1. Introduction

The emergence and spread of antimicrobial-resistant bacteria poses a serious threat to global health. A particularly concerning mechanism behind this resistance is the spread of antimicrobial resistance genes (ARGs) via plasmids, one of the mobile genetic elements (MGEs), that can transfer between different bacterial species through conjugative transfer [

1]. Plasmids carrying ARGs, known as resistance plasmids (R plasmids), are classified into incompatibility (Inc) groups based on the similarity of their replication systems. Many well-known R plasmids belong to groups such as IncC, IncF, IncN, IncL, among others, and IncC and IncN plasmids are capable of horizontal transfer across a wide range of bacterial hosts [

2,

3]. These plasmids play a central role in the dissemination of resistance traits not only in clinical settings but increasingly in the environment [

1].

Recent studies have reported the presence of multidrug-resistant bacteria and ARGs in wastewater plants and urban rivers [

4,

5,

6,

7], as well as on agricultural products such as vegetables [

8,

9]. These findings suggest that ARG transfer is occurring in environments closely linked to daily human life. R plasmids originating from human clinical isolates have been well studied. However, such investigations in natural environments are still limited. Little is known about whether R plasmids are capable of propagating in environmental bacterial communities, or what kinds of bacteria are involved in such exchanges. Moreover, it is plausible that novel plasmids, distinct from those characterized in clinical strains, exist in natural environments and contribute to the emergence of resistance. It is therefore important to understand the linkage between R plasmids in clinical and natural environments.

In our previous study, we captured 167 transconjugants from the Tama River using a culture-dependent mating approach, revealing that diverse plasmids circulate in this urban river environment [

10]. However, the genetic structures, MGEs, and antimicrobial resistance phenotypes of these plasmids remained largely unexplored. In the present study, we focused on 11 plasmids from this collection that were found to carry ARGs. These plasmids belonged to several incompatibility groups, IncN, IncU, IncQ2, IncC, and IncP, representing key vectors known to mediate multidrug resistance (MDR) in both clinical and environmental settings. We performed comprehensive genomic analyses of their backbone regions, accessory resistance regions, and associated MGEs, including integrons, insertion elements (ISs), transposons, and Tn

3-derived inverted repeat miniature elements (TIMEs) [

11]. We additionally conducted conjugation assays and antimicrobial susceptibility testing to assess their transmissibility and resistance phenotypes. By comparing the plasmids with related sequences reported worldwide, we aimed to clarify the evolutionary connections between environmental and clinical plasmid pools and to better understand the role of urban rivers as reservoirs and dissemination points of MDR plasmids.

2. Results and Discussion

2.1. Various Plasmids Carrying ARGs Were Captured from the Tama River

Our previous exogenous plasmid captures using microbial communities collected from six sampling sites along the Tama River (Tama1 to Tama6,

Figure 1) yielded 167 transconjugants through biparental matings and triparental matings, most of which were previously analyzed (

Table A1) [

10]. In principle, biparental matings allow the capture of plasmids that both confer the targeted resistance to the hosts and are self-transmissible between different cells. In contrast, triparental matings enable the acquisition of self-transmissible plasmids that do not carry the marker resistance genes but can mobilize non-self-transmissible plasmids as helper plasmids. Here, we specifically examine 11 plasmids carrying ARGs that were captured from midstream or downstream sites of the Tama River (Tama4, Tama5, and Tama6,

Figure 1 and

Table 1). There were six IncP plasmids including IncPβ, IncPγ, IncPε, IncPι and IncPκ subgroups, one PromA plasmid, one IncN plasmid, and one IncC plasmid (

Table 1). One plasmid was estimated to be classified both under the IncU and IncQ groups (a multi-replicon). These plasmids were found to harbor resistance genes against aminoglycosides, β-lactams, tetracyclines, mercury, and other agents. Hosts carrying these ARG-bearing plasmids exhibited resistance to the tested antibiotics, including tetracycline (Tc), gentamicin (Gm), ampicillin (Ap), kanamycin (Km), chloramphenicol (Cm), streptomycin (Sm), and erythromycin (Em) as summarized in

Table 2.

In the following sections, we present detailed nucleotide sequence–level analyses and comparative genomic analyses of each individual plasmid and the mobile genetic elements associated with ARGs on these plasmids.

2.2. Multi-Replicon Plasmid pMNBM065-2

Plasmid pMNBM065-2 was captured from the downstream (Tama5) along with pMNBM065-1 (PromAγ) through biparental matings (

Table 1). pMNBM065-2 was shown to be a multi-replicon plasmid possessing genes encoding replication initiation protein (RIP) of both IncU and IncQ2γ (

Figure 2A). A comparison of the nucleotide sequences of pMNBM065-2 with pRA3, an archetype plasmid of IncU group [

12,

13] and pRAS3-3759, a member of IncQ2γ plasmid [

14,

15,

16], showed that pMNBM065-2 contained one region homologous to maintenance and accessory regions of pRA3 (IncU) and another region highly similar to almost entire sequence of pRAS3-3759 (IncQ2γ) (

Figure 2A). This plasmid additionally had six tandem 5,134-bp repeat regions, containing resistance genes for sulfonamide (

sul1) and chloramphenicol (

catA) and a putative gene encoding a transposase of IS

CR1, a member of IS

91 family (

Table 1,

Figure 2A).

IS

CR1 elements encode a transposase that catalyzes transposition through a rolling-circle mechanism [

17,

18,

19]. They possess two imperfect terminal 8-bp inverted repeats,

terIS (the left end) and

oriIS (the right end), each associated with characteristic dyad-symmetry sequences that serve as recognition sites for the transposase [

20] (

Figure 2B(i)). The

oriIS region, located downstream of the transposase gene, is essential for initiating rolling-circle replication during transposition [

18] (

Figure 2B(i)). A notable feature of the IS

CR1 element is that a single copy of the element is sufficient to mobilize adjacent DNA sequences when the ~100-bp

oriIS region is present [

18] (

Figure 2B(ii)). This property enables one-ended transposition, in which transposition proceeds from the

oriIS end without requiring a second IS end (

terIS) [

19] (

Figure 2B(ii)).

Previous studies have shown that IS

CR1 elements are almost exclusively associated with class 1 integrons [

21]. A genetic model has been proposed in which the IS

CR1 element is fused to the class 1 integron. The 3’-conserved segment (3’-CS) of the integron is formed by the fusion of the

sul1 and

qacEΔ1 genes [

21]. In this structure, fusion of IS

CR1 with the 3’-CS results in deletion of the

terIS site, and the start codon of the IS

CR1 ORF is located 404-bp downstream of the stop codon of the

sul1 gene [

20]. In addition, the gene

orf5, which is typically found downstream of

qacEΔ1-

sul1, is absent [

20]. The fusion of IS

CR1 to the 3’-CS, together with the absence of

terIS, allows the IS

CR1 element to undergo rolling-circle replication encompassing all or part of the class 1 integron. This process enables mobilization of the class 1 integron [

20]. Mobilized class 1 integrons can subsequently acquire non-cassette resistance genes, and recombination with the 3’-CS of another class 1 integron leads to the formation of a complex class 1 integron [

20] (see

Figure 2C as follows).

In pMNBM065-2, we identified two sequence features relevant to ISCR-1 mediated rearrangements. First, a highly conserved 22-bp sequence (5’-GTGGTTTATACTTCCTATACCC-3’) [

21,

22] was detected at the right end of the IS

CR1 element, which is consistent with an

oriIS-like site (

Figure 2C). Second, the stop codon of

sul1 and the start codon of the IS

CR1 ORF were separated by 404-bp (

Figure 2C), a spacing previously reported for IS

CR1 elements fused to the 3’-CS of class 1 integrons. These observations support a plausible scenario in which IS

CR1 element, together with

catA and

qacEΔ1-

sul1, generated a circular donor DNA intermediate via one-ended transposition, followed by recombination into the 3’-CS of the class 1 integron on pMNBM065-2 (

Figure 2C(i)). If this scenario occurred, the architecture shown in

Figure 2C(i) would be expected, namely a complex class 1 integron containing aminoglycoside resistance genes [

aac(6’)-IIc and

aadA1] plus the IS

CR1-associated region (

qacEΔ1-

sul1-IS

CR1-

catA) with partial copies of

qacEΔ1 and

sul1 (

Figure 2C(ii)). Reiteration of this recombination process could account for the presence of six tandem repeats of the region containing the IS

CR1 element,

catA, and partial

qacEΔ1-

sul1 sequences (

Figure 2C(iii)). However, subsequent sequencing after cultivation indicated that this region was detected in only one or two copies, suggesting this repeat region may be unstable or subject to rearrangement under the cultivation condition used.

For the minimum inhibitory concentration (MIC) analysis, the plasmid pMNBM065-2 containing two copies of the repeat region was used. The MIC of the parental

E. coli MG1655RGFP, which carries a single chromosomal

catA gene inserted with GFP gene by a mini-transposon [

23], against chloramphenicol (Cm), determined by broth microdilution, was 250 µg/mL, while that of

E. coli MG1655RGFP harboring pMNBM065-1 and pMNBM065-2 was 2000 µg/mL, representing an eightfold increase. It should be noted that no known ARGs were detected on pMNBM065-1. It also carried tetracycline (

tetRC) and conferred resistance to its host (

Table 2).

2.3. Mobilization of pMNBM065-2

Plasmid pMNBM065-2 possessed partial gene sets for conjugative transfer found in IncU plasmids, namely

orf30-

top genes [

13], but the

top gene was disrupted by the insertion of IS

Aeme19, and additional putative relaxosome related genes (MOB

P family gene) and

oriT region (137-bp) found in IncQ2γ plasmids (

Figure 2A). The co-resident plasmid pMNBM065-1 (PromAγ) is self-transmissible, which has MOB

P and MPF

T family genes. To assess whether the pMNBM065-2 could be mobilized by pMNBM065-1, filter mating assays with

E. coli JM109(pUC19) were conducted. As a result, both plasmids were transferred to the recipient with a transfer frequency of 1.7×10

-2 per donor. Although IncU and IncQ2 plasmids were mainly isolated from

Enterobacteriaceae, the transfer range of PromAγ plasmid is known to be broad [

24]. Therefore, pMNBM065-2 is likely to transfer among different bacterial families beyond its native host range, thereby conferring antimicrobial resistance and enhancing the survival of recipient bacteria in the Tama River.

2.4. IncN Plasmid pMNBM072

Plasmid pMNBM072 was captured from the downstream (Tama5) through biparental matings and classified under the IncN plasmid group (

Table 1). IncN plasmids were detected in clinical and environmental sources worldwide, and their nucleotide sequences were highly conserved with the IncN archetype plasmid pR46 [

25] (

Figure 3A). Two accessory regions were identified, each probably inserted at specific regions, between the replication and conjugative transfer region (accessory region I) or downstream of relaxase gene (accessory region II) [

6]. pMNBM072 possessed a complex class 1 integron with gene cassettes

aac(6’)-Ib-cr,

arr-3,

dfrA27,

aadA16,

qacEΔ1,

sul1, IS

CR1 element,

qnrB6,

qacEΔ1 and

sul1 in the accessory region I (

Figure 3B). Among them, a single copy of

qacEΔ1-

sul1, IS

CR1 element and

qnrB6 were likely inserted through transposition and recombination mediated by IS

CR1 element fused to the 3’-CS of the class 1 integron. In addition, IS

6100 element was located within the same region and 25-bp inverted repeats (IRs) (5’-TGTCRTTTTCAGAAGACGRCTGCAC-3’) and 5-bp direct repeats (DR) (5’-CTGTT-3’) were detected outside of the IS

6100 element and the class 1 integron. Consistent with the presence of these resistance genes, pMNBM072 conferred resistance to kanamycin, streptomycin and tetracycline on its host (

Table 2).

Moreover, pMNBM072 and the IncN plasmids isolated from the United Kingdom and South Korea were highly similar in both their backbones and accessory genes (

Figure 3AB). Additionally, pMNBM072 carried resistance genes for tetracycline (

tetAR) in the accessory region II and conferred resistance on its host (

Table 2). A region containing

tetAR was flanked by 244-bp Tn

3-derived inverted repeat miniature elements (244-bp TIMEs) and 5-bp DR (5’-AGCAA-3’), which is a short and non-autonomous transposable element characterized by terminal inverted repeats but lacking the capacity to encode a transposase (

Figure 3C) [

11,

26]. This region is likely mobilized by transposases provided in trans, thereby facilitating the dissemination of resistance genes.

2.5. IncC Plasmid pMNBL073

Plasmid pMNBL073 was captured from midstream site (Tama4) through biparental matings and estimated to be classified under the IncC group based on PCR analyses (

Table 1) [

10]. Based on the full-length nucleotide sequences of RIP genes, pMNBL073 was a member of the IncC group. IncC plasmids have been isolated from a wide range of sources, including humans, animals, and natural environments. Their backbone sequences are highly similar (

Figure 4A), and accessory regions are predominantly inserted at two specific regions ‘hotspots’ [

27]. In pMNBL073 and its homologous plasmids, an accessory region was also identified upstream of

parA gene, one of the specific insertion regions (

Figure 4A) [

27]. A comparison of the nucleotide sequences of this accessory region showed that the antimicrobial resistance genes, transposons and IS present were diverse and complex (

Figure 4A). The other ‘hotspot’ is upstream of the

rhs gene. pMNBL073 carried genes conferring resistance to aminoglycosides [

aadA2,

aac(3)-IVa,

aph(4)-Ia and

strAB], sulfonamide (

sul1 and

sul2), trimethoprim (

dfrA23), chloramphenicol (

floR) and tetracycline (

tetAR) (

Figure 4B). Among these resistance genes,

aadA2,

qacEΔ1 and

sul1 are included in a class 1 integron (

Figure 4B). pMNBL073 conferred resistance to gentamicin, chloramphenicol, and tetracycline on its host (

Table 2).

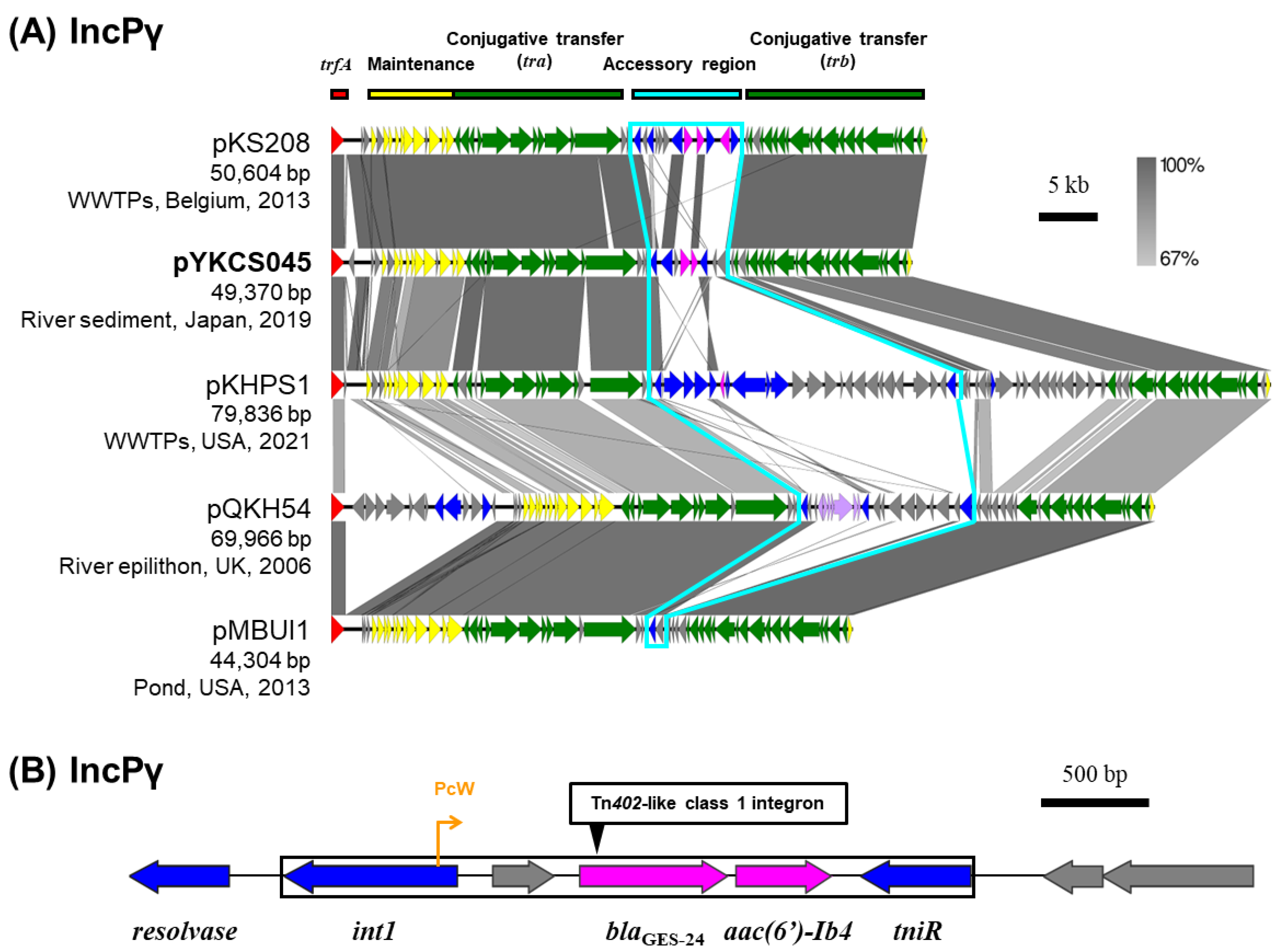

2.6. IncP Plasmids

Among the six IncP plasmids captured from the Tama River, plasmid pYKCS045 (IncPγ), pMNBL056 (IncPε), and pYKBL037 (IncPι) carried class 1 integrons containing multiple ARGs (

Table 1) [

10]. Regarding pYKCS045 captured from downstream site of the Tama River (Tama5) through triparental matings, it was predicted to be IncPγ plasmid. Only four other IncPγ plasmids are registered in the plasmid database PLSDB [

28,

29,

30], and they were isolated from natural environments such as rivers, wastewater treatment plants (WWTPs) and pond [

31,

32]. A comparison of the nucleotide sequences of IncPγ plasmids showed that their core genes for replication, maintenance, and transfer were highly conserved (

Figure 5A). The accessory regions including ARGs were inserted into between

tra gene sets and

trb gene sets. Plasmid pYKCS045 carried the resistance genes for carbapenems (

blaGES-24) and aminoglycosides [

aac(6’)-Ib4] within a Tn

402-like class 1 integron (

Figure 5B) with 25-bp IRs (5’-TGTCRTTTTCAGAAGACGRYTGCAC-3’) and 5-bp DRs (5’-CCTAT-3’). By broth microdilution, the MIC of

Metapseudomonas resinovorans CA10dm4RGFP harboring this plasmid against meropenem was 32 µg/mL.

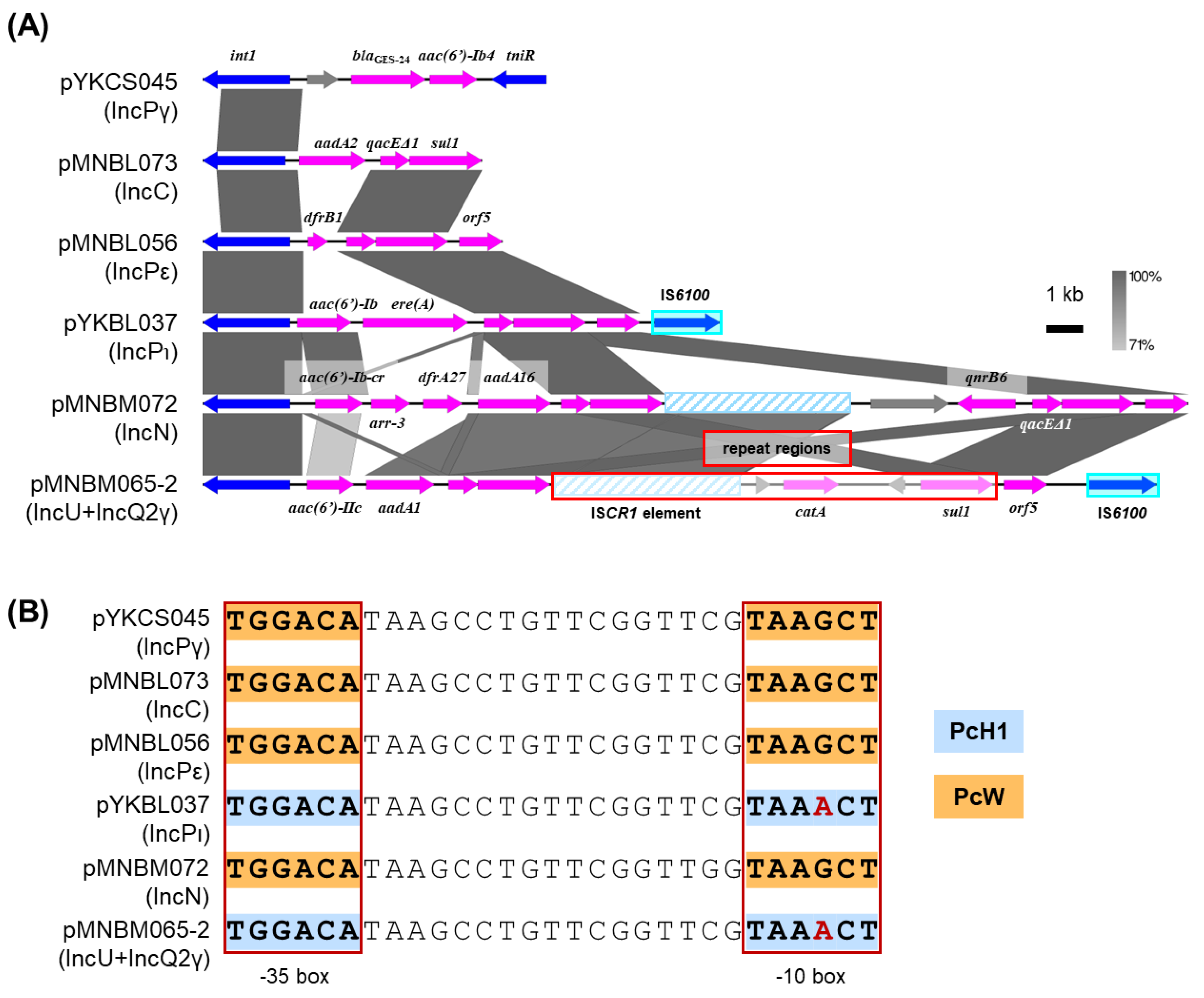

2.7. Class 1 Integrons

Regardless of the Inc groups, class 1 integrons were found in six plasmids including pYKCS045 (IncPγ), pMNBL056 (IncPε), pYKBL037 (IncPι), pMNBM065-2 (IncU and IncQ2γ), pMNBM072 (IncN) and pMNBL073 (IncC). Plasmid pYKCS045 had Tn

402-like class 1 integron, which contained a part of transposase genes,

tniR,

blaGES-24 and

aac(6’)-Ib4 (

Figure 6A). Plasmids pMNBL056 and pYKBL037 had a class 1 integron 3’ conserved segment (3’-CS) with three well-conserved genes,

qacEΔ1-

sul1-

orf5, while pMNBL073 contained a similar integron with

aadA2 gene and 3’-CS, lacked an

orf5 gene (

Figure 6A) [

33]. In addition, the integron of pMNBL056 contained the gene cassette

dfrB1 encoding for trimethoprim resistance, whereas that of pYKBL037 contained

aac(6’)-Ib and

ere(A) encoding for erythromycin resistance (

Figure 6A). pMNBM065-2 and pMNBM072 had a complex class 1 integron generated by an IS

CR1 element. These class 1 integrons contained the gene cassettes

aac(6’)-IIc and

aadA1 in pMNBM065-2, and

aac(6’)-Ib-cr,

arr-3,

dfrA27 and

aadA16 in pMNBM072. In contrast,

catA and

qnrB6 were likely acquired through the recombination involving the IS

CR1 element-class 1 integron 3’-CS fusion variants, respectively (

Figure 6A). The four variants of the class 1 integron gene cassette promoter located in

intI1 gene (Pc), PcW, PcH1, PcH2 and PcS, are known to differ in transcriptional strengths. PcW (ancestral and the weakest form), PcS (the strongest form), PcH1 (stronger than PcW but weaker than PcH2) and PcH2 (between PcS and PcH1) [

33,

34,

35]. Two kinds of promoters, PcW and PcH1, of the class 1 integrons were found in the captured plasmids (

Figure 6B). The promoters in pMNBM065-2 and pYKBL037 exhibited higher predicted strength than those in pYKCS045, pMNBM072, pMNBL073 and pMNBL056 (

Figure 6B).

Collectively, our findings highlight two major patterns among the captured plasmids. First, IncN and IncC plasmids exhibited high structural similarity, including conserved accessory resistance regions, to clinically derived plasmids reported from geographically distant regions, indicating that clinically associated plasmids are also present in the urban river environment. Second, plasmids such as the multi-replicon IncU+IncQ2γ plasmid and several IncP plasmids displayed accessory-region architectures characteristic of environmental plasmids, suggesting that urban rivers can also serve as sites where novel MDR plasmids may emerge. These results support the idea that urban rivers, such as the Tama River, function as ecological hubs where clinically derived and environmentally adapted resistance plasmids coexist, interact, and potentially disseminate.

Importantly, the Tama River flows through the Tokyo metropolitan area, one of the world’s largest and most densely populated megacities. This urban setting concentrates inputs from hospitals, households, industries, and wastewater systems, creating a unique ecological interface where human-associated, clinical, and environmental bacteria frequently intersect. The coexistence of both clinically related and environmentally distinct MDR plasmids within such an urban river highlights its potential role as a critical conduit for the exchange and dissemination of antimicrobial resistance. Our findings therefore emphasize the need for systematic monitoring of riverine environments within megacities, where intense human activity and environmental microbial communities converge, forming hotspots that may accelerate the evolution and spread of resistance plasmids.

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Bacterial Strains, Plasmids, and Culture Conditions

Escherichia coli and

Metapseudomonas resinovorans strains were cultivated in Luria broth (LB) [

36] at 30°C or 37°C. R2A plates containing 1.5% agar were used for filter matings. Ampicillin (Ap, 50 μg/mL), kanamycin (Km, 30 μg/mL for plasmid capture and 50 μg/mL for the other experiments), gentamicin (Gm, 30 μg/mL), and rifampicin (Rif, 30 μg/mL for plasmid capture and 50 μg/mL for the others) were added to the medium. Cycloheximide (100 μg/mL) was added to prevent fungal growth. For plate cultures, LB was solidified using 1.5% agar (wt/vol).

3.2. Collection of Environmental Samples

River sediment samples were collected from six sites located in the upstream, mid-stream and downstream regions of the Tama River in Tokyo, Japan in 2019 and 2020 (

Figure 1). The sampling sites were as follows: Tama1 (35.803872 N 139.194108 E), Tama2 (35.776822 N 139.287567 E), Tama3 (35.695053 N 139.363358 E), Tama4 (35.652894 N 139.504669 E), Tama5 (35.601667 N 139.624847 E), and Tama6 (35.544467 N 139.725906 E).

3.3. Resistance Testing

Resistance testing for plasmids pMNDW109 and pMNDX110 was performed. For this testing, ampicillin (Ap, 50 µg/mL), gentamicin (Gm, 30 µg/mL), and tetracycline (Tc, 12.5 µg/mL) were added to LB. Resistance testing for the other plasmids had already been performed in our previous report [

10]. For pYKCS045, the determination of minimum inhibitory concentrations (MIC) was additionally performed using the broth microdilution method with Mueller Hinton Broth, following the Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute CLSI M07 protocol [

37].

3.4. Plasmid Sequencing and Annotation

The nucleotide sequences of pMNDW109 and pMNDX110 were determined using MiSeq platform (Illumina, San Diego, CA). 151-bp paired-end libraries were prepared using the Nextera XT DNA Library Preparation Kit (Illumina). Assembly of the sequencing reads was performed using SPAdes v. 3.14.1 [

38] with default parameters. In addition, PCR was performed to confirm the connection between sequence fragments. These plasmids were annotated using DFAST (

https://dfast.ddbj.nig.ac.jp/) [

39] and their accession numbers in DDBJ are LC895901.1 and LC895902.1 (listed in

Table 1). Other plasmids were previously determined and annotated [

10], their accession numbers deposited in DDBJ are in

Table 1. ARGs were detected using ResFinder database (

https://bitbucket.org/genomicepidemiology/resfinder_db/src/master/). Plasmid maps were visualized using Easyfig v.2.2.5 [

40]. The structures of plasmids were compared using Easyfig.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, M.S.; methodology, M.Y., K,N., R.M., H.D., and T.S.; investigation, R.Y., M.T., S.S and K.N; data curation, M.Y.; formal analysis, M.Y.; writing—original draft preparation, M.Y., M.S.; writing—review and editing, M.Y., M.T., R.M., H.D. H.F., K.K, and M.S.; visualization, M.Y.; supervision, M.S.; project administration, M.S. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work was supported by Tokyu Foundation (2019-110), JSPS KAKENHI (JP19H05686, JP19H02869, JP20KK0128, JP23H02124 to M. Shintani, JP24K23121, JP25K18160 to M. Tokuda); and Grant-in-Aid for JSPS Research Fellow (grant JP22J12723 to M. Tokuda) from the Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, Science, and Technology (MEXT), Japan; grants (JP21wm0325022, JP21wm0225008, JP23wm0225029 to M. Shintani) from Japan Agency for Medical Research and Development (AMED), a grant from the Asahi Glass Foundation to M. Shintani; Institute for Fermentation, Osaka (L-2023-1-002) to M. Shintani; Toyota Physical and Chemical Research Institute to M. Shintani; Research Institute of Green Science and Technology Fund for Research Project Support, Shizuoka University, Grant/Award Number: 2023-RIGST-23104 and 2024-RIGST-24202 to M. Shintani; and a grant from the Consortium for the Exploration of Microbial Functions of Ohsumi Frontier Science Foundation, Japan to M. Shintani.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The complete nucleotide sequences of plasmids analyzed in this study have been deposited in the DDBJ database under the accession numbers LC895901.1 and LC895902.1.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| ARG |

Antimicrobial resistance gene |

| Cm |

Chloramphenicol |

| CS |

Conserved segment |

| DDBJ |

DNA Data Bank of Japan |

| ENA |

European Nucleotide Archive |

| GFP |

Green fluorescent protein |

| IS |

Insertion sequence |

| ISCR |

Insertion sequence common region |

| kb |

Kilobase(s) |

| MGE |

Mobile genetic element |

| MIC |

Minimum inhibitory concentration |

| oriIS |

Origin of insertion sequence replication |

| PCR |

Polymerase chain reaction |

| PLSDB |

Plasmid database |

| Rep |

Replication protein |

| RND |

Resistance–nodulation–cell division |

| Tn |

Transposon |

Appendix A

Table A1.

The plasmids captured from the Tama River, as described previously [

10].

Table A1.

The plasmids captured from the Tama River, as described previously [

10].

| Sample |

Recipients |

No. of isolates |

IncP |

PromA |

pSN1216-29 |

IncA or IncC |

IncL or IncM |

IncN |

IncW |

PCR-negative |

| Tama1 |

M. resinovorans |

20 |

0 |

4 |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

16 |

| E. coli |

0 |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

| Tama2 |

M. resinovorans |

20 |

0 |

1 |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

19 |

| E. coli |

0 |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

| Tama3 |

M. resinovorans |

9 |

0 |

0 |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

9 |

| E. coli |

0 |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

| Tama4 |

M. resinovorans |

20 |

0 |

0 |

12 |

- |

- |

- |

- |

8 |

| E. coli |

4 |

|

0 |

0 |

2 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

1 |

| Tama5 |

M. resinovorans |

40 |

1 |

6 |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

33 |

| E. coli |

17 |

7 |

1 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

2 |

0 |

8 |

| Tama6 |

M. resinovorans |

36 |

3 |

0 |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

34 |

| E. coli |

1 |

1 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

- |

0 |

| total |

167 |

16 |

24 |

12 |

2 |

0 |

2 |

0 |

127 |

References

- Castañeda-Barba, S.; Top, E.M.; Stalder, T. Plasmids, a Molecular Cornerstone of Antimicrobial Resistance in the One Health Era. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 2024, 22, 18–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flach, C.-F.; Johnning, A.; Nilsson, I.; Smalla, K.; Kristiansson, E.; Larsson, D.G.J. Isolation of Novel IncA/C and IncN Fluoroquinolone Resistance Plasmids from an Antibiotic-Polluted Lake. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 2015, 70, 2709–2717. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, Z.; Wang, Q.; Pinilla-Redondo, R.; Madsen, J.S.; Clasen, K.A.D.; Ananbeh, H.; Olesen, A.K.; Gong, Z.; Yang, N.; Dechesne, A.; et al. Horizontal Transmission of a Multidrug-Resistant IncN Plasmid Isolated from Urban Wastewater. Ecotoxicol. Environ. Saf. 2024, 271, 115971. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, T.N.; Kasuga, I.; Liu, M.; Katayama, H. Occurrence of Antibiotic Resistance Genes as Emerging Contaminants in Watersheds of Tama River and Lake Kasumigaura in Japan. IOP Conf. Ser. Earth Environ. Sci. 2019, 266, 012003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shintani, M.; Vestergaard, G.; Milaković, M.; Kublik, S.; Smalla, K.; Schloter, M.; Udiković-Kolić, N. Integrons, Transposons and IS Elements Promote Diversification of Multidrug Resistance Plasmids and Adaptation of Their Hosts to Antibiotic Pollutants from Pharmaceutical Companies. Environ. Microbiol. 2023, 25, 3035–3051. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hauschild, K.; Suzuki, M.; Wolters, B.; Tokuda, M.; Yamazaki, R.; Masumoto, M.; Moriuchi, R.; Dohra, H.; Bunk, B.; Spröer, C.; et al. The Transferable Resistome of Biosolids-Plasmid Sequencing Reveals Carriage of Clinically Relevant Antibiotic Resistance Genes. mBio 2025, 16, e0206825. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wolters, B.; Hauschild, K.; Blau, K.; Mulder, I.; Heyde, B.J.; Sørensen, S.J.; Siemens, J.; Jechalke, S.; Smalla, K.; Nesme, J. Biosolids for Safe Land Application: Does Wastewater Treatment Plant Size Matters When Considering Antibiotics, Pollutants, Microbiome, Mobile Genetic Elements and Associated Resistance Genes? Environ. Microbiol. 2022, 24, 1573–1589. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Blau, K.; Bettermann, A.; Jechalke, S.; Fornefeld, E.; Vanrobaeys, Y.; Stalder, T.; Top, E.M.; Smalla, K. The Transferable Resistome of Produce. mBio 2018, 9, e01300-18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hölzel, C.S.; Tetens, J.L.; Schwaiger, K. Unraveling the Role of Vegetables in Spreading Antimicrobial-Resistant Bacteria: A Need for Quantitative Risk Assessment. Foodborne Pathog. Dis. 2018, 15, 671–688. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hayakawa, M.; Tokuda, M.; Kaneko, K.; Nakamichi, K.; Yamamoto, Y.; Kamijo, T.; Umeki, H.; Chiba, R.; Yamada, R.; Mori, M.; et al. Hitherto-Unnoticed Self-Transmissible Plasmids Widely Distributed among Different Environments in Japan. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2022, 88, e0111422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Szuplewska, M.; Ludwiczak, M.; Lyzwa, K.; Czarnecki, J.; Bartosik, D. Mobility and Generation of Mosaic Non-Autonomous Transposons by Tn3-Derived Inverted-Repeat Miniature Elements (TIMEs). PLoS One 2014, 9, e105010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kulinska, A.; Czeredys, M.; Hayes, F.; Jagura-Burdzy, G. Genomic and Functional Characterization of the Modular Broad-Host-Range RA3 Plasmid, the Archetype of the IncU Group. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2008, 74, 4119–4132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lewicka, E.; Dolowy, P.; Godziszewska, J.; Litwin, E.; Ludwiczak, M.; Jagura-Burdzy, G. Transcriptional Organization of the Stability Module of Broad-Host-Range Plasmid RA3, from the IncU Group. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2020, 86, e00847-20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- L’Abée-Lund, T.M.; Sørum, H. A Global Non-Conjugative Tet C Plasmid, pRAS3, from Aeromonas salmonicida. Plasmid 2002, 47, 172–181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loftie-Eaton, W.; Rawlings, D.E. Comparative Biology of Two Natural Variants of the IncQ-2 Family Plasmids, pRAS3.1 and pRAS3.2. J. Bacteriol. 2009, 191, 6436–6446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fournier, K.C.; Paquet, V.E.; Attéré, S.A.; Farley, J.; Marquis, H.; Gantelet, H.; Ravaille, C.; Vincent, A.T.; Charette, S.J. Expansion of the pRAS3 Plasmid Family in Aeromonas salmonicida Subsp. salmonicida and Growing Evidence of Interspecies Connections for These Plasmids. Antibiotics (Basel) 2022, 11, 1047. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mendiola, M.V.; de la Cruz, F. IS91 Transposase Is Related to the Rolling-Circle-Type Replication Proteins of the pUB110 Family of Plasmids. Nucleic Acids Res. 1992, 20, 3521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mendiola, M.V.; Bernales, I.; de la Cruz, F. Differential Roles of the Transposon Termini in IS91 Transposition. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 1994, 91, 1922–1926. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tavakoli, N.; Comanducci, A.; Dodd, H.M.; Lett, M.C.; Albiger, B.; Bennett, P. IS1294, a DNA Element That Transposes by RC Transposition. Plasmid 2000, 44, 66–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garcillán-Barcia, M.P.; De La Cruz, F.; Bernales, I.; Mendiola, M.V. IS91 Rolling-Circle Transposition. In Mobile DNA II; American Society of Microbiology, 2002; pp. 891–904. ISBN 9781555812096. [Google Scholar]

- Toleman, M.A.; Walsh, T.R. Combinatorial Events of Insertion Sequences and ICE in Gram-Negative Bacteria. FEMS Microbiol. Rev. 2011, 35, 912–935. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- TnPedia Team TnPedia: IS91 and ISCR Families of Prokaryotic Insertion Sequences . Zenodo 2025. [CrossRef]

- Andersen, J.B.; Sternberg, C.; Poulsen, L.K.; Bjorn, S.P.; Givskov, M.; Molin, S. New Unstable Variants of Green Fluorescent Protein for Studies of Transient Gene Expression in Bacteria. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 1998, 64, 2240–2246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tokuda, M.; Yuki, M.; Ohkuma, M.; Kimbara, K.; Suzuki, H.; Shintani, M. Transconjugant Range of PromA Plasmids in Microbial Communities Is Predicted by Sequence Similarity with the Bacterial Host Chromosome. Microb. Genom. 2023, 9, mgen.0.001043. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eikmeyer, F.; Hadiati, A.; Szczepanowski, R.; Wibberg, D.; Schneiker-Bekel, S.; Rogers, L.M.; Brown, C.J.; Top, E.M.; Pühler, A.; Schlüter, A. The Complete Genome Sequences of Four New IncN Plasmids from Wastewater Treatment Plant Effluent Provide New Insights into IncN Plasmid Diversity and Evolution. Plasmid 2012, 68, 13–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gomi, R.; Yano, H. Miniature Inverted-Repeat Transposable Elements Mobilize Diverse Antibiotic Resistance Genes in Enterobacteriaceae. bioRxiv 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, F.; Ye, X.; Yin, Z.; Hu, M.; Wang, B.; Liu, W.; Li, B.; Ren, H.; Jin, Y.; Yue, J. Comparative Genomics Reveals New Insights into the Evolution of the IncA and IncC Family of Plasmids. Front. Microbiol. 2022, 13, 1045314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galata, V.; Fehlmann, T.; Backes, C.; Keller, A. PLSDB: A Resource of Complete Bacterial Plasmids. Nucleic Acids Res. 2018, 47, D195–D202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schmartz, G.P.; Hartung, A.; Hirsch, P.; Kern, F.; Fehlmann, T.; Müller, R.; Keller, A. PLSDB: Advancing a Comprehensive Database of Bacterial Plasmids. Nucleic Acids Res. 2022, 50, D273–D278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Molano, L.-A.G.; Hirsch, P.; Hannig, M.; Müller, R.; Keller, A. The PLSDB 2025 Update: Enhanced Annotations and Improved Functionality for Comprehensive Plasmid Research. Nucleic Acids Res. 2025, 53, D189–D196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Haines, A.S.; Akhtar, P.; Stephens, E.R.; Jones, K.; Thomas, C.M.; Perkins, C.D.; Williams, J.R.; Day, M.J.; Fry, J.C. Plasmids from Freshwater Environments Capable of IncQ Retrotransfer Are Diverse and Include pQKH54, a New IncP-1 Subgroup Archetype. Microbiology 2006, 152, 2689–2701. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yano, H.; Rogers, L.M.; Knox, M.G.; Heuer, H.; Smalla, K.; Brown, C.J.; Top, E.M. Host Range Diversification within the IncP-1 Plasmid Group. Microbiology 2013, 159, 2303–2315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fonseca, É.L.; Vicente, A.C. Integron Functionality and Genome Innovation: An Update on the Subtle and Smart Strategy of Integrase and Gene Cassette Expression Regulation. Microorganisms 2022, 10, 224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jové, T.; Da Re, S.; Denis, F.; Mazel, D.; Ploy, M.-C. Inverse Correlation between Promoter Strength and Excision Activity in Class 1 Integrons. PLoS Genet. 2010, 6, e1000793. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghaly, T.M.; Chow, L.; Asher, A.J.; Waldron, L.S.; Gillings, M.R. Evolution of Class 1 Integrons: Mobilization and Dispersal via Food-Borne Bacteria. PLoS One 2017, 12, e0179169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sambrook, J.; Russell, D. Molecular Cloning: A Laboratory Manual, 3rd ed.; Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory: Cold Spring Harbor, NY, 2001; ISBN 9780879695774. [Google Scholar]

-

Methods for Dilution Antimicrobial Susceptibility Tests for Bacteria That Grow Aerobically; Approved Standard-12th Edition. CLSI Document M07; Wayne, PA, 2024.

- Bankevich, A.; Nurk, S.; Antipov, D.; Gurevich, A.A.; Dvorkin, M.; Kulikov, A.S.; Lesin, V.M.; Nikolenko, S.I.; Pham, S.; Prjibelski, A.D.; et al. SPAdes: A New Genome Assembly Algorithm and Its Applications to Single-Cell Sequencing. J. Comput. Biol. 2012, 19, 455–477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tanizawa, Y.; Fujisawa, T.; Nakamura, Y. DFAST: A Flexible Prokaryotic Genome Annotation Pipeline for Faster Genome Publication. Bioinformatics 2018, 34, 1037–1039. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sullivan, M.J.; Petty, N.K.; Beatson, S.A. Easyfig: A Genome Comparison Visualizer. Bioinformatics 2011, 27, 1009–1010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Figure 1.

Locations of the sampling sites are shown on the map. The mainstream of the Tama River is shown in red, and its tributaries are shown in blue.

Figure 1.

Locations of the sampling sites are shown on the map. The mainstream of the Tama River is shown in red, and its tributaries are shown in blue.

Figure 2.

Alignment of pMNBM065-2, IncU plasmid pRA3, and IncQ2γ plasmid pRAS3-3759 (A). Coding DNA region, their directions, and their predicted functions are indicated as block arrows with colors, red for replication, yellow for maintenance, green for conjugative transfer, blue for genes related to mobile genetic element, pink for ARG, and gray for other genes. Insertion sequences (IS) are shown as sky blue-filled boxes. Complex class 1 integron and repeat regions are boxed in light green and red, respectively. (B) The construction of ISCR1 element (i) and ISCR1 element ΔterIS (ii). (C) The formation process of a complex class 1 integron. A circular donor DNA intermediate containing ISCR1 element and non-cassette resistance genes was inserted in an original class 1 integron (i). A complex class 1 integron was formed (ii), followed by six tandemly arranged regions containing ISCR1element, catA, qacEΔ1 and sul1 (iii).

Figure 2.

Alignment of pMNBM065-2, IncU plasmid pRA3, and IncQ2γ plasmid pRAS3-3759 (A). Coding DNA region, their directions, and their predicted functions are indicated as block arrows with colors, red for replication, yellow for maintenance, green for conjugative transfer, blue for genes related to mobile genetic element, pink for ARG, and gray for other genes. Insertion sequences (IS) are shown as sky blue-filled boxes. Complex class 1 integron and repeat regions are boxed in light green and red, respectively. (B) The construction of ISCR1 element (i) and ISCR1 element ΔterIS (ii). (C) The formation process of a complex class 1 integron. A circular donor DNA intermediate containing ISCR1 element and non-cassette resistance genes was inserted in an original class 1 integron (i). A complex class 1 integron was formed (ii), followed by six tandemly arranged regions containing ISCR1element, catA, qacEΔ1 and sul1 (iii).

Figure 3.

Alignment of IncN plasmids isolated from different sources (A) and the accessory region I including antimicrobial resistance genes and mobile genetic elements (B). Two regions inserted accessory genes are outlined with sky blue lines. Coding DNA region, their directions, and their predicted functions are indicated as block arrows with colors, red for replication, yellow for maintenance, green for conjugative transfer, blue for genes related to MGE, pink for ARG, and gray for other genes. IS are shown as sky blue-filled boxes. (C) The genetic structure of miniature inverted-repeat transposable elements (MITEs) containing tetAR and its nucleotide sequences.

Figure 3.

Alignment of IncN plasmids isolated from different sources (A) and the accessory region I including antimicrobial resistance genes and mobile genetic elements (B). Two regions inserted accessory genes are outlined with sky blue lines. Coding DNA region, their directions, and their predicted functions are indicated as block arrows with colors, red for replication, yellow for maintenance, green for conjugative transfer, blue for genes related to MGE, pink for ARG, and gray for other genes. IS are shown as sky blue-filled boxes. (C) The genetic structure of miniature inverted-repeat transposable elements (MITEs) containing tetAR and its nucleotide sequences.

Figure 4.

Alignment of IncC plasmids isolated from different sources (A), the genetic structure of accessory region I of plasmid pMNBL073 (B). A region inserted accessory genes are outlined with sky blue lines. Coding DNA region, their directions, and their predicted functions are indicated as block arrows with colors, red for replication, yellow for maintenance, green for conjugative transfer, blue for genes related to MGE, pink for ARG, and gray for other genes.

Figure 4.

Alignment of IncC plasmids isolated from different sources (A), the genetic structure of accessory region I of plasmid pMNBL073 (B). A region inserted accessory genes are outlined with sky blue lines. Coding DNA region, their directions, and their predicted functions are indicated as block arrows with colors, red for replication, yellow for maintenance, green for conjugative transfer, blue for genes related to MGE, pink for ARG, and gray for other genes.

Figure 5.

Alignment of IncPγ plasmids (A), the genetic structure of Tn402-like class 1 integron of plasmid pYKCS045 (B). A region inserted accessory genes is outlined with sky blue lines. Coding DNA region, their directions, and their predicted functions are indicated as block arrows with colors, red for replication, yellow for maintenance, green for conjugative transfer, blue for genes related to MGE, pink for ARG, and gray for other genes.

Figure 5.

Alignment of IncPγ plasmids (A), the genetic structure of Tn402-like class 1 integron of plasmid pYKCS045 (B). A region inserted accessory genes is outlined with sky blue lines. Coding DNA region, their directions, and their predicted functions are indicated as block arrows with colors, red for replication, yellow for maintenance, green for conjugative transfer, blue for genes related to MGE, pink for ARG, and gray for other genes.

Figure 6.

Comparisons of the genetic structure for the class 1 integrons found in different plasmids from the Tama River (A). The repeat region of plasmid pMNBM065-2 is shown as a single copy for clarity. Coding DNA regions, their directions, and their predicted functions are indicated as block arrows with colors, blue for genes related to mobile genetic element, pink for genes related to antimicrobial resistance genes, and gray for other genes. IS are shown as sky blue-filled boxes. (B) Comparisons of promoters for gene cassettes in the class 1 integrons. Red boxes show –35 and –10 regions of the gene cassette and +1 indicates transcription start point. The boxes with orange indicate PcW promoter, while those with light blue indicate PcH1 promoter.

Figure 6.

Comparisons of the genetic structure for the class 1 integrons found in different plasmids from the Tama River (A). The repeat region of plasmid pMNBM065-2 is shown as a single copy for clarity. Coding DNA regions, their directions, and their predicted functions are indicated as block arrows with colors, blue for genes related to mobile genetic element, pink for genes related to antimicrobial resistance genes, and gray for other genes. IS are shown as sky blue-filled boxes. (B) Comparisons of promoters for gene cassettes in the class 1 integrons. Red boxes show –35 and –10 regions of the gene cassette and +1 indicates transcription start point. The boxes with orange indicate PcW promoter, while those with light blue indicate PcH1 promoter.

Table 1.

Antimicrobial resistance plasmids obtained from the Tama River.

Table 1.

Antimicrobial resistance plasmids obtained from the Tama River.

| Plasmid |

Inc_group |

Size (bp) |

Source |

Methods* |

Accessory genes |

Accession number |

| pMNBM065-2 |

IncU, IncQ2γ |

67,638 |

Tama5 |

B |

tetRC, IS6100, class 1 integron [aac(6’)-IIc, aadA1, qacEΔ1- sul1];

ISCR1 element; catA, qacEΔ1- sul1 (repeat unit x6), orf5

|

LC895900.1 |

| pMNBM072 |

IncN |

55,403 |

Tama5 |

B |

Class 1 integron [aac(6’)-Ib-cr, arr-3, dfrA27, aadA16, qacEΔ1-sul1,

ISCR1 element qnrB6, qacEΔ1-sul1-orf5], tetAR

|

LC663726.1 |

| pMNBL073 |

IncC |

149,764 |

Tama4 |

B |

Class 1 integron (aadA2, qacEΔ1, sul1),

dfrA23, aph(4)-Ia, aac(3)-IVa, floR, tetAR, strAB, sul2

|

LC663722.1 |

| pYKCS045 |

IncPγ |

49,370 |

Tama5 |

T |

Tn402-like class 1 integron [blaGES-24, aac(6’)-Ib4] |

LC623929.1 |

| pMNBL056 |

IncPε |

52,432 |

Tama4 |

B |

Class 1 integron (dfrB1, qacEΔ1-sul1-orf5, tetRA) |

LC623890.1 |

| pYKBL037 |

IncPι |

64,506 |

Tama4 |

T |

Transposon (strAB, class 1 integron [aac(6’)-Ib, ere(A), qacEΔ1-sul1-orf5],

transposon (blaA, qac) |

LC623919.1 |

| pMNDW109 |

IncPβ |

98,131 |

Tama5 |

B |

Tn3-family transposon (mer operon, IS1071, dmfR, IS1071),

IS6100, sul1, qacEΔ1, aadA2,

IS6 composite transposon (mphE, msrE, IS26, tetRC, IS26, tetRC), blaD

|

LC895901.1 |

| pMNDX110 |

IncPβ |

77,896 |

Tama6 |

B |

CusA/CzcA, HlyD, heavy metal resistance, blaC,

IS26, msrE, mphE, IS26, tetCR, IS26

|

LC895902.1 |

| pMNBM077 |

IncPκ |

53,339 |

Tama5 |

B |

Transposon (tetAR, transposon) |

LC623892.1 |

| pYKTC011-1 |

PromAβ-1 |

57,620 |

Tama6 |

T |

Tn501(remnant)(mer operon), IS21, Tn3-family (blaNPS), relE

|

LC623931.1 |

| pMNBL076-1 |

Not classified |

16,094 |

Tama4 |

B |

tetA |

LC663723.1 |

Table 2.

Antibiotic resistance and sensitivity of the hosts. (R, resistant; S, sensitive)*

Table 2.

Antibiotic resistance and sensitivity of the hosts. (R, resistant; S, sensitive)*

| Plasmid |

Inc_group |

Tc(12.5) |

Gm(30) |

Ap(50) |

Km(50) |

Cm(30) |

Sm(25) |

Sm(50) |

Em(25) |

| pMNBM065-2 |

IncU, IncQ2γ |

R |

- |

- |

- |

R |

- |

- |

- |

| pMNBM072 |

IncN |

R |

S |

R |

R |

- |

- |

R |

- |

| pMNBL073 |

IncC |

R |

R |

S |

S |

R |

- |

- |

- |

| pYKCS045 |

IncPγ |

- |

S |

R |

S |

- |

- |

- |

- |

| pMNBL056 |

IncPε |

R |

S |

S |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

| pYKBL037 |

IncPι |

- |

S |

R |

R |

- |

R |

S |

R |

| pMNDW109 |

IncPβ |

R |

S |

R |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

| pMNDX110 |

IncPβ |

R |

S |

S |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

| pMNBM077 |

IncPκ |

R |

- |

S |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

| pYKTC011-1 |

PromAβ-1 |

- |

- |

R |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

| pMNBL076-1 |

Not classified |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).