Submitted:

30 January 2026

Posted:

03 February 2026

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Results

2.1. Quantitative Analysis of the Key Components in ABSs

2.2. Rats Plasma Pharmacokinetics of ABS with a Single Oral Administration

2.3. Sources and Attribution of the Principal Constituents in ABS

2.3.1. Epimedii Folium: IC and Its Metabolites

2.3.2. PMRP: TSG, EM, and EMG

2.3.3. Glycyrrhizae Radix et Rhizome: GTA and LI

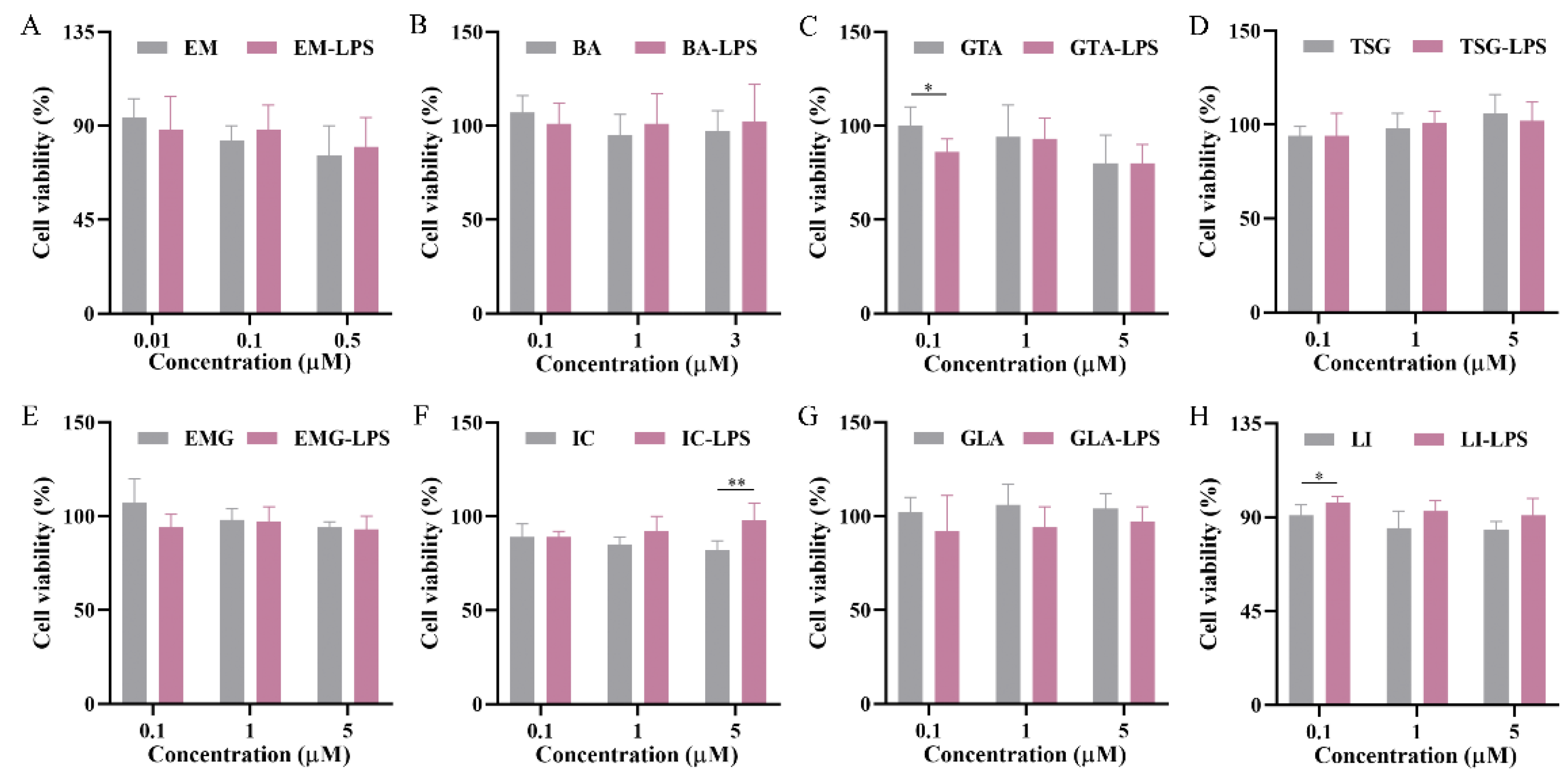

2.4. Optimization of Concentration Range for the Target Compounds

2.5. Hepatotoxic Effects of the Target Compounds in HepG2 Cells

2.6. Screening the Idiosyncratic Hepatotoxic Components of ABS

3. Discussion

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Experimental Reagents

4.2. Animals

4.3. Pharmacokinetic Study

4.4. Evaluation of Plasma Exposure Level

4.5. Plasma Samples UPLC–MS/MS Assay Parameters

4.6. Cell Culture

4.7. Evaluation of Hepatotoxicity In Vitro

4.8. Statistical Analysis

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Institutional Review Board Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

List of Abbreviations

| ABS | Anshenbunao Syrup |

| BA | baohuoside I |

| DHC | direct hepatotoxic component |

| PMRP | Polygoni Multiflori Radix Praeparata |

| DILI | drug induced liver injury |

| EM | emodin |

| LI | liquiritin |

| TSG | 2,3,5,4′–Tetrahydroxystilbene–2–O–β–D–glucoside |

| GTA | 18β–glycyrrhetinic acid |

| PMR | Polygoni Multiflori Radix |

| TCM | traditional Chinese medicine |

| EMG | emodin–8–O–β–D–glucoside |

| HLA | human leukocyte antigen |

| EP–B | epimedin B |

| EP–C | epimedin C |

| 2'–O–RI Ⅱ | 2'–O–rhamnosylicariside Ⅱ |

| SA–B | sagittatoside B |

| HESI | heated electrospray ionization interface |

| OD | optical density |

| Cmax | plasma peak concentration |

| Tmax | corresponding peak time |

| AUC0–t | area under the plasma concentration–time curves |

| t1/2 | terminal elimination half-life time |

| IHC | idiosyncratic hepatotoxic component |

References

- Sun, Y.; Xia, Q.; Du, L.; Gan, Y.; Ren, X.; Liu, G.; Wang, Y.; Yan, S.; Li, S.; Zhang, X. Neuroprotective effects of Anshen Bunao Syrup on cognitive dysfunction in Alzheimer's disease rat models. Biomed. Pharmacother. 2024, 176, 116754. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, X.; Liu, J.; Long, G.; Xia, X.; Liu, M. 2, 3, 5, 4′-Tetrahydroxystilbene-2-O-β-D-glucoside, a major bioactive component from Polygoni multiflori Radix (Heshouwu) suppresses DSS induced acute colitis in BALb/c mice by modulating gut microbiota. Biomed. Pharmacother. 2021, 137, 111420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Q.; Hou, Z.; Liu, Z.; Zheng, Z.; Xing, J.; Sun, R.; Liu, S. The difference of composition between Polygoni Multiflori Radix and Rhei Radix et Rhizoma revealed their primary hepatotoxicity components. J. Ethnopharmacol. 2025, 351, 120106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gong, L.; Du, H.; Guo, X.; Li, J.; Zhu, X.; Shen, X.; Huang, Z.; Wu, K.; Zhang, G.; Sun, R. Shouhui Tongbian Capsule in treatment of constipation: Treatment and mechanism development. Chin. Herb. Med. 2024, 16, 239–247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Zhao, G.; Ju, C.; Dong, L.; Liu, Y.; Ding, Z.; Li, W.; Peng, Y.; Zheng, J. Reduction of emodin-8-O-ß-D-glucoside content participates in processing-based detoxification of polygoni multiflori radix. Phytomedicine 2023, 114, 154750. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, W.; Wang, Y.; Qiu, C.; Li, J.; Bao, J.; Yang, J.; Jin, H. Processing-induced reduction in dianthrones content and toxicity of Polygonum multiflorum: Insights from ultra-high performance liquid chromatography triple quadrupole mass spectrometry analysis and toxicological assessment. Anim. Models Exp. Med. 2025, 8, 685–695. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shi, Z.; Li, X.; Liu, Y.; Li, P.; Niu, M.; Bai, Z.; Zhang, G.; Lu, Y.; Wang, J. Spectrum-toxicity correlation study revealed the influence of the nine-time steaming and sun drying method on hepatotoxic components of Polygoni Multiflori Radix. World J. Tradit. Chin. Med. 2021, 7, 227–233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, C.; Jiang, Y.; Bao, Q.; Wang, L.; Tang, L.; Liu, Y.; Yang, L. Study on the differential hepatotoxicity of raw polygonum multiflorum and polygonum multiflorum praeparata and its mechanism. BMC Complementary Med. Ther. 2024, 24, 161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, S.; Kong, X.; Chen, N.; Hu, P.; Boucetta, H.; Hu, Z.; Xu, X.; Zhang, P.; Zhan, X.; Chang, M. Hepatotoxic metabolites in Polygoni Multiflori Radix—Comparative toxicology in mice. Front. Pharmacol. 2022, 13, 1007284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, M.; Yu, L.; Zhao, H.; Zhou, X.; Yang, Q.; Song, F.; Yan, L.; Zhai, M.; Li, B.; Zhang, B. 2, 3, 5, 4′-Tetrahydroxystilbene-2-O-β-D-glucoside protects murine hearts against ischemia/reperfusion injury by activating Notch1/Hes1 signaling and attenuating endoplasmic reticulum stress. Acta Pharmacol. Sin. 2017, 38, 317–330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, Z.; Xu, J.; Long, M.; Tu, Z.; Yang, G.; He, G. 2, 3, 5, 4′-tetrahydroxystilbene-2-O-β-d-glucoside (THSG) induces melanogenesis in B16 cells by MAP kinase activation and tyrosinase upregulation. Life Sci. 2009, 85, 345–350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lin, H.; Yang, Y.; Chen, Y.; Huang, T.; Crawford, D.; Chuang, H.; Chin, Y.; Chu, H.; Li, Z.; Shih, Y. 2, 3, 5, 4′-Tetrahydroxystilbene-2-O-β-D-Glucoside improves female ovarian aging. Front. Cell Dev. Biol. 2022, 10, 862045. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zheng, Y.; Li, J.; Wu, J.; Yu, Y.; Yao, W.; Zhou, M.; Tian, J.; Zhang, J.; Cui, L.; Zeng, X. Tetrahydroxystilbene glucoside isolated from Polygonum multiflorum Thunb. demonstrates osteoblast differentiation promoting activity. Exp. Ther. Med. 2017, 14, 2845–2852. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shen, Z.; Zhao, L.; Yoo, S.; Lin, Z.; Zhang, Y.; Yang, W.; Piao, J. Emodin induces ferroptosis in colorectal cancer through NCOA4-mediated ferritinophagy and NF-κb pathway inactivation. Apoptosis 2024, 29, 1810–1823. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, Y.; Yang, L.; Lai, Y. Recent findings regarding the synergistic effects of emodin and its analogs with other bioactive compounds: Insights into new mechanisms. Biomed. Pharmacother. 2023, 162, 114585. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dong, X.; Fu, J.; Yin, X.; Cao, S.; Li, X.; Lin, L.; Hu, Y.; Ni, J. Emodin: a review of its pharmacology, toxicity and pharmacokinetics. Phytother. Res. 2016, 30, 1207–1218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, D.; Duan, J.; Chen, X.; Liu, K.; Guo, Y.; Shi, R.; Li, S.; Liu, M.; Zhao, L.; Li, B. Pharmacokinetic characteristics of emodin in polygoni Multiflori Radix Praeparata. J. Ethnopharmacol. 2023, 303, 115945. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chalasani, N.; Li, Y.; Dellinger, A.; Navarro, V.; Bonkovsky, H.; Fontana, R.J.; Gu, J.; Barnhart, H.; Phillips, E.; Lammert, C. Clinical features, outcomes, and HLA risk factors associated with nitrofurantoin-induced liver injury. J. Hepatol. 2023, 78, 293–300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jaeschke, H.; Ramachandran, A. Acetaminophen hepatotoxicity: paradigm for understanding mechanisms of drug-induced liver injury. Annu. Rev. Pathol.:Mech. Dis. 2024, 19, 453–478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, Y.; Zhou, K.; Ma, M.; Liu, H.; Jin, M.; Yin, C.; Wang, S.; Zhang, J. Thiol “click” chromene mediated cascade reaction forming coumarin for in-situ imaging of thiol flux in drug-induced liver injury. Chem. Eng. J. 2023, 452, 139020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Segovia Zafra, A.; Di Zeo Sánchez, D.e.; López Gómez, C.; Pérez Valdés, Z.; Garcia Fuentes, E.; Andrade, R.j.; Lucena, M.; Villanueva Paz, M. Preclinical models of idiosyncratic drug-induced liver injury (iDILI): Moving towards prediction. Acta Pharm. Sin. B 2021, 11, 3685–3726. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fontana, R.j.; Liou, I.; Reuben, A.; Suzuki, A.; Fiel, M.i.; Lee, W.; Navarro, V. AASLD practice guidance on drug, herbal, and dietary supplement–induced liver injury. Hepatol. 2023, 77, 1036–1065. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Almagharbeh, W. Mechanisms of drug-induced liver injury: Exploring pathways and risk factors for liver toxicity. Trends Life Sci. Biotechnol. 2024, 1, 13–26. [Google Scholar]

- Li, G.; Yu, G. Drug-induced liver injury with ritonavir-boosted nirmatrelvir: evidence from coronavirus disease 2019 emergency use authorization adverse event reporting system. Gastroenterology 2023, 165, 305–306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fontana, R.; Bjornsson, E.; Reddy, R.; Andrade, R. The evolving profile of idiosyncratic drug-induced liver injury. Clin. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2023, 21, 2088–2099. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yokoi, T.; Oda, S. Models of idiosyncratic drug-induced liver injury. Annu. Rev. Pharmacol. Toxicol. 2021, 61, 247–268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pinazo Bandera, J.; Niu, H.; Alvarez Alvarez, I.; Medina Cáliz, I.; Del Campo Herrera, E.; Ortega Alonso, A.; Robles Díaz, M.; Hernandez, N.; Parana, R.; Nunes, V. Rechallenge in idiosyncratic drug-induced liver injury: an analysis of cases in two large prospective registries according to existing definitions. Pharmacol. Res. 2024, 203, 107183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tu, C.; Gao, Y.; Bai, Z.; Xiao, X.; Wang, J. Discovery, evaluation, prevention, and control of liver injury risk by Polygoni Multiflori Radix. Acupunct. Herb. Med. 2024, 4, 271–281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiao, X.; Wang, J.; Song, H.; Ouyang, D.; Zou, Z.; Wang, R.; He, T.; Jing, J.; Guo, Y.; Bai, Z. Guidelines for safe use of Polygoni Multiflori Radix. Acupunct. Herb. Med. 2024, 4, 151–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, Y.; Men, X.; Wu, C.; Wei, X.; Chen, M.; Wang, J. Speciation of selenium-containing small molecules in urine and cell lysate by CE-ICPMS with in-capillary enrichment. Talanta 2025, 281, 126929. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, L.; Chen, F.; Liu, T.; Feng, F.; Guo, W.; Zhang, Y.; Feng, X.; Lin, J.; Zhang, F. Lipidomics profiling of HepG2 cells and interference by mycotoxins based on UPLC-TOF-IMS. Anal. Chem. 2022, 94, 6719–6727. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, X.; Luo, H.; Kasai, N.; Nakajima, H.; Kato, S.; Uchiyama, K.; Mao, S. An Inclined Push–Pull Probe for In Situ Cell Staining and Calcium Channel Activation. Anal. Chem. 2025, 97, 15376–15383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ma, N.; Pan, B.; Yang, S.; Lai, H.; Ning, J.; Li, Y.; Liu, J.; Huang, J.; Ma, Y.; Hou, L. Comparative efficacy and safety of Chinese patent medicines for primary insomnia: A systematic review and network meta-analysis of 109 randomized trials. J. Ethnopharmacol. 2025, 340, 119254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, W.; Cheng, R.; Boucetta, H.; Xu, L.; Pan, J.; Song, M.; Lu, Y.; Hang, T. Differences in Multicomponent Pharmacokinetics, Tissue Distribution, and Excretion of Tripterygium Glycosides Tablets in Normal and Adriamycin–Induced Nephrotic Syndrome Rat Models and Correlations With Efficacy and Hepatotoxicity. Front. Pharmacol. 2022, 13, 910923. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, S.; Yu, J.; Zhan, J.; Yang, L.; Guo, L.; Xu, Y. Pharmacokinetics, tissue distribution, and metabolism study of icariin in rat. BioMed Res. Int. 2017, 2017, 4684962. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jiang, L.; Zhao, D.; Fan, Y.; Yu, Q.; Lai, Y.; Li, P.; Li, H. Transcriptome analysis to assess the cholestatic hepatotoxicity induced by Polygoni Multiflori Radix: Up-regulation of key enzymes of cholesterol and bile acid biosynthesis. J. Proteomics 2018, 177, 40–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, A.; Lei, S.; Zhu, J.; Lu, J.; Paine, M.F.; Xie, W.; Ma, X. Chemical basis of pregnane X receptor activators in the herbal supplement Gancao (licorice). Liver Res. 2022, 6, 251–257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, D.; Jia, P.; Zhao, S.; Zhao, Y.; Liu, H.; Wei, F.; Ma, S. Identification and Differentiation of Polygonum multiflorum Radix and Polygoni multiflori Radix Preaparata through the Quantitative Analysis of Multicomponents by the Single-Marker Method. J. Anal. Methods Chem. 2019, 2019, 7430717. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zuo, J.; Meng, T.; Wang, Y.; Tang, W. A review of the antiviral activities of glycyrrhizic acid, glycyrrhetinic acid and glycyrrhetinic acid monoglucuronide. Pharmaceuticals 2023, 16, 641. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, H.; Kim, M.; Han, J. Icariin metabolism by human intestinal microflora. Molecules 2016, 21, 1158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stecanella, L.; Bitencourt, A.; Vaz, G.; Quarta, E.; Silva Junior, J.; Rossi, A. Glycyrrhizic acid and its hydrolyzed metabolite 18β-glycyrrhetinic acid as specific ligands for targeting nanosystems in the treatment of liver cancer. Pharmaceutics 2021, 13, 1792. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, W.; Zhao, J.; Li, W.; Zheng, Y.; Zhu, J.; Liu, J.; Liu, R.; Wang, Z.; Wang, X.; Hai, C. 2, 3, 5, 4′-Tetrahydroxystilbene-2-O-β-d-glucoside alleviated the acute hepatotoxicity and DNA damage in diethylnitrosamine-contaminated mice. Life Sci. 2020, 243, 117274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, J.; Choi, H.; Chung, J. Icariin supplementation suppresses the markers of ferroptosis and attenuates the progression of nonalcoholic steatohepatitis in mice fed a methionine choline-deficient diet. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023, 24, 12510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yan, M.; Guo, L.; Ma, J.; Yang, Y.; Tang, T.; Zhang, B.; Zhou, W.; Zou, W.; Hou, Z.; Gu, H. Liquiritin alleviates alpha-naphthylisothiocyanate-induced intrahepatic cholestasis through the Sirt1/FXR/Nrf2 pathway. J. Appl. Toxicol. 2023, 43, 350–359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tu, C.; He, Q.; Li, C.; Niu, M.; Han, Z.; Ge, F.; Zhou, Y.; Zhang, L.; Wang, X.; Zhu, J. Susceptibility-related factor and biomarkers of dietary supplement polygonum multiflorum-induced liver injury in rats. Front. Pharmacol. 2019, 10, 335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Components | Concentrations (μg/mL) |

| IC | 234.5±0.2 |

| TSG | 232.0±3.7 |

| EP-C | 28.8±0.1 |

| EP-B | 34.7±0.1 |

| GLA | 11.2±0.1 |

| LI | 8.78±0.07 |

| EMG | 4.81±0.08 |

| EM | 3.00±0.02 |

| Ingredients | Cmax | Tmax | AUC0-t | t1/2 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| (ng/mL) | (h) | (h*ng/mL) | (h) | |

| IC | 1.08±0.72 | 0.31±0.11 | 0.90±0.47 | 1.35±0.24 |

| BA | 0.74±0.29 | 0.82±0.38 | 0.99±0.28 | 7.58±1.96 |

| TSG | 0.88±0.27 | 0.10±0.03 | 1.06±0.20 | 2.46±0.40 |

| GTA | 3.27±0.17 | 11.0±0.58 | 77.5±1.43 | 8.70±0.38 |

| LI | 1.65±0.22 | 0.20±0.03 | 2.52±0.44 | 1.26±0.09 |

| EMG | 0.70±0.25 | 0.31±0.14 | 0.78±0.13 | 4.00±1.35 |

| EM | 0.82±0.25 | 0.44±0.16 | 1.92±0.36 | 4.63±1.53 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).