) of Habitats Directive). This standard is of substantive nature because there is a general prohibition as regards implementation of plans and projects adversely affecting the ecological conditions determining favourable status of the integrity of the site. In case of the Article 4(7) of WFD, the conservation standard as regards ecological status of water bodies is to maintain favourable physical characteristics of the river (it means the hydro morphological status).

Under the provisions of Article6(4) of the Habitats Directive and art. Article 4(7) of the WFD, the exemptions from general prohibition may be granted only in exceptional cases. The specific conditions of the derogations include i.e. such prerequisites as lack of less harmful alternative solutions [

38] and implementation of necessary mitigation or compensatory measures. If those conditions are not fulfilled by the proposal of the plan or project, the authority conducting SEA or EIA is obligated to refuse the authorisation of the submitted application [

39].

3.4.5. Disintegrated law

As regards integrity between substantive and procedural norms, it must be noted that Articles 6(3) and 6(4) of the Habitats Directive are literally integrated both with SEA [

40] and EIA Directive [

41]. That’s because in the light of Article 6(3), the so-called “Habitats Assessment” concerns “plans” and “projects”. On the contrary, Article 4(7) of WFD uses such terms as “new modifications” or “human development activities”. One of the few legal analyses concerning the applicatory improvement of Article 4(7) of WFD concludes that the hurdle for the correct and uniform application of this provision is the lack of explicit procedural rules for the assessment [

42]. At the same time, the authors of the analysis indicate that the Article 4(7) should be applied not only during EIA but also as regards SEA procedures. Actually it has a cardinal role regarding the maintenance and restoration of longitudinal connectivity of the rivers, especially as regards undisturbed migration of diadromous fish species. However this viewpoint has not been justified in the text of analysis by any official statement which in the best variant should be based on the European Court of Justice (CJUE) rulings. The authors of this article used the words “in the best variant” because interpretation powers of the CJUE are of law making nature. In fact it must be noted that nearly all of the rulings of the CJUE concern cases assessing conformity of individual projects with the requirements of Article 4(7) of Water Framework Directive. Those judgments do not even point out that Article 4(7) may also cover plans and programmes subject to SEA procedure. Except one – Court Judgment in case C 525/20 [

43]. The Judgment of the Court (Second Chamber) is of 5 May 2022. Since then, Case C-525/20 has been discussed in doctrinal commentaries and in peer-reviewed scholarship [

44,

45,

46], which consistently emphasise that competent authorities are not allowed to disregard temporary and short-term impacts “without long-term consequences” in the deterioration assessment, unless it is clear that such impacts are, by their nature, capable of having only a minor effect on water body status. In this sense, the later literature treats C-525/20 as consolidating a stricter authorisation-stage reading of the non-deterioration obligation and the practical relevance of the Article 4(6)–4(7) logic where deterioration cannot be ruled out.

3.4.6. Lessons learnt

Based on the conclusions arising from sketch no 2 it should be noted that the impact of hydro-technical barriers on catadromous, amphibiotic fish species migrating from the sea to rivers’ spawning grounds depends on the migration route length, the number of barriers necessary to overcome, the presence and type of mitigation measures (such as rapids, semi-natural bypasses, technical bypasses), and their suitability for ecological needs of particular species (e.g. greater ability to overcome strong currents in salmon and sea trout and lower ability in vimba and river lamprey) [

47].

Taking into account the scope and objectives of this article as well as the potential subject of future interdisciplinary discussions, now it should be clear why in the case of Article 4(7) of WFD, there is a lack of clear and precise integrity between substantive and procedural regulations. In effect, the overall longitudinal connectivity of the European rivers is not sufficiently protected. That is the reason why the competent representatives of environmental law jurisprudence underlines that: “Provisions of the SEA Directive and the EIA Directive not backed by a substantive legal regime should be treated as low-quality administrative standards, the application effectiveness of which depends solely on the competence of administrative bodies” [

48].

Based on the conclusions arising from both sketches, the authors formulate operational recommendations for SEA/EIA practice in the form of framework cooperation agreements (Figure no 4) and a set of key definitions proposed for transboundary SEA (

Table 1).

Table 1.

Proposed definitions for transboundary SEA of wind-farm plans: migratory bird corridor, favourable status, alternative solutions, impacts, and mitigation/compensation measures.

Table 1.

Proposed definitions for transboundary SEA of wind-farm plans: migratory bird corridor, favourable status, alternative solutions, impacts, and mitigation/compensation measures.

4. Discussion

If the science utility principle remains valid, the authors recommend implementing the “framework cooperation agreements”. Considering that nature protection law belongs to the administrative branch of legal science, the cooperation model at the legislative stage should be based on the constitutional rules and the sequency of steps presented in Figure no 4.

Figure 4.

Five-step integrated approach to regulation-making for ecological connectivity and the distribution of interdisciplinary responsibilities.

Figure 4.

Five-step integrated approach to regulation-making for ecological connectivity and the distribution of interdisciplinary responsibilities.

Today, a number of emergency topics raise serious concerns about the future of ecological connectivity. In the authors’ opinion one of the most critical is the lack of international and transcontinental cooperation in the field of impact assessments of wind farm developments on migratory birds species. However, despite of the international community readiness as regards strengthening the wildlife legislation, it must be underlined that there is no more time for a passive approach. This case gives an ideal ground for entering the discussion between decision makers, scientists and practitioners. Moreover the process of recommended cooperation will in fact verify the thesis and argumentation presented in this article. Starting from vertical and horizontal cooperation, the authors suggest to continue the dialog on the basis of specific topic in accordance with the sequency of steps presented in Figure no 4. In effect one of the main elements of the preparatory works is to fill the gap in conceptual framework which should be used consequently in the course of all parallel SEA procedures. The Table no 1 consists of proposals of most important definitions elaborated by the authors as an incentive for further analysis on methodological aspects of transboundary impact assessments.

The list of definitions should allow the international and national decision-makers, administrative authorities and the consultancy sector (executors of SEA reports) to find the common language as soon as possible. Moreover the order of the terms presented in Table no 1 is not random, rather it was elaborated in accordance with the rules on good practices in inter-team cooperation, as well as the sequence of procedural steps during strategic environmental assessment. As it was mentioned during both sketches, the members of SEA executory teams must understand the roles and expectations of all cooperating experts as regards preparation of entry data, the rules on appropriate assessments and other aspects of SEA which are determined by interpretation of the mentioned terms. Moreover, the adopted or recommended methods must be supervised on a regular basis in order to assess if they bring expected results.

The next stage of the discussion, which is so serious challenge that it should be the subject of subsequent article, concerns indication of the most appropriate legal basis for SEA’s as regards particular migratory routes. Presentation of the geographic explicit data on the location of migratory corridors belongs to ornithologists and GIS experts. This data should be submitted to environmental lawyers in order to assess which one of the convention, executive agreement or MoU creates the most appropriate empowerment for entering the intergovernmental negotiations. As a general rule the majority of migratory birds executive agreements have been adopted under the auspices of CMS and are available at Secretariats website (subdomain: CMS instruments). The exceptional legal basis concern bilateral Conventions signed by USA with Canada in 1916, Mexico in 1936, Japan in 1972, and Russia in 1976 [

49,

50,

51,

52].

In the meantime the ornithologists, GIS and IT experts shall be responsible for creating the data basis gathering the conclusions of the latest reports on migration patterns, conservation status of specified species and finally collective or specific flyways monitoring reports.

The above analysis should be compiled in the form of entry reports as a result of cooperation between the Secretariats of the Conventions (executive agreements, MoU) with scientific institutions and non-governmental organizations. The reports shall be then submitted to competent national bodies in order to corelate and give a feedback on the status of existing, approved and planned wind farm projects. Basing on the conclusions of comparative ecological, legal and infrastructural analysis the formal process on scoping and establishing of methods of SEA’s should begin.

5. Conclusions

The final recommendation resulting from the discussion assumes that in case of international environmental agreements dedicated to the protection and restoration of continental or global natural resources, certain specific conditions must be met:

the major Conventions must ensure a coherent conceptual and conservation schemes;

in case of overlapping of the subjective matter, the Conferences of Parties and Secretariats of the Conventions are obligated on the basis of the existing texts of agreements or its executive acts to harmonise the sets of implementation measures;

in case of necessary actions that should be undertaken by several parties, the competent governments should adopt appropriate legal measures concerning common rules, methodology, and public tenders, as well as indicate national administrative bodies responsible for certain decisions and cooperation with involved foreign administrations.

The special discussion which the authors would like to open considers symbolic modification of the content of journals falling within the scope of such sciences as biology, ecology, science on Earth, hydrology, hydrobiology, environmental protection and management as well as law and economy, etc. It would be very helpful for removing the “barrier effect” within horizontal and vertical dimensions, even in the way of publication of short, interdisciplinary case notes, viewpoints or letters to editors. If the policy of these journals allows for open discussions across sciences the proposal will also result in new audience originating from practitioners’ sectors, including both public administration and consulting. There are no doubts that such state of facts will increase the effectiveness of nature protection policy.

Author Contributions

Marcin Pchałek: Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal analysis, Investigation, Methodology, Project administration, Supervision, Validation, Visualization* - visual concept, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing.

Aleksandra Szurlej-Kielańska: Conceptualization, Methodology, Supervision, Validation, Writing – review & editing. * Execution of graphics - Graphic design studio “DoLasu”

https://dolasu-pracownia.pl/.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Data Availability Statement

All sources used in this study are publicly available documents and are cited in the References.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank in the first line Paweł Prus (PhD, coauthor of European monitoring method EFI+) for the input concerning migratory fish species, as well as Beata Jacheć for editorial and administrative support.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Thompson, P. L.; Rayfield, B.; Gonzalez, A. Loss of habitat and connectivity erodes species diversity, ecosystem functioning, and stability in metacommunity networks. Ecography 2017, 40(1), 98–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jones, P. E.; Champneys, T.; Vevers, J.; Börger, L.; Svendsen, J. C.; Consuegra, S.; Jones, J.; Garcia de Leaniz, C. Selective effects of small barriers on river-resident fish. Journal of Applied Ecology 2021, 58(3), 642–652. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Konya, A.; Nematzadeh, P. Recent applications of AI to environmental disciplines: A review. Science of The Total Environment 2024, 906, 167705. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nilsson, C.; Dokter, A. M.; Schmid, B.; et al. Field validation of radar systems for monitoring bird migration. Journal of Applied Ecology 2018, 55(6), 2552–2564. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adamczyk, M.; Prus, P.; Buras, P.; Wiśniewolski, W.; Ligięza, J.; Szlakowski, J.; Borzęcka, I.; Parasiewicz, P. Development of a new tool for fish-based river ecological status assessment in Poland (EFI+IBI_PL). Acta Ichthyologica et Piscatoria 2017, 47(2), 173–184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marques, N.; Soares, C. D. M.; Casali, D. M.; Guimarães, E.; Fava, F.; Abreu, J. M. S.; Moras, L.; et al. Retrieving biodiversity data from multiple sources: Making secondary data standardised and accessible. Biodiversity Data Journal 2024, 12, e133775. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carey, C. C.; Ward, N. K.; Farrell, K. J.; Lofton, M. E.; Krinos, A. I.; McClure, R. P.; Subratie, K. C.; Figueiredo, R. J.; Doubek, J. P.; Hanson, P. C.; Papadopoulos, P.; Arzberger, P. Enhancing collaboration between ecologists and computer scientists: Lessons learned and recommendations forward. Ecosphere 2019, 10(5), e02753. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keyser, S.; Pauli, J.; Fink, D.; Radeloff, V.; Pigot, A.; Zuckerberg, B. Seasonality Structures Avian Functional Diversity and Niche Packing Across North America. Ecology Letters 2024, 27, e14521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zurell, D.; Graham, C.H.; Gallien, L.; et al. Long-distance migratory birds threatened by multiple independent risks from global change. Nature Clim Change 2018, 8, 992–996. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bennun, L.; van Bochove, J.; Ng, C.; Fletcher, C.; Wilson, D.; Phair, N.; Carbone, G. Mitigating biodiversity impacts associated with solar and wind energy development: Guidelines for project developers. In IUCN; The Biodiversity Consultancy.: Gland, Switzerland; Cambridge, UK, 2021; p. 10. [Google Scholar]

- Australian Government; Department of Sustainability; Environment; Water; Population and Communities (DSEWPaC). Environment Protection and Biodiversity Conservation Act 1999 (EPBC Act) Environmental Offsets Policy; Available online; Australian Government: Canberra, Australia, 2012; (accessed on 07.02.2026)(Environment Protection and Biodiversity Conservation Act 1999 Environmental Offsets Policy). [Google Scholar]

- Measuring the effectiveness of environmental law through legal indicators and quality analyses. In IUCN Environmental Policy and Law Paper; Fromageau, J., Cherkaoui, A., Coll, R., Eds.; IUCN: Gland, Switzerland, 2023; Volume No. 91. [Google Scholar]

- Convention on the Conservation of Migratory Species of Wild Animals (CMS, Bonn Convention); Bonn, Germany, 1979. Available online: S:\_Basic_Docs\CMS_Conv_Text\English\CMS-text.en.wpd. (accessed on 07.02.2026).

- UNEP-WCMC. Report on state of the world’s migratory species. 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Hanna, J. Favourable Conservation Status Definitions. In Natural England Technical Information Note; 2021; Volume TIN180, p. 7. [Google Scholar]

- Convention on Wetlands of International Importance especially as Waterfowl Habitat (Ramsar Convention). Ramsar, Iran, 1971. Available online: https://www.ramsar.org/sites/default/files/documents/library/current_convention_text_e.pdf (accessed on 07.02.2026).

- Council of Europe. European Landscape Convention. (ETS No. 176); Florence, Italy, 20 October 2000. Available online: https://rm.coe.int/1680080621? (accessed on 06.02.2026).

- Kettunen, M.; Genovesi, P.; Gollasch, G.; Shine, C. Guidance on the Maintenance of Landscape Features of Major Importance for Wild Flora and Fauna: Guidance on the Implementation of Article 3 of the Birds Directive (79/409/EEC) and Article 10 of the Habitats Directive (92/43/EEC); Institute for European Environmental Policy: Brussels, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Fattorini, N.; Costanzo, A.; Romano, A.; Rubolini, D.; Baillie, S.; Bairlein, F.; Spina, F.; Ambrosini, R. Eco-evolutionary drivers of avian migratory connectivity. Ecology Letters. 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bennett, G.; Mulongoy, K. J. Review of experience with ecological networks, corridors and buffer zones; Secretariat of the Convention on Biological Diversity: Montreal, 2006; Volume Technical Series No. 23, p. 4. [Google Scholar]

- Pchałek, M.; Kupczyk, P. Protection of ecological corridors in EU environmental law. Environmental Law & Management 2019, 31(5), 216. [Google Scholar]

- Council of Europe. Convention on the Conservation of European Wildlife and Natural Habitats. (Bern Convention) (CETS No. 104); Bern, Switzerland, 1979. Available online: https://rm.coe.int/1680078aff? (accessed on 06.02.2026).

- Convention on Biological Diversity (CBD). Rio de Janeiro, Brazil, 5 June 1992. Available online: https://www.cbd.int/convention/text (accessed on 06.02.2026).

- Liczner, A. R.; Pither, R.; Bennett, J. R.; Bowman, J.; Hall, K. R.; Fletcher, R. J., Jr.; Ford, A. T.; Michalak, J. L.; Rayfield, B.; Wittische, J. Advances and challenges in ecological connectivity science. Ecology and Evolution 2024, 14, e70231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- FishBase. Available online: https://fishbase.se/search.php.

- Van De Bund, W.; Bartkova, T.; Belka, K.; Bussettini, M.; Calleja, B.; Christiansen, T.; Bastino, V. Criteria for Identifying Free-Flowing River Stretches for the EU Biodiversity Strategy for 2030; Publications Office of the European Union, Luxembourg, 2024; Volume JRC137919, p. 31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patlachuk, O. V. Legal technique of legislative acts in the field of nature protection (1992–2006). Problems of Legality 2019, (146), 37–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Byron, H.; Arnold, L. TEN-T and Natura 2000—the way forward: an assessment of the potential impact of the TEN-T Priority Projects on Natura 2000. Final report. In The Royal Society for the Protection of Birds (RSPB); Scotland, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Merriman, J. How Many Birds Are Killed by Wind Turbines? American Bird Conservancy Blog. 2021. Available online: https://abcbirds.org/blog/how-many-birds-are-killed-by-wind-turbines.

- Lu, S.; Wang, H. How political connections exploit loopholes in procurement institutions for government contracts: Evidence from China. Governance 2023, 36(4), 1205–1224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bastino, V.; Boughaba, J.; van de Bund, W. Biodiversity Strategy 2030: Barrier Removal for River Restoration. Luxembourg: Publications Office of the European Union 2022, 13–14. [Google Scholar]

- Maia, K.; Guimarães, P., Jr. The Hierarchical Coevolutionary Units of Ecological Networks. Ecology Letters 2024, 27, e14501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lenaerts, K.; Desomer, M. Towards a Hierarchy of Legal Acts in the European Union? Simplification of Legal Instruments and Procedures. European Law Journal 2005, 11(6), 744–765. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sutherland, W. J.; Dicks, L. V.; Everard, M.; Geneletti, D. Qualitative methods for ecologists and conservation scientists. Methods in Ecology and Evolution 2018, 9, 7–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ziganshina, D. International Water Law in Central Asia: The Nature of Substantive Norms and What Flows from It. Asian J. Int. Law 2012, 2, 169–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Council Directive 92/43/EEC of 21 May 1992 on the conservation of natural habitats and of wild fauna and flora (Habitats Directive). Off. J. Eur. Communities Available online. 1992, L 206, 7–50. (accessed on 07.02.2026).

- European Parliament and Council. Directive 2000/60/EC of 23 October 2000 establishing a framework for Community action in the field of water policy (Water Framework Directive). Off. J. Eur. Communities Available online. 2000, L 327, 1–73. (accessed on 06.02.2026). [Google Scholar]

- Pchałek, M. The Legalization of Unpermitted Projects in the Light of Requirements of the EIA Directive. In European Energy and Environmental Law Review 6/2019; 2019; Volume 28, pp. 101–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dworak, T.; Kampa, E.; Berglund, M. Exemptions under Article 4(7) of the Water Framework Directive; Common Implementation Strategy Workshop Key Issues Paper: Brussels, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- European Parliament and Council. Directive 2001/42/EC of 27 June 2001 on the assessment of the effects of certain plans and programmes on the environment (SEA Directive). Off. J. Eur. Communities 2001, L 197, 30–37. Available online: https://eur-lex.europa.eu/eli/dir/2001/42/oj/eng (accessed on 07.02.2026).

- European Parliament and Council. Directive 2011/92/EU of 13 December 2011 on the assessment of the effects of certain public and private projects on the environment (EIA Directive) (codification). Off. J. Eur. Union 2012, L 26, 1–21. Available online: https://eur-lex.europa.eu/eli/dir/2011/92/oj/eng (accessed on 07.02.2026).

- Justice and Environment. Improving the Quality of Applicability Assessments under Art 4(7) of WFD: The Environmental Impact Assessment as a Role Model for the Assessments of Impacts on Water Bodies. In Legal analysis; Justice and Environment: Brno, Czech Republic, 2019; Available online: https://zagovorniki-okolja.si/wp-content/uploads/2019/07/WFD_Art_4_7_legal_requirements_fin_31.05.19.pdf (accessed on 02.02.2026).

- Court of Justice of the European Union. Judgment of 5 May 2022, Association France Nature Environnement. C-525/20, ECLI:EU:C:2022:350. Available online: https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/?uri=CELEX:62020CJ0525 (accessed on 05.02.2026).

- Court of Justice of the European Union. Judgment of 21 March 2024, T GmbH v Bezirkshauptmannschaft Spittal an der Drau. C-671/22, ECLI:EU:C:2024:256. Available online: https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/?uri=CELEX:62022CJ0671 (accessed on 07.02.2026).

- Pihalehto, M.; Puharinen, S.-T. Uncharted Interplay and Troubled Implementation: Managing Hydropower’s Environmental Impacts under the EU Water Framework and Environmental Liability Directives. J. Environ. Law 36 2024, 43–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Court of Justice of the European Union. Judgment of 20 November 2025, European Commission v Ireland. C-204/24, ECLI:EU:C:2025:912. Available online: https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/?uri=CELEX:62024CJ0204 (accessed on 07.02.2026).

- DVWK; FAO. Fish Passes: Design, Dimensions and Monitoring; FAO: Rome, Italy; Deutscher Verband für Wasserwirtschaft und Kulturbau e.V., 2002; Available online: https://www.fao.org/4/y4454e/y4454e00.htm (accessed on 07.02.2026).

- Scannell, Y.; Cox, A. Interaction between the EIA Directive and Articles 6.3 and 6.4 of the Habitats Directive. Judicial Conference Barcelona, 2022; Available online: http://www.era-comm.eu/Cooperation_national_judges_environmental_law/module_2/11.pdf.

- U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service. Convention between the United States and Great Britain (for Canada) for the Protection of Migratory Birds; Signed in Washington, DC. 16 August 1916. Available online: https://www.fws.gov/sites/default/files/documents/treaty-canada-migratory-birds-1916.pdf (accessed on 06.02.2026).

- U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service. Convention between the United States of America and the United Mexican States for the Protection of Migratory Birds and Game Mammals; Signed in Mexico City. 7 February 1936. Available online: https://www.govinfo.gov/link/statute/50/1311 (accessed on -6.02.2026).

- U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service. Convention between the Government of the United States of America and the Government of Japan for the Protection of Migratory Birds and Birds in Danger of Extinction, and Their Environment. Signed in Tokyo, 4 March 1972. Available online: https://www.fws.gov/sites/default/files/documents/treaty-japan-migratory-birds.pdf (accessed on 06.02.2026).

- U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service. Convention between the United States of America and the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics Concerning the Conservation of Migratory Birds and Their Environment. Signed in Moscow, 19 November 1976. Available online: https://www.fws.gov/sites/default/files/documents/treaty-russia-migratory-birds.pdf (accessed on 06.02.2026).

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |