Introduction

In the classical approach, correspondence with organs and bodily systems is organized through traditional maps widely disseminated in educational literature, as observed in the work of Marquardt (2000) [

1], where manual stimulation of specific plantar reflex zones is proposed as a means of inducing distant functional responses. This model, grounded in practical experience and an empirically based reflexological cartography, explains therapeutic effects primarily through the precise localization of reflex zones and the application of manual pressure, without explicitly addressing the neurophysiological mechanisms involved in stimulus generation and processing.

In contrast, contemporary proposals, such as that of Dávila (2025) [

3], reformulate this framework by integrating a cartography supported by clinical experience and neurophysiological criteria, conceptualizing reflexology as a complementary therapy whose effects are grounded in the functional stimulation of nerve receptors and in the activation of mechanisms mediated by somatosensory afferent pathways and central integrative processes. In this regard, exploratory studies employing functional magnetic resonance imaging techniques have demonstrated brain activations associated with the stimulation of specific reflex zones, providing evidence of central correlates in distinct cortical territories and reinforcing the need to interpret reflexological cartography within a neurophysiological framework, without implying comprehensive validation of traditional maps [

26].

This conceptual evolution highlights the need to critically review the traditional explanatory foundations of reflexology and to situate it within a physiological framework consistent with current knowledge in neuroscience.

Within this context, a significant portion of the literature related to reflexology education and dissemination maintains that the foot contains approximately 7,000 nerve endings, a figure used as an explanatory argument for the therapeutic effects of plantar stimulation and associated with an allegedly high density of innervation, without specifying its anatomical or neurophysiological source [

2,

23,

24,

25]. Other educational texts describe the foot more generally as a richly innervated and highly sensitive region, without quantifying the number of nerve endings present [

21,

22]. The coexistence of imprecise formulations and unverified numerical claims reveals a persistent conceptual ambiguity within reflexology training materials.

Despite its widespread dissemination, there is no verifiable anatomical or neurophysiological evidence supporting a precise and consensual count of “7,000 nerve endings” in plantar skin. The uncritical repetition of such claims has contributed to the consolidation of a quantitative paradigm that implicitly assumes that the therapeutic effect of reflexology depends on the number of nerve endings stimulated—an assumption that does not correspond with the principles governing the organization and function of the somatosensory system.

As discussed in previous research, contemporary reflexology requires a conceptual revision that distances it from oversimplified explanations lacking verifiable support and situates it within a physiological framework consistent with current neuroscientific knowledge [

3,

4,

12]. From this perspective, the issue lies not solely in the inaccuracy of the cited number, but in the reductionist interpretation of the mechanism of action underlying plantar stimulation.

In sensory neurophysiology, cutaneous function is explained by the functional qualities of cutaneous receptors, understood in terms of their degree of specialization, adaptive properties, receptive field, tissue depth, and integration within somatosensory afferent pathways [

5,

6]. Nerve receptors act as dynamic transduction systems capable of converting mechanical stimuli into meaningful neural signals, which are subsequently modulated and processed at the level of the central nervous system.

Plantar skin exhibits a highly specialized sensory organization related to functions of support, balance, and fine mechanical perception, involving different types of free and encapsulated nerve receptors. Accordingly, the manual stimulation used in reflexology can be understood as a process of functional activation of plantar sensory receptors and central modulation of afferent information, without the need to invoke arbitrary or unverified numerical claims [

3].

The aim of this article is to critically review the use of quantitative arguments regarding nerve endings in reflexology texts and to propose an explanatory framework based on sensory neurophysiology that prioritizes the functional role of plantar nerve receptors and their involvement in reflex and regulatory mechanisms associated with plantar stimulation.

Methodology

This article was developed using a narrative review and theoretical analysis design, with the aim of critically examining the quantitative argument regarding the number of nerve endings in the foot as presented in reflexology literature, and of proposing a reinterpretation of its therapeutic action from a neurophysiological perspective, based on the analysis of relevant sources.

A systematic documentary search was conducted in scientific databases using the following keywords: reflexology; plantar nerve receptors; plantar nerve endings; clinical reflexology; neurophysiology; holistic reflexology.

Original articles, reviews, and texts published between 1984 and 2026 in English and Spanish were included. Studies lacking clinical support or presenting an exclusively commercial approach were excluded.

For the review and translation of this manuscript, the artificial intelligence tool ChatGPT, GPT-5 model, developed by OpenAI, was used. The tool was configured to ensure that data and images were not used for the training of artificial neural networks.

General Objective

To critically analyze the use of the “7,000 nerve endings” argument in the reflexology literature and to substantiate, from a neurophysiological perspective, an alternative explanatory framework based on the functional role of plantar nerve receptors involved in the stimulation used in reflexology.

Specific Objectives

To examine the origin and dissemination of the quantitative argument regarding the number of nerve endings in the foot in contemporary reflexology texts and articles.

To demonstrate the absence of verifiable anatomical and neurophysiological evidence supporting a precise count of nerve endings in the foot.

To describe the functional characteristics of cutaneous nerve receptors present in plantar skin, considering their specialization, receptive field, tissue depth, and adaptive properties.

To analyze the role of these receptors in the transduction of mechanical stimuli and their integration within somatosensory afferent pathways.

To propose a reinterpretation of the mechanism of action of reflexology as a complementary therapy based on the functional activation of plantar sensory receptors and the central modulation of afferent information, without recourse to arbitrary or non-verifiable numerical claims.

Neurophysiological Foundations and Conceptual Review of Reflexology

1. Dissemination of the Quantitative Paradigm in the Current Literature

Within the reflexology literature, there is a recurrent dissemination of quantitative arguments attributing the effectiveness of plantar stimulation to the alleged presence of a high number of nerve endings in the foot. Among the most frequently cited figures is the reference to “approximately 7,000 nerve endings,” a number that has been widely reproduced in both educational and popular texts related to the therapy. No anatomical or neurophysiological basis supporting the origin of this figure has been identified [

2,

23,

24,

25]. Furthermore, it is noteworthy that this quantitative argument is not applied equivalently to reflexology practices involving other body regions, such as the hands, revealing a conceptual inconsistency within the therapeutic discourse itself.

Another important aspect to highlight is that the scientific literature does not support the nerve ending figures commonly disseminated in reflexology texts. Contemporary studies describe reflexology as a manual pressure-based intervention applied to reflex zones mediated by nerve receptors, without determining their exact quantity [

14,

15,

16,

17,

18]. For example, Cai et al. (2022) note that research on foot reflexology has increased over recent decades; however, most studies focus on clinical outcomes and general trends rather than on validating specific neurophysiological aspects such as the quantification of nerve terminals [

13]. Similarly, Whatley et al. (2022) define reflexology as a complementary therapy centered on the application of pressure to different body areas and acknowledge that the lack of clarity regarding its mechanism of action represents a methodological challenge in current research, without making reference to numerical counts of nerve endings or their relationship to therapeutic outcomes [

14].

The coexistence of numerical claims and imprecise formulations highlights the absence of scientific consensus surrounding this quantitative approach. Its repeated use has contributed to the consolidation of an explanatory paradigm that privileges the number of nerve endings as the foundation of therapeutic action, shifting attention away from the underlying neurophysiological mechanisms toward an unvalidated numerical argument.

As noted in previous studies, the persistence of such explanations reflects a historical process of legitimizing reflexological practice through simplified arguments that are easily transmitted in educational and divulgative contexts [

2,

23,

24,

25], yet are poorly aligned with current neurophysiological knowledge [

3,

4,

11].

This situation not only hinders dialogue between reflexology and the health sciences, but also limits the development of more rigorous theoretical frameworks by reinforcing the notion that therapeutic effects depend on numerical counts rather than on the functional properties of the sensory receptors involved. A critical review of this quantitative paradigm therefore constitutes a necessary step toward a more coherent and scientifically grounded understanding of the mechanisms underlying reflexology.

2. Anatomical and Neurophysiological Limitations of Nerve Ending Quantification

From an anatomical and neurophysiological standpoint, the notion of a precise count of nerve endings in the foot presents substantial limitations. First, the term nerve ending does not constitute a homogeneous anatomical unit that can be directly quantified, as it encompasses structures of diverse nature, with different morphologies, functions, and degrees of specialization [

5,

7].

Cutaneous innervation is composed of afferent fibers that, as they approach the body surface, may branch into multiple free nerve endings or associate with specialized encapsulated receptors. These terminal arborizations lack discrete boundaries that would allow for a clear definition of what constitutes an individual “ending,” thereby hindering any attempt at absolute counting based on reproducible anatomical criteria [

7,

8].

From a histological perspective, the visualization of nerve endings requires specific staining and immunohistochemical techniques that enable the identification of nerve fibers or neuronal markers, but do not establish a total number of functional endings. Furthermore, the density and distribution of cutaneous innervation vary according to anatomical region, tissue depth, and functional specialization of the skin, which precludes global extrapolations across the entire plantar surface [

8,

9].

In neurophysiological terms, the functional relevance of a nerve ending does not depend on its isolated existence, but on its integration within a system comprising the nerve receptor that transduces the stimulus, the afferent pathway that conveys the information, and the central nervous system that receives, integrates, and modulates it.

A single sensory fiber may innervate a wide or restricted receptive field, exhibit different adaptive properties, and participate in complex central processing circuits [

3]. Numerical quantification of nerve endings bears no direct correlation with the intensity, specificity, or quality of transmitted sensory information [

5,

6] and is conceptually incompatible with the anatomical and functional organization of the somatosensory system.

Although plantar skin exhibits abundant and highly specialized sensory innervation consistent with its biomechanical and perceptual functions, such richness cannot be meaningfully expressed through an absolute count of nerve endings. This limitation underscores the need to abandon simplified quantitative approaches and to advance toward explanatory models centered on the functional characterization of sensory receptors, their neurophysiological properties, and the central modulation mechanisms involved in plantar stimulation.

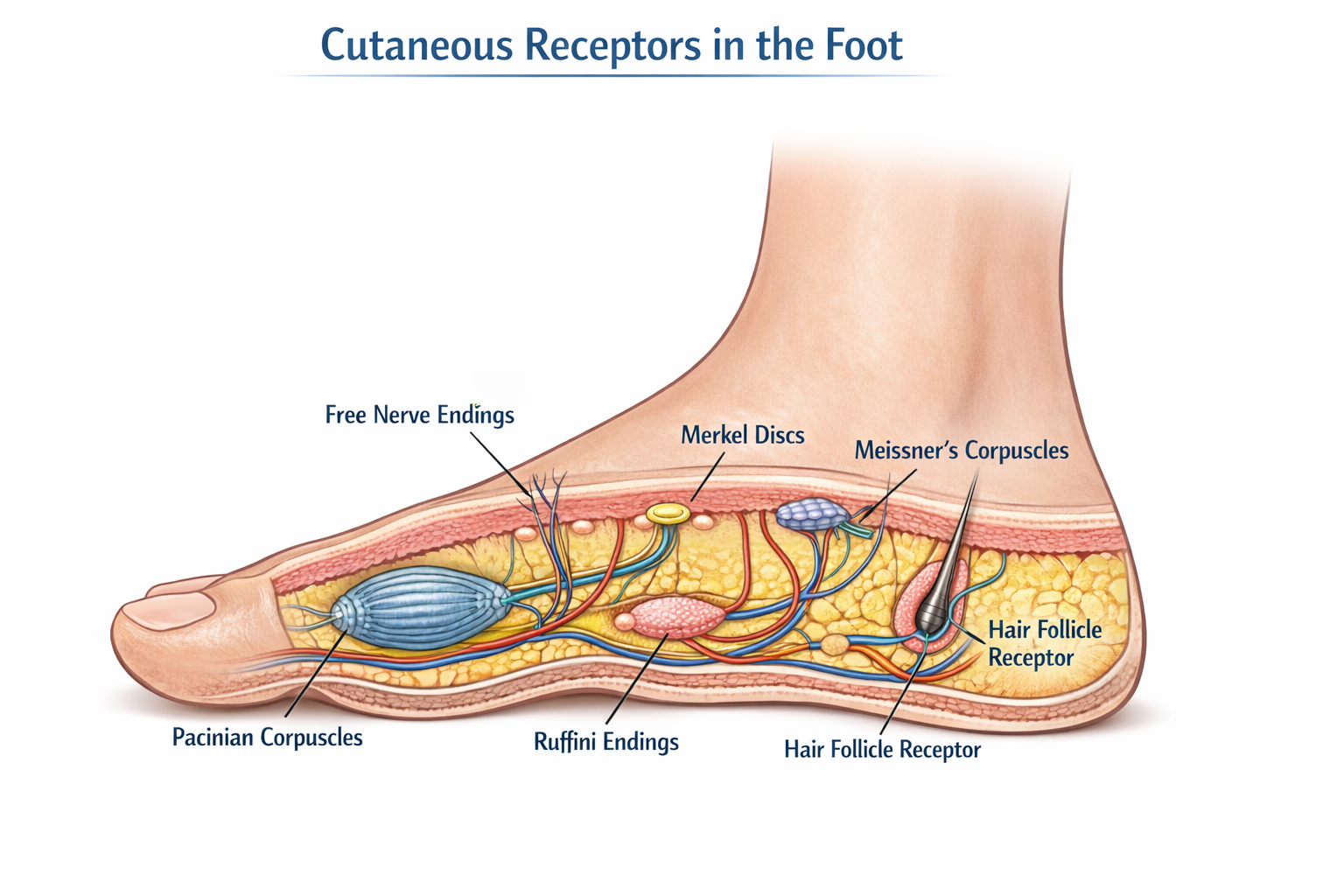

3. Cutaneous Nerve Receptors of the Plantar Skin

Plantar skin is characterized by a highly specialized sensory organization adapted to functions of support, balance, locomotion, and biomechanics. From a neuroanatomical perspective, this region exhibits a high density of nerve receptors whose distribution and functional behavior differ from those observed in other areas of glabrous and hairy skin [

5,

7].

From an anatomical standpoint, human skin is classified into glabrous skin and hairy skin. Glabrous skin, which lacks hair follicles and is found in regions such as the palms of the hands and the soles of the feet, is characterized by a high density of specialized mechanoreceptors. Hairy skin covers most of the body surface and contains hair follicles, exhibiting a sensory organization in which nerve endings associated with hair movement, as well as thermal and nociceptive stimuli, predominate [

5,

6].

Among the principal cutaneous nerve receptors present in plantar skin are rapidly and slowly adapting mechanoreceptors, including Meissner corpuscles, Merkel cell–neurite complexes (Merkel discs), Pacinian corpuscles, and Ruffini endings, along with free nerve endings associated with the perception of mechanical, thermal, and nociceptive stimuli. Each of these receptors exhibits specific properties in terms of activation threshold, adaptation rate, and receptive field size, which determine the type of sensory information transmitted to the central nervous system [

7,

8].

Meissner corpuscles, predominantly located in the superficial layers of the dermis, respond preferentially to rapid changes in mechanical stimulation and low-frequency vibrations, playing a relevant role in the detection of dynamic touch. Merkel cell–neurite complexes exhibit slow adaptation and small receptive fields, making them fundamental for spatial discrimination and the perception of sustained pressure. Pacinian corpuscles, situated in deeper tissue planes, are activated by high-frequency vibrations and rapid pressure changes, whereas Ruffini endings respond to sustained tissue deformation and skin stretch [

5,

10].

This functional diversity helps explain the richness of techniques employed in reflexology practice. The varied and specific technical stimulation applied to reflex zones promotes differential activation of distinct types of sensory receptors, depending on the characteristics of the manual stimulus [

11].

Free nerve endings constitute an essential component of plantar innervation and participate in both mechanical reception, nociception, and thermal perception. They exhibit notable functional plasticity and contribute to the integration of stimuli of different modalities, thereby expanding the spectrum of sensory information generated through manual stimulation of the foot [

8,

9,

11].

From a functional perspective, the relevance of these receptors does not lie in their absolute number, but in their capacity to transduce specific mechanical stimuli into differentiated neural signals, which are subsequently integrated and modulated at the level of the spinal cord and suprasegmental structures. Plantar cutaneous stimulation thus activates complex patterns of somatosensory afferent input whose organization depends on the functional properties of the receptors involved, rather than on a quantitative count of nerve endings.

This approach allows plantar skin to be understood as a dynamic sensory interface in which different types of receptors act in a complementary manner in response to sustained manual stimuli, localized pressure, and tissue deformation—hallmarks of reflexology technique. A qualitative description of plantar cutaneous receptors therefore provides a more coherent neurophysiological foundation for explaining the effects of plantar stimulation than explanations based on unverified numerical figures.

4. Sensory Transduction and Somatosensory Afferent Pathways

Manual stimulation in reflexology activates specialized cutaneous receptors that convert mechanical stimuli into neural signals, a process known as sensory transduction [

3,

4]. Each receptor type—Meissner corpuscles, Merkel cell–neurite complexes, Pacinian corpuscles, and Ruffini endings—exhibits specific functional characteristics, such as rapid or slow adaptation and sensitivity to pressure or vibration, which determine how each stimulus is encoded and transmitted [

19,

20].

The generated impulses travel along somatosensory afferent pathways to the spinal cord and cerebral centers, where they are integrated and modulated, giving rise to local reflex responses and to effects related to physical and emotional balance, relaxation, and overall well-being [

5,

7]. This neurophysiological approach allows reflexology to be understood without reliance on numerical estimates of nerve endings, focusing instead on receptor functionality and somatosensory communication.

Cutaneous sensory receptors of the plantar skin. Image generated using AI: The plantar skin is composed of glabrous skin, characterized by a high density of specialized mechanoreceptors involved in tactile discrimination, pressure perception, and proprioceptive feedback.

The functional diversity of cutaneous nerve receptors present in plantar skin constitutes a central neurophysiological foundation for understanding the variety of techniques used in reflexology practice. Far from responding to an empirical or arbitrary logic, the application of differentiated pressures, sustained stimuli, tissue mobilization, and dynamic contact is associated with the selective activation of distinct types of sensory receptors, each characterized by specific transduction and adaptation properties.

In this context, the varied and targeted technical stimulation applied to reflex zones guides the differential activation of superficial and deep mechanoreceptors, as well as free nerve endings, generating diverse patterns of somatosensory afferent input. These patterns do not depend on the number of nerve endings stimulated, but rather on the functional quality of the applied stimulus and the capacity of the central nervous system to integrate and modulate the incoming sensory information.

This approach is consistent with the definition of reflexology as a complementary therapy based on physiological foundations proposed by Davila (2025), in which the therapeutic action is understood in terms of peripheral sensory stimulation and its neurophysiological integration, without resorting to simplified anatomical explanations or rigid correspondence models. From this perspective, reflexology is defined as a manual intervention acting on somatosensory regulatory systems, contributing to processes of functional modulation at the central level [

3].

The articulation between technical diversity and differential receptor activation provides a neurophysiological basis for contemporary reflexology practice aligned with current neuroscientific knowledge. This explanatory framework reinforces the need to understand reflexology techniques not as standardized maneuvers, but as specific sensory stimuli applied intentionally and contextually, according to the functional properties of the receptors involved.

In this way, the richness of reflexology technique acquires meaning within an integrative physiological model in which reflex stimulation is conceived as a dynamic process of interaction between the sensory periphery and central modulation mechanisms, thereby consolidating reflexology’s definition as a complementary therapy grounded in verifiable neurophysiological principles [

3].

From the Quantitative Paradigm to Functional Integration

The analysis developed throughout this article allows for the integration of anatomical, neurophysiological, and technical levels of inquiry within a coherent explanatory framework for the action of reflexology. The critical review of the quantitative paradigm—centered on the presumed existence of a fixed number of nerve endings in the foot—has highlighted its conceptual limitations and the absence of verifiable foundations supporting such claims.

In contrast, the description of cutaneous nerve receptors in plantar skin and their functional properties enables plantar stimulation to be understood as a qualitative sensory process based on the differential activation of mechanoreceptors and free nerve endings integrated within somatosensory afferent pathways. This approach shifts the explanatory focus away from numerical counting toward receptor function, the nature of the applied stimulus, and the central modulation mechanisms involved.

The diversity of techniques characteristic of reflexology practice thus acquires a precise physiological meaning, insofar as it is oriented toward generating differentiated afferent patterns through specific manual stimuli. This understanding is consistent with the definition of reflexology as a complementary therapy grounded in physiological principles, in which reflex stimulation is conceived as a dynamic interaction between the sensory periphery and central regulatory systems [

3].

In this way, the integration of neurophysiological evidence with the conceptual analysis of reflexology practice makes it possible to consolidate an explanatory model that strengthens the scientific coherence of the discipline, facilitates its dialogue with the health sciences, and promotes a more rigorous and responsible foundation for its clinical and research applications.

Discussion

The conceptual findings of this study highlight the need to critically reassess one of the most widely disseminated arguments in reflexology literature: the attribution of the therapeutic effects of plantar stimulation to the supposed presence of a large and quantifiable number of nerve endings in the foot.

The persistence of figures such as “7,000” or nonspecific references to “thousands of nerve endings” has contributed to the consolidation of a simplified explanatory paradigm, lacking verifiable anatomical and neurophysiological foundations, which continues to be reproduced in educational and divulgative contexts.

The neuroanatomical and neurophysiological analysis developed in this article allows this approach to be questioned without diminishing the sensory richness of plantar skin. On the contrary, the findings indicate that the functional complexity of this region lies in the diversity and specialization of its nerve receptors, as well as in their integration within central somatosensory pathways. From this perspective, the effectiveness of reflex stimulation cannot be explained by a numerical count of nerve endings, but rather by the qualitative characteristics of the applied stimulus and the sensory modulation mechanisms activated in response.

These conceptual findings are consistent with contemporary proposals that seek to redefine reflexology as a complementary therapy grounded in physiological principles, distancing it from mechanistic or symbolic explanations. In particular, the physiological definition of reflexology proposed by Davila (2025) [

3] offers an integrative framework that allows reflexology practice to be understood as a manual intervention aimed at the functional activation of peripheral sensory systems and the central modulation of afferent information.

The discussion presented here does not aim to invalidate the reflexological tradition or dismiss its historical development, but rather to contribute to its conceptual updating in light of current neuroscientific knowledge. Abandoning the quantitative paradigm does not weaken reflexology; instead, it promotes its scientific legitimacy, enhances its capacity for dialogue with the health sciences, and supports a more rigorous clinical and educational practice.

In this regard, the reformulation of the neurophysiological foundations of reflexology constitutes a necessary step toward more coherent explanatory models that prioritize sensory receptor function, the specificity of reflex stimulation, and central integration processes over simplified and non-verifiable arguments.

Conclusions

This article has provided a critical review of the widely disseminated claim regarding the existence of 7,000 nerve endings in the foot as a foundational explanation for the action of reflexology. The anatomical and neurophysiological analysis presented demonstrates that this claim lacks verifiable support and is incompatible with the functional organization of the somatosensory system.

Rather than relying on numerical counts, the relevance of plantar stimulation is grounded in the richness and specialization of cutaneous nerve receptors in plantar skin, as well as in their capacity to transduce specific mechanical stimuli and integrate them within central somatosensory afferent pathways. The effectiveness of reflexology practice is therefore linked to the qualitative nature of the applied stimulus and to the neurophysiological modulation mechanisms activated as a result.

Abandoning the traditional quantitative paradigm does not weaken reflexology as a complementary therapy; on the contrary, it strengthens its scientific coherence and alignment with current neuroscientific knowledge. This shift in perspective contributes to a more rigorous and responsible foundation for the use of reflexology as a complementary therapy, supporting its clinical, educational, and research development.

References

- Marquardt, Hanne. Reflex Zone Therapy of the Feet; Thieme, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Lopez Blanco, A. New Holistic Reflexology Manual. In Robin Book; 2016; ISBN 9788499173887. [Google Scholar]

- Davila, Mabel Alejandra. “Reflexology as a Complementary Therapy: A Critical Review Toward a Definition Based on Its Neurophysiological Action” Preprints. 2025. Available online: https://www.preprints.org/manuscript/202510.2358.

- Davila, Mabel Alejandra. “Reflexology: Historical Evolution of a Therapy Derived from Modern Medical Practice” Preprints; 2026; Available online: https://www.preprints.org/manuscript/202601.1766.

- Kandel, Eric R.; et al. Principles of Neural Science, 6th ed.; McGraw-Hill, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Bear, Mark F.; Connors, Barry W.; Paradiso, Michael A. Neuroscience: Exploring the Brain, 4th ed.; Wolters Kluwer, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Purves, D; Augustine, GJ; Fitzpatrick, D; et al. Neuroscience, 6th ed.; Sinauer Associates: Sunderland, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Guyton, AC; Hall, JE. Textbook of Medical Physiology, 14th ed.; Elsevier: Philadelphia, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Nolano, M; Provitera, V; Caporaso, G; et al. Quantification of epidermal nerve fibers: methodological issues and clinical applications. Clin Neurophysiol. 2015, 126(2), 355–365. [Google Scholar]

- Johansson, RS; Flanagan, JR. Coding and use of tactile signals from the fingertips in object manipulation tasks. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2009, 10(5), 345–359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Davila, Mabel Alejandra. Reflexología Técnicas I; Ediciones Reflexología Clínica Integrativa: Buenos Aires, Argentina, 2024; ISBN 978 6310025049. [Google Scholar]

- Whatley, Judith; et al. 'Reflexology: Exploring the mechanism of action'. Complementary therapies in clinical practice 2022, vol. 48, 101606. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cai, Deng-Chuan; et al. Foot Reflexology: Recent Research Trends and Prospects. Healthcare (Basel, Switzerland) 2022, vol. 11, 1 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rosas-Cervantes, Elisa; et al. Foot Reflexology with Caring Consciousness to Reduce Pain in Older Adults: An Integrative Review. Florence Nightingale journal of nursing 2024, vol. 32(2), 190–197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gong, Zhichao; et al. Effectiveness of musculoskeletal manipulations in patients with neck pain: a protocol for a systematic review and network meta-analysis. BMJ open 2024, vol. 14, 2 e077951. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Embong, Nurul Haswani; et al. Revisiting reflexology: Concept, evidence, current practice, and practitioner training. Journal of traditional and complementary medicine 2015, vol. 5, 4 197–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ernst, E; et al. Reflexology: an update of a systematic review of randomised clinical trials. Maturitas 2011, vol. 68(2), 116–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wyatt, Gwen; et al. Reflexology and meditative practices for symptom management among people with cancer: Results from a sequential multiple assignment randomized trial. Research in nursing & health 2021, vol. 44(5), 796–810. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnson, Kenneth O. The Roles and Properties of Cutaneous Mechanoreceptors. Current Opinion in Neurobiology 2001, vol. 11(no. 4), 455–461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Johansson, Roland S.; Björkman, Anders. Mechanoreceptor Activity and Texture Perception. Neuroscience & Biobehavioral Reviews 1984, vol. 8, 1–19. [Google Scholar]

- Davila, Mabel Alejandra. Pediatric Reflexology: Therapeutic Approach in Babies, Children, and Adolescents. In Ed. Dunken; 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Harms, Ann; Quisel, Stephanie. Total Reflexology: The Reflex Points for Physical, Emotional, and Psychological Healing, 2nd ed.; Rockridge Press, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Norman, Laura. Feet First: A Guide to Foot Reflexology; Touchstone, 1988. [Google Scholar]

- Lopez Blanco, A. “Holistic Reflexology Manual” ISBN 9788499172460; Robin Book, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Cattin, Juana. I fell in love with reflexology. Do you know why? In Impresiones SAC; 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Nakamaru, T.; Miura, N.; Fukushima, A.; Kawashima, R. Somatotopical relationships between cortical activity and reflex areas in reflexology: A functional magnetic resonance imaging study. Cortex 2008, 44(7), 931–939. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).