1. Introduction

Skeletal muscle regeneration depends on the timely activation and coordinated fate progression of skeletal muscle stem cells (MuSCs), which reside beneath the basal lamina and maintain tissue integrity across repeated bouts of injury and physiological stress [

1,

2,

3]. In aged muscle, regenerative decline is a well-established hallmark, accumulating evidence indicates that this impairment cannot be explained solely by a quantitative loss of MuSCs [

4,

5]. Instead, multiple studies support a qualitative shift: MuSCs remain present but show diminished efficacy in executing the early steps required for productive regeneration [

6,

7,

8,

9].

Satellite cell activation represents a critical transitional process in which quiescent MuSCs break homeostasis and acquire regenerative competence [

3]. This transition precedes cell-cycle entry and occurs upstream of canonical myogenic transcriptional programs [

10]. Increasing evidence suggests that early activation constitutes a vulnerable checkpoint that integrates intrinsic cellular state with extrinsic niche-derived signals [

4,

11]. During this phase, MuSCs undergo extensive cytoskeletal remodeling, changes in adhesion and polarity, metabolic reprogramming, and induction of immediate early gene networks [

11]. Failure to execute these events with appropriate timing and coordination can delay regeneration, bias fate trajectories, or compromise long-term stem cell function [

6,

7].

Aging profoundly alters the muscle microenvironment, introducing chronic oxidative stress, low-grade inflammation, and mechanical instability [

12]. These perturbations place a disproportionate burden on early activation, increasing the frequency of delayed or abortive regenerative responses and accelerating stem cell attrition across repeated regenerative cycles [

6,

7,

9]. Consequently, preserving the fidelity of early satellite cell activation—rather than simply enhancing downstream proliferation or differentiation—has emerged as a central issue in understanding age-associated regenerative decline [

4,

13].

MG53 (tripartite motif–containing protein 72,

TRIM72) is a striated muscle-enriched protein classically defined by its role in membrane repair in mature myofibers. In response to oxidative stress, MG53 undergoes redox-dependent oligomerization, enabling rapid recruitment of vesicular repair machinery to sites of membrane disruption [

14,

15,

16]. Beyond this canonical role, MG53 has also been implicated in broader stress-responsive processes, including modulation of inflammatory signaling and regulation of systemic regenerative capacity in vivo [

14,

17,

18]. Notably, Bian et al. reported enhanced cell proliferation in the MG53–tPA group [

19], although the mechanisms by which MG53 influences satellite cell behavior—particularly in aging muscle—remain incompletely defined.

Given its stress-responsive properties and association with membrane-associated remodeling, MG53 may exert functions beyond terminally differentiated myofibers [

20]. In this review, we propose that MG53 acts during the earliest stages of satellite cell activation in aged muscle. Rather than serving as a direct determinant of lineage commitment, MG53 is positioned as a stress-buffering factor that stabilizes early activation dynamics, thereby supporting regenerative competence under conditions of elevated cellular stress.

2. The Aged Muscle Stem Cell Niche and the Fragility of Early Satellite Cell Activation

2.1. Classical Satellite Cell States Revisited in Aging

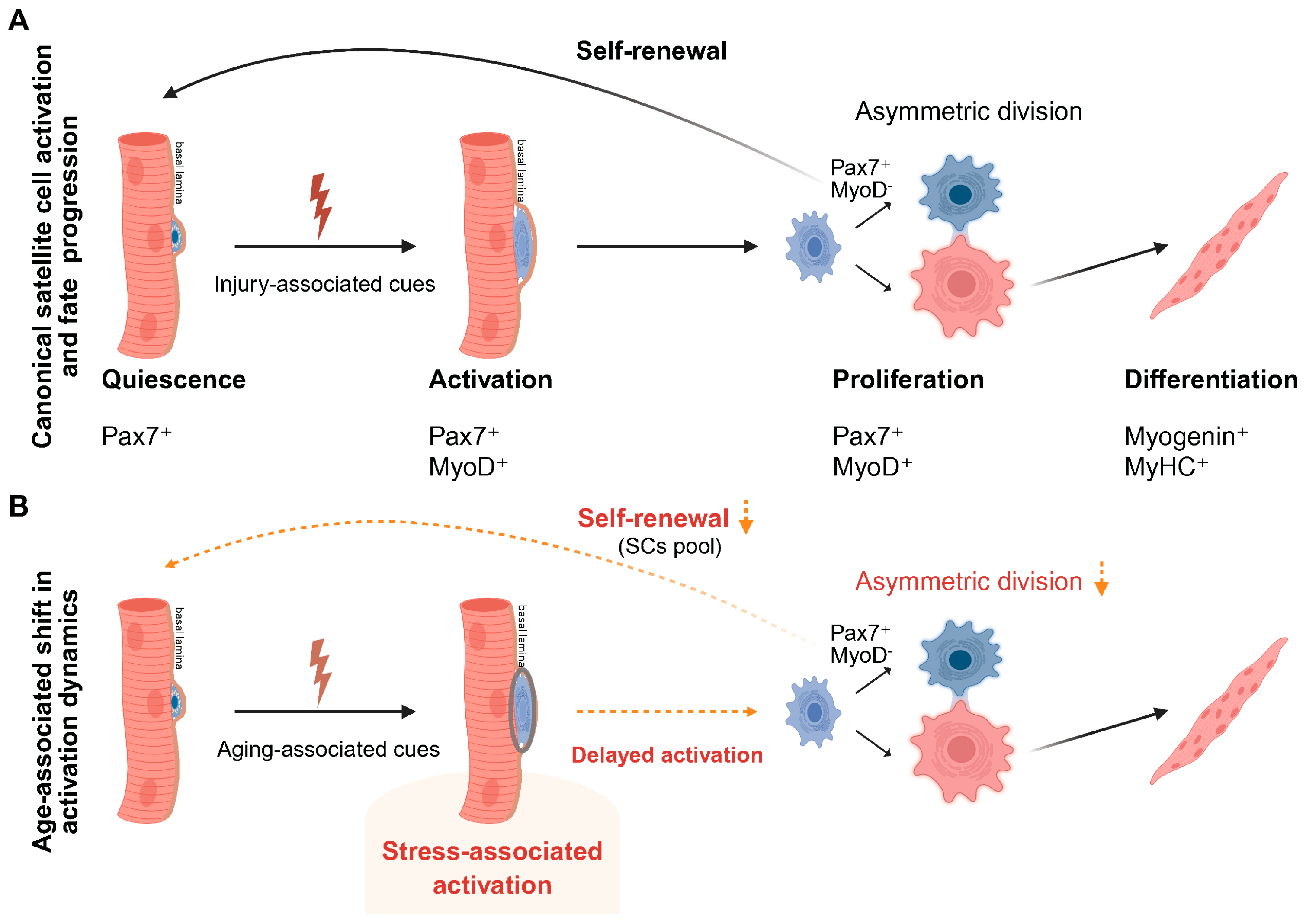

Satellite cells maintain skeletal muscle integrity by residing quiescent under homeostatic conditions and rapidly activating in response to injury or stress. Canonically, regeneration proceeds from quiescence through activation, proliferation, differentiation, and self-renewal, restoring myofiber structure while preserving the stem cell pool [

12,

21] (

Figure 1A).

However, this linear view underestimates the importance of the earliest regenerative transition. Exit from quiescence represents a discrete, tightly regulated activation phase that precedes cell-cycle entry and is not simply a passive precursor to proliferation [

1,

3]. Accumulating evidence supports the existence of a preparatory activation state in which satellite cells integrate systemic, niche-derived, and intrinsic cues to establish regenerative competence [

10,

12,

22]. Rodgers et al. showed that systemic stimuli can drive quiescent stem cells into a metabolically primed G

Alert state via mTORC1 activation, enhancing regenerative readiness without inducing immediate proliferation [

10]. Consistent with this view, in situ fixation studies revealed that early activation involves transcriptional reprogramming and cytoskeletal remodeling prior to overt cell-cycle progression [

11].

Importantly, early activation is tightly coupled to division symmetry and long-term stem cell fate. Seminal work established asymmetric division as a core mechanism supporting satellite cell self-renewal and regenerative sustainability [

23]. Subsequent in vivo studies further showed that even modest shifts in the balance between asymmetric and symmetric divisions are sufficient to impair muscle repair [

24]. These findings indicate that defects arising upstream of cell-cycle entry can compromise regenerative output, even when downstream proliferative or differentiation programs remain largely intact.

Aging does not eliminate the regenerative sequence but alters how it is executed. In aged muscle, satellite cell numbers are largely maintained [

5,

25], yet exit from quiescence becomes slower and less coordinated. Age-related niche perturbations destabilize quiescence maintenance [

26], while intrinsic changes bias satellite cells toward irreversible quiescence or senescence [

9]. These alterations disrupt the timing and reliability of early activation, leading to impaired self-renewal and reduced regenerative efficiency. Thus, age-associated regenerative decline is more accurately viewed as a failure of activation fidelity rather than a loss of myogenic potential (

Figure 1B).

2.2. Early Activation as a Stress-Sensitive Transitional Checkpoint in Aging

Early satellite cell activation represents a discrete transitional phase that precedes cell-cycle entry and is particularly sensitive to cellular stress [

1]. Within hours of injury, satellite cells initiate an early activation program that is separable from myogenic commitment, characterized by rapid changes in cell shape, adhesion, and polarity before robust

MyoD induction [

11]. In parallel, in vivo transcriptional analyses reveal early metabolic and chromatin priming that establishes activation competence prior to proliferation [

27,

28]. These findings support the view that activation is not a binary switch, but a regulated interval requiring precise coordination between structural remodeling and transcriptional reprogramming while responding to niche-derived cues.

Passage through early activation is neither uniform nor guaranteed. In vivo lineage-tracking and niche-manipulation studies show that activation trajectories vary across individual satellite cells and are shaped by local constraints [

24]. Functional evidence further indicates that early activation can stall or fail to progress into productive proliferation when adaptive capacity is insufficient [

10,

11]. Importantly, such failure does not reflect loss of myogenic identity, but rather compromised activation fidelity, manifested as delayed, asynchronous, or unstable execution of early activation steps that disrupt downstream regenerative timing.

Aging selectively amplifies this vulnerability. Age-associated alterations in the stem cell niche destabilize the quiescence-to-activation transition and increase the stress burden encountered during early activation [

26], while intrinsic aging-related changes bias satellite cells toward irreversible quiescence or senescence, narrowing the margin for successful activation [

9]. As a result, aged satellite cells are more likely to enter a prolonged and poorly synchronized activation state, reducing coordination across the population and impairing subsequent cell-cycle entry and self-renewal [

22]. Viewing early activation as a regulated checkpoint therefore helps explain why aging preferentially compromises regenerative competence by degrading activation fidelity rather than eliminating the stem cell pool.

2.3. The Aged Muscle Stem Cell Niche Constrains Early Activation and Introduces Delayed Activation Kinetics

A defining feature of muscle aging is a progressive decline in niche support for timely and coordinated satellite cell activation. Rather than reflecting loss of satellite cell number, age-associated regenerative failure increasingly arises from alterations in the local niche that constrain early activation competence [

25,

29,

30]. Chronic inflammation [

8,

25], redox imbalance [

30], and extracellular matrix remodeling [

8,

25,

29,

30] reshape the physical and biochemical environment encountered during early regeneration, increasing the stress load imposed at the activation checkpoint.

These niche-level alterations act primarily upstream of cell-cycle entry. Age-related changes in extracellular matrix composition and mechanical properties are sufficient to disrupt satellite cell behavior, while restoration of youth-like matrix cues partially rescues regenerative performance in aged muscle [

8,

29]. In parallel, elevated tonic signaling within the aged niche destabilizes quiescence control and promotes inefficient or inappropriate activation, progressively eroding self-renewal capacity and delaying the onset of productive regeneration [

26].

Early activation is also tightly coupled to metabolic readiness, which imposes an additional constraint on activation fidelity. Distinct metabolic states shape the ability of satellite cells to execute early activation programs and influence subsequent regenerative efficiency, providing a mechanism by which the aged niche biases activation toward delayed, asynchronous, or non-productive trajectories [

31]. As a result, satellite cell activation in aged muscle becomes slower and less synchronized across the population, reducing effective regenerative output even when satellite cell numbers remain largely preserved [

32].

These findings point to early activation as a rate-limiting checkpoint in aged muscle regeneration, where disrupted quiescence exit, altered niche sensing, and impaired metabolic preparedness converge to constrain regenerative competence (

Figure 1B).

3. Early Activation as a Vulnerable Checkpoint in Aged Muscle

Skeletal muscle regeneration declines with age despite largely preserved satellite cell numbers, indicating functional impairment rather than stem cell depletion. Increasing evidence suggests that aged satellite cells fail to exit quiescence in a timely and coordinated manner [

7], entering a stress-adapted [

9], low-efficiency activation state before clear defects in proliferation or differentiation emerge [

25]. Under these conditions, early activation becomes a vulnerable checkpoint in which activation quality strongly influences downstream regenerative outcomes. Inefficient progression through this phase may transiently sustain regeneration via compensatory responses, while progressively eroding self-renewal capacity and long-term maintenance of the satellite cell pool [

6,

13].

3.1. The Aged Niche Selectively Burdens Early Activation

Age-associated changes in the muscle microenvironment—including persistent oxidative stress, chronic inflammation, and progressive extracellular matrix stiffening—do not uniformly impair all stages of the myogenic program. Instead, growing evidence indicates that these alterations place a disproportionate burden on early activation [

7], a phase that is particularly sensitive to niche-derived mechanical [

8] and signaling cues required for coordinated exit from quiescence and reliable activation execution [

26].

In aged muscle, satellite cells more often exhibit delayed or unstable activation than an outright failure of proliferation [

9]. Disruption at this stage is frequently associated with altered division patterns, reflecting impaired activation quality rather than intrinsic loss of proliferative capacity [

23,

24,

25]. Consistent with this interpretation, engineered niche systems show that matrix stiffness and related mechanical cues directly regulate division mode and self-renewal behavior, underscoring the sensitivity of early activation to biophysical niche properties [

33].

Signaling pathways that govern asymmetric division and long-term self-renewal, including p38α/β MAPK–dependent programs, act preferentially during the quiescence-to-activation transition [

6]. This restricted temporal window makes early activation especially sensitive to niche perturbations, such that excess stress and distorted signaling in aged muscle disrupt the coordination and timing required for high-fidelity activation [

6,

13].

3.2. Transcriptomic Evidence for a Stage-Selective Defect in Aged Satellite Cells

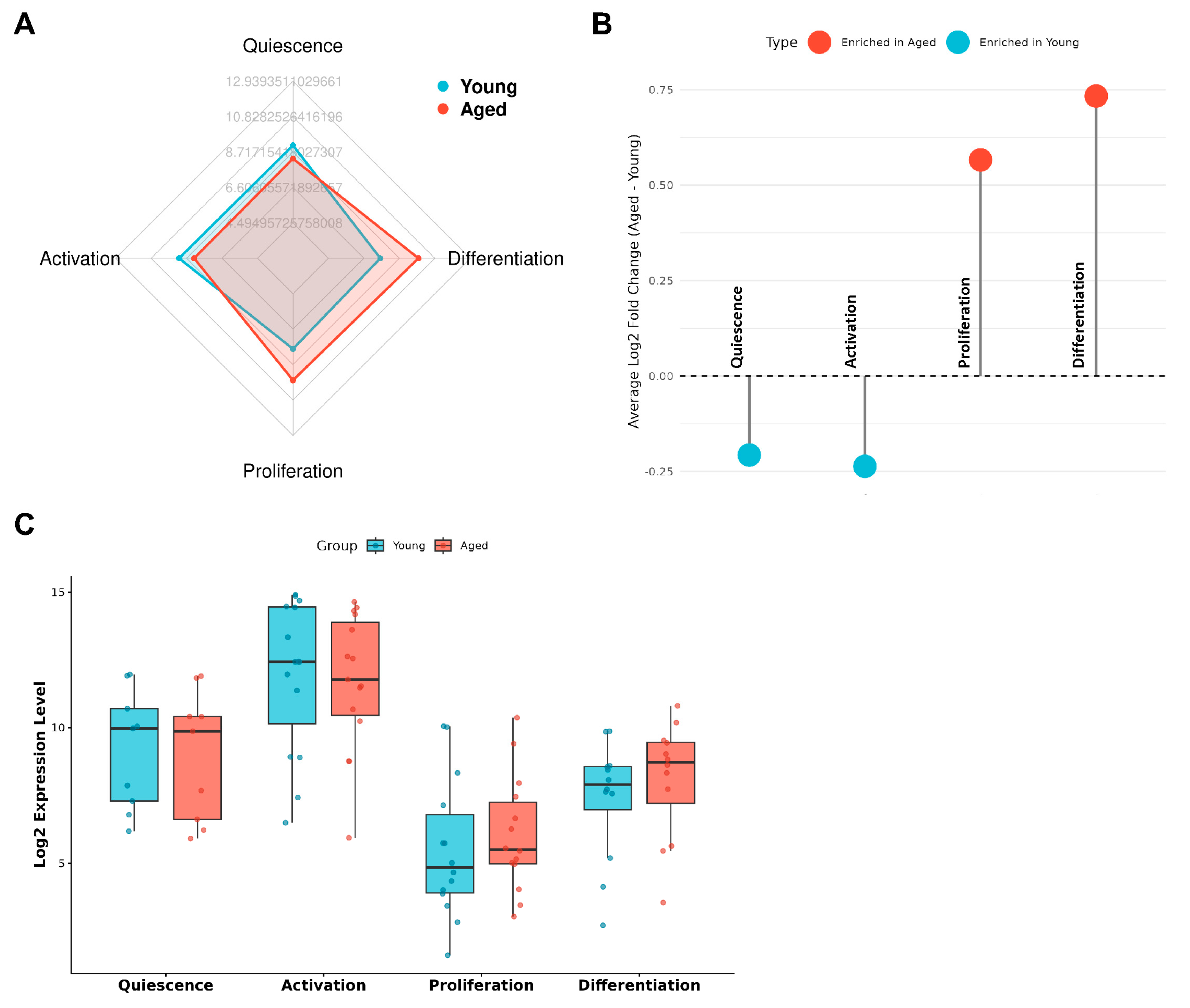

To test whether aging imposes a stage-selective constraint consistent with an early activation checkpoint model, we analyzed the publicly available GEO dataset GSE126665, which profiles FACS-purified satellite cells isolated from young and aged mouse skeletal muscle [

34]. Rather than interrogating individual differentially expressed genes, we evaluated curated gene sets corresponding to discrete stages of the regenerative trajectory, including quiescence, early activation, proliferation, and differentiation.

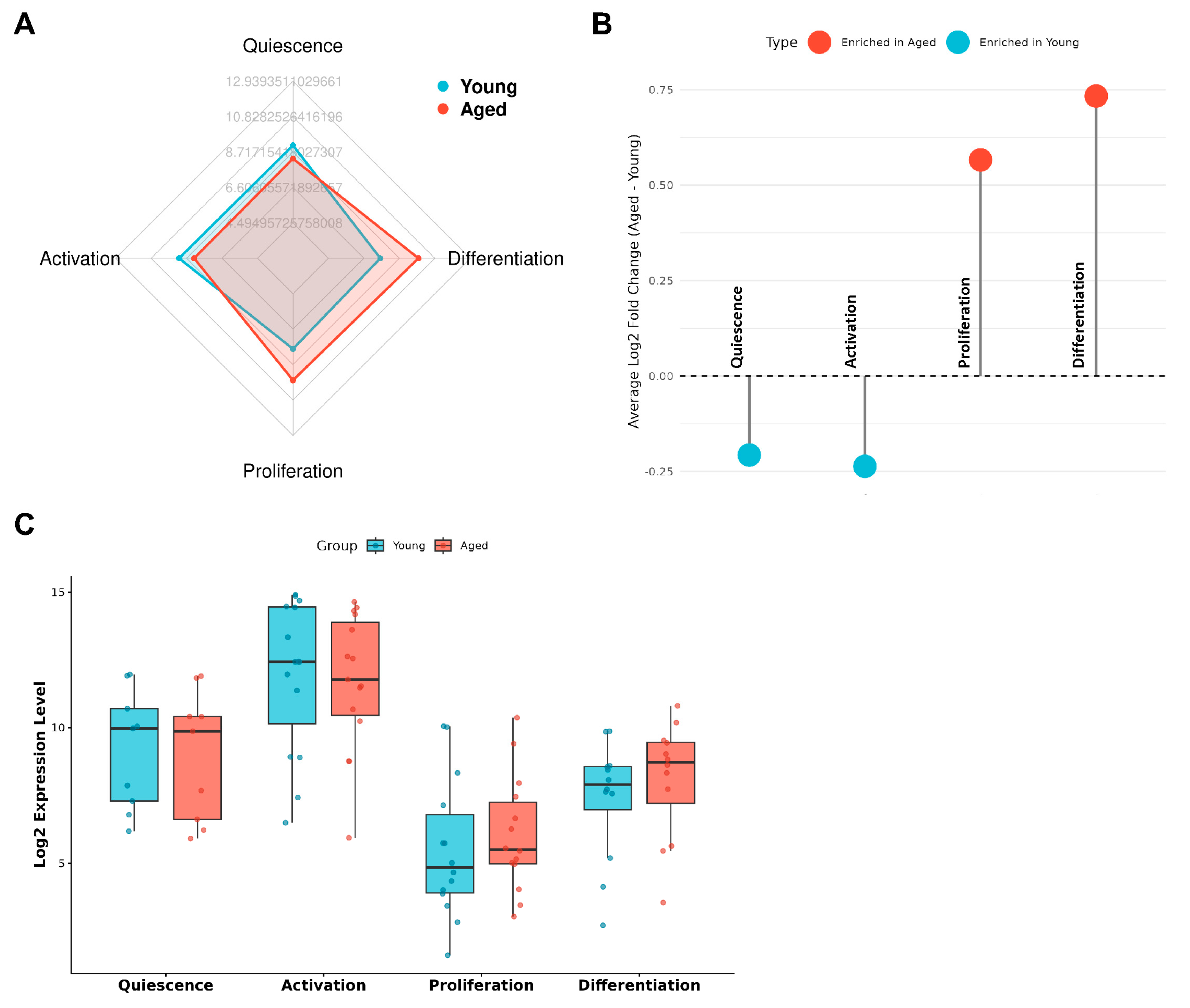

This analysis revealed a consistent and asymmetric pattern: transcriptional programs supporting quiescence maintenance and early activation were selectively attenuated in aged satellite cells, whereas gene sets associated with proliferation and differentiation were comparatively preserved (

Figure 2A–C). This stage-selective transcriptional reweighting was reproducible across complementary analytical views, including aggregate stage-level activity scores, enrichment distributions, and per-sample comparisons, arguing against a global suppression of myogenic capacity with age.

Instead, these data indicate that age-associated regenerative decline is linked primarily to reduced transcriptional support for entry into the regenerative program rather than loss of downstream myogenic competence. Proliferation- and differentiation-associated programs remain accessible in the subset of aged satellite cells that successfully traverse early activation, consistent with early activation functioning as a selective and failure-prone checkpoint rather than a uniform collapse of myogenic potential [

34].

3.3. Compensatory Proliferation Masks Early Failure But Accelerates Long-Term Attrition

A stage-selective defect in early activation provides a mechanistic explanation for a recurring paradox in aged muscle regeneration: markers of proliferation and differentiation remain detectable after injury, yet regenerative capacity progressively declines with repeated repair cycles. When early activation is inefficient, regenerative demand is met disproportionately by the subset of satellite cells that successfully traverse this checkpoint, rather than by uniform recruitment of the stem cell pool. This compensatory reliance can sustain short-term regeneration but does so at the cost of long-term stem cell maintenance.

Durable self-renewal depends on tightly regulated signaling during the quiescence-to-activation transition, a window that is particularly vulnerable in aged satellite cells. Consistent with this framework, age-associated dysregulation of p38α/β MAPK signaling impairs asymmetric division and reduces the generation of quiescent daughter cells, thereby accelerating stem cell attrition across repeated rounds of regeneration [

6,

9,

13].

These observations indicate that compensatory proliferation can mask early activation failure while simultaneously driving progressive depletion of the satellite cell pool. Regenerative decline in aged muscle therefore reflects defects arising upstream of proliferation and differentiation, rather than a primary loss of downstream myogenic capacity.

4. MG53: Beyond Membrane Repair

The preceding sections identify early satellite cell activation as a stress-sensitive checkpoint that disproportionately limits regeneration in aged muscle. This perspective shifts emphasis from boosting downstream myogenic output to stabilizing activation under stress during the quiescence-to-activation transition. MG53—best known for its role in membrane repair—emerges as a candidate whose stress-responsive, membrane-associated functions are well suited to the demands of early activation in aging muscle.

4.1. Canonical Roles of MG53 in Skeletal Muscle

MG53 (

TRIM72) is a striated muscle–enriched tripartite motif protein best known for its essential role in sarcolemmal membrane repair. In skeletal myofibers, MG53 rapidly senses membrane disruption and nucleates repair complexes at injury sites, coordinating vesicle recruitment and membrane resealing under contractile stress [

15].

MG53 contains an N-terminal RING domain, followed by a B-box, coiled-coil region, and a C-terminal PRY/SPRY domain that supports protein–protein interactions and higher-order assembly. Recent structural studies demonstrate that coordinated domain interactions enable MG53 oligomerization and membrane-associated activation, both of which are required for efficient membrane repair [

35,

36].

Beyond its scaffolding role, MG53 also functions as a RING-dependent E3 ubiquitin ligase. A well-characterized substrate is insulin receptor substrate-1 (IRS-1), whose ubiquitination by MG53 dampens IGF/insulin signaling and modulates myogenic progression in a context- and timing-dependent manner [

37,

38].

Together, these properties define MG53 as a membrane-proximal, stress-responsive regulator that couples membrane perturbation to adaptive control of intracellular signaling. This dual capacity provides a mechanistic rationale for considering MG53 function beyond terminally differentiated myofibers, particularly during early satellite cell activation—a phase marked by rapid membrane remodeling and heightened sensitivity to stress and signaling imbalance.

4.2. Activation-Associated stress, Membrane Remodeling, and Signaling Imbalance in Aged Satellite Cells

Early satellite cell activation precedes cell-cycle entry and requires tight temporal coordination of membrane remodeling, cytoskeletal reorganization, and integration of growth factor and stress signaling. This transition is intrinsically stress-sensitive, as rapid membrane deformation and structural reorganization transiently increase susceptibility to ionic imbalance, Ca²⁺ influx, and oxidative perturbations [

11,

39]. Aging exacerbates these constraints through sustained oxidative stress, chronic inflammatory signaling, and altered extracellular matrix mechanics, thereby reducing tolerance to activation-associated perturbations [

6,

8,

9].

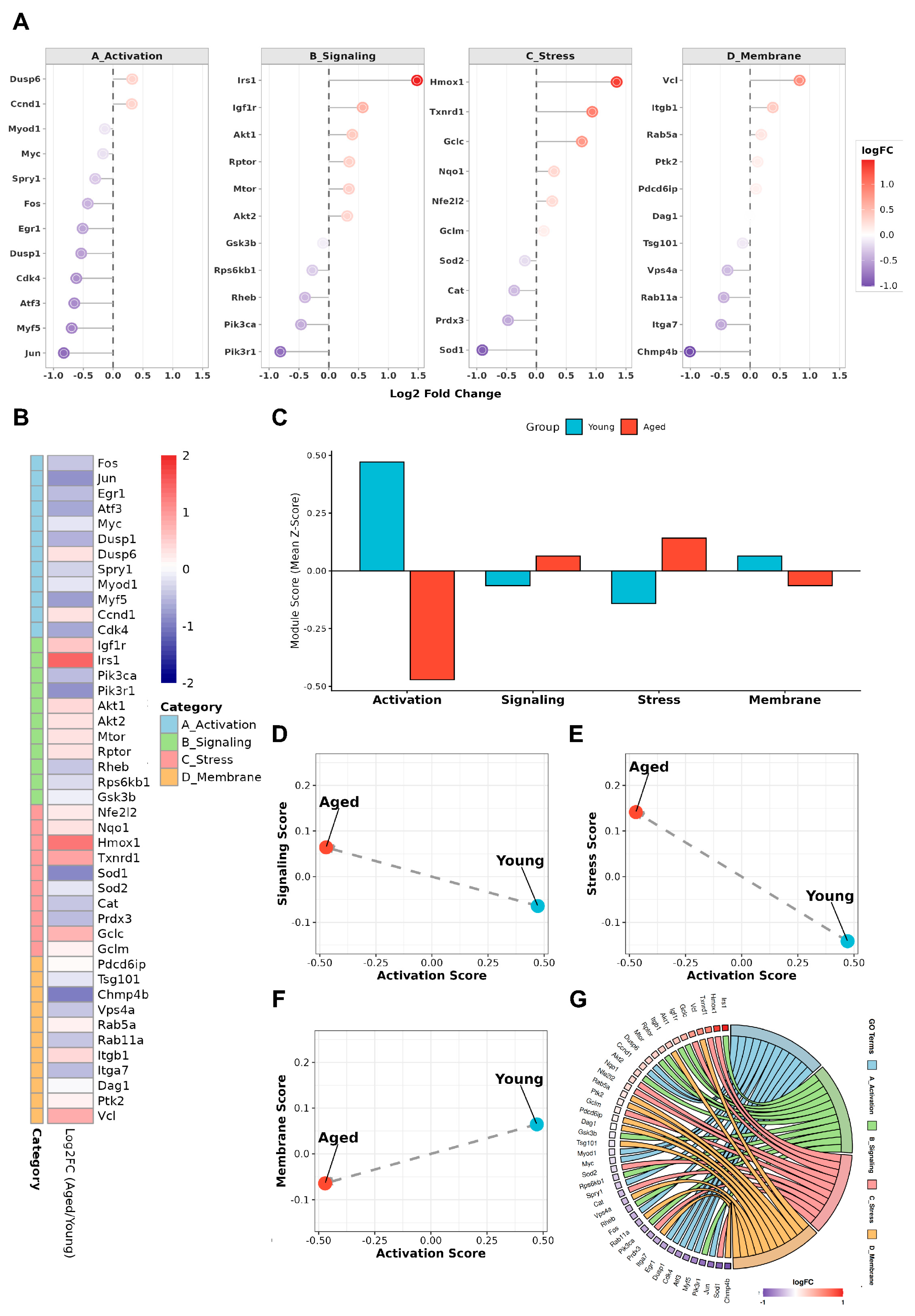

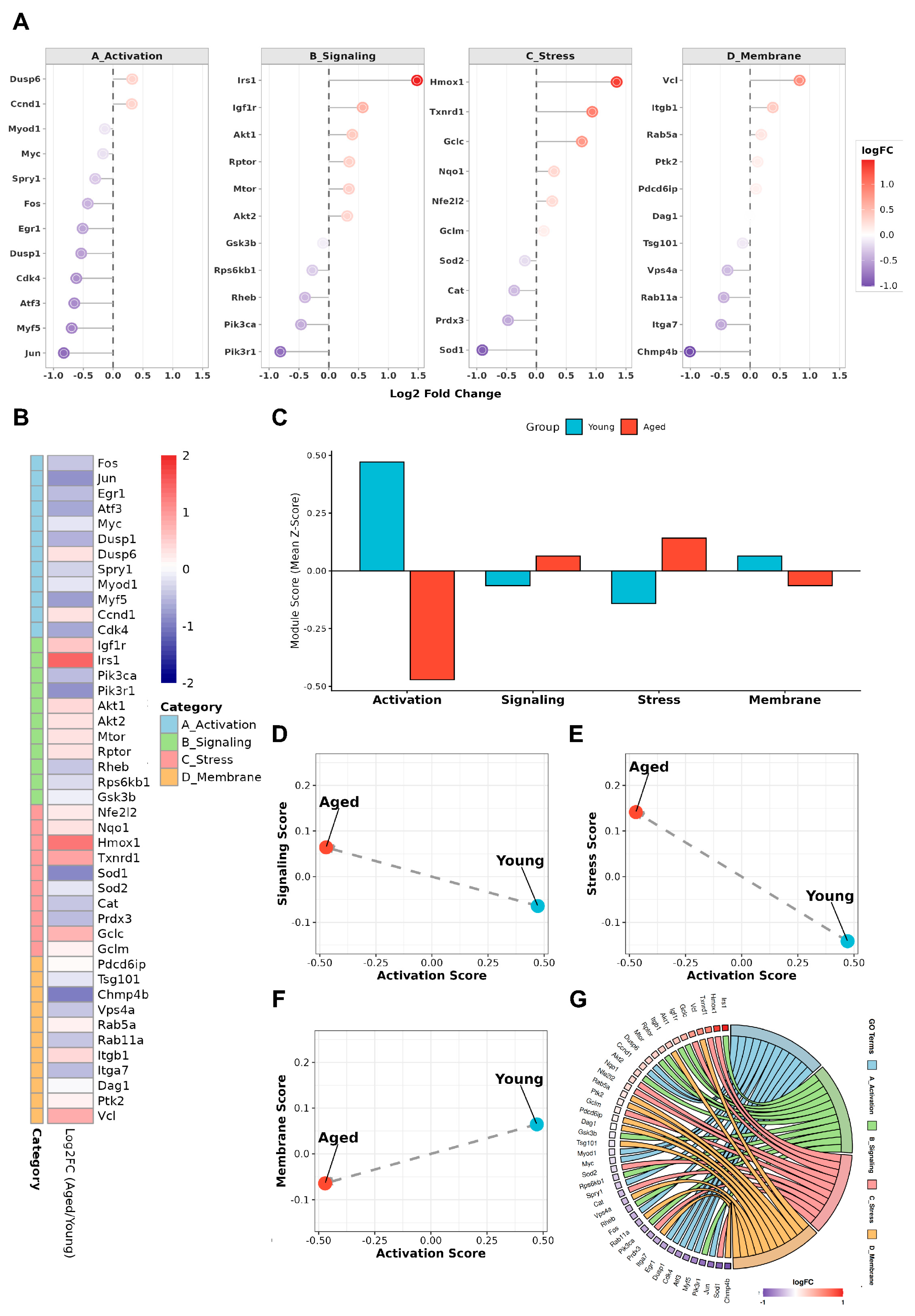

To assess whether aging alters the balance of processes supporting early activation, we reanalyzed the GSE126665 dataset using predefined, functionally anchored gene modules rather than individual differentially expressed genes [

34]. These modules capture coordinated programs relevant to activation competence, including immediate early activation responses, membrane-associated remodeling, intrinsic stress buffering, and growth factor– and MG53-related signaling. Aged satellite cells exhibited a coordinated shift in module usage (

Figure 3A–G), characterized by reduced activation- and membrane-remodeling programs and relative enrichment of stress-response and MG53-associated signaling modules.

Across samples, activation- and membrane-remodeling scores were inversely related to stress- and signaling-associated scores, indicating that aged satellite cells initiate early activation under conditions dominated by elevated stress rather than efficient execution of activation-supportive remodeling. Under such conditions, reduced membrane stabilization is expected to amplify stress signaling through increased susceptibility to Ca²⁺ influx and secondary oxidative cascades during activation [

40,

41]. Thus, activation failure in aged satellite cells reflects a stress-biased imbalance that disrupts the coordination and timing of early activation, rather than a generalized loss of myogenic capacity.

4.3. MG53 as a Permissive Regulator at the Early Activation Checkpoint

The reciprocal patterns observed in

Figure 3 indicate that early activation failure in aged muscle does not reflect loss of myogenic fate programs, but rather instability of the cellular conditions required for high-fidelity activation. MG53 is best viewed as a permissive regulator that limits damage amplification and signaling noise during the quiescence-to-activation transition, rather than as a direct determinant of lineage commitment. Its established roles in stress buffering, inflammatory restraint, and membrane stabilization align with constraints that are particularly acute during early activation.

4.3.1. MG53-Mediated Buffering of Oxidative and Mitochondrial Stress During Early Activation

Early satellite cell activation imposes acute oxidative and metabolic demands driven by rapid membrane remodeling, transient Ca²⁺ flux, and increased mitochondrial activity prior to cell-cycle entry. These processes render satellite cells particularly vulnerable to secondary oxidative stress during the activation interval. Consistent with this vulnerability, multiple studies have shown that MG53 preserves cellular integrity under oxidative challenge by limiting damage propagation and supporting mitochondrial and membrane-associated homeostasis [

42,

43,

44]. In cardiomyocytes and skeletal muscle, MG53 attenuates reactive oxygen species–induced injury, preserves mitochondrial membrane potential, and suppresses downstream cell death pathways under ischemic or oxidative stress conditions [

43,

45]. Such stress-buffering capacity is therefore well positioned to increase tolerance to activation-associated oxidative perturbations, stabilizing early activation without directly instructing downstream fate specification.

4.3.2. MG53 Modulation of Inflammatory Signaling and Stress Amplification

The aged muscle niche is characterized by chronic low-grade inflammation that intersects with early satellite cell activation to amplify stress signaling and compromise activation fidelity. Consistent with a role in stress containment, emerging evidence indicates that MG53 can attenuate inflammatory signal propagation by modulating innate immune–associated pathways [

17]. Mechanistic studies further show that MG53 limits excessive interferon-β production and inflammatory cytokine release by regulating ryanodine receptor–dependent Ca²⁺ handling and downstream stress signaling cascades, thereby constraining secondary amplification of inflammatory stress [

17,

18].

These actions place MG53 upstream of transcriptional fate programs, acting instead on the signaling environment in which early activation occurs. In vivo administration of recombinant MG53 has been shown to reduce inflammation-associated tissue damage across diverse stress contexts, including viral infection, ischemia–reperfusion injury, and sterile tissue stress [

46,

47]. Although direct evidence for MG53-mediated inflammatory regulation in satellite cells remains limited, these findings support a model in which MG53 contributes to limiting inflammatory noise during early activation, thereby preventing stress-dominated signaling states that destabilize the timing and coordination of activation.

4.3.3. MG53-Dependent Membrane Stabilization at the Activation Checkpoint

Membrane integrity constitutes a critical physical constraint during early satellite cell activation, when cells undergo rapid shape change, adhesion remodeling, and cytoskeletal reorganization. Even modest membrane perturbations at this stage can amplify Ca²⁺ influx and oxidative signaling, biasing activation toward stress-dominated trajectories. Seminal studies identified MG53 as a nucleator of membrane repair complexes following mechanical or oxidative membrane disruption [

14,

15], and subsequent work demonstrated that exogenous MG53 enhances membrane resilience and limits damage propagation across ischemic, mechanical, and inflammatory injury contexts [

19,

48].

At the activation checkpoint, insufficient membrane stabilization is therefore expected to reinforce Ca²⁺-dependent and oxidative stress signaling, further destabilizing activation execution. By constraining membrane-associated damage propagation, MG53 is well positioned to stabilize the physical execution of early activation, preserving the coordination required for productive progression without directly enforcing lineage outcomes. Together, these observations position MG53 as a context-dependent, permissive regulator operating at the early activation checkpoint to support activation fidelity under stress.

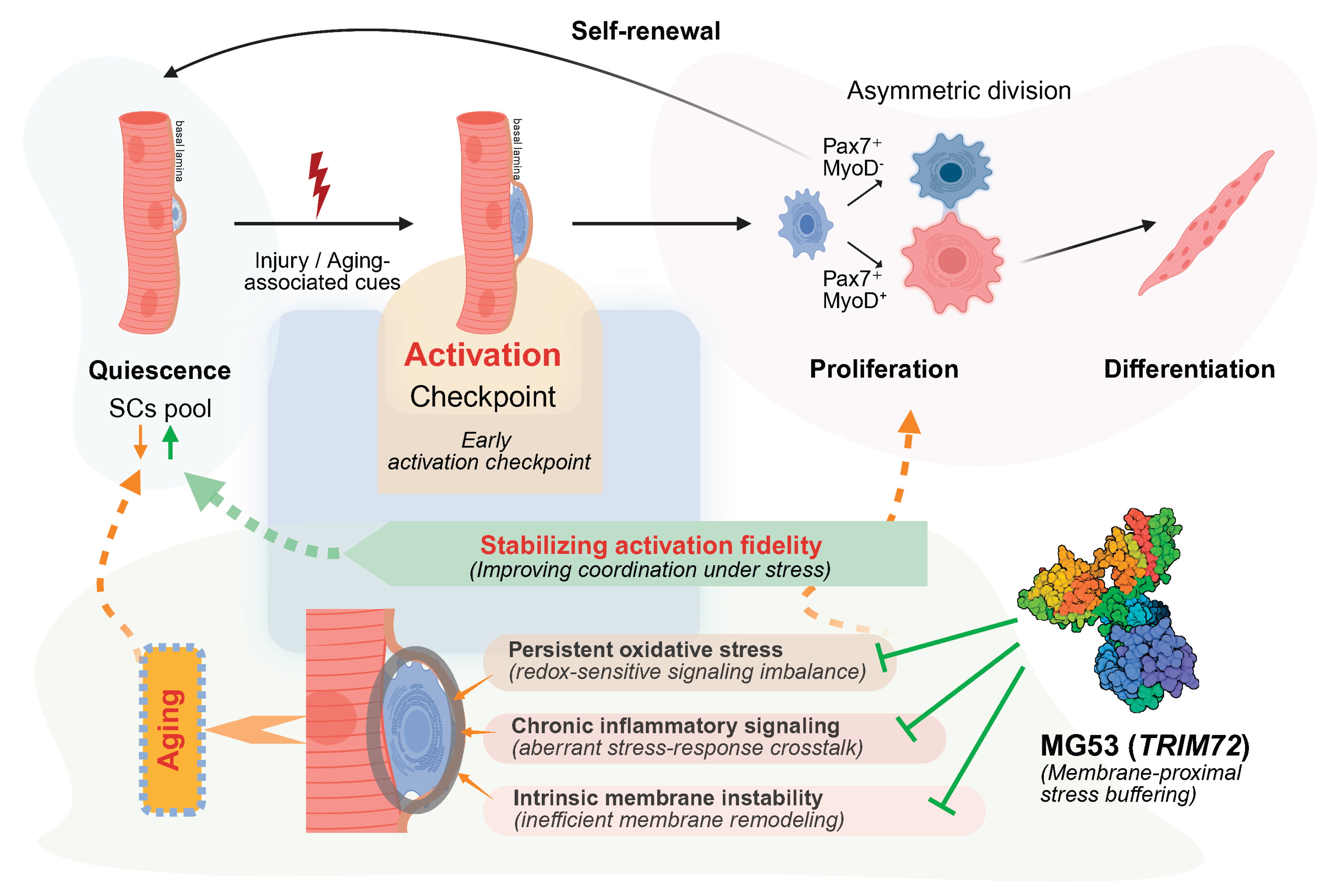

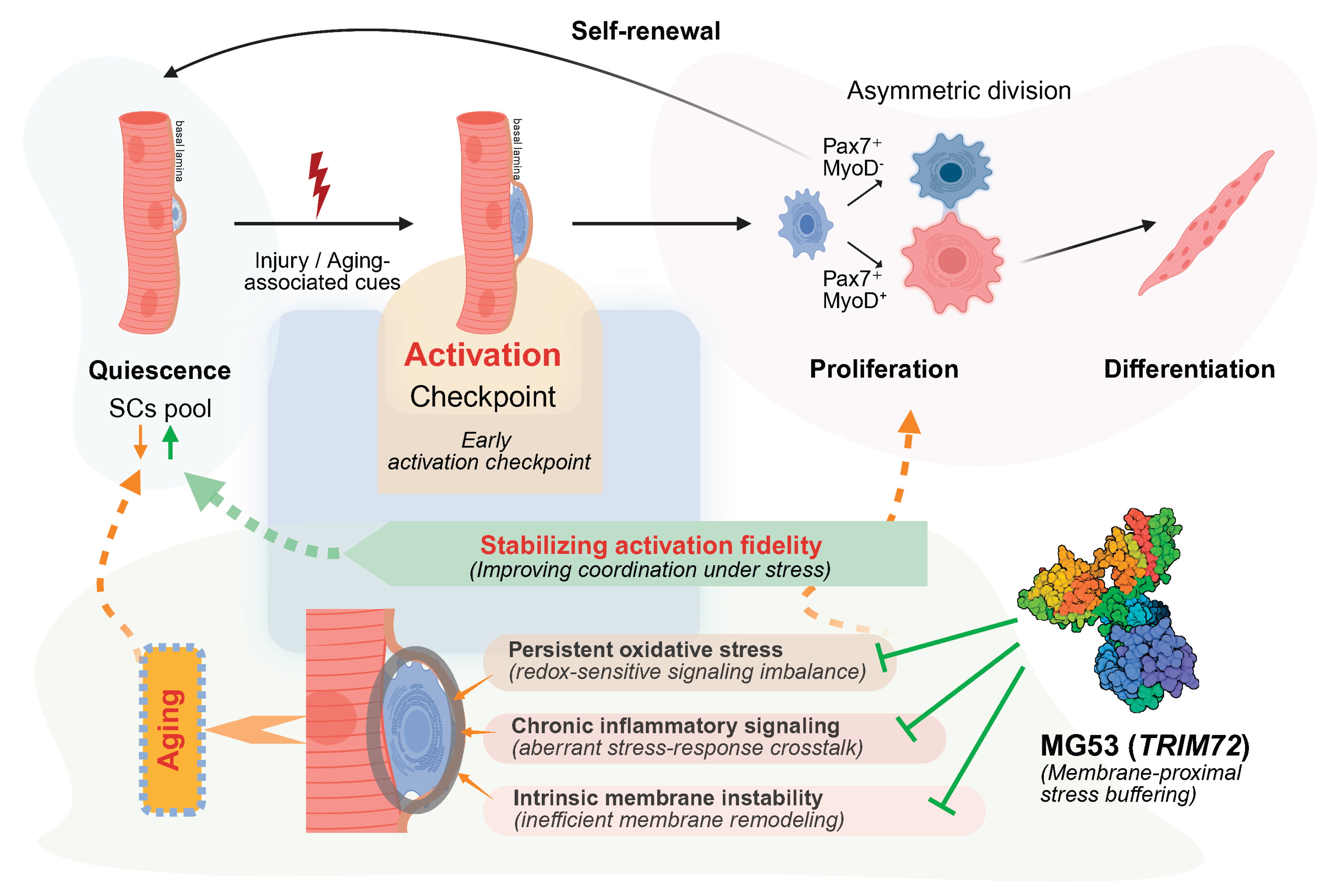

4.4. Early Activation Fidelity as a Determinant of Regenerative Aging

Age-associated decline in skeletal muscle regeneration is best explained not by a uniform loss of myogenic programs, but by a progressive reduction in fidelity at the early activation checkpoint [

3,

25] (

Figure 4). Although proliferative and differentiation programs often remain accessible, instability during the quiescence-to-activation transition disrupts the coordination and timing required for sustained regenerative output [

9].

Early activation imposes substantial organizational demands on satellite cells, requiring tightly coordinated membrane remodeling, cytoskeletal reorganization, metabolic priming, and signal integration within a rapidly changing niche [

11,

12]. Aging selectively intensifies oxidative, inflammatory, and mechanical stress during this phase, when tolerance is inherently limited [

26]. Consequently, satellite cells are more likely to enter delayed or poorly synchronized activation trajectories that impair asymmetric division and long-term self-renewal, even when downstream myogenic programs remain intact [

6,

9,

23].

Within this view, MG53 and related factors do not act as lineage-specifying regulators, but as permissive stabilizers that limit damage amplification and signaling noise during early activation [

15,

20,

40]. By supporting the fidelity of the quiescence-to-activation transition rather than directing fate choice, these mechanisms increase the likelihood that satellite cells successfully traverse the activation checkpoint under stress. This perspective helps explain why interventions focused solely on enhancing proliferation or differentiation often yield limited benefit in aged muscle [

6,

9,

25]. Increased proliferative output in aging frequently reflects compensatory activation of a restricted subset of satellite cells and is accompanied by impaired asymmetric division and accelerated stem cell pool attrition, rather than durable restoration of regenerative capacity [

6,

9]. When instability originates upstream at the activation checkpoint, downstream programs unfold within a distorted temporal and signaling context, constraining the efficacy of late-stage interventions [

8]. In contrast, preserving early activation fidelity targets the primary bottleneck through which regenerative potential must pass [

25].

By centering regenerative aging on the quality of early activation,

Figure 4 integrates niche-derived stress, intrinsic execution capacity, and permissive stabilizers into a unified framework in which coordination under stress—rather than maximal output—emerges as the principal constraint on stem cell–mediated regeneration.

5. Implications for Aged Muscle Regeneration and Therapeutic Perspectives

Reframing age-associated regenerative decline as a failure of stress-limited early activation, rather than a uniform loss of myogenic capacity, has important therapeutic implications for aged skeletal muscle [

5,

13,

25]. If instability at the quiescence-to-activation transition represents the dominant bottleneck, strategies focused primarily on enhancing downstream proliferation or differentiation are unlikely to restore durable regeneration and may instead accelerate stem cell exhaustion by repeatedly engaging a restricted subset of satellite cells capable of traversing early activation [

6,

8,

9].

This perspective shifts therapeutic focus toward stabilizing the activation window itself—a brief but vulnerable phase characterized by membrane deformation, cytoskeletal remodeling, and rapid signaling reprogramming prior to cell-cycle entry [

11]. Within this context, MG53 emerges as a candidate stress-buffering factor whose established roles in membrane repair and redox-sensitive damage control may constrain amplification of oxidative, inflammatory, and mechanically induced stress during early activation [

15,

20,

40,

41,

42,

43,

44].

Importantly, any regenerative benefit conferred by MG53 is unlikely to arise from sustained enhancement of myogenic signaling [

37,

38]. Rather, its predicted value lies in transiently improving the timing and execution fidelity of early activation. This distinction carries practical therapeutic implications. Although recombinant MG53 provides tissue protection across multiple injury models [

14,

17], application in aged muscle would likely require precise temporal control and muscle-restricted exposure to minimize potential interference with insulin/IGF signaling and systemic metabolic regulation [

19,

37,

38,

39].

Finally, while circulating MG53 has been explored as a biomarker of tissue stress and regenerative capacity [

19], its relevance to muscle aging is more plausibly interpreted as a readout of global membrane stress burden rather than a direct indicator of satellite cell competence [

14]. Together, these considerations position MG53 not as a broadly pro-proliferative agent, but as a context-dependent modulator of early activation stability whose therapeutic potential in aged muscle lies in preserving regenerative quality rather than amplifying regenerative quantity.

6. Open Questions and Future Directions

Despite increasing interest in early satellite cell activation as a vulnerable stage in aged muscle regeneration, several important questions remain.

First, it is still unclear where and how MG53 acts during early activation. MG53 may function within satellite cells themselves, act indirectly through myofibers or niche components, or influence activation through interactions between these compartments. Clarifying the primary site and mode of MG53 action will be important for understanding its role in regeneration and for guiding therapeutic strategies.

Second, early activation remains poorly defined in practical terms. This phase is often inferred from later markers of proliferation or differentiation, yet it likely includes a specific sequence of membrane remodeling, cytoskeletal changes, and stress signaling that occurs before cell-cycle entry. Approaches that resolve these events over time and across modalities will be needed to distinguish true activation from quiescence exit or early proliferation, and to identify features that predict successful regeneration.

Finally, it remains uncertain whether improving early activation is sufficient to enhance regeneration without compromising long-term stem cell maintenance. How changes in activation dynamics affect asymmetric division, self-renewal, and cumulative proliferative history have not been fully addressed. Answering these questions will be essential for evaluating whether stabilizing early activation can provide durable benefit in aged muscle.

7. Conclusions

Early satellite cell activation represents a critical and stress-sensitive step in skeletal muscle regeneration that is selectively destabilized with aging. Rather than reflecting a global loss of myogenic potential, age-associated regenerative decline is better explained by reduced fidelity during the quiescence-to-activation transition, when cells must coordinate membrane remodeling, stress adaptation, and signaling integration under increased burden. Within this view, MG53 is most plausibly positioned not as a fate-determining factor, but as a permissive regulator that supports the execution of early activation by limiting damage amplification and preserving coordination under stress. Although key mechanistic questions remain, this perspective underscores activation fidelity—rather than downstream proliferative output—as a central determinant of regenerative capacity in aging skeletal muscle.

Author Contributions

Y.X. and J.W. ZS contributed equally to this work and jointly conceptualized the review. Y.X. prepared the initial draft of the manuscript. J.W.ZS performed the data analysis and contributed to data interpretation. H.Z supervised the project and provided overall conceptual guidance. Z.Z, P.C, U.A, K.S., S.L., Z.Y., B.A.W. and T.M.P. contributed to critical revision of the manuscript. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This review was funded by the National Institutes of Health (NIH) grants AG071676, AR067766, and HL153876, and by the American Heart Association (AHA) grant 23TPA1142638.

Data Availability Statement

This review includes secondary analyses of publicly available datasets cited in the manuscript. The code used for data processing and analysis is publicly available at

https://github.com/jethro-wang-zs/MG53_on_MuSCs. No new primary data were generated in this review.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Fu, X.; Wang, H.; Hu, P. Stem Cell Activation in Skeletal Muscle Regeneration. Cell Mol Life Sci 2015, 72, 1663–1677. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mauro, A. Satellite Cell of Skeletal Muscle Fibers. J Biophys Biochem Cytol 1961, 9, 493–495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Almada, A.E.; Wagers, A.J. Molecular Circuitry of Stem Cell Fate in Skeletal Muscle Regeneration, Ageing and Disease. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol 2016, 17, 267–279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brack, A.S.; Rando, T.A. Tissue-Specific Stem Cells: Lessons from the Skeletal Muscle Satellite Cell. Cell Stem Cell 2012, 10, 504–514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Arpke, R.W.; Shams, A.S.; Collins, B.C.; Larson, A.A.; Lu, N.; Lowe, D.A.; Kyba, M. Preservation of Satellite Cell Number and Regenerative Potential with Age Reveals Locomotory Muscle Bias. Skelet Muscle 2021, 11, 22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bernet, J.D.; Doles, J.D.; Hall, J.K.; Kelly Tanaka, K.; Carter, T.A.; Olwin, B.B. P38 MAPK Signaling Underlies a Cell-Autonomous Loss of Stem Cell Self-Renewal in Skeletal Muscle of Aged Mice. Nat Med 2014, 20, 265–271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kimmel, J.C.; Hwang, A.B.; Scaramozza, A.; Marshall, W.F.; Brack, A.S. Aging Induces Aberrant State Transition Kinetics in Murine Muscle Stem Cells. Development 2020, 147, dev183855. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cosgrove, B.D.; Gilbert, P.M.; Porpiglia, E.; Mourkioti, F.; Lee, S.P.; Corbel, S.Y.; Llewellyn, M.E.; Delp, S.L.; Blau, H.M. Rejuvenation of the Muscle Stem Cell Population Restores Strength to Injured Aged Muscles. Nat Med 2014, 20, 255–264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sousa-Victor, P.; Gutarra, S.; García-Prat, L.; Rodriguez-Ubreva, J.; Ortet, L.; Ruiz-Bonilla, V.; Jardí, M.; Ballestar, E.; González, S.; Serrano, A.L.; et al. Geriatric Muscle Stem Cells Switch Reversible Quiescence into Senescence. Nature 2014, 506, 316–321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodgers, J.T.; King, K.Y.; Brett, J.O.; Cromie, M.J.; Charville, G.W.; Maguire, K.K.; Brunson, C.; Mastey, N.; Liu, L.; Tsai, C.-R.; et al. mTORC1 Controls the Adaptive Transition of Quiescent Stem Cells from G0 to GAlert. Nature 2014, 510, 393–396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Machado, L.; de Lima, J.E.; Fabre, O.; Proux, C.; Legendre, R.; Szegedi, A.; Varet, H.; Ingerslev, L.R.; Barrès, R.; Relaix, F.; et al. In Situ Fixation Redefines Quiescence and Early Activation of Skeletal Muscle Stem Cells. Cell Reports 2017, 21, 1982–1993. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yin, H.; Price, F.; Rudnicki, M.A. Satellite Cells and the Muscle Stem Cell Niche. Physiological Reviews 2013, 93, 23–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Muñoz-Cánoves, P.; Neves, J.; Sousa-Victor, P. Understanding Muscle Regenerative Decline with Aging: New Approaches to Bring Back Youthfulness to Aged Stem Cells. FEBS J 2020, 287, 406–416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Weisleder, N.; Takizawa, N.; Lin, P.; Wang, X.; Cao, C.; Zhang, Y.; Tan, T.; Ferrante, C.; Zhu, H.; Chen, P.-J.; et al. Recombinant MG53 Protein Modulates Therapeutic Cell Membrane Repair in Treatment of Muscular Dystrophy. Sci Transl Med 2012, 4, 139ra85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cai, C.; Masumiya, H.; Weisleder, N.; Matsuda, N.; Nishi, M.; Hwang, M.; Ko, J.-K.; Lin, P.; Thornton, A.; Zhao, X.; et al. MG53 Nucleates Assembly of Cell Membrane Repair Machinery. Nat Cell Biol 2009, 11, 56–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cai, C.; Masumiya, H.; Weisleder, N.; Pan, Z.; Nishi, M.; Komazaki, S.; Takeshima, H.; Ma, J. MG53 Regulates Membrane Budding and Exocytosis in Muscle Cells. J Biol Chem 2009, 284, 3314–3322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Li, X.; Ong, H.; Tan, T.; Park, K.H.; Bian, Z.; Zou, X.; Haggard, E.; Janssen, P.M.; Merritt, R.E.; et al. MG53 Suppresses NF-κB Activation to Mitigate Age-Related Heart Failure. JCI Insight 2021, 6, e148375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sermersheim, M.; Kenney, A.D.; Lin, P.-H.; McMichael, T.M.; Cai, C.; Gumpper, K.; Adesanya, T.M.A.; Li, H.; Zhou, X.; Park, K.-H.; et al. MG53 Suppresses Interferon-β and Inflammation via Regulation of Ryanodine Receptor-Mediated Intracellular Calcium Signaling. Nat Commun 2020, 11, 3624. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bian, Z.; Wang, Q.; Zhou, X.; Tan, T.; Park, K.H.; Kramer, H.F.; McDougal, A.; Laping, N.J.; Kumar, S.; Adesanya, T.M.A.; et al. Sustained Elevation of MG53 in the Bloodstream Increases Tissue Regenerative Capacity without Compromising Metabolic Function. Nat Commun 2019, 10, 4659. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hwang, M.; Ko, J.-K.; Weisleder, N.; Takeshima, H.; Ma, J. Redox-Dependent Oligomerization through a Leucine Zipper Motif Is Essential for MG53-Mediated Cell Membrane Repair. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol 2011, 301, C106–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- CHARGÉ, S.B.P.; RUDNICKI, M.A. Cellular and Molecular Regulation of Muscle Regeneration. Physiological Reviews 2004, 84, 209–238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheung, T.H.; Quach, N.L.; Charville, G.W.; Liu, L.; Park, L.; Edalati, A.; Yoo, B.; Hoang, P.; Rando, T.A. Maintenance of Muscle Stem-Cell Quiescence by microRNA-489. Nature 2012, 482, 524–528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kuang, S.; Kuroda, K.; Grand, F.L.; Rudnicki, M.A. Asymmetric Self-Renewal and Commitment of Satellite Stem Cells in Muscle. Cell 2007, 129, 999–1010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Evano, B.; Khalilian, S.; Carrou, G.L.; Almouzni, G.; Tajbakhsh, S. Dynamics of Asymmetric and Symmetric Divisions of Muscle Stem Cells In Vivo and on Artificial Niches. Cell Reports 2020, 30, 3195–3206.e7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Blau, H.M.; Cosgrove, B.D.; Ho, A.T.V. The Central Role of Muscle Stem Cells in Regenerative Failure with Aging. Nat Med 2015, 21, 854–862. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chakkalakal, J.V.; Jones, K.M.; Basson, M.A.; Brack, A.S. The Aged Niche Disrupts Muscle Stem Cell Quiescence. Nature 2012, 490, 355–360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Velthoven, C.T.J.; de Morree, A.; Egner, I.M.; Brett, J.O.; Rando, T.A. Transcriptional Profiling of Quiescent Muscle Stem Cells In Vivo. Cell Reports 2017, 21, 1994–2004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dell’Orso, S.; Juan, A.H.; Ko, K.-D.; Naz, F.; Perovanovic, J.; Gutierrez-Cruz, G.; Feng, X.; Sartorelli, V. Single Cell Analysis of Adult Mouse Skeletal Muscle Stem Cells in Homeostatic and Regenerative Conditions. Development 2019, 146, dev174177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lukjanenko, L.; Jung, M.J.; Hegde, N.; Perruisseau-Carrier, C.; Migliavacca, E.; Rozo, M.; Karaz, S.; Jacot, G.; Schmidt, M.; Li, L.; et al. Loss of Fibronectin from the Aged Stem Cell Niche Affects the Regenerative Capacity of Skeletal Muscle in Mice. Nat Med 2016, 22, 897–905. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brack, A.S.; Muñoz-Cánoves, P. The Ins and Outs of Muscle Stem Cell Aging. Skelet Muscle 2016, 6, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pala, F.; Di Girolamo, D.; Mella, S.; Yennek, S.; Chatre, L.; Ricchetti, M.; Tajbakhsh, S. Distinct Metabolic States Govern Skeletal Muscle Stem Cell Fates during Prenatal and Postnatal Myogenesis. J Cell Sci 2018, 131, jcs212977. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Oprescu, S.N.; Yue, F.; Qiu, J.; Brito, L.F.; Kuang, S. Temporal Dynamics and Heterogeneity of Cell Populations during Skeletal Muscle Regeneration. iScience 2020, 23, 100993. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moyle, L.A.; Cheng, R.Y.; Liu, H.; Davoudi, S.; Ferreira, S.A.; Nissar, A.A.; Sun, Y.; Gentleman, E.; Simmons, C.A.; Gilbert, P.M. Three-Dimensional Niche Stiffness Synergizes with Wnt7a to Modulate the Extent of Satellite Cell Symmetric Self-Renewal Divisions. Mol Biol Cell 2020, 31, 1703–1713. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Uezumi, A.; Ikemoto-Uezumi, M.; Zhou, H.; Kurosawa, T.; Yoshimoto, Y.; Nakatani, M.; Hitachi, K.; Yamaguchi, H.; Wakatsuki, S.; Araki, T.; et al. Mesenchymal Bmp3b Expression Maintains Skeletal Muscle Integrity and Decreases in Age-Related Sarcopenia. J Clin Invest 2021, 131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, S.H.; Han, J.; Jeong, B.-C.; Song, J.H.; Jang, S.H.; Jeong, H.; Kim, B.H.; Ko, Y.-G.; Park, Z.-Y.; Lee, K.E.; et al. Structure and Activation of the RING E3 Ubiquitin Ligase TRIM72 on the Membrane. Nat Struct Mol Biol 2023, 30, 1695–1706. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, Y.; Ding, L.; Li, Z.; Zhou, C. Structural Basis for TRIM72 Oligomerization during Membrane Damage Repair. Nat Commun 2023, 14, 1555. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, C.S.; Yi, J.-S.; Jung, S.-Y.; Kim, B.-W.; Lee, N.-R.; Choo, H.-J.; Jang, S.-Y.; Han, J.; Chi, S.-G.; Park, M.; et al. TRIM72 Negatively Regulates Myogenesis via Targeting Insulin Receptor Substrate-1. Cell Death Differ 2010, 17, 1254–1265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yi, J.-S.; Park, J.S.; Ham, Y.-M.; Nguyen, N.; Lee, N.-R.; Hong, J.; Kim, B.-W.; Lee, H.; Lee, C.-S.; Jeong, B.-C.; et al. MG53-Induced IRS-1 Ubiquitination Negatively Regulates Skeletal Myogenesis and Insulin Signalling. Nat Commun 2013, 4, 2354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brack, A.S.; Rando, T.A. Intrinsic Changes and Extrinsic Influences of Myogenic Stem Cell Function during Aging. Stem Cell Rev 2007, 3, 226–237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cooper, S.T.; McNeil, P.L. Membrane Repair: Mechanisms and Pathophysiology. Physiol Rev 2015, 95, 1205–1240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McNeil, P.L.; Steinhardt, R.A. Plasma Membrane Disruption: Repair, Prevention, Adaptation. Annu Rev Cell Dev Biol 2003, 19, 697–731. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duann, P.; Li, H.; Lin, P.; Tan, T.; Wang, Z.; Chen, K.; Zhou, X.; Gumpper, K.; Zhu, H.; Ludwig, T.; et al. MG53-Mediated Cell Membrane Repair Protects against Acute Kidney Injury. Sci Transl Med 2015, 7, 279ra36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gumpper-Fedus, K.; Park, K.H.; Ma, H.; Zhou, X.; Bian, Z.; Krishnamurthy, K.; Sermersheim, M.; Zhou, J.; Tan, T.; Li, L.; et al. MG53 Preserves Mitochondrial Integrity of Cardiomyocytes during Ischemia Reperfusion-Induced Oxidative Stress. Redox Biol 2022, 54, 102357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Q.; Park, K.H.; Geng, B.; Chen, P.; Yang, C.; Jiang, Q.; Yi, F.; Tan, T.; Zhou, X.; Bian, Z.; et al. MG53 Inhibits Necroptosis Through Ubiquitination-Dependent RIPK1 Degradation for Cardiac Protection Following Ischemia/Reperfusion Injury. Front. Cardiovasc. Med. 2022, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, H.; Zhou, X.; Wang, X.; Wu, J.; Gumpper, K.; Tan, T.; Adesanya, T.A.; Yang, C.; Zheng, Y.; Chandler, H.; et al. MG53 Interacts with Cardiolipin to Protect Mitochondria from Ischemia-Reperfusion Induced Oxidative Stress. Biophysical Journal 2017, 112, 102a. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kenney, A.D.; Aron, S.L.; Gilbert, C.; Kumar, N.; Chen, P.; Eddy, A.; Zhang, L.; Zani, A.; Vargas-Maldonado, N.; Speaks, S.; et al. Influenza Virus Replication in Cardiomyocytes Drives Heart Dysfunction and Fibrosis. Sci Adv 2022, 8, eabm5371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kenney, A.D.; Li, Z.; Bian, Z.; Zhou, X.; Li, H.; Whitson, B.A.; Tan, T.; Cai, C.; Ma, J.; Yount, J.S. Recombinant MG53 Protein Protects Mice from Lethal Influenza Virus Infection. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2021, 203, 254–257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, H.; Hou, J.; Roe, J.L.; Park, K.H.; Tan, T.; Zheng, Y.; Li, L.; Zhang, C.; Liu, J.; Liu, Z.; et al. Amelioration of Ischemia-Reperfusion-Induced Muscle Injury by the Recombinant Human MG53 Protein. Muscle Nerve 2015, 52, 852–858. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Figure 1.

Canonical and age-associated shifts in satellite cell activation dynamics and fate progression. (A) Under young or homeostatic conditions, skeletal muscle satellite cells (MuSCs) reside in a quiescent Pax7⁺ state beneath the basal lamina. Upon injury, MuSCs undergo timely activation with MyoD induction, enter the cell cycle, and proliferate. Balanced asymmetric divisions generate differentiated myogenic progeny while preserving the stem cell pool through self-renewal. (B) In aged muscle, satellite cell numbers are relatively preserved, but the transition from quiescence to productive activation is delayed and poorly coordinated. Aging-associated stress prolongs early activation and reduces the efficiency of progression toward proliferation. This disruption biases division dynamics, leading to reduced asymmetric self-renewal and compromised regenerative efficiency. Created in BioRender. Lee, S. (2026) https://BioRender.com/4kcp6k1.

Figure 1.

Canonical and age-associated shifts in satellite cell activation dynamics and fate progression. (A) Under young or homeostatic conditions, skeletal muscle satellite cells (MuSCs) reside in a quiescent Pax7⁺ state beneath the basal lamina. Upon injury, MuSCs undergo timely activation with MyoD induction, enter the cell cycle, and proliferate. Balanced asymmetric divisions generate differentiated myogenic progeny while preserving the stem cell pool through self-renewal. (B) In aged muscle, satellite cell numbers are relatively preserved, but the transition from quiescence to productive activation is delayed and poorly coordinated. Aging-associated stress prolongs early activation and reduces the efficiency of progression toward proliferation. This disruption biases division dynamics, leading to reduced asymmetric self-renewal and compromised regenerative efficiency. Created in BioRender. Lee, S. (2026) https://BioRender.com/4kcp6k1.

Figure 2.

Stage-selective attenuation of early activation–associated transcriptional programs in aged satellite cells. (A) Radar plot showing relative gene set activity scores for quiescence, activation, proliferation, and differentiation programs in satellite cells isolated from young and aged mouse skeletal muscle (GSE126665). Compared with young cells, aged satellite cells show reduced quiescence- and activation-associated transcriptional activity, while proliferation- and differentiation-associated programs are relatively preserved. (B) Mean log₂ fold changes (aged vs. young) of stage-specific gene sets across the satellite cell regenerative trajectory. Quiescence and activation programs are selectively attenuated in aged cells, whereas proliferation and differentiation programs show relative maintenance or enrichment. (C) Distribution of stage-specific gene set activity scores across individual samples. Aged satellite cells display lower activation-associated scores with increased inter-sample variability, indicating less stable or less coordinated entry into early activation, while downstream transcriptional programs remain detectable in a subset of cells.

Figure 2.

Stage-selective attenuation of early activation–associated transcriptional programs in aged satellite cells. (A) Radar plot showing relative gene set activity scores for quiescence, activation, proliferation, and differentiation programs in satellite cells isolated from young and aged mouse skeletal muscle (GSE126665). Compared with young cells, aged satellite cells show reduced quiescence- and activation-associated transcriptional activity, while proliferation- and differentiation-associated programs are relatively preserved. (B) Mean log₂ fold changes (aged vs. young) of stage-specific gene sets across the satellite cell regenerative trajectory. Quiescence and activation programs are selectively attenuated in aged cells, whereas proliferation and differentiation programs show relative maintenance or enrichment. (C) Distribution of stage-specific gene set activity scores across individual samples. Aged satellite cells display lower activation-associated scores with increased inter-sample variability, indicating less stable or less coordinated entry into early activation, while downstream transcriptional programs remain detectable in a subset of cells.

Figure 3.

Functional shifts in early activation–associated programs in aged satellite cells. (A) Dot plots showing log₂ fold changes (aged vs. young) of representative genes grouped into four functionally defined modules relevant to early satellite cell activation: immediate-early activation genes (A_Activation), growth factor and metabolic signaling pathways including MG53-associated components (B_Signaling), intrinsic stress-response programs (C_Stress), and membrane-associated remodeling and adhesion-related processes (D_Membrane). Dot size indicates statistical significance; color reflects direction and magnitude of expression change. (B) Heatmap showing gene-level expression changes within each functional module. Genes were selected based on established functional annotation and prior literature to represent core module features. (C) Module-level activity scores summarizing relative contributions of each functional category in young and aged satellite cells. Compared with young cells, aged satellite cells show reduced activation- and membrane-associated module scores, with relative enrichment of stress- and signaling-associated modules. (D–F) Pairwise comparisons of module activity scores reveal inverse relationships between activation-associated modules and stress- or signaling-associated programs, highlighting divergent shifts in early activation state between young and aged satellite cells. (G) Chord diagram illustrating cross-module gene–function relationships, emphasizing coordinated module-level changes rather than isolated gene-specific effects.

Figure 3.

Functional shifts in early activation–associated programs in aged satellite cells. (A) Dot plots showing log₂ fold changes (aged vs. young) of representative genes grouped into four functionally defined modules relevant to early satellite cell activation: immediate-early activation genes (A_Activation), growth factor and metabolic signaling pathways including MG53-associated components (B_Signaling), intrinsic stress-response programs (C_Stress), and membrane-associated remodeling and adhesion-related processes (D_Membrane). Dot size indicates statistical significance; color reflects direction and magnitude of expression change. (B) Heatmap showing gene-level expression changes within each functional module. Genes were selected based on established functional annotation and prior literature to represent core module features. (C) Module-level activity scores summarizing relative contributions of each functional category in young and aged satellite cells. Compared with young cells, aged satellite cells show reduced activation- and membrane-associated module scores, with relative enrichment of stress- and signaling-associated modules. (D–F) Pairwise comparisons of module activity scores reveal inverse relationships between activation-associated modules and stress- or signaling-associated programs, highlighting divergent shifts in early activation state between young and aged satellite cells. (G) Chord diagram illustrating cross-module gene–function relationships, emphasizing coordinated module-level changes rather than isolated gene-specific effects.

Figure 4.

Integrative model of MG53 as a permissive stabilizer of early activation fidelity in aged muscle. Schematic illustrating a stage-selective model of satellite cell dysfunction with aging and the proposed role of MG53 (TRIM72) at the early activation checkpoint. Under young or permissive conditions, satellite cells efficiently transition from quiescence through an early activation checkpoint, enabling coordinated asymmetric division, self-renewal, and productive differentiation. With aging, persistent oxidative stress, chronic inflammatory signaling, and intrinsic membrane instability increase the stress burden encountered during early activation. These stresses destabilize the coordination and timing of the activation checkpoint, reducing activation fidelity and biasing satellite cells toward delayed or inefficient activation trajectories, despite relative preservation of downstream proliferative and differentiation capacity. Within this stress-limited context, MG53 is proposed to function as a membrane-proximal, permissive stabilizer that buffers activation-associated stress and limits damage amplification and signaling noise. By improving coordination under stress rather than instructing lineage commitment, MG53 increases the likelihood of successful passage through the early activation checkpoint, thereby supporting long-term self-renewal and regenerative capacity in aged muscle. Created in BioRender. Lee, S. (2026) https://BioRender.com/s3zts0v.

Figure 4.

Integrative model of MG53 as a permissive stabilizer of early activation fidelity in aged muscle. Schematic illustrating a stage-selective model of satellite cell dysfunction with aging and the proposed role of MG53 (TRIM72) at the early activation checkpoint. Under young or permissive conditions, satellite cells efficiently transition from quiescence through an early activation checkpoint, enabling coordinated asymmetric division, self-renewal, and productive differentiation. With aging, persistent oxidative stress, chronic inflammatory signaling, and intrinsic membrane instability increase the stress burden encountered during early activation. These stresses destabilize the coordination and timing of the activation checkpoint, reducing activation fidelity and biasing satellite cells toward delayed or inefficient activation trajectories, despite relative preservation of downstream proliferative and differentiation capacity. Within this stress-limited context, MG53 is proposed to function as a membrane-proximal, permissive stabilizer that buffers activation-associated stress and limits damage amplification and signaling noise. By improving coordination under stress rather than instructing lineage commitment, MG53 increases the likelihood of successful passage through the early activation checkpoint, thereby supporting long-term self-renewal and regenerative capacity in aged muscle. Created in BioRender. Lee, S. (2026) https://BioRender.com/s3zts0v.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).