1. Introduction

The electrocardiogram (ECG) is one of the most widely used physiological signals for monitoring cardiac electrical activity, with applications ranging from arrhythmia detection to assessment of overall cardiac health. Traditionally, ECG monitoring has been performed in clinical settings using multi-lead systems, or through ambulatory Holter monitors for extended recordings [

1]. Recent advancements in wearable and portable ECG devices have enabled continuous, remote acquisition of ECG signals outside of clinical environments [

2,

3,

4], facilitating real-world long-term monitoring of individuals during their daily lives. ([

5])

Wearable and mobile ECG technologies, such as chest straps and handheld single- or multi-lead recorders, have been increasingly integrated with machine learning (ML) methods to augment signal analysis and automate detection of cardiac abnormalities. These systems have utilized traditional ML and deep learning approaches to classify arrhythmias and other ECG patterns, demonstrating improved performance over classical methods. [

6,

7,

8,

9,

10,

11] However, most existing research has focused on supervised models trained for specific diagnostic tasks or on relatively large curated datasets, often neglecting the personalization and stability of learned representations over time.

At the same time, studies in representational learning for ECGs using autoencoders and variational methods indicate that latent spaces can capture salient morphological and pathological features, and personalization (fine-tuning for individual subjects) can mitigate inter-subject variability [

12]. However, the longitudinal dynamics of such embeddings are largely unexamined, particularly for consumer-grade portable ECG recordings.

In this work, we investigate the temporal stability and individual specificity of ECG foundation model embeddings derived from daily, real-world recordings from two subjects. We leverage both the latent representations and task-level output probabilities of a pretrained ECG foundation model to assess 1) geometric clustering of individual’s ECGs, 2) intra-subject drift over 3-4 weeks period, and 3) subject-specific separability in the learned embedding space. Our findings demonstrate that even with limited data, foundation model representations from portable ECG devices exhibit robust stability and individuality, enabling consistent longitudinal characterization at the person level.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design and Participants

This study was designed as a longitudinal, observational case study to evaluate the temporal stability and individual specificity of ECG representations derived from a pretrained foundation model. Two healthy adult participants (one male, one female), living in the same household, were included. Both participants provided written informed consent prior to data collection. The study involved only non-invasive recordings using commercially available consumer devices and did not include any clinical interventions or induced stressors. All data were anonymized prior to analysis.

2.2. ECG Data Acquisition

Daily resting ECG recordings were collected over a 20 to 30-day period using a portable, consumer-grade six-lead ECG device (Kardia Mobile 6-lead, AliveCor, USA). Each recording lasted 30 seconds and was acquired in a seated, resting posture under similar environmental conditions.

2.3. Signal Preprocessing and Quality Control

ECG signals were exported in digital format and subjected to minimal preprocessing prior to model inference. This included basic signal quality checks to exclude recordings with excessive noise or poor electrode contact. No aggressive filtering or manual annotation was applied, in order to preserve real-world signal variability and to evaluate the robustness of the pretrained foundation model to consumer-grade recordings. The only filtering was to remove first 5 seconds of each signal since the first few seconds were always noisy. This is a general issue for mobile ECG devices.

2.4. ECG Foundation Model Representations

Each ECG recording was processed using a pretrained ECG foundation (ECGfounder[

13]) model. The model produces two complementary forms of output: 1) Latent embedding vectors, representing high-dimensional internal representations learned during large-scale pretraining, 2)

Task-level probability outputs, corresponding to predicted probabilities for a set of ECG-related tasks or features (e.g., rhythm, disease or morphology-associated outputs).

The model works on 10 second strips with 500Hz sampling. We chunked the 25 second ECG signals to overlapping windows of four 10 second strips. We calculated the embeddings for each strip and averaged the embedding vectors to represent each 25 second strip. For each recording, both the latent embedding vector and the vector of task probability outputs were extracted this way. These representations were treated as fixed feature vectors and were not fine-tuned or adapted during the study.

2.5. Dimensionality Reduction and Visualization

To examine the global structure of the learned representations, principal component analysis (PCA) was applied separately to the latent embedding vectors, and the task-probability output vectors. The first two principal components were retained for visualization. PCA was performed on the union of all recordings from both participants, and resulting projections were visualized with points colored by subject identity.

2.6. Temporal Drift Analysis

Temporal stability of ECG representations was assessed by quantifying intra-subject drift over time. For each subject and representation type, a subject-specific mean representation was computed by averaging the feature vectors across all days. Intra-subject drift was then defined as the cosine distance between each day’s representation and the corresponding subject-specific mean representation.

To provide a reference scale for interpretation, inter-subject distances were computed as the cosine distance between representations from different subjects for matching days. The mean and standard deviation of these inter-subject distances were used as a reference band in visualization. Drift trajectories were plotted as a function of recording date for each subject.

2.7. Distance-Margin Separability Analysis

Subject-specific separability was evaluated using a nearest-centroid distance-margin analysis. For each representation, cosine distances to both subject centroids were computed. A distance margin was defined as:

where

is the distance to the subject’s own centroid and

is the distance to the other subject’s centroid. Positive margins indicate that a representation is closer to the correct subject centroid.

Margin distributions were summarized separately for each subject and visualized using box plots. This analysis does not involve classifier training and is intended to characterize geometric separability in representation space.

2.8. Statistical Analysis

Statistical significance of the observed separation was assessed using a non-parametric permutation test. Subject labels were randomly permuted across embeddings, and the mean distance margin was recomputed for each permutation. This procedure was repeated 10,000 times to generate a null distribution of mean margins. An empirical p-value was computed as the proportion of permutations yielding a mean margin greater than or equal to the observed value.

3. Results

3.1. Embedding Geometry and Subject-Specific Separation

We first examined the global structure of the learned ECG representations using principal component analysis (PCA).

Figure 1 shows the first two principal components of the ECG foundation model embeddings for all recordings across the study period. Despite day-to-day variability, embeddings from the two subjects form clearly separated clusters in low-dimensional space, with minimal overlap. This separation was observed without any supervised training or fine-tuning, indicating that subject-specific information is intrinsically encoded in the learned representation.

To assess whether this separation was also reflected in the model’s task-level outputs, we performed PCA on the vector of predicted probabilities associated with ECG-related tasks (e.g., rhythm and feature-specific outputs) produced by the same foundation model. As shown in

Figure 1, the probability-based representations likewise exhibit subject-specific clustering, though with slightly increased dispersion compared to the raw embedding space. This suggests that both internal embeddings and downstream task probability vectors encode individualized ECG characteristics, while emphasizing different aspects of the signal.

3.2. Temporal Stability of ECG Representations

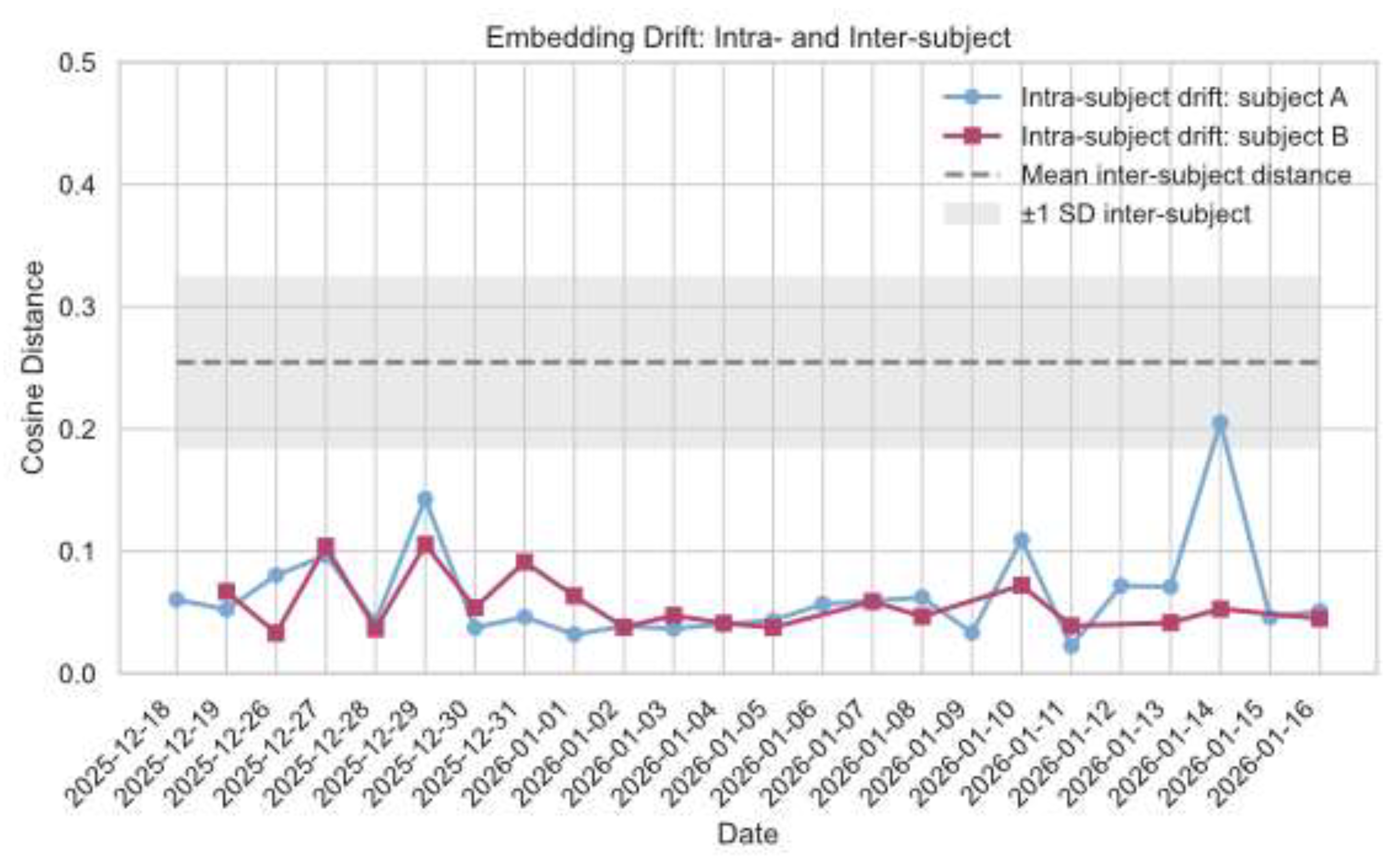

We next evaluated the temporal stability of ECG representations over the recording period. For each subject, intra-subject drift was quantified as the cosine distance between each day’s representation and the subject-specific mean representation computed across all days.

Figure 2 illustrates the resulting drift trajectories for both subjects.

Across the study period, intra-subject drift remained low and varied smoothly over time for both participants, with no abrupt discontinuities. Importantly, intra-subject distances were consistently and substantially smaller than the mean inter-subject distance, which is shown as a dashed reference line with a shaded ±1 standard deviation band. Even at points of maximal deviation, within-subject drift remained well below inter-subject separation, indicating that longitudinal variability did not approach the scale of between-subject differences.

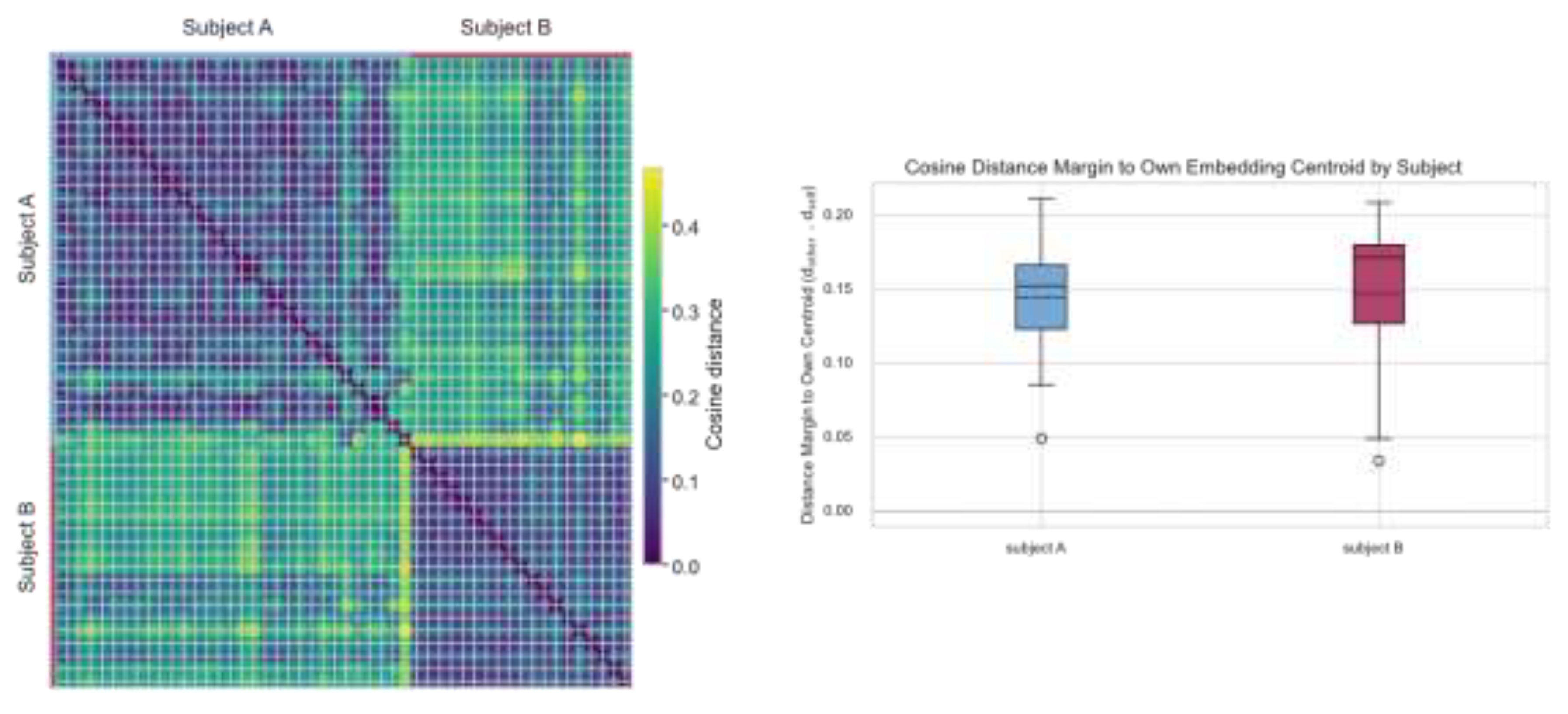

3.3. Distance-Margin Analysis of Subject Separability

To quantify subject-specific separability without training a classifier, we performed a nearest-centroid distance-margin analysis. For each recording, the cosine distance to the subject’s own centroid was compared to the distance to the other subject’s centroid, and a margin was defined as the difference between these two distances. A permutation test with 10,000 random label assignments yielded no permuted mean margin exceeding the observed value (p < 10⁻⁴), indicating that the observed separation is unlikely to arise by chance.

As shown in Figure W, the vast majority of recordings exhibited large positive margins for both subjects, indicating that each ECG representation was consistently closer to its corresponding subject centroid than to the other subject’s centroid. Margin distributions were similar across subjects, suggesting symmetric separability. Occasional low-margin samples were observed but remained positive, consistent with transient signal variability rather than systematic overlap.

3.4. Summary of Representation Behavior

Taken together, these results demonstrate that ECG foundation model representations—whether derived from internal embedding vectors or from task-level probability outputs—are both temporally stable and strongly subject-specific over a one-month period. The combination of clear geometric separation, low intra-subject drift, and consistently positive distance margins supports the use of these representations for longitudinal analysis of individual ECG signals, even in small-N, real-world recording settings.

4. Discussion

In this study, we explored the longitudinal behavior of ECG foundation model representations derived from portable, consumer-grade devices. Our analysis revealed several key insights relevant to both wearable ECG monitoring and representation learning for physiological signals.

First, principal component analysis (PCA) of the ECG embeddings and the model’s task-probability vectors demonstrated clear subject-specific clusters despite variability in recording conditions (

Figure 1). This aligns with prior work suggesting that learned representations can capture individual physiological signatures and demographic information in wearable biosignal data [

6]. The use of foundation model embeddings thus extends beyond single-task outputs to capture broader latent structure in ECG signals.

Second, temporal drift analysis showed that intra-subject distances to mean representations remained consistently lower than inter-subject distances over the one-month recording period (

Figure 2). Stability over time is a critical requirement for longitudinal monitoring applications, where within-individual variability must be distinguishable from between-individual differences. In contrast to standard ECG classification tasks, which focus on detecting abnormalities at a single time point, our work emphasizes the persistence of individual representation trajectories in real-world conditions. This point echoes broader challenges in longitudinal representation learning for health data, including the need to efficiently utilize repeated measures while accounting for intra-individual dynamics [

14].

Third, the distance-margin analysis demonstrated robust subject-specific separability, with most recordings exhibiting positive margins, indicating that embeddings clustered closer to the correct subject’s centroid (

Figure 3). This separability supports the feasibility of biometric and personalized monitoring applications using foundation model features, supplementing rather than replacing traditional diagnostic approaches. Related research in ECG biometrics and authentication has similarly found that individualized models can achieve high separability, though typically in more controlled datasets or using dedicated biometric models [

15].

Importantly, our work leverages portable ECG recordings collected in everyday settings, rather than clinical or laboratory conditions. While prior machine learning studies on wearable ECG have demonstrated diagnostic classification performance for arrhythmias and other conditions, they often rely on curated data or focus on task-specific outputs [

7]. In contrast, our study uses foundation model representations to investigate inherent structure and individual variability in the data itself, providing a complementary perspective that may facilitate future developments in remote health monitoring and longitudinal phenotyping.

In conclusion, our results indicate that foundation model representations obtained from portable ECG devices are both stable over time and individualized, even in small datasets. This supports the potential use of such representations for personalized longitudinal health monitoring and highlights a promising direction for integrating advanced representation learning methods with consumer-grade physiological sensing technologies.

Limitations:

There are several limitations and avenues for future work. The sample size in this study is small by design; while dense longitudinal data provide insights into within-person dynamics, larger cohorts would be necessary to generalize these findings to wider populations and to explore demographic or clinical correlates of representation drift. Additionally, while our analysis focuses on generalized foundation model embeddings and task outputs, future studies could examine how fine-tuning or self-supervised adaptation for individual users further improves stability and separability. In addition, other representations of ECG data using standard metrics that can be derived from ECGs, such as heart rate variability and QRS delineation [

16,

17,

18,

19,

20], could also be stable representations of individual patterns. However, we explicitly wanted to investigate foundation model-based representations on mobile devices.

References

- Sattar, Y.; Chhabra, L. “Electrocardiogram,” in StatPearls [Internet]; StatPearls Publishing, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Naveen, S.; Sivakumar, T. B.; Supreeth, B. R.; Niranjana, R.; Priya, V.; Saranya. Remote patient monitoring system with wearable IoT devices and biosensors for vital signs. in 2025 3rd International Conference on Device Intelligence, Computing and Communication Technologies (DICCT), Mar. 2025; IEEE; pp. 269–274. [Google Scholar]

- Bouzid, Z.; Al-Zaiti, S. S.; Bond, R.; Sejdić, E. Remote and wearable ECG devices with diagnostic abilities in adults: A state-of-the-science scoping review. Heart Rhythm 2022, vol. 19(no. 7), 1192–1201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Medina-Avelino, J.; Silva-Bustillos, R.; Holgado-Terriza, J. A. Are Wearable ECG Devices Ready for Hospital at Home Application? Sensors (Basel) 2025, vol. 25(no. 10). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hughes, A.; Shandhi, M. M. H.; Master, H.; Dunn, J.; Brittain, E. Wearable Devices in Cardiovascular Medicine. Circ Res 2023, vol. 132(no. 5), 652–670. [Google Scholar]

- Abbaspourazad, S.; Elachqar, O.; Miller, A. C.; Emrani, S.; Nallasamy, U.; Shapiro, I. “Large-scale Training of Foundation Models for Wearable Biosignals,” Dec. 08, 2023. 22 Jan 2026. Available online: http://arxiv.org/abs/2312.05409.

- Alimbayeva, Z.; Alimbayev, C.; Ozhikenov, K.; Bayanbay, N.; Ozhikenova, A. Wearable ECG Device and Machine Learning for Heart Monitoring. Sensors (Basel) 2024, vol. 24(no. 13). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McKeen, K.; Masood, S.; Toma, A.; Rubin, B.; Wang, B. ECG-FM: an open electrocardiogram foundation model. Jamia Open 2025, vol. 8(no. 5), ooaf122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Foundation model of ECG diagnosis: Diagnostics and explanations of any form and rhythm on ECG. Cell Reports Medicine 2024, vol. 5(no. 12), 101875. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mathew, G.; Barbosa, D.; Prince, J.; Venkatraman, S. Foundation models for cardiovascular disease detection via biosignals from digital stethoscopes. npj Cardiovascular Health 2024, vol. 1(no. 1), 25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moody, J. B. A Foundation Transformer Model with Self-Supervised Learning for ECG-Based Assessment of Cardiac and Coronary Function. NEJM AI 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kalidas, V. Machine Learning Techniques for Automated Detection of Cardiac Arrhythmias. 2020.

- Li, J. An Electrocardiogram Foundation Model Built on over 10 Million Recordings. NEJM AI 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ahmed, N. “Optimizing Longitudinal Data Representation to Predict Clinical Scores Using an End-to-End Machine Learning Pipeline: A Case Study in Parkinson’s Disease,” Feb. 2025, Accessed: Jan. 22, 2026. Available online: https://hdl.handle.net/20.500.14776/8810.

- Rai, D. H.; Kafley, S. “Lightweight MobileNetV1+GRU for ECG Biometric Authentication: Federated and Adversarial Evaluation,” Sep. 21, 2025. 22 Jan 2026. Available online: http://arxiv.org/abs/2509.20382.

- Makowski, D. , NeuroKit2: A Python toolbox for neurophysiological signal processing. Behav Res Methods 2021, vol. 53(no. 4), 1689–1696. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Burke, G. M.; Wang, N.; Blease, S.; Levy, D.; Magnani, J. W. Assessment of reproducibility--automated and digital caliper ECG measurement in the Framingham Heart Study. J Electrocardiol 2014, vol. 47(no. 3), 288–293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Matveev, M. , Assessment of the stability of morphological ECG features and their potential for person verification/identification. MATEC Web Conf. 2017, vol. 125, 02004. [Google Scholar]

- Merone, M.; Soda, P.; Sansone, M.; Sansone, C. ECG databases for biometric systems: A systematic review. Expert Syst. Appl. 2017, vol. 67, 189–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barros, A. Data Improvement Model Based on ECG Biometric for User Authentication and Identification. Sensors (Basel) 2020, vol. 20(no. 10). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |