1. Introduction

The nonlinear electrical phenomenon of ferroresonance produces dangerous overvoltages that reach severe levels. Power systems face two types of voltage and current problems that result in equipment damage and operational breakdowns. It typically arises when a saturable inductance, such as a transformer, interacts with the system capacitance under specific conditions, including during switching operations or faults. The unpredictable behavior of ferroresonance produces complex system responses because its outcomes are difficult to control. The new analytical methods require complex modeling systems and detection technologies because they operate through distinct mechanisms from traditional methods.

The present-day power grid system is becoming increasingly susceptible to network failures because its evolving design introduces new points of vulnerability to ferroresonance. The implementation of renewable energy systems that use inverter-based distributed generation has led to different impedance patterns that modify power system and network resonance characteristics, and has expanded the set of operating conditions under which ferroresonance may occur. Similarly, the proliferation of underground cables, lightly loaded lines, and capacitor-rich components has added operational difficulties for predicting and preventing ferroresonance events. Traditional analytical tools, though foundational, often fall short in capturing the nonlinear magnetization dynamics, hysteresis effects, and switching-induced transients that govern ferroresonant behavior. The system needs to operate effectively in both extensive power networks and systems that experience ongoing changes. In [

1], ferroresonance was investigated in a distribution system integrated with multiple DGs and a proposed an RLC shunt limiter as an effective mitigation technique.

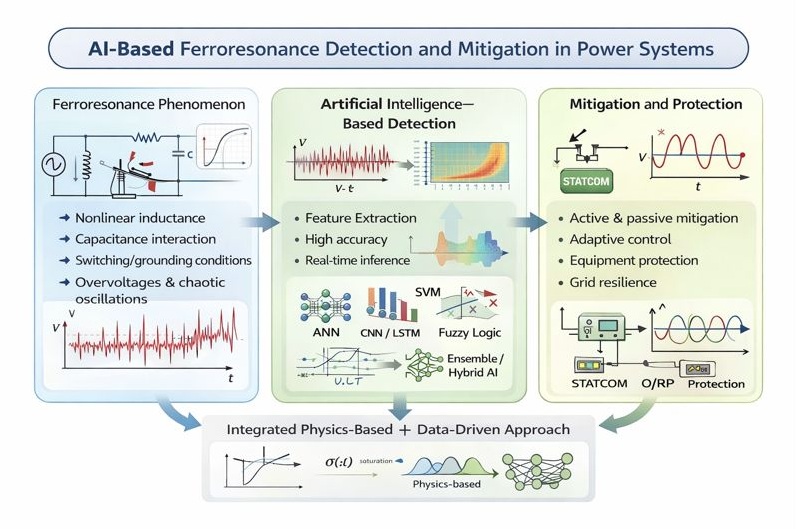

The present Artificial Intelligence (AI) research has brought about fundamental changes, opening new possibilities for solving these problems. Machine Learning (ML), Deep Learning (DL), and hybrid intelligent systems have demonstrated strong potential in identifying early signatures of ferroresonance, extracting meaningful features from complex waveforms, and improving predictive capability under uncertainty. AI-enhanced methods enable users to monitor systems in real-time while their protection systems adapt to changing system environments. The system uses advanced ML and data-driven classification methods, producing better results than conventional threshold-based and rule-based systems techniques. In addition, the deployment of AI-supported modeling frameworks improves nonlinear system modeling through their advanced capabilities. The system requires two operational functions to work properly because it must produce chaotic response patterns and demonstrate transformer behavior to achieve optimal mitigation results. The system operates different strategies that function under different grid arrangements. For instance, [

2] introduced an algorithm that demonstrates its ability to detect faults through estimated flux analysis of voltage transformers. The study investigates the occurrence of ferroresonance oscillations that affect medium-voltage networks.

The modeling of ferroresonance requires precise methods to understand its behavior and develop effective mitigation strategies. Traditional models fail to adequately represent the nonlinear dynamics involved. Recent research has used chaos theory to develop models of ferroresonance under nominal conditions, providing deeper insights into its unpredictable nature. These models allow users to create virtual scenarios, which enable them to develop improved design solutions for robust protection schemes.

Mitigation techniques for ferroresonance have evolved alongside advancements in detection and modeling. The system uses passive methods, including damping resistors and ferroresonance suppression circuits, which have been traditionally used. However, their effectiveness can be limited in complex systems. The effectiveness of damping devices in auxiliary power systems of high-voltage substations was analyzed in [

3], emphasizing the importance of proper parameter coordination for successful mitigation. Active methods, including Static Var Compensators (SVCs), have also been explored for their ability to dynamically adjust system parameters to suppress ferroresonance.

The application of AI extends beyond detection to a mitigation phase. AI algorithms can predict which circumstances will produce specific results. The system will detect ferroresonance conditions and trigger automatic preventive measures to prevent these events. For example, morphological filtering techniques have been employed to remove high-frequency components from zero-sequence currents, thereby eliminating ferroresonance events.

The research shows promising results, but existing studies remain scattered across different fields. This includes diverse modeling methodologies, numerical simulation techniques, heuristic mitigation strategies, and a growing but heterogeneous body of AI-driven detection research. The evolution of power systems toward greater reliance on renewable energy and automated control systems requires a new approach to power system protection.

This review addresses this gap by synthesizing recent advancements in ferroresonance detection and by focusing on emerging AI techniques during the last five years. The paper evaluates theoretical foundations, numerical approaches, electromagnetic transients simulation tools, and contemporary mitigation strategies, while providing a comprehensive comparative analysis of AI methodologies, including neural networks, DL, fuzzy logic, evolutionary algorithms, and hybrid systems. By integrating insights from conventional engineering analysis and cutting-edge computational intelligence, this work aims to support researchers, utilities, and protection engineers in designing more resilient, adaptive, and predictive ferroresonance countermeasures suitable for next-generation smart grids.

2. Ferroresonance Phenomenon

Ferroresonance is a unique, nonlinear resonance effect that can impact power systems. Its unusual harmonic levels and transient or steady-state overvoltages and overcurrents can pose significant risks to electrical devices [

4,

5]. It is often triggered by the interaction between nonlinear elements, such as transformers and capacitors, under specific operational conditions [

5,

6]. This uncommon, nonlinear effect can also cause unknown malfunctions. The term “Ferro-résonance,” which appeared in the literature for the first time in 1920, refers to all oscillating phenomena occurring in an electric circuit that must contain at least a nonlinear inductance (ferromagnetic and saturable), a capacitor, a sinusoidal voltage source, and an inductive circuit[

7].

Literature has different definitions for ferroresonance as [

8] definition is “an electrical resonance condition associated with the saturation of a ferromagnetic device, such as a transformer through capacitance.” Also, [

9] defines ferroresonance as “ a phenomenon usually characterized by overvoltages and irregular wave shapes and associated with the excitation of one or more saturable inductors through a capacitance in series with the inductor.”

Power systems consist of numerous saturable inductances, including power transformers, voltage measurement inductive transformers (VT), and shunt reactors, along with various capacitors such as cables, long lines, Capacitor Voltage Transformers (CVTs), series or shunt capacitor banks, voltage grading capacitors in circuit-breakers, and metal-clad substations. As a result, they can experience situations where ferroresonance may take place [

4].

2.1. Causes and Contributing Factors

Ferroresonance involves three main components: nonlinear inductance, capacitive interaction, and hysteresis effects. When the magnetic core saturates, inductance changes abruptly, which can initiate resonance [

10,

11]. Capacitive elements, such as grading and ground capacitors, interact with nonlinear inductance to create a resonant circuit. The resonance frequency depends on the specific values of inductance and capacitance [

12,

13]. Magnetic hysteresis in the transformer core introduces additional nonlinear effects that can significantly influence the stability and behavior of the ferroresonant circuit [

14,

15,

16].

Several factors can trigger ferroresonance when predisposing conditions are present. Transient events, such as circuit breaker operations, may initiate ferroresonance by producing voltage and current transients [

4]. Additionally, system configuration significantly influences the occurrence of ferroresonance. Distributed generation, ungrounded neutral systems, and certain network topologies can further increase the probability of ferroresonance [

17]. Elevated harmonic distortion within the system can intensify ferroresonance by introducing additional resonant frequencies [

18].

Nonlinear circuits exhibit two fundamentally different excitation mechanisms, as described by closed-loop system theory. One mechanism, termed soft excitation, is characterized by the gradual emergence of oscillatory behavior following minor perturbations, with oscillation amplitudes increasing smoothly from near-zero levels. The alternative mechanism, known as hard excitation, involves an abrupt initiation of oscillations. In practical power systems, particularly in medium- and high-voltage networks, ferroresonance is most often associated with this latter mechanism, in which switching events induce core saturation, triggering sustained oscillatory states [

19].

2.2. Nonlinear Magnetization Characteristic

The cores of transformers are constructed from Cold-Rolled Grain-Oriented (CRGO) silicon steel. To minimize eddy losses within the transformer core, CRGO materials are manufactured with thicknesses ranging from 0.23 mm to 0.35 mm; additionally, cold-rolled grain-oriented steel is a ferromagnetic material. The characteristic relationship between current and voltage for a voltage transformer is typically called the magnetic curve in core design, particularly in the knee region. If the core is designed with a value above the knee point, it enters saturation. Once the magnetic core becomes saturated, it displays a behavior that deviates from the calculated or anticipated characteristics, leading to unpredictable oscillations within the system. The magnetic permeability, denoted as

(where

, is shown in Equation (

1). The area, denoted as a surface S and measured in m

2, is utilized in Equation (

2), while H symbolizes magnetic field intensity and is expressed in A/m. The magnetic flux density, represented as B, is indicated in Equation (

3) and is measured in Weber/

or Tesla [

20] .

The sinusoidal current I begins at zero and rises to its maximum value I

m, while H increases directly to I, as demonstrated in Equation (

2). However, the flux density B does not rise linearly during this increase. An illustration of the hysteresis curve is presented in

Figure 1; as described, it follows the path 0A [

21]. When the current drops from I

m to 0,

follows the path AB and settles at

, known as residual flux density. Then, when the current rises from zero to –I

m, the magnetic field strength climbs to –

, and the flux density follows the path BCD, reaching the value of –B

m [

20]. The HC point, where the flux density is zero, is called the cleaning area. When the magnetic field decreases to zero along with the current, the flux density traces path DEF. When the residual current begins in the second cycle, the flux density follows path FA instead of the 0A path. This path is called the hysteresis loop. In other words, the curve does not close during the first cycle [

20,

21].

Ferroresonant phenomena in nonlinear systems may exhibit chaotic dynamics, whereby minute variations in system parameters produce disproportionately large and unpredictable changes in system response. Extensive numerical studies indicate that even slight modifications to circuit parameters or to the representation of the magnetization characteristic can yield markedly different simulation outcomes. Consequently, accurate modeling of the magnetization curve—particularly in the deep saturation region—is essential for reliable analysis of ferroresonant behavior [

19].

The magnetization characteristic can be determined through analytical modeling or experimental measurement. Numerical simulation of the magnetic circuit requires specialized software and must account for the material’s relative permeability and design-specific factors, such as boreholes, air gaps from lamination imperfections, and primary winding configuration. As a result, accurately modeling the magnetic core’s behavior remains a significant challenge [

19].

Because magnetic core behavior is complex, magnetization curves from numerical models often differ from experimental results. Therefore, direct measurement is usually preferred for characterizing the magnetization curve. However, measurement results may be affected by parasitic phenomena, which must be carefully considered [

19].

2.3. Linear Resonance and Ferroresonance Distinction

2.3.1. Linear Resonance

Ferroresonance is a nonlinear resonance effect that should not be confused with linear resonance. Although linear resonance and ferroresonance occur when the circuit’s capacitance and inductance match, their behaviors differ [

16,

20].

Imagine a resonance circuit that includes a voltage source, a capacitor, and an inductor, as shown in

Figure 2. For simplicity, resistance is not included [

16,

22]. where V

S in the voltage source, V

L is the voltage across the inductor and V

C is the voltage across the capacitor.

Presumably, inductive and capacitive reactances remain constant. In linear resonance, the voltage across the inductor depends on the current, inductance, and frequency. For the capacitor, the voltage depends on the current and is inversely related to frequency and capacitance. The voltage across the capacitor is also out of phase with the voltage across the inductor. The Equation (

5) below shows the phasor representation [

16].

The graphical representation of the voltage relationships in the circuit is illustrated in

Figure 3. The voltage relationship in equation

4 holds solely at the intersection of the capacitance and inductance lines, marked as point ’a’ in

Figure 3. The horizontal projection of this point onto the x-axis indicates the current flowing through the circuit. In contrast, the vertical projection onto the y-axis represents the voltage across the inductor [

16].

As capacitance decreases, the slope of the VC line becomes steeper. Illustrated in

Figure 3, the point where line V

C intersects with line V

L will rise (moving from point ’a’ to point ’b’), and eventually, the steepness of line V

C will match that of line V

L, represented by line

at which the resonance occurs [

16,

22].

In this linear scenario, the resonance frequency is determined by the circuit’s inductance and capacitance. Inductive reactance equal to capacitive reactance is quite unusual in a linear inductance. However, in a nonlinear inductance, such as that found in the iron core of a transformer, the likelihood of this matching is considerably greater. Determining the resonance frequency in nonlinear resonance is challenging due to multiple stable states and their transitions [

16] .

2.3.2. nonlinear Resonance(Ferroresonance)

Consider the basic LC circuit illustrated in

Figure 2, where a linear inductor is substituted with a nonlinear inductor as demonstrated in

Figure 4. The nonlinear inductance in the transformer associated with ferroresonance is saturable. The transformer’s iron core is made of a ferromagnetic material. This ferromagnetic material can retain some magnetic properties even after the magnetic field is removed [

4,

16].

Equation

4 can still be applied where supply voltage, V

S, must balance the voltage across the capacitance and inductance. However, the voltage across the inductance, in this case, is not proportional to the current but depends on the iron core’s magnetic characteristics [

23]. The inductance is written as a function of current, I. Thus, the voltage across the inductance is written as

.

Figure 5 shows how the voltage of the inductor changes. Since the iron core can become saturated, the voltage behavior has two parts: linear and saturation. In the linear part, the voltage across the inductor increases directly with the current, just like in a regular inductor. In the saturation part, the magnetic flux in the core is already fully aligned, so the voltage no longer rises much as the current increases. Here, changes in current only cause a small increase in voltage [

16].

The system capacitance variation contributes to the transient-state transition, further compounding the ferroresonance effect.

3. Ferroresonance Modeling

Due to the phenomenon’s nonlinear and complex nature, modeling ferroresonance is challenging. Accurate modeling of ferroresonance is essential for predicting and mitigating its effects. Theoretical models are crucial to understanding and analyzing ferroresonance phenomena. These models help in designing effective mitigation strategies. A necessary element of the theoretical models is the detailed core model for step-down transformers, developed to investigate ferroresonance behavior. These models account for hysteresis, eddy current effects, and remnant flux, providing insights into the impact of passive and active suppression circuits [

24]. Nonlinear inductance models are essential for analyzing ferroresonance in distribution networks. Nonlinear inductance models are used in voltage transformers (VTs) to model nonlinear inductance. These models capture the dynamic behavior of VTs and their response to system disturbances. Dynamic models for ferroresonance are generalized, nonlinear inductance models aimed at studying ferroresonance in power networks, specifically 6-35 kV networks. These models provide accurate representations of ferroresonance modes, including fundamental frequency and subharmonic resonances [

25]

Various modeling techniques have been developed to analyze and predict ferroresonance, each with strengths and limitations. The choice of modeling technique depends on the system’s complexity, the required level of accuracy, and the specific characteristics of the ferroresonant circuit. The following sections provide a detailed comparison of these modeling techniques, and a list of them is in

Table 1.

3.1. Numerical Methods for Ferroresonance Modeling

Numerical methods use mathematical equations to describe how ferroresonant circuits work. They help explain the main mechanisms of ferroresonance, but they have limitations when modeling complex systems [

10,

12]. These methods can identify important parameters and show how they affect the system, but they usually work best for simple setups and are difficult to apply to real-world systems with complex nonlinear behavior.

3.1.1. Backward Differentiation Formula (BDF)/Numerical Differentiation Formula (NDF)

The Backward Differentiation Formula (BDF) and Numerical Differentiation Formula (NDF) are widely used for solving stiff differential equations arising in ferroresonance simulations. These methods are particularly effective at handling the stiffness inherent in transformer models. The NDF2 method, combined with the trapezoidal method, has been shown to suppress numerical oscillations and provide accurate results for voltage and current waveforms during both steady-state and transient ferroresonance. [

26]

Fractional-order models are often chosen over integer-order models because they describe capacitance and inductance more accurately. This results in a better understanding of how the system works [

27,

28].

The single-phase equivalent circuit illustrated in

Figure 2 is utilized for the analysis of series ferroresonance, comprising a series capacitance C and a nonlinear inductance L.[

22]

The numerical approach to solving expression (

5) when accounting for a nonlinear inductance is more intricate compared to finding a numerical solution for a straightforward RLC circuit. This is because the current depends on the magnetic flux (

), which means that the saturation curve of the nonlinear inductance needs to be represented as a function of the magnetic flux. The saturation curve is normally represented as a polynomial equation (

6) [

20,

22].

The final mathematical expression to represent ferroresonance in

Figure 4 is given in (

7) [

22].

The Equation (

7) is a nonlinear second-order differential equation, and finding an analytical solution is quite intricate. In general, capacitance exhibits considerable sensitivity to ferroresonance [

22].

A more detailed analytical framework is developed in [

19] in which single-phase ferroresonant oscillations are represented by a nonlinear second-order differential equation. The model is solved over a range of excitation frequencies, including both the fundamental network frequency and subharmonic components.

3.1.2. Explicit Euler Method

The Explicit Euler method is a straightforward numerical integration technique used to solve differential equations describing ferroresonant circuits. This method is simple to implement but may require small time steps to maintain stability, especially when modeling nonlinear inductive elements with hysteresis [

14]. Despite its simplicity, the explicit Euler method has been successfully applied to simulate ferroresonance modes in circuits with capacitive and inductive elements.

3.2. Numerical and Simulation-Based Models

The Electromagnetic Transients Program (EMTP) and PSCAD/EMTDC are powerful software tools for simulating ferroresonance in power systems. These tools are particularly useful for analyzing complex systems, such as three-phase transformers and distribution networks [

29,

30]. EMTP has been used to study the dynamics of ferroresonance in radial distribution systems and the impact of Distributed Generation (DG) on the phenomenon [

29].

Furthermore, time-domain simulation is a widely used method for analyzing ferroresonance. This approach involves solving the differential equations that describe the system’s behavior over time. Tools such as the Alternative Transients Program (ATP) are commonly used for this purpose [

13,

31]. It offers accurate modeling of nonlinear elements, including magnetic hysteresis and saturation. This makes it suitable for analyzing both transient and steady-state behavior. This comes at the expense of efficiency, as it is computationally intensive, especially for large-scale systems. This stems from the need for detailed models of system components, which can be challenging to obtain.

3.3. Nonlinear Electromagnetic (Magnetization) Models

Nonlinear dynamic analysis is a valuable tool for understanding the complex behavior of ferroresonant systems. It uses concepts such as phase portraits, Poincaré sections, and Lyapunov indices to analyze system dynamics [

32,

33]. This approach enables the identification of bifurcations and chaotic behavior, and facilitates examination of resonant conditions in the frequency domain. It is particularly useful for analyzing interactions between nonlinear inductance and capacitive elements [

11,

34].

It is difficult to apply to large-scale systems, and it requires advanced mathematical knowledge and computational tools, though. For instance, the Preisach theory is a physically correct hysteresis model that has been applied to ferroresonance modeling. This approach provides a precise representation of the hysteresis behavior of magnetic materials, making it suitable for studying the dynamic behavior of ferroresonant circuits [

35]. The Preisach model has been shown to outperform the EMTP hysteretic model in terms of accuracy when simulating experimental results.

Improved models, such as the modified inverse Jiles-Atherton model, account for major and minor hysteresis loops, enhancing simulation accuracy. These models are crucial for predicting transient and steady-state ferroresonance behavior [

14,

32,

36,

37]

Ritz’s method of harmonic balance is an example of the frequency-domain analysis used to formulate closed-form solutions for ferroresonance problems. This method is particularly effective for fundamental-frequency ferroresonance and involves representing the transformer core’s magnetization characteristic using a polynomial [

38]. The derived solutions enable the construction of stability maps that define the boundaries between safe and ferroresonant regions as functions of system parameters.

3.4. Tools for Ferroresonance Modeling and Analysis

Several tools support the analysis and simulation of power system dynamics, including ferroresonance. EMTP is widely used for simulating electromagnetic transients and is valued for its accurate modeling of nonlinear elements [

13,

31]. ATP offers a reliable alternative for transient simulations, especially in distribution systems [

13,

39]. Simulink provides a user-friendly interface, making it suitable for educational modeling and analysis of ferroresonance [

31,

40]. PSCAD/EMTDC is also commonly used for electromagnetic transient analysis and excels at modeling complex nonlinear systems [

15,

36]. The latest version of ETAP integrates with PSCAD to enable both RMS and transient simulations.

Analytical models support conceptual understanding, while EMT-type simulation is the practical choice for system-level studies. Hysteresis-based magnetization models improve accuracy but increase computation time. Numerical stability analyses offer insight into chaotic and bifurcation behavior. A hybrid approach that combines detailed magnetic modeling with fast numerical solvers is the most effective strategy.

The selection of a modeling technique should match the system’s needs and the required accuracy. Future research should aim to improve modeling accuracy and efficiency, and find better ways to reduce ferroresonance in power systems.

4. Ferroresonance Modes and Types

Ferroresonance can occur in several forms, each with distinct dynamic characteristics and system impacts. Understanding these modes supports effective detection and control. The most common is fundamental resonance, which arises when the resonant frequency of the nonlinear LC circuit matches the system’s main frequency [

16,

17,

32,

45]. This mode produces distorted but periodic waveforms that can persist if left unaddressed. It typically occurs during transformer energization or under light load conditions.

Subharmonic modes arise when the oscillation frequency becomes a fraction of the system’s fundamental frequency (e.g., 1/2, 1/3). These modes are often characterized by greater energy exchange between the inductive and capacitive components. Subharmonic behavior introduces severe waveform distortion and can evolve into chaotic resonance under certain conditions [

14,

16,

33,

36].

Chaotic ferroresonance exhibits non-periodic, unpredictable oscillations caused by nonlinear magnetic dynamics and hysteresis. This mode poses the greatest threat to system reliability, as protection systems often misinterpret chaotic waveforms, leading to false tripping or failure to operate. Chaotic resonance is difficult to predict and highly sensitive to switching conditions and remnant flux [

16,

17,

45].

In the case of RLC circuits, ferroresonance can be divided into two main types: series ferroresonance and parallel ferroresonance [

16]. An example of series ferroresonance occurs when a voltage transformer is energized via the grading capacitors of an open-circuit breaker, with the voltage transformer situated between the phase and ground. Parallel ferroresonance can occur during a single phase to ground fault in an isolated neutral system, where inductance and capacitance are configured in parallel [

16,

22]. In addition to series and parallel categories, ferroresonance can be classified as sustained ferroresonance and transient ferroresonance. Sustained ferroresonance behaves similarly to the second-order step response of an RLC circuit, where a source provides the resonating effect, which can originate from the system’s voltage. This type of ferroresonance will persist indefinitely until the voltage source is disconnected. In contrast, transient ferroresonance diminishes over time because the source that supplies the resonant effect is a limited-energy source, such as the capacitance of a cable isolated from the network [

16].

Transient ferroresonance occurs when the disturbance source is of limited duration or magnitude, resulting in oscillations that decay over time. Sustained ferroresonance persists indefinitely due to a continuous energy source, typically from system voltage or capacitor banks. Distinguishing between these behaviors is critical for designing mitigation strategies [

4].

Series ferroresonance commonly arises when a transformer is energized through a capacitive element, creating a nonlinear series LC circuit. On the other hand, parallel ferroresonance occurs when inductive and capacitive elements are connected in parallel, often during ground faults in isolated or resonant-grounded systems. Understanding these configurations helps engineers identify vulnerable topologies [

4].

5. Ferroresonance Mitigation Techniques

The study and mitigation of ferroresonance have evolved significantly over the years, where initial research focused on understanding the fundamental principles of ferroresonance and its effects on power systems. Experimental studies and theoretical analyses laid the foundation for developing mitigation techniques [

17]. Early mitigation methods relied on passive devices such as damping resistors and capacitors. These methods were effective but had limitations in terms of power losses and system complexity [

46]. The following development of active suppression circuits and advanced control strategies marked a significant advancement in ferroresonance mitigation. These methods offered faster response times and improved system stability [

24,

47]. Recent advancements include the use of solid-state circuits, Static Synchronous Compensator (STATCOM), and superconducting coils. These techniques provide highly effective and efficient solutions for ferroresonance mitigation in modern power systems [

47,

48,

49]. A list of the mitigation techniques, including recent advancements are in

Table 2.

A comprehensive analysis of ferroresonance mitigation techniques is provided, focusing on transformer protection, voltage regulation, theoretical models, general applications, historical developments, and recent advancements.

5.1. Transformer Protection

Transformer protection is a critical aspect of ferroresonance mitigation. Ferroresonance can cause severe overvoltages in transformers, potentially leading to insulation failure and catastrophic damage. Several techniques have been developed to protect transformers from ferroresonance for different transformer applications. Passive Ferroresonance Suppression Circuits (PFSC) and Active Ferroresonance Suppression Circuits (AFSC) are widely used to mitigate ferroresonance in Coupling Capacitor Voltage Transformers (CCVTs). AFSCs are more effective, mitigating ferroresonance in about two cycles, and their output fidelity is less dependent on burden compared to PFSCs [

24]. Installing damping resistors or capacitors in the circuit can mitigate ferroresonance in about 2 cycles, and their output fidelity is less dependent on burden than that of the transformer circuit, thereby effectively reducing ferroresonance effects. These components absorb or dissipate the excess energy in the circuit, preventing overvoltages [

50,

51]. Surge arresters are commonly used to protect transformers from overvoltages caused by ferroresonance or otherwise. They divert excess voltage to ground, ensuring the transformer operates within safe voltage limits [

46,

52]. Solid-state ferroresonance-suppressing circuits have been developed for voltage transformers in wind generation systems. These circuits use power IGBTs to suppress ferroresonance overvoltages and protect parallel-connected equipment [

47].

5.2. Voltage Regulation

Voltage regulation is another key area addressed in ferroresonance mitigation. Maintaining stable voltage levels is essential to prevent the onset of ferroresonance and its detrimental effects. One way is to optimize transformer design in which Finite Element Method (FEM) and MATLAB/Simulink modeling typically have been used to optimize transformer designs, focusing on core losses, flux density, and ferroresonance resilience. Optimized designs reduce Total Harmonic Distortion (THD) and core losses, enhancing overall performance [

53]. STATCOM for reactive power control are used to regulate reactive power in grid-connected Wind Energy Conversion Systems (WECS). By mitigating ferroresonance overvoltages, STATCOM improves system voltage profiles and protects equipment from damage [

52]. Moreover, a more sophisticated technique is dynamic voltage regulation, which utilizes advanced control strategies, such as Proportional-Integral (PI) controllers, to dynamically regulate voltage levels. These controllers are optimized using algorithms like the Modified Flower Pollination Algorithm (MFPA) to ensure fast and effective voltage regulation [

52].

6. Artificial Intelligence Techniques

AI has revolutionized fault detection and diagnosis in modern power systems. Ferroresonance, a complex nonlinear phenomenon characterized by overvoltages and chaotic oscillations in power transformers and networks, presents unique detection challenges that AI techniques are increasingly addressing. This review synthesizes recent literature to provide a comprehensive understanding of AI methodologies and their specific application to ferroresonance detection.

6.1. Machine Learning (ML)

ML encompasses algorithms that learn input-to-output mappings or discover structure from data rather than following fixed, pre-programmed rules. ML includes supervised learning (learning from labeled examples), unsupervised learning (finding patterns in unlabeled data), and reinforcement learning (learning through interaction and rewards) [

55,

56].

ML algorithms process features extracted from voltage and current waveforms, protection relay signals, and system measurements to classify fault types, predict equipment failures, and support protective decision-making [

55,

56].

6.2. Deep Learning (DL)

DL refers to multi-layer (deep) neural network architectures that automatically learn hierarchical feature representations from raw signals such as time series, images, or spectrograms. Unlike traditional ML that requires manual feature engineering, DL methods learn features automatically from data, though they typically require large labeled datasets for effective training [

55,

56].

DL excels at processing raw waveform data, automatically extracting relevant features without manual signal processing, making it particularly valuable for complex phenomena like ferroresonance where feature engineering is difficult [

57,

58].

6.3. Artificial Neural Networks (ANNs)

Artificial Neural Networks (ANNs) are computational models inspired by biological neural networks, consisting of interconnected layers of nodes (neurons) with weighted connections. Common architectures include Multi-Layer Perceptrons (MLPs), Convolutional Neural Networks (CNNs), and Recurrent Neural Networks (RNNs). ANNs are trained through optimization algorithms (typically backpropagation) to approximate complex nonlinear functions, making them suitable for both classification and regression tasks in power system protection [

56,

59].

ANNs are widely used for fault classification, protective relay decision-making, and pattern recognition in power system signals due to their universal approximation capability and ability to learn from historical data [

56,

59,

60].

6.4. Support Vector Machines (SVMs)

Support Vector Machines (SVMs) are margin-based supervised learning algorithms that find optimal hyperplanes to separate different classes in feature space. SVMs can handle nonlinear classification using kernel functions (e.g., Radial Basis Function (RBF) or polynomial) that implicitly map inputs to higher-dimensional spaces. SVMs are particularly effective with moderate-sized feature sets and are relatively robust to overfitting compared to some other methods. SVMs have been successfully applied to fault type classification, fault location, and protection zone identification, particularly when working with carefully engineered features from time-domain or frequency-domain signal analysis [

56,

71,

72].

6.5. Decision Trees and Ensemble Methods

Decision trees use if-then rules to split data into different regions. Each internal node checks a feature, branches show possible outcomes, and leaf nodes give class labels or regression values. Ensemble methods like Random Forests combine several decision trees to boost prediction accuracy and help prevent overfitting. These approaches make it easier to understand the rules and analyze which features matter most. In power systems, decision trees are useful because they are easy to understand, run quickly, and can handle both numerical and categorical data. They are especially important when explaining protection decisions [

56,

72].

6.6. Fuzzy Logic

Fuzzy logic is a reasoning framework that handles uncertainty and imprecision by allowing variables to have degrees of membership in sets rather than binary (true/false) membership. Fuzzy systems use linguistic rules (e.g., "IF voltage is high AND current is medium THEN fault is likely") that mimic human expert reasoning. Fuzzy inference systems combine multiple fuzzy rules to make decisions under uncertainty [

56,

73].

Fuzzy logic is particularly valuable in power system protection for handling uncertain measurements, noisy signals, or situations where exact thresholds are difficult to define. It enables robust decision-making under imprecision [

56,

59,

73].

6.7. Genetic Algorithms (GAs) and Evolutionary Methods

Genetic Algorithms (GAs) are population-based optimization techniques inspired by biological evolution. They maintain a population of candidate solutions and iteratively improve them via selection, crossover (recombination), and mutation. GAs are used for parameter tuning, feature selection, hyperparameter optimization, and solving complex optimization problems where gradient-based methods are unsuitable. In power system applications, GAs are commonly used to optimize neural network architectures, select optimal feature subsets, tune protection relay settings, and optimize power system controller parameters [

55,

74].

6.8. Expert Systems

Expert systems are knowledge-based systems that encode domain expertise as if-then rules and use inference engines for diagnostic or decision-making tasks. Traditional expert systems depend on knowledge engineering, which involves extracting and formalizing expert knowledge. Although once essential for power system protection, expert systems are now less common in recent literature due to challenges in knowledge acquisition and maintenance.

Expert systems were among the first AI applications in power systems, used for fault diagnosis, alarm processing, and protection coordination. Modern approaches often combine expert rules with machine learning for improved adaptability [

56,

75].

6.9. Comparative Analysis

Each of the above-discussed AI techniques offers distinct strengths in modeling complexity, interpretability, and computational demand. A synthesis of comparative findings across performance, robustness, and implementation dimensions highlights the varying suitability of these techniques for different protection contexts.

Table 3 lists strengths and weaknesses of these AI techniques for ferroresonance detection application.

Also,

Table 4 presents a quantitative comparison of the listed AI approaches across key performance dimensions.

ANNs, including multilayer perceptrons and their DL extensions, have been widely studied for modeling complex transient behaviors. Their capacity for universal function approximation and rapid inference makes them strong candidates for high-speed protection schemes [

61,

62]. DL architectures such as CNNs and Long Short-Term Memory (LSTM) networks further enhance these capabilities by automating feature extraction and capturing temporal patterns. Their demonstrated high accuracy in classifying disturbance signatures has positioned them at the forefront of ferroresonance detection research [

64,

65]. However, these methods suffer from well-documented limitations, including extensive data requirements, high training costs, and limited interpretability, which constrain their deployment in environments where transparency and auditability are essential [

64,

65,

68].

Rule-based systems like fuzzy logic frameworks and expert systems are valued for being clear and reliable when working with uncertain or incomplete data. Fuzzy logic systems use clear language rules and membership structures, so domain experts can check results and trust the system’s decisions [

66]. Expert systems offer transparent reasoning but cannot learn from new data, which makes it hard for them to adapt to changes in the grid [

66]. Hybrid neuro-fuzzy systems bring together the accuracy of fuzzy logic and the flexibility of neural networks. This approach can improve accuracy and keep some interpretability, but as the system gets more complex, it can become harder to understand because there are more rules [

68].

Margin-based and tree-based methods balance interpretability and predictive performance. SVMs generalize well with limited data and excel in high-dimensional spaces, but their performance depends on kernel selection and training time increases with larger datasets [

67]. Decision trees provide transparent, hierarchical rules and fast inference, making them suitable for real-time protection. Random forests address overfitting by using ensemble averaging to enhance robustness and accuracy. These ensembles, including boosting-based techniques, deliver high detection performance, especially with imbalanced or noisy data, though they reduce interpretability and require greater computational resources [

66,

67].

Comparative analyses across performance metrics further underscore these distinctions. DL and ensemble methods generally yield the highest classification accuracies [

64,

65], while logic-based systems provide the greatest interpretability. Inference time is critical for sub-cycle protection, favoring ANNs, fuzzy logic systems, expert systems, and decision trees, all of which achieve millisecond-scale response times. Data requirements vary dramatically across methods, with DL models requiring orders of magnitude more training data than SVMs, decision trees, or transfer learning–based approaches. Complexity profiles follow similar patterns, with deep models exhibiting the highest architectural and computational demands [

61,

62,

66,

67,

66,

67].

Interpretability remains a central concern in the application of AI to protection systems, where operators and regulators require transparent justification for automated decisions. Fuzzy logic, expert systems, and decision trees offer the clearest reasoning mechanisms [

66,

67,

66,

67], while neural networks and DL architectures rely on post-hoc explainability tools such as saliency maps and relevance propagation [

61,

62,

64,

65]. Although these techniques improve comprehension, they do not fully resolve the models’ intrinsic opacity. This limitation has implications for regulatory compliance and operator trust, particularly in high-stakes applications such as ferroresonance mitigation.

Studies of various power system tasks show that no single AI method performs best across all applications. Techniques with strong nonlinear modeling, like DL, neuro-fuzzy systems, and ensembles, are most useful for detecting ferroresonance, where it is important to identify complex modal interactions. Faster, more interpretable methods, such as artificial neural networks, fuzzy systems, and decision trees, are better suited for real-time protection.

Table 5 gives an overview of AI tools used in power system protection, including for ferroresonance detection.

Implementation considerations highlight several trade-offs. DL and ensemble models have high development and deployment costs due to computational demands [

64,

67,

68,

76]. In contrast, decision trees, SVMs, and ANNs are more cost-effective [

61,

66,

67]. Expert systems are easy to deploy but require significant ongoing maintenance as system conditions evolve [

66]. DL, random forests, and ensembles perform well with large-scale or diverse data, while fuzzy logic and decision trees are effective in noisy or incomplete data environments. Transfer learning is useful when training data is limited, though it poses risks if there is a domain mismatch [

66,

68].

Among the above comparisons, the strongest candidate for real-time ferroresonance detection, in terms of accuracy, inference time, hardware feasibility, and stability, is an MLP combined with fast signal preprocessing, such as a discrete wavelet transform. The ANN technique provides sub-millisecond inference (ideal for real-time relays), effectively models ferroresonance signatures, and has moderate data requirements (1k–10k samples), thereby making it trainable even with limited ferroresonance data. On the other hand, wavelet preprocessing significantly improves reliability, reduces noise sensitivity, and extracts modal energy components that are crucial for identifying ferroresonance initiation. This combination has already been shown in practice for detecting voltage transformer ferroresonance and transformer differential anomalies.

7. Overview of Artificial Neural Networks

ANNs have become indispensable tools in modern power system protection, offering powerful pattern recognition and nonlinear function approximation capabilities. Neural networks were inspired by biological neural systems and have evolved through multiple generations from simple perceptrons in the 1950s to modern DL architectures. In power systems, ANNs have been applied since the 1990s for fault detection, classification, and protection [

77,

78]. The evolution from shallow to deep architectures, combined with advances in optimization algorithms and computational power, has dramatically expanded ANN capabilities for complex power system applications [

63,

69].

7.1. Neural Network Architectures

7.1.1. Multi-Layer Perceptron (MLP) and Feedforward Networks

MLPs are feedforward neural networks made up of an input layer, one or more hidden layers, and an output layer. Each layer is fully connected to the next. In these networks, each neuron sums its inputs with weights, applies a nonlinear activation function, and then passes the result to the next layer [

62,

63,

79].

For a neuron

j in layer

l, the activation is computed as:

where

is the activation,

are the weights,

is the bias term, and

is the activation function.

7.1.2. Convolutional Neural Networks (CNN)

CNNs employ local receptive fields, weight sharing, and hierarchical feature extraction through convolutional layers. In power systems, 1D-CNNs are commonly applied to waveform and transient signal analysis [

64,

69].

The 1D convolution operation is defined as:

where

is the output,

are learnable filter weights,

are input signal values, and

b is the bias term.

7.1.3. Recurrent Neural Networks (RNN, LSTM, GRU)

RNNs contain recurrent connections that create internal state (memory), enabling modeling of sequential and time-series data. Gated variants-LSTM and Gated Recurrent Unit (GRU)-address the vanishing gradient problem and enable learning of long-term dependencies [

65,

69,

79].

The basic RNN structure is described by:

where

is the hidden state,

is the input, and

is the output at time

t.

LSTM Architecture: LSTMs introduce gating mechanisms with forget gates, input gates, and output gates to control information flow:

Where is the sigmoid activation, ⊙ is element-wise multiplication, and is the cell state.

Table 6 provides a comprehensive comparison of strengths and weaknesses for major ANN architectures, highlighting their suitability for different power system protection applications.

Early studies showed that shallow neural networks, such as MLPs, can detect nonlinear behavior in voltage transformers when using features selected by experts [

61]. This supports the strengths listed for MLPs in

Table 6, which highlights their low computational needs and real-time suitability. RBF networks also train quickly and are easier to interpret, but they struggle to model highly irregular resonant waveforms. Recurrent networks, such as Elman networks and LSTMs, are better at following changes in ferroresonant oscillations over time, as recent power system monitoring studies have shown [

76,

77]. These findings are consistent with

Table 6, which rates RNN-based models highly for analyzing sequential waveforms.

7.2. Training Methods and Optimization

How well ANNs perform depends heavily on the training algorithm, optimization strategy, and regularization techniques used.

Backpropagation is the main algorithm for computing gradients of the loss function with respect to network parameters. It uses the chain rule to efficiently send error signals backward through the network layers [

63,

78].

For a weight

:

where

is the loss function,

is the error term, and

is the activation.

Modern training uses several variants of gradient descent.

Table 7 compares the most commonly used optimization algorithms, including their key features, advantages, and disadvantages.

The optimizer comparison in

Table 7 reflects widely reported algorithmic behavior in machine learning literature. Adaptive gradient methods such as Adam and AdamW consistently achieve faster convergence and better stability compared to classical Stochastic Gradient Descent, particularly for deep architectures with high non-convexity [

69,

81]. These findings reinforce the validity of optimizer selection for the models evaluated in the ferroresonance context.

7.2.1. Activation Functions

Activation functions introduce nonlinearity to the model and enable neural networks to approximate complex problems.

Table 8 provides a detailed comparison of standard activation functions, their properties, and recommended use cases.

Common activation functions include:

Sigmoid: with range

, historically popular but suffers from vanishing gradients [

80,

81].

Hyperbolic Tangent: with range , zero-centered but still saturates.

ReLU: , default choice for hidden layers due to no vanishing gradient, computational efficiency, and faster training [

69,

81].

Softmax: , used for multi-class classification output layers [

81].

The activation function comparisons in

Table 8 reflect established theory. ReLU and its variants are preferred for deep networks because they converge quickly and avoid gradient saturation [

69,

81]. Sigmoid and tanh are still suitable for output layers or shallow networks. These choices align with the activation strategies used in many power-system fault-detection studies.

7.2.2. Regularization Techniques

To avoid overfitting—especially when disturbance data are scarce—ANN training typically incorporates:

L2 Regularization (Weight Decay): Adds penalty term

to loss function, encouraging small weights [

69,

81].

Dropout: Randomly sets fraction

p of neuron activations to zero during training, preventing co-adaptation [

69,

81].

Batch Normalization: Normalizes inputs to each layer to have zero mean and unit variance within mini-batches, enabling faster training and improved gradient flow [

69].

Early Stopping: Monitors validation loss and stops training when it stops improving, automatically preventing overfitting [

81].

7.3. Comparative Analysis

ANN architectures vary in accuracy, training speed, and inference speed, making some more suitable for specific applications. Shallow models such as MLPs and RBFs train and run quickly with moderate data, making them ideal when speed and efficiency are priorities. Convolutional networks and RNNs offer higher pattern recognition accuracy with spatial or temporal data but require more data, longer training times, and often Graphics Processing Unit (GPU) support. Hybrid CNN–RNN models achieve the highest accuracy by combining both learning types, but they demand even more data, train slowly, and are less interpretable. Ensemble methods enhance accuracy and robustness by combining multiple models, though this increases complexity and slows inference. Ultimately, selecting a model for ferroresonance detection requires balancing accuracy, efficiency, and transparency.

Table 9 provides a comprehensive performance comparison of major ANN architectures across key metrics, including accuracy, training speed, inference speed, data requirements, and interpretability. This comparison guides architecture selection based on specific application requirements.

7.3.1. Application Suitability

Various ANN architectures are best suited for different power system tasks, such as real-time protection, waveform analysis, sequential processing, and ferroresonance detection. Shallow architectures such as MLPs and RBFs work well for fast, real-time protection and waveform analysis because they offer low latency and stable results. RNNs, including LSTM and GRU networks, perform better on sequential and time-based tasks because they can track changes over time, but they require more computing power. Hybrid CNN-RNN models combine spatial and temporal features, making them especially useful for detecting ferroresonance, which involves complex dynamics. Ensemble methods are reliable across many applications, showing strong robustness and the ability to generalize.

Task-specific suitability analysis in

Table 10 reinforces these conclusions: models with strong temporal representation capabilities are best aligned with ferroresonance detection, while shallow ANNs remain appropriate for simpler real-time monitoring tasks. These observations are consistent with recent system-level assessments of ferroresonance mitigation strategies, which increasingly favor hybrid architectures that fuse modal decomposition with adaptive neural inference.

7.3.2. Computational Requirements

When deploying algorithms, it is important to consider computational limits, as these affect which methods can be used. Lightweight models such as MLPs and RBF networks require little computational power and memory. This makes them suitable for real-time use on standard Central Processing Unit (CPU) and easy to add to embedded protection devices. On the other hand, DL models such as CNNs and RNNs need much more computing and memory, especially during training, which usually requires GPU acceleration. Although inference can be improved with edge accelerators such as Tensor Processing Units (TPUs), using these models in embedded systems is often limited by hardware costs and power consumption. Hybrid CNN-RNN and ensemble methods also impose additional computational demands, so they are mostly used for offline analysis or in central monitoring systems.

Table 11 compares architectures in terms of hardware requirements, memory usage, real-time feasibility, and embedded deployment potential-critical factors for relay implementation. Overall, the Table highlights the trade-off between model complexity and deployment feasibility, indicating that simpler architectures remain the most practical option for real-time ferroresonance detection in protection-oriented power system applications.

Table 9 and

Table 11 show the balance between accuracy, computational cost, and real-time use. Deep models like CNNs and LSTMs are more accurate, but their hardware needs make them less practical for standard protection relays. In contrast, MLPs, RBF networks, and lightweight Elman models can deliver results in milliseconds with only basic CPU resources, making them better suited for protective relay applications.

7.3.3. Training Characteristics

ANNs vary in data requirements affecting their training characteristics. Shallow models, such as MLPs and RBF networks, require relatively small training datasets and exhibit fast training times with stable convergence behavior, making them suitable for rapid development and real-time applications. Architectures that incorporate temporal or spatial feature learning, including convolutional and RNNs, require substantially larger datasets and longer training durations, reflecting increased model complexity and greater sensitivity to hyperparameter selection. Hybrid CNN–RNN structures and ensemble methods exhibit the highest data and training-time requirements, with convergence behavior that is more difficult to control, particularly in limited-data scenarios. These trends highlight a clear trade-off between modeling capacity and training efficiency, emphasizing that data availability and convergence stability are critical considerations when selecting AI-based ferroresonance detection methods for practical power system applications.

Table 12 summarizes training characteristics, including data requirements, feature engineering needs, training time, and convergence stability. This information is essential for planning ANN development projects and estimating resource needs.

7.3.4. Performance Trade-offs

Accuracy vs. Speed: Deep architectures (CNNs, hybrid CNN-RNN) achieve highest accuracy but slower inference; shallow MLPs offer fast real-time response suitable for sub-cycle protection [

62,

64,

82].

Accuracy vs. Interpretability: Complex models (CNNs, ensembles) are more accurate but less interpretable; RBF networks and shallow MLPs provide greater transparency [

66,

78,

79].

Data Requirements: RBF networks and shallow MLPs are effective with hundreds to thousands of samples; DL requires tens of thousands [

62,

69].

7.3.5. ANN Approaches for Ferroresonance Detection

ANN-based architectures vary in their effectiveness for detecting ferroresonance. The field has shifted from manually designed feature-based classifiers to hybrid and DL frameworks that automatically extract features and model temporal patterns. Early models, whether using direct system identification or manual feature extraction, trained quickly and were easy to interpret, but they struggled with complex ferroresonant behavior. Hybrid methods that combine signal processing techniques, such as wavelet or variational mode decomposition, with neural networks offer higher detection accuracy and greater robustness to noise and transformer saturation. DL and transfer learning models further improve performance through hierarchical feature learning and pretrained representations, though they require more computing power and offer less transparency.

Table 13 looks at ferroresonance detection and shows that hybrid Variational Mode Decomposition (VMD)-CNN, VMD-LSTM, and wavelet–LSTM systems have the highest detection accuracy found in the literature. It also shows that traditional MLP-based methods, though a bit less accurate, remain appealing because they use less computing power, making them well-suited for real-time use. In summary, the table shows a balance among how easy models are to understand, how much computing they require, and how accurate they are. This highlights why hybrid and DL models are becoming more popular for high-accuracy detection, but also shows the benefits of simpler models for real-time protection.

The comprehensive comparisons presented in

Table 6,

Table 7,

Table 8,

Table 9,

Table 10,

Table 11,

Table 12 and

Table 13 reveal that no single architecture is universally superior; selection depends on specific application requirements, including accuracy needs, real-time constraints, data availability, interpretability requirements, and computational resources.

8. Ferroresonance in Renewable Energy Resources Integration

In renewable energy grids, particularly those integrated with wind, solar, and energy storage systems, ferroresonance poses significant challenges by potentially damaging equipment and disrupting power quality.

Ferroresonance can have devastating effects on RE-based grid components, including:

Transformers: Overvoltages and harmonic distortion can lead to core saturation, excessive heating, and eventual failure [

50].

Voltage Transformers (VTs): Ferroresonance can cause overvoltages and distorted waveforms, damaging VTs and parallel-connected equipment [

47].

Cables and Capacitors: The resonant currents can stress insulation and reduce the lifespan of capacitors and cables.

Wind Turbines and Energy Storage Systems (ESS): Overvoltages can damage power electronics and battery systems, particularly in systems with unbalanced load currents or rising DC ground potentials.

8.1. Ferroresonance Trigger and Conditions

Ferroresonance is primarily initiated by the interaction between the nonlinear magnetizing inductance of transformers and the capacitive reactance of the network as mentioned earlier. This interaction can lead to a resonant circuit that sustains overvoltages and currents. In renewable energy systems, the phenomenon is often triggered by one or more of the following:

Transformer Core Saturation: The nonlinear characteristics of the transformer core create a feedback loop between the voltage and current, leading to resonance [

84].

Capacitive Compensation: The presence of shunt capacitors or cable capacitance in the network provides a path for resonant currents [

43].

Faults and Switching Events: Single-line-to-ground faults, line-to-ground faults, or the clearing of high-impedance faults can initiate ferroresonance by creating unbalanced network conditions [

85,

86].

The resonance frequency is determined by the circuit’s inductance and capacitance, and the severity of the overvoltages depends on the system’s damping characteristics.

Ferroresonance is more likely to occur under specific operational conditions in renewable energy grids. A sudden disconnection of the load on the secondary side of a transformer can cause a voltage rise on the primary side, initiating ferroresonance [

50]. Network configurations is an important factor for ferroresonance initiation. For instance, radial distribution systems with long feeders and shunt capacitors are more susceptible to ferroresonance than many other network configurations, due to their lower damping factors [

3]. The integration of renewable energy sources, such as wind turbines or PVs systems, can introduce additional resonant paths and harmonic distortion, increasing the likelihood of ferroresonance. Furthermore, unbalanced currents in the grid-connected transformer can saturate the core, creating conditions for ferroresonance.

8.2. Mitigation Techniques

To address the challenges posed by ferroresonance, various mitigation techniques have been developed and implemented, similar to those described in

Section 5, including passive and active approaches. The RE-based grids employ advanced control strategies that use PI controllers and specialized filters to control specific parameters. The PI controllers are optimized using algorithms such as the elephant herding optimization, which can regulate the duty cycle of DC-choppers in superconducting coil systems [

52]. Moreover, edge detection and morphological filters are used to identify and mitigate high-frequency components in the zero-sequence current, thereby preventing ferroresonance.

Table 14 lists different mitigation tactics for RE grids.

9. Application to Ferroresonance Phenomena

Ferroresonance became a serious issue in power systems in the mid-20th century, especially in high-voltage networks. Early studies focused on its main causes, like the effects of nonlinear inductances and capacitive couplings. Using voltage transformers and CVTs made the problem worse, as their nonlinear behavior increases the risk of ferroresonance [

17,

44].

In the 1980s and 1990s, researchers began developing theoretical models and experimental setups to analyze ferroresonance. These efforts led to the identification of various modes of ferroresonance, including fundamental, subharmonic, and chaotic resonances. The development of simulation tools like PSCAD/EMTDC and EMTP/ATP further enhanced the ability to model and predict ferroresonance in power systems [

89].

Recent advancements in distributed generation and renewable energy integration have introduced new challenges, as these systems often operate under different dynamic conditions, increasing the likelihood of ferroresonance [

1,

17].

Ferroresonance in Medium Voltage (MV) networks has been studied using digital simulation models developed in MATLAB/Simulink. These models analyze the conditions that initiate ferroresonance oscillations and evaluate signals for detection, such as phase and open delta VT voltages. The models also explore the suppression of ferroresonance oscillations, providing valuable insights for predictive modeling and control [

90].

Researchers have studied ferroresonance in voltage transformers using nonlinear dynamics methods. They modeled the magnetizing characteristics of these transformers using polynomial expressions and found that the system can exhibit fundamental-frequency, subharmonic, and chaotic ferroresonance. These findings show how complex ferroresonance is and why advanced modeling techniques are needed [

91].

Ferroresonance can significantly impact real-world systems. For instance, adding subsea cables increases capacitive reactance, raising the risk of ferroresonance during system switching [

43]. In power quality studies, ferroresonance has also been observed in low-voltage systems with power-factor-correction capacitors, particularly under high harmonic distortion [

18].

Significantly, case studies have documented transformer failures due to ferroresonance, underscoring the need for robust design and protection measures [

4,

84].

Wind generation systems can cause ferroresonance when added to power grids because wind turbine inverters have unique features [

92,

92].

9.1. Experimental Cases

The authors in [

18] investigate the occurrence and impact of three-phase ferroresonance in a low-voltage Power Factor Correction (PFC) system, focusing specifically on the influence of harmonic distortion on its triggering. The study is based on real field measurements conducted in an industrial plant where the detuned reactor within the PFC system experiences ferroresonance when the capacitor stage is switched on under conditions of elevated harmonic distortion [

93,

94]. The authors present a case study demonstrating how integrating variable-speed drives, which induce significant current harmonic injection, can radically alter the behavior of a detuned reactor, leading to excessive overvoltages, overcurrents, audible noise, and overdamping of system components.

The paper provides a detailed theoretical background on ferroresonance, discussing its nonlinear nature, the conditions required for its initiation, and its characteristic oscillation modes, including fundamental, subharmonic, quasi-periodic, and chaotic oscillations [

95]. It emphasizes that ferroresonance occurs when energy oscillates between a capacitive element and a nonlinear inductive element that saturates, thereby causing severe distortions in the voltage and current waveforms. This analysis is enriched by a comprehensive discussion on the resonance conditions determined by the detuning factor of the reactor and the proximity of the system’s resonant frequencies (e.g., the critical 210 Hz frequency) to dominant harmonic components like the 5th harmonic [

96,

97].

The study uses synchronized data acquisition systems to record high-resolution voltage and current waveforms on both the low and medium voltage sides of the transformer station. The setup features advanced sensors like Rogowski coils and high-speed high voltage inputs, which allow for accurate measurement of both transient and steady-state conditions before and during ferroresonance events [

98]. Researchers examined two operating conditions: a normal state (C1) with acceptable harmonic distortion, and a high distortion state (C2) where ferroresonance occurs. In the high-distortion case, results show that the detuned reactor and capacitors experience extreme overloads, with stage currents reaching up to 15 times the nominal value and severe harmonic propagation throughout the system [

99,

100].

The paper concludes by underscoring the critical importance of controlling harmonic distortion levels in industrial installations and the necessity of comprehensive simulation studies when system configuration or load types are altered. It advocates either implementing active filtering techniques or carefully dimensioning passive devices to mitigate the risks associated with ferroresonance [

97,

101]. Overall, the study provides significant insights into the potential hazards of ferroresonance in low-voltage systems and outlines practical recommendations for preventing such destructive events in power systems with high harmonic content.

Another paper [

102] investigates ferroresonance, focusing on how different initial conditions and phase shifts in a ferroresonant circuit affect its initiation. The authors use both experimental and numerical methods to clarify when ferroresonance can occur, thereby helping explain this complex nonlinear electrical phenomenon [

102,

103].

Ferroresonance is a nonlinear oscillation that happens when an iron-core inductor is powered by an AC voltage source through a capacitor. The paper explains the conditions that cause ferroresonance, focusing on the inductance of an unloaded transformer and the capacitance from components such as grading capacitors in circuit breakers [

104]. The authors describe ferroresonance as a bifurcation phenomenon in which a small change in system parameters can cause a major shift in the state variables, leading the system from normal to ferroresonant behavior.

The experimental setup consisted of a linear capacitor and a nonlinear coil based on a toroidal iron-cored transformer, with a variable-voltage source used to adjust the RMS voltage. The investigation systematically varied the source voltage from 1 V to 64 V, enabling observation of steady-state responses under different conditions. Notably, the study found that ferroresonance initiation depends on the RMS source voltage and the voltage phase shift, with specific ranges identified in which ferroresonance can be initiated [

105].

The results indicate a clear correlation between initial conditions, specifically the initial capacitor voltage and phase shift, and the initiation of ferroresonance. The authors employed an electronically controlled switch to precisely control the phase shift during experiments, enabling a detailed analysis of how these parameters influence the system’s behavior. The findings were further validated through numerical simulations, which demonstrated that the model could effectively replicate the experimental results, albeit with some discrepancies attributed to differences in model parameters [

105,

106].

In conclusion, the paper underscores the significant impact of initial conditions on ferroresonance initiation, providing valuable insights into the operational parameters that govern it. The implications of this research extend to the design and operation of electrical systems where ferroresonance may pose risks, thereby informing mitigation and control strategies. The authors also acknowledge the potential for further analytical studies, suggesting that while their focus was on experimental and numerical approaches, analytical methods could complement their findings in future research [

106].

10. Conclusions

Ferroresonance remains a significant challenge in modern power systems, especially as networks incorporate more automation, renewables, and power electronics. This review synthesized recent advancements over the past 5 years across ferroresonance modeling, detection, and mitigation, with particular emphasis on emerging AI techniques. Traditional modeling tools—ranging from analytical nonlinear magnetization models to electromagnetic transient simulation platforms such as EMTP, PSCAD, and ATP—continue to provide foundational insight into ferroresonant behavior. However, the nonlinear, multimodal, and often chaotic nature of ferroresonance limits the predictive capability of purely physics-based approaches in increasingly complex grid environments.

AI methods can work well alongside traditional modeling by improving pattern recognition, learning from data, classifying information, and making decisions. Machine learning, DL, neuro-fuzzy systems, SVMs, ensemble models, and evolutionary algorithms each have their own strengths, as shown in this study. DL and hybrid models achieve top accuracy, while simpler models like MLPs and RBF networks remain useful for real-time tasks because they require less computing power. Fuzzy logic and expert systems are valued for their ease of interpretation and for handling uncertainty, while GAs are strong in optimization and feature selection. Together, these tools form a growing set of AI techniques that can help with both detection and mitigation.

Even though a lot of progress has been made, using these approaches in real systems remains difficult. Data are often limited, many models are difficult to understand, protection relays have strict hardware constraints, and it is not easy to trust AI decisions in applications where safety matters. At the same time, better measurements, synchro-waveform analysis, and newer AI models are starting to change what is possible. Together, they point toward protection schemes that can recognize and respond to ferroresonance as it happens. The main takeaway from this review is that power system resilience will only improve if data-driven tools are grounded in solid physics, especially as grids become more distributed, renewable-heavy, and complex.

11. Future Work

Future research must bridge existing gaps in modeling fidelity, data availability, computational feasibility, and practical deployment to fully leverage AI-enhanced ferroresonance detection and mitigation. Several key directions emerge from this review:

Development of high-quality ferroresonance datasets. A major barrier to AI adoption is the lack of labeled waveform datasets capturing diverse ferroresonant scenarios. Collaborative data-sharing initiatives, Real-Time Digital Simulation (RTDS) platforms, and controlled laboratory experiments are needed to create standardized datasets suitable for training and benchmarking AI models.

Integration of physics-informed AI models. Physics-Informed Neural Networks (PINNs), hybrid data–model frameworks, and gray-box learning approaches can combine the strengths of electromagnetic theory with the adaptability of AI, enabling more interpretable and generalizable detection systems.

Real-time deployment on embedded protection hardware. Future studies should focus on designing lightweight, compressible AI models suitable for integration into digital relays, IEDs, and edge-computing devices, ensuring millisecond-level inference while minimizing memory and energy usage.

Enhanced interpretability and explainability. Explainable AI (XAI) methods—such as saliency maps, rule extraction, and surrogate modeling—must be adapted for power system contexts to enable protection engineers to validate and trust AI-generated decisions.

AI-driven adaptive mitigation strategies. Beyond detection, AI can enable dynamic mitigation schemes that adjust system parameters, initiate corrective switching actions, or tune reactive power support devices in real time to prevent ferroresonance escalation.

Co-simulation of power electronic converters and ferroresonant circuits. As renewable energy interfaces increasingly dominate grid dynamics, future research should incorporate detailed converter models and control loops into ferroresonance studies to capture emerging resonance pathways.

Standardization and regulatory considerations. The introduction of AI-based protection requires new testing protocols, reliability benchmarks, cybersecurity guidelines, and compliance frameworks to ensure safe adoption within transmission and distribution networks.