Submitted:

26 January 2026

Posted:

28 January 2026

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Site and Population

2.2. Fecal Sample Collection

2.3. Sample Analysis

2.4. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Prevalence of GIPs

3.2. Mixed Infection

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| GIPs | Gastrointestinal parasites |

| EFCOM | The Eastern Forest Complex |

References

- Vicente, J.; Vercauteren, K.C.; Gortázar, C. Diseases at the Wildlife–Livestock Interface: Research and Perspectives in a Changing World; Springer Nature: Cham, Switzerland, 2021; vol. 3, pp. 91–119. [Google Scholar]

- Fowler, M.E.; Mikota, S.K. Biology, Medicine and Surgery of Elephants; Blackwell Publishing: Oxford, UK, 2006; pp. 159–181. [Google Scholar]

- Chandrasekharan, K.; Radhakrishnan, K.; Cheeran, J.V.; Muraleedharan, K.N.; Prabhakaran, T. Review of the incidence, etiology and control of common diseases of Asian elephants with special reference to Kerala. In Healthcare Management of Captive Asian Elephants; Ajitkumar, G., Anil, K.S., Alex, P.C., Eds.; Kerala Agricultural University Press: Pookot, India, 2009; pp. 92–100. [Google Scholar]

- Ahmed, N.; Doley, S. Prevalence of gastro-intestinal parasitic load of Asian elephants (Elephas maximus) in Unakoti, Tripura. J. Entomol. Zool. Stud. 2017, 5(4), 1514–1515. [Google Scholar]

- Adhikari, B.; Pokhrel, S.; Acharya, A.; Dhakal, D.; Shrestha, A.; Acharya, K.P. Prevalence of intestinal parasites in captive Asian elephants (Elephas maximus) in Central Nepal. J. Vet. Parasitol. 2025, 39(1), 23–30. [Google Scholar]

- Dahal, G.; Sadaula, A.; Gautam, M.; Magar, A.R.; Adhikari, S. Prevalence of gastrointestinal parasites in endangered captive Asian elephants (Elephas maximus) of Chitwan National Park in Nepal. Arch. Agric. Environ. Sci. 2023, 8(3), 290–294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Phuphisut, O.; Maipanich, W.; Pubampen, S.; Yindee, M.; Kosoltanapiwat, N.; Nuamtanong, S.; Adisakwattana, P. Molecular identification of the strongyloid nematode Oesophagostomum aculeatum in the Asian wild elephant Elephas maximus. J. Helminthol. 2016, 90(4), 434–440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deak, G.; Germitsch, N.; Rojas, A.; Sazmand, A. Wildlife parasitology: Emerging diseases and neglected parasites. Front. Vet. Sci. 2024, 11, 1439564. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abeysekara, N.; Rajapakse, R.J.; Rajakaruna, R.S. Comparative cross-sectional survey on gastrointestinal parasites of captive, semi-captive, and wild elephants of Sri Lanka. J. Threat. Taxa 2018, 10(5), 11583–11594. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abhijith, T.V.; Ashokkumar, M.; Dencin, R.T.; George, C. Gastrointestinal parasites of Asian elephants (Elephas maximus L. 1978) in south Wayanad forest division, Kerala, India. J. Parasit. Dis. 2018, 42, 382–390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thurber, M.I.; O’Connell-Rodwell, C.E.; Turner, W.C.; Nambandi, K.; Kinzley, C.; Rodwell, T.C.; Faulkner, C.T.; Felt, S.A.; Bouley, D.M. Effects of rainfall, host demography and musth on strongyle fecal egg counts in African elephants (Loxodonta africana) in Namibia. J. Wildl. Dis. 2011, 47, 172–181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McLean, E.R.; Kinsella, J.M.; Chiyo, P.I.; Obanda, V.; Moss, C.J.; Archie, E.A. Genetic identification of five strongyle nematode parasites in wild African elephants (Loxodonta africana). J. Wildl. Dis. 2012, 48, 707–716. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mbaya, A.W.; Ogwiji, M.; Kumshe, H.A. Effects of host demography, season and rainfall on the prevalence and parasitic load of gastrointestinal parasites of free-living elephants (Loxodonta africana) of the Chad Basin National Park, Nigeria. Pak. J. Biol. Sci. 2013, 16, 1152–1158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lynsdale, C.L.; Franco dos Santos, D.J.; Hayward, A.D.; Mar, K.U.; Htut, W.; Aung, H.H.; Soe, A.T.; Lummaa, V. A standardised faecal collection protocol for intestinal helminth egg counts in Asian elephants, Elephas maximus. Int. J. Parasitol. Parasites Wildl. 2015, 4(3), 307–315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Saseendran, P.C.; Rajendran, S.; Subramanian, H.; Sasikumar, M.; Vivek, G.; Anil, K.S. Incidence of helminthic infection among annually dewormed captive elephants. Zoos’ Print J. 2004, 19, 1422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hing, S.; Othman, N.; Nathan, S.K.S.S.; Fox, M.; Fisher, M.; Goossens, B. First parasitological survey of endangered Bornean elephants (Elephas maximus borneensis). Endanger. Species Res. 2013, 21, 223–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mar, K.U. The Demography and Life-History Strategies of Timber Elephants of Myanmar. Ph.D. Thesis, University College London, London, UK, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Obanda, V.; Ndeereh, D.; Mijele, D.; Ngethe, J.; Waititu, K.; Wambua, L.; Warigia, M.; Gakuya, F.; Alasaad, S. Infection dynamics of gastrointestinal helminths in sympatric non-human primates, livestock and wild ruminants in Kenya. PLoS ONE 2019, 14(6), e0217929. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chakraborty, D.; Reddy, M.; Tiwari, S.; Umapathy, G. Land use change increases wildlife parasite diversity in Anamalai Hills, Western Ghats, India. Sci. Rep. 2019, 9, 11975. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ishwaran, N. Elephant and woody-plant relationships in Gal Oya, Sri Lanka. Biol. Conserv. 1983, 26(3), 255–270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohapatra, K.K.; Patra, A.K.; Paramanik, D.S. Food and feeding behaviour of Asiatic elephant (Elephas maximus Linn.) in Kuldiha Wildlife Sanctuary, Odisha, India. J. Environ. Biol. 2013, 34(1), 87–92. [Google Scholar]

- Cox, P.; Griffith, M.; Angles, M.; Deere, D.; Ferguson, C. Concentrations of pathogens and indicators in animal feces in the Sydney watershed. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2005, 71(10), 5929–5934. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nielsen, M.K.; Vidyashankar, A.N.; Andersen, U.V.; DeLisi, K.; Pilegaard, K.; Kaplan, R.M. Effects of fecal collection and storage factors on strongylid egg counts in horses. Vet. Parasitol. 2010, 167(1), 55–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vidya, T.N.C.; Sukumar, R. The effect of some ecological factors on the intestinal parasite loads of the Asian elephant (Elephas maximus) in southern India. J. Biosci. 2002, 27(5), 521–528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nishanth, B.; Srinivasan, S.R.; Jayathangaraj, M.G.; Sridhar, R. Incidence of endoparasitism in free-ranging elephants of Tamil Nadu State. Tamilnadu J. Vet. Anim. Sci. 2012, 8(6), 332–335. [Google Scholar]

- Vimalraj, P.G.; Jayathangaraj, M.G. Endoparasitic infections in free-ranging Asiatic elephants of Mudumalai and Anamalai Wildlife Sanctuary. J. Parasit. Dis. 2015, 39, 474–476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heinrich, L. Prevalence and Molecular Identification of Helminths in Wild and Captive Sri Lankan Elephants (Elephas maximus).; Research Project, Royal Veterinary College, University of London, London, UK, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Abeysinghe, K.S.; Perera, A.N.F.; Pastorini, J.; Isler, K.; Mammides, C.; Fernando, P. Gastrointestinal strongyle infections in captive and wild elephants in Sri Lanka. Gajah 2017, 46, 21–27. [Google Scholar]

- Watve, M.G.; Sukumar, R. Parasite abundance and diversity in mammals: Correlates with host ecology. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 1995, 92(19), 8945–8949. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chel, H.M.; Iwaki, T.; Hmoon, M.M.; Thaw, Y.N.; Soe, N.C.; Win, S.Y.; Bawm, S.; Htun, L.L.; Win, M.M.; Oo, Z.M.; et al. Morphological and molecular identification of cyathosthomine gastrointestinal nematodes of Murshidia and Quilonia species from Asian elephants in Myanmar. Int. J. Parasitol. Parasites Wildl. 2020, 11, 294–301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chichilichi, B.; Pradhan, C.R.; Babu, L.K.; Sahoo, N.; Panda, M.R.; Mishra, S.K.; Behera, K.; Das, A.; Hembram, A. Incidence of endoparasite infestation in free-ranging and captive Asian elephants of Odisha. Int. J. Livest. Res. 2018, 9, 302–310. [Google Scholar]

- Stremme, C.; Lubis, A.; Wahyu, M. Implementation of regular veterinary care for captive Sumatran elephants (Elephas maximus sumatranus). J. Asian Elephant Spec. Group 2007, 27, 6–14. [Google Scholar]

- Karki, K.; Manandhar, P. Incidence of gastrointestinal helminthes in captive elephants in wildlife reserves of Nepal. Articlesbase: Free Online Articles Directory. 2008. Available online: https://www.scribd.com/document/3722208/Incidence-of-Gastrointestinal-Helminthes-in-Captive-Elephants-in-Wildlife-Reserves-of-Nepa (accessed on 23 October 2025).

- Shahi, M.K.; Gairhe, K.P. Prevalence of helminths in wild Asian elephants and Indian rhinoceros in Chitwan and Bardia National Park, Nepal. Nepal. Vet. J. 2019, 36, 60–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malatji, D.P.; Mukaratirwa, S.; Kufahakurume, F. Environmental factors influencing the transmission dynamics of Fasciola spp. in large herbivores. Parasitol. Res. 2020, 119, 2891–2903. [Google Scholar]

- Chaoudhary, V.; Hasnani, J.J.; Khyalia, M.K.; Pandey, S.; Chauhan, V.D.; Pandya, S.S.; Patel, P.V. Morphological and histological identification of Paramphistomum cervi (Trematoda: Paramiphistoma) in the rumen of infected sheep. Vet. World 2015, 8(1), 125–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sakpuaram, T.; Sattabongkot, J.; Boonmars, T. Epidemiology of Paramphistomum infections in livestock in Thailand. Asian J. Vet. Parasitol. 2022, 31(3), 291–301. [Google Scholar]

- Kaewnoi, D.; Wiriyaprom, R.; Indoung, S.; Ngasaman, R. Gastrointestinal parasite infections in fighting bulls in South Thailand. Vet. World 2020, 13(8), 1544–1549. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dharmarajan, G. Epidemiology of Helminth Parasites in Wild and Domestic Herbivores at the Mudumalai Wildlife Sanctuary, Tamil Nadu. Ph.D. Thesis, Tamil Nadu Veterinary and Animal Sciences University (TANUVAS), Chennai, India, 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Fontanarrosa, M.F.; Vezzani, D.; Basabe, J.; Eiras, D.F. An epidemiological study of gastrointestinal parasites of dogs from southern Greater Buenos Aires (Argentina): Age, gender, breed, mixed infections, and seasonal and spatial patterns. Vet. Parasitol. 2006, 136(3–4), 283–295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Woolhouse, M.E.; Taylor, L.H.; Haydon, D.T. Population biology of multihost pathogens. Science 2001, 292(5519), 1109–1112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Walker, J.G.; Plein, M.; Morgan, E.R.; Vesk, P.A. Uncertain links in host–parasite networks: Lessons for parasite transmission in a multi-host system. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. B Biol. Sci. 2017, 372(1719), 20160095. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Namirembe, D.; Huyse, T.; Madsen, H.; et al. Liver fluke and schistosome cross-infection risk between livestock and wild mammals in Western Uganda, a One Health approach. Int. J. Parasitol. Parasites Wildl. 2024, 25(1), 101022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Watwiengkam, N.; Patikae, P.; Thiangthientham, P.; Ruksachat, N.; Simkum, S.; Arunlerk, K.; Purisotayo, T. Prevalence of gastrointestinal parasites in free-ranging bantengs (Bos javanicus) and domestic cattle at a wildlife–livestock interface in Thailand. Trends Sci. 2024, 21(3), 7368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Babayani, N.D.; Rose Vineer, H.; Walker, J.G.; Davidson, R.K. Climate and parasite transmission at the livestock–wildlife interface. Front. Vet. Sci. 2022, 8, 816303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| GIPs | Prevalence of GIPs infection | χ2 | p-value | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total (N=135) % (95% CI) |

Population A (n=83) % (95% CI) |

Population B (n=13) % (95% CI) |

Population C (n=39) % (95% CI) |

||||

| Egg | Nematode | ||||||

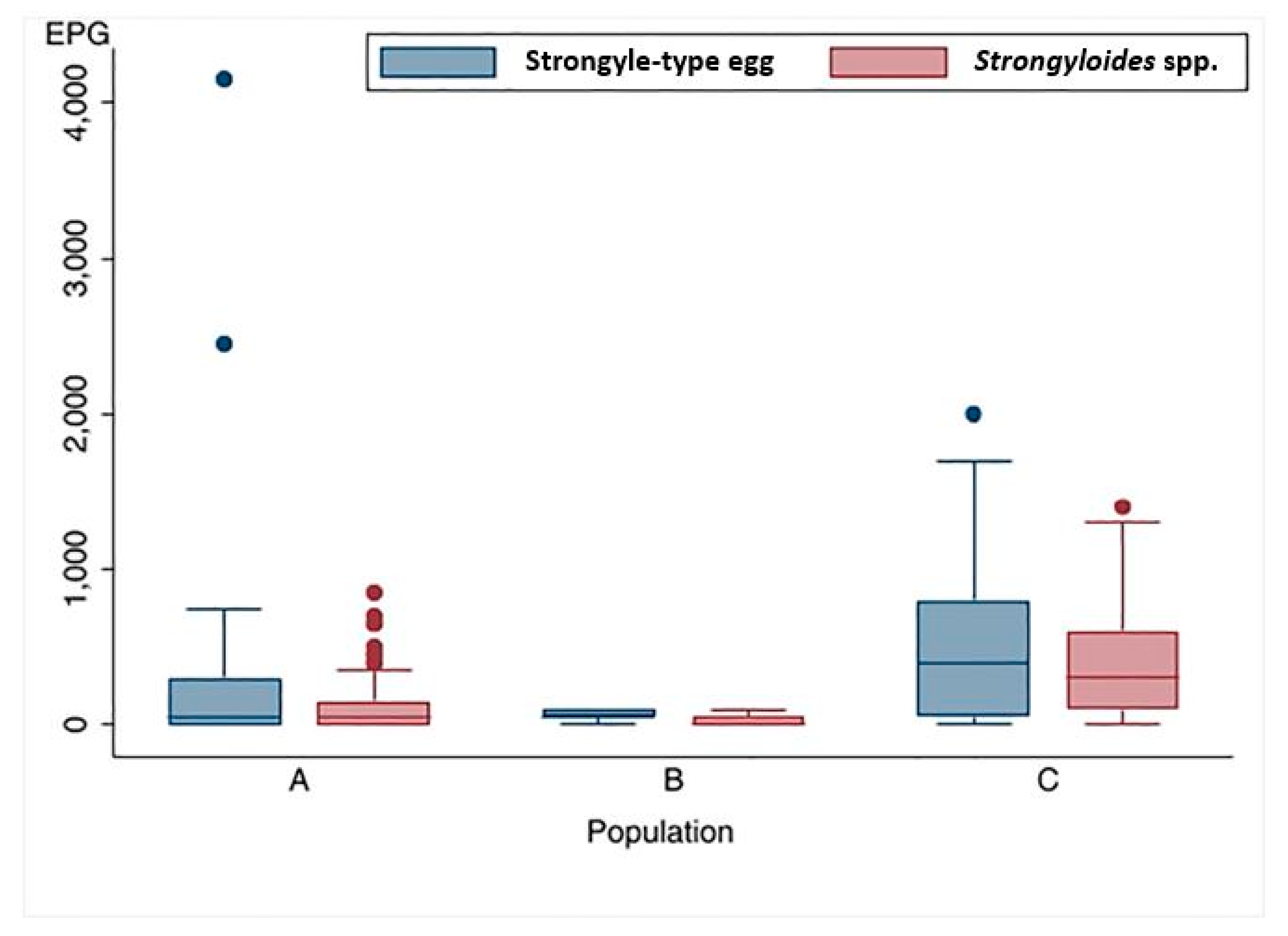

| Strongyle-type | 79.3 (72.4-86.1) | 68.7 (57.5-78.4) | 100 (75.3-100) | 94.9 (82.7-99.4) | 14.84 | 0.001 | |

| Strongyloides spp. | 56.3 (47.9-64.7) | 42.2 (31.4-53.5) | 53.8 (25.1-80.8) | 87.2(72.6-95.7) | 21.88 | < 0.001 | |

| Trematode | |||||||

| Paramphistomum spp. | 61.5 (53.3-69.7) | 67.5 (56.3-77.3) | 46.1 (19.2-74.9) | 53.8 (37.2-70.0) | 3.51 | 0.173 | |

| Fasciola spp. | 5.2 (1.4-8.9) | 6.0 (2.0-13.5) | 15.4 (1.9-45.4) | 0 (0-9.0) | 5.0 | 0.082 | |

| Larval Stage | |||||||

| Strongyloides spp. | 55.6 (47.2-63.9) | 39.8 (29.2-51.1) | 61.5 (31.6-86.1) | 87.2 (72.6-95.7) | 24.37 | < 0.001 | |

| Non-Strongyloides spp. | 83.0 (76.6-89.3) | 72.3 (61.2-81.5) | 100 (75.3-100) | 100 (91.0-100) | 17.37 | < 0.001 | |

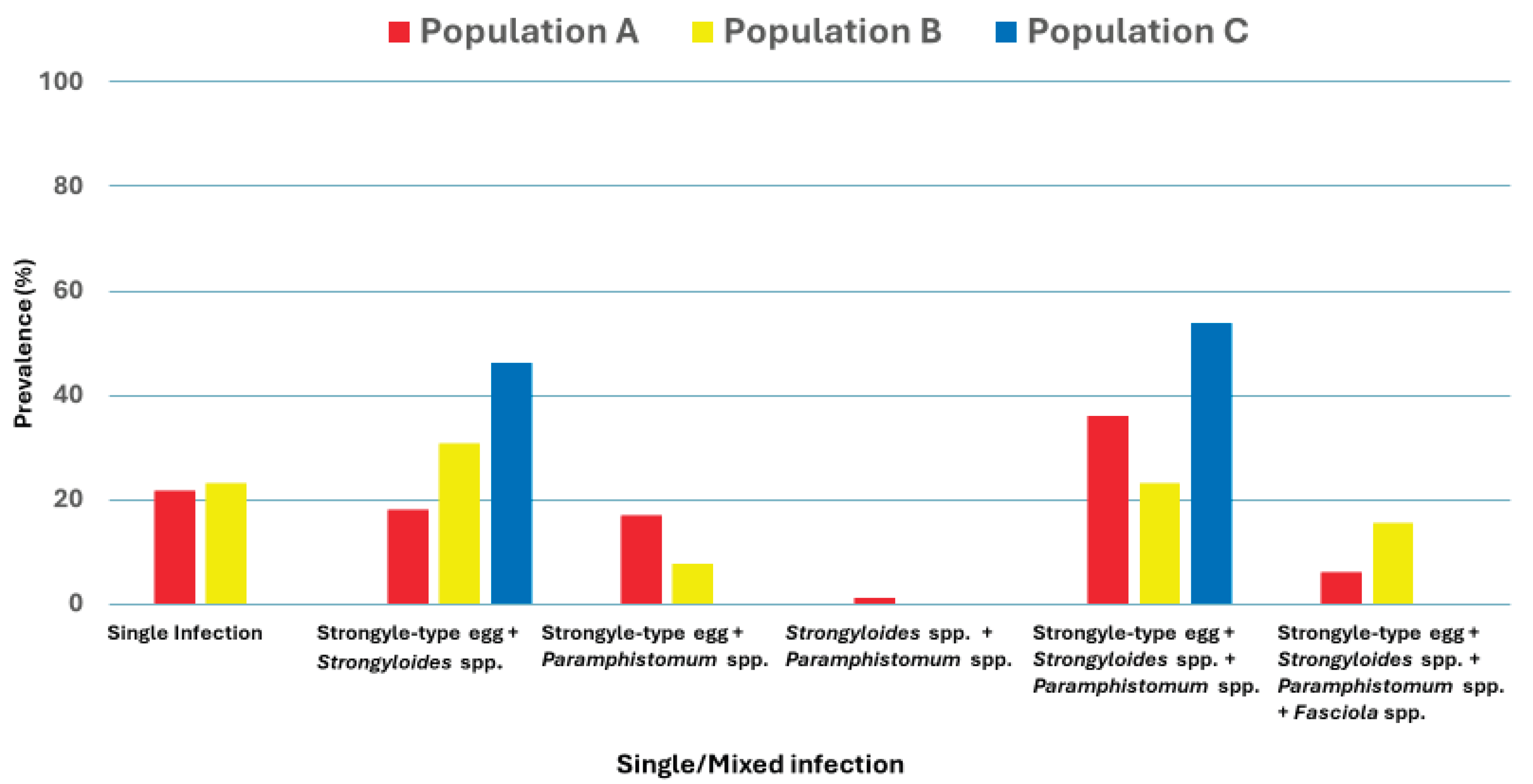

| Mixed infection | 84.4 (78.3-90.6) | 78.3 (67.9-86.6) | 76.9 (46.2-95) | 100 (91.0-100) | 10.12 | 0.006 | |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.