Submitted:

04 February 2026

Posted:

05 February 2026

You are already at the latest version

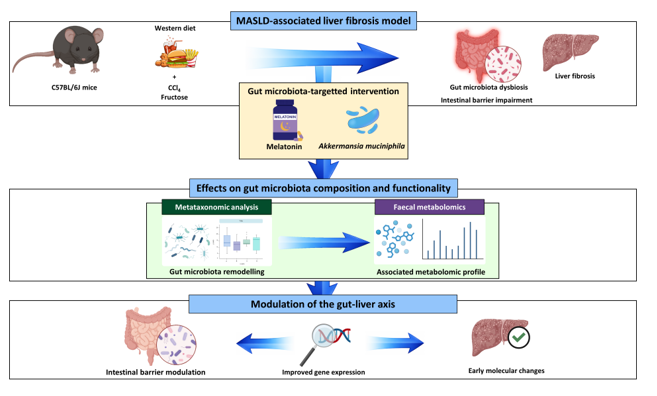

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Experimental Design

2.2. Sample Collection

2.3. Biochemical Analysis

2.4. Histopathology

2.5. Gene Expression Analysis

2.6. Gut Microbiota Compositional Analysis

2.7. Faecal Metabolomic Analysis

2.8. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Western Diet Induces Metabolic and Histological Alterations and Hepatic and Intestinal Gene Expression Deregulation

3.2. Melatonin and A. muciniphila Exert Limited Biochemical and Histological Effects but Induce Hepatic and Intestinal Gene Expression Changes

3.3. Melatonin and A. muciniphila Modulate Gut Microbiota Diversity and Composition After WD-induced Dysbiosis

3.4. Melatonin and A. muciniphila Partially Restore WD-impaired Gut Microbiota Functionality

3.5. Correlation Analyses Reveal Interactions Between Host Biochemical and Molecular Markers, Gut Microbiota Composition and Faecal Metabolomic Profiles

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Chan, W.-K.; Chuah, K.-H.; Rajaram, R.B.; Lim, L.-L.; Ratnasingam, J.; Vethakkan, S.R. Metabolic Dysfunction-Associated Steatotic Liver Disease (MASLD): A State-of-the-Art Review. J Obes Metab Syndr 2023, 32, 197–213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miao, L.; Targher, G.; Byrne, C.D.; Cao, Y.-Y.; Zheng, M.-H. Current Status and Future Trends of the Global Burden of MASLD. Trends Endocrinol Metab 2024, 35, 697–707. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ha, S.; Wai-Sun Wong, V.; Zhang, X.; Yu, J. Interplay between Gut Microbiome, Host Genetic and Epigenetic Modifications in MASLD and MASLD-Related Hepatocellular Carcinoma. Gut 2024, 0, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tanwar, S.; Rhodes, F.; Srivastava, A.; Trembling, P.M.; Rosenberg, W.M. Inflammation and Fibrosis in Chronic Liver Diseases Including Non-Alcoholic Fatty Liver Disease and Hepatitis C. World J Gastroenterol 2020, 26, 109–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aydın, M.M.; Akçalı, K.C. Liver Fibrosis. Turk J Gastroenterol 2018, 29, 14–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mitra, S.; De, A.; Chowdhury, A. Epidemiology of Non-Alcoholic and Alcoholic Fatty Liver Diseases. Transl Gastroenterol Hepatol 2020, 5, 16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saenz, E.; Montagut, N.E.; Wang, B.; Stein-Thöringer, C.; Wang, K.; Weng, H.; Ebert, M.; Schneider, K.M.; Li, L.; Teufel, A. Manipulating the Gut Microbiome to Alleviate Steatotic Liver Disease: Current Progress and Challenges. Engineering 2024, 40, 51–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martin-Grau, M.; Monleón, D. The Role of Microbiota-Related Co-Metabolites in MASLD Progression: A Narrative Review. Curr Issues Mol Biol 2024, 46, 6377–6389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, R.; Yan, Z.; Zhong, H.; Luo, R.; Liu, W.; Xiong, S.; Liu, Q.; Liu, M. Gut Microbial Metabolites in MASLD: Implications of Mitochondrial Dysfunction in the Pathogenesis and Treatment. Hepatol Commun 2024, 8, e0484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benedé-Ubieto, R.; Cubero, F.J.; Nevzorova, Y.A. Breaking the Barriers: The Role of Gut Homeostasis in Metabolic-Associated Steatotic Liver Disease (MASLD). Gut Microbes 2024, 16, 2331460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vallianou, N.G.; Kounatidis, D.; Psallida, S.; Vythoulkas-Biotis, N.; Adamou, A.; Zachariadou, T.; Kargioti, S.; Karampela, I.; Dalamaga, M. NAFLD/MASLD and the Gut–Liver Axis: From Pathogenesis to Treatment Options. Metabolites 2024, 14, 366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, J.I.; Cheon, H.G. Melatonin Ameliorates Hepatic Fibrosis via the Melatonin Receptor 2-Mediated Upregulation of BMAL1 and Anti-Oxidative Enzymes. Eur J Pharmacol 2024, 966, 176337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ahmand, S.B.; Ali, A.; Bilal, M.; Rashid, S.M.; Wani, A.B.; Bhat, R.R.; Rehman, M.U. Melatonin and Health: Insights of Melatonin Action, Biological Functions, and Associated Disorders. Cell Mol Neurobiol 2023, 43, 2437–2458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Iesanu, M.I.; Zahiu, C.D.M.; Dogaru, I.-A.; Chitimus, D.M.; Pircalabioru, G.G.; Voiculescu, S.E.; Isac, S.; Galos, F.; Pavel, B.; O’Mahony, S.M.; et al. Melatonin–Microbiome Two-Sided Interaction in Dysbiosis-Associated Conditions. Antioxidants 2022, 11, 2244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- LeFort, K.R.; Rungratanawanich, W.; Song, B.-J. Melatonin Prevents Alcohol- and Metabolic Dysfunction- Associated Steatotic Liver Disease by Mitigating Gut Dysbiosis, Intestinal Barrier Dysfunction, and Endotoxemia. Antioxidants 2023, 13, 43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, Y.; Li, L.; Wang, B. Role of Akkermansia Muciniphila in the Development of Nonalcoholic Fatty Liver Disease: Current Knowledge and Perspectives. Front Med 2022, 16, 667–685. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Derrien, M.; Vaughan, E.E.; Plugge, C.M.; de Vos, W.M. Akkermansia Muciniphila Gen. Nov., Sp. Nov., a Human Intestinal Mucin-Degrading Bacterium. Int J Syst Evol Microbiol 2004, 54, 1469–1476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pai, R.K. NAFLD Histology: A Critical Review and Comparison of Scoring Systems. Curr Hepatology Rep 2019, 18, 473–481. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Porras, D.; Nistal, E.; Martínez-Flórez, S.; Pisonero-Vaquero, S.; Olcoz, J.L.; Jover, R.; González-Gallego, J.; García-Mediavilla, M.V.; Sánchez-Campos, S. Protective Effect of Quercetin on High-Fat Diet-Induced Non-Alcoholic Fatty Liver Disease in Mice Is Mediated by Modulating Intestinal Microbiota Imbalance and Related Gut-Liver Axis Activation. Free Radic Biol Med 2017, 102, 188–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Porras, D.; Nistal, E.; Martínez-Flórez, S.; Olcoz, J.L.; Jover, R.; Jorquera, F.; González-Gallego, J.; García-Mediavilla, M.V.; Sánchez-Campos, S. Functional Interactions between Gut Microbiota Transplantation, Quercetin, and High-Fat Diet Determine Non-Alcoholic Fatty Liver Disease Development in Germ-Free Mice. Mol Nutr Food Res 2019, 63, 1800930. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Babraham Bioinformatics. FastQC, version 0.11.9; A quality control tool for high throughput sequence data; Babraham Institute: United Kingdom, 2020.

- Caporaso, J.G.; Kuczynski, J.; Stombaugh, J.; Bittinger, K.; Bushman, F.D.; Costello, E.K.; Fierer, N.; Peña, A.G.; Goodrich, J.K.; Gordon, J.I.; et al. QIIME Allows Analysis of High-Throughput Community Sequencing Data. Nat Methods 2010, 7, 335–336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Callahan, B.J.; McMurdie, P.J.; Rosen, M.J.; Han, A.W.; Johnson, A.J.A.; Holmes, S.P. DADA2: High-Resolution Sample Inference from Illumina Amplicon Data. Nat Methods 2016, 13, 581–583. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vidal-Cevallos, P.; Sorroza-Martínez, A.P.; Chávez-Tapia, N.C.; Uribe, M.; Montalvo-Javé, E.E.; Nuño-Lámbarri, N. The Relationship between Pathogenesis and Possible Treatments for the MASLD-Cirrhosis Spectrum. Int J Mol Sci 2024, 25, 4397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zazueta, A.; Valenzuela-Pérez, L.; Ortiz-López, N.; Pinto-León, A.; Torres, V.; Guiñez, D.; Aliaga, N.; Merino, P.; Sandoval, A.; Covarrubias, N.; et al. Alteration of Gut Microbiota Composition in the Progression of Liver Damage in Patients with Metabolic Dysfunction-Associated Steatotic Liver Disease (MASLD). Int J Mol Sci 2024, 25, 4387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soto, A.; Spongberg, C.; Martinino, A.; Giovinazzo, F. Exploring the Multifaceted Landscape of MASLD: A Comprehensive Synthesis of Recent Studies, from Pathophysiology to Organoids and Beyond. Biomedicines 2024, 12, 397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guan, Q.; Wang, Z.; Cao, J.; Dong, Y.; Chen, Y. Mechanisms of Melatonin in Obesity: A Review. Int J Mol Sci 2021, 23, 218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yin, J.; Li, Y.; Han, H.; Chen, S.; Gao, J.; Liu, G.; Wu, X.; Deng, J.; Yu, Q.; Huang, X.; et al. Melatonin Reprogramming of Gut Microbiota Improves Lipid Dysmetabolism in High-Fat Diet-Fed Mice. J Pineal Res 2018, 65, e12524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hong, F.; Pan, S.; Xu, P.; Xue, T.; Wang, J.; Guo, Y.; Jia, L.; Qiao, X.; Li, L.; Zhai, Y. Melatonin Orchestrates Lipid Homeostasis through the Hepatointestinal Circadian Clock and Microbiota during Constant Light Exposure. Cells 2020, 9, 489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, P.; Wang, J.; Hong, F.; Wang, S.; Jin, X.; Xue, T.; Jia, L.; Zhai, Y. Melatonin Prevents Obesity through Modulation of Gut Microbiota in Mice. J Pineal Res 2017, 62, e12399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Juárez-Fernández, M.; Porras, D.; Petrov, P.; Román-Sagüillo, S.; García-Mediavilla, M.V.; Soluyanova, P.; Martínez-Flórez, S.; González-Gallego, J.; Nistal, E.; Jover, R.; et al. The Synbiotic Combination of Akkermansia Muciniphila and Quercetin Ameliorates Early Obesity and NAFLD through Gut Microbiota Reshaping and Bile Acid Metabolism Modulation. Antioxidants 2021, 10, 2001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keshavarz Azizi Raftar, S.; Ashrafian, F.; Yadegar, A.; Lari, A.; Moradi, H.R.; Shahriary, A.; Azimirad, M.; Alavifard, H.; Mohsenifar, Z.; Davari, M.; et al. The Protective Effects of Live and Pasteurized Akkermansia Muciniphila and Its Extracellular Vesicles against HFD/CCl4-Induced Liver Injury. Microbiol Spectr 9 e00484-21. [CrossRef]

- Cinar, C.; Altinoz, E.; Elbe, H.; Bicer, Y.; Cetinavci, D.; Ozturk, I.; Colak, T. Therapeutic Effect of Melatonin on CCl4-Induced Fibrotic Liver Model by Modulating Oxidative Stress, Inflammation, and TGF-Β1 Signaling Pathway in Pinealectomized Rats. Inflammation 2025, 48, 1093–1108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sun, H.; Wang, X.; Chen, J.; Song, K.; Gusdon, A.M.; Li, L.; Bu, L.; Qu, S. Melatonin Improves Non-Alcoholic Fatty Liver Disease via MAPK-JNK/P38 Signaling in High-Fat-Diet-Induced Obese Mice. Lipids Health Dis 2016, 15, 202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wu, W.; Lv, L.; Shi, D.; Ye, J.; Fang, D.; Guo, F.; Li, Y.; He, X.; Li, L. Protective Effect of Akkermansia Muciniphila against Immune-Mediated Liver Injury in a Mouse Model. Front Microbiol 2017, 8, 1804. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Qu, D.; Chen, M.; Zhu, H.; Liu, X.; Cui, Y.; Zhou, W.; Zhang, M. Akkermansia Muciniphila and Its Outer Membrane Protein Amuc_1100 Prevent High-Fat Diet-Induced Nonalcoholic Fatty Liver Disease in Mice. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 2023, 684, 149131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saha, M.; Manna, K.; Saha, K.D. Melatonin Suppresses NLRP3 Inflammasome Activation via TLR4/NF-κB and P2X7R Signaling in High-Fat Diet-Induced Murine NASH Model. J Inflamm Res 2022, 15, 3235–3258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El-Sayed, S.M.; El-Sayed, G.A.; Mansour, M.A.; Ahmed, H.E.; Kamar, S.A. A Comparative Study on the Effect of Melatonin and Orlistat Combination versus Orlistat Alone on High Fat Diet-Induced Hepatic Changes in the Adult Male Albino Rats (a Histological and Morphometric Study). Ultrastruc Pathol 2025, 49, 20–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Machado-de Oliveira, J.; Lima-Pace, F.H.; de Faria-Ghetti, F.; Bastos-Dias-Barbosa, K.V.; Evangelista-Cesar, D.; Fonseca-Chebli, J.M.; Villela-Vieira-de Castro-Ferreira, L.E. Non-Alcoholic Steatohepatitis: Comparison of Intestinal Microbiota between Different Metabolic Profiles. A Pilot Study. J Gastrointestin Liver Dis 2020, 29, 369–376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moraes-Miguel, F.; Nascimiento-Picada, J.; Bondan-da Silva, J.; Gonçalves-Schemitt, E.; Raskopt-Colares, J.; Minuzzo-Hartmann, R.; Marroni, C.A.; Possa-Marroni, N. Melatonin Attenuates Inflammation, Oxidative Stress, and DNA Damage in Mice with Nonalcoholic Steatohepatitis Induced by a Methionine- and Choline-Deficient Diet. Inflammation 2022, 45, 1968–1984. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, F.; Wu, X.; Zhang, Q.; Li, Y.; Ye, Y.; Li, P.; Chen, S.; Peng, Y.; Hardeland, R.; Xia, Y. Bacteriostatic Potential of Melatonin: Therapeutic Standing and Mechanistic Insights. Front Immunol 2021, 12, 683879. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, S.; Kang, W.; Mao, X.; Ge, L.; Du, H.; Li, J.; Hou, L.; Liu, D.; Yin, Y.; Liu, Y.; et al. Melatonin Mitigates Aflatoxin B1-Induced Liver Injury via Modulation of Gut Microbiota/Intestinal FXR/Liver TLR4 Signaling Axis in Mice. J Pineal Res 2022, 73, e12812. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gao, T.; Wang, Z.; Dong, Y.; Cao, J.; Chen, Y. Melatonin-Mediated Colonic Microbiota Metabolite Butyrate Prevents Acute Sleep Deprivation-Induced Colitis in Mice. Int J Mol Sci 2021, 22, 11894. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martin-Gallausiaux, C.; Garcia-Weber, D.; Lashermes, A.; Larraufie, P.; Marinelli, L.; Teixeira, V.; Rolland, A.; Béguet-Crespel, F.; Brochard, V.; Quatremare, T.; et al. Akkermansia Muciniphila Upregulates Genes Involved in Maintaining the Intestinal Barrier Function via ADP-Heptose-Dependent Activation of the ALPK1/TIFA Pathway. Gut Microbes 2022, 14, 2110639. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aron-Wisnewsky, J.; Vigliotti, C.; Witjes, J.; Le, P.; Holleboom, A.G.; Verheij, J.; Nieuwdorp, M.; Clément, K. Gut Microbiota and Human NAFLD: Disentangling Microbial Signatures from Metabolic Disorders. Nat Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol 2020, 17, 279–297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, Z.; Ni, M.; Yu, H.; Wang, L.; Zhou, X.; Chen, T.; Liu, G.; Gao, Y. Gut Microbiota and Liver Fibrosis: One Potential Biomarker for Predicting Liver Fibrosis. Biomed Res Int 2020, 2020, 3905130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gong, S.; Ye, T.; Wang, M.; Wang, M.; Li, Y.; Ma, L.; Yang, Y.; Wang, Y.; Zhao, X.; Liu, L.; et al. Traditional Chinese Medicine Formula Kang Shuai Lao Pian Improves Obesity, Gut Dysbiosis, and Fecal Metabolic Disorders in High-Fat Diet-Fed Mice. Front Pharmacol 2020, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Xiao, Y.; Song, L.; Huang, Y.; Chu, Q.; Zhu, S.; Lu, S.; Hou, L.; Li, Z.; Li, J.; et al. Effect of Lactobacillus Plantarum HT121 on Serum Lipid Profile, Gut Microbiota, and Liver Transcriptome and Metabolomics in a High-Cholesterol Diet–Induced Hypercholesterolemia Rat Model. Nutrition 2020, 79–80, 110966. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bao, T.; He, F.; Zhang, X.; Zhu, L.; Wang, Z.; Lu, H.; Wang, T.; Li, Y.; Yang, S.; Wang, H. Inulin Exerts Beneficial Effects on Non-Alcoholic Fatty Liver Disease via Modulating Gut Microbiome and Suppressing the Lipopolysaccharide-Toll-Like Receptor 4-Mψ-Nuclear Factor-κB-Nod-Like Receptor Protein 3 Pathway via Gut-Liver Axis in Mice. Front Pharmacol 2020, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhuge, A.; Li, S.; Lou, P.; Wu, W.; Wang, K.; Yuan, Y.; Xia, J.; Li, B.; Li, L. Longitudinal 16S rRNA Sequencing Reveals Relationships among Alterations of Gut Microbiota and Nonalcoholic Fatty Liver Disease Progression in Mice. Microbiol Spectr 10 e00047-22. [CrossRef]

- Duan, R.; Huang, K.; Guan, X.; Li, S.; Xia, J.; Shen, M.; Sun, Z.; Yu, Z. Tectorigenin Ameliorated High-Fat Diet-Induced Nonalcoholic Fatty Liver Disease through Anti-Inflammation and Modulating Gut Microbiota in Mice. Food Chem Toxicol 2022, 164, 112948. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, J.; Sun, H.; Yang, Y.; Yan, Y. Sesamolin Alleviates Nonalcoholic Fatty Liver Disease through Modulating Gut Microbiota and Metabolites in High-Fat and High-Fructose Diet-Fed Mice. Int J Mol Sci 2022, 23, 13853. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ranea-Robles, P.; Houten, S.M. The Biochemistry and Physiology of Long-Chain Dicarboxylic Acid Metabolism. Biochem J 2023, 480, 607–627. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hashemi, M.; Hoshyar, R.; Ande, S.R.; Chen, Q.M.; Solomon, C.; Zuse, A.; Naderi, M. Mevalonate Cascade and Its Regulation in Cholesterol Metabolism in Different Tissues in Health and Disease. Curr Mol Pharmacol 10 13–26. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jabłońska-Trypuć, A.; Pankiewicz, W.; Czerpak, R. Traumatic Acid Reduces Oxidative Stress and Enhances Collagen Biosynthesis in Cultured Human Skin Fibroblasts. Lipids 2016, 51, 1021–1035. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuley, R.; Stultz, R.D.; Duvvuri, B.; Wang, T.; Fritzler, M.J.; Hesselstrand, R.; Nelson, J.L.; Lood, C. N-Formyl Methionine Peptide-Mediated Neutrophil Activation in Systemic Sclerosis. Front Immunol 2022, 12, 785275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Michailidou, D.; Duvvuri, B.; Kuley, R.; Cuthbertson, D.; Grayson, P.C.; Khalidi, N.A.; Koening, C.L.; Langford, C.A.; McAlear, C.A.; Moreland, L.W.; et al. Neutrophil Activation in Patients with Anti-Neutrophil Cytoplasmic Autoantibody-Associated Vasculitis and Large-Vessel Vasculitis. Arthritis ResTher 2022, 24, 160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sánchez-Medina, A.; Redondo-Puente, M.; Dupak, R.; Bravo-Clemente, L.; Goya, L.; Sarriá, B. Colonic Coffee Phenols Metabolites, Dihydrocaffeic, Dihydroferulic, and Hydroxyhippuric Acids Protect Hepatic Cells from TNF-α-Induced Inflammation and Oxidative Stress. Int J Mol Sci 2023, 24, 1440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Larrosa, M.; Luceri, C.; Vivoli, E.; Pagliuca, C.; Lodovici, M.; Moneti, G.; Dolara, P. Polyphenol Metabolites from Colonic Microbiota Exert Anti-Inflammatory Activity on Different Inflammation Models. Mol Nutr Food Res 2009, 53, 1044–1054. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, T.; Wang, R.; Duan, Z.; Yuan, X.; Ding, Y.; Feng, Z.; Bu, F.; Liu, L.; Wang, Q.; Zhou, J.; et al. Akkermansia Muciniphila Protects Against Psychological Disorder-Induced Gut Microbiota-Mediated Colonic Mucosal Barrier Damage and Aggravation of Colitis. Front Cell Infect Microbiol 2021, 11, 723856. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, M.; Han, H.; Wan, F.; Zhong, R.; Do, Y.J.; Oh, S.-I.; Lu, X.; Liu, L.; Yi, B.; Zhang, H. Dihydroquercetin Supplementation Improved Hepatic Lipid Dysmetabolism Mediated by Gut Microbiota in High-Fat Diet (HFD)-Fed Mice. Nutrients 2022, 14, 5214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carvalho, J.L.; Miranda, M.; Fialho, A.K.; Castro-Faria-Neto, H.; Anatriello, E.; Keller, A.C.; Aimbire, F. Oral Feeding with Probiotic Lactobacillus Rhamnosus Attenuates Cigarette Smoke-Induced COPD in C57Bl/6 Mice: Relevance to Inflammatory Markers in Human Bronchial Epithelial Cells. PLoS ONE 2020, 15, e0225560. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, K.; Wu, W.; Jiang, X.; Xia, J.; Lv, L.; Li, S.; Zhuge, A.; Wu, Z.; Wang, Q.; Wang, S.; et al. Multi-Omics Analysis Reveals the Protection of Gasdermin D in Concanavalin A-Induced Autoimmune Hepatitis. Microbiol Spectr 2022, 10, e01717-22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wan, M.; Li, Q.; Lei, Q.; Zhou, D.; Wang, S. Polyphenols and Polysaccharides from Morus Alba L. Fruit Attenuate High-Fat Diet-Induced Metabolic Syndrome Modifying the Gut Microbiota and Metabolite Profile. Foods 2022, 11, 1818. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hu, Y.; Zhou, J.; Lin, X. Akkermansia Muciniphila Helps in the Recovery of Lipopolysaccharide-Fed Mice with Mild Intestinal Dysfunction. Front Microbiol 2025, 16, 1523742. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, L.; Wu, L.; Jiang, T.; Liang, T.; Yang, L.; Li, Y.; Gao, H.; Zhang, J.; Xie, X.; Wu, Q. Lactiplantibacillus Plantarum 124 Modulates Sleep Deprivation-Associated Markers of Intestinal Barrier Dysfunction in Mice in Conjunction with the Regulation of Gut Microbiota. Nutrients 2023, 15, 4002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, L.; Jiang, Y.; Yu, Q.; Xiao, C.; Sun, J.; Weng, L.; Qiu, Y. Gentiopicroside Improves High-Fat Diet-Induced NAFLD in Association with Modulation of Host Serum Metabolome and Gut Microbiome in Mice. Front Microbiol 2023, 14, 1145430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodriguez-Diaz, C.; Taminiau, B.; García-García, A.; Cueto, A.; Robles-Díaz, M.; Ortega-Alonso, A.; Martín-Reyes, F.; Daube, G.; Sanabria-Cabrera, J.; Jimenez-Perez, M.; et al. Microbiota Diversity in Nonalcoholic Fatty Liver Disease and in Drug-Induced Liver Injury. Pharmacol Res 2022, 182, 106348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bacil, G.P.; Romualdo, G.R.; Rodrigues, J.; Barbisan, L.F. Indole-3-Carbinol and Chlorogenic Acid Combination Modulates Gut Microbiome and Attenuates Nonalcoholic Steatohepatitis in a Murine Model. Food Res Int 2023, 174, 113513. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ran, X.; Wang, Y.; Li, S.; Dai, C. Effects of Bifidobacterium and Rosuvastatin on Metabolic-Associated Fatty Liver Disease via the Gut–Liver Axis. Lipids Health Dis 2024, 23, 401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, W.; Chen, X.; Wu, S.; Jin, L.; Chen, X.; Mao, G.; Wan, X.; Xing, W. Monascus Red Pigments Alleviate High-Fat and High-Sugar Diet-Induced NAFLD in Mice by Modulating the Gut Microbiota and Metabolites. Food Sci Nutr 2024, 12, 5762–5775. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, D.; Zhang, J.; Xiao, C.; Mo, C.; Ding, B.-S. Trimethylamine-N-Oxide (TMAO) Mediates the Crosstalk between the Gut Microbiota and Hepatic Vascular Niche to Alleviate Liver Fibrosis in Nonalcoholic Steatohepatitis. Front Immunol 2022, 13, 964477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- León-Mimila, P.; Villamil-Ramírez, H.; Li, X.S.; Shih, D.M.; Hui, S.T.; Ocampo-Medina, E.; López-Contreras, B.; Morán-Ramos, S.; Olivares-Arevalo, M.; Grandini-Rosales, P.; et al. Trimethylamine N-Oxide Levels Are Associated with NASH in Obese Subjects with Type 2 Diabetes. Diabetes Metab 2021, 47, 101183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Imajo, K.; Fujita, K.; Yoneda, M.; Shinohara, Y.; Suzuki, K.; Mawatari, H.; Takahashi, J.; Nozaki, Y.; Sumida, Y.; Kirikoshi, H.; et al. Plasma Free Choline Is a Novel Non-Invasive Biomarker for Early-Stage Non-Alcoholic Steatohepatitis: A Multi-Center Validation Study. Hepatol Res 2012, 42, 757–766. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Luo, Y.; Peng, S.; Cheng, J.; Yang, H.; Lin, L.; Yang, G.; Jin, Y.; Wang, Q.; Wen, Z. Chitosan-Stabilized Selenium Nanoparticles Alleviate High-Fat Diet-Induced Non-Alcoholic Fatty Liver Disease (NAFLD) by Modulating the Gut Barrier Function and Microbiota. J Funct Biomater 2024, 15, 236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Zang, J.; Yu, Y.; Liu, Y.; Cao, H.; Guo, R.; Zhang, L.; Liu, M.; Zhang, Z.; Li, X.; et al. Lingguizhugan Oral Solution Alleviates MASLD by Regulating Bile Acids Metabolism and the Gut Microbiota through Activating FXR/TGR5 Signaling Pathways. Front Pharmacol 2024, 15, 1426049. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yue, H.; Jia, M.; Li, B.; Zong, A.; Du, F.; Xu, T. Medium Chain Triglycerides Alleviate Non-Alcoholic Fatty Liver Disease through Bile Acid-Mediated FXR Signaling Pathway: A Comparative Study with Common Vegetable Edible Oils. J Food Sci 2024, 89, 10171–10180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gaggini, M.; Carli, F.; Rosso, C.; Younes, R.; D’Aurizio, R.; Bugianesi, E.; Gastaldelli, A. Altered Metabolic Profile and Adipocyte Insulin Resistance Mark Severe Liver Fibrosis in Patients with Chronic Liver Disease. Int J Mol Sci 2019, 20, 6333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ding, Y.; Yanagi, K.; Yang, F.; Callaway, E.; Cheng, C.; Hensel, M.E.; Menon, R.; Alaniz, R.C.; Lee, K.; Jayaraman, A. Oral Supplementation of Gut Microbial Metabolite Indole-3-Acetate Alleviates Diet-Induced Steatosis and Inflammation in Mice. eLife 2024, 13, 87458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Min, B.H.; Devi, S.; Kwon, G.H.; Gupta, H.; Jeong, J.J.; Sharma, S.P.; Won, S.M.; Oh, K.K.; Yoon, S.J.; Park, H.J.; et al. Gut Microbiota-Derived Indole Compounds Attenuate Metabolic Dysfunction-Associated Steatotic Liver Disease by Improving Fat Metabolism and Inflammation. Gut Microbes 2024, 16, 2307568. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ouyang, C.; Liu, P.; Liu, Y.; Lan, J.; Liu, Q. Metabolites Mediate the Causal Associations between Gut Microbiota and NAFLD: A Mendelian Randomization Study. BMC Gastroenterol 2024, 24, 244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chashmniam, S.; Ghafourpour, M.; Farimani, A.R.; Gholami, A.; Ghoochani, B.F.N.M. Metabolomic Biomarkers in the Diagnosis of Non-Alcoholic Fatty Liver Disease. Hepat Mon 2019, 19, e92244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ji, M.; Jo, Y.; Choi, S.J.; Kim, S.M.; Kim, K.K.; Oh, B.C.; Ryu, D.; Paik, M.J.; Lee, D.H. Plasma Metabolomics and Machine Learning-Driven Novel Diagnostic Signature for Non-Alcoholic Steatohepatitis. Biomedicines 2022, 10, 1669. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aggarwal, H.; Pathak, P.; Kumar, Y.; Jagavelu, K.; Dikshit, M. Modulation of Insulin Resistance, Dyslipidemia and Serum Metabolome in iNOS Knockout Mice Following Treatment with Nitrite, Metformin, Pioglitazone, and a Combination of Ampicillin and Neomycin. Int J Mol Sci 2022, 23, 195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oh, K.K.; Gupta, H.; Min, B.H.; Ganesan, R.; Sharma, S.P.; Won, S.M.; Jeong, J.J.; Lee, S.B.; Cha, M.G.; Kwon, G.H.; et al. The Identification of Metabolites from Gut Microbiota in NAFLD via Network Pharmacology. Sci Rep 2023, 13, 724. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cirstea, M.S.; Yu, A.C.; Golz, E.; Sundvick, K.; Kliger, D.; Radisavljevic, N.; Foulger, L.H.; Mackenzie, M.; Huan, T.; Finlay, B.B.; et al. Microbiota Composition and Metabolism Are Associated With Gut Function in Parkinson’s Disease. Mov Disord 2020, 35, 1208–1217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nemet, I.; Saha, P.P.; Gupta, N.; Fischbach, M.A.; DiDonato, J.A.; Hazen, S.L. A Cardiovascular Disease-Linked Gut Microbial Metabolite Acts via Adrenergic Receptors. Cell 2020, 180, 862–877. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barton, W.; Cronin, O.; García-Pérez, I.; Wiston, R.; Holmes, E.; Woods, T.; Molloy, C.B.; Molloy, M.G.; Shanahan, F.; Cotter, P.D.; et al. The Effects of Sustained Fitness Improvement on the Gut Microbiome: A Longitudinal, Repeated Measures Case-study Approach. Transl Sports Med 2021, 4, 174–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).