1. Introduction

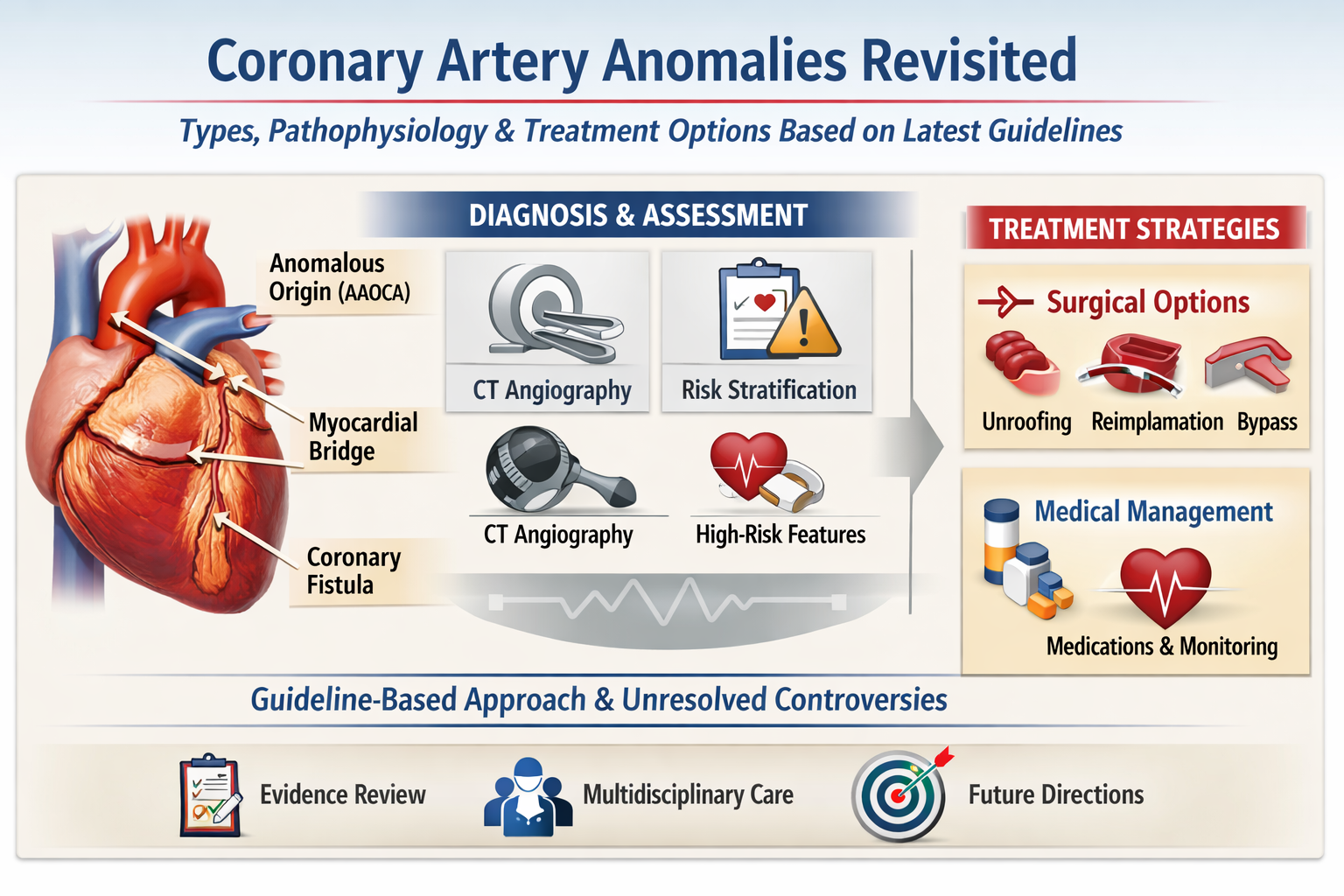

Coronary Artery Anomalies (CAAs) are a diverse group of congenital anomalies affecting the coronary arteries, which supply oxygen-rich blood to the heart. These arteries are crucial for maintaining cardiac function and overall heart health. CAAs are considered rare since they occur in only less than 1% of the general population, with a wide range of clinical and anatomical presentations. Several classification systems exist, though this review will focus on the two most common. While often asymptomatic, CAAs can lead to severe cardiovascular complications such as myocardial infarction, arrhythmias, and sudden cardiac death (SCD). They are the second leading cause of SCD in competitive athletes and a significant cause among young individuals overall. (1,2)

Although existing research provides valuable insights into the anatomical variations and risks associated with CAAs, comprehensive data on the long-term prognosis of different CAA types are still lacking. The genetic and developmental factors contributing to these anomalies remain poorly understood, highlighting a significant gap in the literature.

This review aims to clearly present the different types of CAA, their clinical management and provide recommendations for their treatment.

2. Normal Coronary Artery Anatomy

To further understand these anomalies, we must discuss what is considered normal and abnormal anatomy regarding the coronary arteries. Angelini and colleagues proposed defining "normal" coronary anatomy as any morphological feature with a prevalence greater than 1% in the general population. This also includes normal variants that are considered “unusual” but still found in >1% of the population.

Table 1 shows the different qualitative and quantitative criteria used by Angelini to describe these normal features (2). (

Table 1)

There are three main epicardial coronary arteries: the right coronary artery (RCA), which emerges from the right sinus of Valsalva (RSV), the left anterior descending (LAD) and left circumflex (LCX) coronary arteries. The LAD and LCX arteries are initially connected by a common tract, the left main coronary artery (LMCA), which arises from the left sinus of Valsalva. There are two to four coronary ostia located at the upper mid-section of the left and right sinuses of Valsalva.

The right coronary artery (RCA) originates from the RSV traveling between the pulmonary artery (PA) and the right atrial appendage. It follows the right atrioventricular sulcus moving around the front and right side of the heart between the right atrium and PA and then turns toward the posterior part of the heart, continuing along the diaphragmatic surface. It primarily supplies blood to the right side of the heart, including the right atrium and ventricle, and typically measures between 12 and 14 cm in length. (3–5)

The RCA is generally categorized into three segments: the proximal segment (from its starting point to halfway down the acute margin), the middle segment (from the previous point to the acute margin), and the distal segment (from the acute margin to the base of the heart).

As it travels, the RCA gives rise to multiple branches, such as the conus branch (supplying the right ventricular outflow tract), the atrial branch , the sinus node artery (supplying the sinoatrial node), the right marginal branch (supplying the right ventricular wall), the atrioventricular nodal branch (supplying the atrioventricular node), the posterior descending artery (PDA) (supplying the right ventricular inferior wall), and the posterolateral branch (PLB) (supplying the inferior wall of the left ventricle). (6–8) The PDA along with PLB define what is considered left, right or co dominance: 80 to 85% of the hearts are right dominant because the PDA and PLB arise from the RCA. The remaining 15- 20% are divided between left dominance (~10%) and codominance (~20%). (9)

The left main coronary artery (LMCA) arises from the left sinus of Valsalva (LSV) and typically passes between the main pulmonary artery and the left atrial appendage before entering the coronary sulcus. The LMCA generally does not have significant branches of its own but quickly bifurcates into the LAD and the LCX.

The LAD arises from the bifurcation of the LMCA, looping around the left side of the pulmonary artery, and descends obliquely in the anterior interventricular sulcus towards the apex of the heart, giving rise to the diagonal and septal branches. It travels within the epicardium and can be divided into three segments: proximal (up to the origin of the first septal perforator), middle (from the septal perforator origin to the halfway point to the apex), and distal (from this hallway point to the apex). The LAD supplies the anterior wall, the apex, and the anterior two-thirds of the interventricular septum through its diagonal and septal branches. (3,5,10)

The LCX also arises from the bifurcation of the LMCA, follows the atrioventricular groove and goes between the left atrium and ventricle to the coronary sinus, it gives rise to the obtuse marginal branches. Unlike the RCA or LAD, the LCX only has two segments: the proximal segment (from its origin to the first obtuse marginal branch) and the distal segment (beyond the first obtuse marginal branch). The LCX supplies the lateral wall of the left ventricle and in some cases, it may also give rise to the left marginal artery or a posterolateral branch, contributing to the blood supply of a portion of the inferior wall. (3,5)

Figure 1 illustrates the course of the coronary arteries, and their various segments as described above.

3. Epidemiology and Classification of CAA

The incidence of CAAs is profusely debated in literature. This is most likely due to the different varieties of criteria used to describe what is a CAA, what is considered as normal and abnormal in coronary anatomy and the fact that most CAAs are asymptomatic and therefore never undergo appropriate diagnostic imaging. With this in mind, we can also see a difference in the incidence of coronary anomalies identified during autopsy studies compared to coronary imaging studies. Moreover, even within coronary imaging techniques, variations exist between coronary computed tomography angiography (CCTA) and invasive coronary angiography (ICA), with CCTA appearing to be more effective. In a large angiographic study involving 126,595 coronary angiograms (ICA) in an asymptomatic population, coronary anomalies were detected in 1.3% of cases. Among those with CAAs, the most prevalent anomaly was a separate origin of LAD and CX in left sinus of Valsalva (LSV) accounting for 30.4% of the cases, followed by CX from RSV or RCA (27.7% of the cases). This study does not consider myocardial bridges as CAA’s, because it's sometimes referred as a normal variant since it has a much higher prevalence than the other anomalies (11,12)

In a separate study conducted in Zurich, the authors compared the diagnostic performance of CCTA and ICA. CCTA was performed in 1759 symptomatic patients while ICA was performed in 9372 symptomatic patients, their symptoms being dyspnea and anginal pain. CAAs were found in 7.9% of patients who underwent CCTA, with the most prevalent finding being myocardial bridges (42.8% of CAAs) VS 2.1% with ICA, with the most prevalent finding being an absent left main trunk. While differences in prevalence across studies clearly depend on the imaging modality used, CCTA remains the gold standard, as it offers detailed characterization of high-risk coronary anomalies, enables visualization of both cardiac and extracardiac structures, and provides accurate assessment of their three-dimensional relationships. Finally, autopsy studies demonstrate a higher prevalence of CAAs compared to ICA findings but report a prevalence similar to CCTA, ranging between 2% and 7%. (5,13,14)

There is multiple classification systems used throughout the literature, but the two most used ones base themselves on different criteria: the first one is proposed by Gentile et al which uses anatomical criteria to describe these anomalies. In this classification there are three categories: origin, course and termination anomalies (

Table 2). Origin anomalies can be further divided into three subcategories: pulmonary origin, aortic origin and congenital atresia of the left main trunk. (14)

The second classification system is the one proposed by Rigatelli et all which is based on clinical significance, classifying the anomalies who have the highest probability to lead to myocardial ischemia and, in the most severe cases, to SCD or another coronary artery disease (CAD). There are four categories: benign, relevant, severe and critical (

Table 3). This functional classification will be mostly used to review the clinical significance aspects of CAAs. (15)

4. Pathophysiology: Localization and Severity of Risk

4.1. Origin Anomalies

These anomalies are grouped by where the ostium of the anomalous coronary artery is located. It can either be an anormal origin from the aorta or from the pulmonary artery. Origin anomalies also include congenital atresia of the left main trunk, characterized by the absence of the LMCA.

4.1.1. Congenital Atresia of the Left Main Trunk

This anomaly is a rare condition and has two different types of presentation: LCX and LAD can each have an independent origin, which is anatomical variant, and has a prevalence of 0.41% to 0.67% with no clinical consequence or it can be a much rarer but serious form, left main trunk hypoplasia, characterized by the absence of a true left main trunk. Collateral vessels are then formed between the coronary arteries; however, they are usually insufficient to adequately perfuse the LV and therefore leading to myocardial ischemia, in most cases, during the first year of life (Class II Rigatelli) (14,16). (

Figure 2).

4.1.2. Anomalous Pulmonary Origin of the Coronary Arteries (APOCA)

Anomalous pulmonary origin of the coronary arteries (APOCA) is a rare group of anomalies where pathophysiological consequences are closely linked to the vessel involved and the degree of collateral circulation. From this group, anomalous origin of the LCA (ALCAPA) and RCA (ARCAPA) from the PA are the two most clinically significant (respectively class II and III Rigatelli). (

Figure 3)

ALCAPA, also known as Bland-White-Garland syndrome, represents 1 in 300 000 births (0.08%) and is associated with a 90% mortality if it goes untreated during the first year of life, which is why it is part of the critical infant-type coronary anomalies. During the first month of life, babies present a physiological pulmonary hypertension, which keeps blood flowing into de LCA, keeping patients asymptomatic. As pulmonary resistance drops, a left- right shunt is created between the LCA and pulmonary circulation which results in a “steal” of blood flow from the heart. (14,16–19)

On the contrary ARCAPA is usually diagnosed later in life (average at 22.8 years) and is less prevalent than ALCAPA. Patients can present angina- like episodes, symptoms of heart failure and SCD; however, they are usually asymptomatic or mildly symptomatic. The proposed pathophysiology begins after birth with the flow of deoxygenated blood from part of the PA into the RCA. In later stages, collateralization and tortuosity of both coronary arteries occur, with retrograde flow into the PA and left coronary steal phenomenon (3,13,20).

4.1.3. Anomalous Aortic Origin of the Coronary Arteries (AAOCA).

The last group that we need to mention is the anomalous aortic origin of the coronary arteries (AAOCA). This group includes single coronary artery, inverted coronary artery, anomalous origin of the left anterior descending or circumflex artery from the right coronary artery, and anomalous coronary artery from the opposite sinus (ACAOS). This one represents a large group of anomalies with significant clinical importance since it’s a significant cause of SCD in athletes and young adults. This subgroup includes anomalous origin of LCA from RSV(AAOLCA), anomalous origin of the RCA from LSV (AAORCA) and anomalous origin of the LCX from RSV. We will mostly discuss the two first anomalies since they are both more clinically significant in comparison to anomalous origin of the LCX from RSV, which can be considered a benign variant if it is not associated with atherosclerosis. (3,5,21)

AAORCA is more common (0.03%–0.92%) than AAOLCA (0.03%), but AAOLCA is more clinically significant (

Figure 4 and

Figure 5). While both anomalies are linked to sudden cardiac death (SCD), a study analyzing 1,866 cases of SCD among American athletes found that 17% were due to coronary anomalies, with AAOLCA being the most frequently implicated. Therefore, both anomalies can be classified as class III Rigatelli. ACAOS can be further categorized depending on the course of the anomalous coronary artery, which will drastically change de prognosis of these anomalies: interarterial, pre-pulmonic, subpulmonic (transseptal), retroaortic and retrocardiac (

Figure 5). The interarterial course is most frequently associated with high-risk features of ischemia and SCD due to several anatomical and physiological factors. These include an acute-angled takeoff from the aorta, a slit-like lumen, both of which can limit blood flow and an intramural course (the coronary artery runs through the aortic wall,

sharing the tunica media with the aorta), which makes the artery prone to compression, particularly during systole (

Figure 6). While the exact pathophysiological mechanisms underlying ACAOS are not yet fully understood, all clinical manifestations—angina, arrhythmias, dyspnea, syncope and SCD, ultimately result from a limited coronary reserve (2,3,5,13,14,19,22,23).

4.2. Course Anomalies

These are the most prevalent CAA since they include myocardial bridges (MBs) and coronary artery aneurysms, which have a higher prevalence than all other CAA’s. From a strictly epidemiological perspective, these anomalies should not be classified as true CAAs due to their high prevalence (found in approximately 1 in 4 individuals). However, they continue to be widely included in the classification of coronary anomalies.

4.2.1. Myocardial Bridges

MBs are anatomical anomalies where a segment of a coronary artery (most commonly the proximal segment of the LAD) takes an intramyocardial course, resulting in compression of the artery during systole. The muscle covering the artery is known as the MB, while the segment running within the myocardium is referred to as the tunneled artery.

Myocardial bridges were for a long time considered as a completely benign phenomenon. This was majorly because coronary blood flow occurs majorly during diastole, but MB affects compression during systole and therefore only a small portion (15%) of coronary blood flow would be compromised. In reality, it’s not as straightforward: depending on the depth and length of the segment affected, different degrees of malignancy would be shown. Angelini and his colleagues used a score system to approximatively estimate the severity of MB, taking systolic narrowing and the length of the stenotic segment into consideration (

Table 4). This score was used in Rigatelli’s scale to differentiate class 1 and 3 MBs. Unfortunately, it’s not as clear as that, since multiple studies show that the correlation between systolic narrowing, affected length and depth have not been clearly demonstrated. However, these three components have demonstrated various implications in management and surgical treatment, which will be discussed further in this paper. (24–27)

The pathophysiology of MBs that may lead to myocardial ischemia and symptoms such as angina, stress cardiomyopathy, dyspnea, and other angina equivalents is related to the dynamic effect of systolic compression: multiple angiographic and IVUS (intravascular ultrasound) studies showed that after systolic compression, there is a delay in dilation of the bridged segment during diastole. This delay does not allow early diastolic perfusion, which is more significant in the sub endocardium which is already more prone to ischemia. The systolic compression observed during angiographic examination is called “milking phenomenon” because the affected segment seems to get squeezed by systolic pressure and then released (25,28).

4.2.2. Coronary Artery Aneurysms

Coronary aneurysms are the second type of course anomaly that we will discuss. They are defined as a focal dilatation of a coronary exceeding 1.5 times the diameter of the adjacent normal segment but involving less than 50% of the vessel length (VS coronary artery ectasia that’s involve more than 50% of the vessel length). (

Figure 7) There are two kinds of aneurysms: saccular and fusiform (these are most found in the LAD). The prevalence of these anomalies is of 1.4% in a population referred for coronary angiography. The pathophysiology leading to ischemia symptoms are poorly understood but the most common etiology is atherosclerosis in adults and Kawasaki disease in children. The presence of thrombi within the aneurysm lumen is frequent and can also lead to ischemic symptoms (14,23,29,30).

4.3. Termination Anomalies

Termination anomalies include coronary artery fistulas (CAF) and coronary stenosis. Coronary artery fistulas are defined by an abnormal communication between the coronary artery and a heart chamber (most commonly being the right ones), the coronary sinus, a great vessel or other vascular structure. They affect 0.1 to 0.2 % of the population, and most of the time they are asymptomatic (class II Rigatelli). 90% of CAFs drain into the right heart chambers but drainage into the left heart chambers is also possible.

Among the possible complications, CAFs can cause a coronary steal phenomenon, leading to progressive dilatation and tortuosity of the affected vessel. This dilatation can be self-sustaining resulting in giant CAFs (> 8mm diameter), tortuous and polyangular coronary arteries. One or multiple may be present in a single patient. Potential complications include thrombosis, stenosis, myocardial ischemia, ventricular dysfunction, rupture, heart failure, and even cardiogenic shock.

Clinically, the presentation varies with age: in newborns, it typically manifests as heart failure, whereas in adults, the clinical picture is more often that of myocardial ischemia, SCD, pulmonary hypertension, heart failure, arrhythmia, rupture, or endocarditis- symptoms that will most commonly appear in the fifth or sixth decade of life (5,19,31). (

Figure 7)

Figure 8.

Coronary arteriovenous fistula: Circumflex Artery draining Directly into the Coronary Sinus. (A,B) Three-dimensional volume-rendered image showing the circumflex artery giving rise to an arteriovenous fistula draining directly into the coronary sinus. (C,D) CCTA image demonstrating the course of the circumflex artery–to–coronary sinus fistulous connection.

Figure 8.

Coronary arteriovenous fistula: Circumflex Artery draining Directly into the Coronary Sinus. (A,B) Three-dimensional volume-rendered image showing the circumflex artery giving rise to an arteriovenous fistula draining directly into the coronary sinus. (C,D) CCTA image demonstrating the course of the circumflex artery–to–coronary sinus fistulous connection.

5. Management and Treatment

Different imaging techniques can be used to observe and diagnose coronary artery anomalies. It is also crucial for risk stratification, and management of CAAs. They are used to characterize the coronary anatomy and identify high-risk features that have a higher association to myocardial ischemia or SCD. Coronary computed tomography angiography (CCTA) is commonly the first-line imaging technique, since it is considered the gold standard in the assessment of CAAs due to its high spatial resolution and ability to determine the origin, course, and termination of anomalous coronary arteries, it is also more applicable for population studies. However, other modalities such as cardiac magnetic resonance (CMR) imaging and stress testing can provide additional functional and structural information, including evidence of ischemia or myocardial scarring. Echocardiography is also useful, particularly in the pediatric population since it is a non-invasive, widely available imaging modality that can be performed routinely in symptomatic children (3,10,14,19,32).

Table 5 and

Table 6 present a comparative analysis of current guideline recommendations for the evaluation of CAAs.

5.1. Origin Anomalies (Table 7-A)

5.1.1. Aortic Origins

While both US and European guidelines recommend surgical intervention in the presence of symptoms or objective evidence of ischemia, their approaches differ when addressing management of asymptomatic patients and the place of anatomical “high-risk” features.

Both recommended surgery for patients with AAOLCA in the absence of symptoms and ischemia. The European guidelines also include AAORCA in this case of figure, while US guidelines are more specific and only mention AAOLCA, due to higher SCD risk. The US guidelines also recommend surgery repair for ventricular arrythmias, which is not specifically mentioned in the European guidelines.

High-risk anatomical features such as a slit-like orifice, interarterial or intramural course, and acute angulation are recognized by both U.S. and European societies as contributing to risk stratification. The absolute risk of SCD, however, remains difficult to quantify, and earlier estimates may be overestimated. The European guidelines also mention that surgery may be considered for AAOLCA in asymptomatic patients without high-risk anatomy for those under 35. Both societies agree on considering clinical presentation, anatomical features, age, level of physical activity, and patient preferences.

Importantly, for asymptomatic patients without ischemia or arrhythmia, the benefit of surgical correction remains uncertain, especially without high-risk features.

Once surgery has been chosen, different techniques are available. The ultimate goal of surgery is to “free” the anomalous coronary artery, as the main issue usually lies in the constriction of the artery, which is compressed between cardiac structures. In the presence of a long intramural course, the most used technique is unroofing, which involves incising and separating the common wall between the aorta and the intramural coronary segment to create a neo-ostium in the correct sinus. This technique is generally effective and associated with excellent operative outcomes. However, if the anomalous segment is closely related to the aortic valve commissure, surgical unroofing is associated with coronary reimplantation, to prevent possible complications such as aortic insufficiency. Ostioplasty is often used with unroofing, and it consists of enlarging the coronary ostium, using a pericardial patch, and it’s reserved for slit like, or stenotic ostium. If the intramural course is short or absent, the recommended technique is coronary reimplantation in the correct sinus of Valsalva. Though technically demanding due to the fragility of the coronary artery wall and difficulties in estimating graft length during surgery, it may offer a more correct anatomical and durable result.

Although surgical unroofing has long been considered the standard approach for intramural AAOCA due to its technical simplicity and historically favorable outcomes, recent evidence shows that coronary reimplantation may offer superior long-term results (

Figure 9 A-B). In a recent single-center study of 230 patients, 123 underwent reimplantation while 86 had unroofing. Although both techniques showed excellent outcomes with no early or late deaths, the rate of reoperation was remarkably higher in the unroofing group (5.8%) compared to 0% in the reimplantation group. The unroofing cohort experienced recurrent ischemia, residual narrowing, and complications related to aortic valve commissure manipulation, particularly in cases of short or anatomically complex intramural segments. As experience with reimplantation grew, the surgical team transitioned to using it as the preferred technique for all intramural cases, since it avoids many of these issues while maintaining a low risk profile and excellent functional outcomes. (4,20,21,33–37)

Coronary artery bypass graft (CABG) is generally reserved for older, high-risk patients who present with coronary artery disease such as atherosclerosis or when anatomical repair is not doable. This eliminates the need to open the aorta and manipulate the coronary arteries. The problem with this technique is the competitive flow that is created: since the anomalous coronary artery is still in place and has preserved flow, the bypass graft is underutilized, which can lead to graft failure over time. (14,32,35,37)

In the case where AAOCA takes an interarterial course, pulmonary artery translocation can be done to deconstruct the coronary artery and increase space between the great vessels. It may be associated with unroofing.

Finally, in cases of AAOCA with a transeptal course, the surgical repair differs depending on if the transeptal segment is more superficial or rather deep in the septum. If it’s superficial, a posterior approach is preferred where the PA is transected to have access to the transseptal coronary artery, the overlying muscle is separated, and the pulmonary root is reattached. If the segment is deeper, a newer technique is used: the transconal (or infundibular) unroofing. In this technique the right ventricular outflow tract (RVOT) is incised, just below the pulmonary valve, and the anomalous coronary artery in unroofed through the posterior wall of the right ventricle. A pericardial patch is then placed on the posterior RVOT to elongate and reconstruct this portion of the outflow tract following unroofing. (32,33,35,38,39).

The use of percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI) is still debated given the lack of evidence to support it (only case reports and small series). While PCI may effectively treat distal atherosclerotic lesions, it does not address the underlying anatomical anomaly of the coronary artery. Although some adult cases report symptomatic relief, restenosis of the stented segment remains a concern in the long-term, as does the ability of the stent to withstand dynamic compression in these non-atherosclerotic vessels. Currently, PCI can be considered as a potential option for older non-surgical candidates but pending until stronger longitudinal data is available. (3,32,40,41)

5.1.2. Pulmonary Origins

American and European guidelines are completely in agreement regarding the management of APOCA. Surgery is recommended for patients with ALCAPA and in symptomatic patients with ARCAPA. Surgery should be considered in asymptomatic patients with ARCAPA with ischemia or ventricular dysfunction.

There are various surgical techniques available, all aiming to restore a dual coronary system capable of supplying the entire myocardium with oxygenated blood. The preferred technique is direct reimplantation of the coronary artery in the correct sinus (coronary button technique) (

Figure 10 A-B) : a circular portion of the PA around the anomalous coronary ostium (hence the name button) is taken and implanted in the correct site of the aorta. This technique is preferred in pediatric patients because their arteries are less friable and more resilient, making them better suited to tolerate this type of surgical manipulation. When the coronary artery is not long enough and the feasibility of direct reimplantation is not possible, the Takeuchi procedure represents an alternative option: a flap of the PA wall is done as to create an intrapulmonary tunnel connecting the anomalous ostium to a newly created neo-ostium in the aorta. Finally, CABG surgery may also be an option: this technique involves the ligation of the anomalous CA at its origin and connecting the anomalous CA to the aorta via a venous or arterial graft. Different factors influence surgical risk and operative outcomes, including decreased preoperative left ventricular function and younger age at the time of surgery. Although surgical outcomes for procedures aimed at restoring a dual coronary circulation have significantly improved in recent years, long-term data remains limited. Nevertheless, most patients experience recovery of left ventricular function and are no longer considered at high risk for SCD (10,42–45). (

Figure 10)

5.1.3. Atresia Left Main Trunk

As previously mentioned, this anomaly frequently results in myocardial ischemia, and therefore prognosis without surgical repair is poor. Typically, treatment involves a bypass graft using either a saphenous vein or an internal mammary artery (in some case reports, both vessels were used as a single graft was insufficient). Surgical outcomes have generally been excellent. (2,5,46,47)

5.2. Course Anomalies (Table 7-B)

Management of myocardial bridges is complex due to the wide variety of treatment options and the importance of risk factors such as the degree of systolic narrowing, affected length and depth, which impact therapeutic decisions. In asymptomatic patients, management should include relieving vasoconstrictive triggers (coronary vasospasm, smoking and other stimulants, etc.) and appropriate treatment for CAD (antiplatelet treatment). In symptomatic patients, first line treatment is pharmacotherapy: Beta-blockers are preferred for their negative inotropic and chronotropic effects. Conversely, nitrates are contraindicated due to their indirect positive chronotropic and ionotropic effects, which reduces coronary perfusion. Second line treatment includes PCI and surgery. PCI use is still widely debated given the high rates of in-stent restenosis and a lack of randomized and long-term data. Regarding surgical treatment, CABG is preferred for long or deep bridged segments. Myotomy, which consists of dissecting the overlying muscle, to free the compressed portion, is preferred when the bridge is more superficial and in pediatric population since this technique doesn’t address the underlying endothelial dysfunction, which is less/ not present in younger patients. (24,25,27,28,48)

Treatment of coronary aneurysms is strongly individualized, taking into consideration multiple factors such as the presence of symptoms, etiology, expansion rate, location, size, and the presence of CAD to guide case-by-case decisions. There is an ongoing debate on anti-thrombotic therapy: although there's a potential risk of thromboembolism, the decision to use antithrombotic therapy remains controversial given the contradictory study findings, leading to a lack of consensus. Invasive treatment consists of PCI and surgery and is reserved for symptomatic patients. PCI is preferred for smaller aneurysms (58-10 mm in diameter) using covered stents or coil embolization, which is preferable for wide-neck aneurysms. Surgery is preferred for larger aneurysms (>10 mm) or patients with obstructive CAD, and the available surgical options include aneurysmectomy, marsupialization and complete ligation of the aneurysm with CABG, which is the most used technique. (29,39,49–51)

5.3. Termination Anomalies (Table 7-C)

When it comes to small coronary fistulae (diameter <1 time the largest diameter of the CA not involved in the CAF), they tend to close spontaneously so no treatment is initiated with only clinical follow-up over the years, as recommended by the 2020 European guidelines. In medium or larger CAF (respectively ≥ 1 to 2, >2 times) treatment is recommended by European guidelines in the presence of symptoms, complication, or significant shunt and the 2018 American guidelines recommend an evaluation by specialized Heart Team. The aim of intervention is to close and stop blood flow from going into the fistula. PCI is the preferred technique (percutaneous transcatheter closure) though its approach changes depending on if it’s a proximal or distal CAF (respectively arterial or venous access) but it’s not always feasible. Surgical intervention may be necessary if fistulas are multiple, tortuous, draining into multiple sites or associated with aneurysms and the usually preferred technique is ligation at the drainage site of the CAF. (19,31,52–55)

Based on this review, a simplified algorithm for decision-making regarding treatment modalities in CAAs is presented in

Table 7.

6. Conclusions

Coronary artery anomalies, although rare, with a prevalence of typically less than 1% in the population, represent a diverse and clinically significant group of coronary disorders. While often asymptomatic, they can cause severe cardiovascular complications, including myocardial ischemia, arrhythmias, and are the second most frequent cause of SCD in competitive athletes and young individuals. This review shows the importance of creating clear and accurate classification systems and imaging techniques, in order to enable effective diagnosis, risk stratification and appropriate management strategies. Furthermore, understanding the pathophysiology is important in guiding management since anatomical benign variations are common in the general population. CAAs can be classified based on their anatomical features or based on their clinical significance.

Anomalous origins from the aorta and from the pulmonary artery, particularly those with high- risk features such as an interarterial or intramural course, acute-angled takeoff, and a slit-like lumen, have been more thoroughly studied in recent years, which has contributed to the development of international recommendations even though the class of recommendation is not always strong. This is probably due to the strong association of these anomalies with SCD. On the other hand, course and termination anomalies have received far less attention and are missing their own international recommendations which is unfortunate because although their association with SCD is less pronounced, they are still linked to a multitude of cardiovascular complications.

Management strategies are highly individualized, often involving surgical intervention in cases of symptomatic patients, high-risk anatomy or objectivated ischemia. PCI and medical therapy are also possible treatments: for certain types of anomalies, they represent the primary recommendations, however, this depends on the specific anatomy.

The optimal management for each CAA continues to evolve and more studies, especially with long-term follow-up, are needed to refine treatment strategies and improve prognoses for all kinds of CAA.

References

- Tso, JV; Cantu, SM; Kim, JH. Case series of coronary artery anomalies in athletes. JACC Case Rep. 2022, 4(17), 1074–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Angelini, P. Coronary artery anomalies. Circulation. 2007, 115(10), 1296–305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gaudino, M; Di Franco, A; Arbustini, E; Bacha, E; Bates, ER; Cameron, DE; et al. Management of adults with anomalous aortic origin of the coronary arteries: state-of-the-art review. Ann Thorac Surg [Internet]. 16 Oct 2023, 0. Available online: https://www.annalsthoracicsurgery.org/article/S0003-4975(23)00977-3/fulltext.

- Angelini, P. Coronary artery anomalies—current clinical issues. Tex Heart Inst J. 2002, 29(4), 271–8. [Google Scholar]

- Villa, AD; Sammut, E; Nair, A; Rajani, R; Bonamini, R; Chiribiri, A. Coronary artery anomalies overview: the normal and the abnormal. World J Radiol. 2016, 8(6), 537–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Angelini, P. Normal and anomalous coronary arteries: definitions and classification. Am Heart J. 1989, 117(2), 418–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- The Radiology Assistant: Coronary anatomy and anomalies [Internet]. 13 Sep 2024. Available online: https://radiologyassistant.nl/cardiovascular/anatomy/coronary-anatomy-and-anomalies.

- Izhar, M. Right coronary artery [Internet]. Radiopaedia. 13 Sep 2024. Available online: https://radiopaedia.org/articles/right-coronary-artery.

- Hacking, C. Coronary arterial dominance [Internet]. Radiopaedia. 20 Sep 2024. Available online: https://radiopaedia.org/articles/coronary-arterial-dominance.

- Rickert-Sperling, S; Kelly, RG; Haas, N. Clinical presentation and therapy of coronary artery anomalies. In Congenital Heart Diseases: The Broken Heart. Advances in Experimental Medicine and Biology [Internet]; Available from; Springer: Cham, 2024; pp. 799–809. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yamanaka, O; Hobbs, RE. Coronary artery anomalies in 126,595 patients undergoing coronary arteriography. Cathet Cardiovasc Diagn. 1990, 21(1), 28–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cademartiri, F; La Grutta, L; Malagò, R; Alberghina, F; Meijboom, WB; Pugliese, F; et al. Prevalence of anatomical variants and coronary anomalies in 543 consecutive patients studied with 64-slice CT coronary angiography. Eur Radiol. 2008, 18(4), 781–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- González-Hoyos, D; López-Arroyave, M; Sebastián-Quiñones, J; Abad-Díaz, P; Carvajal-Vélez, MI. Anomalías de las arterias coronarias: una revisión de la literatura y propuesta de una nueva clasificación. Rev Colomb Cardiol. 2024, 30(6), 11440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gentile, F; Castiglione, V; De Caterina, R. Coronary artery anomalies. Circulation. 2021, 144(12), 983–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rigatelli, G; Docali, G; Rossi, P; Bandello, A; Rigatelli, G. Validation of a clinical-significance-based classification of coronary artery anomalies. Angiology. 2005, 56(1), 25–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shriki, JE; Shinbane, JS; Rashid, MA; Hindoyan, A; Withey, JG; DeFrance, A; et al. Identifying, characterizing, and classifying congenital anomalies of the coronary arteries. RadioGraphics. 2012, 32(2), 453–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peña, E; Nguyen, ET; Merchant, N; Dennie, C. ALCAPA syndrome: not just a pediatric disease. Radiographics. 2009, 29(2), 553–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xiao, Y; Jin, M; Han, L; Ding, W; Zheng, J; Sun, C; et al. Two congenital coronary abnormalities affecting heart function: anomalous origin of the left coronary artery from the pulmonary artery and congenital left main coronary artery atresia. Chin Med J (Engl). 2014, 127(21), 3724–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lucron, H. Anomalies coronaires congénitales: comment les reconnaître? quand les traiter? 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Wu, F; Khanal, K; Li, P. A rare case of adult-type anomalous origin of right coronary artery from pulmonary artery (ARCAPA). J Am Coll Cardiol. 2024, 83((13) Suppl, 4561. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Angelini, P. Novel imaging of coronary artery anomalies to assess their prevalence, the causes of clinical symptoms, and the risk of sudden cardiac death. Circ Cardiovasc Imaging. 2014, 7(4), 747–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Glushko, T; Seifert, R; Brown, F; Vigilance, D; Iriarte, B; Teytelboym, OM. Transseptal course of anomalous left main coronary artery originating from single right coronary orifice presenting as unstable angina. Radiol Case Rep. 2018, 13(3), 549–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McLarry, J; Ferencik, M; Shapiro, MD. Coronary artery anomalies: a pictorial review. Curr Cardiovasc Imaging Rep. 2015, 8(7), 23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Angelini, P; Trivellato, M; Donis, J; Leachman, RD. Myocardial bridges: a review. Prog Cardiovasc Dis. 1983, 26(1), 75–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sternheim, D; Power, DA; Samtani, R; Kini, A; Fuster, V; Sharma, S. Myocardial bridging: diagnosis, functional assessment, and management: JACC state-of-the-art review. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2021, 78(22), 2196–212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sternheim, D; Power, DA; Samtani, R; Kini, A; Fuster, V; Sharma, S. Myocardial bridging: diagnosis, functional assessment, and management. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2021, 78(22), 2196–212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Möhlenkamp, S; Hort, W; Ge, J; Erbel, R. Update on myocardial bridging. Circulation. 2002, 106(20), 2616–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Evbayekha, EO; Nwogwugwu, E; Olawoye, A; Bolaji, K; Adeosun, AA; Ajibowo, AO; et al. A comprehensive review of myocardial bridging: exploring diagnostic and treatment modalities. Cureus. 2023, 15(8), e43132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matta, AG; Yaacoub, N; Nader, V; Moussallem, N; Carrie, D; Roncalli, J. Coronary artery aneurysm: a review. World J Cardiol. 2021, 13(9), 446–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hartnell, GG; Parnell, BM; Pridie, RB. Coronary artery ectasia: its prevalence and clinical significance in 4993 patients. Br Heart J. 1985, 54(4), 392–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Hijji, M; El Sabbagh, A; El Hajj, S; AlKhouli, M; El Sabawi, B; Cabalka, A; et al. Coronary artery fistulas: indications, techniques, outcomes, and complications of transcatheter fistula closure. JACC Cardiovasc Interv. 2021, 14(13), 1393–406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stephens, EH; Jegatheeswaran, A; Brothers, JA; Ghobrial, J; Karamlou, T; Francois, CJ; et al. Anomalous aortic origin of a coronary artery. Ann Thorac Surg. 2024, 117(6), 1074–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mainwaring, RD; Ma, M; Maskatia, S; Petrossian, E; Reinhartz, O; Lee, J; et al. Outcomes of 230 patients undergoing surgical repair of anomalous aortic origin of a coronary artery. Ann Thorac Surg [Internet]. 19 Feb 2025, 0. Available online: https://www.annalsthoracicsurgery.org/article/S0003-4975(25)00119-5/fulltext.

- Schubert, SA; Kron, IL. Surgical unroofing for anomalous aortic origin of coronary arteries. Oper Tech Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2016, 21(3), 162–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carrel, T. Surgical treatment of anomalous aortic origin of coronary arteries: the reimplantation technique and its modifications. Oper Tech Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2016, 21(3), 178–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Padalino, MA; Franchetti, N; Hazekamp, M; Sojak, V; Carrel, T; Frigiola, A; et al. Surgery for anomalous aortic origin of coronary arteries: a multicentre study from the European Congenital Heart Surgeons Association. Eur J Cardiothorac Surg. 2019, 56(4), 696–703. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alzghari, T; Sandner, S; Di Franco, A; Harik, L; Perezgorvas-Olaria, R; Soletti, G; et al. Coronary artery bypass surgery to treat anomalous origin of coronary arteries in adults: a systematic review. Heart Lung Circ. 2023, 32(12), 1500–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Najm, HK; Karamlou, T; Ahmad, M; Hassan, S; Salam, Y; Majdalany, D; et al. Early outcomes of transconal repair of transseptal anomalous left coronary artery from right sinus. Ann Thorac Surg. 2021, 112(2), 595–602. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Said, SM; Cetta, F. Pulmonary root mobilization and modified Lecompte maneuver for transseptal course of the left main coronary artery. World J Pediatr Congenit Heart Surg. 2020, 11(6), 792–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bigler, MR; Kadner, A; Räber, L; Ashraf, A; Windecker, S; Siepe, M; et al. Therapeutic management of anomalous coronary arteries originating from the opposite sinus of Valsalva: current evidence, proposed approach, and the unknowing. J Am Heart Assoc. 2022, 11(20), e027098. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mery, CM; Beckerman, Z. What is the optimal surgical technique for anomalous aortic origin of a coronary artery? Semin Thorac Cardiovasc Surg Pediatr Card Surg Annu. Internet. 15 Feb 2025. Available online: https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S1092912625000092.

- Beyaz, MO; Coban, S; Ulukan, MO; Dogan, MS; Erol, C; Saritas, T; et al. Current strategies for the management of anomalous origin of coronary arteries from the pulmonary artery. Heart Surg Forum. 2021, 24(1), E065–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blickenstaff, EA; Smith, SD; Cetta, F; Connolly, HM; Majdalany, DS. Anomalous left coronary artery from the pulmonary artery: how to diagnose and treat. J Pers Med. 2023, 13(11), 1561. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guenther, TM; Sherazee, EA; Wisneski, AD; Gustafson, JD; Wozniak, CJ; Raff, GW. Anomalous origin of the right coronary artery from the pulmonary artery: a systematic review. Ann Thorac Surg. 2020, 110(3), 1063–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dodge-Khatami, A; Mavroudis, C; Backer, CL. Anomalous origin of the left coronary artery from the pulmonary artery: collective review of surgical therapy. Ann Thorac Surg. 2002, 74(3), 946–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saedi, S; Pouraliakbar, HR; Ghaderian, H; Saedi, T. Congenital atresia of left main coronary artery. Egypt Heart J. 2018, 70(4), 451–3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Musiani, A; Cernigliaro, C; Sansa, M; Maselli, D; De Gasperis, C. Left main coronary artery atresia: literature review and therapeutical considerations. Eur J Cardiothorac Surg. 1997, 11(3), 505–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hongo, Y; Tada, H; Ito, K; Yasumura, Y; Miyatake, K; Yamagishi, M. Augmentation of vessel squeezing at coronary–myocardial bridge by nitroglycerin: study by quantitative coronary angiography and intravascular ultrasound. Am Heart J. 1999, 138 2 Pt 1, 345–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hous, ND; Haine, S; Oortman, R; Laga, S. Alternative approach for the surgical treatment of left main coronary artery aneurysm. Ann Thorac Surg. 2019, 108(2), e91–3. [Google Scholar]

- Abou Sherif, S; Ozden Tok, O; Taşköylü, Ö; Goktekin, O; Kilic, ID. Coronary artery aneurysms: a review of the epidemiology, pathophysiology, diagnosis, and treatment. Front Cardiovasc Med [Internet] 2017, 4, 24. Available online: https://www.frontiersin.org/journals/cardiovascular-medicine/articles/10.3389/fcvm.2017.00024/full. [CrossRef]

- Kawsara, A; Núñez Gil, IJ; Alqahtani, F; Moreland, J; Rihal, CS; Alkhouli, M. Management of coronary artery aneurysms. JACC Cardiovasc Interv. 2018, 11(13), 1211–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buccheri, D; Chirco, PR; Geraci, S; Caramanno, G; Cortese, B. Coronary artery fistulae: anatomy, diagnosis and management strategies. Heart Lung Circ. 2018, 27(8), 940–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lau, WR; Lee, PT; Koh, CH. Coronary artery anomalies – state of the art review. Curr Probl Cardiol. 2023, 48(11), 101935. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- 2020 ESC Guidelines for the management of adult congenital heart disease [Internet]. Eur Heart J. 2021, 42(6), 563–645. Available online: https://academic.oup.com/eurheartj/article/42/6/563/5898606. [CrossRef]

- 2018 AHA/ACC Guideline for the management of adults with congenital heart disease: a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Clinical Practice Guidelines [Internet]. Circulation. 2019, 139(14), e698–800. Available online: https://www.ahajournals.org/doi/10.1161/CIR.0000000000000603.

- Naimo, PS; Fricke, TA; d’Udekem, Y; Cochrane, AD; Bullock, A; Robertson, T; et al. Surgical intervention for anomalous origin of left coronary artery from the pulmonary artery in children: a long-term follow-up. Ann Thorac Surg. 2016, 101(5), 1842–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Habets, J; van den Brink, R; Uijlings, R; Spijkerboer, A; Mali, W; Chamuleau, S; et al. Coronary artery assessment by multidetector computed tomography in patients with prosthetic heart valves. Eur Radiol. 2011, 22, 1278–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Figure 1.

Illustration of coronary arteries and their segments. The RCA is divided into proximal (1), middle (2), and distal (3) segments as it travels in the right atrioventricular groove. RCA gives its terminal branches, the posterior interventricular artery (also known as the posterior descending artery) (4) and the right posterolateral artery (5), near the "crux" of the heart on its inferior (diaphragmatic) surface. At the level of the LAD has also three segments, proximal (7), middle (8), and distal (9), while the LCX is normally divided into only two segments: proximal (12) and distal (13) Ao: aorta, PA: Pulmonary artery, LCA: left coronary artery, RCA: right coronary artery, LM: left main trunk, LCX: left circumflex, LAD: left anterior descending, Diagonal arteries (10-11), marginal arteries (14,15).

Figure 1.

Illustration of coronary arteries and their segments. The RCA is divided into proximal (1), middle (2), and distal (3) segments as it travels in the right atrioventricular groove. RCA gives its terminal branches, the posterior interventricular artery (also known as the posterior descending artery) (4) and the right posterolateral artery (5), near the "crux" of the heart on its inferior (diaphragmatic) surface. At the level of the LAD has also three segments, proximal (7), middle (8), and distal (9), while the LCX is normally divided into only two segments: proximal (12) and distal (13) Ao: aorta, PA: Pulmonary artery, LCA: left coronary artery, RCA: right coronary artery, LM: left main trunk, LCX: left circumflex, LAD: left anterior descending, Diagonal arteries (10-11), marginal arteries (14,15).

Figure 2.

(A) Three-dimensional representation of an absent left main trunk or congenital atresia of the left main trunk. (B) CCTA image showing an absent left main trunk.

Figure 2.

(A) Three-dimensional representation of an absent left main trunk or congenital atresia of the left main trunk. (B) CCTA image showing an absent left main trunk.

Figure 3.

Anomalous pulmonary origin of the coronary arteries (APOCA). Schematic image illustrating the left coronary artery arising directly from the pulmonary artery (ALCAPA, also known as Bland-White-Garland syndrome) and the right coronary artery arising from the pulmonary artery (ARCAPA). RCA: right coronary artery, LCA: Left coronary artery.

Figure 3.

Anomalous pulmonary origin of the coronary arteries (APOCA). Schematic image illustrating the left coronary artery arising directly from the pulmonary artery (ALCAPA, also known as Bland-White-Garland syndrome) and the right coronary artery arising from the pulmonary artery (ARCAPA). RCA: right coronary artery, LCA: Left coronary artery.

Figure 4.

Anomalous aortic origin of the coronary arteries (AAOCA). Schematic image illustrating the left coronary artery arising directly from the right coronary sinus(AAOLCA) and the right coronary artery directly from the left coronary sinus (AAORCA) . RCA: right coronary artery, LCA: Left coronary artery, anomalous origin of LCA from RSV(AAOLCA), anomalous origin of the RCA from LSV (AAORCA).

Figure 4.

Anomalous aortic origin of the coronary arteries (AAOCA). Schematic image illustrating the left coronary artery arising directly from the right coronary sinus(AAOLCA) and the right coronary artery directly from the left coronary sinus (AAORCA) . RCA: right coronary artery, LCA: Left coronary artery, anomalous origin of LCA from RSV(AAOLCA), anomalous origin of the RCA from LSV (AAORCA).

Figure 5.

Anomalies of aortic origin: (A) Three-dimensional projection of the right right coronary artery arising from the left sinus of Valsalva (B) CCTA image of an anomalous aortic origin of the right coronary artery from the left sinus of Valsalva (AAORCA).

Figure 5.

Anomalies of aortic origin: (A) Three-dimensional projection of the right right coronary artery arising from the left sinus of Valsalva (B) CCTA image of an anomalous aortic origin of the right coronary artery from the left sinus of Valsalva (AAORCA).

Figure 6.

The interarterial course especially with an intramural run (the coronary artery runs through the aortic wall, sharing the tunica media with the aorta), makes the artery prone to compression, particularly during systole.

Figure 6.

The interarterial course especially with an intramural run (the coronary artery runs through the aortic wall, sharing the tunica media with the aorta), makes the artery prone to compression, particularly during systole.

Figure 7.

Coronarography images demonstrating focal coronary artery aneuryms localised on RCA (A) and LAD (B). Coronary aneurysms are defined as a focal dilatation of a coronary exceeding 1.5 times the diameter of the adjacent normal segment but involving less than 50% of the vessel length.

Figure 7.

Coronarography images demonstrating focal coronary artery aneuryms localised on RCA (A) and LAD (B). Coronary aneurysms are defined as a focal dilatation of a coronary exceeding 1.5 times the diameter of the adjacent normal segment but involving less than 50% of the vessel length.

Figure 9.

Ostial translocation as a surgical technique for anomalous coronary artery origins. Ostial translocation is a surgical method used to correct anomalous origins of the coronary arteries related to abnormal aortic sinus origin. (A) Ostial translocation in AAORCA: relocation of the right coronary artery (RCA) from the left coronary sinus (LCS) to the right coronary sinus (RCS). (B) Ostial translocation in AAOLCA: relocation of the left coronary artery (LCA) from the right coronary sinus (RCS) to the left coronary sinus (LCS).

Figure 9.

Ostial translocation as a surgical technique for anomalous coronary artery origins. Ostial translocation is a surgical method used to correct anomalous origins of the coronary arteries related to abnormal aortic sinus origin. (A) Ostial translocation in AAORCA: relocation of the right coronary artery (RCA) from the left coronary sinus (LCS) to the right coronary sinus (RCS). (B) Ostial translocation in AAOLCA: relocation of the left coronary artery (LCA) from the right coronary sinus (RCS) to the left coronary sinus (LCS).

Figure 10.

The preferred technique for pulmonary origins of coronary arteries is direct reimplantation of the coronary artery in the correct sinus (coronary button technique). A circular portion of the PA around the anomalous coronary ostium (hence the name button) is taken and implanted in the correct site of the aorta. Direct implantation of LCA in ALCAPA (A) and ARCAPA (B).

Figure 10.

The preferred technique for pulmonary origins of coronary arteries is direct reimplantation of the coronary artery in the correct sinus (coronary button technique). A circular portion of the PA around the anomalous coronary ostium (hence the name button) is taken and implanted in the correct site of the aorta. Direct implantation of LCA in ALCAPA (A) and ARCAPA (B).

Table 1.

Key features of coronary anatomy described by Angelini et al. (2) for identifying a coronary artery as normal.

Table 1.

Key features of coronary anatomy described by Angelini et al. (2) for identifying a coronary artery as normal.

| Feature |

Range |

| No. of ostia |

2 to 4 |

| Location |

Right and left anterior sinuses (upper midsection) |

| Proximal orientation |

45° to 90° off the aortic wall |

| Proximal common stem or trunk |

Only left (LAD and Cx) |

| Proximal course |

Direct, from ostium to destination |

| Mid-course |

Extramural (subepicardial) |

| Branches |

Adequate for the dependent myocardium |

| Essential territories |

RCA (RV free wall), LAD (anteroseptal), OM (LV free wall) |

| Termination |

Capillary bed |

Table 2.

Anatomical classification of coronary artery anomalies proposed by Gentile et al. There are mainly three categories entitled as origin, course and termination anomalies (14).

Table 2.

Anatomical classification of coronary artery anomalies proposed by Gentile et al. There are mainly three categories entitled as origin, course and termination anomalies (14).

| Origin anomalies |

Anomalous pulmonary origin of the coronary arteries (APOCA) |

Anomalous origin of the left coronary artery from the pulmonary artery (ALCAPA) |

| Anomalous origin of the right coronary artery from the pulmonary artery (ARCAPA) |

| Anomalous origin of the circumflex artery from the pulmonary artery |

| Total anomalous origin of the coronary arteries from the pulmonary artery (TCAPA) |

Anomalous aortic origin of the coronary arteries (AAOCA)

|

Anomalous origin of the left main coronary artery from the right sinus of Valsalva |

| Anomalous origin of the right coronary artery from the left sinus of Valsalva (AAORCA) |

| Anomalous origin of the left anterior descending coronary artery from the right sinus of Valsalva (AAOLCA) |

| Anomalous origin of the circumflex artery from the right sinus of Valsalva |

| Anomalous origin of the left anterior descending artery from the right coronary artery |

| Anomalous origin of the circumflex artery from the right coronary artery |

| Single coronary artery |

| Inverted coronary arteries |

| Others |

| Congenital atresia of the left main trunk (absent left main trunk) |

| Course anomalies |

Myocardial (or coronary) bridge |

Symptomatic-asymptomatic |

| Coronary aneurysm |

Congenital or acquired |

| Termination anomalies |

Coronary arteriovenous fistula (CAF) |

Congenital or acquired |

| Coronary stenosis |

Congenital or acquired |

Table 3.

Clinical significance classification proposed by Rigatelli et al. There are four main categories going from benign to critical (15).

Table 3.

Clinical significance classification proposed by Rigatelli et al. There are four main categories going from benign to critical (15).

| Class |

Coronary Artery Anomaly |

| I. Benign |

- Ectopic origin of LCx from right sinus

- Separate origin of LCx and LAD

- Ectopic origin of LCx from the RCA

- Dual LAD types I-IV

- Myocardial bridge (score ≤ 5) |

II. Relevant

Related to myocardial ischemia

|

- Coronary artery fistula

- Single coronary artery R-L, I-II-III, A-P

- Ectopic origin of LCA from PA

- Atretic coronary artery

- Hypoplastic coronary artery |

III. Severe

Potentially related to sudden death

|

- Ectopic origin of LCA from the right sinus

- Ectopic origin of RCA from the left sinus

- Ectopic origin of RCA from the PA

- Single coronary artery R-L, I-II-III B

- Myocardial bridge (score ≥ 5) |

IV. Critical

Related to sudden death/myocardial ischemia and associated with superimposed CAD

|

- Class II and superimposed CAD

- Class III and superimposed CAD |

Table 4.

Myocardial bridges (MBs) score system: severity scoring for MBs, varying from 2 to 5, based on systolic narrowing and segment length, as described by Angelini and used in Rigatelli’s classification. (24).

Table 4.

Myocardial bridges (MBs) score system: severity scoring for MBs, varying from 2 to 5, based on systolic narrowing and segment length, as described by Angelini and used in Rigatelli’s classification. (24).

| Systolic Narrowing |

Rating |

| < 50% |

1 |

| 50 - 75% |

2 |

| > 75% |

3 |

| Stenotic Segments (Length) |

|

| < 1 cm |

1 |

| > 1 cm |

2 |

Table 5.

Comparison of international guidelines for the evaluation of CAAs(54,55) AHA/ACC: American Heart Association/American College of Cardiology, ESC: European Society of Cardiology, CCTA: coronary computed tomography angiography, CMR: cardiac magnetic resonance, LD: Limited Data, COR: Class of Recommendation and LOE: Level of Evidence.

Table 5.

Comparison of international guidelines for the evaluation of CAAs(54,55) AHA/ACC: American Heart Association/American College of Cardiology, ESC: European Society of Cardiology, CCTA: coronary computed tomography angiography, CMR: cardiac magnetic resonance, LD: Limited Data, COR: Class of Recommendation and LOE: Level of Evidence.

| 2018 AHA/ACC guideline for the management of adults with congenital heart disease |

2020 ESC guidelines for the management of adult congenital heart disease |

| Recommendations |

COR |

LOE |

Recommendations |

COR |

LOE |

Coronary angiography, using catheterization, CT, or CMR, is recommended for evaluation of anomalous coronary artery.

|

I |

C-LD |

Nonpharmacologic functional imaging (e.g., nuclear study, echocardiography, or CMR with physical stress) is recommended in patients with coronary anomalies to confirm/exclude myocardial ischemia. |

I |

C |

| Anatomic and physiologic evaluation should be performed in patients with anomalous aortic origin of the left coronary from the right sinus and/or right coronary from the left sinus. |

I |

C-LD |

|

Table 6.

Comparison of international guidelines for the surgical treatment of origin CAAs. The bold horizontal line separates recommendations concerning anomalies of aortic origin (above ) from those concerning pulmonary origins (below) (54,55). AHA/ACC: American Heart Association/American College of Cardiology, ESC: European Society of Cardiology, AAOC: anomalous aortic origin of the coronaries, AAOLCA: anomalous aortic origin of the left coronary artery, AAORCA: anomalous aortic origin of the right coronary artery, ALCAPA: anomalous left coronary from the pulmonary artery, ARCAPA: anomalous right coronary from the pulmonary artery, NR: Non Randomized, EO: Expert Opinion, LD: Limited Data, COR: Class of Recommendation and LOE: Level of Evidence.

Table 6.

Comparison of international guidelines for the surgical treatment of origin CAAs. The bold horizontal line separates recommendations concerning anomalies of aortic origin (above ) from those concerning pulmonary origins (below) (54,55). AHA/ACC: American Heart Association/American College of Cardiology, ESC: European Society of Cardiology, AAOC: anomalous aortic origin of the coronaries, AAOLCA: anomalous aortic origin of the left coronary artery, AAORCA: anomalous aortic origin of the right coronary artery, ALCAPA: anomalous left coronary from the pulmonary artery, ARCAPA: anomalous right coronary from the pulmonary artery, NR: Non Randomized, EO: Expert Opinion, LD: Limited Data, COR: Class of Recommendation and LOE: Level of Evidence.

| 2018 AHA/ACC guideline for the management of adults with congenital heart disease |

2020 ESC guidelines for the management of adult congenital heart disease |

| Recommendations |

COR |

LOE |

Recommendations |

COR |

LOE |

| Surgery is recommended for AAOCA from the left sinus or AAOCA from the right sinus for symptoms or diagnostic evidence consistent with coronary ischemia attributable to the anomalous coronary artery. |

I |

B- NR |

Surgery is recommended for AAOCA in patients with typical angina symptoms who present with evidence of stress-induced myocardial ischemia in a matching territory or high-risk anatomy. |

I |

C |

Surgery is reasonable for anomalous aortic origin of the left coronary artery from the right sinus in the absence of

symptoms or ischemia. |

IIa |

C- LD |

Surgery should be considered in asymptomatic patients with AAOCA (right or left) and evidence of myocardial ischemia. |

IIa |

C |

Surgery for AAOCA is reasonable in the

setting of ventricular arrhythmias. |

IIa |

C- EO |

Surgery should be considered in asymptomatic patients with AAOLCA and no evidence of myocardial ischemia but a high-risk anatomy. |

IIa |

C |

| Surgery or continued observation may be reasonable for asymptomatic patients with an anomalous left coronary artery arising from the right sinus or right coronary artery arising from the left sinus without ischemia or anatomic or physiological evaluation suggesting potential for compromise of coronary perfusion (eg, intramural course, fish-mouth-shaped orifice, acute angle). |

IIb |

B- NR |

Surgery may be considered for symptomatic patients with AAOCA even if there is no evidence of myocardial ischaemia or high-risk anatomy. |

IIb |

C |

| |

|

|

Surgery may be considered for asymptomatic patients with AAOLCA without myocardial ischemia and without high-risk anatomy when they present at young age (<35 years). |

IIb |

C |

| |

|

|

Surgery is not recommended for AAORCA in asymptomatic patients without myocardial ischemia and without high-risk anatomy. |

III |

C |

| Surgery is recommended for ALCAPA. |

I |

B- NR |

Surgery is recommended for ALCAPA. |

I |

C |

| In a symptomatic adult with anomalous right coronary artery from the PA with symptoms attributed to the anomalous coronary, surgery is recommended. |

I |

C-EO |

Surgery is recommended in patients with ARCAPA and symptoms attributable to anomalous coronary artery. |

I |

C |

Surgery for anomalous right coronary

artery from the PA is reasonable in an asymptomatic adult with ventricular dysfunction or with myocardial ischemia

attributed to anomalous right coronary artery from the PA. |

IIa |

C-EO |

Surgery should be considered for ARCAPA in asymptomatic patients with ventricular dysfunction, or myocardial ischemia attributable to coronary anomaly. |

IIa |

C |

Table 7.

Decision tree for selection of recommended and/or suggested treatment modalities in patients with coronary artery anomalies. A) Origin anomalies. B) Course anomalies. C) Termination anomalies. AAOCA: Anomalous aortic origin of the coronary arteries, ALCAPA: Anomalous left coronary artery from the pulmonary artery, APOCA: Anomalous pulmonary origin of the coronary arteries, ARCAPA: Anomalous right coronary artery from the pulmonary artery, CABG: Coronary artery bypass graft, PCI: Percutaneous coronary intervention.

Table 7.

Decision tree for selection of recommended and/or suggested treatment modalities in patients with coronary artery anomalies. A) Origin anomalies. B) Course anomalies. C) Termination anomalies. AAOCA: Anomalous aortic origin of the coronary arteries, ALCAPA: Anomalous left coronary artery from the pulmonary artery, APOCA: Anomalous pulmonary origin of the coronary arteries, ARCAPA: Anomalous right coronary artery from the pulmonary artery, CABG: Coronary artery bypass graft, PCI: Percutaneous coronary intervention.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |