Submitted:

26 January 2026

Posted:

27 January 2026

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

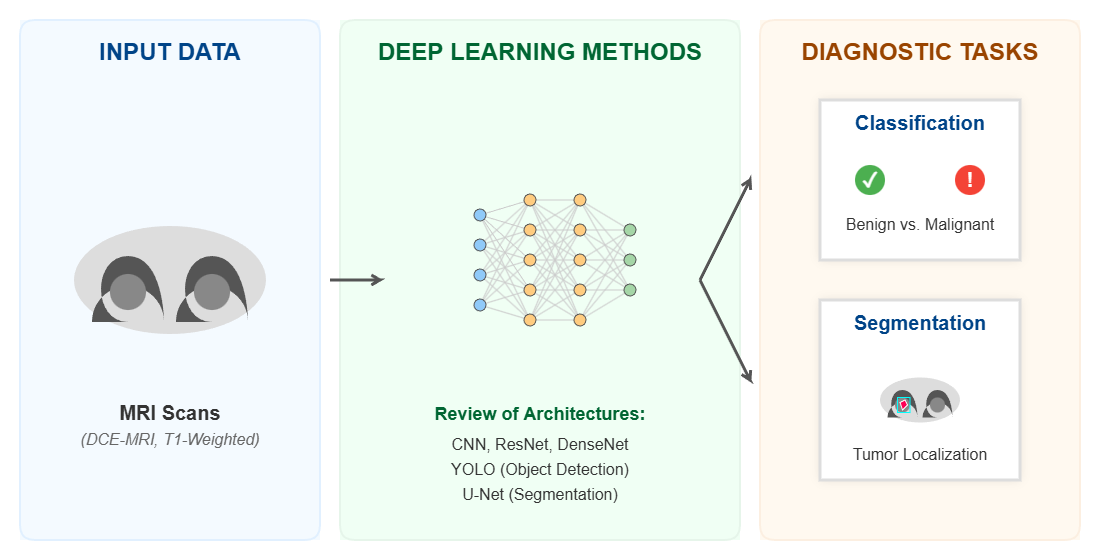

Worldwide, breast cancer affected women increasingly with its incidence influenced by a complex interplay of genetic, environmental, and lifestyle factors, resulting in mortalities and ruined lives after getting affected by this malicious disease especially in younger ages. At that point, researchers have developed tools to treat this disease and continued to enhance their tools to reduce the number of mortalities using imaging tools like mammography, x-rays, magnetic resonance imaging and more. They indicated that when it is earlier diagnosing breast cancer it is easier to handle way too better in a try to achieve their goal improving survival rates. This review provides to focus on recent peer-reviewed research within the last decade that used deep learning methods like convolutional neural networks for breast cancer prediction/classification or segmentation using magnetic resonance imaging scans, that’s due its ability to locate lesions/malignancies that usually escapes traditional imaging tools. By evaluating models’ architectures, datasets, preprocessing for each study, key findings of them revealed that using such deep learning techniques have demonstrated truly promising results achieving high performance metrics for breast cancer assessment. While several limitations still exist like data availability, data quality, and data generalizability. Having that in hands, this review assured the importance of keeping developing robust, interpretable and clinically applicable AI models using MRIs to aid radiologists eliminate tedious tasks and support them with decision-making process.

Keywords:

1. Introduction

Contribution and Novelty

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Search Strategy

2.2. Performance Measures

| Predicted Positive | Predicted Negative | |

| Actual Positive | True Positive (TP) | False Negative (FN) |

| Actual Negative | False Positive (FP) | True Negative (TN) |

2.3. Quality Assessment and Risk Bias

3. Breast Imaging Tools and Data Resources

3.1. Imaging Modalities

| Modality | SpatialResolution | KeyAdvantages | Limitations |

Image Example |

| Mammography | Lower Spatial Resolution | Cost-effective, good accuracy (in early detection), time-efficient | Low sensitivity in dense tissues (usually appears in younger women) |  |

| MRI | High Spatial Resolution | High sensitivity (detecting invasive cancer) Identify undetected malignancies by mammography |

Expensive, prone to false positives. Requires validation. Low specificity |

|

| Histopathology | Very High Spatial Resolution | Definitive diagnosis. Crucial for staging and subtyping. |

Time-consuming requires expertise for manual analysis |  |

| CT-Scans | High | Precise | Can cause allergic reactions, comparably cost |  |

| Ultrasound | Moderate | Less cost, uses sound waves | Low specificity, not suitable for all tumor types |  |

- Detecting magnificence in higher rates: Comparing to mammography for example, MRI said to have a sensitivity rate of 90% comparing to 60% in the best case of MG, increasing the true detection rate in average of 16-30%.

- Detecting malignancies in earlier stages:

- Cancers with tiny sizes most of the time are not detected when using MG only, on the other hand using MRI significantly enhances the rates of detection at these stages.

- Decreasing mortalities by increasing survival rates:

3.2. Data Resources

| Name | No. of cases | Imaging modality | Resolution | Tumor segmentation | Enhanced contrast | Best use case |

| Duke Breast Cancer MRI | 922 patients | MRI (DCE-MRI) | Varies | Yes | Yes | AI/ML, clinical studies |

| Advanced MRI Breast Lesions | 632 MRI sessions | MRI (1.5T) | High | Yes (radiologist-labelled) | Yes | Lesion characterization |

| MAMA-MIA Dataset | 1,506 cases | MRI (DCE-MRI) | Varies | Yes (expert) | Yes | Deep learning segmentation |

| QIN-Breast | Multiple | PET/CT, MRI | Varies | No | Yes | Multi-modal imaging analysis |

| Breast MRI NACT Pilot | Multiple | MRI (DCE-MRI) | High | Yes | Yes | Treatment response tracking |

| RIDER Breast MRI | Multiple | MRI (DWI, ADC) | Varies | No | No | Longitudinal tumor response |

| fastMRI Breast | Large-scale | MRI (k-space, DICOM) | High | No (case-level labels only) | Yes | MRI reconstruction research |

4. Literature Review

4.1. Deep Learning Approaches

4.1.1. Convolutional Neural Networks (CNNs)

- Segmentation –focused studies: where the main goal is to accurately delineate breast tumors or lesions at the pixel level, supporting diagnosis, treatment planning.

- Contextual mapping module, using the swin transformer with reinforcement tokenization to extract features and improve training efficiency.

- Edge analysis module: employ CNNs to enhance edge details for better boundary detection.

- Feature integration module: combines the two modules using graph convolution for effective future fusion.

- 2.

- Classification and detection-focused studies: studies in this category primarily focus on distinguishing benign from malignant or localizing suspicious regions using bounding box detection technique.

- a-

- Extraction of ROI of the input MRIs with lesion annotation.

- b-

- Evaluate the model using five DCNN models: ResNet50, DenseNet, VGG16, GoogLeNet, and AlexNet as for training and prediction.

- c-

- Diagnosing the lesion.

- 3.

- Multimodal and hybrid approaches: several studies have integrated multiple MRI sequences or combined detection and classification models to enhance diagnostic performance.

4.1.2. YOLO Methods

- -

- Backbone: where the main task is to extract useful features from images using CNN architectures, such as ResNet50, or VGG16.

- -

- Neck: Acts as a mediator between the backbone and the head, with a functionality of merging feature maps from different backbone layers and send them for further processing.

- -

- Head: here a process of utilizing features from the neck is being done to make predictions.

4.2. Summary of Included Studies

| Authors | Year | Modality | Primary Task | Method | Performance |

| (Jiao et al.,) | 2020 | DCE-MRI | Segmentation | U-Net (Segmentation) Faster RCNN (Detection) ResNet-101 (Backbone) |

DSC: 0.951 Jaccard Coefficient: 0.908 Sensitivity: 0.948 FRCNN Sensitivity: 0.874 |

| (Zhu et al.,) | 2022 | Multiparametric MRI | Multimodal | V-Net (Segmentation) ResNet (Characterization) |

DSC: 0.860 AUC: 0.927 Accuracy: 0.846 Sensitivity: 0.831 |

| (Hirsch et al.,) | 2022 | DCE-MRI | Segmentation | 3D U-Net | DSC: 0.77 |

| (Yang et al.,) | 2024 | MRI | Classification/Detection | YOLOv8 | Recall: 0.961 Precision: 0.964 mAP: 0.971 |

| (Akbar et al.,) | 2025 | DCE-MRI | Segmentation | Swin Tranformer, CNN, and Graph Convolution | QIN DATASET: DSC: 0.9389 Specificity: 0.9992 DUKE DATASET: DSC: 0.8336 Specificity: 0.9995 |

| (Khaled et al.,) | 2022 | DCE-MRI | Segmentation | U-Net Ensemble | DSC: 0.680 |

| (Peng et al.,) | 2022 | 3D Multimodal MRI (T1 & T1c) | Segmentation | IMIIN using Dense-Net | T1c MODAL: DSC: 0.9049 Sensitivity: 0.9308 T1 MODAL: DSC: 0.8507 Sensitivity: 0.8923 |

| (Akgül et al.,) | 2024 | DCE-MRI | Classification/Detection | YOLOv3 (Region Detection) DenseNet-201 (Classification) |

Accuracy: 0.9241 Sensitivity: 0.9244 Specificity: 0.9244 |

5. Discussion

5.1. Sample Size Limitation

5.2. Reuse of Public Datasets

5.3. Lack of External Validation and Domain Shift

5.4. Explainable AI (XAI)

5.5. Barriers to Integration into Radiology Workflows

6. Conclusions

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| MRI | Magnetic Resonance Imaging |

| DL | Deep Learning |

| YOLO | You Only Look Once |

| BC | Breast Cancer |

| CNN | Convolutional Neural Network |

| ML | Machine Learning |

| TP | True Positive |

| TN | True Negative |

| FP | False Positive |

| FN | False Negative |

| NN | Neural Network |

| CAD | Computer Aided Diagnosis |

| DSC | Dice Similarity Coefficient |

| JC | Jaccard Coefficient |

| mpMRI | Multiparametric MRI |

| DCE-MRI | Dynamic Contrast Enhanced MRI |

| ROI | Regions of Interest |

| IMIIN | Inter-modality Information Interaction Network |

| XAI | Explainable AI |

References

- WHO. Breast cancer deaths. [PubMed]

- Michaelson, J. S. Gauging the Impact of Breast Carcinoma Screening in Terms of Tumor Size and Death Rate. Cancer 2003, vol. 98(no. 10), 2114–2124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, C. H. Breast Cancer Screening With Imaging: Recommendations From the Society of Breast Imaging and the ACR on the Use of Mammography, Breast MRI, Breast Ultrasound, and Other Technologies for the Detection of Clinically Occult Breast Cancer. Journal of the American College of Radiology 2010, vol. 7(no. 1), 18–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hodgson, D. C.; Cotton, C.; Crystal, P.; Nathan, P. C. Impact of early breast cancer screening on mortality among young survivors of childhood Hodgkin’s lymphoma. J. Natl. Cancer Inst. 2016, vol. 108(no. 7). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, J. A deep learning-based multimodal medical imaging model for breast cancer screening. Sci. Rep. 2025, vol. 15(no. 1). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmad, J. Deep learning empowered breast cancer diagnosis: Advancements in detection and classification. PLoS One 2024, vol. 19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmad, J. Deep learning empowered breast cancer diagnosis: Advancements in detection and classification. PLoS One 2024, vol. 19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Su, Y.; Liu, Q.; Xie, W.; Hu, P. YOLO-LOGO: A transformer-based YOLO segmentation model for breast mass detection and segmentation in digital mammograms. Comput. Methods Programs Biomed. 2022, vol. 221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- E. Mahoro and M. A. Akhloufi, “Applying Deep Learning for Breast Cancer Detection in Radiology,” Nov. 01, 2022, MDPI. [CrossRef]

- B. J. Erickson and F. Kitamura, “Magician’s corner: 9. performance metrics for machine learning models,” May 01, 2021, Radiological Society of North America Inc. 01 May. [CrossRef]

- Vujović, Ž. Classification Model Evaluation Metrics. International Journal of Advanced Computer Science and Applications 2021, vol. 12(no. 6), 599–606. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sokolova, M.; Lapalme, G. A systematic analysis of performance measures for classification tasks. Inf. Process. Manag. 2009, vol. 45(no. 4), 427–437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sokolova, M.; Lapalme, G. A systematic analysis of performance measures for classification tasks. Inf. Process. Manag. 2009, vol. 45(no. 4), 427–437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saito, T.; Rehmsmeier, M. The precision-recall plot is more informative than the ROC plot when evaluating binary classifiers on imbalanced datasets. PLoS One 2015, vol. 10(no. 3). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Y. Jiao and P. Du, “Performance measures in evaluating machine learning based bioinformatics predictors for classifications,” Dec. 01, 2016, Higher Education Press. [CrossRef]

- B. J. Erickson and F. Kitamura, “Magician’s corner: 9. performance metrics for machine learning models,” May 01, 2021, Radiological Society of North America Inc. 01 May. [CrossRef]

- Pinker, K. Diffusion-Weighted Imaging With Apparent Diffusion Coefficient Mapping for Breast Cancer Detection as a Stand-Alone Parameter Comparison With Dynamic Contrast-Enhanced and Multiparametric Magnetic Resonance Imaging. Invest. Radiol. 2018, vol. 53(no. 10), 587–595. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- H. Hussein et al., “Supplemental Breast Cancer Screening in Women with Dense Breasts and Negative Mammography: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis,” Mar. 01, 2023, Radiological Society of North America Inc. [CrossRef]

- Roca, S. Alonso; Delgado Laguna, A. B.; Lexarreta, J. Arantzeta; Campo, B. Cajal; Jareño, S. Santamaría. Screening in patients with increased risk of breast cancer (part 1): pros and cons of MRI screening. Radiologia 2020, vol. 62(no. 4), 252–265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gareth, E. D. MRI breast screening in high-risk women: Cancer detection and survival analysis. Breast Cancer Res. Treat. 2014, vol. 145(no. 3), 663–672. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pataky, R. Cost-effectiveness of MRI for breast cancer screening in BRCA1/2 mutation carriers. BMC Cancer 2013, vol. 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- F. J. Gilbert and A. Selamoglu, “Personalised screening: is this the way forward?,” Apr. 01, 2018, W.B. Saunders Ltd. [CrossRef]

- K. A. Dishner et al., “A Survey of Publicly Available MRI Datasets for Potential Use in Artificial Intelligence Research,” Feb. 01, 2024, John Wiley and Sons Inc. [CrossRef]

- Huang, W. Variations of dynamic contrast-enhanced magnetic resonance imaging in evaluation of breast cancer therapy response: A multicenter data analysis challenge. Transl. Oncol. 2014, vol. 7(no. 1), 153–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Solomon, E. FastMRI Breast: A Publicly Available Radial k-Space Dataset of Breast Dynamic Contrast-enhanced MRI. Radiol. Artif. Intell. 2025, vol. 7(no. 1). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- C. Panico et al., “Staging Breast Cancer with MRI, the T. A Key Role in the Neoadjuvant Setting,” Dec. 01, 2022, MDPI. [CrossRef]

- D. Anaby, D. Shavin, G. Zimmerman-Moreno, N. Nissan, E. Friedman, and M. Sklair-Levy, “‘Earlier than Early’ Detection of Breast Cancer in Israeli BRCA Mutation Carriers Applying AI-Based Analysis to Consecutive MRI Scans,” Cancers (Basel)., vol. 15, no. 12, Jun. 2023. [CrossRef]

- Saha. A machine learning approach to radiogenomics of breast cancer: A study of 922 subjects and 529 dce-mri features. Br. J. Cancer 2018, vol. 119(no. 4), 508–516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- L. Garrucho et al., “A large-scale multicenter breast cancer DCE-MRI benchmark dataset with expert segmentations,” Jun. 2024, [Online]. Available: http://arxiv.org/abs/2406.13844.

- D. Newitt and N. Hylton, “The Cancer Imaging Archive.”.

- G. Litjens et al., “A survey on deep learning in medical image analysis,” Dec. 01, 2017, Elsevier B.V. [CrossRef]

- M. P. R. D. W. M. D. S. M. B. P. et al Constance D. Lehman. Diagnostic accuracy of digital screening mammography with and without computer-aided detection. JAMA Inter Med 2015, vol. 175(11), 1828–1837. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- L. Balkenende, J. Teuwen, and R. M. Mann, “Application of Deep Learning in Breast Cancer Imaging,” Sep. 01, 2022, W.B. Saunders. [CrossRef]

- D. Albashish, R. Al-Sayyed, A. Abdullah, M. H. Ryalat, and N. Ahmad Almansour, “Deep CNN Model based on VGG16 for Breast Cancer Classification,” in 2021 International Conference on Information Technology, ICIT 2021 - Proceedings, Institute of Electrical and Electronics Engineers Inc., Jul. 2021, pp. 805–810. [CrossRef]

- Chugh, G.; Kumar, S.; Singh, N. Survey on Machine Learning and Deep Learning Applications in Breast Cancer Diagnosis. Cognit. Comput. 2021, vol. 13(no. 6), 1451–1470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- M. Farkhadov, A. Eliseev, and N. Petukhova, “Explained Artificial Intelligence Helps to Integrate Artificial and Human Intelligence into Medical Diagnostic Systems: Analytical Review of Publications,” in 14th IEEE International Conference on Application of Information and Communication Technologies, AICT 2020 - Proceedings, Institute of Electrical and Electronics Engineers Inc., Oct. 2020. [CrossRef]

- Xue Zhao, Jing-Wen Bai, Qiu Guo, Ken Ren, and Guo-Jun Zhang, “22-Clinical applications of deep learning in breast MRI,” BBA - Review on Cancer, 2023.

- Gubern-Mérida. Automated localization of breast cancer in DCE-MRI. Med. Image Anal. 2015, vol. 20(no. 1), 265–274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thakran, S.; Chatterjee, S.; Singhal, M.; Gupta, R. K.; Singh, A. Automatic outer and inner breast tissue segmentation using multi-parametric MRI images of breast tumor patients. PLoS One 2018, vol. 13(no. 1). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jiao, H.; Jiang, X.; Pang, Z.; Lin, X.; Huang, Y.; Li, L. Deep Convolutional Neural Networks-Based Automatic Breast Segmentation and Mass Detection in DCE-MRI. Comput. Math. Methods Med. vol. 2020, 2020. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- L. Hirsch et al., “Radiologist-level Performance by Using Deep Learning for Segmentation of Breast Cancers on MRI Scans,” Radiol. Artif. Intell., vol. 4, no. 1, Jan. 2022. [CrossRef]

- Akbar. Reinforcement tokenization and graph convolution for high-precision breast tumor segmentation in DCE-MRI. Biomed. Signal Process. Control 2025, vol. 100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khaled, R.; Vidal, J.; Vilanova, J. C.; Martí, R. A U-Net Ensemble for breast lesion segmentation in DCE MRI. Comput. Biol. Med. 2022, vol. 140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Peng, C. IMIIN: An inter-modality information interaction network for 3D multi-modal breast tumor segmentation. Computerized Medical Imaging and Graphics 2022, vol. 95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, J. Development and validation of a deep learning model for breast lesion segmentation and characterization in multiparametric MRI. Front. Oncol. 2022, vol. 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Y. Yang, H. Zhou, J. Wu, and M. Zhang, “Analysis of Breast MRI Images Using YOLOv8x Approach,” in 2024 9th International Conference on Image, Vision and Computing, ICIVC 2024, Institute of Electrical and Electronics Engineers Inc., 2024, pp. 410–415. [CrossRef]

- Akgül; Kaya, V.; Karavaş, E.; Aydin, S.; Baran, A. A novel artificial intelligence-based hybrid system to improve breast cancer detection using DCE-MRI. Bulletin of the Polish Academy of Sciences: Technical Sciences 2024, vol. 72(no. 3). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ariyametkul; Paing, M. P. Analyzing explainability of YOLO-based breast cancer detection using heat map visualizations. Quant. Imaging Med. Surg. 2025, vol. 15(no. 7), 6252–6271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abd El-Hafeez, T.; Tarek, M.; Sayed, A. Optimizing YOLOv11 for automated classification of breast cancer in medical images. Sci. Rep. 2025, vol. 15(no. 1). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meng, M.; Zhang, M.; Shen, D.; He, G.; Guo, Y. Detection and classification of breast lesions with You Only Look Once version 5. Future Oncology 2022, vol. 18(no. 39), 4361–4370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Esteva et al., “Deep learning-enabled medical computer vision,” Dec. 01, 2021, Nature Research. 01 Dec. [CrossRef]

- Li, Z.; Dong, M.; Wen, S.; Hu, X.; Zhou, P.; Zeng, Z. CLU-CNNs: Object detection for medical images. Neurocomputing 2019, vol. 350, 53–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diwan, T.; Anirudh, G.; Tembhurne, J. V. Object detection using YOLO: challenges, architectural successors, datasets and applications. Multimed. Tools Appl. 2023, vol. 82(no. 6), 9243–9275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- C. Chen et al., “YOLO-Based UAV Technology: A Review of the Research and Its Applications,” Mar. 01, 2023, Multidisciplinary Digital Publishing Institute (MDPI). [CrossRef]

- M. Hussain, “YOLO-v1 to YOLO-v8, the Rise of YOLO and Its Complementary Nature toward Digital Manufacturing and Industrial Defect Detection,” Jul. 01, 2023, Multidisciplinary Digital Publishing Institute (MDPI). [CrossRef]

- Soni and A. Rai, “YOLO for Medical Object Detection (2018–2024),” Institute of Electrical and Electronics Engineers (IEEE), Sep. 2024, pp. 1–7. [CrossRef]

- P. Jiang, D. Ergu, F. Liu, Y. Cai, and B. Ma, “A Review of Yolo Algorithm Developments,” in Procedia Computer Science, Elsevier B.V., 2021, pp. 1066–1073. [CrossRef]

- Ragab, M. G. A Comprehensive Systematic Review of YOLO for Medical Object Detection (2018 to 2023). IEEE Access 2024, vol. 12, 57815–57836. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).