1. Introduction

AI evaluation serves as a fundamental pillar in the validation and lifecycle management of artificial intelligence systems, ensuring their reliability, safety, and effectiveness across regulated and high-impact domains. Evaluation is a critical component of AI validation, providing objective evidence of system capabilities, fitness for intended use, and ongoing performance assurance, while offering confidence to stakeholders that ethical, compliance, and operational requirements are met [

1,

2]. The primary purpose of AI evaluation is to verify that the system consistently achieves its intended use with acceptable accuracy and reliability under normal operating conditions and reasonably foreseeable scenarios [

3,

4]. This requires systematic assessment of critical performance attributes, including accuracy, precision, robustness, and reliability, alongside the identification of biases, limitations, or failure modes that may compromise outputs or result in unintended harm [

4,

5].

The interaction between humans and AI systems raises fundamental questions concerning power, responsibility, and human agency within decision-making processes, especially in domains where errors may lead to serious or irreversible harm [

6,

7]). In regulated environments such as healthcare and clinical research, inadequate oversight or delayed detection of model limitations can directly compromise patient safety, data integrity, and regulatory compliance, underscoring the need for a cautious, structured, and risk-based approach to AI deployment [

8]. Responsibility for AI outcomes is consequently distributed across developers, data scientists, system owners, content providers, and institutional decision-makers, reinforcing the need for clear accountability mechanisms. Despite this distributed responsibility, human agency defined as the capacity for informed, accountable, and context-aware decision-making must remain central to AI-enabled processes [

9]. Trustworthy AI design requires explicit determination of the appropriate form and intensity of human oversight, calibrated to the system’s risk profile and context of use [

2,

10]. This is particularly critical where AI outputs influence clinical decisions, individual rights, or compliance with GxP obligations. Ethical AI implementation should therefore preserve human authority and accountability, positioning AI as a decision-support tool that augments rather than replacing human judgment [

6].

Building on the principles of Trustworthy AI, this paper advances a structured, risk-based approach for integrating Human-in-Command (HIC), Human-in-the-Loop (HITL), and Human-on-the-Loop (HOTL) oversight models into AI governance through the combined evaluation of metrics-derived risk [

6]. The proposed MetricsDriven Human Oversight Framework for AI Systems follows a step-wise methodology. First, metrics are assessed to establish foundational evidence of model performance and statistical validity within the defined context of use, confirming whether predefined functional and acceptance criteria are met. Second, results from metrics are synthesized and categorized into low, medium, or high metrics risk, reflecting residual uncertainty and potential performance-related failure modes. Third, this risk outcome informs the proportional allocation of human oversight HIC, HITL, or HOTL ensuring that human involvement is commensurate with both performance uncertainty and potential impact.

Human-in-Command (HIC) provides governance-level accountability, granting authority to suspend or override system operations. Human-in-the-Loop (HITL) enables real-time monitoring, allowing timely human intervention to prevent or mitigate harm. Human-on-the-Loop (HOTL) is suitable when continuous oversight is unnecessary, and monitoring with periodic review is sufficient. By linking performance evidence, contextual risk, and oversight intensity, the proposed framework translates ethical principles into auditable governance mechanisms, while advancing contemporary metrics-informed oversight research

2. The State of the Debate

Artificial intelligence has become a defining technological force in contemporary healthcare, life sciences, and other regulated domains, with rapid advances enabling automated analysis, prediction, and decision support. In clinical and GxP-relevant contexts, AI systems increasingly influence activities that directly affect patient safety, data integrity, product quality, and regulatory compliance [

3,

8]. As a result, scholarly and regulatory attention has shifted from whether AI can be deployed to how it should be evaluated, validated, and governed to ensure trustworthy and responsible use [

6]. While there is broad agreement that AI systems must demonstrate acceptable technical performance, significant debate remains regarding what constitutes sufficient evidence of safety, reliability, and ethical acceptability in real-world use [

11].

A central point of contention concerns the reliance on performance metrics such as accuracy, sensitivity, specificity as primary indicators of AI system suitability. Although these metrics provide foundational evidence of statistical validity and functional performance, critics argue that they are insufficient on their own to capture broader risks related to bias, robustness, explainability, transparency, and operational reliability [

11]. This limitation is particularly pronounced in clinical screening and decision-support applications, where strong aggregate performance may coexist with subgroup disparities, brittle behavior under data shift, or opaque decision logic. Consequently, there is growing recognition that AI evaluation must extend beyond primary metrics to include secondary, context-sensitive metrics that reflect ethical, human-centered, and operational dimensions of risk [

4,

12]. However, the literature remains fragmented on how such metrics should be measured, interpreted, and systematically incorporated into validation and quality risk management processes.

Closely linked to the debate on metrics is the question of risk-based human oversight. There is general consensus that some form of human involvement is essential to preserve accountability, support safe decision-making, and prevent harm, particularly in high-impact or regulated environments [

6]. Regulatory frameworks and standards increasingly emphasize proportionality, suggesting that the level of human oversight should correspond to the level of risk posed by the AI system [

2,

10].

While some approaches prioritize contextual factors such as clinical use case, severity of potential harm, and regulatory impact, others emphasize empirical performance evidence as the primary driver of trust [

9]. In the absence of a unified framework, organizations often struggle to determine whether strong metrics can offset contextual risk, how to interpret mixed or borderline results, and when human intervention should escalate from monitoring to active control or command authority [

4,

7]. In response to these challenges, this paper contributes to the ongoing debate by proposing a structured, metrics-informed risk assessment framework that integrates AI evaluation, validation, and human oversight into a single decision-making process. Rather than treating metrics, risk, and oversight as separate considerations, the framework distinguishes between metrics, categorizes their results into metrics risk levels, and informs the proportional application of Human-in-Command (HIC), Human-in-the-Loop (HITL), or Human-on-the-Loop (HOTL) oversight models. By aligning this methodology with established risk management principles from ISO 31000, ISO/IEC 23894, and ICH Q9, the paper advances the debate from conceptual endorsement of “human oversight” toward a practical, auditable, and context-sensitive approach suitable for high-stakes and regulated AI deployments [

9].

3. AI Evaluation Metrics

Metrics constitute the core quantitative measures used to evaluate whether an artificial intelligence (AI) system fulfills its intended functional objectives. These metrics directly assess task-level performance and model correctness and are therefore central to determining baseline system reliability. Among metrics, Task Success Rate (TSR) serves as an overarching indicator of system effectiveness, measuring the proportion of end-to-end tasks successfully completed under defined operating conditions. In addition to TSR, commonly used metrics include accuracy, precision, recall (sensitivity), F1-score, and area under the receiver operating characteristic curve (AUC–ROC) for classification tasks, as well as mean squared error (MSE) or related loss functions for regression tasks [

12,

13].

Metrics are quantitatively derived from a confusion matrix, which summarizes model predictions against a clinically established ground truth (

Table 1).

4. Risk Assessment and Oversight

Risk assessment is a structured approach to identifying, analyzing, and evaluating risks that may impact system quality, patient safety, data integrity, or regulatory compliance. It is required to support risk-based decision-making by categorizing risks and enabling the selection and implementation of appropriate controls that are commensurate with the level of risk [

2,

3,

8]. This approach introduces a metrics-based risk assessment in which metrics are systematically evaluated to establish an initial risk category (low, medium, or high). The resulting metrics risk is subsequently integrated with the inherent risk of the AI system to determine an overall risk classification. This combined risk assessment (

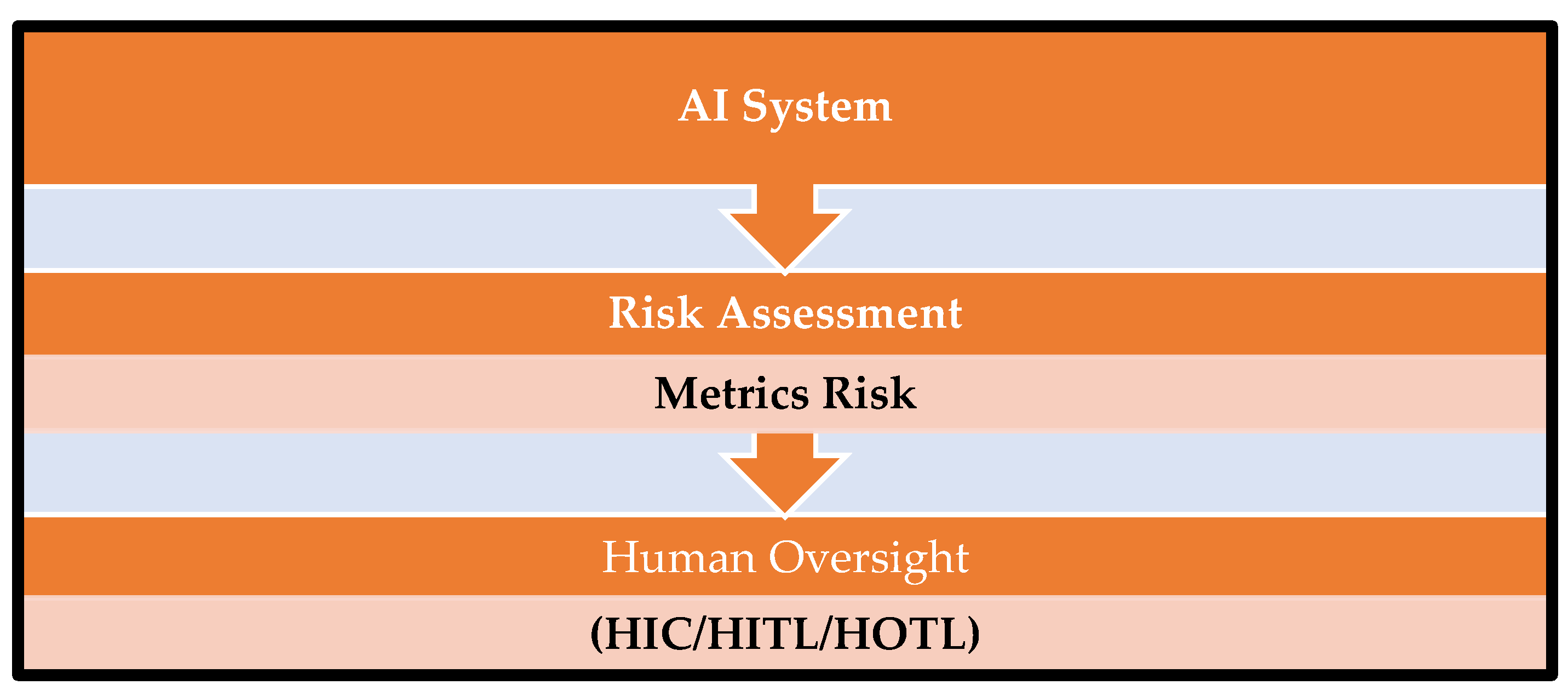

Figure 1) informs the selection and application of proportionate human oversight controls.

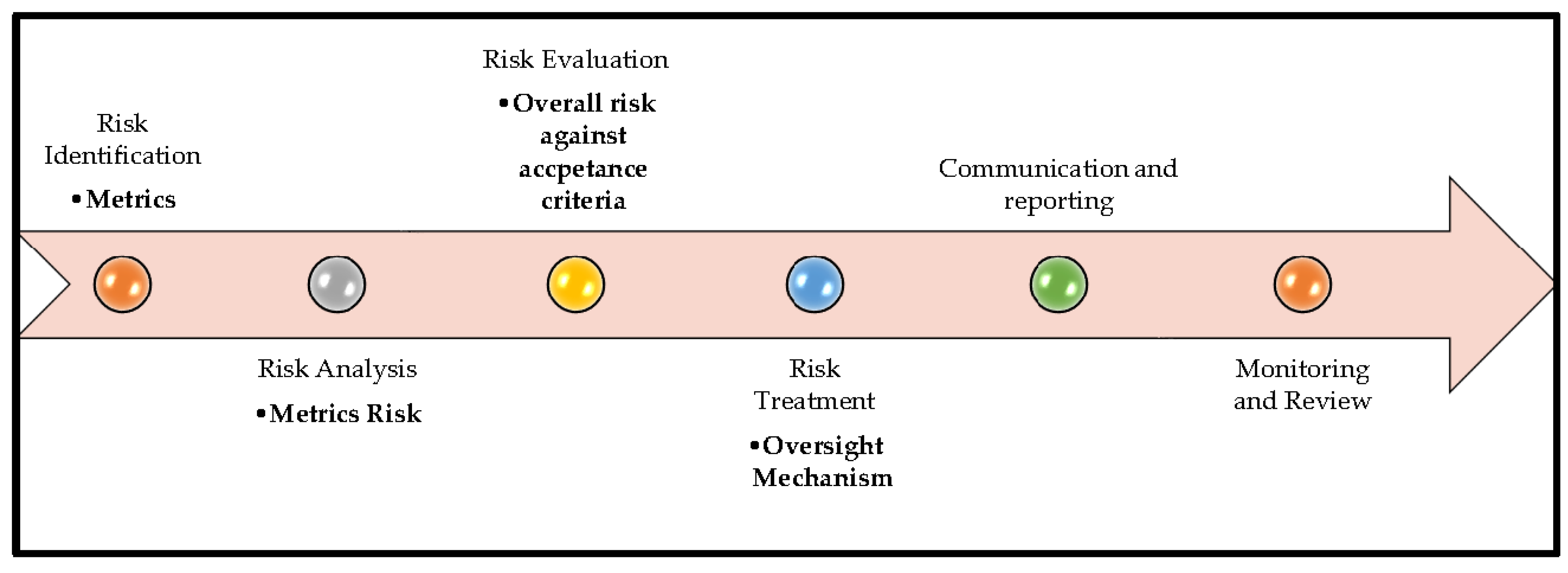

Consistent with the risk management lifecycle defined in ISO 31000 and its AI-specific extension in ISO/IEC 23894, the proposed framework operationalizes (

Figure 2) risk management for AI systems through a structured, metrics-driven approach [

2,

3].

4.1. Risk Identification

Metrics such as accuracy, precision, recall (sensitivity), F1 score, AUC–ROC, and task success rate (TSR) quantify the technical performance of an AI system. Authors’ proposal is to map these metrics to a risk-based framework, where lower performance indicates a higher probability of failure, increased uncertainty, or potential adverse outcomes. This approach allows organizations to prioritize mitigation, validation, and monitoring efforts based on risk-informed decisions.

4.2. Risk Analysis

Risk Analysis is performed by mapping each metrics to Low, Medium, High risk levels using performance thresholds (

Table 2).

Low Risk: AI performance meets or exceeds the expected performance thresholds. System behavior is highly reliable; minimal probability of error or adverse outcome.

Medium Risk: AI performance is adequate but not optimal. Moderate probability of errors or unintended outcomes; additional validation, monitoring, or mitigation may be required.

High Risk: AI performance is suboptimal; high probability of errors or failure; immediate attention, re-training, or operational restrictions may be needed.

4.3. Risk Evaluation

Risk evaluation involves comparing analyzed risks against predefined acceptance criteria to prioritize AI systems into low, medium, or high-risk categories [

2,

3]. This prioritization informs decisions regarding deployment readiness, validation depth, and the necessity for additional controls. Where risks need to be reduced to acceptable thresholds for safer deployment and operation, risk treatment and control measures are selected and implemented with a particular focus on proportionate human oversight mechanisms, including Human-in-Command (HIC), Human-in-the-Loop (HITL), or Human-on-the-Loop (HOTL), selected according to the assessed risk level [

9].

Given the presence of multiple evaluation metrics, metrics risk is determined using one of the approaches,

Worst-case approach, use the metric result that shows the highest risk.

Key-metric approach, focus on metrics that were identified in advance as the most important or critical.

Average approach, calculate the overall risk based on the average of all metric results.

Other documented approaches, use any alternative method, as long as it is clearly described and justified.

In this illustrative example, a worst-case approach is adopted. For example, if metrics (e.g., F1 score, precision, recall) range from low to medium risk levels, the higher risk level (medium) is selected as the representative metrics risk.

4.4. Risk Treatment

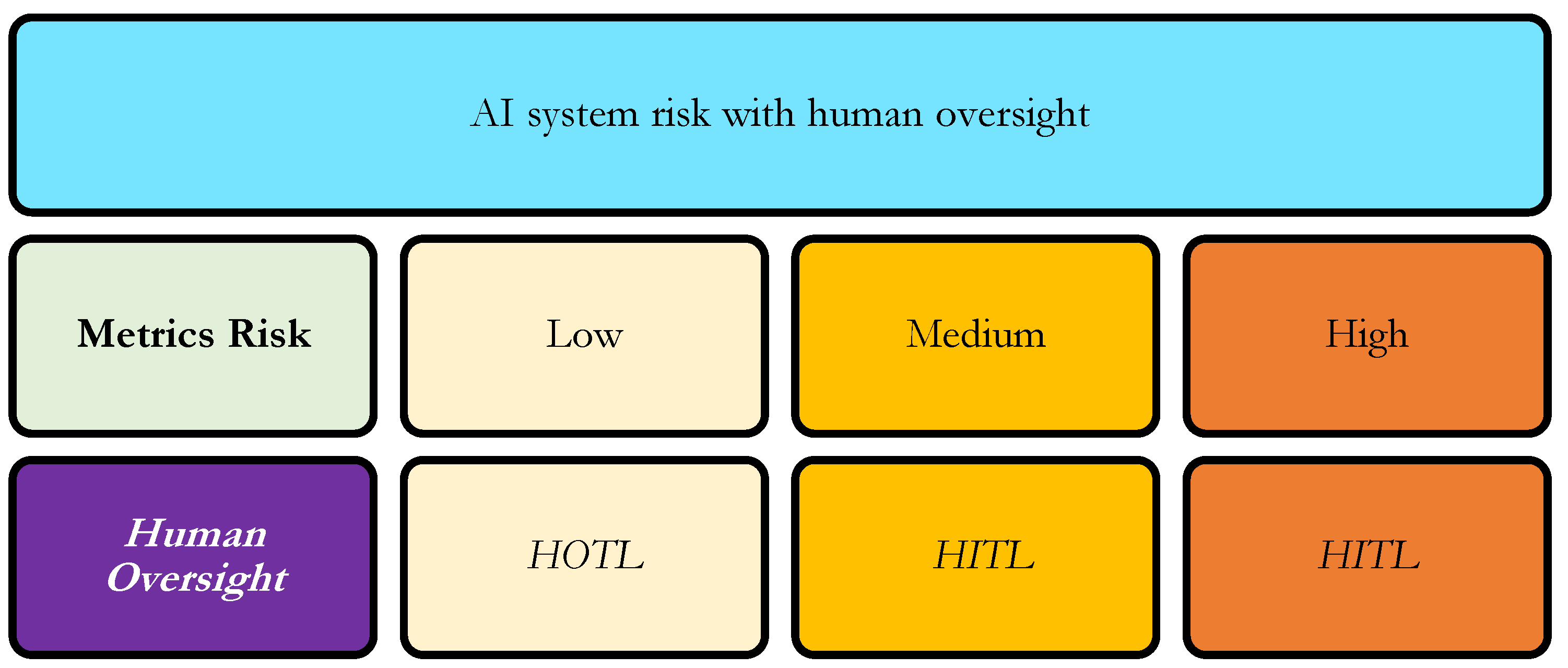

Once the metrics-risk is determined, the level of human oversight can be proportionally assigned according to the system’s risk level [

2,

3]. High-risk AI systems, where critical metrics are deficient or the AI System has substantial impact on patient safety, product quality, or regulatory compliance, require a Human-in-Command (HIC) model. In this model, a qualified human retains ultimate authority and responsibility over decisions, ensuring that AI outputs are carefully interpreted before action. Medium-risk systems are best managed under a Human-in-the-Loop (HITL) framework, in which human operators review and validate AI outputs during operation, allowing for corrective intervention when necessary. Low-risk systems, with minimal potential impact or robust technical performance, can be monitored under a Human-on-the-Loop (HOTL) model, where AI operates autonomously while human supervision occurs primarily through auditing, alerts, or periodic review (

Figure 3). By linking risk classification to oversight intensity, this framework ensures that human intervention is applied proportionally to both technical and operational risk, supporting safe, compliant, and responsible deployment of AI in clinical and regulated environments [

9].

4.4. Communication & Reporting

Communication and reporting constitute a critical activity throughout the risk management process. Risk assumptions, assessment methodologies, metric results, risk categorizations, and implemented control measures are formally documented and communicated to relevant stakeholders, including developers, quality and compliance teams, clinical users, and regulatory authorities. This documentation supports traceability, auditability, and regulatory transparency, enabling informed decision-making and accountability across the AI lifecycle [

2,

3,

8].

4.5. Monitoring & Review

Finally, monitoring and review ensure that AI risk management remains effective over time. Post-deployment monitoring activities track residual risks, assess the ongoing effectiveness of mitigation controls, and detect emerging risks arising from model updates, data drift, changes in clinical practice, or evolving regulatory expectations. Periodic review of metrics enables timely reclassification of risk levels and adjustment of oversight mechanisms, thereby supporting continuous improvement and sustained compliance with ISO and ICH quality risk management principles [

2,

3,

8].

5. Illustrative Risk Assessments Informing Human Oversight

Illustrative Example: Diabetic Retinopathy Screening Example

The scenario presented below are informed by the existing literature but are not directly derived from or intended to represent specific published case studies.

5.1. Risk Identification

Scenario 1: Human in the Loop

Metrics Risk

The

Table 3 summarizes typical observed values for key metrics from AI-based diabetic retinopathy screening models, illustrating how performance is quantified and interpreted in risk terms [

12,

13,

14,

15,

16].

Metrics risk is considered as Medium in this scenario.

5.2. Risk Analysis

The risk is evaluated as medium based on the evaluation of metrics.

Table 4.

Risk Analysis and corresponding human oversight (HITL).

Table 4.

Risk Analysis and corresponding human oversight (HITL).

| Type |

Result |

| Metrics Risk |

Medium |

| Human Oversight |

HITL |

5.3. Risk Evaluation

This evaluation reflects a medium-risk level. The AI system has significant influence on regulated decisions and patient outcomes; the likelihood and severity of adverse consequences are mitigated through appropriate human oversight.

5.4. Risk Treatment

Given the medium metrics risk, the recommended risk treatment is the implementation of a Human-in-the-Loop (HITL) oversight model. In this approach, human experts actively review AI outputs, validate flagged cases, and retain authority over critical decisions. HITL serves as a control mechanism to detect potential errors, reduce false negatives and false positives, and ensure patient safety. It also aligns with regulatory expectations for GxP compliance and supports responsible AI deployment in high-stakes clinical environments [

2,

3,

8].

5.5. Monitoring and Review

Continuous monitoring metrics is essential to ensure that the AI system maintains its performance over time and under varying conditions. Key monitoring activities include tracking sensitivity, specificity, and F1 score across new patient data, auditing bias and fairness metrics, and reviewing explainability outputs for consistency with clinical reasoning. Periodic review of observed trends, error rates, and system drift ensures timely identification of emerging risks, allowing corrective actions or model retraining as needed [

2,

3].

5.6. Communication and Reporting

Transparent communication and reporting are critical for stakeholders, including clinicians, quality assurance teams, and regulators. Regular reports should summarize the AI system’s performance, highlight identified risks, document mitigation actions, and provide justification for the chosen human oversight model. Clear documentation supports regulatory submissions, facilitates audit readiness, and reinforces stakeholder confidence in the AI system’s reliability and ethical deployment [

2,

3].

6. Conclusion

AI evaluation and risk assessment are essential for ensuring safe, reliable, and ethically responsible deployment, particularly in high-impact domains such as healthcare. By systematically assessing metrics, organizations can quantify metrics risk and map it against the appropriate human oversight model—Human-in-the-Loop (HITL), Human-on-the-Loop (HOTL), or Human-in-Command (HIC).

Risk evaluation involves identifying metrics risks, while risk treatment implements controls and oversight strategies tailored to the risk level. Monitoring and review ensure that residual risks are managed, system performance remains within acceptable bounds, and AI outputs continue to meet clinical or operational standards. Communication and reporting provide transparency to stakeholders, regulators, and auditors, reinforcing accountability and trust.

The framework is designed to be flexible and adaptable and supports multiple evaluation pathways to inform human oversight decisions. It prioritizes the most significant or worst-case metrics when evaluating risk, accommodates variations based on the AI system or context of use, and allows human oversight to be applied based on either metrics risk or system risk independently.

Overall, this approach provides a robust, risk-informed methodology for AI validation, deployment, and governance, balancing technical performance with ethical, regulatory, and operational considerations.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| AI |

Artificial Intelligence |

| AUC - ROC |

Area Under the Receiver Operating Characteristic Curve |

| FN |

False Negative |

| FP |

False Positive |

| HIC |

Human-in-Command |

| HITL |

Human-in-the-Loop |

| HOTL |

Human-on-the-Loop |

| ISO |

International Standards Organization |

| MSE |

Mean Squared Error |

| TN |

True Negative |

| TP |

True Positive |

| TSR |

Task Success Rate |

References

- US FDA. Considerations for the use of artificial intelligence to support regulatory decision-making for drug and biological products. 2025. Available online: https://www.fda.gov/media/168399/download.

- ISO. ISO 31000. 2018. Available online: https://www.iso.org/standard/65694.html#lifecycle.

- ISO. 2023. Available online: https://www.iso.org/standard/77304.html.

- Raji, I. D.; Smart, A.; White, R. N.; Mitchell, M.; Gebru, T.; Hutchinson, B.; Barnes, P. Closing the AI accountability gap: Defining an end-to-end framework for internal algorithmic auditing. In Proceedings of the 2020 conference on fairness, accountability, and transparency, 2020, January; pp. 33–44. [Google Scholar]

- Mitchell, M.; Wu, S.; Zaldivar, A.; Barnes, P.; Vasserman, L.; Hutchinson, B.; Gebru, T. Model cards for model reporting. In Proceedings of the conference on fairness, accountability, and transparency, 2019, January; pp. 220–229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- European Commission, S. Ethics guidelines for trustworthy AI. Publications Office. 2019. Available online: https://digital-strategy.ec.europa.eu/en/library/ethics-guidelines-trustworthy-ai.

- Green, B. The flaws of policies requiring human oversight of government algorithms. Computer Law & Security Review 2022, 45, 105681. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- International Council for Harmonisation of Technical Requirements for Pharmaceuticals for Human Use ICH Q9(R1): Quality risk management. 2023. Available online: https://www.ich.org.

- Kandikatla, L.; Radeljic, B. AI and Human Oversight: A Risk-Based Framework for Alignment. arXiv 2025, arXiv:2510.09090. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- European Union. Regulation (EU) 2024/1689 laying down harmonised rules on artificial intelligence (Artificial Intelligence Act). Official Journal of the European Union 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Mikalef, P.; Conboy, K.; Lundström, J. E.; Popovič, A. Thinking responsibly about responsible AI and ‘the dark side’of AI. European Journal of Information Systems 2022, 31(3), 257–268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kocak, B.; Klontzas, M. E.; Stanzione, A.; Meddeb, A.; Demircioğlu, A.; Bluethgen, C.; Cuocolo, R. Evaluation metrics in medical imaging AI: fundamentals, pitfalls, misapplications, and recommendations. European Journal of Radiology Artificial Intelligence 2025, 100030. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McDermott, M.; Zhang, H.; Hansen, L.; Angelotti, G.; Gallifant, J. A closer look at auroc and auprc under class imbalance. Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems 2024, 37, 44102–44163. [Google Scholar]

- Uy, H.; Fielding, C.; Hohlfeld, A.; Ochodo, E.; Opare, A.; Mukonda, E.; Engel, M. E. Diagnostic test accuracy of artificial intelligence in screening for referable diabetic retinopathy in real-world settings: A systematic review and meta-analysis. PLOS Global Public Health 2023, 3(9), e0002160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Developers, Google. Classification: Accuracy, recall, precision, and related metrics. 2025. Available online: https://developers.google.com/machine-learning/crash-course/classification/accuracy-precision-recall.

- Ripatti, A. R. Screening Diabetic Retinopathy and Age-Related Macular Degeneration with Artificial Intelligence: New Innovations for Eye Care. 2025. [Google Scholar]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).