Submitted:

06 February 2026

Posted:

09 February 2026

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

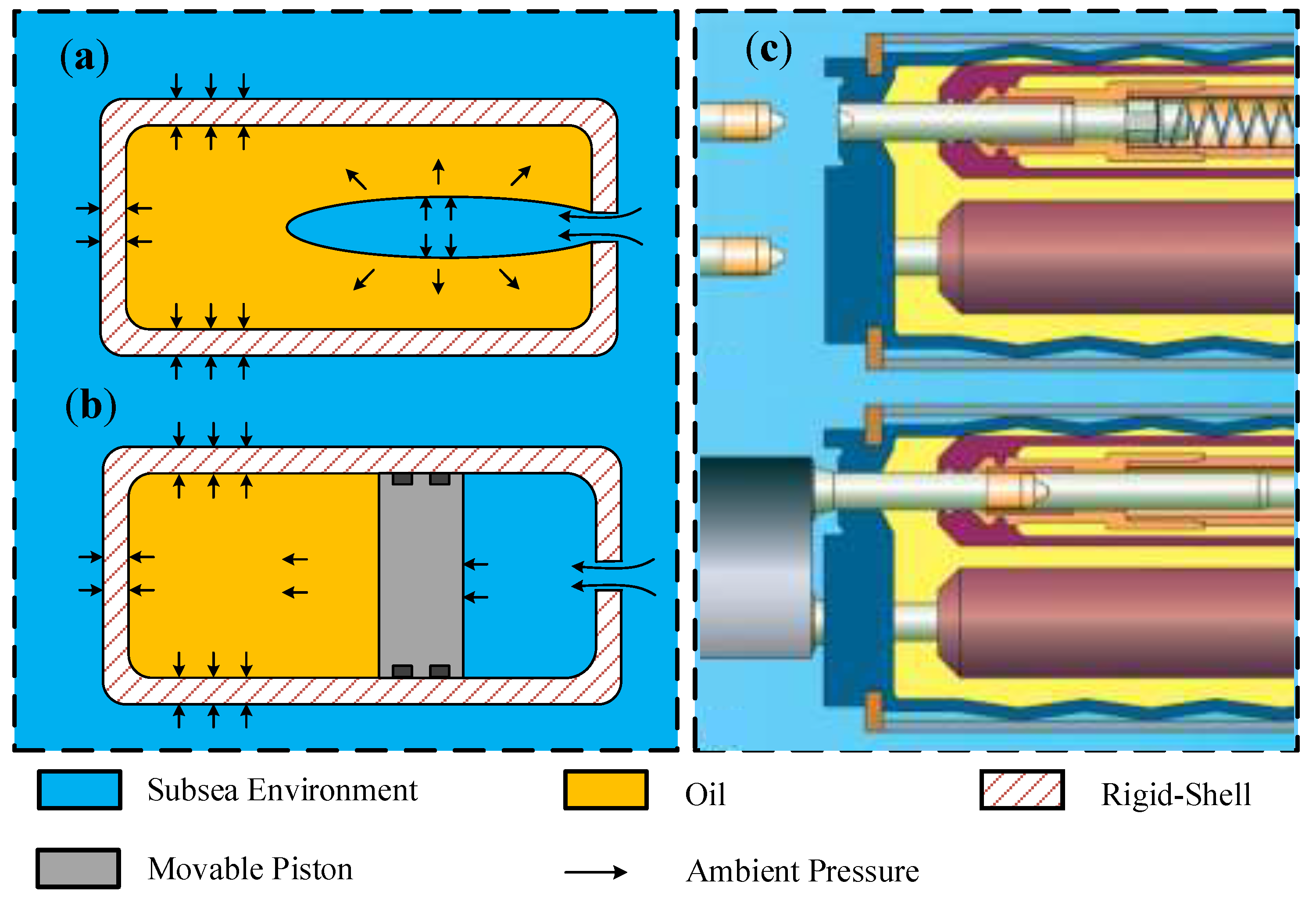

2. Lubricant Interactions in Deep-Sea Extremes: A Review of Environmental Characteristics and System Responses

2.1. Multi-Scale Parametric Characteristics of Deep-Sea Environments: Pressure and Temperature

2.2. Thermodynamic and Rheological Responses of Lubricants to Deep-Sea Pressure-Temperature

| Type | Model | Formula | Equation number |

|---|---|---|---|

| Viscosity–temperature correlation | Reynolds | (1) | |

| Andrade-Erying | (2) | ||

| Slotte | (3) | ||

| Vogel | (4) | ||

| Walther | (5) | ||

| Viscosity–pressure correlation | Barus | (6) | |

| Roelands | (7) | ||

| Cameron | (8) | ||

| Viscosity–temperature–pressure correlation | Barus and Reynolds | (9) | |

| Roelands | (10) | ||

| WLF-Yasutom | (11) |

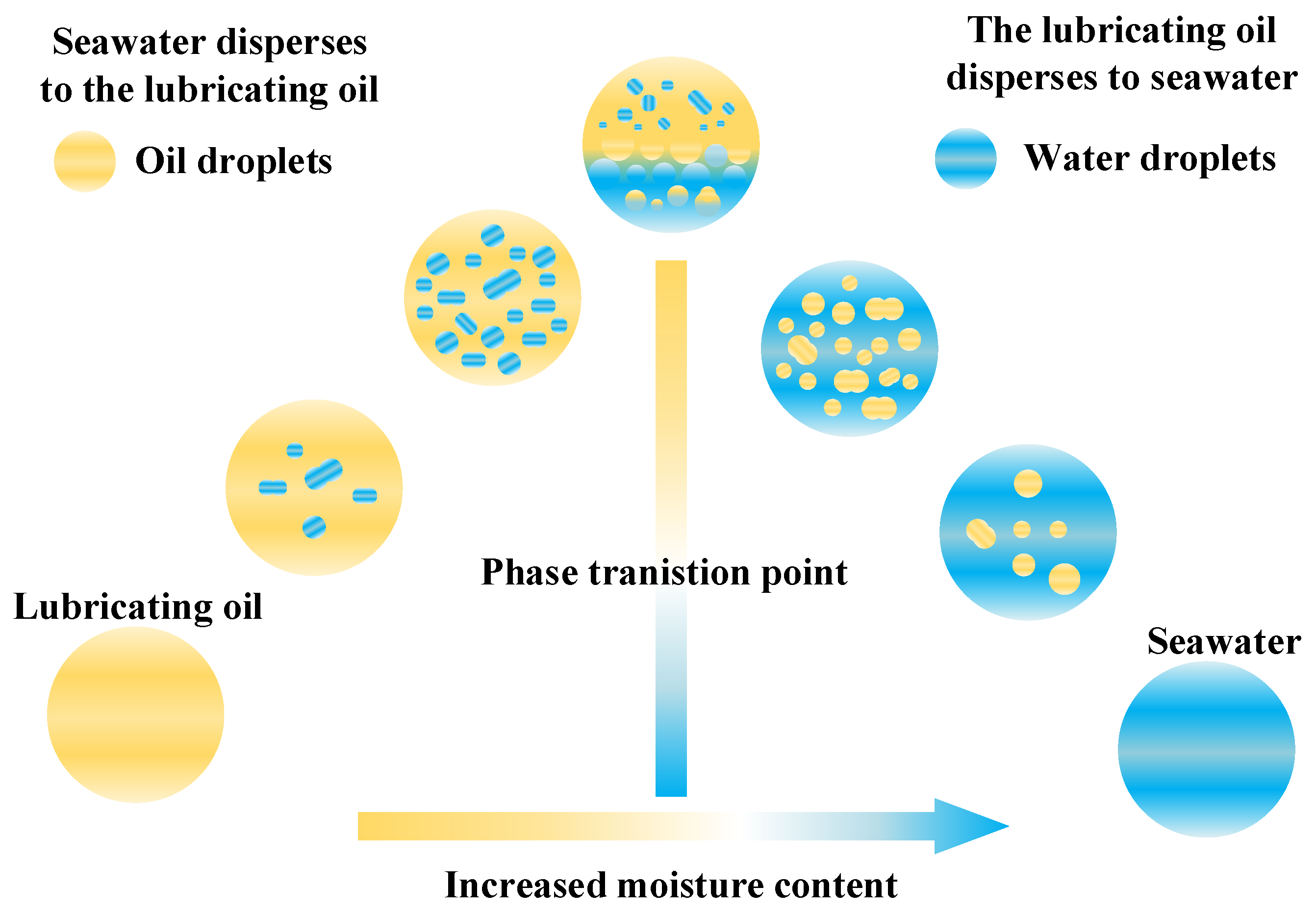

2.3. Lubricant Density: A Foundation for Thermophysical Property Estimation and Performance Prediction

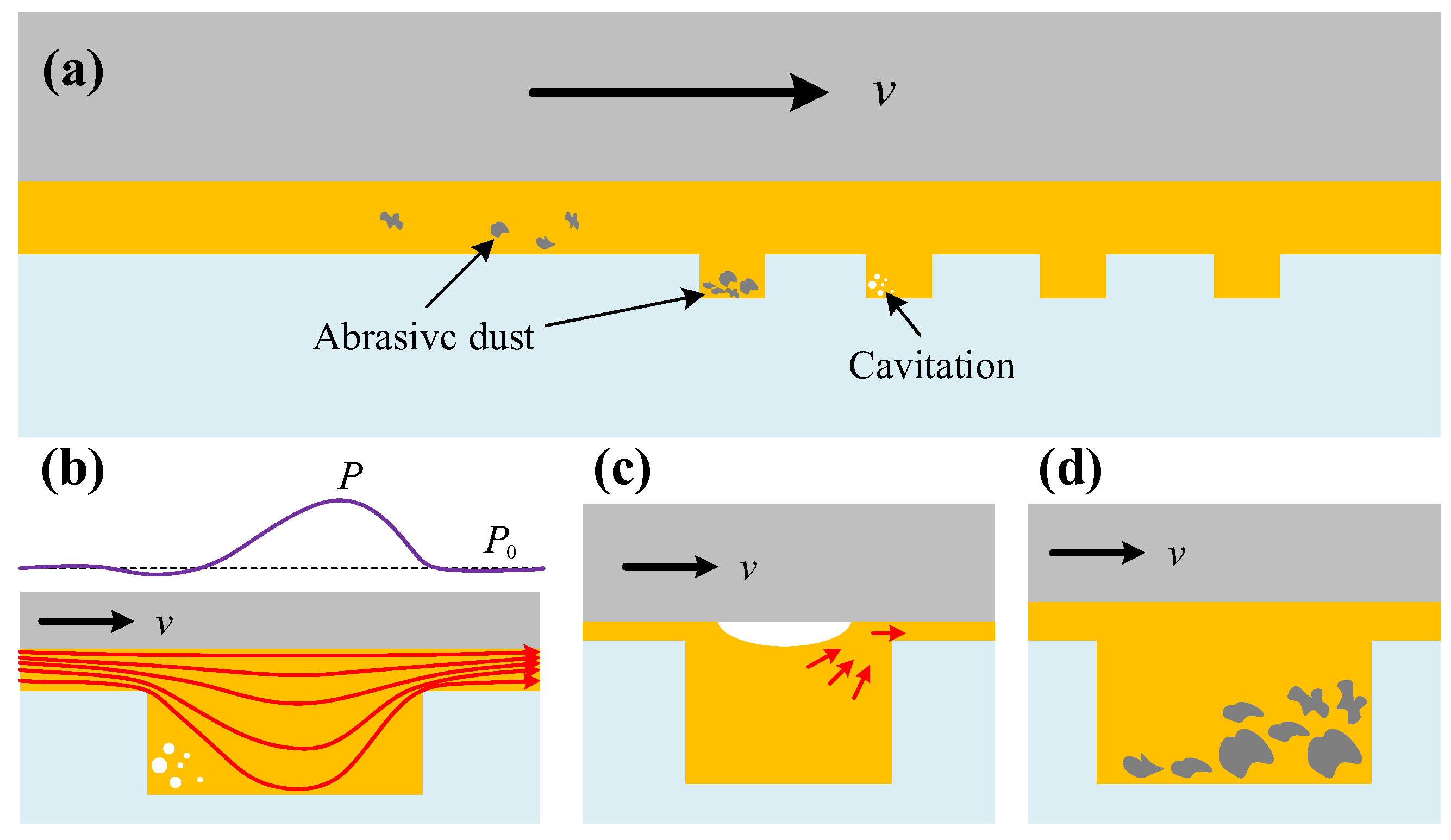

2.4. Seawater Ingress-Induced Multiscale Degradation of Deep-Sea Gearbox Lubricant: Damage Mechanisms, Performance Prediction, and Intrusion-Resistant Technology

3. EHL Theory in Ultra-Deep Marine Conditions: Adaptive Mechanisms, Key Challenges, and Frontiers

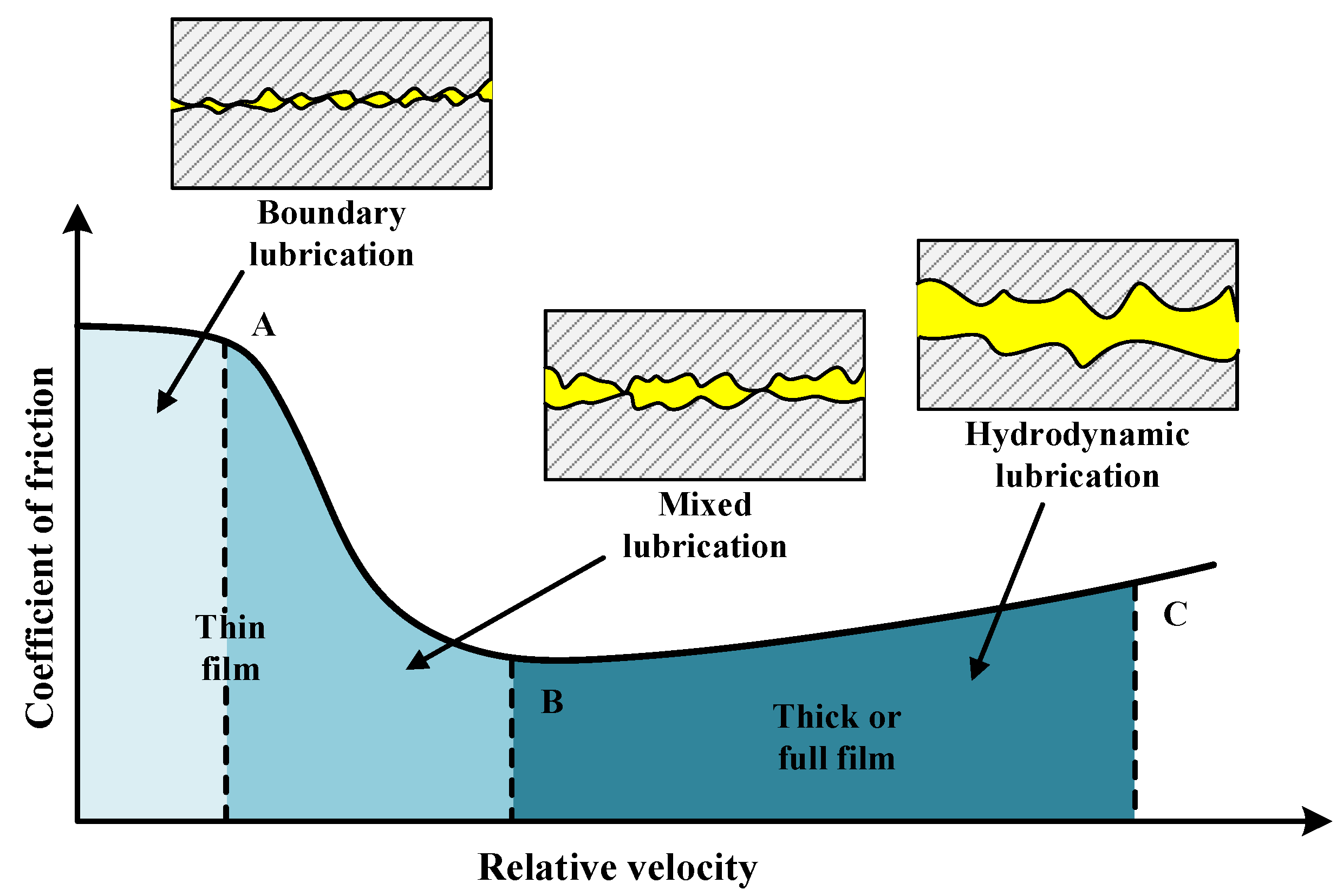

3.1. Multi-Physics Coupling Effects on Lubrication Regime Transitions in Deep-Sea Gear Transmission Meshing Interfaces

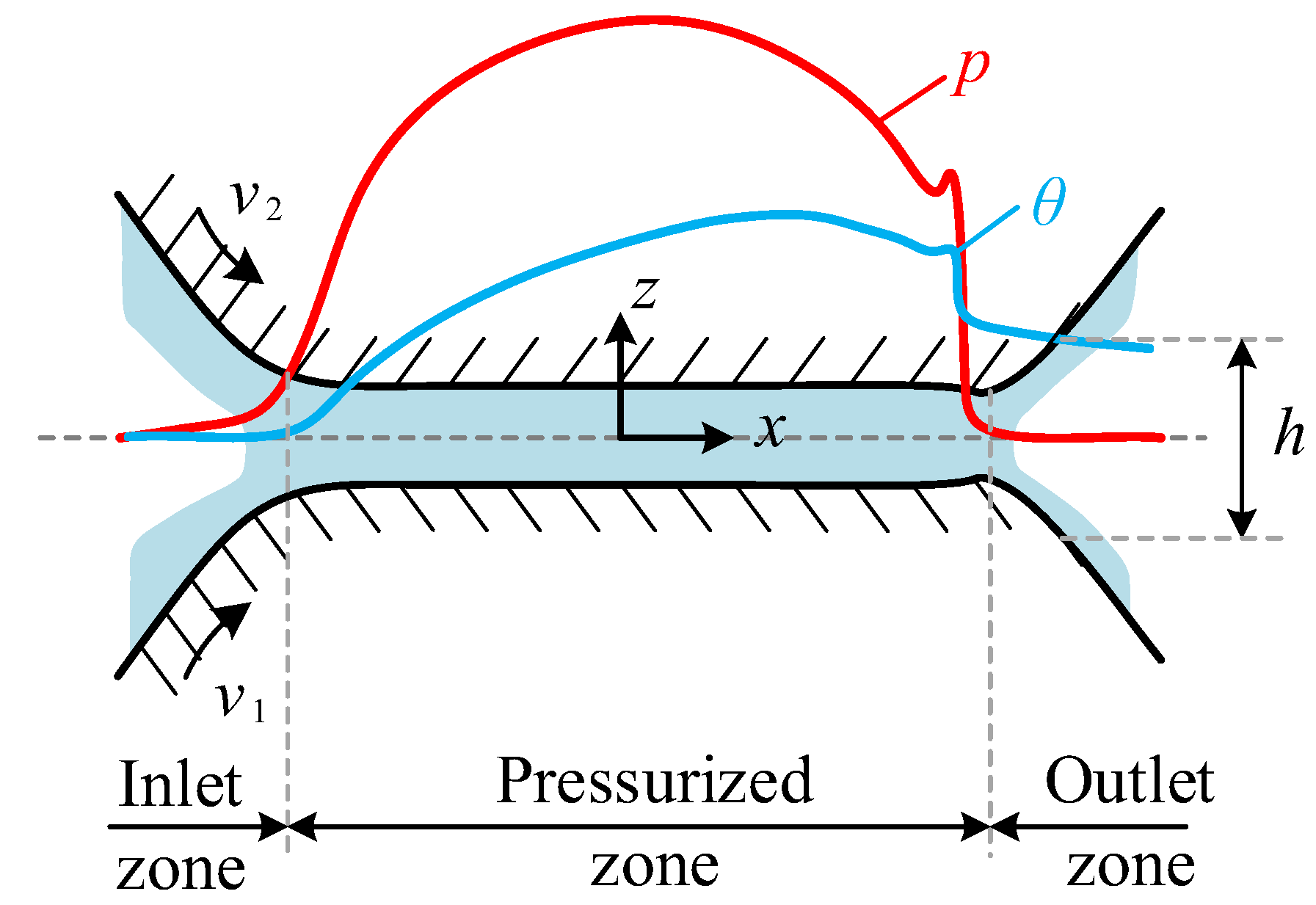

3.2. TEHL Theory for Gears Operating Under High-Pressure and Low-Temperature Conditions

3.3. Applicability and Challenges of EHL in Deep-Sea Environments

4. Meshing Interface Texturing Technology and Its Application Prospects in Deep-Sea Gear Lubrication

4.1. Mechanisms of Friction Reduction and Wear Resistance in Micro-Textured Meshing Interfaces

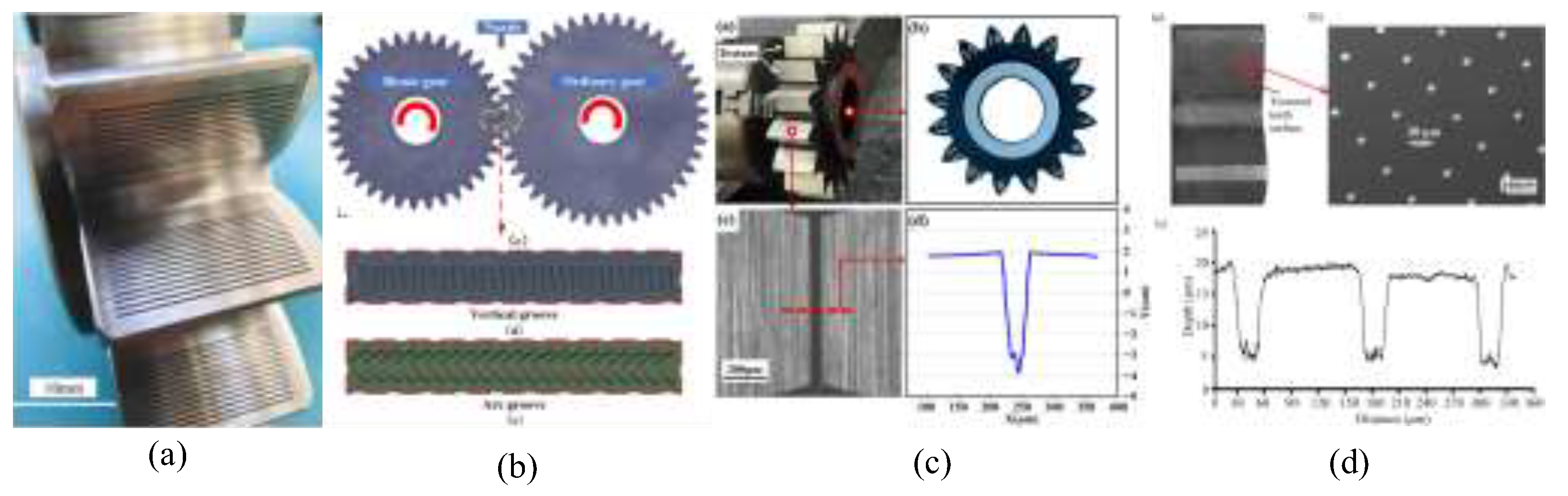

4.2. Micro-Texturing Technologies for Gear Meshing Interfaces: From Lubrication Mechanisms to Anti-Scuffing Load-Bearing Applications

4.3. Meshing Interface Enriched Lubrication Considering Micro-Texture Effects

4.4. Multiscale Micro-Texturing Meshing Interface for Deep-Sea Gear Transmission Environmental Challenge

5. Conclusions and Prospects

5.1. Summary of Findings and Conclusions

5.2. Future Research Perspectives

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Brandt, A.; Gutt, J.; Hildebrandt, M.; Pawlowski, J.; Schwendner, J.; Soltwedel, T.; Thomsen, L. Cutting the umbilical: new technological perspectives in benthic deep-sea research. Journal of Marine Science and Engineering 2016, 4, 36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, T.; Wang, R.; Wang, Y.; Cheng, L.; Wang, S.; Tan, M. Design and locomotion control of a dactylopteridae-inspired biomimetic underwater vehicle with hybrid propulsion. IEEE Transactions on Automation Science and Engineering 2021, 19, 2054–2066. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, H.; Wu, D.; Gao, C.; Xu, C.; Yang, X. Development of a six-degree-of-freedom deep-sea water-hydraulic manipulator. Journal of Marine Science and Engineering 2024, 12, 1696. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, Y.; Chen, C.; Bu, C.; Han, J. A polar rover for large-scale scientific surveys: design, implementation and field test results. International Journal of Advanced Robotic Systems 2015, 12, 145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruan, J.; Wang, X.; Wang, Y.; Zou, W. Mechanistic Analysis of Textured IEL and Meshing ASLBC Synergy in Heavy Loads: Characterizing Predefined Micro-Element Configurations. Machines 2025, 13, 842. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, W.; Yu, Z.; Yang, G.; Li, X.; Wang, A. : Study on the Evolution of Volume Efficiency of Gear Pump in Deep Sea Extreme Environment. Chinese Hydraulics & Pneumatics 2024, 48, 28–36. [Google Scholar]

- Mia, S.; Mizukami, S.; Fukuda, R.; Morita, S.; Ohno, N. High-pressure behavior and tribological properties of wind turbine gear oil. Journal of mechanical science and technology 2010, 24, 111–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du, K.; Xi, W.; Huang, S.; Zhou, J. Deep-sea mineral resource mining: a historical review, developmental progress, and insights. Mining, Metallurgy & Exploration 2024, 41, 173–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, Y.; Chen, M.; Du, Y.; Li, M. Key mechanical issues and technical challenges of deep-sea mining development system. Mechanics in Engineering 2022, 44, 1005–1020. [Google Scholar]

- Zhao, Y.; Li, N.; Xie, K.; Wang, C.; Zhou, S.; Zhang, X.; Ye, C. Manufacturing of lithium battery toward deep-sea environment. International Journal of Extreme Manufacturing 2024, 7, 022009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, W.; Cui, W. An overview of underwater connectors. Journal of marine science and engineering 2021, 9, 813. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Z.; Dai, Y.; Wu, S.; Yang, C. Active Pressure-Compensation Technology for Deep-Sea Fluid Samplers. IEEE Journal of Oceanic Engineering 2025, 50, 2456–2467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sperka, P.; Krupka, I.; Hartl, M. Lubricant flow in thin-film elastohydrodynamic contact under extreme conditions. Friction 2016, 4, 380–390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cai, M.; Wu, S.; Yang, C. Effect of low temperature and high pressure on deep-sea oil-filled brushless DC motors. Marine Technology Society Journal 2016, 50, 83–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, R.; Shi, X.; Lu, X.; Sun, W.; Liu, H. Study on Mixed Lubrication Characteristics of Helical Gears of Marine Diesel Engine under Real Machining Surface. Journal of Mechanical Engineering 2025, 61, 290–304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gong, P.; Wen, X.; Bai, P.; Yue, L.; Ding, J.; Tian, Y.; Li, L. Influence of Low Concentration Seawater on the Friction Corrosion Performance of Water–Glycol Fire-Resistant Hydraulic Fluid. Journal of Bio-and Tribo-Corrosion 2024, 10, 49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, B.; Wang, J.; Yan, F. Friction and wear behaviors of several polymers sliding against GCr15 and 316 steel under the lubrication of sea water. Tribology letters 2011, 42, 17–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiao, D.; Deng, Y.; Wang, Z.; Li, T.; Liu, Y. Viscosity evolution of water glycol in deep-sea environment at high pressure and low temperature. Journal of Molecular Liquids 2023, 387, 122387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qian, X.; Yan, W.; Chen, S.; Zhang, Y.; Luo, Y.; Liu, C. Optimization of splash lubrication in the gearbox considering heat transfer performance. Tribology International 2024, 195, 109592. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tošić, M.; Larsson, R.; Stahl, K.; Lohner, T. Thermal elastohydrodynamic analysis of a worm gear. Machines 2023, 11, 89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, J.; He, T.; Wang, D.; Wang, L.; Jiang, S.; Wang, Y.; Chen, K.; Zhang, C.; Shu, K.; Li, Z. Transient mixed thermal elastohydrodynamic lubrication analysis of aero ball bearing under non-steady state conditions. Tribology International 2025, 202, 110342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lv, F.; Zhang, X.; Ji, C.; Rao, Z. Theoretical and experimental investigation on local turbulence effect on mixed-lubrication journal bearing during speeding up. Physics of Fluids 2022, 34, 113104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Torres, T.; Changenet, C.; Touret, T.; Guilbert, B. A new experimental methodology to study convective heat transfer in oil jet lubricated gear units. Lubricants 2023, 11, 408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, S.; Zhang, C. A new deterministic model for mixed lubricated point contact with high accuracy. Journal of Tribology 2021, 143, 102201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jian, G.; Wang, Y.; Luo, H.; Li, Y. Thermal Elastohydrodynamic Lubrication of X-Gears System Based on Time-Varying Meshing Stiffness. Tribology 2020, 40, 21–29. [Google Scholar]

- Yuan, C.; Shen, R.; Dai, Q.; Huang, W.; Wang, X. Influence of Surface Texture on the Isothermal Elastohydrodynamic Lubrication Performance of Gears. Tribology 2025, 45, 1033–1046. [Google Scholar]

- Tortorella, E.; Tedesco, P.; Palma Esposito, F.; January, G.G.; Fani, R.; Jaspars, M.; De Pascale, D. Antibiotics from deep-sea microorganisms: current discoveries and perspectives. Marine drugs 2018, 16, 355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Skropeta, D.; Wei, L. Recent advances in deep-sea natural products. Natural product reports 2014, 31, 999–1025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amano, C.; Zhao, Z.; Sintes, E.; Reinthaler, T.; Stefanschitz, J.; Kisadur, M.; Utsumi, M.; Herndl, G. J. Limited carbon cycling due to high-pressure effects on the deep-sea microbiome. Nature Geoscience 2022, 15, 1041–1047. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Peacock, T.; Ouillon, R. The fluid mechanics of deep-sea mining. Annual Review of Fluid Mechanics 2023, 55, 403–430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scheffer, G.; Gieg, L. M. The mystery of piezophiles: Understudied microorganisms from the deep, dark subsurface. Microorganisms 2023, 11, 1629. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y. N.; Meng, L. H.; Wang, B. G. Progress in research on bioactive secondary metabolites from deep-sea derived microorganisms. Marine Drugs 2020, 18, 614. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paul, V. J.; Ritson-Williams, R.; Sharp, K. Marine chemical ecology in benthic environments. Natural product reports 2011, 28, 345–387. [Google Scholar]

- Sun, D.; Wang, C. A review of open ocean zooplankton ecology. Acta Ecologica Sinica 2017, 37, 3219–3231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wood, R. J. K. Marine wear and tribocorrosion. Wear 2017, 376, 893–910. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Von der Ohe, C. B.; Johnsen, R.; Espallargas, N. Modeling the multi-degradation mechanisms of combined tribocorrosion interacting with static and cyclic loaded surfaces of passive metals exposed to seawater. Wear 2010, 269, 607–616. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Himanshu, G.; Tauheed, M.; Pradeep, K. Review of condition monitoring approaches for ball screws. Advanced Engineering Informatics 2026, 71, 104206. [Google Scholar]

- Bair, S. S.; Andersson, O.; Qureshi, F. S.; Schirru, M. M. New EHL modeling data for the reference liquids squalane and squalane plus polyisoprene. Tribology Transactions 2018, 61, 247–255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boussaid, M.; Haddadine, N.; Benmounah, A.; Dahal, J.; Bouslah, N.; Benaboura, A.; El-Shall, S. Viscosity-boosting effects of polymer additives in automotive lubricants. Polymer Bulletin 2024, 81, 6995–7011. [Google Scholar]

- Su, R.; Cao, W.; Jin, Z.; Wang, Y.; Ding, L.; Maqsood, M.; Wang, D. Deterioration Mechanism and Status Prediction of Hydrocarbon Lubricants under High Temperatures and Humid Environments. Lubricants 2024, 12, 116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, R.; Martinie, L.; Vergne, P.; Joly, L.; Fillo, N. An Approach for Quantitative EHD Friction Prediction Based on Rheological Experiments and Molecular Dynamics Simulations. Tribology Letters 2023, 71, 69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Yu, T.; Ji, H.; Guo, F.; Duan, W.; Liang, P.; Ma, L. Analysis of Water-Lubricated Journal Bearings Assisted by a Small Quantity of Secondary Lubricating Medium with Navier–Stokes Equation and VOF Model. Lubricants 2024, 12, 16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seeton, C. J. Viscosity-temperature correlation for liquids. Tribology Letters 2006, 22, 67–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Levit, R.; Martinez-Garcia, J. C.; Ochoa, D. A.; García, J. The generalized Vogel-Fulcher-Tamman equation for describing the dynamics of relaxer ferroelectrics. Scientific Reports 2019, 9, 12390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bair, S. The unresolved definition of the pressure-viscosity coefficient. Scientific Reports 2022, 12, 3422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andersson, H.; Holmberg, L. J.; Simonsson, K.; Hilding, D.; Schill, M.; Borrvall, T.; Sigfridsson, E.; Leidermark, D. Simulation of leakage flow through dynamic sealing gaps in hydraulic percussion units using a co-simulation approach. Simulation Modelling Practice and Theory 2021, 111, 102351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lei, M.; Yu, K.; Lu, H.; Qi, H. J. Influence of structural relaxation on thermomechanical and shape memory. Polymer 2017, 109, 216–228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gupta, P. K.; Taketa, J.; Price, C. M. Thermal interactions in rolling bearings. Proceedings of the Institution of Mechanical Engineers, Part J: Journal of Engineering Tribology 2020, 234, 1233–1253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ewen, J. P.; Heyes, D. M.; Dini, D. Advances in nonequilibrium molecular dynamics simulations of lubricants and additives. Friction 2018, 6, 349–386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, C.; Schall, D.; Barber, G. Molecular dynamics simulation on the friction properties of confined nanofluids. Materials Today Communications 2023, 34, 105252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hartung, H. A. Density-Temperature-Pressure Relations for Liquid Lubricants. Journal of Fluids Engineering 2022, 78, 941–946. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Z.; Zhou, X.; Huang, Q.; Liu, X.; Wang, L.; Xing, S. Impact of oil-water emulsions on lubrication performance of ship stern bearings. Scientific Reports 2024, 14, 31478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harika, E.; Jarny, S.; Monnet, P.; Bouyer, J.; Fillon, M. Effect of water pollution on rheological properties of lubricating oil. Applied Rheology 2011, 21, 12613. [Google Scholar]

- Ouyang, W.; Yan, Z.; Zhou, X.; Luo, B.; Wang, B.; Huang, J. A thermal hydrodynamic model for emulsified oil-lubricated tilting-pad thrust bearings. Lubricants 2023, 11, 529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tian, Y.; Zhou, J.; He, C.; He, L.; Li, X.; Sui, H. The formation, stabilization and separation of oil-water emulsions: a review. Processes 2022, 10, 738. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Chen, J.; Chen, B.; Yan, F.; Xue, Q. Wear behaviors and wear mechanisms of several alloys under simulated deep-sea environment covering seawater hydrostatic pressure. Tribology International 2012, 56, 38–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Ma, G.; Ma, X.; Li, H.; Guo, P.; Wang, A.; Ke, P. Corrosion and tribocorrosion performance degradation mechanism of multilayered graphite-like carbon (GLC) coatings under deep-sea immersion in the western Pacific. Corrosion Science 2024, 239, 112418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ijaz Malik, M. A.; Kalam, M. A.; Mujtaba, M. A.; Almomani, F. A review of recent advances in the synthesis of environmentally friendly, sustainable, and nontoxic bio-lubricants: Recommendations for the future implementations. Environmental Technology & Innovation 2023, 32, 103366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Litwin, W.; Barszczewska, A.; Piątkowska, E.; Szwoch, I.; Matuszewski, L.; Kahsin, M. Influence of lubrication water contamination by solid particles of mineral origin on marine strut propeller shafts bearings of ships. Polish Maritime Research 2024, 31, 187–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hossain, M. A.; Iqbal, M. A. M.; Julkapli, N. M.; Kong, P. S.; Ching, J. J.; Lee, H. V. Development of catalyst complexes for upgrading biomass into ester-based biolubricants for automotive applications: a review. RSC advances 2018, 8, 5559–5577. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gonon, M.; Philippon, D.; Margueritat, J.; Lafarge, L.; Vergne, P.; Martinie, L. New Insight into the Correlation Between Lubricant Glass Transition and friction Plateau in Highly Loaded Contacts. Tribology Letters 2025, 73, 150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bair, S. The viscosity at the glass transition of a liquid lubricant. Friction 2019, 7, 86–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Conrad, A.; Hodapp, A.; Hochstein, B.; Willenbacher, N.; Jacob, K. H. Low-temperature rheology and thermoanalytical investigation of lubricating oils: Comparison of phase transition, viscosity, and pour point. Lubricants 2021, 9, 99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cui, W.; Chen, H.; Zhao, J.; Ma, Q.; Xu, Q.; Ma, T. Progresses on cryo-tribology: lubrication mechanisms, detection methods and applications. International Journal of Extreme Manufacturing 2023, 5, 022004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, T.; Yang, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Zhao, C. Online Friction-Thermal-Load Coupling Model of an Arbitrary Curve Contact Under Mixed Lubrication Considering Actual Operating Conditions. Journal of Tribology 2022, 144, 112201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chong, W. W. F.; Hamdan, S. H.; Wong, K. J.; Yusup, S. Modelling transitions in regimes of lubrication for rough surface contact. Lubricants 2019, 7, 77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, R.; Hussain ova, I.; Rahmani, R.; Antonov, M. Solid lubrication at high-temperatures-A review. Materials 2022, 15, 1695. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gorbacheva, S. N.; Yadykova, A. Y.; Ilyin, S. O. Rheological and tribological properties of low-temperature greases based on cellulose acetate butyrate gel. Carbohydrate Polymers 2021, 272, 118509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maier, E.; Ziegltrum, A.; Lohner, T.; Stahl, K. Characterization of TEHL contacts of thermoplastic gears. Forschung im Ingenieurwesen 2017, 81, 317–324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y. Y.; Li, Y. R.; Wang, L. Q. Experimental and theoretical studies on the pressure fluctuation of an internal gear pump with a high pressure. Proceedings of the Institution of Mechanical Engineers, Part C: Journal of Mechanical Engineering Science 2019, 233, 987–996. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiao, Z.; Li, Z.; Shi, X.; Zhou, C. Oil Film Damping Analysis in Non-Newtonian Transient Thermal Elastohydrodynamic Lubrication for Gear Transmission. Journal of Applied Mechanics 2018, 85, 035001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duan, Z.; Wu, T.; Glowacz, A.; Gupta, M. K.; Królczyk, G. Analysis of the line contact tribo-lubrication pair and failure mechanism under the extreme conditions. Tribology International 2023, 185, 108505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yin, Z.; Fan, Z.; Jiang, F. Oil film stiffness of double involute gears based on thermal EHL theory. Chinese journal of mechanical engineering 2021, 34, 60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.; Dong, Q.; Shi, X.; Bai, X.; Li, T. An Investigation Into the Thermal Behavior of Planetary Gear Systems Under Mixed Lubrication. Journal of Tribology 2026, 148, 042204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Su, B.; Mao, S.; Zhang, G.; Li, H.; Cui, Y. Dynamics-Based Calculation of the Friction Power Consumption of a Solid Lubricated Bearing in an Ultra-Low Temperature Environment. Lubricants 2023, 11, 372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Wang, B.; Yang, S.; Liao, Y.; Guo, T. Characteristic analysis of mechanical thermal coupling model for bearing rotor system of high-speed train. Applied Mathematics and Mechanics 2022, 43, 1381–1398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, L.; Zhao, Q.; Feng, W.; Xiang, G. On the Film Stiffness Characteristics of Water-Lubricated Rubber Bearings in Deep-Sea Environments. Lubricants 2025, 13, 451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ziegltrum, A.; Lohner, T.; Stahl, K. TEHL simulation on the influence of lubricants on the frictional losses of DLC coated gears. Lubricants 2018, 6, 17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sivayogan, G.; Rahmani, R.; Rahnejat, H. Lubricated loaded tooth contact analysis and non-Newtonian thermoelastohydrodynamics of high-performance spur gear transmission systems. Lubricants 2020, 8, 20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mounayer, J.; Habchi, W. Exact model order reduction for the full-system finite element solution of thermal elastohydrodynamic lubrication problems. Lubricants 2023, 11, 61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yin, Z.; Fan, Z.; Wang, M. Thermal elastohydrodynamic lubrication characteristics of double involute gears at the graded position of tooth waist. Tribology International 2020, 144, 106028. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- MacLaren, A.; Kadiric, A. Elastohydrodynamic Traction and Film Thickness at High Speeds. Tribology Letters 2024, 72, 92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, B.; Mao, Z.; Song, B.; Tian, W.; Wang, Y.; Sundén, B.; Lu, C. Thermal management performance improvement of phase change material for autonomous underwater vehicles’ battery module by optimizing fin design based on quantitative evaluation method. International Journal of Energy Research 2022, 46, 15756–15772. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castaño, T. P.; Velázquez, J. J. L. On the dynamics of thin layers of viscous flows inside another viscous fluid. Journal of Differential Equations 2021, 300, 252–311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kolivand, A.; Li, S.; Zhang, Q. Modeling on contact fatigue under starved lubrication condition. Meccanica 2021, 56, 211–225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, E.; Shao, B.; Qiao, M.; Quan, L.; Wang, C. Influence of Temperature Rise on Local Lubrication and Friction Characteristics of Wet Clutch. Tribology 2024, 44, 831–841. [Google Scholar]

- Fang, J.; Cao, H.; Bai, P.; Meng, Y.; Ma, L.; Tian, Y. High-pressure rheological properties of polyalphaolefin and ester oil blends and their impact on lubrication. Tribology International 2025, 201, 110262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.; Pu, W.; He, T.; Wang, J.; Cao, W. Numerical simulation of transient mixed elastohydrodynamic lubrication for spiral bevel gears. Tribology International 2019, 139, 67–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, X.; Lu, X.; He, T.; Sun, W.; Tong, Q.; Ma, X.; Zhao, B.; Zhu, D. Predictions of friction and flash temperature in marine gears based on a 3D line contact mixed lubrication model considering measured surface roughness. Journal of Central South University 2021, 28, 1570–1583. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amine, G.; Fillot, N.; Philippon, D.; Devaux, N.; Dufils, J.; Macron, E. Dual experimental-numerical study of oil film thickness and friction in a wide elliptical TEHL contact: From pure rolling to opposite sliding. Tribology International 2023, 184, 108466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saxena, A.; Jacobs, G.; König, F.; Reimers, M. Influences of contact parameters on the wear-protective boundary layer formation in rolling-sliding contacts. Wear 2025, 580–581, 206259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruan, J.; Wang, X.; Wang, Y.; Zou, W. Multiscale Fractal Analysis of Thermo-Mechanical Coupling in Textured Tribological Interfaces. Symmetry 2025, 17, 1799. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Z.; Chen, D.; Yuan, C.; Dai, Q.; Huang, W.; Wang, X. State of Art in Tribological Design and Surface Texturing of Gear Surfaces. China Surface Engineering 2024, 37, 61–78. [Google Scholar]

- Xu, J.; Lu, H.; Cai, L.; Liao, Y.; Lian, J. Surface protection technology for metallic materials in marine environments. Materials 2023, 16, 6822. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Braumann, L.; de Viteri, V. S.; Morhard, B.; Lohner, T.; Ochoa, J.; Amri, H. Tribology technologies for gears in loss of lubrication conditions: a review. Journal of Materials Science: Materials in Engineering 2025, 20, 29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arumugaprabu, V.; Ko, T. J.; Kumaran, T.; Kurniawan, R.; Uthayakumar, M. A brief review on importance of surface texturing in materials to improve the tribological performance. Reviews on Advanced Materials Science 2018, 53, 40–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Watanabe, I. A.; Okubo, H.; Nakano, K. In-situ electrical impedance observation for lubrication conditions of gears under actual operation. Tribology International 2025, 210, 110777. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, K.; Yang, X.; Zhang, Y.; Yang, H.; Lv, G.; Gao, Y. Research progress of improving surface friction properties by surface texture technology. The International Journal of Advanced Manufacturing Technology 2021, 116, 2797–2821. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, Q.; Zheng, L.; Zhong, Y.; Wang, S.; Ren, L. Numerical simulation of hydrodynamic lubrication performance for continuous groove-textured surface. Tribology International 2022, 167, 107411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gropper, D.; Wang, L.; Harvey, T. J. Hydrodynamic lubrication of textured surfaces: A review of modeling techniques and key findings. Tribology international 2016, 94, 509–529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, W. H.; Yuan, W.; Guo, Q. J.; Chi, B. T.; Yin, F. S.; Wang, N. N.; Yu, J. Tribological properties of ductile cast iron with in-situ textures created through abrasive grinding and laser surface ablation. Tribology International 2024, 200, 110134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yin, H.; Zhang, X.; Guo, Z.; Xu, Y.; Rao, X.; Yuan, C. Synergetic effects of surface textures with modified copper nanoparticles lubricant additives on the tribological properties of cylinder liner-piston ring. Tribology International 2023, 178, 108085. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vishnoi, M.; Kumar, P.; Murtaza, Q. Surface texturing techniques to enhance tribological performance: A review. Surfaces and Interfaces 2021, 27, 101463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, Z. H.; Wang, F. C.; Chen, Z. G.; Ruan, X. P.; Zeng, H. H.; Wang, J. H.; An, Y. R.; Fan, X. L. Numerical simulation of lubrication performance on chevron textured surface under hydrodynamic lubrication. Tribology International 2021, 154, 106704. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mao, B.; Siddaiah, A.; Liao, Y. L.; Menezes, P. L. Laser surface texturing and related techniques for enhancing tribological performance of engineering materials: A review. Journal of Manufacturing Processes 2020, 53, 153–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maldonado-Cortés, D.; Peña-Parás, L.; Martínez, N. R.; Leal, M. P.; Correa, D. I. Q. Tribological characterization of different geometries generated with laser surface texturing for tooling applications. Wear 2021, 477, 203856. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moradi, M.; Arabi, H.; Nasab, S. J.; Benyounis, K. Y. A comparative study of laser surface hardening of AISI 410 and 420 martensitic stainless steels by using diode laser. Optics & Laser Technology 2019, 111, 347–357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.; Ye, R.; Xiang, J. The performance of textured surface in friction reducing: A review. Tribology International 2023, 177, 108010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, X.; Renqing, D.; Liao, L.; Zhu, P.; Lin, B.; Huang, Y.; Luo, S. Study on hydrodynamic lubrication and friction reduction performance of spur gear with groove texture. Tribology International 2023, 177, 107978. [Google Scholar]

- Lei, P. X.; Zhang, P. L.; Song, S. J.; Liu, Z. Y.; Yan, H.; Sun, T. Z.; Lu, Q. H.; Chen, Y.; Gromov, V.; Shi, H. C. Research status of laser surface texturing on tribological and wetting properties of materials: A review. Optik 2024, 298, 171581. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, Z.; Li, J.; Zou, T.; Hou, W.; An, Y.; Liu, J. Effect of bionic texture on wear resistance and heat dissipation performance of transmission gear. Tribology Transactions 2025, 68, 531–557. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Luo, S.; Gao, T.; Mo, J.; Wang, D.; Chang, X. Biomimetic Hexagonal Texture with Dual-Orientation Groove Interconnectivity Enhances Lubrication and Tribological Performance of Gear Tooth Surfaces. Lubricants 2025, 13, 420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.; Wang, S.; Wang, S.; Xiao, Y.; Dong, J.; Xuan, Y.; Zhang, L.; Wang, H. Study on the Influence of Tooth Surface Micro-texture on Dynamic Characteristics of Face Gear. Advances in Mechanical Transmission: Innovations and Applications 2026, 798–809, (icmt-2 2025. Lecture Notes in Mechanical Engineering. Springer, Singapore.).

- Zhao, T.; Wang, Y.; He, Y.; Zhu, Y.; Li, M. Numerical simulation and experimental investigation on tribological properties of gear alloy surface biomimetic texture. Tribology Transactions 2023, 66, 610–622. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gupta, N.; Tandon, N.; Pandey, R. K. An exploration of the performance behaviors of lubricated textured and conventional spur gearsets. Tribology International 2018, 128, 376–385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gupta, N.; Tandon, N.; Pandey, R. K.; Vidyasagar, K. E. C.; Kalyanasundaram, D. Tribological and vibration studies of textured spur gear pairs under fully flooded and starved lubrication conditions. Tribology Transactions 2020, 63, 1103–1120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gupta, N.; Tandon, N.; Pandey, R. K.; Vidyasagar, K. E. C.; Kalyanasundaram, D. Tribodynamic studies of textured gearsets lubricated with fresh and MoS2 blended greases. Tribology International 2022, 165, 107247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, J. P.; Han, J.; Tian, X. Q.; Li, Z. F.; You, T. F.; Li, G. H.; Xia, L. Flexible modification and texture prediction and control method of internal gearing power honing tooth surface. Advances in Manufacturing 2024, 13, 784–798. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, B.; Sun, L.; Zhao, N.; Li, J. Applications of laser surface treatment in gears: a review. Journal of Materials Engineering and Performance 2025, 34, 1–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Z.; Zhou, J.; Liu, B.; Fu, H.; Meng, X.; Ji, J.; Zhang, Y.; Hua, X.; Xu, X.; Fu, Y. Meshing frictional characteristics of spur gears under dry friction and heavy loads: Effects of the preset pitting-like micro-textures array. Tribology International 2023, 180, 108296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, R.; Pradhan, S.; Bathe, R. N. Design and fabrication of honeycomb micro-texture using femtosecond laser machine. Materials and Manufacturing Processes 2021, 36, 1314–1322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salguero, J.; Del Sol, I.; Vazquez-Martinez, J. M.; Schertzer, M. J.; Iglesias, P. Effect of laser parameters on the tribological behavior of Ti6Al4V titanium microtextures under lubricated conditions. Wear 2019, 426-427, 1272–1279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, Y.; Yu, J.; Geng, J.; Abuflaha, R.; Olson, D.; Hu, X.; Tysoe, W. T. Characterization of the tribological behavior of the textured steel surfaces fabricated by photolithographic etching. Tribology Letters 2018, 66, 55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, Y.; Zheng, Q.; Abuflaha, R.; Olson, D.; Furlong, O.; You, T.; Zhang, Q.; Hu, X.; Tysoe, W. T. Influence of dimple shape on tribofilm formation and tribological properties of textured surfaces under full and starved lubrication. Tribology International 2019, 136, 267–275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brăileanu, P. I.; Mocanu, M.-T.; Dobrescu, T. G.; Pascu, N. E.; Dobrotă, D. Structure and Texture Synergies in Fused Deposition Modeling (FDM) Polymers: A Comparative Evaluation of Tribological and Mechanical Properties. Polymers 2025, 17, 2159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, W.; Tang, J.; Rong, K.; Li, Z.; Shao, W. A parametric evaluation model of abrasive interaction for predicting tooth rough surface in spiral bevel gear grinding. Journal of Manufacturing Processes 2024, 132, 659–676. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fu, Y.; Gao, H.; Yan, Q.; Wang, X.; Wang, X. An efficient approach to improving the finishing properties of abrasive flow machining with the analyses of initial surface texture of workpiece. The International Journal of Advanced Manufacturing Technology 2020, 107, 2417–2432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jagadish; Bhowmik, S.; Ray, A. Prediction of surface roughness quality of green abrasive water jet machining: a soft computing approach. Journal of Intelligent Manufacturing 2019, 30, 2965–2979. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Natarajan, Y.; Murugesan, P. K.; Mohan, M.; Ali Khan, S. A. L. Abrasive Water Jet Machining process: A state of art of review. Journal of Manufacturing Processes 2020, 49, 271–322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, L.; Fang, Y.; Dai, Q.; Huang, W.; Wang, X. Surface texturing on SiC by multiphase jet machining with microdiamond abrasives. Materials and Manufacturing Processes 2017, 33, 1415–1421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hong, Y.; Zhang, P.; Lee, K. H.; Lee, C. H. Friction and wear of textured surfaces produced by 3D printing. Science China Technological Sciences 2017, 60, 1400–1406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naat, N.; Boutar, Y.; Mezlini, S.; de Silva, L. F. M.; Alrasheedi, N. H.; Hajlaoui, K. Study of the effect of bio-inspired surface texture on the shear strength of bonded 3D-printed materials: Comparison between stainless steel and polycarbonate joints. International Journal of Adhesion and Adhesives 2024, 131, 103658. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, S.; Parmar, U. The Effects of Microdimple Texture on the Friction and Thermal Behavior of a Point Contact. ASME. J. Tribol. 2018, 140, 041503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wos, S.; Koszela, W.; Pawlus, P. Comparing tribological effects of various chevron-based surface textures under lubricated unidirectional sliding. Tribology International 2020, 146, 106205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petare, A.; Deshwal, G.; Palani, I. A; Jain, N. K. Laser texturing of helical and straight bevel gears to enhance finishing performance of AFF process. The International Journal of Advanced Manufacturing Technology 2020, 110, 2221–2238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Z.; Chen, J.; Shen, J.; Liu, K. Elastic Deformation of Surface Topography under Line Contact and Sliding-rolling Conditions. Journal of Mechanical Engineering 2018, 54, 142–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, J.; Li, Z.; Zhang, H.; Zhu, R. Effect of micro-textures on lubrication characteristics of spur gears under 3D line-contact EHL model. Industrial Lubrication and Tribology 2021, 73, 1132–1145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petare, A. C.; Mishra, A.; Palani, I. A.; Jain, N. K. Study of laser texturing assisted abrasive flow finishing for enhancing surface quality and microgeometry of spur gears. The International Journal of Advanced Manufacturing Technology 2018, 101, 785–799. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pei, X.; Pu, W.; Zhang, Y.; Huang, L. Surface topography and friction coefficient evolution during sliding wear in a mixed lubricated rolling-sliding contact. Tribology International 2019, 137, 303–312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morales-Espejel, G. E.; Rycerz, P.; Kadiric, A. Prediction of micropitting damage in gear teeth contacts considering the concurrent effects of surface fatigue and mild wear. Wear 2018, 398-399, 99–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Yan, Z.; Fang, X.; Shen, Z.; Pan, X. Observation and experimental investigation on cavitation effect of friction pair surface texture. Lubrication Science 2020, 32, 404–414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiao, H.; Zhang, F.; Li, Z.; Tang, Y.; Li, L. Gear tribological and contact fatigue prediction with rough topography and groove texture under elastohydrodynamic lubrication. Meccanica 2025, 60, 2641–2669. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, L.; Yang, C.; Sheng, Y. Y. Wear model based on real-time surface roughness and its effect on lubrication regimes. Tribology International 2018, 126, 16–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, G.; Ma, J.; Li, J.; Sun, K.; Wang, K.; Wang, Y. Study on the dynamic characteristics of gears considering surface topography in a mixed lubrication state. Lubricants 2023, 12, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruan, J.; Wang, X.; Wang, Y.; Chen, L. Study on anti-scuffing load-bearing thermoelastic lubricating properties of meshing gears with contact interface micro-texture morphology. Journal of Tribology 2022, 144, 101202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).